ABSTRACT

Theileria, a tick-borne intracellular protozoan, can cause infections of various livestock and wildlife around the world, posing a threat to veterinary health. Although more and more Theileria species have been identified, genomes have been available only from four Theileria species to date. Here, we assembled a whole genome of Theileria luwenshuni, an emerging Theileria, through next-generation sequencing of purified erythrocytes from the blood of a naturally infected goat. We designated it T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo because its genome was assembled by the researchers at Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, China. The genome of T. lunwenshuni str. Cheeloo was the smallest in comparison with the other four Theileria species. T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo possessed the fewest gene gains and gene family expansion. The protein count of each category was always comparable between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and T. orientalis str. Shintoku in the Eukaryote Orthologs annotation, though there were remarkable differences in genome size. T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo had lower counts than the other four Theileria species in most categories at level 3 of Gene Ontology annotation. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes annotation revealed a loss of the c-Myb in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. The infection rate of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo was up to 81.5% in a total of 54 goats from three flocks. The phylogenetic analyses based on both 18S rRNA and cox1 genes indicated that T. luwenshuni had relatively low diversity. The first characterization of the T. luwenshuni genome will promote better understanding of the emerging Theileria.

IMPORTANCE Theileria has led to substantial economic losses in animal husbandry. Whole-genome sequencing data of the genus Theileria are currently limited, which has prohibited us from further understanding their molecular features. This work depicted whole-genome sequences of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo, an emerging Theileria species, and reported a high prevalence of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo infection in goats. The first assembly and characterization of T. luwenshuni genome will benefit exploring the infective and pathogenic mechanisms of the emerging Theileria to provide scientific basis for future control strategies of theileriosis.

KEYWORDS: Theileria luwenshuni strain Cheeloo, whole-genome sequence, FISH, genomic characteristics, phylogenetic analysis

INTRODUCTION

Theileria is an obligate intracellular protozoan distributed around the world, and often causes disease in a variety of livestock and wildlife (1, 2), posing a substantial threat to veterinary health. Six Theileria species are known to infect cattle (3), among which Theileria parva, Theileria orientalis, and Theileria annulata are the most pathogenic and economically important (4–6). Theileria equi that can infect horses is a significant concern. The Theileria species is also capable of infecting wild ruminants, such as zebu cattle (7), African buffaloes (8), wild red deer, and sika deer (9). Theileria lestoquardi and Theileria luwenshuni are highly pathogenic, especially to goats, leading to economic losses in animal husbandry (10–13). In addition, several Theileria species emerged recently and might cause infection and disease in various livestock and wildlife in different regions of the world (14, 15), Although some Theileria species tend to be carried asymptomatically by hosts, several can result in diseases, and even death (16–22).

The species identification within the genus Theileria is usually based on the phylogenetic analysis of 18S rRNA gene (2, 23, 24). So far, only 12 genome sequences belonging to four Theileria species have been published and deposited in GenBank, including T. orientalis, T. parva, T. annulata, and T. equi (5, 6, 25, 26). The whole genomes of other Theileria species have not been available, which has prohibited us from understanding their evolutionary, genetic, and pathogenic characteristics. In a survey on tick-borne infection of goats, T. luwenshuni was detected in a flock of goats from Shandong Province of eastern China. We selected a blood sample positive for T. luwenshuni to get the genome sequence of the endoparasite using metagenomic sequencing. Considering Theileria is abundant in erythrocytes, in this study, we separated erythrocytes from the blood of the infected goat to enrich the parasite, and then assembled the whole genome of T. luwenshuni to characterize its genomic composition in comparison with genomes of other Theileria species, and to further evaluate the prevalence of the emerging Theileria species in hosts.

RESULTS

Identification of T. luwenshuni in goat blood.

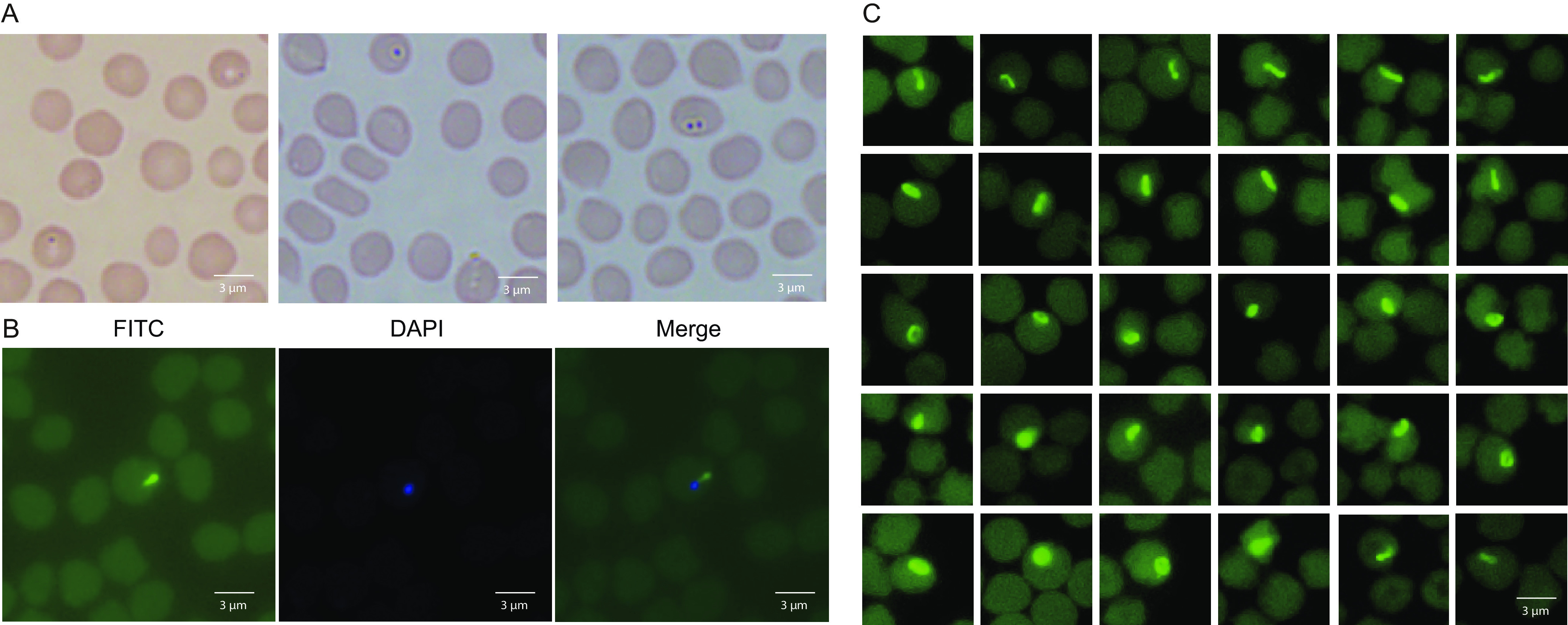

In a survey on tick-borne infections in goats, T. luwenshuni was detected in blood samples of goats from Shandong Province of eastern China (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) by PCR using universal primers targeting the partial 18S rRNA gene (424 bp) of Theileria and Babesia (Table S1). BLAST analysis of the amplified fragment sequences revealed a 99.06% identity with the corresponding part of the T. luwenshuni HNQZ strain from goats in Hainan Province, China (GenBank accession no. MK685118.1). One or two Theileria could be visualized in each infected erythrocyte on the blood smear prepared from infected goats by Wright-Giemsa staining (Fig. 1A). To further confirm the presence of T. luwenshuni, we conducted a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay using a specific probe designed according to 18S rRNA gene sequence and labeled with FAM, a green fluorescein. T. luwenshuni was observed with the nucleus stained by DAPI in the blood smears (Fig. 1B). They were polymorphic, including rod-shaped, pear-shaped, ovoid, or round. Their sizes were about 1.5 μm on average, ranging from 1 to 2 μm (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Morphology and size of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo inside erythrocytes. (A) Wright-Giemsa staining of goat blood smears (1,000×). (B) Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) results under fluorescence microscope of Theileria luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. From left to right represent the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) channel (fluorescence channel), the DAPI channel, and the merge channel. The blue fluorescence is the nucleus of the Theileria and the green strong fluorescence is the target T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. (C) FISH results showing different shapes and sizes of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo in erythrocytes.

