Abstract

Background:

Human trafficking is a human rights violation occurring around the world. Despite the profound social, health, and economic consequences of this crime, there is a lack of research about the prevalence and needs of human trafficking victims. The purpose of this study is to describe the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of human trafficking victims seeking services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic.

Methods:

A secondary analysis of the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic closed case files from 2009–2016 was performed. Data were extracted from the legal files to create a database and data analyses were completed using descriptive frequencies, logistic, and linear regression.

Results:

Data were extracted from 65 closed cases made up of 49 female victims(75.4%) and 16 male victims (24.6%) between the ages of 13 and 68 years old (M=30.15). Victims had experienced labor (56.9%) and sex (47.7%) trafficking. Logistic regression modeling indicated that trafficking experiences significantly influenced posttrafficking mental healthcare, social service, and legal needs.

Conclusions:

Victims of human trafficking have extensive needs; however, there are many barriers to seeking and receiving comprehensive services. In order to serve this vulnerable population, collaboration between disciplines must occur.

Keywords: human trafficking, health needs, service needs, interdisciplinary, human trafficking clinic

Background

Human trafficking, also known as modern slavery, is a human rights violation occurring around the world. Despite the potential for adverse health, social, and economic consequences related to this crime (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC], 2004, 2012), there is an abundance of myths and misperceptions about human trafficking and limited high-quality data. Human trafficking is defined as the recruitment, transportation, harboring, transfer, or receipt of individuals by force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of exploitation (United Nations, 2000). Trafficking of persons includes three elements: 1) the act, or what is done to a person; 2) the means, or how it is done; and 3) the purpose, or why it is done (United Nations, 2000; UNODC, 2017). When a child under the age of 18 years is induced to perform a commercial sex act then it is not necessary to prove force, fraud, or coercion in order to demonstrate that human trafficking has occurred (United Nations, 2000; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017; United States Department of State, 2016). Labor and sex trafficking are the two most common forms of human trafficking (United Nations, 2000). Labor trafficking can encompass many activities, including but not limited to, domestic servitude, agricultural labor, working in a restaurant, fishing, begging, construction, and factory work (Kiss, Yun, Pocock, & Zimmerman, 2015a; United States Department of State, 2016); while sex trafficking can occur in a variety of venues including, but not limited to, brothels, online, street-based, or at massage parlors (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017).

Human trafficking occurs in all 50 states in the United States and continues to be a global issue (Polaris, 2014). Trafficking can occur across international borders, domestic borders, and within cities, suburbs, or rural areas. Due to the secretive nature of trafficking, variation in definitions, and the lack of comprehensive data including both sex and labor trafficking, it is difficult to put a number on the number of people affected each year (Fedina, 2015; Fedina & DeForge, 2017; UNODC, 2015). Despite these limitations, organizations such as the International Labor Organization (2017) report that an estimated 40.3 million people were engaged in modern slavery (including forced labor and marriage) in 2016.

It is clear that both child and adult victims of human trafficking experience considerable abuse, resulting in the need for comprehensive physical, reproductive, and mental health care (Kiss et al., 2015b, 2015a; Ottisova, Hemmings, Howard, Zimmerman, & Oram, 2016; Turner-Moss, Zimmerman, Howard, & Oram, 2014). A recent systematic review of the mental, physical, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking (both labor and sex trafficking) identified that trafficking victims in contact with clinical services reported a high prevalence of violence during their trafficking experiences (Ottisova et al., 2016). Specifically, victims of sex trafficking experienced significantly higher rates of violence than sex workers (Ottisova et al., 2016). The systematic review by Ottisova et al. (2016) also highlighted significant mental health consequences (usually in the form of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression); physical health complications (usually in the form of headache, back pain, stomach pain, dental pain, and dizziness); and sexual health problems (including HIV and sexually transmitted infections among sex trafficking victims). Significant violence and mental health consequences have also been documented among children and adolescents in Southeast Asia (Kiss et al., 2015a).

Human trafficking takes a tremendous toll on many aspects of one’s health. However, there is a gap in the literature regarding the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of victims seeking services, especially as it relates to their pre-trafficking experiences. The purpose of this study is to describe the compiled healthcare, social service, and legal needs of human trafficking victims utilizing the services of the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic while taking into account their personal characteristics of trauma and history of trafficking.

Methods

Design

This study is a secondary analysis of 65 closed case files collected by the University of Michigan Law School’s Human Trafficking Clinic. The University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic was launched in 2009, as the first clinical law program providing comprehensive legal services to victims of human trafficking. Law students, supported by law faculty, serve clients who have experienced both domestic and international trafficking to address a wide range of legal needs (including expunging records, immigration relief, obtaining social services, witness testimony, and child custody). The University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic provides services to victims of human trafficking or attempted trafficking who cannot afford an attorney on their own.

