Abstract

Food remains a major source of human exposure to chemical contaminants that are unintentionally present in commodities globally, despite strict regulation. Scientific literature is a valuable source of quantification data on those contaminants in various foods, but manually summarizing the information is not practicable. In this review, literature mining and machine learning techniques were applied in 72 foods to obtain relevant information on 96 contaminants, including heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxins, furans, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides, mycotoxins, and heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs). The 11,723 data points collected from 254 papers from the last two decades were then used to identify the patterns of contaminants distribution. Considering contaminant categories, metals were the most studied globally, followed by PAHs, mycotoxins, pesticides, and HAAs. As for geographical region, the distribution was uneven, with Europe and Asia having the highest number of studies, followed by North and South America, Africa and Oceania. Regarding food groups, all contained metals, while PAHs were found in seven out of 12 groups. Mycotoxins were found in six groups, and pesticides in almost all except meat, eggs, and vegetable oils. HAAs appeared in only three food groups, with fish and seafood reporting the highest levels. The median concentrations of contaminants varied across food groups, with citrinin having the highest median value. The information gathered is highly relevant to explore, establish connections, and identify patterns between diverse datasets, aiming at a comprehensive view of food contamination.

Keywords: Food-chain contaminants, Food toxicants, Literature review, Contaminant data, Exposome, Unavoidable exposure

Highlights

-

•

Retrospective data on food contaminants quantification given by scientific literature.

-

•

The most studied were metals followed by PAHs, mycotoxins, pesticides, and HAAs.

-

•

Highest number of studies in Europe and Asia, uneven geographical distribution.

-

•

Different patterns of contaminants distribution in highly produced/consumed foods.

Abbreviations

- 4,8dMQx

2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline

- 7,8dMQx

2-Amino-3,7,8-trimethylimidazo(4,5-f)quinoxaline

- 8MQx

2-amino-3,8-dimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline

- AαC

2-amino-α-carboline

- AAL

Alternaria toxins

- Ace

Acenaphthene

- ACET

Acetamiprid

- Acy

Acenaphthylene

- AFB1

Aflatoxin B1

- An

Anthracene

- As

Arsenic

- B[a]A

Benz[a]anthracene

- B[a]P

Benzo[a]pyrene

- B[b]F

Benzo[b]fluoranthene

- BEA

Beauvericin

- B[ghi]P

Benzo[g,h,i]perylene

- B[k]F

Benzo[k]fluoranthene

- Cd

Cadmium

- Chr

Chrysene

- CIT

Citrinin

- CP

Cypermethrin

- CPS

Chlorpyrifos

- CULM

Culmorin

- D[ah]A

Dibenz[a,h]anthracene

- DLM

Deltamethrin

- DON

Deoxynivalenol

- ENs

Enniatins

- ErAs

Ergot alkaloids

- FB1

Fumonisin B1

- FHCl

Formetanate (hydrochloride)

