Abstract

Background and Objectives

The classic and singular pattern of distal greater than proximal upper extremity motor deficits after acute stroke does not account for the distinct structural and functional organization of circuits for proximal and distal motor control in the healthy CNS. We hypothesized that separate proximal and distal upper extremity clinical syndromes after acute stroke could be distinguished and that patterns of neuroanatomical injury leading to these 2 syndromes would reflect their distinct organization in the intact CNS.

Methods

Proximal and distal components of motor impairment (upper extremity Fugl-Meyer score) and strength (Shoulder Abduction Finger Extension score) were assessed in consecutively recruited patients within 7 days of acute stroke. Partial correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between proximal and distal motor scores. Functional outcomes including the Box and Blocks Test (BBT), Barthel Index (BI), and modified Rankin scale (mRS) were examined in relation to proximal vs distal motor patterns of deficit. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping was used to identify regions of injury associated with proximal vs distal upper extremity motor deficits.

Results

A total of 141 consecutive patients (49% female) were assessed 4.0 ± 1.6 (mean ± SD) days after stroke onset. Separate proximal and distal upper extremity motor components were distinguishable after acute stroke (p = 0.002). A pattern of proximal more than distal injury (i.e., relatively preserved distal motor control) was not rare, observed in 23% of acute stroke patients. Patients with relatively preserved distal motor control, even after controlling for total extent of deficit, had better outcomes in the first week and at 90 days poststroke (BBT, ρ = 0.51, p < 0.001; BI, ρ = 0.41, p < 0.001; mRS, ρ = 0.38, p < 0.001). Deficits in proximal motor control were associated with widespread injury to subcortical white and gray matter, while deficits in distal motor control were associated with injury restricted to the posterior aspect of the precentral gyrus, consistent with the organization of proximal vs distal neural circuits in the healthy CNS.

Discussion

These results highlight that proximal and distal upper extremity motor systems can be selectively injured by acute stroke, with dissociable deficits and functional consequences. Our findings emphasize how disruption of distinct motor systems can contribute to separable components of poststroke upper extremity hemiparesis.

Upper extremity motor control contains both proximal and distal elements. Proximal elements include shoulder strength and the ability to isolate movement (i.e., individuate) of the shoulder and elbow. Distal elements include finger strength and individuation (i.e., the ability to precisely control individual fingers). Studies using anatomical tracing, electrical stimulation, and neuroimaging in both nonhuman primates and humans have revealed that proximal vs distal upper extremity movements are distinctly organized throughout the neuro-axis. Proximal upper extremity movements are represented in a number of cortical areas spanning primary motor, premotor, and supplementary motor cortices1-4 and bilaterally.5,6 By contrast, distal movements are represented more focally, primarily isolated to contralateral primary motor cortex.7-10 Descending corticofugal axons enabling voluntary upper extremity movement originate from these distinct cortical motor areas, maintain their topographic organization in the corona radiata and internal capsule,11,12 and project through separate spinal motor columns to distinct spinal motor neuron pools (medial and ventral columns for proximal upper extremity vs lateral for distal upper extremity, respectively). Motor neuron pools for proximal upper extremity control span several cervical spinal cord segments while those for distal control are more selective.13 Furthermore, the striatum is known to influence proximal more than distal upper extremity segments, particularly the timing and coordination of shoulder and elbow movements.14,15

Together, this body of research indicates that there are 2 different and distinctly organized motor systems, one for proximal and another for distal upper extremity motor control. This model would predict there should be different proximal vs distal expressions of focal CNS injury such as stroke, depending on the topography of injury and specific structures affected. This study focuses on upper extremity deficits after stroke, which affect most stroke survivors and are a major source of stroke-related disability.16,17 Both proximal and distal upper extremity segments are affected by stroke. Classic studies posited that, early after stroke, distal segments are more affected than proximal segments and, consequently, that recovery of motor function follows a proximal to distal gradient.18-20 These observational reports were limited to small numbers of patients with frank hemiplegia. Subsequent quantitative studies, also in relatively small numbers of patients, called these findings into question, arguing that a proximal to distal gradient of deficits is not necessarily present early after stroke.21,22 There have not yet been studies that have quantified the relative prevalence of, functional consequences related to, and neuroanatomy associated with proximal vs distal predominant upper extremity deficits in a widely representative sample of patients after stroke.

The aims of this study were thus to (1) evaluate the relative prevalence of proximal vs distal upper extremity motor control deficits in a large and broadly representative sample of patients with acute stroke (2) investigate whether relative deficits in proximal motor control vs distal motor control acutely poststroke are related to differences in functional outcomes, and (3) test whether the neuroanatomic differences that underlie proximal vs distal upper extremity motor control in the healthy CNS underlie patterns of stroke-related motor deficits, specifically, that proximal motor deficits involve broad injury to corticofugal tracts, while distal motor deficits involve focal injury to primary motor cortex. To address these aims, we consecutively recruited and serially assessed 141 patients with upper extremity motor control deficits after acute stroke. We examined proximal and distal upper extremity deficits in relation to day 90 functional outcomes and stroke injury patterns on structural neuroimaging.

Methods

Participants

Patients were consecutively recruited as part of an ongoing prospective single-center natural history study of upper extremity motor recovery after stroke, Stroke Motor reHabilitation and Recovery sTudy (SMaHRT, clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT03485040).23,24 Eligible patients were those within 1 week of acute ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage who were between 18 and 90 years of age, able to follow simple commands in English, had unilateral upper extremity weakness (defined by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] Q5a or Q5b ≥ 1), and without significant impairments in consciousness (NIHSS score on Q1a and Q1b ≤ 1, and Q1c = 0), admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital stroke service. Patients with a history of developmental, neurologic, or major psychiatric disorders resulting in functional disability and those with visual or auditory disorders limiting their ability to participate in testing procedures were excluded. From June 1, 2017, to December 31, 2021, 3,195 consecutively admitted patients (ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage admissions to the Massachusetts General Hospital) were screened; 227 of these patients met study eligibility criteria and were approached for enrollment, and 141 patients consented to participate in this study.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants in the study provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at Mass General Brigham approved the study.

