Abstract

Pediatric liver transplantation is a challenging surgical procedure requiring complex post-transplant patient management. Liver transplantation in children should ensure long-term survival and good health-related quality of life (HR-QOL), but data in the literature are conflicting. With the aim of investigating survival and psychosocial outcomes of patients transplanted during childhood, we identified 40 patients with ≥ 20-year follow-up after liver transplantation regularly followed up at our Institution. Clinical charts were reviewed to retrieve patients’ data. Psychosocial aspects and HR-QOL were investigated by an in-person or telephonic interview and by administering the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire through an online form. Ten- and 20-year patient survival was 97.5% (95% CI 92.8–100%), whereas 10- and 20-year graft survival was 77.5% (65.6–91.6%) and 74.8% (62.5–89.6%), respectively. At last follow-up visit, 31 patients (77.5%) were receiving a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Twelve (32.4%) patients obtained a university diploma or higher, whereas 19 (51.4%) successfully completed high school. 81.1% of patients were active workers or in education, 17.5% had children, and 35% regularly practiced sport. 25 patients answered to the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. More than 60% of respondents did not report any disability and the perceived physical status was invariably good or very good. Median scores for physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment were 16.6, 14.7, 16, and 15, respectively. Pediatric liver transplantation is associated with excellent long-term survival and good HR-QOL. Psychological health and environment represent areas in which support would be needed to further improve HR-QOL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13304-023-01608-2.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Pediatric, Health-related quality of life, Long-term outcomes, Immunosuppression

Introduction

As compared to adult liver transplantation (LT), pediatric LT is characterized by unique features concerning indications, surgical technique, and post-LT management. Given the constant improvement of survival outcomes after pediatric LT over the last decades [1–14], the focus has shifted toward management and prevention of long-term complications, including renal dysfunction, impaired linear growth, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease, and other side effects of chronic immunosuppression [15, 16]. Adherence to immunosuppression therapy and health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) represent crucial aspects during childhood and adolescence, with some studies having suggested inferior HR-QOL in pediatric recipients of an LT [5, 17, 18]. Furthermore, the recent COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated preexisting difficulties in coping with the constraints associated with being an LT recipient [19, 20].

Data concerning very long-term outcomes (≥ 20 years of follow-up) after pediatric LT are limited [10, 21, 22] and lack an in-deep evaluation of HR-QOL. Furthermore, other aspects like scholarity, work occupation, sport practicing, and parental status have been largely overlooked.

The ultimate goal of pediatric LT would be allowing long-term survival, good HR-QOL, and full reintegration as a functioning member of the society. Thus, with the aim of providing a comprehensive picture of long-term outcomes after pediatric liver transplantation, we conducted a retrospective study on pediatric LT recipients (age < 18 years) with a minimum follow-up of 20 years, with a particular focus on social integration aspects and HR-QOL.

Patients and methods

The pediatric liver transplant program at our Institution was started in 1995 and 186 pediatric LTs have been performed since. Furthermore, Italian patients from our region transplanted at the Abdominal Transplantation Unit—Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc in Brussels, Belgium are regularly followed up at our outpatient clinic, in the setting of a more than 3 decade-long collaboration between our two Institutions. After discharge from hospital and until 3-month follow-up, patients have blood tests checked every 15 days and a clinic appointment with an US scan monthly. After 3 months, follow-up schedule includes monthly blood tests and a clinic appointment, including a US scan, every 6 months, unless otherwise clinically indicated. After 5 years, clinic appointments and US scans are scheduled yearly. Protocol liver biopsies are performed 1, 3, and 5 years after LT, and every 5 years thereafter. Fibroscans are performed yearly except in the years in which a liver biopsy is programmed. Importantly, patients and their families have the possibility, in case of any concern, to directly contact by phone a member of the team, which is available every day during working hours. From our Institutional database, we identified 40 patients transplanted before January 1st, 2004, i.e., with a minimum follow-up of 20 years by the end of 2023. Data concerning the indication for LT, surgical technique, immunosuppression, as well as patient and graft survival were retrieved from clinical charts.