- Fla

Fluoranthene

- Fle

Fluorene

- FSA

Fusaric Acid

- GP1

2-Amino-6-methyldipyrido[1,2-a:3′,2′-d]imidazole

- GP2

2-aminodipyrido(1,2-a-3′,2′-d)imidazole

- H

Harman

- HAAs

Heterocyclic aromatic amines

- Hg

Mercury

- Ind

Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene

- IQ

2-Amino-3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoline

- IQx

3-Methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoxalin-2-amine

- LCH

λ-cyhalothrin

- MAαC

2-amino-3-methyl-α-carboline

- MIQ

2-amino-3,4-dimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoline

- ML

Machine learning

- MML

Methomyl

- MON

Moniliformin

- Nap

Naphthalene

- NH

Norharman

- NIV

Nivalenol

- OTA

Ochratoxin A

- PAHs

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- PAT

Patulin

- Pb

Lead

- PCZ

Propiconazole

- Ph

Phenanthrene

- PhIP

2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine

- Py

Pyrene

- PYR

Pyraclostrobin

- TBZ

Tebuconazole

- TBD

Thiabendazole

- TP1

3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole

- TP2

3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole

- ST

Sterigmatocystin

- T2

T-2 toxin

- TeA

Tenuazonic acid

- ZEN

Zearalenone

1. Introduction

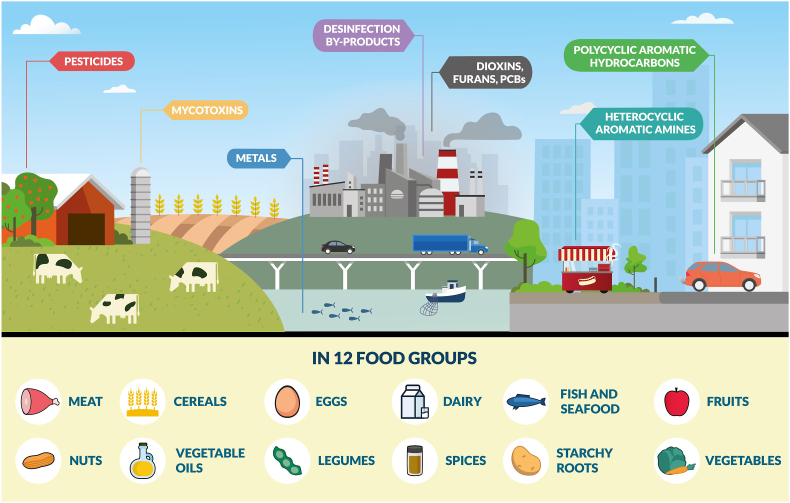

Despite strict regulatory systems imposed for food contaminants to facilitate world trade and protect consumers' health (European Court of Auditors, 2019), foods remain a major route for human exposure to chemical contamination because hazardous toxicants are unintentionally present in commodities produced all over the world, making exposure to those chemicals unavoidable (European Court of Auditors, 2019; Thompson and Darwish, 2019). As schematized in Fig. 1, a diversity of contaminants can enter food-chain: i) environmental pollutants, including heavy metals (Pinto et al., 2016), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, and furans (Fechner et al., 2022), abundant in areas of intense industrial, shipping and/or commercial activities, are dispersed in the soil, water and air (Melo et al., 2012); ii) polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) formed during incomplete combustion of carbonaceous material are ubiquitous in the environment (Raposo et al., 2022) and accumulated in smoked and charcoal-grilled products (Silva et al., 2018; Viegas et al., 2014); iii) residues of agricultural chemicals, such as pesticides, may remain in food products after intentional use(EC, 2018; Pesticide residues in food, 2022); iv) mycotoxins, produced by fungi (Sá et al., 2021); v) processing contaminants as heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs), formed by cooking muscle foods (Viegas et al., 2015), or disinfection by-products formed in situ when disinfectants react with dissolved organic matter (Vizioli et al., 2022).

Fig. 1.

Hazardous chemicals from different origins (environmental pollutants, agricultural/natural/processing contaminants, among others) can reach all types of food commodities. Twelve food groups were formed based on similar characteristics of foods. Correspondence between names in the figure and the respective group of foods can be seen in detail in Table S1. The icons selected for each food group are used throughout the manuscript.

Scientific literature provides a great amount of valuable data concerning analyses of food contaminants in different foods; however, information is dispersed and summarizing it manually is not feasible. To tackle this gap, our goal was to implement a systematic organization of existing knowledge concerning food contaminants in highly produced/consumed food items, using a Pubmed Entrez API based protocol and machine learning (ML) techniques, and apply exploratory data analysis to identify the patterns of contaminants distribution, in a great variety of foods, over the last two decades.

2. Pool of foods, selection of contaminants, literature mining and machine learning

Food items were chosen based on the highest worldwide food supply according to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization statistical database (FAOSTAT, 2022), except for the fish/seafood group, due to the lack of the intended and relevant data. In this case, data were collected from the European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EC, 2019) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (National Marine Fisheries Service, 2020). Food items were organized in aggregated food groups based on the FoodEx2 system (Table S1). The groups were based on hierarchical level 1, except for the “Legumes”, “Nuts, oilseeds and oilfruits” and “Spices” (hierarchical level 2), and “Vegetable fats and oils, edible” (hierarchical level 3). Contaminants selection was based on EU reports, regulation, recommendations and reference publications (EC, 2006, 2013, 2018; EFSA, 2014; European Court of Auditors, 2019; Thompson and Darwish, 2019; Viegas et al., 2015; Vizioli et al., 2022).

