Abstract

The neural and cognitive processes underlying the flexible allocation of attention undergo a protracted developmental course with changes occurring throughout adolescence. Despite documented age-related improvements in attentional reorienting throughout childhood and adolescence, the neural correlates underlying such changes in reorienting remain unclear. Herein, we used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to examine neural dynamics during a Posner attention-reorienting task in 80 healthy youth (6–14 years old). The MEG data were examined in the time-frequency domain and significant oscillatory responses were imaged in anatomical space. During the reorienting of attention, youth recruited a distributed network of regions in the fronto-parietal network, along with higher-order visual regions within the theta (3–7 Hz) and alpha-beta (10–24 Hz) spectral windows. Beyond the expected developmental improvements in behavioral performance, we found stronger theta oscillatory activity as a function of age across a network of prefrontal brain regions irrespective of condition, as well as more limited age- and validity-related effects for alpha-beta responses. Distinct brain-behavior associations between theta oscillations and attention-related symptomology were also uncovered across a network of brain regions. Taken together, these data are the first to demonstrate developmental effects in the spectrally-specific neural oscillations serving the flexible allocation of attention.

Keywords: Attention, Magnetoencephalography, Oscillations, Visual attention, Posner, Validity effect

Highlights

-

•

The development of cortical dynamics supporting attention reorienting were examined.

-

•

Theta and alpha-beta range oscillations were observed across a distributed network.

-

•

Marked age-related increases in prefrontal theta oscillations were observed.

-

•

Greater attention symptomology related to lower theta during attention reorienting.

1. Introduction

Attention, or the ability to focus on behaviorally-relevant information among irrelevant sensory information, is fundamental to goal-directed behavior and cognitive processing more broadly. Attention must be flexibly allocated based on the stream of incoming information, which provides cues towards the spatial location and/or timing of behaviorally relevant information. This ability to attend to cued spatial locations (orienting) and flexibly update attention (reorienting) has been frequently probed using the Posner task where stimuli appear in either a cued (valid) or un-cued (invalid) hemifield, respectively (Petersen and Posner, 2012, Posner, 2016, Posner, 2012, Posner, 1980, Posner et al., 2007). The Posner task robustly elicits a “validity effect” or “reorienting effect,” whereby invalidly-cued targets induce longer response latencies compared to validly-cued targets, suggesting a behavioral cost of attentional reorientation. Converging evidence suggests that although orienting abilities are generally stable by 4–6 months of age (Brodeur and Enns, 1997; Rueda et al., 2004), reorienting continues to be refined from childhood to adulthood (Abundis-Gutiérrez et al., 2014, Enns and Brodeur, 1989, Iarocci et al., 2009, Konrad et al., 2005, Nussenbaum et al., 2019; but see Leclercq and Siéroff, 2013; Lewis et al., 2018). These age-related improvements accompany developmental milestones and advancements in cognitive functioning (e.g., academic performance; Cardoso-Leite and Bavelier, 2014; Heim and Keil, 2012). Conversely, a reduced ability to flexibly allocate attention during development has been linked to poorer academic performance (Stevens and Bavelier, 2012) and neurocognitive disorders (Amso and Scerif, 2015, Scerif and Steele, 2011). Taken together, developmental changes in attentional reorientation appear to support neurocognitive development more broadly, with implications for adaptive functioning in adulthood.

Despite developmental improvements in attention reorienting, the neural correlates underlying these changes are poorly understood, particularly with respect to childhood and adolescence. In adults, attention orienting and reorienting are supported by distinct frontoparietal networks, including the ventral attention network (VAN; temporoparietal junction, ventral frontal cortex, and occipital; Krall et al., 2015) and the dorsal attention network (DAN; bilateral superior parietal lobes, intraparietal sulci, occipital cortices, and frontal eye fields; Corbetta et al., 2008; Fan et al., 2005; Konrad et al., 2005). Specifically, VAN is thought to support “bottom-up” attentional processing, whereby an unexpected stimulus redirects attention elsewhere (i.e., reorienting). Conversely, DAN is characterized by “top-down” attention requiring goal-directed, sustained focus on a particular stimulus (i.e., orienting; Vossel et al., 2014). Prior fMRI studies with adults suggest that VAN regions are consistently recruited during attentional reorienting and a few studies have demonstrated marked disruptions in recruitment and connectivity patterns of VAN in those with attention deficits (e.g., autism, depression, anxiety, and ADHD; Fitzgerald et al., 2015; Helenius et al., 2011; Petersen and Posner, 2012; Sylvester et al., 2013; Yerys et al., 2019). Regarding development, some have suggested that there are age-related changes in connectivity patterns of attention networks (Rohr et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2022), such that younger children tend to rely more heavily on “bottom-up” compared to “top-down” networks, which likely indicates that regions involved in reorienting undergo a protracted developmental course (Farrant and Uddin, 2015). It should be noted that existing studies have frequently relied on task-free fMRI (i.e., resting-state), which limits interpretations about the underlying neural dynamics of attentional reorienting. Moreover, prior research has largely focused on younger populations (Molloy and Saygin, 2022, Onofrj et al., 2022, Sylvester et al., 2022) or comparing children to adult samples (Farrant and Uddin, 2015). Thus, there is a pressing need for neuroimaging studies to characterize a wider swath of development (i.e., childhood through adolescence) in the context of attention reorienting tasks.

More recently, studies using magnetoencephalography (MEG) have highlighted the importance of the neural oscillatory dynamics serving attentional reorienting. MEG is an optimal modality to probe multispectral responses of neural networks underlying attention reorienting, as it offers high temporal (i.e., millisecond) and spatial precision (i.e., sub-centimeter). To date, MEG studies using the Posner cueing paradigm have exclusively focused on adults. These studies have shown stronger oscillatory activity in alpha and beta bands, as well as increases in theta activity in VAN and DAN regions (Arif et al., 2020a, Arif et al., 2020b, Proskovec et al., 2018a, Spooner et al., 2020). Specifically, Proskovec and colleagues (2018) found greater theta synchronization during attention reorienting in the prefrontal cortex, frontal eye fields, and primary visual cortices, stronger alpha oscillations in superior parietal, cuneus, and lateral occipital cortex (LOC), and stronger beta oscillations in LOC and the intraparietal sulcus. Other studies of healthy adults have shown systematic increases in theta activity in bilateral inferior frontal gyrus during attention reorienting (e.g., Spooner et al., 2020). Individual differences in attention reorienting behavior and neural oscillatory dynamics have also been reported in MEG studies with special populations, including aging samples (Arif et al., 2020a), cannabis users (Springer et al., 2023), and individuals living with HIV (Arif et al., 2020c). Altogether, MEG studies using very similar paradigms in healthy adults have suggested that attentional reorienting is a highly dynamic process that involves regions in the frontal, parietal, and occipital cortices, including those previously implicated in the DAN and VAN. However, these neural dynamics have yet to be characterized in a developmental population using MEG.

