Abstract

Healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) affect the most vulnerable people in society and are increasingly difficult to treat in the face of mounting antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Routine surveillance represents an effective way of understanding the circulation and burden of bacterial resistance and transmission in hospital settings. Here, we used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to retrospectively analyse carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria from a single hospital in the UK over 6 years (n=165). We found that the vast majority of isolates were either hospital-onset (HAI) or HCAI. Most carbapenemase-producing organisms were carriage isolates, with 71 % isolated from screening (rectal) swabs. Using WGS, we identified 15 species, the most common being Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae . Only one significant clonal outbreak occurred during the study period and involved a sequence type (ST)78 K . pneumoniae carrying bla NDM-1 on an IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid. Contextualization with public data revealed little evidence of this ST outside of the study hospital, warranting ongoing surveillance. Carbapenemase genes were found on plasmids in 86 % of isolates, the most common types being bla NDM- and bla OXA-type alleles. Using long-read sequencing, we determined that approximately 30 % of isolates with carbapenemase genes on plasmids had acquired them via horizontal transmission. Overall, a national framework to collate more contextual genomic data, particularly for plasmids and resistant bacteria in the community, is needed to better understand how carbapenemase genes are transmitted in the UK.

Keywords: carbapenemase, ST78, long-read sequencing, plasmid, transmission, whole genome sequencing

Data Summary

The datasets [Illumina fastq reads, Oxford Nanopore basecalled (fastq) reads and hybrid assemblies] for this article are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under Project PRJEB31034 at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB30134. The software packages used to analyse these data are described in the Methods section of the paper. The clinical metadata, sample IDs and sample accessions are described in Tables S1 and S2, available in the online version of this article.

Impact Statement.

Infections caused by bacteria that are resistant to last-line antibiotics (such as carbapenems) can spread easily among patients, are more difficult to treat and are often associated with higher mortality than infections caused by antibiotic-sensitive bacteria. Early detection of these carbapenem-resistant bacteria is therefore essential in healthcare settings. We conducted a study of all carbapenem-resistant bacterial samples in a UK teaching hospital over a 6 year period. We found that most of the carbapenem-resistant samples came from hospital inpatients, or were healthcare-associated, and were detected by screening (using rectal swabs). We used DNA sequencing to identify the bacterial species, antibiotic resistance genes and plasmids (pieces of DNA carrying antibiotic resistance genes). We identified one outbreak caused by a highly antibiotic-resistant strain ( Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 78, which carried the bla NDM-1 gene on an IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid). We also found carbapenemase genes on plasmids in 86 % of samples, and evidence of transmission between different bacteria (horizontal transmission). These findings emphasize the potential threat of these organisms and the need for enhanced surveillance for these organisms in healthcare settings.

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a well-recognised global threat, exacerbated by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics and poor infection control practices [1]. While resistance in bacteria can manifest in different ways, gene-based resistance is of particular concern, as horizontal gene transfer via mobilizable elements can mediate rapid spread of resistance in a population [2, 3].

Carbapenems are a class of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents that are used to treat a range of infections. Over the last three decades, resistance to carbapenems has spread worldwide via an array of carbapenemase genes [4]. The consequence of this proliferation has been problematic in healthcare settings, with outbreaks of carbapenemase-producing bacteria reported globally [5–7].

Prior to 2000, the incidence of carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacterales in the UK was low [8]. Between 2003 and 2015, the main carbapenemase genes in circulation in the UK were bla KPC followed by bla OXA-48 and bla NDM. Following 2015, the number of reported carbapenemase-producers grew substantially, with the proportion shifting slightly in favour of bla OXA-48, with reduced numbers of bla KPC [9]. Klebsiella spp. and Escherichia coli remain the two species most often associated with carbapenemase genes [10]. To date, whole genome sequencing (WGS) has been used successfully in the UK to elucidate local outbreaks or to investigate targeted resistance mechanisms [11–15]. However, most of these studies have focused on a single carbapenemase gene and/or species [16, 17], and few have explored the complete range of carbapenemase genes and species from a single location over a significant period of time. This is important information at both an institutional and a national level, as it can provide valuable epidemiological evidence for the prevalence and circulation of carbapenemase genes locally, and subsequently be combined with existing public data to explore more widespread transmission.

In this study, we collected all carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria isolated in the diagnostic microbiology laboratory at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (CUH) between 2014 and 2020. Using both Illumina and Oxford Nanopore sequencing, we aimed to characterize the breadth of carbapenemase genes and species encountered in this setting and elucidate the exact genetic context of the carbapenemase genes and possible transmission of strains and/or plasmids. With this knowledge, we can improve our understanding of endemic carbapenemase genes, track their movements and design better infection control strategies.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This was a prospective observational cohort study conducted at CUH, a 1000 bed secondary and tertiary referral hospital in the UK. Clinical diagnostic samples and screening (rectal swab or stool) samples from hospital inpatients as well as samples referred from local General Practices (GPs), were collected from 1 November 2014 to 31 December 2020. In most cases, a single isolate for each unique species per patient was included in this study. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) screening polices within CUH changed during the course of the study. In 2014, CPE screening was based on risk factors as defined in the Public Health England guidance [18]. Full screening details can be found in File S1 (Supplementary Methods). Bacterial species were identified using MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Diagnostics). Isolates with reduced susceptibility to carbapenems were detected either through routine antimicrobial susceptibility testing of clinical diagnostic samples or the use of selective media (details in File S1: Supplementary Methods). Onset definitions are described in File S1 (Supplementary Methods).

Bacterial culture, DNA extraction and sequencing

Carbapenemase-producing isolates were retrieved from the diagnostic microbiology laboratory archive and cultured on selective media (CHROMID CARBA SMART; bioMérieux). Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were determined using the VITEK-2 system (bioMérieux). Genomic DNA was extracted using the QICube and the QIAamp 96 DNA QiACube HT kit (QIAgen). In total, 85/165 isolates were available for sequencing with both short (Illumina HiSeq) and long [Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION] read technologies (details in File S1: Supplementary Methods).

