Abstract

The increasing use and effectiveness of primary systemic treatment (PST) enables tailored locoregional treatment. About one third of clinically node positive (cN+) breast cancer patients achieve pathologic complete response (pCR) of the axilla, with higher rates observed in Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor (HER)2-positive or triple negative (TN) breast cancer subtypes. Tailoring axillary treatment for patients with axillary pCR is necessary, as they are unlikely to benefit from axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), but may suffer complications and long-term morbidity such as lymphedema and impaired shoulder motion. By combining pre-PST and post-PST axillary staging techniques, ALND can be omitted in most cN + patients with pCR. Different post-PST staging techniques (MARI/TAD/SN) show low or ultra-low false negative rates for detection of residual disease. More importantly, trials using the MARI (Marking Axillary lymph nodes with Radioactive Iodine seeds) procedure or sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as axillary staging technique post-PST have already shown the safety of tailoring axillary treatment in patients with an excellent response. Tailored axillary treatment using the MARI procedure in stage I-III breast cancer resulted in 80% reduction of ALND and excellent five-year axillary recurrence free interval (aRFI) of 97%. Similar oncologic outcomes were seen for post-SLNB in stage I-II patients. The MARI technique requires only one invasive procedure pre-NST and a median of one node is removed post-PST, whereas for the SLNB and TAD techniques two to four nodes are removed. A disadvantage of the MARI technique is its use of radioactive iodine, which is subject to extensive regulations.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Primary systemic treatment, Pathologic response, Tailored axillary treatment

Highlights

-

•

Increasing use and effectiveness of primary systemic treatment (PST) enables tailored locoregional treatment.

-

•

Axillary staging techniques after PST (MARI, TAD, SN) show low false negative rates for detection of residual disease.

-

•

Both the MARI and SN trials show excellent 5 yr outcome when axillary treatment after PST is tailored to the response.

1. Introduction

In the past decades, breast cancer treatment is increasingly tailored to tumor subtype and biology [1]. In breast cancer subtypes where systemic treatment (chemotherapy and targeted therapy) is indicated, it is currently common practice to start with systemic treatment followed by locoregional treatment. This so-called primary systemic treatment (PST) enables tailoring of subsequent locoregional treatment to the response to systemic treatment [[2], [3], [4], [5]].

The concept of tailoring local treatment is quite straightforward, as tumor size reduction following PST may enable breast conserving surgery in patients initially planned for mastectomy [2,6]. Increasing the breast conserving surgery rates is one of the achieved goals of PST [[7], [8], [9]].

However, despite axillary pathologic complete response (pCR) rates as high as 80% in node-positive patients with hormone receptor negative (HR-)/Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor positive (HER2+) tumors [5,10], a significant number of patients still undergo ALND [11], leading to unnecessary comorbidity. To what extent axillary treatment may be adjusted remains an unanswered clinical question.

2. Definitions and techniques

When answering this question, various terms and techniques are used (Table 1),

Table 1.

Definition of used terms.

| PST | Primary systemic treatment; systemic treatment (chemotherapy and targeted therapy) administered before surgery |

| cN+ | Abnormal axillary lymph nodes identified with clinical exam and/or imaging (US/PET-CT) with fine needle aspiration or needle biopsy confirming metastatic disease |

| SLNB | Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy |

| MARI | Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed |

| TAD | Targeted Axillary Dissection; consisting of the removal of a marked tumour-positive lymph node combined with SLNB |

As stated above, systemic treatment administered before surgery (PST) has an important advantage compared to adjuvant systemic therapy: the response to systemic therapy can be monitored, allowing for tailored adjuvant systemic treatment [[12], [13], [14]] and tailored locoregional therapy.

Several techniques for axillary staging are available, including non-invasive methods such as ultrasound (US) [15,16], fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) [17,18] or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [19] and minimal-invasive techniques such as SLNB, the MARI procedure and TAD.

SLNB [[20], [21], [22]] is a surgical procedure that involves identifying and removing the first lymph node(s) along the lymphatic drainage pathway from the primary tumor in the breast to the axillary lymph node basin. This can be achieved through either a single or dual tracer technique, which involves the injection of a radioactive tracer, blue dye, or a combination of both to identify the SLN.

In the MARI procedure a tumour-positive axillary lymph node is marked with an iodine seed prior to PST. This MARI-node can be selectively removed and analyzed after PST [23].