The present study fills this gap by examining the impact of development (i.e., age) on the neural oscillatory dynamics serving attentional reorienting in a sample of typically developing youths (6–14 years old). Participants completed a Posner-cueing paradigm during an MEG recording to probe the neural dynamics underlying attentional orienting and reorienting. We hypothesized that there would be behavioral effects of attention reorienting (i.e., a “validity effect” in task accuracy and RT), and that theta and alpha oscillations across a distributed frontoparietal network would be observed during active attentional reorienting, as in the prior adult MEG literature. Critically, we expected age-related effects in the neural oscillatory dynamics serving attentional reorienting, given the known protracted developmental trajectory of higher-order attention processing (Lynn and Amso, 2021). Finally, considering the known associations between validity effects and neurodevelopmental disorders, we examined whether oscillatory dynamics serving attentional reorienting related to attentionally-based symptomology.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

The current study included a sample of 118 typically developing children and adolescents ages 6–14 years (Mage = 9.89 years, SD = 2.52; 54 females) who were recruited locally and screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria over the phone. Inclusion criteria were as follows: English as a primary language, ages 6–14 years of age, and usable MEG data. Exclusion criteria included any medical illness affecting CNS function, psychiatric or neurological disorder, history of head trauma, current substance use, and the standard exclusion criteria related to MEG acquisition (e.g., dental braces, metal implants, and/or any type of ferromagnetic implanted material). Prior to participating in the study, parents of the child participants signed informed consent forms, and child participants provided assent following the guidelines of the local Institutional Review Board, which reviewed and approved the study protocol.

2.2. Experimental paradigm

A modified Posner cued-attention paradigm was administered during the MEG recording (Fig. 1; Petersen and Posner, 2012, Posner, 1980). Participants were seated in a nonmagnetic chair within a magnetically shielded room to perform the task. Participants were instructed to attend to a centrally-located fixation crosshair throughout the task. Each trial began with the presentation of only the crosshair for 1750 ms ( ± 250 ms). Next, a green bar (i.e., the cue) appeared for 100 ms, presented for an equal number of trials on either the left or right of the crosshair. Two-hundred ms after the cue disappeared (i.e., 300 ms after cue onset), the target stimulus appeared on either the left or right side of the crosshair for 1200 ms. The target was comprised of a box with an opening on either the top or bottom (50% of the trials) and participants were instructed to respond as to the location of the opening (top = right middle finger; bottom = right index finger). Each target type (opening at top or bottom) appeared an equal number of times, and the target appeared an equal number of times on the left and right sides of the crosshair. In valid trials, the cue was presented on the same side as the upcoming target, while in invalid trials, the cue was presented on the opposite side as the target. Trials were pseudo-randomized such that no more than three of the same target responses, condition, or target/cue laterality combinations occurred in succession, and each condition appeared 100 times (200 total trials). Thus, each trial lasted 3250 ms (+/- 250 ms) and the total task run time was 11 min, including a 30 s break near the midpoint.

Fig. 1.

Posner cueing task and behavioral results. (a) A fixation cross was presented for 1750 ( ± 250) ms, followed by a cue (green bar) presented in the left or right visual hemifield for 100 ms. The target stimulus (box with opening) appeared 200 ms later in either the left or right visual hemifield for 1200 ms. Participants responded with a button press as to whether the opening was on the bottom or top of the target box. (b) The main effect of task condition reaction time is shown with condition, invalid (left) and valid (right), shown on the x-axis and mean reaction time (ms) on the y-axis. Participants exhibited a validity effect whereby they responded significantly slower to invalid compared to valid trials. (c) The main effect of task condition on mean accuracy is shown with condition on the x-axis and mean accuracy (%) on the y-axis. Participants exhibited a validity effect whereby they performed significantly worse on invalid compared to valid trials. (d) A significant interaction between age and validity reaction time is shown, with participant age (years) on the x-axis and validity reaction time (invalid – valid) on the y-axis. The main effect of age (not shown) was superseded by an age x condition interaction such that with increasing age the validity effect became significantly weaker (p < .05). (e) The non-significant interaction between age and validity accuracy (invalid – valid) is shown, with participant age on the x-axis and validity accuracy on the y-axis. A significant main effect of age (not shown) was not superseded by an age x condition interaction. ***p < .001, **p < .01.

2.3. Independent attention measure

The Conners 3rd Edition Short Form (Conners, 2008) is a 45-item scale designed to assess attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in youth 6 – 18 years old. In the questionnaire, parents were asked to rate statements about their child’s behavior in the past month on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never, seldom) to 3 (very often, very frequently). The Conners has good psychometric properties, with excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77 −0.97) and test-retest reliability (Pearson’s r = 0.71 −0.98). It was expected that youths’ attention problems (i.e., inattention and impulsivity/hyperactivity subscales) would covary with neural functioning during attentional reorientation. Raw scores from the inattention and impulsivity/hyperactivity subscales were used in the current analyses. These scores were evaluated for violations of normality (i.e., skewness and kurtosis), of which there were none (inattention: skew = 0.05, kurtosis = −1.45; hyperactivity/impulsivity: skew = 0.93, kurtosis = 0.90).

2.4. MEG and MRI data acquisition

All recordings were conducted in a one‐layer magnetically shielded room with active shielding engaged for environmental noise compensation. A 306-sensor Elekta/MEGIN MEG system (Helsinki, Finland), equipped with 204 planar gradiometers and 102 magnetometers, was used to sample neuromagnetic responses continuously at 1 kHz with an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1 – 330 Hz. Participants were seated in a custom-made nonmagnetic chair, with their heads positioned within the sensor array. Participants were monitored by a real-time audio-video feed from inside the shielded room throughout MEG acquisition. MEG data from each participant were individually corrected for head motion and subjected to noise reduction using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension (Taulu et al., 2005, Taulu and Simola, 2006).

Structural T1-weighted MR images were acquired using a Siemens Prisma 3 T MRI scanner with a 32-channel head coil and a 3D MP-RAGE sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2400 ms; TE = 2.05 ms; flip angle = 8°; FOV = 256 mm; slice thickness = 1 mm; voxel size = 1 mm3.

