Abstract

EBV episomes are nuclear plasmids that are stably maintained through multiple cell divisions in primate and canine cells (J. L. Yates, N. Warren, and B. Sugden, Nature 313:812–815, 1985). In this report, we describe the construction and characterization of an E1-deleted recombinant adenovirus vector system that delivers an EBV episome to infected cells. This adenovirus-EBV hybrid vector system utilizes Cre-mediated, site-specific recombination to excise an EBV episome from a target recombinant adenovirus genome. We demonstrate that this vector system efficiently delivers the EBV episome and stably transforms a large fraction of infected canine D-17 cells. Using a colony-forming assay, we demonstrate stable transformation of 37% of cells that survive the infection. However, maximal transformation efficiency is achieved at doses of the E1-deleted recombinant adenoviruses that are toxic to the infected cells. Consequently, E1-deleted vector toxicity imposes a limitation on our current vector system.

Recombinant adenovirus vectors can transduce a large proportion of cells in a broad range of tissue types, an attribute that makes adenovirus vectors attractive candidates for gene therapy (18). E1-deleted vectors are recombinant adenoviruses in which the early regions, E1A and E1B, are replaced with nonviral DNA, making them severely defective for replication and viral gene expression (21). Because of their ease of construction and ability to be grown to high titers using the E1A- and E1B-complementing 293 cell line (13), E1-deleted vectors have been extensively studied for gene therapy applications. However, experiments with E1-deleted vectors in vivo and in cell culture have demonstrated that vector transduction results in expression of the transgene only transiently (26, 43, 45, 49). The lack of persistent expression is the major limitation of current E1-deleted vectors, since most gene therapy applications require prolonged expression of the therapeutic gene.

Further investigation into the biology of E1-deleted vector transduction in vivo revealed that low-level expression of viral genes induces an immune response against viral antigens, resulting in the clearance of infected cells (45). Other mechanisms for the loss of expression in vivo have been implicated. Several groups have observed downregulation of the vector promoter in vivo (5, 28) and more recently, one group has reported apoptosis of virally transduced cells in mouse liver (27). In early work introducing an E1-deleted vector into rat liver, we observed that the loss of marker gene expression was paralleled by a loss of vector DNA (39), even in the absence of a significant inflammatory response (38a). Loss of vector DNA occurred at a still greater rate when an E1-deleted vector was introduced into replicating cultured canine D-17 osteosarcoma cells. When these cells were infected with an E1-deleted vector at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) from 1 to 100, vector DNA was undetectable by 12 days postinfection (42a). The mechanism by which vector DNA was lost from rat hepatocytes and cultured D-17 cells is not well understood. Adenovirus introduces a nonintegrating linear double-stranded DNA genome into the nucleus, and it is possible that vector DNA is lost through intracellular degradation. In replicating cells, dilution of nonreplicating vector DNA undoubtedly contributes to this process. Regardless of the mechanism of DNA loss, we hypothesize that improvements in the stability of vector DNA would enhance the persistence of vector expression. Our long-term goal is to create an adenovirus vector system capable of persistent expression for applications toward in vivo and cell culture systems. In this report, we present a strategy to overcome vector DNA instability as a first step towards this long-term objective.

Our approach to improving the stability of adenovirus vector DNA was to develop an adenovirus–Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) hybrid vector that delivers an EBV episome to the nucleus of the infected cell. EBV episomes are nuclear plasmids that contain the EBV latent origin of replication, oriP, and express the EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1). Previous studies demonstrated that EBV episomes are stably maintained through multiple cell divisions in primate and canine cells (47). These plasmids replicate once during S phase and segregate to both daughter cells with approximately 95% efficiency (2, 35, 46). The rationale for this hybrid design is to combine the efficiency of adenovirus infection with the genetic stability of EBV episomes to create a vector capable of long-term expression of a transgene(s) in a high percentage of dividing or nondividing cells. In this report, we describe the construction and characterization of an adenovirus-EBV hybrid vector system that delivers an EBV episome to the infected cell. We demonstrate that this vector system efficiently delivers the EBV episome to infected cells and exhibits long-term expression of the marker gene in a significant fraction of infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

D-17 cells (36) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. 293 cells (13) were obtained from Microbix (Toronto, Canada). Cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed by in vitro ligation of restriction fragments prepared from plasmid digestion or digestion of PCR-generated DNA. Plasmid pACCMVCRE is 9.9 kb, consisting of Ad5 DNA nucleotides (nt) 1 to 454, the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early (IE) promoter-enhancer region, the simian virus 40 (SV40) large-T-antigen nuclear localization sequence (22) fused upstream of the coding region for Cre recombinase from bacteriophage P1 (40), a fragment from SV40 encoding the small-T-antigen intron and early poly(A) site, and Ad5 DNA nt 3334 to 6231 cloned into pUC18. Plasmid pAC876 is 9.4 kb, consisting of Ad5 DNA nt 1 to 454, the CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region, the coding region for puromycin N-acetyl transferase (PAC) (44), a fragment from SV40 encoding the small-T-antigen intron and early poly(A) site, and Ad5 DNA nt 3334 to 6231 cloned into pUC18. Plasmid pAC105 is 14.3 kb, consisting of Ad5 DNA nt 1 to 454, two parallel loxP sites (19) that flank components of an EBV episome, and Ad5 DNA nt 3334 to 6231 cloned into pUC18. The components of the EBV episome in pAC105 are the CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region, the EBV oriP (41), the late SV40 poly(A) site, the coding region for EBV EBNA-1 (47), the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (20), and the coding region for PAC. Plasmid pAC111 is 12.5 kb and identical to pAC105 except that it lacks oriP. The starting vector for all pAC-based plasmids was pACCMVpLpA (10), from which the bacterial plasmid origin and Ad5 sequences were derived. In addition, the CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region and SV40 fragment of pACCMVpLpA were used to construct pACCMVCRE and pAC876. Other plasmids used for these constructions were pBabe Puro (31) for PAC; pLNEPN (1) for EMCV IRES; and pCEP4 (Invitrogen) for oriP, EBNA-1, CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region, and the late SV40 poly(A) site in pAC105 and pAC111. The plasmid pCEP4 is a derivative of p201 originally described by Yates et al. (47). Plasmid pBS555 is 3.2 kb consisting of a 256-bp region from the EBV episome between the CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region and PAC open reading frame (ORF) cloned into pBluescript (Stratagene). Plasmid pBS624 is 3.2 kb and identical to pBS555 except that it contains a 47-bp deletion within the region subcloned from the EBV episome.

