Abstract

Glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) have unique properties of self-renewal and tumor initiation that make them potential therapeutic targets. Development of effective therapeutic strategies against GSCs requires both specificity of targeting and intracranial penetration through the blood-brain barrier. We have previously demonstrated the use of in vitro and in vivo phage display biopanning strategies to isolate glioblastoma targeting peptides. Here we selected a 7-amino acid peptide, AWEFYFP, which was independently isolated in both the in vitro and in vivo screens and demonstrated that it was able to target GSCs over differentiated glioma cells and non-neoplastic brain cells. When conjugated to Cyanine 5.5 and intravenously injected into mice with intracranially xenografted glioblastoma, the peptide localized to the site of the tumor, demonstrating intracranial tumor targeting specificity. Immunoprecipitation of the peptide with GSC proteins revealed Cadherin 2 as the glioblastoma cell surface receptor targeted by the peptides. Peptide targeting of Cadherin 2 on GSCs was confirmed through ELISA and in vitro binding analysis. Interrogation of glioblastoma databases demonstrated that Cadherin 2 expression correlated with tumor grade and survival. These results confirm that phage display can be used to isolate unique tumor-targeting peptides specific for glioblastoma. Furthermore, analysis of these cell specific peptides can lead to the discovery of cell specific receptor targets that may serve as the focus of future theragnostic tumor-homing modalities for the development of precision strategies for the treatment and diagnosis of glioblastomas.

Keywords: stem cells, cancer stem cells, glioma, cell surface markers, stem cell culture

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Significance Statement.

In this manuscript, we demonstrate the ability of a 7 amino acid length peptide to specifically target glioblastoma in mice models following intravenous injection. This peptide selectively targets glioblastoma by binding the Cadherin 2 surface protein on glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs). The selective targeting ability of this peptide can allow it to potentially augment diagnostic and therapeutic delivery strategies against glioblastoma for earlier detection and more effective tumor treatment. The isolation of Cadherin 2 as a potential-specific GSCs surface receptor may serve as a target that can be exploited in the development of future therapeutics against GSCs.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (World Health Organization grade IV astrocytoma IDH-wild type) is the most prevalent primary malignant brain tumor. Current standard of care consists of maximal safe surgical resection, followed by concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy, followed by maintenance chemotherapy.1 Tumor recurrence is universal, and second-line therapies are generally ineffective at sustained tumor control.2 Improved therapeutic targeting of glioblastoma may be derived through selective tumor cell targeting.3 A central challenge in neuro-oncology is the restriction of intracranial delivery of therapeutic agents due to the neurovascular unit (blood-tumor barrier) and increased tumor oncotic pressure.4,5 Substantial efforts have been devoted to identifying cell surface receptors on glioblastoma cells (eg, EGFRvIII or IL13Rα2) that bind ligands to enhance the efficiency of therapeutic delivery of ligand-toxin or cell-based therapies.6,7 However, such strategies have proven challenging for glioblastoma due to the lack of exclusive expression on tumor cells or the lack of uniformity of the targeted receptors within the tumor.6

Phage display is a screening strategy that allows for the isolation of short amino acid peptides against a specific target.8 Of particular advantage is that the selection strategies can be used with intact cells as well as against tumors in vivo in the absence of predetermined molecular targets, facilitating not only identification of novel peptides but also specific molecular targets. Phage display has enjoyed particular attention due to the rapid translation of the identified sequences into engineered antibodies and cell-based therapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells.9 We previously demonstrated the feasibility of using a combination of in vitro and in vivo phage display biopanning strategies to isolate peptides that specifically target glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), and used these peptides to isolate proteins that play a role in the maintenance of GSCs.10,11 Here, we selected a peptide that was isolated in both the in vitro and in vivo biopanning strategies and tested its ability to target GSCs in culture as well as through intravenous injection in glioblastoma mice models. Following confirmation of peptide binding to GSCs, we isolated the receptor protein to identify a glioblastoma specific marker and potential target for development of future therapeutics aimed at glioblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Study Approval

Experiments performed were approved by the Institutional Reviewed Board at the Cleveland Clinic and H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute (IRB# ISO00010727) in accordance with the ethical guidelines set forth at each institution. GSCs, tumor tissue, and non-malignant normal brain (from epileptic brain tissue specimens) were harvested from patient tumor samples or epileptic brain at Duke University Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic, and University Hospital Cleveland Medical Center in accordance with an approved protocol by the respective Institutional Review Boards. All animal experiments were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC# IS00004878) at each institution.

Isolation and Cell Culture

Glioblastoma cells were harvested from patient samples at the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western Reserve University. GSCs were isolated and maintained as previously described.12 Cells were maintained as xenografts in 4-week-old NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice which were also used for all animal experiments. GSC lines 4121, 387, and 3691 were used for testing. GSC line 387 was used for all in vitro peptide binding and xenografts.

In Vitro and In Vivo Biopanning of Phage Library

In vitro and in vivo phage display biopanning were performed as previously described.10 In brief, a 7-amino acid length phage display peptide library kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) was used to complete in vitro and in vivo biopanning of phage library experiments. 5 × 104 glioblastoma cells were implanted into the brain hemisphere of NSG mice. After maximal tumor growth, the phage display library was intravenously injected, and the library was allowed to circulate and bind to cellular targets. After 24 hours, tumors were harvested, and cells were lysed to isolate and purify bound phage peptides. Collected phages were transduced into Escherichia coli for phage clone isolation and DNA sequencing to recover bound peptide sequences.

