Abstract

Objective:

To establish the prognostic value of mean corpuscular volume (MCV) in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) who have undergone esophagectomy.

Background:

The MCV increases in patients with high alcohol and tobacco consumption. Such a lifestyle can be a risk factor for malnutrition, comorbidities related to those habits, and multiple primary malignancies, which may be associated with frequent postoperative morbidity and poor prognosis.

Methods:

This study included 1673 patients with ESCC who underwent curative esophagectomy at eight institutes between April 2005 and November 2020. Patients were divided into normal and high MCV groups according to the standard value of their pretreatment MCV. Clinical background, short-term outcomes, and prognosis were retrospectively compared between the groups.

Results:

Overall, 26.9% of patients had a high MCV, which was significantly associated with male sex, habitual smoking and drinking, multiple primary malignancies, and malnutrition, as estimated by the body mass index, hemoglobin and serum albumin values, and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index. Postoperative respiratory morbidity (P = 0.0075) frequently occurred in the high MCV group. A high MCV was an independent prognostic factor for worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.049–1.533; P = 0.014) and relapse-free survival (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.047–1.455; P = 0.012).

Conclusions:

A high MCV correlates with habitual drinking and smoking, malnutrition, and multiple primary malignancies and could be a surrogate marker of worse short-term and long-term outcomes in patients with ESCC who undergo esophagectomy.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, esophagectomy, mean corpuscular volume, prognosis

Mini-Abstract: This multicenter cohort study elucidated that a high pretreatment mean corpuscular volume correlated with habitual drinking and smoking, malnutrition, and multiple primary malignancies, and could be a surrogate marker of worse short-term and long-term outcomes in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who have undergone curative esophagectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the most common histological type of esophageal cancer worldwide. Notably, it frequently occurs in Eastern Asia, including Japan.1,2 Alcohol and tobacco consumption and male sex are the representative risk factors for the incidence of ESCC.2 Despite advances in recent multidisciplinary treatments, the prognosis of ESCC remains insufficient, and it is the sixth most common cause of cancer-related death in the world.1 In Japan, although the 5-year survival rate after surgery has improved to approximately 60%, that for patients in advanced stages remains low (cStage III, IVa, and IVb: 45%, 30%, and 17%, respectively).3 Thus, further advances in agents and treatment strategies are required.

Prognostic markers are useful for estimating the treatment outcomes and determining treatment strategies that may contribute to further improvement of the treatment outcomes. Especially, those prognostic markers that are based on laboratory data are clinically useful because they can be easily obtained without any physical or economic burden. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio,4 lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio,5 platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio,6 adapted systemic inflammation score,7 Glasgow prognostic score,8 and red blood cell distribution width9 have been previously suggested to be useful in estimating prognosis after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Moreover, several nutritional markers, such as the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score10 and prognostic nutritional index (PNI),11 are also useful.

The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is one such laboratory value commonly examined before esophagectomy. It indicates the average volume of red blood cells and is used to estimate the pathogenesis of anemia. The MCV increases with vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency, which is often observed in patients with habitual drinking.12 A high MCV also epidemiologically correlates with habitual smoking,13 which might be a predictor of ESCC incidence.14 A lifestyle of high alcohol and tobacco consumption can be a risk factor for malnutrition, comorbidities related to those habits, and multiple primary malignancies, which can be risk factors for postoperative morbidity and poor prognosis.10,15–17 Thus, we hypothesized that the MCV could be a prognostic marker in patients with ESCC who have undergone esophagectomy. We previously published the first report of a single-institute cohort study on the association of high MCV with poor prognosis after esophagectomy.18 Therefore, to validate and further establish the prognostic value of the MCV, we conducted a multicenter cohort study described herein.

METHODS

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in conformity to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The study procedures were performed after acquiring approval from the ethical committee of each participating institute with a waiver of written informed consent [registry numbers: 2191 (Kumamoto University), 210010 (Kagoshima University), 20151713 (Nagasaki University), 2021-109 (Kyushu University), 2066 (Oita University), 0-0919 (Miyazaki University), 2021-12 (Kyushu Cancer Center), and 2021-3-1 (Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital)].

