Abstract

Eukaryotic transcriptional activators generally comprise both a DNA-binding domain that recognizes specific cis-regulatory elements in the target genes and an activation domain which is essential for transcriptional stimulation. Activation domains typically behave as structurally and functionally autonomous modules that retain their intrinsic activities when directed to a promoter by a variety of heterologous DNA-binding domains. Here we report that OBF-1, a B-cell-specific coactivator for transcription factor Oct-1, challenges this traditional view in that it contains an atypical activation domain that exhibits two unexpected functional properties when tested in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. First, OBF-1 by itself has essentially no intrinsic activation potential, yet it strongly synergizes with other activation domains such as VP16 and Gal4. Second, OBF-1 exerts its effect in association with DNA-bound Oct-1 but is inactive when attached to a heterologous DNA-binding domain. These findings suggest that activation by OBF-1 is not obtained by simple recruitment of the coactivator to the promoter but requires interaction with DNA-bound Oct-1 to stimulate a step distinct from those regulated by classical activation domains.

In eukaryotes, appropriate gene expression during development and in response to extracellular signals is controlled primarily at the level of transcription. Regulated transcription of protein-encoding genes by RNA polymerase II (pol II) is a highly conserved process that involves the interplay between general transcription factors, which are essential for RNA pol II to initiate mRNA synthesis accurately from the core promoters of all genes, and transcriptional regulatory proteins—mostly activators—which selectively modulate the rate of transcription initiated at the core promoters of specific genes (8, 30, 34, 37). Transcriptional activators comprise both a DNA-binding domain that recognizes specific cis-regulatory elements in the enhancer and promoter regions of target genes and an activating region that stimulates transcription initiated at the adjacent core promoter (32). The DNA-binding and activation domains typically behave as functionally and physically independent modules (i.e., activation domains retain their functional activity when fused to a wide variety of heterologous DNA-binding domains). The two functions may either be contained within a single polypeptide or reside on different proteins that interact with each other. In the latter case, the protein that bears the activating region is often referred to as a coregulator or coactivator (8). Activation domains are believed to function primarily by facilitating formation of functional preinitiation complexes through interactions with one or more components of the basal transcription machinery. These interactions are thought to recruit, stabilize, and/or induce conformational changes in the preinitiation complex (7, 33, 35, 46). The binding of two or more activators at the promoter generally leads to a greater than additive increase in the amount of transcription, a phenomenon referred to as synergy (4, 17). The ability of activators to work synergistically may result from their cooperative binding to the DNA and/or reflect an intrinsic ability of their respective activation domains to stimulate different steps in the transcription process, perhaps through interactions with different components of the basal machinery (2, 33).

The promoter specificity of transcriptional activators is conferred mainly by the specificity of their DNA-binding domains. There are cases, however, where a single activator controls the activities of genes that exhibit very different expression profiles. A prominent example is the homeodomain protein Oct-1, a broadly expressed member of the POU family of transcription factors (16, 38, 41). Oct-1 mediates activity of the conserved octamer sequence known to be a key determinant for the B-cell-restricted expression of immunoglobulin (Ig) genes (19), the cell cycle regulation of the histone H2B gene (9), and the ubiquitous transcription of the small nuclear RNA (snRNA) genes by either RNA pol II or RNA pol III (24). The ability of Oct-1 to differentially activate gene transcription is explained, at least in some cases, by its ability to interact with cell-type-specific and ubiquitous proteins that function as promoter selectivity factors. Thus, B-cell-restricted, octamer site-dependent transcription requires association of Oct-1 with the B-cell-specific coactivator OBF-1 (45) (also referred to as OCA-B [26] and Bob1 [13]), while activation of snRNA gene promoters involves contacts between Oct-1 and SNAP190, a subunit of general transcription factor SNAPc (47). Both proteins interact with Oct-1 through its POU domain, a bipartite DNA-binding motif containing a POU-specific domain connected through a flexible linker to a POU homeodomain (15, 39). Remarkably, despite the fact that OBF-1 and SNAP190 differ in primary structure and function, they share a small region with striking sequence similarities that mediates interaction with Oct-1 (10).

The mechanisms whereby OBF-1 increases octamer-dependent promoter activity in conjunction with Oct-1 remain uncertain. It has been suggested that OBF-1 may function in part by stabilizing binding of Oct-1 to its cognate site (1). However, most of the OBF-1 coactivation function is probably explained by the coactivator providing a transcriptional activation domain. Exactly which region of OBF-1 is responsible for mediating transcriptional activity remains elusive, as the predominant activation function has been mapped either to the central part of the protein (12) or to its carboxy-terminal region (25, 31). It is also unclear whether OBF-1 activity requires cooperation with activation domains within the Oct-1 protein. In vitro studies using Oct-1-depleted HeLa nuclear extracts have shown that although sufficient for tethering OBF-1 to the promoter, the Oct-1 POU domain alone fails to mediate OBF-1 transactivation (26). On the other hand, the use of an altered DNA-binding specificity mutant of Oct-1 revealed that the same POU domain permits activity of Ig gene promoters in B cells (43).

A major problem in gaining further insight into the mechanisms whereby OBF-1 may contribute to Oct-1-dependent transcription is the lack of a mammalian in vivo system devoid of endogenous Oct-1 activity. We therefore investigated OBF-1 activation potential in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which Oct-1 is absent. We found that OBF-1 provides an unusual transcriptional activation domain that exhibits no independent activity on its own yet synergizes efficiently with other classical activation domains. Moreover, OBF-1 activity is strictly dependent on the coactivator being tethered to the promoter by Oct-1, indicating that activation requires a DNA-bound Oct-1-dependent context and is not obtained by simple recruitment of OBF-1 to the DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast expression vectors.

