Abstract

Green innovation is currently recognized as a critical aspect for organizations to create economic value while contributing to ecological sustainability. Using the rationale of upper echelons theory, the present study introduces CEO narcissism, an important but underexplored psychological trait, and dynamic capability to probe the mechanisms driving green innovation. The regression findings show that enterprises with narcissistic CEOs do better in terms of green innovation. According to the mediation study findings, dynamic capability mediates between the CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation. In addition, the examination of mediated moderation reveals that top management risk aversion could negatively moderate this mediation effect. Such observations not only show that the CEO's personality has the potential to enhance corporate green achievements, but also discover the underlying mechanism which would provide guidance to help firms to be green.

Keywords: Green innovation, CEO narcissism, Dynamic capability, Risk aversion

1. Introduction

Being green is becoming a vital contemplation for organizations on the planet due to the grave environmental degradations and the mounting public voices [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. Regarded as a catalytic agent of the marriage between business and ecological sustainability, green innovation, the betterments of products or processes to lessen pollution and meet ecological protection requirements [[8], [9], [10], [11]], is spontaneously adopted by an increasing number of organizations to create economic value while contributing to sustainable development [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. The achievements of green innovation often help firms to take the high road to satisfy stakeholders, build favorable reputation, attract potential customers, and attain competitive advantages [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. However, the pursuit of green innovation entails significant expenditure and uncertainty, which leads to insufficient motivation of enterprises for green innovation. Therefore, it is critical to investigate the driving elements of green innovation.

Previous literature has recognized distinct antecedents of green innovation through various lens. Recent studies on corporate green innovation behavior have emphasized that eco-friendly innovation could be responses to the expectations from stakeholders, such as investors, customers, suppliers, communities, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), and so on [10,14,16,[21], [22], [23]]. Exploring through a institutional perspective, scholars discovered that pressures or supports for both formal (e.g. laws, regulations, and rules) and informal institutions (e.g. norms, cultures, and ethics) could play a prominent role in adopting of green innovation [9,17,24,25]. Researchers also identified intrinsic drivers of green innovation performance within firms themselves, such as corporate governance and firms’ life cycle stages [12,26]. These theories have cast new insights on the origins of green innovation.

Nevertheless, research on the internal drivers of green innovation behavior, especially the subjective initiative from the top management team, has been limited. Upper echelons theory argues that top managers’ individual psychological traits are destined to exert great influence on organizational strategies and performance [20,27]. From this perspective, the choices of executives could be influenced by their personal values, dispositions, and prior experiences. The personalities of corporate executives, especially CEOs, might affect organizational behaviors, with green innovation included.

Narcissism, a rapidly growing focus in psychology and management fields, is exhibiting its strategic prominence and undervalued visibility [28,29]. Concerning CEOs’ narcissistic traits, the extant research has examined its impact on organizational innovation strategy [30], corporate social responsibility performance [31] and corporate financial report quality [32]. However, there has been limited research on corporate green innovation behavior. CEO narcissism as significant traits and research hotspots [14,32], its potential impact on corporate green innovation pertains to the claim made by upper echelons theory that major organizational choices, actions, and results may be explained by the psychological characteristics of the top management team [27,30,31]. Thus, this study investigated the influence of CEO narcissism on corporate green innovation behavior through the lens of upper echelons theory.

Theoretically, narcissistic CEOs tend to exhibit overblown views of themselves and like to reinforce favorable self-perceptions [[33], [34], [35]]. While the actions of engaging in green innovation induce public attention and social recognition, it would be in line with the value judgements of narcissistic CEOs [36]. By achieving improvements of products or processes through environmental-friendly innovative efforts, green innovation comprises both value creation and environmental responsibility. Such dual nature of green innovation makes a new way to explore narcissistic CEOs' managerial implications in corporate decision-making toward sustainable development. The theoretical gaps to be explored and tested could be summarized in three aspects. First, whether corporate green innovation could benefit from CEOs' narcissism? Second, what is the mechanism between narcissistic CEOs and green innovation? Third, are there any other key factors that might affect the association between CEOs’ narcissism and green innovation?

The current study, on this basis, aims to address the gaps through the tenets of upper echelons theory. Based on upper echelons theory, the psychological characteristics of top management are a fundamental determinant of corporate behavior and performance. This study tries to identify whether corporate CEOs’ personality characteristics, such as narcissism, have influence on green innovation, and what the inherent mechanisms are for implementing innovative eco-friendly practices. By surveying sample of manufacturing firms in China and analyzing with moderating and mediating models, the empirical results demonstrate that CEO narcissism could lead organizations to better green innovation performance. Moreover, this association might be dependent on the internal capacity building as well as the interactions with risk cognition in leadership.

The main contributions of this study lie in three aspects. First, this research adds to the application of upper echelons theory via the lens of CEO personality qualities. This study comprehensively probes the logic that the value of executives’ psychological characteristics in pursuing green innovatively. Second, this study adds to the body of knowledge about the factors that drive corporate green innovation. Previous studies on green innovation behavior have focused on the institutional level [9,17,24,25] and organizational level [15,37,38], with little emphasis paid to the individual level, particularly the influence of senior managers' psychological qualities. Third, the research findings have significant practical implications for both businesses and policymakers. The findings offer organizations insights into how to improve the composition of their senior management teams. They might also assist governments in developing policies that promote effective value development while simultaneously ensuring environmental sustainability.

1.1. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

1.1.1. CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation

Upper echelons theory points out that organizational top executive managers often make decisions based on their own personalized cognition [27,33]. These top executives, especially CEOs, could dominate organizational strategies or behaviors, and then exert substantial effects on organizational efforts and outcomes. Thus, CEOs will very likely to engage in activities satisfying their personal preference and values [[39], [40], [41]]. For instance, the demographics of CEOs, such as age, gender, academic background, or professional experience, are related to the organizational motivations for environmental issues [20,42] as well as their psychological traits including cognition, emotion, and preference [43].

Narcissism refers to the extent to which one person is arrogant and seeks for satisfaction of arrogance from others [29,33,34]. Narcissistic CEOs might tend to exhibit overblown views of themselves and like to reinforce favorable self-perceptions [35]. Some narcissistic CEOs are eager to highlight their prominence in organizations and willing to choose differential strategies or behaviors which may lead to potential risks or fluctuating outcomes [40,44]. This individual characteristic accounts for an important source of differences in organizational performance. Previous literature has provided evidence that a narcissist is sensitive to public evaluations and strongly motivated to choose strategies that could promote “positive self” [41,45]. Therefore, it could be a viable choice for narcissistic CEOs to obtain media attention or public admiration, since green innovation exhibits special concerns regarding social welfare. Besides, CEO narcissism has been examined to be positively associated with corporate social responsibility [36]. In this perspective, narcissistic CEOs may encourage companies to actively pursue green development for showcasing responsible and towering image of the organizations.