Upper Extremity Motor Evaluation, Proximal vs Distal Elements, and Functional Outcomes

Participants were evaluated with upper extremity assessments of motor impairment through the upper extremity Fugl-Meyer Motor Assessment25,26 (UE-FMA, 33 item subscores each range from 0 = cannot perform, 1 = performs partially, 2 = performs fully, maximum score 66, higher scores are better) and motor strength through Medical Research Council grades for shoulder abduction and finger extension (shoulder abduction and finger extension strength subscores, each range from 0 = no visible contraction, 1 = trace contraction, 2 = active movement with gravity eliminated, 3 = active movement against gravity but with no resistance, 4 = active movement against gravity with some resistance, and 5 = active movement against gravity with full resistance; summed together to obtain the Shoulder Abduction Finger Extension, SAFE score, maximum score 10).27 To examine proximal and distal motor control elements separately, we extracted flexor synergy (items 3–8) and hand (items 24–30) subscores of the UE-FMA28 as measures of proximal individuation (PI) and distal individuation (DI), respectively. We extracted shoulder abduction (SA) and finger extension (FE) subscores of the SAFE score as measures of proximal and distal strength, respectively. Proximal and distal scores were normalized by dividing the proximal or distal scores by the total possible score (12 and 14 for PI and DI UE-FMA subscores and 5 and 5 for SA and FE subscores, respectively). To examine the difference between proximal and distal elements accounting for the total extent of proximal and distal deficits (i.e., normalizing for total UE-FMA and SAFE scores), a normalized distal-proximal gradient was calculated as (normalized distal – normalized proximal)/(normalized proximal + normalized distal) scores. Patients with either (1) no proximal deficits and no distal deficits or (2) no proximal and no distal movement were not included in the gradient analysis.

Concurrent with upper extremity motor evaluation within 1 week of acute stroke, functional assessments including the Box and Blocks Test (BBT) and Barthel Index (BI) were administered. At 90 days after stroke, participants returned for repeat assessments. The modified Rankin scale (mRS) of global disability was also administered then. For participants who could not return for in-person evaluation (e.g., due to the COVID pandemic), the mRS and BI were collected through phone interview. All assessors underwent formal training certification and recertification annually.

Image Processing

Stroke topography was determined with magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted images obtained as part of the standard of care acute stroke inpatient workup. In 15 cases, CT scan was used instead of MRI (5 cases of intracerebral hemorrhage and in 10 cases where MRI was clinically contraindicated). Lesion delineation, spatial normalization, and registration were performed using well-established methods (additional details in eMethods, links.lww.com/WNL/C850).24,29 Participants had unilateral lesions, except 6 individuals who had punctate injury in the other hemisphere that was not felt to be exclusionary and thus not further considered. Right-sided stroke lesions were flipped to the left hemisphere for subsequent imaging analysis.

Voxel-Based Lesion Symptom Mapping, Permutation Statistics, and Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement

To understand where stroke-related injury was specifically related to proximal vs distal upper extremity deficits, we performed voxel-based lesion symptom mapping30 to generate t-maps that associate injury with behavior followed by permutation statistics, which identifies voxels with maximal differences in association with proximal deficits vs distal deficits. First, separate VLSM t-maps were generated for proximal and distal elements. Voxels were considered only if at least 5 patients exhibited a lesion at this location. The difference in t-maps (proximal – distal, t-mapdiff) was generated creating a difference t-statistic at each voxel. t-mapdiff has positive values where the association between proximal scores and voxel injury exceeds the association between distal scores and voxel injury. Conversely, t-mapdiff has negative values where the association between distal scores and voxel injury exceeds the association between proximal scores and voxel injury. To determine which voxels were associated with maximal differences (i.e., statistically significant differences on a voxelwise basis) in proximal vs distal motor scores, permutation statistics were performed (additional details in eMethods, links.lww.com/WNL/C850).

To identify ROIs associated specifically with proximal vs distal upper extremity deficits, we chose 6 cortical areas (M1 = primary motor cortex, PMd = dorsal premotor cortex, PMv = ventral premotor cortex, SMA = supplementary motor area, pre-SMA = pre-supplementary motor area, and S1 = primary somatosensory cortex), their associated 6 descending corticofugal tracts, and the striatum, as separate ROIs. A 6-mm radius ROI was drawn in the volumetric center of each cortical area. Corticofugal sensorimotor tracts available from the SMATT template31 and the striatal ROI from the AAL atlas32 were used. The search window was restricted to these 13 total ROIs, given their known relevance for upper extremity motor function. Within these ROIs, we performed threshold-free cluster enhancement, a generalization of cluster-based thresholding without the need to define a priori a cluster-forming threshold,33 using the difference t-maps (t-mapdiff) and permuted difference t-maps (t-mapdiff-permute) from VLSM. VLSM analyses were performed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc, Natick, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine distributions of upper extremity motor impairment and upper extremity strength within cluster severity ranges of the total UE-FMA (0–15 = severe, 16–34 = severe-to-moderate, 35–53 = moderate-to-mild, 54–66 = mild).34 The Spearman rank correlation was performed to examine the relationship between total UE-FMA and SAFE scores.

