Abstract

The Oral HIV/AIDS Research Alliance (OHARA) is part of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the largest HIV clinical trials organization in the world. Its main objective is to investigate oral complications associated with HIV/AIDS as the epidemic is evolving, in particular the effects of antiretrovirals on oral mucosal lesion development and associated fungal and viral pathogens. The OHARA infrastructure comprises: the Epidemiologic Research Unit (at the University of California San Francisco), the Medical Mycology Unit (at Case Western Reserve University), and the Virology/Specimen Banking Unit (at the University of North Carolina). The team includes dentists, physicians, virologists, mycologists, immunologists, epidemiologists and statisticians. Observational studies and clinical trials are being implemented at ACTG-affiliated sites in the US and resource-poor countries. Many studies have shared end-points, which include oral diseases known to be associated with HIV/AIDS measured by trained and calibrated ACTG study nurses. In preparation for future protocols, we have updated existing diagnostic criteria of the oral manifestations of HIV published in 1992 and 1993. The proposed case definitions are designed to be used in large-scale epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, in both US and resource-poor settings, where diagnoses may be made by non-dental healthcare providers. The objective of this article is to present updated case definitions for HIV-related oral diseases that will be used to measure standardized clinical end-points in OHARA studies, and that can be used by any investigator outside of OHARA/ACTG conducting clinical research that pertains to these end-points.

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, much has been learned about HIV-related oral mucosal diseases. The oral cavity has been found to play an important role in monitoring the progression of HIV disease as the occurrence of specific lesions, mainly oral candidiasis and hairy leukoplakia, is strongly associated with a low CD4 cell count 1–7 and a higher plasma viral load 6, 8. Furthermore, even though the prevalence of specific oral lesions like candidiasis, hairy leukoplakia, and Kaposi’s sarcoma has been found to be lower among patients on combination antiretroviral therapy 9–18, other conditions such as oral warts19–21 and salivary gland disease19 have been found to be more prevalent in this population. This suggests that some oral conditions may occur as part of the immune reconstitution that results from antiretroviral therapy initiation, and should be further explored.

The Oral HIV/AIDS Research Alliance (OHARA) is part of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the largest HIV clinical trials organization in the world. The ACTG plays a major role in defining the standards of care for treatment of HIV infection and opportunistic diseases related to HIV/AIDS 22. OHARA was created in 2006 in response to a request for applications from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. One of its main objectives is to investigate the oral complications associated with HIV/AIDS as the epidemic is evolving, in particular to explore the effects of potent antiretrovirals on the development of oral mucosal lesions, and associated fungal and viral pathogens. Another goal is to develop a comprehensive oral infection and mucosal disease database with HIV virologic and mycologic correlates and an HIV/AIDS oral specimen bank that will provide valuable material for future epidemiologic and biological research questions.

The OHARA infrastructure comprises: the Epidemiologic Research Unit (at the University of California San Francisco), the Medical Mycology Unit (at Case Western Reserve University), and the Virology Specimen Banking Unit (at the University of North Carolina). The team includes dentists specialized in oral medicine, physicians, virologists, mycologists, immunologists, epidemiologists and statisticians. Shared use of key support services and of existing research infrastructures is the hallmark of OHARA. Observational studies and clinical trials are being implemented at ACTG-affiliated clinical research sites in the US and in resource-poor countries. Many of these studies have shared end-points, which include oral mucosal diseases known to be associated with HIV/AIDS. At present, oral diseases, such as candidiasis, hairy leukoplakia, and at times necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, captured within some ACTG studies, are measured by non-dental clinicians (nurses, nurse practitioners, or physicians) who have not received a standardized training in the diagnosis of these lesions. Even though the diagnosis of pseudomembranous candidiasis, routinely referred to as “thrush”, is very familiar to HIV clinicians, the diagnosis of erythematous candidiasis is more subtle, and may be missed in the absence of a specialized training. Therefore, to standardize the measurement of oral mucosal outcomes associated with HIV/AIDS within the ACTG infrastructure the OHARA Clinical Focus Group has developed an extensive training module. A validation study of HIV-related oral mucosal disease diagnoses made by ACTG clinicians trained with this module as compared to oral medicine trained dentists is currently being implemented. As part of this study, and in preparation for future protocols, we have updated existing diagnostic criteria of the oral manifestations of HIV published in 1992 23 and 1993 (often referred to as EC-Clearinghouse or ECC criteria) 24 that have been used in most studies of HIV oral diseases in the past decade 3–9, 11, 13, 25–33. The proposed case definitions are designed to be used in large-scale epidemiologic studies and clinical trials, in both US and resource-poor settings, where diagnoses may be made by non-dental healthcare providers. The objective of this article is to present updated case definitions for HIV-related oral diseases that will be used to measure standardized clinical end-points in OHARA studies, and that can be used by any investigator outside of OHARA/ACTG conducting clinical research that pertains to these end-points.