To investigate aspects concerning social integration, an in-person or telephonic interview was submitted to all included patients. Patients were asked whether they were in education or actively working, regularly practicing sport, and whether they were married and/or had children. Additional information was collected about the highest scholarly degree, the kind of work, the type and of frequency of sport activity, whether they were living alone or with a family, and the number of children.

Health-related QOL was investigated by administering the World Health Organization QOL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire, which is a validated tool for the assessment of HR-QOL (https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol). Briefly, WHOQOL-BREF is a 26-question questionnaire based on the WHOQOL-100. It allows assessing HR-QOL relative to four domains, namely physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment. Importantly, the questionnaire includes some preliminary questions for stratification purposes. The WHOQOL-BREF Italian translation available on the WHO website (https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/whoqol-bref/italian-whoqol-bref) was used to set up an online survey using the Google Forms app. According to WHO instruction, answers to each question were scored on a scale from 1 (worst score) to 5 (best score). Answers to questions 3, 4, and 26 (negatively phrased items) were recoded to match the scores obtained from other items. The mean of the scores for each domain question was then multiplied by 4, resulting in a scale from 4 (worst score) to 20 (best score) for each domain. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Istanbul and Helsinki declarations.

Unless otherwise specified, data are presented as counts (percentage) and median (interquartile range). Survival analysis was conducted using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival curves compared using the log-rank test. Data analysis and visualization was performed using R version 4.2.3 (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Some 40 patients with 20-year follow-up transplanted between January 30th, 1996 and November 11th, 2003 were included in the study. Of these, 17 were transplanted at our Institution, whereas 23 were transplanted at the Abdominal Transplantation Unit—Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc. The 17 patients from our center represented 9.1% of pediatric liver transplants performed at our Institution, whereas the 23 from Cliniques Saint-Luc represented 76.7% of pediatric liver transplant performed at other Institutions that are followed up at our center. One patient died during follow-up, whereas two were lost to follow-up. All other patients responded to the in-person or telephonic interview, whereas 25 (67.6%) answered also to the online WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire.

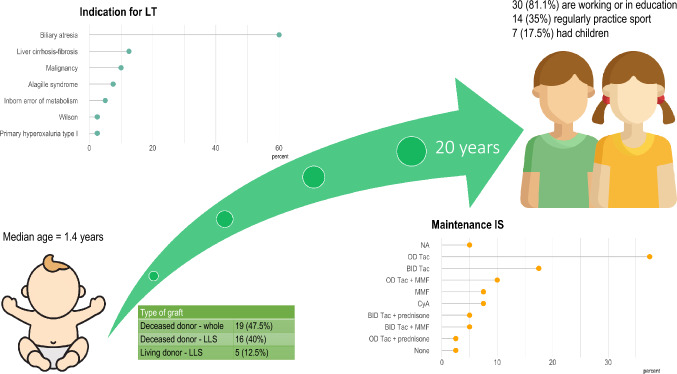

Baseline patient characteristics and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Median age at LT was 1.4 years, with 29 (72.5%) of recipients being male. Biliary atresia was by far the most frequent indication for LT in 24 (60%) of cases. Nineteen (47.5%) patients were transplanted with a whole graft from a deceased donor, 16 (40%) with a left lateral segments graft from a deceased donor, and 5 (12.5%) received a left lateral sector from a living donor. Three patients underwent combined liver–kidney transplantation, with grafts procured in all cases from deceased donors. Ten (25%) patients underwent retransplantation and 2 (5%) were retransplanted twice.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and long-term outcomes