2.5. Structural processing and MEG co-registration

Prior to the MEG recording, four coils were attached to the subject's head and localized, together with the three fiducial points and scalp surface, with a 3D digitizer (Fastrak 3SF0002; Polhemus Navigator Sciences, Colchester, VT). Once the subject was positioned for MEG recording, an electric current with a unique frequency label (e.g., 322 Hz) was fed to each of the coils. This induced a measurable magnetic field and allowed each coil to be localized in reference to the sensors throughout the recording session. MEG measurements were transformed into a common coordinate system since all coil locations were known with respect to the individuals’ head coordinates. With this coordinate system, each participant's MEG data were co-registered with their structural T1–weighted neuroanatomical data using the fiducial points as landmarks prior to source space analyses using Brain Electrical Source Analysis (BESA) MRI (Version 2.0; BESA GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany). Following source analysis (i.e., beamforming), each subject’s functional MEG images were also transformed into standardized space with the same transformation applied to the structural MRI data and spatially resampled.

2.6. MEG preprocessing, time–frequency transformation, and sensor-level statistics

Cardiac and ocular artifacts (e.g., blinks, eye movement) were removed from the data using signal‐space projection (SSP) and were accounted for during source reconstruction (Uusitalo and Ilmoniemi, 1997). MEG data were then analyzed with respect to the attentional cue to evaluate the oscillatory dynamics associated with attentional reorientation. To evaluate the higher-order responses involved in attentional reorientation, the continuous magnetic time series was divided into 3000 ms epochs. Given our task and epoch design, the cue onset (i.e., the green line on the left or right of the fixation crosshair) was defined as 0 ms and the target onset (i.e., the open box to the left or right of the fixation crosshair) occurred at 300 ms. The baseline was defined as − 700 to − 100 ms preceding cue onset. Epochs containing artifacts were rejected based on a fixed threshold method, supplemented with visual inspection. Briefly, for each participant, the distribution of amplitude and gradient values was computed across all trials, and those trials containing the highest amplitude and/or gradient values relative to the full distribution were rejected by selecting a threshold that excluded extreme values. Importantly, these thresholds were set manually for each participant as interindividual differences in variables such as head size and proximity to the sensors strongly affect MEG signal amplitude. Additionally, we visually inspected the data to identify trials contaminated with other types of artifacts, such as those produced by muscle tension, and rejected such trials. Of 200 possible trials, an average of 134.51 (SD = 14.13) trials were used for further analysis. To ensure there were no systematic differences in the number of trials by participant age and/or sex, we computed an ANOVA, which revealed no main effects of participant age, sex, or their interaction on the number of trials (all p’s > 0.42).

Artifact‐free epochs were transformed into the time–frequency domain using complex demodulation (Kovach and Gander, 2016) with a resolution of 1 Hz and 50 ms, and the resulting spectral power estimations per sensor were averaged across all trials to generate time–frequency plots of mean spectral density. These sensor‐level data were then normalized with respect to the baseline power, which was calculated as the mean power per frequency bin between − 700 and − 100 ms prior to cue onset. A data-driven approach was used to select the time-frequency windows to be imaged, whereby a statistical analysis of the sensor-level spectrograms was performed across all trials (valid + invalid), gradiometers, and participants. Each data point (i.e., 1 Hz by 50 ms bin) in the spectrogram was initially evaluated using a mass univariate approach based on the general linear model. To reduce the risk of false positive results while maintaining reasonable sensitivity, a two‐stage procedure was followed to control for Type 1 error. In the first stage, paired‐sample t-tests against baseline were conducted on each data point and the output spectrogram of t values was thresholded at p < .05 to define time–frequency bins containing potentially significant oscillatory deviations across all participants. In the second stage, time–frequency bins that survived this threshold were clustered with temporally and/or spectrally neighboring bins that were also significant, and a cluster value was derived by summing all t values of all data points in the cluster. Nonparametric permutation testing was then used to derive a distribution of cluster values and the significance level of the observed clusters (from stage one) were tested directly using this distribution (Ernst, 2004, Maris and Oostenveld, 2007). For each comparison, 1000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values. Based on these analyses, only the time–frequency windows that contained significant oscillatory events across all trials were subjected to the beamforming (i.e., imaging) analysis.

2.7. MEG source imaging and source-level statistics

Cortical regions were imaged through the dynamic imaging of a coherent sources (DICS) beamformer (Gross et al., 2001), which applied spatial filters to time–frequency domain sensor data to calculate voxel‐wise source power for the entire brain volume. Following convention, the source power in these beamformed images was normalized per participant using a separately averaged pre-stimulus period (i.e., baseline) of equal duration and bandwidth to that of the active period of interest (Hillebrand et al., 2005). Such images are typically referred to as pseudo‐t maps, with units (pseudo‐t) that reflect noise‐normalized power differences (i.e., active vs. passive) per voxel. MEG preprocessing and imaging used the BESA (version 7.0) software.

Normalized source power was computed for the selected time–frequency bands over the entire brain volume per participant at 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm resolution. Each participant's functional images were transformed into standardized space using the transform that was previously applied to the structural images and then spatially resampled. The resulting 3D maps of brain activity were first averaged across participants and both conditions (i.e., grand average maps) to assess the anatomical basis of the significant oscillatory responses identified through the sensor‐level analysis. Next, subtraction maps were computed (i.e., invalid – valid) per participant and then averaged across all participants to examine activity related to the validity effect. Finally, for the whole-brain statistical analyses, condition-wise maps were submitted to a repeated-measures ANCOVA model in the Multivariate and Repeated Measures (MRM) toolbox in SPM12 (McFarquhar et al., 2016). Specifically, voxel-wise models were computed to evaluate the main effects of age and condition (invalid and valid), as well as their interactions, in each of the frequency bands identified in the sensor-level analyses. All maps were corrected using a statistical threshold of p < .001 and a cluster threshold of k = 10.

2.8. Brain-behavior associations

Links between neural validity effects and behavior were evaluated with a two-pronged approach (i.e., task behavior and exploratory analyses). First, in spectrally-specific regions with a validity effect, we computed correlations between peak activity and both accuracy and RT validity effects from the task. Second, in a set of exploratory analyses, we computed whole-brain correlations (corrected at p < .001, cluster threshold k = 10) between validity effect maps (invalid minus valid) and the inattention and impulsivity/reactivity symptom severity subscales from the Conners Scale (Conners, 2008). These analyses allowed us to evaluate whether neural activity serving attentional reorientation corresponded with real-world behaviors relevant to attention dysfunction.