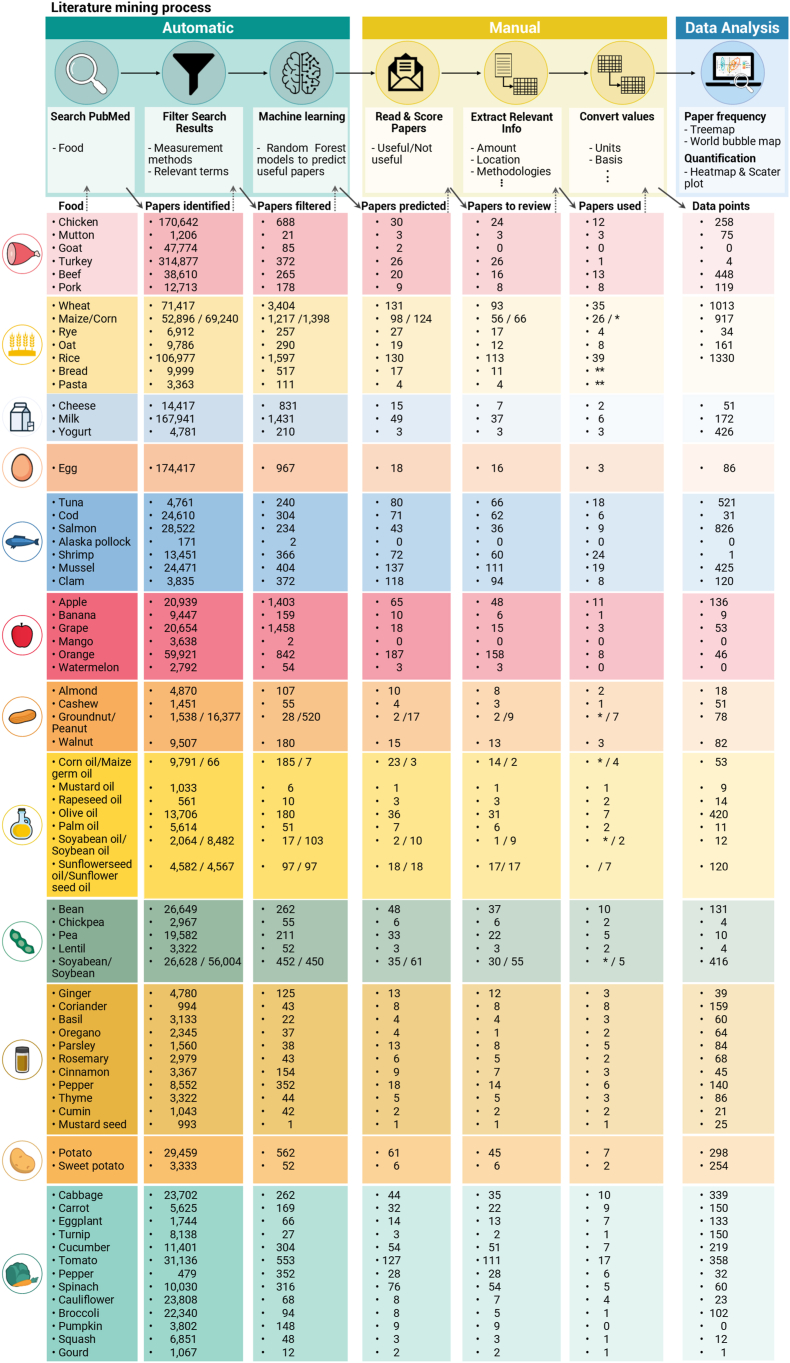

The FoodMine's protocol (Hooton et al., 2020) was used for literature mining as summarized in Fig. 2 and detailed in Supplementary File 1. Some modifications were done to the codes used, namely the terms included in the predefined (restricted to food and contaminants under study) and generic (i.e., ‘food’, ‘contaminant’, ‘database’) dictionaries, as well as measurement methods (i.e., ‘spectrometry’, ‘chromatography’, ‘spectrophotometry’). Since the algorithm performs the search in PubMed, search strategy for food terms was optimised considering PubMed's automated term mapping and our specific goal (Supplementary file 1). This process was carried out for 72 foods across 12 food groups included in the study. A total of 96 food contaminants were searched, including 4 heavy metals, 16 PAHs, 9 dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs, 13 pesticide residues, 5 disinfection by-products, 15 heterocyclic aromatic amines, and 34 mycotoxins. ML algorithm applied to predict potentially useful papers showed good performance metrics, namely cross-validation (10 k-fold) = 0.9100, Accuracy = 0.8600, Sensitivity = 0.9223, Specificity: 0.7977, and F1 score = 0.8682. A total of 1,932,345 papers were identified initially, a number that was narrowed to 26,739 after applying the text matching filter. The ML algorithm was subsequently applied to the remaining foods, resulting in a subset of 2442 papers classified as potentially useful (Martins et al., 2023). Nine of the authors of this publication contributed to manual evaluation. Papers were divided by food groups, with each one having three authors independently reviewing them. In all steps, selection disagreements were solved by meeting with all authors and making decisions together regarding the inclusion or exclusion of the papers. Papers prior to 2000 and not related to selected contaminants or foods were assigned as “not useful” and removed. The full texts of the remaining 1924 papers were reviewed. Articles with no access to the full text, not written in English, reviews, conference papers, books, as well as studies with quantification in spiked food samples and/or in a mixture of foods were not included. Studies reporting data as below limits of detection/quantification but without providing values were also excluded. After removing duplicates, 254 papers were used to collect 11,723 data points. Finally, content values across all data points were standardised in units of μg/kg and weight basis.

Fig. 2.