| n | 40 |

| Gender | |

| F | 11 (27.5) |

| M | 29 (72.5) |

| Age | 1.4 [0.8, 3.3] |

| Indication for LT | |

| Biliary atresia | 24 (60.0) |

| Liver cirrhosis–fibrosis | 5 (12.5) |

| Malignancy | 4 (10.0) |

| Alagille syndrome | 3 (7.5) |

| Inborn error of metabolism | 2 (5.0) |

| Primary hyperoxaluria type I | 1 (2.5) |

| Wilson | 1 (2.5) |

| Type of graft | |

| Deceased donor—whole | 19 (47.5) |

| Deceased donor—LLS | 16 (40.0) |

| Living donor—LLS | 5 (12.5) |

| Combined liver–kidney transplant | 3 (7.5) |

| Re-LT | 10 (25.0) |

| Number of transplants | |

| 1 | 30 (75.0) |

| 2 | 8 (20.0) |

| 3 | 2 (5.0) |

| Maintenance IS | |

| BID Tac | 7 (18.4) |

| BID Tac + MMF | 2 (5.3) |

| BID Tac + prednisone | 2 (5.3) |

| CyA | 3 (7.9) |

| MMF | 3 (7.9) |

| None | 1 (2.6) |

| OD Tac | 15 (39.5) |

| OD Tac + MMF | 4 (10.5) |

| OD Tac + prednisone | 1 (2.6) |

| Scholarity | |

| University diploma or higher | 12 (32.4) |

| High school | 19 (51.4) |

| Middle school | 2 (5.4) |

| None | 4 (10.8) |

| Working or in education | 30 (81.1) |

| Had children | 7 (17.5) |

| Practice sport | 14 (35.0) |

Data are expressed as number (counts) or median (interquartile range)

LLS left lateral sector, LT liver transplantation, BID bis in die, Tac tacrolimus, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, CyA cyclosporin A, OD once daily

At last follow-up visit, most patients (n = 31; 77.5%) were receiving a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression (once daily, n = 20; twice daily, n = 11) (Fig. 1). Three (7.9%) were on cyclosporin A or mycophenolate mofetil monotherapy, respectively. Only one patient was off immunosuppression as a result of his decision to stop taking immunosuppressant, which did not result in acute rejection. As this was discovered months after he had stopped medications, immunosuppressant therapy was not resumed.

Fig. 1.

A visual summary of main study findings. Icons downloaded from Freepik.com

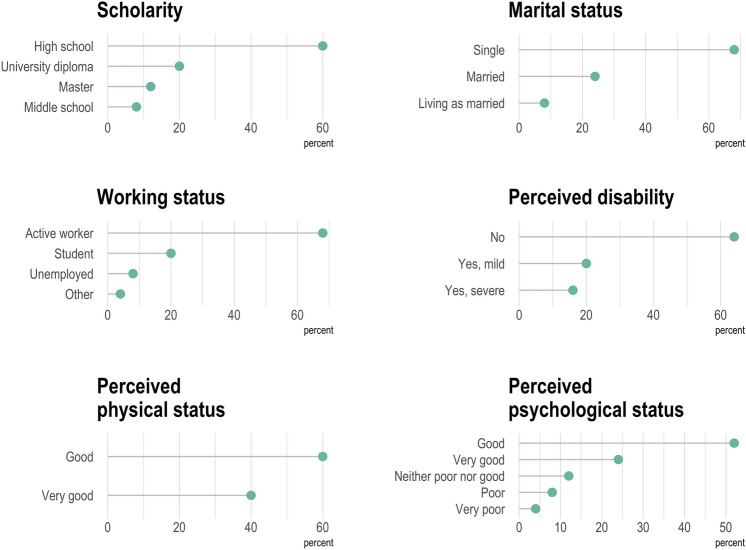

Patient and graft survival are depicted in Fig. 2. Median follow-up was 23 (21–27.8) years. Patient survival at 10 and 20 years was 97.5% (95% confidence interval 92.8–100%), whereas 10- and 20-year graft survival was 77.5% (65.6–91.6%) and 74.8% (62.5–89.6%), respectively. The only patient death in this series was due to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Causes of graft loss differed according to its timing. Among the four patients who lost their graft within 90 days from LT, hepatic artery thrombosis was observed in 3 (75%) patients, whereas primary non-function in 1 (25%). Seven grafts were lost later than 90 days after LT due to chronic rejection (n = 4, 57.1%), de-novo autoimmune hepatitis (n = 1, 14.3%), death with functioning graft (n = 1, 14.3%), and undetermined cause (n = 1, 14.3%). Median patient and graft survival were not reached during follow-up. Recipients of a whole graft from a deceased donor showed inferior graft survival as compared to the other groups (Fig. 2, third panel). This difference, however, did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves depicting patient and graft survival in the whole cohort. Third panel represents graft survival according to the type of graft (p value from log-rank test)

Results of the in-person or telephonic interview are summarized in Table 1. Twelve (32.4%) patients obtained a university diploma or higher, whereas 19 (51.4%) successfully completed high school. The majority of patients (n = 30, 81.1%) were active workers or in education, 7 (17.5%) had children, and 14 (35%) regularly practiced sport.