Next-generation sequencing of blood from an infected goat.

A blood sample with high infection rate of erythrocytes from a naturally infected goat (No. 2) was chosen for next-generation sequencing. We first separated erythrocytes from 15 mL blood, and then lysed erythrocytes to enrich T. luwenshuni and primarily remove nucleic acid of the host goat. Total DNA was extracted from the supernatant of the lysed liquid, and DNA yields and purity were measured by automated electrophoresis. Then the sequencing library was prepared according to the whole-genome sequencing library preparation protocol (DNBSEQ). The metagenome sequencing resulted in over 39.3 million 150-bp Illumina reads from the sample. Despite primary removing of host DNA, 95.9% reads were mapped to the goat genome, and were discarded. The remaining reads were then de novo assembled into scaffolds using the SPAdes program (v3.15.3) with meta parameters. After assembly and binning, the T. luwenshuni genome with 7.61 Mb was discovered in assembly result, and named Theileria luwenshuni str. Cheeloo (GenBank accession no. GCA_029379255.1), because it was initially obtained by the researchers at Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, China.

Genomic composition and phylogenetic position of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo.

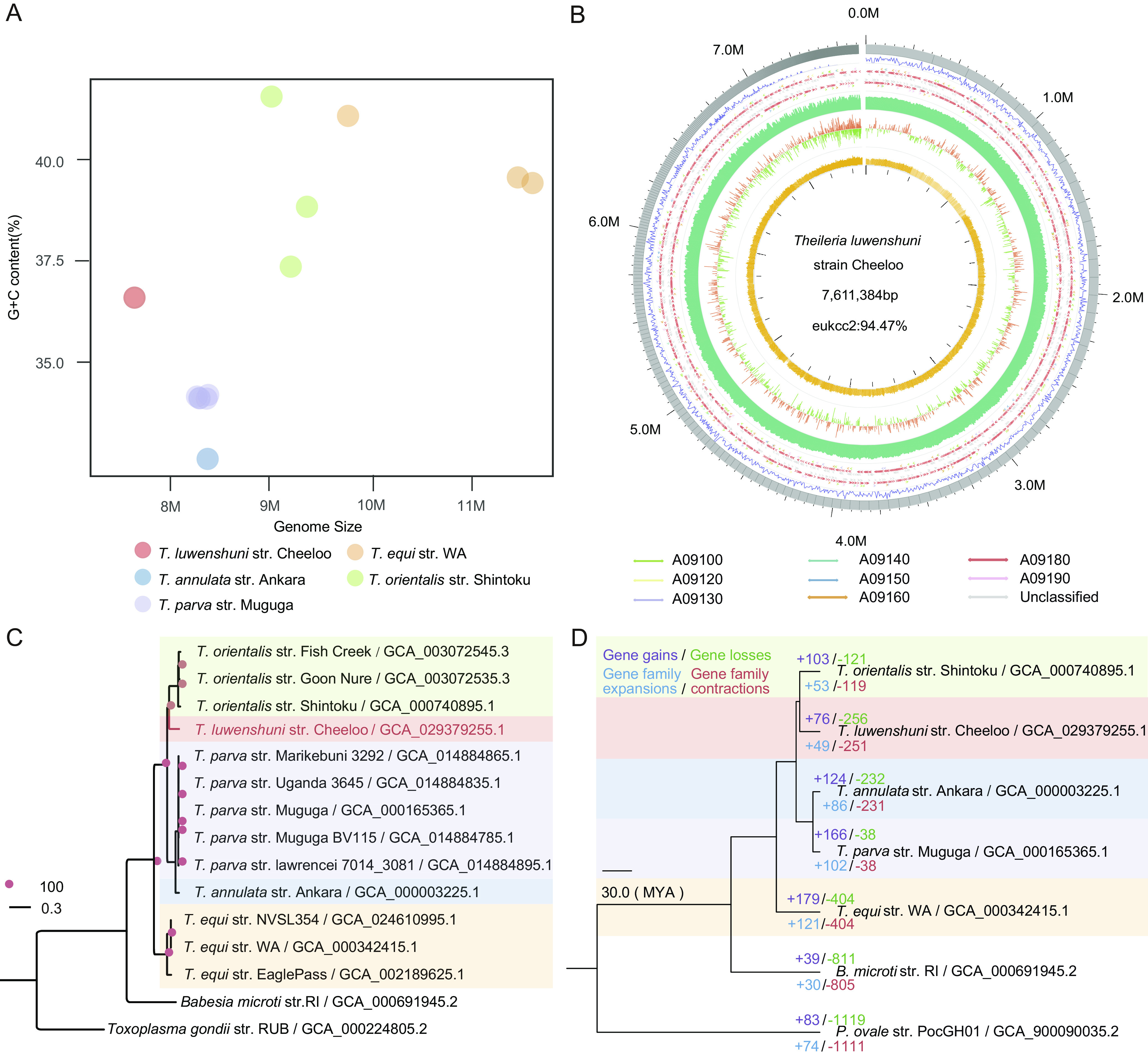

The genome of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo was approximately 7.61 Mb in size with 94.47% gene integrity, which was smallest in comparison to those of the other four identified Theileria species (Table 1), including T. annulata str. Ankara (6), T. equi str. WA (26), T. orientalis str. Shintoku (5), and T. parva str. Muguga (25). After removing bacterial sequences, the estimated genome size of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo was 7,642,037 bp (Fig. S2), which was comparable to the assembled genome. Total number of contigs in this assembly was 658, the minimum and maximum contig lengths were 504 bp and 363,912 bp, with L50 and N50 being 41 and 52,164 bp, respectively (Table 1). MetaEuk was used to predict proteins, and 3,408 putative protein-coding genes were identified in the genome. The G+C content of the T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo genome was 36.55%. There was no obvious association between genome size and G+C content of different Theileria species, whose complete genome sequences were available (Fig. 2A). Although the genome size of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo was smaller than those of T. annulata and T. parva, it had higher G+C content than the other two Theileria species.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of genome characteristics of the genus Theileria

| Features | T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo | T. annulata str. Ankara | T. equi str. WA | T. orientalis str. Shintoku | T. parva str. Muguga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (Mb) | 7.61 | 8.36 | 11.67 | 9.01 | 8.35 |