Overview of literature mining and data collection process. The automatic step started with a list of paper titles and abstracts that were obtained using Pubmed Entrez API, followed by text matching to automatically filter the search results and classified (potentially useful/not useful) by a machine learning algorithm, obtaining a subset of papers. This subset was then read and manually evaluated. If papers contained information on the 96 food contaminants quantification for the 72 foods included in the study, relevant information was manually extracted. Finally, values were converted to comparable units. The bars show, by food group, the results obtained in every step for each food included in the study.

* Only one food nomenclature was chosen for the output, and the corresponding nomenclature was omitted; ** These food items were included in wheat output.

The number of papers, as well as the number of data points obtained varied among food groups (Fig. 2). Meat and Cereals had the highest number of initial papers (585,822 and 330,590, respectively), while Nuts, Spices, and Starchy Roots had the lowest (33,743, 33,509, and 32,792). The ML paper classification algorithm step contributed to the highest reduction of papers, with values ranging from 0.02% (Eggs) to 0.27% (Fish and Seafood) of papers filtered. Between 68% (Cereals) and 86% (Meat) of papers to review were dated from 2000 to 2022. Papers used to collect data points ranged from 10% (Fruits) to 54% (Spices) from the papers to review. Cereals had the highest data points (3,455), while Eggs had the lowest (86).

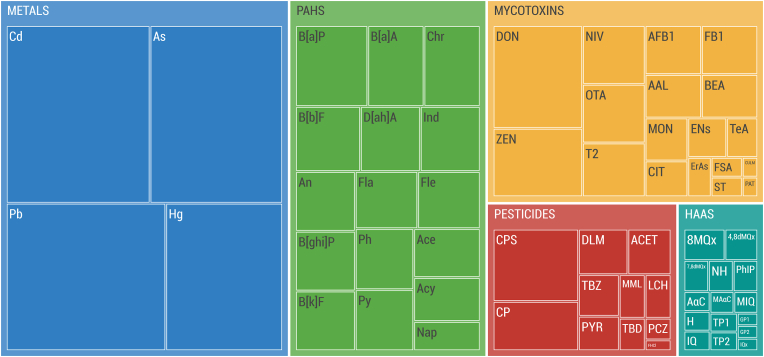

3. Distribution of papers grouped by contaminant

The distribution of works resulting from the complete process of literature mining was grouped in a treemap plot according to contaminant categories (Fig. 3). Dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs, and disinfection by-products are not represented since no useful information could be retrieved from papers obtained from the literature mining. The treemap shows that metals (271) are the most studied contaminant category globally, followed by PAHs (185), mycotoxins (148), pesticides (77) and HAAs (35). Within metals, the specific toxicants studied are in general well balanced with 77, 71, 71 and 52 papers, respectively, for Cd, Pb, As and Hg. Regarding PAHs, the data is evenly distributed across all considered contaminants. B[a]P and Nap compiled the largest and smallest number of quantitative studies, respectively, ranging from 18 to 6. The mycotoxins herein represented are very more heterogeneous regarding the number of studies: DON (30), ZEN (20), OTA and NIV (12 each), T2 (11), AFB1 and FB1 (9 each), AAL and BEA (8 each), MON (6), CIT and ENs (5 each), TeA (4), ErAs (3), FSA and ST (2 each) and also CULM and PAT (1 each).

