Abstract

Background

Soil metagenomics is a cultivation-independent molecular strategy for investigating and exploiting the diversity of soil microbial communities. Soil microbial diversity is essential because it is critical to sustaining soil health for agricultural productivity and protection against harmful organisms. This study aimed to perform a metagenomic analysis of the soybean endosphere (all microbial communities found in plant leaves) to reveal signatures of microbes for health and disease.

Results

The dataset is based on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) release “microbial diversity in soybean”. The quality control process rejected 21 of the evaluated sequences (0.03% of the total sequences). Dereplication determined that 68,994 sequences were artificial duplicate readings, and removed them from consideration. Ribosomal Ribonucleic acid (RNA) genes were present in 72,747 sequences that successfully passed quality control (QC). Finally, we found that hierarchical classification for taxonomic assignment was conducted using MG-RAST, and the considered dataset of the metagenome domain of bacteria (99.68%) dominated the other groups. In Eukaryotes (0.31%) and unclassified sequence 2 (0.00%) in the taxonomic classification of bacteria in the genus group, Streptomyces, Chryseobacterium, Ppaenibacillus, Bacillus, and Mitsuaria were found. We also found some biological pathways, such as CMP-KDO biosynthesis II (from D-arabinose 5-phosphate), tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle (plant), citrate cycle (TCA cycle), fatty acid biosynthesis, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. Gene prediction uncovered 1,180 sequences, 15,172 of which included gene products, with the shortest sequence being 131 bases and maximum length 3829 base pairs. The gene list was additionally annotated using Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes. The annotation process yielded a total of 240 genes found in 177 bacterial strains. These gene products were found in the genome of strain 7598. Large volumes of data are generated using modern sequencing technology to sample all genes in all species present in a given complex sample.

Conclusions

These data revealed that it is a rich source of potential biomarkers for soybean plants. The results of this study will help us to understand the role of the endosphere microbiome in plant health and identify the microbial signatures of health and disease. The MG-RAST is a public resource for the automated phylogenetic and functional study of metagenomes. This is a powerful tool for investigating the diversity and function of microbial communities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s43141-023-00535-4.

Keywords: Metagenomics, Endospheric mg-rast, Omicbox, Taxonomy, Function

Background

Soybean, Glycine max (L.) Merrill is an annual, self-pollinated diploid legume (subfamily Fabaceae). Soybeans have been grown as a commercial crop, mainly in temperate ecologies, for thousands of years. One of the most widely cultivated legumes, soybeans, came initially from East Asia, but can now be found everywhere [1]. The United States has grown soybeans over the most significant areas. It accounts for approximately 32% of the world's soybean production, followed by Brazil (31%), Argentina (19%), China (6%), and India (4%) [2]. Madhya Pradesh has the highest soybean production in any other state. Soybeans have been cultivated in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh during the last two years over an area of around 4.4 million hectares (ha), with a total yield of approximately 3.9 million tonnes and average productivity of 796–885 kg/ha [3]. The conditions under which soybeans were grown were similar to those of maize. In addition to being used to make oil, crayons, and other products, soybeans are also used for a variety of other uses. Its output is almost identical to that of maize [4]. The microbial population living in the roots of soybean plants is diverse and mostly composed of bacteria and fungi [5]. Interactions between the plant host and its microbial communities determine microbiome diversity and taxonomy, and assist critical plant activities, such as nutrient absorption and tolerance to biotic and abiotic changes [6]. Plant microbiomes may include both beneficial and harmful bacteria. Microbes inhabit the root rhizosphere and endosphere, which are composed of the outermost tissue layers of the root identified via research on experimental model plants and crops [7]. The microbial communities that are isolated from the various root compartments each have unique taxonomic structures and functional compositions [8, 9], highlighting the significance of the intricate connections between various bacterial and fungal communities and the role that these communities play in the formation of the microbiome [10]. The Microbiomes of many plant species support plant defense against pathogens and environmental stress through mechanisms such as hormone induction, nutrient absorption, and transport [11]. There has been a meteoric rise in the number of studies conducted in recent years with the objective of describing the human microbiome (the environment, including the microbiota, any proteins or metabolites they make, their metagenome, and host proteins and metabolites in this environment) in both healthy and diseased conditions. The field of microbiology has undergone a paradigm shift in the last 30 years, which has caused a change not only in our perspective on microorganisms, but also in the techniques that are used to investigate them. This has led to significant development [12]. In the early part of the twentieth century, there was a widespread belief that microbes would not exist if they could not be cultivated in a laboratory [13]. Metagenomics was first noted by [14], which encompassed information on the entire microbial community composition and function, widening the area of genomics where only genetic material is studied. A few prior studies, such as [15], on phylogenetic analyses of environmental microbial communities have also been reported [16]. In the process of metagenomics study, genomic DNA from all organisms in a community (metagenome) was extracted for fragmentation, cloning, transformation, and subsequent screening of the constructed metagenomic library. Initially, the primary target of metagenomics was limited to screening environmental communities for a specific biological activity and to identifying the related genomics [17, 18]. Although it is considered to have a significant impact in determining the outcome of metagenome analysis, it circumvents the uncolorability and genomic diversity of most microbes, the biggest roadblocks to advances in microbiology that are not properly cultured in the laboratory and identification. Knowledge gaps in understanding unculturable microorganisms and functional and taxonomic analyses are fundamental limitations [19]. Metagenomics studies can be tackled using the targeted metagenomics approach and shotgun metagenomics approach with fundamental differences based on methodology and objectives. In targeted metagenomics, a gene or a few genes are sequenced and used primarily to carry out phylogenetic studies, whereas in shotgun metagenomics, all the present DNA is sequenced and used in functional gene analysis assays (Morgan et al. 2013). This process usually involves next-generation sequencing (NGS) after DNA is extracted from the samples. This resulted in a large amount of data in the form of short reads.

In this study, we investigated the microbes present in the soybean endosphere and identified their taxonomy, function, and genes. The endosphere microbiome of soybean plants is composed of a wide variety of bacteria and fungi, which play an important role in plant health. Beneficial microbes can improve plant nutrition by increasing the availability of nutrients to plants. They can also protect plants from disease by competing with pathogens for space and nutrients, and by producing antibiotics. In addition, beneficial microbes can help plants tolerate stress by producing enzymes that detoxify the stress hormones. In this process, each piece of DNA is assigned to a particular taxonomic group, such as species, genus, or family. There are many different methods that can be used for taxonomic classification, but one of the most common is called “taxonomic hits distribution”. In the taxonomic hit distribution, the sequenced DNA was compared with a reference database of known DNA sequences. This reference database can either be a collection of known genomes or a collection of known genes. The reference database was searched for the best match to each piece of DNA in the sample, and then the taxonomic group of the reference sequence was assigned to the piece of DNA in the sample.

Method

Dataset acquired and processing

The SRR10740534 dataset has been retrived from the NCBI SRA and is based on the paper “microbial diversity in soybean”. Fastq-dump SRA toolkit software was used to convert the data file from the Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) to FASTQ format. Most sequencers produce sequence files in FASTQ format, which is a standard. This is similar to the FASTA format, where Q represents the quality [17]. Along with the sequence, it is recommended that the FASTQ file contain the sequence and quality of the sequence bases. The primary detail of the dataset is given in Table 1, and the basic statistics of the considered dataset is given in Table 2 below.

Table 1.

Primary detail of the dataset

| Item | Platform | Read Count | Base Count | Library Layout | Library Strategy | Library Source | Library Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRR10740534 | Illumina | 80,889 | 44,414,941 | Paired | AMPLICON | metagenomic | PCR |

Table 2.

Analysis Statistics detail of the dataset

| Upload: bp Count | 33,439,021 bp |

| Upload: Sequences Count | 72,868 |

| Upload: Mean Sequence Length | 459 ± 18 bp |

| Upload: Mean guanine-cytosine (GC) percent | 55 ± 3% |

| Artificial Duplicate Reads: Sequence Count | 68,994 |

| Post QC: bp Count | 1,739,799 bp |

| Post QC: Sequences Count | 3,853 |

| Post QC: Mean Sequence Length | 452 ± 39 bp |

| Post QC: Mean GC percent | 55 ± 4% |

| Processed: Predicted Protein Features | 5 |

| Processed: Predicted rRNA Features | 3,507 |

| Alignment: Identified Protein Features | 0 |

| Alignment: Identified rRNA Features | 3,507 |

| Annotation: Identified functional Categories | undefined |

MG-Rast-server

We utilized MG-RAST (version 4.0.3) to control quality, predict proteins, and organize and annotate nucleic acid sequence databases. MG-RAST compares the predicted proteins to database proteins (for shotgun) and compares the 16S and 18S sequences to reads. MG-RAST allows access to phylogenetic and metabolic reconstructions [20, 21].

Data processing

We selected the following pipeline for data processing.

Assembled: If the file contains assembly data, we choose the assembled input sequence option and include coverage information within each sequence header.

Dereplication: This process includes removing artificially replicated sequences that are artificially processed.

Screening- There is a filter for hot species in screening, and then we select the specific species. It removes any host species sequence, for example, plant, human, mouse, and others, with the help of DNA-level matching with a bowtie [22].

Dynamic trimming: This method removes low-quality sequences using dynamic cutting.

Omics Box tools

Omics Box is bioinformatics software that converts readings into insights. For each collection of sequences, these tools enable the identification of pathways, function analysis, gene prediction, and other functions from multiple databases [23]. The OmicsBox tools were used to predict gene function, pathway, and gene modules.

IMG/M

IMG/M is an integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system that allows open access interactive analysis of publicly available datasets, whereas manual curation, submission, and access to private datasets and computationally intensive workspace-based analysis require login/password access to its expert review (ER) companion system (IMG/MER) [24]. The core data model underlying IMG allows recording the primary sequence information and its organization in scaffolds and/or contigs [25]. Metagenome bins can be stored in IMG as individual workspace scaffold datasets, and analyzed using many tools, such as function profiles [24]. The new Scaffold Search under the Find Genomes menu provides two search modes: Quick Search allows querying of scaffolds in IMG using scaffold IDs, while Advanced Search allows querying of scaffolds using various metadata attributes [26].

