Abstract

Men's altruism may have evolved, via female choice, as a signal of either their genetic quality or their willingness to allocate resources to offspring. The possibility that men display altruism to signal their genetic quality may be tested by examining women's preference for men's altruism across the stages of the menstrual cycle. Because women can maximize reproductive benefits by mating with men who have “good genes” on high-fertility versus low-fertility days, women should show a heightened preference for male altruism on high-fertility days compared to low-fertility days, and this heightened preference should be more apparent when women evaluate men for short-term sexual relationships than for long-term committed relationships. The possibility that men display altruism to signal their willingness to provision, as opposed to their genetic quality, may be tested by examining women's preference for men's altruism toward different recipients. More specifically, altruistic behavior toward family members may reflect a willingness to provide resources for kin and, hence, willingness to provision, whereas altruistic behavior toward strangers may function as an honest signal of genetic quality. In two samples of young women (TVs = 131 and 481), we found no differences between high- and low-fertility participants in preference for men's altruism, and women preferred men's altruism more in long-term than short-term relationships. The findings suggest that men's altruistic behavior functions as a signal of willingness to provide resources rather than genetic quality.

Keywords: altruism, sexual selection, female choice, mate preference, good genes

Introduction

A number of studies have suggested that altruistic behaviors in men have evolved through female choice (e.g., Farrelly, Lazarus, and Roberts, 2007). On the men's side, it has been shown that men display altruistic behavior in the presence of women, especially when other men (intrasexual competitors) are present. For example, men contribute more to charity and engage in more competition with each other for contribution in a public-goods game in order to impress women (Iredale, Van Vugt, and Dunbar, 2008; Van Vugt and Iredale, 2013). This male display of altruism has also been observed in non-Western cultures like Senegal (Tognetti, Berticat, Raymond, and Faurie, 2012), where men's charitable donations as part of their winnings after a sequential public-goods game increased when in the presence of young women compared to when in the presence of old women. These studies indicate that men try to show their altruism to women, which suggests an influence of female choice on men's altruistic behaviors.

On the women's side, several studies have indicated that women have preferences for altruistic men as mates. For example, women respond significantly more positively than men on an altruism scale when identifying desirable characteristics in mates (Phillips, Barnard, Ferguson, and Reader, 2008). Another study showed that women prefer altruists rather than non-altruists for single dates, whereas men have no such preference (Barclay, 2010).

There are two possible mechanisms by which women's preference for altruism could lead to an increase in women's reproductive fitness. First, altruism in men could be an indicator of their willingness to invest in their offspring. Because men's parental investment has been an important factor in the survival and health of offspring over the course of human evolution, it is crucial that women choose a male partner willing to allocate resources toward their future children (Brase, 2006). Second, altruism in men may be an indicator of the possession of “good genes.” According to the handicap principle (Zahavi, 1975), costly traits are an accurate signal of the phenotypic and genotypic quality of a man and, therefore, likely to be chosen by women. Altruism can be one of those costly signals (Zahavi, 1995).

Given the two possible mechanisms mentioned above, it is noteworthy that women engage in both short-term and long-term mating strategies (Buss and Schmitt, 1993), and the traits they desire in a partner vary according to the strategy they employ (Pillsworth and Haselton, 2006). Even though women could maximize their reproductive benefits by forming a long-term relationship with a man who is both high in genetic quality and highly suitable as a provider, not all men possess both characteristics. Therefore, it is expected that, as a short-term strategy, women demand male genetic traits that guarantee the high adaptive value of offspring. As a long-term strategy, on the other hand, women are predicted to desire the ability and willingness of men to provide for their offspring. Indeed, studies on the mate preferences of women have confirmed these predictions (e.g., Bereczkei, Voros, Gal, and Bernath, 1997; Oda, 2001).

Changes in women's mating strategies are—at least partly—related to their menstrual cycle. On high-fertility days relative to low-fertility days, women can maximize their reproductive benefits by mating with men who have “good genes”; this is expected to be reflected in their mate preferences. In fact, women exhibit menstrual cycle shifts in their mate preferences, as documented in dozens of studies, including a meta-analysis by Gildersleeve, Haselton, and Fales (2014), which analyzed 134 effects from 38 published and 12 unpublished studies that evaluated the plausibility of these shifts. These authors demonstrated that cycle shifts are specific to women's preference for cues of genetic quality such as body masculinity or facial symmetry (but see also Wood, Kerssel, Joshi, and Louie [2014], who failed to find consistent effects regarding the influence of hormonal cycling on women's mate preferences).

