Abstract

Purpose

The rate of female committals to prison has grown rapidly in recent years. Women in prison are likely to have trauma histories and difficulties with their mental health. This paper aims to synthesise the findings of qualitative literature to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of women in the context of prison-based mental health care.

Design/methodology/approach

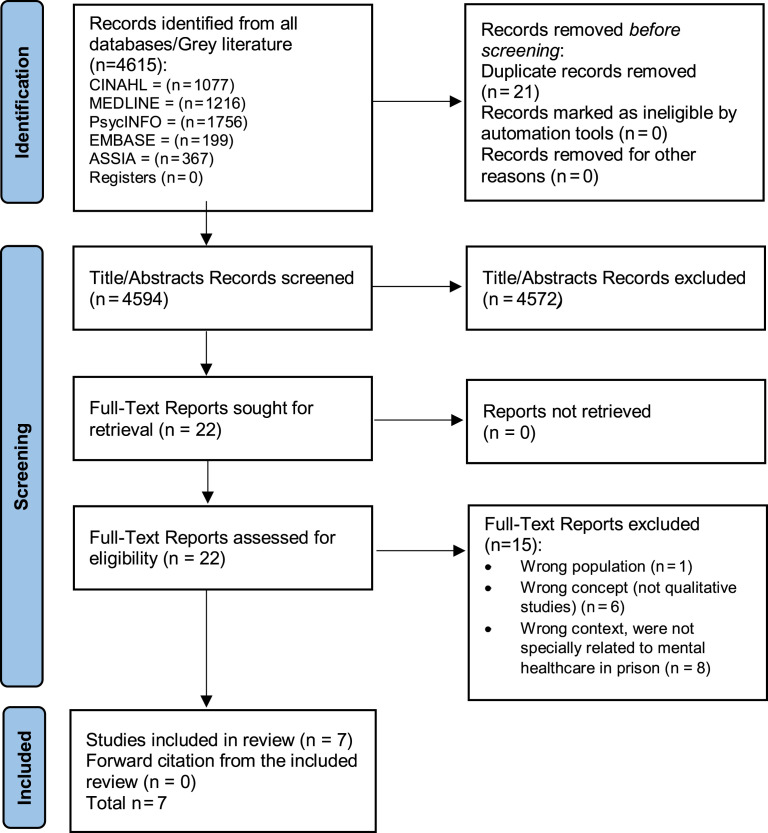

A systematic search of five academic databases, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Psychological Information Database (PsycINFO), Excerpta Medica DataBASE (EMBASE) and Medline, was completed in December 2020. This study’s search strategy identified 4,615 citations, and seven studies were included for review. Thomas and Harden’s (2008) framework for thematic synthesis was used to analyse data. Quality appraisal was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al., 2015).

Findings

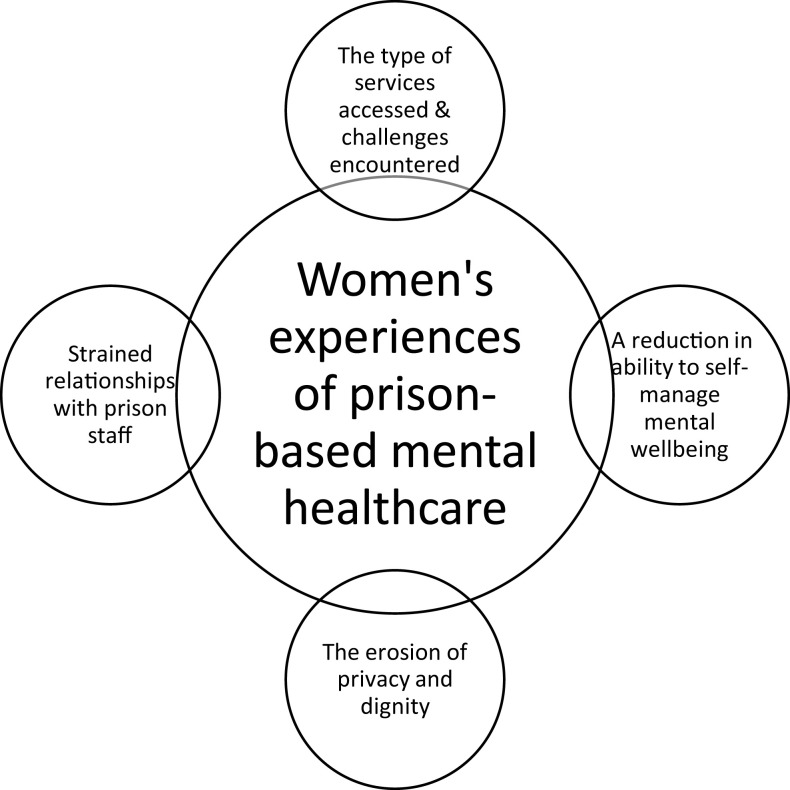

Four analytic themes were identified that detail women’s experiences of prison-based mental health care: the type of services accessed and challenges encountered; a reduction in capacity to self-manage mental well-being; the erosion of privacy and dignity; and strained relationships with prison staff. There is a paucity of research conducted with women in the context of prison-based mental health care. The findings suggest there is a need for greater mental health support, including the need to enhance relationships between women and prison staff to promote positive mental health.

Originality/value

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted on the experiences of women in the context of prison-based mental health care.

Keywords: Mental health, Women prisoners, Prison, Service provision, Qualitative synthesis, Women’s experiences

Introduction

Since 2000, the number of women in prison has increased by approximately 53%, resulting in a worldwide female prison population estimated at 714,000 (Walmsley, 2017). Internationally, prison populations and committal rates vary. The USA has seen a 700% increase in female incarceration between 1980 and 2019, with approximately 222,455 women in prison and jail between the years 2018 and 2019 (Carson, 2020; Zeng, 2020). However, Australia saw a 10% reduction of women in prison from 2019 to 2020, which may be the result of pandemic restrictions implemented in various states and territories (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). In the UK, women account for 4.1% of the overall prison population (World Prison Brief, 2021), where the average female prison sentence is 11.3 months (Ministry of Justice, 2019), and in Ireland, the average duration of prison sentences are three months or less (Irish Prison Service, 2019a). In the UK, it is estimated that 73% of women serving sentences of 12 months or less are reconvicted within a year of release (Prison Reform Trust, 2021). The effectiveness of short prison sentences has been debated as they are less effective at reducing reoffending when compared with suspended or community sentences (O’Donnell, 2020; Gascón, 2020). Indeed, the prison has a negative impact on women in the context of mothering, homelessness and employment (O’Malley and Devaney, 2016; Powell et al., 2017; Prison Reform Trust, 2021) and with only two women’s prisons in Ireland and 12 in the UK, many women are detained far from home, impacting on the visitation of children and families (Irish Prison Service, 2021; Ministry of Justice, 2021a).