REVISION OF THE 1992 AND 1993 (ECC) CRITERIA

In the present document, case definitions are organized by etiology: fungal, viral, and bacterial infections, idiopathic conditions, salivary gland disease, and neoplasms. We have found that when presenting our teaching modules to both oral and non-oral health care providers the organization by etiology is well-received and easy to understand and remember. Furthermore, in addition to the clinical descriptors that are observed by the clinician examiner while performing a standardized oral mucosa examination, we have added descriptors of patient-reported symptoms and duration of the condition if known. The purpose of adding symptom and duration descriptors to clinical descriptors is to improve diagnostic accuracy.

In addition to the inclusion of patient-reported symptoms to the clinical descriptors of the 1992 and 1993 case definitions, we have also made the following modifications and additions:

We have combined the 1993 definition of “Ulceration NOS (not otherwise specified)”, and “Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis” into one category as it may be difficult for non-dental examiners to determine if bone is exposed or not. However, we recognize that dental examiners may wish to make the distinction between necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis related to the periodontium and ulceration NOS elsewhere on the mucosa. Therefore, the 1993 definition of necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis is provided within the combined category, and can be extracted if desired.

We have combined necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, because visual examination without radiographs and without periodontal probing measurements would not permit accurate differentiation between these conditions.

A case definition for oral squamous cell carcinoma has been added. We recognize that oral squamous cell carcinoma has not yet been shown to be associated with HIV/AIDS. However, in the era of highly potent antiretroviral therapy, patients with HIV disease live longer, may use tobacco and/or alcohol, and therefore may be at risk of developing this condition. Furthermore, several recent reports in both the US and Europe have revealed an increased risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma among HIV-infected populations compared to the general population.34–36

In the category of “Salivary Gland Disease” salivary gland enlargement and salivary hypofunction are considered as two separate conditions since they may occur separately.

We also provide an algorithm for HIV-related oral lesion case definitions that summarizes clinical descriptors, symptoms, and duration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case definition algorithm summarizing clinical descriptors, symptoms, and duration for common HIV-related oral mucosal lesions

| Etiology | Oral Lesion / Condition | Color | Character | Extent | Location | Symptoms | Duration | Biopsy Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal Infections |

Pseudomembranous

Candidiasis |

White Yellow Creamy |

Plaques (usually removable) |

Localized or Generalized |

Anywhere | None to mild | Intermittent | No |

|

Erythematous

Candidiasis |

Red | Flat Patchy |

Localized or Generalized | Palate Dorsum of tongue Buccal mucosa |

None to mild | Intermittent | No | |

| Angular Cheilitis | Red White |

Fissured Ulcerated |

Unilateral or Bilateral |

Lip commissures | None to mild | Intermittent | No | |

| Viral Infections | Hairy leukoplakia | White |

Corrugated | Unilateral or Bilateral | Lateral tongue |

None | Longstanding | No |

| Oral wart | White Mucosal |

Raised Smooth Spiky Cauliflower-like |

Solitary or Multiple Clustered |

Anywhere | None | Longstanding | Yes | |

|

Recurrent Herpes

Labialis |

Red Mucosal |

Vesicular (vesicles) Ulcerated |

Solitary or Clustered |

Vermillion border (lip) | Mild to moderate | Intermittent 7–10 days/episode |

No | |

| Recurrent Intraoral Herpes Simplex | Red Mucosal |

Vesicular (vesicles) Ulcerated |

Clustered | Gingiva Hard palate |

Mild to moderate | Intermittent 7–10 days/episode |

No | |

| Idiopathic Conditions |

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

|

White Yellow |

Ulcerated | Solitary or Multiple |

Labial mucosa Buccal mucosa Ventral tongue Floor of mouth Soft palate |

Moderate to severe | Intermittent Minor: 7–10 days Major: weeks History of recurrence |

