Abstract

Smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation is an important component of restenosis in response to injury after balloon angioplasty. Inhibition of proliferation in vivo can limit neointima hyperplasia in animal models of restenosis. Ribozymes against c-myb mRNA have been shown to be effective inhibitors of SMC proliferation in vitro. The effectiveness of adenovirus as a gene therapy vector in animal models of restenosis is well documented. In order to test the utility of ribozymes to inhibit SMC proliferation by a gene therapy approach, recombinant adenovirus expressing ribozymes against c-myb mRNA was generated and tested both in vitro and in vivo. This adenovirus ribozyme vector is shown to inhibit SMC proliferation in culture and neointima formation in a rat carotid artery balloon injury model of restenosis.

Vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) are an important component of normal arterial function (15). These cells reside in the media in a nonproliferative (G0) state. Arterial injury results in activation and migration of SMC from the media into the intimal layer of the arterial wall, with subsequent SMC proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition (7, 15). This SMC response to injury has been implicated in restenosis following percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and is reported to occur following 30 to 50% of all PTA procedures (7, 15). Although the rate of restenosis in stented arteries is reduced, in-stent restenosis also appears to be mediated primarily by SMC proliferation (11).

Several strategies have been used to restrict cell cycle progression of quiescent SMC upon growth factor stimulation. For example, expression of a nonphosphorylatable analog of the retinoblastoma protein arrests SMC in G0/G1 (3). Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 arrests vascular SMC in G1 (2). In addition, antisense oligonucleotides directed against either proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Cdc2, or c-myb transcripts appear to affect SMC growth in vivo (16, 20).

Recently, chemically synthesized hammerhead ribozymes targeting the mRNA of the transcription factor c-myb have been shown to be efficient inhibitors of SMC proliferation in vitro (9). Effective delivery of a synthetic ribozyme to prevent restenosis would require prolonged residence of the ribozyme in the arterial wall, since SMC proliferation continues days to weeks after PTA (3, 17). Alternatively, long-term expression of ribozymes could be achieved with a gene therapy approach. Ribozymes have been developed for ex vivo gene therapy (4, 5) but would require in vivo application to prevent restenosis following PTA. To test the feasibility of a gene therapy approach with ribozymes in an in vivo model of human disease, we have generated a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing a ribozyme directed against c-myb mRNA and demonstrate its efficacy both in vitro and in a rat carotid artery balloon injury model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and adenovirus generation.

The mouse U6 gene (obtained from J. Dahlberg, University of Wisconsin, Madison) was amplified via PCR with oligonucleotides (AAGTCGACCGACGCCGCCATCTCTA and AACCATGGAAAAAGCTTGAATTCTAGTATATGTGCTGC) and cloned into pGEM5Z (Promega) to create EcoRI and HindIII sites between nucleotide 27 of U6 RNA and an RNA polymerase III termination signal. Oligonucleotides (AATTCATTGTTTTCCCTGATGAGGCCGAAAGGCCGAAATTCTCCC CTA and AGCTTAGGGGAGAATTTCGGCCTTTCGGCCTCATCAGGGAAAACAATG) encoding the ribozyme were designed to generate EcoRI/HindIII ends upon annealing and were inserted into the pGEMU6 plasmid. The U6+27Rz transcription unit was then reamplified with oligonucleotides (AAAGAAGATCTCCGACGCCGCCATCTCTA and GGGATCCGGCGAATTGGGCCCGAC) to create BglII/BamHI ends, which were used for insertion into the BamHI site of an E1-deleted adenovirus transfer plasmid. All plasmid inserts were verified by sequencing. Replication-defective adenovirus vectors were generated by homologous recombination between plasmid DNA and E1-deleted adenovirus DNA in 293 cells as described previously (18). Recombinant virus was plaque purified three to five times, and high-titer virus stocks were prepared by infecting 293 cells. Adenovirus was purified from 293 cell lysates by a two-step CsCl gradient centrifugation procedure. Viral titers were determined by plaquing on 293-G cells. Viral stocks contained <1 replication-competent virus in 108 PFU as determined by an A547 cell assay.

In vitro cleavage assay.

For in vitro cleavage analysis, the ribozyme was amplified with oligonucleotides to generate a T7 RNA polymerase promoter template. RNA was then transcribed in vitro (Ambion Megashortscript) and gel purified. Ribozyme RNA was renatured in cleavage buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7]) for 5 min at 65°C, followed by 10 min at 37°C, prior to incubation with a 32P-labeled RNA substrate containing the cleavage site. The cleavage reaction was performed under single-turnover conditions in ribozyme excess and analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Activity of chemically synthesized ribozyme to site 575 was described previously (1). For cleavage analysis of 293 cell lysates (21), total cellular RNA was isolated from cells 48 h after mock or virus infection. Total RNA (5 μg) was incubated with 32P-labeled RNA substrate in cleavage buffer for 24 h and analyzed by denaturing PAGE.