To determine convergence and separation among proximal and distal motor scores, we used partial correlation to test whether proximal elements (proximal individuation, PI, and proximal strength, SA) were more closely related to each other than to distal elements (distal individuation, DI, and distal strength, FE) and vice versa. Specifically, the relationship between PI and SA, after controlling for the association between PI and FE, was compared with the relationship between PI and FE, after controlling for the association between PI and SA. Separately, the relationship between DI and FE, after controlling for the association between DI and SA, was compared with the relationship between DI and SA, after controlling for the association between DI and FE. To determine whether these 2 differences in partial correlation coefficients were each statistically significant, we created an empirical distribution of 1,000 differences in partial correlation coefficients by permuting the PI or DI scores 1,000 times, performing the partial correlation analyses mentioned earlier, and generating the difference in partial correlations at each iteration. The initial difference in partial correlation coefficients was considered significant if it fell outside the 95% confidence interval of these empirical distributions.

The Pearson χ2 test was used to assess whether the proportion of patients with preserved distal motor control differed across stroke subtypes including ischemic stroke etiologies35 and intracerebral hemorrhage. To relate the normalized distal-proximal gradient to functional outcomes, Spearman rank correlations were performed between the normalized distal-proximal gradient and outcomes during the first week after stroke and at 90 days.

Data Availability

Data and analysis code that support the findings from this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Study Participants

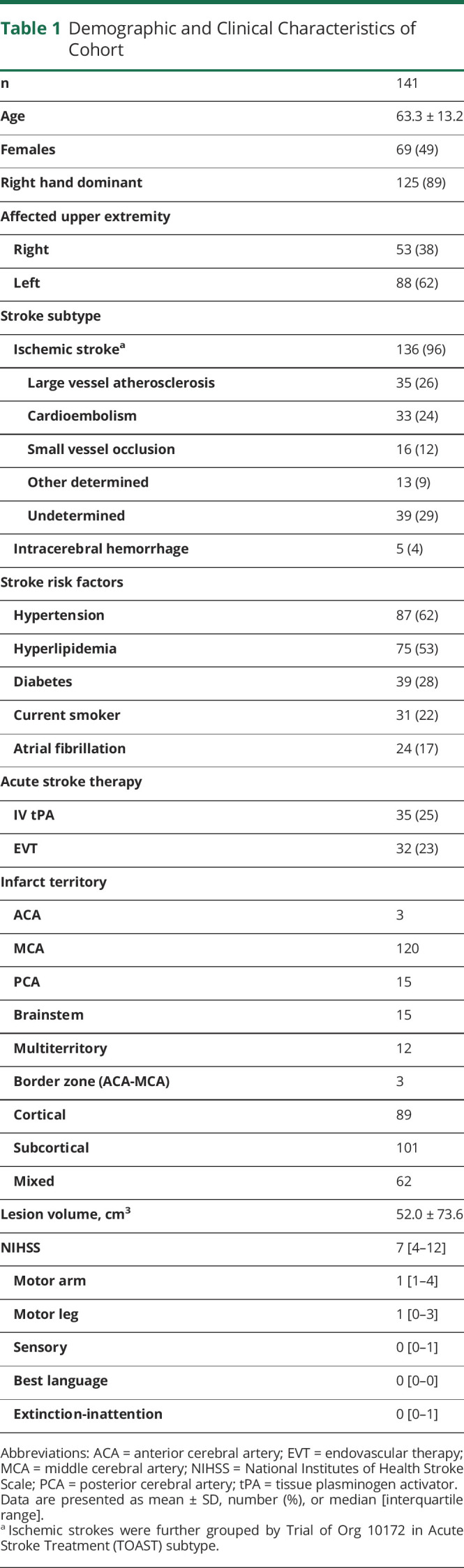

A total of 141 consecutive patients were assessed within 4.0 ± 1.6 (mean ± SD) days after acute stroke. The average age was 63.3 ± 13.2 years, gender was equally distributed (49% female), and there were a wide range of stroke etiology, vascular territories, and stroke severity involved (Table 1). 119 patients had 90-day evaluations for functional outcomes (86 patients through in-person evaluation and 33 through phone interview, due to COVID). The 22 patients lost to follow-up (12) and who withdrew from the study (10) did not differ in age (p = 0.09), gender (p = 0.3), initial stroke severity (p = 0.9), or initial UE-FM (p = 1.0) from those included in the functional outcome analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cohort

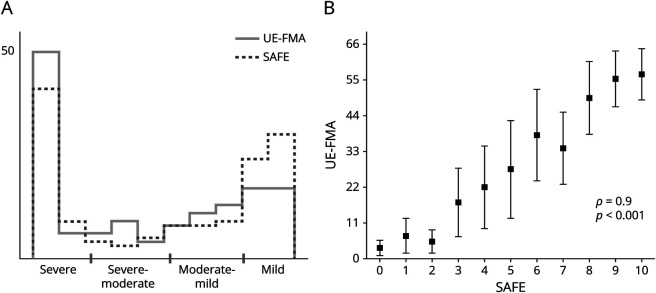

Distributions of Upper Extremity Strength and Motor Impairment After Acute Stroke

A bimodal distribution was present acutely after stroke across 2 dimensions of upper extremity motor control: motor impairment (UE-FMA) and strength (SAFE) (Figure 1A), with 63% of patients showing either severe (40%) or mild (23%) upper extremity motor impairment. There was a very strong relationship (ρ = 0.9, p < 0.001) between initial upper extremity motor impairment and strength (Figure 1B). Thus, after acute stroke, overall upper extremity motor impairment and strength followed a bimodal distribution and were closely related.

Figure 1. Upper-Extremity Motor Impairment and Strength Are Bimodal and Closely Related After Acute Stroke.

(A) Histograms of total upper extremity Fugl-Meyer (UE-FMA, motor impairment) and shoulder abduction finger extension (SAFE, strength) scores for n = 141 consecutively recruited patients with upper extremity weakness after acute stroke. X-axis shows severity ranges of upper extremity motor impairment, as defined in the study conducted Woytowicz et al.34 (B) Plot showing UE-FMA ranges (mean ± SD) for each level of total SAFE score. The relationship between upper extremity motor impairment and strength was as follows: Spearman rank correlation coefficient, ρ = 0.9, p < 0.001.

