Summary

Autologous anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR T) therapy is highly effective in relapsed/refractory large B cell lymphoma (rrLBCL) but is associated with toxicities that delay recovery. While the biological mechanisms of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity have been investigated, the pathophysiology is poorly understood for prolonged cytopenia, defined as grade ≥3 cytopenia lasting beyond 30 days after CAR T infusion. We performed single-cell RNA sequencing of bone marrow samples from healthy donors and rrLBCL patients with or without prolonged cytopenia and identified significantly increased frequencies of clonally expanded CX3CR1hi cytotoxic T cells, expressing high interferon (IFN)-γ and cytokine signaling gene sets, associated with prolonged cytopenia. In line with this, we found that hematopoietic stem cells from these patients expressed IFN-γ response signatures. IFN-γ deregulates hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation and can be targeted with thrombopoietin agonists or IFN-γ-neutralizing antibodies, highlighting a potential mechanism-based approach for the treatment of CAR T-associated prolonged cytopenia.

Keywords: CAR T cell, B cell lymphoma, cytopenia, interferon

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

PC is associated with inferior outcomes following CAR T cell therapy

-

•

Clonally expanded CX3CR1hi cytotoxic T cells in bone marrow of patients with PC

-

•

CX3CR1hi cytotoxic T cells express high IFN-γ

-

•

HSCs from CAR T patients with PC bear signatures of IFN-γ response

Strati, Li, Deng et al. identify clonally expanded CX3CR1hi cytotoxic T cells expressing IFN-γ within the bone marrow of large B cell lymphoma patients with prolonged cytopenias following CD19 CAR T cell therapy, implicating chronic IFN-driven HSC dysfunction as a targetable mechanism of CAR T cell-associated prolonged cytopenia.

Introduction

Autologous anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR T) therapy has significantly improved the outcomes for patients with relapsed/refractory large B cell lymphomas (rrLBCL),1,2,3,4,5,6,7 but it is associated with toxicities that are a clinical challenge and delay patient recovery. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune-effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) occur within days to weeks following CAR T infusion with a clearly defined pathophysiology.8,9 However, longer-term toxicities also exist. Prolonged cytopenia (PC), defined as grade ≥3 cytopenia lasting beyond 30 days after CAR T infusion,10 occurs in ∼30% of patients and has an unclear etiology.2,3,4 Its rate and duration exceed what is observed with the use of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide,11 suggesting that it is not limited to conditioning therapy-induced myelosuppression. It can persist for several months to years, with significant clinical implications, including need for frequent transfusions, hospitalizations for infections, and limiting subsequent treatment options if there is disease progression.12,13,14,15,16 Identifying the mechanisms underlying PC and uncovering targeted therapeutic strategies is therefore a priority for improving patient outcomes.

Results

Prolonged cytopenia is associated with inferior outcomes following standard-of-care CD19 CAR T cell therapy

We performed a retrospective analysis of 223 rrLBCL patients treated with standard-of-care axicabtagene ciloleucel CD19 CAR T at our center between 01/2018 and 01/2021 who had available complete blood count on day 30 post infusion prior to any subsequent line of therapy. Of these, 169 did not have baseline grade 3–4 cytopenia, and 89/169 (53%) had CAR T-associated PC. PC was represented by grade 3–4 neutropenia in 49 (29%) patients, grade 3–4 anemia in 11 (7%), and grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia in 73 (43%). Within a subset of cases with available data from pre-treatment peripheral blood sequencing,17 clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential was found to be slightly more frequent in patients with PC (15/30, 50%) compared to those without (7/24, 29%), but this did not reach statistical significance (Fisher p = 0.166; Figure S1A). On univariate analysis, baseline characteristics associated with PC were low median absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) (0.5 vs. 0.7 x 109/L, p = 0.01), high international prognostic index (IPI) (61% vs. 35%, p = 0.001), and high CAR-HAEMATOTOX score18 (81% vs. 53%, p < 0.001). Factors included in IPI (extranodal sites >1 and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase) and in CAR-HAEMATOTOX (hemoglobin, platelet count, C-reactive protein, and serum ferritin) were also singularly significantly associated with PC (Table S1). In multivariate analysis, ALC (odds ratio [OR] 2.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–4.4; p = 0.03), high IPI (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.3–4.8; p = 0.007), and elevated CAR-HAEMATOTOX score (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.4–6; p = 0.004) maintained their association with PC.

Patients with PC, compared to those without, experienced a significantly higher frequency of CRS of any grade (98% vs. 86%, p = 0.007), grade 2–4 CRS (49% vs. 30%, p = 0.01), ICANS of any grade (75% vs. 39%, p < 0.001), and grade 3–4 ICANS (44% vs. 20%, p = 0.001) (Table S2). All associations were maintained after adjusting for IPI. Among the 89 patients with day 30 grade 3–4 cytopenia, a subsequent bone marrow biopsy was performed in 37 patients, after a median of 4 months (range, 0–27 months), before initiation of any subsequent line of therapy. Eight (22%) samples disclosed a pathological diagnosis, including myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 4), acute myeloid leukemia (n = 1), multiple myeloma (n = 1), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH, n = 1), and LBCL (n = 1). Among the remaining 29 samples, median cellularity was 25% (range, 0–100%). Among patients with PC, 42 (47%) needed red blood cell transfusions, 40 (45%) needed platelet transfusions, 54 (61%) needed growth factor support, and 27 (30%) were hospitalized for infectious complications after day 30, before initiation of any subsequent therapy. At most recent follow-up, 35 (39%) patients had PC, and median PC duration was 15 months (Figure S1B; 95% CI 1–29). After a median follow-up of 26 months (95% CI 24–28 months), no significant difference in median progression-free survival was observed when comparing patients with PC to those without (Figure S1C; 14 vs. 13.6 months, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon p = 0.477). However, patients with PC had a significantly shorter overall survival compared to those without (Figure S1D; 28 months vs. not reached, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon p = 0.048). Thus, although PC is not associated with progression from CAR T cell therapy, factors such as mortality from infections and exclusion from certain subsequent therapies following progression likely impact overall survival.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of bone marrow mononuclear cells from CAR T patients

To investigate the pathophysiology of CAR T-associated PC, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of bone marrow aspirates taken from 16 rrLBCL patients included in the above-described population. Samples were obtained at a median of 58.5 days (range 28–552) post infusion and included 11 patients with PC and five patients without (Table S3). PC was defined as grade 3–4 cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia) persisting beyond 30 days after CAR T cell infusion, not considering lymphopenia.10 Samples from patients without cytopenia were obtained for response assessment and samples with marrow involvement excluded from the analysis. Five bone marrow samples from healthy donors and one from a rrLBCL patient with chemotherapy-associated cytopenia were included as controls (Table S3). All rrLBCL bone marrow aspirates were analyzed fresh; healthy donor samples were previously cryopreserved. All samples were analyzed using 10x Genomics 5′GEX chemistry with paired T cell receptor (TCR) and B cell receptor (BCR) sequencing. Data were mapped to GRCh38 reference genome plus the CAR sequence as previously described.19,20 Following stringent quality control and doublet filtering, we obtained scRNA-seq data for 92,676 cells from bone marrow aspirates of 22 individuals. Cells from all samples were used for unsupervised clustering; two PC samples were excluded from subsequent comparative analysis due to involvement with AML/LBCL (Table S3). The cellularity of the bone marrow samples from remaining patients with (n = 9) or without PC (n = 5) was not significantly different (Student’s t test p value = 0.203; Table S3).