| G+C content (%) | 36.55 | 32.54 | 39.48 | 41.55 | 34.04 |

| No. of contigs | 658 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 9 |

| Min contig length (bp) | 504 | 5,905 | 9,001 | 2,595 | 13,275 |

| Max contig length (bp) | 363,912 | 2,592,520 | 3,677,484 | 2,746,313 | 2,540,030 |

| L 50 | 41 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| N50 (bp) | 52,164 | 1,979,170 | 2,338,319 | 2,216,979 | 1,971,884 |

| No. of protein-coding genes | 3408 | 3796 | 5329 | 4002 | 4051 |

| Avg protein-coding genes length (bp) | 1,344 | 1,605 | 1,473 | 1,541 | 1,467 |

| % of genes with introns | 68.1 | 69 | 51.3 | 76.6 | 70.2 |

| Mean gene length (bp) | 1,561 | 1,775 | 1,682 | 1,842 | 1,878 |

| % coding | 60.2 | 72.8 | 67.1 | 68.3 | 71.1 |

| % G+C composition of exons | 41.16 | 35.71 | 39.69 | 46.18 | 37.74 |

| Gene density (genome size/no. of protein-coding genes) | 2233 | 2202 | 2190 | 2251 | 2060 |

| Busco of protein mode (%) | 85.1 (F:6.3, M:8.6) | 93.5 (F:2.7, M:3.8) | 94.6 (F:3.6, M:1.8) | 94.2 (F:2.5, M:3.3) | 98.2 (F:0.5, M:1.3) |

FIG 2.

Genomic composition and evolution of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. (A) Genome size and G+C content distribution of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and the other four Theileria species with published complete genome sequences. Different Theileria species were indicated with different colors. (B) Bird’s eye view of the assembled genome of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo showing summary statistics. From the outer circle to the inner circle, six types of information: contig length, genes density, gene annotation (colors imply the KEGG of genes, A09100 Metabolism; A09120 Genetic Information Processing; A09130 Environmental Information Processing; A09140 Cellular Processes; A09150 Organismal Systems; A09160 Human Diseases; A09180 Brite Hierarchies; A09190 Not Included in Pathway or Brite), DNA sequencing data coverage, G+C skew value, and G+C content are labeled. (C) The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Theileria species. The tree was inferred by Raxml based on 1,149 single-copy orthologs identified by orthofinder. A total of 1,000 alternative runs were used to calculate support values. Babesia microti and Toxoplasma gondii were two outgroup species to help root the tree. Different Theileria species were indicated with different colors. (D) An ultrametric tree of five Theileria species, with Babesia microti str. RI and Plasmodium ovale str. PocGH01 as the tree root. Numbers below the branches indicate gene family expansions/contractions, and the numbers above the branches show gene gains/losses.

The description scheme with bird’s eye view demonstrated the basic composition of the T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo genome (Fig. 2B). From the outer to the inner circle, the scheme displayed the contig length, gene density, gene annotation, sequencing data coverage, G+C skew value, and G+C content. The phylogenetic analysis based on the complete genome sequences of Theileria species published revealed that T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo occupied a separate evolutionary lineage distinct from the other four Theileria species and was genetically close to T. orientalis and distant to T. equi (Fig. 2C). We constructed the ultrametric tree based on the whole-genome sequences of five Theileria species, Babesia microti str. RI, and Plasmodium ovale str. PocGH01 (Fig. 2D). Based on the 233 million years ago (MYA) of median divergence time between P. ovale str. PocGH01 and B. microti str. RI, the divergence time between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and T. orientalis str. Shintoku was about 21 million years ago, which range from 1.8 to 56.7 million years with different calibration points. Notably, T. luwenshuni possessed the fewest gene gains and gene family expansion among all the five species, followed by its genetically close species T. orientalis. But it had the second most gene losses and gene family contraction just after T. equi, which was genetically most distant to T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. Considering the potential poor spaces in assembly, we conducted the genome synteny analysis between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and T. orientalis, which are genetically closest to each other. The poor spaces were discovered at the ends of both genomes (Fig. S3). Notably, the difference in many regions of the whole genomes was obvious between the two Theileria species. This finding indicates the small size of the T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo genome is unlikely caused by any gene missing.

To better illustrate the evolutionary relationships between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and other Theileria species, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on 145 Theileria 18S rRNA genes available in GenBank (Fig. S4). T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo was on the same lineage with some unclassified Theileria species as well as T. luwenshuni. They were clustered with Theileria species identified mostly in small ruminants, including Theileria ovis, Theileria capreoli, and Theileria cervi, hosts of which are sheep and other wild ruminants, including water deer, horse deer, reindeer, Odocoileus virginianus, etc. (27–30).

Genome annotation and characterization of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo in comparison to other Theileria species.