In parallel, in vitro biopanning was performed as previously described.11 Using the 7-amino acid–length peptide library, negative selection was performed against extracellular-matrix–coated plates and differentiated tumor cells. The remaining phage library was applied to CD133+ GSCs, and 4 rounds of positive selection were performed. After the fourth round of selection, phage clones were isolated through bacterial infection, and sequencing was performed to isolate peptide sequences.

Fluorescent Peptide Synthesis and Immunostaining

The 5(6)-Carboxyfluorescein-conjugated peptide AWEFYFP (GSC-IC2-Fl), was synthesized by the Cleveland Clinic Molecular Biotechnology Core. The cyanine 5.5-conjugated peptide (GSC-IC2-Cy5) and biotinylated peptide AWEFYFP (GSC-IC2-b), and the non-targeting (NT) peptides GGGSGGG (NT-Cy5 and NT-b) were synthesized by LifeTein, LCC (Hillsborough, NJ, USA). GSC-IC2-Fl peptide (1 mg/mL ) was diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1 to 30 peptide dilution. Tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. The slides were then incubated with diluted peptides overnight at 4 °C. Nuclei were stained with 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were acquired using a Leica DM4000 upright microscope or Leica TCS-SP/SP-AOBS upright confocal microscopes.

In Vivo Imaging

GSCs were implanted subcutaneously (5 × 105 cells) or intracranially (5 × 104 cells) into NSG mice. After 4 weeks, Cy5-conjugated peptides (GSC-IC2-Cy5.5 and NT-Cy5) were intravenously injected into the mice. Signals from injected peptides were monitored by fluorescence channel of IVIS Spectrum CT In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for up to 72 hours.

Histology

Mice with or without intracranial (IC) GSC xenograft received an intravenous injection of 400 μM GSC-IC2-Cy5 peptide. One hundred and fifty minutes after intravenous injection, mice were sacrificed and perfused with PBS to remove non-specific tissue binding of the peptide. Brains were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before ex vivo imaging. Brain tissues sections (10 µm) counterstained with DAPI and fluorescent images were acquired using a Leica DM4000 upright microscope.

Peptide Pull Down Assay

GSC lysates were obtained with Pierce IP Lysis Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, ice-cold Pierce IP Lysis Buffer was added to the cell pellet (10:1, v/w) and incubated on ice 5 minutes before centrifugation (13 000 × g, 10 minutes, 4 °C). For the pull-down assay, 40 µg of biotinylated peptides (GSC-IC2-b and NT-b) were coupled with 200 µL of Pierce streptavidin agarose resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 hour at 4 °C. Peptides-coupled streptavidin agarose resin (500 µL) were incubated with pre-cleared protein (500 µL) overnight at 4 °C. The resin was washed in 1 mL of PBS, centrifuged (2500 × g, 2 minutes at room temperature (RT)) and transferred in a new tube 4 times, before being sent for mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Mass spectrometry analysis was conducted in the Proteomics and Metabolomics Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute. To identify binding proteins of GSC-IC2 peptide, the candidates isolated from mass spectrometry analysis were ranked in the order of logarithm of ratio between GSC-IC2 peptide binding proteins and NT peptide binding proteins.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The Nunc MaxiSorp 96-well plate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was coated with 2.5 μg/mL of recombinant human Cadherin 2 and β-catenin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in 0.1 M NaHCO3, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The wells were washed 3 times with 0.05% PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked with PBS/BSA 2% for 2 hours at RT. The biotinylated peptides (GSC-IC2-b or NT-b) were incubated for 1 hour at RT at a dilution of 10 µM. After washing 3 times with PBST, the streptavidin-HRP (1/10 000, Invitrogen) was incubated for 1 hour at RT and washed 3 times with PBST. The 3,3ʹ,5,5ʹ-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB; Thermo Fisher Scientific) substrate (50 μL/well) was incubated between 15 and 30 minutes at RT. An equivalent volume of 2 M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. For the ELISA competition assay, the blocking step was followed by the incubation of 10 µM in PBS/BSA 2% of GSC-IC2-Cy5.5 for 1 hour at RT. After 3 washes with PBST, the biotinylated peptide GSC-IC2-b was incubated as described above.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and isolated using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Reverse transcription into cDNA was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR for total cDNA was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and gene-specific primers: CDH2 forward (5ʹ-CCTCCAGAGTTTACTGCCATGAC-3ʹ) and reverse (5ʹ-GTAGGATCTCCGCCACTGATTC-3ʹ), 18S rRNA forward (5ʹ-GGCCCTGTAATTGGAATGAGTC-3ʹ) and reverse (5ʹ-CCAAGATCCAACTACGAGCTT-3ʹ).

Lentiviral Overexpression of CDH2 in HEK293 Cells

HEK293 cells were transduced with Human CDH2 Lenti–Open Reading Frame particles or a nontargeted control (pLenti-C-mGFP-P2A-Puro; OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA). Transduction was performed as recommended by the manufacturer protocol at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. Infected cells were selected with constant culture in 1 μg/mL puromycin. CDH2 overexpression was confirmed by qRT-PCR.

