Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

This work describes the development of a manualized best-practice hearing intervention for older adults participating in the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomized controlled clinical trial. Manualization of interventions for clinical trials is critical for assuring intervention fidelity and quality, especially in large multi-site studies. The multi-site ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial is designed to assess the efficacy of a hearing intervention on rates of cognitive decline in older adults. We describe the development of the manualized hearing intervention through an iterative process that included addressing implementation questions through the completion of a feasibility study (ACHIEVE-Feasibility).

DESIGN:

Following published recommendations for manualized intervention development, an iterative process was used to define the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements and create an initial manual. The intervention was then delivered within the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study using one-group pre-post design appropriate for assessing questions related to implementation. Participants were recruited from the Tampa, Florida area between May 2015 and April 2016. Inclusion criteria were cognitively-healthy adults aged 70–89 with symmetrical mild to moderately-severe sensorineural hearing loss. The ACHIEVE-Feasibility study sought to assess the implementation of the manualized hearing intervention by: (1) confirming improvement in expected outcomes were achieved including aided speech in noise performance and perception of disease-specific self-report measures; (2) determining whether the participants would comply with the intervention including session attendance and use of hearing aids; and, (3) determining whether the intervention sessions could be delivered within a reasonable timeframe.

RESULTS:

The initial manualized intervention that incorporated the identified best-practice elements was evaluated for feasibility among 21 eligible participants and 9 communication partners. Post-intervention expected outcomes were obtained with speech-in-noise performance results demonstrating a significant improvement under the aided condition and self-reported measures showing a significant reduction in self-perceived hearing handicap. Compliance was excellent, with 20 of the 21 participants (95.2%) completing all intervention sessions, and 19 (90.4%) returning for the 6-month post-intervention visit. Furthermore, self-reported hearing aid compliance was >8 hrs/day, and the average daily hearing aid use from datalogging was 7.8 hours. Study completion was delivered in a reasonable timeframe with visits ranging from 27 – 85 minutes per visit. Through an iterative process, the intervention elements were refined, and the accompanying manual was revised based on the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study activities, results, and clinician and participant informal feedback.

CONCLUSION:

The processes for the development of a manualized intervention described here provide guidance for future researchers who aim to examine the efficacy of approaches for the treatment of hearing loss in a clinical trial. The manualized ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention provides a patient-centered, yet standardized, step-by-step process for comprehensive audiological assessment, goal setting, and treatment through the use of hearing aids, other hearing assistive technologies, counseling and education aimed at supporting self-management of hearing loss. The ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention is feasible in terms of implementation with respect to verified expected outcomes, compliance, and reasonable timeframe delivery. Our processes assure intervention fidelity and quality for use in the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial ( NCT03243422).

Keywords: Manualization, Hearing Intervention, Feasibility, Clinical Trial

Introduction

Over the past 20 years much has been written in the audiological literature about the need for the development of evidence-based interventions informed by well-controlled randomized trials [e.g., Ferguson et al. (2017); Knudsen et al. (2010)]. A key component in conducting a randomized controlled trial is the development of a manual of procedures. Manualization refers to the development of a treatment or intervention guide that includes information about treatment dose, interventionist training, procedural specifics, and intervention monitoring and fidelity (Borelli 2011). Manualization of an intervention provides structure for intervention delivery, allows for monitoring of treatment fidelity across sites and providers, and allows for treatment replication (McMurran et al. 2005). Manualization is an iterative process including first the identification of the intervention elements, structured description of the elements with specific written procedural explanation and provided examples; and, concludes after refinement based on the evaluation of the implementation of the manualized intervention.

The development and adaptation of manualized interventions is fast becoming a focus of clinical trial research. Through describing the structural and conceptual boundaries of an intervention, manuals assistance in the dissemination and implementation, so that researchers and clinicians can monitor adherence to principles underpinning an intervention (Eifert et al. 1997; Thompson-Hollands et al. 2015). If such fidelity is not established, study results may be ambiguous, incapable of future replication, or difficult to apply in other treatment contexts or in stand-of-care clinical use. Although there is some disagreement between researchers and practitioners regarding the utility of intervention manuals for everyday clinical practice, due to factors such as applicability to diverse patient populations and an inadequate focus on the patient-clinician relationship (Carroll et al. 2002), studies incorporating manualized interventions demonstrate improved behavior change outcomes in several areas of health. Evidence supporting increased intervention success with the use of a manualized interventions comes from studies such as those examining diabetes management (e.g., Miller et al. 2014), end-of-life psychological distress (e.g., Breitbart et al. 2015; LeMay et al. 2008), and substance abuse (e.g., Chiesa et al. 2014). In addition, a few psychosocial studies compared the effectiveness of manualized versus individualized treatments and revealed that manualized interventions are associated with better treatment outcomes, especially when they are flexible and when the content is easily translated into action (Mann, 2009; Vande Voort, 2010). As healthcare funding becomes increasingly dependent on evidence-based practices (Goldstein et al. 2012), there will be a continued need for systematic development and dissemination of manualized interventions. In fact, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recognizes the importance of a manual of procedures and requires submission of manuals for all multi-site studies that are supported by NIH (National Institutes of Health, 2013).

The present work describes the development of a manualized best-practices audiological intervention for older adults with hearing loss for use in a randomized controlled trial designed to investigate whether hearing loss intervention versus a successful aging education intervention reduces the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults [NCT03243422; for description of the trial protocol see Deal et al. (2018)]. The clinical trial, Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE), was motivated by the results of research demonstrating an independent association between hearing loss in older adults and cognitive decline, including epidemiologic studies (Lin, Ferrucci, et al. 2011; Lin, Metter, et al. 2011) and meta-analysis (Loughrey et al. 2018). Furthermore, there are cross-sectional findings that suggest hearing aid use in older adults is associated with better cognition (Amieva et al. 2015; Dawes et al. 2014). As these latter observations could simply reflect that those with greater cognitive abilities are more likely to pursue hearing aid use, the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial is designed as the first well-controlled longitudinal study, in which there will be systematic examination of the effects of hearing intervention on cognitive function and rates of cognitive decline in older individuals. In preparation for the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial, through a clinical trial planning grant award (NIH; R34AG046548), an extensive development phase was conducted including protocol development and refinement, piloting, and the manualization and feasibility assessment of the best-practices hearing intervention described here.

Development of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention and Initial Manual

Manualized interventions are not widely used in audiology, although there are published evidence-based guidelines for the management of adult hearing loss [e.g., American Academy of Audiology (AAA; Valente et al. 2006), British Society of Audiology (2016)]. While these guidelines are useful, they do not provide the kind of structured intervention protocol that is needed in a large-scale multi-site randomized controlled trial. The manualized intervention described here was designed to provide the needed structure for the delivery of best-practices hearing intervention in the ACHIEVE trial; thus, referred to as ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention. First, we describe the selection of the elements for ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention before describing the initial manualization process.

The framework for the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention was the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (World Health Organization (2001). The International Classification of Functioning is a biopsychosocial approach that focuses on a person’s ability to engage in activities and participate in life situations, which can be impacted by changes in body structures and/or body functions, and is influenced by both environmental and personal contextual factors. The main goal of intervention becomes improving a person’s quality of life by eliminating or minimizing activity limitations and participation restrictions. While hearing aids are a critical component of the intervention, they do not automatically guarantee improved quality of life and functional hearing in all situations. Behavior change is necessary in order to reduce activity limitations and participation restrictions. Research clearly supports an approach to hearing intervention that is patient-centered, guided by the identification of individual needs, with the setting of specific goals, engagement in shared-informed decision-making, and the development of self-management abilities [see British Society of Audiology (2016) for discussion].

