Abstract

Effective rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy (CP) requires intensive task-specific exercise but many in this population lack the motor capabilities to complete the desired training tasks. Providing robotic assistance is a potential solution yet the effects of this assistance are unclear. We combined a novel exoskeleton and exercise video game (exergame) to create a new rehabilitation paradigm for children with CP. We incorporated high density electroencephalography (EEG) to assess cortical activity. Movement to targets in the game was controlled by knee extension while standing. The distance between targets was the same with and without the exoskeleton to isolate the effect of robotic assistance. Our results show that children with CP maintain or increase knee extensor muscle activity during knee extension in the presence of synergistic robotic assistance. Our EEG findings also demonstrate that participants remained engaged in the exercise with robotic assistance. Interestingly we observed a developmental trajectory of sensorimotor mu rhythm in children with CP similar, though delayed, to those reported in typically developing children. While not the goal here, the exoskeleton significantly increased knee extension in 3/6 participants during use. Future work will focus on utilizing the exoskeleton to enhance volitional knee extension capability and in combination with EMG and EEG to study sensorimotor cortex response to progressive exercise in children with CP.

I. Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP), is the most common pediatric movement disorder [1]. CP is a heterogeneous diagnosis united by the hallmark symptom of a motor control deficit of varying severity across individuals. The treatment goal of physical therapy in CP is to improve motor function and promote independence. Yet, rehabilitation in this population is complicated by myriad comorbidities including sensory deficits, learning and attentional difficulties, and motivational challenges [2, 3]. Rehabilitation outcomes depend on both the amount and intensity of the therapy [4]. Further evidence demonstrates the importance of task-specific and goal-oriented training programs in children with CP, both of which have been shown to facilitate improved outcomes [5].

Technological advances in rehabilitation robotics have revolutionized delivery of physical therapy, particularly those targeting the lower extremity and locomotion. Robotic assisted gait training (RAGT) and body weight supported treadmill training (BWSTT) paradigms provide more efficient methods to deliver task-oriented practice compared to traditional approaches. Recently, some gait training systems have incorporated video game and virtual reality-based accompaniments to help improve motivation with some initial success reported [6]. Non-locomotive robotic interventions that include video game interfaces have also been developed [7, 8]. While pilot studies of treadmill-based and seated robotic interventions have reported improved function in children with CP [7, 9], randomized controlled trials of treadmill based training with [10] and without [11] robotic devices have shown equivalent outcomes to other therapies of equal intensity and dosage. Yet, if these robotic-based approaches can improve efficiency in delivering therapy and increase patient interest to maintain the program they may provide additional opportunity for benefits to accrue over an extended time frame [4].

Treadmill and other robotic-based approaches are limited mainly to clinical settings. The recent surge in wearable exoskeleton technology [12] provides the opportunity to increase dosage of training by expanding use outside the clinic. To date transfer of these technologies to children, in particular those with CP, has been limited. However, we recently designed and tested a prototype robotic exoskeleton specifically for children and adolescents with crouch gait from spastic diplegic CP [13]. The assistive device was well tolerated and demonstrated the ability to significantly reduce crouch (knee flexion) during use [14]. Deployment of this or similar devices outside of the laboratory provides the opportunity to greatly increase physical activity generally, and the dosage of gait training specifically, both of which could lead to enhanced mobility and independence.

Given recent studies demonstrating equivalence of RAGT and BWSTT to equal intensity alternatives, there has been a renewed impetus to re-examine the neurophysiological underpinnings of the hypothesis that repetitive, task-oriented locomotor training can induce neuroplasticity to promote functional recovery [15]. One challenge is the multi-layered control hierarchy for walking, which includes both spinal and supraspinal control circuitry. Recent studies have utilized noninvasive neuroimaging technologies, in particular electroencephalography (EEG), to confirm the role of cortical drive in lower extremity tasks including treadmill walking [16] and cycling [17]. Studies of healthy individuals have demonstrated that cortical resources are increased in the sensorimotor, prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in more challenging walking tasks [18] and that separate cortical processes are implicated for movement execution and motor control during gait [19]. Studies combining EEG with RAGT have demonstrated enhanced desynchronization in the motor areas of the cortex, an indicator of increased central drive, when actively walking with the robotic assistance compared to allowing the robot to passively move the limbs [20]. A similar experiment found increased pre-motor and parietal cortex activation when navigating through a virtual environment on a screen compared to walking with unrelated visual stimuli [21].

To our knowledge, EEG has not been utilized to capture cortical dynamics during lower extremity movements and gait in children with CP. A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study found that children with CP had increased sensorimotor activation during walking compared to typically developing peers that correlated with greater kinematic variability [22]. EEG studies in this population focus on upper extremity movements while seated [23], with one case study showing evidence of altered cortico-muscular coherence during grasping in a child with CP [24]. One contributor to the dearth of EEG studies in those with CP is the relatively high level of motor function and persistence required to complete the experiments, which often require numerous repetitive movements.