3. Results

Of the 118 participants, three were excluded due to poor task performance and 35 were excluded due to missing or artifactual MEG data, resulting in a final sample of 80 participants (see Table 1 for demographic information and attrition analyses).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics & Attrition.

| Variable | Final Sample (n = 80) |

Excluded Participants (n = 38) |

Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M(SD), range) | 10.40 (2.42), 6.07–14.49 | 8.81 (2.41), 6.07–13.88 | t(116) = 3.33, p = .001 |

| Sex (F:M) | 37:43 | 16:22 | χ2(1, n = 118) = 0.18, p = .67 |

| Race (W:B:A:AI/AN:M:N) | 69:1:1:0:8:1 | 35:0:0:0:3:0 | χ2(1, n = 118) = 1.16, p = .76 |

| Ethnicity (L:NL:N) | 1:78:1 | 37:1:0 | χ2(1, n = 118) = 0.29, p = .59 |

| Inattention | 3.19(2.34), 0 – 8 | 2.95(2.44), 0 – 13 | t(116) = 0.51, p = .61 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 4.54(3.59), 0 – 17 | 5.66(3.98), 0 – 17 | t(116) = 1.53, p = .13 |

Note. Age is in years, and all other metrics are counts; F = female, M = male; W = white, B = Black, A = Asian, AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native, M = Multiracial, N = Not reported; L = Latinx, NL = Non-Latinx, N = Not reported. Raw inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity subscale scores were derived from the Conners scale. To evaluate attrition, potential demographic differences were based upon missingness; χ2 analyses were conducted for sex, race, and ethnicity, and independent samples t-tests were conducted for age, inattention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity scores.

3.1. Behavioral analysis

Participants performed well on the task, with an average accuracy of 86.98% (SD = 8.23) for valid trials and 83.88% (SD = 8.86) for invalid trials. To assess whether there was a behavioral effect of attention reorientation, we computed separate repeated-measures ANOVAs for mean accuracy and RT with effects of condition (invalid and valid), age, and their interactions (Fig. 1b-e). Note that RT was computed relative to target onset, which occurred 300 ms after the start of the trial. The ANOVA results for task accuracy revealed a main effect of condition (F(1,78) = 7.94, p < .01, η2 = .09), whereby participants performed significantly better on the valid compared to invalid trials. There was also a main effect of age (F(1,78) = 22.96, p < .001, η2 = .23) such that accuracy improved with increasing age. The interaction between task condition and age was not significant, F(1,78) = 1.56, p = .22, η2 = .02. The ANOVA results for RT revealed a main effect of condition (F(1,78) = 28.66, p < .001, η2 = .27) whereby participants were significantly faster in the valid compared to invalid condition (Mvalid = 735.15 ms, SD= 183.74 ms; Minvalid = 801.03 ms, SD = 188.27 ms). There was also a main effect of age whereby participants responded faster with increasing age, F(1,78) = 45.17, p < .001, η2 = .37, but the main effects were superseded by an interaction between condition and age, F(1,78) = 5.48, p = .02, η2 = .07. To decompose this interaction, we computed the mean validity effect for each participant (invalid RT – valid RT; M = 65.88 ms, SD = 46.23 ms) and correlated these values with participant age. Age and the validity RT effect were significantly negatively correlated, which suggests that with increasing age, participants exhibited a smaller validity effect (i.e., reorientation cost), r(78) = −0.29, p = .01.

3.2. Sensor-level analysis

Robust theta (3–7 Hz) and alpha-beta (10–24 Hz) responses were observed following the target onset. Briefly, significant theta activity was observed from approximately 125 ms after the cue onset to around 1500 ms, with the most robust target-related response occurring from 400 to 950 ms. Neural activity following target onset in the alpha-beta range was seen from 500 to 950 ms (p < .001, corrected; Fig. 2). Although a strong theta response was seen immediately following the cue onset, the current set of analyses were specifically intended to evaluate neural oscillatory dynamics serving attention reorienting processes (i.e., following the presentation of invalidly-cued compared to validly-cued target). Thus, we focused on the time window following target onset for all imaging analyses.

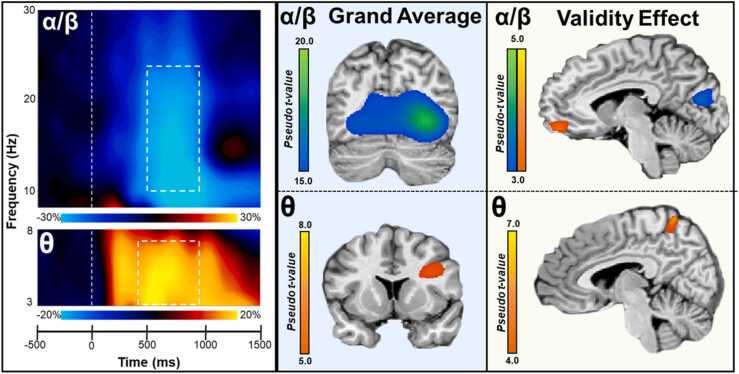

Fig. 2.

Sensor level time frequency analysis. (left) Each spectrogram was averaged across all the trials and all participants. Time (ms) is displayed on the x-axis with 0 ms defined as cue onset, while frequency (Hz) is shown on the y-axis. Power (%) is shown relative to the baseline period (−700 to −100 ms) and is represented by the color bar beneath each spectrogram. The top spectrogram displays alpha-beta and the bottom spectrogram shows the theta frequency response. Permutation-corrected statistical analyses indicated two time-frequency bins with significant responses (p < .05, corrected) relative to baseline (marked by white dotted boxes). A strong decrease in alpha-beta (10–24 Hz; top) was observed after target onset from 500 to 950 ms. Additionally, a strong increase in theta (3–7 Hz; bottom) activity occurred following cue onset and during target processing from 400 to 950 ms. The statistical analyses included all gradiometers; for visualization, sensors clearly showing the response (i.e., MEG2313 for alpha-beta, and MEG0232 for theta) are displayed. (middle) Grand average beamformer images (pseudo-t) for each oscillatory response (alpha-beta (top) and theta (bottom)). Each image shows the average response from all participants and all conditions (valid and invalid). (right) Validity effect (invalid minus valid) beamformer images (pseudo-t) for each oscillatory response are shown with alpha-beta on top and theta below. Each image shows the subtraction map averaged across all participants. Alpha-beta validity maps showed responses in left medial orbitofrontal cortex and bilateral cuneus, peaking in the right hemisphere. Subtraction maps in theta yielded a response in the right precuneus.