No |

| Ulceration NOS / Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis | White Yellow |

Ulcerated Necrotic |

Solitary (> 1 ulcer may be present) |

Anywhere | Severe | Longstanding | Yes | |

| Bacterial Infections | Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis or periodontitis | Red White Yellow |

Necrotic Fetid odor |

Localized or generalized | Gingiva and underlying bone | Severe | Sudden onset | No |

| Neoplasms | Oral Kaposi sarcoma | Red Purple |

Flat / macular Raised Nodular Ulcerated |

Solitary | Anywhere Predilection for palate and gingiva |

None to moderate | Longstanding | Yes |

| Oral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Red White |

Raised Ulcerated Indurated |

Solitary | Anywhere Predilection for fauces, palate, gingiva |

None to moderate | Longstanding | Yes | |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | Red White |

Raised Ulcerated Indurated |

Solitary | Anywhere Predilection for tongue |

None to severe | Longstanding | Yes |

CASE DEFINITIONS

1. Fungal infections

Pseudomembranous candidiasis

Clinical descriptors:

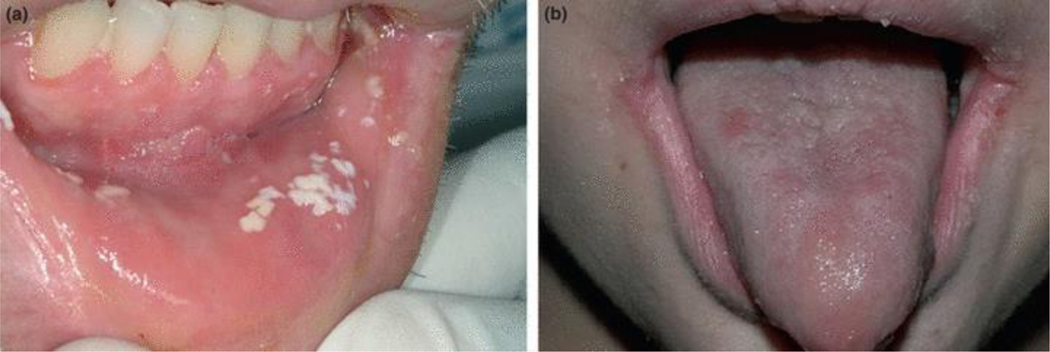

White or yellow/creamy spots or plaques that may be located in any part of the oral cavity and can usually be wiped off to reveal an erythematous surface (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Fungal infections: (a) Pseudomembranous candidiasis on the lower labial mucosa; (b) erythematous candidiasis on the dorsum of the tongue and angular cheilitis at the corners of the mouth.

Patient-reported symptoms:

None, or possible mild to moderate burning pain.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesions/symptoms usually intermittent, but may be long-standing.

Erythematous candidiasis

Clinical descriptors:

Patchy erythema or red areas usually located on the palate and dorsum of the tongue, but occasionally on the buccal mucosa. At times, white spots or plaques of pseudomembranous candidiasis may also be present (Figure 1b).

Patient-reported symptoms:

None, or possible mild to moderate burning pain.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesions/symptoms usually intermittent, but may be long-standing.

Angular cheilitis

Clinical descriptors:

Red or white fissures or linear ulcers located at the lip commissures or corners of the mouth (Figure 1b).

Patient-reported symptoms:

None, or possible mild pain when opening mouth.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesions/symptoms usually intermittent, but may be long-standing.

2. Viral infections

Hairy leukoplakia

Clinical descriptors:

Whitish/grey lesions on the lateral margins of the tongue. They are not removable and may exhibit vertical corrugations. Lesions range in size as they may be less than one centimeter, or may extend onto the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue where they are usually flat. May be bilateral or unilateral (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Viral infections: (a) Hairy leukoplakia on the right lateral border of tongue; (b) herpes labialis (arrows show ulcers that have coalesced at a later stage of recurrent herpes infection); (c) recurrent intraoral herpes simplex on left hard palate; (d) multiple warts seen on upper labial mucosa.

Patient-reported symptoms:

Asymptomatic.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesion(s) usually long-standing.

Recurrent Herpes labialis

Clinical descriptors:

Single or multiple vesicles or ulcers with crusting on vermillion portion of lips and adjacent facial skin (Figure 2b).