Mental health problems are overrepresented in the female prison population; approximately 80% have a mental health diagnosis (World Health Organisation, 2021). Women in prison are five times more likely to experience mental health difficulties than women in the general population (Tyler et al., 2019). Prevalence rates for psychotic illness among women in prison are estimated at 3.9%, major depression at 14.1%, alcohol misuse at 10%–24%, drug misuse at 30%–60% (Fazel et al., 2016) and post-traumatic stress disorder at 21.1% (Baranyi et al., 2018). Women in prison are susceptible to self-harm, with approximately 30% engaging in self-harming behaviours (Ministry of Justice, 2017; Irish Prison Service, 2020; Ministry of Justice, 2021b). In addition, women in prison are up to 20-times more likely to die by suicide and 36 times more likely to die by suicide one-year post-release when compared with those in the general population (Fazel and Benning, 2009; Pratt et al., 2010). Women often experience domestic, physical, emotional and sexual abuse prior to imprisonment giving rise to complex and often unresolved trauma that may be criminogenic (Gunter, 2012; Alves et al., 2016). A correlation exists between trauma and the development of mental health difficulties (Karlsson and Zielinski, 2018; Jewkes et al., 2019), which are factors for a range of adverse outcomes in prison and on release, including being victims of violence and assault (Caravaca-Sánchez et al., 2014) and reoffending (Baillargeon et al., 2009).

Recently, there has been an increased call for gender-specific mental health care in prisons (Public Health England, 2018). Internationally, gender-specific care is advocated for in the Bangkok Rules (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2012), whereas the Kyiv Declaration made recommendations to review policies and services to meet the needs of women in prison (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2009). Mental health services have adopted trauma-informed approaches (Muskett, 2013; Department of Health, 2020), which should also inform prison-based mental health care.

A recent meta-synthesis by Ratcliffe and Stenfert Kroese (2021) provides an overview of women’s experiences of forensic settings in the UK but does not include prison settings. Other systematic reviews of mental health interventions for prisoners tend to focus on medication and psychotherapy (Fazel et al., 2016), CBT and mindfulness-based therapy (Yoon et al., 2017) and interventions for early adults (Givens et al., 2021), but neglect to consider gender-specific differences or make gender-specific recommendations. Given that the rate of women being sentenced to prison is growing more rapidly than for men (Central Statistics Office, 2019), there is a greater need to focus on the female prison population. Therefore, this review aims to synthesise findings from qualitative research conducted with women in prison to identify the state of the evidence in this area and gain a deeper understanding of prison-based mental health care from women’s perspectives.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statements (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). The study protocol is registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42021240407). A population, concept and context (PCC) framework was used to guide the selection of terms used in the search strategy and to formulate the following research question:

RQ1.

What are the experiences of women in prison in the context of prison-based mental health care?

Search strategy

A preliminary search of the Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Open Grey database and PROSPERO was undertaken to ensure no other related systematic reviews had been conducted. A systematic search of five databases was conducted in December 2020; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Medline, Psychological Iinformation Database, Excerpta Mmedica DataBASE and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. There was no restriction on language, geographical origin or publication date owing to a dearth of research in this subject area. The terms in the PCC framework were searched as keywords, topics, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and combined using Boolean operators (Table 1). The search protocol was developed with a librarian and tested against preselected articles. Forward citation tracking of retrieved articles was conducted by hand searching reference lists of returned articles to maximise the yield of relevant papers.

Table 1.

PCC Framework

|

Population Women prisoners with mental ill-health |

Woman OR women OR female OR prisoner* OR imprison* OR convict* OR inmate* OR offender* OR sentence* OR jail OR correctional OR criminal justice OR incarcerat* OR criminal* OR remand OR felon OR penitentiar* OR detain* OR penal OR mental health OR mental illness OR mental disorder OR mental health problem* OR mental ill-health OR mental ill health OR psychiatric problem* OR psychiatric disorder* OR psychiatric illness* OR psychological problem* OR psychological issue* OR psychological illness* OR symptom* AND |

|

Concept Qualitative experiences |

Experience* OR attitude* OR perceptions OR opinions OR thoughts OR beliefs OR satisfaction OR satisf* OR qualitative OR qualitative research AND |

|

Context Mental health care in prison |

Mental health service OR mental health care OR intervention* OR care OR support* OR help OR treatment |

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if the primary research approach was qualitative; they reported on women in prison who had accessed prison-based health care for mental ill-health and sampled women were over 18 years with self-reported or diagnosed mental health problems. Studies were excluded if they did not report primary qualitative narratives; it was not possible to disaggregate data of female participants in studies that included male participants, and they used quantitative designs, expert opinion or consensus statements.

Study selection

All citations were uploaded to Zotero for de-duplication and exported to Colandr (Cheng et al., 2018) for title/abstract and full-text screening. Two authors (AB and AG) independently assessed titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria, and articles were excluded by agreement with all authors. Full-text copies of all remaining articles were independently screened by (AB, AH and AG) against eligibility criteria. Any conflict regarding the eligibility criteria of individual studies was resolved by discussion.

Quality appraisal.

Quality appraisal of the included studies was independently undertaken by AB and AH using the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al., 2015) to assess the methodological quality, rigour, trustworthiness, relevance and results. This tool does not recommend the use of a scoring system; instead, it contains 10 questions rated as “yes”, “no”, “unclear” or “not applicable”. The quality weightings of the included studies (Table 2) were considered when reporting and discussing the results.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal

| Joanna Briggs Institute Check List for Qualitative Research: Questions | Plugge et al. (2008) | Bowen et al. (2009) | Kenning et al. (2010) | Marzano et al. (2011) | Caulfield (2016) | Ahmed et al. (2016) | Jacobs and Giordano (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | U | Y | U | Y | U | U | U |

| Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | N | N | N | N | N | N | U |

| Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | U | U | U | N | N | U | Y |

| Are the participants, and their voices adequately represented? | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | N |

| Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Data extraction and analysis.

A Microsoft Excel data extraction form was developed and piloted for extracting information from each study. This included author, year, country of origin, study aim, sample achieved, population characteristics and categories related to recruitment and data collection. Information related to how women accessed mental health care in prison, women’s experiences of prison-based mental health care, barriers and enablers to accessing prison-based mental health care and reported themes and recommendations were extracted. Thematic synthesis using the Thomas and Harden (2008) framework was undertaken on qualitative data. Studies were read and re-read by all team members and qualitative data relevant to the question was extracted and coded inductively, keeping the synthesis close to the original findings. Finally, descriptive themes were analysed and, through an iterative process of review and inference, analytic themes were identified with reference to the review question.