Theoretically, narcissism consists of individual motivations and behaviors stemmed from psychological activities [27]. From the motivational perspective, narcissistic CEOs often stand on tiptoe to gain others' attention and praise [35]. They exert themselves to maintain a favorable image of their own by those positive opinions and feedback [34,44]. When stakeholders are progressively interested in business practices that should be good for sustainability, activities of green innovation will convey to positive signals of corporate strategic choice towards public concerns and social welfare to them [46]. Narcissistic CEOs will naturally embrace green innovation to win more applause and praise from various stakeholders [28]. Especially, media and public express high recognition of moral concerns on environmental responsibility, CEOs can readily satisfy their demands for showing off. A CEO with higher narcissism will actively promote green innovation to gain others' admiration with less focus on organizations, even if being green could increase cost or encounter failures [28]. From the behavioral perspective, CEO narcissism favors dramatic and bold behaviors and often endorses unconventional actions which may stimulate creativity as well as risk-taking [33,44]. Because doing prosocial behaviors can alter the status quo and encourage narcissistic CEOs to do well, it could be a value-added way of supplying narcissism for CEOs [28]. Developing green products/processes innovatively offers a relatively high probability of better performance and competitive edge [6,9]. It would consequently enhance narcissistic CEOs’ feelings of superiority and encourage them to select proactive engagement in green innovation to outperform competitors [34]. If their cognition of green innovation becomes clearer, narcissistic CEOs prefer to adopt it to embody sense of arrogance and strengthen moral authority to prove personal value and spotlight image.

Therefore, green innovation can meet the requirements of narcissistic CEOs for their own attention and image reinforcement, we could propose that:

Hypothesis 1

CEO narcissism is positively related to corporate green innovation.

1.1.2. Mediating role of dynamic capability

Although narcissistic CEOs may choose green innovation as a helpful tool for exhibitionism, attention, and reputation, the successful green innovation cannot take the place of specific actions. Corporate strategic choice should be realized through organization-level competences since it is insufficient produce to substantive outcome [47,48]. Enabling innovation depends not only on the initiation from top management and resources of the organizations, but also on the broader knowledge capability [49]. Dynamic capacity, a prominent origin of performance disparities, proposes a potential association between CEO narcissism and environmentally innovative outputs.

Dynamic capability refers to organizational ability to build competencies both inside and outside when facing a circumstance that is evolving quickly [50,51]. It reflects the capacity to conduct particular tasks (e.g. innovating new products or processes, establishing partnerships, or developing new business models) to advance organizational learning in sync with externally fast-paced technological and marketing evolution [52]. From a dichotomized view, dynamic capacity could be separated into internal and external aspects [53]. The external dimension of dynamic capacity, namely sensing, refers to the ability of opportunity recognizing by searching and exploring across distinct technologies and markets. The internal dimension, namely reconfiguring, focuses on the ability of opportunity-seizing which convert the possibility into real outcomes [47,50]. While dynamic capacity is the critical process to transform corporate strategies into substantial performance, it is a possible mechanism to connect CEO narcissism and green innovation based on the logic of motivation-execution-performance.

From the external perspective, narcissistic CEOs depend on sensing process to find opportunities for showing off or attracting audiences. Organizations with continuous progresses in sensing gain a better understanding of hot spots or changing trends. CEO narcissism could adopt bold and radical behaviors to timely cater for fast-paced changes. Thus, as a forerunner of dynamic capability, CEOs with high levels of narcissism can enjoy rewards from frequent external discoveries. The stronger opportunity-recognizing capability is built, the better green innovation an organization will accomplish. Narcissistic CEOs could facilitate the adoption of organizational strategy as they are likely to make the most of discretion to satisfy their personal values by influencing over strategic decisions [4]. The adoption of targeted strategy is bound to exert influence on the organizational ability with dynamic capability included. From the internal perspective, narcissistic CEOs rely on the reconfiguration process to demonstrate value or showcase their image. The full usage of inputs from sensing processes is facilitated by organizations with proper routine and procedure reconstruction. The narcissistic CEO might then marshal all available resources to ensure execution. The greater an organization's dynamic capability is promoted, the more frequently it engages in sensing and reconfiguring [53]. Then, green innovation will benefit from narcissistic CEOs' desire to win admiration and efforts for authority asserting.

Effective realizations of narcissistic CEOs’ pursuits for green innovation largely depend upon dynamic capability, thus, we could propose that:

Hypothesis 2

Dynamic capability mediates the association between CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation.

1.1.3. Moderating role of top management risk aversion

While uncertainty in innovation is inevitable, being green innovatively might encounter unexpected failures [4]. Top managers' attitudes to risks and uncertainty are also a critical determinants of innovation adopting [54]. Previous literature has demonstrated that the risk aversion in leadership would weaken inter-functional cooperation, avoid failures, and repress creative ideas, leading to poor innovation performance [55]. When managerial risk aversion is low, narcissistic CEOs would be encouraged to take innovation failures as normal procedure and be more likely to expand existing capabilities and implement new technologies to meet the needs for self-enhancement or image-making. They would consequently input more organizational resources into the activities in responding to the growing environmentalisms. Correspondingly, the low tolerance of risks hates radical and divergent thoughts as well as dramatic and bold behaviors [56]. Narcissistic CEOs have to seriously take into account risks and make some concessions in the way of satisfying personal preference. External integration and internal reconfiguration involve considerable costs (e.g. adjustment and adaption), capability reconstruction may result in transformation failures, the trap that organizations are trying to elude. Therefore, higher risk aversion in leadership naturally restricts narcissistic CEOs’ managerial discretions and self-interest pursuits. There will be much difficulties in routine and procedure reconfigurations even if they are necessary. The benefits of opportunity-recognizing and capitalizing from CEO narcissism would be impeded.

Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 3

The mediating effect of dynamic capability on the association between CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation is stronger when top management risk aversion is lower.

The conceptual framework is shown in Fig. 1 with CEO narcissism as the independent variable, dynamic capability as the mediator, top management risk aversion as the moderator, and corporate green innovation as the dependent variable.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model.