RNA analysis.

For ribozyme RNA analysis, cells were mock or virus infected for 1 h. Total RNA was isolated 48 h later and analyzed by Northern blot analysis of RNA separated on a 6% polyacrylamide denaturing gel as described previously (21). The blot was probed with an antisense riboprobe specific for the U6+27Rz transcript generated from the pGemU6+27Rz plasmid. For c-myb and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA analysis, RNA was isolated 12 h after serum stimulation and quantified by quantitative competitive (QC)-PCR as described previously (9). The competitor RNA for c-myb was derived from a fragment of rat cDNA containing a deletion of 50 bases. The GAPDH competitor was derived from plasmid pTRI-GAPDH (Ambion) and also contained a 50-base deletion. Primer annealing was performed at 50°C. The concentration of c-myb and GAPDH RNAs in each sample was determined from a nonlinear, least-squares fit of the percent competitor in the PCR products versus the amount of input competitor RNA over the entire series of competitor dilutions made against a given target sample. Error bars indicate range of duplicate samples. The Student t test was used to calculate P values.

Proliferation assay.

Rat SMC were isolated from aortic tissue explants from female rats and grown in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium as described previously (9). Human SMC were obtained from Clonetics and grown as recommended. The bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay was performed as described previously (9). Briefly, 5 × 103 rat SMC or 1 × 104 human SMC were plated per well of a 24-well plate in growth medium. After 24 h, growth medium was replaced with starvation medium containing 0.5% serum. Forty-eight hours later, cells were infected with virus diluted in starvation medium for 1 h in a total volume of 100 μl per well. Starvation conditions proceeded for an additional 24 h. Cells were then stimulated with the addition of 10% serum, and BrdU was added at a final concentration of 10 μM. Cells were incubated for 20 to 24 h, fixed with 10% methanol, and stained for BrdU. A minimum of 400 cells per well were scored microscopically, and the percent of proliferating cells was determined. Error bars represent the range of duplicate wells. For Syto 13 staining, SMC were treated as described above, except that BrdU was not added and cells were grown for 3 days after 10% serum stimulation. Medium was then removed, and a 1:2,000 dilution of Syto 13 (Molecular Probes) was added for 20 min at 37°C. Stained cells were quantified on a fluorimeter (Labsystems Fluoroskan Ascent). The Student t test was used to calculate P values.

Cell cycle analysis.

SMC were treated as described above for proliferation assays but were treated with propidium iodide 24 h after infection by using a PI-STAIN kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained cell preparations were scanned on a Becton Dickinson FACScan instrument and analyzed for cell cycle by ModFitLT.

Rat carotid balloon injury model.

The rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty followed by recombinant virus administration was performed as described previously (2, 3). Briefly, Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to balloon angioplasty of the left common carotid artery by dilatation with a Fogarty catheter. Immediately following injury, 2 × 109 PFU of Ad/U6+27Rz, Ad/U6+27RzM, or Ad/U1 control virus in a volume of 50 to 100 μl was instilled into a 1-cm segment of the distal common carotid artery for 5 min by using a 24-gauge intravenous catheter. Rat carotid arteries were harvested 20 days after balloon injury and adenovirus infection. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Intimal and medial boundaries were determined by digital planimetry of tissue sections. Areas and ratios were determined from four to six stained sections of each artery spanning the 1-cm site of balloon injury. The Student t test was used to calculate P values. All animal experimentation was performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines at the University of Chicago or at Coromed Inc., Troy, N.Y.

RESULTS

Expression of a ribozyme in an adenovirus vector.

To test the ability of an adenovirus vector expressing a ribozyme targeting c-myb mRNA to inhibit SMC proliferation, we first cloned a ribozyme directed to cleave c-myb mRNA at nucleotide 575 (based on the human c-myb sequence) into an expression vector. Because RNAs contain extensive secondary structure and are bound intracellularly by proteins, accessible sites for ribozyme cleavage may be limiting in target RNA molecules. The 575 site is conserved in both rat and human c-myb mRNA and has been shown to be accessible to ribozyme targeting in rat and human SMC (9).

