Abstract

Opioids are a mainstay in acute pain management and produce their effects and side effects (e.g., tolerance, opioid-use disorder and immune suppression) by interaction with opioid receptors. I will discuss opioid pharmacology in some controversial areas of enquiry of anaesthetic relevance. The main opioid target is the µ (mu,MOP) receptor but other members of the opioid receptor family, δ (delta; DOP) and κ (kappa; KOP) opioid receptors also produce analgesic actions. These are naloxone-sensitive. There is important clinical development relating to the Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ (NOP) receptor, an opioid receptor that is not naloxone-sensitive. Better understanding of the drivers for opioid effects and side effects may facilitate separation of side effects and production of safer drugs. Opioids bind to the receptor orthosteric site to produce their effects and can engage monomer or homo-, heterodimer receptors. Some ligands can drive one intracellular pathway over another. This is the basis of biased agonism (or functional selectivity). Opioid actions at the orthosteric site can be modulated allosterically and positive allosteric modulators that enhance opioid action are in development. As well as targeting ligand-receptor interaction and transduction, modulating receptor expression and hence function is also tractable. There is evidence for epigenetic associations with different types of pain and also substance misuse. As long as the opioid narrative is defined by the ‘opioid crisis’ the drive to remove them could gather pace. This will deny use where they are effective, and access to morphine for pain relief in low income countries.

Keywords: epigenetics, ligand receptor interaction, opioid receptors, opioids, opioids and immune function, opioids and vascular

Opioids are a mainstay for pain management in the perioperative period.1 That they are effective in a range of types of nociceptive pain is clear where they modulate nociceptive information flow.2,3 Their use/efficacy more widely in chronic pain is controversial, particularly in neuropathic pain, but there is utility in the palliative care setting.4, 5, 6 Alongside the beneficial analgesic actions (antinociception in animals) opioids produce a troublesome set of adverse effects; these include ventilatory depression, constipation, immune suppression, tolerance and opioid use disorder.7 Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is also a significant clinical problem.8 Tolerance is often viewed at the centre of an adverse effect circle where increased dosing is required, but this produces more tolerance (and the other adverse effects). The focus of this review is to explore improved analgesia, but it is important to remember that tolerance can manifest secondary to disease progression (pseudo-tolerance) and can develop to many adverse effects; this includes ventilatory depression.

Opiates are natural products from the poppy but also encompass natural endogenous peptides (endorphins for example) whereas opioids are synthetic and not found in nature. Moreover, it is important to remember that not all opioids used in the clinic are the same.9 At therapeutic concentrations the vast majority display μ (mu, MOP) receptor selectivity. However, there is an approved synthetic peptide κ (kappa, KOP) receptor agonist difelikefalin, but this is used as a treatment for pruritis associated with chronic kidney disease.10 There are marked differences in clinical MOP ligands with respect to receptor potency (e.g. fentanyl is ∼80× more potent than morphine), efficacy (e.g. buprenorphine is a partial agonist) and in pharmacokinetics (e.g. rapid metabolism for remifentanil).11,12 If we consider immune suppression, morphine is strong, oxycodone is weaker and buprenorphine has almost no activity; clearly with respect to immune suppression opioids are not all the same.13,14 As covered below in in vitro studies, opioids at ‘equipotent’ concentrations can activate different signalling pathways. Considering the above arguments regarding marked differences in opioid pharmacological behaviour, Emery and Eitan state “… different opioids cannot be made equivalent by merely dose adjustment” other approaches are required.15

In this focused review I will cover opioid receptors and mechanisms in some controversial areas of enquiry in a digestible format and use this to frame attempts to design safer opioid medications.

Opioid receptors

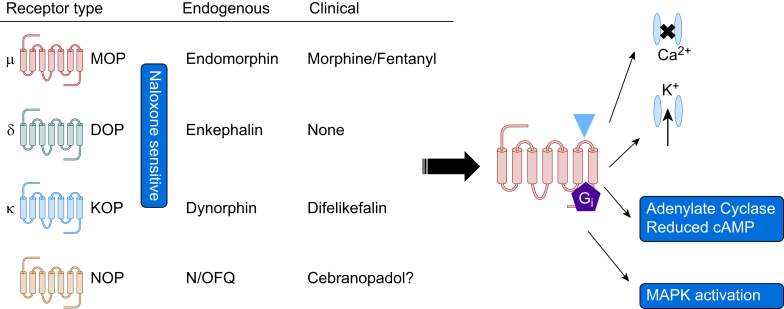

Opioid receptors are class A G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are part of a family; these are the classical naloxone-sensitive MOP, δ (delta, DOP) and KOP along with the non-classical receptor for nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) or NOP (Fig 1).16, 17, 18, 19 The consequences of receptor interactions will be discussed later. There is historic pharmacological evidence to suggest subtypes of opioid receptors and we have reviewed this in the past.20 The observation that knock-out of a single gene for each receptor results in full loss of function argues against subtypes but there is evidence for splice variants; with extensive data for MOP.20, 21, 22, 23 These splice variants can explain some differences in function but not the pre-cloning pharmacological suggestion of subtypes. Moreover, there are now knock-in animals expressing trackable genetic variants to address basic pharmacological-neurobehavioural responses.24 These animals have natural opioid gene sequence replaced with a modified sequence typically also encoding a fluorescent probe so that expression can be tracked or containing a single nucleotide polymorphism.24

Fig 1.

Opioid receptor classification and intracellular signal transduction. Opioid receptors are classified as μ (mu, MOP), δ (delta, DOP) and κ (kappa, KOP); these are naloxone-sensitive and possess endogenous peptide ligands. The fourth opioid receptor is that for nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) or NOP and is naloxone-insensitive. Clinically the main target is the MOP receptor where drugs such as morphine and fentanyl act. There is development for the NOP receptor with the mixed ligand cebranopadol and a KOP agonist, difelikefalin, has approval but only for pruritis. All opioid receptors couple to the inhibitory G protein Gi to close voltage gated Ca2+ channels, open inwardly rectifying K+ channels (to hyperpolarise), reduce the formation of cAMP and activate MAPK. With respect to the pain pathway these co-ordinated actions on ion channels result in a reduction in afferent nociceptive transmission and potentiation of descending inhibitory control.

All opioid receptors couple via the inhibitory heterotrimeric G protein (composed of α and β/γ subunits), Gi. Binding of the opioid ligand to the orthosteric site, facilitates G protein interaction and guanine nucleotide (guanosine diphosphate [GDP] for guanosine triphosphate [GTP]) exchange on the α subunit which dissociates from the β/γ dimer. The αi-GTP and variably β/γ dimer go on to inhibit adenylate cyclase to reduce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), open inwardly rectifying K+ channels to hyperpolarise, close voltage gated Ca2+ channels and activate mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Fig 1). The opioid signal is terminated by GTP metabolism back to GDP (the α subunit is also a GTPase enzyme) and after G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) phosphorylation of the receptor, arrestin recruitment and eventual endocytosis.16,25,26 Arrestin recruitment is important to consider further as there is (disputed) evidence that biased signalling towards G protein and away from arrestin has the potential to produce good quality analgesics with reduced adverse effect profiles.