3.3. Beamformer analysis

To identify the brain regions producing the significant sensor-level oscillatory activity, the alpha-beta and theta responses were imaged using a beamformer. Grand-averaged maps showing the overall response patterns for both conditions, as well as the validity effect maps computed by subtracting the conditional maps (i.e., invalid minus valid), are shown in Fig. 2. Briefly, across conditions, oscillatory responses in the alpha-beta band were found within bilateral occipital cortices, while theta responses were in the right inferior frontal cortices. Alpha-beta validity effects were found in the left orbitofrontal cortex and bilateral cuneus and in the right precuneus in the theta band. Next, individual beamformer images of each oscillatory response were input into a voxel-wise repeated-measures ANCOVA to examine the main effects of participant age, task condition (invalid and valid), and their interactions.

3.3.1. Theta oscillatory activity

Our results revealed main effects of age in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (DLPFC), right superior frontal gyrus (SFG), right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and the right ventromedial PFC (vmPFC; p < .001; Fig. 3). In all four regions, increasing age was associated with stronger theta oscillations. There were no significant main effects of condition nor an interaction.

Fig. 3.

Theta oscillations increase with development. (a-d) Whole-brain main effects of age within the theta band (3–7 hz) were detected in four regions: a) right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (PFC), b) right superior frontal gyrus, c) right inferior frontal gyrus, and d) right ventromedial PFC. In each region, stronger increases from baseline in theta activity were found with increasing age. Age is shown on the x-axis and theta pseudo t-values are shown on the y-axis. All statistical maps are shown at p < .001 corrected.

3.3.2. Alpha-beta oscillatory activity

We detected main effects of age and condition, which were not superseded by an interaction. For the main effect of age, stronger alpha-beta oscillations (i.e., more negative) with increasing age were found in the left primary motor cortex (p < .001; Fig. 4a). The main effect of condition (i.e., validity effect) indicated stronger alpha-beta oscillations in the invalid relative to valid condition in the right cuneus (p < .001; Fig. 4b). In contrast, a “reverse” validity effect (i.e., stronger alpha-beta oscillations in the valid relative to invalid condition) was observed in the right cerebellum (p < .001; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Alpha-beta effects. a) A whole-brain main effect of age was found in the left motor cortex, such that alpha-beta (10–24 hz) oscillations became stronger (i.e., more negative) with increasing age. Age is shown on the x-axis, with alpha-beta pseudo-t values on the y-axis. b) A whole-brain main effect of condition (i.e., validity effect) was found within the right cuneus (left) and the right cerebellar cortices (right) in the alpha-beta band. In the right cuneus, participants exhibited stronger alpha-beta oscillations in the invalid relative to valid condition, whereas the opposite pattern was observed in the right cerebellum. Each region is shown on the x-axis with alpha-beta pseudo-t values on the y-axis. All statistical maps were thresholded at p < .001 corrected.

3.4. Brain-behavior associations

Whole-brain correlations between the theta validity effect maps (invalid – valid) and the Conners impulsivity/hyperactivity symptom severity scale revealed significant clusters of oscillatory activity within the right inferior temporal gyrus and left superior temporal sulcus (STS; p < .001, Fig. 5). In both regions, stronger theta oscillations during attention reorienting (validity effect) were related to fewer symptoms. There were no significant associations between the theta validity effect maps and the inattention subscale. In addition, in the alpha-beta band, neither inattention nor impulsivity/hyperactivity related to validity effect whole-brain maps. Finally, there were no significant associations between the task behavioral validity effects (i.e., validity accuracy and RT) and the validity effect maps for either frequency band.

Fig. 5.

Associations between theta neural validity effects and behavior. Whole-brain correlations between the theta validity effect (invalid – valid) and impulsivity/hyperactivity symptoms from the Connors scale for ADHD symptoms were computed. Significant correlations within the right inferior temporal gyrus (left) and the left superior temporal sulcus (right) suggest that a larger theta validity effect is related to lower levels of impulsivity/hyperactivity symptoms (p < .001 corrected).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the neural dynamics underlying attentional reorienting across a critical developmental window (6–14 years old) that included the pubertal transition. Our advanced oscillatory analyses revealed that during attention reorienting, typically-developing youth recruit a distributed network of regions in the fronto-parietal network, as well as higher-order visual regions within the theta (3–7 Hz) and alpha-beta (10–24 Hz) frequency bands. These neural regions largely corroborate those reported in existing adult neuroimaging literature during comparable attention paradigms, including studies using fMRI (Amso and Scerif, 2015, Konrad et al., 2005) and MEG modalities (Proskovec et al., 2018a, Spooner et al., 2020). In addition, theta oscillatory activity during attention processing increased with age across a right-lateralized network of prefrontal regions, which are known to undergo extensive functional development well into adolescence to support flexible behavior in response to unexpected environmental stimuli during adulthood (e.g., attentional reorienting; Farrant and Uddin, 2015). Age-related effects also emerged in the alpha-beta range, with participants exhibiting stronger oscillations in the motor cortex with increasing age, consistent with prior developmental research showing similar age-related patterns during tasks requiring a motor response (Heinrichs-Graham et al., 2018, Kurz et al., 2016). In addition, we observed an alpha-beta neural validity effect in the right cuneus and a reverse validity effect in the right cerebellum. Finally, we uncovered whole-brain associations such that a greater theta validity effect in the right inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and the left superior temporal sulcus (STS) related to lower levels of impulsivity and hyperactivity on the Conners ADHD scale. Below, we discuss how these findings expand on the broader developmental literature examining higher-order attention networks.