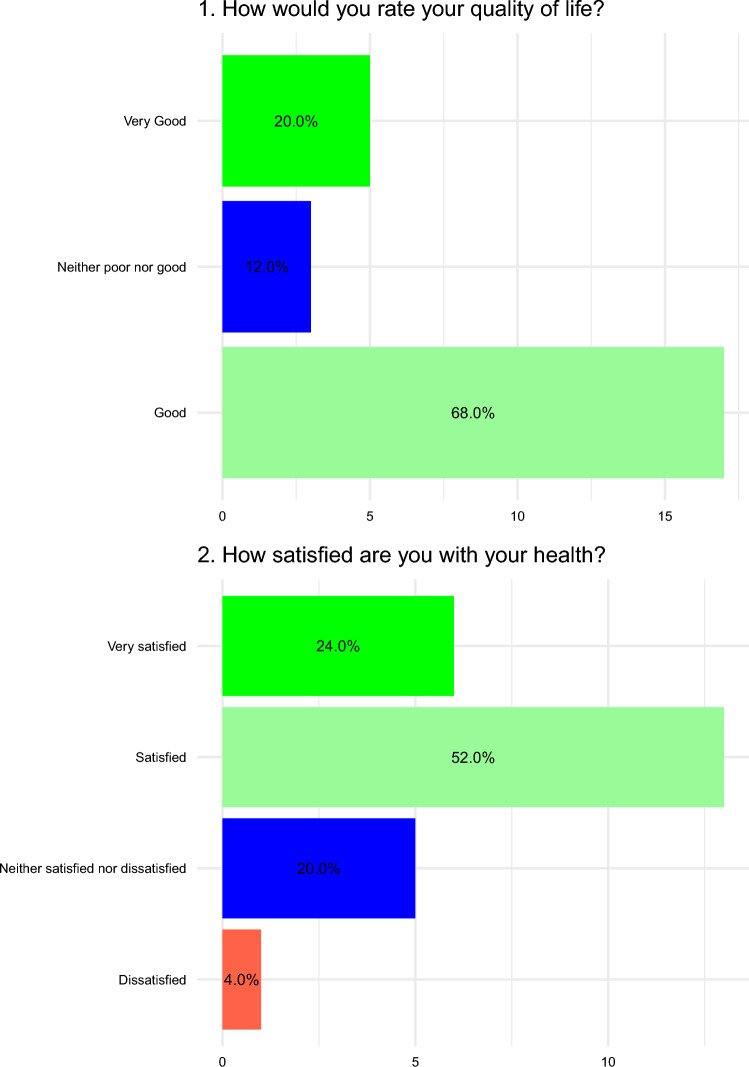

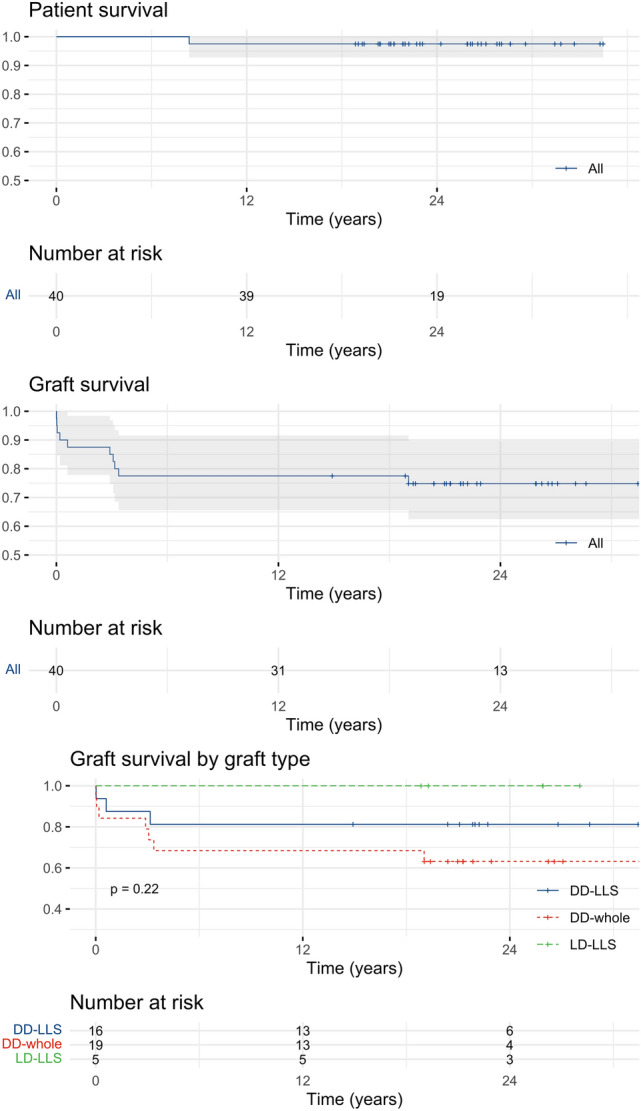

Figure 3 depicts answers to the introductory WHOQOL-BREF questions from the 25 participants who took the survey, substantially confirming what already shown by the interview. Notably, more than 60% of respondents did not report perceiving any disability and the perceived physical status was good or very good in 60% and 40% of cases, respectively. Results concerning psychological status were somewhat less brilliant, with 8% and 4% perceiving a poor or very poor psychological status, respectively. Figure 4 depicts answers to the first two questions of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, which are not included in any domain calculation. Overall, 68% and 20% of respondents would rate their quality of life as good or very good, respectively, whereas 52% and 24% were satisfied or very satisfied with their health. Answers to remaining questions are reported as supplementary material (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Overall, median scores for each domain were 16.6 for physical health, 14.7 for psychological health, 16 for social relationships, and 15 for environment (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Line plots with dots (lollipop plots) depicting answers to the introductory questions of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire by the 25 participants who answered to the survey

Fig. 4.

Bar plots with percentages representing answers to the first two questions of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the scores relative to the four domains of WHOQUOL-BREF questionnaire