In this study we introduce the combination of an assistive exoskeleton and an exercise video game (exergame) as a tool for intensive rehabilitation and an experimental paradigm to study brain activation via EEG in children with crouch gait from CP. Children with crouch have persistent knee flexion during stance. The knee extension exercise here aimed to provide repetitive training to the legs to enable a more upright posture. We assess the effect of synergistic robotic assistance during knee extension on lower extremity kinematics and muscle activation. Additionally, we examine motor cortex activation during standing and utilize the game design to study, for the first time, cortical activation subserving knee extension in children with crouch gait from spastic diplegia.

II. Materials and Methods

A. Exoskeleton & Exercise Video Game

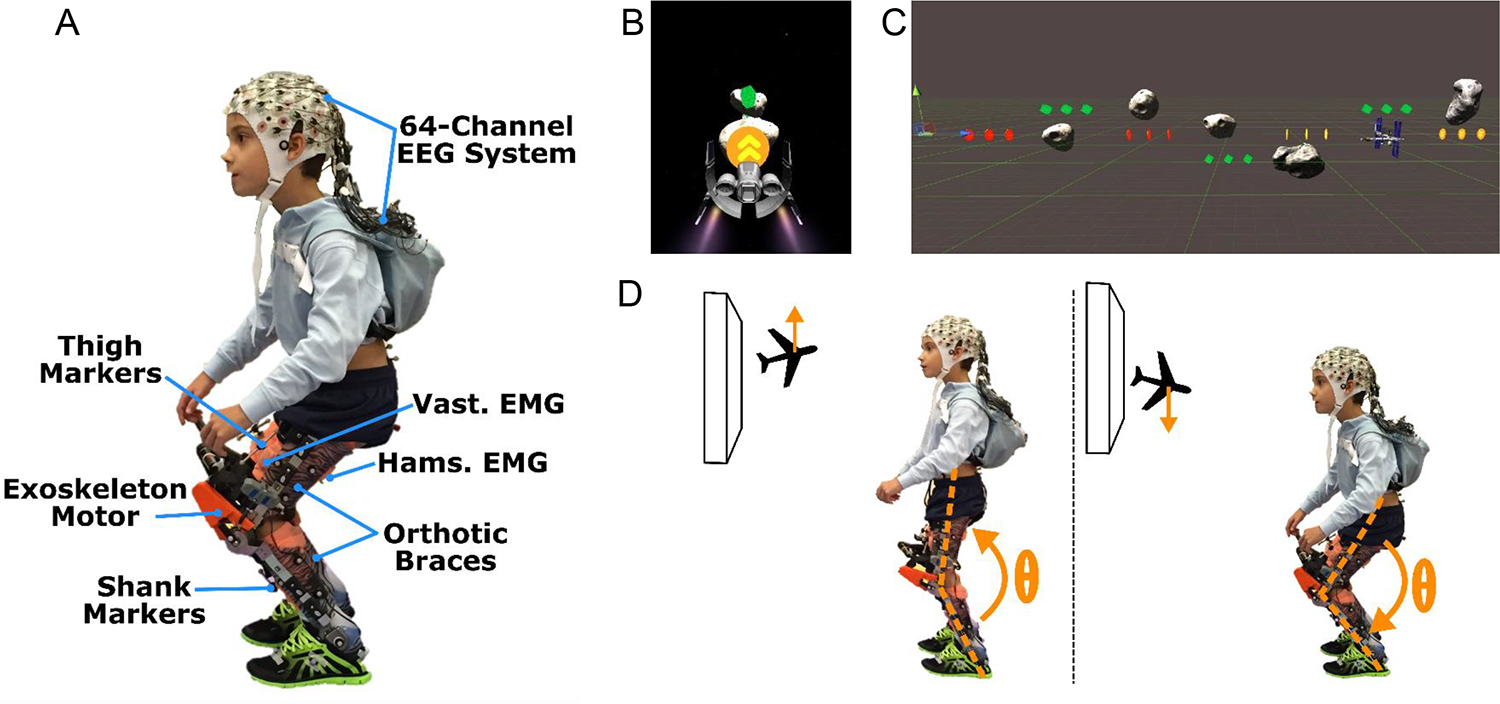

We have recently developed and tested a novel exoskeleton for providing knee extension assistance to individuals with crouch gait from cerebral palsy [13]. The device includes a motor and transmission system, mounted to a knee-ankle-foot orthosis (Fig. 1A). The exoskeleton contains on board sensors to measure knee angle, knee torque, and foot contact which allow for feedback control of extension assistance.

