Highlights

-

•

Clinically, cerebellar patients exhibit various combinations of a vestibulocerebellar syndrome, a cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome and a cerebellar motor syndrome.

-

•

Cerebellar EEG is now being applied in cerebellar disorders to unravel impaired electrophysiological patterns associated within disorders of the cerebellar cortex.

-

•

Cerebellum-motor cortex inhibition (CBI) is a neurophysiological biomarker showing an inverse association between cerebellothalamocortical tract integrity and ataxia severity.

Keywords: Cerebellum, Neurophysiology, Ataxia, Gait, Eyeblink conditioning, Sensorimotor adaptation, EEG, CBI

Abstract

There are numerous forms of cerebellar disorders from sporadic to genetic diseases. The aim of this chapter is to provide an overview of the advances and emerging techniques during these last 2 decades in the neurophysiological tests useful in cerebellar patients for clinical and research purposes. Clinically, patients exhibit various combinations of a vestibulocerebellar syndrome, a cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome and a cerebellar motor syndrome which will be discussed throughout this chapter. Cerebellar patients show abnormal Bereitschaftpotentials (BPs) and mismatch negativity. Cerebellar EEG is now being applied in cerebellar disorders to unravel impaired electrophysiological patterns associated within disorders of the cerebellar cortex. Eyeblink conditioning is significantly impaired in cerebellar disorders: the ability to acquire conditioned eyeblink responses is reduced in hereditary ataxias, in cerebellar stroke and after tumor surgery of the cerebellum. Furthermore, impaired eyeblink conditioning is an early marker of cerebellar degenerative disease. General rules of motor control suggest that optimal strategies are needed to execute voluntary movements in the complex environment of daily life. A high degree of adaptability is required for learning procedures underlying motor control as sensorimotor adaptation is essential to perform accurate goal-directed movements. Cerebellar patients show impairments during online visuomotor adaptation tasks. Cerebellum-motor cortex inhibition (CBI) is a neurophysiological biomarker showing an inverse association between cerebellothalamocortical tract integrity and ataxia severity. Ataxic gait is characterized by increased step width, reduced ankle joint range of motion, increased gait variability, lack of intra-limb inter-joint and inter-segmental coordination, impaired foot ground placement and loss of trunk control. Taken together, these techniques provide a neurophysiological framework for a better appraisal of cerebellar disorders.

1. Introduction

Cerebellar ataxias arise from a highly heterogeneous group of disorders, often considered as a spectrum of disorders. They may affect patients from early stages of development until late adulthood. In many cases, the disorder impacts noticeably on quality of life and daily life activities. Common causes of cerebellar disorders encountered in the clinic are degenerative (in particular multiple system atrophy, recessive ataxias such as Friedreich ataxia and autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias SCAs), of vascular origin (stroke), toxic-induced (in particular due to ethanol, phenytoin, lithium salts), immune-mediated (especially multiple sclerosis), neoplastic (primary or metastatic disease) or paraneoplastic, due to malformations (such as Chiari malformations), of infectious origin (abscess, cerebellitis) or post-traumatic (Manto and Hallett, 2003). Patients may exhibit pure cerebellar signs or combinations of cerebellar and extra-cerebellar deficits.

The scope of this chapter is to provide an overview of the neurophysiological assessment of cerebellar ataxia. The chapter will focus on motor deficits (limbs, posture/gait) and does not expand on oculomotor deficits or cognitive deficits. The relevant neuroanatomy is in the companion paper of this chapter (Manto, 2022). Briefly, the cerebellar cortex is organized into a triple layer: the Purkinje layer is located between the internal granular layer (at the origin of parallel fibers running through the dendritic arborization of Purkinje neurons) and the outer molecular layer composed of inhibitory interneurons. Purkinje neurons are inhibitory and project to cerebellar nuclei and vestibular nuclei (Ito and Yoshida, 1964). The inferior olive projects to the Purkinje neurons via crossed climbing fibers, and mossy fibers projecting to granular layer emerge from numerous brainstem and spinal sources. Whereas the afferent tracts reach the cerebellum via the 3 cerebellar peduncles, the efferent tracts leave the cerebellum mainly via the superior and inferior cerebellar tracts (Manto and Habas, 2016). The cerebellum is divided into 3 lobes (anterior, posterior, paraflocculus/flocculus) and 3 parasagittal zones (vermis, paravermis, lateral zone) (Jansen and Llinas, 1969). Purkinje neurons from the vermis project to the fastigial nuclei, those from the paravermis project to the interposed nuclei (emboliform and globose in humans) and the Purkinje neurons located laterally project to dentate nuclei. The cerebellum is divided into 10 lobules (I to X according to the classification of Larsell). The anterior lobe corresponds to lobules I-V, the posterior lobe to lobules VI-IX and the flocculo-nodular lobe corresponds to lobule X. There is a segregation of the connections between the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex into multiple parallel loops.

Multiple theories of the roles of the cerebellum on motor control have been proposed these last 4 decades, including computational theories such as the Universal Cerebellar Transform (UCT) which considers that the relatively uniform anatomy and physiology of the cerebellar cortex implies the same computational function across diverse domains, with the cerebellum maintaining a homeostatic behavioral baseline (see (Schmahmann, 2019). A detailed comparison or evaluation of these theories is outside the scope of this chapter.

2. Cerebellar motor syndrome

From the clinical standpoint, cerebellar deficits are currently gathered into 3 syndromes:

-

–

a vestibulo-cerebellar syndrome (VCS): patients show dysmetria of saccades, saccadic pursuit, various forms of nystagmus, impaired vestibulo-ocular responses (VOR) and skew deviation.

-

–

a cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (Schmahmann syndrome, CCAS/SS): this syndrome is characterized by various combinations of dysexecutive deficits, visuospatial deficits, linguistic deficits and affective/emotional/social dysregulation. Dysmetria of thought is a major feature of CCAS/SS (Argyropoulos et al., 2020).

-

–

a cerebellar motor syndrome (CMS): patients exhibit a range of motor deficits affecting speech (ataxic dysarthria, mutism), limb movements (dysmetria: hypermetria and hypometria, dysdiadochokinesia, tremor), various degrees of hypotonia, irregular writing, staggering gait and balance, impaired learning of complex motor skills.

This subdivision has a solid anatomical basis:

-

–

for the VCS: lesions are located at the level of lobules IX-X and the dorsal oculomotor vermis corresponding to lobules V to VII.

-

–

for the CCAS/SS: lesions occur at the level of lobules VI-IX.

-

–

for the CMS is observed for lesions at the level of lobules I-V, VI and VIII.

Each of these syndromes can be assessed clinically with a dedicated rating scale: Scale for Oculomotor Deficits in Ataxias (SODA) scale for the VCS, Schmahmann scale for the CCAS/SS, Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA)/ International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS) for the CMS (Schmitz-Hübsch et al., 2006, Shaikh et al., 2022, Hoche et al., 2018, Trouillas et al., 1997).

2.1. EEG analysis

2.1.1. Bereitschaftpotential (BP)

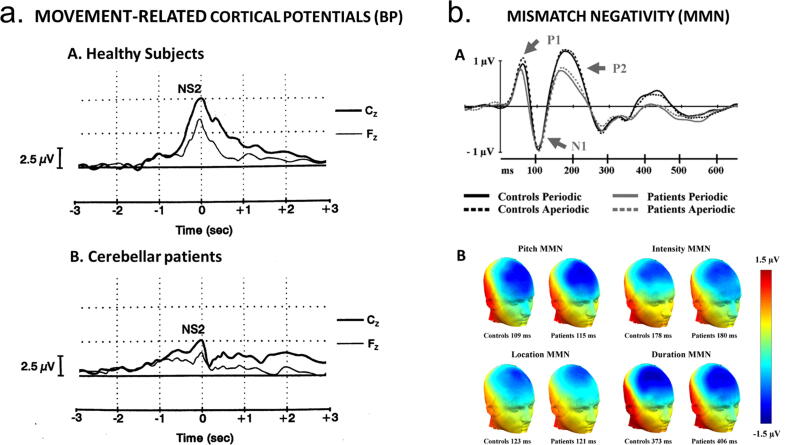

Self-paced movements are preceded by a negative EEG potential called the Bereitschaftpotential (BP). Cerebellar patients show a depression of the magnitude of the BP which may even be absent when the dentate nucleus is destroyed by a pathological process, presumably as a result of the involvement of the dentato-thalamo-cortical pathway (Fig. 1a; Kitamura et al., 1999); see also section 5). This occurs because the dentate nucleus exerts a facilitatory drive upon the generation of the BP. Thus, dysfunction of cerebellar motor function might be verified by analysis of the BP.

Fig. 1.

a) Averages of movement-related cortical potentials in 3 healthy subjects (A) and in 3 patients (B) presenting a severe cerebellar motor syndrome associated with a marked cerebellar cortical atrophy. Sequential task: subjects are asked to push on keys of a keyboard. Peak amplitudes of the NS2 component of the Bereitschaftpotential (BP) are decreased in cerebellar patients, indicating a role of the cerebellum in the generation of amplitudes of BPs. From (Manto and Hallett, 2003). With permission. b) Mismatch negativity (MMN) response in patients with cerebellar cortical atrophy and matched controls. While watching a silent movie, a stream of task-irrelevant sounds was presented. A standard sound was presented 60% of the time, whereas the remaining sounds deviated from the standard on one of four dimensions: duration, intensity, pitch, or location. The timing between stimuli was either periodic or aperiodic. A: Grand average ERPs to standard sounds recorded at the frontocentral FCz electrode. B: Scalp maps showing the spatial distribution of the grand average MMNs at peak latency (measured at Fz) in the periodic SOA-condition. The MMN potentials showed a maximum negative amplitude over frontal electrodes and reversed polarity at posterior temporal electrodes. From: (Moberget et al., 2008), with permission.