Result and discussion

Sequencing quality analysis

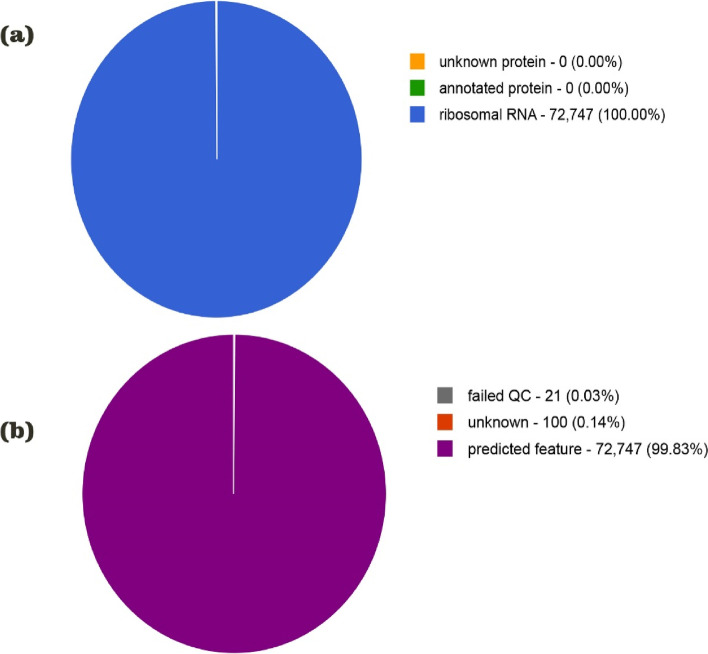

To process the metagenome data analysis, dataset quality analysis was performed using the FastQC program. The FastQC program provides a QC report on spot problems that originate either in the sequencer or in the starting library material. Many modules were used to evaluate the raw data, and an HTML report with a module summary was created. The pre-alignment steps are specified in the quality control report. Run the FastQC summary report and compare the read format information with the overall poor quality to filter out and cut low-quality sequence parts while maintaining high-quality sequences. The dataset contained 72,868 sequences, totalling 203,552,249 base pairs (bp) with an average length of 378 ± 77 bp. The quality control process rejected 21 of the evaluated sequences (0.03% of the total), as shown in Fig. 1. Dereplication determined that 68,994 sequences were artificial duplicate readings, and removed them from consideration. Ribosomal RNA genes were present in each of the 72,747 sequences that successfully passed the QC. In Fig. 1(a, b), the feature breakdown and function of the QC are shown.

Fig. 1.

QC result of Sequences a Sequence Breakdown b Predicted Features

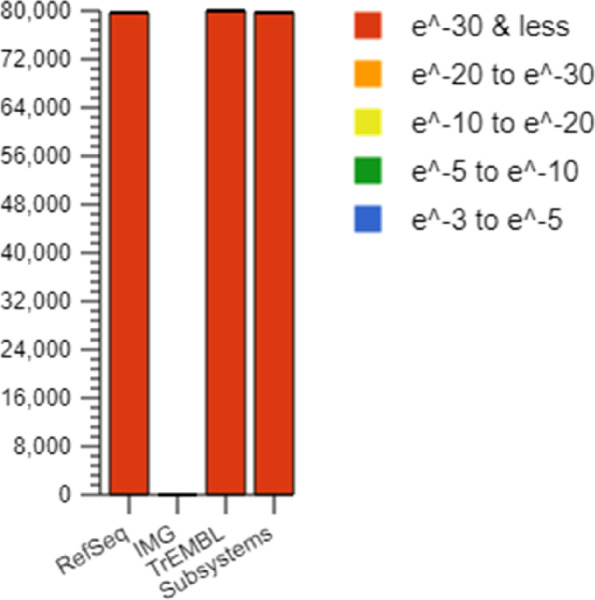

Source hits distribution

The biological interpretation of the source hit distribution is essential for providing information on how many sequences per dataset were found for each database. The source hists distribution has been investigated, we have found 16 hit databases including protein databases, protein databases with functional hierarchy information, and ribosomal RNA databases with maximum in RefSeq [27], TrEMBL [28], and Subsystems shown in Fig. 2. In the figure, the bars representing annotated reads are colored based on the e-value range. It is important to note that different databases may have varying numbers of hits and can also provide different types of annotation data.

Fig. 2.

Source hit distribution of studied data set

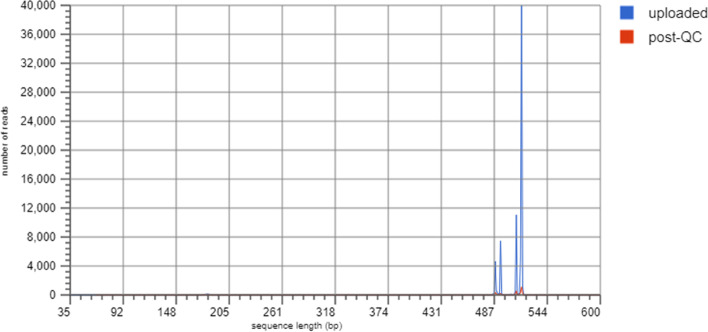

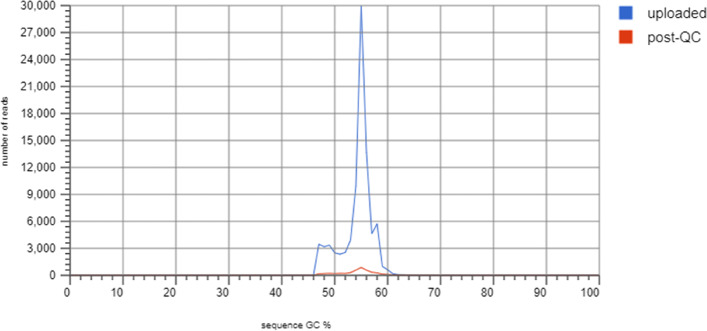

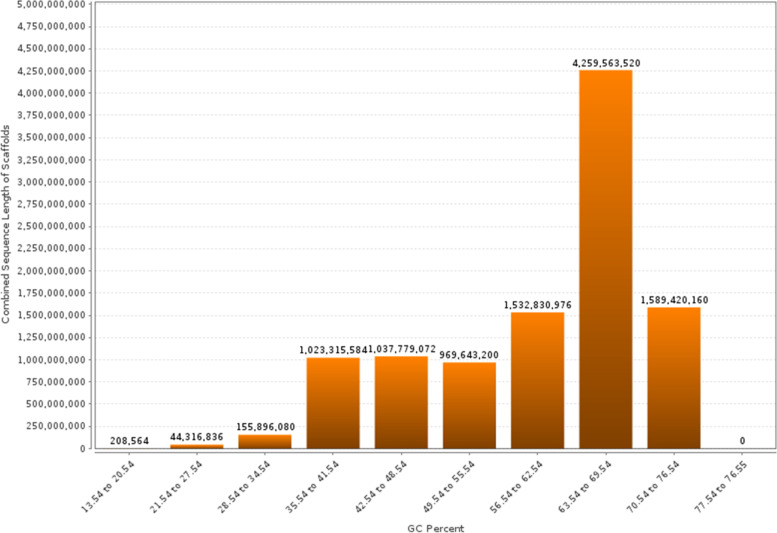

Sequence GC distribution

The Sequence GC Distribution was evaluated as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. Histograms depict the sequence lengths in bp for this metagenome. Each position represents the number of base pairs (bp). The charts used raw upload and post-QC data.

Fig. 3.

Sequence Length Histogram

Fig. 4.

Sequence GC Distribution

In Sequence GC Distribution analysis, Guanine and Cytosine-rich areas were identified to predict the annealing temperature. Figure 4 shows the GC % distribution in the metagenome. Each location indicates the range of the GC %. The plots used raw uploaded and post-QC data.