Figure 1.

A) Photograph of the exoskeleton with EEG, EMG, and motion capture markers. B) Screen capture of the Cube Destroyer video game as viewed on the screen during game play. C) Unity software layout showing the spacing between targets (green, gold, and red colored cubes) and obstacles (grey asteroids). D) Schematic of the knee extension task and the return to baseline posture elicited during the game play.

In this study the exoskeleton was combined with a video game to create a bilateral knee extension exercise task while standing. The video game, titled Cube Destroyer, was developed using Unity software, a cross-platform 3D game engine distributed by Unity Technologies. The exergame is modelled on an infinite runner concept, in which the subject pilots a space craft that moves at a constant speed (Fig. 1 B) with its vertical motion controlled by knee extension and flexion of the participant (Fig. 1D). The objective of the game is to pilot the craft through intervals of rings and cubes (i.e., targets) located at different heights while avoiding asteroid obstacles (Fig. 1C). At the beginning of each session, target height was calibrated in the baseline condition for each user, with one level below neutral standing posture corresponding to ~10% less than maximum knee flexion capability and one above neutral corresponding to ~10% less than maximum knee extension capability. Once these angles were reached (or exceeded) the position of the craft was held at the target level until the knee angle fell below the threshold. The calibrated target positions were the same for both the exoskeleton assisted and free conditions; thus, improved knee extension during game play was not expected to be a primary outcome. The user gains points in the game by successfully completing appropriately timed and sized knee flexion/extension motions to hit the targets. Targets are presented in 2 second intervals alternating between extension and flexion with 10 repetitions for both knee extension and knee flexion exercises lasting a total ~40 seconds for each trial of game play. Visual and audio feedback of successful completion of the exercise task was provided by explosion of cube and ring targets on the screen.

B. Participants and Experimental Protocol

This study was part of an approved Institutional Review Board Protocol (#13-CC-0210) at the National Institutes of Health. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of crouch gait from CP with knee flexion contracture less than 5° and Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) Level I-III. Prior to data collection, we obtained written informed consent and assent from the parent and the participant, respectively. In total, six participants completed the study (Table 1).

TABLE I.

Participant Demographics

| Age (yrs) | Gender | Height (m) | Mass (kg) | GMFCS Levela | MASb Score | Exoskeleton | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (kg) | Torquec (N-m/kg) | |||||||

| P1 | 6 | M | 1.11 | 20.0 | II | 0 | 3.1 | 0.15 |

| P2 | 11 | F | 1.56 | 40.8 | II | 1+ | 3.6 | 0.11 |

| P3 | 19 | F | 1.48 | 65.1 | II | 1 | 4.5 | 0.12 |

| P4 | 5 | M | 1.15 | 20.6 | II | 1+ | 2.6 | 0.17 |

| P5 | 12 | M | 1.72 | 69.3 | I | 1 | 3.8 | 0.13 |

| P6 | 11 | M | 1.35 | 32.0 | II | 2 | 3.0 | 0.19 |

GMFCS: Gross Motor Function Classification Scale.

MAS: Modified Ashworth Scale for hamstring of the more affected limb.

Torque is the amount of assistance provided during knee extension exercise.

This study was part of a larger protocol evaluating the use of a robotic exoskeleton to alleviate crouch gait during overground and treadmill walking in children with CP [13, 14]. The protocol consisted of six total visits lasting 2–4 hours each. Data for this study were collected during a single visit, with all participants having a minimum of 3 prior visits to acclimate to the exoskeleton. We collected kinematic, EMG, and EEG data while each participant completed 3–5 trials of the Cube Destroyer knee extension game in each of two modes: free and exoskeleton assisted. In the free mode the exoskeleton controller only actuated the motor to compensate for internal friction in the device, replicating baseline knee function. In the assist mode the exoskeleton provided a constant torque (Table 1) for knee extension assistance through the entire game. We also collected a minimum of 2 minutes of quiet standing as a baseline for EMG and EEG data. Kinematic data were collected at 100 Hz using 10 motion capture cameras (Vicon Motion Systems, Oxford, UK). Three non-collinear markers were placed on the feet, shank, thigh, and pelvis segments. Markers were also placed on the medial and lateral aspects of the ankle and knee joints. To assess the effect of assistance on muscle activity, data were collected at 1000 Hz from knee extensors (vastus lateralis) and knee flexors (medial hamstrings) using a wireless EMG system (Trigno, Delsys, Boston, MA). 64-channels of EEG data were collected at 1000 Hz using a wireless, active electrode EEG system (Brain Products, Morrisville, NC). EEG sensors were placed according to the 10–20 international system (Easy Cap, Germany) with reference placed at the FCz location. Electrode impedance was maintained below 20 kΩ. Kinematic, EMG, and EEG data were synchronized with a trigger pulse.