Study Design and Patients

This multicenter cohort study included 1813 patients with ESCC who underwent curative esophagectomy at 8 hospitals in the Kyushu region of Japan between April 2005 and November 2020 (see Supplemental Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A122, which shows a study flow chart). Of these, 113 patients with insufficient data on patient characteristics, tumor characteristics, surgical background, and prognosis were excluded. Additionally, 27 patients with low MCV were excluded because this was a rather small sample size to analyze. Consequently, 1673 patients were included. Pretreatment MCV was examined in all the patients. The patients were categorized into two groups: normal (83–99 fL) and high (>99 fL) groups, according to the standard MCV value.19

Data Collection

Data were collected from the clinical database of each institution. Associations between the pretreatment MCV and clinical background, short-term outcome, and prognosis were retrospectively examined. Pretreatment clinical stage (cStage) was classified based on the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging version 8.20 cStage IVB was included in this study only when it was due to M1 lymph nodes (LNs), which corresponded to regional LNs in the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer (ie, supraclavicular LNs).21

Institutional Authorization

All 8 hospitals that participated were Authorized Institutes for Board-Certified Esophageal Surgeons (AIBCES) certified by the Japan Esophageal Society (JES). The provisions for certification are available elsewhere.22 The AIBCES need to meet eight criteria to be certified. Clinically, ≥100 treated patients and ≥50 surgeries for esophageal disease per 5 years and full-time employment are required of board-certified esophageal surgeons. A cohort study using 4897 patients with esophageal cancer registered in the Japan National Database of Hospital-based Cancer Registries, suggested that survival outcomes after esophagectomy at AIBCES were significantly better than those at non-AIBCES.23

Esophagectomy

Several types of esophagectomy were included in this study if each esophagectomy was curatively performed. Curative esophagectomy was defined as surgery with surgical R0 and R1 resections. R2 resection, which indicates residual macroscopically visible cancer during esophagectomy, was excluded.

Definition of Morbidity

Postoperative morbidity and severe morbidity were defined as a complication of the Clavien-Dindo classification (CDc) grade ≥II and ≥IIIb, respectively.24 Definitions of pneumonia, respiratory morbidity, cardiovascular morbidity, surgical site infection, and leakage are available elsewhere.25

Definition of Prognostic Outcome

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to death. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to recurrence and death.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was employed for statistical comparison between the unpaired samples. The chi-square test was employed for statistical comparison between the groups. Analysis for the survival time distribution and significant differences on OS and RFS was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test, respectively. Investigation for independent risk factors and the hazard ratio (HR) was performed using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Univariate analysis was performed to examine the effect of the following factors: age (for a 10-year increase); male sex [vs female sex]; body mass index (BMI) <18.5 (vs ≥18.5 kg/m2); Brinkman index [number of cigarettes per day × smoking duration (year), for an increase of 100]; performance status (PS) 0 (vs ≥1); the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status 1 and 2 (vs 3); cStage II, III, IVA, and IVB (vs I); number of dissection fields 0 and 1 (vs 2 and 3); operative time (for a 60-minute increase); bleeding (for a 100-g increase); severe morbidity (vs no); and MCV high (vs normal). Factors that showed a probability of P <0.10 were subjected to the final analysis. An independent risk factor was considered appropriate at a P value <0.05. Ultimately, modification of the effect of MCV on OS by other parameters was examined. The study period was included in the analysis to minimize historical bias regarding perioperative cancer treatment. The study period was divided into 3 phases: before the JCOG9907 study (2005−2011), the transitional period (2012−2013), and after generalization (2014−2020), because the standard treatment for locally advanced ESCC in Japan has been modified from surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus subsequent surgery since 2012 (JCOG9907).26 JMP version 13.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and StatView software package (version 5.0; Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA) were used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Patients’ Clinical Features

Of 1673 patients, 450 (26.9%) had a high pretreatment MCV (Table 1). A high MCV significantly correlated with younger age (P < 0.0001), male sex (P < 0.0001), habitual smoking (P < 0.0001), habitual drinking (P < 0.0001), as well as with frequent synchronous or metachronous multiple primary malignancies (P = 0.0015). Moreover, a high MCV was significantly associated with lower BMI (P < 0.0001), hemoglobin level (P < 0.0001), serum albumin value (P = 0.027), and Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) (P < 0.0001), suggesting that MCV could be a surrogate marker of malnutrition (Supplemental Table 2, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A122, shows the associations).

TABLE 1.

Pretreatment MCV and Patients’ Characteristics

| Clinical and Epidemiological Features | Total N | Pretreatment MCV | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | High | |||

| All cases | 1673 | 1223 | 450 | |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 65.9 ± 8.5 | 66.4 ± 8.6 | 64.3 ± 8.2 | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 1406 (84%) | 1002 (82%) | 404 (90%) | <0.0001 |

| Mean body mass index ± SD (kg/m2) | 21.6 ± 3.2 | 21.8 ± 3.2 | 20.9 ± 2.9 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <0.0001 | |||