This secondary analysis was intended to evaluate the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of victims of trafficking who seek legal services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic. Prior to the creation of a de-identified database for this study, ethical approval was obtained from the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

The University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic maintains the legal files for all clients they serve. However, this data can take a number of different formats including meeting notes, police reports, medical charts, and legal documents. Since the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic is focused on providing client services from a legal perspective rather than collecting data for research purposes, intake data was not collected in a standardized fashion. Therefore, each case file is extremely unique and tailored to the client’s needs.

Data were extracted by four research assistants using a standardized form (available upon request) developed by the research team. Inclusion criteria included: (1) client at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic and (2) legal case had been closed. The standardized form included six general categories: demographics, service history, trauma history, trafficking history, physical and behavioral health history, and service needs and outcomes. Each category included a subset of questions that ascertained whether or not a victim had experienced an event or received a service based on what was captured in the legal records. Since we were depending on the written records to capture certain aspects of the case there were many data points with missing data or where a variable was categorized as unknown. We also could not determine whether something was missing because it was not recorded in the lawyer’s files or did not actually occur or exist. For this reason, we took a conservative approach to determining whether exposures and outcomes were present among our sample and only analyzed data that were endorsed in the client’s legal records. This is consistent with the medico-legal presumption that information not noted in clinical records is assumed to be not present (Low, Seng, & Miller, 2008). We therefore utilized a binary coding process where 1 = yes and 0 = no/unknown. Given that we used these variables to create composite scores of different forms of abuse (child and adult), health outcomes (mental and physical), and service needs (healthcare, legal, and social service) the collapsing of no/unknown variables did not impact the total score of these predictors and outcomes.

Data were extracted from client records by two graduate research assistants (DB & KC) using a standardized paper data extraction form. The research assistants utilized a large majority of the information within each case file including, but not limited to court testimonies, police reports, visa or public benefit applications, and email correspondences. Extracted data from case files were inserted into the standardized form. Data from the standardized extraction forms were then transferred into an Excel database by two undergraduate research assistants (RS & AG). The undergraduate research assistants also performed interrater reliability on 10% of the cases for fidelity. The research team met regularly to discuss questions throughout the data extraction process.

Research personnel did not directly communicate with the victims; therefore, all data were obtained from pre-existing legal case files. Case files were stored on a secure server and data was retrieved on secure laptops with individual identifications and password protection. Access rights were terminated when authorized users left the project. Extracted data was de-identified and password protected.

Operationalization of Variables

Prior to data extraction, the research team agreed upon the operational definitions to be used during data extraction. The following definitions and extraction questions were used to identify whether or not a predictor variable was reported in the legal files (coded as yes) or was not reported (coded as no/unknown).

-

Type of trafficking:

Labor and sex trafficking were defined according to the United States Department of State (2016) definitions.

- Childhood abuse was operationalized using seven dichotomous variables, which were combined to create a composite score. The definitions of childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse as well as neglect used by the child welfare system were utilized (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). The variables were defined as follows.

- Childhood physical abuse was defined as any nonaccidental physical injury to the child (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). The data collection form specifically asked, Does the client report any physical abuse before the age of 18 (e.g., hitting, kicking, punching)?

- Childhood sexual abuse was defined as engaging in sexual contact or sexual penetration with a parent, legal guardian, or person responsible for the well-being of the child. The data collection form specifically asked, Does the client report any sexual abuse before the age of 18 (e.g., sexual touching, oral, anal, or genital sex)?

- Childhood emotional abuse was defined as inflicting emotional damage on a child. The data collection form specifically asked, Does the client report any emotional abuse before the age of 18 (e.g., being shamed, ignored, told that they were no good)?

- Childhood neglect was defined as negligent treatment by a parent, legal guardian, or person responsible for the well-being of the child. The data collection form specifically asked, Does the client report any neglect before the age of 18 (e.g., not having enough food, clothes, or supervisions and support)?

- Childhood domestic violence exposure was defined as witnessing violence between parents or other family members. The data collection form specifically asked, Does the client report any domestic violence exposure before the age of 18 (e.g., violence between parents or other family members)?

- Childhood war, terrorism, political violence exposure or extreme poverty was included to capture other forms of violence and trauma that clients may have experienced in their childhood. The data collection form asked, Does the client report any exposure to war, political violence, terrorism, or extreme poverty before the age of 18?

- Childhood abuse, other – Does the client report any other abuse or trauma before the age of 18?

- Abuse during trafficking was captured using eight forms of mistreatment, which were captured in a dichotomous fashion as being present or not. These were then summed to create a total score. The forms of mistreatment reported by clients within the database included:

- Physical abuse was defined nonaccidental physical injury inflicted upon the victim during their trafficking experience. The data collection form asked, Did the client report any physical abuse that happened while the trafficking took place?

- Sexual abuse was defined as non-consensual or coerced sexual contact or penetration during their trafficking experience. The data collection form asked, Did the client report any sexual abuse that happened while the trafficking took place?

- Emotional or psychological abuse was defined as using tactics such as bullying, threats, gaslighting, shaming, and blaming to control a person that may result in psychological trauma. The data collection form asked, Did the client report any emotional or psychological abuse that happened while the trafficking took place?