Sequencing quality control and assembly

Illumina raw reads were checked for quality and contamination using fastQC (v0.11.8) [19], MultiQC (v1.9) [20] and Kraken2 (v2.0.9-beta) [21]. Illumina raw reads were filtered using fastp (v0.20.1) [‘--average_qual 30 --length_required 80’] [22]. All Nanopore fast5 reads were basecalled and demultiplexed with Guppy (v3.6.0), using the ‘high-accuracy’ basecalling model and the relevant barcoding kit for demultiplexing. Basecalled reads were then filtered for quality using Nanofilt (v2.7.1) [23] at a threshold of Q7 and a minimum read length of 1000 bp. Isolates with >110× coverage were additionally subsampled down to 100× coverage using Filtlong (v0.2.0) (with --keep_percent 90 and --target_bases corresponding to 100× coverage for that isolate) [24]. All isolate Nanopore reads (original and subsampled) were de novo assembled using Flye (v2.8) (with --plasmids flag) [25], Unicycler (v0.4.8) (hybrid settings) [26] and Canu (v2.1.1) (default) [27]. The best assembly per isolate was selected, with a preference for Flye>Unicycler>Canu when the assemblies were comparable. Full details are provided in File S1 (Supplementary Methods).

Multilocus sequence type (MLST), resistance genes and plasmid profiles

MLST was determined using the hybrid assemblies and the tool mlst (v2.19.0) [28] with the following profiles: ( Acinetobacter baumannii Pasteur, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter, Escherichia coli Achtman, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [29]. Resistance genes and plasmid profiles were detected using the complete assemblies and Abricate (v1.0.1) [30] against the CARD (date: 27 March 2021) [31] and Plasmidfinder (date: 24 october 2020) [32] databases using a minimum coverage of 90 % and minimum nucleotide identity of 90 %. Tandem duplication of carbapenemase genes was confirmed by comparing the duplicated region to the raw (fastq) nanopore reads using BLASTn (v2.12.0) [33].

Species identification

In addition to Kraken2 (v2.0.9-beta), we also evaluated species identification for Klebsiella isolates using Kleborate (v0.4.0-beta) [34, 35] against the complete assemblies at default settings. Enterobacter isolates were also manually checked against reference Enterobacter species (NCBI) by comparing chromosomes using fastANI (v1.3) [36] with default settings.

Clonal cluster analysis

Clonal clusters were confirmed using three methods: Snippy (v4.6.0) [37] against a single reference for each species, Split Kmer Analysis (SKA v1.0.1) [38] and MASH (v.2.2.2) [39]. For Snippy, trimmed Illumina reads were mapped to a single reference chromosome for each species (the NCBI reference genome). Clusters at the species level with a low number of pairwise SNPs (<50) were re-tested with Snippy using an internal reference (to obtain a more accurate SNP distance). Complete chromosomes were also clustered using (i) MASH (sketch size 10 000) and (ii) SKA (default settings). Based on existing literature [40–42] and pairwise distances observed in our dataset (File S1: Fig. S1), the following thresholds were used: <20 SNPs (Snippy), MASH threshold 0.001, <25 SNPs and nucleotide identity of 95 (SKA). The final clusters were derived using a combination of the SKA and Snippy results.

Plasmid clustering

Complete plasmid sequences were clustered using Mash (v2.2.2) using a sketch size of 10 000 and a clustering threshold of 0.001 and 0.005 mash distance. Additional metadata, including plasmid incompatibility type [determined using PlasmidFinder (date: 24 October 2020) and Abricate v1.0.1] and plasmid length, were used to determine the likelihood of the two plasmids being ancestrally related within a short timeframe.

K. pneumoniae phylogeny

In total, 350 publicly available closely related isolates were downloaded from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA). These were identified by sketching a reference genome (cpe058) using sourmash (v3.5.0) [43] at a Kmer length of 31 bp and an interval of 5000 bp (‘-n 5000 k 31’) and querying against the sourmash index of 661 405 bacterial genomes [44] (full details in File S1: Supplementary Methods). All isolates were trimmed using fastp (v0.20.1) using the following settings: ‘--length_required 40 --cut_front --cut_tail -M 25’. After trimming, 12 isolates were removed for being <20× or >300× coverage. The 338 remaining were combined with trimmed reads for the 11 ST78 outbreak isolates from this study and simulated reads for an Indian ST78 isolate (NCBI: NZ_JAJBIZ010000100.1) [45] as well as three ST78 isolates from Pathogenwatch (accessed 3 May 2023, USA, 2017: SRR13085630 and SRR13085629; Germany, 2019: ERR3771764). Simulated reads were generated using Art_Illumina with the following parameters: ‘--noALN --seqSys HS25 --len 150 --fcov 50 --mflen 500 --sdev 25’ [45]. All reads were mapped to the chromosome of cpe058 and SNPs were called using Snippy (v4.6.0). The core full alignment generated from Snippy-core was then run through Gubbins (v3.3.0) [46] to remove recombination and generate a phylogeny using FastTree (v2.1.10) [47] under the GTRGAMMA model. The final tree was drawn in iTol [48].

Results

A total of 165 carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacterial isolates from 133 patients were collected in the study period. The majority of patients were male (n=78, 59 %) (Table 1) and the mean age for both men and women was approximately 54 years. The median length of inpatient stay was 18 days (range 0–156 days) and the majority of patients were alive on discharge (n=94, 71 %). Nine isolates (from nine patients) were collected from GPs in the Cambridgeshire area. The remainder were collected from CUH inpatients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

|

Patients (n=133) |

Male (n=78) |

Female (n=55) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) |

||

|

Average |

53.7 |

54.5 |

|

Median |

57 |

55 |

|

Range |

0–95 |

2–92 |

|

Length of stay (days)* |

||

|

Min. |

0 |

|

|

Median |

18 |

|

|

Average |

26.6 |

|

|

Max. |

156 |

|

|

Classification† |

||

|

Community-associated |

7 |

|

|

Hospital-onset |

54 |

|

|

Healthcare-associated |

69 |

|

|

CUH |

23 |

|

|

CUH and overseas hospital |

3 |

|

|

Overseas hospital |

17 |

|

|

Other UK hospital |

24 |

|

|

Other UK and overseas hospital |

2 |

|

|

Unknown: |

3 |

|

|

History of travel (previous 3 months) |

Travel only |

Travel and hospitalization |

|

Asia |

3 |

18 |

|

Africa |

1 |

5 |

|

Continental Europe |

2 |

9 |

|

Middle East |

0 |

1 |

|

UK |

3 |

0 |

|

Not recorded (n=7) |

||

|

Hospitalization (previous 12 months) |

Single site only |

Multiple hospitalization sites |

|

CUH |

51 |

7 (overseas) |

|

Other UK hospital |

37 |

3 (overseas) |

|

Overseas hospital |

23 |

0 |

|

Not recorded (n=1) |

||

|

Outcome (at hospital discharge) |

||

|

Alive |

94 |

|

|

Deceased |

13 |

|

|

Not recorded |

9 |

|

|

Not applicable‡ |

17 |

|

*Not applicable (GP sample): 9 patients; not applicable (no admission): 8 patients; unknown: 9 patients.