Patient-reported symptoms:

Usually mild to moderate pain.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesion(s) usually present for at most 10–14 days. Prior history of (or recurrent) lesion(s).

Recurrent Intra-oral herpes simplex

Clinical descriptors:

Solitary, or cluster of multiple or confluent ulcers that may be noted together with vesicles on keratinized mucosa, including hard palate, attached gingiva, and dorsum of tongue. Exceptionally, non-keratinized tissue may be involved. Round to slightly irregular (map-like) margins with minimal to no erythematous halos are present. The base of the ulcers is usually pink (Figure 2c).

Patient-reported symptoms:

Usually mild to moderate pain.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesion(s) usually present for at most 10–14 days. Prior history of (or recurrent) lesion(s).

Oral warts

Clinical descriptors:

Mucosal color or white, solitary or multiple (often clustered) raised lesions that range in texture as they may be smooth, spiky, or cauliflower-like, and located in any part of the oral cavity (Figure 2d).

Patient-reported symptoms:

Usually asymptomatic. Note: Warts on the buccal or labial mucosa or tongue along the lines of occlusion may become traumatized by biting, and thus may be painful.

Patient-reported duration:

Lesion(s) usually long-standing.

Definitive diagnosis (required)

Biopsy and routine histopathologic analysis to differentiate wart from papilloma not otherwise specified

3. Idiopathic conditions

Recurrent Aphthous stomatitis

Clinical descriptors:

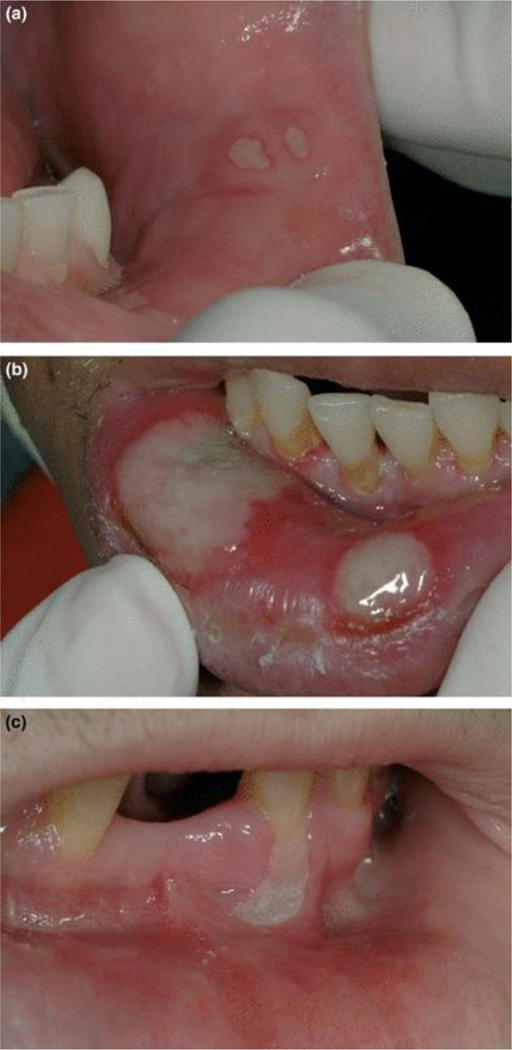

Single or multiple, white/yellow well circumscribed ulcer(s) on non-keratinized tissue. A red hallo is usually present around each ulcer. Minor aphthous ulcers may be 0.2 to 0.5 cm in diameter (Figure 3a), while major aphthous ulcers are > 0.5 cm (may be as large as 2 cm in diameter; Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Idiopathic conditions: (a) Minor aphthous ulcer on lower labial mucosa (note red hallo); (b) major aphthous ulcers on lower labial mucosa (note red hallo); for both minor and major aphthous ulcers, patient reports longterm history recurrence; (c) ulceration not otherwise specified (NOS); patient reports no history of recurrence.

Patient-reported symptoms:

Moderate to severe pain, especially upon eating.

Patient-reported duration:

Each minor ulcer usually lasts 7–10 days, while major aphthous ulcers may last for weeks. Patient reports a long-term history of recurrent ulcers.

