Abstract

Family prevention programs that enhance mental health, wellness, and resilience—while simultaneously addressing violence and alcohol and other drug (AOD) abuse—among Indigenous families are scarce. This gap in culturally grounded and community-based programs creates a critical need to develop and evaluate the efficacy of such prevention programs. This article fills this gap, with the purpose of describing the structure and content of the Weaving Healthy Families (WHF) program, a culturally grounded and community-based program aimed at preventing violence and AOD use while promoting mental health, resilience, and wellness in Indigenous families. The focus then turns to how to approach this process of developing and implementing the program in a culturally grounded and community-based way.

Keywords: Native American, trauma, violence, alcohol and other drug use, substance abuse, community-based participatory research, WHF program development, clinical trials

As part of a broader context of settler colonial historical oppression, U.S. Indigenous peoples (to whom the scope of this inquiry is limited) tend to be overburdened and overexposed to risks for co-occurring mental health conditions, including depression, suicide, alcohol and other drug (AOD) use disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and violence (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019). The empirically informed Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence (FHORT) was built upon long-term relational with Indigenous peoples characterized by deep listening and long-term collaboration to fill the gap in culturally based frameworks to redress disparities resultant from historical oppression while promoting culturally grounded strengths and resilience (Burnette & Figley, 2017; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019).

Using the integrative Two-Eyed Seeing approach that builds upon the strengths that may be present across Indigenous and mainstream ways of knowing (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019), the FHORT situates contemporary psychosocial challenges with respect to their structural, settler colonial roots (Burnette et al., 2020; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). The FHORT expands upon the Two-Eyed Seeing approach by centering and accounting for the power differentials that have relegated Indigenous knowledge systems as inferior and aims to redress such power differentials. The FHORT conceptualizes a holistic balance of risk and protective factors across multiple ecological levels to predict whether and how people experience resilience, transcendence, and wellness (i.e., balance harmony across physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health) after encountering adversity (Burnette & Figley, 2017). Historical oppression includes both historical and contemporary experiences of chronic, pervasive, and intergenerational oppression, which may be normalized, imposed, and internalized, factors that exacerbate and perpetuate challenges (Burnette & Figley, 2017).

Chronic exposure to settler colonial historical oppression poses a risk for wellness, health, and well-being (Gone & Trimble, 2012). Ka’apu and Burnette’s (2019) systematic review focusing on risk and protective factors related to mental and behavioral health among U.S. Indigenous peoples indicated historical oppression increased their risk for mental health problems—along with exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV), child maltreatment, trauma (i.e., PTSD risk), and adverse childhood events (ACE). Moreover, AOD use disorders increased risk for depression and other mental and physical health problems (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019). Social support, resilience, higher income, supportive families and communities, and engaging with culture, in contrast, were protective factors against mental and physical health inequities (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019).

Centuries of exposure to insidious and institutionalized historical oppression heighten Indigenous peoples’ risk for AOD abuse across the life course, which drives psychosocial health inequities, greater mortality rates, violence, and trauma (Klostermann et al., 2010; Moran & Bussey, 2007). Despite primary drivers of mental health conditions being co-occurring violence and AOD abuse (Breiding et al., 2014), prevention programs seldom address violence and AOD abuse simultaneously, nor do they use a family-focused or community-based approach (Komro et al., 2022).

Programs that fail to integrate culturally relevant factors and the co-occurring problems of violence and AOD abuse in families ignore important drivers of Indigenous health disparities (Dixon et al., 2007; Gone & Trimble, 2012; Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014). Despite culturally specific mental health programs being 4 times more effective than nontargeted programs (Griner & Smith, 2006), less than one fifth of AOD programs offer Indigenous peoples culturally specific services (Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014). Family approaches to AOD abuse prevention have been shown to be 2 to 9 times more effective than child-only approaches (Tutty, 2013), yet the majority of Indigenous AOD programs focus exclusively on youth (Dickerson et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2007). A lack of family member involvement in violence and AOD abuse prevention programs ignores Indigenous peoples’ preferences for inclusive family and community-driven approaches (Burnette & Sanders, 2017) and exacerbates psychosocial inequities (Kumpfer et al., 2002; Novins et al., 2012).

Introduction and Overview

Family prevention programs that enhance Indigenous mental health, wellness, and resilience (i.e., the positive adaptation from adversity; Kirmayer et al., 2009)—while simultaneously addressing violence and AOD abuse—among Indigenous families are scarce (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014). This gap in culturally grounded and community-based programs to prevent violence and AOD abuse in families creates a critical need to develop and evaluate the efficacy of such prevention programs. This article fills a gap in understanding and provides examples of a family and culturally grounded prevention program by describing the Weaving Healthy Families (WHF) program (In Choctaw, Chukka Auchaffi’ Natana Program), while illuminating its culturally and community grounded development and implementation. The overarching research questions that guide this inquiry include the following:

Research Question 1: What is an example of an empirically informed, culturally grounded, and family-focused program that holistically promotes Indigenous mental health and wellness while preventing violence and AOD abuse?

Research Question 2: How can people approach the process of program development and implementation in a culturally grounded and sustainable way?

The WHF is a culturally grounded and community-based program aimed at preventing violence and AOD use while promoting mental health, resilience, and wellness in Indigenous families. A culturally adapted version of the Celebrating Families! program (National Association for Children of Addiction, n.d.), the development, testing, and implementation of the WHF program followed an integrative Two-Eyed Seeing approach to intervention research (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019). The WHF program was developed through a decade of culturally grounded community-based participatory research (CBPR; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019) with the original Celebrating Families! (National Association for Children of Addiction, n.d.) and the Wellbriety & Celebrating Families! version of the program developed in partnership by White Bison (2021), a Native American-led non-profit organization (White Bison, 2021).

Development of the WHF program was guided by Whitbeck’s (2006) five-stage process for AOD program adaptation with Indigenous programs: (a) attaining familiarity through broad risk and protective factors, (b) identifying culturally specific risk and protective factors, (c) translating culturally specific risk and protective factors to a cultural context, (d) developing measures of risk and protective factors specific to someone’s culture, and (e) adapting and pilot testing the WHF program (McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019; McKinley & Theall, 2021; Whitbeck, 2006). Because Stages 1 to 4 and pilot results have been focal in other works (e.g., McKinley, Figley et al., 2019; McKinley & Theall, 2021), the scope of this article is limited to adaptation and implementation components of Stage 5 (see Supplementary Materials for a synopsis of prior stages).