†Definitions: community-associated: isolated <48 h after admission – no previous hospitalization or medical treatment in past 12 months; hospital onset: isolated ≥48 h after admission; healthcare associated: isolated <48 h after admission and had previous hospitalization or medical treatment in last 12 months at (i) CUH, (ii) other UK hospital, (iii) overseas (last 3 months), or a combination of any of the three.

‡Patient was not admitted, so no discharge outcome.

The majority of patients were classified as having either hospital-onset (n=54, 41 %) or healthcare-associated (n=69, 52 %) infections (Table 1). Of these, roughly a third of patients had exposure to meropenem in the previous 3 months (19/54 hospital-onset, 22/69 healthcare-associated). Only seven (5 %) were community-associated (two from screening swabs, five from urine samples). In the 3 months prior to admission, 39 patients reported travel overseas (29 %) and three to other parts of the UK (2 %). Overall, most patients had been hospitalized within the last year, either in CUH (n=51, 38 %), in other UK hospitals (n=37, 28 %), or overseas (n=23, 17 %). Ten patients had both UK and overseas hospitalizations (seven in CUH and three in other UK hospitals).

High frequency of carbapenemase gene carriage

A total of 15 species were identified during the study, the majority of which were Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=54, 33 %) or Escherichia coli (n=55, 33 %) (Fig. 1a). Five patients had recurrent isolates that were included in the study (resulting in the following duplicates: eight K. pneumoniae , three Escherichia coli , two Enterobacter sp., one Citrobacter freundii and one Klebsiella oxytoca ).

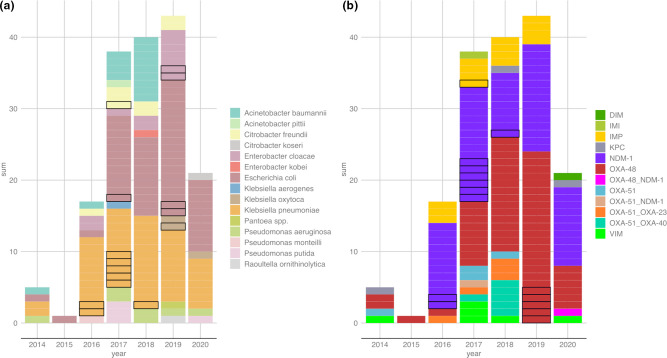

Fig. 1.

All carbapenemase-positive isolates collected over the study period and carbapenemase genes (n=165). Stacked bar plots showing (a) (left) count of species collected per year (determined using MALDI-TOF MS) and (b) (right) count of carbapenemase genes identified per year (determined using PCR). Sequential isolates of the same species (from the same patient) are outlined in black as possible duplicates. Positions of the stacked bars in (a) and (b) are independent.

The main carbapenemase genes detected were bla NDM-1 (n=65, 39 %) and bla OXA-48 (n=60, 36 %) (Fig. 1b). Most isolates (n=117, 71 %) were recovered from screening swabs. The remainder were isolated from urine (n=17), blood (n=9), biliary fluid (n=8), respiratory samples (n=6), wound swabs (n=5), body fluids (n=3), tissue (n=2) and central venous catheter tip (n=1). There was no association of species or carbapenemase gene with sample site (File S1: Fig. S2). There was also little association between infection classification and species or carbapenemase gene (File S1: Fig. S3). bla NDM-1- and bla OXA-48-harbouring E. coli and K. pneumoniae predominated in all infection categories.

Most isolates were found to have intermediate susceptibility or non-susceptibility to meropenem (File S1: Fig. S4). Notably, bla OXA-48-carrying isolates had the most variable levels of resistance, with a large portion, in particular E. coli , remaining susceptible to meropenem.

No significant change in the frequency of carbapenemase-producers during the study period

Despite an observed increase per year in carbapenemase-producers (Fig. 1), evaluating the number of isolates obtained per month in the context of adapted sampling procedures over different periods revealed little fluctuation in isolate numbers over time (File S1: Figs S5 and S6). In June 2016 a prospective screening study commenced in the adult intensive care unit (ICU) at CUH and identified an outbreak of bla NDM-1-positive K. pneumoniae (discussed below). This resulted in intensified screening (on admission and weekly thereafter) of all patients admitted to adult ICUs in CUH. A very slight decrease in the number of CPE isolates was observed from late 2019 throughout 2020, probably as a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (File S1: Fig. S6).

Travel had little impact on the species isolated or carbapenemase genes detected

When comparing isolates from patients with and without overseas travel, we found a preference for bla NDM (particularly bla NDM-1 E. coli ) in patients who travelled to Asia, and similarly bla OXA-48 in patients from central Europe (File S1: Fig. S7). Beyond this, there were very few differences in species and carbapenemase genes isolated based on travel. The most common species/carbapenemase gene combinations (bla NDM-1- and bla OXA-48-harbouring E. coli and K. pneumoniae ) were common in patients irrespective of travel history. There was a slightly larger proportion of bla NDM-1-harbouring K. pneumoniae in patients with no travel history; these were related to a hospital outbreak (discussed below).

Long-read sequencing to generate complete genomes

Of the 165 isolates, 85 (from 68 patients) underwent WGS with both short-read Illumina and long-read nanopore platforms, from which we were able to obtain complete bacterial genomes in most cases (File S2).

Using these genomic data, we re-evaluated the species identifications using Kraken2 as well as Kleborate (for the Klebsiella sp.) and fastANI (for Enterobacter sp.). All isolates were correct at the genus level, with 12 differences at the species level. These include two reclassifications of Klebsiella pneumoniae to Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae (cpe097) and Klebsiella oxytoca (cpe088), one Klebsiella oxytoca to Klebsiella grimontii (cpe102), one Enterobacter kobei to Enterobacter hormaechei (cpe050), five Enterobacter cloacae to Enterobacter hormaechei (cpe002, icp157, cpe042, cpe090, cpe093), one Enterobacter cloacae to Enterobacter mori (cpe018), and two Enterobacter cloacae to Enterobacter roggenkampii (cpe104, cpe106).

