Abstract

Background & Aims

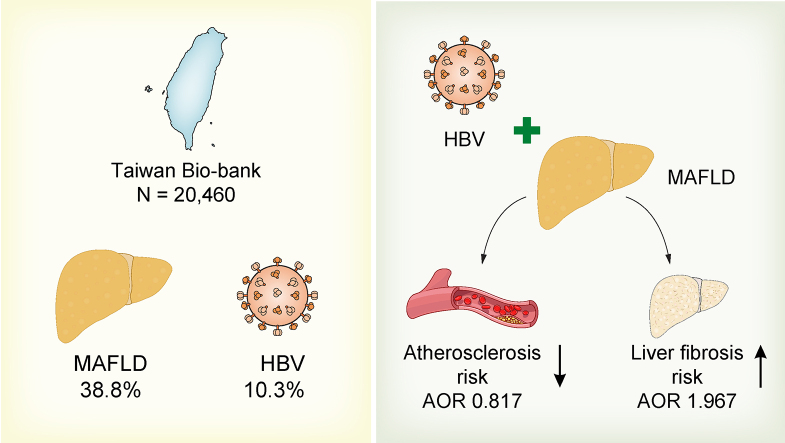

The new name and diagnostic criteria of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) was proposed in 2020. Although chronic HBV infection has protective effects on lipid profiles and hepatic steatosis, the impact of chronic HBV infection on clinical outcomes of MAFLD requires further investigation.

Methods

The participants from a Taiwan bio-bank cohort were included. MAFLD is defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis plus any of the following three conditions: overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and metabolic dysfunction. The patients with positive glycated haemoglobin were considered as having chronic HBV infection. Atherosclerosis was determined as having carotid plaques on duplex ultrasound. Advanced liver fibrosis was defined as Fibrosis-4 >2.67. Based on the status of MAFLD and HBV infection, the participants were distributed into four groups: ‘dual aetiology’, ‘MAFLD alone’, ‘HBV alone’, and ‘healthy controls’.

Results

A total of 20,460 participants (age 55.51 ± 10.37; males 32.67%) were included for final analysis. The prevalence of MAFLD and chronic HBV infections were 38.8% and 10.3%, respectively. According to univariate analysis, ‘HBV alone’ group had lower levels of glycated haemoglobin, lipid profiles, and intima media thickness than healthy controls. The ‘dual aetiology’ group had lower levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, γ-glutamyl transferase, intima media thickness, and percentage of carotid plaques than ‘MAFLD alone’ group. Using binary logistic regression, chronic HBV infection increased the overall risk of advanced liver fibrosis; and had a lower probability of carotid plaques in MAFLD patients, but not in those without MAFLD.

Conclusions

The large population-based study revealed chronic HBV infection increases the overall risk of liver fibrosis, but protects from atherosclerosis in patients with MAFLD.

Impact and implications

Patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease can also be coinfected with chronic HBV. Concomitant HBV infection increases the overall risk of liver fibrosis, but protects from atherosclerosis in patients with MAFLD.

Keywords: Hepatic B virus, Hepatic steatosis, Non-alcoholic liver disease, Metabolic associated fatty liver disease, Liver fibrosis, Atherosclerosis, Fatty liver index, Fibrosis-4 score, NAFLD fibrosis score, Intima media thickness, Carotid plaque

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Chronic HBV infection has protective effects on lipid profiles and hepatic steatosis.

-

•

We performed a large population-based study to uncover the relationship between HBV and atherosclerosis.

-

•

Chronic HBV infection increases the overall risk of liver fibrosis but protects from atherosclerosis in patients with MAFLD.

