Introduction

Morbihan disease or solid facial edema is a late-stage complication of rosacea. It is characterized by facial swelling for which other systemic causes must be ruled out and is frequently refractory to treatment.1 The pathogenesis is unclear, but it is proposed that recurrent inflammation (eg, rosacea and acne vulgaris) may disrupt the balance between lymphatic fluid production and drainage and that mast cells in the inflammatory infiltrate may lead to fibrosis.2,3 Here, we describe the workup and successful short-term treatment with bilateral upper portion of the eyelid blepharoplasty of a patient with severe Morbihan disease.

Case report

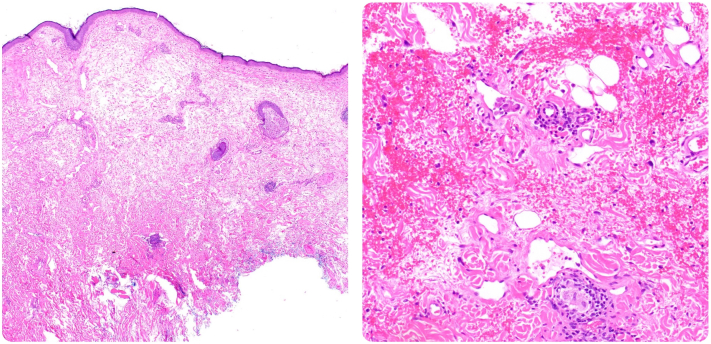

A 66-year-old man with acne vulgaris and rosacea on doxycycline presented as a new patient with 2 years of facial erythema and progressive swelling of the eyelids and forehead. He endorsed intermittent watery eyes and heavy eyelid pressure but denied pruritus or pain. He was otherwise healthy without personal or family history of blood clots. Malignancy screenings were up-to-date. The patient’s acne and rosacea had been recalcitrant to courses of prednisone and doxycycline. There were no other facial issues or treatments. Physical examination revealed symmetric nonpitting edema with overlying macular erythema of the bilateral eyelids, forehead, cheeks, nose, and ears. No alopecia of the eyebrows was noted. No rash was noted elsewhere, including on the hands, neck, trunk, and back. Differential diagnoses included dermatomyositis, cavernous sinus thrombi, superior vena cava syndrome, hypothyroidism, paraneoplastic facial swelling, and depositional disrders (eg, scleromyxedema). An extensive workup showed unremarkable complete blood cell count, thyroid stimulating hormone, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, antinuclear antibody, serum/urine protein electrophoresis, and IgG levels. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography did not show cavernous sinus thrombi. Endoscopy and patch testing were unremarkable. An outside biopsy reviewed did not show mucin deposition. Repeat biopsies of the upper portion of the eyelids showed a perifollicular and perivascular/perilymphatic lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate with extensive dermal lymphangiectasia, marked dermal edema, focal intravascular histiocytosis, and scattered perilymphatic granulomas, consistent with Morbihan variant of rosacea (Fig 1). There was no improvement despite treatment with isotretinoin. The patient was referred to oculoplastic surgery and underwent bilateral upper portion of the eyelid blepharoplasty. He experienced marked improvement in eyelid swelling, heavy eyelid sensation, and cosmesis. However, the patient’s symptoms recurred 7 months after surgery (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Histopathology of upper portion of the eyelid skin. Scanning microscopy shows dermal edema and lymphangiectasia with perivascular and periadnexal inflammation (left, hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: 4×). There are small perilymphatic granulomas (bottom right) and intralymphatic histiocytes (upper right) (hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: 20×).

Fig 2.

Clinical photographs. The patient’s initial presentiation of symmetric nonpitting edema with overlying macular erythema of the bilateral eyelids (left), compared with the patient’s marked improvement following bilateral upper portion of the eyelid blepharoplasty at 4 months after surgery (middle), and recurrence of disease 7 months after surgery (right).

Discussion

This case report emphasizes 2 important points about Morbihan disease: it is difficult to diagnose and it is often refractory to typical therapies.1,4 With regard to diagnosis, a thorough workup, including biopsy and clinicopathologic correlation, is recommended to assist in differentiating Morbihan disease from other systemic causes. As for treatment, this case suggests that oculoplastic surgery, such as blepharoplasty, offers a potential short-term therapeutic alternative for patients with recalcitrant Morbihan disease involving the eyelids.

We hypothesize that blepharoplasty initially causes significant scarring and contracture of the wound, which could temporarily ameliorate the facial edema by limiting the accumulation of edema. However, this outcome is short-lived because as the eyelid blood vessels reform over a period of months, the abnormal lymphatic vessels fail to properly drain the edema. This mechanism is similar to that involved in tetracycline injections as a potential sclerosing agent for improvement of festoons.5

Additionally, given that there is no known effective long-term treatment for Morbihan disease, it is important to consider optimal prevention strategies. As Morbihan disease is thought to be a late-stage complication of rosacea, it is important to treat early and monitor closely for signs of progression.6

In conclusion, blepharoplasty may be an effective short-term alternative for patients with recalcitrant Morbihan disease. More research is needed to better understand the transition from rosacea to Morbihan disease, which patients might be at higher risk, opportunites for disease prevention, and optimal long-term therapies.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Merola is a consultant and/or investigator for Merck, Abbvie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, UCB, Celgene, Sanofi, Regeneron, Arena, Sun Pharma, Biogen, Pfizer, EMD Sorono, Avotres and Leo Pharma. Author Woodbury, Drs Chen, Stagner, and Lee have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Boparai R.S., Levin A.M., Lelli G.J., Jr. Morbihan disease treatment: two case reports and a systematic literature review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(2):126–132. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilinc I., Gençoglan G., Inanir I., Dereli T. Solid facial edema of acne: failure of treatment with isotretinoin. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(5):503–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsch K., Schaller M. Combination of ultra-low-dose isotretinoin and antihistamines in treating Morbihan disease - a new long-term approach with excellent results and a minimum of side effects. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32(8):941–944. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1721417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donthi D., Nenow J., Samia A., Phillips C., Papalas J., Prenshaw K. Morbihan disease: a diagnostic dilemma: two cases with successful resolution. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/2050313X211023655. 2050313X211023655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chon B.H., Hwang C.J., Perry J.D. Long-term patient experience with tetracycline injections for festoons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(6):737e–743e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford G.H., Pelle M.T., James W.D. Rosacea: I. Etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(3):327–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]