All OBF-1 variants were cloned in the multicopy vector pYES2 (Invitrogen) under the control of the GAL1 promoter. All other proteins were expressed from single-copy plasmids marked with the URA3, TRP1 (44), or ADE2 (11) gene under control of the TBP promoter, except for the VP16–Oct-1–RFX and Max-RFX-VP16 fusion proteins, which were expressed from the DED1 and GAL1 promoters, respectively (11). Max-RFX and VP16-RFX (22) as well as Oct-1 (45) have been described elsewhere. VP16–Oct-1 was obtained by fusing the VP16 activation domain (residues 410 to 490) in frame to the amino terminus of Oct-1. VP16 was also fused to the carboxy terminus of Max-RFX to generate Max-RFX-VP16. The region (residues 693 to 881) encoding the carboxy-terminal activation domain of Gal4 (27) was amplified by PCR from yeast genomic DNA, using primers that introduced an ATG initiator codon at position 692 and convenient restriction endonuclease sites to allow direct subcloning of the amplified fragment. The Gal4 activation domain was fused in frame to the amino terminus of either Oct-1 or RFX to generate Gal4–Oct-1 or Gal4-RFX, respectively. VP16–Oct-1–RFX was obtained by fusing VP16–Oct-1 in frame to the amino terminus of RFX. The Myc dimerization motif (22) was joined amino terminally to OBF-1 (45) to produce Myc–OBF-1. The amino-terminal deletion mutants of OBF-1 were obtained by PCR amplification using primers that allowed their direct fusion to the Myc dimerization motif to produce Myc–OBF-1(102-256) and Myc–OBF-1(145-256). Myc–OBF-1(121-256) was constructed by using a naturally occurring PvuII site. Myc-VP16 is a gift from Bruno Amati. Details of plasmid constructions are available upon request.

Reporter constructs.

The lacZ and his3 reporter genes driven by promoters bearing either six octamer motifs (45) or a single RFX-binding site (22) upstream of the his3 core promoter derived from his3-Δ94 (14) have been described elsewhere. The lacZ allele containing an RFX-binding site upstream of six octamer elements was constructed by insertion of the respective double-stranded oligonucleotide at the unique EcoRI restriction site between the naturally occurring dA-dT element of the HIS3 gene and the six reiterated octamer motifs. The lacZ allele containing a single octamer element was obtained by insertion of a double-stranded oligonucleotide encompassing the same Ig(κ) octamer motif and flanking sequences as those used in the gel retardation assays (see below) at the unique EcoRI site located 80 bp upstream of the consensus his3 TATA element found in the lacZ allele described previously (11). The oligonucleotides were designed such that the octamer motif lies between an upstream BamHI site and a unique EcoRI site downstream. This construct was used to generate the lacZ allele containing the octamer motif surrounded by dA-dT tracts by inserting a homopolymeric dA-dT sequence containing 20 T residues on the his3 coding strand into the unique EcoRI site downstream of the octamer motif. The upstream dA-dT sequence is the naturally occurring dA-dT element of the HIS3 gene. Details of plasmid constructions are available upon request.

Yeast strains and phenotypic analyses.

The yeast strains are derivatives of KY320 (6) into which the HIS3 locus was replaced by the relevant lacZ and his3 alleles by using standard procedures. Transformed cells were grown in selective medium and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described elsewhere (11).

Yeast extracts and immunoassays.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described elsewhere (11). Proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Immunoblotting was performed with an Amersham ECL kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a 1:2,000 dilution of an affinity-purified rabbit anti-human Oct-1 antibody (a gift from P. Matthias). The blot was then stripped in 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol–2% sodium dodecyl sulfate–62.5 mM Tris (pH 6.7) at 55°C for 30 min and reprobed with a 1:250 dilution of purified rabbit anti-yeast TFIIB antiserum (a gift from R. A. Young).

Nuclear extract preparation, in vitro translation, and electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells were prepared as described previously (28) and used as a source of Oct-1. OBF-1 was produced in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega) programmed with cRNA transcribed from the OBF-1 clone 9 cDNA (45) by using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed either at room temperature (off rate) or at 4°C (on rate) with 10 fmol of a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the wild-type Ig(κ) octamer site (in boldface; ATTCTGATCATTATGCAAATAGGATCCGAT) as described by Strubin et al. (45). The binding reaction mixtures contained 25 μg of nuclear extracts, 2.5 μl of programmed or unprogrammed reticulocyte lysate, 5 μg of poly(dI-dC), and 1 μg of single-stranded salmon sperm DNA in a final volume of 50 μl. Competitor oligonucleotides containing either the wild-type Ig(κ) octamer sequence or the mutated (at the site underlined) version (ATTCTGATCATTATGCTAATAGGATCCGAT) were added in a 100-fold excess. An aliquot of the reactions (10 μl) was loaded at the time points indicated in the legend to Fig. 2 onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA that had been prerun at 200 V for 4 h, and electrophoresis was continued at 200 V. The gel was dried and autoradiographed. The intensities of the signals were quantified by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis.

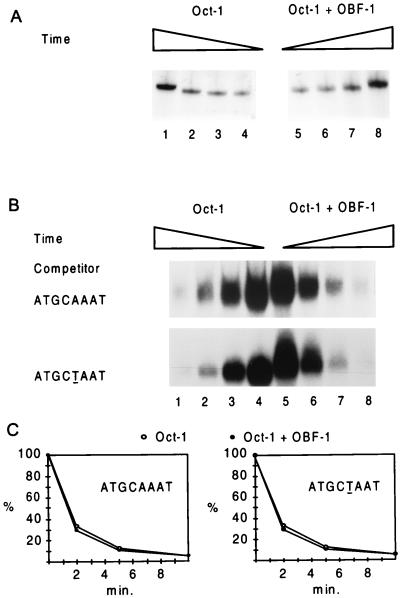

FIG. 2.

OBF-1 does not stabilize Oct-1 on the octamer motif in vitro, and it forms an unstable complex with Oct-1 in solution. The effect of OBF-1 on the kinetics of Oct-1 binding to (A) or dissociating from (B) its cognate site in the absence and presence of OBF-1 was determined by gel retardation analyses. Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells expressing endogenous Oct-1 were incubated with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide encompassing the same wild-type Ig(κ) octamer site (ATGCAAAT) and flanking sequences as inserted upstream of the lacZ reporter gene depicted in Fig. 3. Where indicated, OBF-1 expressed in rabbit reticulocyte lysates was added in excess such that only the ternary complex containing both OBF-1 and Oct-1 is formed. The association rates were measured by incubating the binding reaction mixtures at 4°C for 1, 2, 5, and 20 min before loading them onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel (A, lanes 4 to 1 and 5 to 8, respectively). The dissociation rates were measured by incubating the binding reaction mixtures for 30 min at ambient temperature before the addition of a 100-fold excess of competitor DNA. The oligonucleotides used as competitor contained either the wild-type Ig(κ) octamer site (ATGCAAAT) or a mutated site (ATGCTAAT) that allows normal binding of Oct-1 but not ternary complex formation (5, 12). Aliquots of the reactions were either directly loaded onto a running gel (B, lanes 4 and 5) or further incubated for 2, 5, and 10 min (lanes 3 to 1 and 6 to 8, respectively). (C) Dissociation rates obtained with either the wild-type Ig(κ) (ATGCAAAT) or the mutated (ATGCTAAT) octamer site as a competitor. The signals were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments carried out with different batches of proteins.