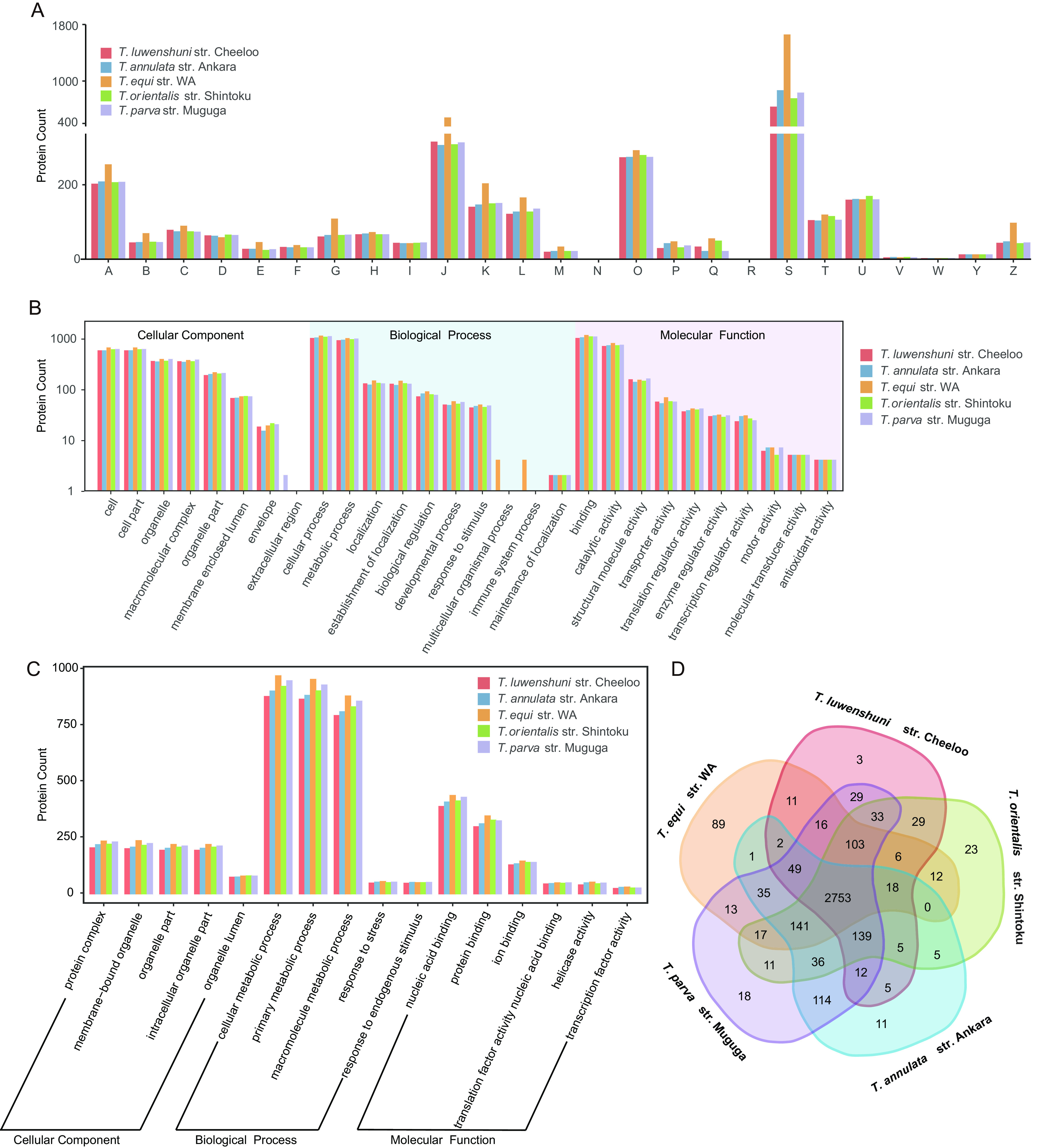

To characterize the genome of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and compare the differences in protein-coding genes, we annotated the genes using three different approaches respectively, based on Eukaryote Orthologs (KOG), Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). The functional categories of coding proteins of each Theileria species based on KOG annotation are listed in Table S2 and visualized in the bar graphs (Fig. 3A). Overall, the proteins with unknown function had highest counts among all the five species, accounting for 18.72%, 22.92%, 31.13%, 18.89%, and 20.66% of total encoded proteins of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo, T. annulata str. Ankara, T. equi str. WA, T. orientalis str. Shintoku, and T. parva str. Muguga, respectively. Among the protein with known function, the top five categories included “RNA processing and modification,” “translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis,” “posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones,” and “transcription” followed by “intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport,” “signal transduction mechanisms,” and “replication, recombination, and repair.” Notably, the protein count of each category was always comparable between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and T. orientalis str. Shintoku (Fig. 3A), though there were remarkable differences in genome size (7.61 Mb versus 9.01 Mb) and in protein count (3,408 versus 4,002) (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Genome annotation and characterization of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo in comparison to other Theileria species. (A) KOG analysis of all predicted genes. The x axis indicates KOG categories and the y axis indicates the number of proteins. The x axis A to W represent: A, RNA processing and modification; B, chromatin structure and dynamics; C, energy production and conversion; D, cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning; E, amino acid transport and metabolism; F, nucleotide transport and metabolism; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H, coenzyme transport and metabolism; I, lipid transport and metabolism; J, translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; K, transcription; L, replication, recombination and repair; M, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; N, cell motility; O, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction mechanisms; U, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport; V, defense mechanisms; W, extracellular structures. Y and Z represent nuclear structure and cytoskeleton, respectively. (B) Gene ontology (GO) terms assignment for proteins from five Theileria species at level 2. Results are summarized into three categories of cellular component, molecular function, and biological process. (C) GO terms with differential protein counts at level 3. (D) Venn diagram showing number of orthogroups found in different Theileria species.

For further GO annotation, considering that the export format of eggNOG did not meet the requirements, InterProScan was chosen to perform the structural domain similarity comparison between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and the other four species. We initially summarized GO categories at level 2, involving Cellular Component, Biological Process, and Molecular Function (Fig. 3B). In the Cellular Component category, the protein counts involving cell, cell part, organelle, macromolecular complex, organelle part, membrane enclosed lumen, and envelope of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo were comparable to the other four Theileria species. The extracellular region was only available for T. parva str. Muguga, but not for the other four Theileria species. There was no significant difference in protein counts regarding the cellular process, metabolic process, localization, establishment of localization, biological regulation, developmental process, response to stimulus, and maintenance of localization section in the Biological Process category, between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and the other four Theileria. Only T. equi had proteins involving multicellular organismal process and immune system process. All the contents under the Molecular Function category, including binding, catalytic activity, structural molecule activity, transporter activity, translation regulator activity, enzyme regulator activity, transcription regulator activity, motor activity, molecular transducer activity, and antioxidant activity, were also similar among T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and the other four Theileria species.

Furthermore, a bar graph was created to clarify the differences in more detail between T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo and the other four species at level 3 (Fig. 3C). In the Cellular Component category, the protein complex, membrane-bound organelle part, organelle part, and intracellular organelle part in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo were lower than the other four Theileria species, with T. equi str. WA being the highest. In the Biological Process category, the cellular metabolic process, primary metabolic process, and macromolecule metabolic process sections in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo were much lower than the other four Theileria species. Regarding the response to stress and endogenous stimulus, T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo did not significantly differ from the other four Theileria species. The annotation results under the Molecular Function category, including nucleic acid binding, protein binding, ion binding, translation factor activity nucleic acid binding, and transcription factor activity, were lower for T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo than for the other four species.

Orthogroups of Theileria species are presented in the Venn diagram (Fig. 3D). All the five species in the genus Theileria shared 2,753 orthogroups in common. T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo processed three unique orthogroups with unknown functions and shared 29 orthogroups with its most closely related T. orientalis str. Shintoku, which were absent in T. equi str. WA, T. parva str. Muguga, and T. annulata str. Ankara. In addition, T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo shared 29, 11, and 5 orthogroups with T. parva str. Muguga, T. equi str. WA, and T. annulata str. Ankara, respectively. Compared with other members of the genus Theileria, 141 orthogroups in the other four species were absent in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo.

Absence of the c-Myb in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo.

Sustained activation of NF-κB, which saves cells from spontaneous apoptosis, can activate the expression of target genes (31). Intracellular protozoans have evolved a plethora of mechanisms to ensure their dissemination and escape hostile host responses. Theileria is the only eukaryote known to induce uncontrolled proliferation of host cells. The survival or apoptosis of Theileria-transformed leukocytes is strictly dependent on NF-κB activity (32). c-Myb is present at the end of the NF-κB signaling pathway and is a DNA-binding transcription factor that has functions in apoptosis, proliferation and differentiation (33, 34). In this study, we found that T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo lacked c-Myb by KEGG annotation, which is presented in all other four Theileria species. We designed four sets of primers based on the c-Myb in other Theileria species (Table S1), none of which could be amplified from the original samples.

Prevalence and evolution of T. luwenshuni in goats.

