ABSTRACT

The importance of gut microbiomes has become generally recognized in vector biology. This study addresses microbiome signatures in North American Triatoma species of public health significance (vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi) linked to their blood-feeding strategy and the natural habitat. To place the Triatoma-associated microbiomes within a complex evolutionary and ecological context, we sampled sympatric Triatoma populations, related predatory reduviids, unrelated ticks, and environmental material from vertebrate nests where these arthropods reside. Along with five Triatoma species, we have characterized microbiomes of five reduviids (Stenolemoides arizonensis, Ploiaria hirticornis, Zelus longipes, and two Reduvius species), a single soft tick species, Ornithodoros turicata, and environmental microbiomes from selected sites in Arizona, Texas, Florida, and Georgia. The microbiomes of predatory reduviids lack a shared core microbiota. As in triatomines, microbiome dissimilarities among species correlate with dominance of a single bacterial taxon. These include Rickettsia, Lactobacillus, “Candidatus Midichloria,” and Zymobacter, which are often accompanied by known symbiotic genera, i.e., Wolbachia, “Candidatus Lariskella,” Asaia, Gilliamella, and Burkholderia. We have further identified a compositional convergence of the analyzed microbiomes in regard to the host phylogenetic distance in both blood-feeding and predatory reduviids. While the microbiomes of the two reduviid species from the Emesinae family reflect their close relationship, the microbiomes of all Triatoma species repeatedly form a distinct monophyletic cluster highlighting their phylosymbiosis. Furthermore, based on environmental microbiome profiles and blood meal analysis, we propose three epidemiologically relevant and mutually interrelated bacterial sources for Triatoma microbiomes, i.e., host abiotic environment, host skin microbiome, and pathogens circulating in host blood.

IMPORTANCE This study places microbiomes of blood-feeding North American Triatoma vectors (Reduviidae) into a broader evolutionary and ecological context provided by related predatory assassin bugs (Reduviidae), another unrelated vector species (soft tick Ornithodoros turicata), and the environment these arthropods coinhabit. For both vectors, microbiome analyses suggest three interrelated sources of bacteria, i.e., the microbiome of vertebrate nests as their natural habitat, the vertebrate skin microbiome, and the pathobiome circulating in vertebrate blood. Despite an apparent influx of environment-associated bacteria into the arthropod microbiomes, Triatoma microbiomes retain their specificity, forming a distinct cluster that significantly differs from both predatory relatives and ecologically comparable ticks. Similarly, within the related predatory Reduviidae, we found the host phylogenetic distance to underlie microbiome similarities.

KEYWORDS: Triatoma, Reduviidae, Ornithodoros, microbiome, environment

INTRODUCTION

Insect species diversification has been primarily facilitated by the dietary niche expansion bound to insect physiological adaptation and the establishment of symbiotic interactions with bacteria (1, 2). Microbiomes of insects utilizing resource-limited niches (phloem, xylem, wood, or blood) are known to be dominated by specialized, evolutionarily old bacterial associates with biosynthetic capacities that complement the host metabolism to overcome the dietary limitations. While such symbionts may rise from taxonomically divergent groups even in closely related hosts due to frequent evolutionary replacements (3, 4), these dietary constraints have led to remarkable functional convergence. For instance, within blood-sucking Anoplura, symbionts from distant bacterial genera Lightella, Puchtella, Riesia, Sodalis, Neisseria, and Legionella exhibit parallel genome evolution resulting in retention of genes coding for riboflavin biosynthesis (5, 6). Within a broader frame of blood-feeding Metazoa, functional convergence was found among symbionts of unrelated insect groups and between insects and leeches (7) and was, to some extent, suggested for gut microbiomes of vampire bats and vampire finches (8).

While the majority of the approximately 7,000 Reduviidae species are comprised of hemolymphophagous assassin bugs preying on other invertebrates, the subfamily Triatominae, commonly known as kissing bugs and the vectors of Trypanosoma cruzi, converted to hematophagy on birds, mammals, and reptiles (9, 10). In some respects, the symbiosis of Triatominae (Reduviidae) resembles that of hematophagous vertebrates. Unlike tsetse flies, keds, lice, or bedbugs, Triatominae have not established specialized symbiosis during their evolution. They maintain relatively simple species-specific gut microbiomes that undergo remarkable ontogenetic development (11). Though there is not an ancient, universally shared microbiome among kissing bug species, kissing bugs in the genus Rhodnius do appear to have frequent associations with bacteria in the genus Rhodococcus (12), first identified as a symbiont by Wigglesworth (13). Experimental studies have provided some evidence that the association of Rhodnius prolixus and Rhodococcus rhodnii is somewhat specific, as even closely related Rhodococcus species from other kissing bugs cannot substitute for R. rhodnii (14).

Both hemolymphophagy and hematophagy are highly specialized feeding strategies on prey/host body liquids that differ in composition. Invertebrate hemolymph is seemingly easily digestible, and is a rich source of free lipids and free amino acids (15). Vertebrate blood as a food source poses major challenges of heme toxicity and insufficient B vitamin content (16). Based on our knowledge from other hematophagous systems, we hypothesize that the Triatominae dietary shift from hemolymph to blood should be reflected in their microbiome structure and/or function. We further expect to reveal sources of bacterial influx associated with the Triatoma natural habitat, i.e., host vertebrates and their nesting sites. In this study, we investigate microbiome signatures of five Triatoma species against the background of five species of hemolymphophagous assassin bugs. Another vector species, a soft tick, Ornithodoros turicata, was included in the study to provide a phylogenetically independent contrast to microbiomes of hematophagous species sharing the same habitat. The analyzed arthropods originate from sympatric populations collected from nests of small vertebrates, primarily the white-throated wood rat, Neotoma albigula, in the southern United States. Within this unique sample set, we track the environmental sources of bacteria and address possible taxonomic convergence between microbiomes of sympatric populations of kissing and assassin bugs, and between the two hematophagous vectors, kissing bugs and ticks.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Taxonomic determination and distribution of sampled arthropods.

In total, we have molecularly identified five species of Triatoma spp. (T. gerstaeckeri, n = 7; T. lecticularia, n = 12; T. protracta, n = 39; T. rubida, n = 46; T. sanguisuga, n = 6) and four species of assassin bugs (Stenolemoides arizonensis, n = 3; Ploiaria hirticornis, n = 10; Zelus longipes, n = 7; Reduvius sonoraensis, n = 2). For 15 assassin individuals from Las Cienegas National Conservation Area (LCNCA) (AZ), 16S rRNA Sanger sequences contained signals for both the assassin and its prey, and we thus relied on morphological determination to the genus Reduvius (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Most of the analyzed Neotoma nests housed Triatoma sp. (14/16) and O. turicata (12/16). While 10 nests allowed for comparisons between microbiomes of blood-feeding vectors, i.e., ticks and triatomines, two nests served for comparisons of predatory and blood-feeding Reduviidae. Another two nests contained some species from all three sample types, i.e., ticks, assassins, and triatomines. In addition, Zelus longipes (Harpactorinae) and Ploiaria hirticornis (Emesinae: Leistarchini) were found in two locations in Georgia not associated with Neotoma nests (Table S1, data sheet S1).

Quality of rRNA amplicon data.

The MiSeq runs resulted in 5,998,041 sequence pairs with successful merging and trimming of 3,278,636 pairs (54.66%) sharing a mean merged length of 404 bp and an average number of 7,514 reads per sample. The profiles of negative controls were utilized to identify contaminant operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (see Materials and Methods and Table S1, data sheet S4). The sequencing of the positive controls showed a bias against Rhodobacter and in favor of Staphylococcus species, but the overall frequencies of the sequenced taxa are consistent with their abundance in the input material and comparable across the control replicates (Fig. S2). OTUs (n = 4,777) were clustered from the entire data set, i.e., amplicons retrieved for 255 arthropods, related environmental material, and controls (Table S1, data sheet S5). For the 12S rRNA gene, used for determination of primary and secondary blood meal source (Table S1, data sheet S7), a total of 1,287,068 reads were retrieved within the arthropod data set with an average of 5,297 reads per sample.

Microbiomes of North American Triatoma kissing bugs.

