Summary

Digital health data used in diagnostics, patient care, and oncology research continue to accumulate exponentially. Most medical information, and particularly radiology results, are stored in free-text format, and the potential of these data remains untapped. In this study, a radiological repomics-driven model incorporating medical token cognition (RadioLOGIC) is proposed to extract repomics (report omics) features from unstructured electronic health records and to assess human health and predict pathological outcome via transfer learning. The average accuracy and F1-weighted score for the extraction of repomics features using RadioLOGIC are 0.934 and 0.934, respectively, and 0.906 and 0.903 for the prediction of breast imaging-reporting and data system scores. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the prediction of pathological outcome without and with transfer learning are 0.912 and 0.945, respectively. RadioLOGIC outperforms cohort models in the capability to extract features and also reveals promise for checking clinical diagnoses directly from electronic health records.

Keywords: electronic health records, digital health data, repomics, radiology, breast cancer, artificial intelligence, decision support

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

RadioLOGIC is proposed for processing unstructured electronic health records (EHRs)

-

•

The term “repomics” is proposed for extracting valuable features from EHRs

-

•

RadioLOGIC can assess human health characteristics and predict pathological outcomes

Zhang et al. propose a large language healthcare model, called RadioLOGIC, for processing electronic health records and decision-making in breast disease. The model can automatically extract valuable features from unstructured electronic health records and evaluate human health characteristics and predict pathological outcomes of breast diseases through transfer learning.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and the leading cause of cancer mortality in women.1 In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI)-based breast cancer research has received increasing attention, particularly in the fields of radiology and pathology.2,3 As AI is, to some extent, data driven, leveraging digital health data with appropriate clinical characteristics is important.4,5 On one hand, they can be used as labels for downstream tasks; on the other hand, they may contain potential additional features useful for classification and can be used for co-learning to improve image-based learning.6,7,8,9 In recent years, some studies have shown that machine-learning techniques trained on features from electronic health records show considerable potential and effectiveness in accomplishing clinical tasks.10,11,12,13,14

Digital health data for various patient care and oncology research continue to accumulate exponentially; however, most medical information is stored in free-text format. Therefore, the data are inaccessible for computer analysis, and their potential remains unused.15 Manually extracting information/features is costly, time consuming, and burdensome for physicians. There is an urgent need for a technology to effectively assist researchers to accurately extract high-quality features from unstructured texts. It may also help to understand reports better and provide decision support for physicians. Natural language processing (NLP) has emerged as an AI technique for interpreting free text. Some studies have shown that NLP models can extract information and even make decisions from medical reports.16,17,18 However, most of the previous NLP models were based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with the application of bidirectional long short-term memory or integration of attention mechanisms.16,19 These methods may not learn the relationship of distant words well, making it difficult to parse longer text.20 In recent years, bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT)-based models have received increasing attention.21,22,23,24 However, BERT requires a large amount of data for pre-training, and the public and trained models cannot be applied to specific fields, such as medical-related tasks. In addition, the model performance for long and complex texts still needs to be improved.

In line with the current terminology for extraction of quantitative data out of unstructured data (e.g., radiomics, pathomics, etc.), we propose the term “repomics” (report omics) for extracting valuable features from electronic health records/reports, such as the health status of the patient and the relevant characteristics of the lesion. In this study, we develop radiological repomics-driven model incorporating medical token cognition (RadioLOGIC) to extract valuable features from unstructured radiological reports and assess breast imaging-reporting and data system (BI-RADS) scores and predict pathological outcomes directly based on the description from the unstructured electronic health records.

Results

Pre-training NLP model

First, the prediction accuracies of different pre-training methods are compared when randomly masking input words with a probability of 15% (Figures S1E and S1F). A bigger dataset plus incremental learning (BD + I) improved prediction accuracy for masked words, and recurrent learning (BD + I + R) even further improves the prediction performance, with an accuracy of 0.866 and a top 5 accuracy of 0.957, indicating that the pre-trained model can establish connections between words in radiological reports and understand contextual relationships. In addition, the accuracies under different random masking probabilities were also compared (Figure S1F). When the masking probability of the input word was 5%, the prediction accuracy decreased even if the number of times (n) of data recycling increased. In addition, the prediction accuracy also decreased when the masking probability was increased to 30% or 45%. Therefore, we selected the pre-trained model with a mask probability of 15% for subsequent experiments. See the STAR Methods for pre-training details.