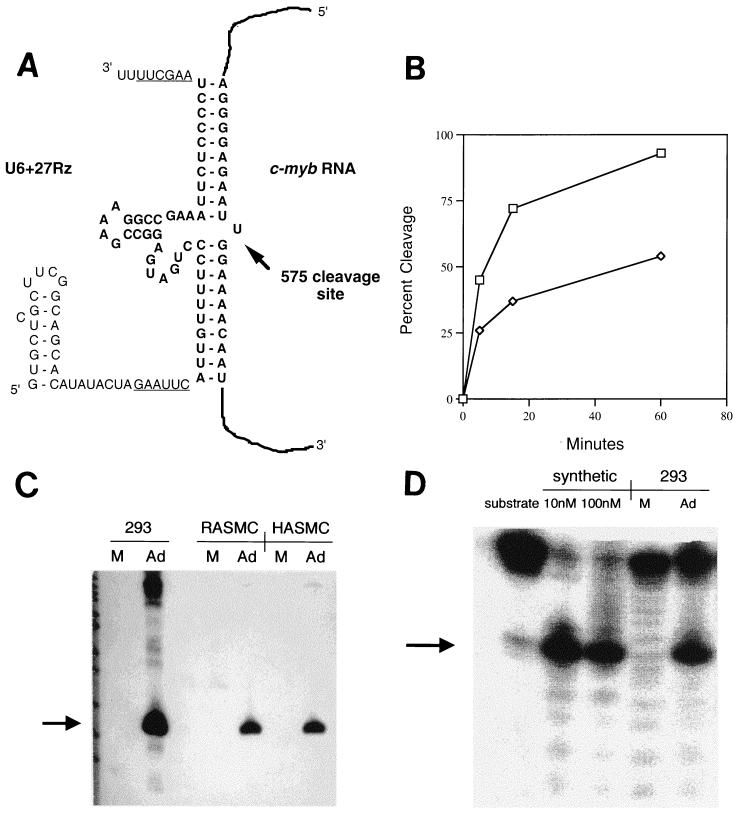

Expression of RNA from eukaryotic promoters often results in the addition of flanking sequences (e.g., the polyadenylation site and polyadenylate end of RNA polymerase II mRNAs). However, extraneous nucleotide sequence flanking a ribozyme can have a profound effect on in vitro cleavage activity (21). We have analyzed ribozyme expression and efficacy in a variety of contexts and transcription units. To express ribozymes with minimal flanking sequence, we utilized the U6 RNA promoter that is extragenic except for the first G and requires only a stretch of four U residues for termination (12). The U6 RNA ribozyme expression vector described in these studies, U6+27Rz, includes the first 27 nucleotides from the 5′ end of U6 RNA. This sequence provides 5′-end stability by signaling methylation of the first ribose (19). To check that ribozyme cleavage activity was not compromised by flanking sequences in the U6+27 transcription unit, RNA containing the first 27 nucleotides of U6 RNA, nucleotides derived from an EcoRI cloning site, the c-myb site 575 ribozyme, nucleotides derived from a HindIII site, and a UUUU termination (Fig. 1A) was synthesized by T7 polymerase in vitro. The in vitro cleavage activity (Fig. 1B) of the U6+27Rz RNA was comparable to a chemically synthesized anti-c-myb site 575 ribozyme with no flanking sequences. The cleavage activity of the U6+27Rz transcript is greater than that of the synthetic ribozyme because the synthetic ribozyme contains modifications which significantly increase nuclease stability but have a slight inhibitory effect on cleavage activity (1). Thus, the catalytic activity of the anti-c-myb site 575 ribozyme was not severely compromised by flanking sequences in the transcript. We have found that this U6+27Rz transcription unit has minimal impact on cleavage activity for several different hammerhead ribozymes (10).

FIG. 1.

U6+27 ribozyme. (A) Sequence of U6+27Rz RNA transcript (left sequence) hybridized to c-myb mRNA (right sequence) at site 575. The ribozyme (in bold) is flanked by sequence derived from EcoRI and HindIII sites (underlined) and preceded by 27 nucleotides derived from endogenous U6 RNA. (B) Catalytic activity of the c-myb site 575 ribozyme in the context of U6+27 (open squares) measured in vitro compared to a chemically synthesized 7/7 nucleotide arm ribozyme (open diamonds) to the same site. (C) Intracellular expression of ribozyme transcript. The arrow denotes the ribozyme RNA expressed in cells 48 h after mock infection (M) or infection with Ad/U6+27Rz (Ad). RASMC and HASMC denote RNA extracts of rat and human aortic SMC, respectively. (D) In vitro cleavage activity from 293 cell RNA. Substrate was incubated with synthetic ribozyme (10 or 100 nM) or RNA from 293 cells mock infected (M) or infected with Ad/U6+27Rz (Ad). The arrow denotes 5′-end-labeled cleavage product. The 3′ cleavage product does not contain label.