Enhanced resolution of the carbapenemase genes was also possible from the sequencing data, allowing better discrimination of the bla OXA and bla NDM alleles (Fig. 2). bla NDM-1 remained the most prevalent carbapenemase (n=19), but this was due to the bla NDM-1 K. pneumoniae outbreak during the study (n=11) (detailed below). bla NDM-5 (n=9) was the next most prevalent New-Delhi-metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) carbapenemase. The bla OXA-48 group was differentiated into three main types, with bla OXA-181 (n=11) the most prevalent, followed by bla OXA-48 (n=8) and bla OXA-232 (n=8). All other carbapenemase types were found less frequently, with 13/20 (65 %) found in two or fewer isolates. Four isolates that were originally positive for bla NDM (cpe078 and cpe020) and bla OXA-48 (cpe100 and cpe088) based on PCR had no detectable bla NDM or bla OXA-48 after sequencing. This may have been due to loss during subculturing or an error occurring during sample retrieval. These four isolates were not analysed further.

Fig. 2.

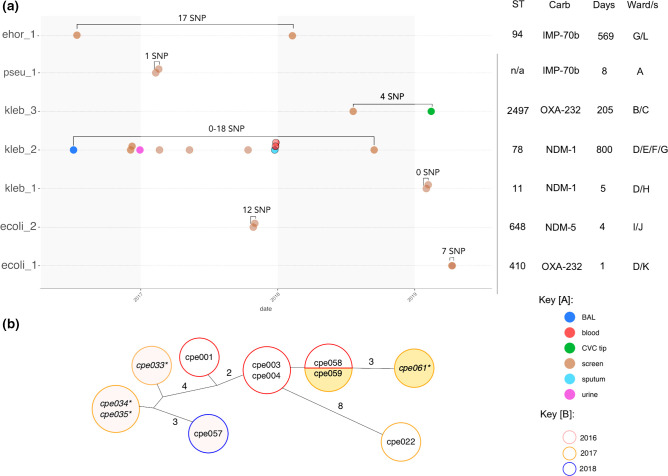

Clonal transmissions identified by WGS: (a) transmission cluster timeline. Species and cluster number provided on the y-axis (ehor= Enterobacter hormaechei , pseu= Pseudomonas putida , kleb= Klebsiella pneumoniae , ecoli= Escherichia coli ). Each row is a different outbreak group, with minimum and maximum core distances between all isolates noted above (as SNPs). The x-axis indicates year and approximate date of isolation. Isolates (circles) are coloured by sample site. Isolates outlined in black are duplicate isolates from patients with an existing earlier isolate. BAL=bronchoalveolar lavage, CVC=central venous catheter. The table on the right indicates sequence type (ST), carbapenemase gene, number of days the outbreak persisted (based on available isolates) and the number of affected wards (deidentified). (b) Minimal spanning tree of ST78 K. pneumoniae outbreak isolates. Isolates in the same circle were identical at core genome level. Lines represent core SNP distance (1 SNP unless otherwise noted). Circle outlines denote year of isolation. Circle fill colour identifies isolates from the same patient. Isolate names in italics with an asterisk (*) are duplicates isolated from patients already with this K. pneumoniae strain.

Variety of carbapenemase alleles and genetic background

Assessing carbapenemase alleles with their genetic background revealed a wide variety of combinations, which were in many cases unique to a single isolate (Fig. 3a). Further comparison to patient onset information revealed some combinations that appeared more commonly in isolates from patients who had travelled overseas versus those from the UK. These included the IncX3 bla OXA-181 plasmids, as well as some bla OXA-23/bla OXA-66 isolates from Acinetobacter baumannii and roughly half of the col bla OXA-232 isolates. The remainder were all hospital-onset or healthcare-associated in either CUH or other UK hospitals, with the large notable addition of the IncFIB/IncHI1B bla NDM-1 plasmid that was part of a known outbreak during the study (detailed below). Only one community-associated isolate was sequenced (a chromosomally encoded bla OXA-48 from an Escherichia oli).

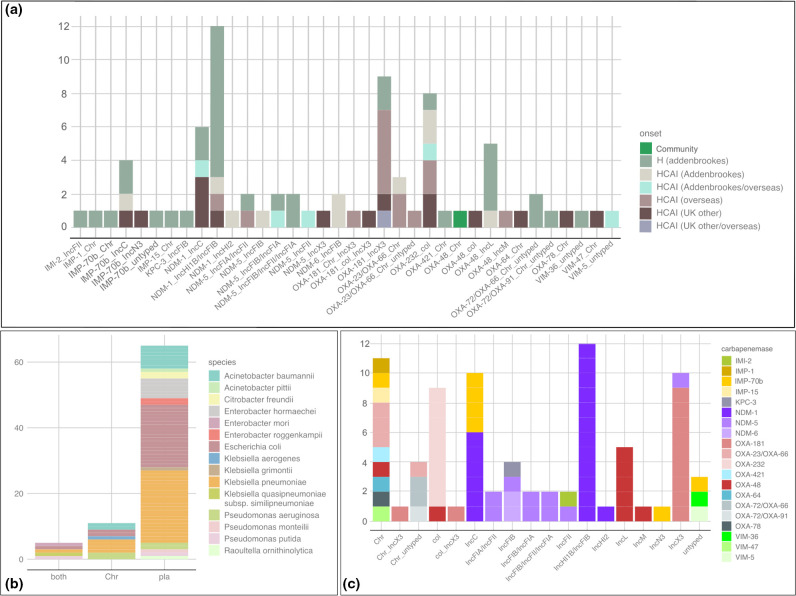

Fig. 3.

Stacked bar plots of carbapenemase alleles by (a) onset, (b) genomic location and (c) plasmid type. (a) The x-axis displays the carbapenemase allele and plasmid replicon type, coloured by onset status (H=hospital onset; HCAI=healthcare-associated) and location of the healthcare association (Addenbrookes=CUH, UK other=UK but non-CUH); (b) the x-axis describes whether the carbapenemase gene was found on the chromosome (Chr), a plasmid (pla) or both (coloured by species); (c) the x-axis describes location of carbapenemase genes (Chr=chromosome, otherwise specified by plasmid type). Instances of both chromosome and plasmid type indicate where a carbapenemase gene was found on both.

Most carbapenemase genes were located on plasmids

Of 81 isolates, 65 harboured their carbapenemase gene on a plasmid (Fig. 3b). The remaining 16 had their carbapenemase gene on the chromosome (n=11) or on both the chromosome and a plasmid (n=5). All carbapenemase genes had 100 % nucleotide identity to their assigned allele, with the exception of seven isolates carrying a bla IMP gene differing by seven SNPs from bla IMP-1 and one SNP from bla IMP-70 (labelled as bla IMP-70b in Fig. 3). The single non-synonymous SNP difference from bla IMP-70 corresponded to I228L.