Results

Search outcomes

The number of studies that identified study selection against the eligibility criteria and reasons for exclusion is depicted in Figure 1. The search strategy yielded 4,615 studies from five databases and none from grey literature sources. After removing duplicates (n = 21), 4,594 studies were retained for the title and abstract screening. A total of 22 citations met the eligibility criteria for full-text screening, from which a final total of seven papers were eligible for this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Study characteristics

Table 3 presents a summary of the characteristics of the seven included studies that were conducted between 2008 and 2018. One study focused specifically on psychiatric services (Jacobs and Giordano, 2018), with the remaining studies focusing on general health care or different aspects of mental health such as self-harm, suicide and medication. Two studies (Bowen et al., 2009; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018) were conducted on female and male participants; however, only data related to female participants were extracted. Three studies were conducted in England (Plugge et al., 2008; Kenning et al., 2010; Caulfield, 2016), two across England and Wales (Bowen et al., 2009; Marzano et al., 2011) one in Canada (Ahmed et al., 2016) and one in the USA (Jacobs and Giordano, 2018). Study designs were mostly qualitative; Jacobs and Giordano (2018) used an inductive qualitative approach by using techniques from Interpretive Phenomenology and Constructivist Grounded Theory; Bowen et al. (2009) used a narrative approach. Four studies (Plugge et al., 2008; Kenning et al., 2010; Caulfield, 2016; Ahmed et al., 2016) were qualitative descriptive. Marzano et al. (2011) used mixed methods from which only qualitative data were extracted.

Table 3.

Study characteristics

| Author, year and Country | Ethical approval | Study aim and methodology | Data collection methods | Recruitment methods | Data collection process | Data analysis | Findings/key themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Plugge et al. (2008) Southern England |

South East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (04/MRE01/14) | To explore women prisoners’ experiences of health care provision as part of a wider project examining the health impact of imprisonment on women. Qualitative descriptive (inferred) |

Focus groups ×6: Participants (n = 37) Audio recorded Semi-structured, individual interviews: Participants (n = 12) Audio recorded |

Focus groups –purposive sampling using local inmate directory Interviews – convenience sampling from women participating in a longitudinal questionnaire over a 3-month period |

Location: focus groups – held in a private room in the prison health centre Interviews – held in private room in the prison health centre |

Thematic analysis (framework not reported) N-vivo (v7) |

Application process to access health care is a protracted process. Nurses perceived as “gatekeepers” and “bodyguards” Health-care staff competence questioned by participants “rejects”, “unprofessional”, unqualified” Lack of privacy when discussing health care issues |

|

Bowen et al. (2009) England & Wales |

South East Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee | Drawing on narrative accounts of prisoners and the staff they must negotiate, this paper considers the prescribing and taking of medication related to the management of mental health problems in a prison context. Qualitative – narrative synthesis |

Semi-structured, individual interviews: Participants (n = 39) Audio recorded Non-participative observation |

Purposive sample of: Those known to have a recent history of mental disorder Were currently withdrawing from drug/alcohol misuse Had experience of processes for the management of suicide/self-harm Had been in prison for at least two weeks and less than approximately 8 months |

Interview location: not stated Interview privacy: Not stated Non-participative observation location: Reception, induction, residential, in-patient and detoxification units. Participant observation duration: between 2 and 7 h in each location. |

Thematic analysis closely following Miles and Huberman (1984) “Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft” | Autonomy – lack of autonomy impacted the women’s ability to self-manage Lack of personal control over medication taking Changes to medication regimes disruptive to routines and cause anxieties, confusion and distress Anti-therapeutic relationships between participants and staff |

|

Kenning et al. (2010) North West England Ealing and West London Mental Health Trust Ethics Committee |

Central and Eastern Cheshire Primary Care Trust. | To compare attitudes of women prisoners who self-harm with the attitudes and perspectives of different prison staff and to examine the possible impact on the delivery and development of prison services. Qualitative descriptive (inferred) |

Semi-structured, individual interviews Participants (n = 15) Audio recorded |

Purposive sample according to where the women prisoners were housed within the prison. | Interview location: not stated | Grounded Theory | Health care staff were positively perceived. Prison officer staff perceived as “cold” Imported factors (modifiers brought in to prison by women) relating to self-harm behaviours such as past histories of abuse Situational factors (modifiers existing as a result of the women’s current situations) such as being on basic regime The purpose of self-harming behaviours was to control feelings of anger, frustration or a form of self-punishment |

|

Marzano et al. (2011) England and Wales |

Central Office for Research Ethics Committee (06/MRE12/83) Prison Service (PG 2006 063) |

To identify socio-demographic, criminological and psychological variables associated with near-lethal self-harm. To provide further understanding of this behaviour and inform preventative initiatives. Mixed-methods (qualitative methods were descriptive, inferred) |

Semi-structured, individual interviews Participants (n = 120) (60 with a history of self-harm, 60 with no history of self-harm) Audio recorded |

Purposive sample of women who engaged in potentially lethal methods of self-harm | Interview location: Private room | Thematic analysis (no framework reported) N-Vivo (v8) |

Negative relationships with staff were reported as antecedents to near-lethal self-harm. Being treated better by prison staff reported as a way to prevent self-harm behaviours in addition to not being in prison, having more distractions and time out of cell, more help with mental health problems, reduced access to means to self-harm, being in a shared cell and receiving counselling |

| Caulfield (2016) England |

Associated University | To explore the suggestion that the prison environment exacerbates the incidence and severity of mental health issues. Qualitative descriptive (inferred) |

Semi-structured, individual interviews Participants (n = 43) Audio recorded |

Convenience sample using letters, posters, peer recruiters, prison officer recruiters, a prison television interview | Interview location: Not stated Privacy: only researcher and research participant present |

Thematic analysis (no framework reported) N-Vivo |

Positive experiences about prison-based health care included having access to therapy/prescriptions on a regular basis Being employed helped to reduce symptoms of depression Doctors advising that medication would suffice when counselling requested |

|

Ahmed et al. (2016) Canada |

University of Alberta Health Ethics Research Board | To report on female inmates’ perceptions of the barriers they face when accessing health care during incarceration, the impact this has on health during incarceration and in the community and implications for correctional health care practice. To show how these were used to inform the development of a resource aimed at improving functional health literacy regarding accessing correctional health care services Qualitative descriptive (inferred) |

Focus groups Participants (n-12) Audio recorded |

Purposeful sample from general correctional facility population meeting eligibility criteria for participation | Focus group location: Not stated | Thematic analysis (no framework reported). N-Vivo 10 |