Fig. 3.

Treemap plot showing the distribution of the 254 papers resulting from mining, grouped, and coloured according to the contaminant categories, reflecting the study pattern of different food contaminants.

HAAs: 4,8dMQx, 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline; 7,8dMQx, 2-Amino-3,7,8-trimethylimidazo(4,5-f)quinoxaline; 8MQx, 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline; AαC, 2-amino-α-carboline; GP1, 2-Amino-6-methyldipyrido[1,2-a:3′,2′-d]imidazole; GP2, 2-aminodipyrido(1,2-a-3′,2′-d)imidazole; H, Harman; IQ, 2-Amino-3-methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoline; IQx, 3-Methyl-3H-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoxalin-2-amine; MAαC, 2-amino-3-methyl-α-carboline; MIQ, 2-amino-3,4-dimethylimdazo[4,5-f]quinoline; NH, Norharman; PhIP, 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine; TP1, 3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole; TP2, 3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole.

Metals: As, Arsenic; Cd, Cadmium; Pb, Lead; Hg, Mercury.

Mycotoxins: AAL, Alternaria toxins; AFB1, Aflatoxin B1; BEA, Beauvericin; CIT, Citrinin; CULM, Culmorin; DON, Deoxynivalenol; ENs, Enniatins; ErAs, Ergot alkaloids; FB1, Fumonisin B1; FSA, Fusaric Acid; MON, Moniliformin; NIV, Nivalenol; OTA, Ochratoxin A; PAT, Patulin; ST, Sterigmatocystin; T2, T-2 toxin; TeA, Tenuazonic acid; ZEN, Zearalenone.

PAHs: Ace, Acenaphthene; Acy, Acenaphthylene; An, Anthracene; B[a]A, Benz[a]anthracene; B[a]P, Benzo[a]pyrene; B[b]F, Benzo[b]fluoranthene; B[ghi]P, Benzo[g,h,i]perylene; B[k]F, Benzo[k]fluoranthene; Chr, Chrysene; D[ah]A, Dibenz[a,h]anthracene; Fla, Fluoranthene; Fle, Fluorene; Ind, Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene; Nap, Naphthalene; Ph, Phenanthrene; Py, Pyrene.

Pesticides: ACET, Acetamiprid; CPS, Chlorpyrifos; CP, Cypermethrin; DLM, Deltamethrin; FHCl, Formetanate (hydrochloride); MML, Methomyl; PCZ, Propiconazole; PYR, Pyraclostrobin; TBZ, Tebuconazole; TBD, Thiabendazole; LCH, λ-cyhalothrin.

Pesticide data reports are dispersed across the 12 representative molecules: CPS (22) and CP (15) are the ones whose levels found in food are most frequently reported. The number of studies found for the remaining pesticides was less than ten for each, ranging from eight for DLM to one for FHCl. Lastly, despite the importance of HAAs as food contaminants, their representativeness in the treemap is very low; therefore, in the future, special attention should be paid to this group. Even so, of the 15 HAAs here studied, 8MQx is the one that gathers the most data (5), followed by 4,8dMQx (4), 7,8dMQx, NH and PhIP (3 each), AαC, H, IQ, MAαC, MIQ, TP1 and TP2 (2 each), and finally GP1, GP2 and IQx which have only one study each.

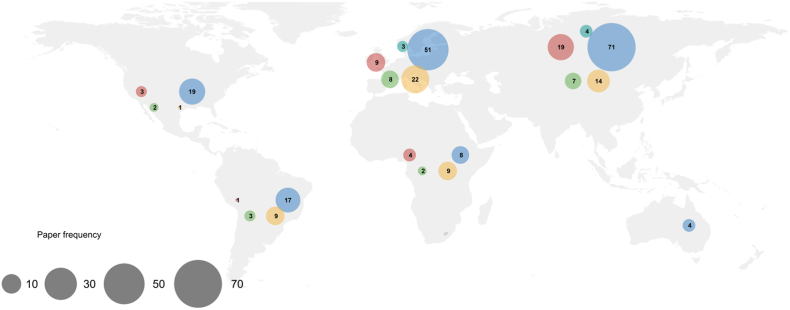

4. Distribution of papers grouped by geographical location

Fig. 4 presents a graphical overview of papers distribution by geographical origin divided by the regions: Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania, North and South America. The figure indicates that the worldwide geographical distribution of papers dealing with contaminants quantification in food is not homogeneous. Europe and Asia presented a higher number of studies, followed by North and South America, Africa and Oceania. This uneven distribution can be explained by several factors, namely: (i) probability of contamination phenomena, (ii) demands from contamination prevention strategies, (iii) regulation and certification requirements, which induces methodological developments, (iv) availability of analytical and research capacity, (v) awareness and demanding level of consumers, etc. Moreover, the number of reports does not always reflect local requirements, as is the case of foodstuffs imported to the EU in which the country of origin is legally responsible for compliance with EU legislation (EC, 2007).