Introduction

Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is associated with metabolic syndrome and considered as the liver manifestation of metabolic syndrome.1,2 The prevalence of MAFLD increases in parallel with the endemics of obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). As nearly 1 billion people are affected by MAFLD worldwide, it produces a huge clinical and economic burden globally. Patients with MAFLD have an overall increase in mortality compared with the general population with the three main causes of death being cardiovascular disease, non-liver cancers, and liver-related diseases.3 However, an international survey revealed a major deficiency in patient referrals and patterns of practice including diagnosis, staging, and indication of liver biopsy.4 Chronic HBV infection induces liver-related complications and several extrahepatic manifestations including systemic vasculitides, glomerulonephritis, haematological malignancies, neurological diseases, and cutaneous manifestations.5 Because HBV infection is classified as other aetiologies of chronic liver diseases in the exclusive criteria of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), patients with HBV infection with hepatic steatosis are excluded from the diagnosis of NAFLD. The new disease name and diagnostic criteria of MAFLD was proposed in 2020 to replace the original term NAFLD.6,7 If patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) show hepatic steatosis in imaging or histology and also have metabolic dysfunction, MAFLD can be diagnosed simultaneously. Thus, patients with ‘concomitant HBV and MAFLD’ are a new disease group and their natural history and clinical outcomes deserve further investigation.

The liver plays an essential role in glucose and lipid metabolism. Patients with CHB infection had lower levels of lipid profiles compared with those without.8,9 Additionally, CHB infections were reported to protect from the development of hepatic steatosis.10,11 However, several published studies showed an inverse association between hepatic steatosis and HBV replication.[12], [13], [14] Moreover, the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma was reduced in patients with CHB with hepatic steatosis.15,16 However, the relationship between HBV infection and atherosclerosis remains inconclusive. Carotid duplex ultrasound can measure the intima media thickness (IMT) of carotid arteries and identify carotid plaques to assess the degree of atherosclerosis in clinical practice. Also, the degree of atherosclerosis reflects the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). With the advantage of the Taiwan bio-bank cohort, a representative sample of the Taiwanese general population with carotid duplex ultrasound data, a study was conducted to investigate the impact of co-existing CHB infection on the risk of advanced liver fibrosis and atherosclerosis in patients with MAFLD.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

The data were collected from the Taiwan bio-bank, a general population-based research database in Taiwan. The participants were enrolled through 43 recruitment stations since 2008. Until June 30, 2022, the number of participants increased to around 172,000. The methodologies of data collection from all participants are standardised procedures and have been described in previous studies.17,18 Briefly, after obtaining informed consent, a formal questionnaire including lifestyle factors and medical comorbidities was performed by an experienced nurse. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected. All participants were invited to receive follow up at an interval of 2–4 years. At the first follow up, they received additional examinations including abdominal ultrasound, bone density measurement, and carotid duplex ultrasounds. The liver ultrasonography was performed by three hepatologists with specialist qualifications. The images were stored, but the data were based on local readings. The grade of hepatic steatosis was reported in 95.4% (mild, 58.1%; moderate, 30.4%; severe, 6.9%) of patients with MAFLD.

