Abstract

Cervical cancer remains a significant global health challenge, and there is a need for innovative drug delivery systems to improve the efficacy of anticancer drugs. In this study, we developed and evaluated boronated chitosan/alginate nanoparticles (BCHIALG NPs) as a localized mucoadhesive drug delivery system for cervical cancer. Boronated chitosan (BCHI) was synthesized by incorporating 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid onto chitosan (CHI), and boronated chitosan/alginate nanoparticles (BCHIALG NPs) with varying polymer ratios were prepared using an ionic gelation method. The physical properties, drug loading capacity/encapsulation efficiency, mucoadhesive properties, and in vitro drug release profile of the nanoparticles were evaluated. The BCHIALG NPs exhibited a size of less than 390 nm and demonstrated high drug encapsulation efficiency (98.1 – 99.8%) and loading capacity (326.9 – 332.7 μg/mg). Remarkably, the BCHIALG NPs containing 0.03% boronated chitosan and 0.07% alginate showed superior mucoadhesive capability compared to CHIALG NPs, providing sustained drug release and they showed the most promising results as a transmucosal drug delivery system for hydrophobic drugs like paclitaxel (PTX). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report investigating BCHIALG NPs for cervical drug delivery. The new mucoadhesive paclitaxel formulation could offer an innovative strategy for improving cervical cancer treatment.

Keywords: Boronated chitosan, alginate, paclitaxel, nanoparticles, cervical drug delivery, transmucosal

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is a common malignancy that arises from the abnormal growth of epithelial cells in the uterine cervix [1]. It is a major health issue, with 80% of cases occurring in developing countries [2]. Cervical cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women globally, including those in developing world [3]. Treatment approaches for cervical cancer depend on the stage of the disease and typically involve surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, tumor-targeted therapy, and localized therapy [4]. For early stages of cervical cancer (IA to IIA), surgical intervention followed by local instillation of drug formulations to the cervix is often recommended to prevent recurrence or metastasis. However, the clinical use of certain chemotherapeutic agents, such as paclitaxel (PTX), is limited by side effects, including neutropenia, hypersensitivity, hypotension, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal disturbances, and alopecia, which can result in poor patient compliance and therapeutic failure [5]. Moreover, oral delivery of PTX results in reduced bioavailability majorly due to hepatic metabolism by the cytochrome P450 isoforms CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 and minorly due to its affinity for efflux transporters expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and liver [6]

Various localized formulations of PTX have been developed for cervical cancer treatment. For example, Zong et al. developed biocompatible cisplatin-loaded poly (ethylene oxide)/polylactide composite electrospun nanofibers for local chemotherapy of cervical cancer. These nanofibers were shown to be mucoadhesive and released cisplatin in vivo, resulting in tumor-inhibitory effects [7]. However, the clinical translation of this formulation may be limited due to the inconvenient mode of nanofiber administration and removal.

Xu and co-workers developed a thermosensitive hydrogel composite of PTX-loaded polyethylene glycol methyl ether-polycaprolactone diblock copolymeric micelles and cisplatin-containing PEGPCL-PEG for cervical cancer treatment. The in-situ gel exhibited superior tumor growth inhibitory effects and prolonged animal survival compared to other formulations [8]. However, concerns have been raised about the non-degradability of the PTX copolymeric micellar component of this delivery system.

Mucoadhesive curcumin-loaded cubosomes have also been investigated for topical treatment of cervical cancer, showing potential in vitro cytotoxicity and cervical cancer cellular uptake. However, their use may be limited by their inability to facilitate controlled drug release without surface modification [9]. Therefore, polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) are being investigated as an alternative for potential cervical cancer treatment due to their sustained drug release potential.

The therapeutic efficiency of locally delivered drug formulations for cervical cancer treatment may be compromised by the presence of cervicovaginal fluid that constantly irrigates the cervix and vagina, resulting in poor retention of drug formulations on the cervical mucosa and short-lived therapeutic action. Effective cervical cancer treatment could result in a quick recovery rate for patients, reduced hospital admissions, and decreased global healthcare costs associated with the disease [10]. Therefore, there is a strong need to develop PTX delivery systems that could improve the therapeutic outcomes of cervical cancer patients.

Mucoadhesive, targeted nanomedicines and nanotechnological drug delivery strategies are attractive for cervical cancer treatment due to their bioadhesion, mucosal penetration, controlled drug release and decreased adverse effects [11]. Mucoadhesive NPs interact with mucin glycoproteins via non-covalent and covalent bonds, which help them resist wash-off by biological fluids [12]. Surface modification of polymeric excipients can further enhance the mucoadhesiveness, tumor-targeting potential, and intracellular delivery of drug delivery systems [13].

Chitosan (CHI) and sodium alginate (ALG) are biocompatible, biodegradable, and mucoadhesive biomaterials that have been extensively studied for drug delivery and tissue engineering [7,13]. Polyelectrolyte complexes-based NPs formed by CHI and ALG can overcome the pH-dependent solubility of both biomaterials [14, 15] and protect the encapsulated drugs from degradation [17]. Moreover, CHI could facilitate the opening of the tight junctions, thereby causing effective intracellular drug delivery [17, 18]. However, exposure of the nanoparticulate formulations to biological fluids could limit their mucosal retention, resulting in short-lived therapeutic action.

Various researchers have improved the mucoadhesive property of CHI using thiols [12], acrylate [15], methacrylate [16], catechol [20], and boronate groups [13]. In addition, the mucoadhesiveness of ALG has been improved by thiolation [18] and catechol functionalization [19].

Recently, boronation has been used to improve mucoadhesive properties of drug delivery systems. For instance, Kolawole and co-workers established that the degree of chitosan mucoadhesiveness was improved with an increased extent of chitosan boronation, with highly boronated chitosan exhibiting superior porcine bladder mucoadhesiveness relative to unmodified chitosan, with a urine wash-out50 value of 56 ± 2 mL and 15 ± 4 mL, respectively [13].

To our knowledge, PTX-loaded BCHIALG NPs have never been investigated, for potential cervical cancer therapy. The aim of this work was to formulate and evaluate the particle size distribution, surface charge, encapsulation efficiency/loading capacity, mucoadhesive capability, and in vitro drug release profile of PTX-loaded BCHIALG NPs as a potential drug delivery system for cervical cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

High molecular weight CHI (DA ≥75 %; > 310 kDa), bovine serum albumin, deuterium oxide, 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid (4-CPBA), alginic acid sodium salt (120–190 kDa), Type II porcine gastric mucin, N-3-(dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), and Nhydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. PTX was obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd, China; dialysis membranes (3.5 kDa & 12–14 kDa) were supplied by Solar Bio, China; lactic acid solution was procured from MolyChem, India; and HPLC grade acetonitrile was procured from Loba Chemie Ltd., India. All other chemicals, reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis and characterization of BCHI

BCHI was synthesized and characterised using 1H NMR and FT-IR according to our previously reported method [13]. Synthetic and characterization protocol and results are detailed as supplementary information (S1 and S2).