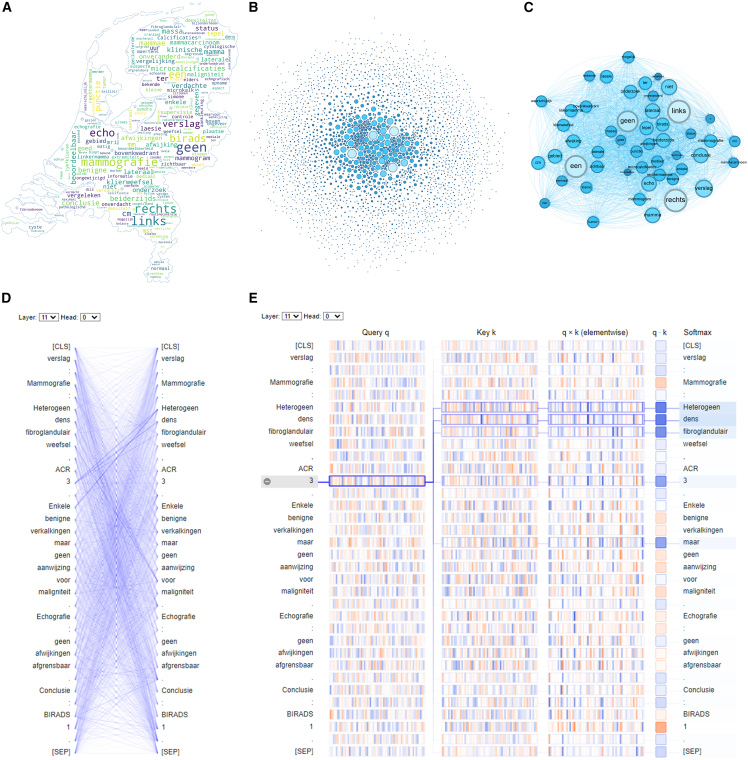

Visualization of pre-trained models

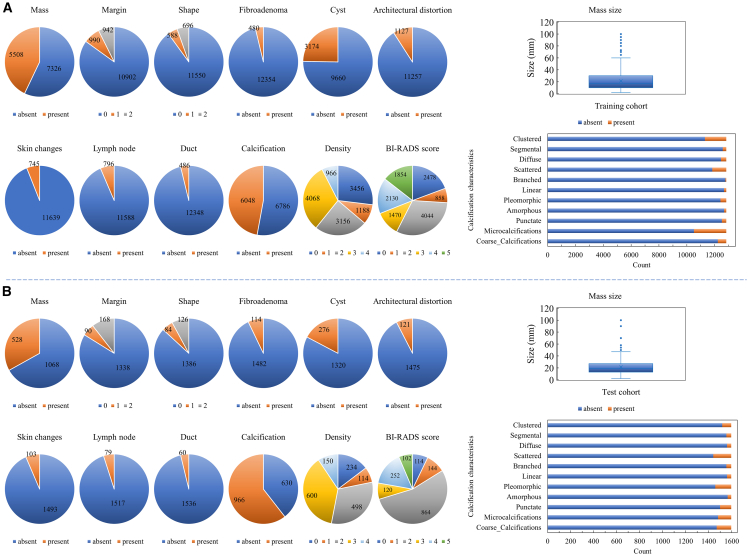

Figure 1 shows the feature details of the content of radiological reports for the training and test cohorts in this study. A word cloud (in the shape of a map of the Netherlands) based on all radiological reports is shown in Figure 2A and shows some words (in Dutch) that frequently appear in radiological reports. Figure 2B is a visualization of word co-occurrence (see Figure S2 for details) and shows word pairs that frequently co-occur in radiological reports. Figure 2C shows the association of top 50 co-occurrence words (see Table S2 for details).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of all radiological report content for the training cohort and the independent test cohort in this study

(A) Training cohort.

(B) Independent test cohort. A “0” means not applicable or missing. For margin: 1 for irregular, 2 for circumscribed. For shape: 1 for irregular, 2 for oval/round. Density category A (1): the breasts are almost entirely fatty. Density category B (2): there are scattered areas of fibroglandular density. Density category C (3): heterogeneously dense. Density category D (4): extremely dense. See also Table S1.

Figure 2.

Visualizations of words and sentence

(A) Word cloud based on all radiological reports.

(B) Visualization of word co-occurrence.

(C) Association of top 50 co-occurrence words.

(D) Associations between words in a given report after pre-training.

(E) The correlation between the selected word and other words in the report.

See also Figures S1–S3 and Table S2.

We visualized the pre-trained model to get an idea of how and what the model learned during the pre-training process. Figure 2D shows the specific dependencies between different words. The clearer the connection, the higher the weight and the higher the correlation between words (see Figure S3A for visualization of all layers/heads of the pre-trained model). Figure 2E is employed to rationalize visualizations and demonstrate correct correlation of inter-word relationships. For example, ACR 3 is the density of breast, representing heterogeneously dense breast tissue. As shown in Figure 2E, ACR “3” has the strongest correlation with “heterogeen” (heterogeneous in English), “dens” (dense in English), and “fibroglandulair” (fibroglandular in English), which indicates that the visualization is reasonable and that the pre-trained model learned the correct correlation between words. More examples of heatmaps are shown in Figures S3B and S3C.

