Highlights

-

•

CRPC patients have abundant SCFAs-producing gut microbiotas.

-

•

CRPC fecal microbiota transplantation or SCFAs gavage to mice promote PCa progression.

-

•

SCFAs can enhance PCa cells invasiveness via inducing TLR3-mediated autophagy.

-

•

Microbiota dysbiosis-induced CCL20 in prostate could be used to predict prognosis.

Keywords: CRPC, Gut microbiota dysbiosis, SCFAs, Autophagy, Macrophage polarization

Abstract

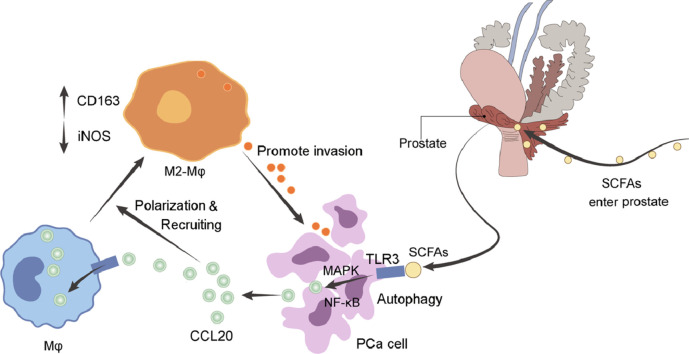

We have previously demonstrated abnormal gut microbial composition in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients, here we revealed the mechanism of gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) as a mediator linking CRPC microbiota dysbiosis and prostate cancer (PCa) progression. By using transgenic TRAMP mouse model, PCa patient samples, in vitro PCa cell transwell and macrophage recruitment assays, we examined the effects of CRPC fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and SCFAs on PCa progression. Our results showed that FMT with CRPC patients’ fecal suspension increased SCFAs-producing gut microbiotas such as Ruminococcus, Alistipes, Phascolarctobaterium in TRAMP mice, and correspondingly raised their gut SCFAs (acetate and butyrate) levels. CRPC FMT or SCFAs supplementation significantly accelerated mice's PCa progression. In vitro, SCFAs enhanced PCa cells migration and invasion by inducing TLR3-triggered autophagy that further activated NF-κB and MAPK signalings. Meanwhile, autophagy of PCa cells released higher level of chemokine CCL20 that could reprogramme the tumor microenvironment by recruiting more macrophage infiltration and simultaneously polarizing them into M2 type, which in turn further strengthened PCa cells invasiveness. Finally in a cohort of 362 PCa patients, we demonstrated that CCL20 expression in prostate tissue was positively correlated with Gleason grade, pre-operative PSA, neural/seminal vesical invasion, and was negatively correlated with post-operative biochemical recurrence-free survival. Collectively, CRPC gut microbiota-derived SCFAs promoted PCa progression via inducing cancer cell autophagy and M2 macrophage polarization. CCL20 could become a biomarker for prediction of prognosis in PCa patients. Intervention of SCFAs-producing microbiotas may be a useful strategy in manipulation of CRPC.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The microbiota in gastrointestinal (GI) tract is closely related to host immunity. Growing evidence have proved that gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in maintaining fully functional immune responses, not only in local but also systemic immune system [1]. In normal circumstances, the GI tract provides a tight junction recognizing and blocking the entry of pathogens. However, gut microbiota dysbiosis may break the seal and allow for permeability of molecules that are able to disorder immune responses and raise cancer risks [2]. We have previously reported abnormal gut microbial composition in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients in comparison to hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (HSPC) patients, as manifested by increased abundance of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-producing bacteria including Ruminococcus, Alistipes, Phascolarctobaterium, et al [3,4]. CRPC can develop drug resistance and is still incurable for the moment. SCFAs are the products of GI bacterial metabolism, they can modulate tumor microenvironment (TME) by regulating the activity of immune cells [5,6]. SCFAs influence cancer destiny in a cell-specific and dose-dependent manner [7,8], Matsushita et al. once reported the involvement of fat intake induced SCFAs in mice prostate cancer (PCa) progression [9]. However, the mechanism of microbiota dysbiosis in CRPC remains unclear and deserves further investigations.

Autophagy is evolutionary conserved process through which cytoplasmic materials are delivered to lysosome for degradation. It plays dual roles in cancer progression depending on the cell types and cancer stages. In advanced malignant diseases, autophagy-mediated signalings are activated to maintain energy and mitochondrial function that prerequisite for cell growth and proliferation [10]. It is not surprising that autophagy impacts on the immune system, coordinates with macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, T&B cells to regulate innate and adaptive immune responses [11]. Autophagy in cancer cells could incur immune escape and promote cell survival, while disruption of autophagy drastically compromises cancer progression [12].

Macrophages (Mφ), the most abundant infiltrative immune-related cells present in TME, often dictate the tone of immune responses [13]. They are generally classified as either pro-inflammatory M1 type macrophages or immuno-suppressive M2 type macrophages. M1 macrophages are characterized by markers including IL-1β, IL-12, TNF-α, iNOS that inhibit cancer progression, while M2 macrophages are identified by markers such as IL-10, Arg1, CD163, CD206 that favor cancer progression [14]. The status of Mφ are pliable and are determined by signals that they receive.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are one of the ancient families that were early recognized as pattern recognition receptors. They are main components of innate immune system, and are important regulators of adaptive immune responses [15]. TLRs play a complex role in cancer, many studies reported overexpression of TLRs during cancer invasion and metastasis, though others claimed that TLRs suppressed cancer cell proliferation [16,17]. Release of immunosuppressive factors triggered by TLRs signalings can hamper immune cell function and enhance resistance of cancer cell to chemotherapy or immunotherapy. For example, TLR3/4 activation induced lung cancer cell autophagy and facilitated cancer progression through the promotion of TRAF6 ubiquitination [18]. TLRs are present in a wide variety of immune and cancer cells. In this report, we showed that CRPC gut microbiota-derived SCFAs enhanced PCa cells migration and invasion through TLR3-triggered autophagy. Meanwhile, PCa cell autophagy-derived chemokine CCL20 recruited more M2 macrophage infiltration that further strengthened PCa cells invasiveness. Our results implicated that intervention of microbiotas may become a potential therapy approach for CRPC patients.