Mapping of the OBF-1 domain that interacts with Oct-1, using a yeast one-hybrid assay. (i) Construction of the OBF-1 carboxy-terminal deletion library.

The library was generated with a Pharmacia double-stranded nested deletion kit. The starting plasmid contained a 3-kb fragment of stuffer DNA inserted at the 3′ end of the OBF-1 coding region between unique BamHI and NotI sites introduced into the yeast expression vector described previously (45). The plasmid was linearized with BamHI and digested with exonuclease III as instructed by the manufacturer. Aliquots were removed from the reaction every 2 to 4 min for 36 min. The reactions were stopped by addition of S1 nuclease buffer, and the single-stranded DNA was removed by digestion with S1 nuclease. The aliquots were pooled, the stuffer DNA was excised by digestion with NotI, and the remaining linear plasmid DNAs were recircularized with T4 DNA ligase after treatment with Klenow enzyme to obtain blunt ends. The ligation mixture was introduced into Escherichia coli DH5α by electroporation, and the library was amplified by plating the cells onto 10 10-cm-diameter plates.

(ii) Selection in yeast and analysis.

The deletion library was introduced into a yeast strain carrying as a selectable marker gene an integrated copy of a his3 allele bearing six octamer sites upstream of the TATA element and expressing Oct-1 constitutively from a centromeric plasmid marked with the URA3 gene (45). The library (10 μg) was introduced into the reporter strain as described elsewhere (45). An estimated 2 × 105 double transformants were grown for 24 h at 30°C in 250 ml of glucose medium lacking uracil and tryptophan to maintain selection for both plasmids, at which time the culture consisted of approximately 80% Trp+ Ura+ cells. After centrifugation, 108 cells were resuspended in 50 ml of galactose selective medium and incubated for 6 h at 30°C to induce expression of the truncated protein library. Transformants (starting with an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05) were then grown in 50 ml of galactose synthetic medium lacking histidine and containing 10 mM aminotriazole (AT) to an optical density of 1.0. The OBF-1-containing plasmids were recovered from large pools of transformants (2 × 108 cells) either before or after selection in AT. Plasmid rescue was performed as described previously (36) except that the DNA was further purified on a Sepharose CL-4B column to remove impurities which inhibit E. coli transformation. The library was amplified in E. coli after transformation by electroporation (2 × 105 colonies). The inserts encoding OBF-1 were end labeled at the unique EcoRI restriction site flanking the ATG initiator codon by using Klenow enzyme before being excised from the vector by cleavage at the KpnI site downstream of the OBF-1 coding region and separated on a 6% denaturing sequencing gel.

RESULTS

OBF-1 shows transcriptional activity in yeast only in synergy with other transactivation domains.

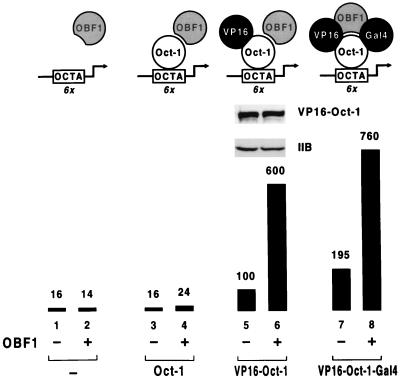

The transactivation properties of the OBF-1 coactivator were assessed in a yeast strain carrying as a reporter gene an integrated copy of a lacZ allele containing six octamer motifs in front of the minimal his3 promoter. The cells also contain a centromeric plasmid which directs expression of either native Oct-1, which cannot activate transcription in yeast, or Oct-1 derivatives made transcriptionally competent by fusion to heterologous transactivation domains. Figure 1 shows that expression of OBF-1 in this strain, either alone (lanes 1 and 2) or together with Oct-1 (lanes 3 and 4), is not sufficient to stimulate octamer-dependent lacZ gene transcription. In marked contrast, however, OBF-1 strongly boosts the activity of Oct-1 variants bearing the activation domain of either the herpes simplex virus protein VP16 (lanes 5 and 6) or the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (see below). Remarkably, the potentiating effect of OBF-1 on the VP16 activation domain is significantly greater than the enhancement observed (in the absence of OBF-1) when a second classical transactivation domain such as Gal4 is fused to VP16–Oct-1. Moreover, the activity of the Oct-1 derivative bearing the two activation domains is also boosted by OBF-1 (lanes 7 and 8). Thus, OBF-1 exhibits no transcriptional activity when recruited to octamer sites by the inactive Oct-1 factor, but it efficiently increases the transactivation potential of Oct-1 derivatives bearing functional activation domains.

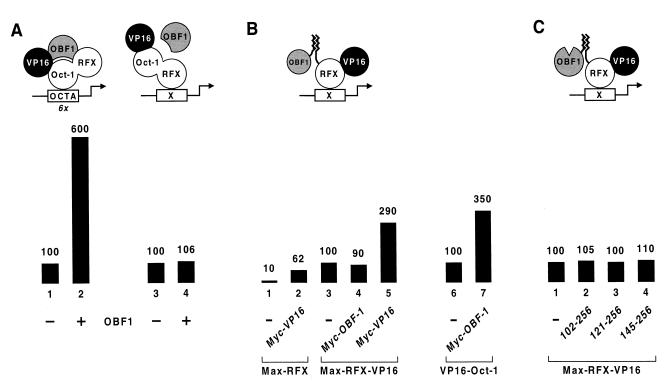

FIG. 1.

OBF-1 exhibits transcriptional activity only in conjunction with other transactivation domains. The activity of a lacZ reporter gene integrated at the HIS3 locus and bearing six octamer motifs (OCTA) upstream of the his3 TATA element was assessed in yeast strains expressing (+) or not expressing (−) OBF-1 and the indicated proteins from plasmid DNAs. The Oct-1 variants (and the RFX derivatives depicted in Fig. 3 and 5) were placed under control of the TBP promoter on a single-copy plasmid, and OBF-1 was expressed from the multicopy vector pYES2 (Invitrogen) under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Transformed cells were grown in selective medium containing galactose and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. In this and the other figures, values are relative to the level of β-galactosidase activity seen with either VP16–Oct-1 or VP16-RFX alone, which was assigned a value of 100. A protein immunoblot of whole-cell extracts from strains expressing VP16–Oct-1 either alone (lane 5) or together with OBF-1 (lane 6), using antibodies directed against human Oct-1 or yeast TFIIB, is shown at the top.