The U6+27Rz transcription unit was inserted into an adenovirus packaging plasmid and E1-deleted, replication-defective recombinant adenovirus, Ad/U6+27Rz, encoding the ribozyme, was generated (18). We then tested for expression of the ribozyme in Ad/U6+27Rz-infected SMC (Fig. 1C). A transcript of the expected size (80 nucleotides) was detected in both rat and human aortic SMC 48 h after infection with 100 PFU of Ad/U6+27Rz/cell. Greater than 80% of rat SMC were X-Gal positive upon infection with AdlacZ, a recombinant adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase, under the same conditions (data not shown). Based on the intensity of the hybridization signal compared to a standard curve of T7 transcribed RNA, we estimate approximately 5,000 copies of ribozyme RNA per rat aortic SMC at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. No toxicity was observed in cell culture by infection with adenovirus at this MOI. In addition, ribozyme RNA of the same size can be detected in 293 cells in which the E1-deleted virus is able to replicate (Fig. 1C). Total RNA isolated from 293 cells infected with this virus was observed to contain cleavage activity in vitro not detected in mock-infected cells (Fig. 1D), confirming that the U6+27Rz RNA transcribed in eukaryotic cells maintains ribozyme cleavage activity.

A recombinant adenovirus encoding a U1 RNA ribozyme transcription unit was also constructed. Although expression of the U1 RNA ribozyme transcript was detected in infected 293 cells, we could not detect expression in SMC infected with the recombinant virus (data not shown). A U1 RNA recombinant adenovirus encoding a catalytically attenuated ribozyme against c-myb mRNA (Ad/U1) was used in some experiments to control for effects due to recombinant adenovirus infection alone.

Inhibition of SMC proliferation in cell culture.

Since the recombinant adenovirus Ad/U6+27Rz encodes a transcript with ribozyme activity and expression of the RNA can be detected following infection of SMC in vitro, we next determined whether Ad/U6+27Rz had the ability to inhibit SMC proliferation. Serum-starved SMC (0.5% serum was required to maintain viability) were infected with either Ad/U6+27Rz or an adenovirus vector control (Ad/U1) and then induced to proliferate by the addition of 10% serum. Ribozyme expression was not inhibited by serum starvation conditions (data not shown). Rat aortic SMC infected (MOI = 100) with Ad/U6+27Rz were inhibited in their ability to proliferate over a 3-day period as measured by Syto 13 staining to quantify cell number (Table 1). The degree of inhibition by Ad/U6+27Rz infection was about twofold greater than the inhibition from control adenovirus infection (P < 0.035).

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of rat SMC proliferationa

| Study no. | Growthb | % Inhibition of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad/U6+27Rz | Virus control | ||

| 1 | 8.8 | 50 | 21 |

| 2 | 6 | 50 | 0 |

| 3 | 6 | 39 | 20 |

| 4 | 2.9 | 73 | 39 |

| 5 | 5.4 | 65 | 20 |

Inhibition was determined by difference in fluorescence between sample and 10% serum control after subtraction of background levels. Results are expressed as the means of triplicate wells.

Growth is expressed as fold increase in cell number of 10% control samples.

