Abstract

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE)’s ε4 alle is the most important genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Cell-surface heparan sulfate (HS) is a cofactor for ApoE/LRP1 interaction and the prion-like spread of tau pathology between cells. 3-O-sulfo (3-O-S) modification of HS has been linked to AD through its interaction with tau, and enhanced levels of 3-O-sulfated HS and 3-O-sulfotransferases in the AD brain. In this study, we characterized ApoE/HS interactions in wildtype ApoE3, AD-linked ApoE4, and AD-protective ApoE2 and ApoE3-Christchurch. Glycan microarray and SPR assays revealed that all ApoE isoforms recognized 3-O-S. NMR titration localized ApoE/3-O-S binding to the vicinity of the canonical HS binding motif. In cells, the knockout of HS3ST1—a major 3-O sulfotransferase—reduced cell surface binding and uptake of ApoE. 3-O-S is thus recognized by both tau and ApoE, suggesting that the interplay between 3-O-sulfated HS, tau and ApoE isoforms may modulate AD risk.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, heparan sulfate, apolipoprotein E, 3-O-Sulfation, glycobiology

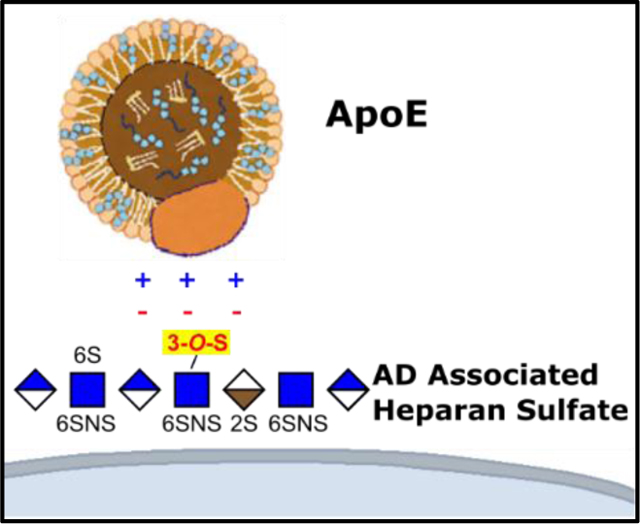

Graphical Abstract

The interaction of Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) with cell surface Heparan Sulfate (HS) is enhanced by a rare, Alzheimer’s Disease linked 3-O-Sulfo group. This binding motif is shared with tau protein, suggesting a mechanism for ApoE/tau interactions in the association of certain ApoE isoforms with AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive decline of cognitive function and the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain[1]. Epidemiological and genome wide association studies have identified polymorphism in the APOE gene as the most significant genetic determinant of Late Onset AD (LOAD) risk[2,3]. Compared to individuals homozygous for wild type APOE ε3, carriers of the ε4 allele (C112R) exhibit an increase in AD risk of 3- to 4- fold in heterozygotes and approximately 9- to 15- fold in homozygotes[4]. Carriers of the ε2 (R158C) in contrast exhibit a more than two-fold decrease in AD risk[5].

Several rare APOE isoforms are also characterized in humans. One of these, a R136S mutant termed ε3-Christchurch (ApoE3cc) recently came to light in a case study of an individual homozygous for the ApoE3cc allele in a familial AD cohort[6]. Despite extensive Aβ burden, the subject remained free of cognitive impairment into her 70s, 30 years after the typical age of onset for her cohort, suggesting ApoE3cc has neuroprotective properties similar to or exceeding ε2. There was little tau pathology in the patient’s brain, suggesting a connection between ApoE isoforms and tau in the modulation of AD risk[6].

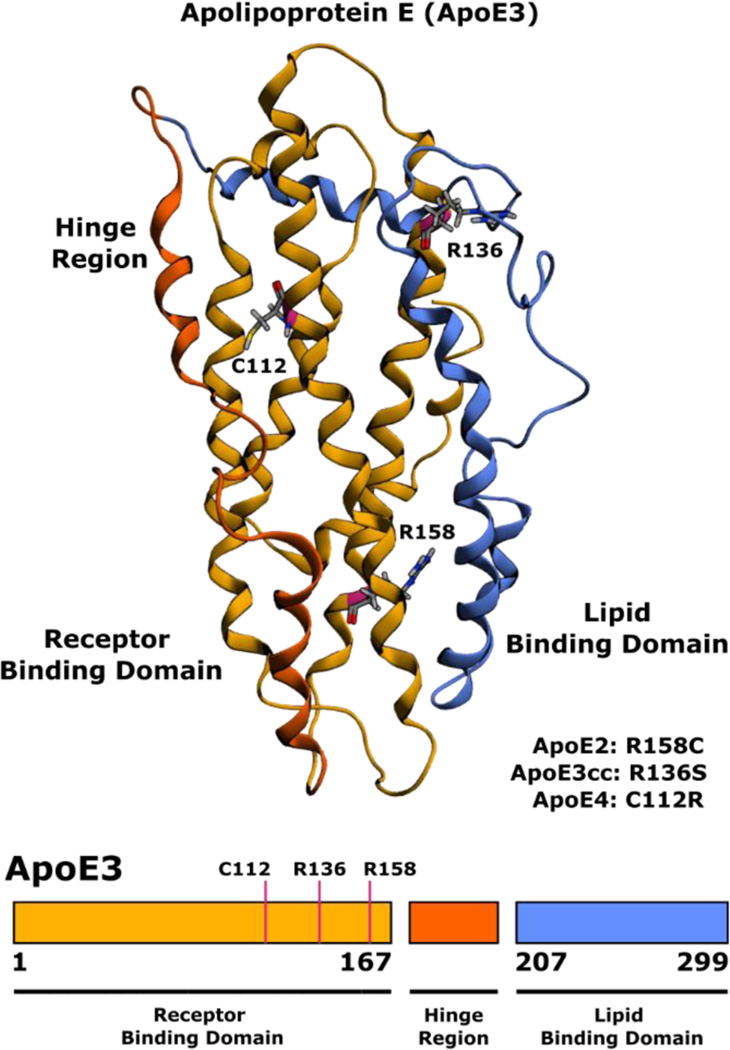

The protein product of APOE, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a ~34 kDa lipid transport protein consisting of an N-terminal receptor binding domain (NTD) organized into a four-helix bundle linked to a C-terminal lipid binding domain by a flexible hinge region (Figure 1)[7]. ApoE bound lipoproteins are secreted by astrocytes, hepatocytes and macrophages, and subsequently internalized by Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor family receptors LDLR, LRP1, VLDR, and ApoER2. ApoE plays a particularly important role in the central nervous system where it is the primary vehicle for lipid and cholesterol transport between neurons and astrocytes, with LRP1 being the major neuronal receptor for ApoE[8–10].

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional structure of lipid free human ApoE (PDB 2L7B)[30] with polymorphism sites indicated for ApoE2, ApoE3cc, and ApoE4.