Based on these observations, it may be hypothesized that, on the one hand, if the altruistic behavior of men is an indicator of good genes, then women in the high-fertility period would reveal a stronger preference for such men than women in the low-fertility period would. Moreover, this heightened preference for altruism during high versus low fertility is more likely to be identified in short-term rather than long-term relationships. On the other hand, if the altruistic behavior of men is an indicator of provisioning, then it will be more preferred in a long-term rather than a short-term relationship and a cycle shift will not be observed. Of course, these predictions do not necessarily contradict each other. From this viewpoint, Farrelly (2011) investigated women's preferences toward men's altruistic behavior using vignettes of different examples of cooperation (personality, generosity, and heroism) and a self-report scale of altruism to examine women's preferences toward potential mates for different relationship types at different stages of their menstrual cycle. In this study, women's fertility did not have an effect on the preference for altruistic behavior, and altruistic characteristics were considered more important in long-term than in short-term mates. Given the results, Farrelly (2011) concluded that altruism in men is an important factor during mate choice because it is an indicator of provisioning rather than a signal of good genes. However, Farrelly (2011) did not examine preferences for altruistic behaviors toward different recipients.

In studying the evolution of altruism, it is important to distinguish between several types of altruism based on the relationships between the altruists and the recipients. If the two parties are related, the altruistic behavior can be explained by kin selection (Hamilton, 1964), where the altruism aids the genes of the actor. Altruistic behavior between non-kin acquaintances or friends is considered to have evolved based on direct reciprocation, in which the actor of the altruistic behavior is later rewarded by the recipient following repeated encounters between them (Trivers, 1971). Humans also show altruistic behavior toward strangers. Indirect reciprocity and competitive altruism theories propose that the actors benefit in the long-term by “purchasing” increased cooperation from others when they “pay” for altruistic behavior. In this case, the reward is delayed and uncertain. Therefore, altruistic behavior toward a stranger is the most costly among the three types of altruism. This implies the possibility that altruism toward strangers may appeal to women as a trait to aid in the selection of a potential mate. Oda, Shibata, Kiyonari, Takeda, and Matsumoto-Oda (2013) investigated the preferences of each gender for altruistic behaviors performed in daily life by members of the opposite sex toward various recipients using an altruism scale. These authors found that the preference for opposite-sex altruism differs according to the recipient, and relationship type may influence this preference: Altruistic behaviors toward family members are more preferred in long-term rather than short-term relationships, altruistic behaviors toward friends and acquaintances are less preferred in long-term relationships, and there is no difference in the preference for altruistic behaviors toward strangers between short-term and long-term relationships. Although Barclay (2010) reported that opposite-sex altruism is more preferred in long-term relationships, it depended on the recipient of the altruistic behaviors.

Based on these theories and preceding evidence, it is hypothesized that if altruism is preferred because it serves as an indicator of one's willingness to provide for future children, then altruistic behavior toward kin should be more preferred for long-term rather than short-term mates, and women's fertility should not affect their preference. If altruism in men is an indicator of genetic quality, then women in the high-fertility period will consider opposite-sex altruism toward strangers as more important than women in the low-fertility period, and this tendency will be greater in short-term relationships.

Thus, the present study investigated the preferences of women in either the high- or low-fertility period for altruistic behaviors enacted in daily life by the opposite sex toward various recipients. The Self-Report Altruism Scale Distinguished by the Recipient (SRAS-DR), which was developed to evaluate altruism in Japanese undergraduates (Oda, Dai, et al., 2013), was employed to evaluate the altruistic behaviors enacted during daily life and to classify these behaviors according to the recipient (family members, friends and acquaintances, or strangers). If altruistic behavior toward a family member is preferred for long-term rather than short-term mates, then altruism in men will be seen as a signal for provisioning. If women in the high-fertility period evaluate opposite-sex altruism toward strangers as more important than women in the low-fertility period, and this tendency is greater in a short-term relationship, this will support the hypothesis that altruism in men is a signal for genetic quality.