Separate Proximal and Distal Motor Syndromes Can Be Distinguished After Stroke

We isolated proximal and distal components of motor impairment and strength, respectively, and assessed their relationships. Motor impairment was examined using individuation in the shoulder and elbow proximally (PI) and at the fingers distally (DI). Strength was examined using SA proximally, and FE distally.

In partial correlation analysis, DI had a much stronger relationship with distal weakness (FE, r = 0.77, p = 1.1e−28) than it did with proximal weakness (SA, r = 0.31, p = 1.8e−4), and furthermore, the difference in partial correlation coefficients was significantly different from chance (p = 0.002). Similarly, PI had a stronger relationship with proximal strength (SA, r = 0.58, p = 7.3e−14) than it did with distal strength (FE, r = 0.42, p = 3.2e−7), though here the difference in partial correlation coefficients did not reach significance (p = 0.16). Thus, distal upper extremity deficits can exist largely in the absence of clinically relevant proximal deficits while proximal upper extremity deficits commonly, but less exclusively, occur in the absence of clinically relevant distal deficits. This convergence indicates that there are distinguishable proximal vs distal upper extremity clinical syndromes of acute stroke.

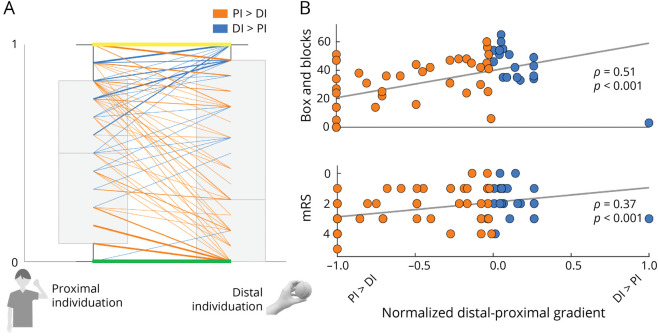

Preservation of Distal Motor Control Is Common After Acute Stroke

In this cohort of 141 consecutively recruited acute stroke patients, preserved distal individuation (i.e., DI > PI), based on UE-FMA subscores, was common (23%) (Figure 2A), as was relatively preserved proximal individuation (i.e., PI > DI), found in 47%. In patients with no difference (30%) in proximal vs distal elements, upper extremity deficits were either complete or absent both proximally and distally. When examining strength, based on SAFE subscores, 49% of patients had proximal vs distal differences; of them, 19% had relatively preserved distal strength compared with proximal strength (i.e., FE > SA). Thus, although proximal preserved motor control is more often seen for both individuation and strength, a pattern of distal preserved motor control is nonetheless common in the acute stroke setting.

Figure 2. Preservation of Distal Motor Control Is Common After Acute Stroke and Related to Better 90-Day Functional Outcomes.

(A) Boxplots (light gray boxes, in background) of normalized proximal (flexor synergy, items 3–8) and distal (hand, items 24–30) subscores of the upper extremity Fugl-Meyer are show in light gray. Superimposed are lines connecting the proximal and distal subscores for individual patients (the weighting of the line is scaled to the number of patients represented). Patients for whom proximal individuation > distal individuation (i.e., relatively preserved shoulder and elbow movements) are shown in orange. Patients for whom distal individuation > proximal individuation (i.e., relatively preserved hand and finger movements) are shown in blue. Green and yellow lines are patients for whom there was no gradient of proximal to distal motor control (PI-DI = 0). This occurred only in patients for whom there was either no movement (green) or complete movement (yellow) at proximal and distal segments. (B) Scatterplots of normalized distal-proximal gradient vs 90-day upper extremity function (Box and Blocks) and global function (modified Rankin Scale, mRS). Individual patients for whom PI > DI are shown in orange and DI > PI are shown in blue. A higher distal-proximal gradient (DI > PI) acutely was related to better 90-day upper extremity and global function.

Notably, when examining associated vascular correlates, the proportion of patients with preserved distal motor control did not differ across stroke subtypes including large artery atherosclerosis (most, 70%, of which were due to critical carotid stenosis, Table 1), for either individuation (p = 0.28) or strength (p = 0.38). Furthermore, there only were 3 patients with cortical border zone or “watershed” anterior cerebral artery-middle cerebral artery ischemic infarcts; contrary to common expectation, 2 of these patients exhibited preserved proximal individuation and strength (PI > DI and SA > FE).

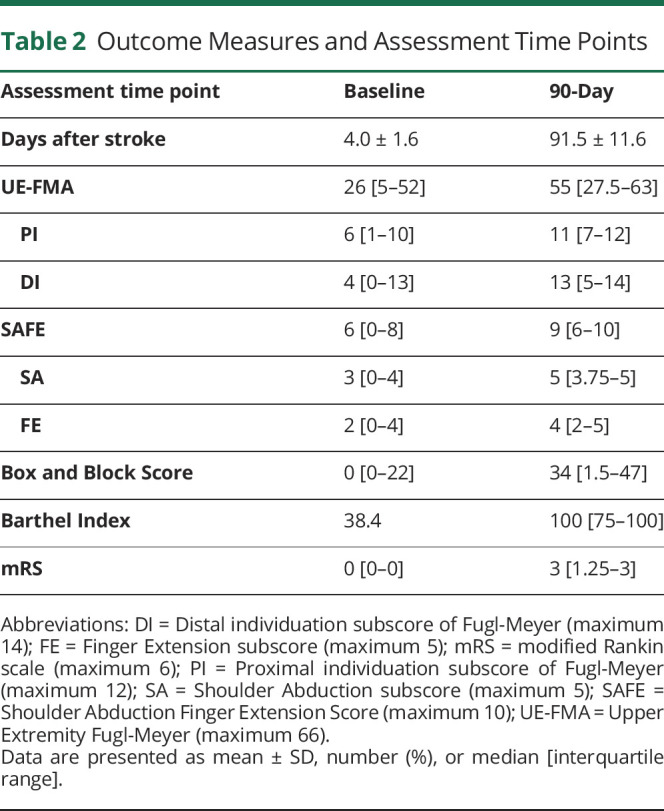

Acute Proximal vs Distal Upper Extremity Motor Patterns Have Distinct Functional Outcomes