Note: This figure displays the conceptual framework verified in the present study.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample

To test the aforementioned hypotheses, samples were gathered by surveying manufacturing enterprises in Yangtze Delta of China. The present study used questionnaires organized from existing literature and fulfilled following by the standard steps in order to avoid cultural bias and guarantee validity [47,57]. In addition, ex-ante procedural remedies were accepted to lessen the bias introduced by common methods [58]. The questionnaire was divided into two sections in order to prevent biases caused by self-assessment. One section which contained dependent, moderating and control variables was sent to senior executives. The other section dealt with independent and mediating variables, and was sent to marketing managers to evaluate CEOs. In order to verify the phraseology, clarity, and content, we conducted a pretest before on-site distribution through interviews with four corporate senior managers and four experienced academics. Meanwhile, we randomly chose enterprises in industries of different geographical locations and sizes to maximize variability. We took security measures to ensure that informant would remain anonymous. After the datasets are combined and encoded, 273 response firms were included for data analysis. Table 1 displays the distribution of the samples, which were comparable to ratios can be found in previous studies [57].

Table 1.

Distribution of the samples.

| Ownership structure | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Private enterprises | 56.11 | |

| Jointed ventures | 17.33 | |

| Foreign-investment enterprises | 12.86 | |

| State-owned enterprises |

7.69 |

|

| Industry ID | Description | Percentage |

| Industry 1 | machine and equipment industries | 31.03 |

| Industry 2 | metal and nonmetal manufacturing industries | 13.56 |

| Industry 3 | electronic products industry | 18.3 |

| Industry 4 | petroleum and chemical industries | 9.52 |

| Industry 5 | textile and garment industries | 4.64 |

| Industry 6 | paper-making and printing industries | 3.67 |

| Industry 7 | wood and furniture | 8.98 |

| Industry 8 | pharmaceuticals and food | 9.16 |

Note: This table displays the distribution of the samples used in the present study.

2.2. Measures

Perception-related factors were accessed by seven-point Likert type scales ranging from not at all (1) to very much (7). Following prior study [47], average scores were calculated to measure variables with multi-item constructs. The operationalization of the variables is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operationalization of the variables.

| Variables | Cronbach's alpha | Operationalization (Sample items) |

|---|---|---|

| CEO narcissism | 0.974 | “Assertive”, “Arrogant”, “Egotistical”, “Boastful”, “Conceited”, “Show-off”, “Self-centered”, and “Temperamental” |

| Green innovation | 0.926 | Green process innovation: “minimizing the use of electricity, water, oil, or coal”, “minimizing the consumption of raw materials”, and “minimizing the emission of hazardous substances or waste”; Green product innovation: “selecting the product materials with the least pollution”, “using the fewest materials to produce products”, and “deliberately considering whether the products are easy to decompose, recycle and reuse” |

| Dynamic capability | 0.947 | Sensing: “participating in professional association activities, professional conferences or scientific conferences actively”, and “identifying target market opportunities and changing customer needs by using established processes”; Reconfiguration: “adopting substantial changed company strategies or new management methods” and “substantially recovering business processes” |

| Top management risk aversion | 0.860 | “top managers insist on avoiding taking big risks”, “senior managers believe that it is not worth taking higher risks to get higher returns”, and “senior managers support the implementation of innovative marketing strategies, being able to withstand some possible failures.” |

2.3. CEO narcissism

On the basis of the existing literatures [34,40], CEO narcissism was evaluated by eight items, including Assertive, Arrogant, Egotistical, Boastful, Conceited, Show-off, Self-centered, and Temperamental. In the interviews, the respondents were asked to rate how accurately these eight words described their CEOs.

2.4. Green innovation

Green innovation is generally considered to be a conceptual synthesis. In the literatures, it was commonly defined as the integration of green process innovation and green product innovation [9,10]. Respectively, green process innovation was usually accessed by three items, emphasizing on the contribution to the sustainable manufacturing process in the aspects of required production materials and concomitant pollution. In terms of required production materials, sample items were “minimizing the use of electricity, water, oil, or coal”, and “minimizing the consumption of raw materials.” Production pollution item was “minimizing the emission of hazardous substances or waste”. Green product innovation was evaluated by another three items, respectively were “selecting the product materials with the least pollution”, “using the fewest materials to produce products”, “deliberately considering whether the products are easy to decompose, recycle and reuse."

2.5. Dynamic capability

Dynamic capability could be separated into two indispensable abilities of sensing and reconfiguration [53]. According to prior literatures, five items were used to evaluate sensing, focusing on events that exert firms to absorb knowledge from the external environment [47,59]. Items for measurement were “participating in professional association activities, professional conferences or scientific conferences actively” and “identifying target market opportunities and changing customer needs by using established processes”. Reconfiguration was evaluated through using another seven-item scale emphasizing organizational change arising from absorbed knowledge. Items for measurement could be divided into “adopting substantial changed company strategies or new management methods” and “substantially recovering business processes".

2.6. Top management risk aversion

Top management risk aversion reflects the decision-making risk aversion preference of top managers [1]. According to the previous literature, top management risk aversion was evaluated by three items [60]. Respectively, these items include “top managers insist on avoiding taking big risks”, “senior managers believe that it is not worth taking higher risks to get higher returns”, and “senior managers support the implementation of innovative marketing strategies, being able to withstand some possible failures.”

2.7. Control variables

According to previous literatures [3,20,29,34], we considered the potential influence of firm attributions. Specifically, different ownerships were controlled: state-owned enterprise, collective state-owned enterprises, private enterprise, and exclusively foreign-owned enterprise, where all were encoded as 1 (yes), 0 (no). Another eight dummy variables were used to control different industries impact. Moreover, we also controlled for some other variables: the number of employees, high and new technology is adopted or not (1 = yes, 0 = no), environmental executives is available or not (1 = yes, 0 = no), and nine industries (Ind 1–9).

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory factor analysis

Since the adopted scales are relatively mature and the sample size meet the basic requirements, Confirmatory factor analysis (CFAs) are utilized to test construct validity [57,61]. The results are displayed in Table 3. The baseline model is compared with the other six alternate models. It could be seen from Table 3 that the baseline model fits best and achieves the best construct validity (χ2/df = 3.232, IFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.910, CFI = 0.920, RMSEA = 0.091, SRMR = 0.060). That means our model fit is acceptable.

Table 3.

Comparison of measurement models.