2.2.2. Formulation of blank CHIALG-based NPs

Three types of BCHI/ALG NPs were prepared using an earlier reported ionic gelation method with modification of the solvent for NPs dissolution[19]. Briefly, BCHI solutions (0.1 % w/v) were prepared by dissolving BCHI powder in 1 % v/v acetic acid and stirring for 12 h at room temperature. Also, ALG was solubilized by stirring the polymer in deionized water for 12 h at room temperature to generate an aqueous solution of ALG (0.1 % w/v). Then, ALG solution was added to the BCHI dispersion at a drop rate of 0.5 mL/min, under magnetic stirring, followed by probe sonication for 30 min using the pulsed mode and amplitude of 40 % to generate BCHIALG NPs containing varying amounts of BCHI and ALG (Table 1). For comparison, three types of CHIALG NPs were also prepared using the same formulation method employed to prepare BCHIALG NPs but the BCHI was replaced with native CHI. The resultant nanoparticulate products were freeze-dried and refrigerated.

Table 1:

Composition of CHIALG NP and BCHIALG NPs

| S/No | Volume of CHI or BCHI (0.1 % w/v) | Volume of ALG (0.1 % w/v) | Composition of NPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 5 mL CHI | 10 mL | 0.03 %CHI + 0.07 %ALG |

| F2 | 5 mL BCHI | 10 mL | 0.03 %BCHI +0.07%ALG |

| F3 | 7.5 mL CHI | 7.5 mL | 0.05 %CHI + 0.0 5%ALG |

| F4 | 7.5 mL BCHI | 7.5 mL | 0.05 % BCHI + 0.05 %ALG |

| F5 | 10 mL CHI | 5 mL | 0.07 % CHI + 0.03 %ALG |

| F6 | 10 mL BCHI | 5 mL | 0.07 % BCHI + 0.03 %ALG |

2.2.3. Determination of particle size and zeta potential

The lyophilized NPs were solubilized in acetate buffer (0.1 M; pH 4); and a probe sonicator was used to disperse the particulate formulation before a 1-to-10 dilution of the NPs were prepared for evaluation of their particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern ZetaSizer (Malvern Instruments Ltd, UK). The NPs were passed through 0.45 μm syringe filters before the measurement was taken in triplicates at 25 °C. The particle size and zeta potential of drug-loaded nanoparticles were also evaluated in order to investigate the influence of drug loading on particle size and surface charge.

2.2.4. Evaluation of NPs morphology

The size and shape of the CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs were confirmed using the transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Philips TECNAI 20, UK). The NPs (2 mg/mL) were coated with uranium acetate (1 %) and dropped onto a copper grid before microscopic analysis. The average diameter of NPs was determined by analyzing acquired TEM images using image analysis software (JMicro Vision V.1.2.7, Switzerland).

2.2.5. Preparation of PTX-loaded NPs

PTX-loaded NPs were prepared by physical adsorption of the drug onto NPs at a NPs to PTX ratio of 1: 0.5. Briefly, lyophilized CHI or BCHI NPs (10 mg) was solubilized in acetate buffer, pH 4 (1 mL, 0.1 M) using Vortex-mixer for 24 h and PTX solution (10 mg/mL, 0.5 mL) was added to the nanoparticulate dispersion and the drug/nanoparticulate mixture was vortexed for 12 h to facilitate drug adsorption. Afterward, the drug/nanoparticulate mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The amount of unloaded drug in the supernatant layer was quantified using HPLC while the sediment (drug-loaded NPs) was stored at 4 °C until further characterisation of the drug carrier.

2.2.6. Evaluation of PTX encapsulation efficiency/loading capacity

The loading capacity (LC) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of PTX in the PTX-loaded NPs were evaluated using a previously reported method with modification of the mobile phase [8]. The mobile phase consisted of HPLC grade-acetonitrile and acetate buffer pH 4 at a volume ratio of 1:1, which flowed through the reverse phase C18 column (ODS Hypersil, 4.6 mm × 250 mm; 5 μm) at a rate of 1 mL/min, with PTX detected at a wavelength of 227 nm. A PTX standard curve was prepared by plotting the peak area values of six different standard PTX solutions against their concentration values (100 μg/mL to 2 μg/mL), and the calculated regression coefficient of the plotted calibration curve was 0.99. The LC and EE values were calculated according to equation 2 and 3, respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

2.2.7. Mucoadhesive potential of the NPs

The mucoadhesive properties of the NPs were evaluated in terms of their mucin interaction, and the study was carried out using a previously reported method with a modification of the technique used to study interaction [21]. Briefly, acetate buffer solution (ABS, 0.1 M, pH 4) was prepared by dissolving 0.93 g of sodium acetate and 2.2 mL of acetic acid in 400 mL deionized water and the mixture was stirred for 1 h, the pH of the buffer was adjusted as desired and volume of buffer solution was made up to 500 mL using deionized water. Afterward, a predetermined amount of mucin powder was dissolved in ABS (pH 4) and stirred for 1 h to generate mucin dispersion (12 % w/v). Then, the mucin dispersion was diluted with ABS (pH 4) to generate 10 % w/v, 8 % w/v, 6 % w/v, 5 % w/v and 4 % w/v mucin dispersions. In addition, NPs dispersions (0.02 % w/v) were prepared by dissolving predetermined amounts of NPs in ABS (pH 4) for 12 h at room temperature.

The viscosity component due to bioadhesion or rheological synergism (Δη) was calculated as follows:

| (4) |

where ηmix is the viscosity of the NP-mucin mixture (cP); ηNP is the viscosity of the NPs having the same concentration as in the mixture (cP); and ηmuc is the viscosity of mucin dispersion having the same concentration as in the mixture (cP) [21].