Given that separate proximal and distal motor syndromes are each commonly observed, we asked how these 2 different patterns relate to functional outcomes. The normalized distal-proximal gradient adjusted the difference in PI and DI for total extent of deficits. In the first week after acute stroke, a higher distal-proximal gradient, reflecting better distal motor control, was related to better functional status in the upper extremity (Box and Block Test; ρ = 0.65, p < 0.001) and globally (Barthel Index; ρ = 0.39, p < 0.05; Table 2). Results were similar at 90 days: a higher distal-proximal gradient (DI > PI) acutely was related to better 90-day functional outcomes including scores of upper extremity function (BBT, ρ = 0.51, p < 0.001) and global function (BI, ρ = 0.41, p < 0.001; mRS, ρ = 0.38, p < 0.001; Table 2 and Figure 2B). Taken together, the distinguishable acute stroke proximal and distal upper extremity syndromes had distinct functional consequences: patients with relatively preserved distal motor control had better functional status, in the upper extremity and globally, both in the first week and at 90-day follow-up.

Table 2.

Outcome Measures and Assessment Time Points

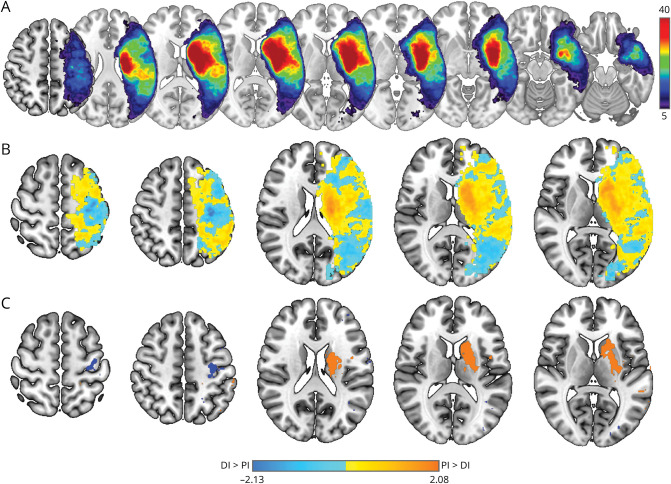

Proximal vs Distal Upper Extremity Motor Deficits Are Associated With Unique Stroke Injury Patterns

Stroke lesion overlap of the 141 participants in the study is shown in Figure 3A. There were widespread areas where injury related to both proximal and distal motor deficits, but within these areas, there was a tendency for specific regions to be more related to either proximal or distal deficits (Figure 3B). Brain regions in which stroke-related injury had a greater association with proximal deficits spanned deep hemispheric nuclei and white matter including striatum and both anterior and posterior limbs of the internal capsule (Figure 3C, orange). By contrast, brain regions in which stroke-related injury had a greater association with distal deficits were primarily restricted to the posterior bank of the precentral gyrus, with no extension into deep hemispheric nuclei, striatum, or descending white matter (Figure 3C, blue). The statistical significance of differences between proximal and distal VLSM maps was assessed in 13 predefined ROIs (6 cortical areas, their associated descending corticofugal sensorimotor tracts, and striatum) using threshold-free cluster enhancement (additional data are listed in eTable 1, links.lww.com/WNL/C850). Lesions causing greater proximal than distal individuation deficits were present in descending white matter tracts emanating from M1, PMd, PMv, SMA, pre-SMA, and striatum. On the contrary, lesions causing greater distal than proximal individuation deficits were present only in a single area, primary motor cortex. Taken together, deficits in proximal motor control were associated with widespread injury to subcortical white and gray matter, while deficits in distal motor control were isolated to injury within the posterior aspect of the precentral gyrus, that is, primary motor cortex.

Figure 3. Proximal vs Distal Upper Extremity Motor Deficits Are Associated With Unique Stroke Injury Patterns.

(A) Stroke lesion overlap map for 141 study participants. Color bar (right) shows the number of lesions overlapped and scaling with dark blue to red showing an increasing overlap. Separate VLSM t-maps were first generated for proximal individuation (PI) and distal individuation (DI) scores, flexor synergy and hand subscores of UE-FM, respectively. The difference (t-mapdiff) in raw t-maps (PI – DI in gradient orange and DI – PI in gradient blue) is shown in (B). This map has positive values (orange) where the association between proximal scores and voxel injury exceeds the association between distal scores and voxel injury and, conversely, negative values (blue) where the association between distal scores and voxel injury exceeds the association between proximal scores and voxel injury. Color bar with t-statistic range is shown at the bottom of the figure. Maximal voxelwise differences within t-mapdiff identified by permutation statistics are shown in (C).

