Abstract

Objective

Social determinants of health (SDoH) play critical roles in health outcomes and well-being. Understanding the interplay of SDoH and health outcomes is critical to reducing healthcare inequalities and transforming a “sick care” system into a “health-promoting” system. To address the SDOH terminology gap and better embed relevant elements in advanced biomedical informatics, we propose an SDoH ontology (SDoHO), which represents fundamental SDoH factors and their relationships in a standardized and measurable way.

Material and Methods

Drawing on the content of existing ontologies relevant to certain aspects of SDoH, we used a top-down approach to formally model classes, relationships, and constraints based on multiple SDoH-related resources. Expert review and coverage evaluation, using a bottom-up approach employing clinical notes data and a national survey, were performed.

Results

We constructed the SDoHO with 708 classes, 106 object properties, and 20 data properties, with 1,561 logical axioms and 976 declaration axioms in the current version. Three experts achieved 0.967 agreement in the semantic evaluation of the ontology. A comparison between the coverage of the ontology and SDOH concepts in 2 sets of clinical notes and a national survey instrument also showed satisfactory results.

Discussion

SDoHO could potentially play an essential role in providing a foundation for a comprehensive understanding of the associations between SDoH and health outcomes and paving the way for health equity across populations.

Conclusion

SDoHO has well-designed hierarchies, practical objective properties, and versatile functionalities, and the comprehensive semantic and coverage evaluation achieved promising performance compared to the existing ontologies relevant to SDoH.

Keywords: social determinants of health, SDoH, ontology, natural language processing, NLP

INTRODUCTION

Background and significance

There is increasing awareness that medical care alone cannot improve population health if social, economic, and environmental issues are not well addressed.1 The nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes are known as social determinants of health (SDoH). Specifically, SDoH are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”2 SDoH are closely tied to health behaviors, lifestyle, and interpersonal relations,3 and an increasing number of studies provide evidence for the impact of SDoH on health.1 Notably, SDoH are estimated to account for between 30% and 55% of health outcomes.4 Furthermore, SDoH significantly affect health inequity.

Understanding the interplay between SDoH and outcomes is a growing area of focus in healthcare for improving outcomes and addressing healthcare inequalities and disparities worldwide. However, currently, there exist inconsistencies in definitions in SDoH scope and domains across different efforts. For example, there are 5 categories classified by Healthy People 2030,5 but the categories from Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC) differ slightly, with an additional category of food. Wild’s framework includes concept of external exposome, which ranges from individual behaviors to environmental and broader societal aspects.6 A related concept is the socio-behavioral determinants of health (SBDH), which concerns the interplay of behavioral aspects of an individual’s life that affect individual and community health.7 Currently, there are heterogeneity gaps and lack of standardization in the SDoH semantic domain.8–10 Arons et al found that several concepts related to SDoH did not have a standard terminology code. Further, Resnick et al matched standard vocabularies with the Assessing Circumstances & Offering Resources for Needs (ACORN) survey and found the need in SDoH terminology representation.11 These heterogeneous categorizations of SDoH can impede our understanding of the associations between the factors and health conditions and further impact Natural Language Processing (NLP) accuracy. Thus, there is a need to standardize the categorization of SDoH. Ontologies, are widely used to identify, manage, and share semantic knowledge in a specific domain.12 Ontologies can assist with knowledge management and reasoning to improve semantic interoperability across systems or multiple data sources. In addition, ontologies can be used to test the consistency and ensure data quality, as they explicitly define the data types and precise terms.13 Furthermore, ontologies can also enhance computational power by reducing semantic ambiguity in deductive inferences and enable complex logical assertions and queries.14 Using ontologies in combination with artificial intelligence (AI) techniques can provide knowledge for decision support systems. As ontologies provide interoperability and formal definitions of the terms and structure of a domain and its subdomain relationships, an ontology-based approach can mitigate the issue of heterogeneity.8

Standardizing the SDoH factors with an ontology approach can address the challenge of heterogeneity embedded in SDoH definitions, categorizations, and applications. Currently, there are ontologies/terminologies that cover certain aspects of SDoH. However, none of the current ontologies that address SDoH provide a comprehensive representation of the determinants. (Details summarized in Supplementary Table S1). The Ontology of Medically Related Social Entities (OMRSE) covers health-related societal roles but lacks full coverage of social aspects that influence health.15,16 Melton et al’s study focused on public health surveys and clinical social history text but did not capture factors like neighborhood or community context.17 The Semantic Mining of Activity, Social, and Health (SMASH) ontology describes health social networks and interrelations between health, social activities, and physical activities, but it omits many aspects of SDoH, such as economics, education, and healthcare systems.18,19 Gharebaghi et al’s ontology focused on socio-environmental dimensions for people with motor disabilities and was not generalized for other populations.20 Kim et al’s Physical Activity Ontology (PACO) addresses physical or social-physical activities but does not cover community influences like economics, food, or education.21 Arons et al’s Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network (SIREN) links 20 SDoH factors to standardized medical systems but lacks comprehensiveness in other factors and relationships.9 Lastly, Rousseau et al’s ontology-driven framework collected SDoH concepts but did not define semantic meanings or relations, and the lack of multiple hierarchies limited its future application.22 Therefore, most works lack a comprehensive set of SDoH factors and measurements that researchers and practitioners can apply in the medical and public health fields.