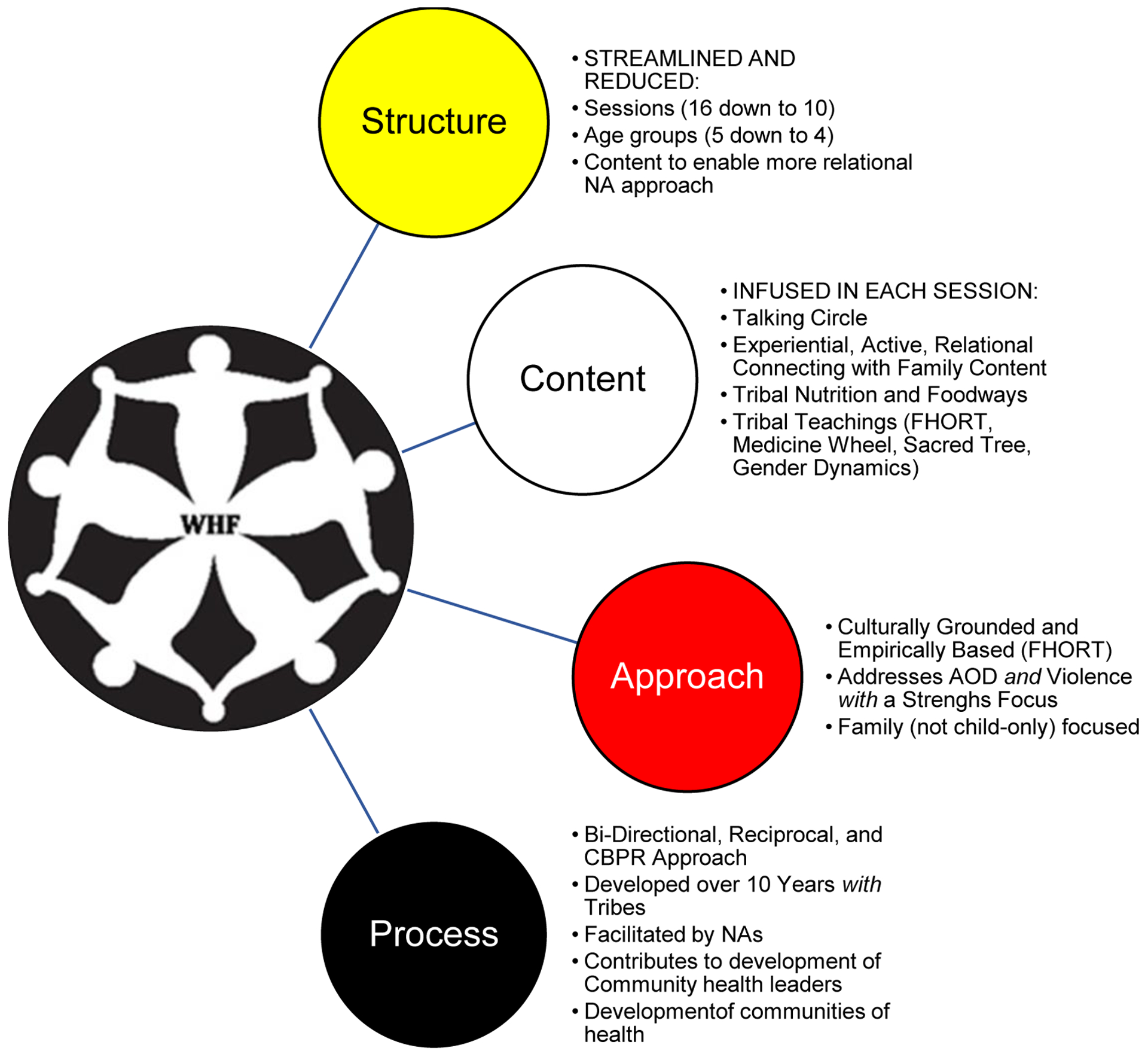

Figure 1 displays examples of how the WHF program incorporates Two-Eyed seeing by building upon strengths of Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing within its structure and content (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019). The program addresses glaring gaps in prevention programs by holistically focusing on (a) violence and AOD abuse prevention; (b) being family and culturally grounded; and (c) being collaboratively developed (through CBPR, with guidance from Community Advisory Boards [CABs], and facilitated by tribal community health representatives [CHRs]).

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the Contributions to the Approach, Process, Structure, and Content of the WHF Program.

Note. The WHF is distinct from other AOD and violence prevention programs throughout its approach, process, structure, and content by (a) focusing on AOD use and violence prevention (rather than either or) holistically while promoting resilience and wellness; (b) incorporating a whole-family approach (rather child or adult only) to violence and AOD abuse prevention; (c)infusing the culturally and empirical grounded FHORT and tribal teachings throughout the program; (d) integrating recommendations for research that benefits Indigenous communities, including bi-directional, reciprocal, and community-driven CBPR (Around Him et al., 2016), with CAB decision-making, facilitation by Indigenous CHRs, and community participation, input, and training institutionalized throughout all aspects of research (McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019); (e) streamlining and simplifying structure and content to offset participant and facilitator/organization burden and burnout (e.g., number of sessions reduced by almost 40%, reducing the number of age groups from 5 to 4 total); and (f) taking a Two-Eyed Seeing approach by retaining core components of the unadapted mainstream intervention while infusing cultural content (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019) throughout institutional structures, content, and processes. FHORT = Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence; AOD = alcohol and other drug; CBPR = community-based participatory research; WHF = Weaving Healthy Families; CAB = Community Advisory Board; CHR = community health representatives; NA = Native American(s).

The incremental and systematic process of culturally adapting WHF programs simultaneously provides the following benefits to the community (McKinley & Theall, 2021): (a) immediate or tangible benefits (i.e., supplementary income for families and CHRs); (b) intermediary benefits (i.e., promoting mental health, wellness, and family skills while preventing violence and AOD use); and (c) long-term benefits (i.e., creating Indigenous health leaders). Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the article’s focus and displays examples of key changes made in the process developing the program structure, content, approach, and process. The focus then turns to how to approach this process or how to develop and implement the program in a culturally grounded and community-based way (see Figure 1).

The WHF program was developed with input and participation of over 1,000 tribal members across the life course and across tribal contexts using Indigenous storytelling approaches to identify risk and protective factors related to AOD use and violence prevention. Indigenous stakeholders and the CAB identified and selected the Celebrating Families! curriculum for adaptation. The original program was found to reduce AOD abuse, promote unity, address mental health problems, and strengthen parenting skills (National Association for Children of Addiction, n.d.) and had already been adopted by some Indigenous communities with a cultural overlay (White Bison, 2021). However, Indigenous partner sites described critical barriers to successful program implementation and completion related to its length, feasibility, and integration of cultural components. This cognitive-behavioral evidenced-informed program uses a support group model to prevent AOD abuse and family violence by targeting key risk and protective factors identified in preliminary research (see Supplemental Materials and McKinley, Figley et al., 2019, for complete description).