2.1.2. Mismatch negativity and other event-related potentials

The cerebellum's contribution to sensory processing might not be limited to supporting movement preparation and regulation. Indeed, the cerebellum impacts somatosensory input processing at very early stages (Restuccia et al., 2001). The mismatch negativity (MMN), a specific event-related potential (ERP), reflects pre-attentive recognition of changes in the incoming stimulus by a comparison between the new stimulus with sensory memory traces (Restuccia et al., 2007). Fig. 1b illustrates an example of MMN when a standard sound is presented 60% of the time, whereas the remaining sounds deviate from the standard on one of four dimensions: duration, intensity, pitch, or location (Moberget et al., 2008). The maximum negative amplitude is observed over frontal electrodes. During the paradigm of 'oddball' stimulation, a parieto-occipital extra-negativity occurs (somatosensory mismatch negativity: S-MMN), which is different in terms of scalp distribution and latency from the N140 response occurring in a 'standard-omitted' stimulation. When the same procedure is applied in patients with a unilateral cerebellar lesion, the S-MMN is clearly aberrant after stimulation of the affected hand (ipsilaterally to the affected cerebellar hemisphere), but earlier ERPs are normal. These findings argue for a cerebellar processing which is involved in pre-attentive detection of somatosensory input changes ((Restuccia et al., 2007); see also Section 6).

One current leading theory is that the cerebellum influences internal forward models that play a role in motor, cognitive and affective control (Manto, 2022). The sensory predictive coding processes and response adaptation have been compared in control subjects and cerebellar patients using behavioural tests with concomitant EEG recordings (Tunc et al., 2019). Sensory prediction coding was assessed with an auditory distraction model and error-related behavioral adaptation with a visual flanker task. The following ERPs were studied: the P3a for orientation of attention, the N2 and the error-related negativity (ERN) for cognitive adaptation processes/consequences of response errors, the error-related positivity (Pe) for error-awareness, the mismatch negativity (seen as a neurophysiological correlate of predictive coding) for sensory predictive coding, and the reorientation negativity (RON) for reorientation after unanticipated events. Reaction times were slower in cerebellar patients, unlike the error rates (this refers to error-related hehavioral adaptation, see Peterburs et al., 2015, Peterburs and Desmond, 2016). For both groups, P3a amplitudes were larger in distraction trials, but the P3a amplitude was smaller in patients. The MMN as well as behavioral and EEG-correlates of response adaptation (ERN/N2) were similar in the 2 groups (suggesting that cerebellar patients are not more distracted by deviant, i.e., prediction-violating, sensory information), whereas the Pe was decreased in patients. During sensory predictive coding, RON amplitudes were significantly larger in controls. According to these results, processes generating internal forward models were preserved in cerebellar patients, whereas updating of mental models and error awareness were impaired. These are surprising findings since cerebellar dysfunction is expected to impair processes contributing to internal forward models. The frontal P3a (a marker of attentional shifting and updating of a mental model) and the RON (a marker of attentional re-orienting processes to the primary task after being distracted) were both abnormal in patients. These processes are mediated by dorsolateral and orbitofrontal areas which receive inputs from the basal ganglia (Lindsay and Storey, 2017). It is plausible that these circuits are primarily affected in the disease process. In other words, deficits of attention and set shifting would be more sensitive markers of cognitive dysfunctions in cerebellar ataxias than predictive coding itself. One has to consider the limitations of this single study, including a small group of heterogeneous slowly progressive ataxias (n = 23 patients) involving not only the cerebellum (patients presented various SCAs or AOA2) and with an average SARA score of 12.8 +/- 5 (mean +/- SD; range from 4.75 to 23).

2.2. Kinematics: Fast single-joint and multi-joint movements

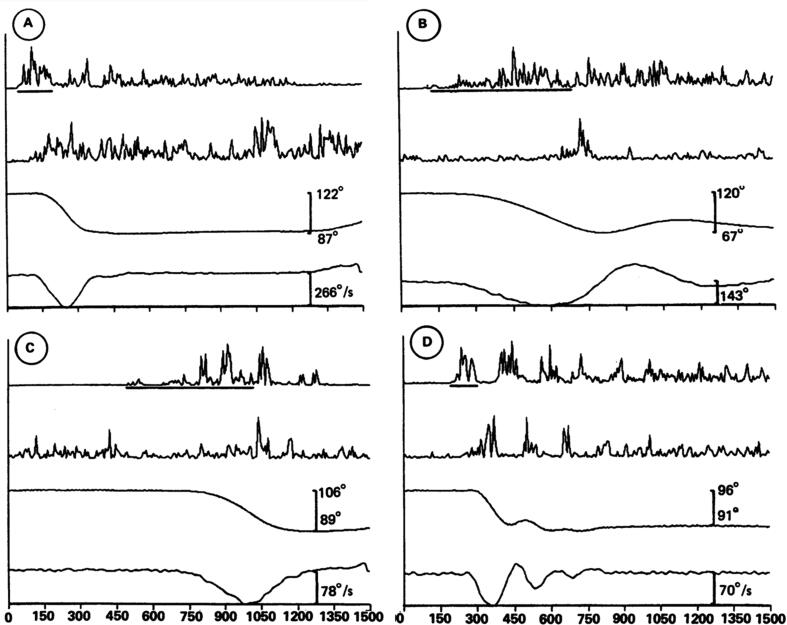

Fast goal-directed movements are most often predictive in nature, especially for moving targets in the environment of daily life (Kakei et al., 2019). The prediction is usually multimodal. For instance, during a reaching task for a moving target, the subject has to predict both the dynamic trajectory of the target and the future movement of the limb. Therefore, performing predictions and validating the predictions as compared to actual sensory information is critical (Popa and Ebner, 2019). However, sensory feedback signals through sensory organs have unavoidable delays to reach the brain, ranging from tens to hundreds of milliseconds. It has been observed that the muscle activities for a smooth pursuit movement of the control subject encode both velocity and position of the target, resulting in an accurate tracking movement (Kakei et al., 2019). In contrast, the muscle activities of cerebellar patients are characterized by a marked decrease in encoding of velocity and a compensatory increase in encoding of position, resulting in a series of erratic stepwise movements. This is in favour of a contribution of the cerebellum in forward models and underlines the importance of the velocity parameters in goal directed movements. Velocity is intimately linked to timing and cerebellum is a key-node for the genesis of timing-related commands, both for single-joint movements and multi-joint movements (Hiraoka et al., 2009, Bareš et al., 2019, Manto, 2022). Impaired durations of agonist/antagonist commands are typical in cerebellar patients. Prolongation of the agonist activity with delayed antagonist can predispose to hypermetria (Fig. 2; Hallett et al., 1991).

Fig. 2.

Individual elbow flexion movements from three patients moving as fast as possible (A and D, patient 9; B, patient 3; C, patient 5). The line under the EMG of the biceps record indicates the measurement of the first agonist burst duration in that record. The first agonist burst is mildly prolonged in A and markedly prolonged in B and C. In C, the first agonist burst is fragmented. D shows the relatively rare event of a tremorous movement. From: (Hallett et al., 1991). With permission.

3. Eyeblink conditioning

McCormick and Thompson (McCormick and Thompson, 1984) were the first to report that the cerebellum is critically involved in the acquisition and retention of conditioned eyeblinks. Ever since, numerous studies have used classical eyeblink conditioning as a simple experimental model to study the contribution of the cerebellum to motor learning (Gerwig et al., 2007, Gao et al., 2012, Takehara-Nishiuchi, 2018, for reviews). Furthermore, impaired eyeblink conditioning is often considered as a neurophysiological indicator of cerebellar dysfunction.