Objective

To integrate the strengths of the existing frameworks and address what they lack, we propose an ontology (SDoHO) that aims to comprehensively represent the concepts, hierarchies, and relations pertinent to SDoH factors with comprehensive evaluation based on real-world data. We also collect available measurements to make our proposed ontology applicable to downstream analysis, including clinical medicine, public health, and biomedical informatics, facilitating systematic SDoH knowledge representation, integration, and reasoning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

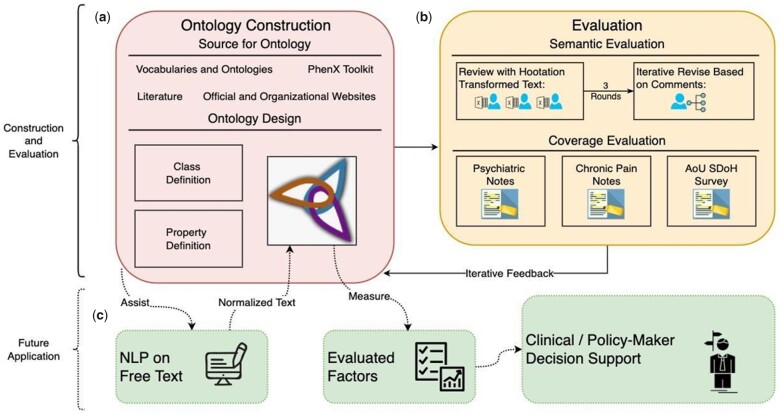

SDoHO was constructed mainly by manual development in Protégé 5.5.0 and represented in the Web Ontology Language (OWL2).23 Figure 1 shows the workflow of the SDoHO design requirements. After the ontology construction using various sources, we performed 3 rounds of semantic evaluation iteratively and coverage evaluation using real-world data from multiple sites. The feedback from the evaluations was then addressed in the ontology for future applications. Data sources and design considerations are summarized in box a. Two evaluation methods, semantic and coverage evaluation, on the proposed ontology were described in box b; and potential future applications are presented in box c.

Figure 1.

Overview schema of SDoHO construction, evaluation, and future application. (a) SDoHO construction, using various sources and design considerations. (b) Progress of semantic evaluation and coverage evaluation on the SDoHO. (c) Future step of SDoHO application in leveraging NLP tasks and further help with clinical decision support.

Data sources

To thoroughly integrate topics, concepts, and knowledge related to Social Determinants of Health (SDoH), a rigorous approach was employed to gather data from reliable sources, as indicated in Table 1. The data sources utilized in this study included: (1) Multiple official and institutional websites: A comprehensive search was conducted on established websites of reputable organizations, such as governmental health agencies, international health organizations, and renowned academic institutions. (2) standardized medical vocabularies and ontologies, (3) A review of relevant biomedical literature was conducted using established databases, such as PubMed and Google Scholar, to identify peer-reviewed articles, reviews, and guidelines related to SDoH,9,24–26 and (4) Additional resources, such as reports from reputable research institutes, policy briefs, and expert consensus statements, were consulted to capture comprehensive and up-to-date information on SDoH-related topics and concepts (details in Supplementary File).

Table 1.

SDoHO data sources and examples

| Source type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Official and institutional websites | WHO,4 CDC,27 Healthy People 2020,28 Healthy People 2030,2 Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF),29 Rural Health Information Hub,30 Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS),31 NEJM Catalyst,32 National Academy of Medicine (NAM),33 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation,34 and American Hospital Association (AHA)35 |

| Standardized medical vocabularies and ontologies | LOINC, SNOMED-CT, UMLS |

| Biomedical literature | 9 , 24–26 |

| Other resources | PhenX Toolkit |

Ontology design

The requirements for SDoHO design and development are as follows: (1) interoperability, (2) applicability, and (3) scalability. Hence, we created the classes and properties with optimum hierarchical organization from the beginning, holding space for scalability and compatibility. Our overall workflow of ontology development can be described as a top-down (knowledge-driven), followed by a bottom-up (data-driven) evaluation/validation and refinement approach.36,37

Class definition

Most of the SDoH data sources that we evaluated have 1–2 layers of hierarchy of the topics. After reviewing the categories, we first combined Healthy People 2030s 5-domain classification with LOINC’s 6-domain classification, which has an additional section for food. We also accommodated the definition of SBDH to include the behavioral and lifestyle aspects for comprehensiveness of the nonmedical factors. In addition, to extend applicability of the ontology with a societal role and the possible influence for the individual, we added both demographic and measurement categories after reviewing the OMRSE15,16 and PhenX Toolkit.38 We segmented terms that have no further hierarchical structure but a pool of SDoH topics into the 9 top-level domains. For the data sources that involved a layered structure, we incorporated the hierarchical classifications from those sources. In addition, concepts were primarily defined by aligning with available definitions from the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) with the Concept Unique Identifier (CUI).