Unsupervised clustering with batch-effect normalization using Harmony21 identified 26 clusters, corresponding to distinct cell lineages and states that were classified using previously defined signatures,22,23 including CD8 T cells (C0-5), CD4 T cells (C7-8), mucosa-associated invariant T cells (MAIT, C6), natural killer cells (NK, C9-10), mature and progenitor B cells (C11-15), mature myeloid cells (C16-20), hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs, C23-25), and cycling lymphocytes (C22) (Figures 1A–1Eand S2 and Table S4). As expected, we observed significant differences between bone marrow samples from rrLBCL patients and healthy donors (Figures 1F and 1G). Although this analysis was partially confounded by different processing of samples from these groups, populations that are sensitive to cryopreservation (e.g., myeloid cells and plasma cells) are not differentially represented between rrLBCL and healthy donor samples. Importantly, we did not observe significant differences in the frequency of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or other progenitor populations between rrLBCL and healthy donor bone marrow samples (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

Single-cell RNA-seq of healthy donor and post-CAR T rrLBCL bone marrow

(A and B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of all bone marrow mononuclear cells surviving QC criteria (92,676 cells) colored by patient (A) or cluster ID (B).

(C and D) Stacked bar graphs show the number of cells falling within each cluster for each patient (C) and the number of cells from each patient falling within each cluster (D).

(E) A bubble plot shows cell lineage and subtype markers for all bone marrow mononuclear cell clusters shown in (B).

(F) A UMAP plot, showing clusters from (B), colored by the origin of the cell from either rrLBCL (pink) or healthy donor (green) bone marrow aspirates.

(G) scCODA analysis of the frequency of cells across each cell cluster comparing rrLBCL (n = 14) and healthy donor (n = 5) bone marrow aspirates. Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. ∗scCODA FDR < 0.05.

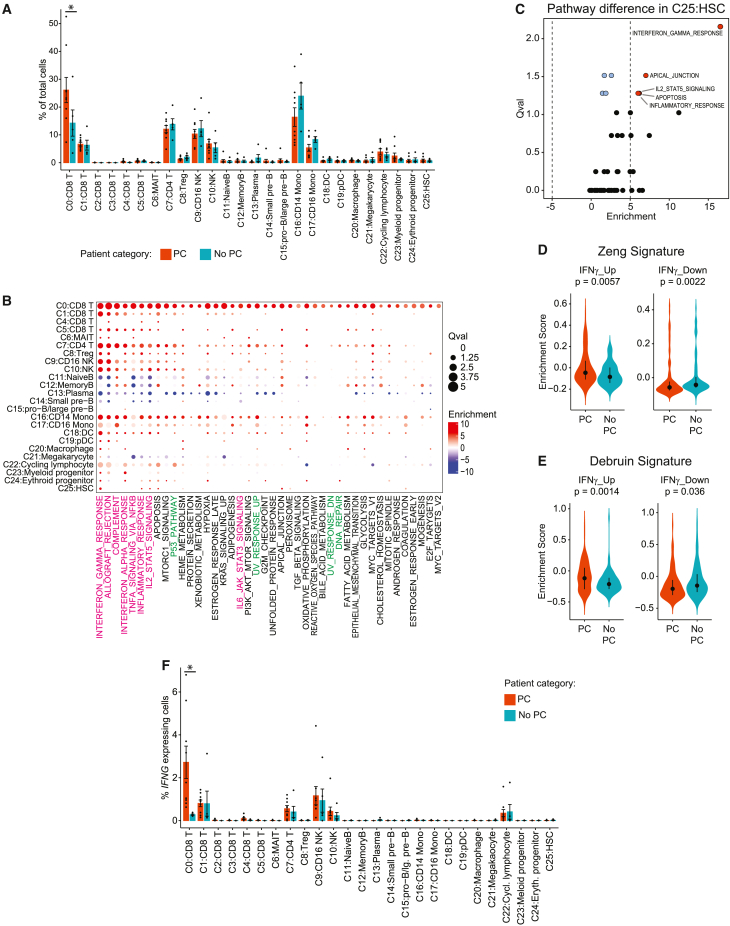

Skewed representation of CD8 T cell subsets and enrichment of interferon signaling in bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients with PC

To find characteristics associated with CAR T-associated PC, we compared the frequencies of bone marrow mononuclear cell clusters between patients with (n = 9) or without PC (n = 5) using scCODA, a Bayesian model developed to allow compositional analysis of single-cell datasets.24 Analysis of the frequency of each cell cluster relative to all cells from each sample identified a single subset of CD8 T cells, characterized by high expression of CX3CR1, GZMA/B/H, NKG7, and FGFBP2, as being significantly over-represented in samples from patients with PC compared to patients without PC (CD0:CD8; scCODA false discovery rate [FDR] = 0.02; Figure 2A). We extended this by performing single-cell pathway analysis (SCPA) of MSigDB hallmark pathways25 within each cluster (n = 24, two clusters were excluded due to insufficient cells), comparing cells from patients with PC to those without. This revealed a highly significant enrichment of inflammation-associated pathways such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ) response (SCPA adjusted p value <0.05) and multiple DNA repair pathway gene sets within C0:CD8 T cells from the bone marrow of patients with PC (Figure 2B and Table S5). The IFN-γ response signature was significantly enriched within PC samples across multiple cell clusters (Figure 2B) and was the most significantly enriched signature in HSCs (SCPA adjusted p value = 0.003; Figures 2B and 2C). IFN-γ has been previously shown to impair the self-renewal and skew the differentiation of HSCs.26 We therefore investigated the expression of two HSC IFN-γ-response signatures curated from the literature27,28 in HSCs from patients with or without PC. This confirmed increased expression of IFN-γ-induced genes and reduced expression of IFN-γ-suppressed genes in HSCs from patients with PC (Figures 2D and 2E). With the caveat of transcript dropout events that affect scRNA-seq data, we investigated the potential source of IFN-γ (gene symbol: IFNG) across bone marrow mononuclear cell clusters. The C0:CD8 T cell cluster expressed the highest levels of IFNG, and the percentage of IFNG-expressing cells was significantly higher in C0:CD8 T cells from patients with PC compared to patients without PC (Figure 2F; Wilcoxon test FDR = 0.024). Together, these data identify skewed representation of a CD8 T cell subset and associated IFN-γ signaling as a possible driver of impaired HSC function in patients with PC.

Figure 2.

Comparison of cell frequencies and signatures between bone marrow aspirates of CAR T patients with or without prolonged cytopenia

(A) scCODA analysis of the frequency of cells within each cluster in CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) compared to those without (n = 5). Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. ∗scCODA FDR < 0.05.