The profiles of Triatoma microbiomes analyzed here concur with the characteristics previously published by our team (11). These include significant differences in taxonomic composition and diversity among different Triatoma species (Table S1, data sheets S8 to S10) which undergo an ontogenetic shift from a diverse microbiome to a very simple community dominated by a single bacterial genus (Fig. S3). Venn analyses confirmed Actinobacteria as the dominant phylum in Triatoma microbiomes with the genus Dietzia found in over 50% individuals of phylogenetically closely related T. rubida, T. lecticularia, and T. protracta. The same fraction of T. gerstaeckeri and T. sanguisuga individuals shared two actinobacterial genera, i.e., Pseudonocardia and Nocardioides (Table S1, data sheet S11).

Regardless of the phylogenetic relationships, T. gerstaeckeri, T. lecticularia, T. rubida, and T. sanguisuga shared two proteobacterial taxa, an Acinetobacter (OTU_17) and Serratia sp. (OTU_14, Table S1, data sheet S11). While we cannot currently assess their role in Triatoma microbiomes, it is worth noting that both taxa are commonly found in insects (17, 18) and in some cases provide profound advantages for their host. For instance, some Acinetobacter strains are associated with insect resistance to the insecticide cypermethrin (19), a pyrethroid used for control of insect pests (20–22). Serratia marcescens isolated from the Triatominae microbiome has negative effects on the survival and replication of Trypanosoma cruzi in the Rhodnius prolixus gut (23, 24). Notably, a number of other bacterial taxa are almost universally present in Triatoma species across the majority of individuals (≥80%), for instance, Staphylococcus, Massilia, Bacillus, Planococcus, and Streptomyces (Fig. 1). Most were previously reported in microbiomes of some Triatominae species (11, 25, 26). We elucidate the putative origins of these omnipresent taxa below, providing the evolutionary and ecological frame of this study.

FIG 1.

UpSet graph depicting microbiome intersections among different Triatoma species. The top bar chart stands for the cumulative number of OTUs identified for each Triatoma species. The colored plot indicates how much each intersection deviates from the expected size if species membership within the analyzed data set is random. The bacterial genera shared, in 0.5 fraction, by four or more species are listed.

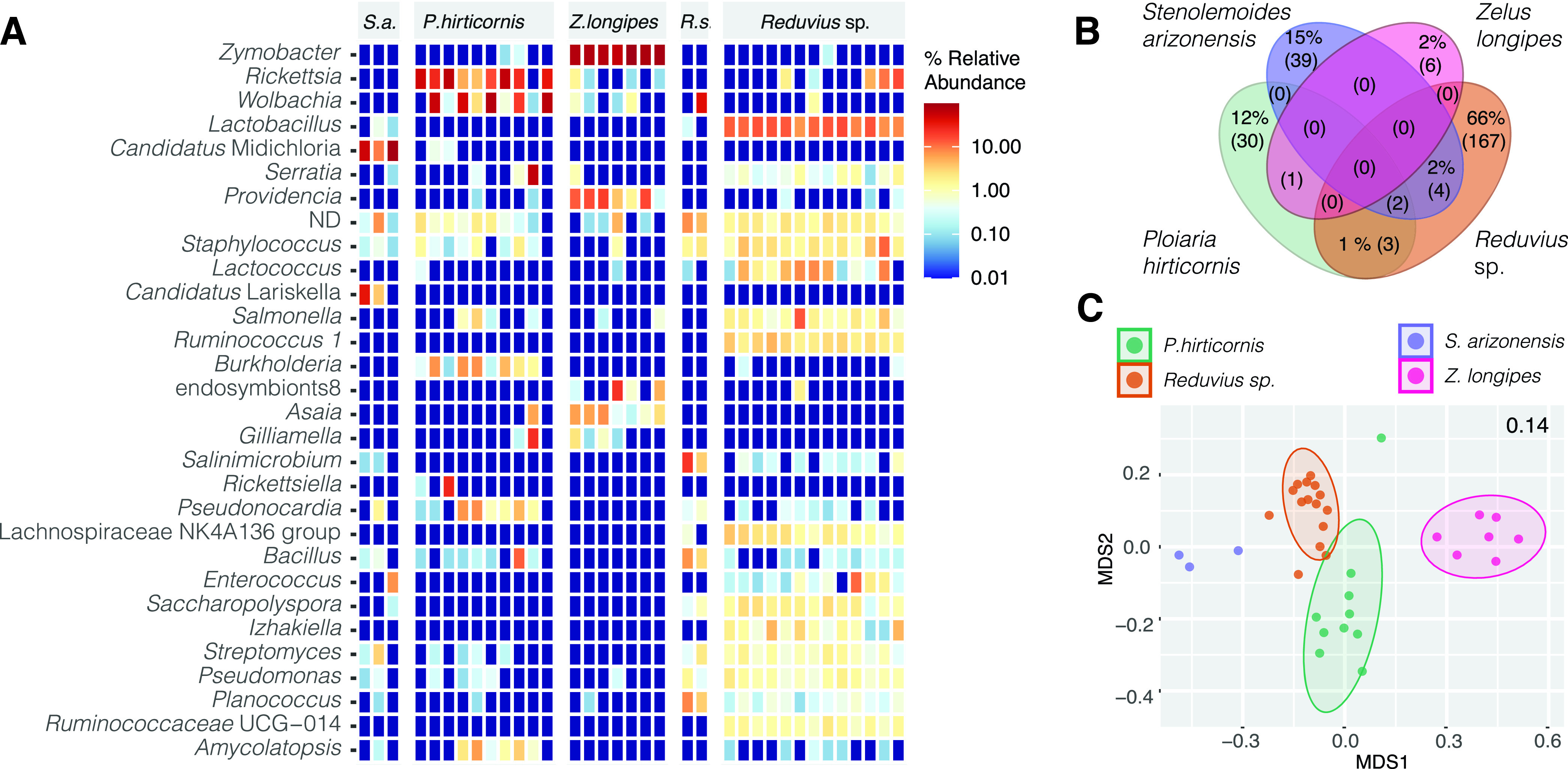

Microbiomes of related predatory assassin bugs.

Similar to Triatoma, host species was a significant predictor of assassin bug microbiome alpha (Table S1, data sheet S12) and beta (Fig. 2 and Table S1, data sheets S13 and S14) diversity, explaining over 60% of variation. Clear dissimilarities correlate with dominance of a single bacterial taxon in each assassin bug species, i.e., Rickettsia in Ploiaria hirticornis, Lactobacillus in Reduvius sp., “Candidatus Midichloria” in Stenolemoides arizonensis, and Zymobacter in Zelus longipes (Fig. 2A). Species specificity and dominance by a single taxon resemble the microbiome characteristics of related hematophagous kissing bugs (11) but pose a sharp contrast to the recently published microbiome patterns in Old World assassins (27). Based on the data from six Harpactorini species, Li and colleagues suggested Enterococcus bacteria to be a conserved microbiome component in most assassin bugs (27). In our data, Enterococcus is, however, found only in some individuals of Reduvius sp. and Stenolemoides arizonensis, both distantly related to the Harpactorini group of reduviids. For the only Harpactorini species in our data set, Zelus longipes, Enterococcus is absent across all individuals. The same applies for analyzed Ploiaria hirticornis individuals from the Emesinae group. A surprisingly high number of assassin bug-associated bacteria may be of further interest as they belong to known insect symbionts. These are unevenly distributed and include Rickettsia, “Candidatus Midichloria,” Wolbachia, “Candidatus Lariskella,” Asaia, Gilliamella, Burkholderia, and the bacteria from the Morganellaceae family (designated “endosymbiont8” [Fig. 2A]) with the closest BLASTn hit being to Arsenophonus symbionts known for a broad range of associations with invertebrates (28).

FIG 2.

Microbiome profiles of hemolymphophagous assassin bugs. (A) Heatmap showing the distribution of the 30 most abundant bacterial taxa identified across the assassin species. (B) Shared proportion of the microbiome components among the analyzed assassins. The numbers in the parentheses stand for the absolute number of OTUs. The shared proportion of the microbiome that accounts for less than 1% is depicted only as the absolute count (C). NMDS clustering based on Bray-Curtis distances. The number in the right upper corner indicates the stress value. Two Reduvius species were merged under a single group, Reduvius sp.