A trivial explanation for the ability of OBF-1 to potentiate the activity of transcriptionally competent Oct-1 proteins is that the coactivator functions by increasing Oct-1 promoter occupancy, by stabilizing VP16–Oct-1 protein and/or by enhancing the binding of the Oct-1 fusion proteins to the octamer motif. Evidence against the former possibility is provided by Western blotting using an antibody directed against Oct-1 and cell extracts derived from yeast strains expressing VP16–Oct-1 either alone or together with OBF-1; this shows that OBF-1 has no effect on the stability of the fusion protein in yeast cells (Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6). That OBF-1 does not enhance the affinity of Oct-1 for its cognate sequence is suggested by earlier observations indicating that in vitro, the dissociation rate of the Oct-1 POU domain from its binding site is not altered by the presence of OBF-1 in the complex (45). To confirm and extend these findings, we carried out in vitro DNA binding studies using a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the same wild-type Ig(κ) octamer site (ATGCAAAT) and flanking sequences as inserted upstream of the lacZ reporter gene. The experiments were carried out in the presence of an excess of OBF-1 such that only the ternary complex containing both OBF-1 and Oct-1 is formed. Figure 2A shows that OBF-1 has no effect on the kinetics of Oct-1 binding to the octamer site. The dissociation rate of Oct-1 from its cognate sequence also is not influenced by the presence of OBF-1 in the complex (Fig. 2B and C). Strikingly, the same result is observed when the competitor DNA used for the experiment contains a mutated site (underlined; ATGCTAAT) that allows normal binding of Oct-1 but not formation of the ternary complex (5, 12) (Fig. 2B and C). Since Oct-1 must dissociate from OBF-1 before binding to the mutated sequence, these results imply that the two proteins form an unstable complex in solution.

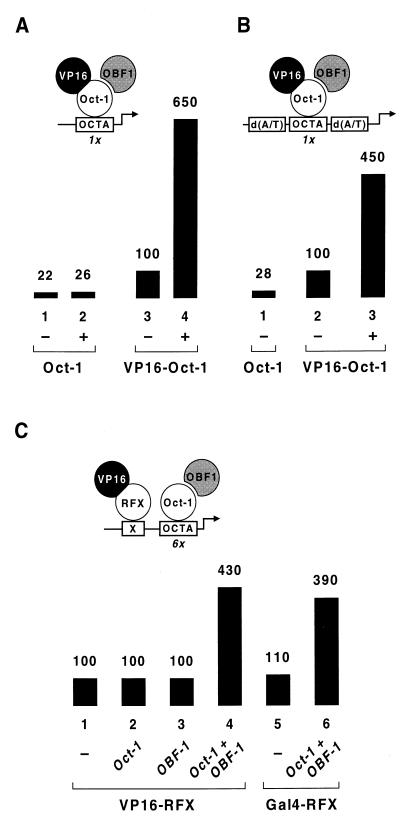

The one reported situation in which OBF-1 was found to enhance Oct-1 binding to the DNA in vitro was on a template containing two octamer sites, a high-affinity site derived from the H2B gene and an adjacent, low-affinity site from the Ig(κ) promoter (1). Since OBF-1 is likely to interact with both the POU-specific domain and the POU homeodomain (1, 40), it is conceivable that OBF-1 acts in this case as a bridging molecule by contacting two Oct-1 proteins simultaneously, thereby facilitating their binding on adjacent octamer elements. To determine if OBF-1 increases VP16–Oct-1-dependent expression of the lacZ gene bearing six contiguous octamer sites by such a mechanism, we measured the effect of OBF-1 on the activity of VP16–Oct-1 at a promoter bearing only a single octamer motif. We found that OBF-1 boosts the activity of VP16–Oct-1 with comparable efficiencies when one octamer site rather than multiple octamer sites is present upstream of the his3 core promoter (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4).

FIG. 3.

OBF-1 mediates transcriptional synergy without enhancing transcription factor binding to the promoter. The activities of the octamer-containing lacZ reporter genes diagrammed above each panel were assessed in yeast strains expressing the indicated proteins from plasmid DNAs. (A) The promoter bears a single octamer element (OCTA) upstream of the his3 TATA box in place of the six reiterated octamer motifs depicted in Fig. 1. Note that the values are relative to the level of β-galactosidase activity seen with VP16–Oct-1, but the absolute levels of transcription from that promoter are decreased by a factor of 5 to 10 compared to the levels of transcription from the promoter bearing six octamer motifs. (B) The promoter contains a single octamer site surrounded by poly(dA-dT) sequences that impair nucleosome assembly or stability. (C) The promoter contains a single RFX-binding site (X) inserted upstream of six octamer motifs.

In a living cell, the access of transcription factors to their promoter sites is severely restricted because the DNA template is in the form of chromatin. OBF-1 might thus function in vivo by causing local changes in the chromatin structure and thereby indirectly facilitating the accessibility of VP16–Oct-1 to the octamer site. To address this point, we tested the effect of flanking the octamer element with homopolymeric dA-dT tracts. Poly(dA-dT) sequences have intrinsic structural characteristics that impair nucleosome assembly or stability, thereby allowing transcription factors to gain access to a nearby target element (18). If OBF-1 acts only by modifying the nucleosomal structure on the promoter, one would expect VP16–Oct-1 to be less dependent on OBF-1 when the octamer site is surrounded by poly(dA-dT) tracts. Figure 3B shows, however, that OBF-1 exerts a similar effect on activation by VP16–Oct-1 from such a poly(dA-dT)-containing promoter (lanes 2 and 3). This finding suggests that the coactivator does not act by locally destabilizing the nucleosomal structure on the promoter.

Finally, if OBF-1 were to enhance Oct-1 binding to the DNA in vivo, the OBF-1-mediated synergistic effect would be restricted to the heterologous activation domain being recruited to the promoter by Oct-1. However, Fig. 3C shows that both the VP16 and Gal4 activation domains retain their responsiveness to OBF-1 when they are recruited to the promoter by RFX, another human DNA-binding protein with no transactivation potential in yeast (22) (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 and 6). As expected, synergy in this case remains dependent on the presence of both Oct-1 and OBF-1 (compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 4). The reduced magnitude of the OBF-1 effect is likely to be due to the fact that the promoter is not always occupied simultaneously by VP16-RFX and the Oct-1–OBF-1 complex. We conclude from these experiments that OBF-1 has no independent transcriptional activity in yeast, but that it enhances the activity of transcriptionally competent Oct-1 variants, or activators bound nearby, without facilitating their binding to the promoter.