Materials and Methods

Preference survey

First, participants rated the desirability of each of the 21 items on the SRAS-DR (see Table 1) from “1” (not so desirable) to “5” (very desirable) for both a short-term mate (“a partner with whom you have casual sex”; i.e., a partner with whom you have a short-term relationship) and a long-term mate (“a partner whom you marry”; i.e., a partner with whom you have a long-term relationship). Details concerning the development of this instrument and its items are described in the Supplemental Material supplied by Oda, Shibata, et al. (2013). Although a spouse (non-kin) may be regarded as a family member, the SRAS-DR was developed for undergraduates, and most undergraduates in Japan are not married. Therefore, a recipient who is a “family member” can be considered kin, “friends and acquaintances” may be regarded as partners with whom a reciprocal relationship is maintained, and “strangers” can be considered others without this type of relationship. Items were presented randomly. We calculated the total score for each subscale to measure the altruistic behavior desirability score of each recipient (possible range = 7 to 35 for each subscale).

Table 1.

Items of Self-Report Altruism Scale Distinguished by the Recipient (SRAS-DR)

| Items for family members |

| 1. I have supported one of my family members when they were not feeling well. |

| 2. I have helped with housekeeping (e.g., cooking, cleaning, garbage removal). |

| 3. I have helped one of my family members when they were overburdened. |

| 4. I have nursed one of my family members when they were sick. |

| 5. I have helped to retrieve things from high places when a family member needed help. |

| 6. I have made tea for my family members. |

| 7. I have kept in tune with one of my family members when they were in a bad mood. |

|

|

| Items for friends or acquaintances |

| 1. I have listened to the troubles and complaints of a friend/acquaintance. |

| 2. I have accompanied a friend to a place they wanted to go. |

| 3. I have congratulated a friend on their birthday. |

| 4. I have given a friend/ acquaintance sweets and a drink. |

| 5. I have phoned or sent an e-mail to a friend who was depressed. |

| 6. I have helped a friend/acquaintance when they dropped something. |

| 7. I have lent money to a friend. |

|

|

| Items for strangers |

| 1. I have helped a stranger who fell on the road. |

| 2. I have helped a stranger put their luggage on a train or bus rack. |

| 3. I have offered help when a stranger was looking for something. |

| 4. I have helped old people carry their heavy luggage. |

| 5. I have helped pick up a stranger's bicycle when it fell down. |

| 6. I have taught strangers how to use a vending or ticket machine. |

| 7. I have taken care of a stranger or called an ambulance when they were injured or fell ill suddenly. |

Menstrual cycle survey

Following the preference questionnaires, each participant reported on their menstrual cycle. Based on a previous study (Lukaszewski and Roney, 2009), they provided three pieces of information: 1) the first day of last menstrual bleeding, 2) an estimation of the number of days until the beginning of the next menstrual bleeding, and 3) the duration of a typical cycle. If the participant's report was accurate, the number of days from the first day of the last menstrual bleeding (i.e., cycle day) should be equal to the typical cycle length minus the number of days until the beginning of the next cycle. If the participant's typical cycle day was more than 5 days from what the formula would predict, then it was assumed that the participant reported inaccurate information and these participants were excluded from the analyses. Pregnant participants and those who were taking hormonal contraceptives or supplements were also excluded.

High- and low-fertility days were estimated using the modified backward counting method, which assumes that ovulation occurs 14 days prior to the onset of the next menses (Gildersleeve et al., 2014). High-fertility days were defined as the five days prior to ovulation and the day of ovulation because these are the days on which conception is most likely to occur (Wilcox, Dunson, Weinberg, Trussell, and Baird, 2001), and low-fertility days included the remainder of the cycle. Furthermore, a comparison of the actual conception probabilities between the high- and low-fertility groups was conducted to determine whether this grouping was accurate.

Participants

Sample A. Sample A in the present study included 309 female undergraduates from three women's universities in Japan. The study was conducted in several classes and the participants did not receive a monetary reward for their involvement. Each participant received a booklet containing questions regarding the preference rating and the menstrual cycle survey in a classroom. After the exclusion of participants who provided inaccurate information and/or did not complete the questionnaire, the ratings of 131 women (mean age: 19.0 ± 1.0 years) were analyzed for each item. Of these participants, 15 were in the high-fertility period and 116 were in the low-fertility period. Based on a Welch two-sample t-test, conception probability (Wilcox et al., 2001) was significantly higher in the high-fertility group (mean probability = 0.059 ± 0.021) than the low-fertility group (M = 0.020 ± 0.022), t(18.02) = 6.46, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.75.