However, the primary goal of this study was not a thorough analysis of microbiome components in predatory Reduviidae. We only provide a habitat-specific frame for investigation of microbiome signatures underlain by the evolutionarily significant dietary switch of Triatominae predecessors. While our data do not suggest the existence of an assassin core microbiome (Venn for 0.5 fraction; Fig. 2B and Table S1, data sheet S15), under less stringent conditions they suggest a possible compositional convergence among Triatoma and Reduvius species (Table S1, data sheet S16) sharing Salmonella and Serratia.

Microbiome of the soft tick Ornithodoros turicata.

The microbiome profiles retrieved in this study resemble those described for O. turicata from Bolson tortoises in northern Mexico (29). However, Midichloria-related symbionts were not the most abundant taxa in our data set. Instead, several individuals harbored two Candidatus taxa from the Midichloriaceae family, “Candidatus Jidaibacter” and “Candidatus Lariskella” (Fig. 3A), and microbiomes were dominated by known symbiotic genera of ticks, i.e., Coxiella and Rickettsia (Fig. 3). While Coxiella symbionts have been previously described from O. turicata and other Ornithodoros species (29, 30), bacteria of the genus Rickettsia were identified only as potential symbionts of another soft tick species, Carios vespertilionis (30). The distributions of these two genera across our data set differed substantially. The genus Coxiella was omnipresent across nests and localities, detected in 96% of analyzed individuals. The genus Rickettsia was associated only with 26 individuals sampled in Desert Station, AZ (32% of all the samples). Rickettsia presence/absence further reflects the origin of the analyzed ticks from individual Neotoma nests and suggests the bacteria may rather represent vertebrate pathogens acquired through feeding. A similar pattern was observed for Borrelia pathogens vectored by ticks. Borrelia nest-specific distribution was further corroborated by the presence of the pathogen (detectable at a median relative abundance of 0.27%) in Triatoma individuals coinhabiting the same nests as the infected ticks. Compared among the three sampled localities, microbiomes of Lackland Air Force Base (AFB)-collected ticks displayed significantly higher measures for alpha diversity (Fig. 3C and Table S1, data sheet S17). In the ordination-based analysis, the microbiomes clustered according to their geographic origin (principal-coordinate analysis [PCoA] capturing 16% of the variation) (Fig. 3B and Table S1, data sheet S18, provide statistical support).

FIG 3.

Ornithodoros turicata microbiome profile. (A) Heatmap for the 30 most abundant genera. ND stands for the sum of the unclassified taxa at the genus level. (B) Principal-coordinate analysis based on Bray-Curtis distances. Colored shapes stand for different localities: DS, Desert Station, Tucson, AZ; Chaparral, Chaparral Wildlife Management Area, TX; LacklandAFB, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX. (C) Bray-Curtis microbiome dissimilarities calculated among the three localities. Asterisks indicate significant differences at 95%* and 99%** confidence interval found between the diversity measures (Dunn’s Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons, Table S1, data sheet S17).

Phylogenetic inference of possibly symbiotic taxa shared by different hosts.

We investigated the phylogenetic origin of possibly symbiotic OTUs from the families “Candidatus Midichloriaceae,” Morganellaceae, Rickettsiaceae, and Acetobacteraceae detected across different hosts. For the Rickettsiaceae OTUs, present in all P. hirticornis and Reduvius samples, five Zelus samples, and 37 O. turicata samples, our amplicon data could not provide sufficient phylogenetic resolution (Fig. S5). A similarly uncertain result was obtained for Acetobacteraceae OTUs taxonomically assigned to the genus Asaia. While OTU_39 falls among symbionts of mosquitos and Asaia species isolated from flowers (31, 32) the relationship of two other sequences to the genus remains highly questionable (Fig. S6).

Three Midichloriaceae OTUs, found in higher abundances in 14.2% (n = 5/35) of the assassin bugs and 20.7% (n = 17/82) of ticks, correspond to three distinct lineages (Fig. 4), two of which encompass endosymbionts of arthropods. OTU_6, present in assassin bugs, falls within the Midichloria genus, a well-known group of tick endosymbionts (33). OTU_26, found in both assassin bugs and ticks, clusters with the Lariskella group, which includes symbionts of ticks and insects (34). Interestingly, OTU_16, present in ticks, clusters with two Fokinia species, which reside in aquatic environments as symbionts of Paramecium (35, 36). However, this node is not highly supported, including two highly diverging Midichloriaceae (35, 36), and might be a product of long branch attraction. For the Morganellaceae OTU, we prepared a data set of 154 16S rRNA gene sequences, as in reference 28, including a single outgroup. The inferred phylogeny (Fig. S7) is well supported and clearly shows OTU_67 clustering with Morganellaceae symbionts of aphids. Among Zelus longipes individuals, the OTU distribution does not, however, suggest that the bacteria play a stable symbiotic role (being detected in 50% of the samples) and may point out its origin in the prey that often includes aphids.

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic inference on 16S rRNA gene sequences of Midichloriaceae OTUs associated with assassin bugs and ticks. Numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values.

Blood meal signature among Triatoma and tick microbiomes.

Primary blood meal was identified in all five sampled Triatoma species (93 individuals, 84%) and five individuals (6%) of Ornithodoros turicata (Table S1, data sheet S7). The striking difference in the fractions with determined vertebrate hosts is undoubtedly related to the distinct physiology of triatomines and soft ticks. While the two vectors feed on similar hosts, including mammals, reptiles, and birds (10, 37), soft ticks are known to endure extremely long starvation periods (38) that may hamper the molecular detection of ingested blood meal (39). For T. protracta (38/39), T. rubida (34/46), and T. lecticularia (10/12), packrats (Neotoma sp.) were indeed the most common blood meal (82/93, 88%). For six triatomines in our data set (6%), i.e., T. gerstaeckeri (4/7) and T. sanguisuga (2/6), armadillos, Dasypus sp., served as a blood meal source. Five Triatoma individuals fed on species of brown-toothed shrews, Episoriculus sp. (3), deer mice (Peromyscus sp.), and ground squirrels (Callospermophilus sp.). For 35 Triatoma individuals and a single tick, we were able to determine secondary blood meal sources (see Materials and Methods). These included the genera Felis (n = 32) and Dasypus (n = 3) and individual records on Callospermophilus and Neotoma (Table S1, data sheet S7). Neotoma predominance, along with the absence of human and domestic animals, may well reflect the sampling strategy, i.e., an active search for triatomines in sylvatic packrat nests. The range of other, less frequent hosts listed above is in line with earlier studies on North American Triatoma species (40, 41).

The uneven distribution among identified blood sources did not allow us to further evaluate whether different vertebrate hosts may determine the vector microbiome profile, as previously discussed for triatomines (42, 43) and other vectors, e.g., yellow fever mosquitos (44), tsetse flies (44), and western black-legged ticks (45). We therefore searched for common microbiome signatures among those individuals that fed on Neotoma (Table S1, data sheet S19). At least 50% of Neotoma-fed Triatoma and tick individuals harbored Cutibacterium (OTU_41), Streptomyces (OTU_102 and OTU_295), Brachybacterium (OTU_650), Arthrobacter (OTU_214), Microbacterium (OTU_254), Pseudonocardia (OTU_513), Massilia (OTU_43), Pseudomonas (OTU_59), and Acinetobacter (OTU_17), pointing out their potential link to the vertebrate host. Three of the OTUs belong to antimicrobial-producing bacteria (i.e., Pseudonocardiaceae and Streptomycetaceae) previously identified within the Key Largo woodrat (Neotoma floridana smalli) body microbiome and the microbiome of their nests in Florida (46, 47). In addition, Cutibacterium, a common skin commensal from the Propionibacteriaceae family (48), has been repeatedly recorded in the body swabs from small rodents (unpublished laboratory data). Notably, all six Triatoma individuals that fed on Dasypus harbored Alteribacillus (OTU_118), Pseudonocardia (OTU_177), and Mycobacterium (OTU_2341). The Mycobacterium OTU identified here represents a good candidate for a blood meal-related microbiome signature since Mycobacterium leprae, the causative agent of leprosy in humans, is commonly found among nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) in Texas and Florida (49).

Environmental microbiome.