Transcriptional synergy requires a region within OBF-1 distinct from the Oct-1 interaction domain.

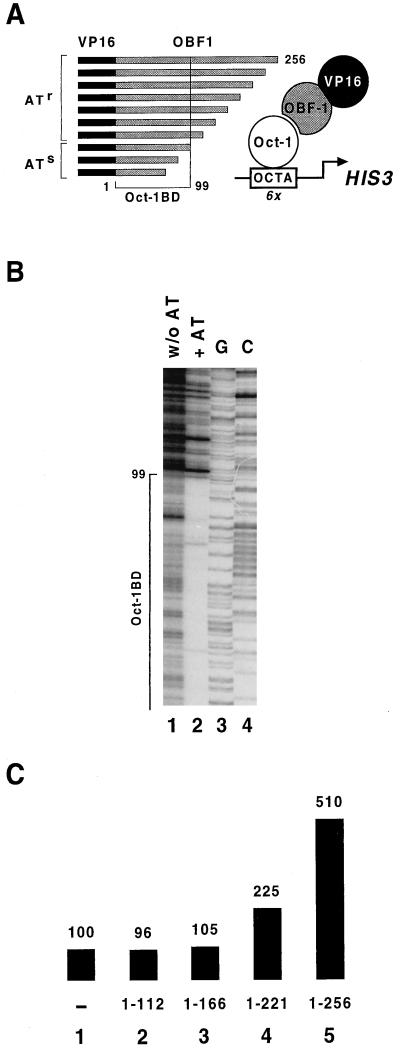

To determine whether the domain(s) critical for the coactivation function of OBF-1 overlapped or was distinct from the domain that mediates interaction with Oct-1, we first mapped at single-amino-acid resolution the boundaries of the OBF-1 region required for association with this factor in vivo. Because this region is known to lie within the amino-terminal part of the protein (12, 45), we constructed a collection of carboxy-terminally truncated OBF-1 mutants (see Materials and Methods for details). A library containing essentially all possible deletions fused to the VP16 activation domain was introduced together with a centromeric plasmid expressing Oct-1 into a yeast strain carrying an integrated copy of an octamer-dependent his3 allele (Fig. 4A). Cells expressing truncated VP16–OBF-1 fusion proteins that still interact with Oct-1, and hence transcribe the HIS3 gene at induced levels, were selected in medium containing AT, a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product. The VP16–OBF-1-containing plasmids were recovered from large pools of transformants before and after selection in AT, and the inserts encoding OBF-1 were excised from the vector and separated on a denaturing sequencing gel. Figure 4B shows that nearly every possible truncation is represented in the library before selection (lane 1). After selection for induced HIS3 expression, those OBF-1 variants that retain the first 99 amino acids are efficiently recovered and only a very few distinct bands of weaker intensity corresponding to shorter versions of OBF-1 are also observed (lane 2). Such a profile after selection in AT indicates that truncations beyond amino acid 99 produce OBF-1 derivatives that are strongly compromised in the ability to associate with Oct-1 and therefore defines the carboxy-terminal boundary of the OBF-1 domain required for efficient interaction with this factor in vivo as residue 99.

FIG. 4.

Mapping of the OBF-1 domains critical for interaction with Oct-1 and coactivation function. (A) Strategy used for the high-resolution mapping of the smallest carboxy-terminal OBF-1 truncation capable of interacting with Oct-1 in a one-hybrid screen in yeast. The collection of OBF-1 truncations fused to VP16 was generated by digesting plasmid DNA linearized at the 3′ end of the OBF-1 coding region with exonuclease III for increasing lengths of time. The library was introduced together with a centromeric plasmid expressing Oct-1 into a tester strain carrying an integrated copy of an octamer-dependent his3 allele. Transformants were first grown in medium selecting for both plasmids. Cells expressing OBF-1 derivatives that retain the ability to associate with promoter-bound Oct-1 were subsequently selected in synthetic medium containing 10 mM AT, a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product. Oct-1BD, Oct-1-binding domain. The native protein is 256 amino acids long, and the Oct-1-binding domain ends at residue 99. (B) Size analysis of the inserts encoding OBF-1 excised from plasmids recovered from large pools of transformants before (w/o AT) and after (+AT) selection for induced HIS3 expression and separated on a 6% acrylamide–urea denaturing gel after end labeling. Lanes G and C show the sequencing reactions of an unrelated DNA fragment of known sequence that were used as markers to determine the boundary of the OBF-1 domain required for interaction with Oct-1 factor in vivo at single-codon resolution. (C) The indicated OBF-1 carboxy-terminal truncations devoid of a VP16 activation domain were examined for the ability to synergize with VP16–Oct-1 on the octamer-dependent lacZ reporter as depicted in Fig. 1.

The strategy described above cannot be used to map the domain(s) required for the OBF-1 synergistic effect, because VP16–Oct-1 already activates HIS3 transcription on its own. We thus examined the transactivation capabilities of a few selected carboxy-terminal OBF-1 truncations. Figure 4C shows that deletion of only 35 residues at the carboxy terminus of OBF-1 strongly reduces its ability to synergize with VP16–Oct-1 on the lacZ promoter (lane 4). Further removal of the next 55 residues produces a 166-amino-acid-long OBF-1 derivative that, although retaining the entire Oct-1 interaction domain, has no coactivation function (lane 3). Hence, the Oct-1 interaction domain of OBF-1 alone is unable to boost VP16–Oct-1 factor-dependent transcription. This conclusion is consistent with the interpretation that the coactivator functions by a mechanism other than the stabilization of Oct-1 on the octamer element. Taken together, these results indicate that the carboxy-terminal region of OBF-1 provides an unusual activation function that exhibits no transcriptional activity on its own yet acts synergistically with other activation domains when recruited to the promoter through interaction with Oct-1.

OBF-1 exhibits DNA-bound Oct-1-dependent transcriptional activity.