Opioids modulate both the afferent and efferent parts of the pain pathway.3 By reducing neurotransmitter release they inhibit pain transmission from first order primary afferent to the second order ascending neurones. These actions are predominantly at K+ and Ca2+ channels where activation of the former enhances K+ efflux leading to hyperpolarisation, while inhibition of the latter reduces Ca2+ influx; both resulting in reduced transmitter release.25 They also affect second to third order transmission and enhance descending inhibitory control activity; the latter being through reduction in GABAergic inhibitory transmission.27 With respect to the NOP receptor and pain processing there is significant plasticity.28

In a seminal series of papers from the laboratory of Laura Bohn, the involvement of β-arrestin-2 in opioid antinociception and adverse effects was explored. To accomplish this, animals deficient in the gene for β-arrestin-2 production (knock-out or KO animals) were generated. KO animals showed greater antinociception and reduced tolerance.29,30 In a further series of studies, KO animals showed reduced ventilatory depression and inhibition of gastrointestinal (GI) motility.31 The overall proposal was that G protein action was beneficial and β-arrestin-2 action was not; this is the basis of functional selectivity or biased agonism covered below. Ligand bias is when a particular ligand can drive one transduction pathway over another. For the MOP receptor this has been questioned in a study by Kliewer and colleagues where fentanyl and morphine did not display reduced adverse effect profiles in KO animals along with some biased opioid receptor knock-in studies.32, 33, 34 β-Arrestin-2 bias has also been questioned by Gillis and colleagues with a more simple explanation based on efficacy; putative MOP biased agonists being partial agonists.35 In a reanalysis of the data from the Gillis paper, Stahl and Bohn conclude ‘The data in the Science Signaling paper provide strong corroborating evidence that G protein signaling bias may be a means of improving opioid analgesia while avoiding certain undesirable side effects’.36 Whilst of great interest pharmacologically and as a potential driver for early phase drug discovery, we have argued that from a therapeutic (drug to market) perspective it does not matter provided any new ligands provide therapeutic efficacy with low adverse effect profiles.

Opioid pharmaco-therapeutic strategies

Opioid receptors should be viewed as dynamic and existing in multiple conformations (e.g. active and inactive). Rather than being thought of as traditional keys to receptor locks, ligands (opioids) stabilise a particular conformation or the equilibrium between different conformations. Full agonists shift the equilibrium and stabilise the active form whereas partial agonists less so. Neutral antagonists simply block but do not activate receptors. For a receptor to exist in the active form in the absence of agonists it must possess constitutive activity. This can occur via a number of mechanisms and of interest here is a series of inherited diseases associated with variants in genes encoding GPCRs.37 Ligands that interact with this conformation and reduce activity are inverse agonists; they produce the opposite effect to the standard agonist. In experimental systems there are examples of inverse agonists at MOP, DOP, KOP and NOP; less so for NOP receptors, more so for DOP receptors.19,38, 39, 40, 41

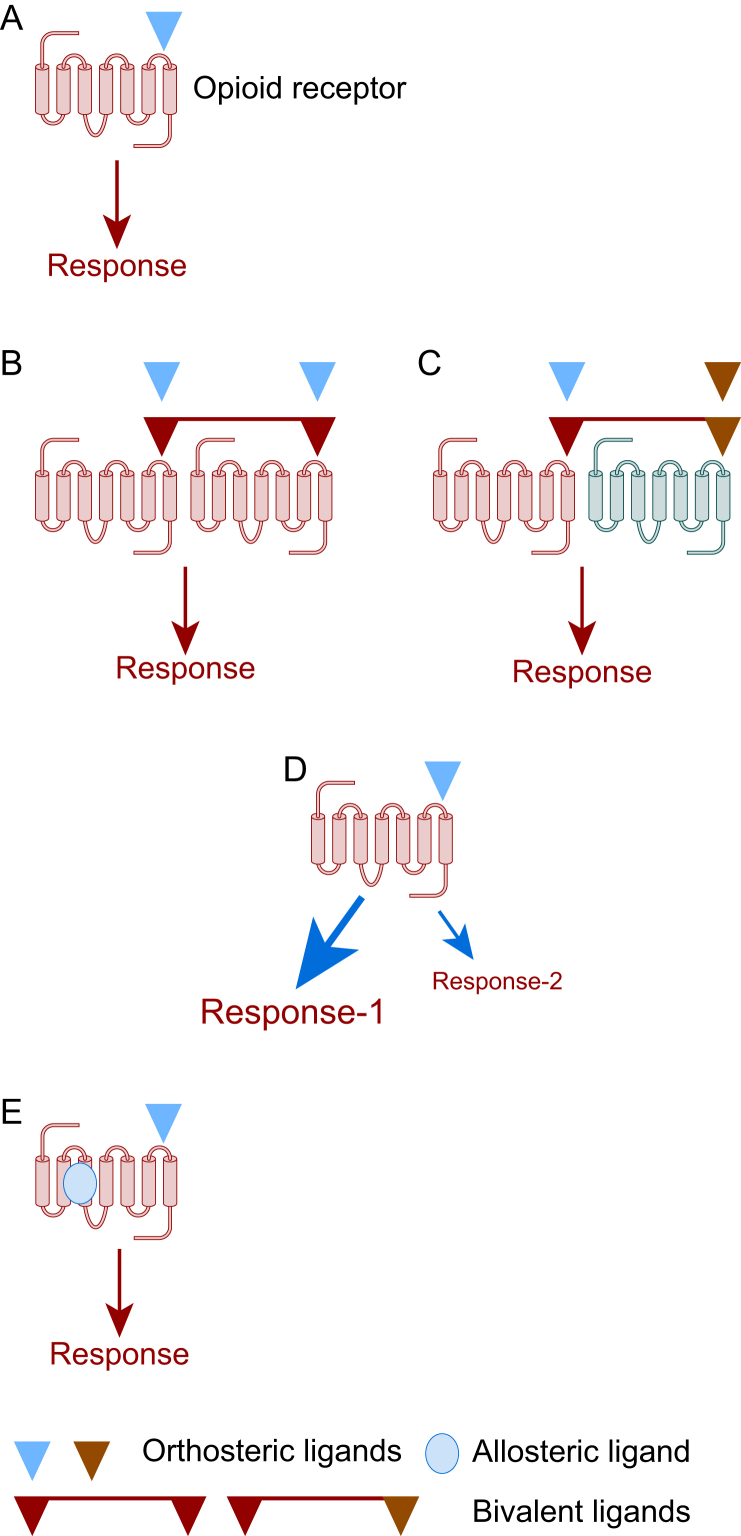

Opioids bind to opioid receptors at the orthosteric ligand binding site and some details of this ligand binding site can be obtained from the crystal structures; details of all four opioid receptors have been resolved.42, 43, 44, 45 Ligand interaction can modulate receptor function by targeting monomer receptors (the traditional view), dimer receptors (homo and hetero), using allosteric modulators and potentially driving one transduction pathway over another (Fig 2).46,47

Fig 2.

Modes of opioid ligand-receptor interaction (A) Represents a traditional opioid (e.g. morphine). interacting with the orthosteric site to produce a response (cellular as in Fig 1 and analgesia at the whole organism level). (B) Represents a homo-dimer (e.g. MOP–MOP) where two molecules of the same ligand interact with their respective orthosteric sites or a bivalent ligand interacts across the two monomers (C) Represents a hetero-dimer (e.g. MOP–DOP). where two different ligands interact with their respective orthosteric sites or a bivalent ligand interacts across the two monomers. It is also possible that orthosteric interaction at either receptor alone could modulate the activity of the other or the dimer complex (D) Represents putative biased agonism; ligand (e.g. TRV130 also known as oliceridine or trade name Olinvyk) drives G protein pathway/response-1 over arrestin pathway/response-2 to produce analgesia with reduced adverse effects. (E) Represents positive allosteric modulation. Allosteric modulator binding (e.g. BMS-986122) enhances the activity of typical orthosteric ligands.