Axillary staging using TAD involves removal of a marked tumour-positive node in combination with SLNB [24,25]. Various methods can be used to mark the tumour-positive lymph node such as implantation or injection of titanium clips, radioactive or magnetic seeds or carbon-suspension liquids. In the original TAD as described by Caudle et al. [26] one of the pathologic nodes is marked with a radio-paque marker before PST and only after PST an iodine seed is placed in this node; in the RISAS technique [27], an alternative TAD procedure, the pathologic node is marked with an iodine seed prior to PST.

Tailoring axillary treatment in women with cN + breast cancer after PST requires adequate axillary nodal staging before ánd after PST.

3. Axillary staging before PST

3.1. Non-invasive methods: US – MRI – FDG-PET/CT

Both clinical and pathologic lymph node status are independent prognostic factors for locoregional recurrence and survival in breast cancer patients treated with PST [[28], [29], [30]]. Since the clinical axillary lymph node status is the baseline for tailoring the axillary treatment, accurately staging the axillary lymph node status before undergoing PST is a crucial step.

US has been widely adopted as diagnostic tool to assess axillary lymph node involvement pre-PST as it has greater accuracy compared to physical examination alone. In case of suspicious nodes, US is mostly combined with fine needle aspiration cytology [31]. However, in patients with normal axillary lymph nodes on standard pre-operative MRI, axillary US did not improve axillary staging [32].

Previous studies have shown that FDG-PET/CT is the optimal locoregional staging method before PST, with a high positive predictive value (PPV) of 98% [18] for detecting axillary metastases and the ability to assess the number of FDG-avid axillary lymph nodes [17,33,34]. Although FDG-PET/CT is not currently included in the diagnostic workup for cN + breast cancer patients in most countries, it outperforms US (with a PPV of 70%) and MRI (with a PPV of 76%–78%) [35]. Moreover, since FDG-PET/CT is also an accurate method to assess distant disease, traditional imaging modalities such as computed tomography, chest X-ray, bone scan and liver ultrasound, can be omitted; and it might therefore be more cost-effective [36,37].

4. Axillary staging after PST – accuracy

4.1. Non-invasive methods: US – MRI – FDG-PET/CT

The accuracy of non-invasive methods for axillary staging after PST has been investigated extensively. Due to low identification rates and high false negative rates (FNR) of US (range 25%–65%), MRI (range 14%–62%) and FDG-PET/CT (range 37%–78%); current non-invasive methods are not considered adequate to assess axillary pCR after PST in cN + disease [38,39]. Also, axillary pCR is underestimated in a large proportion of patients since positive predictive values (defined as the percentage of patients with suspicious nodes on imaging who had axillary residual disease) of only 77% for US and 78% for MRI and FDG-PET/CT [38] are reported.

4.2. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

Multiple studies have evaluated the use of SLNB for axillary staging after PST. While post-PST SLNB can safely be applied in cN0 patients, SLNB is associated with a relatively low identification rate (IR) (79%–93%) and high FNR (8.4% - 24.3%) in cN + patients [[40], [41], [42], [43], [44]] (Table 2). Nonetheless, for patients with cN1–2 disease, the FNR for the sentinel node procedure following PST can be reduced to less than 10% if axillary ultrasound after PST shows no suspicious nodes, dual tracers are used, and three or more sentinel nodes are examined [40,41]. However, less than 40% of patients in the SENTINA trial on post-PST SNLB appear to have 3 or more SLNBs [40]. Equating safety of post-SLNB with the number of removed nodes may lead to biased node picking of “almost”-sentinel nodes, a strategy which confers a higher risk of morbidity without being a reliable staging tool. The median number of sentinel nodes after PST in cN + patients varied between two and four (Table 2). Although no correlation has been demonstrated between the number of removed lymph nodes and clinically observed lymphedema, patients may experience more symptoms [[45], [46], [47]].

Table 2.

Overview of accuracy and oncologic outcome of axillary staging techniques.

| Study/Trial | Design | Population | No. of patientsa | No. of LN removed | IR | FNR | Follow-up | Axillary recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy | ||||||||

| ACOSOG Z1071 Boughey et al. [41] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN1-2 | cN1: 663 cN2: 38 |

