Abstract

Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) encodes a movement protein (MP) which forms tubules in vivo and mediates the translocation of virus particles through plasmodesmata. The relationship between CaMV MP structure and function, in isolation from the complete virus infection, was studied by using MP expression in insect cells. The study allowed the MP domains necessary for tubule formation to be identified and potential MP-MP interactions to be investigated by using double infections with recombinant baculoviruses. Two MP domains which interfered with the ability of the wild-type MP to form tubules were identified. These mutant domains appeared to act as competitive, rather than dominant negative, inhibitors.

The spread of plant viruses from cell to cell is mediated by virus-encoded proteins called movement proteins (MPs). The MPs of several virus genera and families contribute to this process by forming tubular structures that traverse plasmodesmata to provide a channel through which virus nucleocapsids can pass from cell to cell. These include MPs from the Caulimoviridae (11, 12, 16, 18), Badnaviridae (2), Comoviridae (9, 25, 26), Tospoviridae (21), and Nepoviridae (6, 19, 20, 28, 29), among other families. Despite the significance of these MPs for virus infection and pathogenesis, very little is understood about how the tubules are formed and how virus particles translocate through them. Since no MPs have been crystallized, our knowledge of the structural organization of MPs is limited to the information coming from sequence comparisons and structural predictions and from measurements of the effect of mutagenesis on MP function. In many cases, the defined function has not been more specific than the ability of the protein to mediate a spreading infection in susceptible plant tissue.

The Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) MP is encoded by open reading frame I (ORFI) of the CaMV genome (22) and has little sequence similarity with viruses outside of the Caulimoviridae. However, some structural similarity has been identified in the C-terminal regions of the CaMV and Cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV; Comoviridae) MPs (23). Mutational analysis based upon the ability of the MP to support a full CaMV infection and aided by epitope tagging (23) led us to suggest that the protein termini are exposed on the protein surface and may be presented on the outer (N) and inner (C) faces of the tubule. We also suggested that the conserved C terminus may be held out into the lumen of the tubule by a hypervariable spacer sequence upstream of the C terminus. Although no additional structural conservation with the other MPs has been identified, a centrally located RNA-binding domain in the CaMV MP has sequences in common with the badnavirus and tobamovirus MPs (24).

Further analysis of the tubule-forming MPs might be facilitated by their ability, when they are expressed in isolation from the infection, to form tubules in isolated cells. In this case, tubules form intracellularly at the cell plasma membrane, causing projections into the surrounding medium. For CaMV MP, these projections have readily been observed in insect cells following baculovirus expression (7) and, albeit at very low efficiency, in plant protoplasts (18). In all respects these tubules formed in insect and plant cells appear to be similar (7, 18). We have used baculovirus-mediated expression in insect cells as a model system to investigate possible interactions between MP molecules that may be associated with MPs’ self-aggregation into tubules. To achieve this, the minimal protein unit capable of forming tubules was defined by deletion analysis. Subsequently, a series of mutant proteins with 3-amino-acid (aa) deletions called scanning deletion mutants (SDMs) (generated previously [23]) were tested for their capacity to support or inhibit the formation of tubules when they were expressed in combination with the wild-type (WT) protein.

CaMV MP expression in insect cells.

WT and mutated versions of CaMV ORFI from strain CM1841 (4) were cloned into recombinant baculoviruses (called bvMP) by using the Gibco BRL Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system and standard molecular biological techniques. The CaMV MP containing the c-myc epitope tag within the C-proximal spacer region (SPmyc) had been shown to be fully functional in planta (23) and therefore functionally equivalent to WT MP. Since this MP could be distinguished from mutant MP by virtue of the c-myc tag, it was also used as the WT MP in single and combined (with mutant MP) infections of insect cells. The mutations introduced into CaMV ORFI were confirmed by sequencing. The maintenance and infection of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf:IPLB-Sf21) cells and the assessment of baculovirus titers were according to standard baculovirus protocols (10). For the immunofluorescent identification of bvMP-infected cells and of MP tubule formation, 0.5 × 106 Sf21 cells were grown on glass slides and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of >5, unless otherwise indicated. The MP was detected with CaMV-MP rabbit polyclonal antiserum (1/500 dilution) (5) or c-myc monoclonal antibody (1/500; BabCo, Richmond, Calif.) and with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1/100; Sigma) or Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (1/1,000; Amersham), respectively, as second antibodies; assays were always carried out in duplicate. When WT baculovirus was used to infect Sf21 cells at a MOI of >5, more than 95% of cells became infected.