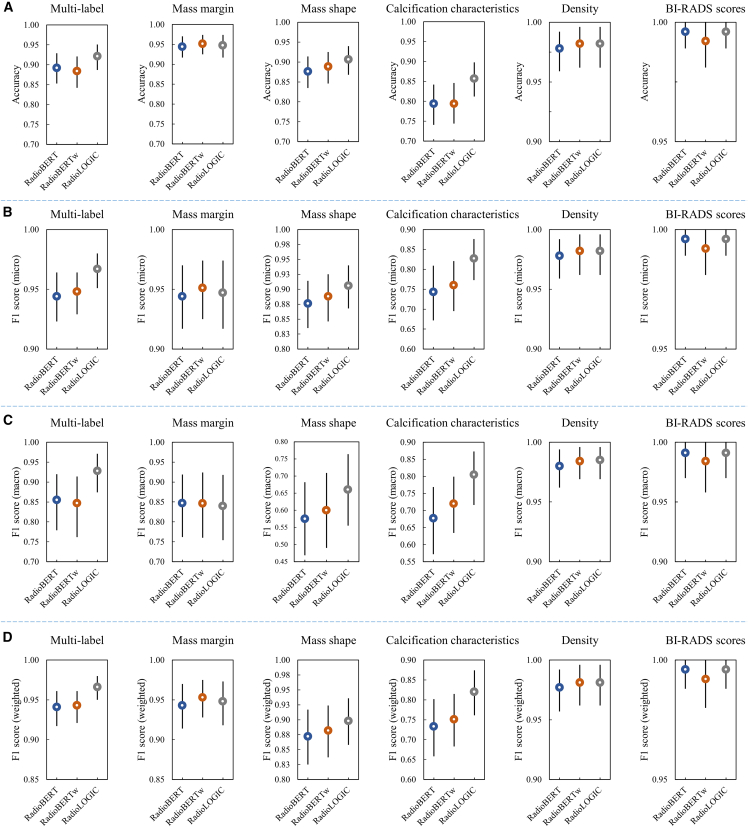

Imaging-feature extraction

The flowchart of repomics feature extraction is shown in Figure S4A. After fine-tuning, the model based on the original radiology BERT (RadioBERT) achieved an average accuracy of 0.913 [0.897, 0.928] for all tasks in the independent test set. The accuracy of the model based on the original RadioBERT with weighted loss (RadioBERTw) was improved to 0.915 [0.899, 0.930]. At the same time, to help the model understand the attributes of each word in the report during the classification process, we automatically labeled each token with attributes and predicted the attributes of each token based on the decoder (this is our final model: RadioLOGIC, Figure S4B). The schematic diagram of word attribute annotation and all attributes are shown in Figures S4C and S4D. As shown in Table 1, after combining medical token cognition, the performance of our model was significantly and substantially further improved, with an average accuracy of 0.934 [0.920, 0.948], an average F1-micro of 0.937 [0.922, 0.949], an average F1-macro of 0.868 [0.842, 0.892], and an average F1-weighted of 0.934 [0.919, 0.948] (RadioBERT/RadioBERTw vs. RadioLOGIC, all p values < 0.0001). Figure 3 shows the metrics details for extracting repomics features. We also compared it with traditional CNN- and RNN-based NLP models, as shown in Table 1, and the results show that our model substantially outperforms CNN- and RNN-based models (CNN/RNN vs. RadioLOGIC, all p values < 0.0001; see Figure S5 for metrics details). In addition, we tagged topic, laterality, and mass size during the labeling process of medical token attribute, enabling RadioLOGIC to complete the extraction of topic (mammography/ultrasound/MRI), laterality (left/right), and mass size (maximum diameter, mm) through named entity recognition. The results show that RadioLOGIC can accomplish this task well, with an accuracy of 0.996 [0.987, 1.000] in the test cohort.

Table 1.

Average results of the different classification tasks on the independent test set

| Accuracy | F1 score-micro | F1 score-macro | F1 score-weighted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-ATT | 0.797 (0.771, 0.820) | 0.772 (0.743, 0.800) | 0.623 (0.585, 0.664) | 0.758 (0.728, 0.786) |

| RNN-ATT | 0.841 (0.820, 0.862) | 0.823 (0.795, 0.848) | 0.662 (0.623, 0.704) | 0.802 (0.773, 0.830) |

| RadioBERT | 0.913 (0.897, 0.928) | 0.914 ([0.897, 0.929) | 0.821 (0.787, 0.851) | 0.910 (0.893, 0.927) |

| RadioBERTw | 0.915 (0.899, 0.930) | 0.920 (0.904, 0.935) | 0.830 (0.799, 0.862) | 0.917 (0.900, 0.933) |

| RadioLOGIC | 0.934 (0.920, 0.948) | 0.937 (0.922, 0.949) | 0.868 (0.842, 0.892) | 0.934 (0.919, 0.948) |

Note: values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. CNN, convolutional neural network; RNN, recurrent neural network; ATT, attention mechanism; BERT, bidirectional encoder representations from transformers; RadioBERT, original radiology BERT; RadioBERTw, original RadioBERT with weighted loss; RadioLOGIC, radiological repomics-driven model incorporating medical token cognition.

Figure 3.

Metrics details for extracting repomics features in the independent test cohort

(A) Accuracy.

(B) Micro F1 score.

(C) Macro F1 score.

(D) Weighted F1 score. The black vertical lines in the graph represent 95% confidence intervals.

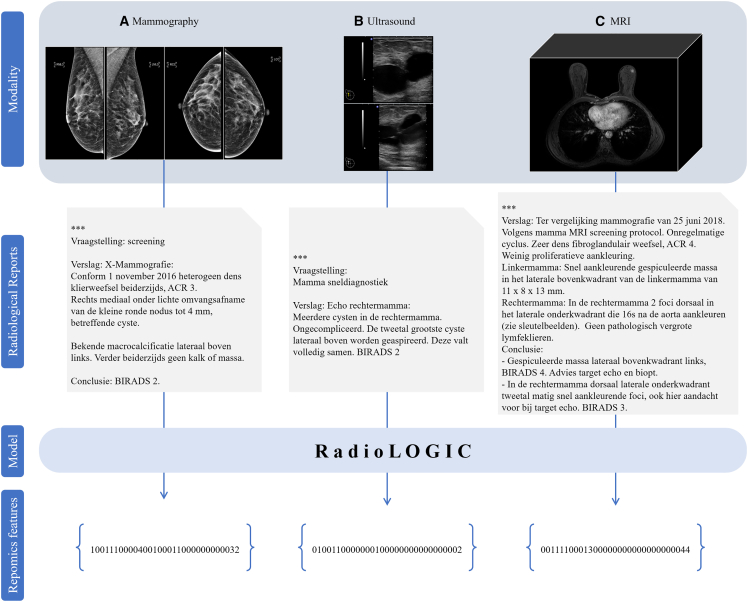

Figure 4 shows some examples of repomics feature extraction from corresponding radiology images and radiological reports using RadioLOGIC (the meaning of repomics feature codes is shown in Figure S6). A visualization example of repomics feature extraction is shown in Figure S7. Based on the visualization process, we can intuitively see the focus of RadioLOGIC in extracting repomics features.