Ulcerations NOS (not otherwise specified) / Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis

Clinical descriptors:

Large (> 0.5 cm and sometimes up to 3 cm) ulceration(s) with white/yellow necrotic base that may be located on either keratinized or non-keratinized mucosa (Figure 3c; Note: clinical appearance may be similar to that of major aphthous ulcer, but there is no history of recurrent lesions). Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis presents as localized, painful ulceronecrotic lesions of the oral mucosa that exposes underlying bone or penetrates or extends into contiguous tissues. These lesions may extend from areas of necrotizing periodontitis.

Patient-reported symptoms:

Severe pain may be a prominent feature.

Patient-reported duration:

Sudden onset, but may be long-standing.

Definitive diagnosis (required)

Histologic features are those of non-specific ulceration. Microbiologic studies fail to identify a specific etiologic agent.

4. Bacterial infections

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis or periodontitis

Clinical descriptors:

Destruction of one or more interdental gingival papillae. In the acute stage of the process ulceration, necrosis, and sloughing may be seen with ready hemorrhage and characteristic fetid odor. In the case of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, the condition is characterized by soft tissue loss as a result of ulceration or necrosis with exposure, destruction or sequestration of alveolar bone. The teeth may become loosened (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bacterial infections: Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis in the lower anterior segment.

Patient-reported symptoms:

Moderate to severe pain may be a prominent feature.

Patient-reported duration:

Usually sudden onset and rapidly worsening.

5. Salivary gland disease

Parotid enlargement

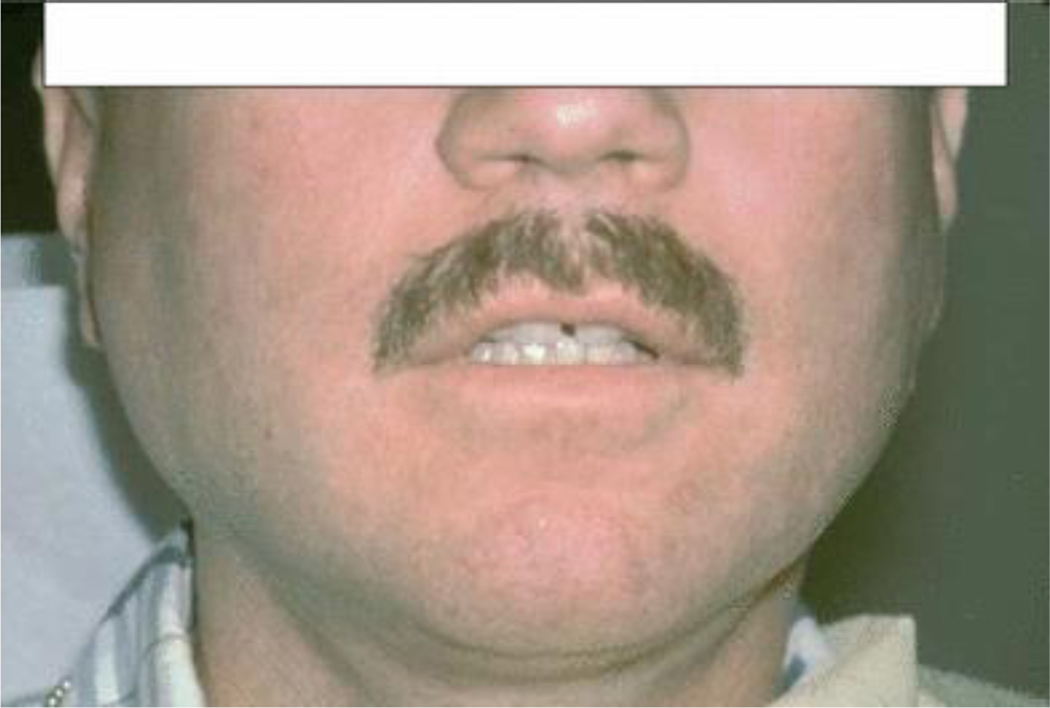

Clinical descriptors:

Enlargement of the parotid glands, usually bilateral (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Salivary gland disease: Bilateral parotid enlargement.

Patient-reported symptoms:

Usually asymptomatic enlargement. Patient may report xerostomia (perception of dry mouth).

Patient-reported duration:

Usually long-standing.

Salivary hypofunction

Defined as unstimulated whole salivary flow rate < 0.1 mL/min.37–39

6. Neoplasms

Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma

Clinical descriptors:

Early lesions are typically flat (or macular) with color ranging from red to purple. At a later stage lesions become nodular, raised and/or ulcerated. Predominantly present on the palate and gingiva (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 6.