C. Data Analysis

Inverse kinematic analysis was performed using Visual 3D software (C-Motion, Gaithersburg, MD) to quantify lower-extremity joint angles, which were low-pass filtered at 6 Hz. The time of knee extension onset was identified by knee angle velocity, which was computed as the first derivative of knee angle. EEG signals were analyzed using a similar method as in [18]. Briefly, all trials for each participant were concatenated into a single data set. Noisy EEG channels, indicated by a standard deviation > 1000 μV or kurtosis > 5 standard deviations, were removed. EEG was then re-referenced to a common average. Next, an adaptive mixture independent component analysis (AMICA) available as a plugin from EEGLAB [25] was used to remove artifacts from eye blinks, saccades, and head/neck EMG.

EEG, EMG, and kinematic data were split into 3 second epochs surrounding the initiation of knee extension, starting from 1 second before initiation. Only epochs in which the participant reached his/her threshold knee extension were included in the analysis. EMG linear envelopes were computed bilaterally for the vastus lateralis and medial hamstring by detrending, band pass filtering (15–300 Hz), rectification and low pass filtering at 6 Hz. Due to the variation in knee angle and muscle activity, paired t-tests (p < 0.05) on individual means across trials were utilized to evaluate significant differences in peak knee extension angle and area under the curve of the EMG linear envelopes between free and assisted conditions.

To assess differences in cortical activity between quiet standing, free knee extension and exoskeleton assisted extension, we computed the power spectral density (PSD) using a Thomson’s multitaper estimate for each epoch for a subset of 6 electrodes (C1, CZ, C2, CP1, CPZ, and CP2) overlying the motor cortex based on somatotopy of the lower extremities. The PSD was then averaged across all epochs and electrodes for each condition (standing, free and powered exoskeleton). In addition, we identified independent components (ICs) from each participant that were attributed to motor processes based on topography, time-traces of voltage, and power spectra. To elucidate the activity of each IC during the knee extension exercise, we computed the event related spectral perturbation (ERSP) for each epoch by normalizing the spectrogram of each epoch by the mean baseline spectra calculated from the 1 second preceding the onset of knee extension [26]. These ERSPs were averaged across all epochs for each condition (free and exoskeleton assisted). Significant ERSP values (ɑ < 0.05) were identified using a bootstrapping technique [25].

III. Results

A. Kinematics and EMG

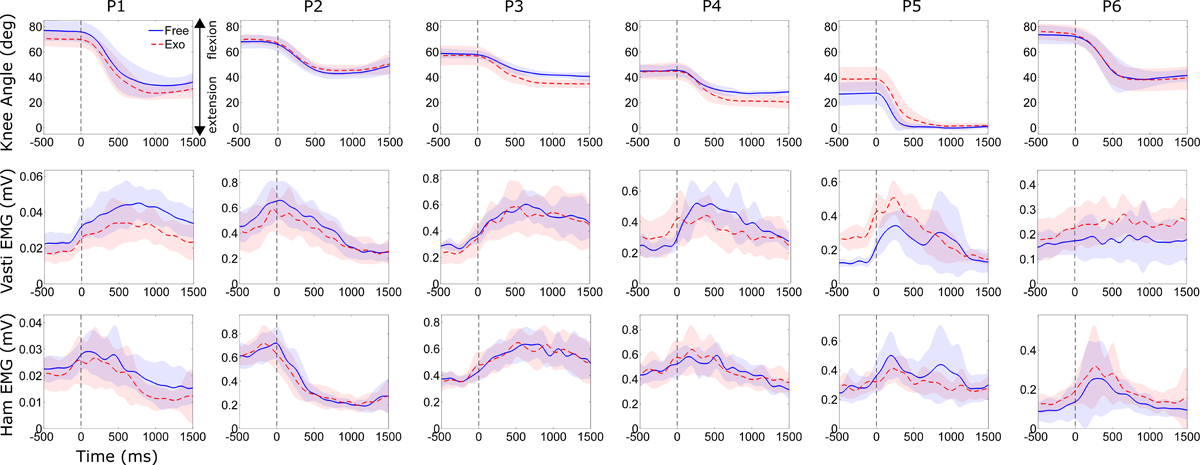

All six participants were able to successfully navigate through the game under both free and exoskeleton assisted conditions completing an average of 23 and 22 extensions for each condition, respectively. No significant difference in peak knee extension was found between the free and exoskeleton assisted conditions at the group level. Despite maintaining the targets at the same position across conditions, we observed clinically meaningful difference (> 5°) in peak knee extension in 3/6 subjects (P1, P3, and P4) with the knee more extended with exoskeleton assistance compared to without (Fig. 2). One participant (P5) adopted a more flexed posture during use of the exoskeleton in assistive mode than when the knee joint was free (P5), but was able to reach the same amount of knee extension under both conditions.

