Abstract

Objective

There was no universally accepted classification system that describes LHBT lesions as a type of its' pathology in patients with shoulder pain. This study aimed to determine the correlation of anatomic variants of glenoid labrum attachment of long head of biceps tendon (LHBT) and to assess their association, if any, with its lesions in rotator cuff tear (RCT) patients.

Methods

All RCT patients from January 2016 to December 2019 were assessed arthroscopically to classify the LHBT labrum attachment according to its' anatomical location. A simplified classification was created to describe the LHBT as normal, tendinitis, subluxation or dislocation, partial tear and superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion beyond type II The RCT were classified as three types as partial, small to medium and large to massive. The correlation of variants of LHBT labral attachment with type of LHBT lesions in different RCT groups was evaluated.

Results

In total, 669 patients were included for evaluation. The attachment of the LHBT was entirely posterior in 23 shoulders (3.4%), posterior‐dominant in 81 shoulders (12.1%), and equal in 565 shoulders (84.4%). In equal distribution LHBT attachment group, age > 60 (odds ratio: 2.928, P < 0.001) and size of RCT (P < 0.001) were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions. In the analysis of all patients, comparing with the partial thickness rotator cuff tear (PTRCT), the odds ratio of small to medium RCT and large to massive RCT was 2.398 and 6.606 respectively. In addition, age > 60 (odds ratio: 2.854, P < 0.001) and size of RCT (P < 0.001) were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions. In posterior dominant group, size of RCT was a significant risk factor of LHBT lesions but not any others (P < 0.001). In entirely posterior group, no risk factor of LHBT lesions was found. It showed that the variation of LHBT attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesions in rotator cuff repaired patients (p = 0.075).

Conclusions

There are three types of LHBT labrum attachment in RCT patients on arthroscopic observation. 84.4% were equal distribution of LHBT attachment on glenoid labrum, followed by posterior‐dominant (12.1%) and entirely posterior type (3.4%) in present study. Although the variation of LHBT attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesion in rotator cuff repaired(RCR) patients, there were different risk factors among three LHBT labral attachment types. In RCR patients, age > 60 and RCT size were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions.

Keywords: Arthroscopic, Biceps, Labrum Attachment, Rotator Cuff

Although the variation of long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesion in rotator cuff tear patients, there were different risk factors among different LHBT labral attachment groups.

Introduction

The role of the long head of bicep tendon (LHBT) in producing shoulder pain has been widely accepted since 1948. 1 It may be the primary source or in conjunction with other pathologic entities such as rotator cuff tear (RCT) in shoulder pain. 2 There is no universally accepted classification system that describes LHBT lesions as a type of its' pathology in patients with shoulder pain. Chen et al. 3 once defined a classification system of LHBT lesions combined with RCT, which later modified into tendinitis, subluxation or dislocations, partial or complete tears and SLAP lesions. Although they included most types of LHBT lesions in their observation studies, they did not explain the difference on LHBT lesions in RCT patients.

The correlation between LHBT pathology and RCT had been investigated by many studies due to close relationship of these two structures. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 In 1972, Neer 2 reported that 95% of cases of biceps tendinitis are a result of RCT patients. In 1982 Neviaser et al. 9 reported the strong association between rotator cuff tears and abnormalities of the LHBT. In a study by Walch et al., 10 16% of the 445 RCT patients presented with associated biceps tendon dislocation or subluxation. It was deduced that RCT may produce more pressure and friction on the LHBT, resulting in the high risk for lesions of LHBT. But the exact mechanism of variant LHBT lesions in RCT patients yet to be determined and need further investigation. According to above mentioned studies, the anatomic variation of LHBT, especially its' labral attachment, may play an important role on LHBT lesions in RCT patients. 11 , 12 , 13