Median 2 (IQR 1–4) | 93% | 12,6% | – | – |

|

SENTINA Kuehn et al. [40] |

Prospective | cN1-2 converted to ycN0 (Arm C) | 592 | Median 2 | 80% | 14,2% | – | – |

| Zetterlund et al. [42] | Prospective | cT1-4d cN1 (biopsy proven) | 195 | Median 2 (range 2–5) | 79% | 12.6% | – | – |

|

SN FNAC Morency et al. [43] |

Prospective | cT0-3 cN1-2 (biopsy proven) | 153 | – | 88% | 8.4% | – | – |

|

GANEA-2 Classe et al. [44] |

Prospective | cT1-3 cN1-2 (biopsy proven) | 307 | Median 2 (range 1–8) | 80% | 11.9% | – | – |

| Kahler-Ribeiro-Fontana et al. [53] | Retrospective | cT1-3 cN1-2 converted to ycN0 | 123 | Median 2 (range 1–6) | – | – | 10 years | 1.6% |

| Martelli et al. [54] | Prospective | cT2 cN1 | 91 (81 ypN0/10 ypN1) | Median 2 (range 1–8) | – | – | 7 years | 0% |

| Wong et al. [55] | Retrospective | cT1-3 cN1-2 converted to ycN0 | 102 (67 ypN0/35 ypN1) | Median 4 (IQR 3–6) | – | – | 3 years | 2.9% (ypN1) |

| Barrio et al. [56] | Retrospective | cT1-3 cN1 (biopsy proven) converted to ycN0 | 234 | Median 4 (IQR 3–5) | – | – | 3 years | 0.4% |

| Piltin et al. [57] | Retrospective | cT1-4 cN1-3 | 159 (139 ypN0/20 ypN1) | Median 3 (range 1–12) | – | – | 3 years | 0,6% |

| Targeted Axillary Dissection | ||||||||

|

TAD Caudle et al. [25] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN+ | 85 | – | – | 2,0% | – | – |

|

RISAS Simons et al. [24] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN1-3 | 212 (n = 227) | Median 2 (range 1–8) | 98% | 3.5% | – | – |

|

TATTOO Boniface et al. [48] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN1-3 | 149 | – | 99% | 4.9% | ||

|

SenTa Kuemmel et al. [49] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN+ | 91 | – | 85% | 4.3% | – | – |

|

ILINA trial Siso et al. [51] |

Prospective | cT1-3 cN+ | 35 | Median 3 | 96% | 4.1% | ||

|

TAXIS Weber et al. [58] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN+ (by palpation or imaging) | 125 | Median 4 | – | 0% | – | – |

| Wu et al. [50]Wu et al. [50]Wu et al. | Prospective | cT1-3 cN1-3 | 92 | Median 3 | 97% | 10.8% | ||

| Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed | ||||||||

|

MARI Donker et al. [23] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN1-3 | 100 | – | 97% | 7.0% | ||

|

MARI Loevezijn et al. [52] |

Prospective | cT1-4 cN1-3 | 272 | Median 1 (IQR 1–2) | – | – | 3 years | 1.8% |

Abbreviations: SLNB, Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy; TAD; Targeted Axillary Dissection, MARI; Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed; IR, identification rate.

FNR, False Negative Rate.

: Number of patients that underwent SLNB/TAD/MARI.

4.3. TAD

Axillary staging using TAD involves removal of a pre-PST marked node in combination with SLNB [24,25,48,49]. This technique is associated with high IRs and lower FNRs than either SLNB alone or MARI procedure alone [25,27,48]. TAD was first described by Caudle et al. [26] with a reported FNR of 2% [25]. The RISAS procedure achieved a FNR of 3.5% with an IR of 98% [27]. Other studies reported slightly higher FNRs between 4.1% and 10.8% [[48], [49], [50], [51]] (Table 2). Only the RISAS trial reported on the number of removed lymph nodes (median of 2 (range 1–8)).

4.4. MARI

The MARI procedure, in which a pathologically proven axillary lymph node is marked with an iodine marker prior to PST and selectively removed after PST, can reliably predict the axillary response with an IR of 97% and FNR of 7% [23]. In a larger retrospective cohort involving 272 patients, the median number of removed lymph nodes was one (IQR 1–2) [52].

5. Axillary staging after PST – oncologic outcome

5.1. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

Kahler-Ribeiro-Fontana et al. recently reported on 10-year follow up of the use of SLNB in cN0-2 patients who became clinically node-negative (US/FDG-PET/CT) after PST. Of these, 222 patients with pre-PST axillary lymph node involvement were included. There was no requirement for a minimum number of sentinel nodes to be assessed, and in 74% of patients, two or fewer nodes were removed. ALND was only performed in case of positive SLNB (n = 99). In 123 patients with negative SLNB and no further axillary surgery, the 10-year axillary recurrence rate was 1.6% (n = 2) [53,59]. Comparable axillary recurrence rates have been reported by studies including (mainly) cN1 patients [54,57] or cN1-2 patients who became ycN0 after PST. In these studies, follow-up was shorter (three to seven years) and more axillary lymph nodes were removed [55,56] (Table 2). Although the reported low axillary recurrence rates after PST and SLNB at long term follow up are promising, this approach seems only applicable to a select group of cN + breast cancer patients as mainly cN1 breast cancer patients were included. It is important to note that high pCR rates can also be achieved in cN2-3 patients, depending on subtype of breast cancer [60]. Omitting ALND in these patients could greatly reduce co-morbidity, since radiotherapy is indicated regardless of response in these patients [61].

