Should the criterion for death require permanent or irreversible cessation of function? “Permanent” means loss of function that cannot resume spontaneously and will not be restored through intervention. “Irreversible” means loss of function that cannot resume spontaneously and cannot be restored through intervention. “Cessation of function” can refer to the circulatory-respiratory standard or the neurologic standard. In this article, we explain why the criterion need only require permanent cessation of function.

When we declare death, in many circumstances, it is essential to know the point of irreversibility has been reached. We do not want to declare somebody dead when we could bring them back to life where appropriate to do so.

But there are cases where it would be inappropriate to try to bring people back to life. In those circumstances, it is being permanently lifeless that is more important than knowing that the person is irreversibly lifeless.1,2 This can apply both to death determined by circulatory-respiratory criteria and death determined by neurologic criteria.3 However, the idea that we can rely on permanence rather than irreversibility has been heavily criticized.4,5

Permanence vs Irreversibility—General Points

If we find ourselves resisting permanence, it is likely that we have in mind the situation where it would be appropriate to do all we can to bring someone back to life. Alternatively, we might resist it because we think that we must make absolutely no exception to the requirement that we know irreversibility has been reached.

However, for practical reasons, it is simply not true that in most hospital death determinations, we know that irreversibility has been reached when death is declared.6 Critics of the circulatory-respiratory standard either ignore this or dismiss its relevance. But the justification for not having to know that the point of irreversibility is reached is relatively straightforward.

In cases where resuscitative measures are not appropriate, what is important is that the heart has beaten for the last time spontaneously, of its own accord. Because we know that (1) the only way it could restart is through resuscitative measures and (2) these measures are not appropriate, we can justifiably include these patients under the concept of death. Permanence is met both when irreversibility is met and when the conditions described earlier, where resuscitation is not appropriate, are met. In that sense, it is broader.

However, an objection to permanence is that it can apply where we do not want it to, for example, where a solitary traveler collapses from cardiac arrest and there is nobody for miles around who could come and perform cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. The argument is that, in this case, this person would be dead when the heart stops or shortly after because the cessation of circulation is permanent. But surely, we do not want to admit this. Yet consistency seems to require that we say exactly the same thing in all cases, not just in those special cases where someone dies in hospital with a do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) order.

The reply to this worry is that the concept of permanence, as with any concept, can be applied in different ways, depending on the circumstances. This position only seems unacceptable if we think of definitions as statements of fact. But they are not. They are rules governing the use of the relevant terms and concepts.7 As such, it is human beings who devise the rules. We did not discover that gold means having atomic number 79, but instead, we discovered that what we call “gold” has atomic number 79, and we then made having atomic number 79 part of the meaning of “gold.”8

It is the same with death. Some writers want to define death as the point at which entropic forces irreversibly exceed entropy-resisting forces.9 They are free to do this, but in doing so, they do not discover the meaning of death. Instead, they make a recommendation that we ought to define death in this way. Those who accept permanence as sufficient for death in circumstances where resuscitation is not appropriate have made the same move, albeit with a different recommended definition. They have said: “let's define death in terms of the permanent cessation of circulatory function, since this covers cases of irreversibility anyway, but we also need to cover cases where the heart has stopped for the last time (it won't restart spontaneously), and resuscitation is inappropriate. For we don't know how long we'd have to wait for irreversibility to occur, and it's simply unnecessary to wait in these cases.”

It therefore makes sense to stress the possibility of resuscitation where resuscitative measures are appropriate and stress the fact that the heart has beaten for the last time where they are not. In the solitary traveler case mentioned earlier, although resuscitation is not physically possible, it remains in principle appropriate, so we would not know that cessation of circulation is irreversible just after the heart has stopped. But with hospital patients with a DNAR order, we know they cannot revive unless impermissible measures are applied. So emphasis on the last heartbeat is much more appropriate. We are free to choose what to emphasize in a given context.

Relevant here is the fact that we could actually restart circulation even if we could not restore an acceptable level of brain function. Most studies that speculate on when the point of irreversibility is reached are tacitly assuming that resuscitative efforts are pointless beyond a certain time frame, but this is because, at that point and beyond, brain function could not be restored to an acceptable level, not that it could not be restored at all. This is why we need to define death in terms of permanence, indexed to relevant contexts such as those described earlier. Even opponents of permanence rely on it in their medical practice.