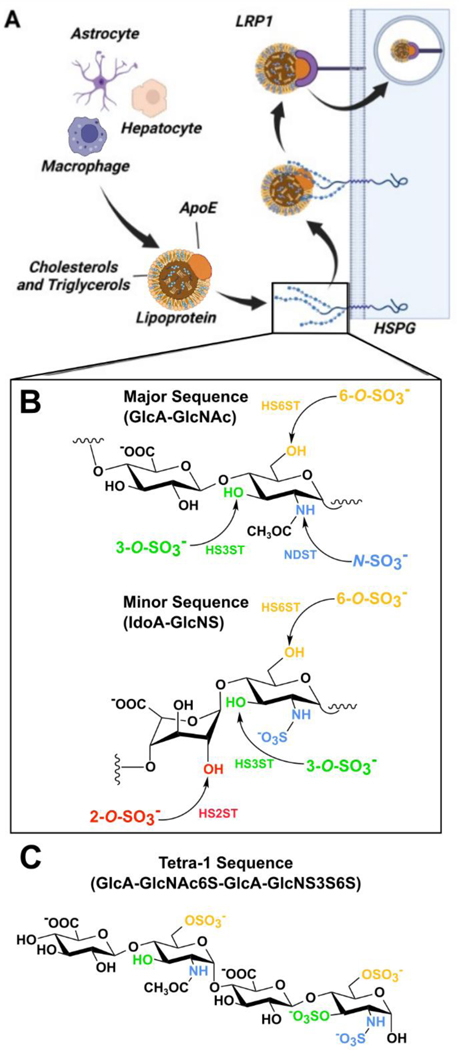

Cell surface heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (HSPGs) are important cofactors for LRP1 mediated ApoE uptake, serving as an initial site for the binding of ApoE bound lipoproteins, which can be followed by either direct HSPG mediated internalization, or transfer to LRP1 for endocytosis[9–14] (Figure 2A). Structurally, HS and heparin (a highly sulfated HS analogue) are linear polysaccharides composed of repeating disaccharide units of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and either glucuronic (GlcA) or iduronic acid (IdoA)[15,16]. The HS repeating unit has four variable sulfation sites: N-S, 2-O-S, 6-O-S, and 3-O-S, where negatively charged sulfo groups are introduced by Golgi-membrane associated sulfotransferases (Figure 2B). These sulfo groups act as key determinants of HS/heparin interactions with proteins[16–18] (Figure 2B).

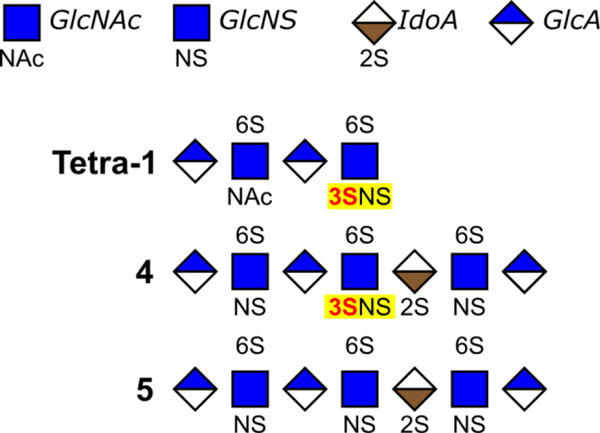

Figure 2.

Cell surface HSPGs mediate the uptake of ApoE. (A) ApoE-containing lipoproteins are taken up by LRP1 in an HSPG dependent mechanism. (B) The HS disaccharide repeats is composed of glucuronic/iduronic acid followed by N-acetylglucosamine. HS sulfotransferases act upon GlcNAc at N-acetyl, 3-O, and 6-O sites and uronic acid at the 2-O site, producing distinct patterns of sulfation. (C) Structure of AD enriched HS glycan tetra-1.

The 3-O-S moiety is the rarest HS modification site, with few known binding partners and a poorly understood biological function[19]. Emerging evidence suggests a connection between 3-O sulfation of HS and AD. Transcriptomics and proteomics data from the Human Protein Atlas indicates all but one (Hs3st6) of the of the seven 3-O-sulfotransferases found in humans are expressed within the central nervous system, with four (Hs3st1, Hs3st2, Hs3st4, and Hs3st5) being specific to the brain[20]. Two independent genome wide association studies have identified Hs3st1 as a putative AD risk factor[21,22]. Tau protein, the major component of neurofibrillary tangles, interacts with 3-O-S for cell surface binding and uptake[23]. Additional evidence shows that HS 3-O-Sulfotransferase expression is upregulated in the AD brain[24], accompanied by a nearly three-fold increase by mass percentage of a specific, 3-O-sulfo containing motif termed tetra-1 (Figure 2C)[25].

Motivated by the connections between ApoE and AD, we probed the interactions of ApoE with the various sulfation groups of HS on an isoform specific basis. Our data indicate that ApoE interacts with oligosaccharides containing the rare, AD linked 3-O-S group, facilitating ApoE cell surface binding and uptake. This interaction is conserved across the three common ApoE isoforms (ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4), as well as the rare ApoE3cc mutant.

Results and Discussion

3-O-S Enhances the Binding of HS to Multiple ApoE Isoforms in Glycan Array Analysis

