Highlights

-

•

German-Polish bilingual, interprofessional tandem-simulation training is feasible.

-

•

Emergency medicine professionals perform CPR together overcoming language barriers.

-

•

In simulated scenarios, teams demonstrate high adherence to European guidelines.

-

•

Yet, bilingual setting reduces leadership skills and overall team performance.

Keywords: Cross-border, Simulation training, Interprofessional, Resuscitation training, Advanced life support, Bilingual

Abstract

Aim of study

This study aims to investigate feasibility and quality of a bilingual cardiopulmonary resuscitation training with interprofessional emergency teams from Germany and Poland.

Methods

As part of a cross-border European Territorial Cooperation (Interreg-VA) funded project a combined communication and simulation training was organised. Teams of German and Polish emergency medicine personnel jointly practised resuscitation. The course was held in both languages with consecutive translation.

Quality of chest compression was assessed using a simulator with feedback application. Learning objectives (quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, adherence to guidelines, closed loop communication), and team performance were assessed by an external observer. Coopeŕs Team Emergency Assessment Measure questionnaire was used.

Results

Twenty-one scenarios with 17 participants were analysed. In all scenarios, defibrillation and medication were delivered with correct dosage and at the right time. Mean fraction of correct hand position was 85.7% ± 25.7 [95%-CI 74.0; 97.4], mean fraction of compression depth 75.1% ± 21.0 [95%-CI 65.6; 84.7], compression rate 117.7 min−1 ± 7.1 [95%-CI 114.4; 120.9], and chest compression fraction 83.3% ± 3.8 [95%-CI 81.6; 85.0].

Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation was rated as “fair” to “good”, adherence to guidelines as “good”, and closed loop communication as “fair”. Bilingual teams demonstrated good situational awareness, but lack of leadership and suboptimal overall team performance.

Conclusion

Bilingual and interprofessional cross-border resuscitation training in German and Polish tandem teams is feasible. It does not affect quality of technical skills such as high-quality chest compression but does affect performance of non-technical skills (e.g. closed loop communication and leadership).

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) requires prompt and high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 European guidelines emphasize the importance of high-quality chest compressions and early defibrillation to increase likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and survival to hospital discharge.2

Emergency medical services (EMS) strive to establish systems with shortest possible response times.3 EMS located in national border regions are often challenged with increased time to reach the patient and longer transport times to hospitals. However, national borders should not impede patient care.4 Cross-border assistance and collaboration of EMS and hospitals can facilitate timely and qualified care.5 Promoting cross-border collaboration, fostering intercultural awareness, and enhancing healthcare professionalś neighbour-language skill can contribute to improved quality and efficiency of patient care in border regions.6, 7

In neighbouring countries with different languages (such as Germany and Poland), joint bilingual training may help to foster cross-border collaboration. Simulation training is an approved method in medical education providing a safe environment to practice time-sensitive skills with low tolerance for error, while facilitating structured feedback.8, 9 Simulation-based education of resuscitation facilitates contextualised learning and is highly recommended by the 2021 European Resuscitation Council (ERC) “Education in Resuscitation” chapter.10 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate, that cardiac arrest patients treated by team members, who previously participated in a certified simulation course, have a higher likelihood of survival.11, 12

Little is known about the impact of cross-border and bilingual collaboration on quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among emergency medicine professionals.13

As the Polish and German resuscitation guidelines are both translations of the ERC guidelines, it can be assumed that German and Polish teams manage cardiac arrest patients similarly.14, 15 However, the question arises, if EMS personnel, who does not speak the neighbouring language, can be trained to perform resuscitation effectively alongside members of the neighbouring team.

Material and methods

This study is a feasibility analysis of a bilingual and interprofessional resuscitation training with language novices. It was part of a combined medical simulation and communication training, which took place from April until November 2022 at the simulation facility of the Polish Ground Ambulance Services in Misdroy, Poland.

The simulation training was organised within the scope of a project funded by the cross-border European Territorial Cooperation (Interreg A) in the period V from 2014 to 2020 in the NUTSIII regions Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg and Pomerania (Project GeKoM, INT197, Interreg VA).