Recombinant viruses.

Adβgal was a gift from Robert Gerard (16). AdCRE was constructed by cotransfection of pACCMVCRE with the Ad5 right-end fragment prepared by sucrose gradient purification of the large XbaI fragment from Ad5 dl309 DNA (21). Ad876 was constructed by cotransfection of pAC876 with pJM17 (30). Ad105 and Ad111 were constructed by in vitro ligation of ClaI-digested pAC105 and pAC111 to a DNA fragment encoding Ad5 map units 9.1 to 100 with a deletion from 78.3 to 85.8. The right-end fragment was sucrose gradient purified from ClaI-digested AdELGFP DNA. AdELGFP (details of this recombinant virus will be provided upon request) is an E1-deleted, E3-deleted adenovirus previously constructed by homologous recombination with pBHG10 (7) and contains a ClaI site inserted at Ad5 map unit 9.1. The ligation products were transfected into 293 cells. All transfections (12) were into 293 cells (13) that were overlaid with DMEM, 2% FBS, and 0.7% agarose. Single isolated viral plaques were expanded and screened by restriction digest analysis of viral DNA prepared by low-molecular-weight DNA isolation from infected cells. Confirmed viral clones were plaque purified three times. Viral stocks were prepared by large-scale infection of suspension 293 cells. Virus was purified by CsCl2 step gradient ultracentrifugation followed by CsCl2 linear gradient ultracentrifugation (32). Viral DNA was isolated from purified viral stocks by pronase digestion, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation and was analyzed by digestion with multiple restriction enzymes. Purified viral stocks were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–10% glycerol and stored at −70°C. Viral stock titers were determined by PFU assay on 293 cells.

Infection-CFU assay.

A total of 2.5 × 105 D-17 cells were seeded onto 6-cm-diameter dishes 2 days prior to infection. On the day of infection (day 0), the number of cells per dish (typically 106) was determined by trypsinizing cells off one plate and counting with a hemacytometer. The MOI was defined as the number of PFUs (determined on 293 cells) divided by the number of cells infected. For coinfection experiments, both viruses were applied to the cells at the indicated MOI, making the listed MOI half of the total number of PFU per cell. Infection was performed on day 0 by incubating the cells with virus in 0.5 ml of DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C for 1 h followed by the addition of 5 ml of DMEM with 10% FBS. After 24 h, each infected sample was trypsinized, serially diluted 10−1, 10−2, and 10−3, and plated onto duplicate 10-cm-diameter dishes to make dilution plates containing 1/10, 1/33, 1/(1.0 × 102), 1/(3.3 × 102), 1/(1.0 × 103), 1/(3.3 × 103), and 1/(1.0 × 104) the number of cells from the original infected plate. At 5 days postinfection, one set of dilution plates was placed in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1 μg of puromycin (Sigma)/ml. The other set of plates was maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. Colonies were counted after 3 to 5 weeks of incubation, when colony numbers had plateaued. Plating efficiency was determined from the dilution plate that yielded 200 to 600 colonies in nonselective medium. The raw plating efficiency was calculated as the number of colonies in nonselective medium (multiplied by the appropriate dilution factor) divided by the number of cells initially counted on day 0. The listed plating efficiency of infected cells was expressed as a percentage of that of mock-infected cells (whose plating efficiency was defined as 100%) by using the following formula: plating efficiency = (raw plating efficiency/raw plating efficiency of mock-infected cells) × 100%. The raw plating efficiency of mock-infected cells ranged from 50 to 80%. The number of puromycin-resistant colonies in selective medium was counted from the same dilution that was used to determine plating efficiency. The relative transformation efficiency was calculated as the number of puromycin-resistant colonies divided by the number of colonies in nonselective medium.

Isolation of low-molecular-weight DNA.

A modified Hirt DNA (17) isolation procedure was used to isolate low-molecular-weight DNA. First, 106 cells were resuspended in 1 ml of a mixture of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, and 1 mg of pronase/ml and incubated at 37°C for 2 h followed by the addition of 0.25 ml of 5 M NaCl and incubation overnight at 4°C. The precipitant was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was phenol-chloroform extracted; ethanol precipitated; resuspended in a mixture of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 25 μg of DNase-free RNase (Boehringer Mannheim)/ml; and incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

Isolation of total cellular DNA.

Total cellular DNA was isolated with a Blood and Tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen). Final DNA concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

CsCl2-ethidium bromide equilibrium density centrifugation.

Fifty micrograms of total cellular DNA and 20 μg of isolated plasmid, pGEM-luc (Promega), were dissolved in 12 ml of a mixture of 1.55 g of CsCl2/ml, 0.33 mg of ethidium bromide/ml, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 10 mM EDTA and centrifuged at 26,000 rpm at 20°C for 5 days in an SW40 rotor. After centrifugation, two bands separated by ∼1 cm were visible upon illumination with long-wavelength UV light. The top band was collected first by extraction with an 18-gauge needle and syringe inserted into the tube just below the band. The bottom band was collected by the same method. The collected bands were dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA and concentrated by ethanol precipitation. Final DNA concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

Quantitative PCR.