Participants reported being unaware of services available to them because they did not see care being provided or because of poor health literacy Not being able to take a taxi to a medi-centre and manage self Being afraid of asking for help or further information when required Feeling “sloughed off” by staff Health care applications being sent back Having information provided that’s too simplistic and not reflective of the seriousness of the subject matter Reading other prisoners health care application forms |

|

Jacobs and Giordano (2018) USA |

All procedures in accordance with ethical standards of the national and/or institutional research committee and 1964 Helsinki Declaration | To illuminate service recipient’s perspectives on jail mental health care. To identify the elements of care most salient to participants while obtaining a unique perspective on service potential and limits. Qualitative inductive utilising techniques from Interpretative Phenomenology and Constructivist Grounded Theory |

Semi-structured, individual interviews Participants (n = 19) Audio recorded |

Purposeful sample of those who have a psychiatric diagnosis, had at least two experiences of jail detainment in the county, one of which occurring within two years of the interview | Interview location: Not stated | Techniques used in Constructivist Grounded Theory Techniques used in Interpretive Phenomenology |

When medication regimes were adjusted this was mentally and physically harmful as well as discriminatory Assessment of mental health was overlooked on committal to prison No availability of “out of hours” crisis intervention services for prisoners |

Six studies (Plugge et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2009; Kenning et al., 2010; Marzano et al., 2011; Caulfield, 2016; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018) used semi-structured, one-to-one interviews to collect data. Ahmed et al. (2016) used focus groups. In addition to interviews, Plugge et al. (2008) used focus groups (n = 6) and Bowen et al. (2009) added non-participant observation to complement their data collection. Marzano et al. (2011) and Plugge et al. (2008) conducted interviews in a private room in a prison setting with no staff present. Caulfield (2016) does not report the interview setting, only that the participant and researcher were present during the interview. Kenning et al. (2010), Jacobs and Giordano (2018) and Bowen et al. (2009) did not report where their interviews were held.

Participant characteristics.

The collective review sample was 255 female participants, and individual female study sample sizes ranged from 4 to 120. All participants were currently serving a prison sentence apart from those in Jacobs and Giordano (2018), who were women under court supervision after recent detention. Participants in Ahmed et al. (2016) were all on remand; Marzano et al. (2011) reported that in their total sample, 25 participants (n = 25) were on remand whilst 95 participants (n = 95) were sentenced. Plugge et al. (2008) reported six participants (n = 6) in the focus groups were on remand, with 31 participants (n = 31) sentenced; however, no status was provided for interview participants. Kenning et al. (2010) reported 11 participants (n = 11) were sentenced whilst four (n = 4) were on remand. Bowen et al. (2009) and Caulfield (2016) did not report on participant status.

Participant ages ranged from 18 to 60 years, and of the studies that reported a mean age, the means ranged from 25.5 to 45 years. Six of the included studies reported some detail on participant ethnicity. However, as not all studies reported in the same manner, it is not possible to provide an aggregate. For the six studies that did report ethnicity (Plugge et al., 2008; Kenning et al., 2010; Marzano et al., 2011; Caulfield, 2016; Ahmed et al., 2016; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018), participants were described as White, British Black, Black Caribbean, Aboriginal, African, African/Caribbean and mixed-race. Two studies reported specifically on the mental health problems experienced by women; Caulfield (2016) reported participants had mental health and emotional difficulties prior to their current sentence. Participants (n = 15) in Kenning et al. (2010) all engaged in self-harming behaviours of which 11 (n = 11) had a history of self-harm outside of prison. Although Bowen et al. (2009) and Jacobs and Giordano (2018) reported on mental health problems, they did not provide a breakdown between male and female participants.

Quality of studies

Overall, the body of evidence was of mixed quality, and the results of the methodological quality assessment are outlined in Table 4. In all but one study, Jacobs and Giordano (2018) reported receiving ethical approval. Jacobs and Giordano (2018) specified the study was compliant with ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and the 1964 Helsinki declaration. Although the studies provided variable descriptions on the data collection methods, none made explicit the philosophical perspective underpinning the research, and the exact methodology was not described by four of the included studies (Plugge et al., 2008; Kenning et al., 2010; Caulfield, 2016; Ahmed et al., 2016). This led to the reviewers having to make inferences about the methodology from the descriptions provided. None of the studies provided a clear statement that located the researcher culturally or theoretically. Only Jacobs and Giordano (2018) addressed the influence of the researcher on the research and vice-versa. The sample size of females in some studies was small; additionally, as not all studies reported on participant demographics, it was difficult to know if an adequate representation of women in prison was achieved.

Table 4.

Illustrative quotations organised around themes

| Analytical themes | Quotations from participants in primary studies |

|---|---|

| 1. The type of services accessed and challenges encountered | “We don’t even know about half the stuff that they offer here” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 208). “I’m sure there could be a lot of great resources for woman but when you’re asking for it and don’t see it, it’s kind of … unbelievable. Yeah, it’s very discouraging and tiresome” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 209). “I only started getting them 3 days after I came in. I had to wait for my medical records from GGGG [name of prison from where the prisoner had just been transferred] and until that came they couldn’t give us any medication. Thing is, I’d been on Methadone there … Yeah, it’s different in different goals … like in GGGG, if you’re on a scripts on the ‘out’, they give you what they call a ‘maintenance script’ inside, of a smaller dose. Whereas I was on 50 ml on the outside, so in GGGG I was getting 30 ml of Methadone and a sleeping tablet. And that was it. That was doing it. But when I came here, they told me they don’t do Methadone … they don’t give you sleeping pills. It’s a total no-no. So I was ill, very ill.” (Bowen et al., 2009; p. 7). “So, it wasn’t until I actually got to prison and I was forced to take my pills that things started to look good. And I thought, oh no, if I’d have done this years ago, I wouldn’t be here now” (Caulfield, 2016; p. 222). “Helpful with [her] bi-polar. They gave me medications” (Jacobs and Giordano, 2018; p. 270). “When you need to see a doctor you have to put in an application, you have to wait too long and mainly because I’m quiet and because I don’t fuss” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e3). “So we put in a request form but it never gets taken care of, so then people get sick [or] mad and sad or their mental health issues get worse” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 201) |