Course structure

The five-day course was organised and let by a binational, interprofessional faculty consisting of EMS personal, physicians, a linguist, and a language teacher. The course was held in Polish and German with consecutive translations. At all times a bilingual faculty member was present who could translate, if needed. During the first three course days participants acquired the necessary communicational skills. In bilingual tandem groups of two they learned words and phrases needed to provide resuscitation care.16 Phrases taught were in the context of recognising cardiac arrest, performing chest compressions, delivering safe defibrillation, administering drugs and detecting return of spontaneous circulation. During a two-hour session the group went through the Polish and German advanced life support (ALS) algorithms, and discussed medical and intercultural differences.15 Furthermore, characteristics of high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation were recapitulated. This session was facilitated by certified ERC ALS instructors and followed by a demonstration of a resuscitation scenario by the joint Polish and German faculty.

The last two course days consisted of simulation trainings in binational groups of two. In each scenario participants had to recognise and treat a cardiac arrest. Language was appointed by the instructors so that at least one participant had to communicate in foreign language. Scenario briefing and debriefing were performed in both languages. These scenarios were retrospectively analysed, and the results will be presented below.

Study participants

Employees of German and Polish emergency medical services, emergency medical departments and medical students were recruited to take part in the training. Participation was voluntarily and free of charge. The course was held twice and up to 5 Polish and 5 German participants could take part per course.

Learning objectives

The following learning objectives were defined: (1) high quality chest compression, (2) adherence to 2021 ERC ALS algorithm, and (3) use of closed-loop communication. Those three learning objectives were set, because a successful resuscitation requires CPR skills as well as communication and collaboration with fellow rescuers.17

Learning objectives were assessed in real time during the simulation by an independent observer (CH). Each learning objective was evaluated on a symmetrical 5-point Likert scale (from very poor [0] to excellent [4]) and was declared as achieved if a level of 4 or 5 was reached. To evaluate high-quality chest compression, the following aspects were factored in: chest compression rate, depth, hand position, and chest compression fraction. Adherence to ALS guidelines took into account timing and dosage of drugs and timing and safety of defibrillation. Rating of closed loop was based on number of times this communication technique was used during the scenario.

Description of resuscitation scenarios

Before each simulation, instructors randomly drew one out of 14 scenarios, which were written in both languages (see Supplemental file 1 for an example). Each scenario was scripted for an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest as well as a cardiac arrest occurring at the emergency department. A bilingual faculty member was available to act as scripted scenario life saver to take on a predefined role in the scenario and (indirectly) provide assistance, if necessary.18

During the scenarios heart rhythm could change based on instructor’s decision. Chest compression and bag-mask-ventilation were performed with a 30:2 ratio. Participants could choose to secure the airway at their own discretion. Participants were provided with a simulated manual defibrillator (Zoll X®, Zoll Medical Corporation, Chelmsford, Massachusetts, US). Each scenario was stopped, when ROSC was detected.

During simulation, a Resusci Anne QCPR® with corresponding feedback application QCPR Training® (Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway) was used. Feedback was only used for retrospective analysis and not shown to participants during simulation.

Laerdal’s QCPR® is based on a non-binary scoring algorithm to assess chest compression quality. The resulting scores of each parameter (e.g. rate, depth and chest compression fraction) do not present the relative frequency of adequate (within the threshold) manoeuvres but correlation with the deviation to defined thresholds according to ERC guidelines.15

The scenarios and subsequent debriefings were led by two certified ERC ALS instructors (MLR and BM).

During each scenario the ‘Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM)’ questionnaire was used by the independent observer (CH) to assess non-technical skills. This 11-item score has been validated for resuscitation scenarios.19

Statistical analysis

Due to the nature of a feasibility study no sample size calculation was performed. Data is presented using frequency distribution (percentage) and central tendencies with variability (mean and standard deviation). Statistical analysis has been carried out using SPSS 28 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA).