We designed a competitive PCR assay based on that described by Piatak et al. (33). PCR primers (oligonucleotides 236 and 237) were designed to amplify a target template on the EBV episome between the CMV-IE promoter-enhancer region and PAC ORF. PCR amplification of the target template yields a 256-bp product. The competitor template, pBS624, contains the target template sequences with a 47-bp deletion and yields a 209-bp product following PCR amplification. Samples used for quantitative PCR were 10 ng of total cellular DNA, 10 ng of CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient upper band (linear) DNA, or 4 ng of CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient bottom band (closed circular) DNA. DNA samples were digested with EcoRV and HindIII prior to use as PCR templates. The sample template was added to a series of replicate PCRs that contained 0, 10, 30, 1.0 × 102, 3.0 × 102, 1.0 × 103, 3.0 × 103, 1.0 × 104, 3.0 × 104, and 1.0 × 105 copies of linearized competitor template pBS624. Reactions were carried out in 100 μl of 1× Gene Amp II buffer (Perkin-Elmer), 2.75 mM MgCl2, 250 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1 μM oligonucleotide 236, 1 μM oligonucleotide 237, and 2.5 units of Amplitaq Gold (Perkin-Elmer). PCR amplification was performed in a thermocycler (PTC-100; MJ Research, Inc.) using a program of 9 min at 95°C followed by 42 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, visualized by UV illumination, and recorded on instant film (Polaroid), and the equivalence point for target and competitor product was determined by visual inspection of the film. Control reactions with the target sequence in pBS555 demonstrated the ability of the assay to accurately quantitate 10 to 1.0 × 107 copies per reaction.

RESULTS

Construction of recombinant adenovirus vectors.

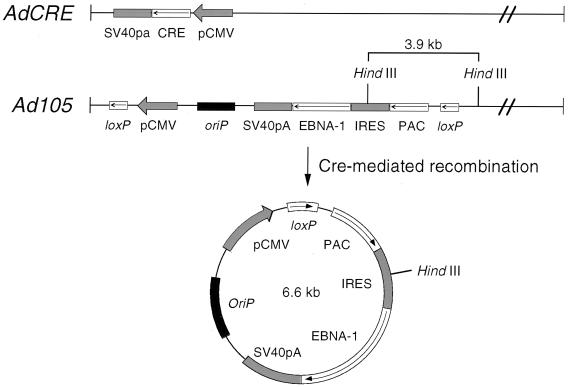

Figure 1 outlines the strategy of our approach for using adenovirus vectors to introduce an EBV episome into the nuclei of infected cells. The strategy involves two adenovirus recombinants. One, called the “target vector,” contains the DNA to be circularized into an EBV episome between two parallel loxP sites. The second recombinant adenovirus expresses the Cre-site-specific recombinase from bacteriophage P1 (6). In cells coinfected with the two recombinants, in vivo Cre-mediated recombination between the two loxP sites in the target vector generates a circular DNA molecule (Fig. 1). For target vector Ad105, the generated circular DNA contains the EBV latent origin of replication, oriP, and an expression cassette for PAC (which inactivates the antibiotic puromycin) and EBNA-1, the single EBV protein required for replication of a plasmid containing oriP (47). EBNA-1 is expressed from the same mRNA that encodes PAC by initiation from an IRES from EMCV (20).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the left end of AdCRE and Ad105 recombinant adenovirus DNA. Cre recombinase expressed from AdCRE catalyzes site-specific recombination between two parallel loxP sites in the target vector to generate DNA circles.

Ad105 (Fig. 1) and the Cre-expressing vector, AdCRE, were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. As a control for these studies, we also constructed Ad111 as a target vector that gives rise to a circular DNA identical to that generated from Ad105, except that it lacks oriP.

The design of the target vector takes advantage of the Cre-mediated recombination event to induce expression of the marker gene and EBNA-1. Prior to the recombination event, the CMV-IE promoter is oriented away from the components of the EBV episome. Following Cre-mediated recombination, the CMV-IE promoter is placed directly upstream of the bicistronic message encoding PAC and EBNA-1. After recombination, the initiating AUG of the PAC ORF is 145 bases downstream from the transcription start site in the CMV-IE promoter. A favorable consequence of the coordination of excision and induction of expression is that PAC is expressed only when present on the excised EBV episome. This feature simplifies the identification of cells harboring the EBV episome using puromycin selection because antibiotic resistance is expressed only from the EBV episome and not from the unrecombined vector. A second advantage of this strategy is that EBNA-1 is not expressed until Cre-mediated recombination occurs, a provision we found necessary to allow propagation of target viruses containing both oriP and the EBNA-1 coding region. Repeated attempts to generate oriP-containing viruses that constitutively expressed EBNA-1 resulted in recovery of recombinant viruses that suffered deletions in oriP or the EBNA-1 expression cassette.

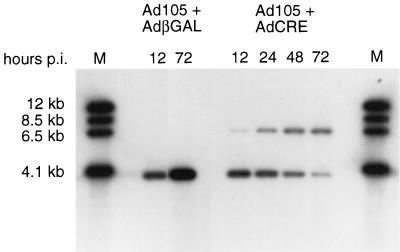

We confirmed that coinfection of Ad105 with AdCRE results in delivery of the EBV episome through site-specific recombination of the target vector in the infected cell. The canine osteosarcoma line, D-17, was coinfected with Ad105 and AdCRE, and low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated at various times postinfection. The DNA was digested with HindIII and analyzed by Southern blot analysis using a PAC DNA fragment as probe. The schematic map illustrates the recombination event and expected restriction digest fragments (Fig. 1).