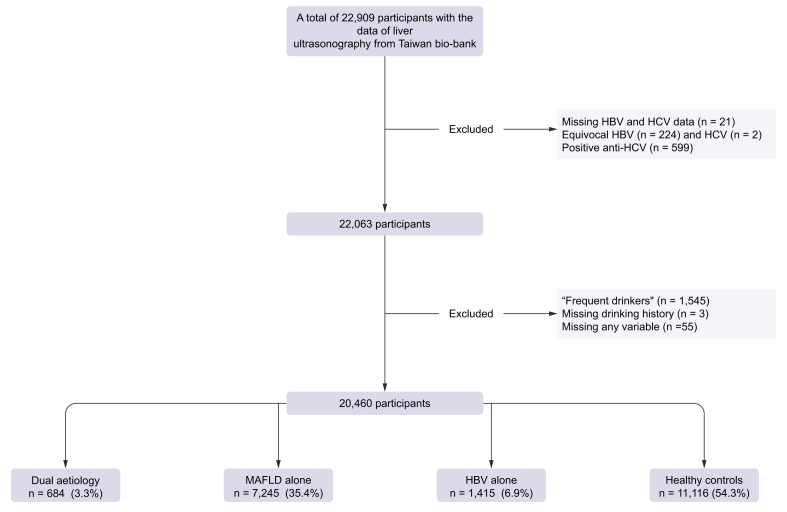

In the present study, participants with abdominal ultrasound data were recruited. The report of serum HBsAg being ‘±’ was considered equivocal HBV infection. Those with equivocal HBV infection, missing data including serum HBsAg, anti-hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV), record of alcohol consumption, or any required laboratory tests were excluded. Participants who reported to have persistent alcohol consumption for the past 3 months were considered as ‘frequent drinkers’. The alcohol consumption was categorised into three groups: teetotalers/social drinkers, ex-drinkers, or frequent drinkers. To avoid the confounding effects of alcohol and chronic HCV infection, ‘frequent drinkers’ or those who were positive for anti-HCV antibody were excluded (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of MAFLD was based on the evidence of hepatic steatosis on liver ultrasonography plus any of the following three criteria: overweight/obesity (BMI >23 kg/m2), DM, and at least two metabolic risk abnormalities in participants who were non-diabetic and lean/normal weight. DM is defined as having a history of DM or serum glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) >6.5%. Positive HBsAg defined CHB infection. The fatty liver index (FLI) was used to predict the grade of hepatic steatosis.19 Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) was calculated based on the formula: FIB-4 = age (years) × AST (U/L)/[PLT (109/L) × ALT1/2 (U/L)],20 where AST is aspartate aminotransferase, PLT is platelets, and ALT is alanine aminotransferase. Atherosclerosis is a condition in which fatty deposits, called plaques, build up within the arterial walls. IMT is a measurement of the thickness of the innermost layer and middle layer of the arterial wall. The increased IMT is associated with a higher risk of developing atherosclerosis. Carotid plaque is a manifestation of atherosclerosis, and is used as a marker for the presence and severity of atherosclerosis in arteries. The study assessed the clinical outcomes of MAFLD, including the risks of advanced liver fibrosis and atherosclerosis. Advanced liver fibrosis was defined as a FIB-4 score of greater than 2.67. The presence of carotid plaques on duplex ultrasound was used to diagnose atherosclerosis, and this served as a surrogate marker for the risk of ASCVD.21

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design.

MAFLD, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and approved with waived informed consent by the Research Ethics Committee of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital; Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (approval numbers: 10-XD-055 and 11-X-074) and the Ethics and Governance Council of the TWB (approval numbers: TWBR11102-03).

Statistical analyses

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data were analysed using the Χ2 test and Student t test. A value of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study participants were divided into four groups based on their HBV infection and MAFLD status: ‘dual aetiology’, ‘MAFLD alone’, ‘HBV alone’, or ‘healthy controls’. The study assessed two important clinical outcomes: the risks of advanced liver fibrosis and atherosclerosis. The exposure of interest was CHB infection. As the population we were most interested in was patients with MAFLD, the clinical characteristics and outcomes were compared between the ‘dual aetiology’ and ‘MAFLD alone’ groups. As the age and/or sex of the participants were unmatched between the two groups, propensity score (PS) matching was used to assess the impact of HBV infection on the risks of liver fibrosis and ASCVD in patients with MAFLD. We utilised PS matching to enhance comparability between the two groups by balancing the known confounders. The individual PSs were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model incorporating two covariates: age and sex. To perform the PS matching, patients with MAFLD alone were matched to patients with dual aetiology in a 1:1 nearest neighbour approach. The PS matching procedure was conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) without replacement in this study. After PS matching, the covariates were well balanced, as evidenced by a standardised mean difference of 0.00 for age and sex. The factors associated with advanced liver fibrosis or the presence of carotid plaques were analysed using binary logistic regression. The potential confounders included age, sex, DM, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia for the risk of ASCVD, and age, sex, γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and FLI for the risk of advanced liver fibrosis. Because the impact of HBV on atherosclerosis as well as the impact of MAFLD on the clinical outcomes of patients infected with CHB were unresolved clinical questions, they were analysed and answered at the same time.

Results

A total of 22,909 participants with liver ultrasonography data were enrolled from the Taiwan bio-bank database. After exclusions, a total of 20,460 participants (age 55.51 ± 10.37; males 32.67%) were included in the final analysis. The prevalence of MAFLD and CHB infection was 38.8% and 10.3%, respectively. The percentages of ‘dual aetiology’, ‘MAFLD alone’, ‘HBV alone’, and ‘healthy controls’ were 3.3%, 35.4%, 6.9%, and 54.3%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Comparison of clinical characteristics and metabolic profiles between the ‘HBV alone’ group and ‘healthy controls’

Compared with ‘healthy controls’, the ‘HBV alone’ group were younger, had a higher percentage of males, but lower frequencies of hypertension and dyslipidaemia histories. Furthermore, several metabolic factors including HbA1c, triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL were lower in the ‘HBV alone’ group than healthy controls (Table S1).