5.2. TAD

As long-term follow up for TAD is lacking, it cannot be determined whether lower FNR also results in better oncological outcome. A recent retrospective study conducted by Montagna et al. included 785 patients with cT1-4cN1-3 tumors from 19 centers in the Oncoplastic Breast Consortium (OPBC) and EUBREAST networks. The study aimed to compare axillary staging with SLNB (using a dual tracer) with TAD, in patients who underwent PST and were ypN0. The median number of removed lymph nodes was lower in the TAD group 3 (IQR 3–5) vs 4 (IQR 3–5)) in the SLNB group. The two-year cumulative incidence of axillary recurrence was similar between patients treated with SLNB or TAD, at 0% versus 0.9% respectively (p-value 0.19). Longer follow-up is necessary to verify these findings, but the advantage of TAD in this selection of patients appears to be a minor reduction in the number of lymph nodes removed [62].

5.3. MARI

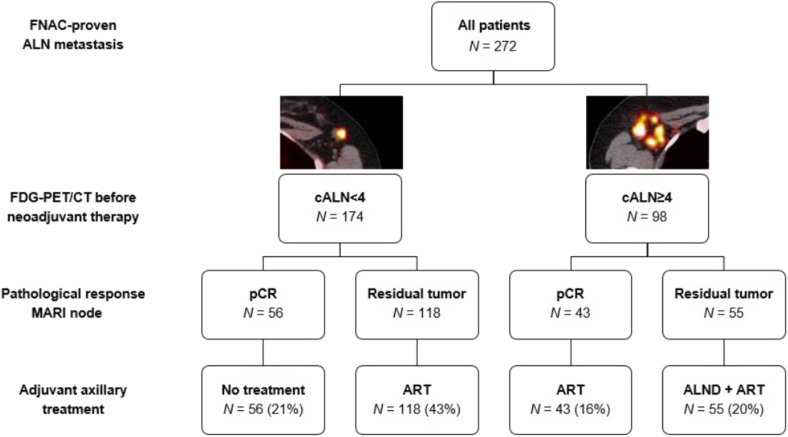

The MARI protocol was developed to tailor axillary treatment by combining the outcome of the MARI procedure after PST [23] with a pre-PST FDG-PET/CT to determine the presence of less or more than four (cALN <4 or cALN ≥4) tumor-positive axillary lymph nodes prior to PST [63] (Fig. 1). In anticipation of the results of the ALLIANCE A011202 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01901094) and NSABP B-51/RTOG1304 trial [64], this axillary treatment algorithm has already been implemented at the Netherlands Cancer Institute and has led to a substantial decrease in ALNDs (82%) for cN + patients, including patients with cN3 disease [52]. In patients with cALN <4 and pCR of the MARI-node (ypMARI-neg), no further axillary treatment was given. In patients with cALN <4, ypMARI-pos and cALN ≥4, ypMARI-neg after PST, irradiation of axillary levels I to IV was performed. ALND was only performed in patients re-staged with cALN ≥4 and ypMARI-pos, followed by locoregional radiation treatment [63] (Fig. 1). Last year, results of the MARI protocol in a group of 272 patients (174 patients with cALN <4 and 78 patients with cALN >4) was published by Loevezijn et al., Twenty-one percent of patients (n = 56) did not receive any further axillary treatment, 59% (n = 161) received ART, and 20% (n = 55) received ALND plus adjuvant ART [52] (Fig. 1). In 80% of cN + patients ALND was omitted without compromising oncologic outcome as an axillary recurrence rate of only 1.8% (n = 5) after a median of three years (IQR 1.9–4.1) follow up was reported.

Fig. 1.

Tailored adjuvant axillary treatment strategy according to the MARI protocol

Abbreviations: FNAC, fine needle aspiration cytology; FDG-PET/CT, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography; MARI, Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed; cALN, clinical axllary lymph node; pCR, pathologic complete response; ART, axillary radiotherapy; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection.