Samples from cells coinfected with Ad105 and AdCRE contained a 6.6-kb band that hybridized to the PAC probe, indicative of the excised EBV episome, and a 3.9-kb band that represents unrecombined Ad105 DNA (Fig. 2). As a control, cells were coinfected with Ad105 and Adβgal, a recombinant similar to AdCRE but which expresses Escherichia coli β-galactosidase rather than Cre (16). Samples from cells coinfected with Ad105 and Adβgal contained only the 3.9-kb band, demonstrating the absence of spontaneous recombination of loxP sites. The 6.6-kb band appeared in AdCRE coinfected samples as early as 12 h postinfection, and the ratio of the recombined to nonrecombined vector increased over time. Using phosphorimager analysis to compare the intensity of the 6.6-kb band with that of the 3.9-kb band, we determined that 75% of the vector was recombined by 72 h postinfection. Similar recombination efficiency was observed in cells coinfected with Ad111 and AdCRE (data not shown). These results demonstrate efficient delivery of the EBV episome to cultured cells.

FIG. 2.

Cre-mediated recombination in vivo. D-17 cells were coinfected with either Ad105 and Adβgal or Ad105 and AdCRE at an MOI of 10 for each virus. Low-molecular-weight DNA from 2.5 × 105 infected cells was digested with HindIII and analyzed by Southern blotting using PAC DNA as probe. The Ad105 + Adβgal 72-h postinfection (p.i.) lane was exposed for two-thirds as long as other lanes. M, molecular weight markers of DNA fragments that hybridized to the probe.

Stable transformation from adenovirus-EBV hybrid vectors.

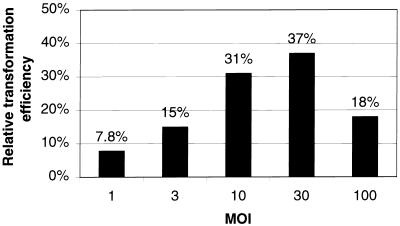

We assayed the ability of the adenovirus-EBV hybrid vector to stably transform D-17 cells. D-17 cells were chosen because they support EBV episome function (47) and are nonpermissive for production of infectious virus that would otherwise interfere with assays for episomal maintenance. We developed a CFU assay of infected cells to determine the relative transformation efficiency, defined as the fraction of stably transformed cells over the number of cells that survived the infection. After infection, cells were serially diluted and plated in puromycin-containing medium to identify cells that expressed PAC. The formation of a visible colony under selective conditions requires the cell to replicate and segregate the PAC expression cassette to progeny cells. Serially diluted infected cells were also plated under nonselective conditions to determine the plating efficiency of infected cells. A specific dilution that yielded hundreds of colonies in nonselective medium was noted, and from this dilution the relative transformation efficiency was calculated by dividing the number of puromycin-resistant colonies by the number of colonies formed in nonselective medium.

Results from a typical experiment with AdCRE and Ad105 coinfected cells demonstrate that the adenovirus-EBV hybrid vector system can stably transform cells with an efficiency previously unrealized from adenovirus-based vectors (Fig. 3). At an MOI of 30, 37% of the colony-forming cells were stably transformed to puromycin resistance. As a comparison, coinfection with AdCRE and Ad876, an E1-deleted vector that expresses PAC from the CMV-IE promoter, yielded only rare stable transformants (1 out of ∼250 colony-forming cells or ∼0.3%) at MOIs ranging from 1 to 100. Thus, the adenovirus-EBV vector stably transforms cells with 100-fold greater efficiency than a standard E1-deleted vector. Efficient stable transformation from AdCRE and Ad105 coinfection was not limited to high MOI, and experiments using MOIs of 10 and 3 yielded 31% and 15% relative transformation efficiencies, respectively. Therefore, higher MOI enhances the relative transformation efficiency, but elevated viral dosage is not required to achieve stable transformation. Control experiments using Adβgal and Ad105 coinfection did not yield any puromycin-resistant colonies from greater than 106 infected cells. Similarly, coinfection of the oriP-negative control virus, Ad111, with AdCRE also failed to produce any stable transformants from greater than 106 infected cells. These experiments demonstrate the requirement for excision of an oriP-containing plasmid and suggest that delivery of the EBV episome is solely responsible for the high degree of stable transformation from the adenovirus-EBV vector system.

FIG. 3.

Relative transformation efficiency by the adenovirus-EBV vector system.

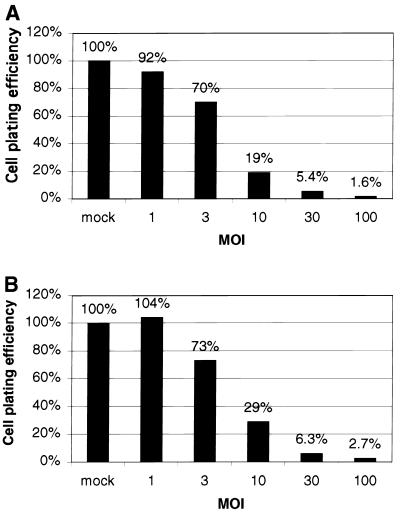

However, countering the apparent success of this efficient strategy for introducing EBV episomes into cells, we observed significant vector-induced cytotoxicity. Coinfection of cells with Ad105 and AdCRE resulted in a significant reduction in the plating efficiency of cells infected at an MOI of 30 compared to mock-infected cells (Fig. 4A). Similar levels of cell death were observed in coinfections with Ad876 and AdCRE (Fig. 4B) as well as infections with other recombinant adenoviruses with deletions of E1A and E1B (data not shown), demonstrating that toxicity is a function of E1-deleted vectors, and consequently was not specific to our vector system. This toxicity of E1-deleted vectors limits the use of high MOI to enhance the efficiency of stable transformation. For example, raising the MOI of Ad105 and AdCRE from 3 to 10 increased the relative transformation efficiency from 15 to 31% at the expense of reducing the plating efficiency from 70 to 19%. Thus, increasing the MOI yields higher transformation efficiency with the tradeoff of decreased cell viability.