Liver and ASCVD risks between the ‘HBV alone’ group and ‘healthy controls’

The ‘HBV alone’ group had higher levels of ALT, AST, and FIB-4 index, but thinner IMTs than healthy controls (Table S1). Binary logistic regression found age, CHB infection, GGT, and FLI were factors associated with advanced liver fibrosis. Furthermore, age, male sex, hypertension, DM, and dyslipidaemia were factors associated with the presence of carotid plaques, but not CHB infection (Tables S2 and S3).

Comparison of clinical characteristics and metabolic profiles between ‘dual aetiology’ and ‘MAFLD alone’ groups

Compared with the ‘MAFLD only’ group, the ‘dual aetiology’ group were younger, and had a higher percentage of males, but lower frequencies of hypertension and dyslipidaemia histories. Furthermore, they had lower levels of TG, and total cholesterol. The percentage of DM, BMI, fasting glucose, HbA1c, HDL, LDL, and uric acid were comparable between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison between the ‘Dual aetiology’ and the ‘MAFLD alone’ groups (n = 7,929).

| MAFLD alone |

Dual aetiology |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 7,245 | n = 684 | ||

| Age, years | 56.40 ± 10.08 | 53.87 ± 9.69 | <0.0001 |

| Male, n (%) | 2,916 (40.25) | 319 (46.64) | 0.0012 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 887 (12.24) | 75 (10.96) | 0.3278 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1,818 (25.09) | 138 (20.18) | 0.0043 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 1,220 (16.84) | 81 (11.84) | 0.0007 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.47 ± 3.60 | 26.75 ± 3.66 | 0.0540 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 103.49 ± 27.04 | 102.75 ± 27.11 | 0.4955 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.17 ± 1.03 | 6.13 ± 1.09 | 0.3429 |

| TG, mg/dl | 159.14 ± 122.09 | 143.94 ± 102.90 | 0.0003 |

| CHO, mg/dl | 199.80 ± 37.54 | 195.78 ± 38.92 | 0.0077 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 48.90 ± 11.07 | 48.57 ± 11.21 | 0.4473 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 125.24 ± 33.54 | 123.58 ± 33.63 | 0.2164 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.87 ± 1.40 | 5.90 ± 1.33 | 0.6222 |

| AST, U/L | 27.03 ± 14.74 | 29.04 ± 13.89 | 0.0004 |

| ALT, U/L | 30.28 ± 26.65 | 34.43 ± 26.99 | <0.0001 |

| GGT, U/L | 28.78 ± 28.82 | 25.23 ± 17.44 | <0.0001 |

| Fatty liver index | 42.44 ± 24.44 | 40.88 ± 23.90 | 0.1090 |

| FIB-4 | 1.31 ± 0.67 | 1.35 ± 0.68 | 0.1111 |

| NFS | -1.76 ± 1.28 | -1.73 ± 1.21 | 0.5114 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.75 ± 0.24 | 0.77 ± 0.53 | 0.2299 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.732 | 103.48 ± 24.78 | 104.64 ± 23.72 | 0.2392 |

| IMT, mm | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 0.0003 |

| Carotid plaque, n (%) | 2,556 (35.28) | 184 (26.90) | <0.0001 |

Level of significance: p <0.05 (Χ2 and Student t tests).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CHO, cholesterol; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HTN, hypertension; IMT, intima media thickness; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score; TG, triglycerides.

Liver and ASCVD risks between ‘dual aetiology’ and ‘MAFLD alone’ groups

The ‘dual aetiology’ group had higher levels of AST, ALT, but lower levels of GGT, thinner IMTs and lower percentages of carotid plaque than patients in the ‘MAFLD alone’ group. However, as these two groups were unmatched in age and sex, there was no difference in the FIB-4 score and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) between the two groups in Table 2. By using PS matching for age and sex, the scores of FIB-4 and NFS were significantly higher in the ‘dual aetiology’ group as compared with the ‘MAFLD only’ group (Table 2). Furthermore, binary logistic regression found age, CHB infection, GGT, and FLI were factors associated with advanced liver fibrosis (Table 3). In addition, age, male sex, DM and history of hypertension were positively associated with the presence of carotid plaques; however, HBV infection had an inverse association (Table 4).