Permanence vs Irreversibility in Determining Death by Neurologic Criteria

Is a brain resuscitatable after a determination of death by neurologic criteria just as a heart is resuscitatable after a determination of death by circulatory-respiratory criteria? Theoretically yes. Consider therapeutic decompressive craniectomy (DC).10-13 This is a surgical intervention that removes part of the skull in patients with severe brain swelling to reduce life-threatening intracranial pressure. It would not be appropriate, however, to perform DC on all patients determined dead by neurologic criteria, although this could certainly be performed on some of these patients, thereby raising the theoretical potential of restoring some function. There is no difference in principle between DC here and conventional cardiopulmonary or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation resuscitation for patients determined dead on the circulatory-respiratory criterion. This point will only become ever more important as new neurologic therapies and technology advances.14 This makes the permanence-irreversibility distinction as important in neurologic criteria as it has been in determination of death by circulatory-respiratory criteria. We therefore conclude that permanence suffices for determining death by either circulatory or neurologic criteria.

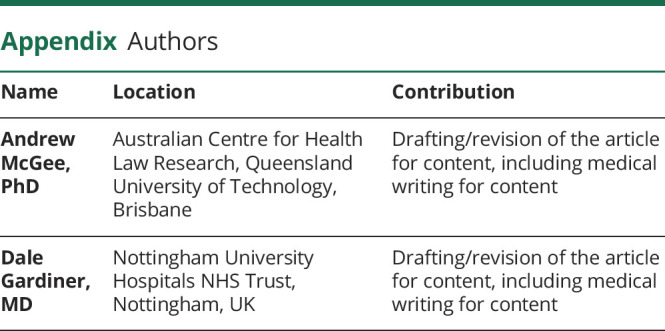

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

See page 181

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

D. Gardiner is the Associate Medical Director for Deceased Organ Donation with NHS Blood and Transplant, UK. A. McGee reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Bernat JL. Point: are donors after circulatory death really dead, and does it matter? Yes and yes. Chest. 2010;138(1):13-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGee A, Gardiner D. Permanence can be defended. Bioethics. 2017;31(3):220-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardiner D, McGee A, Bernat JL. Permanent brain arrest as the sole criterion of death in systemic circulatory arrest. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(9):1223-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joffe AR, Carcillo J, Anton N, et al. Donation after cardiocirculatory death: a call for a moratorium pending full public disclosure and fully informed consent. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2011;6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truog RD, Miller FG. Counterpoint: are donors after circulatory death really dead, and does it matter? No and not really. Chest 2010;138(1):16-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardiner D, Housley G, Shaw D. Diagnosis of death in modern hospital practice. In: Leisman G, Merrick J, eds. Functional Neurology: Considering Consciousness Clinically. Nova Science Publishers; 2016:93-97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hacker PMS. Human Nature: The Categorial Framework. Wiley Blackwell; 2007:7-11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glock H. Wittgenstein v Quine on logical necessity. In: Teghrarian S, ed. Wittgenstein and Contemporary Philosophy. Thoemmes Press; 1994:211-220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller FG, Truog RD. Death, Dying, and Organ Transplantation: Reconstructing Medical Ethics at the End of Life. Oxford University Press; 2012:208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohan Rajwani K, Crocker M, Moynihan B. Decompressive craniectomy for the treatment of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Br J Neurosurg. 2017;31(4):401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, et al. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1493-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeiler F, Trickey K, Hornby L, Shemie S, Lo B, Teitelbaum J. Mechanism of death after early decompressive craniectomy in traumatic brain injury. Trauma. 2018;20(3):175-182. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter U, Eggert M, Walther U, et al. A red flag for diagnosing brain death: decompressive craniectomy of the posterior fossa. Can J Anesth. 2022;69:900-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vrselja Z, Daniele SG, Silbereis J, et al. Restoration of brain circulation and cellular functions hours post-mortem. Nature. 2019;568(7752):336-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]