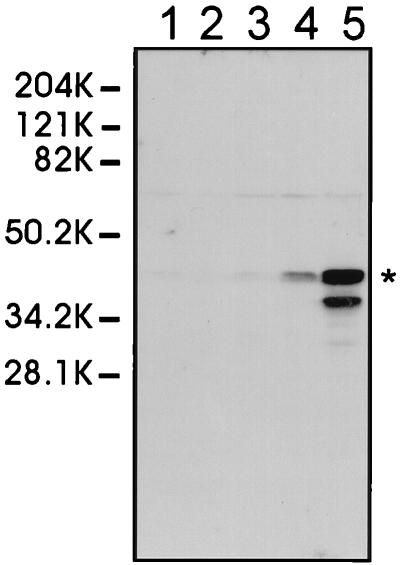

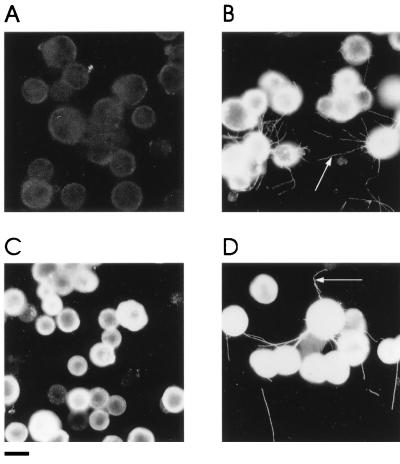

To assess the kinetics of protein accumulation (Fig. 1), 1.5 × 106 cells seeded in 35-mm-diameter petri dishes were infected at an MOI of >5 and incubated for various periods. After being washed to remove the fetal calf serum, the cells were lysed and the total proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (13) and immunoblotting (5) with the anti-MP serum (1/250) or anti-c-myc serum (1/500). MP was detected first at 24 h postinoculation (p.i.) and increased to a maximum at 72 h. However, by 72 h the insect cells had started to lyse and MP degradation was evident. All subsequent analyses were done at 48 h p.i. In parallel, cells were grown on glass slides and assessed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2). At 48 h p.i., MP had accumulated as cytoplasmic aggregates in all infected cells, a proportion (50 to 95%, dependent upon the experiment) of which showed the formation of thread-like surface structures (Fig. 2), shown previously (7) to be tubules. It was not clear why only some of the cells showed tubule formation. It may, however, be related to cell physiology, as the greatest variability in the number of cells showing tubule formation was between experiments; within an experiment, replicate samples gave reproducible results (±5%).

FIG. 1.

Time course of MP expression in Sf21 cells. Cell lysates from insect cells infected with bvFastBac (lane 1) or bvSPmyc (lanes 2 to 5) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE at 0 (lane 2), 24 (lane 3), 48 (lane 4), and 72 (lanes 1 and 5) h p.i., and the MP was detected by immunoblot analysis with polyclonal anti-MP serum. The sample in each lane is equivalent to 7.5 × 104 baculovirus-inoculated cells. The position of the MP is marked (*); CaMV MP has a molecular weight of 37,000 but shows anomalous migration by SDS-PAGE (17). The Mrs of protein size markers (in thousands [K]) are indicated.

FIG. 2.

MP tubule formation in Sf21 cells. Insect cells harvested 48 h after infection with bvFastBac (A) or baculovirus WT MP (B) were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-MP polyclonal serum. Expression of the WT MP was characterized by the appearance of fluorescent threads (arrows) extending from the surfaces of a proportion of the cells. MP mutants expressed in Sf21 cells could be classified as those that did not (e.g., the MP with aa 2 to 24 deleted [C]) or those that did (e.g., the MP with aa 282 to 303 deleted [D]) form tubules. Bar = 20 μm.