Materials and methods

Human subjects and fecal collection

This study was approved by IRB of Huashan hospital, Fudan University (Grant No.2020-531). All participants were informed of the aim of the study and signed the informed consent. PCa patients accepting surgical, hormonal, or any other kinds of therapies were collected at our urological department between Jan 2007 and December 2020. The diagnostic criteria of CRPC and HSPC were complied with EAU guidelines on PCa [19], and the recruitment criteria of the two cohorts of patients were described in our previous studies [3]. Fresh feces were collected by patients themselves using a sterile “feces tube” with sealed screw cap. Samples were immediately sub-packaged and stored frozen at -80℃ until use.

Animals

This animal study was approved by IRB of Huashan hospital, Fudan University (Grant No. 2020-JS252). TRAMP mice were introduced from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, United States) and bred in Institute of Development Biology and Molecular Medicine of Fudan University. TRAMP male mice (age of 8 weeks) were randomly divided into four groups (n=10 for each group), singly housed, and maintained in a standard 12 h light/dark condition with free access to rodent feed and water. Mice were treated with antibiotics containing 0.2 g/L ampicillin, neomycin, metronidazole, and 0.1 g/L vancomycin in drinking water for 1 week before human fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) or SCFAs supplementation. For FMT, feces from five randomly selected either CRPC or HSPC patients were mixed with saline solution (20 mg ml−1) at equal weights, vortexed and centrifuged. Each time an aliquot of 200 µl of fecal suspension was administered to mice by oral gavage. For SCFAs supplementation experiment, a cocktail of 200 µl of SCFAs mixture (67.5 mM sodium acetate, and 40 mM sodium butyrate) [20] or saline solution was administered to mice by oral gavage. FMT or SCFAs were administrated twice a week and maintained for 16 weeks, then mice were anesthetized and sacrificed to collect feces and prostate.

16s rRNA sequencing and analysis

The fecal DNA of mice accepting FMT were extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Netherlands) following manufacturer's instruction. Regions V3–V4 of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using the forward primer 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′, and the reverse primer 5′- GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′. The PCR program was set as follow: 98°C 10min, 25 cycles of 98°C 15 s, 55°C 30 s, 72°C 30 s, 72°C 5 min. Equimolar amplicon pool was obtained, and paired-end 2×300 bp sequencing was performed at Illlumina MiSeq platform (Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). Low-quality reads and adapter contamination were discarded. High-quality reads were aligned using FLASH, and operational taxonomic units (OTUs) was delineated using UCLUST at 97% cutoff. LEfSe analysis was used to detect differential microbiotas [21].

SCFAs analysis

The SCFAs content of mice feces or prostate were quantified with an Agilent 7890A Gas chromatograph coupled to Pegasus GC-TOFMS system (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph). An amount of 100 mg feces or 100 mg prostate tissues of each sample was added to 50µl 15% phosphoric acid, 100µl 125µg/ml internal standard (isohexanoic acid), and 400 µl ether. Samples were vortex mixed for 1 min, and centrifuged at 14000g 4°C for 10min. A 200 µl aliquot of supernatant was finally transferred to test. The GC-GC-TOFMS separation was performed using an Agilent HP-INNOWAX capillary column (30m × 0.25mm ID × 0.25µm, Waters, Ireland). The parameters were set as follow: helium gas flow=1 ml/min; column temperature= 70°C for 1min, raised to 170°C at 10°C/min, raised to 240°C at 25°C/min and maintained for 2 min; inlet, interface, and ionization source temperatures= 250°C, 230°C, and 250°C; electron impact ionization= 70 eV; injection volume= 1µl; m/z scan range= 40-550. SCFAs were analyzed in full scan mode [22]. ChromaTOFⓇ software (LECO Corporation) was used to collect and process data. Identification of SCFAs was carried out by referring to NIST Standard Reference Data.

Prostate histopathology

Mice prostate were sectioned and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, placed in 70% ethanol and dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological diagnosis were blindly given by two independent skilled uropathologists at our hospital according to a modified grading system of prostate histopathology for TRAMP mice [23]. The histologic features were classified as: (I) normal tissue (NT); (II) low-grade PIN (LGPIN); (III) high-grade PIN (HGPIN); (IV) well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (WD-Adeno); and (V) poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma (PD-Adeno). Quantitative analysis was conducted as previously described with minor modification, 10 random fields were captured at 10 magnification, with the most advanced histological feature in each field was included in calculation. The numbers and percentages of different subtypes of lesions were established and compared among groups.

Cell culture

Human PCa cell lines (DU145, PC3) and murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 were obtained from Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All the cell lines were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 using RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin.

SCFAs treatment, wound-healing and matrigel invasion assay

Different doses of SCFAs mixture (0.02mM, 0.2mM, and 2mM, with a ratio of sodium acetate to sodium butyrate at 1:1) were used to treat PCa cells. For the wound-healing assay, PCa cells (1×105) were seeded to confluence in 12-well plates. A monolayer was scratched, and the cells were cultured in complete medium supplemented with/without SCFAs. Cells were photographed at 0 h, 12 h and 24 h, and the closure area of wound was calculated. For the matrigel invasion assay, PCa cells (1×105) with serum-free medium were placed in the upper chambers of 24-well transwell plates coated with matrigel, supplemented with/without SCFAs, while the bottom chambers were filled with complete medium. After 48 h, cells attached to the upper surface of the membrane were removed, whereas cells reached to the underside of the chamber were fixed, stained, and counted. To determine the impact of macrophages on PCa cells, PCa/macrophage cells were co-cultured in 24-well transwell plates for 48 h, supplemented with/without SCFAs, the CM (condition medium) or control media were collected, diluted with 10% FBS (1:1), and placed into the lower chambers of 24-well transwell plates. PCa cells with serum-free medium were placed in the upper chambers to perform matrigel invasion assay. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Transmission electron microscopy

PCa cells treated with/without SCFAs were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4 h, post fixed in 1% OsO4 for 1 h, rinsed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol. Then, cells were consecutively infiltrated with acetone and epoxy resin (2:1), acetone and epoxy resin (1:1), and epoxy resin for 24 h. Finally, cells were embedded in epoxy resin for 48 h at 60°C. Sections were made at a thickness of 80 to 100 nm, stained with aqueous uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and then analyzed with transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai G2 20 TWIN). For each group, 20 independent sectioned cells were examined and the number of autophagosomes per cross-sectioned cell was calculated [24].

RNA-seq transcriptome analysis

Total RNA of SCFAs-challenged DU145 cells were extracted using TRIzolⓇ Reagent (Invitrogen). Untreated DU145 cells were used as control. The cDNA library was prepared with 1 µg of total RNA using the TrueSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). The mRNAs was separated using Oligo (dT) magnetic beads, and cDNA library was amplified and sequenced using an Illumina PE 250 platform. Raw reads were filtered using Trimmomatic software (Version 0.32) to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads (base quality <20, read length <75 bp). The high-quality clean reads were mapped to reference genome using HISAT2 software (Version 2.2.1), and processed to gain FPKM value using HTseq software (Version 0.9.1) to ascertain differential genes between groups. Functional annotations were conducted by comparing reads to databases of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.genome.jp/kegg) [25].