Property definition

We designed the relationships meticulously in the proposed SDoHO, including object properties, data properties, and annotation properties. We also imported and inherently reused some existing ontologies to extend the coverage and flexibility of SDoHO’s relationships. We added object properties across domains into the proposed ontology when we identified the relation between classes. Some object properties were reused to formally define different classes when needed. Ranges and domains were restricted for specific object properties. Data properties were created to accommodate the usage between classes and data formats. We also added needed annotation properties to disambiguate concepts further.

Evaluation methods

Semantic evaluation

We first evaluated the ontology semantics. The semantic representation of the concepts and properties, including axioms, subclass hierarchies, and other restrictions from the ontology, were first transformed to natural language sentences using an ontology evaluation tool, Hootation,39 and evaluated by 3 human experts, who all had sophisticated experience in biomedical informatics. The 3 evaluators read the phrases and decided whether the organization of the proposed ontology was rational. We then recorded 2 agreement scores, interevaluator and rational agreement. The interevaluator agreement score was calculated by dividing the number of statements on which the 3 evaluators agreed (whether they decided the statements were rational or irrational), divided by the total number of statements. The rational agreement was calculated by dividing the number of statements all 3 evaluators deemed rational by the total number of statements.

Disagreements on concept and hierarchical definitions were addressed after evaluation. The evaluation processes were repeated 3 times until no further disagreement could be resolved. Classes that did not achieve rational agreement and that were unjustifiable were summarized. Further, corrections were made after each round of review. Classes and relations marked as irrational by any evaluator were discussed and revised iteratively for best agreed-upon achievement. For the ambiguous concepts, we added a description or definition to the ontology. For hierarchically irrational concepts, we merged, deleted, and added concepts for the best common sense structure. For irrational naming conventions, we updated the labels to be more precise.

Coverage evaluation

Two groups of evaluators collaboratively worked on the identification of SDoH factors from clinical notes. Two sets of real-world clinical notes were utilized for conceptual coverage evaluation of SDoHO. One was a subset of psychosocial assessment notes from The Harris County Psychiatric Center (HCPC), collected between January 1, 2007, and October 1, 2017 (over 100,000 patients). Social history sections, which were rich in SDoH-related factors, were extracted from these notes. A total of 300 social history sections were randomly selected and manually annotated for ontology evaluation. Another set comprised 507 clinical notes retrieved from the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center (OMC).40 The cohort consisted of local adult patients with noncancer chronic pain who received health care at the Mayo Clinic and/or the OMC between January 1, 2005, and September 30, 2015. The definition of chronic pain was based on Tian et al.41

In addition, the ontology’s coverage was evaluated against the NIH All of Us (AoU) Research Program’s SDoH survey,42 which was not used in the ontology construction phrase. The survey contains 13 domains with measurement items, gathered from various sources, to evaluate the participants’ own perceived feelings, influenced by the social surroundings. Each measurement item is a question collected from relevant sources. In our evaluation process, we compared the coverage of classes at the survey’s domain level and value/measurement level.

RESULTS

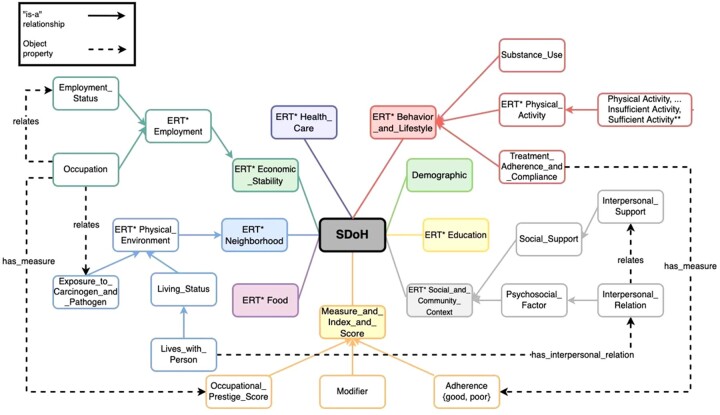

SDoHO is a comprehensive ontology with well-defined classes (concepts) and properties (relationships and features) represented in OWL2. The current version has 708 classes, 106 object properties, and 20 data properties, with 1,561 logical axioms and 976 declaration axioms. Figure 2 shows its core conceptual framework, including the main top-level classes and some subclasses to demonstrate the usage of object properties with partial details of the framework. The main top-level hierarchy comprises 9 categories. The maximum depth of the class hierarchy in the proposed SDoHO is 6.

Figure 2.