There was a clear association of certain incompatibility types to carbapenemase genes (Fig. 3c). These include bla OXA-48 on IncL and IncM, bla OXA-232 on col, bla NDM-1 on IncC and IncFIB/IncHI1B, and bla OXA-181 on IncX3. Several isolates were also identified as harbouring multiple copies of the same carbapenemase gene (details in File S1: Table S1).

Few clonal transmissions were detected during the study period

Between 2016 and 2020, only seven clonal transmission clusters between different patients were detected from the WGS data (Fig. 2a). The majority of these involved only two patients (n=6) and include P. putida , E. coli (ST410, ST648), E. hormaechei (ST94) and K. pneumoniae (ST11, ST2497). Most of these outbreaks spanned less than 10 days, with the exception of two ST2497 K. pneumoniae that were isolated 205 days apart, and two ST94 E. hormaechei isolated 569 days apart. Apart from the P. putida isolates, all others were sampled from different wards. Of these events, only the large ST78 K. pneumoniae cluster and the P. putida cluster were detected by the hospital infection control team at the time. The remainder had no obvious epidemiological connections.

Outbreak of bla NDM-1-positive K. pneumoniae during the study period

In 2016, a large outbreak of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae was initially detected during a prospective surveillance study conducted in the adult ICU at CUH. Infection control investigations identified spread to several other wards. WGS identified the outbreak strain as an ST78 K. pneumoniae , carrying bla NDM-1 on a large ~300 kb IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid. Phenotypic testing found that these isolates (n=11) were resistant to a number of antibiotics, including amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, nitrofurantoin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ertapenem, meropenem, fosfomycin, gentamicin, amikacin and aztreonam. They had intermediate resistance to tigecycline and were susceptible to colistin. They carried a number of antibiotic resistance genes, including resistance to aminoglycosides [AAC(3)-Iid, AAC(6’)-Ib-cr, armA], cephalosporins (bla CTX-M-15), quinolones (qnrB17), trimethoprims (dfrA12) macrolides (mphE, msrE), sulphonamides (sul1), and tetracycline [tet(D)]. All isolates carried an OmpK36GD porin mutation associated with resistance to carbapenems [49]. Seven isolates had evidence of truncation of mgrB (cpe022, cpe003, cpe004, cpe033, cpe034, cpe035) or pmrB (cpe001) associated with resistance to colistin (despite phenotypic susceptibility). Four of these also carried aerobactin iuc1 (cpe004, cpe022) or iuc5 (cpe001, cpe003), but no other genetic markers for hypervirulence were observed [50].

Based on the WGS data obtained here, this outbreak involved at least seven patients from July 2016, with one patient testing positive again with the same organism in 2018 despite being sent home (Fig. 2b). As not all isolates from the study period were sequenced, it is also possible that other non-sequenced isolates from our dataset were also part of the outbreak (File S1: Fig. S8).

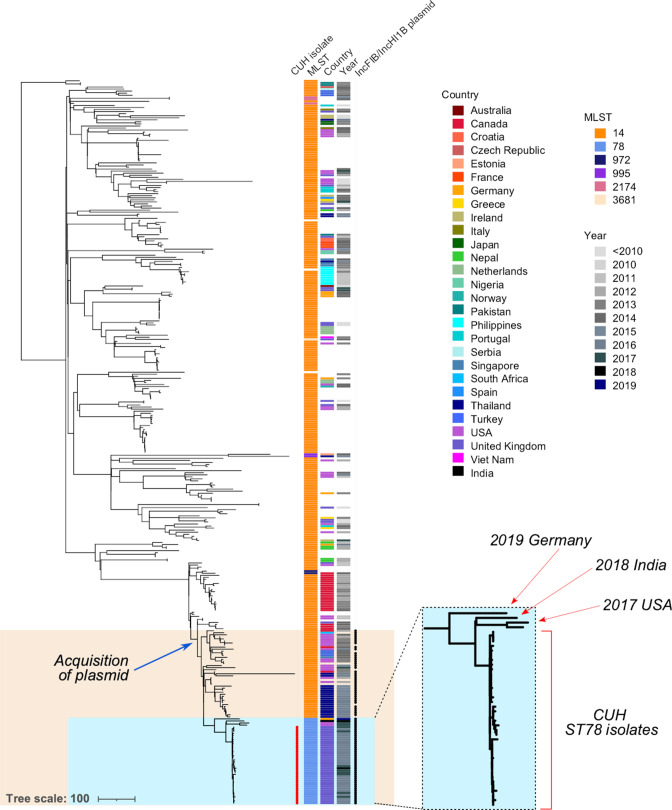

To provide further context to the outbreak, we interrogated a large public repository of 661 405 bacterial genomes collated up to 2018, which identified 352 broadly related isolates. Only 28 of these were identified as ST78, while the vast majority were found to be ST14, a single-locus variant of ST78 (File S1: Table S2).

Surprisingly, all of the available ST78 strains (n=28) from the public repository were also isolated at CUH and obtained in 2016 or 2017 as part of further intensive screening of the outbreak (Fig. 4, blue box). Only one isolate appeared to be a duplicate that was sequenced in both this study and a previous study (cpe001; ER2672819). As we did not expect to find only CUH isolates, we also downloaded all available K. pneumoniae assemblies from NCBI (11 811 sequences) and performed in silico MLST. None of these additional assemblies were found to be ST78. We then performed a literature search, which uncovered a single reported ST78 K. pneumoniae isolate from India in 2018 [51] which we then added to our analysis. We also inspected Pathogenwatch and found three additional isolates (two from the USA and one from Germany). All four additional isolates were positioned outside of the main ST78 outbreak clade in the phylogenetic tree, suggesting that they are indirectly related through a distant relative. Phylogenetic comparison to other contextual strains revealed that the closest relatives were of ST14, mainly from Thailand, the USA and Canada (Fig. 4). The index patient identified in CUH had no history of travel or hospitalization abroad in the 3 months prior to admission.

Fig. 4.

Phylogeny of ST78 outbreak strains and closest relatives from a repository of ~661 000 bacteria. Blue box: all available ST78 isolates, mainly isolated from CUH with four external ST78 isolates. Orange box: all isolates from this collection that harbour the IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid carrying bla NDM-1, acquired in an ST14 ancestor to the ST78 clade. Bar, number of substitutions.