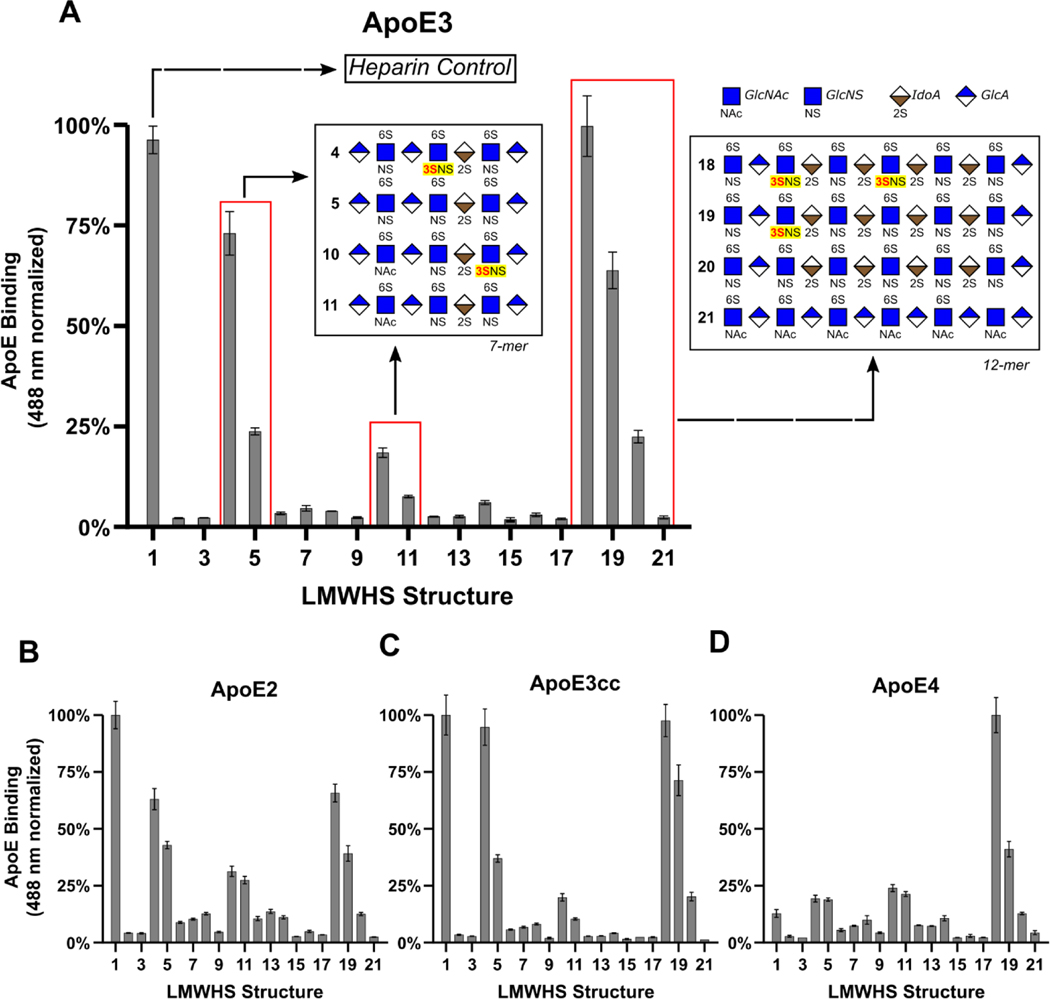

We employed a well-established[26–29] microarray consisting of 52 chemically defined HS oligosaccharides immobilized on a microarray chip (Figure S1), termed a Low Molecular Weight HS (LMWHS) array, to probe the glycan determinants of ApoE/HS interactions (Figure 3 and Figure S2). The binding of ApoE to the array—or lack thereof—was measured using ApoE labeled with Alexa-Fluor 488. ApoE3 binding produced strong signals in wells immobilized with heparin (a positive control), HS heptasaccharides (7-mers) 4, 5, 10, and 11, and dodecasaccharides (12-mers) 18, 19, and 20, indicating elevated binding. A striking trend emerges upon comparing the structures of these oligosaccharides: glycans containing 3-O-S groups bind significantly more than identical structures lacking 3-O-S groups. Among the 7-mers, the 3-O-sulfated oligos 4 and 10 respectively produced a 2-fold and 1.4-fold increase in fluorescence relative to their counterparts, oligos 5 and 11. Among the 12-mers, oligo-18, which has two 3-O-S groups, produced 50% more fluorescence than oligo-19, which possesses only one 3-O-S, and a 3.4-fold increase relative to oligo-20, which entirely lacks 3-O-S (Figure 3A). Curiously, oligo-22, which lacks 3-O sulfation, also exhibited strong binding to ApoE (Figure S2). A subsequent SPR competition assay carried out using a 3-O sulfated version of oligo-22 revealed an enhanced ability to compete for ApoE/heparin binding compared to the original glycan, consistent with the impact of 3-O-S on the other LMWHS compounds (Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Glycan microarray reveals the 3-O-S binding preference of ApoE. (A) The normalized fluorescence intensity of the ApoE3 microarray results for wells 1–22 represented as a bar graph reveal a clear binding preference for 3-O-sulfated 7-mers and 12-mers. The structures of the glycans present in wells 4, 5, 10, 11, 18, 19, and 20 are represented in glycan notation. Results of the glycan microarrays for (B) ApoE2, (C) ApoE3cc, and (D) ApoE4. A complete list of all HS oligosaccharides used in the array, and the full results of the array can be found in Figures S1 and S2 respectively. Error bars are ± SEM.

Due to the relevance of APOE polymorphism in human health and disease, we repeated this array using three additional isoforms: ApoE2, ApoE4, and ApoE3cc, finding the relative binding of these isoforms to 12-mers to be largely unchanged compared to ApoE3. Among the 7-mers, the binding pattern of ApoE3cc was largely the same as ApoE3 (Figure 3C). ApoE2 exhibited a noticeable reduction in its response to the 3-O-sulfated 7-mers (Figure 3B), while the binding of ApoE4 to oligos 4/10 compared to 5/11 was nearly identical (Figure 3D). These data show that 3-O-S is recognized in HS 12-mers by all ApoE isoforms under study, and in HS 7-mers except by ApoE4.

Characterization of the ApoE/heparin Interaction Supports the Correlation Between Glycan Affinity and AD Risk

ApoE binds to HS and heparin with dissociation constants on the order of 10−7 to 10−8 M[11,12], mainly mediated by a cluster of lysine and arginine residues spanning R142-R147[12]. Previous studies suggest ApoE/glycan interactions occur in two stages: a fast electrostatic interaction, followed by a slower conformational change step[11,12]. Interestingly, the affinity of ApoE isoforms for HS and heparin roughly correlates with their contribution to AD risk, with ApoE4 having the highest affinity, and ApoE3cc the lowest[6,11,31].