The purpose of this article is to provide a roadmap of the structure, content, approach, development, and implementation of this WHF program, a culturally grounded program facilitated by Indigenous CHRs and developed with the authors and CAB in long-term CBPR. The program represents a culmination and extension of Two-Eyed Seeing approaches to culturally grounded research (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019) with Indigenous communities outlined in “A Toolkit for Ethical, Culturally Sensitive, and Rigorous Research” (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). References to how toolkit research strategies were integrated are italicized throughout this article (see Burnette et al., 2014, and McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019, for full descriptions). This article first outlines the WHF program and its key elements before describing its adaptation and implementation. CAB members and CHRs who helped develop and facilitate the program provide personal reflections about what the WHF program and its development means to them.

Introduction to the WHF Program Structure and Content

The WHF program is a family-focused, skill building, psychoeducational program targeting AOD use and violence prevention while promoting resilience, wellness, and mental health. Although the original Celebrating Families! program may be used either for prevention or early intervention, the WHF was developed and evaluated as a universal prevention program (Hawkins et al., 2004). Although all household members participate, the WHF program has focused currently on Indigenous families with at least one child aged 12 and above to enable assessment of the key outcomes of AOD use.

In honor of agreements made with partnering tribal communities and in alignment with the toolkit strategy to honor confidentiality (which can be inclusive of individuals, families, and communities), the names of the communities have remained confidential (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). The rationale for taking a universal preventive approach stemmed from the toolkit strategy, enable self-determination. Cultural insiders have emphasized the importance of approaching work in ways that avoid stigma, but rather reinforce cultural strengths (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Universal prevention programs reach broader populations and can prevent stigma associated with targeted or deficit-focused programs (Hawkins et al., 2004). The WHF program frames settler colonial historical oppression as a structural determinant of health that places Indigenous peoples at heightened risk for AOD misuse, violence, and mental health conditions (Ka’apu & Burnette, 2019; Klostermann et al., 2010; Moran & Bussey, 2007) and aims to offset risk through promoting family resilience and community healing.

The structure of the WHF program rein-forces cultural strengths by focusing on the whole family, including extended family systems (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019; McKinley, Miller Scarnato, et al., 2019). Whole families attend 10, 2.5-hr sessions focused on select topics, which include time with their family and sharing information in developmentally tailored peer age groups. Each session begins with a family meal, which enhances Indigenous family resilience and wellness by promoting rituals, communication (Burnette et al., 2020), and Indigenist foodways. Indigenist is a term coined by Walters and Simoni (2002) focused on Indigenous peoples’ liberation and empowerment while acknowledging the structural context of historical oppression that continues to disrupt Indigenous peoples’ connection to land and lifeways. Foodways encompass cultural meaning, practices, and values around foods (Ruelle & Kassam, 2013).

After eating with their family, each participant joins one of four developmental age groups: (a) parents, (b) adolescents aged 12 to 17, (c) youth aged 8 to 11, or (d) youth aged 5 to 7. Childcare is provided to children younger than age 5. Each age group receives lessons on the same topic in developmentally tailored ways. Session topics aim to promote (a) alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) prevention; (b) violence prevention; (c) emotional regulation; (d) mental wellness and healthy living; (e) positive communication; (f) setting positive goals; (g) promoting tribal protective factors while reducing risk; (h) making positive choices and problem-solving; (i) setting healthy boundaries and nurturing healthy relationships; and (j) promoting resilience, among others (McKinley & Theall, 2021). After the lesson ends, participants rejoin their families for activities that reinforce session topics and foster family connection.