Discussion

The existence of separable neural systems for the control of proximal vs distal upper extremity segments has long been recognized, for example, with Sir Charles Bell36 commenting that “the small hand muscles are characterized in action by their velocity rather than by their power, the proximal muscles by their power rather than by velocity of contraction. Their separate anatomic and functional organization would predict that proximal and distal upper extremity segments can each be selectively impaired by focal CNS injury and, consequently, that there should be distinguishable proximal vs distal upper extremity clinical syndromes after acute stroke, each associated with a specific injury pattern. To investigate this, in this study, we examined the clinical expression, functional outcomes, and neuroanatomical differences underlying proximal vs distal upper extremity motor control deficits in 141 patients averaging 4 days postacute stroke. Our main findings were that (1) proximal and distal deficits in upper extremity motor control could be distinguished, (2) a substantial number of acute stroke patients had relatively preserved distal motor control, (3) patients with preserved distal motor control had better functional outcomes both in the first week poststroke and at 90-day follow-up, and (4) deficits in proximal motor control were associated with injury to descending sensorimotor tracts from many corticomotor areas and striatum, while deficits in distal motor control were associated with isolated injury to primary motor cortex. Thus, proximal and distal motor syndromes after acute stroke have distinct clinical expression, functional outcomes, and underlying neuroanatomy. Together, these findings emphasize that the separable proximal and distal upper extremity neural systems normally present manifest with distinct clinical syndromes when injured by stroke.

A classic observational study of patients recovering from hemiplegia19 emphasized the relative preservation of proximal motor control immediately after acute stroke and the consequent proximal to distal pattern of return of upper extremity movement. However, the cohort in the study conducted by Twitchell was small (25 patients) and limited to those with initially severe hemiparesis (13 had no movement and 8 could make “weak” movements). In a more recent report, Beebe and Lang21 found no evidence of a proximal to distal gradient in either active range of motion or strength in patients tested 2 weeks after stroke. Although this study included a broader range of motor abilities, it was also a relatively small sample (33 patients), and neuroanatomical correlates were not available. In this study, in 141 consecutively recruited acute stroke patients, we showed that a distal to proximal gradient of deficits (i.e., where distal individuation was more preserved than proximal individuation) was relatively common (23%) in the first week after stroke. Notably, this pattern of deficits in our sample of patients was not due to the classically described anterior cerebral artery-middle cerebral artery border zone or watershed infarct from ipsilesional carotid disease.37 Furthermore, upper extremity motor control elements (i.e., strength and individuation) separated proximally from distally. Distal individuation and strength were clearly separable from proximal elements. Proximal individuation, although more strongly related to proximal strength, maintained a relationship with distal strength; this likely speaks to the greater relative contribution of distal circuits to proximal function than vice versa.38,39 Our findings extend prior literature by both highlighting the individual variability in clinical presentation of upper extremity syndromes after stroke and emphasizing how clinical expression of deficits after stroke mirrors selective organization of circuits in the healthy CNS (i.e., distinguishable circuits for proximal vs distal motor control).

Patients with relatively preserved distal individuation, even after controlling for the total extent of proximal and distal deficits, had better upper extremity and global function both in the first week and at 90 days after stroke. This emphasizes the critical importance of distal upper extremity motor control (i.e., hand and individuated finger movements) for picking up, transporting, and manipulating everyday objects.40,41 Prior studies have found that baseline hand function is a critical predictor of overall upper extremity improvement with therapy42 and that distal upper extremity–focused training is associated with greater motor gains than proximal arm training.38 Collectively, these studies attest to the value of careful bedside evaluation of patterns of movement after stroke, which can guide both recovery prediction and therapy after stroke.27

The differences in the anatomic and functional organization of proximal vs distal upper extremity motor control in the healthy state would predict distinct stroke-related injury patterns. We hypothesized that the neuroanatomic differences that underlie proximal vs distal upper extremity movement in the healthy CNS would underlie patterns of stroke-related motor deficits. We found that deficits in proximal individuation were related to stroke injury to descending tracts emanating from a number of cortical motor regions and striatum, areas known to be important for proximal motor control, while deficits in distal individuation were related to focal injury within the posterior aspect of the precentral gyrus, that is, primary motor cortex. Thus, injury after stroke produces a pattern of behavioral deficits that is consistent with the cerebral organization of proximal vs distal upper extremity motor systems in the intact CNS. Although voxel-based analyses of stroke neuroimaging do not allow for parsing cortical areas with single-cell resolution, our findings are consistent with neurophysiologic studies showing that anterior frontal motor areas and their associated outflow tracts exhibit overlap in the representation of different upper extremity segments,43 while posterior perirolandic motor areas have more specialized representations (i.e., for distal upper extremity movement).44-46 Furthermore, our findings are in line with recent evidence pointing to separable components of poststroke hemiparesis47: proximal and distal motor control have distinct mechanistic underpinnings after acute stroke. We highlight the value of applying a deep understanding of normal anatomy and physiology to acute stroke: an infarct alters circuits in selective and predictable ways based on the normal structure and function of the healthy CNS.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Proximal and distal motor control were assessed using subscales of the upper extremity Fugl-Meyer and Shoulder Abduction Finger Extension scores. More nuanced tests to assess different aspects of proximal and distal motor control (active range of motion, more complete characterization of muscle strength including elbow flexion/extension and finger flexion, dexterity, and kinematics) would have been useful but were not feasible, given the limited time available to collect data during the acute stroke hospitalization. Relationship of proximal and distal motor control to function was measured with Box and Blocks, a test of gross manual dexterity, and BI and mRS, measures of global function and disability, respectively. Multidimensional measurements of quality of life would be useful to further understand the relationship between clinical expression of upper extremity motor deficits and functional outcomes. Stroke injury was estimated from acute MR diffusion images and CT scans for ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage, respectively. Our voxel-based lesion symptom mapping analysis was performed using unilateral lesions (right hemisphere lesions were flipped onto the left hemisphere). We acknowledge that this method does not allow us to examine contributions of hemispheric laterality to motor control,48,49 which would be of high future interest. Finally, incorporating more detailed structural neuroimaging (i.e., diffusion tensor imaging) and real-time functional neuroimaging to probe circuits underlying proximal vs distal motor control after stroke was not performed in this study but is a ripe for future study.