| <18.5 | 275 (16%) | 176 (14%) | 99 (22%) | |

| 18.5–25.0 | 1181 (71%) | 863 (71%) | 318 (71%) | |

| >25.0 | 217 (13%) | 184 (15%) | 33 (7%) | |

| Brinkman index ± SD* | 740 ± 580 | 710 ± 580 | 820 ± 570 | 0.0005 |

| Habitual tobacco use, yes | 1377 (82%) | 976 (80%) | 401 (89%) | <0.0001 |

| Habitual alcohol use, yes† | 1446 (88%) | 1025 (85%) | 421 (95%) | <0.0001 |

| Performance status | 0.12 | |||

| 0 | 1452 (87%) | 1052 (86%) | 400 (89%) | |

| ≥1 | 221 (13%) | 171 (14%) | 50 (11%) | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status | 0.68 | |||

| 1 and 2 | 1585 (95%) | 1157 (95%) | 428 (95%) | |

| 3 | 88 (5%) | 66 (5%) | 22 (5%) | |

| Synchronous or metachronous multiple primary malignancy, yes | 490 (29%) | 332 (27%) | 158 (35%) | 0.0015 |

*The Brinkman index was calculated as follows: number of cigarettes per day × smoking duration (year).

†31 missing data existed.

Tumor and Treatment Characteristics

The tumor location was statistically different between the groups (P = 0.022). However, other characteristics, such as the cStage, preoperative treatment, surgical procedure, and number of LN dissection fields, were equivalent between the groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pretreatment MCV and Tumor and Treatment Characteristics

| Tumor and Surgical Characteristics | Total N | Pretreatment MCV | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | High | |||

| All cases | 1673 | 1223 | 450 | |

| Location of the tumor | 0.022 | |||

| Ce | 60 (4%) | 36 (3%) | 24 (5%) | |

| Ut | 234 (14%) | 173 (14%) | 61 (14%) | |

| Mt | 858 (51%) | 617 (50%) | 241 (54%) | |

| Lt | 475 (28%) | 357 (29%) | 118 (26%) | |

| Ae | 46 (3%) | 40 (3%) | 6 (1%) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.42 | |||

| I | 612 (37%) | 437 (36%) | 175 (39%) | |

| II | 349 (21%) | 250 (20%) | 99 (22%) | |

| III | 510 (30%) | 388 (32%) | 122 (27%) | |

| IVA | 117 (7%) | 84 (7%) | 33 (7%) | |

| IVB* | 85 (5%) | 64 (5%) | 21 (5%) | |

| Preoperative treatment, yes | 857 (51%) | 636 (52%) | 221 (49%) | 0.29 |

| Surgical procedure | 0.88 | |||

| Three-incision esophagectomy | 1534 (92%) | 1125 (92%) | 409 (91%) | |

| Ivor Lewis | 14 (1%) | 11 (1%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Transhiatal esophagectomy | 47 (3%) | 34 (3%) | 13 (3%) | |

| Pharyngolaryngoesophagectomy | 50 (3%) | 34 (3%) | 16 (4%) | |

| Mediastinoscopic esophagectomy | 23 (1%) | 15 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Others | 5 (0.3%) | 4 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Thoracic procedure | 0.99 | |||

| Minimally invasive† | 1219 (73%) | 891 (73%) | 328 (73%) | |

| Open | 454 (27%) | 332 (27%) | 122 (27%) | |

| Abdominal procedure | 0.60 | |||

| Laparoscopic | 778 (47%) | 564 (46%) | 214 (48%) | |

| Open | 895 (53%) | 659 (54%) | 236 (52%) | |

| No. dissection fields | 0.25 | |||

| 0 and 1 | 97 (6%) | 66 (5%) | 31 (7%) | |

| 2 and 3 | 1576 (94%) | 1157 (95%) | 419 (93%) | |

*cStage IVB included only cancers with clinical M1 lymph nodes according to the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging corresponding to regional lymph nodes in the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer.

†Minimally invasive procedures in the thorax included thoracoscopic, mediastinoscopic, and transhiatal surgeries.

Ae indicates abdominal esophagus; Ce, cervical esophagus; Lt, lower thoracic esophagus; Mt, middle thoracic esophagus; Ut, upper thoracic esophagus.

Short-Term Outcomes After Surgery

Table 3 presents short-term outcomes after surgery. The mean operative time was significantly longer in the high MCV group than in the normal MCV group, although the difference was only 15 minutes. Regarding postoperative morbidity, pneumonia (P = 0.029) and respiratory morbidity (P = 0.0075) frequently occurred in the high MCV group. Results of the logistic regression analysis indicated that a high MCV was an independent risk factor for postoperative respiratory morbidity [HR, 1.46; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.094–1.956; P = 0.010], along with an increased Brinkman index, and open procedure in the thorax (Supplemental Table 3, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A122, shows detailed results of the analysis).

TABLE 3.