| Min | Q1 | Median | Mean | Q3 | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 11.4 | 15.4 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 18.3 | 20.0 |

| Psychological | 8.7 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 14.4 | 15.3 | 19.3 |

| Social relationships | 5.3 | 13.3 | 16.0 | 14.3 | 16.0 | 17.3 |

| Environment | 8.5 | 13.5 | 15.0 | 14.7 | 16.0 | 17.5 |

Discussion

Our results show excellent long-term patient survival after pediatric LT and suggest that, despite the constraints linked to the status of LT recipient, social integration and good HR-QOL are frequent. It is noteworthy that more than 80% of patients in these series were actively working or in education at the moment they were interviewed, and that the perceived physical status was invariably good or very good.

As defined by World Health Organization, HR-QOL is “an individuals’ perception of own position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to own goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [23]. Liver transplantation in the pediatric age has the disruptive capacity of reversing the fate of young patients affected by incurable liver diseases or metabolic defects. It would be tempting to focus exclusively on excellent survival outcomes while overlooking the necessity to allow them to grow and develop as functioning members of the society. Long-term survival as chronically ill patients would be, however, at least partially deceiving. According to our data, pediatric LT is not only associated with excellent long-term patient survival but also with a good HR-QOL in most cases, with the majority of patients living a life very much close to what could be defined as normal.