Taxonomic analysis

Taxonomic hits distribution

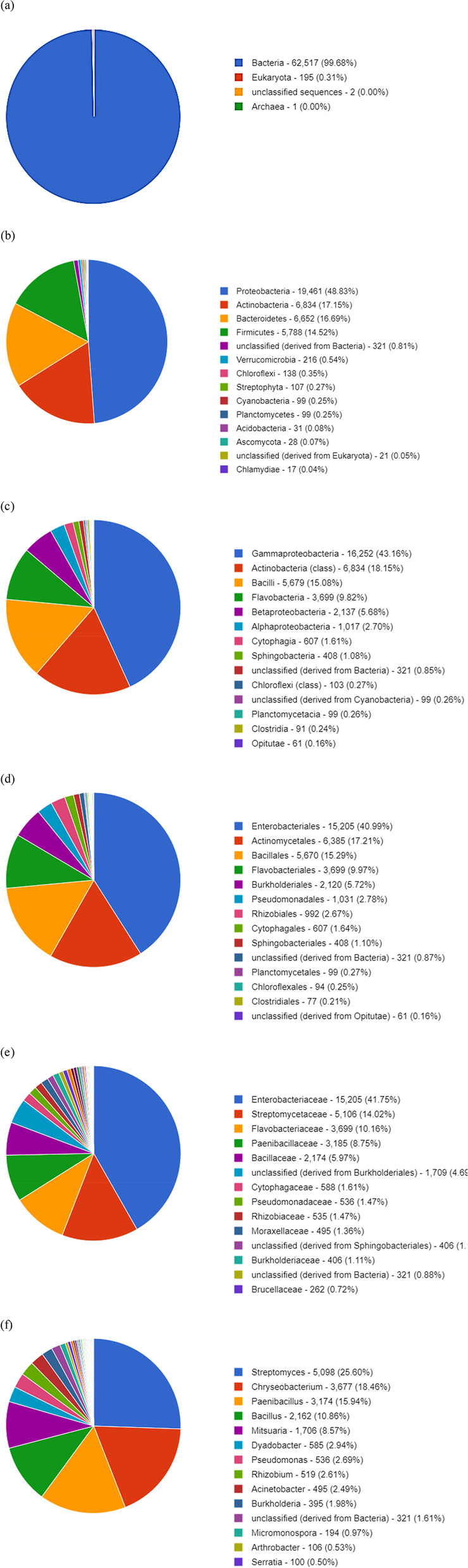

When conducting a metagenomic study, one of the key parameters that is often considered is taxonomic hit distribution. This provides insights into the species present in a given sample and their relative abundance. Taxonomic hit distribution can provide insights into the species present in a given sample and their relative abundance. This information can be used to help understand the ecology of a sample and can be used to help guide future studies. Hierarchical classification for taxonomic assignment was conducted using MG-RAST, and the considered dataset of the metagenome domain of Bacteria (99.68%) dominated other groups of eukaryotes (0.31%) and unclassified sequence 2(0.00%). The charts below represent the distribution of taxa using a contig LCA algorithm, finding a single consensus taxonomic entity for all features on each individual sequence. Similarly, Proteobacteria dominated over Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes. In terms of bacterial taxonomy, the richest classes, orders, families, and genus are as follows Streptomyces (25.60%), Chryseobacterium (18.46%), Paenibacillus (15.94%), Bacillus (10.86%), Mitsuaria (8.57%), Dyadobacter (2.94%), Pseudomonas (2.69%), Rhizobium, (2.61%) Acinetobacter (2.49%), Burkholderia, (1.98%) unclassified (derived from Bacteria)- (1.6), Micromonospora (0.97%), Arthrobacter (0.53%), Serratia—(0.50%) These percentages indicate the prevalence of each taxonomic entity, as depicted in Fig. 5(a-f). The distribution of taxa was determined using a contigLCA algorithm, which assigned a single consensus taxonomic classification to all features found in each individual sequence. Within the realm of bacterial taxonomy, the genus Streptomyces stands out by claiming a substantial portion, approximately 25.60%, of its corresponding taxonomic category. Notably, this genus exhibits remarkable capabilities as it produces antibiotics with efficacy against a wide range of biological adversaries, including fungi, bacteria, and parasites [29]. Streptomyces has harnessed its capabilities to develop immunosuppressants and biocontrol agents specifically designed for agricultural purposes. These antibiotics exhibit the power to regulate and combat fungi and parasites, effectively safeguarding crops like soybeans from potential damage caused by these microorganisms. Moreover, Streptomyces demonstrates its prowess by suppressing or eradicating microbial adversaries, while simultaneously stimulating plant growth in various agricultural settings. This remarkable phenomenon has been observed across multiple crop types, leading to significant improvements in soybean crop production. Furthermore, the presence of Streptomyces contributes to the overall promotion and enhancement of soybean crop growth [30]. Among the recorded sequences, it was determined that the genus Corynebacterium held the second-highest percentage, amounting to approximately 18.46%. The majority of Gram-positive bacteria falling under this classification exhibit the ability to thrive and persist in oxygen-rich environments. Corynebacterium species are ubiquitous, inhabiting the soil layers on the skin of mammals. According to the genetic characteristics, examination of the Corynebacterium genome revealed both harmful and non-pathogenic species [31]. Within the genus, Paenibacillus emerges as the third prominent species, accounting for a substantial percentage of approximately 15.94%. This particular species comprises a multitude of sequences that play a pivotal role in facilitating the growth and development of soybean crops [32]. Paenibacillus species that establish a symbiotic relationship with plants possess the remarkable ability to produce auxin phytohormones, which exert a profound influence on plant development. In addition to this, these species facilitate the uptake of phosphorus by plant roots and some of them even engage in atmospheric nitrogen fixation, thereby providing substantial benefits to soybean plants. Furthermore, Paenibacillus plays a crucial role in suppressing phytopathogens through the production of biocides that contribute to systemic resistance [33]. Bacillus emerges as the third prominent species, accounting for a substantial percentage of approximately 10.86%, Bacillus species are predominately found in food and have both beneficial and harmful effects on human health. This is because these microbes produce bioactive substances during fermentation. Consequently, eating food made from soybeans fermented by Bacillus ensures food safety [34]. Additionally, Bacillus helps the seedlings of soybean plants to become more resistant to infection. Bacillus species possess a wide variety of advantageous tracts. Plants benefit from this process because they can obtain nutrients. Increased synthesis of phytohormones leads to better overall growth and increased resistance to both biotic and abiotic stressors [34]. There are numerous varieties of bacteria found in this genus, which may be advantageous and helpful for soybean plant development and metabolic activity, and some aid as a biofertilizer and biotic and abiotic stress, and have a major function in soybean crops. Within the context of soybean plants, the genus Mitsuaria assumes a noteworthy position. It is worth mentioning that the sequences affiliated with Mitsuaria constitute the fourth largest segment, amounting to approximately 8.57% sequence. Mitsuaria isolates have been observed to inhibit fungal and oomycete plant pathogens in laboratory and in vivo experiments on soybean seedlings, leading to a reduction in disease severity. This study indicates the effectiveness of T-RFLP-derived markers for identifying microorganisms with pathogen-inhibiting properties [35]. The metagenomic sequences reveal that several genera, including Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Burkholderia, and Mesorhizobium, co-exist in the rhizosphere and nodules of soybean plants [36]. Additionally, endophytic bacteria, including Burkholderia, Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, and Dyadobacter, have been identified as beneficial for plant growth and development. Some studies have also investigated the effects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on soybean growth and soil bacterial community composition. For example, Paenibacillus mucilaginosus, a PGPR strain, improved symbiotic nodulation, soybean growth parameters, nutrient contents, and yields in a field experiment [37]. The certain genus Acinetobacter, Micromonospora, and Serratia species in the soybean metagenome promote plant growth through nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, phytohormone synthesis, and enhanced tolerance to salinity. Their presence and activities contribute to the overall growth and development of soybean plants.

Fig. 5.

We present taxa using contig LCA to determine a single consensus taxonomic item for each sequence feature. A domain B Phylum C Class D Order E Family F Genus

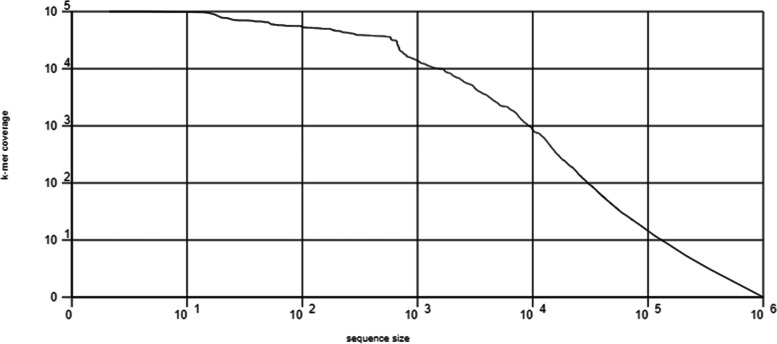

Rank abundance plot

To graphically depict taxonomic richness and evenness, Rank Abundance plots were arranged the taxonomic abundances in descending order from their most abundant to their least abundant values. In most cases, only the top 50 most prevalent cases are presented. On a logarithmic scale, the abundance of annotations is shown along the y axis. The most abundant sequences on the left are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

kmer rank abundance graph plots the kmer coverage as a function of abundance rank

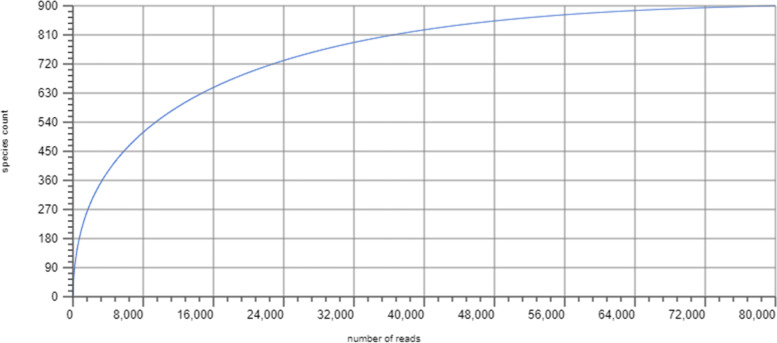

Rarefaction curve

The rarefaction curve shows the total number of different species annotations as a function of the number of sampled sequences. This curve indicates the richness of the annotated species (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Rarefaction Curve showing the richness of the annotated species

Scaffold analysis from the genome sequence

A scaffold is a reconstructed genomic sequence from whole-genome shotgun clones, consisting of contigs and gaps. It is created by chaining contigs together and separating them by gaps. Whole-genome shotgun assembly aims to represent each genomic sequence in one scaffold, but it is not possible. Scaffolding improves the contiguity and quality of metagenomic bins by assembling short metagenomic reads into longer contiguous sequences based on sequence overlap. The distribution of scaffolds by gene count provided valuable insights into the prevalence and distribution patterns of genes within the metagenomic dataset. The analysis revealed varying numbers of scaffolds within specific gene count ranges, indicating varying levels of gene abundance and representation. The histogram tab in Scaffold Cart displays a histogram with the counts of protein-coding genes in the sample. Analysis of gene count distribution within metagenomic datasets plays a fundamental role in unraveling the complexity and functional diversity of microbial communities. In this study, the distribution of scaffolds by gene count was thoroughly examined, providing valuable insights into the prevalence and distribution of genes across a metagenomic dataset. The results demonstrated a comprehensive breakdown of scaffolds falling within specific gene count ranges, ranging from 1 to 12,972, as shown in Fig. 8. This detailed breakdown enabled a deeper understanding of the distribution patterns and relative abundance of genes within the metagenomic dataset. By elucidating the number of scaffolds within each gene count range, this analysis sheds light on the genetic composition and functional potential of microbial communities, thereby contributing to our knowledge of the intricate dynamics of these complex ecosystems. In this study, we identified 6,568 scaffolds, with gene counts ranging from 1 to 1,299. Of these, 515 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 1,300 to 2,597; 613 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 2,598 to 3,895; 577 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 3,896 to 5,193; 362 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 5,194 to 6,491; 172 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 6,492 to 7,789; 105 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 7,790 to 9,087; 69 scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 9,088 to 10,385; eight scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 10,386 to 11,683; and seven scaffolds had gene counts ranging from 11,684 to 12,972. The distribution of gene counts across scaffolds was nonuniform, with a higher proportion of scaffolds having fewer genes. This suggests that the genome is composed of a large number of small genes and a smaller number of larger genes. The distribution of gene counts may also be influenced by the assembly method used because different methods may have different biases in the number of genes that can be detected. The identification of scaffolds with different numbers of genes is important for understanding genome organization. Genes are often clustered together on scaffolds, and the number of genes on a scaffold can be used to infer their functions. For example, scaffolds with a large number of genes are often associated with metabolic pathways, whereas scaffolds with a small number of genes are often associated with regulatory functions. In addition to analyzing the gene count distribution, it is essential to examine other relevant parameters that provide further insights into the metagenomic dataset. This section focuses on the GC percentage, scaffold count, and combined sequence length. These parameters contribute to our understanding of the composition and structural characteristics of the datasets. Figure 9 presents the distribution of scaffolds based on their GC percentage range along with the corresponding scaffold count and combined sequence length. This analysis provided an overview of the dataset and presented the values for each GC percentage range. In the range of 13.54 to 20.54, there were 208,564 scaffolds with a combined sequence length of 208,564 base pairs. In the range of 21.54 to 27.54, we observed a significant increase in scaffold count, with 44,316,835 scaffolds and an equivalent combined sequence length. Similarly, the ranges of 28.54 to 34.54, 35.54 to 41.54, 42.54 to 48.54, 49.54 to 55.54, 56.54 to 62.54, 63.54 to 69.54, and 70.54 to 76.54 show varying scaffold counts and combined sequence lengths. These values provide valuable insights into the composition and characteristics of the metagenomic dataset, offering a quantitative representation of the genomic content within each GC percent range. This helps to unravel the dataset's characteristics, genomic diversity, and structural properties of the microbial communities under study.