Cell Staining and Imagestream Flow Cytometry

GSCs in neurobasal media were collected, centrifuged, and dissociated in accutase (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 10 minutes before counting. For 293-Lenti-ORF cells growing attached in DMEM + 10% FBS. Accutase was used to detach the cells from the flask and centrifuged. 1 × 106 cells/mL were distributed in 96-well plates and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 15 minutes. Cells were spun down at 150 g, 5 minutes prior to be incubated at 4 °C for 5 minutes in the dark in 10 µM of GSC-IC2-Cy5 or NT-Cy5 mixed with True-Stain Monocyte Blocker (1/20, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) to avoid non-specific binding of Cy5. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS/BSA 2% and resuspended in 50 µL of PBS/BSA 2% with DAPI (100 ng/mL, Invitrogen). The acquisition was performed with the Amnis Imagestream flow cytometer (Luminex, Austin, TX) and data were analyzed with Image Data Exploration and Analysis Software (IDEAS; Luminex). The gates were made on focused cells, single cells, live cells, and unsaturated fluorescent cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). For competition assays, GSCs were incubated 30 minutes at 4 °C under gentle agitation with an anti-Cadherin 2 unlabeled antibody (1/100, Invitrogen). Cells were washed 2 times and stained with Cy5 conjugated peptides as described above.

Bioinformatic Analysis of Cadherin 2 Expression

Possible interaction between CDH2 gene expression in glioblastoma biopsies and survival were analyzed using GlioVis Data portal.13 The data sets TCGA_GBMLGG, REMBRANDT, and CGGA Primary were used to evaluate the mRNA level (log2) of the CDH2 gene. CGGA and TCGA_GBMLGG data sets provide data from RNA-sequencing and REMBRANDT data set from microarray. Gene expression data in glioblastoma versus other tissue or lower grade gliomas (I, II, III) were compared using the Tukey HSD (Honest Significant Difference) test. CDH2 gene expression effect on survival from the 4 data sets presented above were shown using Kaplan-Meier plots. Each plot displays the statistical analyses, the P-value and the median survival time.

Statistical Analyses

All statistics were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.2 and GraphPadInStat software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) (P < .05; P < .01; P <.001). All grouped data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were assessed by tests or analyses of variance. ImageStream flow cytometry data was analyzed with a one-way ANOVA and a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. A Kruskal-Wallis uncorrected test was used to compare the binding of GSC-IC2, NT, and N-cadherin by ELISA. Mass spectrometry data was analyzed by T tests at Moffitt’s core facilities.

Results

Orthogonal In Vitro and In Vivo Biopanning Strategries Identify Potential Glioblastoma Targeting Peptides

We have previously demonstrated that by using in vitro and in vivo biopanning strategies performed in parallel we were able to isolate a 7 amino acid peptide, AWEFYFP, which was used to identify EYA1 as a novel GSC-specific protein target (Fig. 1).10 In the current study, we took advantage of the previously isolated peptide’s high potential to specifically target glioblastoma and penetrate intracranially implanted tumors, as evidenced by its independent isolation through both in vitro and in vivo screening strategies.

Figure 1.

In vivo glioblastoma stem cell (GSC)-targeting peptide biopanning strategy. In vivo phage display biopanning was performed by tail vein injection of a 7-amino acid–length random peptide library into mice following intracranial glioblastoma xenograft. This biopanning strategy allows for selection of tumor-targeting peptides with the potential to cross the BBB. Among the peptides that were isolated was AWEFYFP which was also isolated through previous in vitro biopanning strategies against GSCs.

GSC-IC2 Peptide Targets GSCs In Vitro

Next, we investigated the potential utility of GSC-IC2 in the identification of bulk glioblastoma cells as well as GSCs. The GSC-IC2 peptide conjugated with fluorescein specifically bound GBM tissue relative to normal brain tissue (Fig. 2A). To determine the relative affinity of GSC-IC2 for GSCs, we performed a staining of GSCs with the peptide, followed by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2B and 2C). The GSC-IC2 peptide conjugated with cyanine 5.5 (GSC-IC2-Cy5), a near infrared marker, specifically bound to GSCs compared to a non-specific 7-amino acid peptide linker sequence (NT-Cy5), as a negative control (P < .001). These results demonstrate the foundation for the translation of the GSC-IC2 into possible clinical applications for tumor cell targeting.

Figure 2.

GSC-IC2 preferentially binds to glioblastomas and GSCs. GSC-IC2 fluorescently labeled (GSC-IC2-FI) demonstrates preferential binding to glioblastoma tissue, co-stained with SOX2 (A). GSC-IC2 conjugated with Cy5 demonstrates preferential binding to the glioma stem cell tumor sphere (B) compared to a non-targeting peptide (NT) (C). Scale bar = 50 µm. *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