One of the disadvantages of the MARI procedure is the use of iodine seeds which is subject to regulations regarding radioactive material. Advantages of the MARI protocol might outweigh this disadvantage. In contrast to TAD, only one procedure is required prior to PST and no imaging is necessary after PST. Moreover, the number of lymph nodes removed during the procedure is low, with a median of one (IQR 1–2).

Five-year (median 64 months, IQR 54–77) follow up results of the same cohort confirm oncologic safety with an overall axillary recurrence rate of 2.9% (n = 8) and five-year axillary recurrence free interval (aRFI) of 97% with no significant variation observed between the treatment groups (p = value 0.337) (unpublished results). In total, 44 (16%) patients developed one or more recurrences. Distant metastases occurred in 31 (11%) patients, regional (including axillary) metastases were found in 15 (6%) and local recurrences in 10 patients (4%). Location of all breast cancer recurrences per treatment group is shown in Table 3. Fig. 2 shows the five-year recurrence free interval (RFI). In patients with cALN <4, ypMARI-neg who received no further treatment the RFI was 94%, in patients with cALN <4, ypMARI-pos 83%, in cALN ≥4, ypMARI-neg 91% and cALN ≥4, ypMARI-pos 79% (p-value 0.112). Patients with pCR of the MARI-node achieve the highest RFI, indicating its predictive value. In total, 30 (11%) patients died of which 26 (10%) due to breast cancer recurrence, resulting in an overall survival at five year of 91%.

Table 3.

Locations of breast cancer recurrence by response adjusted treatment group.

| cALN<4 (n = 174) |

cALN≥4 (n = 98) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARI pCR (n = 56) |

MARI tumor+ (n = 118) |

MARI pCR (n = 43) |

MARI tumor+ (n = 55) |

||||||

| No treatment | ART | ART | ALND + ART | Total | |||||

| Total patients with event per treatment group* rowhead | |||||||||

| Axillary + Local | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Axillary + Regional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Axillary + Distant | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Local | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Local + Regional | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Local + Distant | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Regional | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Regional + Distant | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Distant | 0 | 13 | 2 | 5 | 20 | ||||

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 5 | 23 | 4 | 12 | 44 | ||||

Abbreviations: cALN, clinical axllary lymph node; MARI, Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed; pCR, pathologic complete response; ART, axillary radiotherapy; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection.

Fig. 2.

Recurrence-free interval by treatment group

Abbreviations: cALN, clinical axllary lymph node; MARI, Marking the Axillary node with an Radioactive Iodine seed; pCR, pathologic complete response; ART, axillary radiotherapy; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection.

6. Conclusion

Although ALND reduces the rate of locoregional recurrence in patients with node-positive disease, it has never been demonstrated to have a positive impact on survival in breast cancer patients. Therefore, the estimated locoregional recurrence risk should be weighed against the significant co-morbidity associated with ALND and/or ART. Above all, axillary management should be adapted to the response to PST. Complications related to SLNB, TAD or MARI, when reported, rarely occur and cost-effectiveness of the procedures is not yet sufficiently investigated. Therefore, we can only compare methods based on accuracy, applicability, and oncological outcome. PST. The currently available data suggests that a FNR of around 10% is sufficient to safely tailor axillary treatment after PST in cN + patients with an excellent response.

Although TAD results in low FNR, there are no data on long-term oncological outcome. Long-term results from both SLNB and MARI show that ALND can be safely omitted in cN + patients after PST. SLNB is the most widely used method, however, the current results may not be applicable to patients with extensive (i.e. N2 or N3) nodal disease. While the implementation of protocols regarding radioactive material requires some effort, the MARI-procedure provides an adequate staging method in all cN + patients (cN1-3) patients post-PST. By using the MARI-protocol, ALND was reduced by 80% in large prospective cohort without compromising oncological outcomes [23,52].