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | Δχ2/Δdf | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 794.972 | 246 | 3.232 | – | 0.920 | 0.910 | 0.920 | 0.091 | 0.060 |

| Three factors -GI + MAR | 1258.091 | 296 | 4.250 | 69.815 | 0.871 | 0.858 | 0.871 | 0.109 | 0.068 |

| Three factors -DC + GI | 1995.485 | 296 | 6.742 | 115.982 | 0.773 | 0.750 | 0.772 | 0.145 | 0.103 |

| Three factors -CEON + DC | 2765.339 | 296 | 9.342 | 101.040 | 0.670 | 0.636 | 0.669 | 0.175 | 0.253 |

| Two factors -GI + MAR,CEON + DC | 2973.303 | 298 | 9.978 | 104.799 | 0.642 | 0.609 | 0.641 | 0.182 | 0.254 |

| Two factors GI + DC,MAR + CEON | 2467.712 | 298 | 8.281 | 170.033 | 0.710 | 0.683 | 0.709 | 0.164 | 0.175 |

| One factors | 1780.800 | 170 | 10.475 | 662.193 | 0.672 | 0.632 | 0.671 | 0.187 | 0.105 |

CEON = CEO Narcissism; MAR = Top Management Risk Aversion; DC = Dynamic Capability; GI = Green Innovation.

Note: This table provides confirmatory factor analysis which shows our model fit is acceptable.

3.2. Regression analysis

Descriptive statistics and the results of Pearson correlation among variables are displayed in Table 4. The correlation coefficients among variables are all less than 0.61, which has ensured the reliability of this study.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

| Mean | SD | SE | JV | PE | FE | NE | HNTA | EEA | CEON | DC | MRA | GI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 0.077 | 0.267 | 1 | ||||||||||

| JV | 0.096 | 0.295 | −0.094 | 1 | |||||||||

| PE | 0.533 | 0.500 | −0.309** | −0.247** | 1 | ||||||||

| FE | 0.059 | 0.236 | −0.072 | −0.081 | −0.267** | 1 | |||||||

| NE | 2.796 | 1.113 | 0.041 | −0.111 | −0.030 | 0.161** | 1 | ||||||

| HNTA | 0.713 | 0.505 | 0.001 | 0.122 | −0.182** | 0.019 | 0.317** | 1 | |||||

| EEA | 0.612 | 0.534 | 0.030 | 0.058 | −0.087 | 0.006 | 0.273** | 0.417** | 1 | ||||

| CEON | 4.199 | 1.823 | 0.008 | 0.020 | −0.030 | −0.028 | −0.041 | 0.071 | 0.056 | 1 | |||

| DC | 5.147 | 1.122 | −0.125* | 0.041 | 0.056 | −0.004 | 0.022 | −0.028 | 0.014 | 0.315** | 1 | ||

| MRA | 4.929 | 1.313 | −0.103 | −0.065 | 0.057 | 0.077 | −0.008 | −0.125 | −0.134* | 0.028 | 0.391** | 1 | |

| GI | 5.274 | 1.186 | −0.134* | 0.032 | 0.071 | −0.005 | 0.012 | −0.128* | −0.058 | 0.160** | 0.579** | 0.608** | 1 |

SE = State-owned Enterprises; JV = Jointed Ventures; PE = Private Enterprises; FE = Foreign-investment Enterprises.

NE = The Number of Employees; HNTA = High and New Technology is Adopted or not; EEA = Environmental Executives is Available or not.

Table 5 reports summary of regression analyses. We use OLS to estimate coefficients of the regression models. These results offer comprehensive test to abovementioned hypotheses. Model 1 is established as a baseline with only control variables. Model 2 explicitly proves a significantly positive relationship between CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation (β = 0.104, p = 0.008). Thus, we verify Hypothesis 1, revealing a Bright-Side of CEO narcissism.

Table 5.

Results of regression analyses.

| GI |

DC |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 |

Model2 |

Model3 |

Model4 |

Model5 |

Model6 |

Model7 |

||||||||

| Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | Coefficient(T) | P | |

| Const. | 5.703***(21.954) | <0.001 | 5.274***(17.460) | <0.001 | 2.281***(6.406) | <0.001 | 2.302***(6.434) | <0.001 | 5.090***(21.311) | <0.001 | 4.329***(16.320) | <0.001 | 4.942***(22.997) | <0.001 |

| Industry 1 | −0.044 (-0.120) | 0.904 | −0.065 (-0.180) | 0.858 | −0.128 (-0.442) | 0.659 | −0.125 (-0.432) | 0.666 | 0.124 (0.369) | 0.712 | 0.087 (0.275) | 0.783 | 0.170 (0.560) | 0.576 |

| Industry 2 | −2.188***(-5.568) | <0.001 | −2.093***(-5.379) | <0.001 | −1.079**(-3.334) | 0.001 | −1.076**(-3.321) | 0.001 | −1.649***(-4.566) | <0.001 | −1.482***(-4.336) | <0.001 | −0.733*(-2.077) | 0.039 |

| Industry 3 | −0.354 (-0.561) | 0.575 | −0.342 (-0.549) | 0.583 | −0.072 (-0.145) | 0.885 | −0.069 (-0.138) | 0.890 | −0.420 (-0.723) | 0.470 | −0.398 (-0.728) | 0.467 | −0.307 (-0.594) | 0.553 |

| Industry 4 | 0.337 (1.476) | 0.141 | 0.305 (1.351) | 0.178 | −0.008 (-0.046) | 0.964 | −0.009 (-0.047) | 0.962 | 0.514*(2.447) | 0.015 | 0.456*(2.304) | 0.022 | 0.381*(2.030) | 0.044 |

| Industry 5 | 0.040 (0.154) | 0.878 | −0.012 (-0.046) | 0.963 | 0.085 (0.414) | 0.679 | 0.097 (0.471) | 0.638 | −0.067 (-0.279) | 0.780 | −0.159 (-0.703) | 0.483 | −0.177 (-0.825) | 0.410 |

| Industry 6 | −0.337 (-0.529) | 0.597 | −0.055 (-0.087) | 0.931 | −0.417 (-0.830) | 0.408 | −0.480 (-0.939) | 0.349 | 0.119 (0.202) | 0.840 | 0.619 (1.105) | 0.270 | 0.933 (1.746) | 0.082 |

| Industry 7 | 0.250 (1.344) | 0.180 | 0.186 (1.005) | 0.316 | 0.312*(2.128) | 0.034 | 0.328*(2.204) | 0.029 | −0.092 (-0.540) | 0.590 | −0.206 (-1.267) | 0.206 | −0.171 (-1.116) | 0.266 |