Traditionally, the LHBT is described as arising from the supraglenoid tubercle and the glenoid labrum. Vangsness et al. 14 first described the variability of the labral attachment of the LHBT based on studying 100 fresh frozen shoulders from cadavers of both genders, which aged from the third to the ninth decade. They classified the labral attachment of LHBT into four types: entirely posterior, posterior‐dominant, equal, and entirely anterior. 15 The study demonstrated the variability of the LHBT labral attachment, which made the authors consider these normal anatomical variations as an essential in evaluating labral pathology. Tuoheti et al., 16 later observed 101 grossly normal embalmed shoulders and assessed the labral attachment type of LHBT. They reported different percentages of LHBT labral attachment types, which included entirely‐posterior in 28 shoulders, posterior‐dominant in 56 shoulders, equal in 17 shoulders and none in an entirely anterior type. By histological examination, the authors mentioned that the labral attachment of LHBT was posterior regardless of its macroscopic appearance. 16 Gigis et al., 5 on the contrary, after 20 cadavers shoulder observation, stated that the LHBT forms part of the posterior glenoid labrum and is not attached to the supraglenoid tubercle. Despite the controversy, all those studies were performed on “general population” cadavers and did not make further investigation on the association of LHBT anatomic variation with concomitant pathology.

Although the anatomical variance appears to contribute to LHBT function and pathology in RCT patients, it is still unclear the correlation of LHBT anatomical variation with LHBT lesions and its clinical relevance. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the variants of LHBT glenoid labrum attachment and to assess the association, if any, with LHBT lesions in RCT patients.

Methods

Study Participants

This investigation was a prevalent arthroscopic observation aiming to determine the correlation of the variation of LHBT labral attachment and LHBT lesions in RCT patients. The inclusion criteria were: (i) consecutive arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) by one group of surgeons, which were followed for a 4‐year period from January 2016 to December 2019; (ii) patients who were diagnosed RCT with a chart review for rotator cuff tendon findings during clinical examinations, imaging studies (anteroposterior view of the shoulder in neutral, outlet view and axillary view and magnetic resonance imaging) and operations; and (iii) patients who did not experience any improvement or were dissatisfied with conservative treatment were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were: (i) patients with LHBT had already been torn completely due to previous injury which make the LHBT attachment cannot be evaluated were excluded; and (ii) patients combined with shoulder instability (Bankart lesion, glenoid fracture, posterior or multi‐instability), AC joint arthritis, greater tuberosity fractures, impingement syndrome without lesion to rotator cuff, un‐repairable RCT, isolated subscapularis tendon tear, patients received any previous shoulder surgery were also excluded. Patient's age at time of surgery, gender, hand dominance, etiology (trauma or non‐trauma) was recorded.

Arthroscopic Observation

All RCT patients underwent shoulder arthroscopy in the beach‐chair position. After standard diagnostic arthroscopy with assessment of all intra‐articular structures in the glenohumeral joint through the posterior portal, attention was given to the superior labrum and LHBT attachment. The labral attachment was assessed while the tendon superiorly was gently pulled with hook through the anterior portal. This was because, by pulling the biceps tendon superiorly, the junction between the biceps and the anterior superior labrum became clearly visible. The labral attachment of the biceps was classified into three types:1 (i) entirely posterior, if all the labral part of the LHBT attachment was to the posterior labrum with not any part anterior to 12 o'clock of the gleniod, 2 posterior‐dominant; (ii) if most of the LHBT labral attachment was to the posterior labrum but with partial distribution to the anterior labrum, 3 and (iii) equal if the labral attachment was equally distributed to posterior and anterior labrum. We defined the top of glenoid as 12 o'clock position to separate anterior and posterior glenoid labrum.

A simplified classification modified from the Habermayer‐Walch classification 6 was created to describe the pathologic lesion of the biceps tendons in our series, which consisted of normal tendon, tendinitis, subluxation or dislocation, partial tear and superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion beyond type II according to the scheme of Snyder et al. 17 If the tendon presented with combined lesions in tear, subluxation, or dislocation, the LHBT pathologic type was classified according to the major lesion. After that the anterior rotator interval was released regularly. The attention was then turned to the subacromial space. Acromioplasty or decompression was performed. Bursectomy was performed in all RCT cases to get better view. The LHBT attachment type was re‐evaluated with the scope through the anterior rotator interval from anterior‐lateral portal to avoid the visual orientation error (Figs 1, 2, 3).