We were also able to search the same public repository for isolates with a high likelihood of carrying the bla NDM-1 IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid based on >80 % matching kmer identities. We found 173 isolates all belonging to K. pneumoniae from a variety of STs, the majority being ST15, ST14 and ST78 (File S1: Fig. S9). The isolates with the highest identity to our plasmid were all from ST14 and ST78. We checked for the presence of bla NDM-1 in these isolates and found that 141 (82 %) carried the gene, which was found 100 % of the time in isolates with a kmer identity ≥95 %.

We then compared our plasmid results to our contextual isolates (Fig. 4) to identify those that carried the IncFIB/IncHI1B plasmid, with or without bla NDM-1. We found that only those strains closely related to the ST78 outbreak carried this plasmid, including the four non-CUH ST78 isolates (Fig. 4 , orange box;File S1: Fig. S10). Of these 65, only five did not carry a bla NDM gene. All other carried bla NDM-1. As such, acquisition of this plasmid probably occurred once in an ancestral ST14 isolate and has been stably maintained with infrequent loss (Fig. 4).

Combination of clonal and horizontal plasmid transmission, mixed with high background variability

In total, 70 isolates (86%) were found to carry a carbapenemase gene on a plasmid. By comparing plasmid sequences from these isolates and using a mash distance threshold of 0.001, we identified 44 isolates (from 31 patients) that had carbapenemase plasmids that clustered closely. These 44 isolates spanned 10 plasmid clusters (Table 2). Of the remaining 26 isolates, five formed clusters when applying a less strict threshold (0.005). The other 21 remained unique, resulting in a total of 31 plasmid backgrounds over the study period.

Table 2.

Carbapenemase plasmid clusters

|

Cluster |

No. of isolates |

Species |

Patients |

Carbapenemase gene |

Plasmid type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intra-patient transmission | |||||

|

Clust_217 |

4 |

Klebsiella grimontii, Enterobacter roggenkampii, Raoultella ornithinolytica |

1 |

OXA-181 |

IncX3 |

|

Clust_33 |

2 |

Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

1 |

NDM-6 |

IncFIB |

|

Clust_148* |

4 |

Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

2 |

NDM-1 |

IncC |

|

Clonal transmission | |||||

|

Clust_4 |

9 |

6 |

NDM-1 |

IncHI1B/IncFIB |

|

|

Horizontal transmission | |||||

|

Clust_133 |

2 |

2 |

OXA-72 |

Untyped |

|

|

Clust_17 |

Klebsiella aerogenes, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

3 |

OXA-48 |

IncL |

|

|

Clust_54 |

2 |

2 |

NDM-5 |

IncFIB/IncFIA |

|

|

Clust_72* |

8 |

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli |

8 |

OXA-232 |

Col |

|

Clust_9* |

3 |

3 |

IMP-70b |

IncC |

|

|

Clust_98 |

6 |

Escherichia coli, Enterobacter hormaechei, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

6 |

OXA-181 |

IncX3 |

*Contains some clonal transmission of bacterial strains in addition to horizontal transfer.

Broadly, there were three mechanisms identified in this dataset that explained why closely related plasmids were identified across multiple isolates: (i) clonal transmission, i.e. a bacterial strain infects or colonizes multiple hosts carrying the same plasmid; (ii) intra-patient transfer, where a plasmid has moved from one bacterial host to another within a single patient; and (iii) horizontal transfer between different bacterial species/strains detected outside of a single patient (Table 2). Two clusters (clust_217 and clust_33) appeared to be the result of intra-patient plasmid transfer between different colonizing species, as they were exclusive to a single patient. Two patients in cluster 148 (clust_148) appear to share the same ST11 K. pneumoniae strain but different Escherichia coli (ST10 and ST58), suggesting the K. pneumoniae transmitted between the patients first, after which the plasmid was transferred into different Escherichia coli strains in either patient. Cluster 4 (clust_4) was entirely the result of clonal transmission of the ST78 outbreak K. pneumoniae , rather than independent plasmid transfer. The largest cluster (clust_72) contained four clonally related isolates (two K. pneumoniae and two Escherichia coli ) alongside another four unrelated strains that all harboured a bla OXA-232-col plasmid. Based on this analysis, out of 70 isolates, 22 (31 %) carried plasmids with carbapenemase genes shared across different patients and as a result of historical or recent horizontal transmission (and not intra-patient transfer of the plasmid between hosts or clonal dissemination).

Looking across all plasmids in the dataset and clustering at the same mash threshold (0.001), we found a total of 51 clusters ranging from 2 to 11 isolates in size (median=2). The largest clusters were other plasmids associated with the ST78 K. pneumoniae outbreak strain (i.e. the result of clonal transmission). These were followed by the bla OXA-181 and bla OXA-232 plasmid clusters, as described above. There were no other non-carbapenemase-carrying plasmids that appeared highly prevalent across isolates.

There was limited evidence of smaller mobile genetic elements (MGEs) involved in horizontal transmission when examining the context of the carbapenemase genes in this dataset (data not shown). As such, we found that plasmids were the main vehicle of carbapenemase transmission in this study, both vertically (clonally) and horizontally.

Discussion

This study conducted a detailed analysis of carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria in a single UK hospital over 6 years. Overall, we found low rates of carbapenemase-producing organisms, and this did not appear to increase substantially during the study period. This is consistent with a previous point prevalence study, conducted in the same hospital, which found no CPE amongst 540 screening samples collected over a 3 day period in 2017 [52].

Additionally, we found very little evidence for the circulation of dominant lineages, and instead identified a variety of species carrying a range of carbapenemase alleles in different genetic backgrounds. Previous healthcare exposure (mainly at CUH) was a common feature among patients in this study and could be concluded as the main risk for infection with carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Indeed, a previous study looking at carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae across Europe found high levels of within-hospital spread [40]. However, if these were hospital-associated lineages, we might expect to see more frequent or consistent transmission over the 6 year timeframe, but instead we found limited transmission beyond a single patient.

Another possibility is independent introduction of these strains via patient carriage as a result of prior acquisition in other healthcare or community settings, which would explain the limited clonal transmission and high diversity we have observed. Carriage of carbapenemase genes is not uncommon, and can persist for prolonged periods of time, particularly following antibiotic exposure in hospitals [53, 54]. To verify this, we would need substantially more contextual data from the community and other healthcare settings. These areas represent gaps in our understanding of carbapenemase-producers nationally.