Figure 2.

Knee joint angle (top row), vastus lateralis EMG (second row), and medial hamstring EMG (third row) during knee extension exercise without (solid blue line) and with (dashed red line) robotic assistance for each participant. Data shown are from the more crouched limb. Vertical dashed line at time 0 msec indicates start of knee extension. Shading depicts ±1 standard deviation.

Interestingly, we observed no significant change in knee extensor muscle activity when exoskeleton extension assistance was provided during the exercise (Fig 2). One participant (P5) had increased vasti activity during trials with assistance; this was likely due to the difference in posture. There were no significant difference in knee flexor activity between trials with and without assistance.

B. EEG

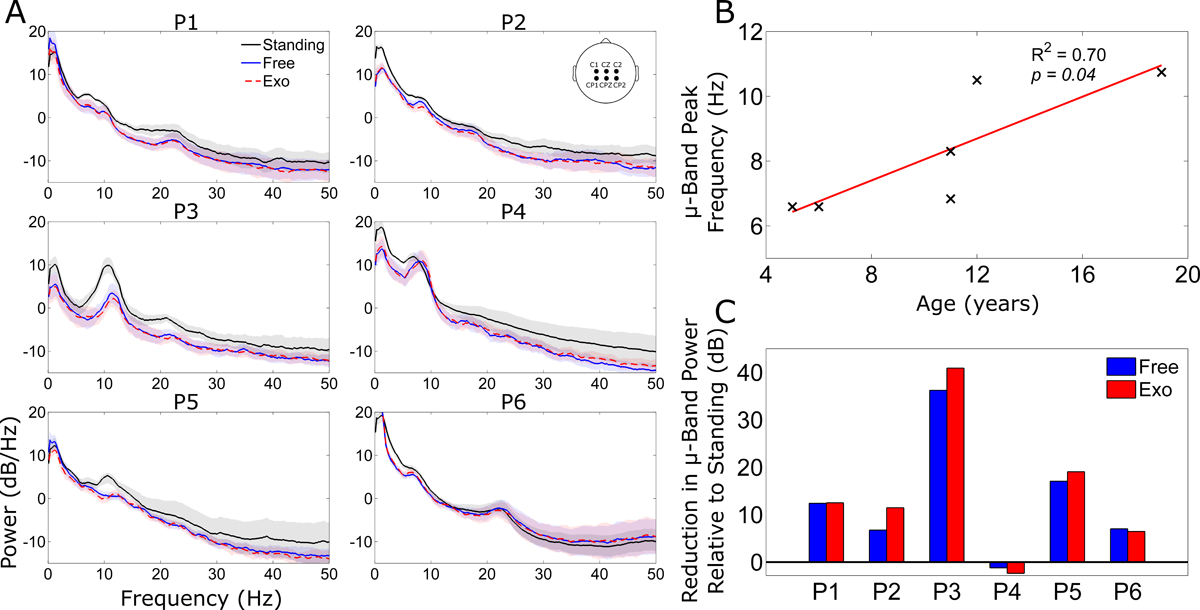

All six participants had identifiable peaks in the PSD in the upper θ / μ-band (6–11 Hz) during quiet standing (Fig. 3A). There was a significant correlation between peak μ-band frequency at rest and the age of the participant (Fig. 3B) with the lowest peak (6.6 Hz) observed in the youngest participant (5 years) while the oldest participant (19 years) had the highest peak frequency (10.7 Hz). There was a significant reduction in μ-band power during the knee extension exercise in 5/6 participants, a neural correlate for increased cortical activity. Interestingly, we observed no significant differences in the PSD between knee extension with and without exoskeleton assistance in any participant (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

A) Grand mean power spectral density (PSD) across six midline electrodes (see inset) for quiet standing (black line), free knee extension epochs (blue line), and exoskeleton assisted extension epochs (red dash line). The shading indicates ±1 standard deviation. B) Correlation of the peak μ-band frequency of the PSD during quiet standing with age in the six participants. C) The mean reduction in μ-band power relative to standing, as assessed by area under the PSD curve, during free (blue bar) and exoskeleton assisted (red bar) knee extension.