Figure 4.

Examples of repomics feature extraction from corresponding images and radiological reports

(A) Mammography.

(B) Ultrasound.

(C) MRI. “∗∗∗” in the radiological report indicates the patient’s private information.

See also Figures S4–S7.

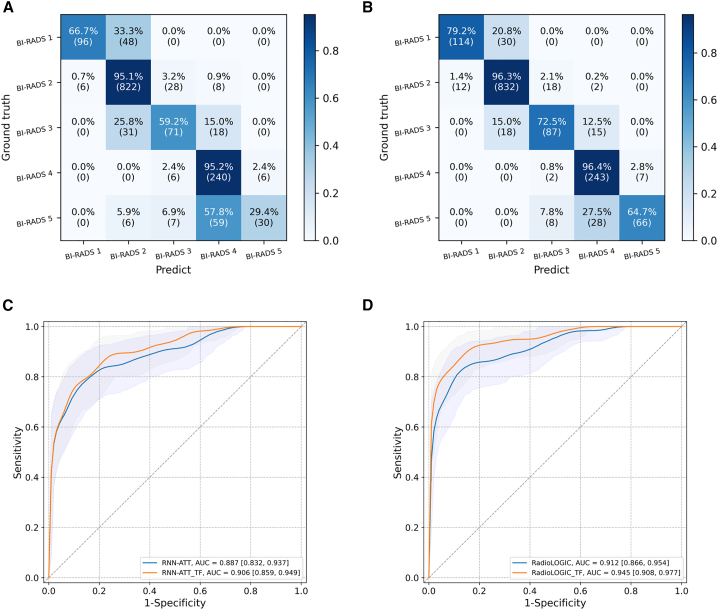

Downstream tasks: BI-RADS score prediction

In this task, we masked the existing BI-RADS score in the report and used it as the prediction label, and then RadioLOGIC was used to predict the BI-RADS score. Figures 5A and 5B show the confusion matrix for predicting BI-RADS scores in an independent test cohort of 1,482 imaging reports. Our model could predict BI-RADS scores with an accuracy of up to 0.850 [0.832, 0.869] and an F1-weighted score of 0.838 [0.817, 0.859]. The performance of the model was boosted by transfer learning with an accuracy of 0.906 [0.890, 0.921] (p < 0.0001) and an F1-weighted score of 0.903 [0.887, 0.919] (p < 0.0001). See Table 2 for the metrics details of the different models, which show that RadioLOGIC outperforms RNN-based models on this task.

Figure 5.

Prediction results for downstream tasks

(A) Confusion matrix results for predicting BI-RADS scores in the independent test cohort using RadioLOGIC without transfer learning.

(B) Confusion matrix results for predicting BI-RADS scores in the independent test cohort using RadioLOGIC via transfer learning.

(C) Receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting pathological outcome in the independent test cohort using RNN.

(D) Receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting pathological outcome in the independent test cohort using RadioLOGIC. The 95% confidence intervals are shown as a shaded area for the ROC curve.

ATT, attention mechanism; BI-RADS, breast imaging-reporting and data system; RadioLOGIC, radiological repomics-driven model incorporating medical token cognition; RNN, recurrent neural networks; TF, transfer learning.

See also Table S3.

Table 2.

Metrics details of the different models for predicting BI-RADS scores

| Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score (weighted) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNN-ATT | 0.823 (0.802, 0.843) | 0.741 (0.703, 0.781) | 0.656 (0.625, 0.686) | 0.811 (0.790, 0.833) |

| RNN-ATT_TF | 0.836 (0.744, 0.816) | 0.780 (0.744, 0.816) | 0.678 (0.649, 0.709) | 0.825 (0.805, 0.847) |

| RadioLOGIC | 0.850 (0.832, 0.869) | 0.811 (0.778, 0.844) | 0.692 (0.662, 0.722) | 0.838 (0.817, 0.859) |

| RadioLOGIC_TF | 0.906 (0.890, 0.921) | 0.871 (0.846, 0.896) | 0.819 (0.791, 0.846) | 0.903 (0.887, 0.919) |

Note: values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. BI-RADS, breast imaging-reporting and data system; TF, transfer learning; RNN, recurrent neural network; ATT, attention mechanism; RadioLOGIC, radiological repomics-driven model incorporating medical token cognition.

Downstream tasks: Pathological outcome prediction

As shown in Figures 5C and 5D, our model RadioLOGIC could predict pathological outcome directly from unstructured radiological reports with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.912 [0.866, 0.954], outperforming currently widely used NLP models combining RNN and attention mechanism (RNN-ATT; 0.887 [0.832, 0.937]) (RNN-ATT vs. RadioLOGIC, p < 0.0001). In addition, the AUC based upon BI-RADS scores is only 0.865 [0.803, 0.918] (RadioLOGIC vs. BI-RADS scores, p < 0.0001), which is lower than RadioLOGIC, which indicates that the report contains more information than what is summarized in the BI-RADS score.

In addition, the prediction performance was further improved by making the model first predict imaging features and then predict pathological outcome through transfer learning (TF), and the AUC of our RadioLOGIC was improved to 0.945 [0.908, 0.977] (RadioLOGIC vs. RadioLOGIC_TF, p < 0.0001). The RadioLOGIC with transfer learning achieved an accuracy of 0.926 [0.888, 0.959], a sensitivity of 0.739 [0.618, 0.852], a specificity of 0.984 [0.962, 1.000], a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.934 [0.852, 1.000], and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.924 [0.885, 0.959], outperforming the RadioLOGIC without transfer learning, which has an accuracy of 0.896 [0.855, 0.934], a sensitivity of 0.666 [0.536, 0.785], a specificity of 0.967 [0.941, 0.990], a PPV of 0.864 [0.750, 0.957], and an NPV of 0.903 [0.859, 0.944] (all p values < 0.0001). The metrics details are shown in Table S3.