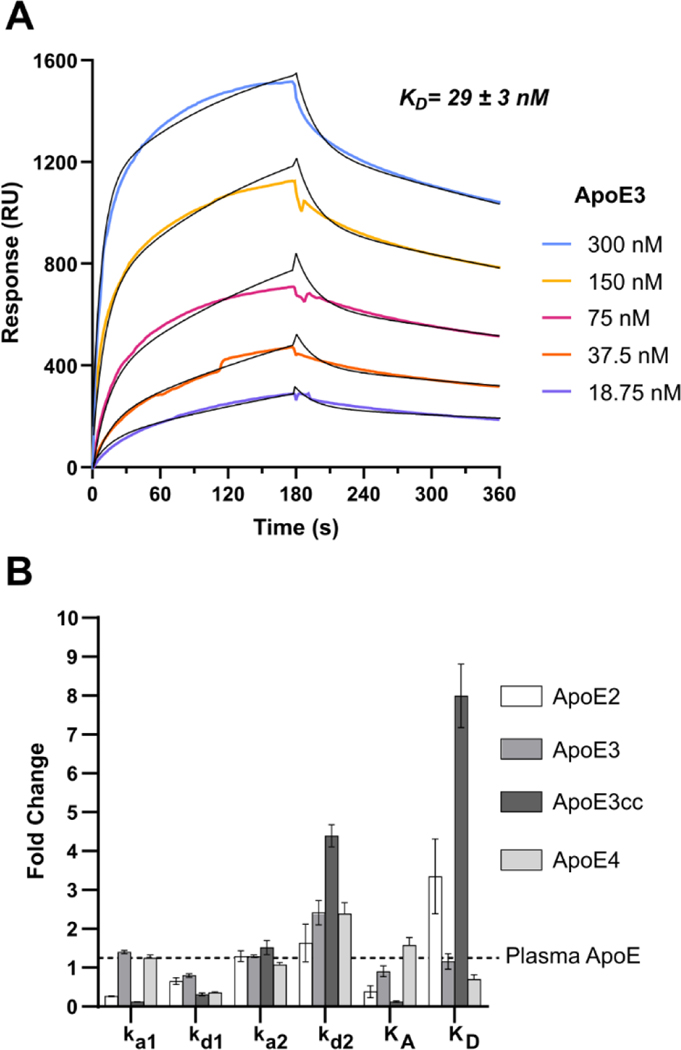

To interrogate the kinetics and thermodynamics of the ApoE/3-O-S interaction and validate the findings of the LMWHS array, we employed Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Porcine derived heparin was biotinylated and immobilized on a streptavidin sensor chip. We found the binding affinity (KD) of our ApoE constructs by fitting sets of sensograms from ApoE/heparin binding at varying concentrations, deriving a KD of 25 nM for ApoE3 (Figure 4A), 64 nM for ApoE2 (Figure S3B), and 17 nM for ApoE4 (Figure S3D), consistent in both affinity and kinetics with previous measurements of ApoE/heparin binding using SPR[11], as well a sample of human plasma derived ApoE (Figure S3A) (Table 1). ApoE3cc, which had yet to have its heparin binding kinetics quantified, bound to heparin with a KD of 200 nM, dramatically lower than wild type ApoE3, confirming earlier studies which indicated its affinity for heparin was lower than any of the common isoforms[6]. In all cases, the kinetics of the ApoE/glycan interaction fit a two-state reaction model, with a fast initial interaction followed by a slow conformational change step (Table 1). Consistent with previous data, ApoE2’s reduced affinity for heparin was largely due to a lower ka1, while ApoE4’s increased affinity resulted from a reduced kd1. Interestingly, ApoE3cc also exhibited a reduction to kd1, however this was offset by an increase to kd2 and a drastically lower ka1 (Figure 4B). The more than 10-fold reduction in the association constant of the fast reaction suggests the disruption of electrostatic interactions are responsible for ApoE3cc’s low affinity for heparin. This represents the first time the kinetics of ApoE3cc binding to heparin have been quantified, and confirms both its reduced affinity for heparin, and the retention of two state binding kinetics.

Figure 4.

Isoform Specific Kinetics of the ApoE/Heparin Interaction (A) The binding affinity of the ApoE-HS interaction was measured to be 29 nM by SPR binding kinetic assay for human ApoE3. The association and dissociation curve of different ApoE3 concentrations were fitted (black line) to a two-state reaction (conformational change) model. (B) A bar graph comparing the ApoE isoform kinetics constants relative to recombinant ApoE3. Error bars are ± SEM.

Table 1.

Kinetics and Thermodynamics of ApoE/heparin interaction from SPR

| ApoE Isoform | ka1 (105/M*s) | kd1 (10−2/s) | ka2 (10−3/s) | kd2 (10−3/s) | KA (105/M) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE3 | 2.3 ± 0.03 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 410 ± 20 | 25 ± 1.3 |

| ApoE2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 170 ± 30 | 64 ± 12 |

| ApoE3cc | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 12 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 4 | 200 ± 14 |

| ApoE4 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.01 | 580 ± 30 | 17 ± 1 |

| Plasma Derived | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 400 ± 60 | 26 ± 4 |

Competition SPR Demonstrates Site Specific Preferences for Sulfation in ApoE-Glycan Binding

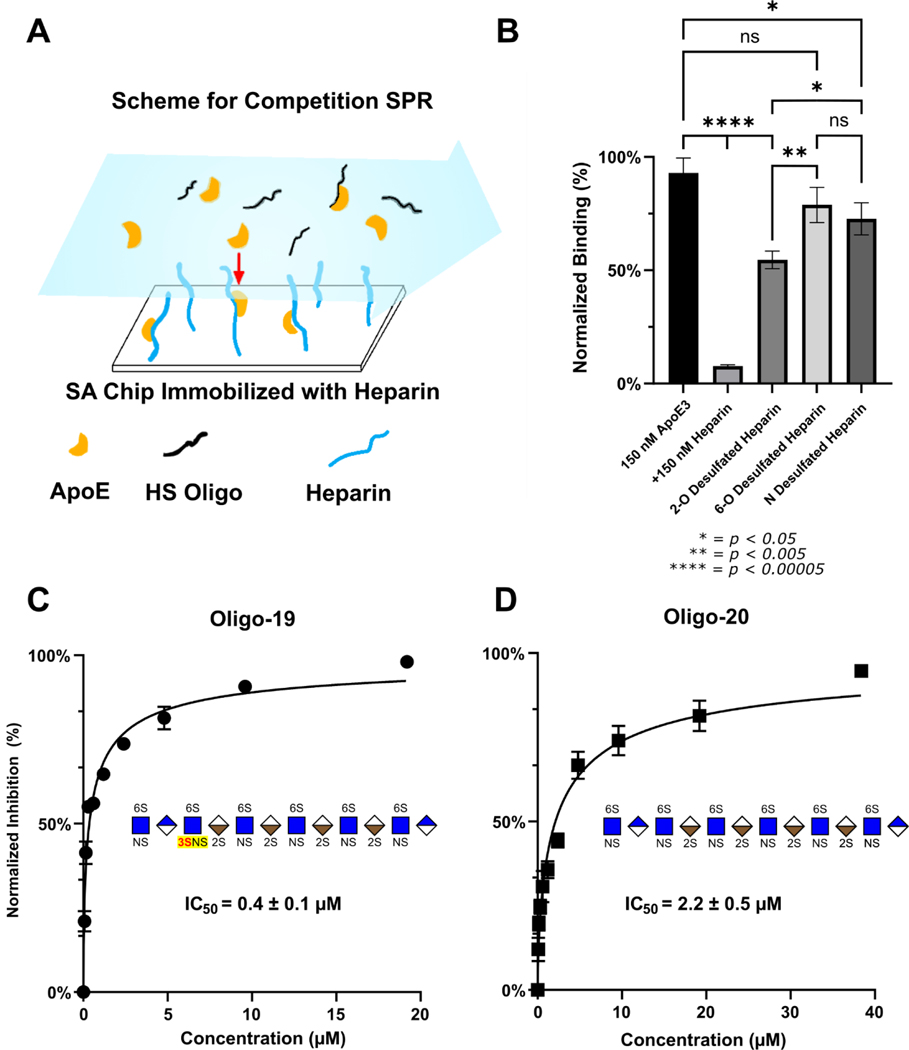

To study the impact of site-specific sulfation, we also performed solution and surface competition (competing with chip bound heparin) SPR using desulfated heparin with 6-O-S, 2-O-S or N-S groups chemically removed (Figure 5A). Recombinant ApoE3 was premixed with each polysaccharide at a defined concentration and flowed over the chip containing immobilized heparin. Increasing oligosaccharide concentration binds ApoE in solution, diminishing the interaction of ApoE with the heparin on the surface of the chip and reducing the signal from ApoE/heparin binding.

Figure 5.

Competition SPR corroborates ApoE’s recognition of 3-O-S in LMWHS Array. (A) Scheme for competition SPR. (B) SPR competition with chemically desulfated heparin. The inhibition of ApoE/Heparin interactions by chemically desulfated heparin indicates that the 6-O-S group plays a large role compared to the 2-O-S group. Whereas fully sulfated heparin almost completely abolishes ApoE3 binding to the heparin chip, 2-O-desulfated heparin retains about 60% ApoE binding, while 6-O-S desulfated heparin retains 80% binding and N-desulfated heparin retains 70%. (C) The 3-O-Sulfated Oligo-19 inhibits ApoE3-HS binding with an IC50 of 0.4 μM, compared to (D) oligo-20, which inhibits ApoE-HS binding with an IC50 of 2.2 μM. Error bars are ± SEM.