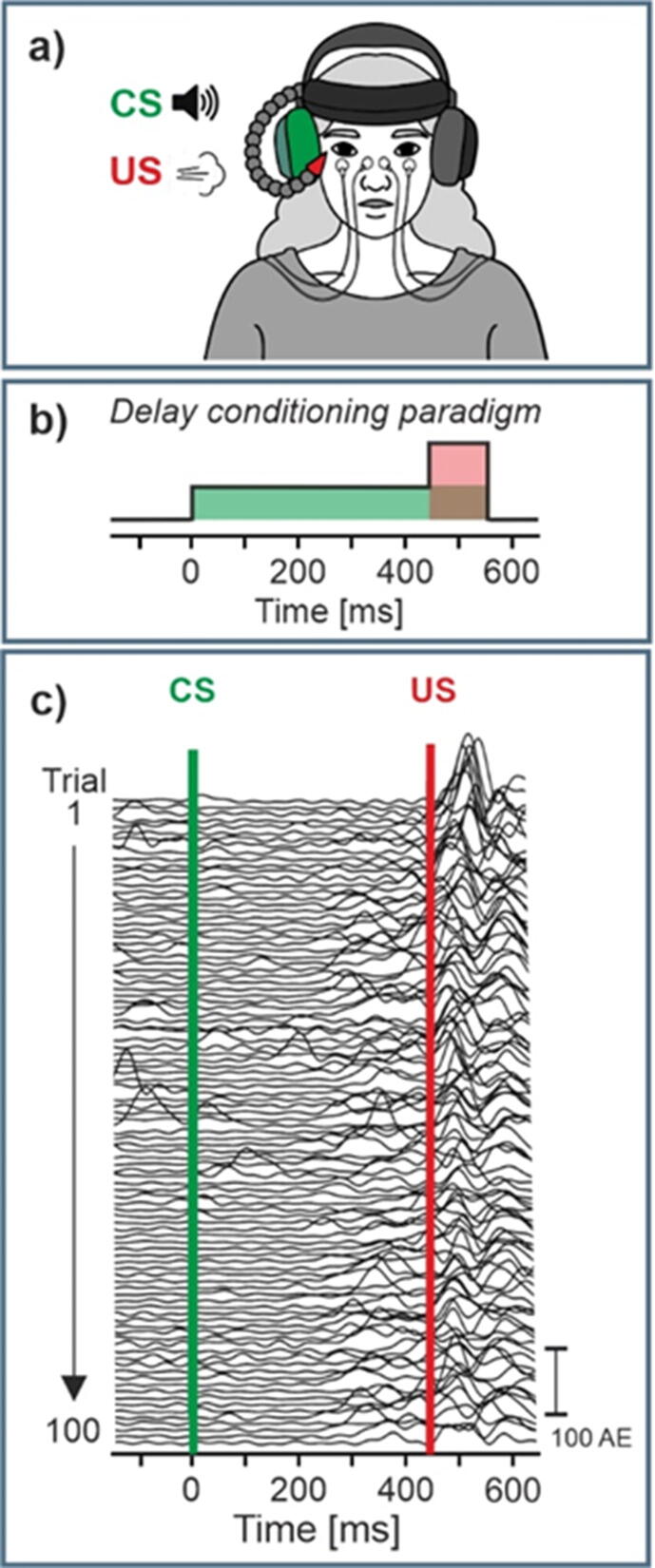

3.1. Eyeblink conditioning paradigm

In eyeblink conditioning, an initially neutral conditioned stimulus (CS), commonly a tone, is repeatedly presented with an unconditioned stimulus (US), often an air puff directed to the eye (Fig. 3a). The simplest and most frequently used paradigm is delay conditioning, in which the CS precedes the US, stays on until the US is presented and coterminates with the US (Fig. 3b). After repeated CS–US pairings participants learn that the CS predicts the occurrence of the US and close their eye after onset of the CS and prior to occurrence of the US (Fig. 3c). Unconditioned (UR) and conditioned (CR) eyeblink responses are often assessed based on surface electromyography (EMG) recordings of the orbicularis oculi muscles (Fig. 3a,c) or video recordings. A short CS-US interval is recommended, i.e., between 400 ms and 500 ms in humans, which leads to best conditioning results in healthy participants, and reduces the likelihood of voluntary eyeblink responses (but see also Rasmussen and Jirenhed, (2017)). In humans, the most robust learning parameter is the number of conditioned responses (i.e., CR incidence), followed by the learning rate (i.e., change of CR incidence across learning blocks). CR onset and other CR timing parameters give less reliable results.

Fig. 3.

Eyeblink conditioning. a) set-up; b) delay paradigm; c) eyeblink EMG recordings in an individual healthy participant; CS, US = conditioned, unconditioned stimulus, CR (%) = CR incidence, Block = 10 paired CS-US trials. We thank Greta Wippich for preparation of the illustration shown in a).

3.2. Cerebellar sites, neural circuitry and plasticity mechanisms associated with eyeblink conditioning

Cerebellar sites, neural circuitry and plasticity mechanisms underlying delay eyeblink conditioning have been studied in great detail (Gerwig et al., 2007, Gao et al., 2012, Takehara-Nishiuchi, 2018, for reviews). Human cerebellar lesions and functional brain imaging data show that lobule VI and adjacent Crus I are critically involved in the acquisition and retention of conditioned eyeblink responses, in very good accordance with animal data (Ramnani et al., 2000, Gerwig et al., 2003, Thieme et al., 2013). Cerebellar areas related to eyeblink conditioning are not restricted to lobules VI/Crus I, but also involve Crus II and VIIb although to a lesser extent (Yeo and Hesslow, 1998). Eyeblink conditioning deficits are restricted to the ipsilesional eye (Yeo et al., 1985a, Gerwig et al., 2003). Neuroimaging data, however, reveal additional cerebellar activation on the contralateral side. Learning also takes place in the cerebellar nuclei (Thürling et al., 2015). Animal data show that the interposed nucleus is of particular importance (Yeo et al., 1985b, Boele et al., 2013).

The best-known cerebellar model of eyeblink conditioning implies that the CS is conveyed to the granular cell layer via the pontine nuclei and mossy fibers (Linden, 2003). Granule cells transmit the CS signals via parallel fibers to the Purkinje cells. Purkinje cells receive US information via the inferior olive and climbing fibers. After repeated CS-US stimulation, the GABAergic Purkinje cells learn to pause to the CS, which results in less inhibition of the (excitatory) cerebellar nuclei, allowing conditioned eyeblink responses (CR) to occur. Pausing of Purkinje cells is thought to be a result of long-term depression (LTD), with the climbing fiber input depressing the synaptic transmission between parallel fibers and the Purkinje cell (Ito, 2001). Learning-related plasticity, however, is likely not limited to LTD. Long-term potentiation (LTP) at the parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse and increased excitability of Purkinje cells may also play a role, e.g., by inhibiting the levator palpebrae muscle (Freeman, 2015). Learning-related plasticity at the mossy fiber-granule cell synapses and synapses between inhibitory interneurons and their target cells (i.e., granule cells and Purkinje cells) likely also contribute (Gao et al., 2012).

3.3. Findings in ataxias and other movement disorders

Eyeblink conditioning is significantly impeded in patients with various cerebellar disorders. Among others, the ability to acquire conditioned eyeblink responses has been shown to be reduced in hereditary ataxias including spinocerebellar ataxia types 3 and 6 (SCA3, SCA6) and Friedreich’s ataxia (Timmann et al., 2005, Maas et al., 2022), in cerebellar stroke (Gerwig et al., 2003) and after tumor surgery of the cerebellum (Ernst et al., 2016). Furthermore, impaired eyeblink conditioning appears to be an early marker of cerebellar degenerative disease. Preclinical SCA3 carriers acquired significantly less conditioned eyeblink responses than controls and learning rates were significantly reduced (van Gaalen et al., 2019). Impaired eyeblink conditioning is also an indicator of cerebellar involvement in other movement disorders, in which cerebellar dysfunction is thought to contribute to pathophysiology. For example, the ability to acquire conditioned eyeblink responses is significantly reduced in patients with essential tremor compared with controls (Kronenbuerger et al., 2007). Eyeblink conditioning is largely preserved in Parkinson’s disease (Daum et al., 1996), but impaired in progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP; Sommer et al., 2001) indicating cerebellar involvement in PSP. Another example is prematurity, which is known to impede cerebellar development. Acquisition of conditioned eyeblink responses is reduced and learning rate slowed in very preterm born children and young adults, in whom focal lesions of the cerebellum has been excluded (Tran et al., 2017). Findings in other disorders are less clear. For example, initial observations of impaired eyeblink conditioning in isolated dystonia were not replicated in later studies (Sadnicka et al., 2022). Likewise, findings are mixed in patients with schizophrenia (Kent et al., 2015).

3.4. Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations which hamper the application of eyeblink conditioning as a diagnostic tool and/or a potential biomarker of cerebellar disease. First, individual variability is high already in the healthy population, which reduces its value in diagnosing cerebellar disease in individual patients. Second, there is a significant age-related decline which has been associated with an age-related reduction of cerebellar volume (Dimitrova et al., 2008). Third, there is little association between the ability to acquire conditioned responses and clinical measures of disease severity, i.e., clinical ataxia scores, reducing its value as a biomarker (Timmann et al., 2005, Maas et al., 2022). Fourth, although eyeblink conditioning is a simple motor learning paradigm, an eyeblink conditioning set-up is needed, which is usually not available in a clinical setting. A smartphone-mediated eyeblink conditioning test recently developed by Boele and colleagues (Sherry et al., 2022; https://www.blinklab.org/) may overcome this limitation and also allows multiple testing at home. The selfie flash is used as US and a tone as CS. The CR is measured based on a video recording of the face.

Finally, although delay eyeblink conditioning is strongly cerebellar-dependent and occurs in decerebrate animal preparations (Yeo and Hesslow, 1998), cerebral areas have a modulatory role. The medial prefrontal cortex, cingulate, motor cortex, basal ganglia and hippocampus have been shown to be involved (Ramnani et al., 2000, Gerwig et al., 2007). These areas have known structural and functional connections with the cerebellum (Kipping et al., 2013, Pisano et al., 2021). Thus, although abnormalities in eyeblink conditioning strongly suggest cerebellar involvement, it cannot be excluded that extracerebellar pathology contributes.

4. Sensorimotor adaptation

4.1. Sensorimotor adaptation

Our ability to adapt to environmental changes is in the core of human existence. Sensorimotor adaptation is a unique capability of the brain to systematically adjust to incoming stimuli from the surroundings and appropriately adjust motor output using error-based mechanisms. For instance, when a tennis player strikes a ball across the court to her opponent, she must take different parameters into account such as the angle and range of motion but also the height of the net, the location of the opponent, the wind, etc. During initial strikes the player incorporates these different parameters by minimizing an error signal between a predicted movement and the actual sensory feedback to create an optimal strike. This error is referred to as sensory prediction error (SPE). Evidence has led researchers to suggest that the cerebellum plays an important role in this process by predicting the consequences of motor commands using forward internal models (Bastian, 2006, Schlerf et al., 2012, Tseng et al., 2007, Wolpert et al., 1998).