Functional domains for tubule formation.

A property of the CaMV MP is to form tubules that can provide a conduit for the translocation of virus particles from cell to cell, although a further property, RNA-binding activity (24), must also be important at some stage in the infection of plants. Our earlier experiments (23) had shown that, with the exception of minor alterations in the N-proximal and spacer regions, mutations in other parts of the MP abolished functionality during natural infections in plants. To assess the relationship between the complete function of the MP during infection and one specific function (i.e., tubule formation), various large deletion mutants and the SDMs were expressed in Sf21 cells and assessed for their ability to form tubules (Fig. 2). The large deletions focused on the N- and C-terminal regions that, in previous experiments, tolerated some small changes without virus movement being affected. Deletion 1 (aa 2 to 24) covered part of the region that tolerated the SDMs and the replacement of aa 6 to 15 with the c-myc epitope tag. This deletion abolished CaMV movement in planta and abolished tubule formation in Sf21 cells (Table 1). Deletion 2 (aa 282 to 303) removed the spacer region that separated the conserved C terminus from the central core of the protein (23). This deletion abolished CaMV movement in planta but did not affect tubule formation in Sf21 cells (Table 1). Deletion 3 (aa 292 to 327) removed the conserved C-terminal region and part of the spacer region. This deletion also did not prevent tubule formation in Sf21 cells (Table 1). Substitution of amino acids 6 to 15 (Nmyc) or 289 to 299 (SPmyc) with the c-myc tag had no effect on tubule formation in insect cells (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mutational analysis to define the minimal MP domain required for tubule formation

To assess the contribution that tubule formation might have made to the SDM phenotype in plants, all 26 mutant MP genes were expressed in Sf21 cells and assayed at 48 h p.i. by immunofluorescence. With one exception (the SDM in which aa 314 to 316 were deleted [SDM 314–316]), the ability to form tubules paralleled the ability of the mutants to support CaMV movement in planta (Table 2). For SDM 314–316, tubule formation in Sf21 cells was as abundant as that for the WT MP, although virus movement was abolished.

TABLE 2.

Effect of SDMs on the tubule-forming properties of the CaMV MP

| Deletion (aa) | Deleted amino acid sequence | Infectivitya | Formation of tubules in Sf21 cells | Formation of tubules in double infections of SF21 cells when the ratio of WT to mutant was

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10:1 | 1:1 | ||||

| 8–10 | NTQ | + | + | NTb | NT |

| 22–24 | QIF | + | + | NT | NT |

| 35–37 | DLM | + | + | NT | NT |

| 43–45 | LKN | − | − | + | + |

| 58–60 | IFK | − | − | + | + |

| 66–68 | SQV | − | − | + | + |

| 70–72 | KKA | − | − | + | + |

| 85–87 | TKE | − | − | + | + |

| 101–103 | LPL | − | − | + | + |

| 110–112 | NKR | − | − | + | + |

| 114–116 | SSL | − | − | + | + |

| 128–130 | HLG | − | − | − | + |

| 139–141 | QFR | − | − | − | + |

| 153–155 | IDD | − | − | + | + |

| 164–166 | LLG | − | − | + | + |

| 177–179 | FMF | − | − | + | + |

| 190–192 | NTQ | − | − | + | + |

| 206–208 | NKN | − | − | + | + |

| 219–221 | ITY | − | − | + | + |

| 234–236 | IDY | − | − | + | + |

| 248–250 | FQE | − | − | − | + |

| 262–264 | IQN | − | − | − | + |

| 275–277 | QNK | − | − | − | + |

| 288–290 | IGN | + | + | + | + |

| 301–303 | SNT | + | + | + | + |

| 314–316 | IDL | − | + | + | + |

Data are from reference 23.

NT, not tested.