To explore pharmacological classification a little more, in a whole organism context, efficacy is the size or strength of a given response in a particular tissue; for opioids this could be analgesia or ventilatory depression. Agonists that return a lower maximum response than a full (typically endogenous) agonist are partial agonists and have reduced efficacy. Can reduced efficacy be used to therapeutic effect (e.g. buprenorphine) and can differences in efficacy be used to explain the pharmacology of some of the newly produced opioid ligands?48

Multi-target strategy

Opioid receptors are unlikely to function alone. There is marked interaction between subtypes and this can be as a result of signalling interaction or the formation of dimers. The existence of opioid homodimers and heterodimers has been known for many years and there are some elegant studies demonstrating this using fluorescent tagged receptors and others using receptor probes.49, 50, 51, 52 For example, activating MOP whilst inhibiting DOP produces antinociception with a reduced adverse effect profile. This can be accomplished with a MOP agonist (morphine) and a DOP antagonist (naltrindole) or by using a bivalent ligand that interacts with both MOP and DOP simultaneously such as MOP agonist/DOP antagonist UFP-505.53,54 Whilst offering much there are no clinically available MOP–DOP bivalents. Moreover, there are data that show that the trivalent opioid agonist DPI-125 with marginal selectivity for DOP over MOP/KOP produces antinociception but with reduced ventilatory depression and abuse liability.55

There are other combinations that show potential and MOP–NOP is an example with substantial preclinical and clinical development. Cebranopadol is a mixed NOP-opioid ligand and we have reviewed this molecule in the past.56 The ligand is a high efficacy partial agonist at NOP and other opioid receptors; MOP being of particular interest here. This mixed (non-selective) opioid is antinociceptive in animal models of nociceptive (tail withdrawal), inflammatory (complete Freund's adjuvant) and neuropathic (nerve constriction) pain. Importantly this ligand was more potent (lower doses) in neuropathic pain; representing an area of significant therapeutic need. In animal models there was no ventilatory depression and tolerance developed very slowly.57 In humans cebranopadol showed efficacy in chronic low back pain, has low abuse potential and respiratory advantage.58, 59, 60 The CORAL phase III trial in cancer-related chronic pain compared cebranopadol with morphine; cebranopadol was non-inferior.61 In a longer term safety and efficacy trial, CORAL-XT reported cebranopadol to be safe and well tolerated in prolonged treatment.62

From this description of multi-targeting offering adverse effect advantage, non-selectivity is clearly being advocated. This goes against a large part of pharmacological dogma that drives selectivity to reduce adverse effect profile. With respect to opioids a rethink is needed; current development has already moved on (Fig 2).

Biased agonism

The fundamental principle governing biased agonism is that a particular ligand drives one signalling pathway over another and this produces therapeutic advantage.63,64 In the case of opioids, β-arrestin-2 KO animals display good quality antinociception but with reduced tolerance and other adverse effects.29,30 This has been questioned.32,33 The Trevena pharmaceutical company described a MOP receptor biased agonist; TRV130 or oliceridine that drove the Gi pathway over β-arrestin-2 recruitment, behaving as a G protein biased agonist. Based on these data it was presumed that it would have a reduced adverse effect profile. This was the case in preclinical studies and there was evidence of a similar effect in larger phase III clinical trials.63 These trials; APOLLO-1 (hard tissue, bunionectomy), APOLLO-2 (soft tissue, abdominoplasty) and Athena (safety and efficacy) facilitated Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of TRV130 as Olinvyk.63,65, 66, 67 There is documented respiratory advantage in humans.68 However, in a comprehensive series of experiments across several laboratories this biased agonist consistently returns as a partial agonist.32,33 G protein-coupled receptors support signal amplification. In the context of TRV130 if the G protein pathway is amplified and the arrestin pathway is not then a partial agonist could return a response at the former and not the latter; showing ‘apparent’ bias and the potential to misclassify. There is much debate in the literature covered above. From a therapeutic perspective this does not really matter as Olinvyk has some advantage over more conventional ‘non-biased’ ligands. Alongside TRV130 there are other G protein biased agonists such as PZM21.69 This is not in clinical development but is also returning as a partial agonist (Fig 2). In a very recent study Zhuang and colleagues used pharmacological-structural analysis to probe opioid interaction with MOP receptors.70 The MOP receptor is a GPCR and so composed of seven transmembrane (TM) domains; two areas were investigated, TM-3 face and TM-6/7 face of the ligand binding pocket. Importantly, TM-6/7 is involved in arrestin recruitment. Unbiased ligands (such as morphine and fentanyl) interact at both sites whereas putative biased agonists such as oliceridine and PZM21 preferentially interacted with TM-3.70

Allosteric modulators

As noted, opioids bind to the orthosteric site on the receptor to engage G protein and produce an output. There are additional binding sites on the opioid receptor to which other molecules can bind and these can modify the activity of drugs binding to the traditional orthosteric site; these are allosteric modulators.71,72 Allosteric modulators can be positive, negative or neutral (silent) but I will focus on positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) here. Consider two situations; (i) endogenous opioid action and (ii) therapeutic intravenous opioid administration. The former is highly selective in site of action and temporal profile but the latter is not, with widespread systemic distribution. A PAM (alone not effective) has the potential to enhance selective endogenous opioid action thereby either reducing the need for a systemic approach or reducing the systemic dose; the net effect is retention of analgesia but with reduced adverse effect profile. The PAM enhances the natural temporal profile produced, in this example by the endogenous opioid ligand. Interestingly, allosteric modulator effects depend on the orthosteric ligand being used; this is called probe dependence.72 Allosterism concepts are covered in detail in excellent reviews.72,73 There are molecules in various stages of development that target opioid receptors. There are a significant amount of data on the BMS (Bristol-Myers Squib) series of allosteric modulators where positive variants (BMS-986122) produce good quality antinociception (mice and rats) against noxious heat and inflammatory stimuli with reduced ventilatory depression, constipation and reward. The orthosteric site was engaged by endogenous (produced or enhanced with an enkephalinase inhibitor) opioids, methadone or morphine.74 A similar set of data has been produced (also in mice) using MS1, a known MOP–PAM and a molecule with similar chemistry identified from a commercial database (Fig 2).75,76

Opioid receptors, pain and epigenetics

In this review I have covered ligand regulation of receptor function and this makes sense from a pharmacological-therapeutic perspective. Opioid receptor expression and function can also be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms and if these changes can then be manipulated pharmacologically an extra layer to receptor regulation exists. According to the US National Institutes of Health National Human Genome Research Institute, epigenetics is ‘a field of study focused on changes in DNA that do not involve alterations to the underlying sequence’. Epigenetic regulation involves; histone modification, DNA methylation (adding a methyl group to cytosine in DNA) and the activity of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs are RNA molecules that are not translated into protein). Epigenetic regulation is driven by a family of writers (adding modifications), readers (recognising) and erasers (removing modifications).77 Epigenetic mechanisms are implicated in a range of diseases including cancer (covered in a journal special issue), asthma and multiple sclerosis and epigenetic changes can be driven by environmental exposure, diet and age.78, 79, 80, 81 Of relevance to anaesthesia, epigenetics has a role to play in the perioperative period: there are data showing epigenetic links to several types of pain and also opioid addiction-misuse which may have implications for the opioid misuse crisis.82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89

There is thorough recent coverage of epigenetic control of opioid receptors by Reid and colleagues and others, much of this is based on in vitro experiments.89,90 Some of the issues relevant to MOP as a mainstay therapeutic opioid target are covered below.