Our findings have implications for personalized neurorehabilitation. Clinicians, rehabilitation clinical trials, and neurotechnological approaches to stroke rehabilitation should incorporate proximal vs distal upper extremity motor syndromes and their distinct neuroanatomy as separate targets for improving different aspects of poststroke motor function. Altogether, this study moves us closer to the vision of Axel Fugl-Meyer50: “It is suggested that in patients found suited for admittance to rehabilitation wards, visualization of the brain damage may be a useful adjunct when stating the goals for the rehabilitation process.”

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Maryam Masood for project regulatory support.

Glossary

- BBT

Box and Blocks Test

- BI

Barthel Index

- DI

distal individuation

- FE

finger extension

- M1

primary motor cortex

- mRS

modified Rankin scale

- NIHSS

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

- PI

proximal individuation

- PMd

dorsal premotor cortex

- PMv

ventral premotor cortex

- pre-SMA

presupplementary motor area

- S1

primary somatosensory cortex

- SA

shoulder abduction

- SMA

supplementary motor area

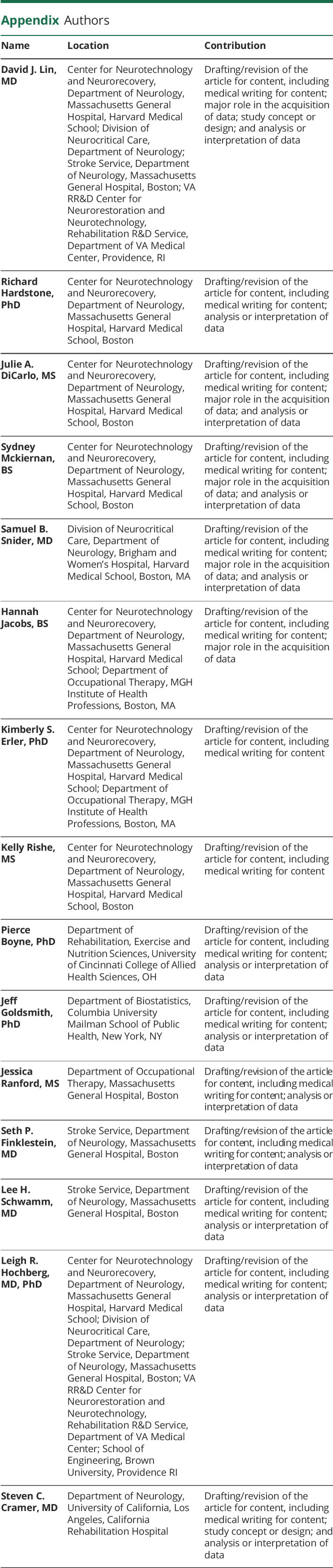

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 149

Study Funding

This research was supported by a career development award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (1IK2RX004237, Dr. Lin), a clinical research training scholarship grant from the American Academy of Neurology (Dr. Lin), and the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Neurology. Dr. Snider is supported by a clinical research training scholarship grant from the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Boyne was supported by the NIH grant R01HD093694.