Discussion

In this study, we report an NLP technique for processing unstructured radiological reports. Our main contributions and findings can be summarized as follows: (1) we perform pre-training using million-level medical-related samples, allowing the model to address domain-specific problems. (2) We automatically extract patient characteristics from unstructured electronic health record descriptions. (3) We invented medical token attribute cognition to improve our model prediction accuracy. (4) We developed an end-to-end technology model to assess human health characteristics (in this use case, the BI-RADS score) directly based on the description from the radiological reports and predict the pathological outcome of breast lesions via transfer learning.

Existing electronic medical reports/records contain a wealth of special and useful features that can potentially be used as input data for downstream tasks.12,13 In recent years, research on electronic health records has become a hot topic. Some studies have attempted to utilize electronic health records/reports to assess human health using machine-learning models and sequence likelihood defect models.12,13 However, the performance of these models may be limited because they are not suitable for directly dealing with NLP problems, which weakens their potential future application value. Bustos et al. explored the performance of CNN- and RNN-based NLP models for information extraction from medical reports and combined the attention mechanism to improve the performance of the model.16 Further studies have attempted to apply NLP techniques to breast-related research.25,26 Tang et al. applied machine-learning-based NLP to parse pathology reports (n = 2,104).26 However, they only detected the presence of certain keywords, and their results were based on relatively structured pathology reports and traditional machine learning, which cannot guarantee the performance of the model on unstructured and complex datasets. In addition, these algorithms based on traditional machine learning, CNN, or RNN still need improvement, especially for long and complex texts.

In the breast health domain, radiologists describe breast images (e.g., mammography, ultrasound, and MRI) based on the BI-RADS lexicon to generate radiological reports. However, radiological reports are unstructured and complex due to the diversity of descriptions of breast patients by different radiologists. In this study, we proposed the term repomics for extracting valuable features from digital health reports and developed RadioLOGIC to automatically extract repomics features from unstructured reports. Traditional space-based and letter-based tokenization methods result in either special symbolic tokens like <UNK> or non-meaningful tokens. The applied byte-level byte pair encoding tokenizer in our study was trained on the Dutch text dataset to improve the efficiency and utility of the model for tokenization. Compared with the statically generated word vectors of Word2Vec, this method dynamically generates word vectors according to the context based on the masked language modeling, and then incremental learning and recurrent learning are combined to strengthen the pre-training effect. In addition, traditional Word2Vec-based methods require complex pre-processing, including stemming, lemmatization, removal of stop words, etc., while our method does not require complex pre-processing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest dataset for radiology-related research on breast, with over 0.62 million general medical reports and about 0.29 million radiological reports. The results of pre-training show that larger data can allow our model to better understand the structure and meaning of radiological report content, and the incremental learning from medical texts to radiological reports together with the recurrent learning for radiological reports enables the model to effectively learn the relationships within the context of the reports, proving the superiority of the pre-training approach. It is worth noting in this study that the maximum length of radiological reports was 447 words and the average length was 94, while the average length of medical reports in previous studies was relatively short. For example, the mean number of tokens per report for the study of Bustos et al. was less than 7, which shows that the report content was relatively simple.16

The results show that our RadioLOGIC outperforms CNN- and RNN-based NLP models in the task of extracting repomics features, indicating that our model performs better for complex long-text datasets. In particular, RadioLOGIC incorporates the medical token attribute cognition co-learning task to predict the attribute for each word in the report, which improves the performance of the model. In addition to repomics feature extraction, our model can predict BI-RADS scores based on descriptions from unstructured reports, and the application of transfer learning further improves the model’s performance in predicting BI-RADS scores, which could serve as decision support for clinicians. Importantly, RadioLOGIC was shown to directly predict pathological outcomes from radiological reports via transfer learning, which showed correlations between the text-derived repomics and pathological outcomes, potentially providing radiology-pathology concordance. This may assist clinicians in decision-making, potentially increasing efficiency and reducing the burden on pathologists. In addition, our model could potentially evaluate and make decisions from the patient’s longitudinal temporal electronic health records, thereby enabling effective patient monitoring and providing immediate feedback when the patient’s status changes due to newly reported information. Ultimately this may lead to better patient care.

In conclusion, RadioLOGIC shows promise for extracting repomics from electronic health records and outperforms existing methods. In addition, RadioLOGIC can potentially predict BI-RADS scores and pathological outcome directly from radiological reports to provide decision support for clinicians, which also reveals its promise to enhance clinical decision-making directly from electronic health records, thereby benefiting patient care.

Limitations of the study

This study has some limitations. First, this is a single-center study, and the model could potentially be susceptible to single-center bias. Further research is needed to collect electronic health records from other hospitals to update the model and verify the robustness of the model. Second, for BI-RADS scores, differences in assessments due to differences in experience and inherent thresholds among clinicians could lead to reader variance, which could potentially weaken the performance of the model in this regard. Further evaluation of the extent of RadioLOGIC error is needed, i.e., errors are more forgivable on variable scoring cases than on highly expert-agreed scoring cases, and the model can be further improved accordingly. Third, our study introduced repomics as an extraction of valuable features from unstructured electronic health records and adopted the use case of automated analysis of breast disease-related radiological reports. Further series of studies are needed to demonstrate the generalizability of the model for different types and diseases of electronic health records. Fourth, the target language of the model during training was only Dutch. Our goal is to build a multilingual NLP model to process unstructured radiological reports in various languages to deal with radiology-related problems. Fusion of multilingual electronic health records is required to enhance the proposed model. Interested parties can contribute by adding multiple languages to RadioLOGIC based on our method.