It is generally accepted that in opioid use disorder (addiction) there is hypermethylation of MOP receptor promoters (where transcription is initiated).91 What are the effects of shorter-term therapeutic use? This has been addressed by Sandoval-Sierra and colleagues who examined genome-wide DNA methylation in the MOP promoter.92 Thirty-three opioid-naive dental surgery patients were recruited and provided saliva samples pre-surgery then 2.7 [1.5] and 39 [10] days post-surgery. There was a demonstrable hypermethylation of the MOP promoter confirming epigenetic regulation with short-term therapeutic opioid use; this was a small study. If opioid misuse starts with therapeutic use then DNA hypermethylation can be thought of as a continuum; starting in the clinic then continuing with inappropriate or illicit use in the community. DNA methylation of MOP promoters results in reduced expression in the brain.93,94

Histones can be modified by acetyltransferases which add acetyl groups and Histone deacetylase (HDAC) remove them. Enhanced histone acetylation is reported in heroin users and there was a positive correlation with use history.95 HDACs have a role in several neuropathic pain syndromes where they are generally upregulated resulting in reduced histone acetylation.96 A study in rat bone cancer pain showed that the associated hyperalgesia is attenuated by the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A potentially restoring acetylation.97 In the spinal cord of these animals, bone cancer reduced the expression of MOP and this was restored by the HDAC inhibitor.97 The authors also showed in vitro in PC12 cells that trichostatin A increased MOP messenger RNA (mRNA) and receptor protein.97 In a rat model of pancreatitis pain HDAC2 expression was also increased and MOP activity in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord was reduced; the HDAC inhibitor AR-42 attenuated this effect on MOP receptor immunoreactivity.98 Ricolinostat (an HDAC inhibitor) is currently in phase II evaluation for painful diabetic neuropathy where the investigators are examining pain intensity; there are no results posted (NCT03176472).

An additional mechanism by which opioid receptor expression can be regulated is via the action of non-coding RNAs; these generally target specific mRNAs to effectively silence expression, the best known being microRNA (miRNA). In tolerance (in vivo and in vitro paradigms) the miRNA let-7 inhibits MOP translation; others are variously involved.93,99 In a recent systematic review Polli and colleagues explored miRNA in human pains.100 They report that a wide range of types of pain; complex regional pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, musculoskeletal pain, osteoarthritis and neuropathic pain, all have miRNA associations.100 We have considered HDACs above and there are data from other neurological diseases showing miRNA regulation of HDAC expression underscoring that epigenetic mechanisms should not be considered in isolation.101

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are involved in RNA stabilisation (including miRNAs) and the function of translated proteins involved in setting pain syndromes and in substance misuse. For example, an association with peripheral neuropathic pain, diabetic neuropathic pain, trigeminal neuralgia, central pain, inflammatory and cancer pain have been reviewed.102 Moreover, Michelhaugh and colleagues used Affymetrix microarrays to track five lncRNAs in the nucleus accumbens and these were upregulated in heroin users.103

Is there a causal link between epigenetic modification and opioid receptor expression in the brains of patients with opioid use disorder (and as part of the continuum in early therapeutic use) and can this explain opioid misuse? In 1994 Gabilondo and colleagues measured opioid radioligand binding to post-mortem brain tissue. Density in the frontal cortex, thalamus and caudate nucleus in heroin users was similar to that in controls.104 Ferrer-Alcon examined post-mortem opioid receptor density (immuno technique) in the frontal cortex of patients with opioid use disorder and controls. They showed a reduction of MOP receptor (∼25%) in brains of users.105 Using positron emission tomography (PET) and [11C]diprenorphine, Williams and colleagues explored opioid receptor binding in living brains during early abstinence; they reported increased binding.106 If during addiction receptor numbers decrease, then in early abstinence it is not unreasonable to suggest a compensatory upregulation and an increase in [11C]diprenorphine binding. To address the epigenetic issue more directly Knothe and colleagues measured MOP expression by mRNA and protein along with DNA methylation in 27 post-mortem brains.94 They showed a good correlation between receptor mRNA and protein but not with DNA methylation. In a series of in vitro experiments that they ran concurrently, DNA methylation was an order of magnitude greater—highlighting differences between systems. The authors suggest that epigenetic mechanisms (addiction-related hypermethylation) are unlikely to control expression in the human brain.94 Epigenetic modulation of neurobiological circuitry is an attractive area of enquiry.107 Pharmacological manipulation of these epigenetic processes (pharmacoepigenetics) has the potential to affect responses.

Opioids—opioid receptors and immunomodulation

The fact that opioids modulate the immune response has been known for many years and we and others have reviewed this in the past.13,108, 109, 110 It is worth re-emphasising that immune modulation is not the same for all opioids.14 Moreover, there are recent data suggesting an interaction between opioids, COVID infection and outcome.111, 112, 113, 114 The precise target site for immunomodulation is controversial with three areas of interest; none fully explains immune modulation. These are (i) the immune cell itself, (ii) modulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and (iii) central actions. Taking these in reverse order, reactive gliosis in central pain is documented as are opioid receptors on glia and minocycline (microglial inhibitor) is effective in neuropathic pain.115, 116, 117 HPA axis modulation (increased glucocorticoids) appears to show marked species variation along with variation relating to acute or chronic administration.13 Direct modulation of the immune cell is the most controversial where there is evidence for effects of opioids on immune cell function.108 In a series of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments we have failed to detect gene expression (mRNA) for any of the classical opioid receptors in mixed or separated human immune cell populations.118 Without mRNA then there can be no protein. In contrast we have detected mRNA for NOP and, in some cell types, its endogenous ligand N/OFQ.118,119 Moreover, we have recently used a novel fluorescent probe for NOP to detect active receptor protein and linked this to cellular function.120

Toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4s) respond to the products of Gram-negative bacteria and are important in immune signalling. These receptors are widely distributed and can be found on the vascular endothelium and in a wide range of tumour cells. This receptor seems an unlikely target to be discussing when considering opioids and immune modulation but there is substantial evidence showing a range of opioids interact with this receptor and in a naloxone-sensitive manner.121, 122, 123 In the absence of definitive evidence for opioid receptor protein on immune cells, TLR4 is a plausible surrogate that can explain immune modulation. In the search for opioid receptor-mediated immunomodulation have we been looking in the wrong place?124

Recent work from our laboratory has focussed on examining N/OFQ release from human polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells. We have developed a novel bioassay to measure the interaction of released N/OFQ with chimeric NOP receptors expressed in a biosensor layer of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. These receptors are forced to couple to Gαi/q proteins which, when activated, lead to measurable calcium responses.125 When polymorphs are overlaid onto sensor CHO cells and stimulated to degranulate with N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) we can detect real time N/OFQ release from single cells.126 In unpublished observations we have reported similar responses in isolated human B and T cells.

Collectively, it is clear that NOP activation can modulate immune function and immune cells can produce and release N/OFQ. For classical opioids we should look elsewhere; TLR4 is a compelling target. Immune cells are also capable of the production and release of a range of opioid peptides for classical opioid receptors and these can then interact with neuronal opioid receptors producing a neuro-immune axis,127 and as discussed below for NOP–N/OFQ, an immune-vascular axis.