Macrophage recruitment assay

PCa cells were cultured with/without SCFAs for 48 h, the CM or control media were collected, diluted with 10% FBS, and placed into the lower chambers of 24-well transwell plates. RAW264.7 cells (1×105) with serum-free medium were placed in the upper chambers without matrigel to perform macrophage migration assay [26]. After 48 h, the migrated cells were collected, stained, and counted. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Western blot

Mice prostate tissues or human PCa cell lines were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich), and concentrated using BCA Protein Assay kit (Vigorous Biotechnology, China). Equal proteins were resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE before being transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST buffer and incubated with anti-LC3 (1: 800, 12741S, Cell Signaling), anti-TLR3 (1:800, 17766-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-total-NF-κB (1:1000, 4764S, Cell Signaling, USA), anti-Phospho-NF-κB (1:1000, 3033S, Cell Signaling), anti-ERK (1:1000, 11257-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-Phospho-ERK (1:1000, 28733-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-MEK (1:1000, 4694S, Cell Signaling), anti-Phospho-MEK (1:1000, 3958S, Cell Signaling), anti-MAPK (1:1000, 4695S, Cell Signaling), anti-Phospho-MAPK (1:1500, 4370S, Cell Signaling) at 4°C overnight and HRP-coupled secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1h. GAPDH and β-ACTB were used as internal controls.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on prostate sections of TRAMP mice and PCa patients, respectively. Primary antibodies against F4/80 (1:500, 28463-1-AP, Proteintech), CD163 (1:500, 16646-1-AP, Proteintech), iNOS (1:200, 18985-1-AP, Proteintech), CCL20 (1:200, PA5-114709, Invitrogen), and CCR6 (1:400, 66801-1-Ig, Proteintech) were used. After washing 3 times with PBS, the sections were incubated with HRP-coupled secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. DAB was added for 3-4 min, then slides were dehydrated with increasing ethanol concentrations and xylene, and sealed. The scores of Mφ markers (F4/80, CD163, iNOS) were calculated by counting the positively stained cells per area from 10 random fields at 40 magnification. The scores of CCL20 and CCR6 were classified into three groups according to the staining intensity (score 1 to 3) from 10 random fields at 40 magnification. Human rectal cancer specimen was used as positive control and negative control was achieved by replacing these antibodies with phosphate buffer saline.

Quantitative RT-PCR and Elisa

Total RNA extraction of mice prostate tissues or human PCa cell lines were carried out using TRIzolⓇ reagent (Invitrogen). The cDNA was obtained using a HiScriptⓇ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, China). qRT-PCR was carried out using a AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme) on ABI PrismⓇ 7900HT sequence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Expression fold changes were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Also, the ELISA kit (R & D Systems) was used to detect the levels of IL6, CCL20, TNF, MMP3 and MMP9 in culture supernatant. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Autophagy inhibition and RNA interference

PCa cells were co-treated with 3-MA (5 mM, Sigma-aldrich), or transfected with siRNAs targeting TLR3 (sc-36685, Santa Cruz) or CCL20 (sc-43935, Santa Cruz) for 48 h before performing wound-healing, matrigel invasion, and macrophage recruitment assay. Cell transfection were conducted via LipofectamineⓇ 3000 (Invitrogen) according to provided protocols.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism Version 8.0 was used for data analysis. Two-tailed Student's t-test was used to evaluate statistical significance between two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate statistical significance among three or more groups. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to analyze nonparametric data. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as medians with inter-quartile ranges. P ≤ 0.05 indicated statistically significant difference.

Results

FMT with CRPC fecal suspension promoted PCa progression and increased gut microbiota- derived SCFAs