The few clusters that were detected during this study rarely exceeded two patients and most had no epidemiological support other than close temporal links within the same institution. This could indicate that transmission occurred in the hospital via an intermediate, such as contaminated surfaces or hospital staff [55]. Despite these seemingly benign transmissions, these cryptic events do reveal how easily bacteria can begin to spread undetected and in the absence of other epidemiological links. Early detection of spread is crucial to guide infection control interventions, and it can also have an enormous impact on healthcare costs [56]. Routine use of WGS provides a means to detect transmission early, but the costs and logistics have hampered routine adoption in healthcare settings [57]. Even in this study, we were unable to sequence all carbapenemase-producers, limiting our ability to investigate the relatedness of unsequenced isolates.

An easily searchable index of public data is crucial for outbreak analysis and public health interests. Blackwell et al. [44] provide a searchable index of all bacterial isolates from the ENA up to 2018, which enabled us to rapidly contextualize our ST78 K. pneumoniae outbreak strain. Coupled with all K. pneumoniae assemblies submitted to NCBI, we observed almost no publicly available ST78 isolates outside of those obtained at CUH, and only a few distant relatives [51]. While we do not have ENA data submitted after 2018, we would expect public data for ST78 to have existed prior to this if it had been reported elsewhere since the ST78 outbreak strain first appeared in CUH in 2016. Here we determined that this strain is extensively resistant to antibiotics but mostly lacking biomarkers for hypervirulence. Vigilance and further surveillance is required to monitor this ST and its possible expansion to other parts of the UK.

Finally, we used long-read sequencing to analyse plasmids in this study. Short-read sequencing is usually insufficient to confidently identify and compare plasmid sequences from whole genomes. Here, we were able to determine the number of shared and unique carbapenemase-carrying backgrounds between isolates, the majority of which were on plasmids. We found several plasmids of importance that have been identified elsewhere, including pOXA-48 [58], col_OXA-232 [59] and IncX3_OXA-181 [60]. By determining which isolates were related clonally, we could infer which plasmids were more likely to have been transmitted horizontally. However, we were unable to confidently predict whether horizontal plasmid transfer had occurred during or prior to hospitalization. Plasmids do not appear to follow the same mutation rate expected from clonally spreading strains, as evidenced by comparisons of pOXA-48 [61]. As such, distantly transferred plasmids can still have very few SNP differences. We also do not have access to susceptible strain information that could be used to identify the patient’s isolate prior to plasmid acquisition.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, the hospital screening policy and laboratory diagnostic methods for detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms changed over the course of the study period. This may have resulted in an underestimate of the true prevalence of these organisms, and/or an overestimation of hospital onset, since not all patients were screened on admission. Second, not all samples were stored in the diagnostic laboratory and/or available for sequencing. Third, we did not sample healthcare workers and did not routinely sample the environment as part of this study. Fourth, there was limited sampling (and associated metadata) outside the hospital setting. All of these factors may have affected our ability to detect and analyse all potential transmission events.

Nevertheless, we found considerable diversity of species in our dataset with minimal transmission and largely from carriage isolates. Our results suggest that these isolates may represent independent introductions into CUH. Detailed resolution using WGS and contextualization with public data allowed us to better construct clonal and plasmid relationships, particularly for an emerging extensively resistant ST78 K. pneumoniae lineage. However, a national framework to collate contextual data, particularly for plasmids and resistant bacteria broadly in the community, is needed to better understand how carbapenemase genes are transmitted in the UK.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

L.W.R. is an EBPOD Fellow funded by the European Bioinformatics Institute and the University of Cambridge. B.W. is supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. Z.I. is funded by EMBL core funding. M.E.T. is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship (funded by the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Health Foundation) and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the infection control team and the laboratory staff of the diagnostic microbiology laboratory at CUH. We also acknowledge Michael Hall and Martin Hunt for nanopore assembly advice.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.W.R., D.A.E., Z.I., M.E.T. Methodology: L.W.R., D.A.E., Z.I., M.E.T. Formal analysis: L.W.R., G.A.B., Z.I. Investigation: D.A.E., F.A.K., H.W., B.W., T.G., M.E.T. Resources: D.A.E., F.A.K., H.W., Z.I., M.E.T. Data curation: L.W.R., F.A.K., G.A.B., H.W., B.W. Writing – Original Draft: L.W.R. Writing – Review & Editing: all authors. Visualization: L.W.R. Supervision: Z.I., M.E.T. Project administration: Z.I., M.E.T. Funding acquisition: Z.I., M.E.T.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted as part of surveillance for healthcare-associated infections under the auspices of Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006. It therefore did not require individual patient consent or ethical approval.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; CUH, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; ENA, European Nucleotide Archive; GP, general practitioner; HAI, hospital-onset infection; HCAI, healthcare-associated infection; ICU, intensive care unit; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight MS; MGE, Mobile Genetic Element; NCBI, National Centre for Biotechnology Information; ONT, Oxford Nanopore Technologies; ST, sequence type; WGS, whole genome sequencing.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files. Ten supplementary figures, two supplementary tables and two additional files are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Browne AJ, Chipeta MG, Haines-Woodhouse G, Kumaran EPA, Hamadani BHK, et al. Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000-18: a spatial modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5:e893–e904. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheppard AE, Stoesser N, Wilson DJ, Sebra R, Kasarskis A, et al. Nested Russian doll-like genetic mobility drives rapid dissemination of the carbapenem resistance gene bla KPC . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:3767–3778. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00464-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David S, Cohen V, Reuter S, Sheppard AE, Giani T, et al. Integrated chromosomal and plasmid sequence analyses reveal diverse modes of carbapenemase gene spread among Klebsiella pneumoniae . Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:25043–25054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003407117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers AJ, Cox HL, Kitchel B, Bonatti H, Brassinga AK, Carroll J, et al. Molecular dissection of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae reveals Intergenus KPC carbapenemase transmission through a promiscuous plasmid. mBio. 2011;2(6):e00204–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00204-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naas T, Levy M, Hirschauer C, Marchandin H, Nordmann P. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii producing the carbapenemase OXA-23 in a tertiary care hospital of Papeete, French Polynesia. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4826–4829. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4826-4829.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souli M, Galani I, Antoniadou A, Papadomichelakis E, Poulakou G, et al. An outbreak of infection due to beta-Lactamase Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase 2-producing K. pneumoniae in a Greek University Hospital: molecular characterization, epidemiology, and outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:364–373. doi: 10.1086/649865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PHE PHE. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: laboratory confirmed cases, 2003 to 2015. [ October 10; 2016 ]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/carbapenemase-producing-enterobacteriaceae-laboratory-confirmed-cases/carbapenemase-producing-enterobacteriaceae-laboratory-confirmed-cases-2003-to-2013 n.d. accessed.