2.2.8. In vitro drug release studies

There are no remarkable differences between vaginal and cervical fluid. Thus, simulant vaginal fluid (SVF) was used for the experiment. It was prepared according to an earlier reported method [22]. Briefly, sodium chloride (3.51 g), potassium hydroxide (1.40 g), Calcium hydroxide (0.22 g), bovine serum albumin (0.018 g), lactic acid (2.00 g), acetic acid (1.00 g), glycerol (0.16 g), urea (0.40 g), and glucose (5.0 g) were dissolved in 800 mL deionized water under magnetic stirring for 1 h. Then, the simulant vaginal fluid was adjusted as necessary (pH 4.5) and made up to 1 L using deionized water.

The release pattern of PTX from the nanoparticulate formulation was studied using the dialysis method as previously reported [19], with freshly prepared SVF (pH 4.5) serving as the release medium. Briefly, PTX-loaded NPs (10 mg) were dispersed into simulant vaginal fluid (1 mL) and the nanoparticulate dispersion was secured in a pre-hydrated dialysis bag (MWCO 3.5 kDa) and the bag was placed in a Duran borosilicate glass bottle (100 mL) containing 20 mL of simulant vaginal fluid. The bottle was maintained in a shaking water bath (65 rpm) maintained at 37 ◦C. At predetermined time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h), an aliquot (1 mL) was analyzed for drug content using a previously reported HPLC method with modification [8], and a detailed report on the accuracy and precision of the new HPLC method has been supplied as supplementary information (Table S1).

The PTX release kinetics was evaluated by fitting the drug release data into different kinetic models (the zero-order, first-order, Higuchi and the Korsmeyer-Peppas) to determine the release pattern of the NPs.

2.2.9. Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicates and data was presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-Way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, with p < 0.05 indicating significant statistical differences between datasets.

3. Results and Discussion

Typically, early and advanced stages of cervical cancer require local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to the cervix to prevent cervical cancer recurrences and progression. Moreover, this route of drug administration facilitates improved exposure of cervical tumors to therapeutic agents [8]. Cervicovaginal fluid constantly irrigates the female reproductive system for fertility maintenance as well as protection from particulate and microbial invasion, and mucoadhesive drug delivery systems could resist the wash-out of drug formulation from the cervix. In addition, mucoadhesive nanoparticulate drug delivery systems facilitate drug accumulation into leaky tumor vasculature, and their surface modification with mucoadhesive and malignant tissue targeting ligands could promote site-specific drug delivery [23].

Urine wash-out50 profile of mucoadhesive polymers is a biological term associated with intravesical drug delivery to the bladder, and it depicts the volume of simulant urine that will wash out 50 % of the fluorescent polymeric dispersions instilled on animal bladder mucosal surfaces [24]. Kolawole et al. (2019) reported that BCHI with greatest degree of boronation (16.5 %) exhibited superior urothelial mucoadhesiveness relative to unmodified CHI (urine wash-out50 value of 56 ±2 mL versus 15 ±4 mL) [13].

CHI and ALG have been used to formulate various controlled-release dosage forms because they are readily available, biocompatible, biodegradable and mucoadhesive [25]. Also, they could generate polyelectrolyte-based NPs via ionic gelation technique [25] but the properties of BCHIALG NPs have never been investigated for potential drug delivery application. We hypothesize that BCHIALG NPs may exhibit superior physicochemical, mucoadhesiveness and sustained drug release profiles relative to CHIALG NPs.

3.1. Synthesis and Characterisation of BCHI

BCHI was synthesized using similar CHI to 4-carboxyphenylboronic acid following the method that was previously reported [13]. The synthesis reaction is shown in Figure S1. BCHI was successfully synthesized as there were changes in the physical state of the polymer from a light brown, free-flowing powder to an off-whitish amorphous solid. The product yield was 11.0 ± 1.1 %, which was less than the product yield earlier reported (33 %) [13]. The synthesized BCHI exhibited a comparable degree of boronation with the previously synthesized BCHI [13] (11.4 % ± 0.30 % versus 16.5 %).

The 1H NMR and FT-IR spectra of parent CHI and BCHI are presented in Figures S2 and S3 (Supplementary information). 1H NMR data confirmed that boronate groups were successfully conjugated to chitosan amine groups (Figure S2). The obtained FT-IR data (Figure S3) are in good agreement with the FT-IR spectra of BCHI reported in earlier studies by Zhang et al., (2016) [26] and Kolawole et al., (2019) [13], where the respective -CN stretch was evident at 1333.34 cm−1 and 1308 cm−1 while C-C stretch of benzene appeared at 1546.34 cm−1 and 1520 cm−1, respectively. Also, the absorption peak confirming boronation of CHI that appeared at 1647 cm−1 in the current study was detected at 1643.37 cm−1 and 1636 cm−1, respectively, for similar polymer synthesized by Zhang et al., (2016) [26] and Kolawole et al (2019) [13]. Overall, both 1H NMR and FT-IR data confirm CHI modification.

3.2. Properties of CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs

Various techniques could be used to formulate CHIALG NPs, namely, water-in-oil emulsification [27]; electrospraying [28]; extrusion of polymer dispersions [29]; self-assembly of polysaccharides [30]; microfluidic method [28, 29]; sonication [31], [32]; electrostatic gelation [32–34], and ionic gelation [35, 36]. In the current study, a combination of ionic gelation and sonication techniques was used to formulate polyelectrolyte-based NPs due to their potential to generate uniform particle size distribution within the nanometer range [19]. This is the first report where PTX-loaded BCHIALG NPs were investigated for potential cervical drug delivery. Nevertheless, CHIALG-based drug formulations have been studied for possible delivery to various transmucosal sites such as the ocular, nasal, buccal, intravesical, vaginal and rectal routes [25].

Unlike CHIALG NPs that could interact with mucin glycoproteins via hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, covalent complexes could be generated between BCHIALG NPs and mucin glycoproteins [13], which may facilitate improved retention of the new dosage form on cervical mucosal surfaces for a prolonged period.