Neoplasms: (a) Early stage Kaposi’s sarcoma on upper left gingiva; (b) advanced stage Kaposi’s sarcoma on upper right hard palate; (c) non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma on right soft palate; (d) squamous cell carcinoma on right lateral posterior tongue.

Patient-reported symptoms:

At early stage, lesions are asymptomatic. Mild to moderate pain may develop as lesions become nodular and ulcerated. Local trauma to more advanced lesions may induce bleeding.

Patient-reported duration:

Nodular lesions are long-standing.

Definitive diagnosis (required)

Characteristic histological appearance on biopsy.

Oral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Clinical descriptors:

A firm elastic, often somewhat reddish swelling, with or without ulceration. The gingiva, palatal mucosa, and fauces are sites of predilection (Figure 6c).

Patient-reported symptoms:

At early stage, lesions are usually asymptomatic. Moderate to severe pain may develop as lesions become ulcerated.

Patient-reported duration:

Ulcerated lesions and swellings are long-standing.

Definitive diagnosis (required)

Characteristic histological appearance on biopsy, supported by appropriate immunocytochemical or molecular biological investigations.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Presumptive criteria

Clinical descriptors:

Non-healing ulcer with rolled borders or margins. An advanced stage ulcer may be indurated or located on a firm mass (Figure 6d).

Patient-reported symptoms:

At early stage, lesions are usually asymptomatic. Moderate to severe pain may develop as lesions enlarge and become ulcerated.

Patient-reported duration:

Ulcerated lesions and swellings are long-standing.

Definitive diagnosis (required)

Characteristic histological appearance on biopsy.

CONCLUSION

Epidemiologic studies of disease outcomes rely on case definitions that can easily be measured with a clinical examination when a diagnostic test is not feasible. Such case definitions need to be both accurate (i.e., they measure what is intended to be measured) and precise (i.e., reproducible). We have expanded upon previously established diagnostic criteria for HIV-related oral diseases by adding patient-reported symptoms and duration to existing sets of clinical descriptors for each lesion. We anticipate that these updated case definitions will become the new standardized tool for the diagnosis of HIV-related oral lesions in epidemiologic studies, by both dental and non-dental clinician examiners. Since our intent is to standardize these definitions across studies our training module is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: NIH/NIDCR/NIAID U01 AI 68636