| 2. A reduction in ability to self-manage mental well-being | “… we can’t you know, take a cab and go to a medi-centre down the road and go, you know what I mean, by ourselves.” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 201). “the doctor said that anti-depressants would help me” (Caulfield, 2016, p. 223). “Because I’m on Valium-based medication – what everybody wants – I’m on Methadone. I kept giving a girl my Methadone all the time. She was bullying me into it” (Marzano et al., 2011; p. 877). “I was on Trazadone and they [i.e. specifically the prison doctor] changed it to Venlafaxine … and that one I’ve forgot the name of, for the bi-polar, they just stopped them” (Bowen et al., 2009; p. 4). “I didn’t bother. I was more concerned about taking my medication, and I didn’t want to say anything ‘cos I thought if I said anything they might just take me off it … So I just kept my mouth shut basically. I daren’t say anything. You know what they’re like” (Bowen et al., 2009; p. 6). “He’s telling me he’s not giving no anti-depressants and I said “but I get it from my doctor” and he said “well, we’ll have to get in contact”… I’m telling him that antidepressants [are] what I take and he just says “no, no, no, you just want it because other people take it” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e4). “I’ve seen a psychiatrist for two-and-a-half, nearly three years I think, and he’s put me on medication, which I was quite happy to be on. It stopped when I come in here. Everything stopped and I’m a bit cheesed off” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e4). “I’ll just sit there thinking about my past, you know, how I’ve come to prison in the first place, I’ve let my kids down, you know and then I get really, really, really worked up and then I just have to see blood to, you know, relieve my pain” (Kenning et al., 2010; p. 278) |

| 2. The erosion of privacy and dignity | “I’ve read lots of request forms (giggle). I’m bad for it, but I mean like, if some girl has a sensitive issue why would she want to write that and let the guards read it [too]” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 209). “I find it really upsetting because it’s just another indication of, that you’re not treated … as if you’re entitled to the same standard of health care that you would enjoy outside” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e4). “I’m serious about staying off drugs. I’m serious about all this stuff and I don’t want to sit here and read about ‘Sally and Joe’ and their little problems” (Ahmed et al., 2016; p. 212) |

| 4. Strained relationships between women and prison staff | “I just didn’t want to be around. I had enough of these [staff] pushing me and everything. I did” (Marzano et al., 2011; p. 877). “They’re cold in their voice, they’re cold in the way they speak to you, they’re cold as in when you’re crying they just shut the door in your face” (Kenning et al., 2010; p. 280). “Stop being stereotypical and thinking that we want drugs” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e5). “There’s so much coming and going, like people coming in, people leaving, people going to different wings, going to court, coming back – your file’s gone and it’s come back, it’s come up late. But I think some of it is not their fault, do you know what I mean, I’m not blaming it 100% on them” (Plugge et al., 2008; p. e6) |

Four analytic themes

Four main themes were elected from our findings:

the type of services accessed and challenges encountered;

a reduction in ability to self-manage mental well-being;

the erosion of privacy and dignity and;

strained relationships with prison staff. Figure 2 presents an overview of women’s experiences of prison-based mental health care.

Figure 2.

Thematic summary diagram

Table 4 shows the grouped findings from the studies, and quotations are included to illustrate the theme from study participants.

Theme 1 – the type of services accessed and challenges encountered.

The first analytic theme describes women’s experiences of accessing mental health services whilst in prison.

None of the studies made explicit the mental health services available to women, although the women themselves mentioned in their narratives Social Workers (Bowen et al., 2009; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018), Psychologists (Bowen et al., 2009; Caulfield, 2016; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018), Psychiatrists (Caulfield, 2016), Clinical Staff (Marzano et al., 2011; Jacobs and Giordano, 2018), Nurses (Plugge et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2009), Doctors (Plugge et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2009; Caulfield, 2016), Occupational Therapists (Bowen et al., 2009) and Counsellors (Caulfield, 2016). The importance of timely and regular access to mental health services in prison was highlighted by women in some studies. Women described positive health outcomes from being able to attend counselling while in prison and being able to access medication on a regular basis (Caulfield, 2016). Similarly, women described psychiatric services as helpful with their mental health problems because they “gave me medications” (Jacobs and Giordano, 2018).

Conversely, women in Ahmed et al.’s (2016) study described several challenges in accessing mental health care; women reported not knowing what services were available, which the authors suggest was the result of poor health literacy, and some women were unable to read health information material and felt embarrassed or fearful when asking for help. Another challenge was the application process used to access health care, which required women to complete a form stating why they needed to see particular health-care professional. This process was described as taking “too long”, with significant delays (Plugge et al., 2008). Some applications were reported to be refused or not responded to, resulting in a decline in women’s health status (Ahmed et al., 2016). Being refused access to health practitioners or witnessing care not being provided was described as “discouraging and tiresome”; thus, women felt that asking for help was futile, and they chose not to write subsequent requests (Ahmed et al., 2016). Women transferred within the prison system described a lack of continuity of care, as prescriptions were sometimes changed when women moved prisons, and in the context of drug detoxification, women describe becoming “very unwell” as a result of these practices (Bowen et al., 2009).

Theme 2 – a reduction in ability to self-manage mental well-being.

The second analytic theme outlines how women experienced a reduction in their ability to self-manage their mental well-being because their civil liberties had been curtailed.

A prison sentence results in the removal of an individual’s freedom, thus reducing capacity to self-manage. Women describe not being able to take a taxi to a medi-centre, which impacted their ability to manage their own health care needs (Ahmed et al., 2016). Women reported that their usual self-medication practices were curtailed, resulting in disruptions to the strategies they used to control symptoms (Bowen et al., 2009). Women also reported “reluctance” to engage with medical staff if dose discrepancies were noted out of fear that medication would be completely discontinued (Bowen et al., 2009). Changes were made to their prescriptions by prison doctors without providing a rationale or without consultation, a practice that increased women’s anxiety about how they would cope (Bowen et al., 2009). Similarly, women reported their community prescriptions were sometimes discontinued despite informing prison health-care staff of existing dose regimens, and in the context of drug detoxification, this resulted in women being unable to sleep or manage symptoms of withdrawal (Plugge et al., 2008). Some participants reported being “bullied” by other prisoners for the medication (Marzano et al., 2011). When a participant asked for counselling in addition to the medication they were refused as “the doctor said that anti-depressants would help” further compounding this lack of self-management (Caulfield, 2016).

The purpose of self-harming behaviours used by women in prison was described as a means of coping with emotions and as a way of relieving frustration and pain, indicating a reduction in adaptive self-management skills (Kenning et al., 2010). Precipitating factors related to self-harming behaviours consisted of being denied certain requests, being put on “basic regime” and feelings of “disempowerment from being in prison” (Kenning et al., 2010). These findings demonstrate the extremes women engaged with to feel a sense of mastery over their lives and experiences.

Theme 3 – the erosion of privacy and dignity.

The third analytic theme describes the erosion of women’s privacy and dignity and how prison staff, as well as the women themselves, were the perpetrators of a reduction of privacy and dignity.