To study sensorimotor adaptation, different experimental paradigms have been employed. Some of the common ones include force-field adaptation - a task in which a robotic arm is subjected to forces during movements, locomotor adaptation using a split-belt treadmill, prism adaptation – a task which includes a visual displacement by a prism, and the very popular visuomotor adaptation which includes the displacement of visual feedback on a computer screen. Adaptation is usually assessed as the number of trials required for a subject to adjust their movement to the new sensory input.

Sensorimotor adaptation is complex and operates different levels of learning mechanisms. Studies show that both an implicit, automatic component as well as an explicit, strategic component may be involved to different degrees in solving sensorimotor adaptation (Mazzoni and Krakauer, 2006, Taylor et al., 2014, Taylor and Ivry, 2011). Possibly, the implicit component of sensorimotor adaptation acts to minimize proprioceptive error, i.e., the distance between the perceived hand position and the actual goal (Tsay et al., 2022).

4.2. Cerebellar contribution to sensorimotor adaptation: Clinical evidence

Especially patients suffering from cerebellar stroke and cerebellar ataxia demonstrate specific deficits in sensorimotor adaptation (see mini review by Tzvi et al., 2021). Studies have shown evidence that both the implicit component of sensorimotor adaptation as well as the explicit strategic processing may be affected by cerebellar pathology (Criscimagna-Hemminger et al., 2010, Taylor et al., 2010, Tseng et al., 2007). Specifically, evidence suggests that cerebellar degeneration patients show a marked deficit in discovering a strategy to solve a visual perturbation but have no trouble in applying a re-aiming strategy when explicitly instructed to do so (Wong et al., 2019). This evidence implies a multi-faceted contribution of the cerebellum to sensorimotor adaptation. Visuomotor adaptation deficits in other neurological disorders may therefore point to a cerebellar role in the underlying pathology. For instance, a visuomotor adaptation study in essential tremor patients found specific impairments in adaptation to a visual perturbation which were not associated with an inability to perform goal-directed movements, thus corroborating a cerebellar dysfunction hypothesis underlying ET (Hanajaima et al., 2016, Bindel et al., 2022). On the other hand, intact visuomotor adaptation found in patients with cervical dystonia may provide evidence for deficits along the cortico-basal-ganglia loop rather than cerebellar involvement in dystonia (Loens et al., 2021). Nonetheless, due to the variable extent of cerebellar involvement in clinical populations, such studies can provide only limited evidence to involvement of the cerebellum in the process of visuomotor adaptation.

4.3. Cerebellar contribution to sensorimotor adaptation: Neurophysiological evidence

Functional imaging studies in humans have the possibility to shed more light on dynamics of sensorimotor adaptation in the cerebellum. While early prism adaptation invoked activity within posterior cerebellar cortex (lobules VII and IX) and ventro-caudal dentate nucleus, late adaptation led to increase in lobule VI activity (Küper et al., 2014). Evidence from a visuomotor adaptation study suggests that implicit adaptation decreases cerebellar crus II and lobule VI activity, and rebounds when the perturbation is suddenly removed. During this time, referred to as de-adaptation, connectivity from cerebellum to dorsolateral premotor cortex was modulated, suggesting that these dynamic interactions contribute to successful adaptation (Tzvi et al., 2020). A pioneering EEG study, designed to capture neurophysiological activity from the cerebellum non-invasively, further corroborated these results and demonstrated that cerebellar theta (4–8 Hz) oscillations may drive dynamic changes in the cerebellum during visuomotor adaptation, as well as critical interactions with premotor cortex (Tzvi et al., 2022, Tzvi et al., 2022). Specifically, increased theta power was associated with better adaptation. Interestingly, a recent MRI study investigating GABA changes in the cerebellum with adaptation and found decreased GABA in right cerebellar nuclei, which was associated with early adaptation, when participants used the right hand. In other words, greater ipsilateral early GABA decrease in the cerebellar nuclei led to better adaptation (Nettekoven et al., 2022).

4.4. Cerebellar contribution to sensorimotor adaptation: Neuromodulation evidence

Neuromodulation methods could provide additional causal evidence for the effect of dynamic changes in cerebellar activity during active sensorimotor adaptation. Non-invasive electric stimulation of the cerebellum is an example of a rather easy to use approach, which can be simply combined with online visuomotor adaptation. Indeed, numerous studies found evidence for improved visuomotor adaptation following transcranial direct current stimulation (TDCS) (Block and Celnik, 2013, Galea et al., 2011, Herzfeld et al., 2014, Leow et al., 2017, Weightman et al., 2020, Weightman et al., 2021).

However, other studies attempting to replicate the beneficial effect of cerebellar TDCS on visuomotor adaptation were unsuccessful (Panouillères et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2022). For instance, one study examined 192 subjects in seven different visuomotor adaptation experiments with varying task parameters and stimulation timing and found no significant differences to sham (Placebo) stimulation (Jalali et al., 2017, Hulst et al., 2017). Similarly, another study examined the effect of anodal cerebellar TDCS on both visuomotor adaptation and force-field adaptation in 120 young and older healthy adults and found no significant effects (Mamlins et al., 2019). Thus, despite the great potential of cerebellar electric stimulation to causally link cerebellar activity with visuomotor adaptation mechanisms, it may not be specific enough to counter-act the strong inter-individual variability across subjects that may relate to differential contribution of implicit and explicit components.

4.5. Conclusions and future aspects

Research on cerebellar contribution to visuomotor adaptation mechanisms has taken a great leap in recent years due to development of conceptual aspects as well as technological methods to tap into neurophysiological correlates of online visuomotor adaptation. Future studies may tap into the potential of non-invasive cerebellar stimulation to study the causal role of the cerebellum on visuomotor adaptation processes.

5. Physiology measurements in patients with cerebellar ataxia: Recent findings on EEG/MEG

While cerebellar degeneration is a common imaging and pathological feature in patients with cerebellar ataxia, neuronal firing abnormalities may occur before neurodegeneration. Therefore, physiological recordings may provide clues to the overall functional status of the cerebellum. In addition to the direct measurement of cerebellar physiology, physiological alterations in the cerebral cortex are also found in patients with cerebellar ataxia, demonstrating a network dysfunction. The techniques used are mainly electroencephalogram (EEG) and magnetoencephalogram (MEG), and we will review recent literature of brain physiology recordings in patients with cerebellar ataxia.

Generally speaking, EEG and MEG studies of cerebellar ataxia often utilize the techniques of source localization and functional connectivity analysis (Kumar et al., 2022). Naeije et al. used MEG to study intrinsic functional brain network in patients with Friedreich ataxia and found 6 major resting state networks: default mode, sensory motor, language, visual, ventral, and dorsal attention networks, which all connect to the cerebellum. Additionally, they found that the abnormalities of cerebellar network could be associated with age of onset of ataxia, demonstrating that cerebellar physiology may have a predictive value of disease onset (Naeije et al., 2020). Another MEG study also found that Friedreich’s ataxia patients have reduced coupling between movement kinematics and MEG signals, which can be related to the proprioceptive impairment (Marty et al., 2019). Not only can the physiology techniques be used to track the disease course, they can also be applied to test target engagement for neuromodulation. Song et al. studied cerebello-frontal connectivity dynamics with EEG in patients with multiple system atrophy- cerebellar type (MSA-C) to test the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the cerebellum (Song et al., 2020). The results of the stimulation showed that individuals who received rTMS had significantly improved ataxia symptoms, along with increased cerebello-frontal connectivity, using time-varying EEG network patterns. Therefore, this study provides a strong argument that improvement of ataxia symptoms is through the mechanism of altering the cerebellar circuit physiology.

EEG has also been implemented to study the physiological changes in the cerebral cortex in patients with cerebellar ataxia since the pathology of ataxic disorders is often not restricted to the cerebellum. In addition, there could be compensatory network changes in the cerebral cortex in response to cerebellar dysfunction. Peterburs et al. studied task-specific EEG signal alterations with 28-channel recordings and found that patients with various causes of cerebellar ataxia have reduced error-related negativity, an EEG signal of event-related potentials, in anti-saccadic tasks ((Peterburs et al., 2015); see also Section 2.1). In addition to eye movements, event related potentials associated with speech have been studied in cerebellar ataxia, using event related synchronization (ERS)/ event related desynchronization (ERD) analysis. Li et al. investigated event related potentials in the vocal production in patients with spinocerebellar ataxias. The vocal dysfunction in these patients corresponds to decreased cortical activity in temporal-parietal regions by source analysis (Li et al., 2019). Finally, Verleger et al. investigated event related potentials using EEG in patients with cerebellar ataxia while performing coordination motor tasks (Verleger et al., 1999). Patients with cerebellar ataxia demonstrated a decrease in cerebral cortical EEG potentials during preparation and execution of movements when compared to controls. These studies collectively demonstrated that event related potentials related to eye movement, voice, and coordination tasks can be a useful tool to study brain physiology in cerebellar ataxia.

In addition to motor tasks, Yamaguchi et al. further studied event related evoked potentials in visuospatial attention shift in patients with cerebellar ataxia. In these patients, they observed a reduced late negative deflection in the event related potentials (Yamaguchi et al., 1998). Therefore, event related potentials alterations can be observed in ataxic patients performing cognitive tasks.

Utilizing ERD/ ERS analysis, Visani et al. assessed EEG signals in patients with spinocerebellar ataxias when performing a Go/No-go task. The main finding is that patients with spinocerebellar ataxia have a defective ERD lateralization in the cortical EEG recording. The defective responses in alpha and beta ERD/ERS analysis may imply impaired cerebellar modulation of the motor cortex (Visani et al., 2019). Aoh et al. studied patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 using EEG and found a decrease of ERS at the frequency of 20–30 Hz (Aoh et al., 2019). In summary, both studies highlight the cerebellar modulation of cortical excitability, which can be monitored by EEG.