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles decreed by the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The institutional ethics committee of the University Medicine Greifswald reviewed and approved the protocol and informed consent document (BB 165/21). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Results

During two 5-day-courses 27 scenarios with 17 German and Polish participants were conducted (Table 1). Due to missing data, 6 scenarios had to be excluded from further analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n = 17) as stated by the participants.

| Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Native language | German | 8 |

| Polish | 9 | |

| Sex | Female | 3 |

| Male | 14 | |

| Profession | Paramedic | 9 |

| Emergency department physician | 2 | |

| Medical student | 6 | |

| Last certified Advanced Life Support Course | Course instructor | 1 |

| Within two years prior to study | 0 | |

| More than two years prior to study | 2 | |

| Never | 14 | |

| Regular uncertified Basic or Advanced Life Support Training | Yes | 11 |

| No | 6 | |

| Ever attended non-technical skills training | Yes | 2 |

| No | 15 | |

| Necessary expertise to perform bilingual resuscitation | Yes | 2 |

| No | 15 | |

Out of the 21 scenarios included, 7 were conducted in Polish and 14 in German. To facilitate communication within mixed teams a bilingual life saver was necessary in 2 out of 21 scenarios (9.5%).

All participants chose an OHCA scenario, of which 11 scenarios (52%) were set in a public space. The initial rhythm was asystole in 6 cases (29%), pulseless electrical activity in 2 cases (9%), ventricular fibrillation in 8 cases (38%), and pulseless ventricular tachycardia in 5 cases (24%). Manual defibrillation was performed without safety concerns. In all cases with a shockable rhythm a shock was delivered. During all scenarios, the only drugs administered were adrenaline and amiodarone with correct dosage.

Quality of chest compression of the 21 scenarios is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of chest compression (assessed with feedback application QCPR Training® [Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway]) (n = 21 scenarios).

| Parameters | Mean ± SD [95%-CI] |

|---|---|

| Mean fraction of correct hand position [percent] | 85.7 ± 25.7 [74.0; 97.4] |

| Mean fraction of compression depth 5–6 cm [percent] | 75.1 ± 21.0 [65.6; 84.7] |

| Mean compression rate [number of compressions per minute] | 117.7 ± 7.1 [114.4; 120.9] |

| Mean chest compression fraction [percent of time] | 83.3 ± 3.8 [81.6; 85.0] |

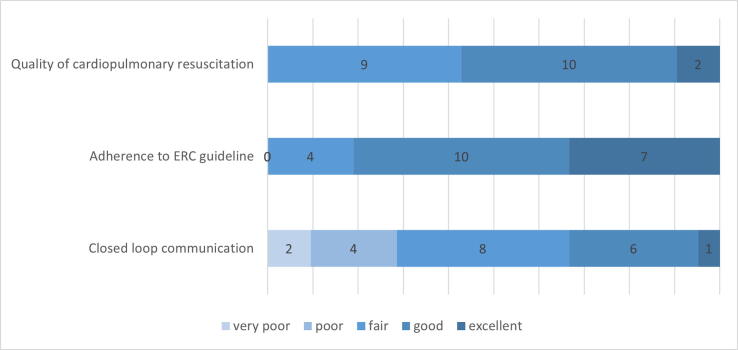

The learning objective quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation was rated as “fair” to “good” (2.7 ± 0.7), adherence to ERC guideline as “good” (3.1 ± 0.7) and closed loop communication as “fair” (2.0 ± 1.0). Out of the 21 scenarios, the learning objective high quality chest compression was achieved (Likert scale level 4 or 5) in 12 cases (57%), adherence to ERC guideline in 17 cases (81%), and closed loop communication in 7 cases (33%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Assessment of the three learning objectives “quality of chest compression”, “adherence to ERC guideline”, and “closed-loop communication” measured on a 5-point-Likert scale. Data is presented as absolute numbers (n = 21 scenarios).

Assessment of non-technical skills demonstrated that bilingual resuscitation teams often adapted to changing situations (item 7 of the TEAM questionnaire). Additionally, the team often monitored and reassessed the situation (item 8). The lowest scored category was leadership with the items direction and global perspective (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of ‘Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM)’ questionnaire presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) (n = 21 scenarios). 11 items could be rated from 0 (never/hardly ever) to 4 (always/nearly always). Global rating ranged from 1 to 10.

| Categories and items | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership | ||

| 1 | Direction | 2.4 ± 0.9 |

| 2 | Global Perspective | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| Teamwork | ||

| 3 | Communication | 2.9 ± 0.6 |

| 4 | Co-Operation and Co-Ordination | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| 5 | Team composure and control | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

| 6 | Team morale | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| 7 | Adaptability | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| 8 | Situation Awareness (Perception) | 3.4 ± 0.9 |

| 9 | Situation Awareness (Projection) | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

| Task Management | ||

| 10 | Prioritisation | 3.3 ± 0.6 |

| 11 | Clinical Standards | 3.0 ± 0.8 |

| Global Rating (1–10) | 6.7 ± 1.0 | |

| TEAM score overall | 32.1 ± 3.4 | |

Discussion

This study focused on quality of chest compression (as key component of high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation), guideline-adherence and on communication during bilingual resuscitation training. We demonstrated the feasibility of cross-border resuscitation training in bilingual tandem groups. Furthermore, our results show that language-barriers due to bilingual conversation affect team performance. However, healthcare professionalś technical skills are less affected by language barriers.