(B) A bubble plot shows SCPA for mSigDB hallmark gene sets across clusters of bone marrow mononuclear cells, comparing CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) to those without (n = 5). Gene sets with significant enrichment in any analyzed cluster from patients with prolonged cytopenia compared to those without are shown. Results for all pathways can be found in Table S5.

(C) A volcano plot shows SCPA for mSigDB hallmark gene sets in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), comparing CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) to those without (n = 5).

(D and E) Enrichment scores of IFN-γ-induced (IFNγ_Up) or suppressed (IFNγ_Down) genes from Zeng et al. (G) and Debruin et al. (H) comparing HSCs from CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (125 cells from nine patients) to those without (87cells from five patients). Dot and bars represent median and first to third quartile.

(F) IFNG-expressing cells across each cluster of bone marrow mononuclear cells, comparing cells from CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) to those without (n = 5). Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. ∗Wilcoxon test FDR < 0.05.

Over-representation of clonally expanded CX3CR1hi CD8 effector T cells in the bone marrow of CAR T patients with PC

To gain further insight into the nature of the over-represented CD8 T cell population, we performed re-clustering analysis and identified 11 clusters of bone marrow-derived CD8 T cells (Figures 3A–3C and S3 and Table S6). The frequencies of CD8 T cell subsets were significantly different between rrLBCL and healthy donor bone marrow samples, with significantly higher abundance of naive CD8 T cells within healthy donor samples and significantly higher frequencies of CX3CR1hi (C0) and CX3CR1lo (C1) effector T (TEFF) cells within CAR T patient samples (Figure S3). Focusing on differences between CAR T patients with PC versus those without, scCODA analysis revealed a significant over-representation of the most abundant cluster of CD8 T cells in PC samples, CX3CR1hi TEFF cells (scCODA FDR = 0.03; Figure 3D), characterized by high expression of granzymes (GZMA, GZMB, GZMH), FGFBP2, and CX3CR1 (Figure 3C and Table S6). CX3CR1hi TEFF cells represented a mean of 23% of bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients with PC (range = 6%–56%), 8% from those without (range = 2%–12%), and 3% from healthy donors (range = 1%–5%). In line with this, multispectral immunofluorescence imaging of available bone marrow cores from these patients showed significantly higher frequencies of CD3+CD8+GZMB+ cells in patients with PC (n = 7, median = 28.75 cells/mm2) compared to patients without PC (n = 6, median = 7.73 cells/mm2; one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum p = 0.0367; Figure S4). TCR analysis revealed a significant enrichment of expanded TCR clonotypes within the CX3CR1hi TEFF cluster (Figure 3E). Expanded TCR clonotypes represented a significantly greater proportion of all CD8 T cells (Wilcoxon test p value < 2 x 10–16 for all clonotypes; p = 3.9 x 10−5 for top 10 clonotypes; Figure 3F) and a greater proportion of the CX3CR1hi TEFF cluster (Wilcoxon test p value < 2 x 10–16 for all clonotypes; p = 0.00038 for top 10 clonotypes; Figure 3G) in patients with PC compared to those without. TCR motif analysis did not reveal any significantly over-represented motifs that would be suggestive of a shared antigen between clonally expanded populations (Table S7). Moreover, the analysis of STAT3 mutations in scRNA-seq data29 did not identify a high frequency of mutation-bearing cells that would be suggestive of T cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia (T-LGL, Figure S5). The CX3CR1hi TEFF cluster expressed the highest levels of IFNG and TBX21 (Figures 3H–3K), the master regulator of IFN gene expression, and CX3CR1hi TEFF cells from patients with PC expressed significantly higher levels of IFNG and TBX21 compared to those from patients without PC (Figures 3H–3K). We validated this using spectral flow cytometry of samples with remaining cryopreserved cells, which showed significantly higher expression of IFN-γ in CD3+CD8+GZMB+ cells from patients with PC (n = 5, median MFI = 50,770) compared to patients with no PC (n = 3, median MFI = 5,932; one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test p = 0.016; Figures 3L and 3M). Increased CX3CR1 expression has been noted on CAR T cells at late time points 26–30 days following infusion.30 However, CD8 T cells within the bone marrow following CAR T therapy, including clonally expanded populations, rarely expressed the CAR transcript (Figure S5). Furthermore, analysis of previously published scRNA-seq data from axi-cel infusion products of 59 rrLBCL patients found no analogous CX3CR1hi CD8 T cell cluster, no significant differences in CD8 T cell populations, and only minor differences in clonality in infusion products from patients who went on to develop PC compared to patients who did not (Figure S6). Our data therefore do not definitively link the CX3CR1hi TEFF population to the CAR T cell infusion product because these cells do not express the CAR transcript. However, we cannot exclude it as the origin of these cells due to the phenotypic plasticity of T cells and the potential for rare clonotypes to contribute disproportionately to T cell expansion post infusion.31

Figure 3.

Characteristics of bone marrow CD8 T cell subsets associated with prolonged cytopenia

(A and B) UMAP plots of all CD8 T cells colored by patient (A) or cluster ID (B).

(C) Bubble plot of cluster markers for CD8 T cell clusters shown in (B).

(D) scCODA analysis of the frequency of cells within CD8 T-each cluster in CAR T-treated rrLBCL patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) compared to those without (n = 5). Bars and error bars represent mean +/- SEM. ∗scCODA FDR < 0.05.

(E) TCR clonotype frequency (left) and density of expanded TCR clonotypes (right) for CD8 T cells from CAR T patients with prolonged cytopenia (11,790 cell from nine patients) and those without (3,176 cells from five patients, excluding cells from control samples).

(F) Comparison of clonotype proportion for all CD8 T cells (left, 14,966 cells) and for expanded clonotypes (right, 8,477 cells) in patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) compared to those without (n = 5). Box represents median (bold line) and interquartile range, whiskers represent 1.5 x interquartile range, dots represent outliers. Statistical significance was assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

(G) Comparison of clonotype proportion for all CX3CR1hi TEFF cells (left, 12,822 cells) and for expanded CX3CR1hi TEFF cell clonotypes (right, 8,416 cells) in patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) compared to those without (n = 5). Box represents median (bold line) and interquartile range, whiskers represent 1.5 x interquartile range, dots represent outliers. Statistical significance was assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

(H) Density of IFNG+ cells shown over a UMAP of CD8 T cell clusters. Only CD8 T cells from rrLBCL patients (n = 14) are shown; healthy donor cells are excluded.

(I) The fraction of IFNG-expressing cells is shown comparing patients with prolonged cytopenia (n = 9) compared to those without (n = 5) for all CD8 T cells (left, 1,732 IFNG+ cells), and CX3CR1hi TEFF cells (right, 1,367 IFNG+ cells). Bars represent the mean; error bars represent standard error of the mean. Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. Statistical significance was assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

(J) Density of TBX21-expressing cells shown over a UMAP of CD8 T cell clusters. Only CD8 T cells (17,826 cells) from rrLBCL patients (n = 14) are shown; healthy donor cells are excluded.