FIG. 4.

Plating efficiency of D-17 cells coinfected with Ad105 and AdCRE (A) or Ad876 and AdCRE (B). Plating efficiencies of infected cells were expressed as a percentage of that of mock-infected cells.

DNA analysis of stably transformed cells.

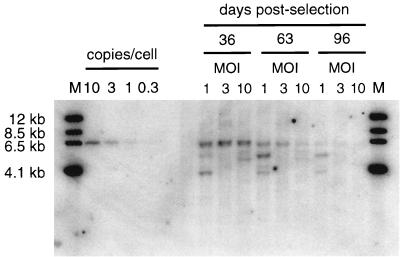

Puromycin-resistant clones obtained from coinfection with Ad105 and AdCRE maintained expression of the drug resistance marker for months during continuous passage in selective medium. To confirm the presence of the EBV episome in stably transformed cells, we pooled puromycin-resistant clones and used a modified Hirt DNA (17) isolation procedure to prepare low-molecular-weight DNA for Southern blot analysis at various time intervals of growth in selective medium. A 6.6-kb band indicative of the EBV episome (Fig. 1) was apparent in DNA isolated from cells maintained by continuous passage in puromycin-containing medium for 96 days (Fig. 5). In addition to the 6.6-kb band, some samples contained smaller HindIII fragments that hybridized to the probe. The nature of the alternate bands has not been determined; however, we postulate that they represent deleted forms of the EBV episome that hybridized to the probe. We used phosphorimager analysis to quantitate the copy number per cell of the EBV episome by comparing the intensity of the 6.6-kb band to those of known standards. At day 36, the EBV episome was present at approximately 10 copies per cell in cells initially infected at an MOI of 1, 3, and 10, consistent with previous reports of EBV episome copy number after introduction of EBV plasmids by transfection (35, 47). As the cells were passaged in selective medium, the amount of EBV episome present in low-molecular-weight DNA samples diminished with time. By day 96, the EBV episome was barely detectable in the MOI-1 and -3 samples and undetectable in the MOI-10 sample. Since the cells maintained puromycin resistance, the most likely hypothesis to explain the disappearance of the EBV episome from low-molecular-weight DNA is integration of the drug resistance marker into chromosomal DNA.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of low-molecular-weight DNA from pooled stable transformants. Approximately 50 individual puromycin-resistant colonies were combined to form pools of stable transformants from cells infected at a multiplicity of 1, 3, or 10. Cells were continuously passaged in puromycin-containing media and harvested for DNA analysis at the indicated time intervals. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from 106 cells, digested with HindIII, fractionated by electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane by Southern blotting. The membrane was probed with a 32P-labeled PAC DNA fragment and exposed to a phosphorimager screen for 2 days. Copy number per cell lanes were loaded with known amounts of a PAC containing DNA fragment.

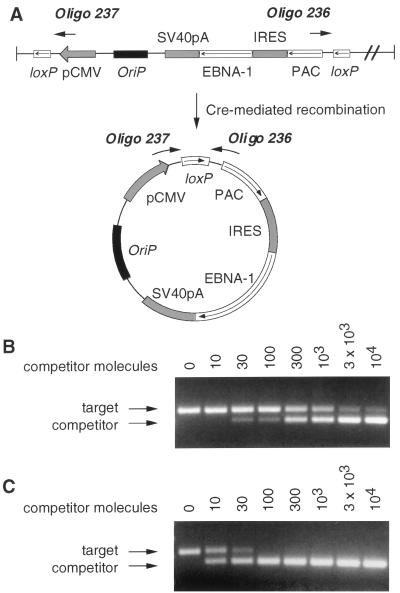

To determine whether the PAC expression cassette integrated into chromosomal DNA in late-passage cells, we quantitated the amount of PAC DNA maintained episomally versus the amount integrated into chromosomal DNA. Total cellular DNA was isolated from puromycin-resistant cells and fractionated by CsCl2-ethidium bromide equilibrium density centrifugation to separate closed circular DNA from linear and open circular DNA (34). We collected the closed circular fraction, which contained the EBV episome, and the linear and open circular fraction, which contained chromosomal DNA and the small fraction of EBV episome that suffered a single phosphodiester bond break during isolation (nicked circles). To determine the amount of PAC DNA in fractionated samples, we used a quantitative competitive PCR assay (33) that amplified a template specific to expressed PAC (Fig. 6A). The target template chosen for PCR amplification was the junction between the CMV-IE promoter and PAC ORF generated only after Cre-mediated excision and circularization of the EBV episome. This template is specific for expressed PAC, and the PCR primers designed to amplify this region do not give rise to a product from nonrecombined Ad105 viral DNA.

FIG. 6.

Quantitative competitive PCR. Oligonucleotide primers 236 and 237 were designed to amplify a target template that consists of the junction between the CMV-IE promoter and PAC ORF present only on the EBV episome (A). Quantitation of the target template was achieved by performing a series of replicate PCRs containing a fixed amount of sample and increasing amounts of a competitor template nearly identical to the target except that it contains a 47-bp deletion. PCR amplification of the target template gives rise to a 256-bp product, whereas the competitor yields a 209-bp product. The reaction products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination to determine the product equivalence point. Shown is the quantitation of 300 target templates in the linear fraction (B) and 10 target templates in the closed circular fraction (C) of CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient-fractionated DNA from MOI-10-infected cells at day 96.