The particle size, polydispersity index and the surface charge of the blank and PTX-loaded NPs were investigated by dynamic light scattering technique and the findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Particle size distribution and zeta potential values of blank and PTX-loaded CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs (pH 4), conducted at 25 °C; data presented as mean ± SD (n = 3)

| S/N | Formulation | Size ± SD (nm) | PDI ± SD | ZP ± SD (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.03 % CHI + 0.07 % ALG NPs | 238.1 ± 2.2 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | −35.6 ± 0.8 |

| PTX-F1 | PTX-0.03% CHI + 0.07% ALG NPs | 266.3±6.4 | 0.32±0.02 | −25.9±0.6 |

| F2 | 0.03 % BCHI + 0.07 % ALG NPs | 244.0 ± 1.5 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | −37.0 ± 0.3 |

| PTX-F2 | PTX-0.03% BCHI + 0.07% ALG NPs | 284.3±14.3 | 0.22±0.05 | −25.7±1.2 |

| F3 | 0.05 % CHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs | 263.4 ± 8.8 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | −2.4 ± 0.4 |

| PTX-F3 | PTX-0.05% CHI + 0.05% ALG NPs | 312.2±5.4 | 0.34±0.03 | 20.2±2.0 |

| F4 | 0.05 % BCHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs | 307.4 ± 8.4 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | −32.4 ± 0.8 |

| PTX-F4 | PTX- 0.05% BCHI + 0.05% ALG NPs | 387.8±8.11 | 0.26±0.09 | −23.9±0.70 |

| F5 | 0.07 % CHI + 0.03 % ALG NPs | 242.2 ± 0.9 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 31.8 ± 0.6 |

| PTX-F5 | PTX-0.07% CHI + 0.03% ALG NPs | 289.6±9.6 | 0.35±0.04 | 35.0±2.4 |

| F6 | 0.07 % BCHI + 0.03 % ALG NPs | 280.8 ± 4.0 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 33.0 ± 0.4 |

| PTX-F6 | PTX-0.07% BCHI + 0.03% ALG NPs | 296.4±11.2 | 0.19±0.06 | 38.5±2.0 |

KEY: CHI: chitosan; BCHI: boronated chitosan; ALG: alginate; CHIALG NPs: chitosan-alginate nanoparticles; BCHIALG NPs: boronated chitosan-alginate nanoparticles; F1: 0.03%CHI+0.07%ALG; F2: 0.03%BCHI+0.07%ALG; F3: 0.05%CHI+0.05%ALG; F4: 0.05%BCHI+0.05%ALG; F5: 0.07%CHI+0.03%ALG; F6: 0.07%BCHI+0.03%ALG; PTX-F1 to F6 are paclitaxel loaded nanoparticles

The freeze-dried nanoparticulate samples were off-whitish to greyish depending on the amount of CHI and ALG used for the formulation. The recovery rate of the NPs after freeze-drying of the nanoparticulate dispersion ranged from 90 % to 100 %. All the studied NPs had hydrodynamic diameters in the nanometer range (238–307 nm) with desirable particle size distribution (Table 1, Figure S4), which is suitable for cervical drug delivery. In addition, the polydispersity indexes of the NPs were low (0.11–0.29), which suggested that their particle size distributions were uniform. The average diameter of BCHIALG NPs (244–307 nm) was greater than that of the unmodified CHIALG NPs (238–263 nm). This finding is in good agreement with earlier studies where surface modification of NPs increased their particle diameter [18, 20, 23, 37].

Overall, there was an increase in the particle size, polydispersity index and positive surface charge of the CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs after drug loading (Table 2). The zeta potential values of all the studied paclitaxel loaded nanoparticles, which denotes their colloidal stability were satisfactory after drug loading (−25.9 mV to 38.5 mV). Similarly, their drug-loaded nanoparticle size range was less than 400 nm, which is suitable for localized drug delivery to the cervix This finding is in good agreement with previous studies, where docetaxel was loaded into cationic chitosan-coated polycaprolactone NPs resulted in an increase in size of NPs from 220 nm to 270 nm [39].

An inversion trend was observed with the zeta potential values of the studied NPs, with the zeta potential values of the NPs changing from negative to positive values (−35.6 mV versus 33 mV) as the CHI or BCHI content of the NPs was increased from 0.03 % to 0.07 %. This finding might be due to the cationic nature of CHI and BCHI which facilitate the surface charge changes. In addition, there were remarkable changes in the zeta potential of NPs containing an equal amount of CHI and ALG after boronate conjugation (F4 versus F3). On the other hand, boronation of CHI did not induce significant changes in the zeta potential values of F1 versus F2 (greater ALG content) as well as F5 versus F6 (greater CHI content). This finding may be because CHI or BCHI to ALG ratio in the NPs influences their surface charge properties.

The zeta potential values of nanoparticulate formulations dictate their colloidal stability as drug delivery systems with zeta potential values less than −30 mV or higher than +30 mV are highly stable [40]. CHIALG NPs prepared using an equal amount of CHI and ALG (0.05% CHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs) exhibited a zeta potential of −2.4 mV, indicating poor colloidal stability of the formulation while the other formulations of CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs displayed excellent colloidal stability (with the zeta potential values of - 35.6 to −37 mV in the formulations with higher content of ALG, and the zeta potential values of +31.8 to +33 mV in the formulations with higher content of CHI). Interestingly, BCHIALG NPs formulated using equal amounts of BCHI and ALG exhibited superior colloidal stability relative to those prepared using unmodified CHI (−32.4 mV versus −2.4 mV), suggesting that boronation is beneficial to improve the colloidal stability of CHIALG NPs. This finding is in good agreement with studies by Sahatsapan et al., 2021 where dual functionalized NPs with greater maleimide-CHI content exhibited greater zeta potential values than those with higher catechol-ALG content (38–39 mV versus 14 mV) [19].

It was observed that the freeze-dried NPs exhibited some form of aggregation, so sonication may be required to redisperse formulation prior to administration. This finding is in good agreement with the report on freeze-dried dual-functionalized maleimide-CHI/ALG-catechol NPs studied by Sahatsapan et al., (2021) that appeared as aggregates after lyophilization. Thus, cryoprotectants such as mannitol, sorbitol, or maltose may be added to the NPs prior to freeze-drying to improve their dispersibility [19].

3.3. Morphological properties of the NPs

To elucidate the morphology of the NPs, transmission electron microphotographs of the CHIALG NPs (0.03 % CHI + 0.07 %) and BCHIALG NPs (0.03 % BCHI + 0.07 % ALG) formulations were taken and the obtained photographs are presented in Figure 1. Almost spherical NPs were obtained with particle diameters of 175 and 197 nm, respectively. TEM analysis of the NPs containing greater amounts of ALG revealed a smaller particle size (175–197 nm) than that obtained using Zetasizer (238–244 nm). The smaller NPs size obtained with TEM analysis could be due to the investigation of the NPs in their dehydrated state [19].

Figure 1:

TEM microphotographs of CHIALG NPs (0.03 % CHI + 0.07 % ALG) (left image) and BCHIALG NPs (0.03 % BCHI + 0.07 % ALG) (right image), with a scale bar of 50 nm and 100 nm, respectively.