- 9.PHE PHE. English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) report 2019-2020. n.d.

- 10.Patel B, Hopkins K, Meunier D, Staves P, Hopkins S, et al. A ten-year review of Carbapenemase Producing Enterobacterales (CPE) in London, United Kingdom. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:s6–s7. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MTG, Quail MA, Nickerson EK, et al. Evolution of MRSA During Hospital Transmission and Intercontinental Spread. Science. 2010;327:469–474. doi: 10.1126/science.1182395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkins C, Dallman TJ, Launders N, Willis C, Byrne L, et al. Public health investigation of two outbreaks of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 associated with consumption of watercress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:3946–3952. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04188-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raven KE, Reuter S, Reynolds R, Brodrick HJ, Russell JE, et al. A decade of genomic history for healthcare-associated Enterococcus faecium in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Genome Res. 2016;26:1388–1396. doi: 10.1101/gr.204024.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuter S, Harrison TG, Köser CU, Ellington MJ, Smith GP, et al. A pilot study of rapid whole-genome sequencing for the investigation of a Legionella outbreak. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002175. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rew V, Mook P, Trienekens S, Baker KS, Dallman TJ, et al. Whole-genome sequencing revealed concurrent outbreaks of shigellosis in the English Orthodox Jewish Community caused by multiple importations of Shigella sonnei from Israel. Microb Genom. 2018;4:e000170. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludden C, Lötsch F, Alm E, Kumar N, Johansson K, et al. Cross-border spread of blaNDM-1- and blaOXA-48-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae: a European collaborative analysis of whole genome sequencing and epidemiological data, 2014 to 2019. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:20. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.20.2000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoesser N, Phan HTT, Seale AC, Aiken Z, Thomas S, et al. Genomic epidemiology of complex, multispecies, plasmid-borne Bla(KPC) Carbapenemase in Enterobacterales in the United Kingdom from 2009 to 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64 doi: 10.1101/779538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.PHE PHE. PHE carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae toolkit. 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/phe-carbapenemase-producing-enterobacteriaceae-toolkit-published

- 19.Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput squence data. 2010. https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

- 20.Ewels P, Magnusson M, Lundin S, Käller M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3047–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Coster W, D’Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2666–2669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wick RR. Filtlong. 2017. https://githubcom/rrwick/Filtlong

- 25.Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seemann T. mlst. 2013. https://githubcom/tseemann/mlst

- 29.Jolley KA, Maiden MCJ. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seemann T. Abricate, Github. https://github.com/tseemann/abricate n.d.

- 31.Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, Waglechner N, Guo P, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, et al. In Silico detection and typing of plasmids using plasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wyres KL, Wick RR, Gorrie C, Jenney A, Follador R, et al. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microb Genom. 2016;2:12. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam MMC, Wick RR, Watts SC, Cerdeira LT, Wyres KL, et al. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4188. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24448-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seemann T. Snippy: fast bacterial variant calling from NGS reads. 2015.

- 38.Harris SR. SKA: Split Kmer Analysis toolkit for bacterial genomic epidemiology. Genomics. 2018 doi: 10.1101/453142. [DOI]

- 39.Ondov BD, Treangen TJ, Melsted P, Mallonee AB, Bergman NH, et al. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016;17:132. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.David S, Reuter S, Harris SR, Glasner C, Feltwell T, et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0492-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherry NL, Lane CR, Kwong JC, Schultz M, Sait M, et al. Genomics for molecular epidemiology and detecting transmission of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in Victoria, Australia, 2012 to 2016. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e00573-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00573-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schürch AC, Arredondo-Alonso S, Willems RJL, Goering RV. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene-based approaches. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce NT, Irber L, Reiter T, Brooks P, Brown CT. Large-scale sequence comparisons with sourmash. F1000Res. 2019;8:1006. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19675.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blackwell GA, Hunt M, Malone KM, Lima L, Horesh G, et al. Exploring bacterial diversity via a curated and searchable snapshot of archived DNA sequences. PLoS Biol. 2021;19:e3001421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang W, Li L, Myers JR, Marth GT. ART: a next-generation sequencing read simulator. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:593–594. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, Delaney AJ, Keane JA, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–W296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fajardo-Lubián A, Ben Zakour NL, Agyekum A, Qi Q, Iredell JR. Host adaptation and convergent evolution increases antibiotic resistance without loss of virulence in a major human pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15:e1007218. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo TA, Olson R, Fang C-T, Stoesser N, Miller M, et al. Identification of biomarkers for differentiation of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from classical K. pneumoniae . J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00776-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00776-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul M, Narendrakumar L, R Vasanthakumary A, Joseph I, Thomas S. Genome sequence of a multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST78 with high colistin resistance isolated from a patient in India. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:187–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson HJ, Khokhar F, Enoch DA, Brown NM, Ahluwalia J, et al. Point-prevalence survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and vancomycin-resistant enterococci in adult inpatients in a university teaching hospital in the UK. J Hosp Infect. 2018;100:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lübbert C, Lippmann N, Busch T, Kaisers UX, Ducomble T, et al. Long-term carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-2-producing K pneumoniae after a large single-center outbreak in Germany. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evain S, Bourigault C, Juvin ME, Corvec S, Lepelletier D. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae digestive carriage at hospital readmission and the role of antibiotic exposure. J Hosp Infect. 2019;102:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dancer SJ. How do we assess hospital cleaning? A proposal for microbiological standards for surface hygiene in hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Otter JA, Burgess P, Davies F, Mookerjee S, Singleton J, et al. Counting the cost of an outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an economic evaluation from a hospital perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwong JC, McCallum N, Sintchenko V, Howden BP. Whole genome sequencing in clinical and public health microbiology. Pathology. 2015;47:199–210. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poirel L, Bonnin RA, Nordmann P. Genetic features of the widespread plasmid coding for the carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:559–562. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05289-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doi Y, Hazen TH, Boitano M, Tsai Y-C, Clark TA, et al. Whole-genome assembly of Klebsiella pneumoniae coproducing NDM-1 and OXA-232 carbapenemases using single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5947–5953. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03180-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mouftah SF, Pál T, Darwish D, Ghazawi A, Villa L, et al. Epidemic IncX3 plasmids spreading carbapenemase genes in the United Arab Emirates and worldwide. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1729–1742. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S210554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blackwell GA, Doughty EL, Moran RA. Evolution and dissemination of L and M plasmid lineages carrying antibiotic resistance genes in diverse Gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid. 2021;113:102528. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2020.102528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.