Pretreatment MCV and Short-Term Outcomes of surgery

| Surgical Data and Morbidity | Total N | Pretreatment MCV | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | High | |||

| All cases | 1673 | 1223 | 450 | |

| Mean operative time ± SD (min) | 560 ± 130 | 550 ± 130 | 570 ± 130 | 0.03 |

| Mean bleeding ± SD (g) | 430 ± 490 | 430 ± 480 | 430 ± 500 | 0.85 |

| Postoperative morbidity (CDc ≥II) | 679 (41%) | 480 (39%) | 199 (44%) | 0.066 |

| Postoperative severe morbidity (CDc ≥IIIb) | 152 (9%) | 103 (8%) | 49 (11%) | 0.12 |

| Pneumonia | 235 (14%) | 158 (13%) | 77 (17%) | 0.029 |

| Pulmonary morbidity | 265 (16%) | 176 (14%) | 89 (20%) | 0.0075 |

| Cardiovascular morbidity | 66 (4%) | 49 (4%) | 17 (4%) | 0.83 |

| Surgical site infection | 430 (26%) | 303 (25%) | 127 (28%) | 0.15 |

| Leak | 294 (18%) | 209 (17%) | 85 (19%) | 0.39 |

Prognosis After Surgery

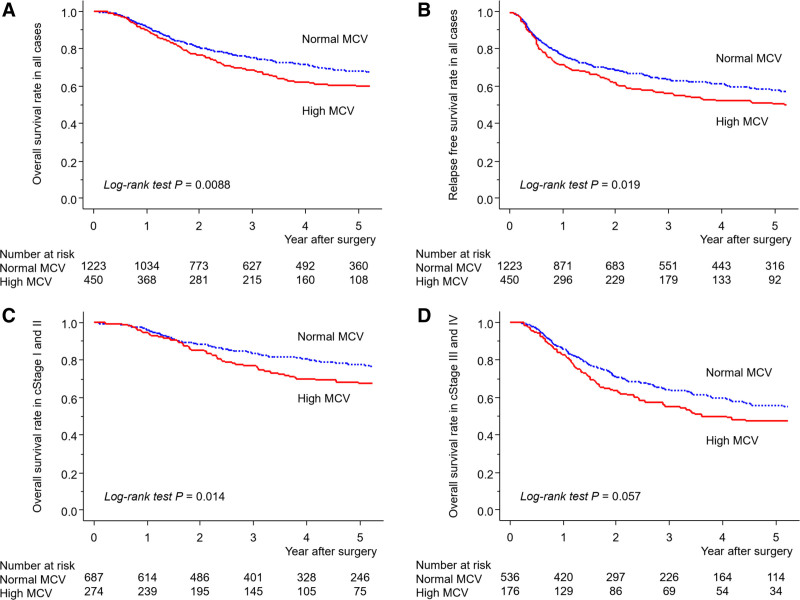

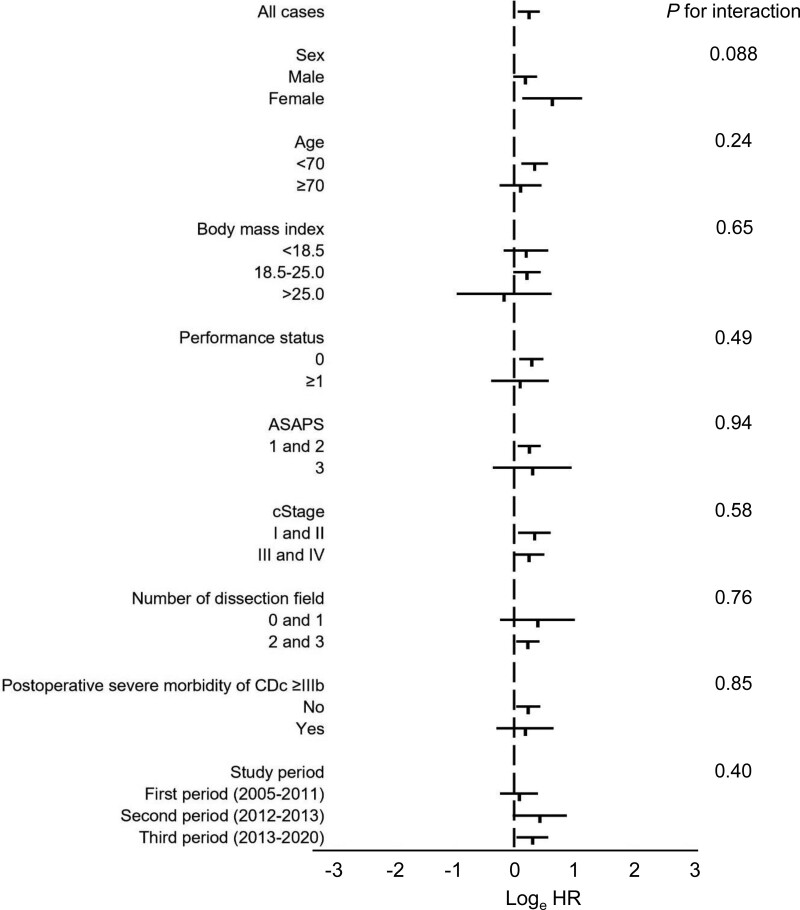

Figure 1 presents the Kaplan–Meier curves of OS and RFS between the groups. A high MCV was significantly associated with worse OS (P = 0.0088) and RFS (P = 0.019) in all the patients (Figs. 1A, B). Further analysis suggested that the OS in cStages I and II was significantly worse in the high MCV group than in the normal group (P = 0.014) (Fig. 1C). Moreover, a high MCV exhibited a trend toward a worse OS in cStages III and IV, although it was not statistically significant (P = 0.057) (Fig. 1D). Results of the Cox regression analysis suggested that a high MCV was an independent prognostic factor for worse OS (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.049–1.533; P = 0.014), along with advanced age, low BMI, worse American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status, advanced cStage, small number of dissection fields, higher blood loss, and severe postoperative morbidity of CDc ≥IIIb (Table 4), as well as for worse RFS (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.047–1.455; P = 0.012) (Supplemental Table 4, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A122, shows detailed results of the Cox regression analysis). Regarding the influence of MCV on OS, modification by other clinical parameters was not observed (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of os (A), RFS (B) in all patients, and overall survival in clinical stages I and II (C) and III and IV (D) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in accordance with the status of the pretreatment MCV.

TABLE 4.

Results of Cox Regression Analysis of OS

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (for a 10-year increase) | 1.14 (1.027–1.264) | 0.013 | 1.16 (1.037–1.291) | 0.0090 |

| Male sex (vs female sex) | 1.08 (0.849–1.373) | 0.53 | ||

| Body mass index <18.5 (vs ≥18.5) (kg/m2) | 1.81 (1.474–2.228) | <0.0001 | 1.41 (1.132–1.747) | 0.0020 |

| Brinkman index (for an increase of 100) | 1.002 (0.987–1.017) | 0.80 | ||