Our most important findings were the age-related changes in theta and alpha-beta oscillations during attention processing. Specifically, theta oscillations became stronger with increasing age in the right DLPFC, right SFG, right IFG, and right vmPFC, which suggests greater recruitment of a network of prefrontal regions underlying attention. These regions are often considered nodes of the dorsal and ventral attention networks (DAN, i.e., right SFG and right DLPFC; VAN, i.e., right vmPFC, right IFG), which support visuospatial coordination of orienting and reorienting behaviors, respectively (Vossel et al., 2014). These findings are largely consistent with prior work, documenting the key role that frontal theta plays in the allocation of spatial attention from toddlerhood into adulthood (Conejero et al., 2018, Rajan et al., 2019, Spooner et al., 2020). For example, two previous MEG studies in healthy adults using a similar paradigm also reported frontal theta in right (Proskovec et al., 2018a) and bilateral IFG (Spooner et al., 2020, Springer et al., 2023). Moreover, these results are consistent with a growing human and non-human primate literature suggesting increases in cortical oscillations within the theta range during spatial attention, particularly when attention is shifting to a different location, as in the invalidly-cued trials examined here (Gaillard and Ben Hamed, 2022). The distinction between prior adult work and the current findings are two-fold; first, we did not observe conditional sensitivity (i.e., a validity effect) as has been reported in frontal theta in previous adult studies (Arif et al., 2020b, Proskovec et al., 2018a, Spooner et al., 2020, Springer et al., 2023), suggesting that there is likely developmental fine-tuning of how these cortical rhythms respond to attentional demands. Moreover, the lack of a validity effect may also reflect the highly interactive nature of VAN and DAN networks that allow for flexible engagement of bottom-up and top-down attentional mechanisms (Vossel et al., 2014). Second, adult work has reported these effects specifically in IFG, and not the additional frontal regions reported here, suggesting that during development, a larger network of regions may be necessary to accomplish the same goal-directed behaviors. These interpretations will need to be evaluated in future work specifically comparing adults and youth with respect to whether frontal theta during attentional reorienting shifts with age. An alternative explanation for the lack of conditional specificity in the frontal theta findings could be that older participants had more efficient endogenous engagement overall. That is, it’s possible that completing a longer task (i.e., ∼11 min) required more effortful engagement, irrespective of condition, which may have been more difficult for the younger compared to older participants. Altogether, this work corroborates and extends previous literature by demonstrating that frontal cortices generate theta oscillations during attention and that these cortical rhythms are undergoing continued refinement during development such that increasing frontal theta across age may be an important feature of the development of both DAN and VAN.

Alpha-beta also exhibited expected age-related changes in motor cortex, which converges with prior developmental and lifespan research documenting similar age-related increases in beta and/or alpha-beta oscillations in primary motor cortex directly preceding a motor response (Heinrichs-Graham et al., 2018, Kurz et al., 2016). Thus, the present study adds additional support for previous work documenting these developmental effects underlying basic motor processing. Of particular interest to the current study, an alpha-beta validity effect was uncovered in the right cuneus and a reverse validity effect in the right cerebellar cortices. The stronger alpha-beta oscillatory activity (i.e., more negative) for invalid compared to valid attentional cues in the right cuneus, specifically, supports prior MEG work in healthy adults with similar findings in the alpha range (Arif et al., 2020b, Proskovec et al., 2018a). Moreover, in another higher-order attention task, a previous developmental MEG study reported increased alpha-beta oscillatory activity in the right cuneus (Taylor et al., 2021). These results are largely unsurprising, given the known role of alpha and alpha-beta responses in automatic attentional capture and attentional shifting in complex visual environments (Jia et al., 2022). A growing body of work has demonstrated that alpha oscillations emanating from visual cortices likely facilitate the suppression of irrelevant information in the face of environmental distractors, in order to flexibly orient attention (Embury et al., 2019, Klimesch et al., 2007, Petro et al., 2019, Proskovec et al., 2019, Proskovec et al., 2018b, van Diepen et al., 2016). Moreover, the cuneus has long been implicated in the deployment of spatial attention, particularly during involuntary attention (for review, Dugué et al., 2020). The cerebellar finding is consistent with prior MEG work with healthy adults showing strong decreases in the alpha range within the cerebellum during higher-order attention (McDermott et al., 2017). Moreover, functioning of the ipsilateral cerebellum has historically been implicated in ocularmotor coordination (Vercher and Gauthier, 1988), with direct connections to motor and premotor cortical regions, as well as prefrontal and posterior parietal cortex (Dum and Strick, 2003, Thach, 1975). In other words, alpha-beta activity within cerebellar regions similar to those observed here supports literature showing that cerebellar projections to cortex subserve volitional motor responses and behaviors requiring rapid visual attention (Schweizer et al., 2007). Moreover, the finding that alpha-beta oscillations were stronger for valid compared to invalid trials in regions of the cerebellum supports existing evidence that these cortices are highly sensitive to cued attention and paradigms requiring attentional control, as in orienting to a validly-cued stimulus (Habas, 2010). Altogether, these results suggest that children and adolescents exhibit alpha-beta oscillations across a comparable network of regions in the face of attentional demands to what has been reported in previous adult literature, but that there are developmental differences in how these regions are engaged which will need to be further probed in future work.

In terms of brain-behavior associations, whole-brain correlations revealed that greater theta validity effects in the right ITG and left STS corresponded to lower impulsivity/hyperactivity symptoms. This points to the possibility that theta oscillations in these regions supports adaptive attentional behaviors outside the laboratory. Further, these results provide support for existing animal physiology studies documenting the sensitivity of the ITG in “decoding” objects in the environment that are engaged via bottom-up attentional mechanisms (Zhang et al., 2011). Models of visuo-spatial attention highlight the IT cortex as a core component of the feedback and feedforward organization supporting attentional orienting behavior (Amso and Scerif, 2015). Recently, it has been suggested that the STS may be a core region of a broader temporal attention network (TAN), and that the STS is pivotal in propagating information between early visual regions and prefrontal cortex during visual attention tasks (Ramezanpour and Fallah, 2022). Clinically, attentional reorienting difficulties in children with ADHD compared to controls during the Posner cueing task have been documented (Caldani et al., 2020), as has reduced theta activity in EEG paradigms (Michelini et al., 2022). With respect to the results reported here, this suggests that even subclinically elevated impulsivity/hyperactivity symptoms may be related to theta oscillations in areas involved in attentional reorienting.

Before closing, it is crucial to note the limitations of this study. First, the current study employed a cross-sectional design, as opposed to a longitudinal study. Future work would benefit from the use of a longitudinal design as it would better capture individual-level trajectories of changes in neural dynamics serving attentional reorienting. In addition to using longitudinal study designs, it may be that other metrics of development (e.g., hormonal changes) would help to better characterize attentional network development. For example, puberty is highly relevant to understanding changes in neural networks supporting flexible allocation of attention, and goal-directed behaviors more broadly (Crone and Dahl, 2012). Relatedly, it is also important to acknowledge that in our current design, youth ages 9 – 10 years were not recruited as part of this study in order to capture late childhood (i.e., 6 – 8 years) and early to mid-adolescence (i.e., 11 – 15 years). Future work would benefit from incorporating these ages, as individuals 9 – 10 years old are likely transitioning into the early stages of puberty. Finally, the present study used a whole-brain approach as a starting point of identifying specific clusters of neural activity related to attentional reorientation in youth, but future work would benefit from exploring dynamic functional connectivity among attention networks (e.g., VAN and DAN), as well as charting transitions in attentional mechanisms supporting reorienting skills.