To assess quality of chest compression two methods were combined: the scoring algorithm of the simulation manikin as well as rating by an external observer. This approach was chosen to minimise measurement errors. Software-based devices provide objective feedback.20 However, as external instructors can also factor in other aspects of advanced life support, electronic feedback may be less effective in complex scenarios.21

The software-based algorithm showed a mean compression rate within the threshold of 100–120 compressions per minute with only small deviation. However, consistency of adequate compression depth and correct hand position was lower.

Our findings are consistent with the results of Cheng et al. who compared estimated and measured quality of chest compression in a simulation study involving a similar population of healthcare professionals.22 Healthcare professionals receiving monolingual CPR training provided adequate compression depth in about 75%, whereas chest compression fraction was slightly higher (approx. 89% compared to 86% in our study). In a meta-analysis, depth and rate of chest compression were significantly associated with ROSC and survival to hospital discharge.23 Additionally, a higher chest compression fraction appears to be associated with survival, particularly in cases with an initial shockable rhythm.23, 24, 25, 26

Overall, the quality of chest compression, as rated by the external observer, was deemed as “good” or “excellent” in 57% of scenarios. This aligns with the software-based measurements.

Only 11 out of 17 participants had attended uncertified or certified Basic Life Support (BLS) or ALS courses prior to this training. Despite this, their high adherence to ERC guidelines indicates that participants possessed fundamental knowledge, shared a common mental model, and were able to perform resuscitation even in a bilingual team.27

However, overall team performance was rated below average. According to Cooper et al., an overall TEAM score of 32 and a global rating of 7 indicate poor team performance.19 Effective communication is crucial for optimal CPR performance. Accuracy of team leader communication is related to no-flow time; and teamwork skills are associated with adherence to guidelines.28 Studies demonstrated that quality of leadership and teamwork influence performance and clinical outcome in acute care, whereas quality of chest compressions remains unaffected.29, 30, 31 Closed-loop communication and use of terms known by all team members contribute to effective communication.28 Some participants were not familiar with the concept of closed-loop communication before participating in the training as only two participants had ever attended a non-technical skill training before. This may explain why closed-loop communication was performed at a lower level compared to the other two learning objectives (quality of chest compression and adherence to ERC guidelines) (Fig. 1).

In summary, psychomotor skills and situational awareness were not affected, whereas the quality of team performance and leadership was lower compared to monolingual teams. These findings suggest that cross-border collaborative resuscitation care in a bilingual team based on shared guidelines is possible. At the same time, the results are not surprising, as both leadership and teamwork require coordination, cooperation and especially communication.32

According to the cognitive load theory, stress and difficulty of task contribute to intrinsic cognitive load.33 An imbalance between individual resources (e.g. communicative skills, knowledge or positive emotions) and the complexity and challenges inherent to resuscitation care may result in decreased performance.34 Participants anticipated the need to acquire additional skills to perform cross-border bilingual resuscitation prior to the training.

In addition to the challenges typically encountered in monolingual ALS training, participants in this bilingual simulation faced further difficulties: (1) Communication barriers due to different language proficiency levels in German and Polish; (2) The need to address various aspects of cross-border collaboration simultaneously; and (3) Interprofessional teams consisting of physicians, EMS personal and students with country-specific competencies and responsibilities.

These factors may have contributed to the performance gap in leadership skills and teamwork observed in our study compared to monolingual teams’ results.

Limitation

Our study has several limitations. As the evaluated resuscitation training was designed as a feasibility study focusing on realisation of the training, quantitative baseline data comparing e.g. bilingual resuscitation or non-technical skills is lacking. However, information regarding participants' prior knowledge in resuscitation, communication, and non-technical skills can be regarded as a descriptive assessment of the initial conditions.