Women’s privacy was eroded by nursing staff when medical problems were discussed in prison corridors and at medication “hatches” (Plugge et al., 2008). In addition, nursing staff eroded privacy by maintaining a presence during medical consultations and by acting as “gatekeepers” and “bodyguards” when women met with doctors. Women’s dignity was eroded when nurses intervened to “interpret [your] symptoms for you” as opposed to letting women recount their own stories (Plugge et al., 2008). However, the erosion of privacy was not unique to health-care staff, with women themselves being complicit by reading health care application forms belonging to their peers (Ahmed et al., 2016). Women describe reading health care applications that were left “on the panel” and question why a woman would detail sensitive information on these forms with the knowledge that anyone could read them (Ahmed et al., 2016). Women described being “looked down” on by prison staff because they were in prison and that care provided was sub-standard compared to community care (Plugge et al., 2008). In the context of dignity, health information was described as being too simple and almost patronising, by not communicating the serious nature of the illnesses within the information provided and by not taking into account the abilities of the women to comprehend this information (Ahmed et al., 2016).

Theme 4 – strained relationships with prison staff.

This final analytical theme describes women’s views about their relationships with prison staff and the impact of these relationships on their perceptions of prison-based mental health care.

Descriptions of interactions reflected poor relationships between the women and those providing care. Relationships were described as “anti-therapeutic” in the context of prescribing medication (Bowen et al., 2009). Women reported that requests to have medications adjusted were generally ignored, resulting in strained relationships. Similarly, women reported that clinicians “did not care” about their issues, and when endeavouring to access the health care, they felt they were “sloughed off” and were “dissatisfied” with responses received from prison staff (Ahmed et al., 2016). Women perceived that relationship difficulties were a precipitating factor to self-harming behaviours and that “being treated better by prison staff” may have prevented these acts (Marzano et al., 2011). Staff were described as “cold” and “desensitised” (Kenning et al., 2010), and although women acknowledged that prison staff work in difficult environments, they also described prison health-care staff as “unqualified”, “unprofessional” and “rejects”, reflecting the degree to which relationships were strained (Plugge et al., 2008).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to synthesise qualitative literature that reports the experiences of women in the context of prison-based mental health care. The findings of this review illustrate the lack of research conducted in this area. Although the seven included studies crossed a 10-year time span and did not elicit in-depth narratives from the women, the findings do provide some insights.

Women in prison are more likely to participate in mental health treatment programmes than their male counterparts (Crittenden and Koons-Witt, 2017). However, findings from this review suggest they are less likely to be offered or have access to treatment programmes. This review highlights the number of challenges women experienced accessing quality services and mental health interventions in a timely and co-ordinated manner, which parallels those seen by women with a history of incarceration in a community context (Mongelli et al., 2020). Bartlett and Hollins (2018) assert women’s criminal behaviours should be seen in the context of trauma and vulnerabilities and that prison should be a truly rehabilitative process where quality mental health care can be provided. This review reveals that women are disempowered from managing their mental health, which may impact their ability to manage their mental and physical health when released from prison. This raises an important question: how can this be considered rehabilitative? Recovery is a multi-definitional concept which, at its core, speaks to individuals developing new meaning and purpose in their lives (Anthony, 1993) and provides a framework for service delivery. Leamy et al. (2011) identified five recovery themes essential for recovery to occur; these include connectedness, hope, identity, meaningful role and empowerment. Therefore, it is essential that women are empowered to manage their own mental health whilst in prison so that they can contribute to their own personal recovery and rehabilitation. This can be supported by strengths and skills-building activities and also by increasing self-esteem and self-efficacy (Leamy et al., 2011).

As a direct result of being in prison, an individual loses some of their fundamental human rights, particularly the right to liberty (United Nations, 1948). However, not all human rights are lost, and this is particularly relevant in respect of the right to privacy. Confidentiality is one of the core ethical principles underpinning health care (Beauchamp and Childress, 2013), irrespective of the context of service provision. Although the findings demonstrate how prison can provide an opportunity to access specialist mental health services, which can have a positive impact on mental well-being (Durcan and Zwemstra, 2014), the review also highlights that women’s applications for health care access were read by others and private information was discussed in corridors and at hatches. This eroded women’s right to privacy and resulted in a reluctance to seek help. Having access to quality mental health services is essential for maintaining mental well-being and is considered a fundamental human right by the World Health Organisation (2017).

Considering prisoners are a vulnerable population, it is of great concern that interpersonal difficulties with prison staff were cited by participants in five of the seven included studies (Plugge et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2009; Kenning et al., 2010; Marzano et al., 2011; Ahmed et al., 2016). Women described staff as unresponsive to their needs, which led to a deterioration in women’s mental health and the creation of a cycle of silence. When access to mental health care was refused or interventions not provided, women’s self-efficacy was diminished; subsequently, they chose not to seek further help or question discrepancies with medication dosages (Plugge et al., 2008; Bowen et al., 2009). Consequently, this further exacerbated their mental health problems and led to strained relationships with prison staff. There appear to be differences between women’s experiences of prison staff, as highlighted by this review’s findings, compared with women’s experiences of forensic-setting staff. Women reported they felt validated, humanised and understood in a forensic setting (Ratcliffe and Stenfert Kroese, 2021), which may suggest that the “for treatment” focus of a forensic setting is more acceptable to women than the “as punishment” focus of the prison. There is no doubt that prison staff work in busy environments, and parallels can be drawn between staff working in acute mental health services where burnout and compassion fatigue can occur as a result of under-resourced working environments, excessive workload and a lack of opportunity (Short et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2018). However, irrespective of these challenges, prison staff need to consider confidentiality as a norm rather than an exception.

Those working in a prison environment are ideally placed to advocate for prompt access to mental health services and the development of policies and systems that ensure quality mental health service provision (Irish Prison Service, 2019b; Scottish Prison Service, 2021). Mental health education for prison staff may help to enhance their understanding of how mental health problems manifest and specific vulnerabilities. It may also enable a more compassionate and respectful approach to service delivery (Irish Prison Service, 2020). Education may also enhance relationships between women in prison and prison staff, with better mental health outcomes for the women and improved working environments for the staff.

Poverty and inequality are common among prisoners and contribute to mental ill-health and, whilst a link between mental health and criminality has been contested (Halle et al., 2020), this combination results in the marginalisation of those impacted (Webster and Qasim, 2018). Marginalised women experience poorer mental health outcomes (Department of Justice and Equality, 2017) and, as the majority of the studies located did not elicit in-depth data on women’s experiences of prison-based mental health care, this also suggests that women in prison are not only marginalised by society, but also by the research community. Roberts (2000) posits that narratives add value to what is known and understood about the lived experience. Hence, there is a clear need for further qualitative research in this context, both to inform policy and service provision and to let the voices of women in prison be heard.