These data largely mirrored the infectivity data from plant infection experiments (23) and emphasized the importance of tubule formation in aiding virus movement. The exceptions were MPs altered in the C-terminal region that could not aid virus movement in vivo but that were still able to form tubules in insect cells. We proposed previously that the N and C termini of the CaMV MP were not embedded in its three-dimensional structure and that the C terminus could project into the lumen of the tubule. Experiments with CPMV (14) supported the view that this region may be involved in the interaction with virus particles. The SDMs with deletions in the N terminus did not prevent tubule formation or virus movement, although deletion of the encompassing region inhibited both functions, indicating that although this region is surface located, it is integral to the structure required for tubule formation. Hence, in summary, we can say that the majority (aa 1 to 282) of the protein is required for tubule formation.

MP-MP interactions in tubule formation.

Purification of tubules formed by the homologous protein from CPMV (8) suggested that there are no host proteins in the tubule structure. From this, and the absence of any requirement for other viral proteins to be involved in tubule formation in insect cells, the CaMV MP tubules may similarly represent the physical self-association of the MP into higher-order aggregates. If this is so, then a physical interaction between adjacent MPs must occur and it might be possible to interrupt this process by colocating WT and mutant MP in the same cell. We were able to test this theory for the CaMV MP because expression of multiple recombinant proteins in insect cells can be achieved by coinfection with different baculoviruses (see, e.g., reference 3). Attempts to use the yeast two-hybrid system as an alternative approach were not fruitful (unpublished data).

We predicted that the coexpression of WT MP and a mutant MP unable to form tubules would either have no qualitative effect or lead to a blockage of tubule formation. The second option might arise either through a competitive inhibition of the interaction of the MP with a cellular component or through a dominant inhibition of function classically associated with the formation of ordered protein aggregates, where the mutant protein blocks the aggregation process. In an extending aggregate, the latter possibility might occur if the mutation exists on the outward face of the MP subunit such that it might prevent interaction with the next MP molecule. The distinction between the two possibilities might be blurred if the aggregation depends upon the addition of new molecules as part of an equilibrium reaction between the aggregated and nonaggregated states.

The complexity of the coexpression strategy dictated that some key features be built into the experimental design. First, only a qualitative assay (presence or absence of tubules) was employed and the infections were repeated for at least two independent experiments; the data were completely reproducible between experiments. Second, to determine the maximum potential for tubule formation in each experiment, control infections were carried out with mutant or WT recombinant baculoviruses at an MOI equivalent to that of the total baculovirus inoculum, and a >95% efficiency of infection was confirmed in each case. Since there was the possibility for WT MP expression to be reduced in the presence of other coinfecting baculoviruses, the minimum potential for tubule formation, or baseline control, for each experiment was established by coinfecting insect cells with WT baculovirus and bvFastBac (baculovirus with an empty expression cassette). Third, the baculovirus SPmyc (bvSPmyc) was used as the source of WT MP to allow its location to be distinguished from that of the mutant MP; all the mutant MPs lacked the c-myc tag. Hence, to assess the presence of WT and mutant proteins, immunofluorescence assays and immunoblot analyses were carried out with anti-MP and anti-c-myc sera for each infection. With the double infections, if there were any cells expressing WT but not mutant MP, we expected them to show tubule formation (a positive response in the qualitative assay). Cells expressing mutant but not WT protein would fail show tubule formation (Table 2; Fig. 2C). The assay was assisted by the use of two different fluorochromes. Hence, we could confirm that cell populations which did not show tubule formation and had a positive polyclonal response (detecting all MPs) also had an abundant anti-myc response (WT protein). In practice, for the double infections, only cells that showed a positive polyclonal and anti-myc response were scored for tubule formation. This meant that we identified only cells with blocked tubule formation if they also contained WT protein (i.e., a negative response in the qualitative assay). Last, to differentiate between competitive and dominant negative mutants, MOI ratios of 1:1 and 1:10 (WT to mutant, where the actual MOI was >10) were used for each mutant.