Sample B. Sample B in the present study included 764 Japanese female undergraduates recruited through Macromill, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), which is a research agency that maintains a panel of more than 500,000 individuals who have provided informed consent and have agreed to participate in web-based online survey research. The candidates were asked whether they would reply to private questions, such as those regarding menstrual cycles, and only those who consented were included in the analyses. Each participant answered questions regarding their preference rating and the menstrual cycle survey using an online survey. Following the exclusion of participants who provided inaccurate information and/or did not complete the questionnaire, the ratings of 481 women (mean age: 20.7 ± 1.3 years) were analyzed for each item. Of these participants, 88 were in the high-fertility period and 393 were in the low-fertility period. Using a Welch two-sample t-test, conception probability was significantly higher in the high-fertility group (mean probability = 0.058 ± 0.023) than in the low-fertility group (M = 0.020 ± 0.023), t(128.49) = 14.05, p < .001, Cohen's d = 1.66.

Statistical analyses

The desirability scores from sample A and B were combined and analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the recipient of the altruistic behaviors (family, friends and acquaintances, or strangers) and partner type (short- or long-term relationship) as within-subject variables, and the fertility of the participants (high or low) and the sample (A or B) as a between-subject variable.

Results

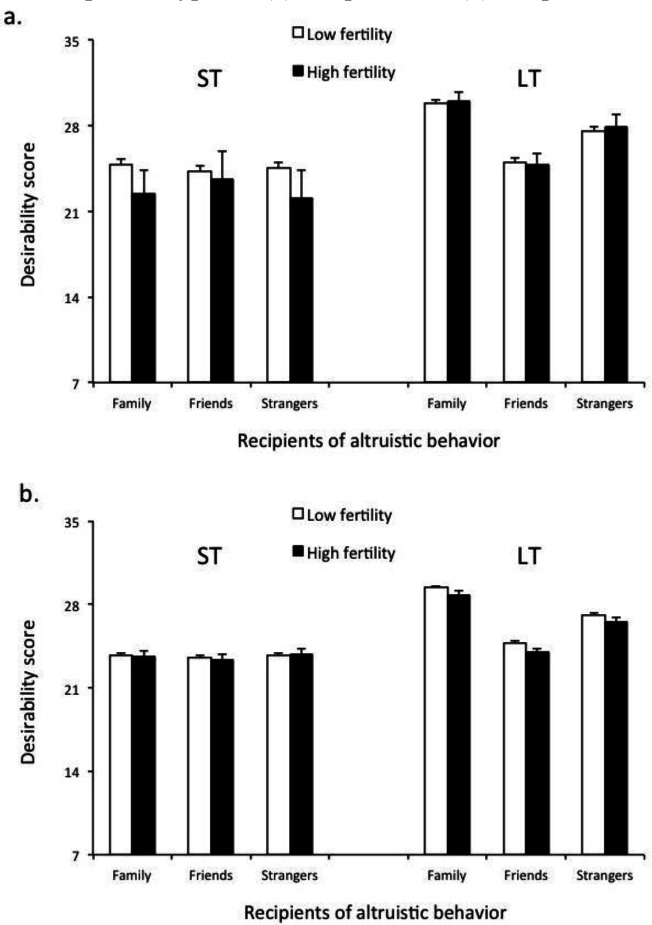

The desirability scores for altruistic behaviors toward each type of recipient for both short-term and long-term mates are provided (see Figure 1; see Table A1 in Appendix for more details). The main effects of partner type and recipient were significant, as was the interaction (see Table 2). The simple effects of the interaction indicated that there were no differences in the preference for altruistic behaviors toward each recipient in short-term relationships, F(2,1216) = 0.13, p = .88, whereas the preference for altruism differed significantly according to the recipient type in long-term relationships, F(2,1216) = 182.40, p < .001, η2G = 0.08. A multiple comparison revealed that altruism toward family members was the most desired, and the second was altruism toward strangers. Neither the main effect of fertility of the participants nor the first-order interactions between fertility and the other factors were significant. Although a second-order interaction among fertility, sample, and partner type was significant, the effect size was relatively small. The pattern of desirability score suggested that fertility had some effect only in short-term relationships in sample A (see Figure 1a). Therefore, we analyzed the interaction between fertility and sample in short-term relationships. The result of the three-way ANOVA with the recipient of the altruistic behaviors (family, friends and acquaintances, or strangers) as within-subject variables and the fertility of the participants (high or low) and the sample (A or B) as between-subject variables indicated that there was no significant interaction between fertility and sample, F(1,608) = 1.97, p = .16.