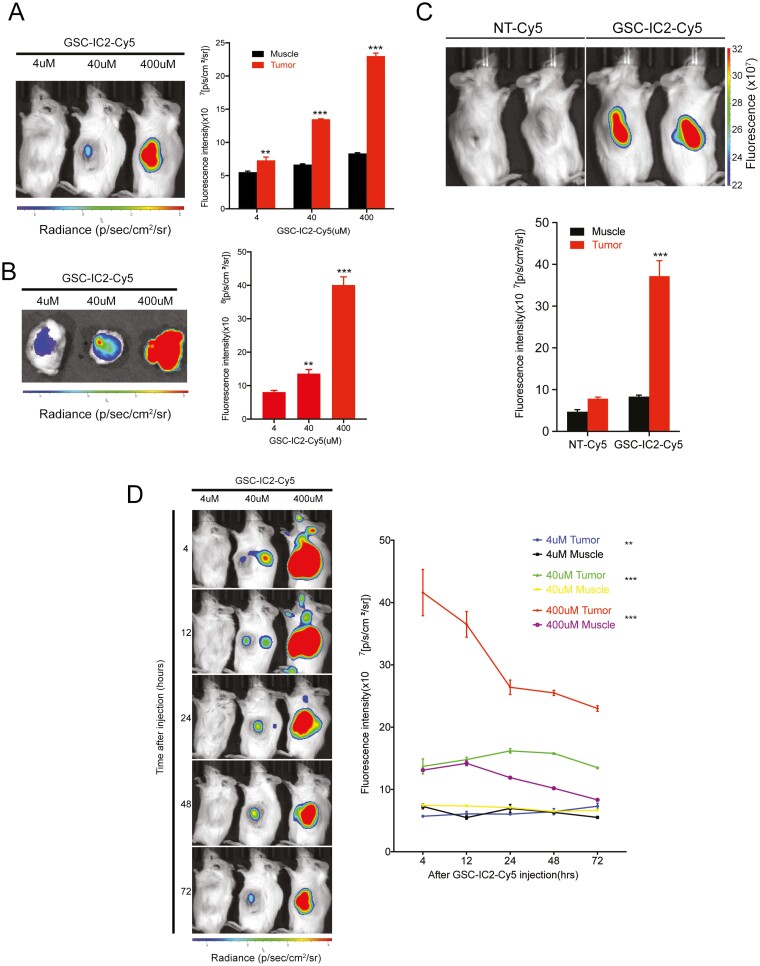

GSC-IC2 Targets Subcutaneous Flank Glioblastoma Tumors Following Intravenous Injection

To determine the potential utility of the peptide to target glioblastoma in vivo, GSC-IC2-Cy5 was injected intravenously into mice bearing glioblastoma xenografts in the subcutaneous flank. This was used to test peptide targeting without the potential limitations of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Increasing peptide concentrations of 4, 40, and 400 µM were administered via tail vein injection. Bioluminescent imaging demonstrated high specificity of binding to the tumor when compared to adjacent muscle tissue; peptide concentrations of 40 µM became visible 20 minutes after injection (Fig. 3A). Resected tumor visualized by fluorescent imaging demonstrated peptide binding starting at 4 µM (Fig. 3B). We compared the signal intensity of tumors and adjacent muscle tissue for specificity of binding, demonstrating minimal peptide binding in muscle without significant change with increasing concentration, while GSC-IC2-Cy5 demonstrated concentration dependent delivery to the tumor. In contrast, the control peptide (NT-Cy5) injected intravenously into tumor-bearing mice demonstrated minimal binding in both the tumor and the adjacent muscle (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

GSC-IC2 targets glioblastoma xenografts following intravenous injection up to 72 hours post injection. GSC-IC2-Cy5 injected into the tail vein of NSG mice bearing glioblastoma xenografted into the subcutaneous flank demonstrates specific targeting of the tumor 4 hours after injection in a dose-dependent manner in vivo (A), ex vivo (B), and compared to an NT-Cy5 peptide (C). Extended imaging of GSC-IC2-Cy5 injected into the tail vein demonstrates persistent tumor binding up 72 hours after peptide injection (D). *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

A time course study was performed to evaluate peptide binding up to 72 hours after injection to analyze the amount of time that the peptide remained bound to the tumor. A peptide signal within the tumor was visualized for up to 72 hours after injection, with a gradual decrease in signal intensity (Fig. 3D). The signal intensity in the adjacent muscle demonstrated little fluctuation from 4 to 72 hours after injection, representing minimal binding to non-tumor tissue.

GSC-IC2 Targets Intracranial Glioblastoma Following Intravenous Injection

Following confirmation of GSC-IC2 localization and targeting of glioblastoma xenografts in the flank, we tested its utility as an intracranial targeting tumor peptide. GSC-IC2-Cy5 was administered intravenously in mice bearing IC patient-derived glioblastoma xenografts (IC PDX) and mice without implanted tumors (non-PDX). Imaging performed 20 minutes after injection demonstrated strong specificity of binding within tumors of IC PDX mice, indicating that the peptide selectively traveled through the vasculature and bound the tumor (Fig. 4A). Ex vivo imaging of tumor-bearing brains showed the peptide signal concentrated at tumor site within the brain (Fig. 4B). To demonstrate the specificity of targeting of intracranial tumors by GSC-IC2, we compared targeting by intravenously injecting IC PDX mice with the control peptide (NT-Cy5). Tumor-bearing brains harvested 48 hours after injection showed minimal binding of the control peptide with persistent binding of the GSC-IC2 peptide (Fig. 4C). To validate our observations, we sacrificed the mice bearing intracranial patient-derived xenografts and harvested the tumors to image and examine the histology. The specificity of peptide binding was confirmed with a strong congregation of peptide signal in glioblastoma, and particularly in perivascular areas (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

GSC-IC2 targets intracranial glioblastoma xenografts. GSC-IC2-Cy5 injected into the tail vein of NSG mice bearing glioblastomas xenografted into the intracranial cavity demonstrates specific targeting of the IC tumor in vivo (A). Fluorescence intensity is quantitatively measured with the IC cavity in mice with (IC PDX) and without tumors (Non-PDX), as well as muscle tissue found in IC PDX mice. Ex vivo, the fluorescence intensity is evaluated in a brain without tumors (Non-PDX), in non-tumor (IC PDX Brain) and tumor (IC PDX Tumor) areas (B). In comparison with NT-Cy5, GSC-IC2-Cy5 demonstrates increased in signal in the tumor (C). Histological analysis demonstrates positive fluorescent signal in the intracranial tumor samples of mice with IC tumors (IC PDX) (D). A lack of peptide binding is visualized in the non-tumor-infiltrated brain within mice with IC tumors (IC PDX Brain) and in brain without IC tumors (Non-PDX Brain). Scale bar = 50 µm. *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

To evaluate whether there could be non-specific targeting of glioblastoma tumors secondary to BBB breakdown, a time course was performed comparing GSC-IC2-Cy5 to NT-Cy5. A strong peptide signal was observed in the intracranial tumor area after 4 hours (Supplementary Fig. S2). However, subsequent imaging demonstrated substantial loss of signal measured by fluorescent imaging within the intracranial cavity 24 and 48 hours after NT-Cy5 peptide injection, while GSC-IC2-Cy5 maintained a stronger signal. The early NT-Cy5 signal may indicate non-specific peptide release as a result of BBB breakdown due to the tumor. The persistent signal in the GSC-IC2-Cy5 mice likely represents specific cellular binding that is persisting 24-48 hours after injection.