Limitations

This review represented the experiences of 255 women in prison from various backgrounds and geographic locations, yet it found similarities in their experiences in prison and their concerns related to prison-based mental health care. However, the review needs to be read in the context of the following limitations. There was a significant lack of qualitative studies conducted on this topic that has impacted not only the findings of the review, but also the recommendations for policy and practice. Given the lack of diversity represented in the combined population of participants and the small study sample sizes, the transferability of the findings to all women in prison is not possible. Another issue that needs to be acknowledged is that all the studies were conducted in high-income countries, and consequently, the narrative experiences may not be reflective of the prison experiences of women in low-income countries or indeed of the various cultural contexts associated with prison systems internationally. As no date limiters were set, dated research has been included. Subsequently, the review team was unable to provide commentary on the contemporary position of women in prison, as their experiences may have been shaped by any service reform or policy change that has occurred in the intervening years. Although no geographical or language limiters were set, the fact that only studies published in the English language and from high-income countries were located has potentially introduced a bias. As the review was designed to include all relevant research, the quality appraisal undertaken was not to exclude studies. Thus, studies that had lower ratings on quality were included. Finally, the findings may have been shaped by the review team’s experiences as practitioners and researchers in mental health, and therefore, what was deemed relevant may be a result of professional training, standards and perspective.

Future research would benefit from further qualitative studies on diverse populations that focus exclusively on women’s experiences of prison-based mental health care. It would be beneficial for future research to consider participant status as women’s experiences may be shaped according to them being sentenced or on remand. Future research should also provide more contextual information on the nature of the mental health services available to women.

Conclusion

This systematic review has highlighted an urgent need for the international implementation of gender-specific mental health care in prisons as well as a need for further studies that explore the experiences of women using mental health services in prison. Despite having been found guilty of a crime punishable by a custodial sentence, women often have histories of trauma and vulnerabilities. Therefore, prison should be an experience where those serving time can, if they choose to, develop new ways of navigating their social worlds outside of the sphere of crime and where they can access quality mental health interventions if required. If prison is to be a truly rehabilitative process, women need to encounter staff that embodies the humanistic principles of empathy and unconditional positive regard.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Biographies

Ann-Marie Bright is based at the Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Agnes Higgins is based at School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Annmarie Grealish is based at the Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland and Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery and Palliative Care, King’s College London, London, UK

Contributor Information

Ann-Marie Bright, Email: annmarie.bright@ul.ie.

Agnes Higgins, Email: ahiggins@tcd.ie.

Annmarie Grealish, Email: annmarie.grealish@ul.ie.

References

- Ahmed, R., Angel, C., Martel, R., Pyne, D. and Keenan, L. (2016), “Access to healthcare services during incarceration among female inmates”, International Journal of Prisoner Health, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 204-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J., Maia, A. and Teixeira, F. (2016), “Health conditions prior to imprisonment and the impact of prison on health: views of detained women”, Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 782-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, W. (1993), “Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health system in the 1990’s”, Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 11-23. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020), “Prisoners in Australia”, available at: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/latest-release#data-download (accessed 13 Nov 2021).

- Baillargeon, J., Binswanger, I.A., Penn, J.V., Williams, B.A. and Murray, O.J. (2009), “Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door”, American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 166 No. 1, pp. 103-109, doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi, G., Cassidy, M., Fazel, S., Priebe, S. and Mundt, A. (2018), “Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in prisoners”, Epidemiologic Reviews, Vol. 40 No. 1, pp. 134-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, A. and Hollins, S. (2018), “Challenges and mental health needs of women in prison”, The British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 212 No. 3, pp. 134-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, T. and Childress, J. (2013), Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7th ed., Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, R., Rogers, A. and Shaw, J. (2009), “Medication management and practices in prison for people with mental health problems: a qualitative study”, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caravaca-Sánchez, F., Falcón-Romero, M. and Luna-Maldonado, A. (2014), “Physical attacks in prison, mental illness as an associated risk factor”, Revista Española de Sanidad Penitenciaria, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 84-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, E. (2020), Prisoners in 2019, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, L. (2016), “Counterintuitive findings from a qualitative study of mental health in English women’s prisons”, International Journal of Prisoner Health, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 216-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistics Office (2019), “Prison recidivism 2011 and 2012 cohorts”, available at: www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-prir/prisonrecidivism2011and2012cohorts/ (accessed 7 May 2021).

- Cheng, S.H., Augustin, C., Bethel, A., Gill, D., Anzaroot, S., Brun, J., DeWilde, B., Minnich, R., Garside, R., Masuda, Y., Miller, D.C., Wilki, D., Wongbusarakum, S. and McKinnon, M.C. (2018), “Using machine learning to advance synthesis and use of conservation and environmental evidence”, Conservation Biology, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, C. and Koons-Witt, B. (2017), “Gender and programming: a comparison of programme availability and participation in US prisons”, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, Vol. 61 No. 6, pp. 611-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2020), “Sharing the vision: a mental health policy for everyone”, available at: www.gov.ie/en/publication/2e46f-sharing-the-vision-a-mental-health-policy-for-everyone/ (accessed 19 Jul 2021).

- Department of Justice and Equality (2017), “National strategy for women and girls 2017-2020: creating a better society for all”, Department of Justice & Equality, Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Durcan, G. and Zwemstra, J. (2014), Mental Health in Prison, in Enggist, S., Moller, L., Galea, G. and Udesen, C. (Eds), World Health Organisation, pp. 87-95. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S. and Benning, R. (2009), “Suicides in female prisoners in England and Wales, 1978-2004”, British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 194 No. 2, pp. 183-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S., Hayes, A., Bartellas, K., Clerici, M. and Trestman, R. (2016), “Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes and interventions”, The Lancet Psychiatry, Vol. 3 No. 9, pp. 871-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascón, G. (2020), “Special directive 20-08, sentencing enhancements/allegations”, available at: https://da.lacounty.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/SPECIAL-DIRECTIVE-20-08.pdf (accessed 7 May 2021).

- Givens, A., Moeller, K. and Johnson, T. (2021), “Prison-based interventions for early adults with mental health needs: a systematic review”, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, Vol. 65 No. 5, pp. 613-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, T., Chibnall, J., Antoniak, S., McCormick, B. and Black, D. (2012), “Relative contributions of gender and traumatic life experience to the prediction of mental disorders inn a sample of incarcerated offenders”, Behavioral Sciences & the Law, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 615-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle, C., Tzani-Pepelasi, C., Pylarinou, N. and Fumagalli, A. (2020), “The link between mental health, crime and violence”, New Ideas in Psychology, Vol. 58, pp. 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Prison Service (2019a), “Yearly statistics”, available at: www.irishprisons.ie/information-centre/statistics-information/yearly-statistics/ (accessed 19 Jul 2021).

- Irish Prison Service (2019b), “Information booklet – recruiting prison officers”, available at: www.irishprisons.ie/wp-content/uploads/documents_pdf/Final-Booklet-12.12.19-003.pdf (accessed 23 November 2021).