The evaluation of nest material revealed a significant amount of variation between microbiome diversities of nests sampled in Gainesville, FL, and Lackland Air Force Base (AFB), TX (Adonis2; R2 = 0.274, P = 0.008) (Fig. S4 and Table S1, data sheets S20 and S21). The location also determined significant differences found for all alpha diversity measures (Dunn’s Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons, Table S1, data sheet S22, and Fig. S4). While the nest microbiome from Florida tends to be dominated by a few taxa, especially Bacilli genera Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and Lysinibacillus, Texas locations display more diverse and equally structured environmental microbiomes (Fig. 5A) composed mainly of Acidobacteriia (Bryobacter and Edaphobacter), Chitinophaga (Ferruginibacter and Flavisolibacter), and Planctomycetia (Singulisphaera and Pirellula-related Pyr4 lineage). Few taxa are, in different relative abundances, universally present across the sampled nests, i.e., Paenibacillus, Bacillus, and Planococcus (Fig. 5A). As the universal components of nest microbiomes, Bacillus (OTU_20) and Planococcus (OTU_50) are, at different Venn fractions, also observed in samples of Triatoma, ticks, and assassin bugs (Fig. 5B and Table S1, data sheets S23 and S11), supporting a role of the environment in shaping the Triatoma microbiomes as suggested previously (11). For triatomines and ticks occupying the same nest, Massilia (OTU_43) and several Streptomyces OTUs (Fig. 5B) were found as shared microbiome components, corroborating the findings on Neotoma-fed vectors above. Two OTUs, Staphylococcus (OTU_3) and Cutibacterium (OTU_41), were common across different arthropods from different nests (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Nest microbiome characteristics. (A) Heatmap for the 30 most abundant genera across the sampled nests. ND stands for the sum of the unclassified taxa at the genus level. (B) Venn analysis at 0.5 fraction among all sample types, i.e., ticks, kissing and assassin bugs, and nest material. The numbers in the parentheses stand for the absolute number of OTUs. The taxa in boldface were repeatedly recognized as shared microbiome members under different fractions (Table S1, data sheets S22 and S10) and thus considered of nest environmental origin. CB stands for Camp Bullis sampling site (data sheet S1).

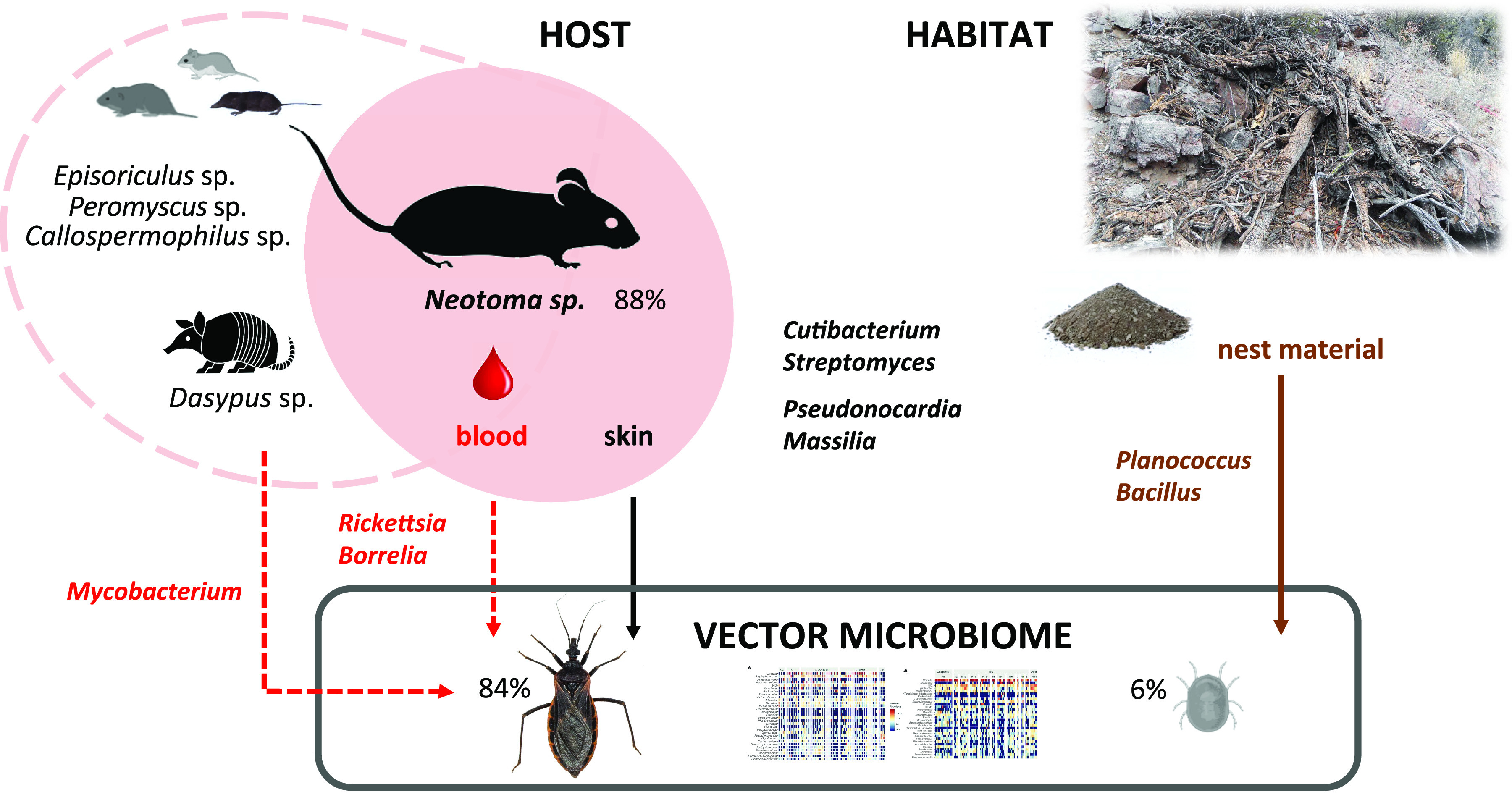

Since our nest material sampling does not fully mirror the arthropod sample set, especially with the lack of nest data from Arizona, we are limited in differentiating the environmental components within all analyzed arthropod microbiomes. In triatomines and ticks, the above-mentioned taxa, commonly found in skin or soil microbiomes (50–53), likely originate from the host-nest ecological interface. Based on the nest material and blood meal analyses, we thus suggest three mutually interrelated bacterial sources for vector microbiomes (Fig. 6): first, the environmental microbiome of their natural habitat, i.e., vertebrate nests and middens, as suggested previously for Triatoma (11) and other true bugs (27); second, vertebrate skin and skin-derivate microbiomes (54–56) that vectors encounter while feeding (Neotoma, Table S1, data sheet S19); and third, vertebrate pathogens circulating in blood as illustrated here for Triatoma on the Mycobacterium-Dasypus blood meal link and also supported by the distribution patterns for Rickettsia and Borrelia OTUs across the unfed ticks (see “Microbiome of the soft tick Ornithodoros turicata”). While in Triatoma and O. turicata microbiomes these bacteria likely represent transitional components, in other hematophagous vectors, like ticks and lice, vertebrate pathogens gave rise to evolutionarily stable symbiotic associations (57–59).

FIG 6.

Scheme for putative sources of vector microbiome based on blood meal analysis and nest microbiome profiling. Percentages next to each vector stand for successfully identified primary blood meal from which 88% matched Neotoma sp. The four taxa (Cutibacterium, Streptomyces, Pseudonocardia, and Massilia) might originate from both the host skin and the nest microhabitat.

Host phylogeny and diet as the microbiome determinants.