With the International Classification of Functioning as the framework, an iterative process of identifying and defining the elements for ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention began by reviewing the American Academy of Audiology’s Guideline for the Audiologic Management of Adult Hearing Impairment completed in 2006 (Valente et al. 2006). The guideline identifies four general process areas involved in patient-centered, best-practice hearing rehabilitation for adults: (1) Assessment and Goal Settings; (2) Technical Aspects of Treatment (i.e., hearing aids and hearing assistive devices); (3) Orientation, Counseling, and Follow-up; and, (4) Outcomes Assessment. The next step involved a review of the research published since 2006 to identify evidence that could further inform the intervention. The result of these two activities was the production of a detailed outline of the steps to be included in ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention, along with identification of questions that needed additional review. These activities were completed between October and November of 2014 by four experienced audiologists1. The outline of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention components and questions were submitted for review to a panel of seven expert audiologists from a variety of practice settings2 and members of the ACHIEVE clinical trial planning grant team3. This was followed by an in-person two-day meeting on December 9–10, 2014, during which the panel of experts came to consensus regarding the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements. The ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Elements and Associated Clinical Procedures & Materials.

| Elements | Clinical Procedures & Materials |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive Audiometric Evaluation | • Otoscopy • Immitance Testing: Tympanometry & Acoustic Reflex thresholds • Pure- tone and speech audiometry • Unaided soundfield speech-in-noise testing [QuickSIN; Killion et al. (2003)] |

| Goal Setting & Goal Evaluation | • Client Oriented Scale of Improvement [COSI; Dillon et al. (1997)] • Review of goal attainment by using standard questions on degree of change and current ability |

| Supporting Self-Management | • Individualized-Active Communication Education [I-ACE (Hickson et al. (2019)] ○ Module 1: “Introduction to I-ACE” ○ Module 2: “Communication Tactics” ○ Module 3: “Communication in Background Noise” ○ Module 4: “HATs & Resources” • C2Hear Reusable Learning Objects [RLO; (Ferguson et al., 2016)] ○ RLO 1: “Introduction to C2Hear Online”; ○ RLO 2: “What to Expect When Wearing Hearing Aids” ○ RLO 3: “Communication Tactics” ○ RLO 4: “Phones & Other Devices” |

| Hearing Aid Verification, Fitting, & Orientation | • Hearing aid acoustical verification via electroacoustic analysis compared to manufacturer specifications • Hearing aid selection based on comprehensive evaluation results and goal setting • Hearing aid programming and verification of fitting via real-ear probe-microphone assessment to NAL-NL2 targets • Hearing aid orientation with demonstration and reenactment • Hearing aid programming adjustments and verification of adjustments via real-ear probe-microphone assessment to NAL-NL2 targets |

| Hearing Assistive Technology Fitting & Orientation | • Hearing Assistive Technology (HAT) selection based on comprehensive evaluation results, goal setting & goal evaluation • Fitting of HAT • HAT orientation with demonstration and reenactment • HAT programming adjustments |

| Outcomes Assessment | • Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening version [HHIE-S; Ventry et al. (1983)] • Hearing Aid Data Logging • International Outcome Inventory-Hearing Aids [IOI-HA; Cox et al. (2000)] • International Outcome Inventory-Alternative Interventions [IOI-AI; Noble (2002)] • International Outcome Inventory-Significant Other [IOI-SO; Noble (2002)] • Aided speech-in-noise performance using the Quick Speech-in-Noise Test [QuickSIN; Killion et al. (2003)] |

Note: QuickSIN = Quick Speech in Noise Test; COSI = Client Oriented Scale of Improvement; I-ACE = Individualized-Active Communication Education; HATs = Hearing Assistive Technologies; RLO = Reusable Learning Objects; HHIE-S = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening version; IOI = International Outcome Inventory; HA = Hearing Aids; AI = Alternative Interventions; SO = Significant Other.

The finalized elements and recommendations were incorporated in the first written structured version of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual following NIH example guidelines and published recommendations for manual development (Carroll and Nuro 2002; Goldstein et al. 2012). The ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual, which was kept in word-document format, was designed to provide step-by-step instructions that could be used in real-time by the study audiologist while completing all the elements of the intervention. These elements, displayed in Table 1, included many standard clinical procedures, such as conducting pure tone audiometry, speech recognition testing, and obtaining real-ear probe-microphone verifications measures. Integrated throughout the intervention sessions was the use of written and digitally recorded materials to support the self-management of hearing loss and communication (see Table 1, see “Supporting Self-Management” section). The ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual guided when these materials were provided, and how they were presented and discussed with the participants.

Specifically, the printed materials used to support self-management throughout the intervention sessions were informed by the evidence-based Individualized Active Communication Education (I-ACE) program developed by Hickson and colleagues at the University of Queensland, Australia (Hickson et al. 2019). I-ACE is based on the group ACE program (Hickson et al. 2007), and covers topics such as communication needs, improving conversation in background noise, communication around the home, hearing devices, and understanding difficult speakers, which represent some of the most frequently-reported difficulties among individuals with hearing loss (Dillon et al. 1997). Evidence for the efficacy of ACE was established in a randomized controlled trial in which participants demonstrated significantly improved outcomes to self-reported activity limitations and participation restrictions and improved self-management skills compared to a placebo program (Hickson et al. 2007). The printed I-ACE materials were reproduced with permission to fit into the visit schedule and compliment the other provided materials used in ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention. Additional material included in our approach to self-management, was the use of multi-media reusable learning objects (RLOs; see Table 1 “Supporting Self-Management” section) developed by Ferguson and colleagues (2016). These C2Hear RLOs are short video clips spoken in British English with captions and were designed to support first-time hearing aid users adapting to hearing aid use. In a randomized controlled trial comparing hearing aid fittings supplemented with C2Hear RLOs to standard clinical practice (i.e., face-to-face counseling and orientation alone), participants utilizing the C2Hear RLOs demonstrated increased knowledge and confidence in using and maintaining hearing aids (Ferguson et al. 2016).

With the first version of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual describing how to complete the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements and with all the supporting materials prepared, the next step in the iterative process was to conduct a feasibility study. The purpose of the feasibility study, ACHIEVE-Feasibility, was to address critical questions related to the implementation of the intervention. Conducting feasibility studies focusing on process, resources, management, intervention implementation, and intervention acceptability by all stakeholders, is an important first step in planning a large-scale randomized controlled trial (Orsmond et al. 2015; Tickle-Dengen 2013). Described below is the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manualization process refined by the results of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study. Following the results of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study, we provide a discussion on the changes to the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements and subsequent ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual revisions. The ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements that were changed and ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual revisions were completed through an iterative process that was informed by the study results and informal clinician and participant feedback, all of which were important to obtain in order to continue the refinement of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention prior to a planned ACHIEVE pilot study (ACHIEVE-Pilot study; Deal et al., 2017) and, ultimately, the initiation of the current ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial (protocol described in Deal et al., 2018; NCT03243422).

Materials and Methods

ACHIEVE-Feasibility Design & Questions

Implementation studies can confirm the ability for the intervention to yield expected outcomes, identify concerns with compliance with intervention, and determine the feasibility of intervention delivery within the resources available. In addition, qualitative responses by those delivering the intervention and those receiving the intervention can inform the need for any changes in the intervention protocol prior to use in a large-scale multi-site clinical trial. To address these facets of implementation for the initial version of the manualized ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention, we conducted a feasibility study in accordance, when applicable, with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 guidelines statement extension for pilot and feasibility trials (Eldridge et al. 2016; Thabane et al. 2016). The completed CONSORT Checklist can be found in Supplemental Table 1 (ST1); however, it should be noted, the CONSORT extension guidelines for pilot and feasibility trials were published in 2016 (Eldridge et al. 2016), while the design and execution of the presently described ACHIEVE-Feasibility study was conducted in 2015.

The ACHIEVE-Feasibility study was a non-randomized, single-group, within-subjects design that addressed the following three questions related to assessment of intervention implementation: (1) Would the intervention components lead to expected outcomes, including improvements in objective speech recognition, decreases in the self-perception of hearing handicap, omnibus outcomes consistent with published norms, and/or attainment of individualized intervention goals?; (2) Would the participants comply with the intervention, including completing the scheduled intervention visits and using amplification daily?; (3) Could the elements of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention be delivered within a reasonable timeframe? Systematically addressing questions related to expected outcomes, compliance, and timeliness, as well as identification of any unanticipated aspects of intervention delivery, were important preparatory steps in the development of the manualized hearing intervention for the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial (Deal et al., 2018; NCT03243422).

Participants

To address questions related to feasibility of an intervention, formal sample size calculations are not necessary (Tickle-Dengen 2013); however, the sample size should be sufficient to obtain the answers to the specific questions posed. Based on our past audiology intervention research and clinical experience and feedback from the reviewers and program officer of the supporting clinical trials planning grant (NIH; R34AG046548), we anticipated that the ACHIEVE-Feasibility questions would be able to be adequately addressed with approximately 20 participants. Thus, we consented and then screened a convenience sample of 24 older adults (13 females; 11 males) recruited from the larger Tampa Bay, FL area through audiologist referral or in response to study announcements via email, clinic waiting room advertisements, or posters and brochures posted throughout the university campus and the local community.