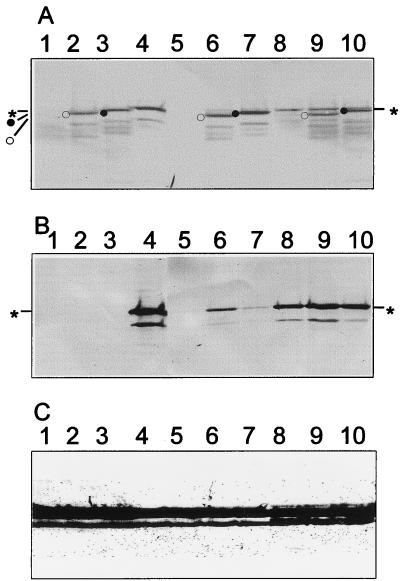

The number of MP tubules formed was less when bvSPmyc was coinoculated with bvFastBac (MOI ratio, 1:10) than when cells were infected with bvSPmyc alone (MOI, >10). Immunoblot analysis showed that this reduction correlated with a parallel and dramatic reduction in MP accumulation (Fig. 3, compare lanes 4 and 5), and the same was true when bvSPmyc was coinoculated with the SDM baculoviruses (Fig. 3, compare lanes 4 with lanes 6 and 7). This probably reflected a dilution of bvSPmyc replication and expression within the maximum limits of baculovirus replication in the insect cell population.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of MP accumulation following double infection of insect cells. Insect cells were infected with bvFastBac (lanes 1), baculovirus SDM 248–250 (lanes 2), baculovirus SDM 234–236 (lanes 3), or bvSPmyc (lanes 4) or with bvSPmyc in combination with bvFastBac (lanes 5 and 8), bvSPmyc in combination with baculovirus SDM 248–250 (lanes 6 and 9), or bvSPmyc in combination with baculovirus SDM 234–236 (lanes 7 and 10) at a ratio of bvSPmyc to SDM or bvFastBac of 1:1 (lanes 8 to 10) or 1:10 (lanes 5 to 7). Separated proteins were blotted and probed with polyclonal anti-MP serum (A), monoclonal anti-c-myc serum (B), or polyclonal anti-P10 serum (27) (C). The P10 protein is expressed as part of the baculovirus multiplication cycle and serves as an internal control for protein loadings. The positions of WT MP (asterisks), SDM 234–236 (filled circle), and SDM 248–250 (open circle) are marked.