Cadherin 2 as a Binding Partner for GSC-IC2 Peptide

Phage display screening allows isolation of cell-specific targeting peptides without predetermined receptor targets. Having validated GSC-IC2 and its specificity for targeting GSCs, we sought to identify its cellular target that may result in the identification of a novel GSC cell surface receptor. To determine the binding partner of GSC-IC2, we performed a peptide pull down assay followed by a mass spectrometry analysis of the peptide bound to proteins (Fig. 5). As GSC-IC2 was isolated in GSC-specific in vitro screening, we used GSCs as the target cell for identifying the receptor. Biotin-tagged GSC-IC2 peptide was incubated with GSC protein lysate and peptides were isolated using streptavidin pulldown. Isolated proteins were identified through mass spectroscopy. The Log 2 ratio between proteins in GSCs binding to GSC-IC2 peptide and NT peptide were evaluated and ranked and several of the highest scoring proteins were selected for binding validation through ELISA (Supplementary Fig. S3). Cadherin 2 (CDH2), also known as N-cadherin, is a transmembrane protein responsible for cellular adhesion, demonstrated strong specificity of binding to GSC-IC2 based on GSC-IC2 to NT binding ratio. GSC-IC2 demonstrated concentration-dependent binding to Cadherin 2 on ELISA, while the non-targeting peptide demonstrated minimal binding regardless of peptide concentration (Fig. 6A). ELISA binding was repeated for several high scoring proteins to confirm binding specificity. In contrast, β-catenin, did not demonstrate specificity for binding to GSC-IC2 (5.67-fold less binding, P < .0001, Supplementary Fig. 4). To verify GSC-IC2 binding to Cadherin 2, a competition ELISA assay was performed. Biotin-tagged GSC-IC2 (GSC-IC2-b) was incubated with immobilized Cadherin 2 with or without GSC-IC2-Cy5. Streptavidin-HRP was applied and GSC-IC2-b binding was measured. The addition of competing GSC-IC2-Cy5 peptide reduced the biotinylated peptide binding demonstrating specificity of targeting of CDH2 (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5.

GSC-IC2 peptide pull down strategy. Peptide pull down and mass spectrometry assays of GSC-IC2 and NT peptides. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 6.

GSC-IC2 targets CDH2. ELISA assay showing a specific binding between GSC-IC2 peptide to Cadherin 2 compared to NT peptide (A). Competition ELISA assay using a non-biotinylated GSC-IC2 peptide shows the specificity of the peptide binding to CDH2 (B). RT-qPCR confirms the overexpression of CDH2 in HEK293 (CDH2) after transduction with Lenti ORF compared to non-transduced cells (293) and transduced cells with GFP (GFP) (C). GSC-IC2-Cy5 or NT-Cy5 applied to HEK293 following lentiviral transduction demonstrated that GSC-IC2 selectively bound to 293-CDH2 over 293 (P = .023) and 293-GFP (P = .0081) cells (D). Imagestream images of 293 cells, 293 cells transduced with GFP (293-GFP), and 293 cells transduced with CDH2 (293-CDH2) were stained with GSC-IC2-Cy5 and NT-Cy5 peptide demonstrates selective Cy5 signal in 293-CDH2 cells (E). *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

GSC-IC2 Targets Cadherin 2 Overexpressed in HEK293 Cells

To further demonstrate the affinity between GSC-IC2 peptide and Cadherin 2, HEK293 cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding either empty vector (293), GFP (293-GFP), or human CDH2 (293-CDH2) (Fig. 6C). GSC-IC2-Cy5 or NT-Cy5 was applied to HEK293 following lentiviral transduction. GSC-IC2 selectively bound 293-CDH2 (Fig. 6D). The staining of these cells with GSC-IC2-Cy5 peptide demonstrated lower MFI in 293 cells (P = .023) and 293-GFP cells (P = .0081) compared to 293-CDH2. In contrast, NT-Cy5 did not demonstrate binding to 293-CDH2 (P = .0323) confirming the affinity of GSC-IC2 for CDH2 (Fig. 6E).

GSC-IC2 Targets Cadherin 2 In Vitro

To confirm that GSC-IC2 targets Cadherin 2 on GSCs, we performed in vitro competition assays against GSCs in culture. GSC-IC2-Cy5 were applied to GSCs grown in culture with and without incubation with anti-CDH2 antibody prior to application of peptide (Fig. 7A). With the antibody, GSC-IC2-Cy5 staining was decreased compared to GSCs incubated with GSC-IC2-Cy5 peptide only (P = .0313), verifying competition of binding at the CDH2 receptor site (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