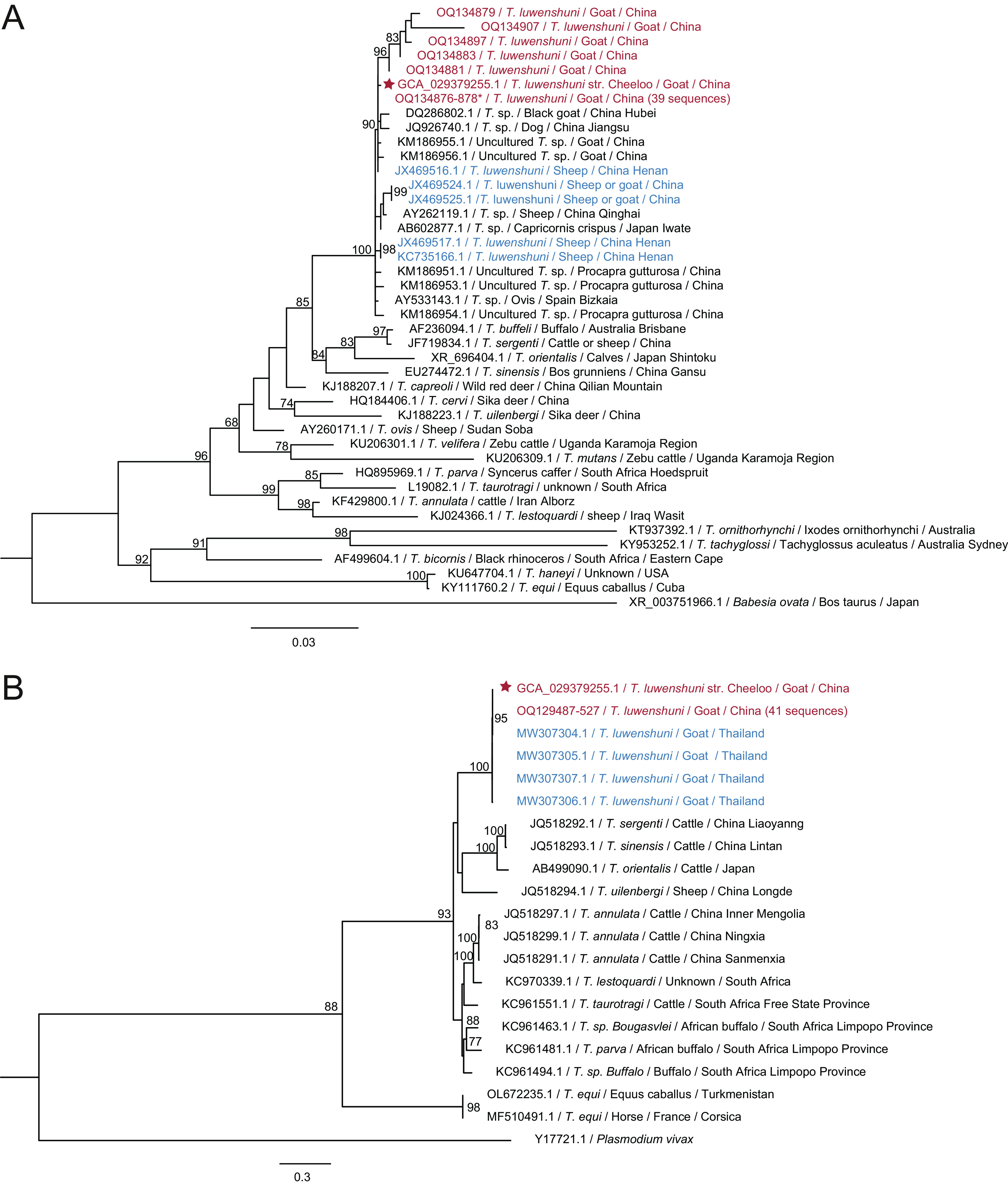

We tested T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo in blood samples from 54 goats of three flocks at Shandong Province of eastern China (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) by PCR assays using specific primers targeting 18S rRNA gene (1,745 bp) and the partial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene (602 bp) of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo (Table S1) followed by Sanger sequencing. The overall positive rate was up to 81.5% (95% CI, 71.1% to 91.8%). The 18S rRNA genes sequences of Theileria detected in the goats of this study (GenBank accession no. OQ134876 to OQ134919) showed an average similarity of over 99.8% with each other. The phylogenetic analysis based on the 18S rRNA genes revealed that all the sequences together with the 18S rRNA gene sequence of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo were clustered in a separate lineage of the same clade with T. luwenshuni and unclassified Theileria species in ruminants from China, Japan, and Spain (Fig. 4A). The cox1 gene sequence (602 bp) amplified from 41 goat samples (GenBank accession no. OQ129487 to OQ129527) in this study had 99.8% to 100% identity to each other and to the corresponding region of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. The phylogenetic tree based on the cox1 gene indicated that T. luwenshuni detected in the goats and T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo were clustered with T. luwenshuni (GenBank accession no. MW307304.1) detected in goats from Thailand (35) in the same clade, further proving T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo as a T. luwenshuni species (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo based on the full-length of the 18S rRNA gene and the partial cox1 gene. (A) Phylogenetic tree of Theileria based on 18S rRNA gene sequences. (B) Phylogenetic tree of Theileria based on cox1 gene sequences. The sequences obtained in this study are highlighted in red. The stars in panels A and B indicate the sequences from the assembled genome of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. The asterisk (*) indicates the 18S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study with GenBank accession numbers of OQ134880, OQ134882, OQ134884 to OQ134896, OQ134898 to OQ134906, and OQ134908 to OQ134919.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we initially detected T. luwenshuni by PCR in goats during a survey on tick-borne agents, observed by microscopic examination of Wright-Giemsa staining slides, and confirmed by FISH using a specific probe. After directed metagenomic next-generation sequencing of an infected goat blood sample, we then assembled a complete genome sequence of Theileria, designated T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. This is the genome of the fifth Theileria species obtained in the world. Whole-genome assembly of intracellular parasites has usually been prohibited by the DNA presence of host cells. Considering T. luwenshuni is only observed in erythrocytes by Wright-Giemsa staining and FISH, we first separated erythrocytes from the infected goat blood, and then lysed them for maximum removal of goat DNA. After metagenomic sequencing, the remaining goat genomic sequences were further discarded, and the T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo genome was successfully assembled from the infected goat. The gene integrity is up to 94.47%. The phylogenetic analysis based on the Theileria genome sequences, and the comparative analyses of genomic characteristics revealed that T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo is distinct from the other four Theileria species, and more closely related to T. orientalis.

A morphological test has been traditionally applied for diagnosing protozoan infections, but sometimes is not specific. FISH tests using probes have been used for specific identification of protozoans such as Plasmodium and Babesia (36, 37). In this study, we developed a specific FISH assay for T. luwenshuni. Furthermore, we simultaneously stained the nucleus using DAPI to verify the morphological features of Theileria through fluorescence microscopy. The morphology of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo within the erythrocytes is diverse, with various shapes such as rod-shaped, ovoid, and pear-shaped. Previous studies have indicated that upon entry into the host, some Theileria species initially undergo schizont proliferation in host leukocytes, forming multinucleated schizonts, which further develop into a uninucleate merozoite stage. The merozoites are released from the leukocytes and invade the erythrocytes, subsequently becoming piroplasms (38–41). To date, schizonts have been directly observed in leukocytes of bovines infected with T. annulata, T. parva, and T. orientalis (41, 42). In our study, no schizont is visualized in the leukocytes of goats infected with T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo by either Wright-Giemsa staining or FISH. We are uncertain whether T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo has an intraleukocyte schizont stage in the peripheral blood, as previously observed in other Theileria species infecting bovines (43).