We performed quantitative PCR analysis on fractionated and total cellular DNA from the same pooled clones used for Southern blot analysis of low-molecular-weight DNA (Fig. 5). The amplification of the specific PCR product from linear DNA fractions indicated that the PAC drug resistance marker had integrated into chromosomal DNA (Fig. 6B and Table 1). Southern blot analysis on linear-fraction DNA samples digested with restriction enzymes that precisely flank the PAC ORF confirmed the presence of the full-length ORF (data not shown). The PAC template was also detected in the closed circular DNA fractions for 96 days (Fig. 6C), and the copy number diminished over time (Table 1), consistent with the loss of EBV episome from low-molecular-weight DNA samples. Analysis of individual clones of transformed cells gave similar results indicating PAC DNA integration into chromosomal DNA (Table 2) and a decrease in episomal PAC DNA after multiple cell doublings (clones 18.5.4, 18.5.6, and 19.3.9).

TABLE 1.

Quantitation of integrated and episomal PAC DNA from pooled stable transformantsa

| Sample | Days in selection | PAC DNA templates/10 ng of total cell DNA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfractionated | Linear fraction | Closed-circular fraction | ||

| MOI 1 pool | 36 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| MOI 1 pool | 63 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| MOI 1 pool | 96 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| MOI 3 pool | 36 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| MOI 3 pool | 63 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| MOI 3 pool | 96 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| MOI 10 pool | 36 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| MOI 10 pool | 63 | 300 | 300 | 100 |

| MOI 10 pool | 96 | 300 | 300 | 10 |

Total cellular DNA was fractionated by CsCl2-ethidium bromide equilibrium density centrifugation, and the number of PAC DNA templates in 10 ng of total cellular DNA, 10 ng of CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient upper band (linear) DNA, or the closed circular DNA isolated from an equivalent number of cells was determined by quantitative PCR (Fig. 6B and C). Note that quantitation is estimated to within factors of 3 as shown in Fig. 6B and C.

TABLE 2.

Quantitation of integrated and episomal PAC DNA from individual stable transformantsa

| Sample | Days in selection | PAC DNA templates/10 ng of total cell DNA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonfractionated | Linear fraction | Closed-circular fraction | ||

| MOI 3 | ||||

| Clone 17.6.1 | 74 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 300 |

| Clone 17.6.2 | 74 | 300 | 300 | 30 |

| Clone 17.6.3 | 78 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| MOI 10 | ||||

| Clone 18.5.3 | 93 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 10 |

| Clone 18.5.4 | 54 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 100 |

| Clone 18.5.4 | 93 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 30 |

| Clone 18.5.5 | 61 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 300 |

| Clone 18.5.6 | 61 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 30 |

| Clone 18.5.6 | 93 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 10 |

| MOI 30 | ||||

| Clone 19.3.6 | 64 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 10 |

| Clone 19.3.9 | 61 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 100 |

| Clone 19.3.9 | 93 | 300 | 300 | 10 |

| Clone 19.3.10 | 61 | 300 | 300 | 30 |

Single puromycin-resistant colonies were expanded in puromycin-containing media. Total cellular DNA was fractionated by CsCl2-ethidium bromide equilibrium density centrifugation, and the number of PAC DNA templates in 10 ng of total cellular DNA, 10 ng of CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient upper band (linear) DNA, or the closed circular DNA isolated from an equivalent number of cells was determined by quantitative PCR.

In our quantitative PCR assay of pooled clones, we detected 300 copies of PAC DNA in the linear and closed circular DNA fractions prepared from 10 ng of total cellular DNA after 36 days of selection, comparable to ∼1 copy per cell of integrated and episomal PAC DNA. However, Southern blot analysis of low-molecular-weight DNA samples from the same cells indicated approximately 10 copies of the episome per cell. This discrepancy resulted because low-molecular-weight DNA isolation consistently yielded more EBV episome per cell than did total cellular DNA isolation from the same sample of cells. Another group also noted a similar difference in EBV episome yield between these two isolation methods (42). Consequently, our PCR assay likely underestimated the amount of episomal PAC DNA.

DISCUSSION

We designed and characterized an adenovirus-EBV hybrid vector system that combines the potential of recombinant adenoviruses to transduce a large proportion of cells in a broad range of tissues (18) with the ability of EBV episomes to be stably maintained in replicating cells (47). Our vector system is comprised of two recombinant adenoviruses. The first recombinant transiently expresses the Cre-site-specific recombinase from bacteriophage P1, and the second contains the DNA to be stably maintained in transduced cells between two parallel loxP sites. Cre recombinase expressed from the first vector catalyzes recombination between the loxP sites in the second vector, causing excision and circularization of the intervening DNA. The excised, circularized DNA is engineered to contain elements required for stable maintenance of an EBV plasmid, the EBV latent origin of replication, oriP (41), and an expression cassette for EBV EBNA-1 (47), as well as a gene to be stably expressed in transduced cells.

An essential aspect of our design was that the promoter-enhancer used to express EBNA-1 in the circular DNA molecule generated by Cre recombination did not express EBNA-1 from the target adenovirus vector. The promoter-enhancer was placed upstream of the EBNA-1-encoding transcript only following Cre-mediated excision and circularization (Fig. 1). Multiple attempts to construct adenovirus recombinants containing both an EBNA-1 expression cassette and EBV oriP were unsuccessful. Recovered recombinants invariably suffered deletions in either the EBNA-1 expression cassette or oriP. Although we have not proven the point rigorously, we believe that binding of EBNA-1 to oriP in a recombinant adenovirus interferes with adenovirus DNA replication. The strategy we devised (Fig. 1) allows us to propagate the target vector containing both oriP and the EBNA-1 coding region under conditions where EBNA-1 is not expressed.