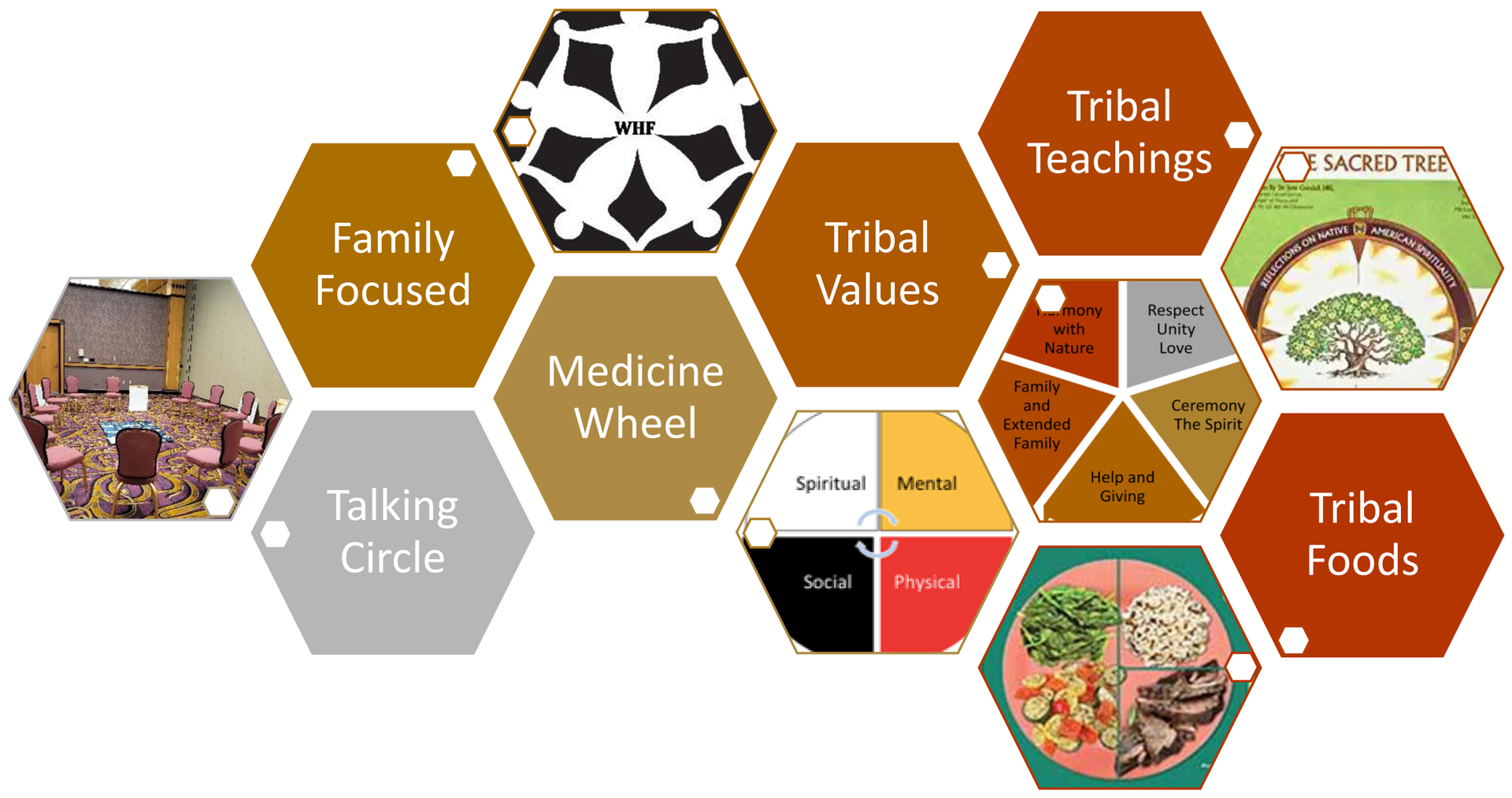

The WHF program incorporates key elements of the original Celebrating Families! program and follows the toolkit strategy to enable self-determination and to allow for fluidity and flexibility (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Based on feedback from pilots with other Indigenous communities who used the original program, the WHF program is a shortened and streamlined program because the original program was (a) difficult to facilitate, (b) content heavy, and (c) left little room for the relational component valued in Indigenous communities (Burnette & Figley, 2017). The WHF follows the toolkit’s recommendation to use a tribal perspective through development and integration of cultural components, such as a talking circle; medicine wheel; FHORT; tribal nutrition and foods; tribal values; and tribal teachings (McKinley & Theall, 2021). Decolonizing content and process is emergent and ongoing. As such, content and processes that were outdated, that lacked an empirical basis, that could promote a real or perceived partiality toward dominant religious programs of “recovery”, and other culturally insensitive content and processes were removed. Figure 2 provides a snapshot of examples of cultural elements. The focus now turns to the approach and process of developing the program.

Figure 2.

Snapshot of WHF Cultural Components.

Source. Figure reprinted with permission from McKinley et al. (2023).

Note. The WHF program integrates a cultural approach to healing through elements, including the Indigenist FHORT, through the integration of talking circles in each session to foster egalitarian and tribally centered healthy communication, through the integration of the medicine wheel approach to wellness and mental health, through tribal values and teaching, such as through the Sacred Tree book that transmits examples of Indigenous value systems (Bopp, 1989), through the integration of culturally relevant risk and protective factors from a decade of preliminary work, and infusing Indigenist foodways. WHF = Weaving Healthy Families; FHORT = Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence.

The Approach: Integrate the Indigenist Approach and Perspective: FHORT

Following the toolkit strategy to use a tribal perspective, the Indigenist WHF program centers the FHORT (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Barrier to reducing mental health, behavioral health, and AOD abuse and family violence among Indigenous is that prevention programs have been approached conventionally from a non-Indigenous perspective, which has been often less effective and even harmful to Indigenous peoples (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014). In fact, applying an AOD abuse program with Indigenous youth that was not culturally specific led to an increase in Indigenous drug use after their participation in the program (Dixon et al., 2007). Unlike other works that have tended to impose a Western approach (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014), this project incorporated Two-Eyed Seeing by interweaving strengths of mainstream clinical knowledge Indigenous ways of knowing (Bartlett et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2019).

The WHF integrates the FHORT for improved wellness across behavioral, physical, psychological, and social dimensions while ameliorating risk factors for AOD use and violence. The program aims to improve wellness across ecological dimensions through the following mechanisms: (a) mental/emotional topics: emotional regulation/anger management, cognitions, and resilience; (b) social and familial topics: healthy and nonviolent relationships, the family environment, and parenting; and (c) cultural topics: the FHORT was integrated in addition to Indigenous values and traditions, talking circles, tribal teachings medicine wheel, and tribal nutrition and health. Prior research found support for this model, indicating the risk of perceived historical oppression, ACE, lower income, AOD abuse, and IPV being associated with higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD (McKinley, Miller Scarnato, et al., 2019). Family resilience, life satisfaction (a measure of transcendence), and social and community supports, in contrast, have been associated with reductions in these mental health symptoms (McKinley et al., 2021; McKinley & Lilly, 2022; McKinley, Miller Scarnato, et al., 2019).

The CBPR Process and Approach to Adapting and Implementing of the WHF Program

Adaptation: Incorporating Sustainable and Culturally Relevant Programming

Benefits of cultural adaptation of prevention programs include increased engagement and retention, leading to sustainable and long-lasting improvements in behavioral health (Kumpfer et al., 2002; Lau, 2006; Marsiglia & Booth, 2015) and minimizing unplanned practitioner adaptations, which compromise fidelity and effectiveness (Marsiglia & Booth, 2015).

CBPR integrates involvement of research partners throughout all aspects of the research process (Rasmus et al., 2019; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). Members share in the decision-making with a reciprocal exchange of expertise among researchers and participants (Rasmus et al., 2019; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). In line with the toolkit strategies of reciprocate and give back (i.e., disseminate results, developing useful programming, provide compensation), collaborate, invest resources, and develop an infrastructure, the WHF program CBPR approach included (a) integrating two CABs across cross-national contexts for the cultural adaptation process, (b) hiring tribal research personnel throughout all studies, (c) involving tribal partners in data collection and analysis, (d) disseminating findings to key tribal stakeholders on over 15 occasions, and (e) working with cultural insiders (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019).

Development of the WHF program was multipronged, with comparisons across two Indigenous groups, one of which had been using the unadapted Celebrating Families! program. This group revealed key barriers to the unadapted program, in that his curriculum was too dense, complicated, and fragmented. These barriers led practitioners to inadvertently impair the program’s fidelity by making unplanned adaptations to make the program more manageable. They tended to shorten the program by choosing sessions and activities at random and tended not to include the cultural components, which were not integrated with the core content (Griner & Smith, 2006; Kumpfer et al., 2002; Lau, 2006; Marsiglia & Booth, 2015). These barriers validated the need to modify the original evidence-based Celebrating Families! program.