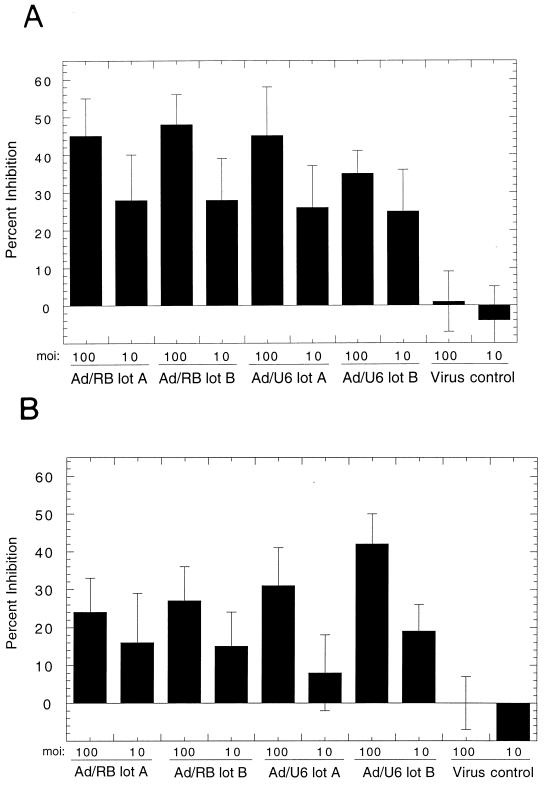

To confirm that Ad/U6+27Rz infection of SMC resulted in an increased level of inhibition of proliferation over that of viral infection alone, we analyzed SMC proliferation by BrdU incorporation. Both rat and human aortic SMC were inhibited in their ability to proliferate when infected with Ad/U6+27Rz (P < 0.05) but not when infected with the control virus (Fig. 2). The inhibition of proliferation, observed with two independent preparations of Ad/U6+27Rz, was similar to that observed following infection of these cells with AdΔRb, a recombinant adenovirus that expresses a nonphosphorylatable analogue of the retinoblastoma gene product (Rb) shown previously to inhibit growth factor-induced SMC proliferation in culture (3). Thus, it appears that Ad/U6+27Rz infection of SMC causes a specific inhibition of proliferation over that of viral infection alone. Further, since c-myb is thought to be important for cell cycle progression, we analyzed the DNA content of infected cells. Serum-stimulated SMC infected with Ad/U6+27Rz (MOI = 100) were prevented from entering S phase by 50% as shown by fluorescence-activated cell sorter-based cell cycle analysis (Table 2), consistent with the BrdU assay results.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of SMC proliferation. (A) Rat aortic SMC. (B) Human aortic SMC. SMC were serum starved for 72 h and infected with Ad/U6+27Rz at an MOI of 100 or 10, as denoted, 24 h prior to stimulation in 10% serum. Two independent preparations of AdΔRb (Ad/RB lot A and Ad/RB lot B), two preparations of Ad/U6+27Rz (Ad/U6 lot A and Ad/U6 lot B), or one preparation of an Ad/U1 control virus (Virus control) were tested. Percent inhibition is relative to the degree of proliferation of uninfected cells stimulated with 10% serum.

TABLE 2.

Cell cycle analysis of rat SMCa

| Sample | % Cells at indicated stage

|

Coefficient of variation (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0–G1 | G2–M | S | ||

| 0% | 70 | 20 | 10 | 8.6 |

| 10% | 35 | 24 | 41 | 12.4 |

| U6+27Rz | 48 | 28 | 24 | 11.6 |

Populations were assigned by using a ModFitLT program to assess DNA content of live cells scanned after propidium iodide staining.

Inhibition of SMC proliferation in cell culture is ribozyme mediated.

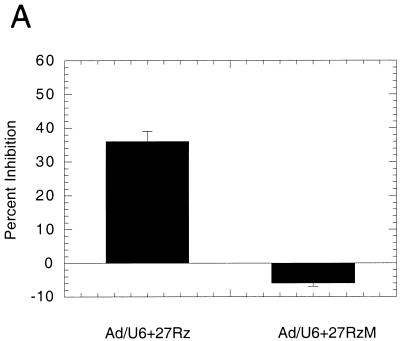

In order to determine whether ribozyme cleavage activity was responsible for the inhibition of proliferation observed, we generated a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus encoding an anti-c-myb ribozyme with two nucleotide substitutions in the catalytic core (Ad/U6+27RzM) that are known to retain cleavage activity but at a much diminished level (1). Infection of serum-starved SMC with this virus (MOI = 100) had virtually no effect on proliferation (Fig. 3A). Thus, the specific inhibition of SMC proliferation by infection with Ad/U6+27Rz required a fully active ribozyme and was not due to base pairing alone or to a U6+27 RNA motif effect.

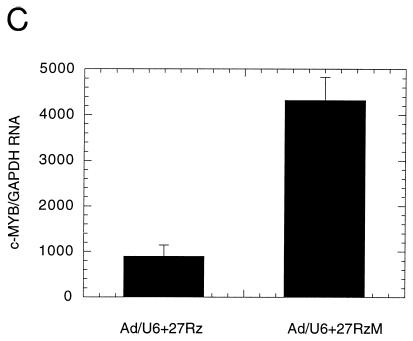

FIG. 3.

(A) Inhibition of rat aortic SMC proliferation in the presence of recombinant adenovirus encoding active ribozyme (Ad/U6+27Rz) or catalytically diminished ribozyme RNAs (Ad/U6+27RzM). (B) Relative levels of c-myb mRNA assayed by QC-PCR from rat aortic SMC serum starved (0.5%), starved and stimulated (10%), or starved, virus infected, and stimulated (Ad/U6+27Rz) are shown normalized to GAPDH mRNA. (C) Relative levels of c-myb mRNA assayed by QC-PCR from rat aortic SMC infected with Ad/U6+27Rz or Ad/U6+27RzM as noted.