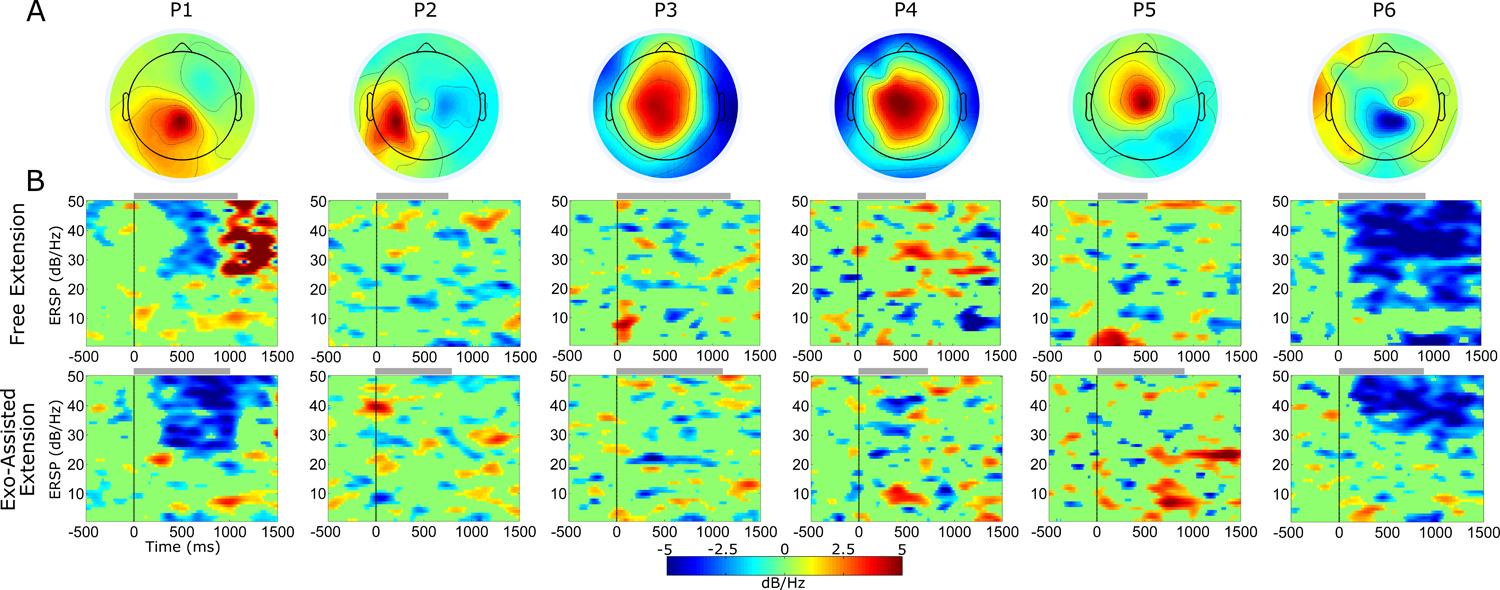

We identified central mid-line ICs in 5/6 participants, with the remaining individual (P2) showing a more lateral left side scalp projection (Fig. 4A). All 6 ICs contained prominent μ-band activity in the PSD with reduced power during knee extension compared to standing, indicative of motor related activity. Cortical dynamics during the knee extension exercise, as measured by ERSP, varied considerably across individuals (Fig. 4B). Generally, there were not large differences in cortical activation patterns within individuals between the free and exoskeleton assisted conditions.

Figure 4.

A) Scalp projection of the motor-related independent component (IC) examined for each participant. B) Mean event related spectral perturbation (ERSP) across epochs of knee extension without (top row) and with (bottom row) exoskeleton assistance. ERSPs are masked for significance with non-significant values set to 0 dB (green). Gray bars at the top of each ERSP plot indicate the mean time period of knee extension for each participant and condition.

Two participants (P1 and P6) showed significant event-related depolarization (ERD) in high β (20–30 Hz) and low γ (30–50 Hz) during knee extension. P1 had stronger ERD in these bands during exoskeleton assisted extension with stronger synchronization following free extension. P6 appeared to show stronger ERD in the μ and β band in the free condition compared to assisted, suggesting increased cortical resources were used. Similarly, P2 and P5 had elevated μ and β band ERD in the free condition, although each had larger re-synchronization after knee extension in the assisted condition. P3 and P4 both showed a slightly larger μ and β ERD during exoskeleton assisted knee extension compared to free.

IV. Discussion

The requirements of an effective rehabilitation paradigm, namely large amounts of task-oriented practice, are also necessary for a viable motor EEG study. In this paper, we demonstrated the utility of a robotic exoskeleton combined with exergaming for successful completion of a challenging exercise task and as an appropriate paradigm for an EEG study in children with CP.