(K) The fraction of TBX21-expressing cells is shown comparing patients with prolonged cytopenia to those without for all CD8 T cells (left) and CX3CR1hi TEFF cells (right). Bars represent the mean; error bars represent standard error of the mean. Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. Statistical significance was assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

(L) Spectral flow cytometry of residual cryopreserved bone marrow cells from patients with PC (n = 6) and those without PC (n = 3) showing the sub-sampled (1,000 cells per sample) MFIs for IFN-γ in CD3+CD8+GZMB+ cells.

(M) IFN-γ gMFI for all CD3+CD8+GZMB+ cells in each sample from patients with (n = 6) or without (n = 3) PC. Bars and error bars represent mean +/- standard error. p value represents a one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Discussion

Through our in-depth analysis of bone marrow samples from CAR T-treated patients with PC, we suggest that a subset of IFN-γ-expressing CD8 T cells and an associated enrichment of IFN-γ signaling within bone marrow HSCs may be responsible for the PC. These CD8 T cells were clonally expanded, expressed effector molecules such as GZMB and expressed the highest levels of CX3CR1. CX3CR1 is upregulated in a TCR-dependent manner and marks three populations with differential capacity for secondary immune responses and self-renewal. Within viral infection models, high CX3CR1 expression on TEFF cells marks a terminally differentiated subset that gives rise exclusively to other CX3CR1hi TEFF cells upon self-renewal,32 in line with our observed clonal expansion within this subset. CX3CR1+ CD8 T cells have been recognized as critical effectors following immune checkpoint blockade in humans33,34 but with contrasting results in mice.35 The origin of this clonally expanded T cell population within the bone marrow of CAR T patients remains to be defined. However, the implication of CX3CR1 in T cell bone marrow homing in other disease contexts such as idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura36 and the enrichment of DNA repair pathway genes within this subset together with prior observations that CX3CR1+ cytotoxic T cells are resistant to chemotherapy34 lead us to speculate that bone marrow-resident CX3CR1hi cells may be resistant to lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to CAR T cell infusion. Furthermore, the significant association of PC with high-grade CRS and ICANS in our retrospective cohort and previous data13 might suggest that the CX3CR1hi TEFF may clonally expand under inflammatory conditions following CAR T infusion. We observed that CX3CR1hi TEFF cells express the highest levels of IFNG, particularly in patients with PC, and both CX3CR1hi TEFF cells and HSCs from patients with PC show transcriptional evidence of an IFN response. Chronic IFN-γ signaling has a well-established link with primary and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH),37,38 altered HSC homeostasis,39 aplastic anemia,40 and immune-mediated graft failure following allogeneic stem cell transplantation.41 Based upon our data, we posit that chronic IFN-γ signaling driven by clonally expanded CX3CR1hi TEFF cells is also central to the etiology of CAR T-associated PC. Importantly, prior studies have shown that IFN-γ-driven bone marrow aplasia can be therapeutically targeted using thrombopoietin agonists such as eltrombopag.42 In addition, IFN-γ can be targeted using IFN-γ-neutralizing antibodies such as emapalumab, without compromising CAR T cell function.43,44,45 Eltrombopag and emapalumab are FDA approved for the treatment of aplastic anemia and primary HLH, respectively. Our observations therefore highlight potential therapeutic approaches to explore for targeting the pathobiology of CAR T-associated PC.

Limitations of the study

This study has a limited sample size as it is not standard practice to obtain bone marrow biopsies for LBCL patients, particularly in the absence of cytopenia. We have focused on the expansion of CX3CR1+ IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells that had significant differences in frequency within our population; however, there may be other reproducible but lower-magnitude changes that failed to reach statistical significance due to our limited sample size. The modest sample size also creates the potential for single outliers to have a disproportionately large effect on group means; however, the scCODA tool is specifically developed in order to account for comparisons between small groups of samples and control false discoveries. Orthogonal validation was performed using multispectral immunofluorescence imaging and flow cytometry; however, the combinations of markers that can be employed with these technologies are not as precise and as comprehensive as single-cell transcriptomics. Although strong evidence exists linking chronic IFN-γ signaling with HSC dysfunction,26 there may be some differences associated with the bone marrow microenvironment in CAR T cell patients. Model systems do not currently exist for CAR T-associated PC, and we were therefore unable to functionally probe the causative nature of CX3CR1hi IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells in driving PC. We therefore recommend that future interventional studies aimed at treating CAR T cell-associated PC incorporate correlative biomarker analysis to validate the expansion of IFNγ-producing CD8 T cells within patient bone marrow samples and their association with response to targeted interventions.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CD3ε Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | 85061 |

| Recombinant anti-CD4 Antibody | Abcam | ab133616 |

| CD8 Mouse Monoclonal Antibody | Epredia | MS457S |

| CD19 Monoclonal Antibody | Dako Omnis | GA65661-2 |

| Recombinant anti-CD34 Antibody | Abcam | ab81289 |

| Granzyme B Monoclonal Antibody | Leica | GRAN-B-L-CE |

| Granzyme K Monoclonal Antibody | Sigma | HPA063181 |

| BV480 CD3 Monoclonal Antibody | BD Bioscience | 414-0038-42; RRID: AB_2925606 |

| cFlour B548 Anti-Human CD8 | Cytek | R7-20097 |

| cFlour YG584 Anti-Human CD4 | Cytek | R7-20041 |

| R718 Mouse Anti-Human Granzyme B | BD Biosciences | 566964; RRID: 566964 |

| PE-CF594 Mouse Anit-Human Perforin | BD Biosciences | 563763; RRID: AB_2738410 |

| BV421 Mouse Anti-Human IL2 | BD Biosciences | 562914; RRID: AB_2737888 |

| TNF alpha Monoclonal Antibody | Cytek | RC-00146 |

| SB702 CX3CR1 Monoclonal Antibody | eBioScience | 67-6099-42; RRID: AB_2744894 |

| PE-Cy7 Mouse anti-Human CD45RA | BD Bioscience | 560675; RRID: AB_1727498 |

| AF647 Rat anti-TOX | BD Bioscience | 568356 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Bone marrow aspirates from allogeneic stem cell donors | MD Anderson Lymphoma Tissue Bank | IRB 2005-0656 |

| Bone marrow aspirates from large B-cell lymphoma patients post CD19 CAR T cell therapy | MD Anderson Lymphoma Tissue Bank | IRB 2005-0656 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Single cell gene expression matrices (GEO) | This paper | GSE216005 |

| Browsable analyzed data (CellXGene) | This paper | https://cellxgene.cziscience.com/collections/26b5b4f6-828c-4791-b4a3-abb19e3b1952 |

| Raw FASTQ files (EGA) | This paper | https://ega-archive.org/studies/EGAS00001006836 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| CellRanger | 10X Genomics | https://github.com/10XGenomics/cellranger |

| DoubletFinder | McGinnis et al.,46 | https://github.com/chris-mcginnis-ucsf/DoubletFinder |

| Seurat | Hao et al.,22 | https://github.com/satijalab/seurat |

| Harmony | Korsunsky et al.,21 | https://github.com/immunogenomics/harmony |

| CellTypist | Conde et al.,23 | https://github.com/Teichlab/celltypist |

| scCODA | Büttner et al.,24 | https://github.com/theislab/scCODA |

| SCPA | Bibby et al.,25 | https://github.com/jackbibby1/SCPA/ |

| Nebulosa | Alquicira-Hernandez et al. 2021 | https://github.com/powellgenomicslab/Nebulosa |