The genomic composition of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo has some distinct features compared with the other four Theileria species. The genome size of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo is smallest (around 7.61 Mb) among the Theileria genomes assembled until now. T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo shares more genes with both T. orientalis and T. parva that are not present in the other two Theileria species. T. luwenshuni and T. orientalis are closer in evolutionary distance and time than the other three Theileria species, which may explain why they share the more protein-coding genes. Theileria luwenshuni str. Cheeloo processes fewer protein-coding genes than the other four Theileria species in the Cellular Component classification at level 3 of the GO annotation, involving membrane-bound organelle, organelle, and intracellular organelle. These data will undoubtedly improve our understanding of the gene function of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo. Notably, KEGG annotation reveals the absence of c-Myb in T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo, indicating it might have different mechanisms in comparison with other Theileria species in apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation (33, 34).

The infection rate of T. luwenshuni is up to 81.5% in goats from Shandong Province of eastern China, which is higher than those detected in Chinese Cervidae from northwestern China, and small ruminant from central and northwestern China (9, 10, 44). The reason for the high prevalence in goats of Shandong Province might be due to sampling bias. On the other hand, the finding might indicate the higher infectivity of T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo, which needs further experimental studies to prove this hypothesis. We further did the phylogenetic analyses based on both 18S rRNA and cox1 genes of Theileria by including more sequences from different animal hosts and found that T. luwenshuni from different hosts and geographic locations were always clustered in the same clade that is more genetically close to those detected from ruminants. This finding is consistent with the results demonstrated by some previous studies (45, 46), suggesting a low genetic diversity of T. luwenshuni.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and DNA extraction.

In the present study, goat blood samples were collected in Shandong Province of eastern China in September 2021 and July 2022. A total of 54 EDTA blood samples were collected from three flocks of goats. Eleven samples were collected from one flock of goats for the first collection and 43 blood samples (six of the blood samples were from the same site as the first collection) were collected from three flocks of goats for the second collection (Fig. S1). A High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche, Germany) was used for DNA extraction from blood samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR amplification and sequencing.

A PCR assay specific for the 18S rRNA gene of Theileria and Babesia was conducted (Table S1) to screen the goat blood samples of the first flock, as previously described (47). The primers specific for the c-Myb gene were designed according to the conserved regions of the four Theileria species with published genomes (Table S1) and used for amplification of the gene from goat blood samples. All 54 blood samples were amplified for 18S rRNA and cox1 gene by PCR assays (Table S1). All amplicons were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Wright-Giemsa staining.

Blood smears were prepared on the day of collection, followed by fixation with methanol for 15 to 20 min and drying at room temperature. After the staining was completed, the slides were tilted at 45 degrees, rinsed slowly with water of pH close to neutral, washed of the excess staining solution, and then dried and placed under the microscope for observation.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

We used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to observe T. luwenshuni on blood smears. FISH probes were designed using 18S rRNA sequences obtained from the whole genome of the T. luwenshuni str. Cheeloo (Table S3) labeled with FAM. Blood smears that had been fixed in methanol and stained with Wright-Giemsa were first soaked in 70% ethanol, incubated overnight at 4°C, and then the ethanol was aspirated. The pooled FISH probes were resuspended in a final concentration of 12.5 μM in RNase-free storage buffer and protected from light by storage at −20°C. FISH was performed on the prepared blood smear with a commercial kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biosearch Technologies, California, America). Finally, a drop of fluorescent antibody blocker containing DAPI was placed on the slide, then the slide was covered with a coverslip, incubated for 2 h at room temperature, and observed under a fluorescence microscope (DAPI and FITC channels).

Enrichment of Theileria for genomic sequencing.

Erythrocytes from Theileria-infected goats were separated by gradient centrifugation using cell separation solution (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 min at 200 × g at 4°C. Then, four times volume of precooled (4°C) erythrocyte lysis buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added to the isolated erythrocytes by gentle pipetting to ensure adequate mixing. After placing at 4°C for 10 min, the lysis solution was centrifuged at 350 × g for 10 min to remove residual blood cells. Finally, the supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. The pooled Theileria was resuspended for DNA extraction using the High Pure PCR template preparation kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Genome assembly and quality assessment.

A sequencing library was then constructed using the AxyPrep Mag PCR clean up kit for MGI Tech Co., Ltd. Then the sequencing library was prepared according to the Whole Genome Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol (DNBSEQ). The paired-end (PE) libraries were sequenced with a read length of 2 × 150 bp on a DNBseq-T7 platform at Grandomics Gene Technology Beijing Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). High-quality reads were aligned to the goat (Capra hircus) genome (GenBank assembly accession no. GCA_001704415.2) using bowtie2 v2.4.1 (48) with default parameters, to remove the genome sequence of the host. Both members of a read pair were discarded if one read matched the C. hircus genome by using Samtools v1.9 (49) with parameters -f 12 with 4.1% of reads retained. The remaining reads were sent to SPAdes v3.15.2 (50) with parameters -meta to assemble the Theileria genome. Binning and genome reconstruction were accomplished by MetaBAT2 v2:2.15 (51). EukCC v2.1.0 (52) was used to evaluate the completeness of the assembly. The quality of genome assembly was evaluated by QUAST (53). K-mer counting was implemented by Jellyfish (54). The genomescope2 (55) was then used to estimate genome size.

Phylogenetic analyses.

The sequences of published complete genome sequences of Theileria species, including T. annulata str. Ankara, T. equi str. WA, T. orientalis str. Shintoku, and T. parva str. Muguga, were downloaded from NCBI. B. microti and T. gondii were selected as outgroups.

The required 18S rRNA and cox1 gene sequences were also downloaded from NCBI, and multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was then performed using MEGA11. Finally, the maximum likelihood method was used to construct phylogenetic trees.

Divergence time estimation.

Gene families were identified using OrthoFinder v2.5.4 (56) with default parameters among 12 Theileria species and two outgroup species. Proteins from single-copy gene families (n = 1,176) were used for subsequent phylogenetic analysis. The protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8.1551 (57). Gblocks v0.91b (58) was used to select conserved blocks from aligned sequences. Raxml v8.2.12 (59) was used to generate a phylogenomic tree. The phylogenomic tree used for divergence time predict was built with same pipeline as described above. The divergence time was estimated by r8s (60) using the divergence time of B. microti str. RI and P. ovale str. PocGH01 from the TimeTree website (61). CAFE (62) was used to identify gene family expansion and contraction.

Protein prediction and annotation.

Protein prediction was accomplished by metaEuk v5.34 (63) with default parameters. Busco v4.1.2 with protein mode (64) was used to investigate the accuracy of gene annotation. G+C content and G+C skew value were calculated by GCcalc v1.0.0. InterProScan v5.57-90.0 (65) was used to obtain protein function classification. GO annotations analyzing and plotting were achieved by WEGO v2.0 (66). The GO annotation at both level 2 and level 3 were used to characterize protein-coding genes. KEGG annotation was applied by KofamScan v1.3.0 (67).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (81621005, W.-C.C.; 82103897, L.Z.), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2020QH299, L.Z.), Cheeloo Young Scholar Program of Shandong University, the National key research and development program of China (2022YFC260280005 and 2021YFC2302001, X.-M.C.).

We declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Ming Cui, Email: cuixm7@163.com.

Lin Zhao, Email: zhaolin1989@sdu.edu.cn.