| Performance status 0 (vs ≥1) | 0.45 (0.252–0.791) | 0.0057 | 0.83 (0.643–1.062) | 0.14 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists physical statuses 1 and 2 (vs 3) | 0.46 (0.335–0.621) | <0.0001 | 0.58 (0.414–0.817) | 0.0018 |

| Clinical stage II (vs stage I) | 1.89 (1.461–2.449) | <0.0001 | 1.87 (1.436–2.425) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical stage III (vs stage I) | 2.50 (1.989–3.153) | <0.0001 | 2.44 (1.926–3.088) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical stage IVA (vs stage I) | 4.10 (3.024–5.559) | <0.0001 | 3.46 (2.524–4.736) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical stage IVB* (vs stage I) | 3.87 (2.708–5.533) | <0.0001 | 4.03 (2.807–5.797) | <0.0001 |

| No. dissection fields, 0 and 1 (vs 2 and 3) | 1.71 (1.247–2.348) | 0.0009 | 1.51 (1.087–2.087) | 0.014 |

| Operative time (for a 60-minute increase) | 1.04 (0.998–1.080) | 0.064 | 1.01 (0.968–1.052) | 0.67 |

| Bleeding (for a 100-g increase) | 1.03 (1.019–1.041) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.006–1.032) | 0.0040 |

| Severe morbidity of CDc ≥IIIb (vs no) | 1.87 (1.456–2.389) | <0.0001 | 1.73 (1.339–2.233) | <0.0001 |

| MCV high (vs normal) | 1.28 (1.063–1.538) | 0.0090 | 1.27 (1.049–1.533) | 0.014 |

*cStage IVB included only cancers with clinical M1 lymph nodes according to the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging corresponding to regional lymph nodes in the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer.

FIGURE 2.

Relationship between the MCV and OS in various strata: log (HRs) plots showing the 95% confidence interval for the overall survival rate related to a high mean corpuscular volume. ASAPS indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

DISCUSSION

Alcohol and tobacco use are 2 representative risk factors for the incidence of ESCC, and MCV epidemiologically reflects alcohol and tobacco consumption.12,13,18 The average MCVs in male and female patients in this study were 96.4 and 94.2 fL, respectively, which were considerably higher than those in the general healthy population in Japan (91.0 and 90.7 fL, respectively).19 Consequently, as many as 27% of the patients with ESCC had a high pretreatment MCV. High alcohol and tobacco consumption may have several adverse effects on surgical and survival outcomes, such as malnutrition, comorbidity related to those habits, and multiple primary malignancies.10,15,16 In the present multicenter cohort study, several interesting results were obtained that confirm our hypothesis: (1) high pretreatment MCV significantly correlated with habitual drinking and smoking, a high Brinkman index and male sex, which are risk factors for ESCC; (2) high MCV correlated with malnutrition, as estimated by the BMI, hemoglobin level, serum albumin value, and GNRI; (3) high MCV significantly correlated with synchronous or metachronous malignancies other than ESCC; (4) high MCV was a significant risk factor for postoperative pneumonia and respiratory morbidity; and (5) high MCV was an independent risk factor for poor OS and RFS.