Furthermore, the model was used in downstream tasks to assess human health characteristics (in this use case, BI-RADS scores) directly from descriptions in unstructured radiological reports and to predict the pathological outcome of lesions through transfer learning. Further research on the prediction of cancer subtypes based on repomics features may help to provide radiology-pathology concordance in a more precise and detailed manner through the visualization of repomics features. Finally, prospective studies before the model is applied in reality are needed to further verify its ability to assist or even improve clinician decision-making in real-world scenarios.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| Source code | This paper | https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP |

| Supplementary Figures and Tables | This paper | https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP |

| Token data files | This paper | https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Gephi | The Open Graph Viz Platform | https://gephi.org/ |

| pytorch 1.11.0 | PyTorch | https://pytorch.org/ |

| huggingface-hub 0.5.1 | Hugging Face | https://huggingface.co/ |

| tokenizers 0.12.1 | Hugging Face | https://huggingface.co/docs/tokenizers/index |

| transformers | Hugging Face | https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/index |

| numpy 1.21.5 | NumPy | https://numpy.org/ |

| pandas 1.3.5 | pandas | https://pandas.pydata.org/ |

| scikit-learn 1.0.2 | scikit-learn | https://scikit-learn.org/stable/ |

| Other | ||

| Website for this study | This paper | https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Tao Tan (taotanjs@gmail.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Data collection

We collected 621,072 medical records, including radiological reports (mammography, ultrasound and MRI), pathological reports and patient records, from 37,517 patients in Netherlands Cancer Institute between January 2000 and December 2020. The total size of the medical-related corpus is 63,020,838 words. All texts were recorded in Dutch, radiological reports were created using typical medical jargon. All privacy-related content was removed, such as patient names, identification codes, etc. A total of 291,502 reports, with a minimum of 14 words, a maximum of 447 words, and an average of 94 words per report. Cases with BI-RADS 0 and 6 were excluded during training because 0 represented incomplete information and 6 represented known malignant breast tumors. A fraction of the radiological reports for training and test sets were annotated by researchers and verified by dedicated breast radiologists. Initially, a total of 14,260 cases were annotated, followed by a purely random split of 9:1 to obtain a training set and an independent test set, resulting in a training set of 12,834 cases and an independent test set of 1,426 cases. Subsequently, 170 annotated new cases were obtained and added to the independent test set, resulting in a final independent test set of 1596 cases. Figure 1 show feature details of electronic health record content of the training and test cohorts in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institute with a waiver of informed consent (registration number: IRBd21–058).

Method details

NLP model

RadioLogical repOmics driven model incorporatinG medIcal token Cognition (RadioLOGIC) was developed based on BERT to understand unstructured radiological reports, to extract imaging features from the reports/repomics features and to generate clinical diagnosis. First, all the words in reports were mapped to corresponding tokens, then passed through the embedding layer, and finally the embedded words were used as the input of the transformer encoder layers to be iteratively processed layer by layer. After that, the decoder layer was used to predict the attributes of each input token. We employed L=12 layers of transformers block with a hidden size of H=768 and number of parallel self-attention heads of h=12. Self-attention was divided into three branches, called query (Q), key (K) and value (V), and then the Q and each K were calculated through the scaled dot-product to obtain the weights.27 The softmax function was used to normalize these weights. Finally, the weights and V were weighted and summed to obtain refined features. The formula for Multi-Head Self-Attention is as follows:

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

where , , and represent the weight matrices of Q, K, V and concatenated multi-heads, respectively.

To be able to process Dutch language reports, we applied masked language modeling to enable our proposed model to understand Dutch radiological reports. Figures S1A and S1B show the basic framework for pre-training our NLP model. For comparison, datasets of different sizes and types were used for pre-training. First, we pre-trained our NLP model with small (25%) and large (100%) datasets of radiological reports, respectively. To enable the NLP model to better learn and understand medically relevant language, radiological reports, pathology reports and patient records were included to expand the body of pre-training data. Figure S1C shows the process of incremental learning, the model is first pre-trained based on all the collected breast medicine-related corpora, and then the model focuses on the main domain corpus of radiological reports for intensive continuous pre-training learning, and finally the model was fine-tuned with downstream tasks. Figure S1D shows the process of predicting masked words in unsupervised pre-training. The pre-training process goes through 10 epochs. In this process, through unsupervised learning, we randomly masked certain positions in the input sequence with a probability of 5%, 15%, 30% and 45%, and then predicted them through the model used for pre-training. RadioLOGIC was first pre-trained based on all collected medical reports/records, and then focused on radiological reports for intensive continuous pre-training learning. To take full advantage of random masking, we recycle the domain corpus n times to predict as many different words as possible to fully learn the relationship between words, we call it recurrent learning. The formula for n is as follows:

| (Equation 3) |

where pro[mask] represents the probability that the word is masked.

Training details

For the unsupervised pre-training process, the batch was set to 32 for 10 epochs and the learning rate was 1e-4, AdamW optimizer was applied to update the model parameters. For the feature extraction process and downstream tasks, the batch was set to 32 for 500 epochs, the initial learning rate was 1e-3 with a decay factor of 0.75 every 20 epochs, Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer was applied to update the model parameters. Models were built with PyTorch (torch version 1.11.0) and Python 3.8. All models were trained on NVIDIA RTX A6000 graphics processing unit (GPU), with 48 Gigabytes of GPU memory.