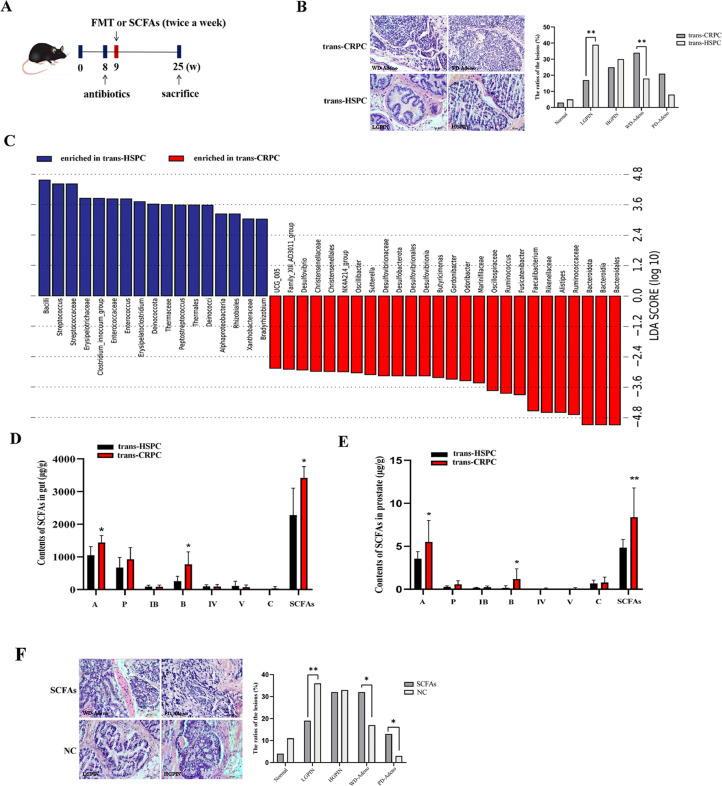

To determine the effect of FMT on prostate pathogenesis, fecal suspension from CRPC or HSPC patients were transplanted to TRAMP mice by oral gavage (Fig. 1A). After 16 weeks, mice that accepted CRPC fecal suspension (trans-CRPC) had more WD-Adeno lesions (p=0.0069) and fewer LGPIN lesions (p=0.0013), while mice that accepted HSPC fecal suspension (trans-HSPC) had fewer WD-Adeno lesions and more LGPIN lesions (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that CRPC fecal suspension may promote PCa progression from LGPIN to WD-Adeno. We next to studied the effect of FMT on gut microbiota, the mice's feces were collected and sent to 16s rRNA sequencing. LefSe analysis identified a series of key differential microbiotas between the two groups, the trans-CRPC group was characterized by significantly increased abundance of Bacteroidales, (Bacteroidia, Bacteroidota), Ruminococcaceae (Ruminococcus), Alistipes, Rikenellaceae, and Faecalibacterium, etc (Fig. 1C). Since a large proportion of these differential microbiotas were SCFAs-producing bacteria [27,28], we further used targeted metabolomics to examine the contents of SCFAs in mice's feces and prostate tissues. We found the contents of SCFAs in gut were significantly increased in trans-CRPC group (p=0.021), especially acetate (p=0.035) and butyrate (p=0.023) (Fig. 1D). And correspondingly, acetate (p=0.032) and butyrate (p=0.015) were also increased in mice prostate after CRPC FMT (Fig. 1E). To clarify the impact of SCFAs on PCa progression, we administrated TRAMP mice with a cocktail of acetate and butyrate mixture by oral gavage (Fig. 1A), and found SCFAs-treated mice had more WD-Adeno lesions (p=0.0154), PD-Adeno lesions (p=0.0461), and fewer LGPIN lesions (p=0.0074) in comparison to control group. SCFAs promoted PCa progression from LGPIN to WD-Adeno and PD-Adeno (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

CRPC FMT or SCFAs supplementation promoted TRAMP mice's PCa progression. A, Schematic model of FMT assay with CRPC or HSPC patients’ fecal suspension, and SCFAs supplementation assay. B, Prostate histopathology of mice treated with CRPC FMT (trans-CRPC) or HSPC FMT (trans-HSPC) after 16 weeks. C, Lefse analysis of mice gut microbiotas after FMT. D, The contents of fecal SCFAs after FMT were analyzed with targeted metabolomics. A: acetic acid; P: propionic acid; IB: isobutyric acid; B: butyric acid; IV: isovaleric acid; V: valeric acid; C: caproic acid. E, The contents of prostate SCFAs after FMT. F, Prostate histopathology of mice treated with SCFAs mixture or saline solution after 16 weeks. Scale bar, 100 µm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

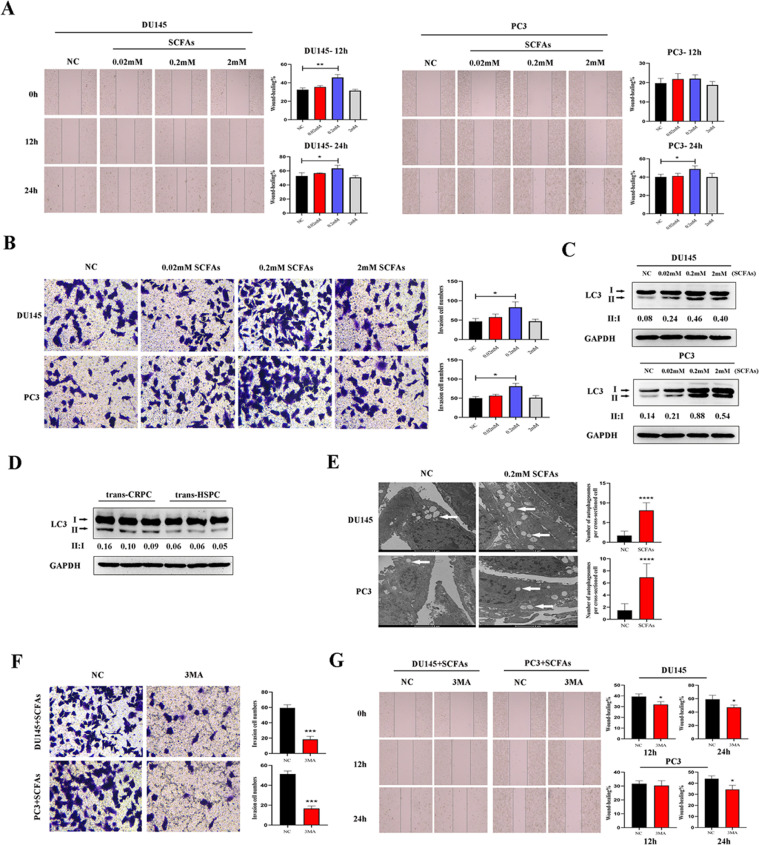

SCFAs induced autophagy and promoted migration and invasion of PCa cells

To explore how SCFAs affect the migration and invasion abilities of PCa cells in vitro, we treated DU145 and PC3 cells with different doses of SCFAs ranging from 0.02 mM to 2 mM. Wound-healing assay indicated that a little dose of 0.02 mM SCFAs slightly enhanced DU145 and PC3 cells migration, but no statistical significances were found. The 0.2 mM SCFAs significantly enhanced the migration of DU145 cell at 12 h (p=0.0037) and 24 h (p=0.0415), and the migration of PC3 cell at 24 h (p=0.0274). But when the dose reached to a higher level of 2 mM, the promotion effect of SCFAs on migration were reversed. Transwell matrigel invasion assay also indicated the significant promotion effect of 0.2 mM SCFAs on the invasion of DU145 cell (p=0.0173) and PC3 cell (p=0.0032) at 48 h (Fig. 2A, B). Meanwhile, we found SCFAs induced autophagy in PCa cells, which was shown by conversion of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3α/β (MAP1LC3A/B, LC3A/B)-I into LC3-II. Corresponding to wound-healing and matrigel invasion assays, 0.2 mM SCFAs triggered highest level of LC3-II aggregation and LC3 conversion (Fig. 2C). In parallel, upregulated expression of LC3-II and higher ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I were also seen in trans-CRPC mice prostate (Fig. 2D). Thus, we conducted following experiments using a dose of 0.2 mM SCFAs. To further prove the situation of autophagy in PCa cells, transmission electron microscopy was performed and more number of autophagosomes were seen in SCFAs-treated cells (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

SCFAs induced PCa cell autophagy and enhanced their migration and invasion abilities. A-B, DU145 and PC3 cells were treated with different doses of SCFAs mixture (0.02 mM, 0.2 mM, 2 mM, acetate/butyrate =1:1). Wound-healing and Transwell assays were used to analyze their migration and invasion abilities. C, Western blot analysis of LC3 in DU145 and PC3 cells after SCFAs administration. The 0.2 mM dose induced highest expression of LC3-II and ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I. D, Western blot analysis of LC3 in trans-CRPC and trans-HSPC mice. E, Transmission electron microscopy detected more autophagosomes (white arrow) in DU145 and PC3 cells after SCFAs administration (0.2 mM). F-G, Transwell and Wound-healing assays were conducted on PCa cells when co-treated cells with autophagy inhibitor 3MA in the presence of SCFAs (0.2 mM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Inhibition of autophagy suppressed cell migration and invasion

To further illustrate the role of autophagy in cell migration and invasion, we treated DU145 and PC3 cells with SCFAs (0.2 mM) in the presence or absence of autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3MA). Transwell matrigel invasion assay showed that blockage of autophagy by 3MA significanly impaired the invasion of DU145 cell (p=0.0003) and PC3 cell (p=0.0001). And Wound-healing assay also showed that 3MA suppressed the migration of DU145 cell at 12 h (p=0.0253) and 24 h (p=0.0412), and the migration of PC3 cell at 24 h (p=0.0223) (Fig. 2F, G).