Abstract of the partial conceptual framework of SDoHO. The proposed SDoH ontology has 9 main top-level classes under SDoH aspects to represent the relevant factors comprehensively. Sample subclasses are shown to illustrate how SDoH factors were represented and their relationships could be defined using objective properties (simplified in the figure). The figure illustrates the “is-a” relationships by solid lines and the object properties, by dashed lines. The figure displays only partial subclasses and relationships for overview. Data properties and annotation properties are not displayed. *ERT: Element_Relevant_to_. **Imported subclasses from PACO.

Class

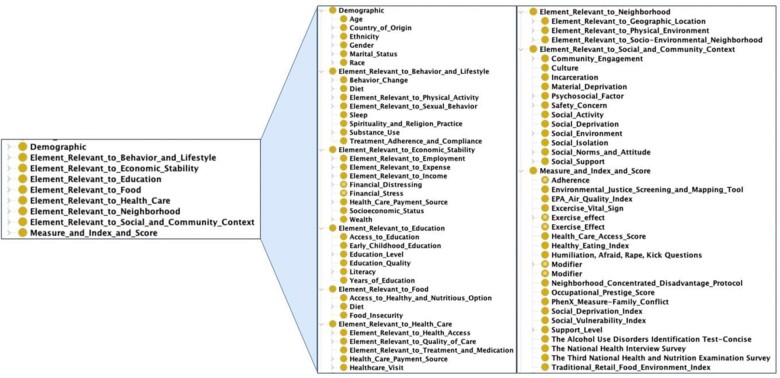

SDoH factors and related information were collected and defined as in OWL classes, resulting in a total of 708 classes in the SDoHO. There are 9 top-level classes that represent the main SDoH related factors. As shown in Figure 3, the 9 main top-level classes are “Element_Relevant_to_Behavior_and_Lifestyle,” “Demographic,” “Element_Relevant_to_Education,” “Element_Relevant_to_Social_and_Community_Context,” “Element_Relevant_to_Health_Care,” “Element_Relevant_to_Economic_Stability,” “Element_Relevant_to_Neighborhood,” “Element_Relevant_to_Food,” and “Measure_and_Index_and_Score.” Six of the 9 classes were drawn from Healthy People 2030 and LOINC.43 “Element_Relevant_to_Behavior_and_Lifestyle” was included after reviewing the SBDH concept.7 “Demographic” was added to represent the subject individual’s societal role.15,16 “Measure_and_Index_and_Score” was created to define measurement concepts associated with the other top-level classes. Under the “Measure_and_Index_and_Score,” there are 21 qualitative and quantitative measurements collected and linked to the relevant factors. Among the 21 measurements, 4 were self-defined to accommodate the measurements with flexibility, such as use of permissible values. Two terms “Exercise_Effect” and “Modifier” were adopted from the Physical Activity Ontology (PACO),21 and we expanded the “Modifier” class to measure behaviors other than physical activity. Fifteen are survey questions collected from various sources to measure SDoH factors, such as vital signs, smoking, air quality, and healthy food accessibility. To ensure standardization and interoperability while representing SDoH relations with versatility, we imported and inherently reused elements from some existing ontologies, including Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), Time event ontology (TEO), and PACO, to formally represent aspects of certain professions. We also defined a “Person” class to demonstrate how the defined classes and properties can be used to represent SDoH information for each individual. Class definitions are semantically defined appropriate classes, using OWL axioms. The current ontology includes 23 formally defined classes that can enable semantic inference and automatic classification.

Figure 3.

The 9 main categories in SDoHO and direct subclasses in Protégé.