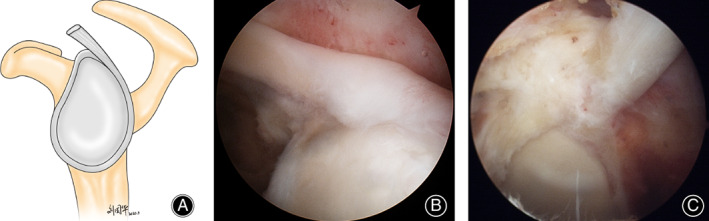

Fig. 1.

Entirely posterior type of LHBT labrum attachment of left shoulder: (A) diagram; (B) arthroscopic view with the camera through the posterior portal in glenoid humeral joint; (C). arthroscopic view with the camera through the anterior‐lateral portal in subarcromial space

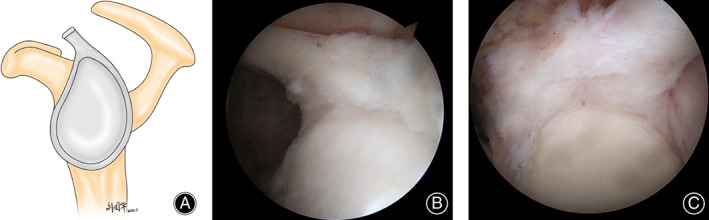

Fig. 2.

Posterior‐dominant type of LHBT labrum attachment of left shoulder: (A) diagram; (B) arthroscopic view with the camera through the posterior portal in glenoid humeral joint; (C) arthroscopic view with the camera through the anterior‐lateral portal in subarcromial space

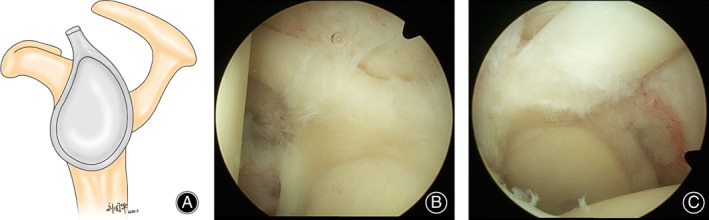

Fig. 3.

Equal type of LHBT labrum attachment of left shoulder: (A) diagram; (B) arthroscopic view with the camera through the posterior portal in glenoid humeral joint; (C) arthroscopic view with the camera through the anterior‐lateral portal in subarcromial space

The RCT was then confirmed and classified into 3 types: (i) partial tear (PTRCT); (ii) complete small to medium tear; and (iii) large to massive tear, which was defined as the dimension of tear by intraoperative measurement. The classification of LHBT lesions and RCT were determined by two examiners. When there was a difference of opinion between the two examiners, the classifications would be justified by another senior surgeon. Tenodesis or tenotomy of LHBT was performed if abnormal due to age and activity demand of the patients. The RCR was repaired with single row or suture bridge technique due to RCT patterns and surgeon's preference.

Statistical Analysis

The resulting data were analyzed to find the correlation of the variants of LHBT labrum attachment and LHBT lesions in different RCT patients. Also, the rates of abnormal LHBT were compared between age (≥60 years old and <60 years old), gender (male and female), evolved side (dominant and non‐dominant side) and etiology (trauma and no‐trauma) respectively among different LHBT labral attachment groups. The LHBT lesion in RCT patients was defined as tendonitis, subluxation or dislocation, partial tear and SLAP lesion. All measurements were performed using SPSS 19.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Reliability and reproducibility were assessed with use of kappa statistics. Intra‐observer reliability and inter‐observer reliability were assessed by two examiners. Both observed the LHBT labral attachment during the surgery and then re‐evaluated video documents 3 months postoperatively. A kappa value <0.00 indicates poor reliability; 0.00 to 0.20, slight reliability; 0.21 to 0.40, fair reliability; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate reliability; 0.61 to 0.80, substantial reliability; and 0.81 to 1.00, excellent agreement.