Table 2.

Comparison between the ‘dual aetiology’ and the ‘MAFLD alone’ group using propensity score matching for age and sex.

| MAFLD alone |

Dual aetiology |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 684 | n = 684 | ||

| Age, years | 53.87 ± 9.69 | 53.87 ± 9.69 | 0.9978 |

| Male, n (%) | 319 (46.64) | 319 (46.64) | >0.999 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 81 (11.84) | 75 (10.96) | 0.6098 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 157 (22.95) | 138 (20.18) | 0.2116 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 101 (14.77) | 81 (11.84) | 0.1113 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.70 ± 3.94 | 26.75 ± 3.66 | 0.7963 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 102.17 ± 22.84 | 102.75 ± 27.11 | 0.6647 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.10 ± 0.88 | 6.13 ± 1.09 | 0.5257 |

| TG, mg/dl | 161.57 ± 102.53 | 143.94 ± 102.90 | 0.0015 |

| CHO, mg/dl | 198.50 ± 35.90 | 195.78 ± 38.92 | 0.1790 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 48.37 ± 10.96 | 48.57 ± 11.21 | 0.7365 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 124.45 ± 31.99 | 123.58 ± 33.63 | 0.6224 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.95 ± 1.42 | 5.90 ± 1.33 | 0.4878 |

| AST, U/L | 26.94 ± 14.56 | 29.04 ± 13.89 | 0.0065 |

| ALT, U/L | 31.29 ± 35.07 | 34.43 ± 26.99 | 0.0635 |

| GGT, U/L | 29.06 ± 25.67 | 25.23 ± 17.44 | 0.0013 |

| Fatty liver index | 43.82 ± 25.77 | 40.88 ± 23.90 | 0.0289 |

| FIB-4 | 1.20 ± 0.53 | 1.35 ± 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| NFS | -1.91 ± 1.25 | -1.73 ± 1.21 | 0.0070 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.76 ± 0.21 | 0.77 ± 0.53 | 0.5456 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.732 | 103.75 ± 23.93 | 104.64 ± 23.72 | 0.4920 |

| IMT, mm | 0.63 ± 0.13 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 0.4807 |

| Carotid plaque, n (%) | 226 (33.04) | 184 (26.90) | 0.0132 |

Level of significance: p <0.05 (Χ2 and Student t tests).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CHO, cholesterol; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HTN, hypertension; IMT, intima media thickness; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score; TG, triglycerides.

Table 3.

Factors associated with biomarkers of advanced liver fibrosis in patients with MAFLD (n = 7,929).

| FIB-4 > 2.67 | AOR | (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.151 | (1.127–1.175) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 1.017 | (0.776–1.332) | 0.9049 |

| HBV | 1.967 | (1.288–3.003) | 0.0017 |

| GGT, U/L | 1.003 | (1.000–1.006) | 0.0314 |

| FLI | 1.007 | (1.001–1.013) | 0.0195 |

Level of significance: p <0.05 (binary logistic regression).

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; FLI, fatty liver index; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; MAFLD, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score.

Table 4.

Factors associated with carotid plaques in patients with MAFLD (n = 7,929).

| AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.100 | (1.093–1.107) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 1.660 | (1.493–1.846) | <0.0001 |

| HBV | 0.817 | (0.674–0.991) | 0.0403 |

| DM | 1.577 | (1.352–1.838) | <0.0001 |

| HTN | 1.575 | (1.398–1.774) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1.107 | (0.965–1.271) | 0.1475 |

Level of significance: p <0.05 (binary logistic regression).

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MAFLD, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease.

The impact of MAFLD, DM, or obesity on the liver and ASCVD risks of patients with CHB infection

Age was comparable between the ‘dual aetiology’ and ‘HBV alone’ groups. However, the ‘dual aetiology’ group had a higher percentage of males than the ‘HBV alone’ group. The ‘dual aetiology’ group had a lower FIB-4 score than the ‘HBV alone’ group, but a higher NFS. The ‘dual aetiology’ group had a greater IMT than the ‘HBV alone’ group, but the percentages of carotid plaques were comparable between these two groups (Table 5). The results remained unchanged after using PS matching for age and sex (Table S4).