| VarTrix | 10X GENOMICS | https://github.com/10xgenomics/vartrix |

| GLIPH2 | Huang et al.,47 | http://50.255.35.37:8080/ |

| R v4.1.0 | CRAN | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

| Scanpy | Wolf et al., 2018 | https://github.com/scverse/scanpy |

| inForm Tissue Analysis Software (v2.6) | Akoya Biosciences | https://www.akoyabio.com/phenoimager/software/inform-tissue-finder/ |

| Other | ||

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ Library and Gel Bead Kit v1.1 | 10X GENOMICS | 1000165 |

| Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit | 10X GENOMICS | 1000127 |

| Chromium Single Cell 5′ Library Construction Kit | 10X GENOMICS | 1000020 |

| Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Enrichment Kit, Human B Cell | 10X GENOMICS | 1000016 |

| Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Enrichment Kit, Human T cell | 10X GENOMICS | 1000005 |

| Single Index Kit T Set A | 10X GENOMICS | 1000213 |

| SPRIselect Reagent Kit | Beckman Coulter | B23318 |

| Ethanol, Pure (200 Proof, anhydrous) | Millipore Sigma | E7023-500ML |

| 10% Tween 20 | Bio-Rad | 1662404 |

| Glycerin (glycerol), 50% (v/v) Aqueous Solution | Ricca Chemical Company | 3290–32 |

| High Sensitivity D5000 ScreenTape | Agilent | 5067–5592 |

| High Sensitivity D5000 Reagents | Agilent | 5067–5593 |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Q32854 |

| Nuclease-free Water | Thermo Fisher Scientific | AM9937 |

| Buffer EB | Qiagen | 19086 |

| Lymphoprep™ | STEMCELL Technologies | 07811 |

| SepMate™-50 | STEMCELL Technologies | 85450 |

| RPMI 1640 | Gibco | 61870036 |

| Ghost Dye Violet 450 | Cytek | 13-0863-T100 |

| Cell Stimulation Cocktail with Protein Transport Inhibitors | eBiosciences | 00-4975-93 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Michael Green (mgreen5@mdanderson.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and study participant details

Retrospective analysis of patient outcome

This is a retrospective cohort analysis of 240 consecutive patients with relapsed or refractory LBCL treated with standard of care axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) at our institution, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), between 01/2018 and 12/2021. Standard of care was defined as administration of commercial product outside of a clinical trial. Data cut-off was 03/2022. Patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy (LDC) with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) administered intravenously on days −5, −4 and −3, followed by axi-cel infusion (2 x 106 cells/kg) on day 0. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MDACC and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Prospective collection of patient bone marrow samples

Patient samples were collected following informed consent under a protocol approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Internal Review Board (Protocol number 2005-0656), and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Bone marrow aspirates were collected from 16 patients with rrLBCL treated with axi-cel, of whom 11 had prolonged cytopenia and 5 patients did not. Five healthy donor bone marrow samples collected from allogeneic transplantation donors and 1 bone marrow sample collected from a rrLBCL patient with chemotherapy-associated cytopenia were included as controls. Cytopenia was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5 and prolonged cytopenia was defined as G3-4 cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia) persisting beyond 30 days after axi-cel infusion. Age and gender of LBCL patients can be found in Table S3, but are not available for healthy donors.

Method details

Retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes in patients with prolonged cytopenia

Baseline characteristics were collected on day −5, before initiation of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune-effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) were prospectively graded for up to 30 days after axi-cel infusion, according to the CARTOX grading system from 01/2018 to 04/2019, and according to ASTCT criteria from 05/2019 onward.8,48 Cytopenia was graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5 and prolonged cytopenia was defined as G3-4 cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia) persisting beyond 30 days after axi-cel infusion. Performance status was defined according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG).49 The international prognostic index (IPI) and the CAR-HAEMATOTOX score were calculated as previously described.18,50 Response status was determined by the Lugano 2014 classification.51

Processing of bone marrow samples

LymphoprepTM density gradient medium and SepMateTM tubes (STEMCELL Technologies Inc.) were used for isolation of mononuclear cells (MNCs) from bone marrow aspirates, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MNCs concentration was evaluated using a hemocytometer. To avoid freezing and thawing of bone marrow cells, fresh cells were immediately applied to the 10X Chromium platform.

Single cell RNA-Seq and paired B-cell or T cell receptor (BCR/TCR) sequencing

scRNA-sequencing libraries were generated using a 10x Genomics Chromium Controller instrument and Chromium Single-Cell 5′ V5.1 reagent kits (10x Genomics). In brief, cells were concentrated to 1,000 cells per μL and cells were loaded into each channel to generate single-cell Gel Bead-In-Emulsions (GEMs), resulting in mRNA barcoding of an expected 5,000 single cells for each sample. After the reverse transcription step, GEMs were broken and single-strand cDNA was cleaned up with DynaBeads. The amplified barcoded cDNA was fragmented, A-tailed, ligated with adaptors and amplified by index PCR. cDNA and constructed libraries were assessed by High Sensitivity D5000 DNA Screen Tape analysis (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing was conducted on an Illumina NovaSeq sequencer with 2 × 100 bp paired reads to reach a depth of at least 50,000 read pairs per cell. The Chromium Single-Cell V(D)J Enrichment Kit was used to enrich immune repertoire, TCR or B-cell immunoglobulin (Ig) transcripts. The single-cell V(D)J enriched libraries were sequenced at 2 × 150 bp with a minimum depth of 5,000 read pairs per cell.

Computational analysis

Raw sequencing data processing, QC, data filtering and normalization

The raw scRNA-seq data were pre-processed (demultiplex cellular barcodes, read alignment (genome reference build: GRCh38) and generation of feature-barcode matrix) using Cell Ranger (10X Genomics, v6.0.0). The CAR transcript reference built by Haradhvala et al.20 were aligned with reads to determine unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts of CAR expression. Detailed QC metrics were generated and evaluated. Genes detected in fewer than three cells and cells where fewer than 200 genes had nonzero counts were filtered out and excluded from subsequent analysis. Low-quality cells where more than 15% of the read counts derived from the mitochondrial genome were also discarded. Seurat (version 4.1.0)22 was applied to the filtered gene–cell matrix of UMI counts to generate the normalized data using the LogNormalize method. Potential doublets predicted by DoubletFinder46 were discarded. In addition, cells with more than 4,000 detected genes were discarded to remove likely doublet or multiplet captures. The resulting cells were further filtered using the following criteria to clean additional possible doublets: (i) The cells with both productive BCRs and TCRs were removed. (ii) For non-B lineages derived from unsupervised clustering analysis, we further filtered out cells expressing productive BCRs; similarly, for non-T cell lineages, we filtered out cells expressing productive TCRs. (iii) We observed potential doublets formed between erythrocyte linages and other cell lineages derived from unsupervised clustering analysis. As erythrocytes are not our focus in this study, we discarded cells having the mean of HBA1, HBA2, and HBB expressions greater than 2 based on the normalized data. Together, after these stringent filtering criteria, we obtained a total of 92,676 high-quality cells. We next performed principal component analysis (PCA), batch-effect correction, unsupervised cell clustering, and dimensionality reduction using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP).52 The results of PCA, UMAP plots, and sample-by-cluster distribution were carefully reviewed.