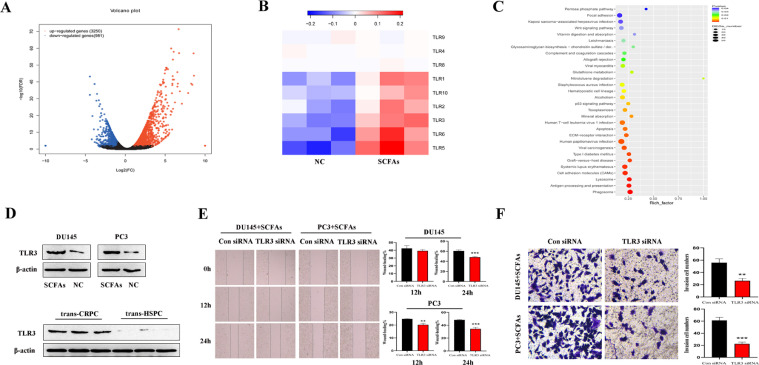

TLR3 triggered activation of NF-κB and MAPK signalings were involved in PCa cell autophagy

We next to studied the mechanism of involvement of SCFAs in PCa cell autophagy. The transcriptome profiles of SCFAs (0.2 mM)-treated DU145 cell and control DU145 cell were compared using RNA-seq transcriptome analysis. There were 3250 upregulated genes and 981 downregulated genes in the SCFAs group (Fig. 3A), with TLRs family among the most upregulated genes, especially TLR5, TLR6, and TLR3 (Fig. 3B). Also, the KEGG analysis indicated that SCFAs-treated cell were more enriched in autophagy-associated metabolic pathways, including phagosome, lysosome, etc (Fig. 3C). Since TLR3 could induce autophagy, and has been reported to be upregulated in several malignant diseases [29], we examined the protein expression of TLR3, and verified that TLR3 was correspondingly increased in SCFAs-treated DU145 and PC3 cells, as well as in trans-CRPC mice prostate (Fig. 3D). When using siRNA targeting TLR3, Wound-healing assay showed that TLR3 siRNA significanly impaired the migration of DU145 cell at 24 h (p=0.0009), and the migration of PC3 cell at 12h (p=0.0028) and 24 h (p=0.0007). And Transwell assay showed that TLR3 siRNA suppressed the invasion of DU145 cell (p=0.0023) and PC3 cell (p=0.0003) (Fig. 3E, F).

Fig. 3.

SCFAs upregulated TLR3 expression in PCa cells. A, Volcano plot of transcriptomics of DU145 cell treated with/without SCFAs (0.2 mM). B, The gene expression of most members of TLRs family were increased, including TLR5, TLR6, TLR3. C, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes annotation of key upregulated metabolic pathways in SCFAs-treated DU145 cell. D, Western blot analysis of TLR3 in PCa cells treated with/without SCFAs, as well as in trans-CRPC and trans-HSPC mice. E-F, Wound-healing and Transwell assays were conducted on PCa cells when using siRNA targeting TLR3.

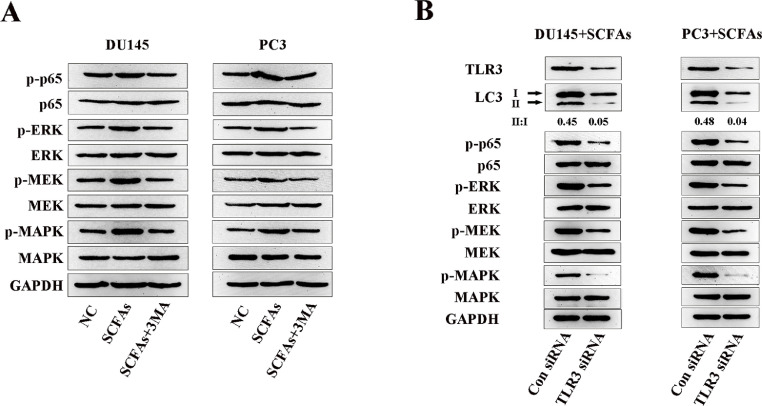

Stimulation of TLRs can induce activation of survival signalings such as NF-κB and MAPK [30], so we determined the expressions of NF-κB and MAPK/MEK/ERK in SCFAs-treated PCa cells on the protein level, and found the phosphorylation of NF-κB and MAPK/MEK/ERK were overexpressed. Meanwhile, co-treated cells with 3MA decreased their expressions (Fig. 4A). Correspondingly, using siRNA targeting TLR3 decreased the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I in PCa cells, as well as the expressions of phosphorylation of NF-κB and MAPK/MEK/ERK signalings (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results indicated that autophagy played an important role in TLR3-triggered activation of NF-κB and MAPK signalings.

Fig. 4.

TLR3 activated NF-κB and MAPK signalings were involved in autophagy.

A, Western blot analysis of phosphorylated (p-) and total level of NF-κB and MAPK/MEK/ERK in SCFAs-treated PCa cells in the presence or absence of 3MA. B, Western blot analysis of LC3, phosphorylated (p-) and total level of NF-κB and MAPK/MEK/ERK in SCFAs-treated PCa cells in the presence or absence of TLR3 siRNA.