Unmodified heparin was used as a positive control, which practically abolished interaction between ApoE and the heparin on the chip (Figure 5B). In contrast, the desulfated glycans retained approximately 60% binding for 2-O-desulfated heparin, 70% for N-desulfated heparin, and 80% for 6-O-desulfated heparin (Figure 5B). This result indicates that ApoE interacts preferentially with 6-O-S and N-S over 2-O-S, which has not previously been reported in the literature.

Due to the chemistry of desulfation and rarity of 3-O-S, it is not possible to prepare completely 3-O-desulfated heparin. To corroborate the glycan array results, we carried out additional competition SPR experiments using HS oligos 19 and 20, along with oligo-22 and a 3-O-S modified version of oligo-22-3S as previously mentioned. The IC50 constants for the inhibition of the ApoE/heparin interaction by oligos 19 and 20 were measured respectively as 0.4 μM and 2.2 μM (Figure 4B-C), consistent with the stronger binding of ApoE to oligo-19 in the glycan microarray. Oligo-22 inhibited binding with an IC50 of 1.0 μM for the original compound, and 0.2 μM for the 3-O Sulfated version (Figure S3). The large decrease in the IC50 of oligo-19 and the 3-O sulfated oligo-22 variant compared to their 3-O-S lacking counterparts (oligo-20 and 22), shows that the presence of a 3-O-S group significantly enhances this inhibition.

Knockout of Hs3st1 Reduces the Cellular Binding and Uptake of Multiple ApoE Isoforms

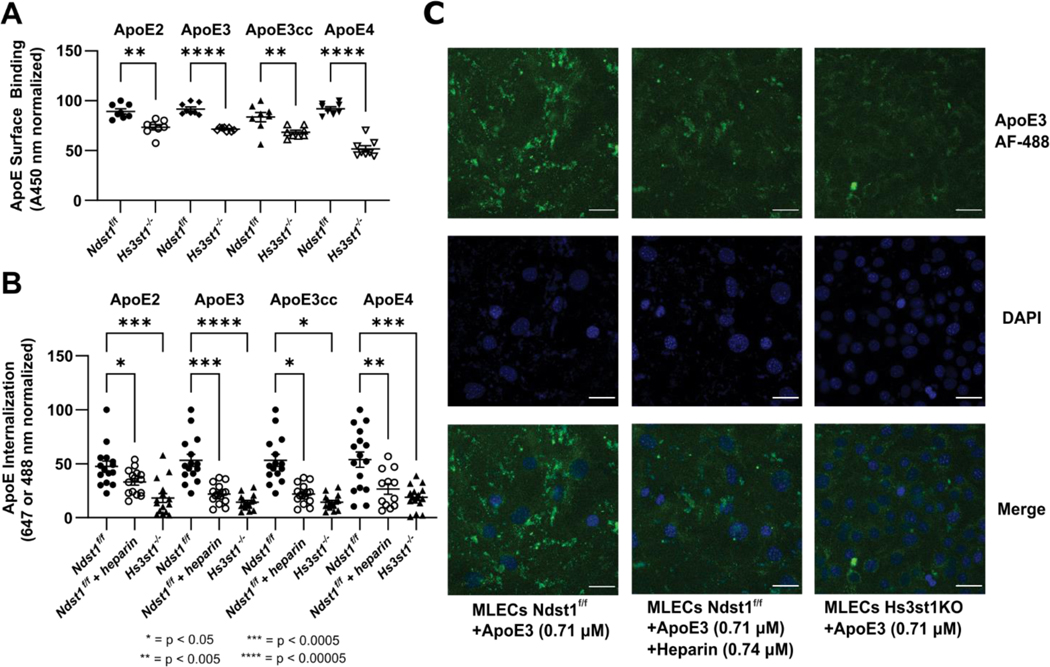

We also carried out assays to measure the binding of ApoE to the cell surface and its subsequent uptake to test the relevance of our biophysical findings in a cellular context. A pair of previously described cell lines[32] consisting of wild type (WT or Ndst1f/f) and Hs3st1 knockout (Hs3st1−/−) mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) were used in these experiments. Hs3st1−/− MLECs express lower level of 3-O-S groups, but retain normal levels of N-S, 6-O-S, and 2-O-S groups[23].

Biotinylated ApoE was incubated with cells and detected using streptavidin-horse radish peroxidase (HRP) to measure ApoE cell surface binding. Recombinant ApoE2, ApoE3, ApoE3cc, and ApoE4 all bound to the surface of the WT Ndst1f/f MLECs, while surface binding was significantly diminished in the Hs3st1−/− line. The magnitude of this inhibition ranged from 25% for ApoE2 to 50% for ApoE4 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Hs3st1 knockout inhibits the binding and uptake of ApoE in an isoform independent fashion. (A) Hs3st1−/− cells show a highly significant reduction in ApoE cell surface binding compared to wild type Ndst1f/f MLECs. Following fixation and incubation with biotinylated ApoE (1000 ng/mL, 100 μL/well) for 90 minutes at RT, cell surface bound ApoE was measured following incubation with streptavidin-HRP and color development. (B) The internalization of fluorescently labeled ApoE is significantly reduced by knockout of Hs3st1, demonstrating the role of 3-O-S in ApoE uptake. (C) Representative confocal microscopy images of ApoE internalization experiments graphed in panel B. ApoE3 is visualized via fluorescence at 488 nm, nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Scale bars are 20 μm. Error bars are ± SEM.

For uptake assays, the cells were incubated with Alexa-488 labeled ApoE (except for ApoE2, which was labeled with Alexa-647) for 4 hours and imaged via confocal microscopy to measure fluorescence from ApoE uptake. As a positive control we used WT cells treated with heparin, which has previously been shown to inhibit ApoE uptake. Compared to untreated WT cells, both heparin treated WT and Hs3st1−/− cells exhibited a significant reduction in fluorescence from internalized ApoE(Figure 6B–C). This effect was consistent across all isoforms under study, further confirming the relevance of 3-O-S groups in ApoE/HS interactions.

ApoE and Tau Compete for Cell Surface Binding

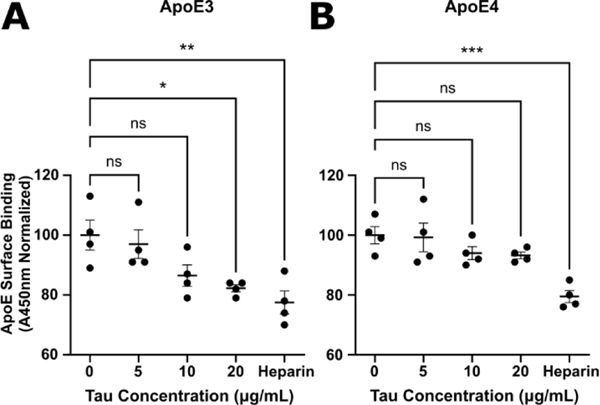

Given the similarity between the ApoE/HS binding motif identified in this paper and the Tau/HS binding motif described in our previous work[23], as well as their shared uptake via the LRP1 pathway[33], we speculated that ApoE and tau would compete with one another for HS binding.