Fig. 4.

Bubble world map with the distribution of papers resulting from literature mining by geographical region (i.e., Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America) distribution. Bubbles' size increases according to paper frequency. Bubble's colours represent a group of contaminants: dark cyan for HAAs, blue for Metals, yellow for Mycotoxins, green for PAHs, and red for Pesticides. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The described distribution is most probably dynamic and subjected to many changes in the upcoming years, particularly related to the fast evolving climate changes and the global food trade complexity rises (Knüsli et al., 2015). Climate change is foreseen to play a particularly relevant role in the probability of contamination, which depends on environmental factors (temperature, humidity, and rainfall) and farm management practices (cropping, harvesting, and storage conditions), key players in contamination occurrence of many of the reported chemicals.

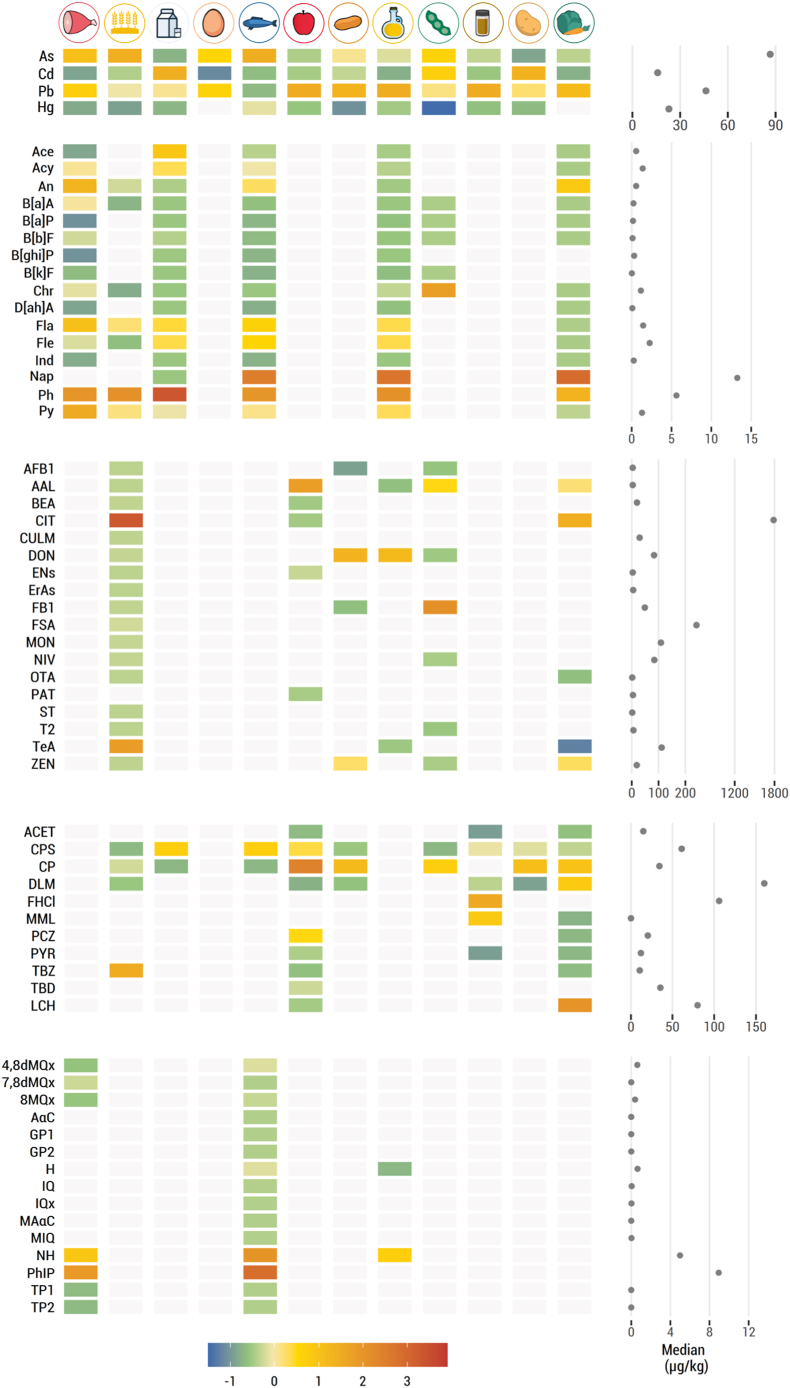

5. Distribution of contaminants data mined in foods sorted by food group

The distribution of contaminants data mined in foods sorted by food group is presented in Fig. 5. The heatmap summarises contaminants concentration (μg/kg) z-scores (by contaminant group) in the 12 food groups. Each heatmap cell shows the z-score of positive samples for a given contaminant and food group through a chromatic scale (from dark blue, low values, to dark red, high values). Grey cells correspond to missing values. The scatter plot presents the median concentration of each contaminant for all foods, expressed as μg/kg.

Fig. 5.

Heatmap: Distribution of contaminants data mined in foods sorted by food group. The heatmap summarises contaminants concentration (μg/kg) z-scores (by contaminant group) in the 12 food groups. Each heatmap cell shows the z-score of positive samples for a given contaminant and food group through a chromatic scale (from dark blue, low values, to dark red, high values). Grey cells correspond to missing values. Scatter plot: Median concentration of each contaminant for all raw materials/foods in the 12 food groups, expressed as μg/kg. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Metals were reported in all food groups, in a wide range of concentrations (up to 90 μg/kg), being As the toxicant found in higher levels. All four targeted elements were found in all food groups except Hg in eggs and vegetables. PAHs are the second most reported compounds appearing in seven of the 12 groups. Meat, dairy, fish and seafood, and vegetable oils contained all 16 compounds. Cereals, legumes and vegetables contain at least five, and the other groups have none. Nap and PhIP were found in higher concentrations. Mycotoxins contamination was described in six of the 12 food groups; higher levels were observed for cereals, fruits, nuts, vegetable oils, legumes and vegetables. The mycotoxins median concentration was evenly distributed, except for CIT, with a medium value of 1800 μg/kg. Pesticide residues were reported in almost all foods (except meat, eggs and vegetable oils), with a greater diversity of residues observed in cereals, fruits, spices and vegetables. The pesticides with the highest median concentration across all food groups are DLM and FHCl. HAA appeared only in three food groups (meat, fish and seafood, and vegetable oils), being NH and PhIP those reported in higher concentrations. Fish and seafood was the only group reporting all the HAAs targeted.