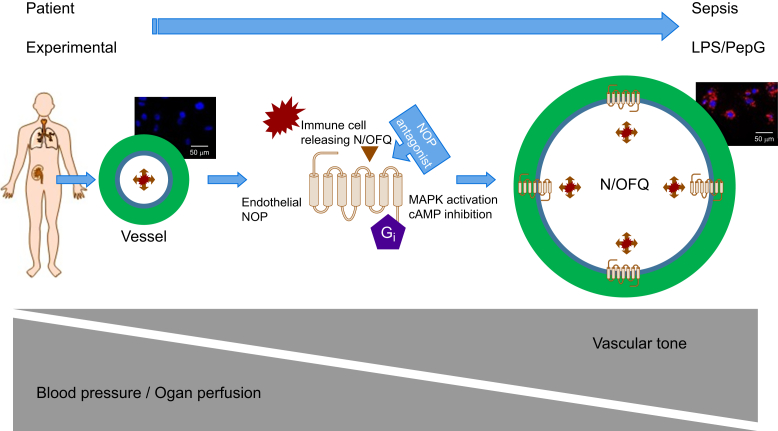

Sepsis and an immune-vascular axis; involvement of the N/OFQ opioid receptor

Sepsis is ‘a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host immune response to infection’.128 According to the UK sepsis trust [https://sepsistrust.org] there are 245,000 cases of sepsis each year, while 40% of sepsis survivors suffer permanent, life-changing after-effects and five people die with sepsis every hour. The dysregulated host response in sepsis and septic shock has profound effects on the cardiovascular system resulting in hypotension, organ hypoperfusion and resultant dysfunction/failure. This suggests cross-talk between immune and cardiovascular systems; an immune–vascular axis.

In a retrospective study we measured N/OFQ concentrations in critically ill patients in the ICU and compared these with their own recovery data and a matched control group of volunteers. We reported increased plasma N/OFQ concentrations over the first two days of admission to the ICU.129 Animal models have explored survival outcomes. In rats with caecal ligation and puncture peritoneal sepsis, mortality increased if N/OFQ was administered. Conversely, mortality was improved if the NOP antagonist UFP-101 was administered.130 The implications of these data are that N/OFQ is increased in sepsis (agrees with human ICU data) and that NOP antagonism might be beneficial as an adjunct to treat sepsis-induced hypotension. Indeed, in the rat microcirculation in vivo, we have shown that N/OFQ produced hypotension, vasodilation and macromolecular leak which was reversed by the NOP antagonist UFP-101.

In a recent study we examined the expression of NOP on human vascular endothelium cells (HUVECs) and vascular smooth muscle. We showed that unstimulated endothelium expressed mRNA for the NOP receptor but expression of functional protein required treatment with lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan G (LPS/PepG) as an in vitro sepsis mimic. These upregulated NOP receptors are functionally active.131 In sepsis we hypothesise that immune cells release N/OFQ and that this then activates upregulated NOP receptors on the endothelium to support vasodilation and the sequelae of reduced blood pressure; this is an immune-vascular axis (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Immuno-vascular axis. In human sepsis N/OFQ is increased and there is a profound decrease in blood pressure associated with vasodilation. Vasodilation can be observed in experimental animal models of sepsis. In the non-septic state we have shown that whilst the vascular endothelium (blue inner part of the vessel) expressed mRNA for NOP receptors this is not converted to functional NOP receptor protein until the endothelium is made septic, in this case with lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan G (LPS/PepG). Receptor expression is seen as increased binding of the red fluorescent probe N/OFQATTO594 in the micrographs (in the resting state on the left only blue-stained nuclei are visible while in the septic tissue on the right, red binding is seen). We have also shown that immune cells produce and release N/OFQ which, in the absence of stimuli (sepsis) have no target. When the receptor is present, released N/OFQ will activate NOP receptor and through Gi-mediated events produce vasodilation, and a decrease in blood pressure. In order to prevent this N/OFQ-NOP receptor-mediated dilation a NOP receptor antagonist would be the (adjuvant) therapy of choice and there is evidence from animal models that such treatment improved outcome.

Opioid-free analgesia

One school of thought to avoid opioid adverse effects (therapeutic and societal) is to eliminate them with the use of opioid-free analgesia. This seems a rather drastic course of action for a drug class that apparently has good efficacy when used for the right indication, at the right time and for the correct duration. There is literature exploring personalisation of opioid-free anaesthesia; or at least posing the question.132 There is a wide literature base exploring opioid-free techniques per se and a critical review recently compared opioid and opioid-free approaches concluding that ‘The data indicate that opioid-free strategies, however noble in their cause, do not fully acknowledge the limitations and gaps within the existing evidence and clinical practice considerations.’133, 134, 135, 136

Opioid free is worthy of some further consideration here; no opioids at all, no intraoperative opioids, no postoperative opioids or combinations? Olausson and colleagues performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs published between 2000 and 2021 looking at opioid-free general anaesthesia.137 The data were derived from 26 trials of 1,934 patients and concluded that opioid-free anaesthesia reduced postoperative adverse effects.137 Opioids were used in the postoperative period but their use was significantly lower in the opioid-free anaesthesia group. Fiore and colleagues also performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of opioid and opioid-free analgesia after surgical discharge. Their data were derived from 47 trials published after 1 January 1990 and which enrolled 6,607 patients. Opioid prescribing (compared with opioid free) did not reduce postoperative pain although the authors noted that ‘Data were largely derived from low-quality trials’.134,138 So what is the optimum? Reduced opioid multimodal intraoperative analgesia followed by limited postoperative (multimodal) use and transition to opioid free? Is this optimal for all procedures? There is guidance.1

If this is all considered in the context of poor opioid stewardship (clinical use/prescribing) and the resulting well documented ‘opioid crisis’ then the scene is set for a potential withdrawal of opioids from routine use. This will deny a large patient population access to effective acute pain medications and in the case of cheap generics, effective analgesia in countries with developing health provision. In their report ‘Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report’ Knaul and colleagues state of the 298.5 metric tonnes of morphine-equivalent opioids, 0.03% are distributed to low income countries.139 Moreover, using Haiti as an index country, the same report concludes 99% of (opioid) need goes unmet.

Conclusions

As pharmacologists and perioperative clinicians we have much to offer in the design of safer opioids (earlier part of this review), but the global community of researchers and perioperative practitioners need to tread carefully. Opioid medicine withdrawal might fix one important and perceived problem but then create another of monstrous proportions. What is clear is that the opioid epidemic has created a ‘hostile’ opioid environment; this hostility is not just from regulators but also from wider society and lawmakers [https://www.medpagetoday.com/painmanagement/opioids/84431]. Whatever mechanisms underlie the actions of opioids and on the backdrop of the opioid crisis, it is clear that the route to market for any new opioid-based analgesics will not be straightforward; we must not give up.

Acknowledgements

Over the last >25 yrs, work on opioids in the authors' laboratory has been externally supported by British Journal of Anaesthesia/Royal College of Anaesthetists, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Vascular Anaesthesia Society of Great Britain and Ireland and Hope Against Cancer. There was no specific funding for this article. I am grateful to Professor G. Calo of University of Padova for helpful comments.

Declaration of interest

DGL is Chief Scientific Officer at Cellomatics, a SME-CRO and chairs the Board of British Journal of Anaesthesia.