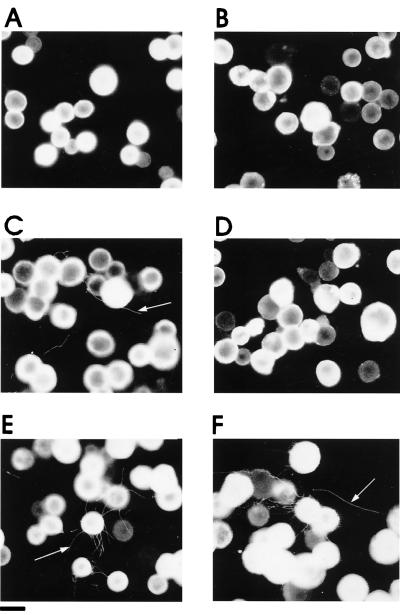

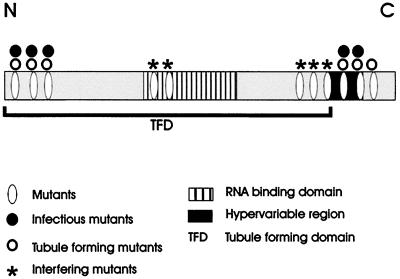

When coinfections with WT and SDM mutants were carried out at an MOI ratio of 1:10, two phenotypes were observed (Fig. 4). The majority of the SDMs had no effect upon tubule formation by bvSPmyc. However, five SDMs reproducibly blocked tubule formation in trans. The interfering mutants were clustered in two locations (Table 2; Fig. 5). The two mutants between aa 128 and 141 lay within the highly conserved RNA-binding domain, and three were located between aa 248 and 277 at the C-terminal extremity of the tubule-forming domain (Fig. 5). To see if the change in phenotype was correlated with change in protein accumulation, total protein extracts from insect cells harvested 48 h after inoculation were subjected to immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3). Anti-CaMV serum was used to assess total MP accumulation, and anti-c-myc monoclonal antibody was used to assess WT MP accumulation in the presence of interfering and noninterfering mutant MPs. The relative levels of WT and mutant MP accumulation could be determined since the SDMs caused a small but measurable change from the anomalous migration shown by the WT MP in SDS-PAGE (17). In the examples shown in Fig. 3, WT MP migrates with an Mr of 46,000 while SDM 234–236 (noninterfering; lane 3) and SDM 248–250 (interfering; lane 2) migrate with Mrs of 45,000 and 44,000, respectively. No significant differences in the relative levels of accumulation of the WT and mutants were found for any of the combinations coinoculated at a ratio of 1:10.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of double-infection experiments. Insect cells were infected with baculovirus SDMs that did not (A, C, and E) (e.g., SDM 43–45 [illustrated]) or did (B, D, and F) (e.g., SDM 128–130 [illustrated]) interfere with MP tubule formation. The cells were infected with baculovirus SDM alone (A and B) or in combination with WT baculovirus MP (C to F) in the WT-to-SDM ratio of 1:10 (C and D) or 1:1 (E and F) and screened for the presence of tubules (arrows) by immunofluorescence microscopy. The presence of the higher relative concentration of WT MP (F) overcame the inhibitory effect of the mutant MP. Bar = 20 μm.

FIG. 5.

Schematic diagram showing functional and structural domains within CaMV MP. The structural and functional features (listed) of the MP (shaded bar) are illustrated relative to those of the C and N termini of the protein.

The abolition of tubule formation (in the qualitative assay) argues for a dominant negative effect of these mutants. To assess the nature of the interference in tubule formation, the ratio of WT to mutant MP was changed by altering the MOI ratio. When the MOI ratio of bvSPmyc to bvSDM was changed from 1:10 to 1:1, the five interfering mutants no longer blocked tubule formation (Fig. 4 and Table 2). This altered ratio increased the amount of WT MP relative to that of mutant MP (Fig. 3, compare lanes 6 and 7 with lanes 9 and 10). The altered MOI ratio did not result in a significant change in total MP expression but did result in an increase in the proportion of WT to mutant protein (Fig. 3A and B). This loss of the inhibitory effect suggests a more complicated mechanism. One interpretation is that the two proteins compete for the same cellular factor necessary for tubule formation.

A major goal in studies of plant viruses is to identify sources of novel resistance to virus replication and/or spread. Success has frequently been achieved by others in an empirical fashion where transgenic expression of WT or mutant proteins leads to resistance to challenge infection (reviewed in references 1 and 15). One potential outcome of the more systematic study of structure-function relationships we have undertaken is that transgenic expression of the interfering mutants may lead to an inhibition of WT MP function. The phenotypic difference we observed when the ratio of WT to mutant changed from 1:10 to 1:1 suggests that the relative concentration in the plant is important. In a plant constitutively expressing the mutant protein, the effective ratio may be achieved at the front of virus invasion when the relative concentration of mutant protein is high.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miguel Aranda, Stuart Harrison, and Jeff Davies for comments on the manuscript prior to submission.