PCA, batch-effect correction, unsupervised cell clustering, and dimensionality reduction

Seurat was used to identify highly variable genes. To avoid forming small, isolated clusters dominated by monoclonal T or B cells, we excluded TCR and immunoglobulin genes from the highly variable genes. In total, 3,000 most highly variable genes were used for PCA. Based on the elbow plot generated after PCA, the number of significant principal components (PC) was determined. The first 100 PCs, which explains 31% of variance of the data, were used for this study. The embedding space defined by the first 100 PCs were batch-effect corrected using Harmony.21 The corrected embeddings were then used for unsupervised cell clustering using Louvain method and dimensionality reduction using UMAP. Different resolution parameters for Louvain clustering were examined to determine the optimal number of clusters. For this study, the resolution was set to 0.4, yielding a total of 26 cell clusters.

DEGs, determination of major cell types and cell states

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified for each cluster using the FindMarkers function of Seurat, and the DEG list was filtered with the criteria to select genes that are expressed in 25% or a greater fraction in the more abundant group with the absolute expression fold change >1.2. The significant DEGs (FDR q-value <0.05) were examined, and an integrative approach was used to determine cell types and states. The major cell types were defined by canonical marker gene expressions (CD8 T cells: CD3E and CD8A; CD4 T cells: CD3E and CD4; NK cells: NCAM1; B cells: CD19, MS4A1, SDC1; myeloid cells: CD68; cycling cells: MKI67; and HSC: CD34). Additionally, we employed two automatic approaches to assist annotations of cell types and cell states: (i) Seurat was applied to map cells of each sample to a CITE-seq reference dataset of human bone marrow mononuclear cells that was previously analyzed,22 wherein the labels of cell type annotations were transferred; (ii) CellTypist,23 a trained machine learning model for predicting human immune cell types from scRNA-seq data, was applied to predict cell type annotations. Together, the final annotation of cell types and states were determined in an integrative way by canonical marker genes, DEGs, and predictions from automatic approaches.

Cell composition analysis and pathway analysis

To detect compositional changes of cell types between different conditions, e.g., samples with vs. without prolonged cytopenias, we applied scCODA,24 a Bayesian method that models the dependence of different cell type proportions (i.e., sum to 1) and controls for false discoveries. We employed SCPA25 to compare gene set enrichment between samples with vs. without prolonged cytopenia using the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. From the SCPA analysis, a fold change (FC) enrichment score is calculated as the sum of mean changes in gene expression from all genes of the pathway. Qval, defined as sqrt(–log10(Bonferroni-adjusted p value)), is used to interpret statistical significance of pathway differences.

IFNγ signature scores in HSC

To study HSC-specific response due to IFNγ stimulation, the AddModuleScore function of Seurat was used to calculate signature scores of the HSC cluster derived from unsupervised clustering analysis. The signature scores were based on two gene sets derived from IFNγ-induced gene expression changes of HSC: (i) gene sets from Table 3 of Zeng et al.,27 which includes up and down regulated genes in CD34 cells treated with IFNγ in vitro; (2) gene sets derived from de Bruin et al.,28 including IFNγ-induced upregulated genes in HSC (STAT1, SOCS1, SOCS3, SPI1, IRF1, IRF2, IRF8, and CDKN1C) and IFNγ-induced downregulated genes in HSC (CCND1, RUNX1, CEBPA, IL5RA, and GATA1).

Re-clustering of CD8 T cells

To gain more granularity of CD8 T cell states, we selected 33,750 cells of the CD8 T compartment from unsupervised clustering of all cells. Using this subset of cells, we identified highly variable genes and performed PCA, batch-effect correction, unsupervised clustering, and dimensionality reduction as above. The first 100 PCs were used for Louvain clustering with the optimal resolution set to 0.3, yielding a total of 11 cell clusters. Cell clusters were annotated based on an integrative approach of marker gene expressions, DEGs, and automatic predictions as above. To overcome the data sparsity issue of gene expression due to dropout and low expression when visualized on UMAP, we applied Nebulosa,53 a weighted kernel density estimation method using the information from neighboring cells, to plot density of gene expression on UMAP.

Detection of somatic variants associated with T-LGL. We applied Vartrix54 with default parameters to scRNA-seq data against the whole COSMIC database (v95) to detect somatic variants as described previously.29 Only T-LGL characteristic variants of STAT3 (Y640F, S614R, N647I, I659L, D661Y) were retained. We further imputed variants for cells that have same TCR clonotypes shared by cells having detected variants.

V(D)J sequence assembly, paired clonotype calling, and integration with scRNA-seq data

Cell Ranger v6.0.0 for V(D)J sequence assembly was applied for TCR/BCR reconstruction and paired TCR/BCR clonotype calling. The CDR3 motif was located and the productivity was determined. The clonotype landscape was then assessed and the clonal fraction of each identified clonotype was calculated. The TCR/BCR clonotype data were then integrated with the scRNA-seq data based on their shared unique cell barcodes.

TCR clustering

To identify motifs of expanded TCR clonotypes shared across samples, we applied GLIPH247 to the TCR clonotypes pooled from top 25 expanded clonotypes of each sample with prolonged cytopenia. The default parameters of GLIPH2 and the unselected naive TCR reference files from human v2.0 were used. Similarly, we did TCR clustering for samples without prolonged cytopenia.

Analysis of CD8 T cells from anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion products

To interrogate the association of prolonged cytopenia with characteristics of anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion products, we analyzed a previously published dataset that included paired scRNA-sequencing and TCR-sequencing data of CAR T cell infusion products from 40 patients19 and 19 additional patients. In this patient cohort, 16 patients had prolonged cytopenia, 14 patients didn’t have prolonged cytopenia, and 29 other patients either had bone marrow involvements or were not evaluable due to additional interventions. The scRNA-sequencing data were available for all patients, and the TCR-sequencing data were available for all patients except 1 patient with prolonged cytopenia. The raw scRNA-sequencing and TCR-sequencing data were pre-processed using Cell Ranger (10X Genomics, v6.0.0) to generate feature-barcode matrix and TCR clonotype data, respectively. Next, for scRNA-sequencing data, cells and genes were filtered using the same filtering criteria described in Deng et al.19 and potential doublets predicted by DoubletFinder were discarded. In total, we obtained 417,167 high-quality cells. Then, we employed a K-nearest neighbors approach as used in Haradhvala et al.20 to calculate smoothed expressions of CD3 (average of CD3D, CD3E, CD3G, and CD247), CD8 (average of CD8A and CD8B), and CD4. We stringently defined CD3+CD8+CD4−cells as CD8+ cells using smoothed gene expressions. In total, 147,095 CD3+CD8+CD4−cells were selected. Using this subset of cells, Scanpy (version 1.8.2) was applied to generate the normalized data using the LogNormalize method. We then identified 3,000 highly variable genes and performed PCA. Based on the elbow plot generated after PCA, the first 20 PCs were used for the downstream analysis. We performed batch-effect correction using Harmony followed by Leiden clustering with the optimal resolution set to 1.0, yielding a total of 13 cell clusters. We compared compositional changes of cell clusters between samples with vs. without prolonged cytopenia using scCODA. After matching TCR clonotype data to the CD8 T cells based on their shared unique cell barcodes, we compared TCR clonotype proportions of top expanded CD8 T cells between samples with vs. without prolonged cytopenia.

Multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF)

Four-microns thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) bone marrow clot samples were used for this analysis. We optimized and validated a mIF panel using CD3ε, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD34, GZMB, and GZMK. Each antibody was assessed with a uniplex immunofluorescence panel using the Opal 9 kit (NEL797001KT; Akoya Biosciences), according to the following clones and dilutions: CD3ε (D7A6E, CST, 1:100), CD4 (EPR6855, Abcam, 1:200), CD8 (C8/144B, Epredia, 1:25), CD19 (LE-CD19, Dako, 1:300), CD34 (EP373Y, Abcam, 1:100), GZMB (11F1, Leica, RTU), and GZMK (clone HPA063181, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:100). The slide was imaged using the VectraPolaris multispectral imaging system (Akoya Biosciences) with a fluorescence protocol at 10 nm λ from 420 nm to 720 nm in low magnification at ×10, and then the whole tissue was selected with a high magnification at ×40. Both germinal center and interfollicular areas from lymph nodes with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia were used as a control. The whole tissue was selected for the analysis. After the preparation of the image, tissue was segmented in tumor and glass areas, followed by cell segmentation. Each marker was analyzed at the single-cell level, and a supervised algorithm was tailored for each case using Inform software 2.6 (Akoya Biosciences). Data consolidation was performed with the Spotfire software program (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA).

Flow cytometry of patient bone marrow

Viably cryopreserved bone marrow mononuclear cells were thawed and cultured in RMPI 1640 medium (Gibco Cat: 61870036) supplemented with 10% FBS and Cell Stimulation Cocktail (eBioscience) for 4 h at 37°C in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Samples were transferred to FACS tubes, washed using PBS +1% BSA, and stained for viability and extracellular and intracellular proteins according to manufacturer specifications (eBioscience Cat: 00-5523-00). Data were acquired on a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer. Data were analyzed on FlowJo software, gating on live CD3+ cells, then CD8+GZMB+ (Figure 3L) and evaluating the expression of IFN-γ. So that samples with larger cell numbers did not bias distributions in the histogram, we randomly sampled 1,000 CD3+CD8+GZMB+ cells from each sample for display in Figures 3L and3M shows the MFI for all cells from a given sample.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes in patients with prolonged cytopenia

Association between categorical variables was evaluated using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The difference in a continuous variable between patient groups was evaluated by the Mann-Whitney test. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the start of axi-cel infusion to progression of disease, death, or last follow-up (whichever occurred first). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of axi-cel infusion to death or last follow-up. PFS and OS were calculated for all patients in the study and for subgroups of patients using Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared between subgroups using a Genhan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Only factors significant (p value ≤ 0.05) on univariate analysis were included in multivariate models. Logistic regression was used to assess associations between patient characteristics and prolonged cytopenia.

Additional statistical criteria

In addition to the bioinformatics approaches described for scRNA/TCR-sequencing data analysis, all other statistical analysis was performed using statistical software R v4.1.0. Analysis of differences in fractions of IFNG+ cells, fractions of TBX21+ cells, and IFN-γ signature scores of HSC, of samples with vs. without prolonged cytopenia was determined by the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To control for multiple hypothesis testing, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg method to correct p values, and the false discovery rates (FDR) were calculated. All statistical significance testing was two-sided and results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 and FDR <0.05 unless otherwise stated.

Acknowledgments

P.S. is supported by a Lymphoma Research Foundation Career Development Award, a Leukemia Lymphoma Society Career Development Program, a Kite-Gilead Scholar in Clinical Research Award, and a Sabin Family Fellowship Award. M.R.G. is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. This research was supported by the Schweitzer Family Fund and the Futcher Foundation. The MD Anderson Lymphoma Tissue Bank is supported by KW Cares. The authors thank the technical support of the following TMP-IL members: Luisa M. Solis, Mei Jiang, Wei Lu, Khaja Kan, and Jianling Zhou.

Author contributions

P.S., S.S.N., and M.R.G. conceived of, designed, and supervised the study. Q.D. and M.L.M.-P. performed experiments. X.L., F.V., L.W., and M.R.G. analyzed data. J.H., G.W., L.D., T.C., N.S., K.T., and P.S. collected data. P.S., L.E.F., S.P.I., L.J.N., F.B.H., N.H.F., J.R.W., R.E.S., R.N., S.A., G.A.-A., and S.S.N. enrolled patients. M.R.G. and P.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and agreed to the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

M.R.G. reports research funding from Sanofi, Kite/Gilead, Abbvie, and Allogene; consulting for Abbvie; honoraria/consulting fees from Tessa Therapeutics, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, and Abbvie; and stock ownership of KDAc Therapeutics. S.S.N. received research support from Kite/Gilead, BMS, Cellectis, Poseida, Allogene, Unum Therapeutics, Precision Biosciences, and Adicet Bio; served as Advisory Board Member/Consultant for Kite/Gilead, Merck, Novartis, Sellas Life Sciences, Athenex, Allogene, Incyte, Adicet Bio, BMS, Legend Biotech, Bluebird Bio, Fosun Kite, Sana Biotechnology, Caribou, Astellas Pharma, Morphosys, Janssen, Chimagen, ImmunoACT, and Orna Therapeutics; has received royalty income from Takeda Pharmaceuticals; has stock options from Longbow Immunotherapy, Inc; and has intellectual property related to cell therapy. P.S. received research support from Sobi, AstraZeneca/Acerta, ALX Oncology, and ADC Therapeutics; and served as Advisory Board Member/Consultant for Kite/Gilead, Roche/Genentech, Incyte/Morphosys, ADC Therapeutics, TG Therapeutics, Hutchinson/MediPharma, and AstraZeneca/Acerta. R.N. reports speakership for Incyte. J.R.W. reports consulting for Kite/Gilead, BMS, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Morphosys/Incyte, Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, Calithera, Kymera, Merck, MonteRosa, SeaGen, and Abbvie; and research funding from Kite/Gilead, BMS, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Morphosys/Incyte, Janssen, ADC Therapeutics, Calithera, and Kymera. S.A. reports research funding from Seattle Genetics, Merck, Xencor, Chimagen, and Tessa Therapeutics; advisory board membership or consulting for Tessa Therapeutic’s, Chimagen, ADC Therapeutics, and KITE/Gilead; and data safety monitoring board membership for Myeloid Therapeutics. L.J.N. reports honoraria for participation on advisory boards from ADC Therapeutics, Atara, BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Epizyme, Genentech, Genmab, Gilead/Kite, Janssen, Morphosys, Novartis, and Takeda; research support from BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Epizyme, Genentech, Genmab, Gilead/Kite, Janssen, IGM Biosciences, Novartis, and Takeda; and serves on a DSMB for DeNovo, Genentech, MEI, and Takeda. C.R.F. reports consulting for Abbvie, Bayer, BeiGene, Celgene, Denovo Biopharma, Foresight Diagnostics, Genentech/Roche, Genmab, Gilead, Karyopharm, N-Power Medicine, Pharmacyclics/Janssen, SeaGen, and Spectrum; research funding from 4D, Abbvie, Acerta, Adaptimmune, Allogene, Amgen, Bayer, Celgene, Cellectis EMD, Gilead, Genentech/Roche, Guardant, Iovance, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kite, Morphosys, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, Takeda, TG Therapeutics, Xencor, Ziopharm, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, National Cancer Institute, V Foundation, and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas: CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research; and stock ownership in Foresight Diagnostics, N-Power Medicine. F.V. reports research funding from Allogene and Geron corporation; and honoraria from i3Health, Elsevier, America Registry of Pathology, Society of Hematology Oncology, and CRISP Therapeutics. K.T. reports consulting for Symbio Pharaceuticals and honoraria from Mission Bio. R.E.S. reports research funding from SeaGen, BMS, GSK, and Rafael Pharmaceuticals.