Table 5.

The comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes between those with MAFLD and those without in patients with chronic HBV infection (n = 2,099).

| HBV alone |

Dual aetiology |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,415 | n = 684 | ||

| Age, years | 54.19 ± 9.78 | 53.87 ± 9.69 | 0.4808 |

| Male, n (%) | 481 (33.99) | 319 (46.64) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 59 (4.17) | 75 (10.96) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 159 (11.24) | 138 (20.18) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 97 (6.86) | 81 (11.84) | 0.0001 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 58 (4.10) | 30 (4.39) | 0.7584 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.98 ± 3.05 | 26.75 ± 3.66 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 93.22 ± 16.85 | 102.75 ± 27.11 | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.68 ± 0.61 | 6.13 ± 1.09 | <0.0001 |

| TG, mg/dl | 90.92 ± 49.90 | 143.94 ± 102.90 | <0.0001 |

| CHO, mg/dl | 193.33 ± 34.83 | 195.78 ± 38.92 | 0.1627 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 58.22 ± 13.97 | 48.57 ± 11.21 | <0.0001 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 116.72 ± 29.95 | 123.58 ± 33.63 | <0.0001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.05 ± 1.26 | 5.90 ± 1.33 | <0.0001 |

| AST, U/L | 28.05 ± 17.29 | 29.04 ± 13.89 | 0.1629 |

| ALT, U/L | 26.73 ± 31.27 | 34.43 ± 26.99 | <0.0001 |

| GGT, U/L | 18.42 ± 25.93 | 25.23 ± 17.44 | <0.0001 |

| Fatty liver index | 15.35 ± 15.78 | 40.88 ± 23.90 | <0.0001 |

| FIB-4 | 1.60 ± 0.88 | 1.35 ± 0.68 | <0.0001 |

| NFS | -1.84 ± 1.17 | -1.73 ± 1.21 | 0.0413 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.74 ± 0.61 | 0.77 ± 0.53 | 0.1539 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.732 | 107.10 ± 24.84 | 104.64 ± 23.72 | 0.0310 |

| IMT, mm | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | <0.0001 |

| Carotid plaque, n (%) | 364 (25.72) | 184 (26.90) | 0.5653 |

Level of significance: p <0.05 (Χ2 and Student t tests).

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CHO, cholesterol; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; GGT, γ-glutamyl transferase; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HTN, hypertension; IMT, intima media thickness; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score; TG, triglycerides.

Discussion

The study included 20,460 participants and found that 3.3% had concomitant HBV and MAFLD. Using binary logistic regression analysis, researchers found that concomitant HBV infection was linked to a higher risk of advanced liver fibrosis in patients with MAFLD. These findings suggest that chronic HBV infection can worsen liver injury in people with MAFLD. Interestingly, the study also found that chronic HBV infection was inversely associated with carotid plaques in MAFLD patients, suggesting a protective effect against ASCVD. However, this protective effect was not observed in patients without MAFLD.

Chronic HBV infection can cause liver inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, or even hepatocellular carcinoma.22 With the increasing prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus, CHB patients with hepatic steatosis are becoming more common in clinical practice. However, the relationship between hepatic steatosis and chronic HBV infection is complex. Hepatic steatosis has been shown to suppress HBV viral replication, whereas CHB infection appears to have a protective effect on the occurrence of hepatic steatosis. A recent meta-analysis of 98 studies involving 48,472 patients with CHB infection found no significant association between hepatic steatosis and liver fibrosis progression.23 Our study showed contradictory results in the markers of liver fibrosis between the ‘dual aetiology’ and ‘HBV alone’ groups, suggesting that the impact of concomitant MAFLD on liver fibrosis in patients with CHB infection is inconclusive. Although hepatic steatosis itself can damage the liver, the liver injury caused by CHB infection may be reduced through the suppressive effect of hepatic steatosis on HBV replication in patients with CHB infection. Therefore, further investigation is needed to determine the impact of MAFLD on liver fibrosis in patients with CHB infection. In contrast, the ‘dual aetiology’ group had a higher risk of advanced liver fibrosis than the ‘MAFLD alone’ group. It is important to note that hepatic steatosis or NAFLD is not equal to the new nomenclature of MAFLD, which requires two essential criteria including hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysfunction.24 Therefore, the impact of concomitant HBV infection on the progression of liver diseases in patients with MAFLD has rarely been reported. This large, population-based study is the first to investigate the relationship between CHB infection and advanced liver fibrosis in patients with MAFLD, suggesting that concomitant HBV infection has a synergistic effect on liver injury in patients with MAFLD. As a result, a more aggressive anti-HBV therapeutic strategy may be necessary for patients with concomitant HBV and MAFLD in clinical practice.