Figure 1.

Mean and SE of desirability score by questionnaire divided by each recipient of altruistic behaviors and partner type for (a) sample A and (b) sample B

Note. ST = short-term relationship; LT = long-term relationship

Table 2.

Result of four-way ANOVA on the desirability score

| Factor | F | df | p | η2G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | Fertility | 1.68 | 1, 608 | .20 | 0.002 |

| Sample | 0.59 | 1, 608 | .44 | 0.001 | |

| Partner type | 134.50 | 1, 608 | < .001 | 0.051 | |

| Recipient | 75.18 | 2, 1216 | < .001 | 0.016 | |

| Interactions | Fertility × Sample | 0.28 | 1, 608 | .60 | 0.000 |

| Fertility × Type | 1.14 | 1, 608 | .29 | 0.000 | |

| Sample × Type | 1.43 | 1, 608 | .23 | 0.001 | |

| Fertility × Sample × Type | 4.48 | 1, 608 | .04 | 0.002 | |

| Fertility × Recipient | 0.31 | 2, 1216 | .73 | 0.000 | |

| Sample × Recipient | 0.22 | 2, 1216 | .80 | 0.000 | |

| Fertility × Sample × Recipient | 0.66 | 2, 1216 | .52 | 0.000 | |

| Type × Recipient | 110.73 | 2, 1216 | < .001 | 0.017 | |

| Fertility × Type × Recipient | 1.96 | 2, 1216 | .14 | 0.000 | |

| Sample × Type × Recipient | 2.49 | 2, 1216 | .08 | 0.000 | |

| Fertility × Sample × Type × Recipient | 1.66 | 2, 1216 | .19 | 0.000 |

Discussion

The findings from this study demonstrate that women preferred altruistic behaviors in long-term relationship partners more than in short-term relationship partners. This preference was particularly pronounced for altruistic behaviors toward family members. Moreover, this finding was not influenced by the difference between samples, which indicates that this is a robust finding. Although Farrelly (2011) did not consider differences in the recipients of the altruistic behavior in their analyses, the present study revealed that these differences were manifested to a greater degree in the preference for altruism toward family members. According to Oda et al. (2014), who investigated the relationships among the subscales of the SRAS-DR and the Big Five personality scale, conscientiousness significantly contributes to altruism toward family members. People low in conscientiousness were less responsible to their partners, while highly conscientious people were less likely to get divorced (Roberts, Jackson, Fayard, Edmonds, and Meints, 2009). This strongly suggests that altruism in men is a signal of willingness to provide resources to future children. The second-most preferred altruistic behavior were that toward strangers, which was significantly more preferred than that toward friends or acquaintances. Although a woman can view altruistic behavior toward family members as a signal of willingness to care for future children, it is useless to choose a faithful man as her partner if he has no resources to provide. Altruistic behaviors toward strangers require enough resources to spare for performing. Therefore, it might be a signal of having resources or of the potential for resource acquisition. Our results, however, suggest that it is not a signal of genetic quality.

High- and low-fertility women did not differ in their preferences for men's altruistic behavior, which corroborates the findings of Farrelly (2011). The only possible effect was the second-order interaction among fertility, sample, and partner type. However, the pattern of desirability scores revealed that, in sample A, women in low-fertility tended to prefer male altruism when selecting short-term relationship partners than women in high-fertility (though the interaction was not significant), which was contrary to our prediction. Although both the questionnaire study and the online survey were performed on female undergraduates, the situations and environments in which the participants were placed were different. The questionnaire study was performed in various classrooms at women's universities, whereas the online survey was not restricted to students at women's universities and individuals responded to the scale independently using a personal computer. A number of factors, such as the frequency of interaction with men of the same age, might have caused the subtle second-order interaction. Oda, Shibata, et al. (2013) found that, compared to men, women more strongly prefer altruism toward strangers irrespective of relationship/partner type. Thus, the authors hypothesized that altruistic behaviors toward strangers are costly signals that indicate men's genetic quality. The results of the present, study, however, do not support that hypothesis. The results of Farrelly (2011) and the present study suggest, instead, that men's altruistic behaviors function more as signals of their willingness to provision than as signals of their genetic quality.