In general, our results are in line with those from the literature [24–26]. In 2002, Atkinson et al. [3] showed that most pediatric LT recipient experiences normal growth and development, with about 90% of the patients transplanted in their childhood presenting with intellectual development appropriate for their age. In 2015, the Birmingham group explored the struggles and difficulties of young LT recipients in an article with a significant title: “‘It’s hard but you’ve just gotta get on with it’—The experiences of growing-up with a liver transplant” [18]. In this paper, 13 patients transplanted during their childhood or adolescence were interviewed, revealing how the perception of being different from their peers was frequent. This was mainly caused by the perception of their scars, the need to take immunosuppressants, and limitations to some everyday activities, like practicing contact sports. Konidis et al. [17] highlighted how engagement in full time work or study is associated with enhanced physical health. Mayer et al. [27] investigated long-term psychosocial outcomes in pediatric patients transplanted at Hannover Medical School before 2002. Most patients transitioned without problems to adult age and showed a high degree of self-esteem and social integration.

Our data also point to areas where there appears to be some room for improvement. Despite being in general quite satisfied by their physical health, patients were less so concerning psychological health and environment, suggesting that better support would be needed in these domains to further improve HR-QOL. Adolescence and young adulthood are ages in life in which social relationships are of utmost importance. The limitations inherent to the status of LT recipient may lead to the perception of be tagged as “different” and social isolation. While this did not appear to be a dramatic issue in our series, psychological support for patients and their families would be of undoubtful value. Also, while 35% percent of patients regularly practicing sport may seem encouraging, this should be taken as a starting point for further improvement, also given the well-known benefits of regular physical activity in solid organ transplant recipients [28]. Participating to associations and groups promoting sport practice among LT recipient has been demonstrated to improve physical fitness and health, and would have the added value of stimulating social interactions [29, 30]. Almost all patients were still on immunosuppressants 20 or more years after LT. How hard is going to be the management of the expectable side effects of immunosuppression during the subsequent follow-up remains an open question. Efforts aimed at minimizing or weaning immunosuppressive therapy have been mostly unsuccessful at our Institution (unpublished data) and it is concerning to observe how the landscape of immunosuppressive medications has not changed in the last two decades. Finally, in our series, a quarter of patients required a second graft, with chronic rejection being the main cause of late graft loss despite protocol biopsies were regularly performed [10]. This highlights the need for better and less-invasive tools to monitor the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy, like donor-derived cell-free DNA [31], and for a further expansion of pediatric donor pool by implementing liver splitting [32], utilizing novel dynamic approaches to organ preservation [33, 34] and exploiting DCD donors as a valuable source of pediatric liver grafts [2, 13].

Limitations of our study include study design and its retrospective, single-center nature, and its relatively small sample size, which limit the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. In particular, the lack of a matched comparison group of non-transplanted patients did not allow to put into context the good outcomes observed in our cohort. Response rate to the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was 25/37 (67.6%) and, although this figure is in line with those from the literature, a source of bias may originate from the fact that patients with a better perceived quality of life could have been more prone to answer the survey. Strengths are represented by the granularity of data, which was possible thanks to the decades-long relationship with our patients, and by the utilization of a validated HR-QOL assessment tool that was administered by an online form, a modality with which most patients were at ease with.

Conclusions

Pediatric liver transplantation is nowadays associated with excellent long-term survival outcomes and good HR-QOL. Psychological health and environment are areas where interventions would be required to further improve HR-QOL. Larger, multicenter, prospective studies are necessary to provide more robust evidence and to ascertain whether these good results will persist in the longer term follow-up.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

DC: study concept and design, data collection, and manuscript drafting; AP: data collection and manuscript drafting; SC: data collection and manuscript revision; CM and FA: data collection and manuscript drafting; PLC: study concept and manuscript revision; DP: data analysis and visualization, manuscript drafting, and revision; RR: manuscript revision and supervision.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Authors declare that no funding was received for this research.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest or competing interests.

Ethics approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval by the ethics committee was not sought due to the retrospective observational nature of the study.