Clustering among analyzed arthropod microbiomes based on their similarities (calculated as weighted UniFrac distances, Fig. 7) shows triatomines in a monophyletic cluster and a close relationship between the microbiomes of two Emesinae species. These data suggest compositional convergence of microbiomes in regard to the host phylogenetic distance. The phylogenetic position of O. turicata soft ticks as a distant outgroup for the analyzed true bugs is not reflected in the microbiome dissimilarities. O. turicata clusters within the hemolymphophagous assassin bugs, resembling the Emesinae microbiomes dominated by common members of the Rickettsiales. While we have identified a shared microbiome component between the two hematophagous vectors (see “Blood meal signature among Triatoma and tick microbiomes”), it encompasses mostly less-abundant taxa of putatively environmental origin or blood-borne pathogens. These patterns are well reflected by clustering in the nonmetric dimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis and statistical tests supporting the host specificity of Triatoma microbiomes. The sample type acts as a significant predictor of microbiome profile, explaining close to 26% of found variation (Table S1, data sheet S24). Diet was identified as another significant predictor, though the effect is comparably lower, accounting for only 6% of found microbiome variation (Table S1, data sheet S24). Both diet and phylogenetic distance as factors underlying Triatominae microbiome structure indirectly support our hypothesis on microbiome change bound to the Triatominae evolutionary shift from hemolymphophagy of predatory Reduviidae to blood feeding.

FIG 7.

(A) Schematic host phylogenetic relationships compared to the microbiome dissimilarities based on weighted UniFrac distances. (B) The individual microbiome distances are visualized using NMDS.

In summary, comparisons between assassin bugs and triatomines show that the evolution of hematophagy was accompanied by microbiome compositional changes. These changes do not seem to have converged on a preferred taxon set similar to microbiomes in ticks, potentially due to physiological differences in the gut environment of these arthropods and their various feeding behaviors. The observed similarity of microbiomes within the sampled triatomines suggests that though the populations sampled are geographically separated, there is similarity between their communities, indicating convergence of microbial community compositions of this group. Future studies examining the functional diversity of these arthropod microbiomes through metagenomic sequencing and deeper taxon sampling will help further clarify how evolution has shaped host-microbiome associations in repeated transitions to hematophagy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample set and study sites.

The study was designed to encompass arthropods collected in the same microhabitat, i.e., white-throated wood rat (Neotoma albigula) nests, that share a common phylogenetic (Reduviidae, assassin and kissing bugs) or dietary (blood-feeding vectors, soft ticks and kissing bugs) background. In addition, environmental samples (n = 24) of the nest material were collected (Table 1). Two nests (N2 and N41) housed a complete subset of the analyzed arthropod groups (see Table S1, data sheet S1, in the supplemental material). Two hundred thirty-one samples representing different developmental stages of kissing bugs (Triatoma sp., n = 110), different assassin bug species (n = 37), and Ornithodoros turicata soft ticks (n = 84) were collected through four consecutive years (2017 to 2021) in the states of Arizona (n = 164), Florida (n = 12), Georgia (n = 10), and Texas (n = 45) (Table 1). Ten assassin bug individuals were not associated with the nests but collected at the same localities. The localities included Las Cienegas National Conservation Area (LCNCA) and the University of Arizona Desert Station (DS) in Tucson, AZ; Gainesville, FL; Oconee National Forest (GANF) and Sapelo Island, GA; and Chaparral Wildlife Management Area (Chaparral) and Lackland Air Force Base (LacklandAFB), San Antonio, TX. The sites were accessed with permission from the relevant governing bodies (see Acknowledgments). The nest coordinates, sample type, developmental stage, and sex (in adults) were recorded for acquired samples (Table S1, data sheet S1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of analyzed sample types from different states

| Sample type | No. of samples by state: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Florida | Georgia | Texas | Sum | |

| Triatoma | 85 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 110 |

| Tick | 59 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 84 |

| Assassin bug | 20 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 37 |

| Nest material | 0 | 9 | 0 | 15 | 24 |

| Sum | 164 | 21 | 10 | 60 | 255 |

DNA extraction and arthropod species determination.

DNA extraction of samples preserved in absolute ethanol was performed using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) on whole abdominal tissues according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and DNA was stored at −75°C for the downstream molecular analysis. DNA from environmental samples was extracted with the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Taxonomic determination of sampled ticks was based on their indicative morphological attributes (60). Triatoma species were determined based on their morphological and molecular characteristics. In detail, we amplified and Sanger sequenced a 682-bp segment of the cytB gene with the previously published (61) primers CYTB7432F and CYTB7433R, which allowed the identification of T. rubida, T. lecticularia, T. sanguisuga, and T. gerstaeckeri. Prospective T. protracta samples were amplified with primers TprF and TprR (11). Similarly, using previously published primers 18SF and 18SR (62), we obtained partial 18S rRNA gene sequences for assassin bugs. Details on all primers and PCR conditions used are provided in Table S1, data sheet S2. To determine assassin bug taxonomy, 18S rRNA data were aligned with MUSCLE (63) with 14 additional sequences retrieved from NCBI (see Table S1, data sheet S3, for the accession numbers). ModelTest-NG (64) was used to choose the evolutionary model for the phylogenetic inference according to Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) (65). The phylogenetic inference was calculated with RAxML (model GTR+I+G4; bootstrap random number seed, 1,234; number of bootstraps, 100; random number seed for the parsimony inferences, 123) (66). For the samples that were morphologically identified as the genus Reduvius, we employed an alternative mitochondrial marker (16S rRNA gene amplified with 16sa and 16sb primers [62]) and followed the same approach as described above.

Amplicon library preparation.

Amplification of the 16S rRNA V4-V5 region was carried out according to Earth Microbiome Project (EMP) standards (http://earthmicrobiome.org/protocols-and-standards/16s/). Multiplexing of 255 samples and 15 controls utilized a double barcoding strategy including 12-bp Golay barcodes in the forward primer and 5-bp barcodes in the reverse primer. The blocking primer for the 18S rRNA gene was employed as described previously (11). Seven negative controls were amplified along with the samples including two controls for the DNA extraction procedure (Blank2 and Blank21) and five controls from the PCR amplification step (NK, NK1, NK2, NK3, and NK11). Eight positive controls were used to confirm the barcoding output and to assess the detection limit and amplification bias. Positive controls included commercially purchased genomic DNA templates of four mock microbial communities with variable GC content and distribution. ATCC MSA-1000 (samples MCE and MCE1) and ATCC MSA-1001 (samples MCS and MCS1) are composed of 10 bacterial taxa with equal and staggered distributions, respectively. ZymoBIOMICS microbial community DNA standard (samples PC1 and PC3) and ZymoBIOMICS microbial community DNA standard II (samples PC2 and PC31) share eight bacterial and two yeast taxa with even and log distributions, respectively. The amplicons were purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter) magnetic beads and pooled equimolarly. An additional purification step using Pippin Prep (Sage Science) was employed to remove high concentrations of the 18S rRNA gene blocking primer and all unspecific amplification products. The nest material library containing 24 environmental templates was processed according to the same workflow with a single PCR negative control and two positive controls. The libraries were sequenced in two runs of MiSeq (Illumina) using v2 and Nano v2 chemistry with 2- by 250-bp output.

Analysis of the amplicon data.

Downstream processing, i.e., demultiplexing, merging, trimming, quality filtering, and OTU picking of reads, was performed by implementing corresponding scripts from USEARCH v9.2.64 as previously described (11). Briefly, merged demultiplexed reads from both sequencing runs were joined in a single data set that was subjected to quality and primer trimming resulting in a final amplicon length of 373 bp. The OTU table was created by generating a representative set of sequences based on 100% identity clustering and performing de novo OTU picking using USEARCH global alignment at 97% identity match, including chimera removal (67). Taxonomic assignment of representative sequences was executed using the BLASTn algorithm (68) against the sequences of single-subunit (SSU) rRNA genes from the SILVA_138.1_SSUREF_tax database (https://www.arb-silva.de/no_cache/download/archive/release_138.1/Exports/) (69). Filtering of potential contaminants from the OTU table was performed using decontam package v1.18.0 (70) in the R environment (71) based on frequency and prevalence methods of selection (https://rdrr.io/bioc/decontam/man/isContaminant.html), removing 48 out of 4,777 OTUs (Table S1, data sheets S4 and S5). In addition, bacterial taxa of the genus Sphingomonas were filtered out as it was a known contaminant in our laboratory (11). A single Wolbachia OTU (OTU_95) determined as a contaminant by the decontam package was used for further analysis. The choice to retain Wolbachia OTUs in the data set was based on their prevalence among the samples (70/232 samples), including assassin bugs (18/50) and ticks (20/50), for which associations with Wolbachia were previously reported (72–74).