Criteria for inclusion into the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study matched the specified inclusion/exclusion criteria that we anticipated utilizing in the lager, multi-site ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial designed to assess the efficacy of hearing intervention on the trajectory of cognitive decline in older adults (for details see Deal et al., 2018). For inclusion in the forthcoming ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial, participants are to exhibit normal cognitive function at study onset with the Mini Mental State Exam [MMSE; Folstein et al. (1973)] used as an initial screening measure. Thus, to be included in this feasibility study, participants had to score of 24 or better on the MMSE. With criteria set to include cognitively intact individuals with age-related hearing loss the following audiometric criteria was required too. Individuals has to present with a word recognition in quiet performance, assessed using NU-6 ordered by difficulty material (Hurley et al. 2003) presented at a presumed optimal listening level (Guthrie et al. 2009) of greater than 60% in the better ear and a better ear pure-tone average (PTA) between 25 to 70-dB HL (PTA 500, 1000, 2000 Hz). Individuals were also excluded from the study if they did not speak fluent American English and had poorer than 20/40 vision (corrected) as validated by the MNREAD Acuity Chart (Mansfield & Legge, 2007). Individuals with a self-reported history of excessive noise exposure, potentially ototoxic agents, or previous use of hearing devices were also excluded. Three of the 24 consented participants failed to meet study inclusion criteria due to better than a 25 dB HL PTA in the better ear.

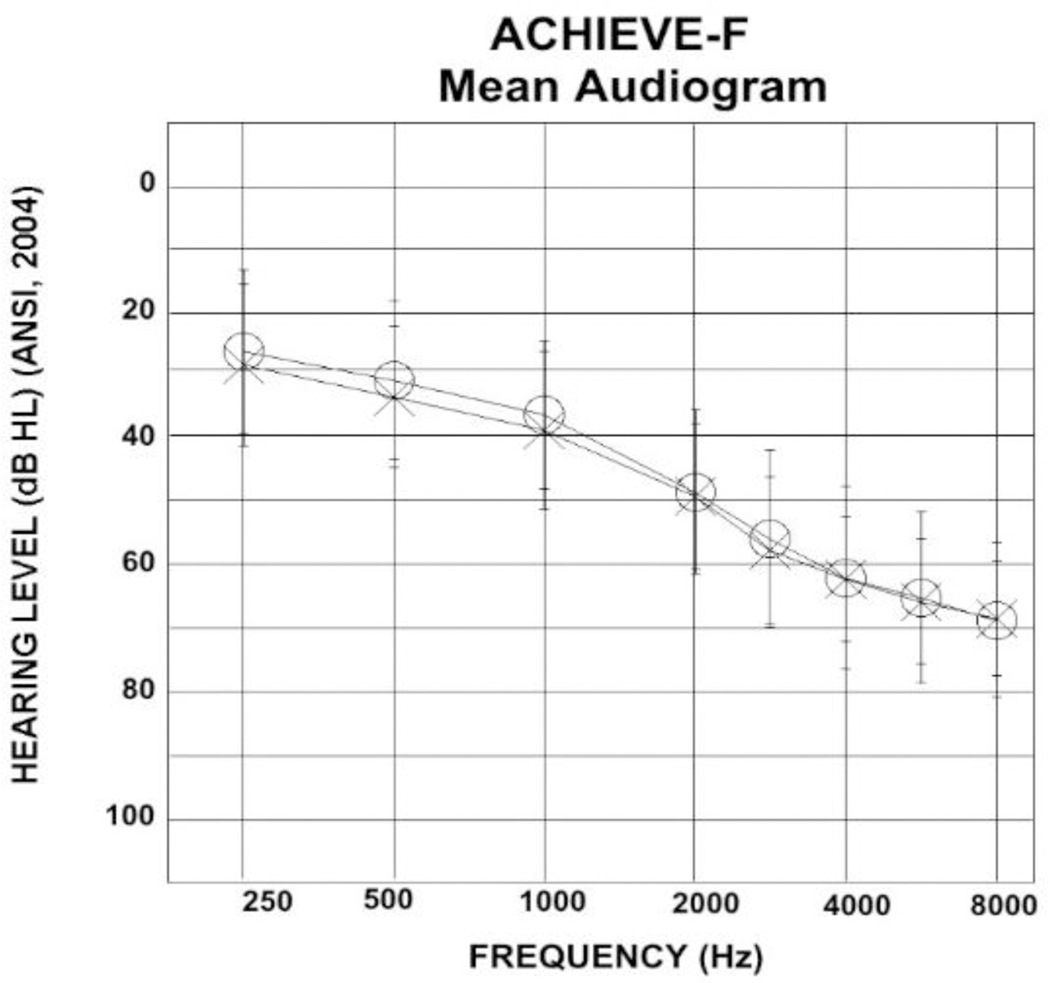

In keeping with CONSORT reporting guidelines, detailed demographic data for the 21 eligible participants are shown in Table 2. Participants ranged in age from 74 to 84 years old, with a mean age of 77.9 years. Ten of the participants were female and 11 were male. Nineteen participants were from White, non-Hispanic/Latino backgrounds, one participant was African-American, and one was Hispanic/Latino. The majority of participants were college-educated (college graduates, n = 8; some college, n = 8). Right and left ear PTAs are also included in Table 2, with the mean audiogram displayed in Figure 1. Participants had symmetrical sensorineural hearing loss that on average sloped from mild to severe. One of the 21 participants died unexpectedly during the course of the study, unrelated to study procedures. Data collected during this participant’s time in the study are included. One additional participant became ill and did not complete the final visit of the study protocol.

Table 2.

Participant demographic data.

| Participant | Age | Sex | Race | Education | MMSE | Reported Annual Income | Right PTA | Left PTA | CP (Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 85 | F | White Hispanic | H | 28 | $25,000-$34,999 | 38.3 | 41.7 | N/A |

| 2 | 81 | F | White Non-Hispanic | C | 29 | $50,000-$74,999 | 40.0 | 55.0 | Husband |

| 3 | 80 | M | White Non-Hispanic | C | 27 | Under $5,000 | 31.7 | 30.0 | Friend |

| 4 | 77 | M | White Non-Hispanic | B | 29 | $50,000-$74,999 | 31.7 | 35.0 | N/A |

| 5 | 76 | M | White Non-Hispanic | C | 29 | $75,000-$99,999 | 48.3 | 51.7 | Wife |

| 6 | 78 | F | White Non-Hispanic | S | 28 | $25,000-$34,999 | 48.3 | 40.0 | Daughter |

| 7 | 73 | F | White Non-Hispanic | B | 28 | $50,000-$74,999 | 38.3 | 36.7 | Husband |

| 8 | 84 | F | White Non-Hispanic | S | 27 | $8,000-$11,000 | 30.0 | 35.0 | Daughter |

| 9 | 74 | F | White Non-Hispanic | C | 28 | $50,000-$74,999 | 38.3 | 50.0 | N/A |

| 10 | 72 | F | White Non-Hispanic | C | 27 | $100,000 or over | 10.0 | 25.0 | N/A |

| 11 | 83 | M | White Non-Hispanic | P | 28 | $75,000-$99,999 | 43.3 | 27.0 | Wife |

| 12 | 74 | M | White Non-Hispanic | P | 28 | $50,000-$74,999 | 30.0 | 30.0 | N/A |

| 13 | 74 | M | White Non-Hispanic | C | 28 | $35,000-$49,999 | 41.7 | 40.0 | N/A |

| 14 | 71 | M | White Non-Hispanic | S | 28 | $75,000-$99,999 | 36.7 | 41.7 | Wife |

| 15 | 84 | M | Black | H | 29 | $35,000-$49,999 | 51.7 | 48.3 | Wife |

| 16 | 78 | F | White Non-Hispanic | C | 30 | $12,000-$15,999 | 36.7 | 36.7 | N/A |

| 17 | 80 | F | White Non-Hispanic | P | 29 | $75,000-$99,999 | 45.0 | 43.0 | Husband |

| 18 | 79 | M | White Non-Hispanic | P | 29 | $50,000-$74,999 | 58.0 | 58.0 | N/A |

| 19 | 77 | M | White Non-Hispanic | P | 30 | $100,000 or over | 47.0 | 50.0 | N/A |

| 20 | 76 | F | White Non-Hispanic | B | 29 | $100,000 or over | 31.7 | 38.3 | N/A |

| 21 | 79 | M | White Non-Hispanic | C | 25 | $75,000-$99,999 | 30.0 | 30.0 | N/A |

Note: PTA = Pure tone average at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz; MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; CP = Communication partner participated; F = Female; M = Male; S = Some high school; H = High school graduate/GED; C = Some college or technical school; B = Bachelor’s degree; P = Postgraduate or professional degree; N/A = not applicable.

Figure 1.

The mean audiogram for the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study participants. The right ear is represented with circles while the left ear is represented with crosses. Standard deviations are shown with the error bar indicating the range of hearing thresholds at each frequency.