SCFAs strengthened macrophage recruitment by PCa cells

Beside the direct effect on PCa cells, we also determined the role of SCFAs in the recruitment of macrophages to the TME by PCa cells. We conducted macrophage recruitment assay by collecting the condition medium (CM) from PCa cells treated with/without SCFAs (0.2 mM) for 48h. SCFAs was capable of strengthening DU145 cell (p<0.0001) and PC3 (p=0.0007) cell-induced macrophage recruitment (Fig. S1A). Meanwhile, higher mRNA expression of CD163 and lower mRNA expression of iNOS in PCa cell-recruited macrophages in the presence of SCFAs were revealed by qRT-PCR (Fig. S1B). We then examined the effect of macrophages on the invasion ability of PCa cells. PCa cells and macrophages were co-cultured with/without SCFAs (0.2 mM). As a result, macrophages were capable of enhancing the invasion of DU145 cell (p=0.0283) and PC3 cell (p=0.0029), and SCFAs was capable of strengthening the macrophage-enhanced processes (p=0.0178 for DU145, p=0.0004 for PC3) (Fig. S1C). We finally conducted IHC against F4/80, CD163, and iNOS on prostate of trans-CRPC and trans-HSPC mice, and found more infiltrated F4/80+ macrophages (p=0.0002) were present in trans-CRPC group. In addition, higher percentage of CD163+ macrophages (p<0.0001) and lower percentage of iNOS+ macrophages (p<0.0001) were seen in trans-CRPC group, which indicated polarization of macrophages toward M2 type (Fig. S1D).

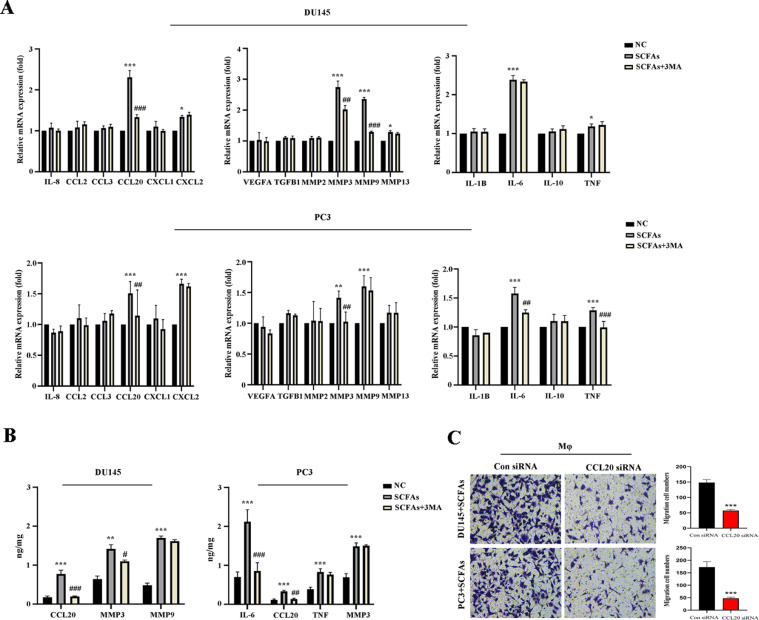

Autophagy induced production of CCL20 in PCa cells

To understand the mechanism that PCa cell recruited macrophages, we examined production of certain pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokines, and chemokines [18] in PCa cells treated with/without SCFAs (0.2 mM) in the presence or absence of 3MA. Remarkably, production of CCL20, MMP3, MMP9 in DU145 cell by SCFAs were reduced when blocking autophagy with 3MA. Similarly, production of CCL20, MMP3, IL-6, TNF in PC3 cell by SCFAs were reduced by 3MA (Fig. 5A). We further substantiated the levels of abovementioned cytokines or chemokines in the cell supernatant, and found CCL20 production was strongly correlated with autophagy in both DU145 and PC3 cells (Fig. 5B). Also, when using siRNA targeting CCL20, the recruitment of macrophages by PCa cells were significantly decreased (Fig. 5C). The qRT-PCR primers for cytokines and chemokines were summarized in Table S1.

Fig. 5.

Autophagy induced production of CCL20 in PCa cells. A, qRT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of cytokines and chemokines in PCa cells treated with/without SCFAs (0.2 mM) in the presence or absence of 3MA. B, Elisa analysis of cytokines and chemokines in PCa cells supernatant. C, Transwell assay was conducted on PCa cells when using siRNA targeting CCL20. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 when comapred to the SCFAs group.

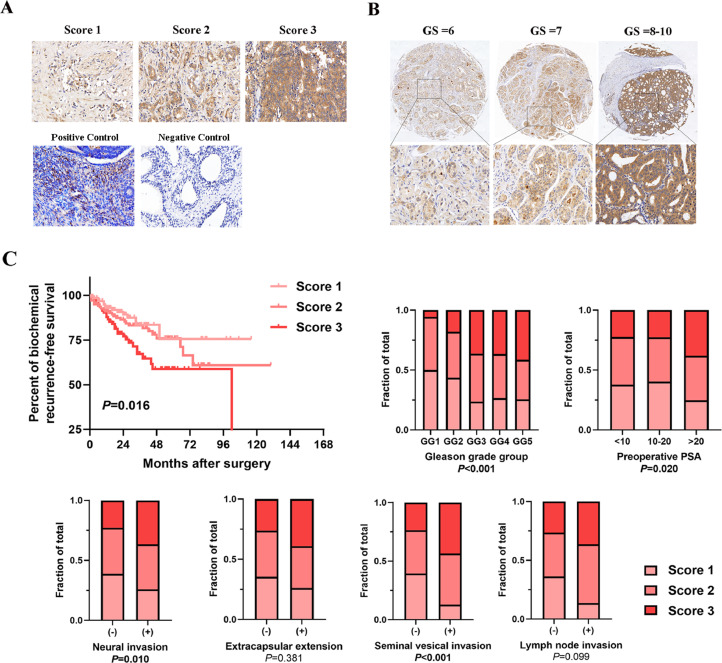

CCL20 indicated worse prognosis in PCa patients

We collected 362 PCa patients that accepted prostatectomy in our urological department, the patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table S2. To explore whether CCL20 can become a biomarker for predicting prognosis in PCa patients, we performed IHC analysis for detecting CCL20 in prostate sections, and found CCL20 staining was gradually more intense in patients with higher Gleason score (Fig. 6A, B). Further analysis revealed that the CCL20 staining score was positively correlated with Gleason grade, pre-operative PSA, neural invasion, seminal vesical invasion, and was negatively correlated with post-operative biochemical recurrence-free survival (Fig. 6C). We also examined the expression of CCR6, the receptor of CCL20 in prostate sections, and found the staining of CCR6 was equally more intense in patients with higher Gleason score (Fig. S2A, B), and was positively associated with the staining of CCL20 (Fig. S2C).

Fig. 6.