According to our chosen study design, results were obtained in a simulation environment. Results may vary significantly in ad-hoc formed teams. Cross-border teams are likely to consist of unfamiliar team members. Participants took part voluntarily, therefore, a selection bias cannot be excluded. Different levels of resuscitation experience among participants (medical students, paramedics, and emergency medical physicians) were not assessed. Sex of our study population is not distributed equally. However, it is in concordance with the distribution among emergency healthcare professionals, especially in prehospital EMS.35 In this small-size study, we focused on cross-border team collaboration across the German and Polish border. Resuscitation training in other border regions and thus, other languages or in mutually intelligible languages, may yield different results. Additionally, varying familiarity with the other language is likely to influence the quality of communication.

Studies show that repetition of resuscitation training can improve teamwork performance.36 As the resuscitation training was embedded in a multi-module cross-border communication and simulation training, we were unable to investigate effect of repetitive scenario simulation training on individual chest compression and team performance. Improvement and retention of skills remain unknown.

Conclusion

We were able to show that bilingual cross-border resuscitation training in mixed German and Polish tandem teams is feasible. Leadership skills, team performance and closed-loop communication were negatively affected, whereas quality of chest compression, adherence to ERC guidelines as well as situational awareness remained unaffected. Further research on design and implementation of cross-border bilingual resuscitation training, focusing on more complex tasks, leadership and overall team performance, is highly recommended.

Funding

The project was funded by the European Commission by means of the European Fund for Regional Development (EFRD) [Program Interreg VA, INT197].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Marie-Luise Ruebsam: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Bibiana Metelmann: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation. Christian Hofmann: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Dorota Orsson: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Klaus Hahnenkamp: Funding acquisition, Supervision. Camilla Metelmann: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The simulation training we are reporting about was funded by the European Union with-in the scope of Interreg VA -Mecklenburg-Vorpommern/Brandenburg/Pomerania.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to thank Sonia Werner and Sebastian Antczak for their great, enthusiastic and professional support and assistance during simulation training. The authors are grateful to all participants.

Footnotes

Appendix A

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2023.100436.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Case vignette for a bilingual cross-border resuscitation simulation scenario.

References

- 1.Perkins G.D., Graesner J.-T., Semeraro F., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: executive summary. Resuscitation. 2021;161:1–60. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olasveengen T.M., Semeraro F., Ristagno G., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: basic life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gräsner J.-T., Herlitz J., Tjelmeland I.B.M., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: epidemiology of cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation. 2021;161:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleßa S. In: Sektoren- und grenzüberschreitende Gesundheitsversorgung: Risiken und Chancen. Zygmunt M., editor. Med. Wiss. Verl.-Ges; Berlin: 2013. Wirtschaftliche Grundlagen der grenzüberschreitenden Versorgung; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarzenberg T. Negotiating invisible lines: Cross-border emergency care in the rural north of Scandinavia. Nor Geogr Tidsskr – Norwegian J Geography. 2019;73:139–155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beuken J.A., Verstegen D.M.L., Dolmans D.H.J.M., et al. Going the extra mile - cross-border patient handover in a European border region: qualitative study of healthcare professionals' perspectives. BMJQual Safety. 2020;29:980–987. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertinato L., Canapero M. Successful cross-border education and training: the example of sanicademia–international training. Med Health. 2010:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuda Y., Bryson E.O., DeMaria S., et al. The utility of simulation in medical education: what is the evidence? Mount Sinai J Med New York. 2009;76:330–343. doi: 10.1002/msj.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang E.E., Quinones J., Fitch M.T., et al. Developing technical expertise in emergency medicine–the role of simulation in procedural skill acquisition. Acad Emerg Med Official J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1046–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greif R., Lockey A., Breckwoldt J., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: education for resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2021;161:388–407. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patocka C., Lockey A., Lauridsen K.G., Greif R. Impact of accredited advanced life support course participation on in-hospital cardiac arrest patient outcomes: a systematic review. Resusc Plus. 2023;14 doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2023.100389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockey A., Lin Y., Cheng A. Impact of adult advanced cardiac life support course participation on patient outcomes – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2018;129:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ucinski T., Dolata G., Hełminiak R., et al. Integrating cross-border emergency medicine systems: Securing future preclinical medical workforce for remote medical services. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2018;32:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, et al. Zaawansowane zabiegi resuscytacyjne u dorosłych (Advanced Life Support – ALS); 2021. https://www.prc.krakow.pl/wytyczne2021/rozdz5.pdf