Property

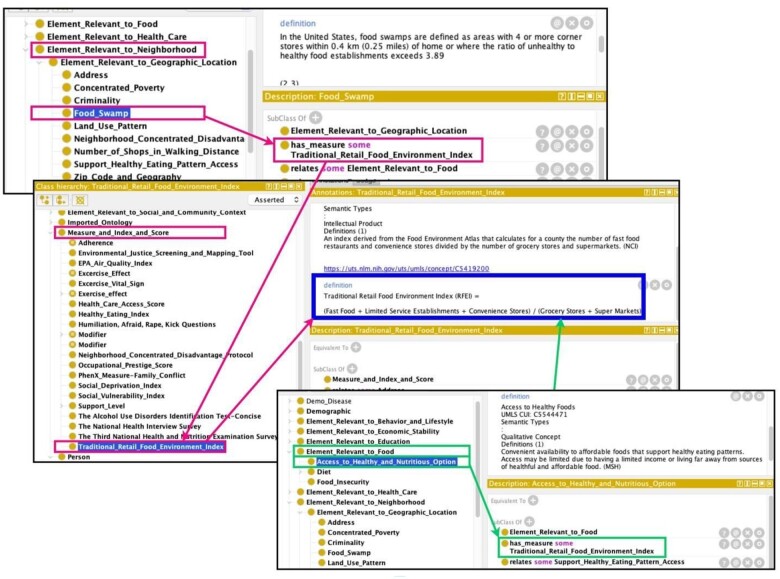

We defined 106 object properties, 20 data properties, and 31 annotation properties to represent relationships between SDoH factors and people/patients as well as among the factors. Of the 106 object properties, 24 were used to describe the relations between people/patients and SDoH factors. For example, for “Person” “has_race,” “Race” describes the relation of “Person” and “Race.” For the interrelationships among factors, the main object property is “relates”; for example, “Occupation” “relates” some “Exposure_to_Carcinogen_and_Pathogen” was used to show the relationship between occupations and possible work-related environmental exposure. Another major object property between SDoH factors is “has_measure,” which links the SDoH factors to the relevant measurements under the “Measure_and_Index_and_Score” class. This object property was designed to retrieve the quantitative and qualitative information relevant to the corresponding factor. For instance, the SDoH factor “Food_Swamp” “has_measure” with some “Traditional_Retail_Food_Environment_Index” (RFEI), which measures the ratio of healthy and unhealthy food options in a range of geographical radius (Figure 4). With the information on the address of the neighborhood, this ontology can potentially facilitate the RFEI score calculation and further evaluate patients’ accessibility to healthy food options. Further, the object property of “has_time_flag,” which can represent time properties to the chronicle state of a subject or event. With richly defined object properties, we can also express n-ary relationships when more information is added to the statement triple. Our primary solution to the n-ary relationship is to define an additional attribute that describes the relation.44 To semantically represent the patient’s smoking history in the past, smoking cessation, and current nonsmoking status, new attributes were inserted to describe the complex n-ary semantic relations (please see the Use Case section in Supplementary File).

Figure 4.

Ontological representation of how geographical information can help with accessibility of healthy food options in Protégé. Example of how to use the “has_measure” object property to represent measures: The concept “Traditional_Retail_Food_Environment_Index” (RFEI) was adopted from the PhenX questionnaire, and the equation involves the availability of healthy food in the target neighborhood. The concept of “Food_Swamp” is defined as “areas with 4 or more corner stores within 0.4 km (0.25 miles) of home or where the ratio of unhealthy to healthy food establishments exceeds 3.89” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.49,50 In this measurement relationship, the score of the RFEI indicates the state of “Food_Swamp” of the neighborhood. Like “Food_Swamp,” “Address” and “Zip_Code_and_Geography” are also subdomains of “Element_Relevant_to_Neighborhood” and “Element_Relevant_to_Geographic_Location.” In addition, the RFEI score is the measure of the concept “Access_to_Healthy_and_Nutritious_Options.”

In addition to the built-in data property, we defined and inherently imported 19 data properties to represent the relationship between concepts and data. We defined “has_number” in considering future applications and measurements. The use case example in Supplementary Figure S1A provides a demonstration of the data property “has_number,” which is defined as the numeric values of any measure. Further, 13 data properties imported from TEO and PACO assisted with classifying the time-related relation between concepts and data, such as “TEO: hasAgeValue,” as shown in Supplementary Figure S1B. In the example, this data property recorded and normalized the textual age into a float.

Further, we utilized annotation properties in the proposed ontology. In addition to the built-in annotation properties with predefined semantics in OWL and Resource Description Framework Schema (RDFS) from Protégé, there were 4 relevant ones adopted from TEO and 10 imported from SKOS. Annotation properties from SKOS assisted in constructing the ontology’s basic needs. With the utilization of object properties, data properties, and annotation properties, the proposed ontology has comprehensively standardized the representation of features and relationships of the classes.

Evaluation results

Semantic evaluation

We evaluated the ontology’s semantic meaning in 3 rounds with the Hootation tool.39 During the first round of evaluation, the 3 experts reached a rational agreement, that is, agreed by all 3 evaluators that the statement was rational, in 53% of cases and 84% in the second round. A final rational agreement in 97% of cases was achieved after 3 rounds of evaluation, with an interevaluator agreement of 0.923, which meant 92.3% of statements reached a consensus by 3 experts despite its rationale. There were 9 relations that did not achieve rational agreement and could not be further improved. Of the 9, 7 were subclass relations, and 2 were data property relations. Four out of the 7 were related to the definition of diet and its subclasses. Due to various definitions in the UMLS and disagreement on choosing the best description, an agreement was not achieved. Three disagreed on their subclass hierarchical structure, and the 2 object property relations disagreements were on the level of restriction type. As to the disagreement among evaluators and limited sources for further improvement, the rational agreement score was pushed to 0.967. For the ones that did not reach rational agreement, we kept those that the majority of evaluators voted on in the latest version of the proposed ontology.

Coverage evaluation

We evaluated the coverage of SDoHO by utilizing clinical notes and a survey questionnaire. As a result, the 3 text sources could be mapped to 7 top-level SDoHO domains and 30 concept-level factors. The HCPC clinical notes, Mayo Chronic Pain cohort, and AoU survey were mapped to 14, 15, and 13 classes from the ontology, respectively (distribution shown in Supplementary Table S2). Each text source aimed at different health concerns so that the ontology coverage varied for the real-world reflection.

Clinical note coverage.