Activation domains typically behave as structurally and functionally autonomous modules that retain their intrinsic activities when directed to a promoter through covalent or noncovalent interactions with a wide variety of heterologous DNA-binding domains. This prompted us to assess whether OBF-1 would synergize with VP16 or Gal4 activation domains when it is tethered to promoter DNA by a protein other than Oct-1. We therefore fused VP16–Oct-1 to RFX and tested the resulting chimera for its responsiveness to OBF-1 on promoters that contain either Oct-1- or RFX-binding sites. Figure 5A shows that while OBF-1 exerts a synergistic effect through the octamer site (lanes 1 and 2), it fails to do so through the RFX site (lanes 3 and 4). These findings raise the interesting possibility that the coactivator exhibits transcriptional activity only when associated with Oct-1 bound to DNA. However, the gel retardation experiments presented in Fig. 2 indicate that the OBF-1–Oct-1 complex is highly unstable in solution. Furthermore, no interaction between the two proteins could be detected in a conventional two-hybrid assay (data not shown). We thus favor the interpretation that OBF-1 and Oct-1 interact very inefficiently, if at all, in the absence of DNA.

FIG. 5.

OBF-1 exhibits DNA-bound Oct-1-dependent transcriptional activity. (A) The ability of native OBF-1 to potentiate the activity of a VP16–Oct-1-RFX chimera was examined on lacZ promoters bearing either six octamer elements (OCTA) or a single RFX-binding site (X) upstream of the his3 TATA box. OBF-1 may or may not interact with Oct-1 on the RFX-dependent promoter. (B) OBF-1 was noncovalently recruited to the RFX-dependent promoter by fusing to the amino termini of OBF-1 and RFX (or RFX-VP16) the complementary dimerization domains of the human c-Myc oncoprotein and its partner Max, respectively (22). Max-RFX-VP16 is expressed from the GAL1 promoter instead of the TBP promoter. As a control, Myc–OBF-1 was also tested for synergy with VP16–Oct-1 on the octamer-dependent promoter. (C) The indicated amino-terminally truncated forms of OBF-1 were examined for their transactivation potential when recruited to the RFX-dependent promoter by Max-RFX-VP16 through their Myc dimerization domains.

To assess the ability of OBF-1 to synergize with the VP16 activation domain in the context of RFX, the coactivator was noncovalently recruited to the RFX-dependent promoter by fusing to the amino termini of OBF-1 and RFX the complementary dimerization domains of the human c-Myc oncoprotein and its partner Max, respectively (22). Unexpectedly, Fig. 5B shows that the resulting Myc–OBF-1 variant is transcriptionally inactive when tethered to the promoter by a Max-RFX protein carrying a VP16 activating region at the carboxy terminus (compare lanes 3 and 4). This contrasts with the threefold synergy observed when a second VP16 activation domain (Myc-VP16) is brought to the promoter in the same way by Max-RFX-VP16 (lane 5). Yet Myc–OBF-1 is fully functional, as it retains its ability to synergize with VP16–Oct-1 on the octamer-dependent promoter (lanes 6 and 7). Synergistic activation is thus not obtained by simple recruitment of the coactivator to the DNA. The somewhat lower activity of Myc–OBF-1 than of the native protein is likely to be due to the fact that the OBF-1 fusion protein is present in lower amounts, because the Myc dimerization domain has been observed to destabilize the proteins to which it is connected (11b).

The inability of OBF-1 to function in the context of a heterologous DNA-binding protein may reflect an intramolecular interaction between the activation and Oct-1-binding domains which keeps the activation domain in an inactive state. Indeed, evidence for such an intramolecular inhibition has been documented (5, 25, 31). Thus, OBF-1 coactivation function may require an Oct-1-dependent unfolding of the protein to unmask the carboxy-terminal activation domain, and deletion of the amino-terminal region of the protein should therefore relieve inhibition and lead to Oct-1-independent activation. Figure 5C shows, however, that removal of the Oct-1-binding domain either alone (lane 2) or together with additional residues (lanes 3 and 4) does not render the carboxy-terminal activating region constitutively active. The same is observed when the mutants are connected directly to the carboxy-terminal end of a VP16-RFX derivative (data not shown). Hence, it is only in conjunction with DNA-bound Oct-1 that the C-terminal region of OBF-1 provides an activation function.

DISCUSSION

Study of the B-cell coactivator OBF-1 in the yeast S. cerevisiae has allowed us to rapidly map the boundary of the amino-terminal region required for binding of OBF-1 to Oct-1 in vivo and revealed the presence of a carboxy-terminal activation domain that confers to OBF-1 two uncommon functional properties. The carboxy-terminal border of the Oct-1 interaction domain was determined at single-amino-acid resolution by using a novel strategy. The approach consisted of generating a complex library of truncated OBF-1 proteins and identifying the smallest carboxy-terminal OBF-1 truncation that retains Oct-1-binding activity by using a transcription-based selection (Fig. 4A and B). This high-resolution deletion analysis is quite straightforward and should in principle be applicable to any protein domain whose activity can be scored in yeast. Surprisingly, while the Oct-1 interaction domain of OBF-1 has been mapped in vitro to the first 65 amino-terminal residues of the protein by gel retardation analysis (12), the region required for efficient OBF-1 recruitment by Oct-1 in vivo extends to amino acid 99. The reason for this discrepancy is not known. A possible explanation is that association of OBF-1 with Oct-1 on a chromatin template requires residues in addition to those that mediate direct contact with Oct-1 in vitro.

One of the striking features of the OBF-1 carboxy-terminal activation domain is that it exerts its effect only in association with DNA-bound Oct-1, not in the context of a heterologous DNA-binding protein. This finding contrasts with the observation that in mammalian systems, OBF-1 displays an intrinsic activation function when fused to the DNA-binding domain of Gal4. One possibility is that Oct-1 is present in mammalian cells at concentrations high enough to permit its recruitment to the promoter by OBF-1 linked to Gal4. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, the effect of the C-terminal region of OBF-1 may be obscured, at least on those promoters that have been examined, by other activators bound nearby or by the presence of additional, autonomously acting activation domains within OBF-1 that function in higher eukaryotes but not in yeast. Indeed, activating regions in addition to the C-terminal domain have been identified in OBF-1 (12, 31, 48). In some instances, these were reported to mediate most of OBF-1 transactivation function (12).

We cannot formally exclude the possibility that the Oct-1-dependent activity of OBF-1 in yeast reflects, as observed in mammalian in vitro transcription systems (26), a requirement for an Oct-1 activating region that cooperates with OBF-1 to stimulate transcription. However, the finding that OBF-1 retains most of its activity in association with either Oct-2, another POU transcription factor that bears no obvious sequence similarities with Oct-1 outside the POU domain (16), or the Oct-1 POU domain alone (data not shown) suggests that the predominant transactivation function resides within OBF-1 itself. We thus propose that activation is not obtained by simple recruitment of OBF-1 to DNA but requires interaction with DNA-bound Oct factors to bring the OBF-1 activation domain into an intramolecular context appropriate for activation.