| Industry 8 | 0.450 (1.813) | 0.071 | 0.335 (1.348) | 0.179 | 0.127 (0.644) | 0.520 | 0.145 (0.728) | 0.467 | 0.480*(2.104) | 0.036 | 0.276 (1.266) | 0.207 | 0.151 (0.729) | 0.467 |

| SE | −0.644*(-2.237) | 0.026 | −0.646*(-2.275) | 0.024 | −0.312 (-1.364) | 0.174 | −0.304 (-1.328) | 0.186 | −0.494 (-1.866) | 0.063 | −0.498*(-1.997) | 0.047 | −0.358 (-1.510) | 0.132 |

| JV | 0.152 (0.569) | 0.570 | 0.159 (0.605) | 0.546 | 0.071 (0.337) | 0.737 | 0.067 (0.320) | 0.749 | 0.120 (0.491) | 0.624 | 0.133 (0.578) | 0.564 | 0.203 (0.929) | 0.354 |

| PE | −0.119 (-0.631) | 0.528 | −0.109 (-0.589) | 0.556 | −0.123 (-0.830) | 0.407 | −0.125 (-0.843) | 0.400 | 0.006 (0.036) | 0.971 | 0.023 (0.141) | 0.888 | 0.075 (0.484) | 0.629 |

| FE | −0.272 (-0.848) | 0.397 | −0.227 (-0.718) | 0.473 | −0.261 (-1.035) | 0.302 | −0.270 (-1.069) | 0.286 | −0.016 (-0.053) | 0.958 | 0.063 (0.227) | 0.821 | 0.052 (0.198) | 0.843 |

| NE | 0.001 (0.020) | 0.984 | 0.009 (0.124) | 0.901 | −0.026 (-0.474) | 0.636 | −0.028 (-0.511) | 0.610 | 0.041 (0.638) | 0.524 | 0.054 (0.886) | 0.377 | 0.060 (1.035) | 0.302 |

| HNTA | −0.276 (-1.663) | 0.098 | −0.284 (-1.736) | 0.084 | −0.243 (-1.855) | 0.065 | −0.240 (-1.833) | 0.068 | −0.050 (-0.327) | 0.744 | −0.064 (-0.448) | 0.655 | −0.015 (-0.112) | 0.911 |

| EEA | −0.183 (-1.224) | 0.222 | −0.189 (-1.278) | 0.203 | −0.146 (-1.236) | 0.218 | −0.144 (-1.218) | 0.225 | −0.056 (-0.404) | 0.687 | −0.065 (-0.503) | 0.615 | 0.023 (0.186) | 0.853 |

| CEON | 0.104**(2.683) | 0.008 | −0.023 (-0.686) | 0.493 | 0.185***(5.419) | <0.001 | 0.202***(6.115) | <0.001 | ||||||

| DC | 0.672***(11.741) | <0.001 | 0.686***(11.258) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| MRA | 0.235***(4.949) | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| CEON*MRA | −0.049*(-2.242) | 0.026 | ||||||||||||

| R-sq | 0.202 | 0.227 | 0.507 | 0.508 | 0.159 | 0.256 | 0.343 | |||||||

| F | 3.774 | 4.086 | 14.316 | 13.469 | 2.814 | 4.807 | 6.408 | |||||||

Independent variable: CEON; Mediating variable: DC; Moderating variables: MRA.

Note: This table summarizes the regression analyses which provide comprehensive test to the hypotheses.

To test Hypothesis 2, we introduce the three steps procedure to demonstrate that dynamic capability plays as a mediator between CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation [34,62]. According to the previous works [63,64], we have verified the mediation hypothesis through the following processes. Compared with the controlled Model 5, Model 6 shows that dynamic capability is positively associated with CEO narcissism (β = 0.185, p < 0.001). Dynamic capability is also positively associated with corporate green innovation, see Model 3 (β = 0.672, p < 0.001). It indicates that firms with stronger dynamic capability are more likely to have better green innovation achievements. Controlled dynamic capability in Model 4, CEO narcissism is no longer significantly associated with corporate green innovation (β = −0.023, p = 0.493). Taking together, Models 2, 4, and 6 jointly provide a three-step test for mediating analysis. We also conducted an additional Sobel test for reliability, which displayed a significant mediation effect (Effect = 0.127, SE = 0.026, Z = 4.869, P < 0.001). The positive relationship between CEO narcissism and corporate green innovation is fully mediated by the dynamic capability. We also conduct a bootstrap test to verify the indirect effect of CEO narcissism on corporate green innovation for the sake of reliability. Results confirm the complete mediation effect (β = 0.139, S.E. = 0.031, 95%C.I. = 0.084–0.205). Thus, we verify Hypothesis 2. These observations reveal a potential benefit of CEO narcissism. Organizations with narcissistic CEOs tend to partake in sensing and reconfiguring with higher frequency and intensity. Then, green innovation will be nurtured from the narcissistic CEOs’ efforts for gaining admiration and maintaining authority.