Token annotation and tokenizer

According to the BI-RADS lexicon, each token in the radiological report was automatically assigned special attributes. Attributes were assigned according to the relevant information based on the “BIO” encoding.28 “B” is “Begin”, which refers to the special attribute token that appears for the first time in the text, and “I” is “Intermediate”, which refers to the subsequent tokens of the same attribute, and “O” is “Others”, which refers to other tokens without special attributes.

In our study, Byte level BPE tokenizer was adapted as tokenizer for word segmentation.29 This was done by first encoding the text in UTF-8, using up to 4 bytes per character, and then turning the text into a sequence of UTF-8 bytes. For a given byte sequence , the maximum number of characters that can be recover from is denoted as , the is defined as follows:

| (Equation 4) |

Visualization

We implemented model visualization based on the work of Vig.30 The attention patterns produced by one or more attention heads in a given layer were visualized based on attention-head view. In the attention-head view, self-attention was represented as lines connecting each token on the left with each token on the right, and the line width reflects the attention score. Meanwhile, a birds-eye view of attention of all layers and heads for a specific input was provided, where each layer/head was visualized as a thumbnail, conveying the rough shape of the attention pattern. In addition, individual neurons in the query and key vectors were visualized to show how they interact to produce attention. Scaled dot product attention was used in the Transformer encoder, and the attention distribution at position i in the sequence x is defined as follows:

| (Equation 5) |

where represents the query vector at position i, represents the key vector at position j, and d represents the dimension of k and q, and i = j equals the length of report x.

Visualization of word co-occurrence

Gephi was used for the visualization of word co-occurrences in radiological reports.31 The ForceAtlas2 algorithm was used to plot the network, showing words as nodes, correlations as connecting edges between words, and strength of correlation by the weight of the edge.32

Imaging-feature extraction

After unsupervised pre-training, the model has learned the interactions between words in all reports in the medical context of breast disease. The realization of extraction is in two forms, including binary classification and multi-classification, where all binary classification tasks are treated as a multi-label task. The main collected and annotated characteristics are shown in Table S1.

Downstream tasks-BI-RADS score prediction

The BIRADS scoring standard is widely used in various breast imaging examinations, including mammography, ultrasound, MRI, etc., to describe the likelihood of malignancy in breast images. The BIRADS score is, consequently, very critical for determining recalls and indicating biopsies. Despite their importance, there is observed reader variance in the given BIRADS scores.33 Therefore, we provide decision support using our RadioLOGIC model to predict BIRADS score directly from the descriptions in the radiological reports through transfer learning. Cases with missing BIRADS scores were excluded, resulting in a total of 10,356 cases for the training cohort and 1482 cases for the independent test cohort in this task.

Downstream tasks-pathological outcome prediction

Repomics features were used to predict pathological outcome (normal/benign vs. malignant) to explore the intrinsic relationship between radiology features and pathological outcome and provide decision support for clinicians. Here, BIRADS 1 and 2 were considered benign/normal cases. Cases with BIRADS 3, 4, and 5 were labeled benign or malignant based on biopsy results, and cases without biopsy results were excluded from this task, resulting in a total of 10,025 cases (7338 cases normal/benign, 2687 cases malignant) for the training cohort and 1464 cases (1166 cases normal/benign, 298 cases malignant) for the independent test cohort in this task.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 27.0) and Python 3.9. Accuracy and F1 scores were used as evaluation indicators for the extraction of repomics features and in the BI-RADS prediction task. Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were used as figures of merit for the pathological outcome prediction task. 95% confidence intervals were generated with bootstrap method with 1000 replications.34 T-test was used to compare the difference of indicators among different methods. A two-side p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculation methods are as follows:

Where n represents the number of categories, represents the weight of the -th category.

Where TP is true positive, TN is true negative, FP is false positive and FN is false negative.

Where M, N are the number of positive samples and negative samples respectively. is the serial number of sample i. means add up the serial numbers of the positive samples.

Additional resources

Website for this study: https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the support from the Guangzhou Elite Project (TZ–JY201948). X.W., Y.G., and L.H. were funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (202107720016, 202006930001, and 202006240065). H.M.H. is an advisor to Roche and SlideScore.com. R.G.H.B.-T. is president of the European Society of Radiology (ESR) and a member of the EU mission board. R.M.M. is a member of the executive board of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI), chairperson of its scientific committee, and scientific advisor to ScreenPoint Medical and Siemens Healthcare.