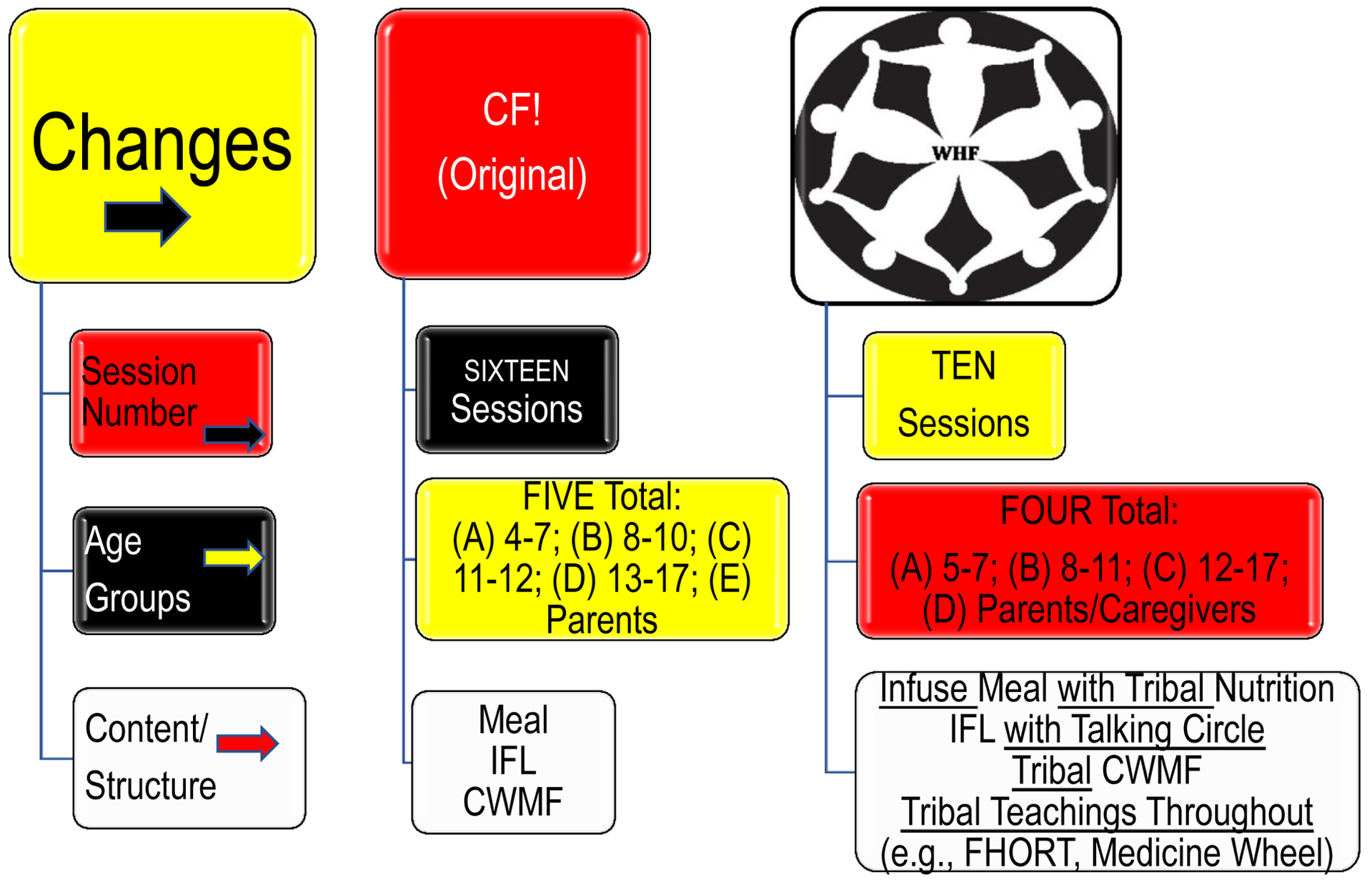

CAB members who helped adapt the program included trained behavioral health practitioners and leaders who worked in the fields of AOD abuse, parenting and family programs, the juvenile and criminal justice system, and families affected by IPV and child maltreatment. Before beginning the process of developing the WHF program and to clarify roles, all CAB members reviewed and signed with the opportunity to discuss or change the CAB member agreement. Following CBPR methods, the first author and CAB members cofacilitated the modification process. To create the WHF program, CAB members reviewed the original content for each session from the original Celebrating Families! program. CAB members made decisions about content to keep, adapt, or remove, and all changes were integrated into the revised treatment manual, which was presented for final comment to a partner site. The CAB made final decisions about the WHF program through consensus across all CAB members (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Figure 3 displays an overview of key changes made.

Figure 3.

Summary of Substantive Changes to the Weaving Healthy Families Program (WHF).

Note. The first column indicates the type of substantive changes made; the second column indicates the original program (Celebrating Families! [CF!]) components; and the final (third) column indicates the adapted WHF Program components. Insights for Living (IFL), which is the primary content, and Connecting with My Family (CWMF), which are family activities to foster connectivity. This program reduced 16 sessions to 10, reduced five age groups to four, and incorporated tribal and cultural healing throughout the structure. The 10 finalized sessions are as follows: (1) Introduction & Healthy Living; (2) Communication; (3) Feelings and Defenses; (4) Alcohol, Tobacco, and other Drug Use (ATOD); (5) ATOD and the family; (6) Goal Setting; (7) Choices and Problem Solving; (8) Boundaries and Healthy Relationships; (9) Resilience; and (10) Celebration. CF = Celebrating Families; IFL = Insights for Living; CWMF = Connecting with My Family; FHORT = Framework of Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence; WHF = Weaving Healthy Families.

First, based on CAB feedback, the number of sessions was reduced from 16 to 10 sessions to enhance feasibility. Second, the CAB, first author, and research team streamlined content. Pilot data revealed the excessive content was a critical barrier that undermined the process and depth of the WHF program. Session topics and associated core themes and activities were retained in the WHF program, and extraneous activities that overwhelmed participants and practitioners were removed. Fidelity was upheld by retaining the main themes explicated in the original content while enabling more time for participants to engage in an in-depth discussion and relational learning. The FHORT framed the WHF and foodway content in Session 1. Preliminary research and culturally based teachings were infused throughout all sessions.

Third, the opening and closing sections of the curriculum were integrated into a culturally relevant WHF program modality using the talking circle, which has been found to be an effective treatment modality for use on Indigenous AOD abuse (Becker et al., 2006). Two integrative spiritual components included smudging, or burning herbs for centering, purification, prayer, and for connection with Creator, God, or Higher Power (Portman & Garrett, 2006). The talking circle is a culturally congruent form of communication that centers everyone’s experience and cultural teachings, making use of holistic healing through the sacred use of the circle, smudging, and speaking from the heart while honoring other people to speak without interrupting (Becker et al., 2006; McKinley & Theall, 2021). Talking circles were infused into each WHF program session in the developmentally tailored content, creating space for the more relational and process-oriented learning that pilot participants and group leaders emphasized. Time for family dinners was extended, and Indigenist foodway content was infused throughout session dinners.