Exactly how the carboxy-terminal activation domain of OBF-1 remains silent within the free protein and becomes functional after binding to Oct-1 is unknown. One possible explanation is that an intramolecular interaction keeps the activation domain in an inactive state. For example, serum response factor and ATF-2 contain separable activating regions that remain silent in the context of the full-length proteins when tethered to DNA by heterologous DNA-binding domains (20, 23). However, deletion of the native DNA-binding domains in these chimeras restores transcriptional activation, indicating that these regions exert inhibitory effects on the cognate activation functions within the free proteins (20, 23). Interestingly, a similar inhibitory role for the DNA-binding domain of Oct-4, a member of the POU family of transcription factors, has also been proposed (3). That such an intramolecular inhibition may occur within OBF-1 is supported by several observations. Mutations within the carboxy-terminal region of OBF-1 have been reported to enhance the ability of the protein to bind to the DNA–Oct-1 complex (25), and only the amino-terminal 118-amino-acid region of OBF-1, not the full-length protein, was found to bind DNA in the absence of the Oct-1 POU domain (5). Conversely, the C-terminal region of OBF-1 showed higher transcriptional activity than the full-length protein when tested as Gal4 fusions in mammalian cells (31). Taken together, these findings suggest that the Oct-1 interacting surface and the carboxy-terminal activating region may interact and thereby antagonize each other’s function. However, we obtained no evidence for an inhibitory conformation that would keep the C-terminal activating region in an inactive state, as both full-length OBF-1 and amino-terminally truncated forms lacking the Oct-1 interaction domain were inactive when recruited to the promoter by the heterologous DNA-binding protein RFX (Fig. 5C). The Oct-1-dependent activity of OBF-1 might therefore involve another mechanism.

The other striking feature of OBF-1 is that while having virtually no intrinsic activation potential when recruited to the his3 promoter by native Oct-1, it efficiently enhances the activity of Oct-1 derivatives made transcriptionally competent through fusion to activation domains such as VP16 or Gal4. Interestingly, we found that OBF-1 also stimulates (fourfold) VP16–Oct-1 activation of a target promoter bearing a single proximal octamer motif in mammalian cells (data not shown). That OBF-1 does not mediate this effect by simply stabilizing Oct-1 binding to its cognate site is supported by several lines of independent evidence. Perhaps the most compelling argument is the finding that a protein fragment containing the entire Oct-1 interaction motif, but lacking the C-terminal activation domain, loses all transcriptional activity (Fig. 4C). Such a deletion mutant should at least retain some activity if OBF-1 were to stimulate Oct-1 binding to its cognate sequence, particularly since a similar variant carrying multiple substitutions at the C terminus was reported to exhibit enhanced Oct-1 DNA binding activity (25). Hence, we propose that the major contribution of OBF-1 to Oct-1-dependent transcription is to provide an additional activation domain.

The property of the C-terminal activation domain to function only in synergy with other activation domains is somewhat unexpected in yeast, as activators that can stimulate transcription synergistically also direct significant gene expression when tested in isolation. Whether OBF-1 displays similar properties in mammalian cells remains unclear because the OBF-1 coactivation function has been tested on reporter genes containing, in addition to the promoter-proximal octamer site, downstream enhancer elements that may contain binding sites for activators providing additional activating functions masking those of OBF-1. However, in vitro studies using Oct-1-depleted HeLa nuclear extracts have shown that Oct-1 activation domains are necessary for OBF-1 coactivation, as the Oct-1 POU domain alone, although sufficient for tethering the coactivator to the promoter, fails to mediate OBF-1 transactivation (26). It therefore appears that OBF-1 provides a cryptic activation function that is strictly dependent on cooperation with other activation domains both in yeast and in mammals.

By which mechanism then does OBF-1 stimulate transcription? Accumulating evidence indicates that many activators work by recruiting components of the RNA pol II basal transcription machinery to promoter DNA (33). In yeast and, presumably, in higher eukaryotic organisms as well, the basal machinery is delivered to the promoter in the form of at least two subcomplexes, TFIID and a TFIIB-containing complex which may correspond to the holoenzyme (11, 33). Individual recruitment of either subcomplex suffices to strongly activate transcription from the wild-type his3 core promoter used in the present study (11), while corecruitment of both subcomplexes has only a minor synergistic effect (11a). On that promoter, OBF-1 exhibits essentially no intrinsic activation potential but it strongly synergizes with other activation domains such as VP16 and Gal4. These findings suggest that the coactivator may act at a step that follows promoter binding of TFIID and the holoenzyme—an event that is likely to be stimulated by classical activators including VP16 and Gal4—and that becomes limiting only after productive recruitment of TFIID and the holoenzyme to the promoter. Mice deficient for OBF-1 show no impairment of Ig gene transcription during B-cell development (21, 29, 42). Yet OBF-1 clearly provides nonredundant functions, as these mice show reduced numbers of B cells in peripheral lymphoid organs and lack well-developed germinal centers (21, 29, 42). It is therefore tempting to speculate that the as yet unidentified OBF-1 target genes contain distinctive core promoter structures at which the major rate-limiting step in transcription is selectively stimulated by the OBF-1 carboxy-terminal activation domain but not by conventional activators.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful to P. Matthias and R. A. Young for providing anti-Oct-1 and anti-TFIIB antisera. We also thank B. Amati for the plasmid encoding Myc-VP16, and we thank N. Lin-Marq, S. Clarkson, and W. Reith for critical reading of the manuscript.