- Restriction on movement – Did the client report any confinement or restriction on movement that happened while the trafficking took place? Note: This does not include confiscation of personal documents.

- Poor living conditions – Did the client report any poor or inhumane living conditions while the trafficking took place?

- Poor working conditions – Did the client report any poor or inhumane working conditions while the trafficking took place?

- Wage deprivation – Did the client report any wage deprivation while the trafficking took place?

- Confiscation of personal documents – Did the client report confiscation of identification or other personal documents while the trafficking took place?

- Drugging – Was the client drugged as a means of coercion?

- Health problems:

- Physical health problems were captured with an aggregate score that captured the five following health problems as being present or not: HIV, sexually transmitted infections, acute illnesses (e.g., headaches, gastrointestinal disorders such as constipation and gastrointestinal upset), chronic illnesses/diseases (e.g., chronic pain, cancer), and injuries. These were captured as being present prior to seeking care at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic.

- Mental health problems were also captured by creating an aggregate score of the presence or absence of the following 18 mental and behavioral health disorders based on the client self-report or documentation via medical records that may have been present in the legal records: post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, attachment disorder, dissociation, panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, sleep disorder, sexual behavior problems, suicidality, self-injurious behavior, alcohol use, and illicit substance use. These were captured as being present prior to seeking care at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic.

The dependent variables were defined as follows:

Physical health needs captured any physical health need that a client described while receiving legal services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic. This ranged from chronic pain to routine gynecological care.

Mental health needs captured any mental health need that a client expressed while receiving legal services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic. This often included counseling and/or treatment for anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse.

Social service needs captured a range of other services that clients were in need of while seeking services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic including: public benefits, debt or finance assistance, internet or social media privacy assistance, food assistance, obtaining insurance, housing, child welfare, transportation, obtaining education, employment assistance, and personal identification documents.

Legal needs captured a range of legal services provided by the students and faculty at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic including: t-visa, u-visa, other immigration needs, family legal services, legal services related to work or school, obtaining a personal protection order, name change, criminal legal services, and testimony assistance.

Data Analysis

After data extraction and entry was complete, all data was transferred into SPSS (v. 22); all p-values were set at ≤.10 due to the small sample size to identify potential trends in outcomes. Data analyses were completed using descriptive frequencies, bivariate analyses, a correlation matrix, logistic regression, and linear regression. In order to understand the predictors that influenced healthcare use, we evaluated logistic regression models for physical health needs (the client had one or more physical health need) and mental health needs (the client had one or more mental health need). Due to the nature of the data, bivariate analyses were used to determine predictors in variables where there was not a significant amount of missing data. In order to understand the predictors that influenced legal and social service use, we utilized a linear regression model for total social service and legal needs (Range 0–9). A correlation matrix was used prior to the linear regression modeling to identify significant predictor variables. Since this was a secondary analysis of data that was not originally collected for research purposes we decided not to impute values for analysis. Potential predictor variables included in the bivariate analyses and correlation matrix were gender, a history of child abuse, adult physical health problems, adult mental health problems, and trafficking history experiences. Significant variables were then included in logistic regression models for the physical and mental healthcare needs outcome and significant variables from the correlation matrix were included in the linear regression model for the social service and legal needs outcome.

Results

A total of 65 closed cases were analyzed with 97.6% agreement achieved on all cases related to service needs. The sample included 16 men and 49 women who were between the ages of 7–53 years old with a mean age of 23.18 (SD 11.88) when they were first trafficked (see Table 1). The range representing the age when people first sought services at the University of Michigan Law School Human Trafficking Clinic was between 13–68 years old, with a mean age of 30.15 (SD 13.31).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (n = 65).

| Characteristic | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49 | 75.4 |

| Male | 16 | 24.6 |

| Country of Origin | ||

| United States | 19 | 29.2 |

| Other* | 46 | 70.8 |

| State of Residence | ||

| Michigan | 41 | 63.1 |

| Outside of Michigan | 24 | 36.9 |

| Type of Trafficking ** | ||

| Labor | 37 | 56.9 |

| Sex | 31 | 47.7 |

| Relationship to Trafficker (for incident that led them to seek services at the University of Michigan) | ||