Fourth, each age group required ideally two facilitators as partners indicated having too many age groups made it difficult to sustain and manage groups and facilitators. As such, the preadolescent and adolescent groups were combined given their identical content and to streamline facilitation. Moreover, in contrast to the original ages of 4 to 7 for the youngest group, the group’s age range was changed to ages 5 to 7. This change paralleled the age children first attend grammar school and can comprehend the content. Children younger than the age of 5 were provided childcare (see Figure 3). Finally, after piloting the program twice, it was clear the younger aged children had difficulty maintaining focus in this didactic school-like learning style of the content. As such, the content for the younger children was changed to make them more developmentally engaging, active, and tribally focused. As the WHF program tended to be held in the early evening, after full school days and workdays, the family time was adapted to be lighter on content and more tribally focused, active, and experiential to increase engagement.

Implementation: Promoting Leadership Development and Infrastructures for Health

After adaptation, it was time to implement the WHF program, incorporating the toolkit strategies to invest resources and develop an infrastructure by contributing to the training, development, and nurturing of future community health leaders (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019). Hallmarks of CBPR, such as co-learning and future sustainability, were promoted through the engagement and training (Terpstra et al., 2011)—or CHRs, as they are termed among Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples have used CHRs since 1968 when the program was established by Indian Health Services (2022); however, no known CHR research has been focused on Indigenous peoples (Terpstra et al., 2011). CHRs are trusted community members who share the ethnic background and life experiences of participants (Spencer et al., 2010). CHRs facilitate research (Spencer et al., 2010) and ensure research methods are culturally appropriate and sustainable (Terpstra et al., 2011) as culturally incongruent programs tend to have poor participation (Kumpfer et al., 2002) and efficacy (Dixon et al., 2007). For the pilot, CAB members also served as CHRs who facilitated the WHF program. This CHR program has since expanded to now having trained over 40 CHRs to facilitate the WHF program.

CHRs facilitated the WHF program, with CHR coordinators providing oversight and management for the WHF program. They ensured sites were ready, materials were made, meals were delivered, and the program was conducted with fidelity. The CHRs were trained in the FHORT, facilitating the modified program using group facilitation skills and experiential activities. Training occurred over the course of two multiday training courses, along with follow-up refresher training courses. The training included role-plays and mock sessions for each component. New CHRs were paired with veteran CHRs for experiential training and mentorship before working more independently. CHRs received stipends for their time and professional development.

Despite strengths, there were several limitations of this preliminary pilot study—including its small scale and lack of control group. At the time of writing this article, the WHF program is being tested in a full-scale clinical trial (NCT03924167). Another limitation is the community resources and personnel to facilitate the program, and the family time availability to attend sessions, despite reducing the number of sessions from 16 to 10 (by 40%). The updated model enabled some attendance virtually during the COVID pandemic.

Discussion

The WHF program and its development process holds great promise to promote mental health and wellness while preventing and reducing violence and AOD abuse in Indigenous families, which are key mechanisms driving Indigenous mortality and morbidity. An important aspect of this long-term community engagement was the CAB was made up of practitioners and insiders who participated in the decade of preliminary research from multiple perspectives; their involvement increased due to their commitment and emergent leadership in the project. When developing culturally grounded prevention programs, it was important to consider not only the benefit of creating inclusive and culturally relevant WHF programs but also how engaging with community may have nurtured the development of cultural health leaders. These leaders reflected on the meaning and importance of their engagement through quotes displayed in Table 1, which provides their responses to the following questions:

What has being part of the CAB and facilitating the WHF program meant to you?

Why do you think the program is important for Indigenous families?

How has the program affected you?

Table 1.

Quotes from Community Advisory Board (CAB) Members.

| What has being part of the CAB and facilitating the WHF Program meant to you? | “Being a part of the CAB and facilitating Weaving Healthy Family Program has given me an opportunity to help [tribal] families become healthy through learning different and new ways of communicating with each other, as well as new and different coping skills.” |

| “Empowering. Being a part of CAB and WHF has meant I have a direct & positive impact between the intervention and outcomes for our community members.… With CAB and WHF, this is OUR program for OUR community and gives us a chance to see what can happen when we give 100% and are supported.” | |

| “Being a part of the CAB and facilitating WHF Program has meant a great deal to me because I am able to teach others’ skills that could improve the overall well-being of their families. This program is very important for NA families because it allows for them to reconnect and make sense of why issues exist among NA communities. I think the process is great, and easy for facilitators and families to gain essential information. The program made me think of all the things that I do with my own family and how I could make them better. Even as a facilitator, I learned new techniques that I could use at home. It was a great experience, and something that our tribe needed.” | |

| I’m very proud to have had a hand in getting this program started. I was able to learn more about my own culture and find ways to make the program relevant to my tribe. It has also helped me grow as a person and tackle issues I didn’t have the tools to tackle before. | |

| Why do you think the program is important for Native American families? | “It empowers those who are a part of it.” |

| Because it is based on our culture and our history. Nothing can heal us like our own people who have been through the problems we present. We have a shared history and have a better understanding of what is needed to help the family heal. | |

| “It takes into consideration the factors that make our families unique from other races/ethnicities. Factoring in our rural locations, our multigenerational family, being responsive to family’s needs with a cultural component was really important to let families in our community know we are trying give them another tool to address the issue of AOD abuse & abuse in families. …I think with populations so insulated from outside communities; reciprocal collaboration is essential to producing quality outcomes. [The Tribe] observes special holidays, our government operates outside of other forms of government and our households are even structured differently. To approach these populations without that understanding may result in … no long term sustainability.” | |

| “Some of the programs that we have used, we’re not curbing the violence or the drug epidemic that we have, or alcoholism—it’s not working. So, we’re going to have to get back with the basics, and maybe teach our people how to be strong within themselves.” | |

| What do you like about the process? | “In the past, we have used techniques that were mainly, majority non-NA techniques. And I don’t know, but I think people fail to realize that we are a different culture.… In the general population, you think about myself as number one, but in the traditional way of NA community, we supposed to be thinking about the whole community… you’re supposed to put ahead of you. These are things that some of us that were kinda raised in a traditional way, we still think like that.… Bureau of Indian Affairs have been taking care of us for the past 70 years, and we just getting worse and worse. And a lot of these traditional and medicine people have told me that we need to get back into our culture to heal, and I see other tribes doing it. So that’s one thing that I was happy about.…In a traditional way… If you’re going to make a decision, you listen to everybody, because no one person knows everything.…Some person that we think are very obnoxious or very outspoken, they might have something good to say. And some of those that are the silent ones, they may say few words but they may come up with some good ideas or… these are the things I think in collaboration, that’s what you gotta do, have all the people come together and try to figure out what is good for the whole. And I think that’s what this program is doing.” |

| “It is well thought out and works well. I think breaking up age groups the way we did was good because it gives each group a chance to participate as they wish, without feeling judged by another age group (young children not fearing repercussion from talking honestly about AOD abuse/physical abuse, teens being judged by parents, parents having to present a façade of strength etc.).” | |

| How has the program affected you? | I love that we took the time to base it on our tribal beliefs and how our families operate. It has changed the way I look at addiction and has helped me to find better ways to help those struggling. It has also helped me with my spiritual understanding and brought me peace. |

| “It was very open. It gives everybody a chance to speak out, say what they want. And if somebody says, you know, “pass,” you don’t look down on them and say, ‘Hey you gotta say something’… That’s basically what they do in our ceremonies,… like in the sweat lodge, if they want to get out, they can at any time. Instead of just trying to pressure them into going through the whole rounds of sweating.” | |

| “I am excited to see community members step into the space as points of contact … seeing older members share their story to younger parents.” |

Note. CAB = Community Advisory Board; WHF = Weaving Healthy Families; NA = Native American; AOD = alcohol and other drug.