Disclosure

D.J. Lin has served as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and Neurotrauma Sciences and provides consultative input for The MGH Translational Research Center (on clinical research support agreements with BrainQ, Constant Therapy, Constant Therapeutics, Imago Rehab, and Reach Neuro). S.B. Snider is a site investigator on a Biogen-funded clinical trial that is unrelated to this work. K. Rishe provides consultative input for the MGH Translational Research Center (on a clinical research support agreement with Constant Therapeutics). L.R. Hochberg provides consultative input for the MGH Translational Research Center (on clinical research support agreements with Neuralink, Synchron, Reach Neuro, Axoft, and Precision Neuro). S.C. Cramer serves as a consultant for Abbvie, Constant Therapeutics, MicroTransponder, Neurolutions, SanBio, Panaxium, NeuExcell, Elevian, Medtronic, Helius, Omniscient, and TRCare. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Dum RP, Strick PL. The origin of corticospinal projections from the premotor areas in the frontal lobe. J Neurosci. 1991;11(3):667-689. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.11-03-00667.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graziano MS, Taylor CS, Moore T. Complex movements evoked by microstimulation of precentral cortex. Neuron. 2002;34(5):841-851. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00698-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keizer K, Kuypers HG. Distribution of corticospinal neurons with collaterals to the lower brain stem reticular formation in monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Exp Brain Res. 1989;74(2):311-318. doi: 10.1007/bf00248864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nirkko AC, Ozdoba C, Redmond SM, et al. Different ipsilateral representations for distal and proximal movements in the sensorimotor cortex: activation and deactivation patterns. Neuroimage. 2001;13(5):825-835. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkman J, Kuypers HG. Cerebral control of contralateral and ipsilateral arm, hand and finger movements in the split-brain rhesus monkey. Brain. 1973;96(4):653-674. doi: 10.1093/brain/96.4.653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wassermann EM, Fuhr P, Cohen LG, Hallett M. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on ipsilateral muscles. Neurology. 1991;41(11):1795-1799. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.11.1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beisteiner R, Windischberger C, Lanzenberger R, et al. Finger somatotopy in human motor cortex. Neuroimage. 2001;13(6):1016-1026. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoi A, Arbuckle SA, Diedrichsen J. The role of human primary motor cortex in the production of skilled finger sequences. J Neurosci. 2018;38(6):1430-1442. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2798-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer SC, Finklestein SP, Schaechter JD, Bush G, Rosen BR. Activation of distinct motor cortex regions during ipsilateral and contralateral finger movements. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(1):383-387. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penfield W, Boldrey E. Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain. 1937;60(4):389-443. doi: 10.1093/brain/60.4.389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morecraft RJ, Herrick JL, Stilwell-Morecraft KS, et al. Localization of arm representation in the corona radiata and internal capsule in the non-human primate. Brain. 2002;125(1):176-198. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fries W, Danek A, Scheidtmann K, Hamburger C. Motor recovery following capsular stroke. Role of descending pathways from multiple motor areas. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 2):369-382. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.2.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter R, Lemon R. Corticospinal Function and Voluntary Movement. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nixon PD, Passingham RE. The striatum and self-paced movements. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112(3):719-724. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.112.3.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crenna P, Carpinella I, Lopiano L, et al. Influence of basal ganglia on upper limb locomotor synergies. Evidence from deep brain stimulation and L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131(12):3410-3420. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama H, Jorgensen HS, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of upper extremity function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(4):394-398. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90161-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson LA, Hayward KS, McPeake M, Field TS, Eng JJ. Challenges of estimating accurate prevalence of arm weakness early after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2021;35(10):871-879. doi: 10.1177/15459683211028240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walshe F. On the role of the pyramidal system in willed movements. Brain. 1947;70(3):329-354. doi: 10.1093/brain/70.3.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Twitchell TE. The restoration of motor function following hemiplegia in man. Brain. 1951;74:443-480. doi: 10.1093/brain/74.4.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denny-Brown D. Disintegration of motor function resulting from cerebral lesions. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1950;112(6):1-45. doi: 10.1097/00005053-195012000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beebe JA, Lang CE. Absence of a proximal to distal gradient of motor deficits in the upper extremity early after stroke. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(9):2074-2085. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.04.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bard G, Hirschberg GG. Recovery of voluntary motion in upper extremity following hemiplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1965;46:567-572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin DJ, Erler KS, Snider SB, et al. Cognitive demands influence upper extremity motor performance during recovery from acute stroke. Neurology. 2021;96(21):e2576-e2586. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000011992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin DJ, Cloutier AM, Erler KS, et al. Corticospinal tract injury estimated from acute stroke imaging predicts upper extremity motor recovery after stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(12):3569, 3577. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.119.025898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7:13-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.See J, Dodakian L, Chou C, et al. A standardized approach to the Fugl-Meyer assessment and its implications for clinical trials. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(8):732-741. doi: 10.1177/1545968313491000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nijland RH, van Wegen EE, Harmeling-van der Wel BC, Kwakkel G, Investigators E. Presence of finger extension and shoulder abduction within 72 hours after stroke predicts functional recovery: early prediction of functional outcome after stroke: the EPOS cohort study. Stroke. 2010;41(4):745-750. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.109.572065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senesh MR, Barragan K, Reinkensmeyer DJ. Rudimentary dexterity corresponds with reduced ability to move in synergy after stroke: evidence of competition between corticoreticulospinal and corticospinal tracts? Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34(10):904-914. doi: 10.1177/1545968320943582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rorden C, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J, Bender B, Karnath HO. Age-specific CT and MRI templates for spatial normalization. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):957-965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bates E, Wilson SM, Saygin AP, et al. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(5):448-450. doi: 10.1038/nn1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archer DB, Vaillancourt DE, Coombes SA. A template and probabilistic atlas of the human sensorimotor tracts using diffusion MRI. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28(5):1685-1699. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273-289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44(1):83-98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woytowicz EJ, Rietschel JC, Goodman RN, et al. Determining levels of upper extremity movement impairment by applying a cluster analysis to the Fugl-Meyer assessment of the upper extremity in chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(3):456-462. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams HP Jr., Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell C. The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments, as Evincing Design. Bell & Daldy; 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bogousslavsky J, Regli F. Borderzone infarctions distal to internal carotid artery occlusion: prognostic implications. Ann Neurol. 1986;20(3):346-350. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh YW, Lin KC, Wu CY, Shih TY, Li MW, Chen CL. Comparison of proximal versus distal upper-limb robotic rehabilitation on motor performance after stroke: a cluster controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20330-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi CD, Der-Yeghiaian L, Le V, Motiwala RR, Cramer SC. Robot-based hand motor therapy after stroke. Brain. 2008;131(2):425-437. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wing AM, Haggard P, Flanagan JR. Hand and Brain, Vol 4. Academic Press; 1996:4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D. The effects of hand strength on upper extremity function and activities of daily living in stroke patients, with a focus on right hemiplegia. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(9):2565-2567. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JJ, Shin JH. Predicting clinically significant improvement after robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation in subacute and chronic stroke. Front Neurol. 2021;12:668923. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.668923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willett FR, Deo DR, Avansino DT, et al. Hand knob area of premotor cortex represents the whole body in a compositional way. Cell. 2020;181(2):396-409.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nudo RJ, Wise BM, SiFuentes F, Milliken GW. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science. 1996;272(5269):1791-1794. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yousry TA, Schmid UD, Alkadhi H, et al. Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. A new landmark. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 1):141-157. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suresh AK, Goodman JM, Okorokova EV, Kaufman M, Hatsopoulos NG, Bensmaia SJ. Neural population dynamics in motor cortex are different for reach and grasp. Elife. 2020;9:e58848. doi: 10.7554/elife.58848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadjiosif A, Branscheidt M, Anaya MA, et al. Dissociation between abnormal motor synergies and impaired reaching dexterity after stroke. J Neurophysiol. 2022;127(4):856-868. doi: 10.1152/jn.00447.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mani S, Mutha PK, Przybyla A, Haaland KY, Good DC, Sainburg RL. Contralesional motor deficits after unilateral stroke reflect hemisphere-specific control mechanisms. Brain. 2013;136(4):1288-1303. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zemke AC, Heagerty PJ, Lee C, Cramer SC. Motor cortex organization after stroke is related to side of stroke and level of recovery. Stroke. 2003;34(5):e23-e28. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000065827.35634.5e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundgren J, Flodstrom K, Sjogren K, Liljequist B, Fugl-Meyer AR. Site of brain lesion and functional capacity in rehabilitated hemiplegics. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1982;14(3):141-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and analysis code that support the findings from this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.