Communication Partners

Participants were encouraged to ask a communication partner (CP) to join them in the study visits as their inclusion is considered a part of best-practices and supports optimal success with audiology intervention (Manchaiah et al. 2012). The type of CP is listed in the last column of Table 2, with 10 of the 21 participants having a CP consented into the study. The majority were spouses (n = 6), three were daughters and one was a friend. Nine CPs completed the study as one participant mentioned above was lost to attrition and therefore the CP discontinued in the study. Responses from the CPs can serve as surrogacy data, and notable mismatches between the participant and the CP responses can signal problems. Thus, the CPs were asked to provide basic demographic information and complete the International Outcome Inventory – Significant Others [IOI-SO; Noble, 2002] outcome questionnaire, described below. Supplemental Table 2 (ST2) provides the demographic information for the included CPs.

Hearing Aids & Hearing Assistive Devices

Hearing aids, hearing assistive technologies (HATs), and related supplies (e.g., receivers, domes, batteries etc.) were donated in kind by two manufacturers. Phonak LLC donated Audeo V90–312T devices and Starkey Inc donated Z series i110 RIC 312 devices. Devices were equal in advanced digital technology features, including multiple channels with independent compression characteristics, automatic noise reduction, active feedback cancellation, directional microphones, and data logging capabilities. Table 3 displays the devices used by the participants. All participants were fit bilaterally with receiver-in-canal hearing aids coupled to domes. All but one participant was provided with at least one HAT. HATs were used to stream the television to the hearing aids (Starkey’s Surflink Media, Phonak’s TV Link), stream cellphone or other blue-tooth electronics to the hearing aids (Starkey’s Surflink Mobile, Phonak’s ComPilot or ComPilot Air II), stream a remote microphone to the hearing aids (Starkey’s Surflink Mobile, Phonak’s ComPilot or ComPilot Air II with a RemoteMic), and used as a remote to control for volume and/or program adjustments (Starkey’s Surflink Mobile, Phonak’s ComPilot).

Table 3.

Hearing Aids & Hearing Assistive Technologies (HATs) Utilized by participants in the ACHIEVE-Feasibility Study

| Participant | Hearing Aid Manufacturer | Hearing Aid Make Model | Right RMS-D | Left RMS-D | Hearing Assistive Technologies (HATs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 3.7 | 6.0 | Surflink Mobile |

| 2 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 2.5 | 2.4 | Surflink Mobile & Surflink Media |

| 3 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 2.5 | 4.6 | Surflink Mobile |

| 4 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 1.7 | 2.4 | Surflink Mobile & Surflink Media |

| 5 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 3.2 | 6.1 | Surflink Mobile & Surflink Media |

| 6 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 1.4 | 2.8 | Surflink Mobile, & Surflink Media |

| 7 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 3.6 | 3.0 | Surflink Mobile, & Surflink Media |

| 8 | Starkey | Z Series i110 Ric 312 | 5.3 | 4.7 | N/A |

| 9 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 3.0 | 4.1 | Surflink Media |

| 10 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 2.2 | 5.4 | Surflink Mobile |

| 11 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 5.4 | 3.7 | Remote Mic & ComPilot II |

| 12 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 8.7 | 8.3 | ComPilot Air II |

| 13 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 3.7 | 5.0 | Com Pilot, Remote Mic |

| 14 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 3.2 | 1.4 | ComPilot Air II & TV Link II |

| 15 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 5.8 | 6.4 | ComPilot & TV Link II |

| 16 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 5.2 | 1.4 | ComPilot Air II |

| 17 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 4.1 | 6.7 | Remote Mic & TV link II |

| 18 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 6.4 | 7.2 | ComPilot II & TV Link II |

| 19 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 2.2 | 2.2 | ComPilot & TV Link II |

| 20 | Phonak | Audeo V90–312T | 1.4 | 2.2 | ComPilot Air II & Remote Mic |

| 21 | Starkey | Z Series i110 RIC 312 | 1.0 | 4.1 | Surflink Mobile |

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.0) | 4.3 (2.0) |

Note: RMS-D= Root-mean Square-Difference; SD = standard deviation; N/A = not applicable.

We conducted electroacoustic analysis throughout the study to ensure the hearing aids were within ANSI S3.22–2003-specified acceptable tolerances using an Audioscan Verifit 2 hearing instrument verification system. Probe-tube microphone measurements of real-ear output were performed on all participants to verify that a 65-dB SPL input signal matched the National Acoustics Laboratories-Non Linear [NAL-NL2; (Keidser et al. 2011)] prescribed aided output response target within 5 and −8 dB from 250 Hz to 3000 Hz, and within 10 and −13 dB at 4000 Hz tolerances, with minor fluctuation from these ranges due to adjustments requested to accommodate participants’ sound quality preferences or the inability to reach targets due to severity of high-frequency hearing loss. Table 3 shows the final hearing aid adjusted setting with the root-mean-square difference (RMS-D) between the real-ear aided 65-dB SPL input response relative to the NAL-NL2 target at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. Across all participants, the mean RMS-D values were 3.5 and 4.3 for the right and left ears, respectively. With an RMS-D value near 5 considered “on target” (Cox and Alexander, 1990; Mueller, 2005), the majority of participants were fitted suitably with respect to NAL-NL2 targets.

Measures to Assess Expected Outcomes

One objective outcome measure and three subjective outcome measures were utilized to determine if ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention implementation led to expected, disease-specific outcomes. Each is described below.

Speech Recognition in Noise.

We measured speech-in-noise performance using the Quick Speech-in-Noise Test [QuickSIN; Killion et al. (2003)]. The QuickSIN consists of a series of lists of 6 sentences spoken by a woman, mixed with multi-talker speech babble that increases in 5-dB increments with each sentence presentation, for a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) varying from 25 dB to 0 dB. The most homogenous lists were selected for use (McArdle et al. 2006) and a practice list and two test lists were presented with scoring determined by the participant’s correctly recognized target words allowing for the calculation of ‘dB SNR Loss’ using the average performance from the two-test lists.

Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening Version (HHIE-S).

The HHIE-S (Ventry et al. 1983) is a highly reliable (r = .97) 10-item questionnaire that measures perceived hearing handicap. HHIE-S scores can range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater self-perceived handicap. A total score of 10 or greater is suggestive of significant self-perceived hearing handicap. There are 5 items each mapped to emotional and social aspects of hearing handicap, allowing for subscale calculation for each domain. The HHIE-S was administered in a face-to-face format and only total scores were used in the analysis.

International Outcome Inventory (IOI).

The International Outcome Inventory [IOI; (Cox et al. 2002)] is a composite self-report measure of change that is often used in research studies due to its ease of completion, translation in a wide variety of different languages, availability of versions based on respondent and intervention, and published norms (Cox et al., 2003). Three versions of the IOI were used to assess expected outcomes: (1) hearing aid outcomes (IOI-Hearing Aid; IOI-HA; Cox et al., 2000; Cox et al., 2003), (2) alternative interventions (IOI-Alternative Intervention, IOI-AI; Noble, 2002) and (3) CP perception of hearing intervention (IOI-Significant Other, IOI-SO; Noble, 2002). All IOI versions include seven items assessing use, benefit, residual activity limitation, satisfaction, residual participation restriction, impact on others, and quality of life. Each item is scored on an ordinal scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores suggesting better outcomes; thus, the possible range of the total score is from 7 to 40. The IOI measure was administered in a face-to-face format.

Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI).

The COSI (Dille et al. 2015; Dillon et al. 1997) is an open-ended self-report outcome that captures patient-centered goals and allows for measurement of goal attainment. Goals are defined by the individual describing three to five specific listening situations in which s/he would like to improve with hearing intervention, and then ranking the situations in order of importance. After a sustained period of intervention use, using an ordinal scale from one to five, the person estimates the degree of improvement (i.e., how much better or worse) for each situation, and the final communication ability (i.e., the ease of communication) for each situation. The COSI is a reliable clinical outcome measure (improvement rs = 0.73; final ability rs = 0.84) that is correlated with other commonly used measures of hearing rehabilitation benefit (Dillon et al. 1997). COSI goal setting and goal attainment responses were obtained in a face-to-face format. Data were averaged across goals for each participant for both degree of improvement and final communication ability.

Measures to Assess Compliance

Visit completion rates, daily mean hours of hearing aid use through datalogging, and self-reported use of the hearing aids were used to assess compliance with the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention.

Visit Completion Rates.

Visit completion rates were calculated as the percentage of participants completing the visit relative to the number expected to complete the visit.

Data Logging.

Daily mean hours of hearing aid use were collected through hearing aid manufacturer datalogging software (Solheim et al. 2017). The hearing aid software provides the number of hours the hearing aid is turned on in a given time period and divides it by the time period to provide a daily average (Humes et al. 1996).

Self-Reported Hearing Aid Use.