GSC-IC2 binds to CDH2 on GSCs. Imagestream images of GSC-IC-Cy5 peptide applied to GSCs with and without the addition of anti-CDH2 antibody, demonstrates decreased signal Cy5 signal in the presence of anti-CDH2 antibody (A). Median fluorescence intensity demonstrates significant decrease in GSC-IC2-Cy5 binding (P = .0313) in the presence of anti-CDH2 antibody (B). In silico analysis with Gliovis of CDH2 expression in different data sets shows a higher expression of CDH2 gene in glioblastoma versus different glioma grades or brain tumor types, and a poorer outcome in these patients (C). CGGA: Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas. TCGA_GBMLGG: The Cancer Genome Atlas-Glioblastoma-Low Grade Glioma. ODG: Oligodendroglioma. OA: Oligoastrocytoma. ACM: Astrocytoma. GBM: Glioblastoma. NT: Non-tumor. CGGA Kaplan-Meier curve: CDH2 high n = 110, events = 98, median = 13.9. CDH2 low n = 110, events = 84, median = 19.2. HR = 0.7, (0.52-0.94). TCGA Kaplan-Meier curve: CDH2 high n = 76, events = 60, median = 13.3. CDH2 low n = 76, events = 58, median = 14.7. HR = 0.79 (0.55-1.14). REMBRANDT Kaplan-Meier curve: CDH2 high n = 91, events = 87, median = 10.9. CDH2 low n = 90, events = 85, median = 17.75. HR = 0.71 (0.52-0.96). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

Cadherin 2 Expression Is Correlated with Survival in Glioblastoma

Analysis of CDH2 expression in the TCGA, CCGA, and REMBRANDT tumor databases demonstrated correlation of CDH2 expression with tumor grade (Fig. 7C). Elevated CDH2 expression was also associated with decreased survival, indicating that CDH2 may be an indication of aggressive tumor phenotype.

Discussion

Phage display biopanning is an effective platform for the development of novel targeted therapeutics.14 Small peptides isolated through phage display, that have preferential binding capacity for a given receptor or cell type, can serve as effective targeting modalities. The small size of the peptides enables them to be used as fusion proteins or adjuncts to viral capsids or nanoparticles, without affecting the function of its cargo.15,16 As a result, phage display can accelerate the development of oncologic therapies, including antibodies and cell-based therapies. Based on the challenges of identifying and targeting glioblastoma tumor cells, we hypothesized that phage display biopanning could facilitate novel therapies directed against glioblastoma through the identification of peptides that specifically bind to tumor cells in the brain microenvironment.

We have previously developed in vitro and in vivo strategies for isolating GSC-specific targeting peptides. These peptides were placed into a protein BLAST search to isolate potentially GSC-specific proteins in which the peptides may be mimicking. This strategy discovered and validated 2 novel GSC proteins.10,11 The primary goal of this study was to examine whether peptides isolate by phage display could be used to augment targeting of glioblastoma tumor cells. In addition to using peptides isolated from in vitro biopanning, similar to the previous report by Beck et al, we incorporated peptides isolated from in vivo biopanning of mice models with intracranially implanted patient-derived glioblastoma xenografts.17 This strategy was used to select for peptides that would have the ability to navigate through the circulatory system following intravenous tail vein injection and selectively target the glioblastoma tumor cells. Although recovered peptides from this strategy resulted in a much lower yield, one of the recovered peptides sequences matched a peptide recovered from in vitro biopanning, GSC-IC2, which was the focus of this study.

Using a protein pull-down strategy, we identified that the cellular surface binding partner for GSC-IC2 on GSCs as Cadherin 2. Cadherin 2 is a transmembrane protein responsible for cell-cell adhesions and implicated in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, with upregulation during the mesenchymal phase.18 High expression of CDH2 has been associated with multiple malignancies and cancer stem cells, as well as increased anti-apoptotic activity.19 In glioma, CDH2 expression is associated with WHO glioma grade.20 A recent report demonstrated an increased expression of CDH2 in radioresistant GSCs.21

Our results indicate that GSC-IC2 was able to target glioblastoma tumor cells both in culture and in vivo. The specificity for targeting GSCs is unclear and the subject of future studies. Although the in vitro biopanning was directed against GSCs, the non-specific presence of Cadherin 2 on GSCs precludes the conclusion that GSC-IC2 is GSC specific. One of the limitations of the current study is that the peptide binding studies were with a single patient-derived GSC line. Further studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the peptides against other patient-derived glioblastoma stem cell lines will be needed to validate the peptide’s effectiveness to ubiquitously target GSCs and glioblastoma in general. GSC-IC2 peptide combined with a linker sequence demonstrated binding to 2 different patient-derived GSC cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S5). The ability of this peptide to target intracranially implanted tumors at a cellular level carries significant implications for the peptides as vehicles for targeting glioblastoma. Cellular detection of tumor growth through molecularly targeted imaging may supersede the current non-specific gold standard for imaging modalities used to detect brain tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging, which is the current standard of care for imaging, requires a certain threshold of tumor burden for the tumor to be visible. Detection of tumor growth at a cellular level may allow for earlier diagnosis or confirmation of recurrence. Molecular detection could also differentiate tumor recurrence from non-tumor radiographical progression, such as pseudoprogression or radiation necrosis. Peptide-based imaging modalities have been previously developed; however, they are limited to the specificity of the receptor on the targeted tumor cells.22 Our study verified that GSC-IC2 conjugated with Cyanine 5.5 may allow for visualization of tumor through live imaging, thereby verifying its effectiveness as an alternative to current clinical imaging modalities. A potential limitation of fluorophore labeling is light penetration, which may be circumvented by peptide conjugation with radionuclides that will allow for conventionally available PET/SPECT imaging.23

Our strategy to isolate Cadherin 2 as a peptide receptor target was in contrast to our previous studies, in which we applied peptides isolated from in vitro or in vivo biopanning to protein BLAST searches to see which cell specific protein the peptide may be representing, from which we derived EYA1. It is not likely that the peptide was binding to Cadherin 2 when the peptide was isolated. Given the short sequence of the peptide and that it may have been internalized into the cell, the peptides may have demonstrated non-specific binding intracellularly. In the current study, we aimed to isolate specifically the potential GSC cell surface receptor bound by our peptide of interest. After identifying the potential receptor proteins using mass spectroscopy, we targeted proteins located on the cell membrane and confirmed that Cadherin 2 appeared to be the receptor target. Although the same peptide was used to link to 2 different GSC proteins, the manner in which they were obtained was different and allows for the isolation of different targets. Our results verified the ability of using phage display against a specific cell type followed by receptor identification through protein pull down to isolate cell surface receptors, a technique that may be used to isolate novel cellular targets.