The John Innes Centre receives a grant-in-aid from the Biotechnology and Biological Scinces Research Council. The work was carried out under the United Kingdom Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food Licence PHL 11A/2650(6/1998).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baulcombe D C. Mechanisms of pathogen-derived resistance to viruses in transgenic plants. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1833–1844. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng C P, Tzafrir I, Lockhart B E, Olszewski N E. Tubules containing virions are present in plant tissue infected with Commelina yellow mottle badnavirus. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:925–929. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodson M S, Crute J J, Bruckner R C, Lehman I R. Overexpression and assembly of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase in insect cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20835–20838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner R C, Howarth A J, Hahn P, Brown-Luedi M, Shepherd R J, Messing J. The complete nucleotide sequence of an infectious clone of cauliflower mosaic virus by M13mp7 shotgun sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2871–2888. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.12.2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harker C L, Mullineaux P M, Bryant J A, Maule A J. Detection of CaMV gene I and gene VI protein products in vivo using antisera raised to COOH-terminal β-galactosidase proteins. Plant Mol Biol. 1987;8:275–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00015035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones A T, Kinninmonth A M, Roberts I M. Ultrastructural changes in differentiated leaf cells infected with cherry leaf roll virus. J Gen Virol. 1973;18:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasteel D T J, Perbal M-C, Boyer J-C, Wellink J, Goldbach R W, Maule A J, van Lent J W M. The movement proteins of cowpea mosaic virus and cauliflower mosaic virus induce tubular structures in plant and insect cells. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2857–2864. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasteel D T J, Wellink J, Goldbach R W, van Lent J W M. Isolation and characterization of tubular structures of cowpea mosaic virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3167–3170. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K S, Fulton J P. Tubules with virus like particles in leaf cells infected with bean pod mottle virus. Virology. 1971;43:329–337. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King L A, Possee R D. The baculovirus expression system. A laboratory guide. London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitajima E W, Lauritis J A. Plant virions in plasmodesmata. Virology. 1969;37:681–685. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitajima E W, Lauritis J A, Swift H. Fine structure of zinnia leaf tissue infected with dahlia mosaic virus. Virology. 1969;39:240–249. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;277:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lekkerkerker A, Wellink J, Yuan P, van Lent J, Golbach R, van Kammen A. Distinct functional domains in the cowpea mosaic virus movement protein. J Virol. 1996;70:5658–5661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5658-5661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lomonossoff G P. Pathogen-derived resistance to plant viruses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1995;33:323–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.33.090195.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maule A J. Virus movement in infected plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1991;9:457–473. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maule A J, Usmany M, Wilson I G, Boudazin G, Vlak J M. Biophysical and biochemical properties of baculovirus-expressed CaMV P1 protein. Virus Genes. 1992;6:5–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01703753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perbal M-C, Thomas C L, Maule A J. Cauliflower mosaic virus gene I product (P1) forms tubular structures which extend from the surface of infected protoplasts. Virology. 1993;195:281–285. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritzenthaler C, Schmit A-C, Michler P, Stussi-Garaud C, Pinck L. Grapevine fanleaf nepovirus P38 putative movement protein is located on tubules in vivo. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts I M, Harrison B D. Inclusion bodies and tubular structures in Chenopodium amaranticolor plants infected with strawberry latent ringspot virus. J Gen Virol. 1970;7:47–54. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-7-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storms M M H, Kormelink R, Peters D, van Lent J W M, Goldbach R W. The nonstructural NSm protein of tomato spotted wilt virus induces tubular structures in plant and insect cells. Virology. 1995;214:485–493. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas C L, Perbal C, Maule A J. A mutation of cauliflower mosaic virus gene I interferes with virus movement but not virus replication. Virology. 1993;192:415–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas C L, Maule A J. Identification of structural domains within the cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein by scanning deletion mutagenesis and epitope tagging. Plant Cell. 1995;7:561–572. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas C L, Maule A J. Identification of the cauliflower mosaic virus movement protein RNA binding domain. Virology. 1995;206:1145–1149. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Scheer C, Groenewegen J. Structure in cells of Vigna unguiculata infected with cowpea mosaic virus. Virology. 1971;46:493–497. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Lent J, Wellink J, Goldbach R. Evidence for the involvement of the 58K and 48K proteins in the intercellular movement of cowpea mosaic virus. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanoers M M, Malarme D, Jore J M P, Vlak J M. Expression of Autographa-californica nuclear polyhedrosis-virus P10 gene—effect of polyhedron expression. Arch Virol. 1992;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01317134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walkey D G A, Webb M J W. Tubular inclusion bodies in plants infected with viruses of the NEPO type. J Gen Virol. 1970;7:159–166. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-7-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieczorek A, Sanfaçon H. Characterization and subcellular localisation of tomato ringspot nepovirus putative movement protein. Virology. 1993;194:734–742. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]