Ribozyme-mediated inhibition of SMC proliferation should result in a reduction in c-myb mRNA levels relative to those seen in uninfected or control virus-infected SMC. To further confirm that the inhibition of SMC proliferation by infection with Ad/U6+27Rz was due to a ribozyme effect, we analyzed the level of c-myb mRNA in uninfected and Ad/U6+27Rz-infected (MOI = 100) rat aortic SMC, using QC-PCR (Fig. 3B). As reported previously, serum-starved SMC had very low levels of c-myb mRNA that were induced about 50-fold 12 h after the addition of 10% serum (9). In contrast, infection of SMC with Ad/U6+27Rz reduced the level of c-myb mRNA in response to serum by >90% (P < 0.001), consistent with a ribozyme-mediated effect. In addition, c-myb mRNA levels were reduced in SMC infected with Ad/U6+27Rz compared to SMC infected with Ad/U6+27RzM (Fig. 3C, P < 0.05). Taken together, these results confirm a ribozyme mechanism in cell culture. We did note, however, that c-myb RNA levels in Ad/U6+27RzM-infected cells were slightly reduced (<50%) compared to those in uninfected cells (data not shown), consistent with a diminished catalytic activity. This partial reduction in c-myb mRNA was not sufficient to inhibit SMC proliferation in vitro (Fig. 3A).

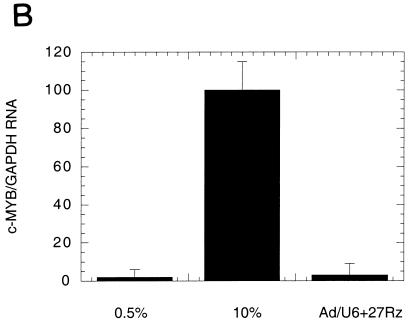

Inhibition of SMC proliferation in a rat model of balloon injury.

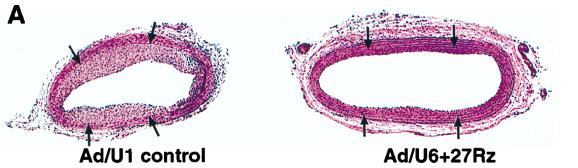

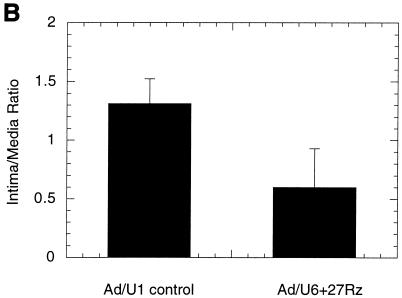

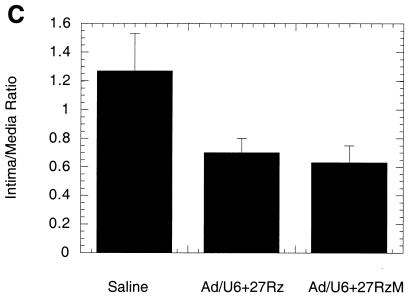

SMC proliferation is an important component of restenosis in response to injury after balloon angioplasty. The rat carotid artery balloon injury model is a well-characterized and highly reproducible vascular proliferative disorder that is dependent on SMC migration and proliferation (2, 3, 8, 16, 20). Replication-defective adenovirus vectors have been shown to efficiently infect medial SMC and to program the expression of inhibitors of SMC proliferation in vivo following balloon injury in rat carotid arteries (2, 3, 8). Accordingly, we tested whether the inhibition of SMC proliferation by Ad/U6+27Rz observed in culture was sufficient to impact neointima formation in a rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty. Rat carotid arteries were subjected to balloon angioplasty and immediately exposed to 2 × 109 PFU of either Ad/U6+27Rz or a virus control (Ad/U1). SMC proliferation, as determined by the neointima-to-media (I/M) area ratio, was measured 20 days after balloon injury. An example of an arterial section from ribozyme-treated and control-treated animals is shown in Fig. 4A. Overall, vessels of animals treated with ribozyme showed a 53% reduction (P < 0.001) in the I/M area ratio compared to vessels from animals treated with a virus control (Fig. 4B). In a similar experiment in which arteries were analyzed 14 days after injury and viral infection, the I/M ratio from Ad/U6+27Rz-treated arteries was observed to be 44% lower than the I/M ratio from saline-treated arteries (Fig. 4C; P < 0.001). However, arteries treated with Ad/U6+27RzM, the virus encoding ribozyme with diminished cleavage activity, also displayed a reduced I/M ratio (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty. (A) Photomicrographs of representative sections from vessels treated with control virus (Ad/U1 control) or Ad/U6+27Rz. Arrows denote the internal elastic lamina that separates the medial and intimal layers of the arterial wall. (B) I/M ratio quantified at day 20 from sections of vessels treated with control virus (Ad/U1 control; n = 7) or Ad/U6+27Rz (n = 6). (C) I/M ratio quantified at day 14 from sections of vessels treated with Ad/U6+27Rz (n = 10), Ad/U6+27RzM (n = 10), or saline (n = 10).