| Relative or family friend | 6 | 9.2 |

| Friend/acquaintance | 10 | 15.4 |

| Significant other | 10 | 15.4 |

| Stranger | 21 | 32.3 |

| Unknown/Missing | 18 | 27.7 |

| Abuses Experienced during Trafficking | ||

| Physical | 34 | 52.3 |

| Sexual | 33 | 50.8 |

| Emotional | 45 | 69.2 |

| Restriction on movement | 39 | 60.0 |

| Poor living conditions | 36 | 55.4 |

| Poor working conditions | 40 | 61.5 |

| Wage deprivation | 47 | 72.3 |

| Drugged as means of coercion | 11 | 16.9 |

| Confiscation of personal/legal documents | 20 | 30.8 |

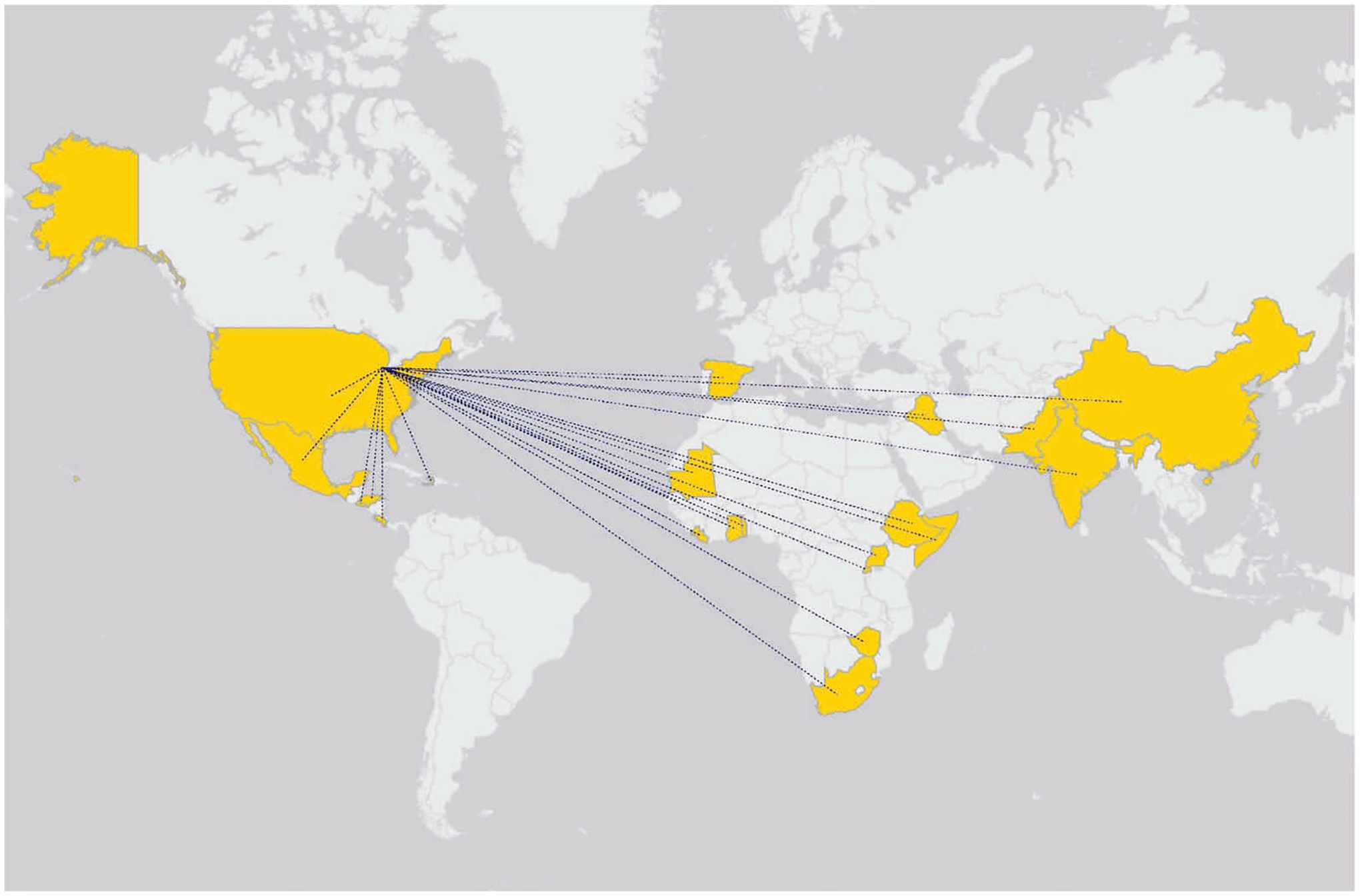

See Figure 1 for additional details

Values exceed 100% because some individuals experienced more than one form of trafficking

Clients in our sample were trafficked from countries outside of the United States (70.8%) as well as from within the United States (29.2%; see Figure 1 for additional details). Countries that clients had been trafficked from included: China (4.6%), Costa Rica (1.5%), El Salvador (1.5%), Ethiopia(1.5%), Ghana (4.6%), Haiti (1.5%), Honduras (1.5%), India (3.1%), Iraq (1.5%), Liberia (3.1%), Mauritania (1.5%), Pakistan (1.5%), Rwanda (1.5%), Senegal (1.5%), Somalia (1.5%), South Africa(1.5%), Spain (4.6%), Togo (10.8%), Uganda (1.5%), or Zimbabwe (1.5%).

Figure 1.

Map of countries from which trafficking victims originated.

The sample included those who had been exploited in labor (56.9%) and sex (47.7%), trafficking. The majority of the sample reported trafficking instances of one time (58.5%), with a few clients who reported two trafficking instances (7.7%) or three trafficking instances (1.5%). Relationship to one’s trafficker in our sample included relative or family friend (9.2%), friend/acquaintance (15.4%), significant other (15.4%), stranger (32.3%), and was unknown/missing in some (27.7%) of the cases examined.