3.4. PTX encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity of drug-loaded NPs

The drug loading efficiency and loading capacity of the PTX-loaded CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs are determined to evaluate the drug-carrying ability of the NPs. The results revealed a high drug loading efficiency and loading capacity of NPs as presented in Table 3.

Table 3:

% EE and LC of PTX -loaded NPs; data presented as mean ± SD (n = 3)

| S/N | Formulation | % EE | LC (μg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTX-F1 | 0.03 % CHI + 0.07 % ALG NPs | 93.9±0.5 | 312.8±1.6 |

| PTX-F2 | 0.03 % BCHI + 0.07 % ALG NPs | 99.7±0.1 | 332.3±0.4 |

| PTX-F3 | 0.05 % CHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs | 93.7±0.3 | 312.3±1.2 |

| PTX-F4 | 0.05 % BCHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs | 99.8±0.1 | 332.7±0.2 |

| PTX-F5 | 0.07 % CHI + 0.03 % ALG NPs | 98.6±0.1 | 328.8±0.4 |

| PTX-F6 | 0.07 % BCHI + 0.03 % ALG NPs | 98.1±0.1 | 326.9±0.3 |

KEY: CHI: chitosan; BCHI: boronated chitosan; ALG: alginate; CHIALG NPs: chitosan-alginate nanoparticles; BCHIALG NPs: boronated chitosan-alginate nanoparticles; PTX-F1 to F6 are paclitaxel loaded nanoparticles

Chemotherapeutic drug delivery systems with high drug encapsulation and loading capacity could facilitate reduced dosing intervals as daily drug dosage could be incorporated into the drug carrier such that the drug formulation is administered once daily. All the studied nanoparticulate formulations exhibited excellent PTX encapsulation efficiency (EE) and loading capacity (LC) at the studied ratio of NPs to the drug (1: 0.5), with EE and LC of 98.1 – 99.8 % and 326.9 – 332.7 μg/mg, respectively. This finding is in good agreement with earlier findings where doxorubicin loaded into dual-functionalized NPs at NPs to drug ratio of 1:0.5 exhibited the greatest doxorubicin encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity of 74.7 ± 0.3 % and 249.0 ± 0.9 μg/mg, respectively [19]. In addition, boronation of CHI improved the PTX encapsulation and loading capacity of the nanoparticulate formulations as the PTX encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity of the BCHIALG NPs were found to be higher than that of the unmodified CHIALG NPs. This may be due to improved interaction between hydrophobic PTX and boronate groups that constitute the polymeric core, facilitating improved drug encapsulation and loading.

3.5. Mucoadhesive profile of CHIALG and BCHIALG NPs

The mucoadhesiveness of the nanoparticulate formulations was evaluated in terms of their rheological synergism, which is the viscosity associated with bioadhesion imparted on the formulations due to the interaction between the NPs formulation and mucin. The mucoadhesive data are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Mucoadhesive properties of CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs, evaluated in terms of their viscosity component due to bioadhesion (rheological synergism), with samples maintained at 37 °C for 2 h prior to viscosity determination. Data are expressed as mean values ± SD, n = 3; * depict significance in the statistical differences between datasets.

The studied NPs exhibited mucoadhesiveness that was dependent on the concentration of mucin used for the mucoadhesive experiment. They displayed low rheological synergistic values at mucin concentrations from 4 % to 6 %. As mucin concentration was increased from 8 % to 12 %, the viscosity component due to bioadhesion of the formulations increased remarkably. There were significant statistical differences between the mucoadhesiveness of 0.03%BCHI + 0.07 %ALG NPs and the other studied nanoparticulate formulations at high mucin concentrations (≥ 10 % w/v) (p < 0.05). In addition, the mucoadhesive properties of BCHIALG NPs were generally greater than that of the unmodified CHI/ALG NPs at mucin concentration of 10–12 % w/v, which may be due to the covalent linkage between BCHI-based formulations and mucin.

The polymeric constituents of the NPs had a greater influence on their mucoadhesiveness than their degree of positive surface charge as 0.03%BCHI + 0.07 %ALG NPs containing a greater amount of ALG and zeta potential of −37.0±0.3 mV was more mucoadhesive than 0.07%BCHI + 0.03 %ALG NPs with zeta potential of 33.0±0.4 mV. Nevertheless, the 0.05%CHI + 0.05 %ALG NPs with the least positive or negative charge, exhibited the lowest extent of mucoadhesiveness, probably due to their surface charge that was comparable to a neutral charge, resulting in poor interaction between the NPs with mucin.