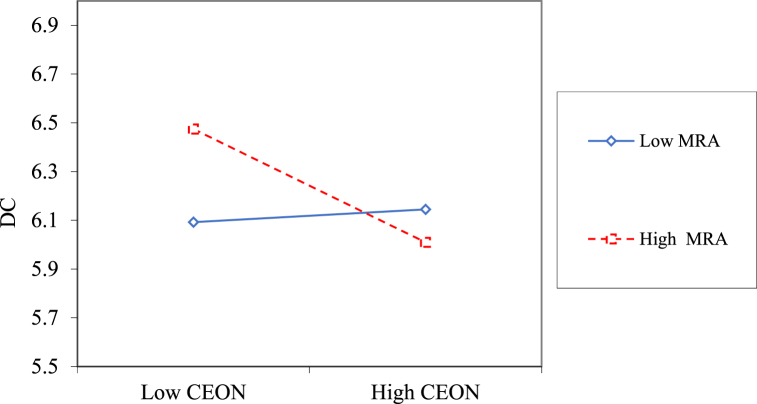

To test whether top management risk aversion plays a role of moderator, moderated mediation regression framework is used to analyze the intrinsic mechanism. We investigated the mediated-moderation model illustrated in Fig. 1 via Hayes' PROCESS methodology [65]. The corresponding variables used to generate the interaction term are all mean-centered prior to the regression analyses for preventing any potential multicollinearity. The result of the moderation analysis is listed in Model 7. CEO narcissism continues to be positively associated with corporate green innovation (β = 0.202, p < 0.001). Top management risk aversion significantly moderates the association between CEO narcissism and corporate dynamic capability (β = −0.049, p = 0.026). As expected, the significantly negative coefficient of interaction term suggests that high CEO narcissism would lead to stronger dynamic capability when top management risk aversion is lower (see Fig. 2). These findings preliminarily validate Hypothesis 3. Bootstrap test with 1000 bootstrap samples is used to further verify the conditional indirect effect, which reconfirms the abovementioned mediation effect of dynamic capability (see Table 6). The direct effect of CEO narcissism remains insignificant. Conditional effect tests confirm that top management risk aversion plays as a moderator in the indirect effect of CEO narcissism on green innovation. The varying degree of indirect impacts according to level of top management risk aversion is displayed in Table 6. For low (β = 0.150, S.E. = 0.045, 95% C.I. = 0.068–0.245), middle (β = 0.112, S.E. = 0.027, 95% C.I. = 0.065–0.172), and high levels of top management risk aversion (β = 0.075, S.E. = 0.025, 95% C.I. = 0.026–0.125). The indirect impact of CEO narcissism on green innovation through dynamic capability is considerable in the three degrees. Therefore, we verify the Hypotheses 2 and 3. In the case of high management risk aversion in leadership, narcissistic CEOs’ managerial discretions and self-interest pursuits are naturally restricted. The benefits of opportunity-recognizing and capitalizing from CEO narcissism would be impeded. In consequence, firms with narcissistic CEOs are less likely to develop green innovation rooted in corporate dynamic capability. In contrast, when managerial risk aversion is low, narcissistic CEOs would be encouraged to take innovation failures as normal procedure and be more likely to expand existing dynamic capabilities, consequently fostering better green innovation.

Fig. 2.

The moderating effect of Top management risk aversion (MRA) on the relationship between CEO narcissism (CEON) and Dynamic capability (DC).

Table 6.

Moderated mediating effect of CEO narcissism on green innovation through dynamic capability moderated by top management risk aversion.

| Effect | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | −0.029 | 0.019 | −0.065 | 0.007 |

| Indirect(M-1SD) | 0.150 | 0.045 | 0.068 | 0.245 |

| Indirect(M) | 0.112 | 0.027 | 0.065 | 0.172 |

| Indirect(M + 1SD) | 0.075 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.125 |

Notes: This table provides summary of bootstrap test with 1000 bootstrap samples which confirms the mediation effect of dynamic capability.

4. Discussion

Due to the severity of environmental degradation and the growing of public outcry, being green is becoming an essential consideration for enterprises worldwide [3,5,66]. Therefore, integrating environmental concerns into business is an effective activator for opportunities-seizing and value-generating. Green innovation, which aims to minimize pollution and satisfy the standards of ecological protection through the enhancement of products and processes, is regarded as the catalyst for the fusion of business and ecological sustainability [[8], [9], [10]]. Due to the fact that green innovation frequently creates or incorporates new technology into the commercial process of production, management, or services, it helps to reduce harmful environmental effects like resource usage or environmental pollution [8]. Inspired by the upper echelons theory that a CEO's narcissism may have a substantial impact on the adoption of eco-friendly innovative activities, which might attribute to the top managers' desire for personal reputation and public attention [20,31]. The current study examined if and how the CEO's narcissistic affects green innovation from a dynamic capacity viewpoint. And the process by which narcissistic CEOs influence corporate green innovation and the circumstances in which this may happen were also well-discussed. Drawing on sample of Chinese manufacturing enterprises, the empirical findings demonstrated that the CEO narcissism has a favorable influence on the corporate green innovation performance. In addition, dynamic capability significantly mediated the favorable effect of CEO narcissism. It was also shown that top management risk aversion restrains the dynamic capability's mediating function.

4.1. Theoretical contributions

Evidences from previous researches have validated the direct effect of green innovation on environmental performance, which tell a dominant role of green innovation in green development [67]. In the previous works, the initiation from top management and resources of the organizations and society to drive green innovation and sustainable performance has been widely studied, such as intellectual property rights, government support, coopetition strategy, digitalization capability [[68], [69], [70]]. Nevertheless, research on the internal drivers of green innovation behavior, especially the personality of the executive officers, has been limited. This work investigates the impact of narcissistic CEOs and makes three contributions that might extend comprehension about the effect of CEO narcissism on green innovation. First, by connecting CEO's narcissism and green innovation performance, our research advances the existing discussion on green corporate practices. Although various researches have highlighted the impact of CEO narcissism, few have investigated through which way CEO narcissism could become an efficient driver of corporate green innovation. Intentionally, this study has begun to look into the causes and circumstances of CEO narcissism as they relate to green innovation. We expect that our findings will help people understand how psychological traits of CEOs affect pro-social business activities. Based on the upper echelons theory, this study supports a recent call for additional research on the function of the CEO in corporate eco-friendly behaviors and offers empirical proof that the narcissistic nature of CEO does have a favorable impact on the implementation of green innovation [71,72]. Therefore, the personal motivation of senior managers may serve as a key catalyst for green innovation initiatives. The personal traits of CEOs may be advantageous to delivering economic value and ecological preservation, even though corporate green innovation is a constructive response to the mounting demand from environmental consensus throughout the world. The current findings extend the theoretical justification and provide supporting results, which improve the existing literature and add fresh insight into the link between CEOs' narcissism and corporate green innovation.

Second, this study fills the knowledge gaps by figuring out the ways in which corporate green innovation might internalize CEO narcissism to accomplish prosocial goals. A company's internal operations and external forces might shape and impact how its strategic implementation is carried out. Naturally, it takes a suitable organizational setup and sufficient mobilizations to harness resources in order to translate leaders' preferences into meaningful business actions. Dynamic capability, which is both a proclamation of the future and a vehicle for management self-interest, may spontaneously translate the unique psychological characteristics of CEOs into the activities of green innovation. To continually achieve improvements of products or processes through environmental-friendly innovative efforts, firms must foster their abilities to seize new opportunities. Besides, the impact of CEOs' psychological characteristics on the success of prosocial initiatives depends on the setting [47]. The function of dynamic capability should be fused with organizational attributes. Higher risk aversion in leadership would restrict narcissistic CEOs' managerial discretions and self-interest pursuits. The benefits of opportunity-recognizing and capitalizing from CEO narcissism would be impeded. In this perspective, these observations have outlined the nature and function of CEO narcissism in the corporate green innovation.