The effect of robotic assistance on lower extremity function in those with neurological deficits is an active area of research, with preliminary results demonstrating both reduced [27] and increased [28] muscle activity when walking with robotic assistance. In this study we show that children with crouch gait from CP maintain similar knee extensor muscle activity in the presence of synergistic robotic assistance during a weight-bearing training exercise compared to exercising without the robot. Exoskeleton assistance resulted in greater knee extension, and more upright posture, in half our cohort despite the target positions in the exergame remaining the same across conditions. Interestingly, volitional knee extensor muscle activity was maintained with the exoskeleton regardless of whether knee extension excursion improved.

Our results suggest that providing robotic assistance did not diminish engagement in the task. All participants were able to complete the full run of exercises with and without powered assistance. In more affected children than this cohort it may be possible to utilize robotic assistance to facilitate otherwise unattainable movements. Previous studies have shown that volitional muscle activity during robotic interventions in children with CP is dependent on level of encouragement from therapists [28]. We did not explicitly encourage participants during the exercise, but they received feedback in the form of a score that increased by successfully hitting targets in the video game. While the data presented here were averaged over a single session, future analyses may examine the effect of robotic assistance over time, both within and across sessions, to determine if users adapt their muscle activity and if such adaptations are retained without the exoskeleton. Given that those with CP have reduced motivation to complete prolonged motor rehabilitation tasks compared to typically developing peers [29], inclusion of an exergame interface in combination with an assistive exoskeleton may enhance the willingness of children with disabilities to complete larger doses of more intense therapy, thereby improving outcomes.

Our EEG results demonstrated reduced μ-band power in central midline electrodes during knee extension in most participants, a neural correlate for increased cortical activation. We observed no differences in activation of cortical resources between the exoskeleton assisted and free knee extension exercise. This observation is corroborated by activity of knee extensor muscles, and suggests that children with CP did not simply offload the knee extension task to the exoskeleton but instead remained actively engaged in the exercise. We observed different activation patterns across individuals in brain sources originating from the motor areas of the cortex. These distinct patterns are not surprising given the reorganization that is known to take place in the motor system following perinatal injuries [30], as was the case for our cohort. Our future work will focus on analysis of EEG data during knee extension with and without robotic assistance to increase understanding of cortical activity underlying lower extremity function in those with CP, to assess changes in brain activation that may accompany functional improvements over the time course of therapy, and to examine the effect of higher assistive torque levels on user engagement.

Our data demonstrate a correlation between age and the peak frequency of sensorimotor μ rhythm in our cohort suggesting that, similar to typically developing children [31], children with CP may follow a developmental trajectory in μ rhythm. Yet our data also suggest the spectral development of sensorimotor μ rhythm may be delayed in children with CP, given that typical rhythms reach the range of 8–10 Hz before age 4 [32]. The oldest participant in our cohort (19 y/o) had a similar peak as healthy adults, suggesting those with CP may recoup this delay as they age. The current study is limited by the relatively small sample size across a range of ages and functional abilities. Future work will focus on exploring this in a broader and more systematic way to determine the functional significance of sensorimotor μ rhythm development in CP. Importantly, the experimental paradigm introduced here can capture cortical dynamics during movement, and thus facilitates use of motor execution to characterize μ rhythm development, an approach that has long been accepted as a gold standard in adults [32] but to date has not been as readily achievable in children, particularly those with motor disability.

Acknowledgement

We thank Christopher Stanley, Katharine Alter, Cristiane Zampieri-Gallagher, Laurie Ohlrich, Abhinav Sharma, and Scott Galey for their assistance with data collection. We thank Mark DeHarde and Ultraflex Systems (Pottsville, PA) for providing the orthoses and for his expertise in optimizing their fit and settings. This research was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Clinical Center.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institutes of Health (protocol # 13-CC-0210).