Consent to participate

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interview.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of aggregate data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al Sayyed MH, Shamsaeefar A, Nikeghbalian S, Dehghani SM, Bahador A, Dehghani M, Rasekh R, Gholami S, Khosravi B, Malek Hosseini SA. Single center long-term results of pediatric liver transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18:65–70. doi: 10.6002/ect.2017.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alnagar A, Mirza DF, Muiesan P, Ong EGP, Gupte G, Van Mourik I, Hartley J, Kelly D, Lloyd C, Perera TPR, et al. Long-term outcomes of pediatric liver transplantation using organ donation after circulatory death: comparison between full and reduced grafts. Pediatr Transplant. 2022;26:e14385. doi: 10.1111/petr.14385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkison PR, Ross BC, Williams S, Howard J, Sommerauer J, Quan D, Wall W. Long-term results of pediatric liver transplantation in a combined pediatric and adult transplant program. CMAJ. 2002;166:1663–1671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakhtiyar S, Batra A, Malik T, Cotton R, Galvan NT, O'Mahony C, Goss J, Rana A. Three decades' analysis of pediatric liver transplantation outcomes reveals limited long-term improvements. Pediatr Transplant. 2022;26:e14158. doi: 10.1111/petr.14158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellini MI, Lauro A, D'Andrea V, Marino IR. Pediatric liver transplantation: long-term follow-up issues. Exp Clin Transplant. 2022;20:27–35. doi: 10.6002/ect.PediatricSymp2022.L16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couchonnal E, Jacquemin E, Lachaux A, Ackermann O, Gonzales E, Lacaille F, Debray D, Boillot O, Guillaud O, Wildhaber BE, et al. Long-term results of pediatric liver transplantation for autoimmune liver disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45:101537. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillaud O, Jacquemin E, Couchonnal E, Vanlemmens C, Francoz C, Chouik Y, Conti F, Duvoux C, Hilleret MN, Kamar N, et al. Long term results of liver transplantation for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gul-Klein S, Ollinger R, Schmelzle M, Pratschke J, Schoning W. Long-term outcome after liver transplantation for progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021 doi: 10.3390/medicina57080854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartleif S, Hodson J, Lloyd C, Cousin VL, Czubkowski P, D'Antiga L, Debray D, Demetris A, Di Giorgio A, Evans HM, et al. Long-term outcome of asymptomatic patients with graft fibrosis in protocol biopsies after pediatric liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2023 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinelli J, Habes D, Majed L, Guettier C, Gonzales E, Linglart A, Larue C, Furlan V, Pariente D, Baujard C, et al. Long-term outcome of liver transplantation in childhood: a study of 20-year survivors. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1680–1689. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanada Y, Sakuma Y, Onishi Y, Okada N, Hirata Y, Horiuchi T, Omameuda T, Lefor AK, Sata N. Long-term outcomes in pediatric patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation for biliary atresia. Surgery. 2022;171:1671–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shingina A, Vutien P, Uleryk E, Shah PS, Renner E, Bhat M, Tinmouth J, Kim J. Long-term outcomes of pediatric living versus deceased donor liver transplantation recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Transpl. 2022;28:437–453. doi: 10.1002/lt.26250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Rijn R, Hoogland PER, Lehner F, van Heurn ELW, Porte RJ. Long-term results after transplantation of pediatric liver grafts from donation after circulatory death donors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuen WY, Quak SH, Aw MM, Karthik SV. Long-term outcome after liver transplantation in children with type 1 glycogen storage disease. Pediatr Transplant. 2021;25:e13872. doi: 10.1111/petr.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKiernan PJ. Long-term care following paediatric liver transplantation. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2011;96:82–86. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng VL, Alonso EM, Bucuvalas JC, Cohen G, Limbers CA, Varni JW, Mazariegos G, Magee J, McDiarmid SV, Anand R, et al. Health status of children alive 10 years after pediatric liver transplantation performed in the US and Canada: report of the studies of pediatric liver transplantation experience. J Pediatr. 2012;160:820–6 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konidis SV, Hrycko A, Nightingale S, Renner E, Lilly L, Therapondos G, Fu A, Avitzur Y, Ng VL. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of paediatric liver transplantation. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:189–194. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.4.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright J, Elwell L, McDonagh JE, Kelly DA, Wray J. 'It's hard but you've just gotta get on with it'–the experiences of growing-up with a liver transplant. Psychol Health. 