In this study, we analyzed the MCV values before any treatment administration. The preoperative value was often used to investigate the postesophagectomy prognostic value of the hematologic parameters. However, preoperative treatments are commonly administered for locally advanced ESCC, which could affect the MCV value and complicate the elucidation of the background that may worsen prognosis in patients with a high MCV. Therefore, we used the pretreatment MCV to clarify the correlation between a high MCV and poor prognosis.

A high MCV was associated with habitual drinking and smoking. Previous studies have suggested that drinking and smoking could be risk factors for postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy.27,28 Impairment of liver and respiratory functions, respiratory comorbidity, and cardiovascular comorbidity related to alcohol and tobacco can increase postesophagectomy morbidities.15 In particular, smoking promotes proinflammatory cytokine release, chronic airway inflammation, and mucus hypersecretion,29 which could contribute to the increase in respiratory morbidity. Additionally, these disadvantageous backgrounds also increase deaths due to diseases other than esophageal cancer, which can also worsen survival outcomes.

A high MCV could be a surrogate marker of poor nutritional status, as inferred from BMI, hemoglobin and serum albumin values, and GNRI. Malnutrition delays tissue repair and reduces host immune function,30 which can increase postoperative morbidity. A decrease in activities of daily living (ADL) in patients with malnourishment and sarcopenia can delay postoperative recovery and increase respiratory morbidity after esophagectomy due to emaciation of breathing muscles and difficulty in sputum evacuation.31,32 The GNRI has been suggested to predict postoperative morbidity and prognosis after esophagectomy.33,34 Additionally, several studies have suggested that malnutrition assessed by the CONUT score and PNI may increase postoperative morbidities after esophagectomy.25,35 Studies on the association between malnutrition and postesophagectomy morbidity may explain a probable mechanism of increased morbidity in patients with a high MCV.

A high MCV correlated with frequent multiple primary malignancies other than ESCC, possibly due to habitual drinking and smoking.36 Multiple primary malignancies themselves can be a potent reason for increased death.16 Moreover, a history of surgery for metachronous malignancy can complicate esophagectomy due to adhesion. A previous history of gastrointestinal surgery may complicate the reconstruction. The presence of simultaneous malignancy can also complicate surgery because of concurrent resection. These factors can increase postoperative morbidity and further worsen the prognosis after esophagectomy.

Postoperative morbidities worsen prognosis after the surgical treatment of cancer. Notably, respiratory, infectious, and severe morbidities were suggested to deteriorate prognosis after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer.37–39 Persistent inflammation affects cytokine reactions and antitumor immunity, which can promote residual cancer cell growth.39 Prolonged recovery after esophagectomy can be a reason for the loss of the appropriate timing of adjuvant treatment. Deterioration of PS and ADL after severe morbidity can be a reason for avoiding invasive treatment for recurrence. Besides, a low PS and ADL can also be risk factors of death due to impaired physical condition, such as aspiration pneumonia and traumatic injury.18,40 Thus, the increased postoperative morbidity in patients with a high MCV may worsen the prognosis after esophagectomy.