Taking advantage of 12S rRNA data present in our data set as a result of nonspecific amplification (75), we identified blood meals from triatomines and ticks. An OTU table was generated from joined and clustered reads by utilizing USEARCH v9.2.64 (67) commands (fastq_join, fastx_uniques, and cluster_otus). Taxonomic assignment of identified OTUs was performed by BLASTn search against the NCBI nucleotide database (76) and restricted to the first hit only. The results were first filtered to include mammals and exclude samples with fewer than 20 reads. In addition, since the hits for the genera Neotoma and Homo were also observed in some negative controls, blood meal analysis was performed only with the samples where the two taxa reached higher read numbers than those in the negative controls (197 and 45 reads, respectively). The primary blood meal source was determined by the dominant 12S rRNA OTU, while the secondary sources were represented by other highly abundant OTUs found within a particular sample.

Microbiome analyses.

The profiles of the positive controls were compared and plotted using the ggplot2 v3.4.0 (77) and svglite v2.1.0 (78) packages. Additional cleanup, microbiome analyses, data visualization, and statistical tests were performed in the R environment (71) using phyloseq v1.42.0 (79), vegan v2.6-4 (80), and MicEco v0.9.19 (https://github.com/Russel88/MicEco) and MicroEco v0.13.0 (81) packages. Graphical outputs were generated utilizing ggplot2 v3.4.0 (77) and further processed in Adobe Illustrator v25.4.1. A “clean” data set was prepared by filtering out any archaeal, eukaryotic, mitochondrial, and chloroplast OTUs. Since the environmental samples produced considerably smaller amounts of data, we have analyzed the “clean” data set at two rarefaction levels (800 and 1,000 reads per sample, seed = 5) to retain enough of the nest material samples. We focused on effects of several microbiome determinants including environmental microbiome background of sampled habitats, host phylogenetic origin, and the dietary niche (blood versus hemolymph and different blood meal sources).

The overall consistency of Triatominae microbiome profiles sequenced here with previously published data (11) was confirmed based on their taxonomic composition and dissimilarities found among Triatoma species. In the MicroEco v0.13.0 (81) package, we used the trans_abundance class to determine highly abundant bacteria. Alpha diversity was calculated by utilizing the trans_alpha class, and differences found among species were statistically evaluated based on Dunn’s Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparison method. Using the trans_beta class, beta diversity analysis was performed based on Bray-Curtis distances among individual microbiomes and visualized through nonmetric dimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination. Adonis2 implemented under the cal_manova method of the trans_beta class was employed to confirm Triatoma species as a statistically significant factor driving the microbiome profile. Similarly, using trans_abundance, trans_alpha, and trans_beta classes, we have calculated alpha and beta diversity for tick, assassin bug, and nest material microbiomes, including statistical evaluations for selected factors potentially underlying found variation, and we produced heatmaps to visualize their taxonomic composition.

The ps_venn function in the MicEco package was utilized first to identify the potentially environmentally acquired fraction of analyzed invertebrate microbiomes (defined as OTUs present in at least 30% of all nest material samples [Table S1, data sheet S6]). Second, unique and shared taxa within and among different sample groups were identified under a more stringent fraction range (0.5, 0.8, 0.9, and 1 for all samples within the group). For the Triatoma shared microbiome, the ps_venn results were visualized using the UpSet plot (https://github.com/visdesignlab/upset2) (82). The ps_venn function was further employed for identifying possible taxonomic convergence among microbiomes of blood-feeding vectors (O. turicata and Triatoma spp.), related Reduviidae (kissing and assassin bugs), and within the two Reduviidae groups, i.e., among different Triatoma species, among different assassin species (Reduvius sonoraensis [“Reduvinae”], Zelus longipes [Harpactorinae], Ploiaria hirticornis [Emesinae: Leistarchini], and Stenolemoides arizonensis [Emesinae: Emesini]).

Phylogenetic inference of putative symbiotic taxa shared by different hosts.

The analysis comprised OTUs shared between at least two different sample types (triatomines, ticks, and assassins) that belong to the bacterial genera previously reported as arthropod symbionts. The data sets were generated for the families Midichloriaceae, Morganellaceae, and Rickettsiaceae and for the genus Asaia from the OTU representative sequences and partial 16S rRNA gene sequences downloaded from NCBI. The data sets were aligned with MUSCLE software (63). For each alignment, an evolutionary model was selected, and phylogenetic analysis was performed as described above for the arthropod species determination.

Data availability.

Raw sequence reads generated from this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under BioProject accession no. PRJNA898622. The complete R code employed in this study with its associated data sets is available at https://github.com/hassantarabai/Convergency-MS-2022.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the University of Arizona Department of Entomology’s Desert Station for graciously supporting our field activities. We thank Samantha M. Wisely and Chanakya R. Bhosale for logistical and technical assistance with sampling in Gainesville, FL. We further acknowledge the contributions of the Texas Park and Wildlife Management Department and the Bureau of Land Management (Gila District Office, Tucson, AZ).

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (grant number 21-10185M to E.N.).

E.N. conceived the study. E.N., A.M.F., J.J.B., N.F., R.L.S., N.L.B., K.J.V., and W.R. participated in planning and executing field collections. J.Z. and N.F. performed the DNA isolation, library preparation, and sequencing. H.T., A.M.F., and E.N. analyzed the data and interpreted results. H.T., A.M.F., and E.N. wrote the draft, and all the authors contributed to its improvement. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We declare that we have no competing interests. Robert L. Smith has not sought nor has he received any remuneration for providing access to Desert Station and adjacent private land and residence, nor has he received payments from any researchers or scholarly visitors on Desert Station.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Eva Nováková, Email: novake01@prf.jcu.cz.

Denis Sereno, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sudakaran S, Kost C, Kaltenpoth M. 2017. Symbiont acquisition and replacement as a source of ecological innovation. Trends Microbiol 25:375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brucker RM, Bordenstein SR. 2012. Speciation by symbiosis. Trends Ecol Evol 27:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koga R, Bennett GM, Cryan JR, Moran NA. 2013. Evolutionary replacement of obligate symbionts in an ancient and diverse insect lineage. Environ Microbiol 15:2073–2081. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hypsa V, Krizek J. 2007. Molecular evidence for polyphyletic origin of the primary symbionts of sucking lice (phthiraptera, anoplura). Microb Ecol 54:242–251. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perotti MA, Kirkness EF, Reed DL, Braig HR. 2008. Endosymbionts of lice, p 205–220. In Bourtzis K, Miller TA (ed), Insect symbiosis, 1st ed, vol 3. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd BM, Allen JM, Koga R, Fukatsu T, Sweet AD, Johnson KP, Reed DL. 2016. Two bacterial genera, Sodalis and Rickettsia, associated with the seal louse Proechinophthirus fluctus (Phthiraptera: Anoplura). Appl Environ Microbiol 82:3185–3197. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00282-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manzano-Marin A, Oceguera-Figueroa A, Latorre A, Jimenez-Garcia LF, Moya A. 2015. Solving a bloody mess: B-vitamin independent metabolic convergence among gammaproteobacterial obligate endosymbionts from blood-feeding arthropods and the leech Haementeria officinalis. Genome Biol Evol 7:2871–2884. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song SJ, Sanders JG, Baldassarre DT, Chaves JA, Johnson NS, Piaggio AJ, Stuckey MJ, Novakova E, Metcalf JL, Chomel BB, Aguilar-Setien A, Knight R, McKenzie VJ. 2019. Is there convergence of gut microbes in blood-feeding vertebrates? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 374:20180249. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang WS, Weirauch C. 2012. Evolutionary history of assassin bugs (insecta: hemiptera: Reduviidae): insights from divergence dating and ancestral state reconstruction. PLoS One 7:e45523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilheiro AB, Costa GDS, Araujo MDS, Ribeiro WAR, Medeiros JF, Camargo LMA. 2022. Identification of blood meal sources in species of genus Rhodnius in four different environments in the Brazilian amazon. Acta Trop 232:106486. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JJ, Rodriguez-Ruano SM, Poosakkannu A, Batani G, Schmidt JO, Roachell W, Zima J, Jr, Hypsa V, Novakova E. 2020. Ontogeny, species identity, and environment dominate microbiome dynamics in wild populations of kissing bugs (Triatominae). Microbiome 8:146. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00921-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filée J, Agésilas-Lequeux K, Lacquehay L, Bérenger JM, Dupont L, Mendonça V, da Rosa JA, Harry M. 2023. Wolbachia genomics reveals a potential for a nutrition-based symbiosis in blood-sucking Triatomine bugs. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2022.09.06.506778. [DOI]