Handling Editor: Phil Hopkins

References

- 1.Srivastava D., Hill S., Carty S., et al. Surgery and opioids: evidence-based expert consensus guidelines on the perioperative use of opioids in the United Kingdom. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busse J.W., Wang L., Kamaleldin M., et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;320:2448–2460. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks J., Tracey I. From nociception to pain perception: imaging the spinal and supraspinal pathways. J Anat. 2005;207:19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNicol E.D., Midbari A., Eisenberg E. Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD006146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montgomery L.S. Pain management with opioids in adults. J Neurosci Res. 2022;100:10–18. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falk J., Thomas B., Kirkwood J., et al. PEER systematic review of randomized controlled trials management of chronic neuropathic pain in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2021;67:E130–E140. doi: 10.46747/cfp.6705e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul A.K., Smith C.M., Rahmatullah M., et al. Opioid analgesia and opioid-induced adverse effects: a review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14:1091. doi: 10.3390/ph14111091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colvin L.A., Fallon M.T. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a clinical challenge. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:125–127. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drewes A.M., Jensen R.D., Nielsen L.M., et al. Differences between opioids: pharmacological, experimental, clinical and economical perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:60–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeks E.D. Difelikefalin: first approval. Drugs. 2021;81:1937–1944. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01619-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trescot A.M., Datta S., Lee M., Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008;11 S133–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Servin F.S., Billard V. In: Modern anesthetics. Schüttler J., Schwilden H., editors. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2008. Remifentanil and other opioids; pp. 283–311. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Hashimi M., Scott S.W.M., Thompson J.P., Lambert D.G. Opioids and immune modulation: more questions than answers. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:80–88. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franchi S., Moschetti G., Amodeo G., Sacerdote P. Do all opioid drugs share the same immunomodulatory properties? A review from animal and human studies. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2914. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emery M.A., Eitan S. Members of the same pharmacological family are not alike: different opioids, different consequences, hope for the opioid crisis? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:428–449. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert D.G. The nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor: a target with broad therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:694. doi: 10.1038/nrd2572. –U11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald J., Lambert D.G. Opioid receptors. BJA Educ. 2015;15:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein C. Opioid receptors. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:433–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062613-093100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toll L., Bruchas M.R., Calo G., Cox B.M., Zaveri N.T. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor structure, signaling, ligands, functions, and interactions with opioid systems. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:419–457. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietis N., Rowbotham D.J., Lambert D.G. Opioid receptor subtypes: fact or artifact? Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:8–18. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kieffer B.L., Gaveriaux-Ruff C. Exploring the opioid system by gene knockout. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:285–306. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeilhofer H.U., Calo G. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ and its receptor – potential targets for pain therapy? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:423–429. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasternak G.W., Pan Y.X. Mu opioids and their receptors: evolution of a concept. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:1257–1317. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Degrandmaison J., Rochon-Hache S., Parent J.L., Gendron L. Knock-in mouse models to investigate the functions of opioid receptors in vivo. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.807549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Hasani R., Bruchas M.R. Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor-dependent signaling and behavior. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:1363–1381. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318238bba6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James A., Williams J. Basic opioid pharmacology an update. Br J Pain. 2020;14:115–121. doi: 10.1177/2049463720911986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fields H. State-dependent opioid control of pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder W., Lambert D.G., Ko M.C., Koch T. Functional plasticity of the N/OFQ-NOP receptor system determines analgesic properties of NOP receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:3777–3800. doi: 10.1111/bph.12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohn L.M., Gainetdinov R.R., Lin F.-T., Lefkowitz R.J., Caron M.G. μ-Opioid receptor desensitization by β-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–723. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohn L.M., Lefkowitz R.J., Gainetdinov R.R., Peppel K., Caron M.G., Lin F.T. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science. 1999;286:2495–2498. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raehal K.M., Walker J.K., Bohn L.M. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1195–1201. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillis A., Kliewer A., Kelly E., et al. Critical assessment of G protein-biased agonism at the μ-opioid receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kliewer A., Gillis A., Hill R., et al. Morphine-induced respiratory depression is independent of β-arrestin2 signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:2923–2931. doi: 10.1111/bph.15004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He L., Gooding S.W., Lewis E., Felth L.C., Gaur A., Whistler J.L. Pharmacological and genetic manipulations at the μ-opioid receptor reveal arrestin-3 engagement limits analgesic tolerance and does not exacerbate respiratory depression in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:2241–2249. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01054-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillis A., Gondin A.B., Kliewer A., et al. Low intrinsic efficacy for G protein activation can explain the improved side effect profiles of new opioid agonists. Sci Signal. 2020;13 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaz3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stahl E.L., Bohn L.M. Low intrinsic efficacy alone cannot explain the improved side effect profiles of new opioid agonists. Biochemistry. 2022;61:1923–1935. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiegel A.M., Weinstein L.S. Inherited diseases involving G proteins and G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:27–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang D., Raehal K.M., Bilsky E.J., Sadée W. Inverse agonists and neutral antagonists at μ opioid receptor (MOR): possible role of basal receptor signaling in narcotic dependence. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1590–1600. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirayama S., Iwai T., Higashi E., et al. Discovery of δ opioid receptor full inverse agonists and their effects on restraint stress-induced cognitive impairment in mice. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10:2237–2242. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D., Sun X., Sadee W. Different effects of opioid antagonists on μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptors with and without agonist pretreatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:544–552. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahmoud S., Margas W., Trapella C., Calo G., Ruiz-Velasco V. Modulation of silent and constitutively active nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors by potent receptor antagonists and Na+ ions in rat sympathetic neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:804–817. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Granier S., Manglik A., Kruse A.C., et al. Structure of the delta-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature. 2012;485:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manglik A., Kruse A.C., Kobilka T.S., et al. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson A.A., Liu W., Chun E., et al. Structure of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor in complex with a peptide mimetic. Nature. 2012;485:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu H., Wacker D., Mileni M., et al. Structure of the human kappa-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature. 2012;485:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenakin T. Principles: receptor theory in pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenakin T. A scale of agonism and allosteric modulation for assessment of selectivity, bias, and receptor mutation. Mol Pharmacol. 2017;92:414–424. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.108787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gudin J., Fudin J. A narrative pharmacological review of buprenorphine: a unique opioid for the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Ther. 2020;9:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-00143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Costantino C.M., Gomes I., Stockton S.D., Lim M.P., Devi L.A. Opioid receptor heteromers in analgesia. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012;14:e9. doi: 10.1017/erm.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jordan B.A., Devi L.A. G-protein-coupled receptor heterodimerization modulates receptor function. Nature. 