A.K. was a recipient of a Roche Research Foundation fellowship and a Marie-Heim-Voegtlin fellowship. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babb R, Cleary M A, Herr W. OCA-B is a functional analog of VP16 but targets a separate surface of the Oct-1 POU domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7295–7305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau J, Xiao H, McCracken S, O’Hare P, Greenblatt J, Bentley D. Three functional classes of transcriptional activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2044–2055. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brehm A, Ohbo K, Scholer H. The carboxy-terminal transactivation domain of Oct-4 acquires cell specificity through the POU domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:154–162. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey M. The enhanceosome and transcriptional synergy. Cell. 1998;92:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cepek D, Chasman I, Sharp P A. Sequence-specific DNA binding of the B-cell-specific coactivator OCA-B. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2079–2088. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Struhl K. Saturation mutagenesis of a yeast his3 “TATA element”: genetic evidence for a specific TATA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2691–2695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi T, Carey M. Assembly of the isomerized TFIIA-TFIID-TATA ternary complex is necessary and sufficient for gene activation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2540–2550. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst P, Smale S T. Combinatorial regulation of transcription. I. General aspects of transcriptional control. Immunity. 1995;2:311–319. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher C, Heintz N, Roeder R G. Purification and characterization of OTF-1, a transcription factor regulating cell cycle expression of a human histone H2b gene. Cell. 1987;51:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford E, Strubin M, Hernandez N. The Oct-1 POU domain activates snRNA gene transcription by contacting a region in the SNAPc largest subunit that bears sequence similarities with the Oct-1 coactivator OBF-1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3528–3540. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Couto E, Klages N, Strubin M. Synergistic and promoter-selective activation of transcription by recruitment of transcription factors TFIID and TFIIB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8036–8041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Gonzalez-Couto, E., N. Klages, and M. Strubin. Unpublished results.

- 11b.Gonzalez-Couto, E., A. Krapp, and M. Strubin. Unpublished results.

- 12.Gstaiger M, Georgiev O, van Leeuwen H, van der Vliet P, Schaffner W. The B cell coactivator Bob1 shows DNA sequence-dependent complex formation with Oct-1/Oct-2 factors, leading to differential promoter activation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2781–2790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gstaiger M, Knoepfel L, Georgiev O, Schaffner W, Hovens C M. A B-cell coactivator of octamer-binding transcription factors. Nature. 1995;373:360–362. doi: 10.1038/373360a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harbury P A, Struhl K. Functional distinctions between yeast TATA elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5298–5304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herr W, Cleary M A. The POU domain: versatility in transcriptional regulation by a flexible two-in-one DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1679–1693. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herr W, Sturm R A, Clerc R G, Corcoran L M, Baltimore D, Sharp P A, Ingraham H A, Rosenfeld M G, Finney M, Ruvkun G. The POU domain: a large conserved region in the mammalian pit-1, oct-1, oct-2, and Caenorhabditis elegans unc-86 gene products. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1513–1516. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herschlag D, Johnson F B. Synergism in transcriptional activation: a kinetic view. Genes Dev. 1993;7:173–179. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer V, Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 1995;14:2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenuwein T, Grosschedl R. Complex pattern of immunoglobulin mu gene expression in normal and transgenic mice: nonoverlapping regulatory sequences govern distinct tissue specificities. Genes Dev. 1991;5:932–943. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansen F E, Prywes R. Identification of transcriptional activation and inhibitory domains in serum response factor (SRF) by using GAL4-SRF constructs. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4640–4647. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim U, Qin X F, Gong S, Stevens S, Luo Y, Nussenzweig M, Roeder R G. The B-cell-specific transcription coactivator OCA-B/OBF-1/Bob-1 is essential for normal production of immunoglobulin isotypes. Nature. 1996;383:542–547. doi: 10.1038/383542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klages N, Strubin M. Stimulation of RNA polymerase II transcription initiation by recruitment of TBP in vivo. Nature. 1995;374:822–823. doi: 10.1038/374822a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X Y, Green M R. Intramolecular inhibition of activating transcription factor-2 function by its DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1996;10:517–527. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lobo S M, Hernandez N. Transcription of snRNA genes by RNA polymerase II and III. In: Conaway R C, Conaway J W, editors. Transcription, mechanisms and regulation. New York, N.Y: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1994. pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Y, Ge H, Stevens S, Xiao H, Roeder R G. Coactivation by OCA-B: definition of critical regions and synergism with general cofactors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3803–3810. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo Y, Roeder R G. Cloning, functional characterization, and mechanism of action of the B-cell-specific transcriptional coactivator OCA-B. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4115–4124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J, Ptashne M. Deletion analysis of GAL4 defines two transcriptional activating segments. Cell. 1987;48:847–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller M M, Schreiber E, Schaffner W, Matthias P. Rapid test for in vivo stability and DNA binding of mutated octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’ prepared from transfected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6420. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen P J, Georgiev O, Lorenz B, Schaffner W. B lymphocytes are impaired in mice lacking the transcriptional co-activator Bob1/OCA-B/OBF1. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:3214–3218. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfisterer P, Zwilling S, Hess J, Wirth T. Functional characterization of the murine homolog of the B cell-specific coactivator BOB.1/OBF.1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29870–29880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ptashne M. How eukaryotic transcriptional activators work. Nature. 1988;335:683–689. doi: 10.1038/335683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranish J A, Hahn S. Transcription: basal factors and activation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts S G, Green M R. Activator-induced conformational change in general transcription factor TFIIB. Nature. 1994;371:717–720. doi: 10.1038/371717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robzyk K, Kassir Y. A simple and highly efficient procedure for rescuing autonomous plasmids from yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3790. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenfeld M G. POU-domain transcription factors: pou-er-ful developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 1991;5:897–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan A K, Rosenfeld M G. POU domain family values: flexibility, partnerships, and developmental codes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1207–1225. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sauter P, Matthias P. Coactivator OBF-1 makes selective contacts with both the POU-specific domain and the POU homeodomain and acts as a molecular clamp on DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7397–7409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholer H R. Octamania: the POU factors in murine development. Trends Genet. 1991;7:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90422-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schubart D B, Rolink A, Kosco-Vilbois M H, Botteri F, Matthias P. B-cell-specific coactivator OBF-1/OCA-B/Bob1 required for immune response and germinal centre formation. Nature. 1996;383:538–542. doi: 10.1038/383538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah P C, Bertolino E, Singh H. Using altered specificity Oct-1 and Oct-2 mutants to analyze the regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:7105–7117. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strubin M, Newell J W, Matthias P. OBF-1, a novel B cell-specific coactivator that stimulates immunoglobulin promoter activity through association with octamer-binding proteins. Cell. 1995;80:497–506. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Struhl K. Chromatin structure and RNA polymerase II connection: implications for transcription. Cell. 1996;84:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong M W, Henry R W, Ma B, Kobayashi R, Klages N, Matthias P, Strubin M, Hernandez N. The large subunit of basal transcription factor SNAPc is a Myb domain protein that interacts with Oct-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:368–377. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zwilling S, Dieckmann A, Pfisterer P, Angel P, Wirth T. Inducible expression and phosphorylation of coactivator BOB.1/OBF.1 in T cells. Science. 1997;277:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]