Subjective self-reported use data was collected from both participants and CPs (when applicable) using the first question from the IOI-HI or IOI-SO, which asked “Think about how much you (your CP) used your (their) present hearing aid(s) over the past two weeks. On an average day, how many hours did you (your CP) use the hearing aid(s)?” The response options were: 1= none, 2 = less than 1 hour a day, 3 = 1 to 4 hours a day, 4 = 4 to 8 hours a day, and 5 = more than 8 hours a day.

Measures to Determine Reasonableness of Timeframe

Timeframe of intervention delivery was determined by timing each procedure conducted as part of ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention. For each participant and each procedure, the clinician conducting the procedure recorded start and stop times on a paper source document. Total minutes for the sessions were then summed for each participant, allowing for reporting of mean time (+/− standard deviations) in minutes to complete the session.

Visit Procedures & Instrumentation

The University of South Florida Institutional Review Board approved all recruitment, screening, experimental and compensation procedures prior to any study activities. While enrolled in the study, participants received all audiological services, hearing aids, HATs, and all associated parts and supplies free of charge. In addition, participants kept their hearing aids and HATs after the completion of the study. CPs were not compensated for their participation.

Table 4 provides an overview of the visits, visit time windows, and the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention elements and research procedures completed during each visit. Participants were seen for 7 visits total over approximately 6.5-months, from pre-intervention to post-intervention.

Table 4.

Overview of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility research study visits and mapping of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Elements

| Study Visit | Timeline | ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Elements (Additional Research Procedures italicized) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Screening | Week 0 |

Screening

Consenting Demographic data obtained Generic Baseline Outcome Measures (for timing purposes only) |

| 2. Baseline & Goal Setting | Week 1 (+2 weeks) | Comprehensive Audiological Evaluation ○ Otoscopy ○ Immitance Testing: Tympanometry & Acoustic Reflex thresholds ○ Pure-tone audiometry and word recognition in quiet ○ Unaided Soundfield speech-in-noise testing [QuickSIN; Killion et al. (2003)] Goal Setting ○ COSI Goal Setting Supporting Self-Management ○ Provide I-ACE Module 1: Introduction to I-ACE ○ Watch RLO 1: Introduction to C2Hear Online; orients the viewer to the format and content of the C2Hear RLO series |

| 3. Intervention Session A | Week 2 (+/− 2 weeks) | Hearing Aid Verification, Fitting, & Orientation ○ Electroacoustic Analysis, Fitting with real-ear measurements, & Orientation Supporting Self-Management ○ Review I-ACE Module 1; Introduction to I-ACE ○ Provide I-ACE Module 2: Communication Tactics ○ Watch RLO 2: What to Expect When Wearing Hearing Aids |

| 4. Intervention Session B | Week 4 (+/− 2 weeks) | Hearing Aid Verification & Adjustments ○ Electroacoustic Analysis, Data logging, Adjustments with real-ear measurements if needed ○ Datalogging measured Supporting Self-Management ○ Review I-ACE Module 2: Communication Tactics ○ Provide I-ACE Module 3: Communication in Background Noise ○ Watch RLO 3: Communication Tactics Hearing Assistive Technology Selection ○ Discussion and informal review of COSI Goals to guide selection of HATS |

| 5. Intervention Session C | Week 7 (+/− 2 weeks) | Hearing Aid Verification & Adjustments ○ Electroacoustic Analysis, Data logging, Adjustments with real-ear measurements if needed ○ Datalogging measured Supporting Self-Management ○ Review I-ACE Module 3: Communication in Background Nose ○ Provide I-ACE Module 4: HATs & Resources ○ Watch RLO 4: Phones & Other Devices Hearing Assistive Technology Coupling, Programming & Orientation ○ Coupling, Programming & Orientation Intermediate Outcomes Assessment ○ COSI Goal Attainment ○ IOI-HA ○ IOI-AI (focus on use of Communication Tactics) ○ QuickSIN (Aided, with Hearing Aids) |

| 6. Intervention Visit D | Week 9 (+/− 2 weeks) | Hearing Aid Verification, Re-orientation & Adjustments ○ Electroacoustic Analysis, Adjustments with real-ear measurements if needed; Re-orientation if needed ○ Datalogging Supporting Self-Management; ○ Review I-ACE Module 4: HATs & Resources Hearing Assistive Technology Check & Adjustments ○ Additional orientation and adjustments if needed Outcomes Assessment ○ COSI Goal Attainment ○ IOI-HA ○ IOI-AI (focus on use of HATs & Communication Tactics) |

| 7. Post-Intervention | Week 24 (+/− 2 weeks) | Hearing Aid Verification & Adjustments ○ Electroacoustic Analysis, Data logging, Adjustments with real-ear measurements if needed ○ Datalogging Supporting Self-Management; ○ Review of all I-ACE Modules and C2Hear RLOs if needed Hearing Assistive Technology Verification, Reorientation & Adjustments ○ Additional orientation and adjustments if needed ○ Outcomes Assessment ○ COSI Goal Attainment ○ QuickSIN (Aided, final outcome) ○ HHIE-S ○ IOI-HA ○ IOI-AI (focus on all elements of intervention) ○ IOI-SO ○ Post-Intervention Generic outcome measures (for timing purposes only) |

Note: QuickSIN = Quick Speech in Noise Test; COSI = Client Oriented Scale of Improvement; I-ACE = Individualized-Active Communication Education; HATs = Hearing Assistive Technologies; RLO = Reusable Learning Objects; HHIE-S = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening version; IOI = International Outcome Inventory; HA = Hearing Aids; AI = Alternative Interventions; SO = Significant Other;

Pre-Intervention.

During the pre-intervention stage, the clinician completed informed consent, eligibility screening, intake forms for demographic and hearing health information, and the HHIE-S with each participant (Table 4, Visit 1).

Prior and informative for the intervention stage, participants received a comprehensive hearing evaluation (Table 4, Visit 2). Immittance measures were obtained with GSI TympStar Version 1 middle-ear analyzer, and pure-tone and speech audiometry were completed in a single-walled, IAC Acoustics (40A Classic) sound booth using an Interacoustics Equinox 440 diagnostic, two channel audiometer and E-A-R 3A insert earphones. Pure-tone audiometry was completed using a modified Hughson-Westlake method adjusting the presentation level based on response or lack of response to determine thresholds (Hughson-Westlake, 1944). Air conduction thresholds were measured at octaves from 500 to 8000 Hz. Pure tone bone conduction thresholds were measured at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz with masking used as needed. Also under insert earphones, word recognition in quiet was assessed using NU-6 ordered by difficulty material (Hurley and Sells 2003) presented at a presumed optimal listening level (Guthrie and Mackersie 2009). The QuickSIN test was administered with channel 1 and channel 2 routed to separate Yamaha NS-AW190 speakers. On channel 1 we presented sentences at 00 azimuth using a fixed level of 70-dB SPL, and on channel 2 we presented multi-talker babble at 1800 azimuth, manually adjusting the SNR from 25 dB to 0 dB in 5-dB increments.

Following the comprehensive hearing evaluation, the clinician provided participants with I-ACE materials focusing on understanding hearing loss, goal setting, and adjusting to use of hearing aids, and showed the first C2Hear RLO (Table 4, Visit 2). In addition, participants identified and ranked three individual goals for intervention using the COSI (Dillon et al. (1997); Table 4, Visit 2). The participants were asked to read written I-ACE materials at home, reconsider the goals they had identified, and complete additional questions prompting them to think about difficult listening and communication situations. When available, a CP was included in all discussions and in watching the C2Hear RLO. Participants also were provided with DVDs or links for watching the C2Hear RLOs while at home.

Intervention Visits:

Following the comprehensive hearing evaluation, initial patient education, and goal-setting, participants then returned for hearing aid dispensing, real-ear verification, and orientation (Table 4, Visit 3). With the hearing aids on, the I-ACE Module 1 was reviewed, and goals were confirmed or adjusted based on the participant’s reflections. Manufacturer developed information was provided to participants, the second I-ACE module, focused on Communication Tactics was provided to the participants, and the second C2Hear RLO “What to Expect When Wearing Hearing Aids” was watched.

Participants were then seen approximately two weeks after hearing aid use began for a follow-up visit (Table 4, Visit 4). At this and subsequent visits, a hearing aid post-fitting guided interview was conducted, programming adjustments were made (when necessary), and electroacoustic analysis was completed to ensure hearing aids were functional within the ANSI 2003 tolerances. We additionally recorded mean hourly hearing aid use per day using datalogging information from the manufacturer software. The I-ACE Module 2 exercises on using Communication Tactics were reviewed, and to reinforce their use, the third C2Hear RLO was viewed. These activities led to a discussion of difficulties that a person might experience when listening background noise and allowed for a natural introduction of HATs. Based on this discussion and in consideration of the participant’s COSI goals and unaided QuickSIN performance, a joint decision between the clinician and participant (and CP when applicable) was made with regard to the type of HAT which would be dispensed in the next visit. The participants were then given I-ACE Module 3: Communicating in Background Noise to read and complete exercises before the next intervention visit.