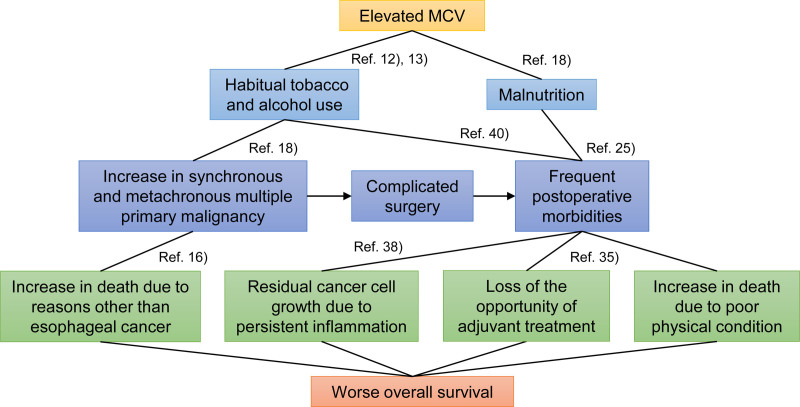

Based on the current results, a high pretreatment MCV reflects past drinking and smoking, malnutrition, and an increase in multiple primary cancers, which can increase postoperative morbidity and ultimately worsen prognosis (Fig. 3). Therefore, for ESCC patients with a high pretreatment MCV for whom esophagectomy is planned, clarification of the underlying risks and prophylaxes for postoperative morbidity are considerably important. Preoperative smoking cessation,41 nutritional support,42 respiratory rehabilitation,43 and oral hygiene44 may help improve surgical outcomes. Minimally invasive esophagectomy has been reported to have fewer postoperative morbidities irrespective of the type of preoperative treatment.15 Thus, performing minimally invasive surgery is one of the possible options.45 Preoperative prediction of postesophagectomy morbidities is also important in preventing and minimizing them. Objective predictors, such as exhaled carbon monoxide,46 left-sided esophagus on computed tomography (CT),47 and asymptomatic sputum in the respiratory tract on CT32 may be useful in predicting morbidity.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of the association of an elevated MCV with poor prognosis.

This is the largest cohort study to explore the correlation between hematologic parameters and prognosis after esophagectomy for ESCC. All facilities participating in this study were AIBCESs certified by the JES. Hence, sufficient quality of treatment strategy, surgery, and perioperative management were maintained among the institutions. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. Because of the retrospective, multicenter nature of the studies, there might have been inter-institutional biases regarding the accuracy of preoperative clinical staging, esophagectomy volume, surgical procedure, perioperative management, follow-up schedules, and surgical outcomes, in addition to historical bias regarding perioperative treatment. To minimize historical bias regarding perioperative cancer treatment in JCOG9907, we confirmed that the effect of MCV on OS did not differ among the three study periods. Additionally, several factors that could affect the MCV value, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiency, history of gastrectomy and hypothyroidism, among others, could not be fully screened. Last, the objective area was limited to Japan. Thus, further studies using cohorts in other regions are necessary to establish the universal prognostic value of the MCV in patients with ESCC.

In conclusion, we believe that a high pretreatment MCV correlates with habitual drinking and smoking, malnutrition, and multiple primary malignancies, and could be a surrogate marker of worse short-term and survival outcomes in patients with ESCC who underwent esophagectomy. For patients with a high MCV, it is important to identify the underlying risks and take measures to reduce postoperative morbidity, which may contribute to improving prognosis after esophagectomy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 2 May 2022

Disclosure: N.Y. has course affiliations with Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Yakuruto Honsya Co., Ltd. The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K09076).