Based on a pilot study, setting the significance level to be 0.05, and ß = 0.80, the sample size should be over 133. A Spearman correlation test was used to determine the relationship between the distribution of LHBT lesion and LHBT lesion/RCT classification, and the correlation between RCT and LHBT lesion. The relationship between age, gender, evolved side, etiology, variation of LHBT origin, LHBT lesions and RCT pathologies was analyzed using multinomial logistic regression and ordinal logistic regression, respectively.

Results

Demographic Data

In total, 680 consecutive RCT patients were included in this study. Among all patients, 11 patients presented with absent LHBT were excluded. The correlation of types of LHBT labrum attachment, LHBT lesions and RCT severity were conducted on 669 patients. There were 254 male patients (38.0%) and 415 female patients (62.0%). The dominant side was affected in 427 patients (63.8%). The mean age of all participants was 56.1 ± 8.7 years. There were 129 patients (19.3%) diagnosed as PTRCT, 474 patients (70.8%) as small to medium RCT and 66 as large to massive RCT (9.9%). 364 abnormal LHBT were found, which account for 54.4% in all RCT patients (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of three type of LHBT labral attachment in RCR patients

| LHBT classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Type II | Type III | Total | |

| Age | ||||

| >60 years | 12 | 22 | 199 | 233 |

| ≤60 years | 11 | 59 | 366 | 436 |

| Sex | 0 | |||

| Male | 8 | 35 | 211 | 254 |

| Female | 15 | 46 | 354 | 415 |

| Effected side | 0 | |||

| Dominant | 13 | 55 | 359 | 427 |

| Non‐dominant | 10 | 26 | 206 | 242 |

| Etiology | 0 | |||

| Traumatic | 18 | 50 | 330 | 398 |

| Non‐traumatic | 5 | 31 | 235 | 271 |

Abbreviations: LHBT, long head of biceps tendon; RCR, rotator cuff repair.

In the present study, the average intra‐observer correlation kappa value was 0.92, and inter‐observer kappa value was 0.91 on evaluation of LHBT variation of attachment, which indicates excellent agreement. Besides, there was no discrepancy on observing LHBT labrum attachment from glenoid‐humeral joint and subacromial space.

Correlation between LHBT and RCT

The distribution of LHBT type on different lesions of LHBT and RCT classification was presented on Tables 2 and 3. The attachment of the LHBT was entirely posterior in 23 shoulders (3.4%), posterior‐dominant in 81 shoulders (12.1%), and equal distribution in 565 shoulders (84.4%). Both the distributions of lesions of LHBT and size of RCT were not significant different among different types of LHBT attachment groups (Χ 2 = 24.47, P = 0.055 in Table 2 and Χ 2 = 10.02, P = 0.109 in Table 3 respectively). There were 44 LHBT lesions in 129 PTRCT patients, 244 LHBT lesions in 474 small to medium RCT patients and 52 LHBT lesions in 66 large to massive RCT patients. The percentages of LHBT lesion in these three RCT groups were 34.1%, 51.5% and 78.8% respectively. The Spearman correlation test demonstrated significant positive correlation between RCT size and LHBT lesions (P < 0.05, coefficient = 0.228; Table 4).

TABLE 2.

The distribution of LHBT lesion in three types of LHBT labral attachment

| LHBT lesion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Tendinitis | Subluxation/dislocation | Partial tear | SLAP | Subtotal | |

| Type I | 4 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 23 |

| Type II | 37 | 21 | 5 | 15 | 3 | 81 |

| Type III | 264 | 187 | 22 | 84 | 8 | 565 |

| Subtotal | 305 | 219 | 29 | 105 | 11 | 669 |

Abbreviations: LHBT, long head of biceps tendon; SLAP, superior labral tear from anterior to posterior.

TABLE 3.

The distribution of RCT classification in three types of LHBT labral attachment

| PTRCT | Small‐medium RCT | Large‐massive RCT | Subtotal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 3 (2.3%) | 15 (3.2%) | 5 (7.6%) | 23 |

| Type II | 16 (12.4%) | 54 (11.4%) | 11 (16.7%) | 81 |

| Type III | 110 (85.3%) | 405 (85.4%) | 50 (75.8%) | 565 |

| Subtotal | 129 | 474 | 66 | 669 |

Abbreviations: LHBT, long head of biceps tendon; PTRCT, partial thickness rotator cuff tear; RCT, rotator cuff tear.