The adenovirus-EBV vector strategy resulted in the stable transformation of 37% of surviving D-17 cells to puromycin resistance following coinfection of AdCRE and the Ad105 target vector (Fig. 3). Circular EBV plasmids were maintained in descendents of the initially transduced cells for 14 weeks, ∼110 cell generations (Tables 1 and 2). However, the puromycin resistance expression cassette was also found integrated into cellular chromosomal DNA (Tables 1 and 2). To the best of our knowledge, integration of EBV plasmids maintained through antibiotic selection has not been previously reported. However, previous studies have not included thorough assays for integration into chromosomal DNA, whereas we utilized a highly sensitive PCR assay to detect drug resistance marker DNA in CsCl2-ethidium bromide gradient-purified genomic DNA from stably transformed cells. Furthermore, the majority of studies on EBV plasmids have been performed in human cell lines, many of which constitutively express EBNA-1 (15, 29, 35, 47). Thus far, there has been only one report on EBV episome maintenance in canine cells, and this study did not include investigation of possible integration events (47). It is possible that integration occurs more frequently in canine or D-17 cells versus primate or other cell lines more commonly used to study EBV plasmids.

An obvious limitation to the current adenovirus-EBV vector system described here is that a large fraction of cells were killed by infection at a multiplicity of 30, the MOI required to achieve stable transformation of 37% of the surviving cells. Under these conditions, 95% of infected cells failed to generate colonies. This is likely due to the long-term (over the first week postinfection) cytotoxicity imparted to infected cells by E1-deleted adenovirus vectors. Toxicity from E1-deleted vectors has been reported in experiments in vivo and in cell culture. In mouse liver, E1-deleted vector transduction results in apoptosis of hepatocytes, and cell death can be inhibited by exogenous expression of Bcl-2 (27). Infection of cells in vitro results in slowing of the cellular growth rate, and infected cells have a higher fraction of apoptotic cells and a lower proportion of cells in S phase compared to uninfected cells (43). E1-deleted vector toxicity is most likely caused by low levels of E1A-independent transcription from viral promoters, resulting in expression of toxic viral gene products. Genetic inactivation of the virus through exposure to UV irradiation abrogates vector-induced toxicity (43). Several groups have engineered recombinant adenoviruses with reduced toxicity by introducing further defects in viral genes in addition to deletion of E1A and E1B (3, 4, 8, 11, 23, 37, 48).

To reduce the toxicity of our vector system, we have begun to reconstruct our episomal system in a “gutless” adenovirus vector. Gutless adenoviruses are completely deleted of all viral genes, retaining only the cis-acting inverted terminal repeat origins of DNA replication and adenovirus packaging sequence (9, 14, 38). Thus, gutless vectors have the capacity to accept nearly 36 kb of foreign DNA or nearly the length of the entire wild-type adenovirus genome. Such vectors must be propagated in the presence of helper virus to provide viral proteins required for DNA replication and production of virions. Because of their complete lack of adenovirus gene expression, gutless vectors impart minimal toxicity to infected cells and are far less immunogenic than E1-deleted vectors (38). Our next generation, “gutless episomal” vector should be minimally immunogenic since it will express only the marker gene and EBNA-1. Masucci and colleagues (24, 25) have shown that EBNA-1 does not elicit a cytotoxic T-cell response, due to the presence of a series of glycine-alanine repeats in EBNA-1. The repeats act in cis to prevent major histocompatibility complex class I presentation by inhibiting antigen processing by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (24, 25). Furthermore, an immune response against vector-transduced cells is even less likely in cases where the marker gene encodes an endogenous gene product. We hypothesize that the gutless episomal vector will be a significant step towards our long-term goal of an adenovirus vector system capable of stably transforming mammalian cells with high efficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bill Sugden for helpful discussions and Carol Eng for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM08042 and Public Health Service grant CA25235.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam M A, Ramesh N, Miller A D, Osborne W R. Internal initiation of translation in retroviral vectors carrying picornavirus 5′ nontranslated regions. J Virol. 1991;65:4985–4990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4985-4990.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams A. Replication of latent Epstein-Barr virus genomes in Raji cells. J Virol. 1987;61:1743–1746. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1743-1746.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amalfitano A, Begy C R, Chamberlain J S. Improved adenovirus packaging cell lines to support the growth of replication-defective gene-delivery vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3352–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armentano D, Sookdeo C C, Hehir K M, Gregory R J, St. George J A, Prince G A, Wadsworth S C, Smith A E. Characterization of an adenovirus gene transfer vector containing an E4 deletion. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1343–1353. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.10-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armentano D, Zabner J, Sacks C, Sookdeo C C, Smith M P, St. George J A, Wadsworth S C, Smith A E, Gregory R J. Effect of the E4 region on the persistence of transgene expression from adenovirus vectors. J Virol. 1997;71:2408–2416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2408-2416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin S, Ziese M, Sternberg N. A novel role for site-specific recombination in maintenance of bacterial replicons. Cell. 1981;25:729–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bett A J, Haddara W, Prevec L, Graham F L. An efficient and flexible system for construction of adenovirus vectors with insertions or deletions in early regions 1 and 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8802–8806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelhardt J F, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson J M. Ablation of E2A in recombinant adenoviruses improves transgene persistence and decreases inflammatory response in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher K J, Choi H, Burda J, Chen S J, Wilson J M. Recombinant adenovirus deleted of all viral genes for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Virology. 1996;217:11–22. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Foix A M, Coats W S, Baque S, Alam T, Gerard R D, Newgard C B. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the muscle glycogen phosphorylase gene into hepatocytes confers altered regulation of glycogen metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25129–25134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorziglia M I, Kadan M J, Yei S, Lim J, Lee G M, Luthra R, Trapnell B C. Elimination of both E1 and E2 from adenovirus vectors further improves prospects for in vivo human gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:4173–4178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4173-4178.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham F L, van der Eb A J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham F L, Smiley J, Russell W C, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy S, Kitamura M, Harris-Stansil T, Dai Y, Phipps M L. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J Virol. 1997;71:1842–1849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1842-1849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauer C A, Getty R R, Tykocinski M L. Epstein-Barr virus episome-based promoter function in human myeloid cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:1989–2003. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.5.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herz J, Gerard R D. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of low density lipoprotein receptor gene acutely accelerates cholesterol clearance in normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2812–2816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hitt M M, Addison C L, Graham F L. Human adenovirus vectors for gene transfer into mammalian cells. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;40:137–206. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoess R H, Abremski K. Interaction of the bacteriophage P1 recombinase Cre with the recombining site loxP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1026–1029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang S K, Davies M V, Kaufman R J, Wimmer E. Initiation of protein synthesis by internal entry of ribosomes into the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA in vivo. J Virol. 1989;63:1651–1660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1651-1660.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones N, Shenk T. Isolation of adenovirus type 5 host range deletion mutants defective for transformation of rat embryo cells. Cell. 1979;17:683–689. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalderon D, Roberts B L, Richardson W D, Smith A E. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell. 1984;39:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krougliak V, Graham F L. Development of cell lines capable of complementing E1, E4, and protein IX defective adenovirus type 5 mutants. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1575–1586. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.12-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levitskaya J, Coram M, Levitsky V, Imreh S, Steigerwald-Mullen P M, Klein G, Kurilla M G, Masucci M G. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1. Nature. 1995;375:685–688. doi: 10.1038/375685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitskaya J, Sharipo A, Leonchiks A, Ciechanover A, Masucci M G. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12616–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Kay M A, Finegold M, Stratford-Perricaudet L D, Woo S L. Assessment of recombinant adenoviral vectors for hepatic gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:403–409. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.4-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieber A, He C-Y, Meuse L, Himeda C, Wilson C, Kay M A. Inhibition of NF-κB activation in combination with Bcl-2 expression allows for persistence of first-generation adenovirus vectors in the mouse liver. J Virol. 1998;72:9267–9277. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9267-9277.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Löser P, Jennings G S, Strauss M, Sandig V. Reactivation of the previously silenced cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter in the mouse liver: involvement of NFκB. J Virol. 1998;72:180–190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.180-190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolskee R F, Kavathas P, Berg P. Epstein-Barr virus shuttle vector for stable episomal replication of cDNA expression libraries in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2837–2847. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGrory W J, Bautista D S, Graham F L. A simple technique for the rescue of early region I mutations into infectious human adenovirus type 5. Virology. 1988;163:614–617. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgenstern J P, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettersson U, Sambrook J. Amount of viral DNA in the genome of cells transformed by adenovirus type 2. J Mol Biol. 1973;73:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piatak M, Jr, Luk K C, Williams B, Lifson J D. Quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction for accurate quantitation of HIV DNA and RNA species. BioTechniques. 1993;14:70–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff R, Bauer W, Vinograd J. A dye-buoyant-density method for the detection and isolation of closed circular duplex DNA: the closed circular DNA in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57:1514–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.5.1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reisman D, Yates J, Sugden B. A putative origin of replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus is composed of two cis-acting components. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1822–1832. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riggs J L, McAllister R M, Lennette E H. Immunofluorescent studies of RD-114 virus replication in cell culture. J Gen Virol. 1974;25:21–29. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-25-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaack J, Guo X, Ho W Y, Karlok M, Chen C, Ornelles D. Adenovirus type 5 precursor terminal protein-expressing 293 and HeLa cell lines. J Virol. 1995;69:4079–4085. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4079-4085.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiedner G, Morral N, Parks R J, Wu Y, Koopmans S C, Langston C, Graham F L, Beaudet A L, Kochanek S. Genomic DNA transfer with a high-capacity adenovirus vector results in improved in vivo gene expression and decreased toxicity. Nat Genet. 1998;18:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-180. . (Erratum, 18:298.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.Shaked, A., and A. J. Berk. Unpublished results.