Coverage of the ontology was measured with psychiatric patient clinical notes. The notes covered mainly 6 areas: “Demographic,” “Element_Relevant_to_Behavior_and_Lifestyle,” “Element_Relevant_to_Economic_Stability,” “Element_Relevant_to_Education,” “Element_Relevant_to_Neighborhood,” and “Element_Relevant_to_Social_and_Community_Context.” Within the 300 notes, there were 414 SDoH factors mapped to a total of 14 SDoH classes. Among the 14 mapped concepts, the top 3 factors were “Education_Level,” “Living_Status,” and “Adverse_Childhood_Experience.” As shown in Table 2, the proposed ontology is applicable to fully cover SDoH domains, concepts, and the downstream object properties and measurements in the clinical notes context.

Table 2.

Coverage evaluation results of SDoHO with 3 textual sources

| Ontology level | Matched in psychiatry notes (%) | Matched in chronic pain notes (%) | Matched items in AoU SDoH survey (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain level | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Main concept level | 100 | 100 | NA |

| Value/measurement level | 100 | 66.67 | 44.44 |

Another set of clinical notes was the chronic pain cohort dataset, which covers the same 6 domains but varies in the main concept level from the psychological assessment set (distribution shown in Supplementary Table S2). The top 3 identified SDoH factors in the chronic pain set were “Substance_Abuse,” “Employment_Status,” and “Marital_Status.” All of the SDoH domains and main concepts from the 507 chronic pain notes were covered by our proposed ontology. In the value and measurement perspective, SDoHO reached 66.67% in the coverage, as summarized in Table 2. The yes-or-no type of measurements or values is fully covered by the ontology, and the negative answers can be recorded by a negation assertion, such as “patient” (negative object property assertion) (“has_insurance” “insurance”). The proposed ontology also covers some categorical measurements and values. For example, we have categorical permissible values, “good_adherence” and “poor_adherence,” for the measure “Adherence.” Thus, as shown in Table 2, the coverage of the proposed ontology in the chronic pain cohort reached 100%, 100%, and 66.67% for domain level, main concept level, and value/measurement level, respectively.

Survey coverage.

The coverage also was evaluated with the SDoH survey from the AoU research program, mainly at the domain level. All domains in the survey were mapped in the ontology by definition. Out of the 13 domains with 81 items in the survey, our ontology achieved 100% coverage at the survey’s domain level, as seen in Table 2. The main concept-level items were overly granular and specific and were out of the scope of this ontology. For example, under the “social cohesion” domain, one of its main concepts is asking about the values of the neighborhood, which is considered as out of the scope of this ontology because of its extensive granularity. In the measurement and value level, 44.44% of the detailed measurements from the survey were covered by the ontology. The classification of frequency measures was included in the ontology, as they allow to reflect the activity frequencies from the real world in a quantifiable means. The nonquantifiable measures, such as “very well” or open-question answers, are out of the scope of this ontology. In addition, the level of granularity differs, and some specific measures were not included after consideration. They can be added to enrich the ontology in the future stages. Therefore, the AoU survey is fully covered in the domain level but less than half at the measurements and values level.

DISCUSSION

Contributions

SDoHO aims to provide a formal and standard representation of the domain that fills in identified gaps and overcomes the heterogeneity in existing SDOH ontologies and terminologies. We extensively reused existing standards and vocabularies to facilitate interoperability between the ontology and surrounding resources. One goal of the SDoHO is to support multiple downstream applications. We created classes and properties that offer flexibility to be applied in different contexts, including supporting semantic reasoning and NLP. The current version of SDoHO represents meta-level core knowledge of the domain, which is not designed to be exhaustively populated at this initial stage. As our efforts accumulate on the enrichment, the ontology can grow and be expanded, leveraging automated informatics techniques. Thus, SDoHO can be a standard framework to address an urgent need.

In this paper, SDoHO introduces a comprehensive and formally defined collection of SDoH concepts, hierarchies, and relations that can be adopted by medical and public health settings to ensure data and semantic interoperability, and further address the applicability and scalability. Concepts defined and standardized by UMLS with the CUI and official websites maximally ensured unity and future interoperability. The measurement among concepts and linkage to relevant measuring items enables our proposed ontology to be applicable to clinical, public health, and biomedical informatics perspectives. For data presentation, the ontology will ensure semantic interoperability and data FAIRness (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable). For survey purposes, it will enable standard representation of the input data. In addition, the alignment to clinical notes and the AoU SDoH survey extends its practicability. By taking into consideration data storage scenarios, SDoHO was designed to be pragmatic. We use identification numbers for the extendable nodes to differentiate the following instances. This design exists in our ontology to differentiate each specific event because they can be followed by further details, such as smoking intensities or frequencies. Gender or race (see Supplementary Figure S2), however, cannot be further explained or differentiated, so they were not followed by identification numbers. Thus, our proposed ontology was built with a concrete framework design, a scalable structure, and flexible functions. We also contemplated the potential downstream applications. In leveraging SDoHO with informatics, 2 possible downstream use cases were abstracted, as seen in Figure 1: NLP, to improve the accuracy in identification of SDoH factors from unstructured text and empowering of the computer’s understanding of the SDoH factors measurements to assist with clinical decision support.