TABLE 4.

The distribution of LHBT lesions in three types of RCT

| Normal | Tendinitis | Subluxation/dislocation | Partial tear | SLAP | Subtotal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTRCT | 85 | 31 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 129 |

| Small‐medium RCT | 206 | 159 | 17 | 83 | 9 | 474 |

| Large‐massive RCT | 14 | 29 | 11 | 12 | 0 | 66 |

| Subtotal | 305 | 219 | 29 | 105 | 11 | 669 |

Abbreviations: LHBT, long head of biceps tendon; PTRCT, partial thickness rotator cuff tear; RCT, rotator cuff tear; SLAP, superior labral tear from anterior to posterior.

In the analysis of all patients, LHBT attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesions (P = 0.075). However, age > 60 (odds ratio: 2.854 (1.997–4.080), P < 0.001) and RCT size (P < 0.001) were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions. Comparing with the PTRCT, the odds ratio of small‐medium RCT was 2.492 (1.630–3.812), large‐massive RCT was 6.985 (3.367–14.488).

In equal distribution LHBT attachment group, the result of logistic regression showed that age > 60 (odds ratio: 2.928, P < 0.001) and size of RCT (P < 0.001) were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions. Comparing with the PTRCT, the odds ratio of small‐medium RCT was 2.398 (1.513–3.798), large‐massive RCT was 6.606 (2.927–14.913). In posterior dominant group, size of RCT was a significant risk factor of LHBT lesions but not any others (P < 0.001). In entirely posterior group, no risk factor of LHBT was found (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Multinomial logistic regression results of risk factors of LHBT lesions

| Wald | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 669) | |||

| Sex | 0.641 | 0.423 | – |

| Age > 60 years | 33.121 | <0.001 | 2.854 (1.991–4.080) |

| Affected side | 0.149 | 0.699 | – |

| Dominance | 0.876 | 0.349 | – |

| RCT lesion | 31.140 | <0.001 | – |

| Partial tear | – | – | – |

| Small‐medium | 17.749 | <0.001 | 2.492 (1.630–3.812) |

| Large‐massive | 27.263 | <0.001 | 6.985 (3.367–14.488) |

| Etiology | 3.240 | 0.072 | – |

| LHBT attachment | 5.184 | 0.075 | – |

| Type I (n = 23) | |||

| Sex | 0.25 | 0.992 | – |

| Age > 60 years | 0.013 | 0.911 | – |

| Affected side | 0.002 | 0.969 | – |

| Dominance | 0.016 | 0.930 | – |

| RCT lesion | 0.21 | 0.990 | – |

| Etiology | 0.000 | 0.999 | – |

| Type II (n = 81) | |||

| Sex | 3.589 | 0.058 | – |

| Age > 60 years | 3.782 | 0.052 | – |

| Affected side | 0.758 | 0.384 | – |

| Dominance | 0.620 | 0.431 | – |

| RCT lesion | 6.692 | 0.035 | |

| Partial tear | – | – | – |

| Small‐medium | 4.125 | 0.042 | 4.385 (1.053–18.257) |

| Large‐massive | 6.407 | 0.011 | 16.213 (1.875–140.174) |

| Etiology | 5.405 | 0.020 | 3.902 (1.238–12.294) |

| Type III (n = 565) | |||

| Sex | 0.073 | 0.787 | – |

| Age > 60 years | 30.065 | <0.001 | 2.928 (1.994–4.298) |

| Affected side | 1.602 | 0.206 | – |

| Dominance | 3.124 | 0.077 | – |

| RCT lesion | 23.980 | <0.001 | – |

| Partial tear | – | – | – |

| Small‐medium | 13.872 | <0.001 | 2.398 (1.513–3.798) |

| Large‐massive | 20.657 | <0.001 | 6.606 (2.927–14.913) |

| Traumatic | 0.895 | 0.344 | – |

Note: Type I, entirely posterior labral attachment; Type II, posterior dominant labral attachment; Type III, equal distribution labral attachment.