6. Conclusions

Relevant information concerning the distribution and quantification of food contaminants in highly produced/consumed food items in the last two decades was summarized. A significant amount of data was extracted to create a FAIR database to be shared with the scientific community. The information collected is of major relevance to explore, make linkages, and find patterns between diverse datasets. Nevertheless, some limitations must be pointed out. This FoodMine protocol is based on retrospective data up to 2022, and external factors, such as production conditions, climate changes, food availability, legislation parameters, among others, may change those patterns. Consequently, the database must be regularly updated in the future. Moreover, the data quality depends on the original studies, which can differ from one study to another and may generate some bias. Also, in upcoming application, additional search engines APIs should be used, which will require modifications of FoodMine protocol, since they have different search criteria. In conclusion, the adaptations carried out on the original FoodMines’ ML algorithm showed good performance metrics and excellent potential to be applied in an extremely large pool of papers that need to be revised and the possibility of improvement.

Funding

This research was supported by help DIETxPOSOME project (PTDC/SAU-NUT/6061/2020).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zita E. Martins: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Helena Ramos: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization. Ana Margarida Araújo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Marta Silva: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Mafalda Ribeiro: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Armindo Melo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Catarina Mansilha: Conceptualization, Visualization. Olga Viegas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation. Miguel A. Faria: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Isabel M.P.L.V.O. Ferreira: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Zita E. Martins acknowledges support from QREN (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000052). Marta Silva acknowledges FCT for the Ph.D. Grant (2020.05266. BD). Miguel A. Faria acknowledges FCT/MEC for the researcher contract. This work was also supported by FCT – UIDB/50006/2020 and project SYSTEMIC from ERA-NET ERA-HDHL (n° 696295). Authors acknowledge support and collaboration provided by FoodMine author Giulia Menichetti (Network Science Institute, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA).