Throughout their trafficking experience, the sample had experienced a number of abuses. These included physical (52.3%), sexual (50.8%) and emotional (69.2%) abuse. A large portion of the sample also experienced restriction on movement (60%), poor living conditions (55.4%), poor working conditions (61.5%), or wage deprivation (72.3%) throughout their trafficking experience. Within the legal files, there were reports that the sample had been coerced or retained in their trafficking experience through drugs (16.9%) or confiscation of personal documents (30.8%).

The victims also had a number of healthcare, social service, and legal needs (see Table 2 for additional information). For instance, nearly one quarter of the victims needed physical (21.5%) or mental (21.5%) healthcare while about one third needed family legal services (30.8%) or criminal legal services (35.4%). However, the most common need among the victims seeking services at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic was a t-visa (44.6%) or other immigration services (47.7%). While the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic was extremely effective in resolving the social service and legal needs of the victims, there were lower rates of resolution of the physical (57.1%) and mental (16.7%) healthcare needs.

Table 2.

Summary of client healthcare, social service, and legal needs (n/%).

| Assistance Needed from Legal Clinic | Had Need | Resolved | Resolved by Clinic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical healthcare | 14 (21.5%) | 7 (50.0%) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Mental healthcare | 14 (21.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| T-Visa | 29 (44.6%) | 18 (75.0%) | 17 (73.9%) |

| U-Visa | 3 (4.6%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (100.0%) |

| Public Health Benefits | 9 (13.8%) | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (100.0%) |

| Family Legal Services | 20 (30.8%) | 7 (36.8%) | 7 (100.0%) |

| Work or School Legal Service | 11 (16.9%) | 10 (90.9%) | 9 (90.0%) |

| Debt or Finance Legal Service | 13 (20.0%) | 3 (4.6%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Personal Protection Order | 4 (6.2%) | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (50.0%) |

| Name Change Legal Services | 9 (13.8%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Internet or Social Media Privacy | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Criminal Legal Service | 23 (35.4%) | 8 (44.4%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Food Assistance | 11 (16.9%) | 8 (88.9%) | 8 (100.0%) |

| Insurance | 7 (10.8%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (100.0%) |

| Housing | 11 (16.9%) | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Child Welfare | 2 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Transportation | 6 (9.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Education | 15 (23.1%) | 7 (46.7%) | 3 (42.9%) |

| Employment Assistance | 12 (18.5%) | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Immigration | 31 (47.7%) | 14 (45.2%) | 13 (92.9%) |

| Personal ID/Driver’s License | 3 (4.6%) | 3 (100.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Testimony assistance, victim impact statement, public speaking, media interviews | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

Bivariate and Correlation Analyses

Due to the small sample and exploratory nature of this project, bivariate and correlation analyses that indicated a significance at the level of < .10 were included in the logistic and linear regression models.

For the physical health needs, the following variables indicated trends towards significance in the bivariate analyses: (1) gender, χ2(1) = 2.936, p = .087; (2) total number of adult physical health problems, χ2(3) = 7.799, p = .050; and (3) total number of adult mental health problems, χ2(6) = 11.073, p = .086. The following variables were not significant for physical health needs and were therefore not included in the logistic regression model: (1) total number of child abuse experiences, χ2(6) = 4.384, p = .625 and (2) total number of trafficking abuses experienced, χ2(10) = 10.359, p = .410 The following variables indicated trends towards significance for mental health needs: (1) total number of adult physical health problems, χ2(3) = 6.748, p = .091, and (2) total number of trafficking abuses experienced, χ2(10) = 16.913, p = .076. The following variables were not significant for mental health needs and were therefore not included in the logistic regression model:(1) gender, χ2(1) = .098, p = .755; (2) total number of child abuse experiences, χ2(6) = 8.805, p = .185; and (3) total number of adult mental health problems, χ2(6) = 9.933, p = .128.

A correlation matrix with the predictor variables of gender, total number of child abuse experiences, total number of adult physical health problems, total number of adult mental health problems, and total number of trafficking abuses experienced was used to identify significant predictors for the outcome, total social service needs and total legal needs (Table 3). The correlation matrix for total social service needs indicated a trend towards significance with the following predictors: total number of child abuse experiences (r = −.271, p = .036), total number of adult mental health problems (r = .258, p = .046), and total number of trafficking abuses experienced (r = .242, p = .063). The correlation matrix for total legal needs only indicated a significant relationship with the predictor, total trafficking abuses experienced (r = .264, p = .042).