Fig. 8.

Scaffold analysis. Scaffolds by Gene Count Histogram

Fig. 9.

Scaffold analysis. Scaffolds by GC Percent Histogram

Function analysis

OmicsBox is a bioinformatics software platform that enables researchers to go from raw data to meaningful insights within a couple of hours [23]. Functional studies of the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG), cellular activities and signalling, metabolism, and storage were carried out. The analysis was carried out on 827 sequences, each of which had an average length of 44.0 characters. Only 1.81% of the sequences had gene ontology (GO) annotations, leading to the discovery of 75 GO term annotations. Functional analysis of COG considers that, in the instance of Metabolic Processes, the predominant functions by sequence are amino acid translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, and replication, recombination, and repair. Metagenomic analysis of the fermented soybean product sikkam indicated that the sequence activities include translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, replication, recombination, and repair [38]. Mapping of metagenomic sequences against databases of orthologous gene groups revealed many enriched recombination and repair functional sequences.

Gene prediction

Gene prediction is an important tool in metagenomics and in the study of the genetic material of an entire ecosystem. By examining the genes of organisms in a sample, scientists can learn about the functions of these genes and the organisms themselves. There are several methods of gene prediction, but they all center on one basic process: looking for regions of the genome that are likely to encode proteins. Proteins are the building blocks of all living organisms; therefore, genes encoding proteins are often the most important. There are many different types of proteins, each with a specific function. Some proteins are involved in metabolism, whereas others are involved in cell structure regulation. Regardless of the function of the protein, gene prediction can help to identify the genes that encode it. By identifying these genes, scientists can learn about the function of the proteins and the organisms that produce them. Gene prediction uncovered 1,180 sequences, 15,172 of which included gene products, with the shortest sequence being 131 bases and maximum length 3829 base pairs. These gene products were found in the genome of strain 7598. The maximum genes were discovered in Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Paenibacillus, Klebsiella, Lactobacillus, Streptomyces, Bradyrhizobium, Bordetella, Cronobacter, Salmonella, Corynebacterium, Micromonospora, Cupriavidus, Akkermansia, Leuconostoc, Xanthomonas, Priestia, Ligilactobacillus, and Candidatus (Table S1). The gene list was additionally annotated using Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes. The annotation process yielded a total of 240 genes found in 177 bacterial strains, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

The gene list annotation using the metagenomic database

| Genome Name | Gene Symbol | Length (bp) | Genome Name | Gene Symbol | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 21831 | zupT | 792 | Marivirga tractuosa H-43, DSM 4126 | mutS2 | 2397 |

| Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Goettingen | yyaS | 606 | Frankia inefficax EuI1c | murA | 1260 |

| Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Goettingen | ywrA | 537 | Brevibacillus laterosporus NRS 682, LMG 15441 | mtrB | 240 |

| Bacillus licheniformis 9945A | ywnC | 393 | Desulfovibrio vulgaris vulgaris DP4 | mtnA | 1053 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa CICC 10580 | yvbA | 312 | Acidipropionibacterium acidipropionici F3E8 | msrA | 630 |

| Paenibacillus sp. lzh-N1 | yutG1 | 498 | Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac48 | msrA | 546 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac48 | yunB | 777 | Modestobacter marinus BC501 | mscS | 837 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac48 | yugT | 1683 | Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac84 | mrgA | 465 |

| Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Novozymes | yueI | 402 | Enterobacter cloacae A1137 | mreD | 489 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa M1 | ytvI3 | 1155 | Thioalkalivibrio paradoxus ARh 1 | mrcB | 2268 |

| Streptomyces sp. RJA2910 | ytnA | 1434 | Bradyrhizobium sp. BM-T | moaE | 468 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | yrrS | 693 | Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac84 | moaE | 495 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | yrhB | 1143 | Paenibacillus kribbensis AM49 | moaA1 | 1014 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa J | yqfU | 945 | Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514 | mnmE | 1383 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis MDJK30 | ypzA | 267 | Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 | mnmA | 1080 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | ylbO | 606 | Xanthomonas albilineans XaFL07-1 | mltD | 1212 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SQR-21 | ykkC3 | 342 | Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumoniae RJF293 | mioC | 441 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumoniae RJF293 | yjhQ | 552 | Priestia megaterium SF185 | minJ | 1191 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 | yjbR | 348 | Sphingopyxis sp. MG | mfeA | 903 |

| Bacillus licheniformis 9945A | yhzE | 87 | Nitrosospira multiformis Nl14 | mfd | 3468 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 | yfmM | 1581 | Halobacillus halophilus HL2HP6 | metN2 | 1053 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa J | yfiF5 | 786 | Corynebacterium terpenotabidum Y-11 Genome sequencing | metI | 702 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa J | yetL3 | 510 | Phaeobacter inhibens P88 | metF | 870 |

| Bacillus licheniformis 5NAP23 | yesE | 420 | Bacillus sp. FJAT-21351 | metB | 1146 |

| Lelliottia nimipressuralis SGAir0187 | yejK | 1008 | Ligilactobacillus acidipiscis ACA-DC 1533 | menB | 822 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Sb3-1 | yclD | 462 | Enterobacter cloacae A1137 | mdoG | 1602 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis BL-09 | ycgN | 1551 | Amphibacillus xylanus NBRC 15112 | mcsB | 1068 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumoniae RJF293 | ycgB | 1533 | Deinococcus gobiensis I-0, DSM 21396 | map | 744 |

| Moorena producens PAL-8–15-08–1 | ycf27 | 729 | Cutibacterium acnes AE1 | map | 855 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 | ybbK | 462 | Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | manP | 1944 |

| Caldanaerobacter subterraneus MB4 | XylB | 1077 | Paenibacillus sp. lzh-N1 | M1-957 | 789 |

| Geodermatophilus turciae DSM 44513 | xylA | 1185 | Corynebacterium stationis ATCC 21170 | lysC | 1266 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Mc5Re-14 | xkdM | 408 | Bacillus sp. IHB B 7164 | lysC | 1233 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC73 | XCC3509 | 972 | Agromyces sp. AR33 | Lxx16240 | 321 |

| Caldicellulosiruptor bescii RKCB130 | valS | 2625 | Methylobacillus flagellatus KT | lpxA | 783 |

| Trichormus variabilis NIES-23 | valS | 3045 | Xanthomonas albilineans HVO005 | lptC | 567 |

| Chloracidobacterium thermophilum B | valS | 2685 | Vitis vinifera PN40024 | LOC100257077 | 1054 |

| Candidatus Mycoplasma haemolamae Purdue | valS | 2508 | Vitis vinifera PN40024 | LOC100244859 | 1192 |

| Caldicellulosiruptor bescii RKCB121 | valS | 2625 | Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 | lipA | 930 |

| Cupriavidus sp. NP124 | uvrD3 | 2094 | Anabaenopsis circularis NIES-21 | leuS | 2640 |

| Rudanella lutea DSM 19387 | uvrB | 2022 | Caldanaerobacter subterraneus MB4 | LepA | 1812 |

| Corynebacterium crudilactis JZ16 | ureG | 618 | Spiribacter vilamensis DSM 21056 | lepA | 1824 |

| Actinoplanes sp. SE50/110 | ureB | 408 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii lactis KCCM 34717 | Ldb2189 | 843 |

| Stigmatella aurantiaca DW4/3–1 | uppP | 894 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii jakobsenii ZN7a-9 | Ldb1360 | 2235 |

| Chloracidobacterium thermophilum B | uppP | 855 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii lactis KCTC 3035 | Ldb1010 | 1002 |

| Paenibacillus kribbensis AM49 | ugpB5 | 1305 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii jakobsenii ZN7a-9 | Ldb0854 | 1254 |

| Ochrobactrum sp. MYb15 | ubiE | 792 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii lactis KCTC 3035 | Ldb0761 | 234 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 | trxC | 438 | Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG 19424 | kynU | 1257 |

| Rhodococcus sp. MTM3W5.2 | trxB | 990 | Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029 | kptA | 543 |

| Solidesulfovibrio magneticus RS-1 | truB | 969 | Micromonospora aurantiaca DSM 45487 | kptA | 543 |

| Collimonas arenae Ter282 | trpS2 | 1035 | Paenibacillus polymyxa CICC 10580 | kinA | 1740 |

| Leisingera caerulea DSM 24564 | trpE | 1512 | Laribacter hongkongensis HLHK9 | kcy | 666 |

| Brevibacillus laterosporus B9 | troA | 963 | Phaeobacter inhibens P72 | iscA | 360 |

| Pedobacter ginsengisoli T01R-27 | trmD | 678 | Nostoc sp. Moss6 | invB | 1452 |

| Geobacillus subterraneus KCTC 3922 | topA | 2076 | Ligilactobacillus salivarius salivarius UCC118 | infC | 525 |

| Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 | tolA | 1068 | Ligilactobacillus salivarius salivarius UCC118 | infA | 219 |

| Mycoplasmopsis fermentans PG18 | tmk | 663 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P11 | hutG | 786 |

| Virgibacillus sp. SK37 | tilS | 1389 | Candidatus Symbiobacter mobilis CR (contamination screened) | htpG | 2013 |

| Virgibacillus halodenitrificans PDB-F2 | thyA | 957 | Kutzneria albida DSM 43870 | hrcA | 1023 |

| Janthinobacterium lividum NCTC 8661 | thrS | 1908 | Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 | hisH | 594 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC73R | thrS | 1905 | Sphingopyxis sp. YR583 | hisH | 609 |

| Arcobacter sp. L | thrS | 1809 | Streptomyces sp. Wb2n-11 | hisG | 858 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis MDJK30 | thiM | 810 | Geobacter metallireducens GS-15 | hisE | 330 |

| Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo 172 | thiL | 1002 | Corynebacterium stationis ATCC 21170 | hisE | 264 |

| Deferribacter desulfuricans SSM1 | thiH | 1119 | Micromonospora viridifaciens DSM 43909 | hisE | 264 |

| Phaeobacter inhibens P80 | thiB | 978 | Moorella thermoacetica ATCC 39073 | hisC | 1161 |

| Candidatus Saccharimonas aalborgensis | tgt | 1248 | Xanthomonas albilineans FIJ080 | hflD | 615 |

| Enterobacter ludwigii P101 | tesB | 861 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P128 | hemN1 | 1356 |

| Corynebacterium striatum NCTC 9755 | tcsR4 | 723 | Corynebacterium variabile DSM 44702 | hemB | 1038 |

| Corynebacterium striatum 216 | tcsR3 | 639 | Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Novozymes | hemA | 1362 |

| Bacillus sp. H15-1 | tasA | 795 | Caldicellulosiruptor changbaiensis CBS-Z | hcp | 1650 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans HVO005 | suxR | 1032 | Paenibacillus polymyxa CICC 10580 | guxA | 2154 |

| Streptomyces sp. 57 | sseA | 840 | Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 | gtrA | 447 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 | srrA1 | 1275 | Geobacter sulfurreducens KN400 | GSU2289 | 1446 |

| Enterobacter cloacae A1137 | srlE | 960 | Geobacter sulfurreducens PCA | GSU0207 | 201 |

| Priestia megaterium WSH-002 | spoIIIAD | 384 | Geobacter sulfurreducens KN400 | GSU0201 | 2172 |

| Phaeobacter piscinae P71 | SPO1017 | 756 | Phaeobacter inhibens P92 | grxC | 258 |

| Sphaerobacter thermophilus 4ac11, DSM 20745 | smpB | 483 | Rubrobacter radiotolerans RSPS-4 | grpE | 708 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC17 | Smlt3089 | 936 | Novosphingobium pentaromativorans US6-1 | groS | 315 |

| Ligilactobacillus salivarius GJ-24 | smc | 3537 | Singulisphaera sp. GP187 | greA | 480 |

| Paenibacillus kribbensis AM49 | sigW11 | 549 | Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC17 | gpmA | 750 |

| Priestia megaterium WSH-002 | sigI | 720 | Thioalkalivibrio sp. ALRh | gmhA | 600 |

| Nostoc sp. Moss3 | serS | 1281 | Priestia megaterium Q3 | gltB | 1482 |

| Actinoplanes sp. N902-109 | selA | 1257 | Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC17 | glpK | 1500 |

| Comamonas sp. 26 | secF | 957 | Streptomyces viridosporus T7A, ATCC 39115 | glpD2 | 1656 |

| Sulfurospirillum deleyianum 5175, DSM 6946 | secE | 180 | Nostoc sp. PCC 7107 | gloB | 774 |

| Phaeobacter piscinae P42 | secA | 2700 | Xanthomonas albilineans REU209 | glnB2 | 339 |

| Phaeobacter piscinae P18 | scpA | 792 | Xanthomonas sacchari LMG 476 | glmU | 1368 |

| Lysinibacillus sp. YS11 | scpA | 780 | Caldicellulosiruptor bescii MACB1021 | glmS | 1836 |

| Streptomyces sp. RJA2910 | SCO5669 | 930 | Paenibacillus polymyxa M1 | gldF | 723 |

| Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 Genome sequencing | SCO5590 | 591 | Actinoplanes sp. N902-109 | glcA | 1248 |

| Streptomyces sp. 3214.6 | SCO5167 | 729 | Geobacillus sp. C56-T3 | GK3260 | 1290 |

| Streptomyces viridosporus T7A, ATCC 39115 | SCO0254 | 738 | Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 | GK3216 | 963 |

| Sorangium cellulosum So ce 56 | sce9191 | 993 | Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | GK3038 | 1371 |

| Sorangium cellulosum So ce 56 | sce0166 | 909 | Geobacillus sp. 12AMOR1 | GK3036 | 900 |

| Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | SAM | 109 | Geobacillus vulcani PSS1 | GK2801 | 1860 |

| Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo 172 | Rv0075 | 1173 | Geobacillus kaustophilus Et7/4 | GK2160 | 186 |

| Geobacter sulfurreducens AM-1 | ruvA | 600 | Geobacillus thermoleovorans FJAT-2391 | GK1813 | 486 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae FDAARGOS_127 | rsxA | 582 | Geobacillus vulcani PSS1 | GK1582 | 699 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7524 | rsgA | 1062 | Geobacillus sp. GHH01 | GK1316 | 1146 |

| Hydrogenobaculum sp. 3684 | rpsZ | 189 | Geobacillus sp. GHH01 | GK1185 | 885 |

| Mageeibacillus indolicus UPII9-5 | rpsU | 174 | Geobacillus vulcani PSS1 | GK1101 | 789 |

| Micromonospora citrea DSM 43903 | rpsT | 267 | Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | GK0983 | 675 |

| Priestia megaterium DSM 319 | rpsS | 279 | Geobacillus thermoleovorans FJAT-2391 | GK0603 | 657 |

| Spiribacter curvatus UAH-SP71 | rpsP | 270 | Geobacillus kaustophilus Et7/4 | GK0572 | 249 |

| Caldicellulosiruptor bescii RKCB122 | rpsP | 246 | Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | GK0545 | 369 |

| Methylobacillus flagellatus KT | rpsN | 306 | Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 | GK0418 | 225 |

| Acidobacteriaceae sp. KBS 146 | rpsK | 423 | Geobacillus sp. LC300 | GK0324 | 1233 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans XaFL07-1 | rpsG | 468 | Anaeromyxobacter sp. Fw109-5 | gcvT | 1083 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P73 | rpsF | 354 | Candidatus Endomicrobium trichonymphae Rs-D17 | gcvPB | 1437 |

| Sphingopyxis terrae ummariensis UI2 | rpsE | 714 | Geobacillus subterraneus KCTC 3922 | gcvH | 384 |

| Agromyces sp. 23–23 | rpsC | 753 | Cutibacterium acnes PA_15_1_R1 | gcvH | 372 |

| Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Goettingen | rpoZ | 201 | Corynebacterium striatum 216 | gatA | 1485 |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris vulgaris DP4 | rpoD | 1773 | Bacillus sonorensis SRCM101395 | ganA | 2055 |

| Deinococcus sp. NW-56 | rpoB | 3459 | Paenibacillus polymyxa CF05 | ganA | 1053 |

| Sphingopyxis granuli TFA | rpmJ | 126 | Frankia sp. QA3 | galE | 1041 |

| Saccharopolyspora erythraea DSM 40517 | rpmI | 195 | Caldicellulosiruptor bescii RKCB131 | fusA | 2076 |

| Brevibacillus laterosporus DSM 25 | rpmE | 201 | Phaeobacter inhibens P54 | fur | 414 |

| Janthinobacterium svalbardensis PAMC 27463 | rpmE | 270 | Dyadobacter fermentans NS114, DSM 18053 | fumC | 1404 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus ATCC BAA-365 | rpmC | 198 | Aulosira laxa NIES-50 | ftsH | 1938 |

| Sphingopyxis lindanitolerans WS5A3p | rpmB | 294 | Nitrosospira multiformis Nl4 | ftsH | 1896 |

| Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense PV20-2 | rplX | 336 | Frankia sp. QA3 | FRAAL6651 | 570 |

| Terriglobus roseus AB35.6 | rplW | 294 | Frankia alni ACN14a | FRAAL2500 | 804 |

| Sphaerobacter thermophilus 4ac11, DSM 20745 | rplV | 345 | Frankia alni ACN14a | FRAAL2444 | 270 |

| Candidatus Protochlamydia naegleriophila KNic | rplV | 336 | Frankia alni ACN14a | FRAAL1235 | 1128 |

| Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029 | rplR | 390 | Frankia alni ACN14a | FRAAL0999 | 912 |

| Hydrogenobaculum sp. HO | rplQ | 357 | Modestobacter marinus BC501 | folA | 579 |

| Luteibacter sp. 329MFSha | rplQ | 387 | Thermoclostridium stercorarium stercorarium DSM 8532 | folA | 501 |

| Novosphingobium sp. P6W | rplP | 435 | Thermoclostridium stercorarium stercorarium DSM 8532 | fliE | 300 |

| Corynebacterium striatum 216 | rplI | 453 | Cupriavidus nantongensis X1 | flgK | 1920 |

| Propionibacterium freudenreichii freudenreichii DSM 20271 | rplE | 663 | Phaeobacter inhibens P92 | flgC | 393 |

| Nitrosomonas sp. IS79A3 | rplD | 621 | Priestia megaterium QM B1551 | flbD | 216 |

| Solitalea canadensis USAM 9D, DSM 3403 | rplD | 630 | Paenibacillus sp. lzh-N1 | fhuD1 | 960 |

| Nitrospira defluvii | rplC | 621 | Arthrospira platensis C1 | ffh | 1416 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 | RPA4706 | 582 | Corynebacterium striatum KC-Na-01 | fda | 1035 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | RPA3762 | 873 | Rhodococcus jostii DSM 44719 | fadE26 | 1182 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 | RPA3585 | 513 | Simkania negevensis Z, ATCC VR-1471 | fabG-B | 744 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | RPA2908 | 645 | Phaeobacter inhibens P80 | fabB | 1230 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 | RPA2269 | 1803 | Bacillus sp. IHB B 7164 | eutC | 714 |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | RPA0026 | 1398 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P11 | edd | 1824 |

| Syntrophus gentianae DSM 8423 | rny | 1569 | Rubrobacter radiotolerans RSPS-4 | dut | 456 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa J | rluD3 | 999 | Laribacter hongkongensis LHGZ1 | dut | 450 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 | rimM | 516 | Pseudodesulfovibrio profundus 500–1 | dsrK | 1668 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans XaFL07-1 | rimK | 876 | Aliarcobacter butzleri NCTC 12481 | dprA | 777 |

| Comamonas sp. 26 | recR | 591 | Desulfotalea psychrophila LSv54 | DP2200 | 201 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P128 | recR | 600 | Streptomyces sp. 1222.2 | dnaQ2 | 726 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumoniae RJF293 | recF | 1074 | Propionibacterium freudenreichii freudenreichii DSM 20271 | dnaN | 1161 |