- Irish Prison Service (2020), “Self-harm in Irish Prisons 2018 – second report from the self-harm assessment and data analysis (SAD) project”, Irish Prison Service, Longford. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Prison Service (2021), “Prison”, available at: www.irishprisons.ie/prison/ (accessed 7 May 2021).

- Jacobs, L. and Giordano, S. (2018), “‘It’s not like therapy’: patient-inmate perspectives on jail psychiatric services”, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, Vol. 45 No. 2, pp. 265-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes, Y., Jordan, M., Wright, S. and Bendelow, G. (2019), “Designing ‘healthy’ prisons for women: incorporating Trauma-Informed care and practice (TICP) into prison planning and design”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 16 No. 20, pp. 3818-3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J., Hall, L., Berzins, K., Baker, J., Melling, K. and Thompson, C. (2018), “Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: a narrative review of trends, causes, implications and recommendations for future interventions”, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 20-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, M. and Zielinski, M. (2018), “Sexual victimisation and mental illness prevalence rates among incarcerated women: a literature review”, Trauma, Violence & Abuse, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 326-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenning, C., Cooper, J., Short, V., Shaw, J., Abel, K. and Chew-Graham, C. (2010), “Prison staff and women prisoner’s views on self-harm; their implications for service delivery and development: a qualitative study”, Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 274-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutiller, C., Williams, J. and Slade, M. (2011), “Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis”, British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 199 No. 6, pp. 445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z. and Porritt, K. (2015), “Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing Meta-aggregation”, International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, L., Hawton, K., Rivlin, A. and Fazel, S. (2011), “Psychosocial influences on prisoner suicide: a case-control study of near-lethal self-harm in women prisoners”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 72 No. 6, pp. 874-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. and Huberman, A. (1984), “Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: toward a shared craft”, Educational Researcher, Vol. 13 No. 5, pp. 20-30. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice (2017), “Statistics on women and the criminal justice system 2017”, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/759772/women-cjs-2017-statistics-infographic.pdf (accessed 19 July 2021).

- Ministry of Justice (2019), “Statistics on women and the criminal justice system 2019”, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/938360/statistics-on-women-and-the-criminal-justice-system-2019.pdf (accessed 19 July 2021).

- Ministry of Justice (2021a), “Prisons in England and Wales”, available at: www.gov.uk/government/collections/prisons-in-england-and-wales (accessed 7 May 2021).

- Ministry of Justice (2021b), “Self-harm in prison custody 2004 to 2020: safety in custody quarterly update to December 2020”, Ministry of Justice, London. [Google Scholar]

- Mongelli, F., Georgakopoulos, P. and Pato, M. (2020), “Challenges and opportunities to meet the mental health needs of underserved and disenfranchised populations in the United States”, FOCUS, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 16-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskett, C. (2013), “Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: a review of the literature”, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, A. (2020), An Evidence Review of Recidivism and Policy Responses, Department of Justice & Equality, Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, S. and Devaney, C. (2016), “Supporting incarcerated mothers in Ireland with their familial relationships; a case for the revival of the social work role”, Probation Journal, Vol. 63 No. 3, pp. 293-309. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffman, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L., Stewart, L., Thomas, J., Tricco, A., Welch, V., Whiting, P. and Moher, D. (2021), “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews”, Systematic Reviews, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 1-36, doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plugge, E., Douglas, N. and Fitzpatrick, R. (2008), “Patients, prisoners, or people? Women prisoners’ experiences of primary care in prison: a qualitative study”, British Journal of General Practice, Vol. 58 No. 554, pp. e1-e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, C., Ciclitira, K. and Marzano, L. (2017), “Mother-infant separations in prison. A systematic attachment-focused review of the academic and grey literature”, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 790-810. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, D., Appleby, L., Piper, M., Webb, R. and Shaw, J. (2010), “Suicide in recently released prisoners: a case control study”, Psychological Medicine, Vol. 40 No. 5, pp. 827-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prison Reform Trust (2021), “Prison: the facts, Bromley briefings summer 2021”, available at: www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Bromley%20Briefings/Summer%202021%20briefing%20web%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 19 July 2021).

- Public Health England (2018), “Gender specific standards to improve health and well-being for women in prison in England”, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/687146/Gender_specific_standards_for_women_in_prison_to_improve_health_and_wellbeing.pdf (accessed 9 August 2021).

- Ratcliffe, J. and Stenfert Kroese, B. (2021), “Female service users’ experiences of secure care in the UK: a synthesis of qualitative research”, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 611-640. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G. (2000), “Narrative and severe mental illness: what place do stories have in an evidence-based world?”, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, Vol. 6 No. 6, pp. 432-441. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Prison Service (2021), “Our vision, mission and values”, available at: www.sps.gov.uk/Careers/WorkingfortheSPS/Our-Vision-Mission-and-Values.aspx (accessed 23 November 2021).

- Short, V., Cooper, J., Shaw, J., Kenning, C., Abel, K. and Chew-Graham, C. (2009), “Custody vs care: attitudes of prison staff to self-harm in women prisoners – a qualitative study”, Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 408-426. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. and Harden, A. (2008), “Methods for the systematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews”, BMC Medical Research Methodology, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 1471-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, N., Myles, H., Karadag, B. and Rogers, G. (2019), “An updated picture of the mental health needs of male and female prisoners in the UK: prevalence, comorbidity and gender differences”, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, Vol. 54 No. 9, pp. 1143-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (1948), “Universal declaration of human rights”, available at: www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed 16 November 2021).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2009), “Women’s health in prison: correcting gender inequity in prison health”, available at: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/76513/E92347.pdf (accessed 1 June 2021).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2012), “United Nations rules for the treatment of women prisoners and non-custodial measures for women offenders with their commentary: the Bangkok rules”, available at: www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/Bangkok_Rules_ENG_22032015.pdf (accessed 1 June 2021).

- Walmsley, R. (2017), World Female Imprisonment List, 4th ed., Institute for Criminal Policy Research, University of London, London. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, C. and Qasim, M. (2018), “The effects of poverty and prison on British Muslim men who offend”, Social Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 10, pp. 1-13. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (2017), “Human rights and health”, available at: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health (accessed 13 November 2021).

- World Health Organisation . (2021), “10 Things to know about women in prison”, available at: www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/prisons-and-health/focus-areas/womens-health/10-things-to-know-about-women-in-prison (accessed 01 June 2021).

- World Prison Brief . (2021), “United Kingdom: England and Wales”, available at: www.prisonstudies.org/country/united-kingdom-england-wales (13 November 2021).

- Yoon, I.A., Slade, K. and Fazel, S. (2017), “Outcomes of psychological therapies for prisoners with mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 85 No. 8, pp. 783-802, doi: 10.1037/ccp0000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z. (2020), “Jail inmates in 2018”, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]