To this end, we carried out additional cell surface binding assays with ApoE3 and ApoE4 in MLECs. Varying concentrations of tau were introduced to MLECs incubated with biotinylated ApoE3 or ApoE4 to achieve a final ApoE concentration of 1.2 μg/mL. For a positive control, we used 500 μg/mL of heparin in place of tau. After further incubation and washes, we measured the cell surface binding of ApoE via streptavidin-HRP as described in the previous section.

At high ratios of Tau to ApoE, we observed a significant decrease in the cell surface binding of ApoE3 (Figure 7A). The magnitude of this decrease (~20%) was comparable to the inhibition achieved in the heparin positive control. Conversely, the inhibition of ApoE4 cell surface binding was limited in magnitude (~5%) and not statistically significant, even at the highest Tau concentrations (Figure 7B), while heparin inhibited ApoE4 binding with a similar magnitude to ApoE3. The drastic reduction in tau’s ability to compete for cell surface binding with ApoE4 compared to ApoE3 is suggestive of tighter binding between ApoE4 and cell surface HS. This is consistent with the ApoE4’s higher heparin binding affinity from our SPR measurements. These data indicate that ApoE and tau compete for HS binding on the cell surface and demonstrate an ApoE-isoform dependent effect on the interactions between ApoE, Tau, and HS.

Figure 7.

ApoE and Tau compete for cell surface binding. (A) Incubation of ApoE3 with high concentrations of tau or with heparin elicits a statistically significant reduction in the binding of ApoE3 to the surface of MLECs. (B) ApoE4 cell surface binding is significantly inhibited by the addition of heparin, however tau inhibition is greatly reduced, and non-significant. Error bars are ± SEM.

NMR Titration Reveals H140, L144, and R147 as Key Residues for ApoE’s Interaction with 3-O-S Containing Glycans

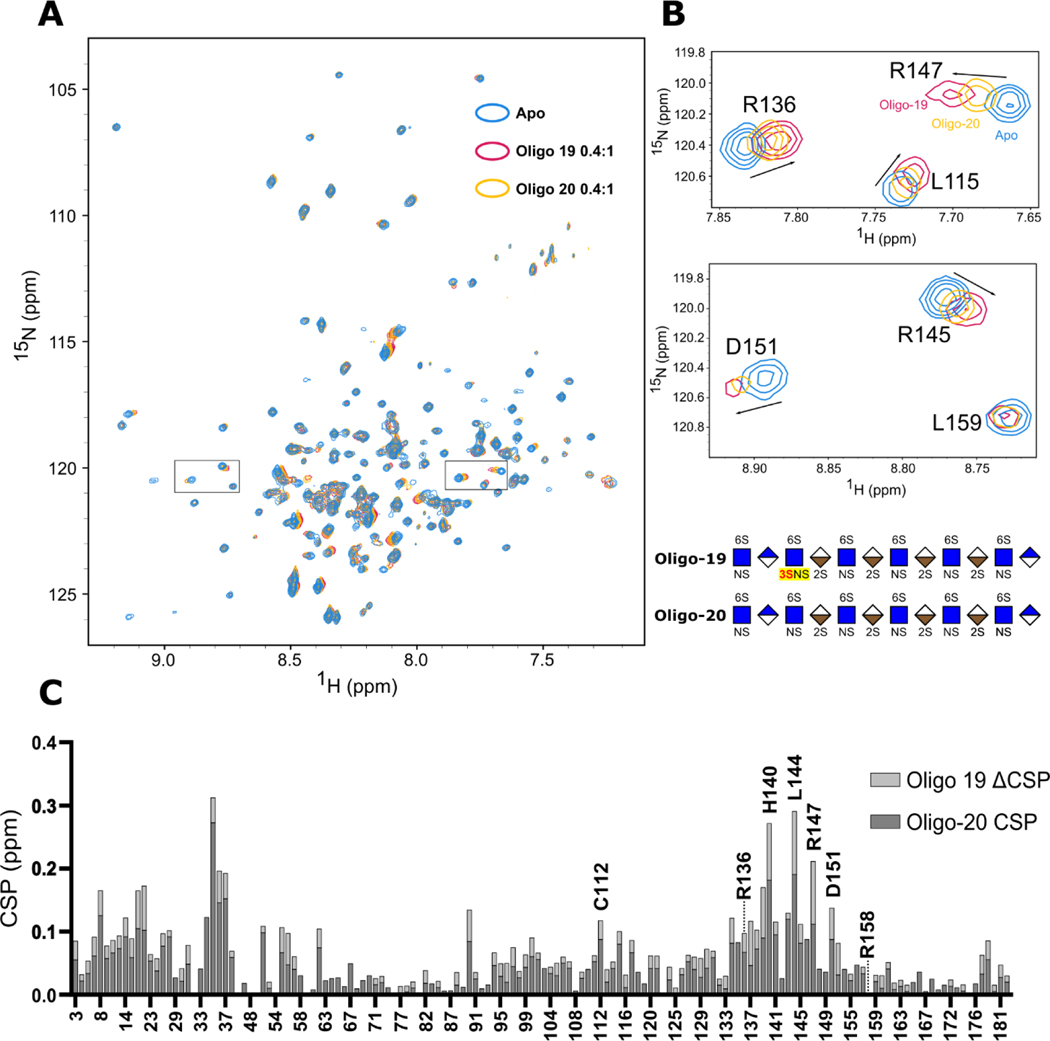

Next, we attempted to identify the specific regions of ApoE involved in the recognition of the 3-O-S group using NMR titration. We generated a construct consisting of N-terminal domain residues 1–183 of ApoE3 (ApoE3-NTD) to study this interaction. ApoE3-NTD retains the capacity to bind HS/heparin, albeit at reduced affinity, and contains the entire physiological HSPG binding site spanning residues 135–150[34,35].

HS oligos 19 and 20 were individually titrated into 0.3 mM samples of ~70% deuterated 2H, 15N ApoE3-NTD to at molar ratios of 0.1:1, 0.2:1, 0.4:1 ratios of glycan to protein (Figure 8 and Figure S4). Transverse Relaxation Optimized Spectroscopy (TROSY) NMR spectra were recorded on an 800 MHz Spectrometer (Bruker) and resonance assignments were obtained from previous work (BMRB entry 6524)[36].

Figure 8.

Mapping the ApoE/HS interaction and 3-O-S binding site with NMR. (A) Overlay of the 1H-15N TROSY spectra of N-terminal domain of ApoE3 before (Blue) and after 0.4:1 molar ratio addition of HS 12-mer Oligo-20 (Yellow) and Oligo-19 (Purple). (B) Zoomed-in NMR spectra of high CSP residues R136, R145, R147, and D151. (C) CSP Differences between spectra reveals a specific interaction between 3-O-S and residues R136, R139, H140, L144, R147, and D151 within the canonical receptor binding site of ApoE. The CSPs of the 0.1:1 and 0.2:1 titration points are shown in Figure S4.