Limitations and future efforts

In its current stage, the ontology has several limitations. First, we defined the relations based on current sources, which lack proper hierarchies and relations; therefore, the current version of the ontology does not include all relevant relationships. We plan to leverage the literature as the main source for relationship extension in the future. Second, the current way to calculate a measure is annotated in natural language with an equation (as illustrated in Figure 4, center blue box), and queries are not developed in the current version. We thus will utilize Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL) to automate the calculation query function. For instance, we can link the relevant database and automate the calculation of the healthy food accessibility based on a geographic location input, and calculate the output of the RFEI score. Consequently, our ontology lacks instances and value sets. As such, we will evaluate existing ontologies and published guidelines to enrich the proposed ontology. In order to maintain its comprehensiveness, we will also cover persons with disabilities20 and persons with chronic diseases.45–47 Currently, SDoHO is aligned with standard terminologies, such as UMLS,48 LOINC,43 and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT).48 For specific domains that cannot be aligned, our current top-down approach with SDoHO can be leveraged as the backbone framework and utilize a bottom-up approach for expansion to align SDoHO with other ontologies, such as those presented in Supplementary Table S1. Further, we plan to align with Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) to enable interoperability with other ontologies. Finally, as the evaluation results indicated, SDoH information is embedded in text. There is great potential to use the constructed ontology in combination with NLP to generate large data sets of tagged SDoH concepts occurring in real-world data and further transform the unstructured information to structured. Therefore, our next step is to increase the interoperability of the ontology.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we developed an SDoH Ontology, for comprehensively and hierarchically representing SDoH factors semantically from heterogeneous data sources. We evaluated the proposed ontology from semantic perspective with 3 domain experts; the coverage evaluation was also performed on real-world data from 3 sources involving 2 types of text. Both evaluation perspectives achieved satisfactory results. In addition, we provided an overview of several current semantic frameworks in the research field in the Supplementary Material. Furthermore, we demonstrated the future applicability of the proposed ontology by 2 simulated use cases in the Supplementary Material. Thus, SDoHO has well-designed hierarchies, practical objective properties, and versatile functionalities, and the comprehensive semantic and coverage evaluation achieved promising performance compared to the existing ontologies relevant to SDoH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) program and AoU Research Program for their work on Social Determinant of Health topics. We thank Johnathan Jia for comments on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yifang Dang, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Fang Li, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Xinyue Hu, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Vipina K Keloth, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA; Section of Biomedical Informatics and Data Science, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Meng Zhang, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Sunyang Fu, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Artificial Intelligence and Informatics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Muhammad F Amith, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Information Science, University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, USA; Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, School of Population Health, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA.

J Wilfred Fan, Department of Artificial Intelligence and Informatics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Jingcheng Du, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Evan Yu, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Hongfang Liu, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA; Department of Artificial Intelligence and Informatics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

Xiaoqian Jiang, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Hua Xu, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA; Section of Biomedical Informatics and Data Science, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Cui Tao, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging (HHS-NIH) grant number 1RF1AG072799, National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant number 1RM1HG011558, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant number 1U24AI171008.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CT, YD, and FL conceived and designed the work. YD and FL constructed the ontology and drafted the manuscript. YD, VKK, XH, SF, and MZ conducted the data annotation and ontology evaluation. JD and JWF provided technical support. YD, FL, VKK, ATM, and EY designed the use cases. CT, HX, HL, and XJ supervised the research and critically revised the manuscript. All the authors gave final approval of the completed manuscript version.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The SDoHO is available at https://sbmi.uth.edu/bsdi/files/SDoHO.zip?language_id=1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health 2011; 32: 381–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Social Determinants of Health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed December 7, 2021.

- 3. Patra BG, Sharma MM, Vekaria V, et al. Extracting social determinants of health from electronic health records using natural language processing: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021; 28 (12): 2716–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- 5. Chapman-Novakofski K. Social determinants of health themed issue. J Nutr Educ Behav 2022; 54 (2): 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wild CP. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int J Epidemiol 2012; 41 (1): 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Socio-Behavioral Determinants of Health (SBDH) Data Catalog. https://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/programs_resources/sbdh/. Accessed February 7, 2022.

- 8. Zhang H, Hu H, Diller M, et al. Semantic standards of external exposome data. Environ Res 2021; 197: 111185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arons A, DeSilvey S, Fichtenberg C, et al. Documenting social determinants of health-related clinical activities using standardized medical vocabularies. JAMIA Open 2019; 2 (1): 81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watkins M, Viernes B, Nguyen V, et al. Translating social determinants of health into standardized clinical entities. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020; 270: 474–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Resnick MP, Montella D, Mccray W, et al. The gaps in the terminological representation of the ACORN social determinants of health survey. https://icbo-conference.github.io/icbo2022/papers/ICBO-2022_paper_0492.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2022.