Third, our work contributes to environmental researches in developing economies and provides empirical evidence to the controversy on the role of CEO narcissism on corporate innovation. As a typical emerging economy, China is facing big challenges of green development [2,28,73]. The ongoing structural reforms and growing calls for environmental protection significantly shape managerial criteria and assumptions [3,47,74,75]. Green innovation is becoming increasingly popular for enterprises over the world. On this basis, taking executives’ nature into consideration, this study could be utilized to guide organizational leaders to promote green business.

4.2. Practical implications

The current empirical study also makes significant practical inferences for business executives and policymakers regarding green innovation adoption. On the one hand, it is deserved to mention that narcissistic CEOs own their bright side of green mindset, although narcissism was commonly regarded as a dark side of executive personality in the literatures [40,44]. The eagerness to win more applause and praise could spur narcissistic CEOs to embrace green innovation. To provide convenience, it is critical to develop and implement an integrated governance to sponsor this byproduct of narcissism. Of course, necessary organizational disciplines also should be implemented to restrain and guide behaviors. Managers also should try to adopt appropriate strategies to achieve a win-win situation that takes account both of green development and company interests. Moreover, firms must develop their own capabilities to seize the eco-related opportunities under certain conditions. Timely response to social interest in the natural environment with active reconfiguration could produce better eco-friendly outcomes. Policymakers, on the other hand, should concentrate their efforts to establishing appropriate policies to cultivate green development pattern [9]. Intentional interventions may provide essential supports for the efforts of SMEs to break the resource bottleneck and pursue green. It is urged to strengthen structural flexibility, entrepreneurial orientation and adaptive execution to make flexible and creative use of eco-related opportunities. Policy making must cater to the motivation of firms’ green development. Aroused stakeholders would undoubtedly dive into green actions.

4.3. Limitations and future work

First, it is noticeable that the perceptual measurements of variables have unavoidable drawbacks resulting from the subjectivity. Despite how challenging it is to assess personality, using objective data as supplemental evidence will be beneficial. Second, a cross-sectional questionnaire survey is used in the current study, which makes it impossible to capture dynamics. Our empirical evidence demonstrated the beneficial effects of narcissistic CEOs on corporate green behavior. The question of whether CEOs' narcissism would continue to have a good impact in the long run is left unanswered. Further longitudinal research should be undertaken to establish robust and validated conclusion. Third, the manufacturing enterprises in the Yangtze River Delta of China is the exclusive subject of this study's analysis of industrial companies. It is advised to include a comparison with established countries in our follow-up study, even if there are different administrative foundations of environmental activities in developed context.

Funding

This study was funded by Major Project of Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Education Department (21KJA630001, 22KJA630001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72271126, 72001112), and College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Jiangsu Province (202211287009Z).