Compared to the Apo spectrum (Figure 8A, blue peaks), significant chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) were observed following the addition of both oligo-19 (Figure 8A, purple peaks) and oligo-20 (Figure 8A, yellow peaks). As expected, These CSPs progressively increased over the course of the titration (Figure S4), with oligo-19 producing noticeably larger CSPs than oligo-20 in the vicinity of the canonical ApoE/HS binding site.

Spatially, these shifts were clustered in two areas: firstly, ApoE’s receptor binding site (R136-R150) in helix 4, particularly the canonical HSPG binding residues (R142-R147), and secondly a stretch of residues in helix 1 spanning roughly F33-L37 which interacts with helix 4 via R145. This is consistent with accepted models of the ApoE/HS interaction, which require the relocation of W34 to accommodate optimal binding[12].

Several isolated peaks with large CSPs are magnified in Figure 8B. The CSP differences (ΔCSP) between the oligo-19 and oligo-20 titrations were plotted against residue number (Figure 8C) to probe the 3-O-S recognition sites. Significant backbone ΔCSPs occurred in the receptor binding region of ApoE, particularly in the canonical HSPG binding site, with the greatest ΔCSPs occurring on H140, L144, and R147 (Figure 8C). Given the alignment of oligo-19 ΔCSP with areas of high CSP in the oligo-20 spectra, these results suggest the presence of the 3-O-S moiety likely enhances the existing interaction between ApoE and HS, rather than altering the binding mode.

Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease

Here we show that ApoE specifically recognizes 3-O-S modified HS. ApoE/HS interactions and cellular binding/uptake are greatly enhanced by 3-O-sulfation, as demonstrated by the results of the LMWHS array, SPR experiments, NMR titration, and cellular binding and uptake assays. Our SPR experiments confirmed that different ApoE isoforms exhibit altered affinities for heparin, with ApoE4 having the highest affinity, followed by ApoE3 > ApoE2 > ApoE3cc. We observed that structurally defined HS 7-mers and 12-mers containing 3-O-S groups bound preferentially to ApoE in a LMWHS array. Strikingly, one of these 3-O-S 7-mers (oligo-4) has a non-reducing end nearly identical to tetra-1, which is enriched in AD brain, lacking only a N-sulfo group on glucosamine 2 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Comparison of tetra-1 with ApoE binding 7-mers. The structures of the AD enriched tetrasaccharide motif tetra-1 strongly resemble the non-reducing end of the ApoE binding 3-O-S 7-mer oligo-4.

The impact of the 3-O-S group was further confirmed by competition SPR assays, which revealed an HS 12-mer with a single 3-O-S group (oligo-19) inhibited ApoE3/Heparin interactions with a nearly 6-fold lower IC50 than its 3-O-S lacking counterpart (oligo-20). The results of our NMR titration were also consistent with this, with oligo-19 producing elevated CSP within the HSPG binding site—particularly H140, R147, and R154—compared to oligo-20. Cell based binding and uptake experiments showed that the reduction of 3-O-S from Hs3st1 knockout significantly inhibited the binding and internalization of ApoE in Hs3st1−/− cells, suggesting that 3-O-S groups play a major role in cellular uptake of ApoE. Together these data demonstrate that ApoE recognizes 3-O-S groups in HS, making it the eighth protein with a specific interaction with 3-O-S discovered to date[19,37].

3-O sulfation of HS has been linked to AD through elevated levels of 3-O-sulfotransferases and 3-O-sulfated HS in AD brains, a genetic association between Hs3st1 and AD, and the specific interaction between tau and 3-O-S[21–25]. Adding to these molecular connections, the current study demonstrates the specific interaction between ApoE and 3-O-S. This is especially interesting, given that both ApoE and tau recognize 3-O-S and bind to LRP1 and HS for cellular uptake[10,33,38,39]. Tau and ApoE have similar binding patterns for in the HS glycan array, suggesting they recognize the same 3-O-S containing HS motifs, and thus should compete for HS binding. This is supported by our ApoE/Tau competition experiments, and further strengthens the molecular basis of the well-established phenomenon that ApoE can inhibit tau uptake in cell culture[33,40]. In one study, ApoE4 showed better inhibition of tau uptake than ApoE3 and ApoE2[40], which is consistent with our competition experiment, and with the higher binding affinity between HS and ApoE4 compared with ApoE3 and ApoE2, reflected in our SPR studies and previous work[11,12].

It is not completely understood how these data can be correlated to AD risk in ApoE isoforms, where ApoE4 promotes LOAD while ApoE2 and ApoEcc are protective against LOAD. A possible mechanism could be through the long-term alteration of brain interstitial tau level. In this model, ApoE occupies cell surface HS binding sites, inhibiting tau binding and the Tau/HS/LRP1 pathway for tau cellular uptake. Should the tau/HS/LRP1 pathway be involved in directing extracellular physiological tau into endosome/lysosome compartment for degradation, ApoE/tau competition would regulate the level of tau in brain interstitial fluid. The ApoE4 isoform would inhibit this tau clearance process, thereby enhancing the interstitial tau level in the brain. ApoE2 and ApoEcc in contrast would enhance tau clearance due to their weaker competition with tau/HS/LRP1 pathway. Because AD is a decades-long pathological process, even a small elevation in brain interstitial tau level by ApoE4 may have profound consequences such as misfolding and aggregation of tau. Alternatively, reduced tau clearance by HS-LRP1 pathway in neurons by ApoE4 may increase tau uptake by glia, which reportedly independent of HS[41], potentially contributing to neuroinflammation in AD.

Future studies should focus on characterizing the behavior of the ApoE/tau/HS ternary interaction, the role of lipidation and the ApoE C-terminus on ApoE/HS interactions in the context of AD, analyze potential isoform specific differences, and test whether extracellular tau levels are elevated in CSF and/or brain interstitial fluid of ε4 positive individuals as predicted in our proposed model.

Conclusion

To conclude, in this study we have shown that multiple AD relevant ApoE isoforms recognize 3-O-Sulfo groups in HS in a manner similar to tau. Isoforms of ApoE may modulate AD risk by competing with tau for HS binding to different extent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grant 1RF1AG069039 to C.W., R56 AG062344 to L.W. D.M. is supported by NIGMS training grant T32GM067545. Figures 2 and 9 were created using BioRender (www.biorender.com). William Fall and Eric Debaum assisted in the production of recombinant ApoE. Professor Jianjun Wang provided the original ApoE3 plasmid used for this research.