Culturally based knowledge like guidance from the CAB must be integrated for relevance, efficacy, and adoption among Indigenous peoples (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Urban Indian Health Institute, 2014).

Implication and Applications for Practice

The process and development as well as cultural components provide a model of community-engaged and cultural congruent family-focused interventions. As such, this article provides promising pathways to develop efficacious and culturally relevant programs that promote mental health and prevent its primary risk factors. It outlines an incremental and sustainable process that can be replicated and applied in other contexts. Although the content and details of the WHF program are culturally specific, the Two-Eyed Seeing and CBPR approach, process, implementation, and integration of key cultural elements translate and can be applied across populations and target outcomes. The initial investment in developing culturally tailored programming may be significant, but the resultant efficacy of programs on key outcomes may be compelling. For example, the scope of this article is on the approach, development, and implementation of the WHF program rather than preliminary results from the pilot testing, which has been covered elsewhere (McKinley & Theall, 2021). However, a preview of promising results provided compelling implications about the rationale to warrant attention to the program’s development. Indeed, a pilot study for Indigenous families and the feasibility of the program being facilitated by tribal CHRs in 2019 to 2020 demonstrated strong acceptability and feasibility (McKinley & Theall, 2021).

The research team in this pilot initially aimed to recruit only a few families to evaluate feasibility and acceptability; however, due to an overwhelmingly high response rate and interest from families, eight families participated, including 33 individual participants (McKinley & Theall, 2021). All families completed the entire program and its components, which was successfully facilitated by tribal CHRs (McKinley & Theall, 2021). Because of this unanticipated participation, meaningful results from longitudinal pretest, posttest, and 6-month follow-up outcomes were identified among the eight Indigenous families who completed all program components (McKinley & Theall, 2021).

After completion of the WHF pilot program, results indicated a reduction in AOD use among parents and prevention of AOD use among all participating adolescents aged 12 to 17 (McKinley & Theall, 2021). Moreover, after completing the WHF program, participants reported significant improvements in key outcomes (McKinley et al., 2023; McKinley & Theall, 2021). Because some measures were not assessed with both subsamples due to age differences, the following outcomes were reported by the subsample(s) with which they were assessed: (a) adults: improvements in conflict resolution and health-related behaviors, along with reductions in depressive symptoms and psychological and physical violence; (b) adolescents: improvements in wellness; and (c) both adults and adolescents: improvements in emotional regulation, individual and family resilience, the quality of the family environment, communal mastery, social support, and reductions primary risk factors for diabetes and obesity (see McKinley & Theall, 2021, and McKinley et al., 2023, for full description of preliminary pilot outcomes). The WHF program is being evaluated in a clinical trial (McKinley & Theall, 2021).

Beyond the program’s efficacy, the long-term CBPR effort to develop capacity of community health leaders for sustainable mental health promotion is compelling. This work used CBPR to foster community stakeholders’ voices and direction in the development and facilitation of this WHF program. In total, over 70 CHRs have been trained to facilitate and oversee the WHF program, which fosters the development of community mental health leaders. Indeed, several CAB members continued, completed, and furthered their professional education during this program, filling the gap in highly trained tribal professionals to address community needs. As such, investment in the infrastructure of Indigenous communities enables greater sustainability, community buy-in, and, ultimately, effectiveness.

The preliminary success of the WHF program’s adaptation, implementation, and pilot results warrant other programs to make ample, long-term investment in CBPR work that engages community to make sustainable and lasting change to simultaneously promote mental health and wellness, community health leaders, and infrastructures for social change. Following CBPR protocols (Rasmus et al., 2019; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006) and the toolkit for research strategies (Burnette et al., 2014; McKinley, Figley, et al., 2019) can help guide future research to promote mental health and wellness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dedicated work and participation of the tribes and collaborators who contributed to this work. In particular, we thank Dana Kingfisher, Emily Matt Salois, d’Shane Barnett, Lily Gervais, Tanell Broncho, Kristen Pyke, Ann Douglas, Ivan MacDonald, Trilanda No Runner, and Lida Running and all the staff at the All Nations Health Center in Missoula, Montana, for their important contributions to the pilot program. We also thank Jennifer Martin, Juannina Mingo, Dan Isaac, Clarissa Stewart, Mariah Lewis, and Jeremy Chickaway for their incredible commitment, time, and energy devoted to the Weaving Healthy Families (WHF) Program. We thank Katherine P. Theall, Charles R. Figley, Karina Walters, James Allen, and Tonette Krousel-Wood for their support and mentorship for this pilot program. We thank The National Association for Children of Addiction for the original program that the WHF program was developed from and White Bison for introducing cultural components.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation Faculty Grant Program (grant number 552745); The Silberman Fund Faculty Grant Program (grant number 552781); the New-comb College Institute Faculty Grant at Tulane University; University Senate Committee on Research Grant Program at Tulane University; the Global South Research Grant through the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane University; The Center for Public Service at Tulane University; Office of Research Bridge Funding Program support at Tulane University; and the Carol Lavin Bernick Research Grant at Tulane University. This work was also supported, in part, by Award K12HD043451 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (Krousel-Wood-PI; Catherine McKinley [Formerly Burnette]-Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health [BIRCWH] Scholar); and by U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AA028201. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Around Him D, Burnette CE, Tafoya G, Yazzie-Mintz T, & Sarche M (2016). Tips for researchers: Strengthening research that benefits Native youth. National Congress of American Indians. https://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/research-data/prc-publications/TipsforResearchers-NativeYouth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett C, Marshall M, & Marshall A (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2, 331–340. 10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SA, Affonso DD, & Beard MBH (2006). Talking circles: Northern plains tribes American Indian women’s views of cancer as a health issue. Public Health Nursing, 23(1), 27–36. 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2006.230105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp J (1989). The sacred tree. Lotus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Chen J, & Black MC (2014). Intimate partner violence in the United States—2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21961 [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Boel-Studt S, Renner LM, Figley CR, Theall KP, Miller Scarnato J, & Billiot S (2020). The Family Resilience Inventory: A culturally grounded measure of intergenerational family protective factors. Family Process, 59(2), 695–708. 10.1111/famp.12423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, & Figley CR (2017). Historical oppression, resilience, and transcendence: Can a holistic framework help explain violence experienced by Indigenous peoples? Social Work, 62(1), 37–44. 10.1093/sw/sww065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, Sanders S, Butcher HK, & Rand JT (2014). A toolkit for ethical and culturally sensitive research: An application with Indigenous communities. Ethics and Social Welfare, 8(4), 364–382. 10.1080/17496535.2014.885987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette CE, & Sanders S (2017). Indigenous women and professionals’ proposed solutions to prevent intimate partner violence in tribal communities. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 26(4), 271–288. 10.1080/15313204.2016.1272029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson D, Brown RA, Johnson CL, Schweigman K, & D’Amico EJ (2015). Integrating motivational interviewing and traditional practices to address alcohol and drug use among urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 26–35. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AL, Yabiku ST, Okamoto SK, Tann SS, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, & Burke AM (2007). The efficacy of a multicultural prevention intervention among urban American Indian youth in the Southwest U.S. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 28(6), 547–568. 10.1007/s10935-007-0114-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 131–160. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, & Smith TB (2006). Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice & Training, 43(4), 531–548. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/2796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, & Marlatt GA (2004). Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 304–323. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. (2022). Community health representatives: About us. https://www.ihs.gov/chr/aboutus/