Negative results may raise the question of whether the methods employed in this study were appropriate. Because the present study utilized between-subject comparisons, individual differences in preference could weaken the possible effects of fertility. However, the ovulation estimation methods used here have been employed by numerous previous studies. In fact, shifts in women's preference for other cues of genetic quality based on ovulation were revealed using the same estimation method (Gildersleeve et al., 2014). Moreover, we analyzed a sufficient sample, and similar results were obtained using two different sampling methods; the questionnaire and the web-based online survey. Nevertheless, to confirm the present results, further studies on preference shifts using within-subject methods are needed. Hormonal measures of fertility have been employed in several previous studies (e.g., Haselton, Mortezaie, Pillsworth, Bleske-Rechek, and Frederick, 2007), which would also advance our findings.

One limitation of this study is in the SRAS-DR, in which the situations and behaviors referenced by items differ across recipients because each item describes a specific and realistic example. A possible solution would be to use the same items for each category of recipient. For example, “I have listened to the troubles and complaints of family members” and “I have listened to the troubles and complaints of strangers” as well as “I have listened to the troubles and complaints of a friend/acquaintance.” This would allow for comparisons of desirability of each behavior with that of other behaviors. However, few opportunities to listen to the troubles and complaints of strangers exist compared with the opportunities to listen to those of family members and friends. During the development of the SRAS-DR, students were asked to describe their altruistic behavior in daily life and to classify it according to recipient. Listening to the troubles of strangers was not mentioned at that time, indicating that the frequency of that behavior was lower than that of listening to the troubles of family members or friends. Low-frequency behavior would not function as an effective signal. Moreover, when one considers behavior as a signal, the recipients of such behaviors and the behaviors themselves are inseparable and co-vary. That is, the tendency to be generous toward strangers implies the ability to perform the kind of behavior that would qualify as being generous toward strangers. The recipient of an altruistic behavior and the behavior itself function together as a signal.

Another limitation is that the participants were restricted to undergraduates. The SRAS-DR was developed to investigate the frequency of altruistic behavior in Japanese undergraduate students. Because each item describes a specific and realistic example, it is difficult to apply the scale to other groups that may differ in terms of age and/or socio-cultural background. Indeed, it is valid to employ undergraduate students as a sample for this type of study because this population is in the peak of fertility and mate preference might directly influence their reproductive fitness in an ancestral environment. Regardless, similar research should be conducted using female subjects from a broader group of ages and a variety of socio-cultural backgrounds.

In conclusion, it is suggested that men's altruistic behavior functions as a signal of willingness to provision toward their future children in a long-term relationship and female choice has driven the evolution of men's display of their altruism. The meaning of altruistic behavior differs with relationships between the altruists and the recipients. Men's altruistic behaviors, therefore, convey different information depending on their recipients. This is the first study examining women's preference for men's altruistic behavior from such a viewpoint. Further studies are expected to investigate whether the actual selection of spouse reflects this preference.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Dr. April Bleske-Rechek, Dr. Daniel Farrelly, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25501003.

Appendix

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of desirability scores

| Sample | Type | Fertility | Recipient | N | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Short | Low | Family | 116 | 24.8 | 5.3 | 14 | 35 |

| Friends | 116 | 24.3 | 4.2 | 15 | 35 | |||

| Strangers | 116 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 10 | 35 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| High | Family | 15 | 22.4 | 7.7 | 7 | 33 | ||

| Friends | 15 | 23.6 | 9.0 | 7 | 35 | |||

| Strangers | 15 | 22.1 | 8.8 | 7 | 34 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Long | Low | Family | 116 | 29.8 | 3.2 | 23 | 35 | |

| Friends | 116 | 25.0 | 3.6 | 15 | 35 | |||

| Strangers | 116 | 27.5 | 4.3 | 17 | 35 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| High | Family | 15 | 30.0 | 3.0 | 24 | 34 | ||

| Friends | 15 | 24.8 | 3.5 | 18 | 31 | |||

| Strangers | 15 | 27.9 | 4.0 | 22 | 35 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| B | Short | Low | Family | 393 | 23.7 | 4.8 | 7 | 35 |

| Friends | 393 | 23.5 | 4.2 | 7 | 35 | |||

| Strangers | 393 | 23.7 | 4.6 | 7 | 35 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| High | Family | 88 | 23.6 | 4.4 | 13 | 35 | ||

| Friends | 88 | 23.4 | 3.6 | 12 | 35 | |||

| Strangers | 88 | 23.8 | 4.3 | 14 | 35 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| Long | Low | Family | 393 | 29.4 | 3.2 | 16 | 35 | |

| Friends | 393 | 24.8 | 3.4 | 16 | 34 | |||

| Strangers | 393 | 27.1 | 4.0 | 15 | 35 | |||

|

|

||||||||

| High | Family | 88 | 28.8 | 3.1 | 21 | 34 | ||

| Friends | 88 | 24.0 | 3.1 | 15 | 33 | |||

| Strangers | 88 | 26.5 | 3.9 | 16 | 35 | |||

Contributor Information

Ryo Oda, Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya Institute of Technology, Nagoya, Japan.