The development of novel peptides to target glioblastoma cells may allow future therapeutics to overcome the 2 major challenges to more effectively target and treat primary and metastatic brain tumors: specificity of cell targeting and penetration into the intracranial space. These challenges have long impeded the development of effective interventions for primary and metastatic brain tumors. Current treatment strategies almost inevitably result in tumor recurrence, as residual tumor cells, possibly dominated with stem-like properties, are resistant chemoradiation and recapitulate tumors.12,24 More effective treatments aimed at eradicating glioblastoma may depend on targeted therapeutics aimed at the subpopulations of tumor cells which are responsible for therapeutic resistance. Although GSC-IC2 appears to target Cadherin 2, which may select for a subpopulation of tumor cells in a mesenchymal phase, this may prove to be advantageous in future studies in which the peptide is used to augment focused targeting of cells that have a known resistance to chemoradiation.21,25 Expression of N-cadherin in glioma cells has also been associated with invasive potential and adhesion to endothelial cells, and this may explain the congregating of GSC-IC2 in the perivascular niche following in vivo delivery.26

Another challenge of therapeutic delivery to brain tumors is access. Due to the presence of the blood-brain barrier, therapeutics have been directly delivered to brain tumors through implantation of chemotherapy agents into the tumor bed following surgical resection or infusion through convection-enhanced delivery.27,28 However, even following implantation, distribution of the vector into the adjacent brain parenchyma can be limited.29 Among the advantages of isolating tumor targeting peptides via an in vivo biopanning strategy is that it allows for the selection of peptides which can target tumor cells following intravenous injection. This peptide selection process potentially eliminates nonspecific targeting peptides to reduce unwanted systemic targeting. Tumor targeting peptides can also be used for cell specific imaging modalities. In addition to developing peptide-based diagnostic imaging modalities, peptide tumor targeting can be used during surgical resection of tumors to augment intraoperative visualization of tumor tissue and improve the extent of surgical resection.30 Tumor-targeting peptides can also be used to modify delivery vehicles, such as viral vectors, nanoparticles, or immune-mediated therapies. These peptides are particularly promising for modification of such vectors, as their small size minimizes the possibility of steric interference.

The use of in vivo phage display biopanning to isolate peptides able to enter the central nervous system has its limitations, as the BBB could be compromised in the setting of a neoplasm. Therefore, access to the tumor may be facilitated by a breakdown of the BBB rather than by transport of the peptide across the barrier.31 The ability of the peptides to cross the BBB will need to be further examined. Studies using nonspecific targeting peptides indicate that there is fluorescent signal at the site of the tumor. However, we found that the decrease in signal is much more rapid compared to the targeting peptide, indicating an expulsion of the nonspecific targeting peptide.

Conclusion

The specificity of GSC-IC2 for targeting GSCs demonstrates that isolation of a peptide for selective cell targeting can be achieved through a combination of in vitro and in vivo phage display biopanning. The ability of GSC-IC2 to target intracranial glioblastoma following intravenous injection demonstrates the possibility for its use in the development of improved theragnostic strategies aimed at glioblastoma. Further studies will assess the interaction of GSC-IC2 and the BBB, as well as direct delivery methods such as intraparenchymal, intratumoral, or intrathecal delivery methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by the Flow Cytometry and the Proteomics & Metabolomics Core Facilities at the Moffitt Cancer Center, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). We thank Paul Fletcher and Daley Drucker of H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institution for editorial assistance. They were not compensated beyond their regular salaries. We thank the Rich and Bao laboratories for helpful suggestions. We also thank Dr. Daniel Abate-Daga, Department of Immunology, Moffitt Cancer Center, who was co-PI of the Moffitt-Celgene Innovative Study Grant which provided funding for this work.

Contributor Information

JongMyung Kim, Department of Neuro-Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institution, Tampa, FL, USA.

Marine Potez, Department of Neuro-Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institution, Tampa, FL, USA.

Chunhua She, Department of Neuro-Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institution, Tampa, FL, USA.

Ping Huang, Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Qiulian Wu, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Shideng Bao, Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Jeremy N Rich, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Department of Neurology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

James K C Liu, Department of Neuro-Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institution, Tampa, FL, USA; University of South Florida, Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL, USA.

Funding

NIH CA217066 (B.C.P.); CA184090, NS091080, NS099175 (S.B.); CA197718, CA154130, CA169117, CA171652, NS087913, NS089272, NS103434 (J.N.R.); The Congress of Neurological Surgeons Tumor Fellowship, Moffitt-Celgene Innovative Study Grant, American Cancer Society #IRG-91-022-19 (J.K.C.L.).