Cardiovascular disease is the primary cause of mortality in patients with MAFLD, and the severity of atherosclerosis indicates the risk of ASCVD.25 However, the relationship between CHB infection, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis is not well understood. Moreover, the influence of concomitant CHB infection on the risk of ASCVD in patients with MAFLD patients has been poorly studied. In our large, population-based study, binary logistic regression analysis revealed an inverse association between CHB infection and the presence of carotid plaques in MAFLD patients, indicating that CHB infection may protect against the risk of ASCVD in patients with MAFLD. The protective effect of CHB infection may be attributable to its lipid-lowering effect. However, in patients with HBV without MAFLD, a population without metabolic dysfunction and at low risk of ASCVD, HBV infection did not have a protective effect on the risk of ASCVD. The discrepant results may be because of the modest protective effect of HBV infection on the risk of ASCVD, which was insufficient to reach statistical significance in this low-risk population.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, it is the first large, population-based study to investigate the impact of concomitant HBV infection on the risks of liver fibrosis and ASCVD in patients with MAFLD. Secondly, we simultaneously assessed the risks of liver fibrosis and ASCVD using biomarkers of liver fibrosis and data from carotid duplex ultrasound. Thirdly, we excluded participants with positive anti-HCV antibody or those who were frequent drinkers to avoid the confounding effects of HCV and alcohol on the risks of liver fibrosis and ASCVD. However, some limitations should also be addressed. Firstly, the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis based on ultrasonography may miss minor degrees of steatosis. Additionally, the FLI has a modest accuracy of 0.84 in detecting hepatic steatosis. Secondly, liver biopsy, which is invasive and not well suited for population-based studies, was not available for histology. Thirdly, as data on high-sensitivity C reactive protein and insulin resistance were not available, the prevalence of MAFLD may have been underestimated. Fourthly, the data on HBV genotype, viral load, and anti-HBV treatment were not available in the study population. Finally, although the PS modelling can estimate the causal effect of HBV on clinical outcomes, the definite causal effect cannot be confirmed in this cross-sectional study.

To summarise, our study found that ‘concomitant HBV and MAFLD’ patients accounted for 3.3% of our study population. This newly identified disease group with a dual aetiology increases the risk of advanced liver fibrosis but protects from the risk of ASCVD when compared with ‘MAFLD alone’ patients. In clinical practice, patients with CHB infection and MAFLD should be managed simultaneously, and similar surveillance and management as patients with ‘MAFLD alone’ should be provided, including lifestyle modifications, reduction of body weight, and treatment for comorbidities. Because of the synergistic effect of chronic HBV infection on liver injury of MAFLD, a more aggressive therapeutic strategy may be necessary in clinical practice. New direct-acting antivirals for HBV, such as entry inhibitors, capsid assembly modulators, drugs targeting cccDNA or HBV RNA, and HBsAg secretion inhibitors, deserve further investigation and development.26 Additionally, as the lipid-lowering effect of CHB infection may be reversed by successful viral suppression, monitoring of lipid profiles and adequate treatment are recommended during anti-HBV treatment.

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (TCRD-TPE-112-11) and the Taiwan Liver Disease Consortium, Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 109-2314-B-002-091-MY3).

Authors’ contributions

Data collection: YMC. Statistical analysis: THH. Concept, design, and writing of article: CCW. Article revision: JHK.