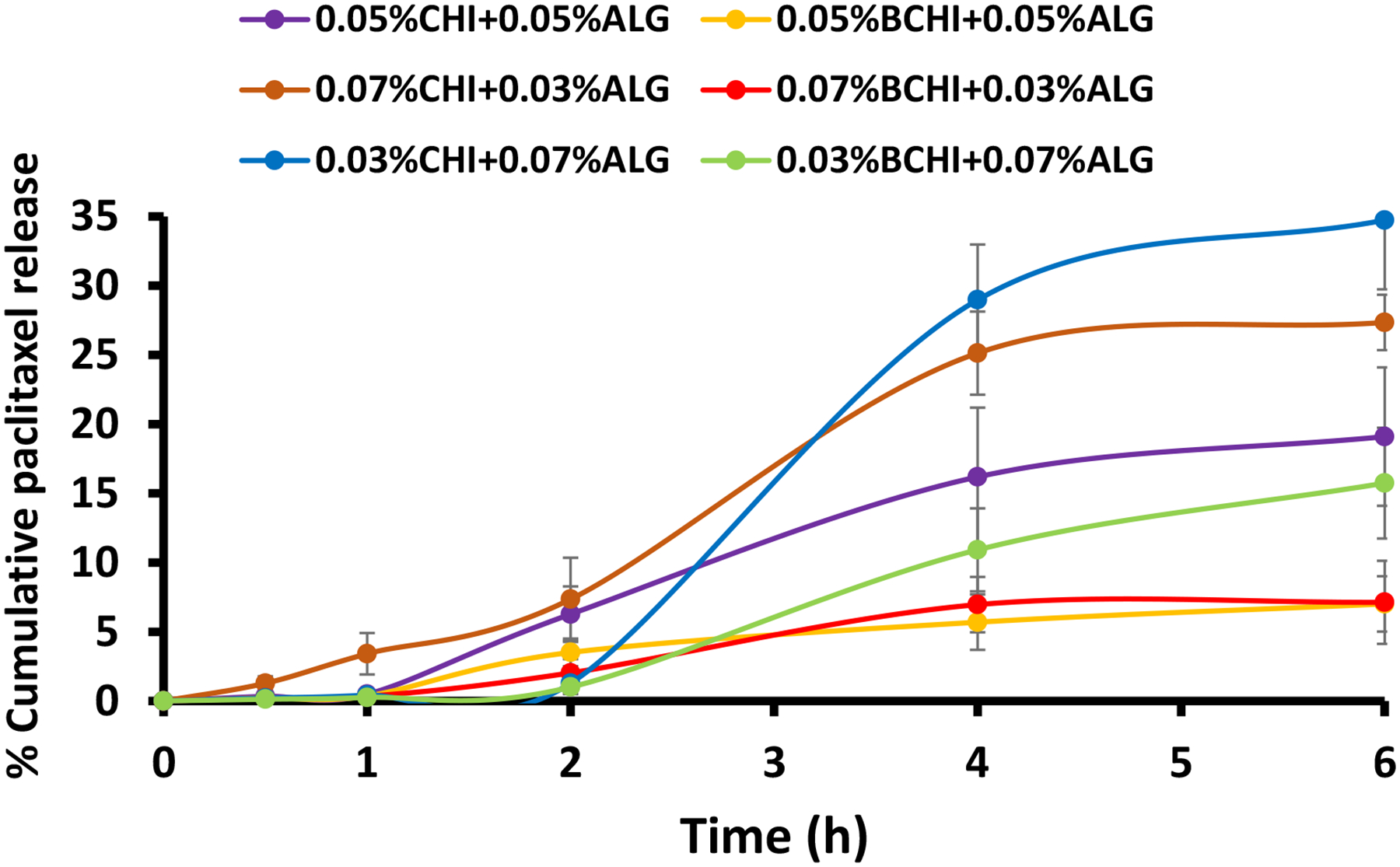

3.6. Drug release profile of drug-loaded NPs

Drug release is one of the important factors determining the efficacy of a drug delivery system. Mucoadhesive NPs should be able to provide sustained release of a drug for a prolonged period at the site of action or site of absorption. The drug release pattern of drug-loaded CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs were studied and the findings are presented in Figure 3. The amount of PTX released from 0.03 %CHI+0.07 %ALG NPs, 0.03 %BCHI+0.07 %ALG NPs, 0.05 %CHI+0.05 %ALG NPs, 0.05 %BCHI+0.05 %ALG NPs, 0.07 %CHI+0.03 %ALG NPs, 0.07 %BCHI+0.03 %ALG NPs, after 6 h was 34.7 %, 15.7 %, 19.1 %, 7.0 %, 27.4 %, and 7.1 %, respectively, suggesting that boronate groups conjugation with CHI prior to NPs preparation facilitated controlled PTX release. In addition, the CHIALG NPs with a greater amount of ALG or CHI facilitated the release of a greater amount of PTX (34.7 % versus 27.4 %) than those formulated using an equal amount of CHI and ALG (19.2 %). Nevertheless, all the formulations may be suitable for transmucosal drug delivery depending on the type of drug release profile desired.

Figure 3:

In vitro release profiles of PTX from CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs studied at 37 °C for 6 h. Data are depicted as mean±SD

(n=3).

The PTX release kinetics from CHIALG NPs and BCHIALG NPs fitted well with the zero-order and Korsmeyer-Peppas model, suggesting that PTX could be released from the nanoparticulate formulations at a constant rate. In addition, PTX release from the drug carrier was facilitated through swelling and dissolution of the polymeric drug carrier as well as diffusion and dissolution of the drug. The Korsmeyer-Peppas associated diffusional exponent (n) was calculated to ascertain the specific drug release pattern of the formulations. Most of the studied formulations (0.03%BCHI+0.07%ALG NPs, 0.05%CHI + 0.05%ALG NPs, 0.07%CHI + 0.03%ALG NPs and 0.07%BCHI + 0.03%ALG NPs) exhibited the non-Fickian Supercase II drug release profile because their calculated n values were greater than 1. Also, 0.03%CHI+0.07%ALG NPs and 0.05%BCHI + 0.05%ALG NPs displayed Pseudo-Fickian diffusion (n = 0.2854) and non-Fickian anomalous case (n = 0.6419) drug release pattern, respectively. These results suggested that controlled drug release from CHIALG nanoparticulate dosage forms may result from both solvent diffusion and relaxation of polymer chain [41]. This finding is in good agreement with lovastatin-loaded CHIALG NPs prepared using the ionic gelation method that fitted well with the Korsmeyer-Peppas model [42]. This PTX release profile may be particularly beneficial for cervical cancer patients requiring controlled drug release to reduce drug dosing frequency and duration of treatment.

The biocompatibility of the nanoparticulate formulations was not studied because the biocompatibility of CHI and ALG has been established and the Food and Drug Administration, USA has approved these biomaterials as polymeric excipients for the formulation of drug delivery systems [25]. Moreover, the safety of phenyl boronate groups conjugated to CHI has been established using in vitro and in vivo models [43]–[45].

4. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report where PTX-loaded BCHIALG NPs have been successfully developed. The constituent of the nanoparticulate formulations influenced their particle size, polydispersity index, surface charge, mucoadhesiveness and drug release profile. Boronation was able to improve mucoadhesive capability of the NPs. In addition, BCHIALG NPs were able to sustain the release of PTX for up than 6 h. The developed BCHIALG NPs may be a promising PTX delivery system for the localized treatment of cervical cancer. This work has generated a valuable addition to the class of advanced mucoadhesive nanoparticles for transmucosal drug delivery. However, further ex vivo and in vivo studies using reliable cervical mucosal models are required to facilitate the translation of the optimized formulations from the research laboratory to the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