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

| Gender | Education | Total Number of Child Abuse Experiences | Total Number of Adult Abuse Experiences | Total Number of Adult Physical Health Problems | Total Number of Adult Mental Health Problems | Total Trafficking Experiences | Total Social Service Needs | Total Legal Needs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | .213 | .042 | −.276** | −.197 | −.225* | −.149 | −.201 | −.087 |

| Total Number of Child Abuse Experiences | - | −.523*** | −.296* | −.365** | −.465*** | −.271** | .019 | ||

| Total Number of Adult Abuse Experiences | - | .486*** | .485*** | .443*** | .126 | −.057 | |||

| Total Number of Adult Physical Health Problems | - | .427*** | .282** | .206 | −.128 | ||||

| Total Number of Adult Mental Health Problems | - | .047 | .258** | −.134 | |||||

| Total Trafficking Experiences | - | .242* | .264** | ||||||

| Total Social Service Needs | - | .190 | |||||||

| Total Legal Needs | - |

Significant at p < .10

Significant at p < .05

Significant at p < .001

Modeling

A binary logistic regression model was used to model mental health needs (Table 4). The total number of trafficking abuses experienced made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model (OR = 1.704, 95% CI: 1.106–2.624). This indicated that respondents who had history of more trafficking experiences were more likely to report a need for mental health care. The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, χ2(2) = 13.943, p = .001, indicating that the model could distinguish between respondents who reported and did not report a mental health problem. The model as a whole explained 31.1% (R2) of the variance in mental health care needs. A second binary logistic model (Table 4) evaluated predictors for physical health needs. This model did not have any significant predictors and the overall model was not significant, χ2(3) = 5.071, p = .167.

Table 4.

Logistic regression results.

| Logistic Regression of Mental Healthcare Needs Independent Variable | B | SE | p-value | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of adult physical health experiences | .494 | .420 | .239 | 1.639 |

| Total number of trafficking experiences | .533 | .220 | .016 | 1.704 |

| Constant | −5.348 | 1.651 | .001 | .005 |

| Logistic Regression of Physical Healthcare Needs Independent Variable | B | SE | p-value | Exp(B) |

| Gender | −1.358 | 1.114 | .223 | .257 |

| Total number of adult physical health problems | .614 | .439 | .163 | 1.847 |

| Total number of adult mental health problems | −.025 | .233 | .914 | .975 |

| Constant | −.344 | 1.362 | .801 | .709 |

Multiple regression was used to test if the variables total number of child abuse experiences, total number of adult mental health problems, and total number of trafficking abuses experienced predicted a client’s social service needs. The results of the regression indicated that the predictors explained 16.5% of the variance (R2 = .165, F(1,63) = 4.020, p = .011). In the final model, none of the individual predictors remained statistically significant. A simple linear regression was used to test if the computed variable, number of trafficking abuses experienced, predicted a client’s legal needs. The results of the regression indicated that the predictor, total trafficking abuses experienced, explained 7.1% of the variance [R2 = .071, F(1,63) = 4.820, p = .032]. It was found that the total number of trafficking abuses experienced predicted legal needs (b = .134, p = .032).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that victims of human trafficking seeking services at the University of Michigan’s Human Trafficking Clinic have suffered a number of abuses throughout their trafficking experience. This is consistent with past research that has identified that victims of human trafficking may experience abuses throughout multiple stages of the trafficking process including during travel and transit, exploitation, and potentially in re-integrating or integrating back into their communities (Zimmerman, Hossain, & Watts, 2011). A systematic review by Oram and colleagues (2012) also noted high rates of physical and sexual violence that resulted in physical, mental, and sexual health problems among both sex and labor trafficking victims. It is clear that these abuses have the potential to influence post-trafficking healthcare needs. This was supported by our data, which found that trafficking abuses experienced were the only factors that remained significant in the model predicting mental healthcare and legal needs.

Research has also documented that a history of childhood abuse is linked to becoming a trafficking victim (Oram, Khondoker, Abas, Broadbent, & Howard, 2015; Varma, Gillespie, McCracken, & Greenbaum, 2015). Victims of human trafficking are often targeted because of their vulnerabilities (United States Department of State, 2016). Despite this link in the literature, a history of child abuse was not a significant predictor of healthcare or legal needs after trafficking in this study. Furthermore, mental and physical healthcare history did not influence physical healthcare needs. It is possible that child abuse and mental and physical health history were not significant due to the small sample size or potentially the operationalization of variables. Future studies should take into consideration pre-existing tools such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (Felitti et al., 1998) to capture universally recognized childhood trauma factors that impact health.

Despite the obvious needs of human trafficking victims, there are numerous barriers that prohibit or impede providing comprehensive services. Some of these barriers to care include the illegal nature of trafficking, fear related to concerns of safety and security, distrust of authority, stigma and shame, cultural and language barriers, loyalty to or dependence on the exploiter, and the fact that many victims don’t identify themselves as victims of human trafficking (Chaffee & English, 2015). An additional limitation to providing comprehensive services to all trafficking survivors is that most research has focused on the sexual exploitation of women and children and has not fully explored the needs of victims of labor trafficking (Zhang, 2012). Considering these barriers to care and the importance of identifying victims quickly and accurately, it is imperative that providers are educated on trauma-informed care (Barnert et al., 2016; Bounds, Julian & Delaney, 2015; Chaffee & English, 2015; Cole & Sprang, 2015; Grace, Ahn, & Macias Konstantopoulos, 2014; Greenbaum & Crawford-Jakubiak, 2015; McNiel, Held, & Busch-Armendariz, 2014).