Conflict of Interest

J.N.R. declared advisory role with Synchronicity Pharma. All of the other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

J.M.K.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. M.P., C.S.: collection and/or assembly of data, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. P.H.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing. Q.W., B.P.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation. S.B.: financial support, data analysis and interpretation, final approval of manuscript. J.N.R.: conception and design, financial support, administrative support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript. J.L.: conception and design, financial support, administrative support, provision of study material or patients, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary material).

References

- 1. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987-996. 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1954-1963. [in Eng]. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang J, Yan J, Liu B.. Targeting EGFRvIII for glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Lett. 2017;403:224-230. [in Eng]. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li YM, Hall WA.. Cell surface receptors in malignant glioma. Neurosurgery. 2011;69(4):980-94; discussion 994. 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318220a672.discussion994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang D, Li W, Zhang H, Mao Q, Xia H.. A targeting peptide improves adenovirus-mediated transduction of a glioblastoma cell line. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(5):2093-2098. 10.3892/or.2014.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Rourke DM, Nasrallah MP, Desai A, et al. A single dose of peripherally infused EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(399):eaaa0984. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown CE, Aguilar B, Starr R, et al. Optimization of IL13Rα2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells for improved anti-tumor efficacy against glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2018;26(1):31-44. [in Eng]. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith GP. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science. 1985;228(4705):1315-1317. 10.1126/science.4001944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tatari N, Maich WT, Salim SK, et al. Preclinical testing of CAR T cells in a patient-derived xenograft model of glioblastoma. STAR Protoc 2020;1(3):100174. [in Eng]. 10.1016/j.xpro.2020.100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim J, She C, Potez M, et al. Phage display targeting identifies EYA1 as a regulator of glioblastoma stem cell maintenance and proliferation. Stem Cells. 2021;39(7):853-865. 10.1002/stem.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu JK, Lubelski D, Schonberg DL, et al. Phage display discovery of novel molecular targets in glioblastoma-initiating cells. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(8):1325-1339. 10.1038/cdd.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756-760. 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowman RL, Wang Q, Carro A, Verhaak RGW, Squatrito M.. GlioVis data portal for visualization and analysis of brain tumor expression datasets. Neuro Oncol 2017;19(1):139-141. [in Eng]. 10.1093/neuonc/now247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Federici T, Liu JK, Teng Q, Yang J, Boulis NM.. A means for targeting therapeutics to peripheral nervous system neurons with axonal damage. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(5):911-8; discussion 911. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255444.44365.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cui Y, Zhang M, Zeng F, et al. Dual-targeting magnetic PLGA nanoparticles for codelivery of paclitaxel and curcumin for brain tumor therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(47):32159-32169. 10.1021/acsami.6b10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morshed RA, Muroski ME, Dai Q, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide-modified gold nanoparticles for the delivery of doxorubicin to brain metastatic breast cancer. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(6):1843-1854. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beck S, Jin X, Yin J, et al. Identification of a peptide that interacts with Nestin protein expressed in brain cancer stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8518-8528. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA.. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871-890. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sinha G, Ferrer AI, Ayer S, et al. Specific N-cadherin-dependent pathways drive human breast cancer dormancy in bone marrow. Life Sci Alliance 2021;4(7):e202000969. [in Eng]. 10.26508/lsa.202000969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen Q, Cai J, Jiang C.. CDH2 expression is of prognostic significance in glioma and predicts the efficacy of temozolomide therapy in patients with glioblastoma. Oncol Lett 2018;15(5):7415-7422. 10.3892/ol.2018.8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Osuka S, Zhu D, Zhang Z, et al. N-cadherin upregulation mediates adaptive radioresistance in glioblastoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(6):e136098. 10.1172/JCI136098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cordier D, Forrer F, Kneifel S, et al. Neoadjuvant targeting of glioblastoma multiforme with radiolabeled DOTAGA-substance P - results from a phase I study. J Neurooncol. 2010;100(1):129-136. 10.1007/s11060-010-0153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chatalic KL, Kwekkeboom DJ, de Jong M.. Radiopeptides for imaging and therapy: a radiant future. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(12):1809-1812. 10.2967/jnumed.115.161158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weller M, van den Bent M, Tonn JC, et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):e315-e329. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang S, Zhang J, Wang K, et al. ADAMTS1 as potential prognostic biomarker promotes malignant invasion of glioma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;28(1):52-68. [in Eng]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu D, Martin V, Fueyo J, et al. Tie2/TEK modulates the interaction of glioma and brain tumor stem cells with endothelial cells and promotes an invasive phenotype. Oncotarget 2010;1(8):700-709. [in Eng]. 10.18632/oncotarget.101204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ostertag D, Amundson KK, Lopez Espinoza F, et al. Brain tumor eradication and prolonged survival from intratumoral conversion of 5-fluorocytosine to 5-fluorouracil using a nonlytic retroviral replicating vector. Neuro Oncol 2012;14(2):145-159. 10.1093/neuonc/nor199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yin D, Zhai Y, Gruber HE, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery improves distribution and efficacy of tumor-selective retroviral replicating vectors in a rodent brain tumor model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20(6):336-341. 10.1038/cgt.2013.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sampson JH, Archer G, Pedain C, et al. Poor drug distribution as a possible explanation for the results of the PRECISE trial. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(2):301-309. 10.3171/2009.11.JNS091052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stummer W, Tonn JC, Mehdorn HM, et al. Counterbalancing risks and gains from extended resections in malignant glioma surgery: a supplemental analysis from the randomized 5-aminolevulinic acid glioma resection study. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(3):613-623. 10.3171/2010.3.JNS097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davies DC. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in septic encephalopathy and brain tumours. J Anat. 2002;200(6):639-646. 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary material).