Data availability statement

We declare the data was available and approved by the Ethics and Governance Council of the TWB (approval numbers: TWBR11102-03).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr I-Shiang Tzeng for his contribution of the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100836.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Asrih M., Jornayvaz F.R. Metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: is insulin resistance the link? Mol Cel Endocrinol. 2015;418(Pt 1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brea A., Puzo J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunner K.T., Pedley A., Massaro J.M., Hoffmann U., Benjamin E.J., Long M.T. Increasing liver fat is associated with progression of cardiovascular risk factors. Liver Int. 2020;40:1339–1343. doi: 10.1111/liv.14472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratziu V., Anstee Q.M., Wong V.W., Schattenberg J.M., Bugianesi E., Augustin S., et al. An international survey on patterns of practice in NAFLD and expectations for therapies – the POP-NEXT project. Hepatology. 2022;76:1766–1777. doi: 10.1002/hep.32500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacoub P., Asselah T. Hepatitis b virus infection and extra-hepatic manifestations: a systemic disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:253–263. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eslam M., Sanyal A.J., George J., International Consensus Panel MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1999–2014.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eslam M., Newsome P.N., Sarin S.K., Anstee Q.M., Targher G., Romero-Gomez M., et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu C.S., Liu C.H., Wang C.C., Tseng T.C., Liu C.J., Chen C.L., et al. Impact of hepatitis B virus infection on metabolic profiles and modifying factors. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:e48–e57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su T.C., Lee Y.T., Cheng T.J., Chien H.P., Wang J.D. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and dyslipidemia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Y.L., Wang Y.J., Kao W.Y., Chen P.H., Huo T.I., Huang Y.H., et al. Inverse Association between hepatitis B virus infection and fatty liver disease: a large scale study in populations seeking for check-up. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong V.S., Wong G.H., Chu W.W., Chim A.M., Ong A., Yeung D.K., et al. Hepatitis B virus infection and fatty liver in the general population. J Hepatol. 2012;56:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q., Mu M., Chen H., Zhang G., Yang Y., Chu J., et al. Hepatocyte steatosis inhibits hepatitis B virus secretion via induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cel Biochem. 2022;477:2481–2491. doi: 10.1007/s11010-021-04143-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu D., Wang H., Wang H., Wang Y., Wan X., Yan W., et al. Nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis attenuates hepatitis B virus replication in an HBV-immunocompetent mouse model. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:438–446. doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang S.C., Kao J.H. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and chronic hepatitis B. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121:2148–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J., Yang H.I., Yeh M.L., Le M.H., Le A.K., Yeo Y.H., et al. Association between fatty liver and cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:294–302. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mak L.Y., Hui R.W., Fung J., Liu F., Wong D.K., Li B., et al. Reduced hepatic steatosis is associated with higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:901–911. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan C.T., Lin J.C., Lee C.H. Taiwan biobank: a project aiming to aid Taiwan’s transition into a biomedical island. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:235–246. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin J.C., Fan C.T., Liao C.C., Chen Y.S. Taiwan biobank: making cross-database convergence possible in the big data era. Gigascience. 2018;7:1–4. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedogni G., Bellentani S., Miglioli L., Masutti F., Passalacqua M., Castiglione A., et al. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C.C., Liu C.H., Lin C.L., Wang P.C., Tseng T.C., Lin H.H., et al. Fibrosis index based on four factors better predicts advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis than aspartate aminotransferase/platelet ratio index in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:923–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabłak-Ziembicka A., Przewłocki T. Clinical significance of carotid intima-media complex and carotid plaque assessment by ultrasound for the prediction of adverse cardiovascular events in primary and secondary care patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4628. doi: 10.3390/jcm10204628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin C.L., Kao J.H. Perspectives and control of hepatitis B virus infection in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang D., Chen C., Liu X., Huang C., Yan D., Zhang X., et al. Concurrence and impact of hepatic steatosis on chronic hepatitis B patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:1718. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng Y.M., Wang C.C., Kao J.H. Metabolic associated fatty liver disease better identifying patients at risk of liver and cardiovascular complications. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:350–356. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu G., Hom J., Li Y., Jiang B., Rodriguez F., Fleischmann D., et al. Carotid plaque imaging and the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10:1048–1067. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2020.03.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asselah T., Loureiro D., Boyer N., Mansouri A. Targets and future direct-acting antiviral approaches to achieve hepatitis B virus cure. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We declare the data was available and approved by the Ethics and Governance Council of the TWB (approval numbers: TWBR11102-03).