References:

- [1].Koutsodendris N, Nelson MR, Rao A, Huang Y, Annu. Rev. Pathol.: Mech. Dis. 2022, 17, 73–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 278, 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, Beekly D, Kuzma A, Gangadharan P, Wang L-S, Romero K, Arneric SP, Redolfi A, Orlandi D, Frisoni GB, Au R, Devine S, Auerbach S, Espinosa A, Boada M, Ruiz A, Johnson SC, Koscik R, Wang J-J, Hsu W-C, Chen Y-L, Toga AW, J. Am. Med. Assoc. Neurol. 2017, 74, 1178–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Corder EH, Saunders AM, Risch NJ, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Rimmler JB, Locke PA, Conneally PM, Schmader KE, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Nat. Genet. 1994, 7, 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O’Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Marino C, Chmielewska N, Saez-Torres KL, Amarnani D, Schultz AP, Sperling RA, Leyton-Cifuentes D, Chen K, Baena A, Aguillon D, Rios-Romenets S, Giraldo M, Guzmán-Vélez E, Norton DJ, Pardilla-Delgado E, Artola A, Sanchez JS, Acosta-Uribe J, Lalli M, Kosik KS, Huentelman MJ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Reiman RA, Luo J, Chen Y, Thiyyagura P, Su Y, Jun GR, Naymik M, Gai X, Bootwalla M, Ji J, Shen L, Miller JB, Kim LA, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1680–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weisgraber KH, Adv. Protein. Chem. 1994, 45, 249–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lane-Donovan C, Herz J, Trends Endocrinol. Metab, 28, 273–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bachmeier C, Shackleton B, Ojo J, Paris D, Mullan M, Crawford F, NeuroMol. Med. 2014, 16, 686–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mahley RW, Ji Z-S, Lipid Res J. 1999, 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Futamura M, Dhanasekaran P, Handa T, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S, Saito H, J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5414–5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Libeu CP, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Wehrli S, Hernáiz MJ, Capila I, Linhardt RJ, Raffaϊ RL, Newhouse YM, Zhou F, Weisgraber KH, J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 39138–39144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ray J, Gage FH, Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006, 31, 560–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kanekiyo T, Zhang J, Liu Q, Liu C-C, Zhang L, Bu G, J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 1644–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li JP, Kusche-Gullberg M, Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 325, 215–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Casu B, Lindahl U, Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2001, 57, 159–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Esko JD, Selleck SB, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 435–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Capila I, Linhardt RJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 390–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thacker BE, Xu D, Lawrence R, Esko JD, Matrix Biol. 2014, 35, 60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA-K, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist P-H, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Pontén F, Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Witoelar A, Rongve A, Almdahl IS, Ulstein ID, Engvig A, White LR, Selbæk G, Stordal E, Andersen F, Brækhus A, Saltvedt I, Engedal K, Hughes T, Bergh S, Bråthen G, Bogdanovic N, Bettella F, Wang Y, Athanasiu L, Bahrami S, le Hellard S, Giddaluru S, Dale AM, Sando SB, Steinberg S, Stefansson H, Snaedal J, Desikan RS, Stefansson K, Aarsland D, Djurovic S, Fladby T, Andreassen OA, Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, Sealock J, Karlsson IK, Hägg S, Athanasiu L, Voyle N, Proitsi P, Witoelar A, Stringer S, Aarsland D, Almdahl IS, Andersen F, Bergh S, Bettella F, Bjornsson S, Brækhus A, Bråthen G, de Leeuw C, Desikan RS, Djurovic S, Dumitrescu L, Fladby T, Hohman TJ, Jonsson P. v., Kiddle SJ, Rongve A, Saltvedt I, Sando SB, Selbæk G, Shoai M, Skene NG, Snaedal J, Stordal E, Ulstein ID, Wang Y, White LR, Hardy J, Hjerling-Leffler J, Sullivan PF, van der Flier WM, Dobson R, Davis LK, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Pedersen NL, Ripke S, Andreassen OA, Posthuma D, Nat. Genet 2019, 51, 404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhao J, Zhu Y, Song X, Xiao Y, Su G, Liu X, Wang Z, Xu Y, Liu J, Eliezer D, Ramlall TF, Lippens G, Gibson J, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Wang L, Wang C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1818–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sepulveda-Diaz JE, Alavi Naini SM, Huynh MB, Ouidja MO, Yanicostas C, Chantepie S, Villares J, Lamari F, Jospin E, van Kuppevelt TH, Mensah-Nyagan AG, Raisman-Vozari R, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Papy-Garcia D, Brain 2015, 138, 1339–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang Z, Arnold K, Dhurandahare VM, Xu Y, Pagadala V, Labra E, Jeske W, Fareed J, Gearing M, Liu J, Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2950–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yang J, Hsieh P-H, Liu X, Zhou W, Zhang X, Zhao J, Xu Y, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Liu J, Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 1743–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Horton M, Su G, Yi L, Wang Z, Xu Y, Pagadala V, Zhang F, Zaharoff DA, Pearce K, Linhardt RJ, Liu J, Glycobiology 2021, 31, 188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhang X, Pagadala V, Jester HM, Lim AM, Pham TQ, Goulas AMP, Liu J, Linhardt RJ, Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 7932–7940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arnold K, Xu Y, Sparkenbaugh EM, Li M, Han X, Zhang X, Xia K, Piegore M, Zhang F, Zhang X, Henderson M, Pagadala V, Su G, Tan L, Park PW, Stravitz RT, Key NS, Linhardt RJ, Pawlinski R, Xu D, Liu J, Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chen J, Li Q, Wang J, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 14813–14818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Goedert M, Weisgraber KH, Dong LM, Jakes R, Huang DY, Pericak-Vance M, Schmechel D, Roses AD, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 11183–11186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Qiu H, Shi S, Yue J, Xin M, v Nairn A, Lin L, Liu X, Li G, Archer-Hartmann SA, dela Rosa M, Galizzi M, Wang S, Zhang F, Azadi P, van Kuppevelt TH, v Cardoso W, Kimata K, Ai X, Moremen KW, Esko JD, Linhardt RJ, Wang L, Nat. Methods. 2018, 15, 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rauch JN, Luna G, Guzman E, Audouard M, Challis C, Sibih YE, Leshuk C, Hernandez I, Wegmann S, Hyman BT, Gradinaru V, Kampmann M, Kosik KS, Nature 2020, 580, 381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Yamauchi Y, Deguchi N, Takagi C, Tanaka M, Dhanasekaran P, Nakano M, Handa T, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S, Saito H, Biochemistry 2008, 47, 6702–6710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Saito H, Dhanasekaran P, Nguyen D, Baldwin F, Weisgraber KH, Wehrli S, Phillips MC, Lund-Katz S, J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14782–14787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xu C, Sivashanmugam A, Hoyt D, Wang J, Biomol J. NMR 2005, 32, 177–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thacker BE, Seamen E, Lawrence R, Parker MW, Xu Y, Liu J, vander Kooi CW, Esko JD, ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Christianson HC, Belting M, Matrix Biol. 2014, 35, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, Kotzbauer PT, Miller TM, Papy-Garcia D, Diamond MI, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, E3138–E3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cooper JM, Lathuiliere A, Migliorini M, Arai AL, Wani MM, Dujardin S, Muratoglu SC, Hyman BT, Strickland DK, J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Perea JR, López E, Díez-Ballesteros JC, Ávila J, Hernández F, Bolós M, Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.