| Phaeobacter inhibens P83 | recA | 1068 | Frankia sp. EUN1f | dnaJ | 1146 |

| Actinoplanes sp. SE50 | rbsA | 1512 | Frankia sp. EUN1f | dnaJ | 1179 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans HVO082 | rbfA | 411 | Streptomyces sp. Root1310 | dnaE1 | 3540 |

| Nitrosococcus watsoni C-113 | queA | 1035 | Bacillus licheniformis 9945A | dnaB | 1425 |

| Limnospira indica PCC 8005 | pyrR | 534 | Caldithrix abyssi LF13, DSM 13497 | dnaA | 1401 |

| Bacillus licheniformis DSM 13 Novozymes | pyrP | 1305 | Sulfurovum sp. NBC37-1 | dnaA | 1329 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 | pyrC | 1323 | Janthinobacterium sp. 61 | dksA | 453 |

| Thioalkalivibrio sp. ALJ5 | pyrC | 1296 | Geobacter sulfurreducens PCA | divIC | 336 |

| Streptomyces sp. 1222.2 | pyrAA | 1143 | Priestia megaterium ATCC 14581 | desR | 603 |

| Streptomyces sp. 1222.2 | puuC | 1458 | Deinococcus proteolyticus MRP, DSM 20540 | der | 1326 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Mc5Re-14 | purR11 | 1041 | Micromonospora sp. CNZ295 | deoD | 708 |

| Corynebacterium doosanense CAU 212, DSM 45436 | purN | 567 | Actinoplanes teichomyceticus DSM 43866 | deoA | 1278 |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii lactis KCCM 34717 | purL | 2223 | Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac84 | degQ | 141 |

| Deinococcus proteolyticus MRP, DSM 20540 | purK | 1119 | Phaeobacter piscinae P71 | def1 | 519 |

| Propionibacterium freudenreichii shermanii JS | purE | 561 | Halorhodospira halophila SL1 | ddl | 915 |

| Cytophaga hutchinsonii ATCC 33406 | purB | 1371 | Qipengyuania flava VG1 | dcd | 555 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 | pucR | 1665 | Frankia sp. QA3 | dapB | 753 |

| Phaeobacter inhibens P88 | ptsP | 2241 | Paenibacillus polymyxa M1 | dapB | 804 |

| Janthinobacterium sp. 13 | pssA | 852 | Propionibacterium freudenreichii shermanii JS | dapB | 741 |

| Candidatus Accumulibacter regalis UW-1 | psd | 858 | Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL 2338 | dapA1 | 924 |

| Vitis vinifera PN40024 | psaJ | 132 | Bacillus sp. FJAT-21351 | dacF | 1167 |

| Actinoplanes friuliensis DSM 7358 | prsA2 | 981 | Laribacter hongkongensis LHGZ1 | cysB1 | 939 |

| Desulfohalobium retbaense HR100, DSM 5692 | prmA | 891 | Bacillus licheniformis 5NAP23 | cydC | 1725 |

| Thermoanaerobacter wiegelii Rt8.B1 | priA | 2199 | Corynebacterium glyciniphilum AJ 3170 | ctaC | 1113 |

| Thioalkalivibrio sp. AKL12 | prfA | 1086 | Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC17 | cspA2 | 246 |

| Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo 172 | ppsC | 6567 | Thermoanaerobacter sp. X514 | crcB | 405 |

| Modestobacter multiseptatus DSM 44402 | ppiB | 537 | Geobacter sulfurreducens KN400 | corA-2 | 954 |

| Cutibacterium acnes PA_30_2_L1 | PPA1529 | 468 | Anabaenopsis circularis NIES-21 | corA | 1143 |

| Cutibacterium acnes PA_30_2_L1 | PPA0469 | 1068 | Priestia megaterium DSM 319 | comGF | 438 |

| Cutibacterium acnes AE1 | PPA0083 | 2217 | Priestia megaterium WSH-002 | comGB | 1047 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Mc5Re-14 | potD1 | 1074 | Phaeobacter inhibens P78 | codA | 1281 |

| Priestia megaterium ATCC 14581 | ponA | 2835 | Salinispora pacifica DSM 45543 | cobD | 1002 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC17 | pntA-2 | 318 | Frankia alni ACN14a | coaX | 753 |

| Candidatus Saccharimonas aalborgensis | pnp | 2124 | Corynebacterium variabile DSM 44702 | cmk | 657 |

| Actinoplanes sp. SE50 | pks3A | 2271 | Deferribacter desulfuricans SSM1 | clpX | 1233 |

| Actinoplanes sp. SE50/110 | phy1 | 1215 | Bifidobacterium actinocoloniiforme DSM 22766 | clpP | 633 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa CICC 10580 | phnX | 837 | Arthrospira platensis YZ | chlL | 867 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | phnD | 1002 | Desulfovibrio cf. magneticus IFRC170 | cheW | 477 |

| Desulfosudis oleivorans Hxd3 | pheT | 2412 | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 21831 | Cgl3047 | 156 |

| Cylindrospermum stagnale PCC 7417 | pheT | 2436 | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 21831 | Cgl2611 | 1485 |

| Janthinobacterium sp. 67 | pgsA | 585 | Corynebacterium flavum ZL-1 | Cgl2418 | 252 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans GPE PC86 | pglA | 1173 | Corynebacterium flavum ZL-1 | Cgl2255 | 294 |

| Priestia megaterium DSM 319 | pfyP | 645 | Corynebacterium flavum ZL-1 | Cgl1238 | 1143 |

| Verrucosispora sp. CNZ293 | pfp | 1029 | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 21831 | Cgl1220 | 1146 |

| Propionibacterium freudenreichii freudenreichii DSM 20271 | pf456 | 1536 | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13869 | Cgl1195 | 564 |

| Pseudodesulfovibrio indicus J2 | pcm | 642 | Corynebacterium crudilactis JZ16 | Cgl0754 | 681 |

| Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 | pc0987 | 336 | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13869 | Cgl0388 | 1833 |

| Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25 | pc0116 | 1773 | Corynebacterium flavum ZL-1 | Cgl0337 | 642 |

| Bacillus sp. 1 s-1 | parC | 2424 | Actinoplanes sp. SE50 | celA | 1506 |

| Dakarella massiliensis ND3 | parC | 2556 | Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG 19424 | cca | 1248 |

| Micromonospora sp. L5 | parA | 924 | Thermoanaerobacter kivui DSM 2030 | carB | 3219 |

| Xanthomonas albilineans PNG130 | panD | 381 | Bradyrhizobium sachari BR 10556 | bll7821 | 2097 |

| Thioalkalivibrio paradoxus ARh 1 | panC | 855 | Bacillus paralicheniformis Bac84 | BLi02578 | 438 |

| Fibrella aestuarina BUZ 2 | pacB | 432 | Bifidobacterium longum longum CCUG30698 | BL0873 | 1596 |

| Rhodococcus opacus ATCC 51882 | paaN | 2040 | Bifidobacterium longum longum CCUG30698 | BL0422 | 1977 |

| Collimonas arenae Ter10 | paaF | 777 | Bacillus sp. 1 s-1 | BL03510 | 618 |

| Streptomyces scabiei 87.22 | oppD3 | 996 | Bacillus licheniformis 5NAP23 | BL03504 | 1314 |

| Bacillus sonorensis SRCM101395 | oppD | 1068 | Bacillus licheniformis 5NAP23 | BL03493 | 2433 |

| Mycoplasmoides fermentans M64 | oppC-1 | 999 | Bifidobacterium longum longum CCUG30698 | BL0349 | 627 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Sb3-1 | occM1 | 660 | Bacillus paralicheniformis ATCC 12759 | BL03105 | 543 |

| Rubrobacter radiotolerans RSPS-4 | nusG | 540 | Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | BL02837 | 1857 |

| Xanthomonas sacchari LMG 476 | nusG | 558 | Bacillus sp. H15-1 | BL02416 | 660 |

| Delftia sp. GW456-R20 | nuoN | 1494 | Bacillus paralicheniformis 14DA11 | BL01721 | 1995 |

| Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P129 | nuoM | 1548 | Bacillus licheniformis 5NAP23 | BL01149 | 327 |

| Phaeobacter inhibens P92 | nuoL | 2130 | Bacillus sonorensis SRCM101395 | BL00226 | 393 |

| Thioalkalivibrio paradoxus ARh 1 | nuoI | 489 | Paenibacillus polymyxa CF05 | bioB | 1008 |

| Kribbella flavida IFO 14399, DSM 17836 | nuoD | 1206 | Xanthomonas translucens pv. cerealis CFBP 2541 | bfr | 471 |

| Acidovorax sp. 93 | nuoD | 1254 | Lelliottia nimipressuralis SGAir0187 | betA | 1665 |

| Isoptericola variabilis 225 | nuoA | 363 | Frateuria aurantia Kondo 67, DSM 6220 | bamB | 1209 |

| Rhodococcus koreensis DSM 44498 | nuoA | 360 | Thauera chlorobenzoica 3CB1 | azo1431 | 852 |

| Streptomyces sp. 57 | nucS | 672 | Saccharopolyspora erythraea NRRL 2338 | atzB | 1392 |

| Sphingopyxis sp. C-1 | nodQ | 1902 | Delftia sp. 60 | atpH | 540 |

| Nitrospira defluvii | NIDE4034 | 333 | Thioalkalivibrio sp. ALgr1 | atpH | 537 |

| Nitrospira defluvii | NIDE1341 | 573 | E. coli 2886–75 | atpG | 795 |

| Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 | nemA | 1110 | Nitrosococcus watsoni C-113 | atpG | 870 |

| Geobacillus thermocatenulatus KCTC 3921 | ndoA | 351 | Leuconostoc gelidum gasicomitatum LMG 18811 | atpC | 450 |

| Phaeobacter inhibens P80 | ndk | 423 | Phaeobacter gallaeciensis P129 | atpC | 414 |

| Flavobacterium johnsoniae UW101, ATCC 17061 | nbaC | 540 | Nostoc sp. PCC 7107 | asr1559 | 252 |

| Streptomyces sp. 57 | nagB | 786 | Nostoc sp. PCC 7107 | asr0064 | 237 |

| Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli Gsoil 348 | nadK | 849 | Xanthomonas albilineans MTQ032 | aspS | 1752 |

| Nitrosospira briensis Nsp8 | nadA | 1101 | Geobacillus sp. C56-T3 | aroA | 1083 |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa M1 | arnT | 2355 | Micromonospora sp. CNZ295 | alaS | 2679 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis MDJK30 | argJ | 1221 | Acidovorax sp. 93 | ahcY | 1434 |