Trauma-informed care utilizes a strength-based approach that recognizes the resilience of victims while minimizing further harm or re-traumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Victims of human trafficking have extensive needs and many organizations are passionate about helping them; however, accomplishing this means that individuals and organizations must be sensitive to the needs and experiences of both the sex and labor trafficking victims they are working with. While trauma-informed care has become a staple of mental healthcare and working with patients in the justice department (Munro-Kramera, Becka, Choib, Singera, Gebharda, & Carrc, inpress), it is not currently part of legal training. Therefore, future work should explore training lawyers and all healthcare providers in trauma-informed care.

In our study, the human trafficking victims presented with a number of diverse needs to the human trafficking clinic. While, the majority of their social service and legal needs were met by the legal clinic, the needs with the lowest rates of resolution were related to healthcare. It is estimated that approximately 28–50% of trafficking victims come into contact with a healthcare provider during their exploitation and are not recognized (Baldwin, Eisenman, Sayles, Ryan, & Chuang, 2011; Family Violence Prevention Fund, 2005); however these estimates are limited by small sample sizes and a large focus on female sex trafficking victims. Alternatively, 63% of health care providers report they have never received training on how to identify and assist sex trafficking victims (Beck et al., 2015); this estimate is again limited by its focus sex trafficking. It is clear that human trafficking victims have extensive needs throughout their trafficking experience (pre, during, and post) that are often not being met due to a lack of healthcare provider identification and training. In order to serve this vulnerable population, there is a need for improved training among healthcare providers as well as collaboration between disciplines to assist with identification, response, and meeting the comprehensive needs of both sex and labor trafficking victims (Hemmings et al., 2016).

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered with the limitations in mind. This was a secondary analysis of pre-existing data and thus the research question was constrained by the data available within legal files. We took a conservative approach to determining whether or not exposures and outcomes were present among our sample and only analyzed data that were endorsed in clients’ clinical records. As such, it is possible that we under-estimated trauma or trafficking experience and services received. Additionally, this study has limited generalizability because it only evaluated victims who sought legal assistance, specifically at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic. This study did not include victims who did not have access to legal care, missing a potentially vulnerable and valuable population. Future work should consider the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of victims from a more diverse geographic location who do and do not access services. Despite these limitations, the strengths of this analysis include the large number of labor trafficking victims. Past research has been constrained by its focus exclusively on sex trafficking victims.

Future Directions

To more effectively meet the needs of human trafficking victims, healthcare providers, lawyers, law enforcement, and researchers need to work together to create screening tools to assist law enforcement, nursing, and primary care providers in identifying both sex and labor trafficking victims so that victims’ healthcare, social service, and legal needs can be effectively met. There is a lack of evidence-based, clinically feasible screening tools or processes for identifying victims of human trafficking in hospitals and health centers (Varma et al., 2015). It is essential that an interdisciplinary team of providers begin to work together to develop and evaluate these tools within diverse clinical settings. Human trafficking advocates and researchers can learn from pre-existing screening tools, policies, and procedures for intimate partner violence and sexual assault. For instance, the Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) model where clinicians, law enforcement, and advocates work together to identify the needs of sexual assault survivors in their local areas and develop policies and procedures appropriate for them (Lewis-O’Connor, 2009) could be a very useful model for future collaboration among disciplines serving human trafficking victims. Additional research is also warranted to understand the relationship between pre-existing health conditions, trauma, and the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of human trafficking victims.

Conclusion

By researching the needs of victims who received legal aid at the University of Michigan Human Trafficking Clinic, we are able to understand the characteristics of victims seeking legal services. This information provides additional details regarding the healthcare, social service, and legal needs of human trafficking victims that may be helpful in the future creation of comprehensive screening tools, interventions, and service delivery measures tailored to this population. Human trafficking affects all facets of a victim’s life; therefore, comprehensive care with effective communication between disciplines is necessary. Additional research is warranted to further understand the service needs of human trafficking victims, develop screening tools to identify service needs, and to increase interdisciplinary collaboration in identifying and meeting the needs of victims of human trafficking.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding and support from Katheryn Soller. The collaboration between the University of Michigan Law School and School of Nursing would not have been possible without her contributions and foresight. The authors would like to acknowledge the faculty and staff at the University of Michigan Law School Human Trafficking Clinic for their assistance in creating the database that led to this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Anna Schmeissing, Engineering Student at the University of Michigan for creating Figure 1. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Jody Lori for her contributions to this project.