- 13.Wigglesworth VB. 1936. Symbiotic bacteria in a blood-sucking insect, Rhodnius Prolixus Stål. (Hemiptera, Triatomidae). Parasitology 28:284–289. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000022459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilliland CA, Patel V, McCormick AC, Mackett BM, Vogel KJ. 2023. Using axenic and gnotobiotic insects to examine the role of different microbes on the development and reproduction of the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Mol Ecol 32:920–935. doi: 10.1111/mec.16800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt GR. 1961. The biochemistry of insect hemolymph. Annu Rev Entomol 6:75–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.06.010161.000451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graca-Souza AV, Maya-Monteiro C, Paiva-Silva GO, Braz GR, Paes MC, Sorgine MH, Oliveira MF, Oliveira PL. 2006. Adaptations against heme toxicity in blood-feeding arthropods. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 36:322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry LM, Maiden MC, Ferrari J, Godfray HC. 2015. Insect life history and the evolution of bacterial mutualism. Ecol Lett 18:516–525. doi: 10.1111/ele.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vivero RJ, Jaramillo NG, Cadavid-Restrepo G, Soto SI, Herrera CX. 2016. Structural differences in gut bacteria communities in developmental stages of natural populations of Lutzomyia evansi from Colombia’s Caribbean coast. Parasit Vectors 9:496. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1766-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malhotra J, Dua A, Saxena A, Sangwan N, Mukherjee U, Pandey N, Rajagopal R, Khurana P, Khurana JP, Lal R. 2012. Genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. strain HA, isolated from the gut of the polyphagous insect pest Helicoverpa armigera. J Bacteriol 194:5156. doi: 10.1128/JB.01194-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalfant RB, N’Guessan KF. 1990. Dose response of the cowpea curculio (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) from different regions of Georgia to some currently used pyrethroid insecticides. J Entomol Sci 25:219–222. doi: 10.18474/0749-8004-25.2.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietrantonio PV, Junek TA, Parker R, Mott D, Siders K, Troxclair N, Vargas-Camplis J, Westbrook JK, Vassiliou VA. 2007. Detection and evolution of resistance to the pyrethroid cypermethrin in Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) populations in Texas. Environ Entomol 36:1174–1188.2.0.CO;2]. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X(2007)36[1174:DAEORT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennehy TJ, DeGain BA, Harpold VS, Brink SA. 2004. Vegetable report 2004. College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- 23.da Mota FF, Castro DP, Vieira CS, Gumiel M, de Albuquerque JP, Carels N, Azambuja P. 2018. In vitro trypanocidal activity, genomic analysis of isolates, and in vivo transcription of type VI secretion system of Serratia marcescens belonging to the microbiota of Rhodnius prolixus digestive tract. Front Microbiol 9:3205. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azambuja P, Feder D, Garcia ES. 2004. Isolation of Serratia marcescens in the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus: impact on the establishment of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in the vector. Exp Parasitol 107:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waltmann A, Willcox AC, Balasubramanian S, Borrini Mayori K, Mendoza Guerrero S, Salazar Sanchez RS, Roach J, Condori Pino C, Gilman RH, Bern C, Juliano JJ, Levy MZ, Meshnick SR, Bowman NM. 2019. Hindgut microbiota in laboratory-reared and wild Triatoma infestans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orantes LC, Monroy C, Dorn PL, Stevens L, Rizzo DM, Morrissey L, Hanley JP, Rodas AG, Richards B, Wallin KF, Helms Cahan S. 2018. Uncovering vector, parasite, blood meal and microbiome patterns from mixed-DNA specimens of the Chagas disease vector Triatoma dimidiata. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Sun J, Meng Y, Yang C, Chen Z, Wu Y, Tian L, Song F, Cai W, Zhang X, Li H. 2022. The impact of environmental habitats and diets on the gut microbiota diversity of true bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). Biology (Basel) 11:1039. doi: 10.3390/biology11071039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novakova E, Hypsa V, Moran NA. 2009. Arsenophonus, an emerging clade of intracellular symbionts with a broad host distribution. BMC Microbiol 9:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barraza-Guerrero SI, Meza-Herrera CA, Garcia-De la Pena C, Gonzalez-Alvarez VH, Vaca-Paniagua F, Diaz-Velasquez CE, Sanchez-Tortosa F, Avila-Rodriguez V, Valenzuela-Nunez LM, Herrera-Salazar JC. 2020. General microbiota of the soft tick Ornithodoros turicata parasitizing the Bolson tortoise (Gopherus flavomarginatus) in the Mapimi Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Biology (Basel) 9:275. doi: 10.3390/biology9090275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moustafa MAM, Mohamed WMA, Lau ACC, Chatanga E, Qiu Y, Hayashi N, Naguib D, Sato K, Takano A, Matsuno K, Nonaka N, Taylor D, Kawabata H, Nakao R. 2022. Novel symbionts and potential human pathogens excavated from argasid tick microbiomes that are shaped by dual or single symbiosis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 20:1979–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damiani C, Ricci I, Crotti E, Rossi P, Rizzi A, Scuppa P, Capone A, Ulissi U, Epis S, Genchi M, Sagnon N, Faye I, Kang A, Chouaia B, Whitehorn C, Moussa GW, Mandrioli M, Esposito F, Sacchi L, Bandi C, Daffonchio D, Favia G. 2010. Mosquito-bacteria symbiosis: the case of Anopheles gambiae and Asaia. Microb Ecol 60:644–654. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favia G, Ricci I, Damiani C, Raddadi N, Crotti E, Marzorati M, Rizzi A, Urso R, Brusetti L, Borin S, Mora D, Scuppa P, Pasqualini L, Clementi E, Genchi M, Corona S, Negri I, Grandi G, Alma A, Kramer L, Esposito F, Bandi C, Sacchi L, Daffonchio D. 2007. Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associate with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:9047–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cafiso A, Bazzocchi C, De Marco L, Opara MN, Sassera D, Plantard O. 2016. Molecular screening for Midichloria in hard and soft ticks reveals variable prevalence levels and bacterial loads in different tick species. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 7:1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnet SI, Binetruy F, Hernandez-Jarguin AM, Duron O. 2017. The tick microbiome: why non-pathogenic microorganisms matter in tick biology and pathogen transmission. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:236. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szokoli F, Sabaneyeva E, Castelli M, Krenek S, Schrallhammer M, Soares CA, da Silva-Neto ID, Berendonk TU, Petroni G. 2016. “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria,” a novel “stand-alone” symbiotic lineage of Midichloriaceae (Rickettsiales). PLoS One 11:e0145743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Floriano AM, Castelli M, Krenek S, Berendonk TU, Bazzocchi C, Petroni G, Sassera D. 2018. The genome sequence of “Candidatus Fokinia solitaria”: insights on reductive evolution in Rickettsiales. Genome Biol Evol 10:1120–1126. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HJ, Hamer GL, Hamer SA, Lopez JE, Teel PD. 2021. Identification of host bloodmeal source in Ornithodoros turicata Duges (Ixodida: Argasidae) using DNA-based and stable isotope-based techniques. Front Vet Sci 8:620441. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.620441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francıs E. 1938. Longevity of the tick Ornithodoros turicata and of Spirochaeta recurrentis within this tick. Public Health Rep 53:2220. doi: 10.2307/4582740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leger E, Liu X, Masseglia S, Noel V, Vourc’h G, Bonnet S, McCoy KD. 2015. Reliability of molecular host-identification methods for ticks: an experimental in vitro study with Ixodes ricinus. Parasit Vectors 8:433. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balasubramanian S, Curtis-Robles R, Chirra B, Auckland LD, Mai A, Bocanegra-Garcia V, Clark P, Clark W, Cottingham M, Fleurie G, Johnson CD, Metz RP, Wang S, Hathaway NJ, Bailey JA, Hamer GL, Hamer SA. 2022. Characterization of triatomine bloodmeal sources using direct Sanger sequencing and amplicon deep sequencing methods. Sci Rep 12:10234. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14208-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kjos SA, Marcet PL, Yabsley MJ, Kitron U, Snowden KF, Logan KS, Barnes JC, Dotson EM. 2013. Identification of bloodmeal sources and Trypanosoma cruzi infection in triatomine bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) from residential settings in Texas, the United States. J Med Entomol 50:1126–1139. doi: 10.1603/me12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dumonteil E, Pronovost H, Bierman EF, Sanford A, Majeau A, Moore R, Herrera C. 2020. Interactions among Triatoma sanguisuga blood feeding sources, gut microbiota and Trypanosoma cruzi diversity in southern Louisiana. Mol Ecol 29:3747–3761. doi: 10.1111/mec.15582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dumonteil E, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Perez-Carrillo S, Teh-Poot C, Herrera C, Gourbiere S, Waleckx E. 2018. Detailed ecological associations of triatomines revealed by metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing: implications for triatomine behavior and Trypanosoma cruzi transmission cycles. Sci Rep 8:4140. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22455-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaithuma A, Yamagishi J, Hayashida K, Kawai N, Namangala B, Sugimoto C. 2020. Blood meal sources and bacterial microbiome diversity in wild-caught tsetse flies. Sci Rep 10:5005. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swei A, Kwan JY. 2017. Tick microbiome and pathogen acquisition altered by host blood meal. ISME J 11:813–816. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Platas G, Morón R, González I, Collado J, Genilloud O, Peláez F, Diez MT. 1998. Production of antibacterial activities by members of the family Pseudonocardiaceae: influence of nutrients. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 14:521–527. doi: 10.1023/A:1008874203344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thoemmes MS, Cove MV. 2020. Bacterial communities in the natural and supplemental nests of an endangered ecosystem engineer. Ecosphere 11:e03239. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scholz CFP, Kilian M. 2016. The natural history of cutaneous propionibacteria, and reclassification of selected species within the genus Propionibacterium to the proposed novel genera Acidipropionibacterium gen. nov., Cutibacterium gen. nov. and Pseudopropionibacterium gen. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:4422–4432. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perez-Heydrich C, Loughry WJ, Anderson CD, Oli MK. 2016. Patterns of Mycobacterium leprae infection in wild nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) in Mississippi, USA. J Wildl Dis 52:524–532. doi: 10.7589/2015-03-066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Madigan MT. 2012. Brock biology of microorganisms, 13th ed. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baek JH, Baek W, Ruan W, Jung HS, Lee SC, Jeon CO. 2022. Massilia soli sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 72(2). doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamid ME, Reitz T, Joseph MRP, Hommel K, Mahgoub A, Elhassan MM, Buscot F, Tarkka M. 2020. Diversity and geographic distribution of soil streptomycetes with antagonistic potential against actinomycetoma-causing Streptomyces sudanensis in Sudan and South Sudan. BMC Microbiol 20:33. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-1717-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oh J, Byrd AL, Deming C, Conlan S, Kong HH, Segre JA, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program . 2014. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature 514:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Avena CV, Parfrey LW, Leff JW, Archer HM, Frick WF, Langwig KE, Kilpatrick AM, Powers KE, Foster JT, McKenzie VJ. 2016. Deconstructing the bat skin microbiome: influences of the host and the environment. Front Microbiol 7:1753. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ross AA, Rodrigues Hoffmann A, Neufeld JD. 2019. The skin microbiome of vertebrates. Microbiome 7:79. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roggenbuck M, Bærholm Schnell I, Blom N, Bælum J, Bertelsen MF, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Sørensen SJ, Gilbert MTP, Graves GR, Hansen LH. 2014. The microbiome of New World vultures. Nat Commun 5:5498. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brenner AE, Munoz-Leal S, Sachan M, Labruna MB, Raghavan R. 2021. Coxiella burnetii and related tick endosymbionts evolved from pathogenic ancestors. Genome Biol Evol 13:evab108. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evab108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Říhová J, Nováková E, Husník F, Hypša V. 2017. Legionella becoming a mutualist: adaptive processes shaping the genome of symbiont in the louse Polyplax serrata. Genome Biol Evol 9:2946–2957. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Říhová J, Batani G, Rodríguez-Ruano SM, Martinů J, Vácha F, Nováková E, Hypša V. 2021. A new symbiotic lineage related to Neisseria and Snodgrassella arises from the dynamic and diverse microbiomes in sucking lice. Mol Ecol 30:2178–2196. doi: 10.1111/mec.15866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooley R. 1944. The argasidae of North America, Central America and Cuba. University Press, Notre Dame, IN. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monteiro FA, Barrett TV, Fitzpatrick S, Cordon-Rosales C, Feliciangeli D, Beard CB. 2003. Molecular phylogeography of the Amazonian Chagas disease vectors Rhodnius prolixus and R. robustus. Mol Ecol 12:997–1006. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weirauch C, Munro JB. 2009. Molecular phylogeny of the assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), based on mitochondrial and nuclear ribosomal genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 53:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, Flouri T. 2020. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol Biol Evol 37:291–294. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Posada D, Buckley TR. 2004. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst Biol 53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edgar RC. 2013. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glockner FO. 2013. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis NM, Proctor DM, Holmes SP, Relman DA, Callahan BJ. 2018. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome 6:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.R Core Team. 2000. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