Handling Editor: Professor A.G. Marangoni

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100557.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The raw data and processing code were made available by us at https://github.com/I3ALAQV/Literature_mining_of_contaminants_in_food_groups.

Current Research in Food Science (Reference data) (Github)

References

- EC Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs and its amendments. Off. J. Eur. Union L. 2006;364:5–24. [Google Scholar]

- EC Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General. Managing food contaminants: how the EU ensures that our food is safe. 2007. www.heatox.org

- EC Commission Recommendation of 27 March 2013 on the presence of T-2 and HT-2 toxin in cereals and cereal products. Off. J. Eur. Union L. 2013;91:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- EC . 2018. European Commission – Pesticides in the European Union Authorisation and Use. [Google Scholar]

- EC . Publications Office; 2019. Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, the EU Fish Market : 2019 Edition. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic in the European population. European Food Safety Authority. EFSA J. 2014;12(3):3597. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Court of Auditors Chemical hazards in our food. EU food safety policy protects us but faces challenges. 2019;287(2) https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=48864 [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT 2022. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

- Fechner C., Frantzen S., Lindtner O., Mathisen G.H., Lillegaard I.T.L. Human dietary exposure to dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs through the consumption of Atlantic herring from fishing areas in the Norwegian Sea and Baltic Sea. J. Fish. China. 2022;18(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hooton F., Menichetti G., Barabási A.L. Exploring food contents in scientific literature with FoodMine. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knüsli D., Friedli R., Busenhart J. Food safety in a globalised world. Swiss Re. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Martins Z.E., Ramos H., Araújo A.M., Silva M., Ribeiro M., Melo A., Mansilha C., Viegas O., Faria M.A., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. DIETxPOSOME - selection of potentially useful papers from literature mining and machine learning protocols. Zenodo. 2023 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7826130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo A., Cunha S.C., Mansilha C., Aguiar A., Pinho O., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. Monitoring pesticide residues in greenhouse tomato by combining acetonitrile-based extraction with dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction followed by gas-chromatography–mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2012;135(3):1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Fisheries Service . U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Current Fishery Statistics; 2020. Fisheries of the United States, 2018.https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/commercial-fishing/fisheries-united-states-2018 No. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pesticide residues in food 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pesticide-residues-in-food

- Pinto E., Almeida A., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. Essential and non-essential/toxic elements in rice available in the Portuguese and Spanish markets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016;48:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo A., Mansilha C., Veber A., Melo A., Rodrigues J., Matias R., Rebelo H., Grossinho J., Cano M., Almeida C., Nogueira I.D., Puskar L., Schade U., Jordao L. Occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, microplastics and biofilms in Alqueva surface water at touristic spots. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;850 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sá S.V. M.d., Monteiro C., Fernandes J.O., Pinto E., Faria M.A., Cunha S.C. Emerging mycotoxins in infant and children foods: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021;63(12):1707–1721. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1967282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M., Viegas O., Melo A., Finteiro D., Pinho O., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. Fast and reliable extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from grilled and smoked muscle foods. Food Anal. Methods. 2018;11(12):3495–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L.A., Darwish W.S. Environmental chemical contaminants in food: review of a global problem. J. Toxicol. 2019;2345283 doi: 10.1155/2019/2345283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas O., Moreira P.S., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. Influence of beer marinades on the reduction of carcinogenic heterocyclic aromatic amines in charcoal-grilled pork meat. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2015;32(3):315–323. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2015.1010607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas O., Yebra-Pimentel I., Martínez-Carballo E., Simal-Gandara J., Ferreira I.M.P.L.V.O. Effect of beer marinades on formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in charcoal-grilled pork. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(12):2638–2643. doi: 10.1021/jf404966w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizioli B.C., Hantao L.W., Montagner C.C. In: Emerging Freshwater Pollutants: Analysis, Fate and Regulations. Dalu T., Tavengwa N., editors. Elsevier; Netherlands, United Kingdom and United States: 2022. Disinfection byproducts in emerging countries; pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data and processing code were made available by us at https://github.com/I3ALAQV/Literature_mining_of_contaminants_in_food_groups.

Current Research in Food Science (Reference data) (Github)