Wu-Chun Cao, Email: caowuchun@126.com.

Michael L. Ginger, University of Huddersfield

REFERENCES

- 1.Bishop R, Musoke A, Morzaria S, Gardner M, Nene V. 2004. Theileria: intracellular protozoan parasites of wild and domestic ruminants transmitted by ixodid ticks. Parasitology 129 Suppl:S271–83. doi: 10.1017/s0031182003004748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivakumar T, Hayashida K, Sugimoto C, Yokoyama N. 2014. Evolution and genetic diversity of Theileria. Infect Genet Evol 27:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal A, Chakravarty AK. 2020. Chapter 2 - major diseases of livestock and poultry and problems encountered in controlling them. Genetics and Breeding for Disease Resistance of Livestock:11–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tretina K, Pelle R, Orvis J, Gotia HT, Ifeonu OO, Kumari P, Palmateer NC, Iqbal SBA, Fry LM, Nene VM, Daubenberger CA, Bishop RP, Silva JC. 2020. Re-annotation of the Theileria parva genome refines 53% of the proteome and uncovers essential components of N-glycosylation, a conserved pathway in many organisms. BMC Genomics 21:279. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashida K, Hara Y, Abe T, Yamasaki C, Toyoda A, Kosuge T, Suzuki Y, Sato Y, Kawashima S, Katayama T, Wakaguri H, Inoue N, Homma K, Tada-Umezaki M, Yagi Y, Fujii Y, Habara T, Kanehisa M, Watanabe H, Ito K, Gojobori T, Sugawara H, Imanishi T, Weir W, Gardner M, Pain A, Shiels B, Hattori M, Nene V, Sugimoto C. 2012. Comparative genome analysis of three eukaryotic parasites with differing abilities to transform leukocytes reveals key mediators of Theileria-induced leukocyte transformation. mBio 3:e00204-12–e00212. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00204-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pain A, Renauld H, Berriman M, Murphy L, Yeats CA, Weir W, Kerhornou A, Aslett M, Bishop R, Bouchier C, Cochet M, Coulson RM, Cronin A, de Villiers EP, Fraser A, Fosker N, Gardner M, Goble A, Griffiths-Jones S, Harris DE, Katzer F, Larke N, Lord A, Maser P, McKellar S, Mooney P, Morton F, Nene V, O'Neil S, Price C, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rawlings ND, Rutter S, Saunders D, Seeger K, Shah T, Squares R, Squares S, Tivey A, Walker AR, Woodward J, Dobbelaere DA, Langsley G, Rajandream MA, McKeever D, Shiels B, Tait A, Barrell B, Hall N. 2005. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science 309:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byaruhanga C, Collins NE, Knobel D, Chaisi ME, Vorster I, Steyn HC, Oosthuizen MC. 2016. Molecular investigation of tick-borne haemoparasite infections among transhumant zebu cattle in Karamoja Region, Uganda. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep 3-4:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaisi ME, Sibeko KP, Collins NE, Potgieter FT, Oosthuizen MC. 2011. Identification of Theileria parva and Theileria sp. (buffalo) 18S rRNA gene sequence variants in the African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in southern Africa. Vet Parasitol 182:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Chen Z, Liu Z, Liu J, Yang J, Li Q, Li Y, Cen S, Guan G, Ren Q, Luo J, Yin H. 2014. Molecular identification of Theileria parasites of northwestern Chinese Cervidae. Parasit Vectors 7:225. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, Chen Z, Yang J, He H, Guan G, Liu A, Ren Q, Niu Q, Liu J, Luo J, Yin H. 2014. An epidemiological survey of Theileria infections in small ruminants in central China. Vet Parasitol 200:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagore D, Garcia-Sanmartin J, Garcia-Perez AL, Juste RA, Hurtado A. 2004. Identification, genetic diversity and prevalence of Theileria and Babesia species in a sheep population from Northern Spain. Int J Parasitol 34:1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin H, Schnittger L, Luo J, Seitzer U, Ahmed JS. 2007. Ovine theileriosis in China: a new look at an old story. Parasitol Res 101 Suppl 2:S191–5. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnittger L, Yin H, Gubbels MJ, Beyer D, Niemann S, Jongejan F, Ahmed JS. 2003. Phylogeny of sheep and goat Theileria and Babesia parasites. Parasitol Res 91:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0979-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongruel ACB, Medici EP, da Costa Canena A, Calchi AC, Perles L, Rodrigues BCB, Soares JF, Machado RZ, André MR. 2022. Theileria terrestris nov. sp.: a novel theileria in lowland Tapirs (Tapirus terrestris) from two different biomes in Brazil. Microorganisms 10:2319. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10122319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baghel KR, Saravanan BC, Jeeva K, Chandra D, Singh KP, Ghosh S, Tewari AK. 2023. Oriental theileriosis associated with a new genotype of Theileria orientalis in buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) calves in Uttar Pradesh, India. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 14:102077. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam MK, Jabbar A, Campbell BE, Cantacessi C, Gasser RB. 2011. Bovine theileriosis–an emerging problem in south-eastern Australia? Infect Genet Evol 11:2095–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aparna M, Ravindran R, Vimalkumar MB, Lakshmanan B, Rameshkumar P, Kumar KG, Promod K, Ajithkumar S, Ravishankar C, Devada K, Subramanian H, George AJ, Ghosh S. 2011. Molecular characterization of Theileria orientalis causing fatal infection in crossbred adult bovines of South India. Parasitol Int 60:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikawa K, Aoki M, Ichikawa M, Itagaki T. 2011. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Theileria species detected from Japanese serows (Capricornis crispus) in Iwate Prefecture, Japan. J Vet Med Sci 73:1359–1361. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gubbels MJ, Hong Y, van der Weide M, Qi B, Nijman IJ, Guangyuan L, Jongejan F. 2000. Molecular characterisation of the Theileria buffeli/orientalis group. Int J Parasitol 30:943–952. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnittger L, Yin H, Qi B, Gubbels MJ, Beyer D, Niemann S, Jongejan F, Ahmed JS. 2004. Simultaneous detection and differentiation of Theileria and Babesia parasites infecting small ruminants by reverse line blotting. Parasitol Res 92:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0980-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allsopp MT, Cavalier-Smith T, De Waal DT, Allsopp BA. 1994. Phylogeny and evolution of the piroplasms. Parasitology 108:147–152. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000068232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paparini A, Macgregor J, Ryan UM, Irwin PJ. 2015. First molecular characterization of Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959: yet another challenge to the systematics of the piroplasms. Protist 166:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop RP, Kappmeyer LS, Onzere CK, Odongo DO, Githaka N, Sears KP, Knowles DP, Fry LM. 2020. Equid infective Theileria cluster in distinct 18S rRNA gene clades comprising multiple taxa with unusually broad mammalian host ranges. Parasit Vectors 13:261. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ullah K, Numan M, Alouffi A, Almutairi MM, Zahid H, Khan M, Islam ZU, Kamil A, Safi SZ, Ahmed H, Tanaka T, Ali A. 2022. Molecular characterization and assessment of risk factors associated with Theileria annulata Infection. Microorganisms 10:1614. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10081614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner MJ, Bishop R, Shah T, de Villiers EP, Carlton JM, Hall N, Ren Q, Paulsen IT, Pain A, Berriman M, Wilson RJ, Sato S, Ralph SA, Mann DJ, Xiong Z, Shallom SJ, Weidman J, Jiang L, Lynn J, Weaver B, Shoaibi A, Domingo AR, Wasawo D, Crabtree J, Wortman JR, Haas B, Angiuoli SV, Creasy TH, Lu C, Suh B, Silva JC, Utterback TR, Feldblyum TV, Pertea M, Allen J, Nierman WC, Taracha EL, Salzberg SL, White OR, Fitzhugh HA, Morzaria S, Venter JC, Fraser CM, Nene V. 2005. Genome sequence of Theileria parva, a bovine pathogen that transforms lymphocytes. Science 309:134–137. doi: 10.1126/science.1110439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kappmeyer LS, Thiagarajan M, Herndon DR, Ramsay JD, Caler E, Djikeng A, Gillespie JJ, Lau AO, Roalson EH, Silva JC, Silva MG, Suarez CE, Ueti MW, Nene VM, Mealey RH, Knowles DP, Brayton KA. 2012. Comparative genomic analysis and phylogenetic position of Theileria equi. BMC Genomics 13:603. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Guan G, Ma M, Liu J, Ren Q, Luo J, Yin H. 2011. Theileria ovis discovered in China. Exp Parasitol 127:304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uilenberg G. 1981. Theilerial Species of Domestic Livestock, p 4–37. In Irvin AD, Cunningham MP, Young AS (ed), Advances in the Control of Theileriosis: Proceedings of an International Conference held at the International Laboratory for Research on Animal Diseases in Nairobi, 9–13th February, 1981 doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-8346-5_2. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hornok S, Sugar L, Horvath G, Kovacs T, Micsutka A, Gonczi E, Flaisz B, Takacs N, Farkas R, Meli ML, Hofmann-Lehmann R. 2017. Evidence for host specificity of Theileria capreoli genotypes in cervids. Parasit Vectors 10:473. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2403-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chae JS, Waghela SD, Craig TM, Kocan AA, Wagner GG, Holman PJ. 1999. Two Theileria cervi SSU RRNA gene sequence types found in isolates from white-tailed deer and elk in North America. J Wildl Dis 35:458–465. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-35.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobbelaere DAE, Fernandez PC, Heussler VT. 2000. Theileria parva: taking control of host cell proliferation and survival mechanisms. Cell Microbiol 2:91–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heussler VT, Rottenberg S, Schwab R, Kuenzi P, Fernandez PC, McKellar S, Shiels B, Chen ZJ, Orth K, Wallach D, Dobbelaere DA. 2002. Hijacking of host cell IKK signalosomes by the transforming parasite Theileria. Science 298:1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1075462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh IH, Reddy EP. 1999. The myb gene family in cell growth, differentiation and apoptosis. Oncogene 18:3017–3033. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weston K. 1998. Myb proteins in life, death and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8:76–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tu HLC, Nugraheni YR, Tiawsirisup S, Saiwichai T, Thiptara A, Kaewthamasorn M. 2021. Development of a novel multiplex PCR assay for the detection and differentiation of Plasmodium caprae from Theileria luwenshuni and Babesia spp. in goats. Acta Trop 220:105957. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.105957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albertyńska M, Okła H, Jasik K, Urbańska-Jasik D, Pol P. 2021. Interactions between Babesia microti merozoites and rat kidney cells in a short-term in vitro culture and animal model. Sci Rep 11:23663. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03079-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah JS, Ramasamy R. 2022. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) tests for identifying protozoan and bacterial pathogens in infectious diseases. Diagnostics (Basel) 12:1286. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tretina K, Gotia HT, Mann DJ, Silva JC. 2015. Theileria-transformed bovine leukocytes have cancer hallmarks. Trends Parasitol 31:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uilenberg G. 2006. Babesia–a historical overview. Vet Parasitol 138:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mans BJ, Pienaar R, Latif AA. 2015. A review of Theileria diagnostics and epidemiology. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl 4:104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehlhorn H, Shein E. 1984. The piroplasms: life cycle and sexual stages. Adv Parasitol 23:37–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart NP, De Vos AJ, McGregor W, Shiels IA. 1988. Observations on the development of tick-transmitted Theileria buffeli (syn T orientalis?) in cattle. Res Vet Sci 44:338–342. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5288(18)30868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugimoto C, Fujisaki K. 2002. Non-transforming Theileria parasites of ruminants, p 93–106. In Dobbelaere DAE, McKeever DJ (ed), Theileria doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0903-5_7. Springer US, Boston, MA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Liu Z, Yang J, Chen Z, Guan G, Ren Q, Liu A, Luo J, Yin H, Li Y. 2014. Multiplex PCR for diagnosis of Theileria uilenbergi, Theileria luwenshuni, and Theileria ovis in small ruminants. Parasitol Res 113:527–531. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed JS, Luo J, Schnittger L, Seitzer U, Jongejan F, Yin H. 2006. Phylogenetic position of small-ruminant infecting piroplasms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1081:498–504. doi: 10.1196/annals.1373.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnittger L, Hong Y, Jianxun L, Ludwig W, Shayan P, Rahbari S, Voss-Holtmann A, Ahmed JS. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis by rRNA comparison of the highly pathogenic sheep-infecting parasites Theileria lestoquardi and a Theileria species identified in China. Ann N Y Acad Sci 916:271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang JF, Zheng YC, Jiang RR, Li H, Huo QB, Jiang BG, Sun Y, Jia N, Wang YW, Ma L, Liu HB, Chu YL, Ni XB, Liu K, Song YD, Yao NN, Wang H, Sun T, Cao WC. 2015. Epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of 48 cases of “Babesia venatorum” infection in China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:196–203. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO, Whitwham A, Keane T, McCarthy SA, Davies RM, Li H. 2021. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. 2017. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res 27:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gr.213959.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang DD, Li F, Kirton E, Thomas A, Egan R, An H, Wang Z. 2019. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7:e7359. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saary P, Mitchell AL, Finn RD. 2020. Estimating the quality of eukaryotic genomes recovered from metagenomic analysis with EukCC. Genome Biol 21:244. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marçais G, Kingsford C. 2011. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ranallo-Benavidez TR, Jaron KS, Schatz MC. 2020. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun 11:1432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emms DM, Kelly S. 2019. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol 20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castresana J. 2000. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanderson MJ. 2003. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19:301–302. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. 2017. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol Biol Evol 34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. 2006. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levy Karin E, Mirdita M, Soding J. 2020. MetaEuk-sensitive, high-throughput gene discovery, and annotation for large-scale eukaryotic metagenomics. Microbiome 8:48. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00808-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ye J, Zhang Y, Cui H, Liu J, Wu Y, Cheng Y, Xu H, Huang X, Li S, Zhou A, Zhang X, Bolund L, Chen Q, Wang J, Yang H, Fang L, Shi C. 2018. WEGO 2.0: a web tool for analyzing and plotting GO annotations, 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W71–W75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aramaki T, Blanc-Mathieu R, Endo H, Ohkubo K, Kanehisa M, Goto S, Ogata H. 2020. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36:2251–2252. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download spectrum.00301-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 4.3 MB (4.3MB, pdf)