- 12. Gruber TR. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowl Acquis 1993; 5 (2): 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee Y-C, Eastman CM, Solihin W. An ontology-based approach for developing data exchange requirements and model views of building information modeling. Adv Eng Informatics 2016; 30 (3): 354–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoerndorf R. ICBO-2022: International Conference on Biomedical Ontology. 2022. https://icbo-conference.github.io/icbo2022/icbo-schedule/. Accessed November 18, 2022.

- 15. Hogan WR, Garimalla S, Tariq SA. Representing the reality underlying demographic data. In: International Conference on Biomedical Ontology. Unknown; 2011. http://dx.doi.org/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 16. Hicks A, Hanna J, Welch D, et al. The ontology of medically related social entities: recent developments. J Biomed Semantics 2016; 7: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melton GB, Manaktala S, Sarkar IN, et al. Social and behavioral history information in public health datasets. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2012; 2012: 625–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phan N, Dou D, Wang H, et al. Ontology-based deep learning for human behavior prediction with explanations in health social networks. Inf Sci (N Y) 2017; 384: 298–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. SMASH Ontology. https://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/SMASH. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- 20. Gharebaghi A, Mostafavi M-A, Edwards G, et al. Integration of the social environment in a mobility ontology for people with motor disabilities. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2018; 13 (6): 540–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim H, Mentzer J, Taira R. Developing a physical activity ontology to support the interoperability of physical activity data. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21 (4): e12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rousseau JF, Oliveira E, Tierney WM, et al. Methods for development and application of data standards in an ontology-driven information model for measuring, managing, and computing social determinants of health for individuals, households, and communities evaluated through an example of asthma. J Biomed Inform 2022; 136: 104241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. OWL – Semantic Web Standards. https://www.w3.org/OWL/. Accessed October 14, 2022.

- 24. Jani A, Liyanage H, Okusi C, et al. Using an ontology to facilitate more accurate coding of social prescriptions addressing social determinants of health: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22 (12): e23721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lybarger K, Ostendorf M, Yetisgen M. Annotating social determinants of health using active learning, and characterizing determinants using neural event extraction. J Biomed Inform 2021; 113: 103631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bompelli A, Wang Y, Wan R, et al. Social and behavioral determinants of health in the era of artificial intelligence with electronic health records: a scoping review. Health Data Sci 2021; 2021: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Social Determinants of Health. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- 28. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 29. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. KFF. 2018. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 30. Defining the Social Determinants of Health – RHIhub Toolkit. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/sdoh/1/definition. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 31. Social Determinants of Health. HIMSS. 2021. https://www.himss.org/resources/social-determinants-health. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 32. Catalyst. Social determinants of health (SDOH). Catalyst Carryover 2017; 3 (6). doi: 10.1056/CAT.17.0312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. What Are the Social Determinants of Health? National Academy of Medicine. 2018. https://nam.edu/programs/culture-of-health/young-leaders-visualize-health-equity/what-are-the-social-determinants-of-health/. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 34. Social Determinants of Health. RWJF. https://www.rwjf.org/en/our-focus-areas/topics/social-determinants-of-health.html. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 35. Social Determinants of Health. American Hospital Association. https://www.aha.org/social-determinants-health/populationcommunity-health/community-partnerships. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 36. Uschold M, Gruninger M. Ontologies: principles, methods and applications. Knowl Eng Rev 1996; 11 (2): 93–136. [Google Scholar]

- 37. What Is an Ontology and Why We Need It. http://www.ksl.stanford.edu/people/dlm/papers/ontology101/ontology101-noy-mcguinness.html. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- 38. PhenX Toolkit: Collections. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/collections/view/6. Accessed January 18, 2022.

- 39. Amith M, Manion FJ, Harris MR, et al. Expressing biomedical ontologies in natural language for expert evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 245: 838–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carlson LA, Jeffery MM, Fu S, et al. Characterizing chronic pain episodes in clinical text at two health care systems: comprehensive annotation and corpus analysis. JMIR Med Inform 2020; 8 (11): e18659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tian TY, Zlateva I, Anderson DR. Using electronic health records data to identify patients with chronic pain in a primary care setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20 (e2): e275-80–e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. All of Us Research Program. National Institutes of Health (NIH) – All of Us. 2020. https://allofus.nih.gov/. Accessed March 3, 2022.

- 43. Social Determinants of Health. LOINC. https://loinc.org/sdh/. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 44. Defining N-ary Relations on the Semantic Web. https://www.w3.org/TR/swbp-n-aryRelations/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 45. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer–analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000; 343 (2): 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Willett WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science 2002; 296 (5568): 695–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106 (23): 9362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. UMLS Metathesaurus Browser. https://uts.nlm.nih.gov/uts/umls/home. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 49. Cooksey-Stowers K, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14 (11): 1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hager ER, Cockerham A, O’Reilly N, et al. Food swamps and food deserts in Baltimore City, MD, USA: associations with dietary behaviours among urban adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20 (14): 2598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The SDoHO is available at https://sbmi.uth.edu/bsdi/files/SDoHO.zip?language_id=1.