Approximately three weeks after their hearing-aid follow-up visit, participants returned to receive their selected HATs (Table 4, Visit 5). In addition to coupling, programming, and verifying HATs, hearing aids were again checked through a hearing aid post-fitting interview and electroacoustic analysis, and datalogging information was recorded. The responses to the I-ACE Communicating in Background Noise exercises from Module 3 were reviewed, and then as part of the orientation to the individual’s HAT(s), the C2Hear RLO on Phones & Other Devices was viewed. The participant was provided with the last I-ACE module, which provided information about various HATs. We assessed the participants’ short-term expected outcomes through administration of the aided QuickSIN, IOI-HA, and a review of COSI goal attainment.

The final intervention visit (Table 4, Visit 6), included assessment of hearing aids and HATs, review of COSI goal attainment, and completion of the IOI-HA and IOI-AI. The last I-ACE module exercises were reviewed and all of the self-management materials were reviewed and any additional questions posed by either the participant or the CP were addressed. Batteries were supplied to the participants to last over the course of several weeks until they returned for the final research visit and post-intervention assessments.

Outside of the scheduled intervention visits, interim visits during the intervention stage occurred, when necessary, if participants were experiencing any difficulties with the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention, specifically issues with the hearing aids and/or HATs. Twelve participants required interim visits, the majority due to cerumen impaction in the hearing aid receiver or minor requests for hearing aid programming adjustments. During interim visits, the clinician would re-counsel the participant on the proper use, care, and cleaning of the device(s) and make any necessary programming and modifications to the device(s) to rectify the participants’ concerns. If programming changes were required, the clinician completed real-ear probe microphone verification to ensure acoustic functionality.

Post-Intervention:

Participants returned for their post-intervention session (Table 5, Visit 7) around 24 weeks or 6-months, after the initial audiologic evaluation (i.e., the onset of the intervention stage). During the post-intervention stage, we assessed the objective expected outcomes, including aided speech in noise performance and compliance with the intervention. We additionally assessed the subjective expected outcomes by administering the final COSI goal attainment and the IOI-HA, IOI-AI, IOI-SO (if applicable), and HHIE-S.

Table 5.

Overview of Results Used to Answer Feasibility Questions.

| Pre-Intervention | Intervention | Post-Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | Visit 5 | Visit 6 | Visit 7 | |||

| (n = 21) | (n = 21) | (n = 21) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 19) | |||

| Assessment of Expected Outcomes | |||||||||

| QuickSIN (dB SNR Loss) (SD) | 11.8 (6.4) | 6.8 (4.7) | 5.3 (4.6) * | ||||||

| HHIE-S (SD) | 25.1 (8.2) | 6.1 (5.1) * | |||||||

| COSI Median Response (1–5) | |||||||||

| Degree of Change | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Final Ability | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| International Inventory Mean Total Score (SD) | |||||||||

| IOI-HA | 30.6 (2.7) | 30.4 (3.7) | |||||||

| IOI-AI | 27.9 (2.8) | 27.4 (2.9) | |||||||

| IOI-SO | 31.7 (2.6) | ||||||||

| Assessment of Compliance | |||||||||

| Visit Completion (%) | 100 | 100 | 95.2 | 100 | 100 | 90.4 | |||

| Binaural Data Logging in hours (SD) | 8.1 (4.0) | 8.0 (3.8) | 7.6 (3.4) | 7.3 (3.4) | |||||

| International Inventory Median Response for Question 1 (1–5) | |||||||||

| IOI-HA | 5 | 5 | |||||||

| IOI-SO (n=9) | 5 | ||||||||

| Assessment of Reasonable Timeline | |||||||||

| Mean (minutes) | 59.5 | 75.0 | 31.5 | 50.0 | 35.5 | ||||

| Minimum (minutes) | 47 | 65 | 28 | 28 | 27 | ||||

| Maximum (minutes) | 72 | 85 | 35 | 72 | 54 | ||||

Note: SD = Standard Deviation,

= statistically significant change from pre-intervention to post-intervention; QuickSIN = Quick Speech in Noise Test; ; HHIE-S = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening version; COSI = Client Oriented Scale of Improvement; I-ACE = Individualized-Active Communication Education; HATs = Hearing Assistive Technologies; RLO = Reusable Learning ObjectsIOI = International Outcome Inventory; HA = Hearing Aids; AI = Alternative Interventions; SO = Significant Other;

Data Analysis

It was not the purpose or design of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study to determine treatment effectiveness of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention, but rather to evaluate the feasibility of ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention and refine the manual guiding the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention delivery; thus, reported here are descriptive statistics as percentages, means, and standard deviations (SD) (Eldridge et al. 2016). To inform whether participants obtained expected outcomes, two paired sample t-tests were completed comparing pre-intervention QuickSIN and HHIE-S results to post-intervention results. We additionally assessed the relationship between self-reported hearing aid use (as recorded on the IOI-HA) and objectively measured hours of hearing aid use (via datalogging) by conducting Spearman rank-order correlations. All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS (version 25.0).

ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Refinement and ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Manual Revisions

Throughout the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study, revisions and clarifications were tracked in an electronic version of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual. Following NIH guidelines on manual revisions, the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual served as a history of the project, documenting the time and nature of any changes in procedures (Knatterud et al. 1998; National Institute on Aging). Areas of the manual that needed additional instructions were highlighted, images were gathered, and informal comments from both the study clinician, supporting study staff, and participants were logged for later consideration.

Results

The purpose of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study was to assess if the manualized hearing intervention elements and initial ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual was sound with respect to (1) expected outcomes, (2) compliance with the intervention, (3) and reasonableness of timing. Table 5 provides an overview of the data that were used to answer these three questions.

Expected Outcomes

Speech Recognition in Noise.

Table 5 reports the mean QuickSIN performance (dB SNR Loss) collected unaided at Visit 2 and aided at Visits 5 and 7. Mean unaided QuickSIN performance was 11.8 dB SNR Loss (n=21), consistent with a severe speech in noise recognition deficit. Mean aided QuickSIN performance decreased to 6.8 dB SNR Loss at Visit 5 (n=20) to 5.3 dB SNR Loss at Visit 7 (n=19), consistent with an improvement in speech recognition in noise ability. A paired samples t-test was performed to compare participants’ pre-intervention unaided QuickSIN performance at Visit 2 to aided post-intervention performance at Visit 7. There was a significant improvement on performance post-intervention, t(18)=4.2, p=0.0003. In the aided condition at Visit 7, participants had mean QuickSIN performance of 5.3 dB SNR (SD = 4.6), with a moderate effect size of (d) = 1.03 standard deviations relative to the unaided performance.

Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly-Screening Version (HHIE-S).

A mean pre-intervention HHIE-S total score of 25.1 (SD = 8.2) suggested that participants, overall, experienced a significant degree of self-perceived hearing handicap before receiving the comprehensive hearing intervention (Table 5). The mean post-intervention HHIE-S total score was 6.1 (SD = 5.1). We conducted a paired samples t-test to determine whether mean HHIE-S scores improved from pre- to post-hearing intervention. Results indicated that participants experienced a significant reduction in self-perceived hearing handicap at Visit 7, t(18)=9.3, p=0.0002, with a large effect size of (Cohen’s d) = 2.14 standard deviations relative to pre-intervention. Individual participant data including social and emotional sub-scale, total score, and severity ratings at pre- and post-intervention are provided in Supplemental Table 3 (ST3).

International Outcome Inventory (IOI).

Table 5 displays the total score means and standard deviations for each version of the IOI questionnaire collected at various visits. The mean IOI-HA score collected at visit 5 (30.6) was essentially unchanged at Visit 7(30.4). Likewise, the mean IOI-AI total score measured at Visits 6 was essentially unchanged compared to Visit 7 at 27.9 and 27.4, respectively. The IOI-SO, collected solely at Visit 7, had a mean total score of 31.7, which was close to the participants’ self-ratings on both the IOI-HA and IOI-AI. The Supplemental Tables 4a-e (ST4a-3e) provides the individual data for each question and the total scores for each questionnaire at each collection time point.

Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI).