- 72.Riano HC, Jaramillo N, Dujardin JP. 2009. Growth changes in Rhodnius pallescens under simulated domestic and sylvatic conditions. Infect Genet Evol 9:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Espino CI, Gomez T, Gonzalez G, do Santos MF, Solano J, Sousa O, Moreno N, Windsor D, Ying A, Vilchez S, Osuna A. 2009. Detection of Wolbachia bacteria in multiple organs and feces of the triatomine insect Rhodnius pallescens (Hemiptera, Reduviidae). Appl Environ Microbiol 75:547–550. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01665-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Duron O, Binetruy F, Noel V, Cremaschi J, McCoy KD, Arnathau C, Plantard O, Goolsby J, Perez de Leon AA, Heylen DJA, Van Oosten AR, Gottlieb Y, Baneth G, Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Pena A, Opara MN, Zenner L, Vavre F, Chevillon C. 2017. Evolutionary changes in symbiont community structure in ticks. Mol Ecol 26:2905–2921. doi: 10.1111/mec.14094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parada AE, Needham DM, Fuhrman JA. 2016. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ Microbiol 18:1403–1414. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sayers EW, Beck J, Bolton EE, Bourexis D, Brister JR, Canese K, Comeau DC, Funk K, Kim S, Klimke W, Marchler-Bauer A, Landrum M, Lathrop S, Lu Z, Madden TL, O’Leary N, Phan L, Rangwala SH, Schneider VA, Skripchenko Y, Wang J, Ye J, Trawick BW, Pruitt KD, Sherry ST. 2021. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 49:D10–D17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ito K, Murphy D. 2013. Application of ggplot2 to pharmacometric graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2:e79. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wickham H, Henry L, Pedersen T, Luciani T, Decorde M, Lise V. 2022. svglite: a lightweight svg graphics device for R. https://github.com/lamdalili/SVGLite.

- 79.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oksanen J, Simpson GL, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H, Barbour M, Bedward M, Bolker B, Borcard D, Carvalho G, Chirico M, De Caceres M, Durand S, Evangelista HBA, FitzJohn R, Friendly M, Furneaux B, Hannigan G, Hill MO, Lahti L, McGlinn D, Ouellette M-H, Cunha ER, Smith T, Stier A, Ter Braak CJF, Weedon J. 2019. vegan: community ecology package. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html.

- 81.Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, Yao M. 2021. microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 97:fiaa255. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lex A, Gehlenborg N, Strobelt H, Vuillemot R, Pfister H. 2014. UpSet: visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans Vis Comput Graph 20:1983–1992. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2014.2346248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S7. Download spectrum.01681-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.9 MB (1.9MB, pdf)

Table S1. Download spectrum.01681-23-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 4.3 MB (4.3MB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequence reads generated from this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under BioProject accession no. PRJNA898622. The complete R code employed in this study with its associated data sets is available at https://github.com/hassantarabai/Convergency-MS-2022.