The coherence of EEG in the sensorimotor cortex and electromyography (EMG) recordings in the limbs was also utilized to study patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. They found that symptomatic patients and pre-symptomatic patients who carry pathological ATXN2 expansions both have reduction of EEG-EMG coherence (Velázquez-Pérez et al., 2017a, Velázquez-Pérez et al., 2017b, Ruiz-Gonzalez et al., 2020). These findings may reflect corticospinal tract dysfunction in these patients.

While the above studies often use the techniques of traditional EEG methods, covering mostly cortical area with some cerebellar coverage, recent studies have utilized EEG specifically targeting the cerebellar area (Kumar et al., 2022). For example, a recent study by Govender et al. demonstrated cerebellar evoked potential responses in healthy subjects in responses to impulsive accelerations to mastoid and trunks (Govender et al., 2022). In addition, cerebellar EEG has been applied to study essential tremor patients demonstrating enhanced oscillatory activity in the cerebellum (Pan et al., 2020, Wong et al., 2022). These techniques have not yet been applied to the cerebellar ataxia, which could be a promising future direction to direct probe cerebellar physiology in ataxia.

In summary, physiological techniques have recently been applied to study patients with cerebellar ataxia with EEG and MEG. While studies are relatively sparse, the exciting results demonstrate a variety of physiological alterations that can be detected either at the rest state or while performing various movements or cognitive tasks. These studies highlight the intricate connections between the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex, and these physiological characteristics could serve as markers to facilitate novel therapeutic development in cerebellar ataxia.

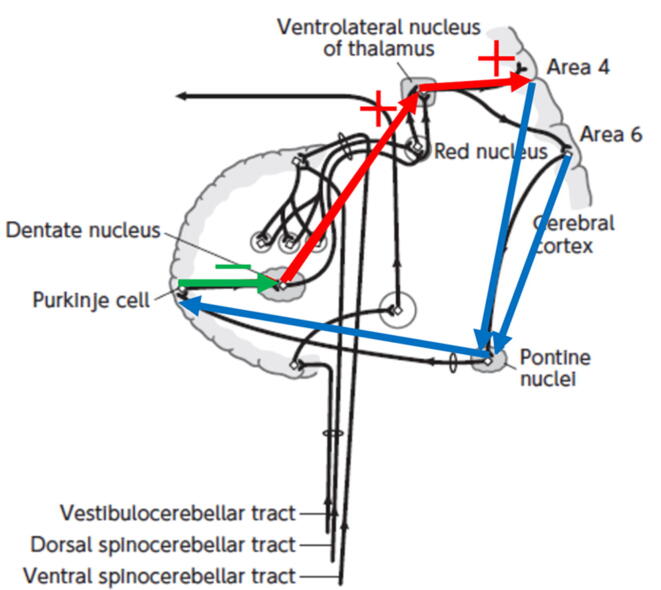

6. Cerebellum-motor cortex inhibition (CBI)

The cerebellum plays critical roles in motor (Allen and Tsukahara, 1974) and non-motor functions (Schmahmann, 2019) by modulating the related cortices through the cerebro-cerebellar loop (the fronto-ponto-cerebello-thalamo-cortical loop; Fig. 4). The function of this loop had been intensively studied in animals, and it is now possible to functionally investigate it in humans with transcranial noninvasive brain stimulation (NBS) techniques. Motor cortical modulation by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over the cerebellum can be evaluated in humans using motor evoked potentials (MEPs) as a motor cortical excitability marker. This cerebellum-motor cortex modulation is usually termed cerebellum-motor cortex inhibition (CBI). We here briefly describe the CBI, possible mechanism underlying the inhibition, several limitations of CBI, and some future applications.

Fig. 4.

Anatomical connections of the cerebellar cortex and nuclei. Blue lines: cerebellar afferent pathways. Green line: connection within the cerebellum. Red lines: cerebellar efferent pathways. +: facilitatory connection. -: inhibitory connection. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

6.1. Cerebellum-motor cortex inhibition (CBI)

To evaluate the cerebellum-motor cortical connection in humans, Ugawa et al. first attempted to study motor cortical modulation evoked by cerebellar stimulation using high voltage electrical stimulation over the cerebellum (Ugawa et al., 1991), and later proposed the same analysis using TMS (Ugawa et al., 1995). In these examinations, they used a randomized conditioning-test design in which the control trials (TMS over the motor cortex (M1) given alone) and conditioned trials (both the cerebellar stimulation and motor cortical stimulation given at several intervals) were randomly intermixed in the same session. The conditioned MEPs were smaller than the control MEPs at intervals of 5 to 8 ms.

6.2. The mechanism of CBI

The effective interstimulus interval between two stimulations, appropriate location of the cerebellar stimulation, and efficient polarity of electrical stimulation in normal subjects supported the idea that CBI was produced by the cerebellum-M1 connection. However, there was no direct evidence for the cerebellar involvement in CBI because the cerebellar stimulation procedures would also activate sensory fibers in the skin, neck muscles, and other structures in the back of the head, and should also be associated with the coil sound in addition to the cerebellar activation. To exclude the above confounding factors, CBI studies of patients with many kinds of ataxia and non-ataxic patients (Ugawa et al., 1994, Ugawa et al., 1997) must support the above assumption even though it is still not direct evidence.

CBI was abnormally reduced in patients in whom the cerebellar cortex was mainly affected, such as spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs; SCA 6 or SCA 31), cerebellar cortical atrophy (CCA), cerebellar-type multiple system atrophy (MSA-C), cerebellar stroke, cerebellitis, paraneoplastic CCA, and intoxication from antiepileptic drugs (Ugawa et al., 1994, Ugawa et al., 1997). The involvement of the dentate nucleus or superior cerebellar peduncle in dentatorubral–pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) and Wilson’s disease also led to reduced CBI (Ugawa et al., 1997). In contrast, ataxic patients with lesions in cerebellar afferent pathways (pontine or middle cerebellar peduncular lesions) had normal CBI, even though the patients showed definite clinical cerebellar ataxic motor symptoms (Ugawa et al., 1997). Normal CBI was evoked in patients with non-cerebellar ataxia, such as sensory ataxia, Miller Fisher syndrome, and hypothyroidism (Ugawa et al., 1994, Ugawa et al., 1997). These results suggested that CBI involves activation of the cerebellar cortex and conduction to motor cortex via the dentate nucleus, superior cerebellar peduncle, and the cerebellar thalamus. The above patient studies were summarized in two review papers (Groiss et al., 2013, Grimaldi et al., 2014).

6.3. Applications of CBI

Following these initial studies, CBI has been used in three ways: 1) to investigate cerebellar involvement in disorders with no primary cerebellar pathology, 2) to evaluate the degree of cerebellar involvement in ataxic patients, and 3) to show cerebellar functional changes in research of normal subjects or in treatments with cerebellar modulation.

CBI revealed cerebellar involvement in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) in whom cerebellar clinical ataxic motor signs were masked by rigidity (Shirota et al., 2010) and in patients with essential tremor (Hanajima et al., 2016). CBI showed an inverse association between cerebellothalamocortical tract integrity (the degree of CBI) and ataxia severity in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (SCA3) (Mass et al., 2021). CBI was used to objectively evaluate the cerebellar functional changes induced by transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) (Batsikadze et al., 2019)or repetitive TMS (rTMS) over the cerebellum (Dale et al., 2019).

6.4. Unresolved issues and limitations

The above simplest proposed mechanism underlying CBI has been challenged in various aspects, which have been summarized in review papers (Fernandez et al., 2018, Fernandez et al., 2018, Manto et al., 2022).

Intensity: The intensity of cerebellar stimulation is recommended to be set at 5––10% below the threshold for active target muscle in brainstem stimulation (Ugawa, 2009): (Fisher et al., 2009), but it is often intolerable (Fernandez et al., 2018, Fernandez et al., 2018).

Coil to use: Hardwick et al (Hardwick et al., 2014) found that CBI could only be evoked reliably with large coils and not with the conventional flat figure-of-eight coils, a fact confirmed later by Spampinato et al. (2020b). They estimated the distance from the scalp to lobules V and VII connecting with M1 to be 3 – 3.5 cm, which is twice as long as the distance from the scalp to M1. The ideal coil for cerebellar stimulation is a double-cone coil, but the tolerability is another factor to influence the coil selection. Cerebellar stimulation with a double cone coil is often intolerable to the subjects, especially in younger subjects (Rurak et al., 2021).

Purkinje cell: The cerebellar surface is highly convoluted such that alignment of the Purkinje cells can be at all angles to the direction of the induced currents in cerebellum. Is it the case that Purkinje cells for the motor cortical modulation is readily activated with NBS?

Reliability, variability: Mooney et al (Mooney et al., 2021) showed a small intra- or inter-day variability of CBI studied with a double cone coil, which demonstrated that the CBI has fair to good relative reliability in healthy individuals. The CBI could be used for tracking changes in cerebellar-M1 connectivity in human research fields.

Age effect: The age dependency of CBI has been recently reported (Rurak et al., 2022; Mooney et al., 2022). Less CBI was elicited in older subjects than in younger subjects when using a figure of eight coil (Rurak et al., 2022) or a double cone coil (Mooney et al., 2022) for the cerebellar stimulation. We need normal values of CBI for specific age ranges.

Direct and indirect effects on M1: One recent paper proposed that two independent cerebello-M1 pathways may contribute to motor cortical inhibition with different timings (Spampinato et al., 2020a). We should consider this possibility to evaluate the experimental results.