In vitro PTX release kinetic studies of unmodified CHI and BCHI-based NPs

| Sample | Zero-order | First order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer-Peppas | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | k1 | r2 | k2 | r2 | k3 | r2 | n | k4 | |

| PTX-F1 | 0.9038 | 4.1118 | 0.7911 | 0.8247 | 0.7467 | 15.864 | 0.876 | 0.2854 | 49.34 |

| PTX-F2 | 0.9392 | 1.7991 | 0.8476 | 0.6884 | 0.9034 | 9.6668 | 0.8959 | 2.6254 | 20.99 |

| PTX-F3 | 0.9572 | 1.0724 | 0.8586 | 0.2784 | 0.8586 | 8.9374 | 0.9857 | 1.0579 | 25.074 |

| PTX-F4 | 0.9436 | 0.0924 | 0.9495 | 0.1732 | 0.889 | 3.2544 | 0.9915 | 0.6419 | 8.4438 |

| PTX-F5 | 0.9438 | 0.8154 | 0.8583 | 0.5329 | 0.8598 | 12.807 | 0.9255 | 1.2545 | 34.212 |

| PTX-F6 | 0.9194 | 0.3763 | 0.7639 | 0.3141 | 0.8312 | 3.4751 | 0.9349 | 1.2183 | 9.7585 |

Key: PTX-F1 (paclitaxel loaded 0.03 %CHI + 0.07%ALG NPs); PTX-F2 ((paclitaxel loaded 0.03 %BCHI + 0.07%ALG NPs); PTX-F3 ((paclitaxel loaded 0.05 %CHI + 0.05 % ALG NPs); PTX-F4 ((paclitaxel loaded 0.05%BCHI + 0.05%ALG NPs); PTX-F5 ((paclitaxel loaded 0.07%CHI +0.03%ALG NPs); PTX-F6 ((paclitaxel loaded 0.07 %BCHI + 0.03%ALG NPs)

Highlights of the manuscript titled “Formulation and evaluation of boronated chitosan/alginate nanoparticles for potential cervical drug delivery”.

Boronated chitosan/alginate nanoparticles have been developed for drug delivery

Boronated nanoparticles exhibited excellent paclitaxel encapsulation efficiency

Boronated nanoparticles displayed satisfactory mucoadhesiveness.

Boronated nanoparticles facilitated controlled paclitaxel release.

The new boronated nanoparticles may be useful for various transmucosal applications

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010134. The authors are grateful to Mr. P.D. Ojobo of the Central Research Laboratory, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria for providing HPLC support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

CrediT author statement

Conceptualization: OK, AO; Methodology: OK, PP; Investigation: OK, WI, AI, PP; data curation/visualization: OK, PP; Software/validation: OK, PP, MA; Resources/Funding acquisition: OK, AO, WI, BS, PP, MA; Visualization: OK, PP; Writing- original draft preparation: OK; Writing – review and editing: PP, MA, BS, AO; Project administration/supervision: OK, AO.

Conflicts of Interests

There are no conflicts of interest to be declared by the authors

References

- [1].Koh W-J, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, Bradley K, Campos SM, et al. , Cervical Cancer Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 17 (2019) 64–84, 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].ICO/IARC/HPV, Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report, 2019. [Online]. Available: hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf. Accessed Mar. 10, 2022)