5. Conclusion

In the first developmental MEG study of attentional reorienting, we found robust theta and alpha-beta oscillations during the Posner task in a sample of 6 – 14-year-olds. Consistent with prior EEG and fMRI studies, youth recruited a network of frontal-parietal and higher-order visual regions during attentional reorienting. Notably, this was specifically observed in the theta (3–7 Hz) and alpha-beta (10–24 Hz) frequency bands, which are thought to play central roles in flexible and successful allocation of attentional resources. Developmentally, stronger frontal theta oscillations corresponded with increasing age, which contributes to the growing literature on the key role of frontal theta in attention allocation. Moreover, theta validity effects were associated with clinically-relevant behaviors in regions implicated in visuospatial attention. Taken together, these results provide key insights into the spectral, temporal, and spatial organization of attentional allocation across a critical period of development.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-MH121101, R01-MH116782, and P20-GM144641 to TWW; R01-EB020407 and R01-MH118695 to VDC), the National Science Foundation (#1539067 to TWW, YPW, JMS, and VDC and #2112455 to VDC), and At Ease, USA. Funding agencies had no part in the study design or the writing of this report.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

The data used in this article will be made publicly available through the COINS framework at the completion of the study (https://coins.trendscenter.org/).

References

- Abundis-Gutiérrez A., Checa P., Castellanos C., Rosario Rueda M. Electrophysiological correlates of attention networks in childhood and early adulthood. Neuropsychologia. 2014;57:78–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amso D., Scerif G. The attentive brain: insights from developmental cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrn4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif Y., Spooner R.K., Wiesman A.I., Embury C.M., Proskovec A.L., Wilson T.W. Modulation of attention networks serving reorientation in healthy aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:12582. doi: 10.18632/aging.103515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif Y., Wiesman A.I., O’Neill J., Embury C., May P.E., Lew B.J., Schantell M.D., Fox H.S., Swindells S., Wilson T.W. The age-related trajectory of visual attention neural function is altered in adults living with HIV: A cross-sectional MEG study. EBioMedicine. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif Y., Wiesman A.I., O’Neill J., Embury C., May P.E., Lew B.J., Schantell M.D., Fox H.S., Swindells S., Wilson T.W. The age-related trajectory of visual attention neural function is altered in adults living with HIV: A cross-sectional MEG study. EBioMedicine. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldani S., Isel F., Septier M., Acquaviva E., Delorme R., Bucci M.P. Impairment in attention focus during the posner cognitive task in children with ADHD: an eye tracker study. Front. Pediatr. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Leite P., Bavelier D. Video game play, attention, and learning: how to shape the development of attention and influence learning? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2014;27:185–191. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conejero Á., Guerra S., Abundis-Gutiérrez A., Rueda M.R. Frontal theta activation associated with error detection in toddlers: influence of familial socioeconomic status. Dev. Sci. 2018;21 doi: 10.1111/desc.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners, K.C., 2008. Conners 3rd Edition. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Corbetta M., Patel G., Shulman G.L. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008;58:306–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone E.A., Dahl R.E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugué L., Merriam E.P., Heeger D.J., Carrasco M. Differential impact of endogenous and exogenous attention on activity in human visual cortex. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21274. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78172-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum R.P., Strick P.L. An unfolded map of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and its projections to the cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;89:634–639. doi: 10.1152/jn.00626.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embury C.M., Wiesman A.I., Proskovec A.L., Mills M.S., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wang Y.-P., Calhoun V.D., Stephen J.M., Wilson T.W. Neural dynamics of verbal working memory processing in children and adolescents. Neuroimage. 2019;185:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns J.T., Brodeur D.A. A developmental study of covert orienting to peripheral visual cues. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1989;48:171–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(89)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M.D. Permutation methods: a basis for exact inference. Stat. Sci. 2004:676–685. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., McCandliss B.D., Fossella J., Flombaum J.I., Posner M.I. The activation of attentional networks. NeuroImage. 2005;26:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant K., Uddin L.Q. Asymmetric development of dorsal and ventral attention networks in the human brain. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2015;12:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J., Johnson K., Kehoe E., Bokde A.L.W., Garavan H., Gallagher L., McGrath J. Disrupted functional connectivity in dorsal and ventral attention networks during attention orienting in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2015;8:136–152. doi: 10.1002/aur.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard C., Ben Hamed S. The neural bases of spatial attention and perceptual rhythms. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022;55:3209–3223. doi: 10.1111/ejn.15044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J., Kujala J., Hämäläinen M., Timmermann L., Schnitzler A., Salmelin R. Dynamic imaging of coherent sources: studying neural interactions in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:694–699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas C. Functional imaging of the deep cerebellar nuclei: a review. Cerebellum. 2010;9:22–28. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim S., Keil A. Developmental trajectories of regulating attentional selection over time. Front. Psychol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E., McDermott T.J., Mills M.S., Wiesman A.I., Wang Y.-P., Stephen J.M., Calhoun V.D., Wilson T.W. The lifespan trajectory of neural oscillatory activity in the motor system. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;30:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius P., Laasonen M., Hokkanen L., Paetau R., Niemivirta M. Impaired engagement of the ventral attentional pathway in ADHD. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:1889–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand A., Singh K.D., Holliday I.E., Furlong P.L., Barnes G.R. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum. brain Mapp. 2005;25:199–211. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iarocci G., Enns J.T., Randolph B., Burack J.A. The modulation of visual orienting reflexes across the lifespan. Dev. Sci. 2009;12:715–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Fan Y., Luo H. Alpha-band phase modulates bottom-up feature processing. Cereb. Cortex. 2022;32:1260–1268. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhab291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W., Sauseng P., Hanslmayr S. EEG alpha oscillations: The inhibition–timing hypothesis. Brain Res. Rev. 2007;53:63–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad K., Neufang S., Thiel C.M., Specht K., Hanisch C., Fan J., Herpertz-Dahlmann B., Fink G.R. Development of attentional networks: an fMRI study with children and adults. NeuroImage. 2005;28:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach C.K., Gander P.E. The demodulated band transform. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2016;261:135–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall S.C., Rottschy C., Oberwelland E., Bzdok D., Fox P.T., Eickhoff S.B., Fink G.R., Konrad K. The role of the right temporoparietal junction in attention and social interaction as revealed by ALE meta-analysis. Brain Struct. Funct. 2015;220:587–604. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz M.J., Proskovec A.L., Gehringer J.E., Becker K.M., Arpin D.J., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Developmental trajectory of beta cortical oscillatory activity during a knee motor task. Brain Topogr. 2016;29:824–833. doi: 10.1007/s10548-016-0500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq V., Siéroff E. Development of endogenous orienting of attention in school-age children. Child Neuropsychol. 2013;19:400–419. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2012.682568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F.C., Reeve R.A., Johnson K.A. A longitudinal analysis of the attention networks in 6- to 11-year-old children. Child Neuropsychol. 2018;24:145–165. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1235145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn A., Amso D. Attention along the cortical hierarchy: development matters. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1002/wcs.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E., Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG-and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;164:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott T.J., Wiesman A.I., Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Spatiotemporal oscillatory dynamics of visual selective attention during a flanker task. NeuroImage. 2017;156:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarquhar M., McKie S., Emsley R., Suckling J., Elliott R., Williams S. Multivariate and repeated measures (MRM): a new toolbox for dependent and multimodal group-level neuroimaging data. NeuroImage. 2016;132:373–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelini G., Salmastyan G., Vera J.D., Lenartowicz A. Event-related brain oscillations in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2022;174:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2022.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy M.F., Saygin Z.M. Individual variability in functional organization of the neonatal brain. NeuroImage. 2022;253 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenbaum K., Scerif G., Nobre A.C. Differential effects of salient visual events on memory-guided attention in adults and children. Child Dev. 2019;90:1369–1388. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onofrj V., Chiarelli A.M., Wise R., Colosimo C., Caulo M. Interaction of the salience network, ventral attention network, dorsal attention network and default mode network in neonates and early development of the bottom-up attention system. Brain Struct. Funct. 2022;227:1843–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00429-022-02477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S.E., Posner M.I. The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35:73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petro N.M., Thigpen N.N., Garcia S., Boylan M.R., Keil A. Pre-target alpha power predicts the speed of cued target discrimination. NeuroImage. 2019;189:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M.I. Orienting of attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M.I. Imaging attention networks. Neuroimage. 2012;61:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M.I. Orienting of attention: then and now. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2016;69:1864–1875. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2014.937446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M.I., Rueda M.R., Kanske P. Probing Mech. Atten. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wiesman A.I., McDermott T.J., Wilson T.W. Oscillatory dynamics in the dorsal and ventral attention networks during the reorienting of attention. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39:2177–2190. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Beta oscillatory dynamics in the prefrontal and superior temporal cortices predict spatial working memory performance. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8488. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26863-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Load modulates the alpha and beta oscillatory dynamics serving verbal working memory. Neuroimage. 2019;184:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan A., Siegel S.N., Liu Y., Bengson J., Mangun G.R., Ding M. Theta oscillations index frontal decision-making and mediate reciprocal frontal–parietal interactions in willed attention. Cereb. Cortex. 2019;29:2832–2843. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezanpour H., Fallah M. The role of temporal cortex in the control of attention. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.crneur.2022.100038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr C.S., Arora A., Cho I.Y.K., Katlariwala P., Dimond D., Dewey D., Bray S. Functional network integration and attention skills in young children. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;30:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerif G., Steele A. In: Progress in Brain Research, Gene Expression to Neurobiology and Behavior: Human Brain Development and Developmental Disorders. Braddick O., Atkinson J., Innocenti G.M., editors. Elsevier; 2011. Chapter 16 - Neurocognitive development of attention across genetic syndromes: Inspecting a disorder’s dynamics through the lens of another; pp. 285–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer T.A., Alexander M.P., Cusimano M., Stuss D.T. Fast and efficient visuotemporal attention requires the cerebellum. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:3068–3074. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooner R.K., Wiesman A.I., Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Prefrontal theta modulates sensorimotor gamma networks during the reorienting of attention. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020;41:520–529. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S.D., Spooner R.K., Schantell M., Arif Y., Frenzel M.R., Eastman J.A., Wilson T.W. Regular recreational Cannabis users exhibit altered neural oscillatory dynamics during attention reorientation. Psychol Med. 2023;53(4):1205–1214. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002671. Epub 2021 Sep 22. PMID: 34889178; PMCID: PMC9250753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C., Bavelier D. The role of selective attention on academic foundations: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci., Neurosci. Educ. 2012;2:S30–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester C.M., Barch D.M., Corbetta M., Power J.D., Schlaggar B.L., Luby J.L. Resting state functional connectivity of the ventral attention network in children with a history of depression or anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2013;52:1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.001. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester C.M., Kaplan S., Myers M.J., Gordon E.M., Schwarzlose R.F., Alexopoulos D., Nielsen A.N., Kenley J.K., Meyer D., Yu Q., Graham A.M., Fair D.A., Warner B.B., Barch D.M., Rogers C.E., Luby J.L., Petersen S.E., Smyser C.D. Network-specific selectivity of functional connections in the neonatal brain. Cereb. Cortex bhac202. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S., Simola J. Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in MEG measurements. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:1759–1768. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S., Simola J., Kajola M. Applications of the signal space separation method. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2005;53:3359–3372. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.K., Eastman J.A., Frenzel M.R., Embury C.M., Wang Y.-P., Calhoun V.D., Stephen J.M., Wilson T.W. Neural oscillations underlying selective attention follow sexually divergent developmental trajectories during adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2021;49 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach W.T. Timing of activity in cerebellar dentate nucleus and cerebral motor cortex during prompt volitional movement. Brain Res. 1975;88:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90387-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo M.A., Ilmoniemi R.J. Signal-space projection method for separating MEG or EEG into components. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1997;35:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02534144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diepen R.M., Miller L.M., Mazaheri A., Geng J.J. The role of alpha activity in spatial and feature-based attention. eNeuro. 2016;3 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0204-16.2016. ENEURO.0204-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercher J.-L., Gauthier G.M. Cerebellar involvement in the coordination control of the oculo-manual tracking system: effects of cerebellar dentate nucleus lesion. Exp. Brain Res. 1988;73:155–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00279669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S., Geng J.J., Fink G.R. Dorsal and ventral attention systems: distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. Neuroscientist. 2014;20:150–159. doi: 10.1177/1073858413494269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Guan H., Ma L., Luo J., Chu C., Hu M., Zhao G., Men W., Tan S., Gao J.-H., Qin S., He Y., Dong Q., Tao S. Learning to read may help promote attention by increasing the volume of the left middle frontal gyrus and enhancing its connectivity to the ventral attention network. Cereb. Cortex bhac206. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerys B.E., Tunç B., Satterthwaite T.D., Antezana L., Mosner M.G., Bertollo J.R., Guy L., Schultz R.T., Herrington J.D. Functional connectivity of frontoparietal and salience/ventral attention networks have independent associations with co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children with autism. Biol. Psychiatry.: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2019;4:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Meyers E.M., Bichot N.P., Serre T., Poggio T.A., Desimone R. Object decoding with attention in inferior temporal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article will be made publicly available through the COINS framework at the completion of the study (https://coins.trendscenter.org/).