Delayed cerebellar inhibition (delayed CBI): One critical challenge of CBI is the delayed cerebellar inhibition due to prolonged conduction time from the cerebellum to M1. The delayed real cerebellar inhibition may not be able to be differentiated from the inhibition produced by non-cerebellar structures activation at delayed intervals or the indirect effects on M1 shown above (Spampinato et al., 2020a).

6.5. Future application

Even with above several unknown issues or limitations, CBI has been used for an objective marker of cerebellar function in the human research fields and treatments of several disorders mainly because it is a simple and clear electrophysiological method for cerebellar functional evaluation in humans. We will have solutions of the above issues in the future.

7. Gait ataxia and other gait disturbances

7.1. Ataxic gait

Gait ataxia is the most noticeable motor symptom of cerebellar and cerebellar pathway injury (Manto et al., 2018, Manto et al., 2020). It has traditionally been described as a clumsy, irregular, and wide-based walk, similar to alcoholics' “drunken gait” (Holmes, 1939). Researchers have extensively described ataxic gait in a variety of kinematic, kinetic, and sEMG abnormalities over the last several decades, leading to a characterization of gait behavior in a number of inherited and acquired cerebellar disorders (Bodranghien et al., 2016, Cabaraux et al., 2022, Cabaraux et al., 2020, Ilg et al., 2018, Palliyath et al., 1998, Serrao et al., 2018a).

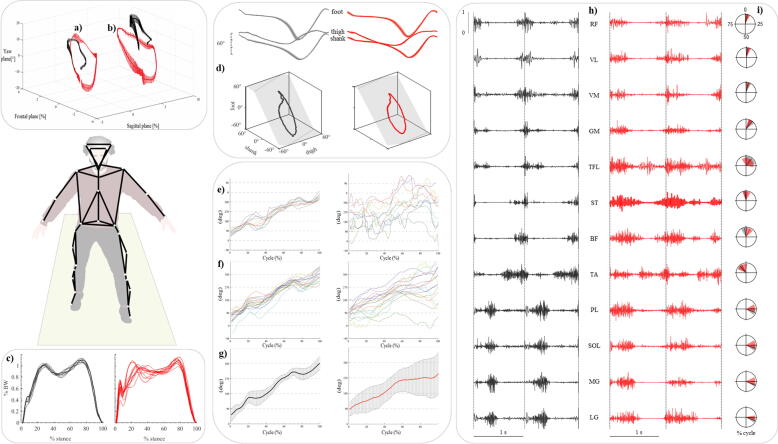

Although several time-distance and joint kinematic parameters abnormalities have been reported in patients with ataxia (Bodranghien et al., 2016, Cabaraux et al., 2022, Ilg et al., 2018), increased step width, reduced ankle joint range of motion [ROM] and increased gait variability seem to differentiate patients with cerebellar ataxia from healthy subjects and those with other neurological gait disturbances (Serrao et al., 2018b). Fig. 5 illustrates exemplative abnormalities of gait.

Fig. 5.

a) Head displacement during gait cycle in a subject with cerebellar ataxia (red) and a healthy control (black) (data from (Conte et al., 2014); b) trunk displacement during gait cycle in a subject with cerebellar ataxia (red) and a healthy control (black); c) ground reaction force during the stance phase in a subject with cerebellar ataxia (red) and a healthy control (black). Traces represent single gait cycles (data from (Martino et al., 2014); d) planar covariation of elevation angles in a subject with cerebellar ataxia (red) and a healthy control (black): ensemble-averaged (across strides) thigh, shank, and foot elevation angles (means ± SD) plotted vs. normalized gait cycle and corresponding 3-dimensional (3D) gait loops and interpolation planes. Gait loops are obtained by plotting the thigh waveform vs. the shank and foot waveforms. Gait cycle paths progress counterclockwise in time, with heel strike and toe-off phases approximately corresponding to the top and bottom of the loops, respectively (data from (Martino et al., 2014); e) coordination between trunk and lower limb calculated using the continuous relative phase curves (CRP) method relative to 10 gait trials in a healthy control (left) and a subject with cerebellar ataxia (right); f) mean CRP curves of 16 healthy controls (left) and 16 subjects with cerebellar ataxia (right); g) time series of the mean CRP curves and their SD in a group of 16 healthy controls (black) and 16 subjects with cerebellar ataxia (red), (data from Caliandro et al. 2014); h) electromyographic activity of 12 lower limb muscles in a subject with cerebellar ataxia (red) and an healthy control (black) (data from (Martino et al., 2014); i) center of activation (CoA) over the gait cycle (progression: clockwise) of leg muscles electromyographic activity in a group of 19 subjects with cerebellar ataxia (red) and 20 healthy controls (black), (data from (Martino et al., 2014). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

Other well recognized gait abnormalities include the lack of intra-limb inter-joint and inter-segmental coordination (Caliandro et al., 2019, Mari et al., 2014, Serrao et al., 2012), impaired foot ground placement, loss of trunk control (Caliandro et al., 2019, Castiglia et al., 2022b, Chini et al., 2017, Conte et al., 2014, Martino et al., 2014), and abnormal spatio-temporal lower limb muscle activation (Fiori et al., 2020, Mari et al., 2014, Martino et al., 2014).

Some of these gait abnormalities have been shown to be highly sensitive to the type of locomotion tasks (Conte et al., 2012, Serrao et al., 2013a, Serrao et al., 2013b, Serrao and Conte, 2018), disease severity (Ilg et al., 2020, Ilg et al., 2007, Schniepp et al., 2016, Serrao et al., 2012), disease progression (Serrao et al., 2017a), specific anatomical lesions (Ilg et al., 2007, Manto et al., 2018), as well as to the treatment-induced improvements (Ilg et al., 2010, Ilg et al., 2009, Serrao et al., 2019a, Serrao et al., 2019b).

Some ataxic gait features, such as the widened base of support, which is the most recognizable at clinical inspection, are typically an expression of compensatory strategies used by patients to cope with balance while walking. Other gait features seem to be more strictly related to the primary deficit linked to the cerebellum damage or degeneration. For instance, walking with a wider base is a usual compensatory mechanism aimed at increasing the margin of stability by moving the center of gravity far from the foot border in the medio-lateral direction (Serrao et al., 2017a, Serrao et al., 2017b, Serrao et al., 2012). Other safety strategies used by patients with ataxia include increasing joint muscle coactivation to stiffen the joint [e.g. “ankle strategy” in the early stages], and thus better control the acceleration of the center of mass as well as compensate for hypotonia (Mari et al., 2014, Martino et al., 2015, Martino et al., 2014), and displacing the upper body forwardly [e.g. head and trunk] to increase the distance between the CoM and the posterior margin of the foot in the posterior-anterior direction, as if they prefer to risk a forward fall rather than a backward one in a visual control perspective (Conte et al., 2014, Serrao et al., 2013a, Serrao et al., 2013b). They also increase the contralateral arm-foot distance (Serrao et al., 2013a, Serrao et al., 2013b) to likely deal with the overall stability.

Conversely, the primary deficit at the base of the ataxic gait, which is less intuitively recognizable during clinical inspection, is reflected by the lack of joint coordination that results in abnormal intra-limb joint and upper and lower body segments coupling during walking (Caliandro et al., 2017, Ilg et al., 2007, Serrao et al., 2012). This reveals the inability of the cerebellum to process multi-sensory features and provide an internal model as a “error-correction mechanism” (Cabaraux et al., 2020, Manto, 2017, Manto et al., 2018). Recent studies on gait ataxia have also confirmed the presence of abnormal recruitment of lower limb muscles, as previously observed in arm muscles (Hallett et al., 1975), with increased peak and magnitude values and an abnormal timing shift of single, antagonist or synergic muscles. As a result, irregular limb movements with incorrect foot positioning, abnormal transient at heel strike, gait variability, knee and ankle joint kinematics, and abnormal force production during the push - off within the single support phase have been observed (Conte et al., 2017, Mari et al., 2014, Martino et al., 2014).

7.2. Parkinsonian gait

Gait disorder represents one of the most disabling features in Parkinson’s disease (Morris et al., 2001, Morris et al., 1994). Parkinsonian gait is associated with postural abnormalities, increases the risk of falling, affects patients' independence and quality of life, and worsens as the disease progresses from the mildest to the most severe phases (Mirelman et al., 2019).

Aside from the typical shorter step length and slower gait described at clinical inspection, studies on 3D gait analysis have described the gait abnormalities in time-distance parameters such as cadence, stance duration, swing duration, double support duration, spatial and temporal asymmetry, joint kinematic and kinetic parameters including hip, knee, ankle, ROMs, and torques, trunk acceleration, arm swing, and more (Castiglia et al., 2022a, Castiglia et al., 2021, Mirelman et al., 2019, Morris et al., 2005, Serrao et al., 2019a, Serrao et al., 2019b, Serrao et al., 2018a, Serrao et al., 2015, Sofuwa et al., 2005, Vieregge et al., 1997). These abnormal gait parameters correlate with clinical outcomes and are amenable to pharmacological, surgical, and rehabilitation treatments (Castiglia et al., 2022a, Mirelman et al., 2019, Pistacchi et al., 2017, Serrao et al., 2019a, Serrao et al., 2019b, Serrao et al., 2015, Vieregge et al., 1997).

Some parkinsonian gait traits have been shown to be detectable years before PD diagnosis (Del Din et al., 2019). Particularly, higher step time variability and asymmetry of all gait metrics are connected to a shorter time to PD diagnosis, and a considerably slower gait speed occurs 4 years before PD diagnosis (Del Din et al., 2019).