Funding

This work was supported by Katheryn Soller.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

References

- Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, & Chuang KS (2011). Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health and Human Rights, 13(1), E36–E49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnert ES, Abrams S, Azzi VF, Ryan G, Brook R, & Chung PJ (2016). Identifying best practices for “Safe Harbor” legislation to protect child sex trafficking victims: Decriminalization alone is not sufficient. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck ME, Lineer MM, Melzer-Lange M, Simpson P, Nugent M, & Rabbitt A (2015). Medical providers’ understanding of sex trafficking and their experience with at-risk patients. Pediatrics, 135(4), e895–e902. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounds D, Julion WA, & Delaney KR (2015). Commercial sexual exploitation of children and state child welfare systems. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 16(1–2), 17–26. doi: 10.1177/1527154415583124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffee T, & English A (2015). Sex trafficking of adolescents and young adults in the United States: Healthcare provider’s role. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 27(5), 339–344. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2016, October 28). Definitions of child abuse and neglect. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/define.pdf

- Cole J, & Sprang G (2015). Sex trafficking of minors in metropolitan, micropolitan, and rural communities. Child Abuse and Neglect, 40, 113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Violence Prevention Fund. (2005, April 16). Turning pain into power: Trafficking survivors’ perspectives on early intervention strategies. San Francisco, CA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/ImmigrantWomen/Turning%20Pain%20intoPower.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fedina L (2015). Use and misuse of research in books on sex trafficking: Implications for interdisciplinary researchers, practitioners, and advocates. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 188–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838014523337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedina L, & DeForge B (2017). Estimating the trafficked population: Public-health research methodologies may be the answer. Journal of Human Trafficking, 3(1), 21–38. doi: 10.1080/23322705.2017.1280316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AM, Ahn R, & Macias Konstantopoulos W (2014). Integrating curricula on human trafficking into medical education and residency training. JAMA pediatrics, 168(9), 793–794. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum J, & Crawford-Jakubiak JE, & Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. (2015). Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Health care needs of victims. Pediatrics, 135(3), 566–574. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings S, Jakobowitz S, Abas M, Bick D, Howard LM, Stanley N, … Oram S (2016). Responding to the health needs of survivors of human trafficking: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 16:320. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1538-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. (2017, December 11). Forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang–en/index.htm

- Kiss L, Pocock NS, Naisanguansri V, Suos S, Dickson B, Thuy D, & Zimmerman C (2015b). Health of men, women, and children in post-trafficking services in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: An observational cross-sectional study. The Lancet Global Health, 3(3), e154–e161. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70016-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss L, Yun K, Pocock N, & Zimmerman C (2015a). Exploitation, violence, and suicide risk among child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion. JAMA pediatrics, 169(9), e152278. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-O’Connor A (2009). The evolution of SANE/SART – Are there differences? Journal of Forensic Nursing, 5(4), 220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2009.01057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LK, Seng JS, & Miller JM (2008). Use of the Optimality Index-United States in perinatal clinical research: A validation study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 53, 302–309. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiel M, Held T, & Busch-Armendariz N (2014). Creating an interdisciplinary medical home for survivors of human trafficking. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 124(3), 611–615. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Kramera M, Becka D, Choib K, Singera R, Gebharda A, & Carrc B (in press). Trauma-informed care in nursing: A scoping review of the state of the science.

- Oram S, Khondoker M, Abas M, Broadbent M, & Howard LM (2015). Characteristics of trafficked adults and children with severe mental illness: A historical cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00290-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram S, Stockl H, Busza J, Howard LM, & Zimmerman C (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: A systematic review. PLoS Medicine, 9(5), e1001224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottisova L, Hemmings S, Howard LM, Zimmerman C, & Oram S (2016). Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: An updated systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25, 317–341. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaris. (2014, December 11). A look back: Building a human trafficking legal framework. Retrieved from https://polarisproject.org/sites/default/files/2014-Look-Back.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4801. Rockville, MD: Author; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Moss E, Zimmerman C, Howard LM, & Oram S (2014). Labour exploitation and health: A case series of men and women seeking post-trafficking services. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16(3), 473–480. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9832-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2000, December 11). Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against transnational organized crime. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolTraffickingInPersons.aspx

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2004, November 6). United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the protocols thereto. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNTOC/Publications/TOC%20Convention/TOCebook-e.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2012, November 6). A comprehensive strategy to combat trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/UNODC_Strategy_on_Human_Trafficking_and_Migrant_Smuggling.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2015, November 6). Monitoring Target 16.2 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: A multiple systems estimation of the numbers of presumed human trafficking victims in the Netherlands in 2010–2015 by year, age, gender, form of exploitation and nationality. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/research/UNODC-DNR_research_brief_web.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2017, November 6). Global report on trafficking in persons. 2016. Retrieved from http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2016_Global_Report_on_Trafficking_in_Persons.pdf

- United States Department of State. (2016, July 20). Trafficking in persons report. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258877.pdf

- Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, & Greenbaum VJ (2015). Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44, 98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX (2012). Measuring labor trafficking: A research note. Crime, Law and Social Change, 58(4), 469–482. doi: 10.1007/s10611-012-9393-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman C, Hossain M, & Watts C (2011). Human trafficking and health: A conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Social Science & Medicine, 73(2), 327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]