- Ka’apu K, & Burnette CE (2019). A culturally informed systematic review of mental health disparities among adult Indigenous men and women of the USA: What is known? British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 880–898. 10.1093/bjsw/bcz009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Sehdev M, & Isaac C (2009). Community resilience: Models, metaphors, and measures. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 5(1), 62–117. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ijih/article/view/28978 [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann K, Kelley ML, Mignone T, Pusateri L, & Fals-Stewart W (2010). Partner violence and substance abuse: Treatment intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(3), 162–166. 10.1016/j.avb.2009.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, D’Amico EJ, Dickerson DL, Skinner JR, Johnson CL, Kominsky TK, & Etz K (2022). Culturally responsive opioid and other drug prevention for American Indian/Alaska Native people: A comparison of reservation-and urban-based approaches. Prevention Science. Advance online publication 10.1007/s11121-022-01396-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, & Bellamy N (2002). Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention intervention. Prevention Science, 3(3), 241–246. 10.1023/A:1019902902119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 295–310. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, & Booth JM (2015). Cultural adaptation of intervention in real practice settings. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 423–432. 10.1177/1049731514535989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Boel-Studt S, Renner LM, & Figley CR (2021). Risk and protective factors for anxiety and depression among American Indians: Understanding the roles of resilience and trauma. Psychological Trauma, 13(1), 16–25. 10.1037/tra0000950 McKinley, C.E., Figley, C.R., Woodward, S., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell J, Billiot S, Comby N, & Sanders S (2019). Community-engaged and culturally relevant research to develop mental and behavioral health interventions with American Indian and Alaska Natives. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 26(3), 79–103. 10.5820/aian.2603.2019.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, & Lilly JM (2022). “It’s in the family circle”: Communication promoting Indigenous family resilience. Family Relations, 71, 108–129. 10.1111/fare.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Miller Scarnato J, Liddell J, Knipp H, & Billiot S (2019). Hurricanes and Indigenous families: Understanding connections with discrimination, social support, and violence on PTSD. Journal of Family Strengths, 19(1), Article 10. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol19/iss1/10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, Saltzman LY, & Theall KP (2023). Centering historical oppression in prevention research with Indigenous peoples: Differentiating substance use, mental health, family, and community outcomes. Journal of Social Science Research. Advance online publication. 10.1080/01488376.2023.2178596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley CE, & Theall KP (2021). Weaving Healthy Families Program: Promoting resilience while reducing violence and substance use. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(5), 476–492. 10.1177/1049731521998441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JR, & Bussey M (2007). Results of an alcohol prevention program with urban American Indian youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(1), 1–21. 10.1007/s10560-006-0049-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Children of Addiction. (n.d.). Celebrating families! Curriculum http://www.celebratingfamilies.net/curriculum.htm

- Novins DK, Boyd ML, Brotherton DT, Fickenscher A, Moore L, & Spicer P (2012). Walking on: Celebrating the journeys of Native American adolescents with substance use problems on the winding road to healing. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(2), 153–159. 10.1080/02791072.2012.684628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman TA, & Garrett MT (2006). Native American healing traditions. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53(4), 453–469. 10.1080/10349120601008647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmus SM, Charles B, John S, & Allen J (2019). With a spirit that understands: Reflections on a long-term community science initiative to end suicide in Alaska. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 34–45. 10.1002/ajcp.12356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruelle ML, & Kassam KAS (2013). Foodways transmission in the Standing Rock Nation. Food and Foodways, 21(4), 315–339. 10.1080/07409710.2013.850007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MS, Gunter KE, & Palmisano G (2010). Community health workers and their value to social work. Social Work, 55(2), 169–180. 10.1093/sw/55.2.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra J, Coleman KJ, Simon G, & Nebeker C (2011). The role of community health workers (CHWs) in health promotion research: Ethical challenges and practical solutions. Health Promotion Practice, 12(1), 86–93. 10.1177/1524839908330809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutty LM (2013). An evaluation of strengthening families: The Calgary Counselling Centre’s program for couples dealing with intimate partner violence and substance use. Yarro Creek Enterprises. 10.13140/RG.2.1.4010.1605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urban Indian Health Institute. (2014). Supporting sobriety among American Indians and Alaska Natives: A literature review. Seattle Indian Health Board. http://www.uihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Supporting-Sobriety_A-Literature-Review_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, & Duran B (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. 10.1177/1524839906289376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, & Simoni JM (2002). Reconceptualizing native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health, 92(4), 520–524. 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB (2006). Some guiding assumptions and a theoretical model for developing culturally specific preventions with Native American people. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(2), 183–192. 10.1002/jcop.20094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White Bison. (2021). Wellbriety and Celebrating Families!™. Retrieved from http://whitebison.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/WCF.pdf

- Wright AL, Gabel C, Ballantyne M, Jack SM, & Wahoush O (2019). Using two-eyed seeing in research with indigenous people: an integrative review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. 10.1177/1609406919869695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.