In the early stages, people with PD show slower walk, shortened step length with reduced arm oscillations, and increased step length asymmetry compared with age-matched healthy adults (Mirelman et al., 2019, Pistacchi et al., 2017, Serrao et al., 2015). Range of motion of the hip, knee, and ankle joints and upper body movements begin to diminish during linear walking (Djurić-Jovičić et al., 2017, Mirelman et al., 2019, Pistacchi et al., 2017, Serrao et al., 2019a, Serrao et al., 2019b) , gait initiation, gait termination, and turning (Carpinella et al., 2007, Crenna et al., 2007, Serrao et al., 2015).

In the middle and severe stages of the disease most spatiotemporal characteristics are affected, and the increase in cadence is more pronounced. Asymmetry may be lessened by the bilateral manifestation of abnormalities in joint lower limb kinematics and kinetics (Albani et al., 2014, Galna et al., 2015, Serrao et al., 2019a, Serrao et al., 2018a). The magnitude of arm swing is reduced bilaterally (Baron et al., 2018, Mirelman et al., 2016), which is concurrent with a reduction of axial rotation (Castiglia et al., 2021, Serrao et al., 2019a) and turning defragmentation [i.e., turning en block] (Mellone et al., 2016, Son et al., 2022). Gait initiation problems, freezing of gait, festination and worsening of postural abnormalities eventually appear, resulting in an increased risk of falling during these stages (Hallett, 2008, Lord et al., 2020, Palmerini et al., 2017, Spildooren et al., 2019).

Recently, machine learning techniques have made it possible to reduce the dimensionality of the gait variables to be considered in the assessment of gait impairment in people with PD (Trabassi et al., 2022, Varrecchia et al., 2021). This has revealed that two features [reduced knee ROM and trunk rotation] can distinguish the gait of people with Parkinson's disease from that of healthy subjects, regardless of gait speed and H-Y stages. Additionally, two combinations of four features [walking speed and hip, knee, and ankle RoMs; walking speed and hip, knee, and trunk rotation RoMs] are the minimum set of gait parameters able to distinguish H-Y stage from one another (Varrecchia et al., 2021).

7.3. Spastic gait

Lesions in the corticospinal (and dorsal reticulospinal) tract can occur unilaterally or bilaterally and result in spastic gaits. Stroke is the most frequent unilateral cause in adults and is usually responsible for hemiparetic gait. Among many other conditions, hereditary paraplegia, cervical spondylotic myelopathy, and multiple sclerosis are some of the common causes of bilateral spastic gait [spastic paraparesis] in adults. In-depth research on the profile of post-stroke gait has been conducted utilizing quantitative 3D approaches, such as joint kinematics and kinetics, electromyography [EMG], and temporo-spatial gait characteristics (Balaban and Tok, 2014). Spastic gait in stroke is a typical example of asymmetric gait, such as prosthetic gait and gait after total hip arthroplasty (Ippolito et al., 2021, Varrecchia et al., 2019) and reflects both the increased muscle tone and decreased strength of the affected side. Instead of the healthy subjects' well-controlled intralimb and interlimb coordination, pathological synergies in patients with stroke cause mass limb movement patterns, which call for compensatory adjustments to the pelvis and nonparetic limb (Van Criekinge et al., 2020, Israely et al., 2018). The main characteristics are represented by reduced walking velocity (Goldie et al., 1996), increased stride time and reduced cadence (Bohannon, 1987), increased double support time on the unaffected lower extremity (Brandstater et al., 1983), prolonged paretic swing time and/or a prolonged nonparetic stance time compared with the contralateral limb (Titianova et al., 2003). Reduced joint moments, primarily at the knee and ankle joints, can be observed in both limbs when compared to healthy controls, and smaller on the paretic side when compared to the non-paretic side (Bensoussan et al., 2006, Titianova et al., 2003) , as well as abnormal ROMs that appear to be greater in the paretic ankle than the sound leg, particularly during the swing phase, due to sural triceps spasticity (Bensoussan et al., 2006).

Additionally, during stance, the non-paretic limb shows increased coactivation of the hamstrings and quadriceps as well as a decrease in the magnitude of the EMG, premature onset, prolonged duration, and altered peaks of activity of the paretic limb muscles (Daly et al., 2011, Higginson et al., 2006, Lodha et al., 2017).

As regard the bilateral lesions of the corticospinal tracts, recent studies on 3D gait analysis have thoroughly investigated the gait of patients with hereditary spastic paraparesis (Martino et al., 2019, Martino et al., 2018, Rinaldi et al., 2017, Serrao et al., 2016). Three gait patterns were categorized according to the hip, knee and ankle joint kinematic behavior, degrees of spasticity, and disease severity (Serrao et al., 2016). The gait pattern of the most mildly affected patients was the closest to that of healthy controls in terms of time-distance parameters and it was characterized by increased hip joint ROM. Interestingly, this subgroup of patients exhibited increased trunk ROM in all three spatial planes [which was also seen in the more disabled groups], suggesting that the trunk compensatory mechanisms are important biomechanical features in paraparetic gait since the early phase of the disease.

The gait pattern of the moderately affected patients was characterized by a reduced gait speed, decreased knee and ankle joint ROMs, with hip joint ROM values close to healthy controls. Conversely, the gait pattern of the most severely affected patients was characterized by reduced ROMs of all three lower limb joints, increased values of ROM for pelvis tilt and hip extensor torques during the first double support subphase, reduced gait speed, stance, and second double support durations, and the shorter swing duration and step length (Serrao et al., 2016).

Studies on surface muscle activation have revealed increased coactivation of the antagonist muscles around the knee and ankle joints (Rinaldi et al., 2017), and increased spatial and temporal muscle activation, primarily of the muscles innervated from the sacral spinal segments in subjects at more advanced stages (Martino et al., 2019, Martino et al., 2018), reflecting the lack of selectivity in motoneuron recruitment from caudal to rostral segments due to the degeneration of the corticospinal tract (Martino et al., 2019).

7.4. Steppage gait

Steppage gait is a common gait issue associated with peripheral nervous system disorders, including polyneuropathies of various etiologies. Clinical symptoms often include symmetrical weakening and atrophy of distal muscles, mainly in the lower limbs (Harding and Thomas, 1980). At clinical inspection the gait is characterized by foot drop, which results in a reduced ability to lift the foot off the ground during the swing phase, with compensation achieved by increased knee and hip flexion (Sabir and Lyttle, 1984). Three-dimensional gait analysis studies on patients with hereditary polyneuropathies [e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth] (Don et al., 2007, Ferrarin et al., 2013, Ferrarin et al., 2012) have allowed to broadly describe the steppage gait and better understand the complex interaction between muscle deficit, structural alterations, biomechanical dysfunctions, and compensatory adjustments occurring during the course of the disease. Two patterns of steppage gait have been identified according to the dorsal flexor muscles strength deficit [foot drop] or to both the dorsal flexor and plantar flexor muscles strength deficit [foot drop/ push-off deficit] (Don et al., 2007). During the swing phase, these patients often exhibit the steppage gait's characteristic pattern with decreased dorsiflexion [foot drop] and compensatory increases in knee and hip flexion to prevent tripping over their toes on the ground. They augment the passive ankle dorsiflexion motion and postpone the activation of the plantar flexor muscles during mid-stance to sustain body development, which is also achieved by a consensual increase in hip extension and a greater knee torque output during stance. Patients also increase plantar flexor torque and excursion during the push-off subphase to provide energy for the foot-off. As a result, despite the reduced gait speed, the compensating mechanisms used during the stance phase allow them to keep a step length within normal limits (Don et al., 2007).

In the second gait pattern, patients exhibit not only the same foot drop-related ankle alterations during the swing phase, but also the impacts of plantar flexor failure, which includes a significant plantar flexion torque and ROM decrease. During the swing phase, hip and knee flexion are reduced rather than enhanced, as in the first gait pattern, and the primary mechanisms employed to prevent tripping are greater hip abduction and pelvic elevation achieved through prolonged gluteus medius activation (Don et al., 2007).

7.5. Dystonic and choreic gait

Diseases associated with involuntary movement abnormalities have a significant impact on walking. At clinical inspection, patients affected by dystonia, chorea, as well as choreoathetosis show an irregular gait with involuntary movement and abnormal postures involving head, neck, arms, legs, and trunk (Goetz, 2000, Vale and Cardoso, 2015).

Dystonia is defined as persistent or intermittent muscle contractions resulting in abnormal, frequently repetitive, movements, postures, or both. Dystonic movements are typically patterned, twisting, and may be tremulous (Albanese et al., 2013). Dystonic gait can greatly vary depending on the forms of dystonia, which include primary, secondary, generalized, segmental and focal dystonias. At clinical inspection dystonic gait is bizarre, irregular, with abnormal posture of the foot in dystonic gait typically resulting in inversion, plantar flexion, and tonic extension of the big toe (Thomann and Dul, 1996). Complex forms of walking, such as walking backwards and sprinting, are paradoxically less affected than walking forward and may appear fully unaffected in many people. Sensory tricks, for example resting one's hand on one's neck, may alleviate or even normalize dystonic gait in certain individuals, raising the possibility of confusion with a functional gait condition. Leg adduction during gait has been described in patients with athetoid cerebral palsy, resulting in dystonic “scissoring”, however it can be difficult to distinguish from spasticity. Dystonia as part of levodopa-induced dyskinesia may be related with Parkinson's disease.