- 15.Soar J., Böttiger B.W., Carli P., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:115–151. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orsson D. A glottodidactic model for German-Polish cross-border communication based on the example of rescue services in the region of Pomerania and Brandenburg. Polish in Germany. J Federal Assoc Polish Teachers. 2019;7 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nabecker S., Huwendiek S., Theiler L., Huber M., Petrowski K., Greif R. The effective group size for teaching cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills – a randomized controlled simulation trial. Resuscitation. 2021;165:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieckmann P., Lippert A., Glavin R., Rall M. When things do not go as expected: scenario life savers. Simul Healthcare J Soc Simul Healthcare. 2010;5:219–225. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181e77f74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper S., Cant R., Connell C., et al. Measuring teamwork performance: validity testing of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) with clinical resuscitation teams. Resuscitation. 2016;101:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortegiani A., Russotto V., Montalto F., et al. Use of a real-time training software (Laerdal QCPR®) compared to instructor-based feedback for high-quality chest compressions acquisition in secondary school students: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeung J., Meeks R., Edelson D., Gao F., Soar J., Perkins G.D. The use of CPR feedback/prompt devices during training and CPR performance: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2009;80:743–751. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng A., Overly F., Kessler D., et al. Perception of CPR quality: influence of CPR feedback, just-in-Time CPR training and provider role. Resuscitation. 2015;87:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talikowska M., Tohira H., Finn J. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality and patient survival outcome in cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2015;96:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christenson J., Andrusiek D., Everson-Stewart S., et al. Chest compression fraction determines survival in patients with out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120:1241–1247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaillancourt C., Everson-Stewart S., Christenson J., et al. The impact of increased chest compression fraction on return of spontaneous circulation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients not in ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1501–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uppiretla A.K., Gangalal G.M., Rao S., Don Bosco D., Shareef S.M., Sampath V. Effects of chest compression fraction on return of spontaneous circulation in patients with cardiac arrest; a brief report. Adv J Emerg Med. 2020;4 doi: 10.22114/ajem.v0i0.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler D.O., Peterson D.T., Bragg A., et al. Causes for pauses during simulated pediatric cardiac arrest. Pediatric Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Federation Pediatric Intens Crit Care Soc. 2017;18:e311–e317. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez Castelao E., Russo S.G., Riethmüller M., Boos M. Effects of team coordination during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review of the literature. J Crit Care. 2013;28:504–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schenarts P.J., Cohen K.C. The leadership vacuum in resuscitative medicine. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1216–1217. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d3abeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weidman E.K., Bell G., Walsh D., Small S., Edelson D.P. Assessing the impact of immersive simulation on clinical performance during actual in-hospital cardiac arrest with CPR-sensing technology: a randomized feasibility study. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1556–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeung J.H.Y., Ong G.J., Davies R.P., Gao F., Perkins G.D. Factors affecting team leadership skills and their relationship with quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2617–2621. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182591fda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wayne D.B., McGaghie W.C. Use of simulation-based medical education to improve patient care quality. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1455–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szulewski A., Howes D., van Merriënboer J.J.G., Sweller J. From theory to practice: the application of cognitive load theory to the practice of medicine. Acad Med. 2021;96:24–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Heer S., Cofie N., Gutiérrez G., Upagupta C., Szulewski A., Chaplin T. Shaken and stirred: emotional state, cognitive load, and performance of junior residents in simulated resuscitation. Can Med Educ J. 2021;12:24–33. doi: 10.36834/cmej.71760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DESTATIS. Zahl der Beschäftigten im Rettungsdienst von 2011 bis 2021 um 71 % gestiegen; 2023. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/Zahl-der-Woche/2023/PD23_06_p002.html

- 36.Mahramus T.L., Penoyer D.A., Waterval E.M.E., Sole M.L., Bowe E.M. Two hours of teamwork training improves teamwork in simulated cardiopulmonary arrest events. Clin Nurse Specialist CNS. 2016;30:284–291. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Case vignette for a bilingual cross-border resuscitation simulation scenario.