References

- 1.Feigal DW, Katz MH, Greenspan D, et al. The prevalence of oral lesions in HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men: three San Francisco epidemiological cohorts. AIDS 1991;5:519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz MH, Greenspan D, Westenhouse J, et al. Progression to AIDS in HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men with hairy leukoplakia and oral candidiasis. AIDS 1992;6:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, Salkin LM. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as markers for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;77:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiboski CH, Hilton JF, Greenspan D, et al. HIV-related oral manifestations in two cohorts of women in San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1994;7:964–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiboski CH, Hilton JF, Neuhaus JM, Canchola A, Greenspan D. Human immunodeficiency virus-related oral manifestations and gender. A longitudinal analysis. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patton LL, McKaig RG, Eron JJ Jr, Lawrence HP, Strauss RP. Oral hairy leukoplakia and oral candidiasis as predictors of HIV viral load. AIDS 1999;13:2174–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiboski CH, Wilson CM, Greenspan D, Hilton JF, Greenspan JS, Moscicki AB. HIV-related oral manifestations among adolescents in a multicenter cohort study. J Adolesc Health 2001;29:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenspan D, Komaroff E, Redford M, et al. Oral mucosal lesions and HIV viral load in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;25:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramirez-Amador V, Esquivel-Pedraza L, Sierra-Madero J, Anaya-Saavedra G, Gonzalez-Ramirez I, Ponce-de-Leon S. The changing clinical spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related oral lesions in 1,000 consecutive patients: A 12-year study in a referral center in Mexico. Med (Baltimore). 2003;82:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arribas J, Hernandez-Albujar S, Gonzalez-Garcia J, et al. Impact of Protease Inhibitor Therapy on HIV-related Oropharyngeal Candidiasis. AIDS 2000;14:979–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenspan D, Gange S, Phelan J, et al. Incidence of oral lesions in HIV-1-infected women: reduction with HAART. J Dent Res 2004;83:145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolatou-Galitis O, Velegraki A, Paikos S, et al. Effect of PI-HAART on the prevalence of oral lesions in HIV-1 infected patients. A Greek study. Oral Dis. 2004;10:145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton LL, McKaig RG, Strauss RP, Rogers D, Eron JJ Jr. Changing prevalence of oral manifestations of human immuno-deficiency virus in the era of protease inhibitor therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Westhausen A, Priepke F, Bergmann F, Reichart P. Decline in the rate of oral opportunistic infections following introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Oral Pathol Med 2000;29:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceballos-Salobrena A, Gaitan-Cepeda L, Ceballos-Garcia L, Lezama-Del Valle D. Oral lesions in HIV/AIDS patients undergoing highly active antiretroviral treatment including protease inhibitors: A new face of oral AIDS? AIDS Patient Care STDs 2000;14:627–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodgson TA, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Oral lesions of HIV disease and HAART in industrialized countries. Adv Dent Res 2006;19:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tappuni AR, Fleming GJ. The effect of antiretroviral therapy on the prevalence of oral manifestations in HIV-infected patients: a UK study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;92:623–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umadevi KM, Ranganathan K, Pavithra S, et al. Oral lesions among persons with HIV disease with and without highly active antiretroviral therapy in southern India. J Oral Pathol Med 2007;36:136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenspan D, Canchola A, MacPhail L, Cheike B, Greenspan J. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on frequency of oral warts. Lancet 2001;357:1411–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron JE, Mercante D, O’Brien M, et al. The impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy and immunodeficiency on human papillomavirus infection of the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive adults. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King MD, Reznik DA, O’Daniels CM, Larsen NM, Osterholt D, Blumberg HM. Human papillomavirus-associated oral warts among human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: an emerging infection. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.http://www.aactg.org/. Accessed February 28, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenspan JS, Barr CE, Sciubba JJ, Winkler JR. Oral manifestations of HIV infection. Definitions, diagnostic criteria, and principles of therapy. The U.S.A. Oral AIDS Collaborative Group. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992;73:142–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EC-Clearinghouse. Classification and diagnostic criteria for oral lesions in HIV infection. EC-Clearinghouse on Oral Problems Related to HIV Infection and WHO Collaborating Centre on Oral Manifestations of the Immunodeficiency Virus. J Oral Pathol Med 1993;22:289–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arendorf T, Bredekamp B, Cloete C, Sauer G. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in 600 South African patients. J Oral Pathol Med 1998;27:176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chidzonga M.HIV/AIDS orofacial lesions in 156 Zimbabwean patients at referral oral and maxillofacial surgical clinics. Oral Dis 2003;9:317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hilton J, Donegan E, Katz M, et al. Development of oral lesions in human immunodeficiency virus-infected transfusion recipients and hemophiliacs. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgson T.HIV-associated oral lesions: prevalence in Zambia. Oral Dis 1997;3:S46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matee M, Scheutz F, Moshy J. Occurrence of oral lesions in relation to clinical and immunological status among HIV-infected adult Tanzanians. Oral Dis 2000;6:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palacio H, Hilton J, Canchola A, Greenspan D. Effect of cigarette smoking on HIV-related oral lesions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1997;14:338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton LL. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of oral opportunistic infections in adults with HIV/AIDS as markers of immune suppression and viral burden. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;90:182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lifson AR, Hilton JF, Westenhouse JL, et al. Time from HIV seroconversion to oral candidiasis or hairy leukoplakia among homosexual and bisexual men enrolled in three prospective cohorts. AIDS 1994;8:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiboski CH, Neuhaus JM, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. The effect of receptive oral sex and smoking on the incidence of hairy leukoplakia in HIV-positive gay men. J Acquir Immune Def Synd 1999;21:236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clifford GM, Polesel J, Rickenbach M, et al. Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: associations with immunodeficiency, smoking, and highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engels EA, Biggar RJ, Hall HI, et al. Cancer risk in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Int J Cancer 2008;123:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS, et al. Incidence of types of cancer among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population in the United States, 1992–2003. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dawes C.Physiological factors affecting salivary flow rate, oral sugar clearance, and the sensation of dry mouth in man. J Dent Res 1987;66 Spec No:648–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navazesh M, Christensen C, Brightman V. Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of salivary gland hypofunction. J Dent Res 1992;71:1363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]