Table 5 provides the median COSI responses collected across the various visits. Post-intervention COSI results suggested that participants experienced improvement for each ranked goal and an increase in the degree of final ability following the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention. Participants largely rated degree of change in between “4-Slightly better” (n = 15) and “5-Much better” (n = 2) for all three goals and rated their ability to listen in the specific situation between “4 - Most of the time (75%)” (n = 6) to “5 - Almost always (95%)” (n = 10) for all three listening goals. No participant indicated that Degree of Change was “worse” or “no better” after intervention for any goals.

Intervention Compliance

Recall that three forms of data were used to inform compliance with the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention including completed visits, data logging and subjective self-report of usage. Each of these data sets are reported followed by the correlation between objective data logging and subjective usage report.

Completed Visits.

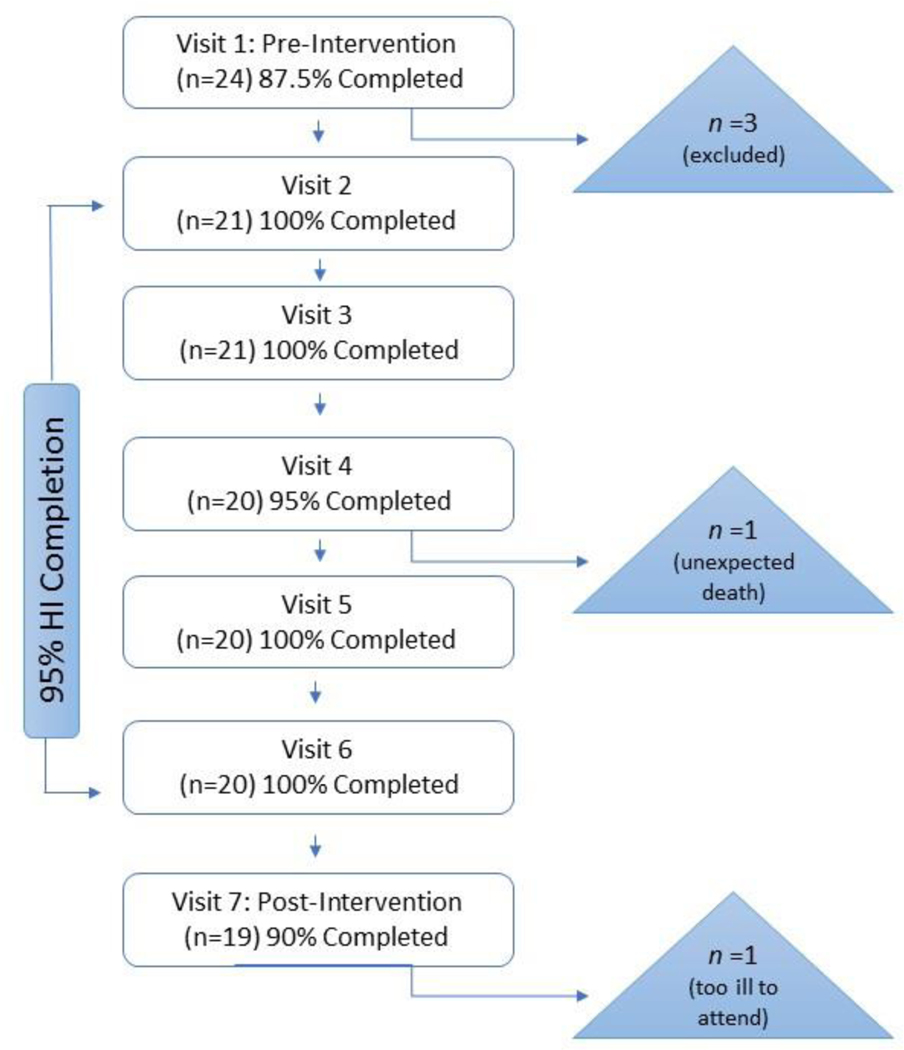

Visit completion rates, reported in percentages, are listed in Table 5. In addition, Figure 2 displays the flow of participant recruitment and enrollment from pre-intervention to the final post-intervention visit. Overall, we saw high participant completion rates (90–100%) for all study visits. Recall that of the 24 recruited participants, 21 participants were eligible for the study and proceeded onto Visit 2. There were 21 participants that completed Visits 1 through 3; however, one participant died unexpected and unrelated to the study before Visit 4. Another participant completed all intervention visits but was too ill to travel to the final post-intervention assessment (Visit 7). In sum, 20 of the 21 eligible participants completed all intervention visits (95.2%), with 19 of the 21 participants completing all the study visits (90.4%), including the 6-month post-intervention visit.

Figure 2.

Flow Chart demonstrating completion of research visits. Completion rates are provided at each visit of the total number of participants eligible to complete the visit. Note: HI = Hearing Intervention

Data Logging & Subjective Usage Report.

Both mean objective datalogging hours and subjective median reported International Inventory responses are shown in Table 5. To objectively evaluate hearing intervention compliance, we first analyzed hearing aid datalogging using the manufacturer software. Mean bilateral hearing aid use logged across research Visit 4 through Visit 7 was 7.8 hours per day (range 3.8 – 15.2 hours). We next evaluated self-reported hours of hearing aid use collected from the IOI-HA and IOI-AI. Participants’ median self-reported hearing aid use, collected from the IOI at Visits 4 and 7, was 5, indicating greater than 8 hours of use per day. The median reported HAT usage, collected at Visits 5 and 7, was 3, or “4 to 8 hours” per day. Additionally, the median CP report for participant usage, collected at Visit 7, was 5, indicating the hearing aids were worn “greater than 8 hours”.

A Spearman correlation was calculated to examine the relationship between objective and subjective daily hearing aid use. Significant moderate correlations between datalogging measurement and self-reported daily use were found at both Visit 5, rs(18) = 0.51, p=0.02 and Visit, rs(17) = 0.63, p=0.004 indicating that while participants were somewhat consistent with self-reported hearing aid use compared to objective datalogging, there was not a perfect relationship.

Reasonableness of Timeframe for Delivery of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention

To determine if the elements completed at each of the intervention visit could be delivered within a reasonable timeframe, the times for each procedure and overall visit duration were documented. Table 5 shows the mean, minimum, and maximum durations per visit. Visit durations ranged from 27 to 85 minutes. On average, the longest session was Visit 3, which included the hearing aid fitting and orientation.

Identified Areas for Improvement to the Manualized ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Elements and ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Manual

Revisions and clarifications were tracked in an electronic version of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual following NIH guidelines on manual revisions (Knatterud et al. 1998; National Institute on Aging). Areas of the manual that needed additional instructions were highlighted, images were gathered, and informal comments from the study clinician, supporting study staff, and participants were logged for later consideration.

It was noted that the manual could be improved by making it more real-time user friendly and by bringing attention to items often forgotten or needing to be repeated. Commentary about the manualized procedures included that the firmly-structured intervention in clinical settings removed some aspects of a person-centered approach to audiology service provision. And, concern was raised about the participants in the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study having higher education (i.e., majority reported some level of college education). Even with a higher-level education cohort than expected, several participants commented on the length and complexity of the written materials provided. In the same vein, it was noted that in the future multi-site ACHIEVE trial, there would be varying degrees of health literacy and more diverse clinical settings and patient populations. This was considered and the need for revised materials were then sought out.

Although the written materials were commented on by the participants as being cumbersome, the participants reported they enjoyed viewing the C2Hear RLOs, but reported difficulty understanding and following along with the British narrator’s accent. It was also commented that the RLOs could be improved if they showed the same hearing aids and HATs that were provided to the participants. In general, the hearing aids and HATs were well received by both the participants, CPs, and clinicians. Some of the hearing aids did not meet the NAL-NL2 fitting criterion due to preference adjustments or unattainable targets and clinicians reported the need for customized ear tips (earmolds around receivers or in-the-ear hearing aids) for better fitting and acoustic performance. Although study clinicians reported successful use of the manufacturer fitting software, the clinicians commented that the level of detail in the manual required for step-by-step fitting procedures was difficult to implement with two manufacturers. A need to review each manufacturer’s unique software and terminology was identified since in the future applications it would be important for clinicians to efficiently follow the step-by-step fitting procedures.

Discussion

ACHIEVE-Feasibility: Expected Outcomes, Intervention Compliance, Reasonableness of Timeframe

The purpose of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study was to evaluate the implementation of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention to confirm the ability for the intervention to yield expected outcomes, identify concerns with compliance with the intervention, and determine the practicability of intervention delivery within the resources available. The data collected as well as the qualitative responses from those delivering the intervention and those receiving the intervention informed the implementation feasibility. Overall the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study demonstrated that the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention was feasible in terms of expected disease-specific outcomes, intervention compliance, and timeframe reasonableness. Regarding objective expected outcomes, mean participant performance on speech-in-noise recognition improved approximately 6.5 dB from pre-intervention (unaided) to post-intervention (aided). This aided performance is comparable to previous studies investigating unaided versus aided conditions [e.g., Valente et al. (1995); Nabalek et al. (2004)].