Akari Okuda, Department of Computer Science, Nagoya Institute of Technology, Nagoya, Japan.

Mia Takeda, Department of Liberal Arts, Aoyama Gakuin Women's Junior College, Tokyo, Japan.

Kai Hiraishi, Faculty of Psychology, Yasuda Women's University, Hiroshima, Japan.

References

- Barclay P. (2010). Altruism as a courtship display: Some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions. British Journal of Psychology, 101, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereczkei T., Voros S., Gal A., Bernath L. (1997), Resources, attractiveness, family commitment: Reproductive decisions in human mate choice. Ethology, 103, 681–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brase G. L. (2006). Cues of parental investment as a factor in attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. M., Schmitt D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly D. (2011). Cooperation as a signal of genetic or phenotypic quality in female mate choice? Evidence from preferences across the menstrual cycle. British Journal of Psychology, 102, 406–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly D., Lazarus J., Roberts G. (2007). Altruists attract. Evolutionary Psychology, 5, 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Gildersleeve K., Haselton M. G., Fales M. R. (2014). Do women's mate preferences change across the ovulatory cycle? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1205–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behavior I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselton M. G., Mortezaie M., Pillsworth E. G., Bleske-Rechek A., Frederick D. A. (2007). Ovulatory shifts in human female ornamentation: Near ovulation, women dress to impress. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iredale W., Van Vugt M., Dunbar R. I. M. (2008). Showing off in humans: Male generosity as a mating signal. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewski A. W., Roney J. R. (2009). Estimated hormones predict women's mate preferences for dominant personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Oda R. (2001). Sexually dimorphic mate preference in Japan: An analysis of lonely hearts advertisements. Human Nature, 12, 191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda R., Dai M., Niwa Y., Ihobe H., Kiyonari T., Takeda M., Hiraishi K. (2013). Self-Report Altruism Scale Distinguished by the Recipient (SRAS-DR): Validity and reliability. Shinrigakukenkyu [The Japanese Journal of Psychology], 84, 28–36. (Japanese with English abstract). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda R., Machii W., Takagi S., Kato Y., Takeda M., Kiyonari T., Hiraishi K. (2014). Personality and altruism in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Oda R., Shibata A., Kiyonari T., Takeda M., Matsumoto-Oda A. (2013). Sexually dimorphic preference for altruism in the opposite-sex according to recipient. British Journal of Psychology, 104, 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T., Barnard C., Ferguson E., Reader T. (2008). Do humans prefer altruistic mates? Testing a link between sexual selection and altruism towards non-relatives. British Journal of Psychology, 99, 555–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillsworth E. G., Haselton M. G. (2006). Women's sexual strategies: The evolution of long-term bonds and extrapair sex. Annual Review of Sex Research, 17, 59–100. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B. W., Jackson J. J., Fayard J. V., Edmonds G., Meints J. (2009) Conscientiousness. In Leary M. R., Hoyle R. H. (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 257–273). New York/London: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tognetti A., Berticat C., Raymond M., Faurie C. (2012). Sexual selection of human cooperative behavior: An experimental study in rural Senegal. PLOS ONE, 7, e44403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vugt M., Iredale W. (2013). Men behaving nicely: Public goods as peacock tails. British Journal of Psychology, 104, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A. J., Dunson D. B., Weinberg C. R., Trussell J., Baird D. D. (2001). Likelihood of conception with a single act of intercourse: Providing benchmark rates for assessment of post-coital contraceptives. Contraception, 63, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W., Kerssel L., Joshi P. D., Louie B. (2014). Meta-analysis of menstrual cycle effects on women's mate preferences. Emotion Review, 6, 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi A. (1975). Mate selection: Selection for a handicap. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 53, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi A. (1995). Altruism as a handicap: The limitation of kin selection and reciprocity. Journal of Avian Biology, 26, 1–3. [Google Scholar]