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.annalsofsurgery.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Tarazi M, Chidambaram S, Markar SR. Risk factors of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma beyond alcohol and smoking. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam AK. Introduction: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-current status and future advances. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2129:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe M, Tachimori Y, Oyama T, et al.; Registration Committee for Esophageal Cancer of the Japan Esophageal Society. Comprehensive registry of esophageal cancer in Japan, 2013. Esophagus. 2021;18:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosumi K, Baba Y, Ishimoto T, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts the prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Surg Today. 2016;46:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Q, Wu JZ, Wang S. Low preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio serves as a worse prognostic marker in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing curative tumor resection. J Cancer. 2019;10:2057–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie X, Luo KJ, Hu Y, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative platelet-lymphocyte and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients undergoing surgery for esophageal squamous cell cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomoto D, Baba Y, Akiyama T, et al. Adapted systemic inflammation score as a novel prognostic marker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2021;5:669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Chen L, Wu Y, et al. The prognostic value of modified Glasgow prognostic score in patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72:1146–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida N, Horinouchi T, Eto K, et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment red blood cell distribution width in patients with esophageal cancer who underwent esophagectomy: a retrospective study. Ann Surg Open. 2022;2:e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida N, Harada K, Baba Y, et al. Preoperative controlling nutritional status (CONUT) is useful to estimate the prognosis after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2017;402:333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okadome K, Baba Y, Yagi T, et al. Prognostic nutritional index, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2020;271:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingall GB. Alcohol biomarkers. Clin Lab Med. 2012;32:391–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malenica M, Prnjavorac B, Bego T, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on haematological parameters in healthy population. Med Arch. 2017;71:132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama A, Yokoyama T, Kumagai Y, et al. Mean corpuscular volume, alcohol flushing, and the predicted risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in cancer-free Japanese men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1877–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida N, Yamamoto H, Baba H, et al. Can Minimally invasive esophagectomy replace open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer? Latest analysis of 24,233 esophagectomies from the Japanese National Clinical Database. Ann Surg. 2020;272:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baba Y, Yoshida N, Kinoshita K, et al. Clinical and prognostic features of patients with esophageal cancer and multiple primary cancers: a retrospective single-institution study. Ann Surg. 2018;267:478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng YZ, Dai SQ, Li W, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative mean corpuscular volume in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2811–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida N, Kosumi K, Tokunaga R, et al. clinical importance of mean corpuscular volume as a prognostic marker after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a retrospective study. Ann Surg. 2020;271:494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takami A, Watanabe S, Yamamoto Y, et al.; Japanese Society for Laboratory Hematology Standardization Committee (JSLH-SC) and Joint Working Group of the JSLH and the Japanese Association of Medical Technologists (JWG-JSLH-JAMT). Reference intervals of red blood cell parameters and platelet count for healthy adults in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2021;114:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, et al. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: an eighth edition staging primer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese classification of esophageal cancer. 11th ed.: part I. Japan Esophageal Society. Esophagus. 2017;14:1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motoyama S, Maeda E, Yano M, et al. Esophagectomy performed at institutes certified by the Japan Esophageal Society provide long-term survival advantages to esophageal cancer patients: second report analyzing 4897 cases with propensity score matching. Esophagus. 2020;17:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motoyama S, Maeda E, Yano M, et al.; Japan Esophageal Society. Appropriateness of the institute certification system for esophageal surgeries by the Japan Esophageal Society: evaluation of survival outcomes using data from the National Database of Hospital-Based Cancer Registries in Japan. Esophagus. 2019;16:114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida N, Baba Y, Shigaki H, et al. Preoperative Nutritional Assessment by Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) is useful to estimate postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2016;40:1910–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando N, Kato H, Igaki H, et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907). Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molena D, Mungo B, Stem M, et al. Incidence and risk factors for respiratory complications in patients undergoing esophagectomy for malignancy: a NSQIP analysis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;26:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Baba Y, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary complications after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2014;44:526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang T, Luo F, Shen Y, et al. Quercetin attenuates airway inflammation and mucus production induced by cigarette smoke in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;13:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerriets VA, MacIver NJ. Role of T cells in malnutrition and obesity. Front Immunol. 2014;5:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papaconstantinou D, Vretakakou K, Paspala A, et al. The impact of preoperative sarcopenia on postoperative complications following esophagectomy for esophageal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2020:doaa002. doi: 10.1093/dote/doaa002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshida N, Morito A, Nagai Y, et al. Clinical importance of sputum in the respiratory tract as a predictive marker of postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:2580–2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamana I, Takeno S, Shibata R, et al. Is the geriatric nutritional risk index a significant predictor of postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy? Eur Surg Res. 2015;55:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamana I, Takeno S, Shimaoka H, et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index as a prognostic factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma -retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2018;56:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filip B, Scarpa M, Cavallin F, et al. Postoperative outcome after oesophagectomy for cancer: Nutritional status is the missing ring in the current prognostic scores. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baba Y, Yoshida N, Shigaki H, et al. prognostic impact of postoperative complications in 502 patients with surgically resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective single-institution study. Ann Surg. 2016;264:305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tam V, Luketich JD, Winger DG, et al. Cancer recurrence after esophagectomy: impact of postoperative infection in propensity-matched cohorts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:1638–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bundred JR, Hollis AC, Evans R, et al. Impact of postoperative complications on survival after oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer. BJS Open. 2020;4:405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsujimoto H, Kobayashi M, Sugasawa H, et al. Potential mechanisms of tumor progression associated with postoperative infectious complications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021;40:285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida N, Eto K, Kurashige J, et al. Comprehensive analysis of multiple primary cancers in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida N, Baba Y, Hiyoshi Y, et al. Duration of smoking cessation and postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: how long should patients stop smoking before surgery? World J Surg. 2016;40:142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazaki T, Ishii Y, Murai I. Immunoenhancing enteral and parenteral nutrition for gastrointestinal surgery: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2015;261:662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamana I, Takeno S, Hashimoto T, et al. Randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of a preoperative respiratory rehabilitation program to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Dig Surg. 2015;32:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akutsu Y, Matsubara H, Shuto K, et al. Pre-operative dental brushing can reduce the risk of postoperative pneumonia in esophageal cancer patients. Surgery. 2010;147:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida N, Horinouchi T, Toihata T, et al. Clinical significance of pretreatment red blood cell distribution width as a predictive marker for postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a retrospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida N, Baba Y, Kuroda D, et al. Clinical utility of exhaled carbon monoxide in assessing preoperative smoking status and risks of postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31:doy024. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida N, Baba Y, Shigaki H, et al. Effect of esophagus position on surgical difficulty and postoperative morbidities after thoracoscopic esophagectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;28:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.