Discussion

The Variation of LHBT

The most important finding of this study was that the older age and RCT size were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions, although the variation of LHBT attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesion in rotator cuff repaired (RCR) patients.

The variations of the LHBT attachment on the superior glenoid labrum have been mentioned in anatomy research for several decades based on cadavers without the aforementioned clinical relevence. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 The distribution of the LHBT labral attachment has been classified into four types by Vangsness et al. 14 The percentages of these four types were entirely posterior (22%), posterior‐dominant (33%), equal (37%), and entirely anterior (8%) respectively in 100 cadaver shoulders observed, which mentioned that the attachment is primarily posterior most of the time, with fewer specimens showing contributions from the anterior labrum, and even anterior‐dominant tendon attachments had at least a small contribution to the posterior labrum. This classification was questioned by Tuoheti et al. 16 later, based upon observing 101 cadaveric shoulders. In that study, only three types were found, which entirely‐posterior in 28 shoulders (27.7%), posterior‐dominant in 56 shoulders (55.4%) and equal in 17 shoulders (16.8%). 16 In our series, we did not find any anterior‐dominant type of LHBT labrum distribution in RCT patients either. But the percentage of each group was mostly different: the attachment of the LHBT was entirely posterior in 23 shoulders (3.4%), posterior‐dominant in 81 shoulders (12.1%), and equal in 565 shoulders (84.4%). We think the explanations for this significant difference were as followed: first, it was relatively easier distinguishing the entirely posterior dominant type than the other two types because of its distinct arthroscopic appearance. Only those LHBT attachment without any part of structure located at the anterior labrum were classified as type one attachment group. We differentiated anterior and posterior labrum due to the locating the 12 o'clock position of the glenoid during the operation. However, classifying the posterior‐dominant and the equal types was relatively difficult and totally based on observers' experience to decide whether the anterior extension of the LHBT looked equal or less dominant compared with the posterior components. In order to improve our reproducibility, different observers assessed the glenoid labrum distribution of LHBT respectively and both of them evaluated it from different portals (posterior portal through the glenohumeral joint and anterolateral portal through subacromial space) in our study. Our results showed the inter‐observer kappa value and the intra‐observer reliability was 0.91 and 0.92 respectively. In Vangsness et al.’s study, 14 no inter‐or intra‐observer reliability was mentioned. In Tuoheti et al.'s study, 16 the intra‐observer reliability was 0.671 without inter‐observer value. By comparing these previous studies, it indicates that our study had substantial agreement and high consistency. Second, all patients in our study were Chinese people, where an ethnic difference may exist. Chen et al. 22 found 41% tendinitis and 12% partial tears of LHBT in their RCT patients in Taiwan China. Those were quite similar as our study performed among mainland Chinese people, with 45.5% tendinitis and 15.7% partial tears of LHBT in our series. Third, our study was only performed on RCT patients who needed surgery, which excluded those RCT patients receiving conservative treatment. Different patient's selection may play a role, which needs further investigation.

Another discrepancy is on the bifurcate origin of LHBT. The long head tendon has been described traditionally as originating of the supraglenoid tubercle. 23 Anatomic dissections and arthroscopic evaluations have also found a frequent incidence of attachment to the superior labrum. 24 , 25 In Vangsness et al.’s study, 14 they found that 40% to 60% of the LHB tendon originated at the supraglenoid tubercle, with the rest originating at the superior glenoid labrum. 14 Tuoheti et al. considered that all LHBT originated from both the glenoid labrum and supraglenoid tubercle due to histological examination. 16 But Pal et al. 26 found that the LHBT was attached to the supraglenoid tubercle in only 25% of his cases. Demondion et al. 27 found only 6.4% of LHBT origin from the supraglenoid tubercle among 31 cadavers' study. Gigis et al. 5 studied 40 shoulders and stated that the LHBT is not attached wholly to the supraglenoid tubercle. 6 In present study, we used the probe to pull the LHBT attachment with “peel off” force though the anterior portal in the glenoid‐humeral joint, which made LHBT attachment much clearer under tension. Then we repeated the procedure though the anterior lateral portal in the subacromial space. By this manipulation, we found all LHBT attachment originated from the glenoid labrum and none attached the glenoid tubercule directly, which was comparable with Gigis et al.'s study. But we also noted that arthroscopic assessment was not comparable with histological evaluation regardless of its arthroscopic appearance.