1999;399:697–700. doi: 10.1038/21441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans R.M., You H., Hameed S., et al. Heterodimerization of ORL1 and opioid receptors and its consequences for N-type calcium channel regulation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1032–1040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bird M.F., McDonald J., Horley B., et al. MOP and NOP receptor interaction: studies with a dual expression system and bivalent peptide ligands. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdelhamid E.E., Sultana M., Portoghese P.S., Takemori A.E. Selective blockage of delta-opioid receptors prevents the development of morphine-tolerance and dependence in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dietis N., Niwa H., Tose R., et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the bifunctional mu and delta opioid receptor ligand UFP-505. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2881–2896. doi: 10.1111/bph.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yi S.P., Kong Q.H., Li Y.L., et al. The opioid receptor triple agonist DPI-125 produces analgesia with less respiratory depression and reduced abuse liability. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:977–989. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calo G., Lambert D.G. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor ligands and translational challenges: focus on cebranopadol as an innovative analgesic. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:1105–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linz K., Christoph T., Tzschentke T.M., et al. Cebranopadol: a novel potent analgesic nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide and opioid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349:535–548. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Christoph A., Eerdekens M.H., Kok M., Volkers G., Freynhagen R. Cebranopadol, a novel first-in-class analgesic drug candidate: first experience in patients with chronic low back pain in a randomized clinical trial. Pain. 2017;158:1813–1824. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gohler K., Sokolowska M., Schoedel K.A., et al. Assessment of the abuse potential of cebranopadol in nondependent recreational opioid users a phase 1 randomized controlled study. J Clin Psychopharm. 2019;39:46–56. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dahan A., Boom M., Sarton E., et al. Respiratory effects of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide and opioid receptor agonist, cebranopadol, in healthy human volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:697–707. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eerdekens M.H., Kapanadze S., Koch E.D., et al. Cancer-related chronic pain: investigation of the novel analgesic drug candidate cebranopadol in a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial. Eur J Pain. 2019;23:577–588. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koch E.D., Kapanadze S., Eerdekens M.H., et al. Cebranopadol, a novel first-in-class analgesic drug candidate: first experience with cancer-related pain for up to 26 weeks. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019;58:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azzam A.A.H., Lambert D.G. Preclinical discovery and development of oliceridine (Olinvyk ®) for the treatment of post-operative pain. Expert Opin Drug Dis. 2022;17:215–223. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2022.2008903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kenakin T., Christopoulos A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:205–216. doi: 10.1038/nrd3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Viscusi E.R., Skobieranda F., Soergel D.G., Cook E., Burt D.A., Singla N. APOLLO-1: a randomized placebo and active-controlled phase III study investigating oliceridine (TRV130), a G protein-biased ligand at the μ-opioid receptor, for management of moderate-to-severe acute pain following bunionectomy. J Pain Res. 2019;12:927–943. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S171013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singla N.K., Skobieranda F., Soergel D.G., et al. APOLLO-2: a randomized, placebo and active-controlled phase iii study investigating oliceridine (TRV130), a G protein-biased ligand at the μ-opioid receptor, for management of moderate to severe acute pain following abdominoplasty. Pain Pract. 2019;19:715–731. doi: 10.1111/papr.12801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergese S.D., Brzezinski M., Hammer G.B., et al. ATHENA: a phase 3, open-label study of the safety and effectiveness of oliceridine (TRV130), a G-protein selective agonist at the μ-opioid receptor, in patients with moderate to severe acute pain requiring parenteral opioid therapy. J Pain Res. 2019;12:3113–3126. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S217563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dahan A., van Dam C.J., Niesters M., et al. Benefit and risk evaluation of biased mu-receptor agonist oliceridine versus morphine. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:559–568. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manglik A., Lin H., Aryal D.K., et al. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature. 2016;537:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature19112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhuang Y., Wang Y., He B., et al. Molecular recognition of morphine and fentanyl by the human μ-opioid receptor. Cell. 2022;185:4361–4375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.041. e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kenakin T.P. Ligand detection in the allosteric world. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:119–130. doi: 10.1177/1087057109357789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Livingston K.E., Traynor J.R. Allostery at opioid receptors: modulation with small molecule ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2846–2856. doi: 10.1111/bph.13823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burford N.T., Traynor J.R., Alt A. Positive allosteric modulators of the mu-opioid receptor: a novel approach for future pain medications. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:277–286. doi: 10.1111/bph.12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kandasamy R., Hillhouse T.M., Livingston K.E., et al. Positive allosteric modulation of the mu-opioid receptor produces analgesia with reduced side effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2000017118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bisignano P., Burford N.T., Shang Y., et al. Ligand-based discovery of a new scaffold for allosteric modulation of the mu-opioid receptor. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:1836–1843. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pryce K.D., Kang H.J., Sakloth F., et al. A promising chemical series of positive allosteric modulators of the μ-opioid receptor that enhance the antinociceptive efficacy of opioids but not their adverse effects. Neuropharmacology. 2021;195 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Biswas S., Rao C.M. Epigenetic tools (The Writers, the Readers and the Erasers) and their implications in cancer therapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;837:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skourti E., Dhillon P. Cancer epigenetics: promises and pitfalls for cancer therapy. Febs J. 2022;289:1156–1159. doi: 10.1111/febs.16395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.DeVries A., Vercelli D. Epigenetic mechanisms in asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:S48–S50. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-420MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kular L., Jagodic M. Epigenetic insights into multiple sclerosis disease progression. J Intern Med. 2020;288:82–102. doi: 10.1111/joim.13045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cavalli G., Heard E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature. 2019;571:489–499. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lirk P., Fiegl H., Weber N.C., Hollmann M.W. Epigenetics in the perioperative period. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:2748–2755. doi: 10.1111/bph.12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johansen L.M., Gerra M.C., Arendt-Nielsen L. Time course of DNA methylation in pain conditions: from experimental models to humans. Eur J Pain. 2021;25:296–312. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liang L.L., Lutz B.M., Bekker A., Tao Y.X. Epigenetic regulation of chronic pain. Epigenomics. 2015;7:235–245. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luo D.Z., Li X.H., Tang S.M., et al. Epigenetic modifications in neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2021;17 doi: 10.1177/17448069211056767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Topham L., Gregoire S., Kang H., et al. The transition from acute to chronic pain: dynamic epigenetic reprogramming of the mouse prefrontal cortex up to 1 year after nerve injury. Pain. 2020;161:2394–2409. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Browne C.J., Godino A., Salery M., Nestler E.J. Epigenetic mechanisms of opioid addiction. Biol Psychiat. 2020;87:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gerra M.C., Dallabona C., Arendt-Nielsen L. Epigenetic alterations in prescription opioid misuse: new strategies for precision pain management. Genes (Basel) 2021;12:1226. doi: 10.3390/genes12081226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reid K.Z., Lemezis B.M., Hou T.C., Chen R. Epigenetic modulation of opioid receptors by drugs of abuse. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms231911804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wei L.N., Loh H.H. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of opioid receptor genes: present and future. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 2011;51:75–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Blackwood C.A., Cadet J.L. Epigenetic and genetic factors associated with opioid use disorder: are these relevant to African American populations. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.798362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sandoval-Sierra J.V., Garcia F.S.I., Brooks J.H., Derefinko K.J., Mozhui K. Effect of short-term prescription opioids on DNA methylation of the OPRM1 promoter. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:76. doi: 10.1186/s13148-020-00868-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cuitavi J., Hipolito L., Canals M. The life cycle of the mu-opioid receptor. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46:315–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Knothe C., Oertel B.G., Ultsch A., et al. Pharmacoepigenetics of the role of DNA methylation in mu-opioid receptor expression in different human brain regions. Epigenomics. 