| Sphaerobacter thermophilus 4ac11, DSM 20745 | argH | 1371 | Modestobacter marinus BC501 | adk | 624 |

| Janthinobacterium svalbardensis PAMC 27463 | argA | 1320 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii bulgaricus ND02 | addA | 3684 |

| Ligilactobacillus salivarius salivarius UCC118 | apt | 519 | Collimonas arenae Ter282 | aceK | 1785 |

| Priestia megaterium QM B1551 | amt | 1227 | Lysinibacillus sp. YS11 | accA | 957 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | alr4917 | 1689 | Cupriavidus necator NH9 | aat | 759 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | alr3663 | 1050 | Phaeobacter inhibens P88 | aat | 633 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | alr2594 | 435 | Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | all4101 | 384 |

| Trichormus variabilis ATCC 29413 | alr0203 | 480 | Nostoc sp. Moss5 | all3116 | 738 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | all5344 | 468 | Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 | all1863 | 864 |

| Trichormus variabilis NIES-23 | all4824 | 798 | Trichormus variabilis ATCC 29413 | all0781 | 1590 |

| Trichormus variabilis ATCC 29413 | all4426 | 1254 |

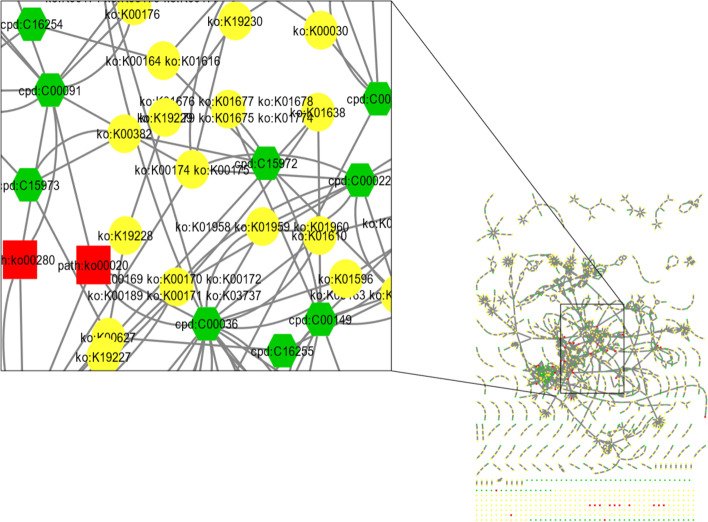

Pathway analysis

Pathway analysis is a powerful tool to understand the biological significance of gene lists generated from high-throughput experiments. In this study, pathway analysis was used to identify 16 significant pathways enriched in the predicted genes. The network of pathway enrichment of the metagenome data has been shown in Fig. 10. These pathways are involved in a variety of essential cellular processes, including biosynthesis, energy production, and signaling. The CMP-KDO biosynthesis II (from D-arabinose 5-phosphate) pathway is one of the most significant pathways identified in this study [39]. It is involved in the biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an essential component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 1S(i)). Two sequences, aconitate hydratase (K01681) and citrate synthase (K01647), are associated with the TCA cycle pathway. They have been found in Glycine max (soybeans) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast). The TCA cycle is essential for optimal functioning of primary carbon metabolism in plants (Fig. 1S(ii-iv)). Aconitate hydratase catalyzes the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate in the TCA cycle. The function of aconitate hydratase has been well studied in model plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana. The TCA cycle is a metabolic process that occurs in plants, animals, fungi, and other bacteria. It is a series of chemical reactions that converts acetyl-CoA into carbon dioxide and energy. The TCA cycle is an important source of energy for cells and also plays a role in the synthesis of other molecules such as amino acids and fatty acids [40]. The next pathway involved the biosynthesis of fatty acids (Fig. 1S(v)). This is essential for the formation of membranes, which are necessary for the viability of all cells, except Archaea. Fatty acids are also a compact energy source for seed germination. Enenoyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase I (K00208) is an enzyme involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, prodigiosin biosynthesis, and biotin metabolism pathways. Another significant pathway that has been identified is biotin metabolism (Fig. 1S(vi)). The Biotin metabolism is a universal and essential process that is required for intermediary metabolism in all three domains of life: archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes [41]. It is an indispensable vitamin for human health and plays a vital role in well-being [42]. This essential nutrient can be obtained through the consumption of a wide range of foods, including legumes, soybeans, tomatoes, romaine lettuce, eggs, cow's milk, and oats. One of the primary functions of biotin is to act as a cofactor for enzymes, facilitating carboxylation reactions that are crucial for processes, such as gluconeogenesis, amino acid catabolism, and fatty acid metabolism. In addition, it produces biochemicals that have a wide variety of applications in nutrition and industry. Another gene sequence, also been discovered that encodes a protein called 2-dehydro-3-deoxyphosphooctonate aldolase (K01627), also known as Kdo-8-phosphate synthase (KDO 8-P). This protein is a major constituent of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of most Gram-negative bacteria. It is essential for the survival of bacteria and pathogens, and is involved in the biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars (Fig. 1S(vii)) and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis pathways (Fig. 1S(viii)) [43]. Another important pathway has been discovered that is essential for plant growth and development that is called the porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism pathway (Fig. 1S(ix)). Porphyrins are a group of organic compounds essential for life. They are found in chlorophyll, which is a green pigment that plants use for photosynthesis. Porphyrins are also found in heme, a protein that carries oxygen in the blood. The porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolic pathways are complex processes that involve the synthesis of porphyrins and chlorophyll. This pathway is essential for plant growth and development because it provides plants with the materials required to produce chlorophyll and heme. The porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolic pathways are synthesized by a multistep pathway that involves eight enzymes [44], which is a complex process involving numerous chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes. The regulation of chlorophyll and heme balance is important for the growth and development of plants [45]. Porphyrin biosynthesis is one of the most conserved pathways known, with the same sequence of reactions occurring in all species. By associating different metals, porphyrins give rise to the “pigments of life”: chlorophyll, heme, and cobalamin [46]. The glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolic pathways play a pivotal role in the sustenance of organisms and their biochemical functions (Fig. 1S(x)). In the glyoxylate pathway, citrate synthase (K01647) is responsible for citrate formation from acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. Citrate is then converted into succinate, which is used to synthesize glucose [47]. This process entails the conversion and application of these intermediates, which are generated via the catabolism of fatty acids, metabolism of amino acids, and fermentation of carbohydrates. These compounds can facilitate the synthesis of diverse molecules such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids. The glyoxylate and dicarboxylate pathway holds significant importance in the realm of plant physiology, owing to the fact that unlike animals, plants are unable to stockpile carbohydrates in the form of glycogen. Rather than undergoing direct utilization, fatty acids are transformed into glucose molecules, which play a crucial role in supporting growth and reproduction. The bacterial pathway is of paramount importance, as it facilitates the conversion of carbon dioxide into organic compounds, thereby enabling the acquisition of energy from carbon dioxide. In general, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate pathways are crucial and intricate metabolic pathways that are indispensable for the viability of diverse organisms. The aforementioned metabolic pathway is important for the generation of energy, carbon metabolism, and production of biomolecules. Comprehending the overall metabolic network and its implications in cellular function requires a thorough understanding of the intricacies of glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. The process of prodigiosin biosynthesis was initially characterized in the γ-proteobacterium, Serratia marcescens. Subsequently, it was studied and characterized in another bacterium, Pseudoalteromonas rubra. In these organisms, prodigiosin biosynthesis involves a series of biochemical reactions and enzymatic steps that lead to the production of this captivating red pigment (Fig. 1S(xi)). By exploring the biosynthetic pathways of prodigiosin in different bacterial species, researchers have gained valuable insights into the diversity and complexity of this intriguing pigment and its potential applications in various fields. ABC transporters pathway are a large, ancient protein superfamily found in all living organisms (Fig. 1S(xii)). They function as molecular machines by coupling ATP binding, hydrolysis, and phosphate release for the translocation of diverse substrates across membranes. ABC transporters are also known as efflux pumps because they mediate the cross-membrane transportation of various endo- and xenobiotic molecules energized by ATP hydrolysis [48] and the arginine transport system substrate-binding protein(K09996), which specifically binds to arginine molecules and facilitates their transport across the cell membrane. This protein is part of a large complex involved in cellular arginine uptake. Substrate-binding proteins play a crucial role in the arginine transport system by recognizing and capturing arginine molecules from the extracellular environment and initiating their transport into cells. It ensures the specificity and efficiency of arginine uptake, contributing to various biological processes that require arginine as a nutrient or signaling molecule. The biosynthetic pathways of cofactors employ a greater quantity of innovative organic chemistry compared to other pathways in primary metabolism (Fig. 1S(j)). As a result, there is a wealth of research being conducted on the mechanisms of cofactor biosynthetic enzymes [49]. There are two sequence of arginine transport system substrate-binding protein (ASBP) (K09996, K09997) have been associated with biosynthetic pathways of cofactors. The function of these protein is unknow. It is a protein that is involved in the transport of arginine across the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria. ASBP is a member of the ABC transporter family, which is a large family of proteins that are involved in the transport of a variety of molecules across membranes [50]. The small subunit ribosomal protein S12 (K02950) is present in both mitochondrial and bacterial ribosomes (Fig. 1S(xiv)). Ribosomal protein S12 is an essential component of the small subunit within the ribosome that is responsible for protein synthesis. In E. coli, S12 plays a significant role in facilitating translation initiation. This protein consists of approximately 120–150 amino acid residues and is fundamentally basic in nature [51]. Two-component systems represent intricate signaling pathways that have gained significant attention during the initial stages of the 1980s. Their emergence into the spotlight can be primarily attributed to their identification within the paradigmatic microorganism, E. coli (Fig. 1S(xv)). These systems provide living organisms with the ability to detect and convert a diverse array of incoming signals, enabling them to adjust and respond in a highly adaptable manner to alterations in both their external and internal environments [52]. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (K03406) are the most common receptors in bacteria and archaea. They are arranged as trimers of dimers that form hexagonal arrays in the cytoplasmic membrane or cytoplasm [53]. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) are also involved in bacterial chemotaxis, which is essential for the host colonization and virulence of many pathogenic bacteria causing human, animal, and plant diseases (Fig. 1S(xvi)). These receptors undergo reversible methylation during the adaptation of the bacterial cells to environmental attractants and repellents. They are also involved in bacterial chemotaxis. MCPs are concentrated at the cell poles in an evolutionarily diverse panel of bacteria and archae [54]. They are classified into different classes according to their ligand-binding region and membrane topology. Chemotaxis is the process by which cells sense chemical gradients in their environment and move towards more favorable conditions. MCPs are a family of bacterial receptors that mediate chemotaxis to diverse signals and respond to changes [53] (Table 4).