LHBT Labral Attachment and its' Lesions

Ghalayini once mentioned in his review that LHBT normal anatomic variations may help to explain the various patterns of LHBT injuries and need to be considered when arthroscopically assessing and treating patients. 28 However, in the present study, we did not find the anatomical variation of labral attachment is a risk factor on LHBT lesions in RCR patients (P = 0.075). Age > 60 and size of RCT were two risk factors in equal distribution type, which age > 60 is only factor in posterior dominant type. Although most of the RCT patients had LHBT lesions in the entirely posterior attachment type (82.6%) compared with posterior‐dominant type (54.3%) and equal distribution type (53.3%) in present study, the distributions of LHBT lesions were not significantly different among three types.

Neer considered the LHBT intimate anatomical relationship to the rotator cuff is the main reason of LHBT lesions occurs mostly in the presence of RCT. 2 In our study, there were 54.4% RCR patients had concomitant LHBT lesions (364 in 669 patients). Subgroup analysis showed the percentages of healthy LHBT in these three RCT groups were 65.4%, 43.2% and 21.2% respectively. It is obvious that the incidence of LHBT pathology is directly proportional to the extent of RCT, which consistent with previous literatures. 12 , 29 , 30 , 31

Limitations

Several limitations of this study influenced the findings and statistical associations. First, the classification of the LHBT labrum distribution and LHBT lesion is totally subjective, a discrepancy that may exist from different studies. Although the golden standard is pathology, to perform a histology exam is impossible in clinical practice. Second, there was an inherent selection bias since only RCR patients were evaluated. All patients with LHBT complete tear was also excluded from this study. We deduced that previous injury should be the main reason but none of these patients can recall the incidence accurately. Third, there were limited sample size in the type I group, which make the results of multinomial regression analysis less convincing. Further investigation with more patients in the type I group needs to performed before drawing any further conclusion.

Conclusion

There are three types of LHBT labrum attachment in RCT patients on arthroscopic observation; 84.4% were equal distribution of LHBT attachment on glenoid labrum, followed by posterior‐dominant (12.1%) and entirely posterior type (3.4%) in present study. Although the variation of LHBT attachment was not a significant risk factor of LHBT lesion in RCR patients, there were different risk factors among different LHBT labral attachment groups. In RCR patients, age > 60 and RCT size were significant risk factors of LHBT lesions.

Author Contributions

Yi Lu and Yue Li did the manuscript writing and submission. Hailong Zhang, Xu Li, Fenglong Li contributed to the article searching and synthesis. Chunyan Jiang designed the subject and supervised the whole process.

Conflict of Interest

All authors are without conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject of this manuscript.