Unfortunately, the description of the dystonic pattern during gait is still based on video review (Aravamuthan et al., 2021) and only few and inconsistent 3-D gait analysis studies have been performed on dystonic gait so far, these including foot dystonia, cervical dystonia, and L-DOPA responsive dystonia (Crisafulli et al., 2021, Rebour et al., 2015). Walking speed was drastically reduced in L-DOPA responsive dystonia, whereas gait cadence and step length were lowered, and stride duration was enhanced, the kinematic of the lower limb and pelvis were abnormal, and the trunk and Center of Mass were displaced backward (Rebour et al., 2015). Patients with cervical dystonia walk with a reduced gait speed and step length, as well as increased stance time and gait variability (Crisafulli et al., 2021). Patients with foot dystonia have significantly impaired walk because the dystonic foot does not fully contact the ground and disturbs balance throughout the stance phase of gait [both the single and double support phases]. This determines a shorter stride and step length in both affected and unaffected leg which can improve after botulinum toxin injection (Datta Gupta et al., 2019). It should be noted, however, that, as with task-specific focal dystonia like runner's dystonia, the clinical presentation of foot dystonia can vary greatly between patients in terms of muscle involvement and kinematic behavior (Ahmad et al., 2018).

Huntington’s disease [HD] is clinically characterized by involuntary movements such as chorea, psychiatric signs, and progressive dementia. With the involuntary movements intruding, the gait has been called Dancing Gait. Gait impairment in patients with HD plays an important role upon motor functioning as it affects the quality of life, limits the independence of patients with HD, and reduces activities of daily living (Kirkwood et al., 2001).

Despite some discordant results, quantitative analysis studies have revealed that the gait of people with HD is characterized by a reduction in cadence, walking speed, stride length, increased stride-to-stride variability, and excessive trunk movements (Churchyard et al., 2001, Collett et al., 2014, Delval and Krystkowiak, 2010, Gaßner et al., 2020, Hausdorff et al., 1998, Koller and Trimble, 1985, Rao et al., 2008, Reynolds et al., 1999) as well as poor dynamic balance control, as indicated by increased step width, double-support and stance time (Rao et al., 2008). Some of these abnormal gait parameters correlate with disease severity outcomes (Mirek et al., 2017) and risk of falling (Grimbergen et al., 2008).

Rao et al. (Rao et al., 2011) acknowledged that gait speed, symmetry, and variability change from the pre-symptomatic stage to the five-year follow-up. In particular, swing time variability increased in one year from baseline and correlated with the estimated time to diagnosis. Worsening of gait and balance impairments over the course of the disease eventually contribute to falls and to the need for institutional care (Grimbergen et al., 2008).

7.6. Cautious gait

Fear of falling is a major element in cautious gait and is impacted by physical, psychological, social, and functional aspects (Vellas et al., 1997). A typical example of cautious gait in every daily clinical practice is the “post-fall syndrome” (Vellas et al., 1997). Furthermore, phobic gait disorder is the most severe form of cautious gait: these patients have an overwhelming fear of falling, which can result in a full incapacity to walk (Dieterich et al., 2001).

Cautious gait may arise with an excessive degree of age-related changes (Nutt et al., 1993). Nutt et al. proposed the term cautious gait to describe the gait of patients assessed in a geriatric inpatient unit. This description corresponds to the classical clinical term “senile gait” (Koller et al., 1983).

Reduced gait speed, a normal or mildly wide base with a shortened stride, turning “en bloc,” less high foot lift during the swing phase, a slightly lowered center of mass, and a stooped posture are the most noticeable abnormalities of cautious gait (Nutt et al., 1993, Pirker and Katzenschlager, 2017). There is a general agreement that the cautious gait reflect a compensatory mechanism, an adaptation to perceived postural threat. In terms of gait slowness, which is a key feature of cautious gait and is common to almost all gait disorders, it should be noted that the preferred walking speed in apparently healthy elderly subjects declines by 1% per year, from a mean of 1.3 m/s in the seventh decade to a mean of 0.95 m/s in those over 80 years old (Lim et al., 2007). Although part of these gait changes is due to normal aging, individual walking speed in senior persons is a potent predictor of overall health and survival (Studenski et al., 2011).

7.7. Frontal gait disorders

The term “higher level gait disorders” (HLGD) has been proposed to refer to a broad range of gait disorders associated with increasing white matter changes in the brain, including the brainstem, periventricular and frontal regions, basal ganglia, and cerebellar locomotor regions (Blahak et al., 2009; Danoudis et al., 2016; de Laat et al., 2010), that encompass all clinical gait and balance patterns that cannot be attributed to the classic motor or sensory deficits that cause gait and balance disorders (Nutt, 2013). HLGD have been classified into frontal (FGD) and parieto – temporal – occipital gait disorders, with FGD being the most common subtype (Nutt, 2013; Verghese et al., 2006). In subjects with FGD, the low or middle-level neurologic dysfunction is insufficient to explain the gait disorder, which is also poorly responsive to dopaminergic medications (Baezner et al., 2001). Individual patterns have been described as subcortical disequilibrium, frontal disequilibrium, isolated gait ignition failure. However, these patterns frequently overlap (Rubino, 2002). FGD includes gait disorders associated with a broad spectrum of diseases, such as parkinsonian syndromes, subcortical small vessel diseases, normal pressure hydrocephalus (Fling et al., 2016; Kuba et al., 2002; O’Keeffe et al., 1996; Sharma et al., 2023).

FGD may express both balance and locomotor impairment (Baezner and Hennerici, 2005; Liston et al., 2003; Nutt, 2013) and has been described as a gait disturbance mimicking the motor disorders of subjects with idiopathic PD. Although a few studies investigated FGD by instrumented gait analysis, it has been described as a gait pattern with short stride length, shuffling gait, postural instability, and difficulty in gait initiation and freezing of gait (Giladi et al., 2007). Differences between subjects with FGD and subjects with idiopathic PD have been reported, with the former showing wider step width (Fling et al., 2016) and arm swing preservation (Kuba et al., 2002).

7.8. Functional gait

Functional gait disorder is a frequent and disabling disorder with no obvious anatomical lesions (Baik and Lang, 2007, Baizabal-Carvallo et al., 2020, Hallett, 2016, Nonnekes et al., 2020). Often, particularly in the past, the word “psychogenic” was in use, as were other terminologies such as depressed gait, phobic gait, hysterical gait, or astasia-abasia (Alexander, 1996, Keane, 1989, Rubino, 2002, Sinel and Eisenberg, 1990). The term astasia-abasia refers to people who are unable to stand (astasia) or walk (abasia) while having adequate leg function while supine (Sinel and Eisenberg, 1990). This condition has also been documented in frontal lobe injuries. The term functional gait was proposed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V [DSM-V], which now refers to Functional Neurological Symptom Disorders instead of Psychogenic Neurological Disorders. Functional gait disorders, either isolated or occurring as part of more complex generalized functional syndromes, are not uncommon, accounting for 1.5–26% of patients admitted to a neurology unit (Bhatia, 2001, Lempert et al., 1991). These disorders are more common in younger adults than in elderly patients, especially those older than 70 years (Lempert et al., 1991, Lempert et al., 1990).

At clinical inspection or at video analysis, several types of bizarre functional gait patterns have been described, including buckling of the knee, astasia-abasia, waddling, tightrope gait, excessive retropulsion, walking on ice and penguin gait (Hallett, 2016, Keane, 1989, Lempert et al., 1991, Nonnekes et al., 2020). However, abnormal gait patterns resembling those of neurodegenerative diseases have also been reported, including ataxic, hemiparetic, spastic, dystonic, truncal myoclonic, stiff-legged, tabetic, and camptocormic gait, with the majority of patients falling into the ataxic, hemiparetic, and spastic groups (Hayes et al., 1999, Keane, 1989). Therefore, given that approximately 12% of patients across all neurologic disease categories have a functional overlay (Stone and Edwards, 2012), sometimes it may be quite challenging to distinguish between functional and pathological gait disorders, especially when the gait issue is isolated [not associated to with other symptoms].

No consistent 3D gait analysis studies have been performed on patients with functional gait disorders so far. However, in an interesting study on using 3D gait analysis, Merello et al. (Merello et al., 2012) analyzed 16 features [spatio-temporal parameters and joint kinematics] of the gait of subjects with a functional etiology as well as healthy and neurological diseases participants. Through the use of artificial neural network, they found four gait patterns including normal, ataxic, parkinsonian and spastic-paraparetic. The main results show that, although no relevant changes were reported at clinical inspection, no patient with functional gait was able to maintain the same gait pattern at the three-month evaluation follow-up.

8. General conclusion

The techniques presented in this chapter demonstrate that translational research is changing our approach of neurophysiological investigations of cerebellar disorders and gait disorders. However, numerous open questions remain unsolved for studies of the cerebellum. For instance, we still lack neurophysiological techniques assessing the activity of individual cerebellar lobules or tools to evaluate the respective contributions of climbing fibers versus mossy fibers in motor control. Still, recent advances shed light on our appraisal of cerebellar functions. The high heterogeneity of cerebellar disorders both in terms of mechanisms, phenotypes and natural history remains a major challenge of ataxiology, hampering the discovery of robust neurophysiological tools which could be used in all cerebellar disorders in daily practice.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Work cited in the chapter on eyeblink conditioning has been partly funded by the DFG FOR MeMoSLAP / FOR 5429 (P06; project number 467143400).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ahmad O.F., Ghosh P., Stanley C., Karp B., Hallett M., Lungu C., et al. Electromyographic and joint kinematic patterns in runner's dystonia. Toxins (Basel). 2018;10:166. doi: 10.3390/toxins10040166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese A., Bhatia K., Bressman S.B., Delong M.R., Fahn S., Fung V.S.C., et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov. Disord. 2013;28:863–873. doi: 10.1002/mds.25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]