- 39.Shaked A, Csete M E, Drazan K E, Bullington D, Wu L, Busuttil R W, Berk A J. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in the transplant setting. II. Successful expression of transferred cDNA in syngeneic liver grafts. Transplantation. 1994;57:1508–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sternberg N, Sauer B, Hoess R, Abremski K. Bacteriophage P1 cre gene and its regulatory region. Evidence for multiple promoters and for regulation by DNA methylation. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:197–212. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugden B, Marsh K, Yates J. A vector that replicates as a plasmid and can be efficiently selected in B-lymphoblasts transformed by Epstein-Barr virus. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:410–413. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun T Q, Fernstermacher D A, Vos J M. Human artificial episomal chromosomes for cloning large DNA fragments in human cells. Nat Genet. 1994;8:33–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-33. . (Erratum, 8:410.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.Tan, B. T., and A. J. Berk. Unpublished results.

- 43.Teramoto S, Johnson L G, Huang W, Leigh M W, Boucher R C. Effect of adenoviral vector infection on cell proliferation in cultured primary human airway epithelial cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1045–1053. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.8-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vara J, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A, Jimenez A. Cloning and expression of a puromycin N-acetyl transferase gene from Streptomyces alboniger in Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Gene. 1985;33:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Nunes F A, Berencsi K, Furth E E, Gonczol E, Wilson J M. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yates J L, Guan N. Epstein-Barr virus-derived plasmids replicate only once per cell cycle and are not amplified after entry into cells. J Virol. 1991;65:483–488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.483-488.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yates J L, Warren N, Sugden B. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature. 1985;313:812–815. doi: 10.1038/313812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeh P, Dedieu J F, Orsini C, Vigne E, Denefle P, Perricaudet M. Efficient dual transcomplementation of adenovirus E1 and E4 regions from a 293-derived cell line expressing a minimal E4 functional unit. J Virol. 1996;70:559–565. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.559-565.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zabner J, Couture L A, Gregory R J, Graham S M, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer transiently corrects the chloride transport defect in nasal epithelia of patients with cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1993;75:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80063-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]