- [3].Cheikh A, El Majjaoui S, Ismail N, Cheikh Z, Bouajaj J, Neijjari C, Evaluation of the cost of cervical cancer at the National Institute of Oncology, Rabat, Pan Afr Med Journ, 23, (2016) 209–2013, 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.209.7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L, Cervical Cancer, Lancet, 393 (2019): 169–182. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Louage B, De Wever O, Hennik WE, De Geest BG. Developments and future clinical outlook of taxane nanomedicines, J. Control. Release 253 (2017) 137–152. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Taniguchi R, Kumai T, Matsumoto N, Watanabe M, Kamio K, Suzuki S. Utilization of Human Liver Microsomes to Explain Individual Differences in Paclitaxel Metabolism by CYP2C8 and CYP3A4, J Pharmacol Sci 97 (2005) 83–90, 10.1254/jphs.fp0040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zong S, Wang X, Yang Y, Wu W, Li H, Ma Y et al. , The use of cisplatin-loaded mucoadhesive nanofibers for local chemotherapy of cervical cancers in mice, Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 93 (2015) 127–135. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu S, Du X, Feng G, Zhang Y, Li J, Lin B et al. Efficient inhibition of cervical cancer by dual drugs loaded in biodegradable thermosensitive hydrogel composites, Oncotarget. 9 (2018): 282–292. 10.18632/Foncotarget.22965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Victorelli FD, Mami LS, Biffi S, Bortot B, Buzza HH, Lutz-Bueno V et al. Potential of curcumin-loaded cubosomes for topical treatment of cervical cancer, J Coolloid Interface Sci 620 (2022) 419–430. 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McConville C, The use of localized vaginal drug delivery as part of a neoadjuvant chemotherapy strategy in the treatment of cervical cancer, Gynecol Obs. Res Open J, 2 (2015) 26–28. 10.17140/GOROJ-2-106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang X, Liu S, Guan Y, Ding J, Ma C, Xie Z, Vaginal drug delivery approaches for localised management of cervical cancer, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 174 (2021) 114–126. 10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bernkop-Schnürch A, Hornof M, Zoidl T. Thiolated polymers—thiomers: synthesis and in vitro evaluation of chitosan–2-iminothiolane conjugates, Int. J. Pharm 260 (2003) 229–237. 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kolawole OM, Lau WM, and Khutoryanskiy VV, Synthesis and Evaluation of Boronated Chitosan as a Mucoadhesive Polymer for Intravesical Drug Delivery, J. Pharm. Sci, 108 (2019) 3046–3053, doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Boyd P, Major I, Wang W, McConville C, Development of disulfiram loaded vaginal rings for the localised treatment of cervical cancer, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 88 (2014), 945–953. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shitrit Y, Bianco-Peled H, Acrylated chitosan for mucoadhesive drug delivery systems, Int. J. Pharm 517 (2017) 247–255. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kolawole OM, Lau WM, Khutoryanskiy VV, Methacrylated chitosan as a polymer with enhanced mucoadhesive properties for transmucosal drug delivery, Int. J. Pharm, 550 (2018) 123–129. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Loquercio A, Castell-Perez E, Gomes C, Moreira RG, Preparation of chitosan-alginate nanoparticles for trans-cinnamaldehyde entrapment, J Food Sci, 80 (2015) N2305–N2315. 10.1111/1750-3841.12997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jindal AB, Wasnik MN, Nair HA, Synthesis of thiolated alginate and evaluation of mucoadhesiveness, cytotoxicity and release retardant properties, Indian J. Pharm. Sci, 72 (2010) 766–774, doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.84590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sahatsapan N, Rojanarata T, Ngawhirunpat T, Opanasopit P, Patrojanasophon P, Doxorubicin-loaded chitosan-alginate nanoparticles with dual mucoadhesive functionalities for intravesical chemotherapy, J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol, 63 (2021) 102481–10248, doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sahatsapan N, Rojanarata T, Ngawhirunpat T, Opanasopit P, Patrojanasophon P, Catechol-functionalized succinyl chitosan for novel mucoadhesive drug delivery, Key Eng Mater, 819 (2019) 21–26. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.819.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Silva MM, Calado R, Marto J, Bettencourt A, Almeida AJ, Gonçalves LMD, Chitosan nanoparticles as a mucoadhesive drug delivery system for ocular administration, Mar. Drugs, 15 (2017) 1–16, doi: 10.3390/md15120370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Owen DH, Katz DF, A Vaginal fluid Simulant, Contraception 59 (1999) 91–95. 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang J, Wu W, Zhang Y, Wang X, Qian H, Liu B et al. The combined effects of size and surface chemistry on the accumulation of boronic acid-rich protein nanoparticles in tumors, Biomaterials 35 (2014) 866–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mun EA, Williams AC, Khutoryanskiy VV, Adhesion of thiolated silica nanoparticles to urinary bladder mucosa: Effects of PEGylation, thiol content and particle size, Int. J. Pharm 512 (2016) 32–38. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Niculescu A-G, Grumezescu AM. Applications of chitosan/alginate-based nanoparticles - An up-to-date review, Nanomater 12 (2022), 186. 10.3390/Fnano12020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang D, Yu G, Long Z, Yang G, Wang B, Controllable layer-by-layer assembly of PVA and phenylboronic acid-derivatized chitosan, Carbohydr. Polym 140 (2016) 228–232. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Abreu FO, Forte MM, Kist TB, Lonaiser LP, Effect of the preparation method on the drug loading of alginate-chitosan microspheres, Express Polym, 4 (2010) 456–464. https://www.ipen.br/biblioteca/cd/cbpol/2009/PDF/403.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kianersi S, Solouk A, Saber-Samandari S, Keshel SH, Pasbaksh P, Alginate nanoparticles as ocular drug delivery carriers, J Drug Deliv Sci Tech, 66 (2021), 102889. 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mirtic J, Rijavec T, Zupancic S, Zivonar A, Lapanje A, Kristl J, Development of probiotic loaded microcapsules for local delivery: physical properties, cell release and growth, Eur J Pharm Sci, 121 (2018) 178–187. 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Giri TK, Nanoarchitectured polysaccharide-based drug carriers for ocular therapeutics, in Nanoarchitectonics for smart delivery and drug targeting, Holban AM GA, Ed. Oxford, Uk: William Andrew, 2016, pp. 119–141. 10.1016/C2015-0-06101-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yu L, Sun Q, Hui Y, Seth A, Petrovsky N, Zhao C-X, Microfluidic formation of core-shell alginate microparticles for protein encapsulation and controlled release, J Colloid Interface Sci, 539 (2019) 497–503. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gao Y, Ma Q, Cao J, Wang Y, Yang X, Xu Q et al. , Recent advances in microfluidic-aided chitosan-based multifunctional materials for biomedical applications, Int J Pharm, 600 (2021) 120465. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maity S, Mukhopadyay P, Kundu PP, Chakraborti A-S, Alginate coated chitosan core-shell nanoparticles for efficient oral delivery of naringenin in diabetic animals - an in vitro and in vivo approach, Carbohydr Polym,170 (2017) 124–132. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hashemian M, Anissian D, Ghasemi-Kasman M, Akbari A, Khalili-Fomeshi M, Ghasemi S et al. , Curcumin-loaded chitosan-alginate-STPP nanoparticles ameliorate memory deficits and reduce glial activation in pentylenetetrazol-induced kindling model of epilepsy, Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 79 (2017) 462–471. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Aluani D, Tzankova V, Kondeva-Burdina M, Yordanov Y, Nikolova E, Odzhakov F et al. , Evaluation of biocompatibility and antioxidant efficiency of chitosan-alginate nanoparticles loaded with quercetin, Int J Biol Macromol, 103 (2017): 771–782. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gierszewska M, Ostrowska-Czubenko J, Chrzanowska E, pH-responsive chitosan/alginate polyelectrolyte complex membranes reinforced by tripolyphosphate, Eur Polym 101 (2018): 282–290. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2018.02.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tzankova V, Aluani D, Kondeva-Burdina M, Yordanov Y, Odzhakov F, Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activity of quercetinn loaded chitosna/alginate nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo in a model of paracetamol-induced toxicity,” Biomed Pharmacother, 92 (2017) 569–579. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang J, Zhang Z, Wang X, Wu W, and Jiang X, Size- and pathotropism-driven targeting and washout-resistant effects of boronic acid-rich protein nanoparticles for liver cancer regression, J. Control. Release 168 (2013) 1–9. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Varan C, Bilensoy E, Cationic PEGylated polycaprolactone nanoparticles carrying post-operation docetaxel for glioma treatment, Belistein J Nanotechnol, 8 (2017), 1446–1456. 10.3762/bjnano.8.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moore TL, Rodriguez-Lorenzo L, Hirsch V, Balog S, Urban D, Jud C et al. , Nanoparticle colloidal stability in cell culture media and impact on cellular interactions, Chem Soc Rev, 44 (2015) 6287–6305. 10.1039/C4CS00487F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Baggi RB, Kilaru N, Calculation of predominant drug release mechanism using Peppas-Sahlin model, Part I (substitution method): A linear regression approach, Asian J Pharm Tech ( 6(4) 2016, 223–230. 10.5958/2231-5713.2016.00033.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Thai H, Nguyen CT, Thach LT, Tran MT, Mai HD, Nguyen TT et al. , Characterization of chitosan/alginate/lovastatin nanoparticles and investigation of their toxic effects in vitro and in vivo, Sci. Rep 10 (2020) 1–15, 10.1038/s41598-020-57666-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cheng C, Zhang X, Wang Y, Sun L, and Li C, Phenylboronic acid-containing block copolymers: Synthesis, self-assembly, and application for intracellular delivery of proteins, New J. Chem( 36 (6) 2012,1413–1421, 10.1039/c2nj20997g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Liu S, Chang CN, Verma MS, Hileeto D, Muntz A, Tahl U et al. , Phenylboronic acid modified mucoadhesive nanoparticle drug carriers facilitate weekly treatment of experimentallyinduced dry eye syndrome, Nano Res., 8 (2015): 621–635. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12274-014-0547-3. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Deshayes S, Cabral H, Ishii T, Miura Y, Kobayashi S, Yamashita T et al. , Phenylboronic acid-installed polymeric micelles for targeting sialylated epitopes in solid tumors, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 135 (41) 2013, 15501–15507 10.1021/ja406406h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.