References

- 1.Murphy B.L., Boughey J.C. ASO author reflections: changes in use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy over time-highest rates of use now in triple-negative and HER2+ disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(Suppl 3):695–696. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-7046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin H.C., Han W., Moon H.G., Im S.A., Moon W.K., Park I.A., et al. Breast-conserving surgery after tumor downstaging by neoadjuvant chemotherapy is oncologically safe for stage III breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2582–2589. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2909-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mieog J.S., van der Hage J.A., van de Velde C.J. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for operable breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94(10):1189–1200. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Minckwitz G., Ju Blohmer, Costa S.D., Denkert C., Eidtmann H., Eiermann W., et al. Response-guided neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3623–3630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilewskie M., Morrow M. Axillary nodal management following neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):549–555. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons J.M., Jacobs J.G., Roijers J.P., Beek M.A., Boonman-de Winter L.J.M., Rijken A.M., et al. Disease-free and overall survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: breast-conserving surgery compared to mastectomy in a large single-centre cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185(2):441–451. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05966-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spronk P.E.R., Volders J.H., van den Tol P., Smorenburg C.H., Vrancken Peeters M. Breast conserving therapy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy; data from the Dutch Breast Cancer Audit. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killelea B.K., Yang V.Q., Mougalian S., Horowitz N.R., Pusztai L., Chagpar A.B., et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer increases the rate of breast conservation: results from the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(6):1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puig C.A., Hoskin T.L., Day C.N., Habermann E.B., Boughey J.C. National Trends in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: a national cancer data Base study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(5):1242–1250. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy B.L., Day C.N., Hoskin T.L., Habermann E.B., Boughey J.C. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy use in breast cancer is greatest in excellent Responders: triple-negative and HER2+ subtypes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(8):2241–2248. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasparri M.L., de Boniface J., Poortmans P., Gentilini O.D., Kaidar-Person O., Banys-Paluchowski M., et al. Axillary surgery after neoadjuvant therapy in initially node-positive breast cancer: international EUBREAST survey. Br J Surg. 2022;109(9):857–863. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znac217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda N., Lee S.J., Ohtani S., Im Y.H., Lee E.S., Yokota I., et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147–2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Minckwitz G., Huang C.S., Mano M.S., Loibl S., Mamounas E.P., Untch M., et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):617–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Voort A., van Ramshorst M.S., van Werkhoven E.D., Mandjes I.A., Kemper I., Vulink A.J., et al. Three-year follow-up of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without Anthracyclines in the presence of dual ERBB2 Blockade in patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the TRAIN-2 Randomized, phase 3 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(7):978–984. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez S., Anorbe E., Alcorta P., Lopez F., Alonso I., Cortes J. Role of sonography in the diagnosis of axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer: a systematic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(5):1342–1348. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boughey J.C., Ballman K.V., Hunt K.K., McCall L.M., Mittendorf E.A., Ahrendt G.M., et al. Axillary ultrasound after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and its impact on sentinel lymph node surgery: results from the American College of Surgeons oncology group Z1071 trial (alliance) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(30):3386–3393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koolen B.B., Vrancken Peeters M.J., Aukema T.S., Vogel W.V., Oldenburg H.S., van der Hage J.A., et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT as a staging procedure in primary stage II and III breast cancer: comparison with conventional imaging techniques. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koolen B.B., Valdes Olmos R.A., Elkhuizen P.H., Vogel W.V., Vrancken Peeters M.J., Rodenhuis S., et al. Locoregional lymph node involvement on 18F-FDG PET/CT in breast cancer patients scheduled for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135(1):231–240. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javid S., Segara D., Lotfi P., Raza S., Golshan M. Can breast MRI predict axillary lymph node metastasis in women undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(7):1841–1846. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton D.L., Wen D.R., Wong J.H., Economou J.S., Cagle L.A., Storm F.K., et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127(4):392–399. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krag D.N., Weaver D.L., Alex J.C., Fairbank J.T. Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2(6):335–339. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato K., Shigenaga R., Ueda S., Shigekawa T., Krag D.N. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96(4):322–329. doi: 10.1002/jso.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donker M., Straver M.E., Wesseling J., Loo C.E., Schot M., Drukker C.A., et al. Marking axillary lymph nodes with radioactive iodine seeds for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer patients: the MARI procedure. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):378–382. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons J.M., van Nijnatten T.J.A., van der Pol C.C., van Diest P.J., Jager A., van Klaveren D., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of radioactive iodine seed Placement in the axilla with sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in node-positive breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(11):991–999. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caudle A.S., Yang W.T., Krishnamurthy S., Mittendorf E.A., Black D.M., Gilcrease M.Z., et al. Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1072–1078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caudle A.S., Yang W.T., Mittendorf E.A., Black D.M., Hwang R., Hobbs B., et al. Selective surgical localization of axillary lymph nodes containing metastases in patients with breast cancer: a prospective feasibility trial. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(2):137–143. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Nijnatten T.J.A., Simons J.M., Smidt M.L., van der Pol C.C., van Diest P.J., Jager A., et al. A Novel less-invasive approach for axillary staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with axillary node-positive breast cancer by combining radioactive iodine seed localization in the axilla with the sentinel node procedure (RISAS): a Dutch prospective multicenter Validation study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(5):399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeruss J.S., Mittendorf E.A., Tucker S.L., Gonzalez-Angulo A.M., Buchholz T.A., Sahin A.A., et al. Combined use of clinical and pathologic staging variables to define outcomes for breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):246–252. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillon P., Touati N., Breton-Callu C., Slaets L., Cameron D., Bonnefoi H. Factors predictive of locoregional recurrence following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with large operable or locally advanced breast cancer: an analysis of the EORTC 10994/BIG 1-00 study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamounas E.P., Anderson S.J., Dignam J.J., Bear H.D., Julian T.B., Geyer C.E., Jr., et al. Predictors of locoregional recurrence after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results from combined analysis of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18 and B-27. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(32):3960–3966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnamurthy S., Sneige N., Bedi D.G., Edieken B.S., Fornage B.D., Kuerer H.M., et al. Role of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of indeterminate and suspicious axillary lymph nodes in the initial staging of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95(5):982–988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Nijnatten T.J.A., Ploumen E.H., Schipper R.J., Goorts B., Andriessen E.H., Vanwetswinkel S., et al. Routine use of standard breast MRI compared to axillary ultrasound for differentiating between no, limited and advanced axillary nodal disease in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(12):2288–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuster D., Duch J., Paredes P., Velasco M., Munoz M., Santamaria G., et al. Preoperative staging of large primary breast cancer with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography compared with conventional imaging procedures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4746–4751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groheux D., Espie M., Giacchetti S., Hindie E. Performance of FDG PET/CT in the clinical management of breast cancer. Radiology. 2013;266(2):388–405. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12110853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samiei S., van Nijnatten T.J.A., van Beek H.C., Polak M.P.J., Maaskant-Braat A.J.G., Heuts E.M., et al. Diagnostic performance of axillary ultrasound and standard breast MRI for differentiation between limited and advanced axillary nodal disease in clinically node-positive breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adler L.P., Faulhaber P.F., Schnur K.C., Al-Kasi N.L., Shenk R.R. Axillary lymph node metastases: screening with [F-18]2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) PET. Radiology. 1997;203(2):323–327. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.2.9114082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miquel-Cases A.T.S., Retèl V., Steuten L., Valdés Olmos R., Rutgers E., van Harten W.H. MD4—cost-effectiveness of 18f-Fdg Pet/Ct for screening distant metastasis in stage Ii/Iii breast cancer patients of the UK, the United States and The Netherlands. Value Health. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samiei S., de Mooij C.M., Lobbes M.B.I., Keymeulen K., van Nijnatten T.J.A., Smidt M.L. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive imaging for assessment of axillary response after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in clinically node-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;273(4):694–700. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schipper R.J., Moossdorff M., Beets-Tan R.G.H., Smidt M.L., Lobbes M.B.I. Noninvasive nodal restaging in clinically node positive breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant systemic therapy: a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuehn T., Bauerfeind I., Fehm T., Fleige B., Hausschild M., Helms G., et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boughey J.C., Suman V.J., Mittendorf E.A., Ahrendt G.M., Wilke L.G., Taback B., et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1455–1461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zetterlund L.H., Frisell J., Zouzos A., Axelsson R., Hatschek T., de Boniface J., et al. Swedish prospective multicenter trial evaluating sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in clinically node-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163(1):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morency D., Dumitra S., Parvez E., Martel K., Basik M., Robidoux A., et al. Axillary lymph node ultrasound following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer: results from the SN FNAC study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(13):4337–4345. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Classe J.M., Loaec C., Gimbergues P., Alran S., de Lara C.T., Dupre P.F., et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy without axillary lymphadenectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is accurate and safe for selected patients: the GANEA 2 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173(2):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-5004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldberg J.I., Wiechmann L.I., Riedel E.R., Morrow M., Van Zee K.J. Morbidity of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer: the relationship between the number of excised lymph nodes and lymphedema. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(12):3278–3286. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H.K., Ju Y.W., Lee J.W., Kim K.E., Jung J., Kim Y., et al. Association between number of Retrieved sentinel lymph nodes and breast cancer-related lymphedema. J Breast Cancer. 2021;24(1):63–74. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2021.24.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg J.I., Riedel E.R., Morrow M., Van Zee K.J. Morbidity of sentinel node biopsy: relationship between number of excised lymph nodes and patient perceptions of lymphedema. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(10):2866–2872. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Boniface J., Frisell J., Kuhn T., Wiklander-Brakenhielm I., Dembrower K., Nyman P., et al. False-negative rate in the extended prospective TATTOO trial evaluating targeted axillary dissection by carbon tattooing in clinically node-positive breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;193(3):589–595. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06588-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuemmel S., Heil J., Rueland A., Seiberling C., Harrach H., Schindowski D., et al. A prospective, multicenter Registry study to evaluate the clinical feasibility of targeted axillary dissection (TAD) in node-positive breast cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2022;276(5):e553–e562. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu S., Wang Y., Zhang N., Li J., Xu X., Shen J., et al. Intraoperative touch imprint cytology in targeted axillary dissection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients with initial axillary metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(11):3150–3157. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siso C., de Torres J., Esgueva-Colmenarejo A., Espinosa-Bravo M., Rus N., Cordoba O., et al. Intraoperative ultrasound-guided excision of axillary clip in patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy (ILINA trial) : a New tool to Guide the excision of the clipped node after neoadjuvant treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(3):784–791. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Loevezijn A.A., van der Noordaa M.E.M., Stokkel M.P.M., van Werkhoven E.D., Groen E.J., Loo C.E., et al. Three-year follow-up of de-escalated axillary treatment after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in clinically node-positive breast cancer: the MARI-protocol. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;193(1):37–48. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06545-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahler-Ribeiro-Fontana S., Pagan E., Magnoni F., Vicini E., Morigi C., Corso G., et al. Long-term standard sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer: a single institution ten-year follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(4):804–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martelli G., Barretta F., Miceli R., Folli S., Maugeri I., Listorti C., et al. Sentinel node biopsy alone or with axillary dissection in breast cancer patients after primary chemotherapy: long-term results of a prospective interventional study. Ann Surg. 2022;276(5):e544–e552. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong S.M., Basik M., Florianova L., Margolese R., Dumitra S., Muanza T., et al. Oncologic safety of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(5):2621–2629. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barrio A.V., Montagna G., Mamtani A., Sevilimedu V., Edelweiss M., Capko D., et al. Nodal recurrence in patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with sentinel node biopsy alone after neoadjuvant chemotherapy-A Rare event. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(12):1851–1855. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piltin M.A., Hoskin T.L., Day C.N., Davis J., Jr., Boughey J.C. Oncologic outcomes of sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(12):4795–4801. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber W.P., Matrai Z., Hayoz S., Tausch C., Henke G., Zwahlen D.R., et al. Tailored axillary surgery in patients with clinically node-positive breast cancer: pre-planned feasibility substudy of TAXIS (OPBC-03, SAKK 23/16, IBCSG 57-18, ABCSG-53, GBG 101) Breast. 2021;60:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galimberti V., Ribeiro Fontana S.K., Vicini E., Morigi C., Sargenti M., Corso G., et al. This house believes that: sentinel node biopsy alone is better than TAD after NACT for cN+ patients. Breast. 2023;67:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samiei S., Simons J.M., Engelen S.M.E., Beets-Tan R.G.H., Classe J.M., Smidt M.L., et al. Axillary pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant systemic therapy by breast cancer subtype in patients with initially clinically node-positive disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6) doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebctcg, McGale P., Taylor C., Correa C., Cutter D., Duane F., et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2127–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giacomo Montagna M.M., Botty Astrid, Andrea V., Barrio, Sevilimedu Varadan, Judy C., Boughey, et al. Abstract GS4-02: oncological outcomes following omission of axillary lymph node dissection in node positive patients downstaging to node negative with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: the OPBC-04/EUBREAST-06/OMA study. Cancer Res. 2023;83 doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS22-GS4-02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koolen B.B., Donker M., Straver M.E., van der Noordaa M.E.M., Rutgers E.J.T., Valdes Olmos R.A., et al. Combined PET-CT and axillary lymph node marking with radioactive iodine seeds (MARI procedure) for tailored axillary treatment in node-positive breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 2017;104(9):1188–1196. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mamounas Hb E.P., White J.R., Julian T.B., Khan A.J., Shaitelman S.F., Torres M.A. Abstract OT2-03-02: NRG oncology/NSABP B-51/RTOG 1304: phase III trial to determine if chest wall and regional nodal radiotherapy (CWRNRT) post mastectomy (Mx) or the addition of RNRT to breast RT post breast-conserving surgery (BCS) reduces invasive breast cancer recurrence-free interval (IBCR-FI) in patients (pts) with positive axillary (PAx) nodes who are ypN0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NC) Cancer Res. 2018;78 doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS17-OT2-03-02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]