ACHIEVE-Feasibility study participants also experienced significant and clinically meaningful subjective improvements as a result of the intervention. We saw a marked decrease in post-intervention HHIE-S scores, with 15 of the 21 participants reporting no significant self-perceived hearing handicap at the end of the study. The mean post-treatment score was 6.1, which is in line with the expected outcomes following a sustained period of hearing intervention use (e.g., Ferguson et al. 2017). In addition, it was observed that 15 of the 21 participants reported no significant self-perceived hearing handicap at the end of the study. Similarly, all three versions of the IOI (i.e. -HA, AI, SO) had overall total scores that were high and in line with expected post-intervention outcomes. The IOI-HA results suggested that participants experienced subjective improvement as a result of the intervention, with mean scores across the seven questions consistent with normative values for individuals with similar degrees of hearing loss (Cox et al. 2003). Finally, in line with our expected outcome, nearly all participants reported improved listening ability in their prioritized hearing goals (n = 19), as reported on the COSI (Dillon et al. 1997). As a result of the findings the disease-specific outcome measures were included in the ongoing ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial, as it was determined that they provide important information that can both guide intervention decisions and affirm that the hearing intervention leads to expected proximal disease-specific results.

A high rate of visit completion, datalogging results, and self-reported hearing aid use indicated successful compliance with the intervention. With only two participants who met inclusion criteria lost to follow-up or attrition, the rates of intervention visit and study completion were high and respectable compared to other trials requiring longitudinal assessment commitments (For systematic review of retention rates see, Robinson et al., 2007). As reported above, the mean bilateral hearing aid use logged across visits greater than 7-hours per day which is consistent with previous studies investigating average daily hearing aid use our mean usage as above 7 hours per day (Laplante-Levesque, et al., 2014; Gaffney, 2008; Mäki-Torkko et al., 2001). Datalogging results indicated that hearing aids were worn, on average, just under eight hours per day, within the lower range of use compared to previous studies. However, inexperienced hearing aid users tend to utilize hearing aids for fewer hours a day compared to experienced users [e.g., Cox et al. (2003)], and we expect to see longer use times in the larger ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial as participants become more acclimated to their hearing aids. It should be noted that provision of the hearing intervention at no cost to the participants may have influenced compliance, but since the future multi-site larger ACHIEVE trial would also be providing devices/services in kind this is not considered a limitation of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study, but rather confirmation to implement this methodology in the future trial will lead to similar successful adherence rates.

We additionally found a moderate correlation between datalogging and self-reported hearing aid use. Although self-report has been reported to overestimate hearing aid use (for example, see Laplante-Levesque et al., 2014), consistent relationships between objective and subjective hearing aid use have been previously demonstrated, and self-reported daily use has been found to be a reliable and robust measure across time (Humes et al. 1996; Killion et al. 2003). Participants were somewhat consistent with self-reported hearing aid use compared to objective datalogging. Therefore, it was confirmed that both self-report and datalogging would be maintained as an indicator of compliance for the larger ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial.

The mean duration for each visit ranged from approximately 31 minutes (Visit 4) to 75 minutes (Visit 3), and were comparable with previous estimates of appointment lengths for delivery of person-centered audiologic care with a CP involved (Ekberg et al. 2014). As expected, incorporating participants’ individual values, needs, and goals for treatment to a manualized intervention depended on many factors, with some participants requiring additional time compared to others. We found that the hearing aid fitting and orientation appointment tended to be the most time- and labor-intensive regarding the efforts of the clinician. Participants not only received basic informational counseling regarding care and use of their devices, but also reviewed I-ACE self-management materials with the clinician as well as viewed a C2Hear RLO during the visit. Finally, the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention was designed as a gold-standard, evidence-based hearing intervention, therefore we included procedures not routinely performed in audiology practice. For example, a recent report found that only 30% of surveyed audiologists consistently utilized probe microphone measurements when fitting or adjusting hearing aids (Leavitt et al. 2017), and even when probe microphone measures are used, matches near prescriptive targets are frequently not met (Aazh et al. 2014).

Although efficacy was not a goal of the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study, the effects of the intervention on self-perceived hearing impairment, speech recognition in noise, and quality of life were positive and encouraging. These findings were also supported by a successful subsequent randomized pilot study (ACHIEVE-Pilot Study; Deal et al., 2017). Concluding both ACHIEVE-Feasibility and ACHIEVE-Pilot, the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention and associated Manual were then ready for final revisions and refinement before being used in the current larger multisite ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial. Implementation of these activities and refinement of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention is described next.

Implementation of ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention Elements Improvements and Associated Manual Refinement

The results of ACHIEVE-Feasibility study, and subsequently ACHIEVE-Pilot study, allowed for further refinement of the intervention and accompanying manual in order to optimize both for future use in the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial. Modifications implemented throughout ACHIEVE-Feasibility and ACHIEVE-Pilot studies resulted in an updated ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual to fit the larger multi-site ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial recruitment and completion timelines. This version of the manual includes one pre-intervention visit, four intervention visits, and six post-intervention visits that occur biannually for 36 months (for full ACHIEVE trial protocol see Deal et al., 2018).

The electronic ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual was designed to be used by the study audiologist in real-time while completing all the components of the intervention. To help with real-time use, icons were implemented depicting various activity types throughout the manual to facilitate use of the step-by-step instructions. The icons brought attention to when new procedures started and highlighted important reminders or alerts (for example of icons, see supplemental document with examples from the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual of procedures). Each procedure includes sections highlighting the expected timing, equipment needed, clinician prompts and scripts, and specific actions to be completed. The specific actions to be competed are separated with “Do This” and “Say This” steps to help the audiologist easily and efficiently complete each action.

Based on feedback from ACHIEVE-Feasibility and ACHIEVE-Pilot studies, a critical issue identified was that using a manualized, firmly-structured intervention in clinical settings removed some aspects of a person-centered approach to audiology service provision. The solution to this issue was to create an intervention manual that, although structured, also allowed for individualization and responsiveness to ever-changing life circumstances and participant experiences. Although initial ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention and the associated manual used to complete the ACHIEVE-Feasibility study accomplished several goals with regards to feasibility, compliance, timeliness, and a positive efficacy signal within short-term goals, there were many identified areas that needed to be addressed for the future larger multisite ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial.

One element of the original ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention, vetted in the feasibility and pilot studies, needing revision was the type and route of self-management education used. We refined both the I-ACE and C2HEAR RLOs to better suit the needs of the future larger multisite ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial. We first used the I-ACE written materials as an “informational template” to develop new self-management materials that take into account varying degrees of health literacy and the diverse clinical settings and participant populations. The new materials, referred to as the ACHIEVE Hearing Toolkit for Self-Management© (Arnold et al., 2019), allow for full coverage of the topics discussed in the I-ACE, but deliver these topics in brief, graphic-based modules. The different Toolkit modules are designed to be selected and emphasized based on the participant’s specific needs, and include: understanding hearing loss and setting goals, communicating in background noise, TV listening, using communication strategies, places of worship, telephone listening, hearing assistive technologies, and common psychosocial adjustment issues related to hearing loss.

Overall, both ACHIEVE-Feasibility and ACHIEVE-Pilot participants anecdotally enjoyed viewing the C2Hear RLOs, but reported difficulty understanding and following along with the British narrator’s accent. Therefore, we “Americanized” the RLOs by substituting British English colloquialisms for American English terms, and re-recording the narration using American English speakers, while simultaneously maintaining the majority of content from the original British versions (Oree et al., 2018). The Hearing Loss Toolkit for Self-Management© and the Americanized C2HEAR RLOs are the focus of the educational and supportive materials utilized in the current larger multisite ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial.

In addition to the changes in educational and self-management materials a few changes were also made regarding the hearing aids and other hearing assistive technologies to be used in the larger multisite ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial. Specifically, to improve ease of use of the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual in real time, a single hearing aid manufacturer was selected which also reduced any potential confounding factors associated differences in hearing aids and programming. Narrowing to a single manufacturer allowed the ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual to include more extensive detail on procedures such as real-ear and electroacoustic analysis using the specific devices that audiologists would be using in ACHEVE randomized controlled trial. The inclusion of earmolds and in-the-ear hearing aids were added to the fitting options as well to reduce any difficulty meeting fitting target and increase participant retention and comfort. The refined and revised ACHIEVE-Hearing Intervention manual including the new self-management materials, richer instructions, icons, images specific to the devices, equipment, mirroring the clinical settings at each study site was then ready for use in the larger ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial currently underway.

Conclusion