CCL20 indicated poor prognosis in PCa patients. A, Representative of CCL20 IHC staining score in PCa patients samples. B, Representative images of CCL20 staining in PCa patients with different Gleason score (×5 in the top images; ×40 in the bottom images). C, Correlation between CCL20 staining score and clinical parameters in a large cohort of 362 PCa patients.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that FMT with CRPC patients’ fecal suspension or SCFAs supplementation are capable of promoting TRAMP mice's PCa progression from LGPIN to WD-Adeno or PD-Adeno. In vitro study further proved that SCFAs could promote PCa cells migration and invasion by inducing cancer cell autophagy and M2 type macrophage polarization. These findings suggest that intervention of gut microbiota dysbiosis -derived SCFAs could be a beneficial strategy in PCa treatment.

In our previous studies, we reported increased abundance of gut Ruminococcus and Alistipes in CRPC patients [3,4]. Here, FMT with CRPC patients’ fecal suspensions also increased the levels of gut Ruminococcus and Alistipes in mice, along with Bacteroidales, Rikenellaceae, Faecalibacterium, the so-called SCFAs-producing microbiotas. SCFAs are the main products of bacterial fermentation of fibers in the colon. They can be transported from intestinal lumen into blood and taken up by distant organs where they activate signal pathways to regulate epigenetics and immune processes [31]. Famous known as inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACs), most studies described SCFAs as a protector in diseases [32,33], but there is no consensus about the role of SCFAs because they are cell-specific and dose-dependent. Here, we showed that SCFAs supplementation was able to facilitate TRAMP mice's PCa progression. And a lower dose of 0.2 mM SCFAs mixture in vitro was able to enhance PCa cells migration and invasion. These results coordinate with Makoto's study in which they found gut microbiota-derived SCFAs under high fat diet could promote PCa growth via IGF1 signalings [9].

Innate immune system is the first line of defense against harmful pathogens. It employs pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLRs to help adaptive immune system to establish a robust immune response. There are 10 TLRs in human and 13 TLRs in mice [34]. TLRs in TME are widely expressed, not only on immune cells like macrophages, dendritic cells, B/T lymphocytes, but also on fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and cancer cells. Although both anti-tumor and pro-tumor roles of TLRs have been reported, they have gradually been recognized as promotors in tumorigenesis and metastasis [35,36]. TLRs can sense a variety of ligands, we found SCFAs upregulated the expression of a majority of TLRs family, and TLR3-triggered autophagy promoted PCa cells migration and invasion. TLR3 locates mainly in endosomes, it senses dsRNA as its major ligand [37]. In our study, TLR3 perceived SCFAs to induce PCa cells autophagy, and activate survival signalings like NF-κB and MAPK. Some studies claimed that TLR3 is beneficial because it causes apoptosis in different in vitro tumor models. For instance, Gambara et al. have shown that stimulation of TLR3 with poly I:C cascaded interferon regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3) signaling to cause apoptosis in LNCaP cell [38]. But despite that effect, a contrary role of TLR3 in tumor progression and invasion has also been proposed. Transcriptomic analysis of TLR3-overexpressing PCa cell lines revealed enriched genes that are involved in regulation of cell migration and tumor invasion [39]. In parallel, Schulz and González-Reyes proved that high expression of TLR3 may lead to PCa biochemical recurrence [40,41]. Moreover, recent studies have realized that TLR3 expression and activation in tumors are related to therapy resistance [42]. Chuang et al. showed that TLR3high OC2 cells had greater cisplatin resistance, knockdown of TLR3 gene could enhance the cytotoxicity of cisplatin by attenuating the expression of IFNβ and CCL5 [43].

Autophagy induced PCa cell-derived CCL20 recruited more macrophages and polarized them into M2 type. CCL20, also known as macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3α, belongs to CC chemokine family. And CCR6 is CCL20’s specific receptor. Numerous studies have proved the positive role of CCL20-CCR6 axis in cancer progression, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, kidney cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and liver cancer [44], [45], [46]. CCL20 can both directly enhance the invasion of cancer cells, and indirectly reprogram the TME by acting on immune cells [47]. In our study, autophagy of PCa cells released the production of CCL20, and the latter induced M2 type macrophage polarization which in turn further enhanced PCa cells invasiveness. These results were in line with the increased number of macrophages, especially M2 type, in prostate of mice treated with CRPC FMT. We also marked a close relationship between CCL20 expression and poor clinical prognosis in a large cohort of PCa patients. Meanwhile, the expression of CCR6 was also increased in patients with higher Gleason score, and was positively associated with the expression of CCL20.

However, our study is not devoid of limitation. We could not determine whether the mice fecal microbiotas that we tested after FMT were stable colonizers or merely passing through the GI tract. Further study should be performed to examine the microbiotas in GI tract such as the intestine, so as to figure out which microbiotas were stably colonized. In summary, our in vivo and in vitro data demonstrated that FMT with CRPC patients’ fecal suspension increased SCFAs-producing microbiotas in TRAMP mice, and microbiota-derived SCFAs promoted PCa cells migration and invasion by triggering cancer cell autophagy through TLR3-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signalings. Moreover, cancer cell autophagy-derived chemokine CCL20 recruited more macrophages into TME and simultaneously polarized them into M2 type, which further enhanced PCa cells invasiveness. Our study suggested that intervention of SCFAs-producing microbiotas may be a useful strategy in the manipulation of CRPC.

Availability of data and materials

Data relating to the RNA sequencing have been uploaded to the Sequence Read Archive database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and are available for download via accession number PRJNA880995, PRJNA881393, and PRJNA881399. Other datasets are available from the corresponding author by request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yufei Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Quan Zhou: Validation. Fangdie Ye: Data curation, Visualization. Chen Yang: Resources, Data curation. Haowen Jiang: Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Zhou ZW from Pathology Department Huashan Hospital for assistance in prostate histopathology diagnosis.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant number: 81872102.

Ethics approval and consent form

All the experimental protocols were approved by Institutional Review Board of Huashan Hospital Fudan University (Grant No.2020-531)/(Grant No. 2020-JS252). All human participants have signed the consent form.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2023.100928.

Contributor Information

Yufei Liu, Email: lyf20150818@163.com.