2016;8:1583–1599. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Egervari G., Landry J., Callens J., et al. Striatal H3K27 acetylation linked to glutamatergic gene dysregulation in human heroin abusers holds promise as therapeutic target. Biol Psychiat. 2017;81:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Romanelli M.N., Borgonetti V., Galeotti N. Dual BET/HDAC inhibition to relieve neuropathic pain: recent advances, perspectives, and future opportunities. Pharmacol Res. 2021;173 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hou X., Weng Y., Ouyang B., et al. HDAC inhibitor TSA ameliorates mechanical hypersensitivity and potentiates analgesic effect of morphine in a rat model of bone cancer pain by restoring mu-opioid receptor in spinal cord. Brain Res. 2017;1669:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liao Y.H., Wang J., Wei Y.Y., et al. Histone deacetylase 2 is involved in μ-opioid receptor suppression in the spinal dorsal horn in a rat model of chronic pancreatitis pain. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:2803–2810. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Melo Z., Ishida C., Goldaraz M.P., Rojo R., Echavarria R. Novel roles of non-coding RNAs in opioid signaling and cardioprotection. Noncoding RNA. 2018;4:22. doi: 10.3390/ncrna4030022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Polli A., Godderis L., Ghosh M., Ickmans K., Nijs J. Epigenetic and miRNA expression changes in people with pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2020;21:763–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bourassa M.W., Ratan R.R. The interplay between microRNAs and histone deacetylases in neurological diseases. Neurochem Int. 2014;77:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li Z., Li X.J., Jian W.L., Xue Q.S., Liu Z.H. Roles of long non-coding RNAs in the development of chronic pain. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.760964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Michelhaugh S.K., Lipovich L., Blythe J., Jia H., Kapatos G., Bannon M.J. Mining Affymetrix microarray data for long non-coding RNAs: altered expression in the nucleus accumbens of heroin abusers. J Neurochem. 2011;116:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gabilondo A.M., Meana J.J., Barturen F., Sastre M., Garciasevilla J.A. Mu-opioid receptor and alpha(2)-adrenoceptor agonist binding-sites in the postmortem brain of heroin-addicts. Psychopharmacology. 1994;115:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02244763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ferrer-Alcon M., La Harpe R., Garcia-Sevilla J.A. Decreased immunodensities of micro-opioid receptors, receptor kinases GRK 2/6 and beta-arrestin-2 in postmortem brains of opiate addicts. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;121:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Williams T.M., Daglish M.R.C., Lingford-Hughes A., et al. Brain opioid receptor binding in early abstinence from opioid dependence: positron emission tomography study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:63–69. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Blackwood C.A., Cadet J.L. The molecular neurobiology and neuropathology of opioid use disorder. Curr Res Neurobiol. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.crneur.2021.100023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eisenstein T.K. The role of opioid receptors in immune system function. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2904. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Plein L.M., Rittner H.L. Opioids and the immune system - friend or foe. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2717–2725. doi: 10.1111/bph.13750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sacerdote P. Opioids and the immune system. Palliat Med. 2006;20:S9–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ataei M., Shirazi F.M., Lamarine R.J., Nakhaee S., Mehrpour O. A double-edged sword of using opioids and COVID-19: a toxicological view. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15:91. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Eagleton M., Stokes S., Fenton F., Keenan E. Does opioid substitution treatment have a protective effect on the clinical manifestations of COVID-19? Comment on Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: e382–3. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:e114. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.11.027. –e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Eagleton M., Stokes S., Fenton F., Keenan E. Therapeutic potential of long-acting opioids and opioid antagonists for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:E212. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.08.022. –E4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lambert D.G. Opioids and the COVID-19 pandemic: does chronic opioid use or misuse increase clinical vulnerability? Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:E382. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.004. –E3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kadhim S., McDonald J., Lambert D.G. Opioids, gliosis and central immunomodulation. J Anesth. 2018;32:756–767. doi: 10.1007/s00540-018-2534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Machelska H., Celik M.O. Opioid receptors in immune and glial cells-implications for pain control. Front Immunol. 2020;11:300. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shin D.A., Kim T.U., Chang M.C. Minocycline for controlling neuropathic pain: a systematic narrative review of studies in humans. J Pain Res. 2021;14:139–145. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S292824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Al-Hashimi M., McDonald J., Thompson J.P., Lambert D.G. Evidence for nociceptin/orphanin FQ (NOP) but not mu (MOP), delta (DOP) or kappa (KOP) opioid receptor mRNA in whole human blood. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:423–429. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Williams J.P., Thompson J.P., Rowbotham D.J., Lambert D.G. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells produce pre-pro-nociceptin/orphanin FQ mRNA. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:865–866. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181617646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bird M.F., Guerrini R., Willets J.M., Thompson J.P., Calo G., Lambert D.G. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) conjugated to ATTO594: a novel fluorescent probe for the N/OFQ (NOP) receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:4496–4506. doi: 10.1111/bph.14504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hutchinson M.R., Shavit Y., Grace P.M., Rice K.C., Maier S.F., Watkins L.R. Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:772–810. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hutchinson M.R., Zhang Y.N., Shridhar M., et al. Evidence that opioids may have toll-like receptor 4 and MD-2 effects. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zare N., Pourhadi M., Vaseghi G., Javanmard S.H. The potential interplay between opioid and the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2023;45:240–252. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2022.2122500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Giakomidi D., Bird M.F., Lambert D.G. Opioids and cancer survival: are we looking in the wrong place? BJA Open. 2022;2 doi: 10.1016/j.bjao.2022.100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Camarda V., Calo G. Chimeric G proteins in fluorimetric calcium assays: experience with opioid receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;937:293–306. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-086-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bird M.F., Hebbes C.P., Scott S.W.M., Willets J., Thompson J.P., Lambert D.G. A novel bioassay to detect Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ release from single human polymorphonuclear cells. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stein C., Schafer M., Machelska H. Attacking pain at its source: new perspectives on opioids. Nat Med. 2003;9:1003–1008. doi: 10.1038/nm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Thompson J.P., Serrano-Gomez A., McDonald J., Ladak N., Bowrey S., Lambert D.G. The Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ system is modulated in patients admitted to ICU with sepsis and after cardiopulmonary bypass. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Carvalho D., Petronilho F., Vuolo F., et al. The nociceptin/orphanin FQ-NOP receptor antagonist effects on an animal model of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:2284–2290. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bird M.F., Gallacher-Horley B., McDonald J., et al. In vitro sepsis induces Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ receptor (NOP) expression in primary human vascular endothelial but not smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Goff J., Hina M., Malik N., et al. Can opioid-free anaesthesia be personalised? A narrative review. J Pers Med. 2023;13:500. doi: 10.3390/jpm13030500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fiore J.F., Olleik G., El-Kefraoui C., et al. Preventing opioid prescription after major surgery: a scoping review of opioid-free analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:627–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Myles P.S., Bui T. Opioid-free analgesia after surgery. Lancet. 2022;399:2245–2247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yaksh T.L., Hunt M.A., dos Santos G.G. Development of new analgesics: an answer to opioid epidemic. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39:1000–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shanthanna H., Ladha K.S., Kehlet H., Joshi G.P. Perioperative opioid administration: a critical review of opioid-free versus opioid-sparing approaches. Anesthesiology. 2021;134:645–659. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Olausson A., Svensson C.J., Andrell P., Jildenstal P., Thorn S.E., Wolf A. Total opioid-free general anaesthesia can improve postoperative outcomes after surgery, without evidence of adverse effects on patient safety and pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2022;66:170–185. doi: 10.1111/aas.13994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fiore J.F., Jr., El-Kefraoui C., Chay M.A., et al. Opioid versus opioid-free analgesia after surgical discharge: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2022;399:2280–2293. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Knaul F.M., Farmer P.E., Krakauer E.L. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief – an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]