References

- [1].Odding E, Roebroeck ME, and Stam HJ, “The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors,” Disabil Rehabil, vol. 28, pp. 183–91, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gajdosik CG and Cicirello N, “Secondary conditions of the musculoskeletal system in adolescents and adults with cerebral palsy,” Phys Occup Ther Pediatr, vol. 21, pp. 49–68, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].O’Shea TM, “Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cerbral palsy in near-term/term infants,” Clin Obstet Gynecol, vol. 51, pp. 816–828, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Damiano DL, Alter KE, and Chambers H, “New clinical and research trends in lower extremity management for ambulatory children with cerebral palsy,” Phys Med Rehabil Clinics North America, vol. 20, pp. 469–491, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hoare BJ, et al. , “Constraint-induced movement therapy in the treatment of upper limb in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy,” Clin Rehabil, vol. 21, pp. 675–685, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sandlund M, McDonough S, and Hager-Ross C, “Interactive computer play in rehabilitaiton of children with sensorimotor disorders: a systematic review,” Dev Med Child Neurol, vol. 51, pp. 173–179, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wu YN, et al. , “Combined passive stretching and active movement rehabilitation of lower-limb impariments in children with cerebral palsy using a portable robot,” Neurorehabil Neur Repair, vol. 25, pp. 378–385, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Michmizos KP, et al. , “Roboti-aided neurorehabilitation: a pediatric robot for ankle rehabilitaiton,” IEEE Trans Neur Sys Rehabil Eng, vol. 23, pp. 1056–1067, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Borggraefe I, et al. , “Robotic-assisted treadmill therapy improves walking and standing performance in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy,” Eur J Paediatr Neurol, vol. 14, pp. 496–502, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lefmann S, Russo R, and Hillier S, “The effectiveness of robotic-assisted gait training for paediatric gait disorders: systematic review,” J NeuroEng Rehabil, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Willoughby K, et al. , “Efficacy of partial body weight-supported treadmill training compared with overground walking practice for children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial,” Arch Phys Med Rehabil, vol. 91, pp. 333–339, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dollar A and Herr H, “Lower Extremity Exoskeletons and Active Orthoses: Challenges and State-of-the-Art,” IEEE Trans Robotics, vol. 24, pp. 144–158, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lerner ZF, Damiano DL, Park HS, Gravunder A, and Bulea TC, “A Robotic Exoskeleton for Treatment of Crouch Gait in Children with Cerebral Palsy: Design and Initial Application,” IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lerner ZF, Damiano DL, and Bulea TC, “A robotic exoskeleton to treat crouch gait from cerebral palsy: initial kinematic and neuromuscular evaluation,” Proc 38th IEEE Int Conf Eng Med Biol Soc, pp. 2214–2217, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dobkin BH and Duncan PW, “Should body weight-supported treadmill training and robotic-assistive steppers for locomotor training trot back to the starting gate?,” Neurorehabil Neur Repair, vol. 26, pp. 308–317, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gwin JT, et al. , Electrocortical activity is coupled to gait cycle phase during treadmill walking,”Neuroimage, vol. 54, pp. 1289–1296, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jain S, et al. , “EEG during pedaling: evidence for cortical control of lcomotor tasks,” Clin. Neurophysiol, vol. 124, pp. 379–390, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bulea TC, et al. , “Prefrontal, posterior parietal and sensorimotor network activity underlying speed control during walking,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol 9, no. 247, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wagner J, et al. , “Distinct β band oscillatory networks subserving motor and cognitive control during gait adaptation,” J Neurosci, vol. 36, pp. 2212–2226, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wagner J, et al. , “Level of participation in robotic-assisted treadmill walking modulates midline sesnorimotor EEG rhthms in able-bodied subjects,” Neuroimage, vol. 63, pp. 1203–1211, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wagner J, et al. , “It’s how you get there: walking down a virtual alley activates premotor and parietal areas,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 8, no. 93, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kurz M, et al. , “An fNIRS exploratory investigation of the cortical activity during gait in children with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy,” Brain & Dev, vol. 36, pp. 870–877, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rigoldi C, et al. , “Movement analysis and EEG recordings in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy,” Exp Brain Res, vol. 223, pp. 517–524, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Riquelme I, et al. , “Altered corticomuscular coherence elicited by paced isotonic contractions in individuals with cerebral palsy: A case-control study,” J. Electromyo & Kinesiol, vol. 24, pp. 928–933, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Delorme A, Makeig S, “EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis o fsingle-trial EEG dynamics including indepdenent component analysis,” J. Neurosci. Meth, vol. 134, pp. 9–21, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Makeig S, “Auditory event-related dynamics of the EEG spectrum and effects of exposure to tones,” Electroenceph Clin Neurphysiol, vol. 86, pp. 283–293, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Coenen P, et al. , “Robot-assisted walking vs overground walking in stroke patients: an evaluation of muscle activity,” J. Rehabil Med, vol. 44, pp. 331–337, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schuler AT, Muller R, and van Hedel JH, “Leg surface electromyography patterns in children with neuro-orthopedic disorders walking on a treadmill unassisted and assisted by a robot with and without encouragement,” J Neuroeng Rehabil, vol. 10, no. 78, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Majnemer A, et al. , “Level of motivation in mastering challenging tasks in children with cerebral palsy,” Dev Med Child Neurolog, vol. 52, pp. 1120–1126, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Staudt M, “Reorganization after pre- and perinatal brain lesions,” J Anat, vol. 217, pp 469–474, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Berchicci M, et al. , “Development of mu rhythm in infants and preschool children,” Dev Neurosci, vol. 33, pp. 130–143, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Thorpe SG, Cannon EN, and Fox NA, “Spectral and source structural development of mu and alpha rhythms from infancy through adulthood,” Clin Neurophysiol, vol. 127, pp. 254–269, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]