Haowen Jiang, Email: urology_hs@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Thaiss C.A., Zmora N., Levy M., et al. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 2016;535(7610):65–74. doi: 10.1038/nature18847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belkaid Y., Harrison OJ. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46(4):562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y., Jiang H. Compositional differences of gut microbiome in matched hormone-sensitive and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Trans. Androl. Urol. 2020;9(5):1937–1944. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y., Yang C., Zhang Z., et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis accelerates prostate cancer progression through increased LPCAT1 expression and enhanced DNA repair pathways. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.679712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erny D., Dokalis N., Mezö C., et al. Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell Metab. 2021;33(11):2260–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.10.010. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosser E.C., Piper C.J.M., Matei D.E., et al. Microbiota-derived metabolites suppress arthritis by amplifying aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation in regulatory B cells. Cell Metab. 2020;31(4):837–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.03.003. e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirzaei R., Afaghi A., Babakhani S., et al. Role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in cancer development and prevention. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;139 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belcheva A., Irrazabal T., Robertson S.J., et al. Gut microbial metabolism drives transformation of MSH2-deficient colon epithelial cells. Cell. 2014;158(2):288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsushita M., Fujita K., Hayashi T., et al. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote prostate cancer growth via IGF1 signaling. Cancer Res. 2021;81(15):4014–4026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., He S., Ma B. Autophagy and autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang Y.J., Kim J.H. Modulation of autophagy for controlling immunity. Cells. 2019;8(2):138. doi: 10.3390/cells8020138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang G.M., Tan Y., Wang H., et al. The relationship between autophagy and the immune system and its applications for tumor immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0944-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeNardo D.G., Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19(6):369–382. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan S., Wan G. Tumor-associated macrophages in immunotherapy. FEBS J. 2021;288(21):6174–6186. doi: 10.1111/febs.15726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald K.A., Kagan J.C. Toll-like receptors and the control of immunity. Cell. 2020;180(6):1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakoff-Nahoum S., Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mokhtari Y., Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi A., et al. Toll-like receptors (TLRs): an old family of immune receptors with a new face in cancer pathogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021;25(2):639–651. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhan Z., Xie X., Cao H., et al. Autophagy facilitates TLR4- and TLR3-triggered migration and invasion of lung cancer cells through the promotion of TRAF6 ubiquitination. Autophagy. 2014;10(2):257–268. doi: 10.4161/auto.27162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mottet N., van den Bergh R.C.N., Briers E., et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 2021;79(2):243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith P.M., Howitt M.R., Panikov N., et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic T reg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y., Wu X., Jiang H. Combined maternal and post-weaning high fat diet inhibits male offspring's prostate cancer tumorigenesis in transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Prostate. 2019;79(5):544–553. doi: 10.1002/pros.23760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu Y.L., Chen C.C., Lin Y.T., et al. Evaluation and optimization of sample handling methods for quantification of short-chain fatty acids in human fecal samples by GC-MS. J. Proteome Res. 2019;18(5):1948–1957. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman-Booty L.D., Sargeant A.M., Rosol T.J., et al. A review of the existing grading schemes and a proposal for a modified grading scheme for prostatic lesions in TRAMP mice. Toxicol. Pathol. 2012;40(1):5–17. doi: 10.1177/0192623311425062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klionsky D.J., Abdalla F.C., Abeliovich H., et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C., Liu H., Yang M., et al. RNA-Seq based transcriptome analysis of endothelial differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020;59(5):834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q., Tong D., Liu G., et al. Metformin inhibits prostate cancer progression by targeting tumor-associated inflammatory infiltration. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24(22):5622–5634. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y., Zhang Y., Wei K., et al. Review: effect of gut microbiota and its metabolite SCFAs on radiation-induced intestinal injury. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.577236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsushita M., Fujita K., Motooka D., et al. The gut microbiota associated with high-Gleason prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(8):3125–3135. doi: 10.1111/cas.14998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muresan X.M., Bouchal J., Culig Z., et al. Toll-like receptor 3 in solid cancer and therapy resistance. Cancers. 2020;12(11):3227. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113227. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolasia K., Bisht M.K., Pradhan G., et al. TLRs/NLRs: Shaping the landscape of host immunity. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2018;37(1):3–19. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2017.1397656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.den Besten G., van Eunen K., Groen A.K., et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachem A., Makhlouf C., Binger K.J., et al. Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote the memory potential of antigen-activated CD8 + T cells. Immunity. 2019;51(2):285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.002. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBrearty N., Arzumanyan A., Bichenkov E., et al. Short chain fatty acids delay the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBx transgenic mice. Neoplasia. 2021;23(5):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2021.04.004. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Nardo D. Toll-like receptors: activation, signalling and transcriptional modulation. Cytokine. 2015;74(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tongtawee T., Simawaranon T., Wattanawongdon W., et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 polymorphisms associated with Helicobacter pylori susceptibility and gastric cancer. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2019;30(1):15–20. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.17461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melssen M.M., Petroni G.R., Chianese-Bullock K.A., et al. A multipeptide vaccine plus toll-like receptor agonists LPS or polyICLC in combination with incomplete Freund's adjuvant in melanoma patients. J. Immuno Cancer. 2019;7(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0625-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blasius A.L., Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32(3):305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gambara G., Desideri M., Stoppacciaro A., et al. TLR3 engagement induces IRF-3-dependent apoptosis in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells and inhibits tumour growth in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015;19(2):327–339. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muresan X.M., Slabáková E., Procházková J., et al. Toll-like receptor 3 overexpression induces invasion of prostate cancer cells, whereas its activation triggers apoptosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2022;192(9):1321–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2022.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González-Reyes S., Fernández J.M., González L.O., et al. Study of TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 in prostate carcinomas and their association with biochemical recurrence. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2011;60(2):217–226. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0931-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz W.A., Alexa A., Jung V., et al. Factor interaction analysis for chromosome 8 and DNA methylation alterations highlights innate immune response suppression and cytoskeletal changes in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2007;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-14. Feb 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jia D., Yang W., Li L., et al. β-Catenin and NF-κB co-activation triggered by TLR3 stimulation facilitates stem cell-like phenotypes in breast cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(2):298–310. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chuang H.C., Chou M.H., Chien C.Y., et al. Triggering TLR3 pathway promotes tumor growth and cisplatin resistance in head and neck cancer cells. Oral Oncol. 2018;86:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu C., Fan L., Lin Y., et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through miR-1322/CCL20 axis and M2 polarization. Gut Microbes. 2021;13(1) doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1980347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadomoto S., Izumi K., Mizokami A. The CCL20-CCR6 axis in cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(15):5186. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155186. Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu W., Wang W., Wang X., et al. Cisplatin-stimulated macrophages promote ovarian cancer migration via the CCL20-CCR6 axis. Cancer Lett. 2020;472:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen W., Qin Y., Liu S. CCL20 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1231:53–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36667-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data relating to the RNA sequencing have been uploaded to the Sequence Read Archive database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) and are available for download via accession number PRJNA880995, PRJNA881393, and PRJNA881399. Other datasets are available from the corresponding author by request.