Fig. 10.

The Pathway Enrichment analysis

Table 4.

Provides more specific breakdown of information on pathways and sequences

| Pathway | Species | #Seqs | KO |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMP-KDO biosynthesis II (from D-arabinose 5-phosphate) | Arabidopsis lyrate | k141_2112_1 | AT1G53000.1 |

| TCA cycle (plant) | K01681 | ||

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | None | k141_2161_1 | K00208 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | None | k141_1768_1 | K01647 |

| Biotin metabolism | None | k141_2161_1 | K00208 |

| Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | None | k141_2112_1 | K01627 |

| Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | None | k141_566_2 | K00230 |

| k141_503_2 | |||

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | None | k141_1768_1 | K01647 |

| Prodigiosin biosynthesis | None | k141_2161_1 | K00208 |

| ABC transporters | None | k141_1767_1 | K09996 |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors | None | k141_566_2 | K09996 |

| k141_503_2 | K09997 | ||

| k141_2161_1 | |||

| Ribosome | None | k141_588_1 | K02950 |

| k141_2090_1 | |||

| k141_1643_1 | |||

| k141_1118_1 | |||

| k141_1964_1 | |||

| k141_2047_1 | |||

| k141_1682_1 | |||

| Two-component system | None |

k141_1278_1 s |

K03406 |

| Biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars | None | K01627 | |

| Bacterial chemotaxis | None | K03406 | |

| Citric acid cycle (TCA cycle) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | k141_1768_1 | K01647 |

Conclusion

The enormous amount of data generated from omics studies is possible only with fast and accurate handy omics tools, as they are available on today’s scientific platform. Metagenomics is an area that is booming with the advent of NGS. Metagenomics is the study of the genes and genomes of microbes that cannot be cultured in a laboratory. Metagenomic data of a sample can be generated by shotgun sequencing of total community DNA. The gene sequences obtained from metagenomic shotgun sequencing can be Nucleotide-Nucleotide BLAST (blastn) mapped to the available microbial genomes in public domain databases, such as NCBI GenBank, RefSeq, and Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG). This will provide an inventory of all microbial genera and species present in the sample. The unmapped reads were annotated using different in silico tools, such as DIAMOND, KEGG, CAZy, and eggNOG, for the identification of genes and their functions. Taxonomic and functional annotation of genes helps understand the metabolic pathways that are unique to a particular microbiome. Based on these inferences, it is possible to propose models for the role of microbes in health and disease. Soybean is one of the most important crops in the world and a major source of protein and oil. The soybean endosphere is a unique microenvironment colonized by a large number of bacteria, fungi, and viruses. The composition of the endospheric microbiome differs from that of the rhizospheric microbiome. The microbiome of the endosphere plays an important role in plant health. In this study, we aimed to elucidate the usefulness of the microbiome in revealing the signatures of microbes in healthy and diseased soybean agricultural lands. To identify the microbes associated with health and disease, microbial diversity in the soybean endosphere was analyzed by metagenomic analysis using the MG-RAST tool. The analysis of the soybean endosphere microbiome revealed signatures of microbes associated with health and disease. The most dominant group of bacteria in the endosphere is Streptomyces, followed by Chryseobacterium, Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and Mitsuaria. These bacteria play a role in a variety of biological pathways, including CMP-KDO biosynthesis II (from D-arabinose 5-phosphate), TCA cycle (plant), citrate cycle (TCA cycle), fatty acid biosynthesis, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. These data revealed that it is a rich source of potential biomarkers for soybean plants. The results of this study will help us understand the role of the endosphere microbiome in plant health and identify the microbial signatures of health and disease.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Pathway analysis.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere appreciation for the Department of Bioinformatics, Mathematics and Computer Applications, MANIT, Bhopal, MP, India for provide the facilities for research.

Authors’ contributions

U.G. and J.K.C. both contributed equally to the conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis, and the interpretation of the data. Additionally, U.C. and J.K.C. contributed equally to the drafting and revision of the journal article for its.

Funding

No financial support (funding, grants, sponsorship) that you have received.

Availability of data and materials

In the Manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Competing interests

Author have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Crawford GW (2006) East Asian plant domestication. In Archaeology of Asia, M.T. Stark (Ed.). 10.1002/9780470774670.ch5

- 2.Pratap A, Gupta SK, Kumar J, Mehandi S, Pandey VR (2016) Chapter 12 - Soybean. In: Gupta SK (ed) Breed. Oilseed Crops Sustain. Prod. Academic Press, San Diego, p. 293–315. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801309-0.00012-4

- 3.Sondhia S, Khankhane PJ, Singh PK, Sharma AR (2015) Determination of imazethapyr residues in soil and grains after its application to soybeans. J Pestic Sci D14–109

- 4.Bakhsh A, Sırel IA, Kaya RB, Ataman IH, Tillaboeva S, Dönmez BA, et al (2021) Chapter 6 - Contribution of Genetically Modified Crops in Agricultural Production: Success Stories. In: Singh P, Borthakur A, Singh AA, Kumar A, Singh KK (eds). Policy Issues Genet. Modif. Crops. Academic Press, p 111–42. 10.1016/B978-0-12-820780-2.00006-6

- 5.Bolaji AJ, Wan JC, Manchur CL, Lawley Y, de Kievit TR, Fernando WGD, et al (2021) Microbial community dynamics of soybean (Glycine max) is affected by cropping sequence. Front Microbiol 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hassani MA, Durán P, Hacquard S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome. 2018;6:58. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0445-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeoh YK, Dennis PG, Paungfoo-Lonhienne C, Weber L, Brackin R, Ragan MA, et al. Evolutionary conservation of a core root microbiome across plant phyla along a tropical soil chronosequence. Nat Commun. 2017;8:215. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg G, Grube M, Schloter M, Smalla K. The plant microbiome and its importance for plant and human health. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch PR, Mauchline TH. Who’s who in the plant root microbiome? Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:961–962. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottel NR, Castro HF, Kerley M, Yang Z, Pelletier DA, Podar M, et al. Distinct microbial communities within the endosphere and rhizosphere of Populus deltoides roots across contrasting soil types. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5934–5944. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05255-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes R, Garbeva P, Raaijmakers JM. The rhizosphere microbiome: significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:634–663. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mardanov AV, Kadnikov VV, Ravin NV (2018) Chapter 1 - Metagenomics: A Paradigm Shift in Microbiology. In: Nagarajan M (ed). Metagenomics. Academic Press, p. 1–13. 10.1016/B978-0-08-102268-9.00001-X

- 13.Bodor A, Bounedjoum N, Vincze GE, Erdeiné Kis Á, Laczi K, Bende G, et al. Challenges of unculturable bacteria: environmental perspectives. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2020;19:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11157-020-09522-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handelsman J, Rondon MR, Brady SF, Clardy J, Goodman RM. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chem Biol. 1998;5:R245–249. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace NR. Analyzing natural microbial populations by rRNA sequences. ASM News. 1985;51:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choubey J, Choudhari JK, Sahariah BP, Verma MK, Banerjee A (2021) Chapter 25 - Molecular Tools: Advance Approaches to Analyze Diversity of Microbial Community. In: Shah MP, Sarkar A, Mandal S (eds). Wastewater Treat. Elsevier, p. 507–20. 10.1016/B978-0-12-821881-5.00025-8

- 17.Choudhari JK, Choubey J, Verma MK, Chatterjee T, Sahariah BP (2022) Chapter 10 - Metagenomics: the boon for microbial world knowledge and current challenges. In: Singh DB, Pathak RK (eds). Bioinformatics. Academic Press, p. 159–75. 10.1016/B978-0-323-89775-4.00022-5

- 18.Yun J, Ryu S. Screening for novel enzymes from metagenome and SIGEX, as a way to improve it. Microb Cell Factories. 2005;4:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choubey J, Choudhari JK, Verma MK, Chaterjee T, Sahariah BP (2022) Systems Biology Aided Functional Analysis of Microbes that Have Rich Bioremediation Potential for Environmental Pollutants. In: Microb Remediat Azo Dyes Prokaryotes. CRC Press pp. 157–170

- 20.Choudhari JK, Verma MK, Choubey J, Banerjee A, Sahariah BP (2021) Chapter 24 - Advanced Omics Technologies: Relevant to Environment and Microbial Community. In: Shah MP, Sarkar A, Mandal S (eds). Wastewater Treat. Elsevier, p. 489–506. 10.1016/B978-0-12-821881-5.00024-6

- 21.Wilke A, Bischof J, Gerlach W, Glass E, Harrison T, Keegan KP, et al. The MG-RAST metagenomics database and portal in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D590–D594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andreote AP, Dini-Andreote F, Rigonato J, Machineski GS, Souza BC, Barbiero L, et al (2018) Contrasting the Genetic Patterns of Microbial Communities in Soda Lakes with and without Cyanobacterial Bloom. Front Microbiol 9:244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Chen I-MA, Markowitz VM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Pillay M, et al (2016) IMG/M: integrated genome and metagenome comparative data analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res gkw929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Mukherjee S, Palaniappan K, Seshadri R, Chu K, Ratner A, Huang J, et al. Bioinformatics analysis tools for studying microbiomes at the DOE Joint Genome Institute. J Indian Inst Sci. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s41745-023-00365-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen I-MA, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Ratner A, Huang J, Huntemann M, et al. The IMG/M data management and analysis system v.7: content updates and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D723–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, Ciufo S, Haddad D, McVeigh R, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D733–745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT Protein Sequence Data Bank and Its New Supplement TREMBL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:21–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vurukonda SSKP, Giovanardi D, Stefani E. Plant growth promoting and biocontrol activity of streptomyces spp. as endophytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:952. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horstmann JL, Dias MP, Ortolan F, Medina-Silva R, Astarita LV, Santarém ER. Streptomyces sp. CLV45 from Fabaceae rhizosphere benefits growth of soybean plants. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:1861–71. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasim F, Dey A, Qureshi IA. Comparative genome analysis of Corynebacterium species: the underestimated pathogens with high virulence potential. Infect Genet Evol. 2021;93:104928. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]