Ethics Statement

The protocol for the research project has been approved by a suitably constituted Ethics Committee of Beijing Jishuitan Hospital within which the work was undertaken and that it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- 1. Hitchcock HH, Bechtol CO. Painful shoulder; observations on the role of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii in its causation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1948;2:263–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neer CSII. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;1:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen XT, Fang W, Jones IA et al. The efficacy of platelet‐rich plasma for improving pain and function in lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis with risk‐of‐bias assessment. Art Ther 2021, 9: 2937–2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker DA, Cofield RH. Tenodesis of the long head of the biceps brachii for chronic bicipital tendinitis. Long‐term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;3:376–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gigis P, Natsis C, Polyzonis M. New aspects on the topography of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle. One more stabilizer factor of the shoulder joint. Bull Assoc Anat (Nancy). 1995;245:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Habermeyer P, Walch G. The biceps tendon and rotator cuff disease. In: Burkhead WZ Jr, editor. Rotator cuff disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lafosse L, Reiland Y, Baier GP, Toussaint B, Jost B. Anterior and posterior instability of the long head of the biceps tendon in rotator cuff tears: a new classification based on arthroscopic observations. Art Ther. 2007;1:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morgan RJ, Kuremsky MA, Peindl RD, Fleischli JE. A biomechanical comparison of two suture anchor configurations for the repair of type II SLAP lesions subjected to a peel‐back mechanism of failure. Art Ther. 2008;4:383–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neviaser TJ, Neviaser RJ, Neviaser JS, Neviaser JS. The four‐in‐one arthroplasty for the painful arc syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walch G, Nove‐Josserand L, Levigne C, Renaud E. Tears of the supraspinatus tendon associated with "hidden" lesions of the rotator interval. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;6:353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colbath G, Murray A, Siatkowski S, et al. Autograft long head biceps tendon can be used as a scaffold for biologically augmenting rotator cuff repairs. Art Ther. 2022;1:38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yin L, Zhang H, Kong Y, Zhang X, Yan W, Zhang J. Distance between the supraspinatus and long head of the biceps tendon on sagittal MRI: a new tool to identify anterior supraspinatus insertion injury. J Exp Orthop. 2021;1:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caekebeke P, Duerinckx J, van Riet R. Acute complete and partial distal biceps tendon ruptures: what have we learned? A review. EFORT Open Rev. 2021;10:956–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vangsness CT Jr, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;6:951–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parnes N, Perrine J, Tomaino MM. Arthroscopic evaluation of the long head of the biceps tendon: traditional versus allis clamp techniques. Orthopedics. 2022;1:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tuoheti Y, Itoi E, Minagawa H, et al. Attachment types of the long head of the biceps tendon to the glenoid labrum and their relationships with the glenohumeral ligaments. Art Ther. 2005;10:1242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Pizzo WD, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. Arthroscopy classics. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2010;8:1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kemp JA, Olson MA, Tao MA, Burcal CJ. Platelet‐rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021;3:597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S, Hong IT, Lee S, Kim TS, Jung K, Han SH. Long‐term outcomes of the modified Nirschl technique for lateral epicondylitis: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;1:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tadevich JT, Bhagat ND, Lim BH, Gao J, Chen WW, Merrell GA. Power‐optimizing repair for distal biceps tendon rupture: stronger and safer. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2021;5:266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seo JB, Kwak KY, Park B, Yoo JS. Anterior cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon for reinforcement of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair prevent retear and increase acromiohumeral distance. J Orthop. 2021;23:246–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen CH, Hsu KY, Chen WJ, Shih CH. Incidence and severity of biceps long head tendon lesion in patients with complete rotator cuff tears. J Trauma. 2005;6:1189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prodromos CC, Ferry JA, Schiller AL, Zarins B. Histological studies of the glenoid labrum from fetal life to old age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;9:1344–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murthi AM, Vosburgh CL, Neviaser TJ . The incidence of pathologic changes of the long head of the bicceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O'Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. An anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;1:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pal GP, Bhatt RH, Patel VS. Relationship between the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii and the glenoidal labrum in humans. Anat Rec. 1991;2:278–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Demondion X, Maynou C, Van Cortenbosch B, Klein K, Leroy X, Mestdagh H. Relationship between the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle and the glenoid labrum. Morphologie. 2001;269:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghalayini SR, Board TN, Srinivasan MS . Anoatomic variations in the long head of biceps: contribution to shoulder dysfunction. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas SJ, Sarver JJ, Ebaugh DD, et al. Chronic adaptations of the long head of the biceps tendon and groove in professional baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;5:1047–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kawashima I, Sugaya H, Takahashi N, et al. Assessment of the preserved biceps tendon after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in patients </= 55 years. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehab. 2021;5:e1273–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh JH, Kim JY, Nam KP, Kang HD, Yeo JH. Immediate changes and recovery of the supraspinatus, long head biceps tendon, and range of motion after pitching in youth baseball players: how much rest is needed after pitching? Sonoelastography on the supraspinatus muscle‐tendon and biceps long head tendon. Clin Orthop Surg. 2021;3:385–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]