DISCUSSION

In the studies described in this report, we have constructed a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus encoding a ribozyme to c-myb mRNA (Ad/U6+27Rz). The ribozyme used in this study is based on a previously described synthetic ribozyme against c-myb RNA nucleotide 575 that contained binding arms of seven nucleotides each (9). In this study, the ribozyme contained binding arms of 10 nucleotides each, was expressed from a U6 RNA promoter, and contained the first 27 nucleotides of U6 RNA. The ribozyme in the context of U6+27Rz RNA maintains in vitro cleavage activity and is expressed in SMC infected with the virus (Fig. 1). Infection of cultured SMC with Ad/U6+27Rz inhibited serum stimulated proliferation of these cells twofold over infection with control virus in a 3-day Syto 13 assay (Table 1) and by as much as 50% in a 1-day BrdU incorporation assay (Fig. 2). The degree of inhibition observed following infection with Ad/U6+27Rz was comparable to that of AdΔRb, a recombinant adenovirus that expresses a nonphosphorylatable analogue of RB which has been shown previously to inhibit SMC proliferation in vitro and in vivo (3). In addition, the inhibition due to Ad/U6+27Rz infection was similar to that reported previously with a synthetic ribozyme to the same site (9).

The inhibition of proliferation in cell culture was not observed in SMC infected with Ad/U6+27RzM, an adenovirus encoding a ribozyme with diminished cleavage activity (Fig. 3A). In addition, a >90% reduction in targeted c-myb mRNA was detected in infected SMC compared to uninfected SMC (Fig. 3B). These observations lead us to conclude that ribozyme activity is the mechanism that inhibits SMC proliferation and is a rate-limiting step in cell culture.

It is not surprising that although the specific c-myb RNA target was reduced by >90% upon treatment with Ad/U6+27Rz, SMC proliferation was inhibited by only 30 to 70% (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Proliferation is a multicomponent process, of which c-myb is one factor. Similarly, when c-myb RNA was reduced by ∼80% with a chemically synthesized anti-c-myb ribozyme, proliferation was inhibited by ∼50% (9). Moreover, overexpression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21, completely blocked RB phosphorylation and resulted in ∼60% inhibition of proliferation (2). The complete inhibition of SMC proliferation may require targeting a number of factors involved in cell cycle progression.

Because adenovirus has been shown to infect medial SMC in vivo following balloon injury of rat carotid arteries, we tested the ability of Ad/U6+27Rz to mediate inhibition of SMC proliferation in such a model. Neointima formation in a rat carotid model of balloon angioplasty was inhibited by ∼50% in arteries treated with Ad/U6+27Rz compared to arteries treated with vehicle or a control virus (Fig. 4). Although a fully active ribozyme core was needed to achieve a maximal response in cell culture, ribozyme with diminished cleavage activity also inhibited neointima formation in a rat carotid model (Fig. 4C). One explanation for the difference in vitro and in vivo may be that cleavage activity is not the rate-limiting step in vivo. It is possible that the diminished cleavage activity of Ad/U6+27RzM is sufficient to mediate inhibition in a 14-day animal model but not robust enough in a 1-day cell culture model. Although these results are still consistent with a ribozyme mechanism, generation and testing of a recombinant virus encoding a completely inactive ribozyme core and a more extensive virus dosing study would be required to fully elucidate the mechanism of action in vivo.

The degree of inhibition observed in vivo with Ad/U6+27Rz is comparable to other reported recombinant adenovirus-mediated strategies, such as expression of herpes simplex thymidine kinase in the presence of ganciclovir (8, 17), expression of a constitutively active form of the retinoblastoma gene product (3), or overexpression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (2). This study supports the use of ribozymes in gene therapy targeting vascular disease such as restenosis. However, the disease in humans appears to be much more complex than that modeled in the rat. The human restenotic lesion contains other cell types in addition to SMC and involves additional processes, such as thrombus formation, matrix deposition and vessel remodeling. Although neointimal SMC may contribute to these additional factors, and potential SMC inhibitors can be screened in the rat model, these inhibitors (such as Ad/U6+27Rz described here) require further testing before their applicability in human vascular disease can be determined.