Author contributions

R.M.M., T.T., and T.Z. designed the project; T.Z., X.W., Y.G., and L.H. performed the acquisition of data; T.Z., X.W., Y.G., L.H., L.B., A.D., H.M.H., and R.M.M. analyzed the data; T.Z. and T.T. proposed the model; J.T. contributed to device support for model training and inference; R.M.M. and R.G.H.B.-T. provided project administration and resources; T.Z. drafted the paper, and T.T. and R.M.M. revised it.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 24, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101131.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The original data is private and is not publicly available to guarantee protection of patients’ privacy. Excel file containing source data included in the main figures and tables can be found in the Source Data File in the article. We further provided source code for this study to facilitate reproducibility. The source code is available on github (https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP). It should only be used for non-commercial and academic research. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the Lead Contact upon request.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sechopoulos I., Teuwen J., Mann R. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in mammography and digital breast tomosynthesis: State of the art. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;72:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue P., Wang J., Qin D., Yan H., Qu Y., Seery S., Jiang Y., Qiao Y. Deep learning in image-based breast and cervical cancer detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022;5:19. doi: 10.1038/s41746-022-00559-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He J., Baxter S.L., Xu J., Xu J., Zhou X., Zhang K. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat. Med. 2019;25:30–36. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abul-Husn N.S., Kenny E.E. Personalized medicine and the power of electronic health records. Cell. 2019;177:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spasov S., Passamonti L., Duggento A., Liò P., Toschi N., Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative A parameter-efficient deep learning approach to predict conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2019;189:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng X., Yao Z., Huang Y., Yu Y., Wang Y., Liu Y., Mao R., Li F., Xiao Y., Wang Y., et al. Deep learning radiomics can predict axillary lymph node status in early-stage breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1236. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma M., Liu R., Wen C., Xu W., Xu Z., Wang S., Wu J., Pan D., Zheng B., Qin G., Chen W. Predicting the molecular subtype of breast cancer and identifying interpretable imaging features using machine learning algorithms. Eur. Radiol. 2022;32:1652–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald R.C., Antoniou A.C., Fruk L., Rosenfeld N. The future of early cancer detection. Nat. Med. 2022;28:666–677. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye C., Fu T., Hao S., Zhang Y., Wang O., Jin B., Xia M., Liu M., Zhou X., Wu Q., et al. Prediction of incident hypertension within the next year: prospective study using statewide electronic health records and machine learning. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20:e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Z., Du L., Zhang P., Zhao R., Chen X., Fang Z. Early sepsis prediction using ensemble learning with deep features and artificial features extracted from clinical electronic health records. Crit. Care Med. 2020;48:e1337–e1342. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garriga R., Mas J., Abraha S., Nolan J., Harrison O., Tadros G., Matic A. Machine learning model to predict mental health crises from electronic health records. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01811-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onishchenko D., Marlowe R.J., Ngufor C.G., Faust L.J., Limper A.H., Hunninghake G.M., Martinez F.J., Chattopadhyay I. Screening for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis using comorbidity signatures in electronic health records. Nat. Med. 2022;28:2107–2116. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niesen M.J.M., Pawlowski C., O’Horo J.C., Challener D.W., Silvert E., Donadio G., Lenehan P.J., Virk A., Swift M.D., Speicher L.L., et al. Surveillance of Safety of 3 Doses of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination Using Electronic Health Records. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5:e227038. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorin V., Barash Y., Konen E., Klang E. Deep-learning natural language processing for oncological applications. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1553–1556. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30615-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bustos A., Pertusa A., Salinas J.-M., de la Iglesia-Vayá M. Padchest: A large chest x-ray image dataset with multi-label annotated reports. Med. Image Anal. 2020;66:101797. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorin V., Barash Y., Konen E., Klang E. Deep learning for natural language processing in radiology—fundamentals and a systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2020;17:639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmy L., Nigo M., Kannadath B.S., Xie Z., Mao B., Patel K., Zhou Y., Zhang W., Ross A., Xu H., Zhi D. Recurrent neural network models (CovRNN) for predicting outcomes of patients with COVID-19 on admission to hospital: model development and validation using electronic health record data. Lancet. Digit. Health. 2022;4:e415–e425. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galassi A., Lippi M., Torroni P. Attention in natural language processing. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021;32:4291–4308. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3019893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu X., Liu W., Xu Y., Cui L. Combine HowNet lexicon to train phrase recursive autoencoder for sentence-level sentiment analysis. Neurocomputing. 2017;241:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devlin J., Chang M.-W., Lee K., Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv. 2018 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y., Ott M., Goyal N., Du J., Joshi M., Chen D., Levy O., Lewis M., Zettlemoyer L., Stoyanov V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv. 2019 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1907.11692. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferruz N., Höcker B. Controllable protein design with language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y., Guo Z., Xia B., Zhang Y., Liu X., Yu Y., Tang N., Tong X., Wang M., Ye X., et al. Identification of antimicrobial peptides from the human gut microbiome using deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022;40:921–931. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes K.S., Zhou J., Bao Y., Singh P., Wang J., Yin K. Natural language processing to facilitate breast cancer research and management. Breast J. 2020;26:92–99. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang R., Ouyang L., Li C., He Y., Griffin M., Taghian A., Smith B., Yala A., Barzilay R., Hughes K. Machine learning to parse breast pathology reports in Chinese. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018;169:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaswani A., Shazeer N., Parmar N., Uszkoreit J., Jones L., Gomez A.N., Kaiser Ł., Polosukhin I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017;30 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratinov L., Roth D. 2009. Design challenges and misconceptions in named entity recognition; pp. 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C., Cho K., Gu J. Vol. 34. 2020. Neural Machine Translation with Byte-Level Subwords; pp. 9154–9160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vig J. A multiscale visualization of attention in the transformer model. arXiv. 2019 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1906.05714. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastian M., Heymann S., Jacomy M. Vol. 3. 2009. pp. 361–362. (Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacomy M., Venturini T., Heymann S., Bastian M. ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian X., Pei J., Zheng H., Xie X., Yan L., Zhang H., Han C., Gao X., Zhang H., Zheng W., et al. Prospective assessment of breast cancer risk from multimodal multiview ultrasound images via clinically applicable deep learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021;5:522–532. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Efron B., Tibshirani R.J. CRC press; 1994. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original data is private and is not publicly available to guarantee protection of patients’ privacy. Excel file containing source data included in the main figures and tables can be found in the Source Data File in the article. We further provided source code for this study to facilitate reproducibility. The source code is available on github (https://github.com/Netherlands-Cancer-Institute/RadioLOGIC_NLP). It should only be used for non-commercial and academic research. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the Lead Contact upon request.