Author contribution statement

Le Chang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Rui Liang: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Jinjin Zhang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Xue Yan: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Hao Tao; Tonghui Zhu: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Banerjee S.B. Managerial perceptions of corporate environmentalism: interpretations from industry and strategic implications for organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 2001;38:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H., Zeng S., Lin H., Ma H. Munificence, dynamism, and complexity: how industry context drives corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017;26:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han M., Lin H., Wang J., Wang Y., Jiang W. Turning corporate environmental ethics into firm performance: the role of green marketing programs. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019;28:929–938. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin H., Chen L., Yuan M., Yu M., Mao Y., Tao F. The eco-friendly side of narcissism: the case of green marketing. Sustain. Dev. 2021;29:1111–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter M.E., van der Linde C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995;9:97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi G.Y., Zeng S.X., Shi J.J., Meng X., Lin H., Yang Q. Revisiting the relationship between environmental and financial performance in Chinese industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2014;145:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sukhdev P. The corporate climate overhaul. Nature. 2012;486:27–28. doi: 10.1038/486027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arfi W.B., Hikkerova L., Sahut J.-M. External knowledge sources, green innovation and performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2018;129:210–220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong Q., Wu Y., Lin H., Sun Z., Liang R. Fostering green innovation for corporate competitive advantages in big data era: the role of institutional benefits. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022 doi: 10.1080/09537325.2022.2026321. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin H., Zeng S., Ma H., Qi G., Tam V.W. Can political capital drive corporate green innovation? Lessons from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014;64:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rennings K. Redefining innovation—eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000;32:319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amore M.D., Bennedsen M. Corporate governance and green innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2016;75:54–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Medeiros J.F., Vidor G., Ribeiro J.L.D. Driving factors for the success of the green innovation market: a relationship system proposal. J. Bus. Ethics. 2018;147:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han M., Lin H., Sun D., Wang J., Yuan J. The eco-friendly side of analyst coverage: the case of green innovation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2022.3148136. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhai Y., Cai Z., Lin H., Yuan M., Mao Y., Yu M. Does better environmental, social, and governance induce better corporate green innovation: the mediating role of financing constraints. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022;29:1513–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunapatarawong R., Martínez-Ros E. Towards green growth: how does green innovation affect employment? Res. Policy. 2016;45:1218–1232. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berrone P., Fosfuri A., Gelabert L., Gomez-Mejia L.R. Necessity as the mother of “green” inventions: institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strat. Manag. J. 2013;34:891–909. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: the mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011;104:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D., Huang M., Ren S., Chen X., Ning L. Environmental legitimacy, green innovation, and corporate carbon disclosure: evidence from CDP China 100. J. Bus. Ethics. 2018;150:1089–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun D., Zeng S., Lin H., Yu M., Wang L. Is green the virtue of humility? The influence of humble CEOs on corporate green innovation in China. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2021.3106952. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai W., Li G. The drivers of eco-innovation and its impact on performance: evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;176:110–118. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S.K., Del Giudice M., Chiappetta Jabbour C.J., Latan H., Sohal A.S. Stakeholder pressure, green innovation, and performance in small and medium-sized enterprises: the role of green dynamic capabilities. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022;31:500–514. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tariq A., Badir Y.F., Tariq W., Bhutta U.S. Drivers and consequences of green product and process innovation: a systematic review, conceptual framework, and future outlook. Technol. Soc. 2017;51:8–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu J., Wang K.-H., Su C.W., Umar M. Oil price, green innovation and institutional pressure: a China's perspective. Resour. Pol. 2022;78 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu C., Zhou K.Z., Xiao Y., Gao S. How green management influences product innovation in China: the role of institutional benefits. J. Bus. Ethics. 2016;133:471–485. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tariq A., Badir Y.F., Safdar U., Tariq W., Badar K. Linking firms' life cycle, capabilities, and green innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020;31:284–305. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chatterjee A., Hambrick D.C. It's all about me: narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007;52:351–386. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin H., Chen L., Yu M., Li C., Lampel J., Jiang W. Too little or too much of good things? The horizontal S-curve hypothesis of green business strategy on firm performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;172 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie X., Yu M., Zhai Y., Lin H. Explorative and exploitative innovation: a perspective on CEO humility, narcissism, and market dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 2022;147:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashmiri S., Nicol C.D., Arora S. Me, myself, and I: influence of CEO narcissism on firms' innovation strategy and the likelihood of product-harm crises. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2017;45:633–656. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Shammari M., Rasheed A., Al-Shammari H.A. CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility: does CEO narcissism affect CSR focus? J. Bus. Res. 2019;104:106–117. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marquez-Illescas G., Zebedee A.A., Zhou L. Hear me write: does CEO narcissism affect disclosure? J. Bus. Ethics. 2019;159:401–417. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chatterjee A., Hambrick D.C. Executive personality, capability cues, and risk taking: how narcissistic CEOs react to their successes and stumbles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2011;56:202–237. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin H., Sui Y., Ma H., Wang L., Zeng S. CEO narcissism, public concern, and megaproject social responsibility: moderated mediating examination. J. Manag. Eng. 2018;34 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrenko O.V., Aime F., Ridge J., Hill A. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2016;37:262–279. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong J., Lee J., Roh T. The effects of CEO narcissism on corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022;43:1926–1940. doi: 10.1002/mde.3500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albort-Morant G., Leal-Millán A., Cepeda-Carrión G. The antecedents of green innovation performance: a model of learning and capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69:4912–4917. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin H., Zeng S., Ma H., Chen H. How political connections affect corporate environmental performance: the mediating role of green subsidies. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2015;21:2192–2212. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engelen A., Neumann C., Schmidt S. Should entrepreneurially oriented firms have narcissistic CEOs? J. Manag. 2016;42:698–721. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resick C.J., Whitman D.S., Weingarden S.M., Hiller N.J. The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009;94:1365. doi: 10.1037/a0016238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinberg P.J., Asad S., Lijzenga G. Narcissistic CEOs ’ dilemma: the trade‐off between exploration and exploitation and the moderating role of performance feedback. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2022;39:773–796. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Villiers C., Naiker V., Van Staden C.J. The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. J. Manag. 2011;37:1636–1663. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu D., Fisher G., Chen G. CEO attributes and firm performance: a sequential mediation process model. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2018;12:789–816. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu D.H., Chen G. CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015;60:31–65. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wales W.J., Patel P.C., Lumpkin G.T. In pursuit of greatness: CEO narcissism, entrepreneurial orientation, and firm performance variance. J. Manag. Stud. 2013;50:1041–1069. doi: 10.1111/joms.12034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin H., Zeng S., Wang L., Zou H., Ma H. How does environmental irresponsibility impair corporate reputation? A multi-method investigation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016;23:413–423. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin H., Zeng S., Liu H., Li C. Bridging the gaps or fecklessness? A moderated mediating examination of intermediaries' effects on corporate innovation. Technovation. 2020;94 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mu J. Dynamic capability and firm performance: the role of marketing capability and operations capability. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2017;64:554–565. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J., Liang G., Feng T., Yuan C., Jiang W. Green innovation to respond to environmental regulation: how external knowledge adoption and green absorptive capacity matter? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020;29:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teece D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007;28:1319–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teece D.J., Pisano G., Shuen A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strat. Manag. J. 1997;18:509–533. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magistretti S., Ardito L., Messeni Petruzzelli A. Framing the microfoundations of design thinking as a dynamic capability for innovation: reconciling theory and practice. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2021;38:645–667. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilden R., Gudergan S.P. The impact of dynamic capabilities on operational marketing and technological capabilities: investigating the role of environmental turbulence. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015;43:181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakata C., Im S. Spurring cross-functional integration for higher new product performance: a group effectiveness perspective. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2010;27:554–571. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodríguez N.G., Pérez M.J.S., Gutiérrez J.A.T. Can a good organizational climate compensate for a lack of top management commitment to new product development? J. Bus. Res. 2008;61:118–131. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen C.A., Bozeman B. Organizational risk aversion: comparing the public and non-profit sectors. Publ. Manag. Rev. 2012;14:377–402. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu M., Lu Y., Li C., Lin H., Shapira P. More is less? The curvilinear effects of political ties on corporate innovation performance. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019;25:1309–1335. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.-Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003;88:879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danneels E. Organizational antecedents of second-order competences. Strat. Manag. J. 2008;29:519–543. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonidou C.N., Katsikeas C.S., Morgan N.A. “Greening” the marketing mix: do firms do it and does it pay off? J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2013;41:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sang L., Yu M., Lin H., Zhang Z., Jin R. Big data, technology capability and construction project quality: a cross-level investigation. Eng. Construct. Architect. Manag. 2021;28:706–727. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roh T., Seok J., Kim Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2022;67 doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim Y., Roh T. Preparing an exhibition in the post-pandemic era: evidence from an O2O-based exhibition of B2B firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2022;185 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hayes A.F. Guilford publications; 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dangelico R.M., Pujari D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics. 2010;95:471–486. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roh T., Noh J., Oh Y., Park K.-S. Structural relationships of a firm's green strategies for environmental performance: the roles of green supply chain management and green marketing innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;356 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roh T., Lee K., Yang J.Y. How do intellectual property rights and government support drive a firm's green innovation? The mediating role of open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;317 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee M.-J., Roh T. Digitalization capability and sustainable performance in emerging markets: mediating roles of in/out-bound open innovation and coopetition strategy. Manag. Decis. 2023 doi: 10.1108/MD-10-2022-1398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee M.-J., Roh T. Unpacking the sustainable performance in the business ecosystem: coopetition strategy, open innovation, and digitalization capability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023;412 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arici H.E., Uysal M. Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: a systematic review. Serv. Ind. J. 2022;42:280–320. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ren S., Wang Y., Hu Y., Yan J. CEO hometown identity and firm green innovation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021;30:756–774. [Google Scholar]

- 73.J. Wang, S. Han, L. Han, P. Wu, J. Yuan. New-type urbanization ecologically reshaping China, 9(2) Heliyon e12925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Chen L., Yuan M., Lin H., Han Y., You Y., Sun C. Organizational improvisation and corporate green innovation: a dynamic capability perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023 doi: 10.1002/bse.3443. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yuan M., Wang X., Lin H., Wu H., Yu M., Chen X. Crafting enviropreneurial marketing through green innovation: a natural resource-based view. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023 doi: 10.1109/TEM.2023.3237758. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.