Although there are numerous examples of vector-encoded ribozyme efficacy in cell culture and ex vivo (4, 5), there are only a few examples of therapeutic applications of ribozymes in vivo. Exogenous delivery of chemically synthesized antistromelysin ribozymes in a rabbit model of interleukin-1-induced arthritis results in reduction of stromelysin mRNA in synovial cells (6). Adenovirus-mediated gene therapy of a ribozyme results in inhibition of a reporter target (human growth hormone) in transgenic mice (14). In addition, adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of ribozymes targeting a mutated rhodopsin mRNA was shown to slow the rate of photoreceptor degeneration in a transgenic rat model (13). Although the mechanism of action in vivo is not identified, this study nonetheless demonstrates that a nonintegrating gene therapy-mediated application of a ribozyme can be efficacious against a disease process in an animal model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jim Dahlberg for providing the mouse U6 gene. We are grateful to Tom Parry for his efforts to ensure that the rat carotid model used by Coromed, Inc., was the same as the one at the University of Chicago. We also thank Pam Pavco and Nassim Usman for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beigelman L, McSwiggen J A, Draper K G, Gonzalez C, Jensen K, Karpeisky A M, Modak A S, Matulic-Adamic J, DiRenzo A B, et al. Chemical modification of hammerhead ribozymes. Catalytic activity and nuclease resistance. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25702–25708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang M W, Barr E, Lu M M, Barton K, Leiden J M. Adenovirus-mediated over-expression of the cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p21 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat carotid artery model of balloon angioplasty. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:2260–2268. doi: 10.1172/JCI118281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang M W, Barr E, Seltzer J, Jiang Y-Q, Nabel G J, Nabel E G, Parmacek M S, Leiden J M. Cytostatic gene therapy for vascular proliferative disorders with a constitutively active form of the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1995;267:518–522. doi: 10.1126/science.7824950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christoffersen R E, Marr J J. Ribozymes as human therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2023–2037. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couture L A, Stinchcomb D T. Anti-gene therapy: the use of ribozymes to inhibit gene function. Trends Genet. 1996;12:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)81398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flory C M, Pavco P A, Jarvis T C, Lesch M E, Wincott F E, Biegelman L, Hunt III S W, Schrier D J. Nuclease-resistant ribozymes decrease stromelysin mRNA levels in rabbit synovium following exogenous delivery to the knee joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:754–758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrester J S, Fishbein M, Helfant R, Fagin J. A paradigm for restenosis based on cell biology: clues for the development of new preventative therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:758–769. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzman R J, Hirschowitz E A, Brody S L, Crystal R G, Epstein S E, Finkel T. In vivo suppression of injury-induced vascular smooth muscle cell accumulation using adenovirus-mediated transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10732–10736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis T C, Alby L J, Beaudry A A, Wincott F E, Beigelman L, McSwiggen J A, Usman N, Stinchcomb D T. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by ribozymes that cleave c-myb mRNA. RNA. 1996;2:419–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen, K. L., and D. M. Macejak. Unpublished data.

- 11.Kearney M, Pieczek A, Haley L, Losordo D W, Andres V, Schainfeld R, Rosenfield K, Isner J M. Histopathology of in-stent restenosis in patients with peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 1997;95:1998–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.8.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel G R, Pederson T. Transcription of a human U6 small nuclear RNA gene in vivo withstands deletion of intragenic sequences but not of an upstream TATATA box. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:7371–7379. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.18.7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewin A S, Drenser K A, Hauswirth W W, Nishikawa S, Yasumura D, Flannery J G, LaVail M M. Ribozyme rescue of photoreceptor cells in a transgenic rat model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Med. 1998;4:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieber A, Kay M A. Adenovirus-mediated expression of ribozymes in mice. J Virol. 1996;70:3153–3158. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3153-3158.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M W, Roubin G S, King S B. Restenosis after coronary angioplasty: potential biologic determinants and role of intimal hyperplasia. Circulation. 1989;79:1374–1386. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.6.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morishita R, Gibbons G, Ellison K, Nakajima M, Zhang L, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T, Dzau V. Single intraluminal delivery of antisense cdc2 kinase and proliferating-cell nuclear antigen oligonucleotides results in chronic inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8474–8478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohno T, Gordon D, San H, Pompili V J, Imperiale M J, Nabel G J, Nabel E G. Gene therapy for vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation after arterial injury. Science. 1994;265:781–784. doi: 10.1126/science.8047883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich D P, Couture L A, Cardoza L M, Guiggio V M, Armentano D, Espino P C, Hehir K, Welsh M J, Smith A E, Gregory R J. Development and analysis of recombinant adenovirus for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:461–476. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.4-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shumyatsky G, Wright D, Reddy R. Methylphosphate cap structure increases the stability of 7SK, B2, and U6 small RNAs in Xenopus oocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4756–4761. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.20.4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simons M, Edelman E R, DeKeyser J, Langer R, Rosenberg R D. Antisense c-myb oligonucleotides inhibit intimal arterial smooth muscle cell accumulation in vivo. Nature. 1992;359:67–70. doi: 10.1038/359067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson J D, Ayers D F, Malmstrom T A, McKenzie T L, Ganousis L, Chowrira B M, Couture L, Stinchcomb D T. Improved accumulation and activity of ribozymes expressed from a tRNA-based RNA polymerase III promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2259–2268. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]