2015;30:1129–1145. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1024245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forner-Puntonet M, Gisbert-Gustemps L, Castell-Panisello E, Larrarte M, Quintero J, Ariceta G, Gran F, Iglesias-Serrano I, Garcia-Moran A, Espanol-Martin G, et al. Stress and coping strategies of families of pediatric solid organ transplant recipients in times of pandemic. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1067477. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1067477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Chukwusa E, Koffman J, Curcin V. Public opinions about palliative and end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a twitter-based study. JMIR Form Res. 2023 doi: 10.2196/44774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boillot O, Guillaud O, Pittau G, Rivet C, Boucaud C, Lachaux A, Dumortier J. Determinants of short-term outcomes after pediatric liver transplantation: a single centre experience over 20 years. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45:101565. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasahara M, Umeshita K, Eguchi S, Eguchi H, Sakamoto S, Fukuda A, Egawa H, Haga H, Kokudo N, Sakisaka S, et al. Outcomes of pediatric liver transplantation in Japan: a report from the registry of the Japanese liver transplantation society. Transplantation. 2021;105:2587–2595. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whoqol group The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the world health organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farooqui Z, Johnston M, Schepers E, Brewer N, Hartman S, Jenkins T, Bondoc A, Pai A, Geller J, Tiao GM. Quality of Life outcomes for patients who underwent conventional resection and liver transplantation for locally advanced hepatoblastoma. Children (Basel). 2023 doi: 10.3390/children10050890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JS, Groteluschen R, Mueller T, Ganschow R, Bicak T, Wilms C, Mueller L, Helmke K, Burdelski M, Rogiers X, et al. Pediatric transplantation: the Hamburg experience. Transplantation. 2005;79:1206–1209. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000160758.13505.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotb MA, Hamza AF, Abd El Kader H, El Monayeri M, Mosallam DS, Ali N, Basanti CWS, Bazaraa H, Abdelrahman H, Nabhan MM, et al. Combined liver-kidney transplantation for primary hyperoxaluria type I in children: single center experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23:e13313. doi: 10.1111/petr.13313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer K, Junge N, Goldschmidt I, Leiskau C, Becker T, Lehner F, Richter N, van Dick R, Baumann U, Pfister ED. Psychosocial outcome and resilience after paediatric liver transplantation in young adults. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosconi G, Angelini ML, Balzi W, Totti V, Roi GS, Cappuccilli M, Tonioli M, Storani D, Trerotola M, Costa AN. Can solid-organ-transplanted patients perform a cycling marathon? Trends in kidney function parameters in comparison with healthy subjects. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cappelle M, Masschelein E, De Smet S, Vos R, Vanbekbergen J, Gryp S, Van Craenenbroeck AH, Cornelissen V, Verreydt J, Van Belleghem Y, et al. Transplantoux. Beyond the successful climb of mont ventoux: the road to sustained physical activity in organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2021;105:471–473. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Smet S, O'Donoghue K, Lormans M, Monbaliu D, Pengel L. Does exercise training improve physical fitness and health in adult liver transplant recipients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2023;107:e11–e26. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schutz E, Fischer A, Beck J, Harden M, Koch M, Wuensch T, Stockmann M, Nashan B, Kollmar O, Matthaei J, et al. Graft-derived cell-free DNA, a noninvasive early rejection and graft damage marker in liver transplantation: a prospective, observational, multicenter cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angelico R, Trapani S, Spada M, Colledan M, de Ville de Goyet J, Salizzoni M, De Carlis L, Andorno E, Gruttadauria S, Ettorre GM, et al. A national mandatory-split liver policy: a report from the Italian experience. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2029–2043. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cussa D, Patrono D, Catalano G, Rizza G, Catalano S, Gambella A, Tandoi F, Romagnoli R. Use of dual hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion to recover extended criteria pediatric liver grafts. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:835–839. doi: 10.1002/lt.25759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spada M, Angelico R, Grimaldi C, Francalanci P, Saffioti MC, Rigamonti A, Pariante R, Bianchi R, Dionisi Vici C, Candusso M, et al. The new horizon of split-liver transplantation: ex situ liver splitting during hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:1363–1367. doi: 10.1002/lt.25843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Not applicable.