Published: August 15, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101158.

Contributor Information

Sattva S. Neelapu, Email: sneelapu@mdanderson.org.

Michael R. Green, Email: mgreen5@mdanderson.org.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Gene expression matrices have been deposited at GEO and CellXGene, and raw FASTQ files have been deposited in EGA. All data are publicly available as of the date of publication and accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Nastoupil L.J., Jain M.D., Feng L., Spiegel J.Y., Ghobadi A., Lin Y., Dahiya S., Lunning M., Lekakis L., Reagan P., et al. Standard-of-Care Axicabtagene Ciloleucel for Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Results From the US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:3119–3128. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neelapu S.S., Locke F.L., Bartlett N.L., Lekakis L.J., Miklos D.B., Jacobson C.A., Braunschweig I., Oluwole O.O., Siddiqi T., Lin Y., et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2531–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster S.J., Svoboda J., Chong E.A., Nasta S.D., Mato A.R., Anak Ö., Brogdon J.L., Pruteanu-Malinici I., Bhoj V., Landsburg D., et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2545–2554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson J.S., Palomba M.L., Gordon L.I., Lunning M.A., Wang M., Arnason J., Mehta A., Purev E., Maloney D.G., Andreadis C., et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet. 2020;396:839–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop M.R., Dickinson M., Purtill D., Barba P., Santoro A., Hamad N., Kato K., Sureda A., Greil R., Thieblemont C., et al. Second-Line Tisagenlecleucel or Standard Care in Aggressive B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:629–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locke F.L., Miklos D.B., Jacobson C.A., Perales M.A., Kersten M.J., Oluwole O.O., Ghobadi A., Rapoport A.P., McGuirk J., Pagel J.M., et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:640–654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westin J.R., Oluwole O.O., Kersten M.J., Miklos D.B., Perales M.A., Ghobadi A., Rapoport A.P., Sureda A., Jacobson C.A., Farooq U., et al. Survival with Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;389:148–157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neelapu S.S., Tummala S., Kebriaei P., Wierda W., Gutierrez C., Locke F.L., Komanduri K.V., Lin Y., Jain N., Daver N., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:47–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris E.C., Neelapu S.S., Giavridis T., Sadelain M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022;22:85–96. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain T., Olson T.S., Locke F.L. How I treat cytopenias after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood. 2023;141:2460–2469. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022017415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strati P., Wierda W., Burger J., Ferrajoli A., Tam C., Lerner S., Keating M.J., O'Brien S. Myelosuppression after frontline fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: analysis of persistent and new-onset cytopenia. Cancer. 2013;119:3805–3811. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strati P., Varma A., Adkins S., Nastoupil L.J., Westin J., Hagemeister F.B., Fowler N.H., Lee H.J., Fayad L.E., Samaniego F., et al. Hematopoietic recovery and immune reconstitution after axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2021;106:2667–2672. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.254045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain T., Knezevic A., Pennisi M., Chen Y., Ruiz J.D., Purdon T.J., Devlin S.M., Smith M., Shah G.L., Halton E., et al. Hematopoietic recovery in patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for hematologic malignancies. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3776–3787. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nahas G.R., Komanduri K.V., Pereira D., Goodman M., Jimenez A.M., Beitinjaneh A., Wang T.P., Lekakis L.J. Incidence and risk factors associated with a syndrome of persistent cytopenias after CAR-T cell therapy (PCTT) Leuk. Lymphoma. 2020;61:940–943. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1697814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taneja A., Jain T. CAR-T-OPENIA: Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy-associated cytopenias. EJH. 2022;3:32–38. doi: 10.1002/jha2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bezerra E.D., Iqbal M., Munoz J., Khurana A., Wang Y., Maurer M.J., Bansal R., Hathcock M.A., Bennani N., Murthy H.S., et al. Barriers to enrollment in clinical trials of patients with aggressive B-Cell NHL that progressed after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2023;7:1572–1576. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saini N.Y., Swoboda D.M., Greenbaum U., Ma J., Patel R.D., Devashish K., Das K., Tanner M.R., Strati P., Nair R., et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated with Increased Risk of Severe Neurotoxicity in Axicabtagene Ciloleucel Therapy of Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3:385–393. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rejeski K., Perez A., Sesques P., Hoster E., Berger C., Jentzsch L., Mougiakakos D., Frölich L., Ackermann J., Bücklein V., et al. CAR-HEMATOTOX: a model for CAR T-cell-related hematologic toxicity in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2021;138:2499–2513. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020010543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng Q., Han G., Puebla-Osorio N., Ma M.C.J., Strati P., Chasen B., Dai E., Dang M., Jain N., Yang H., et al. Characteristics of anti-CD19 CAR T-cell infusion products associated with efficacy and toxicity in patients with large B-cell lymphomas. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1878–1887. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haradhvala N.J., Leick M.B., Maurer K., Gohil S.H., Larson R.C., Yao N., Gallagher K.M.E., Katsis K., Frigault M.J., Southard J., et al. Distinct cellular dynamics associated with response to CAR-T therapy for refractory B cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1848–1859. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korsunsky I., Millard N., Fan J., Slowikowski K., Zhang F., Wei K., Baglaenko Y., Brenner M., Loh P.R., Raychaudhuri S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao Y., Hao S., Andersen-Nissen E., Mauck W.M., 3rd, Zheng S., Butler A., Lee M.J., Wilk A.J., Darby C., Zager M., et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184:3573–3587.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domínguez Conde C., Xu C., Jarvis L.B., Rainbow D.B., Wells S.B., Gomes T., Howlett S.K., Suchanek O., Polanski K., King H.W., et al. Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Science. 2022;376:eabl5197. doi: 10.1126/science.abl5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Büttner M., Ostner J., Müller C.L., Theis F.J., Schubert B. scCODA is a Bayesian model for compositional single-cell data analysis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6876. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bibby J.A., Agarwal D., Freiwald T., Kunz N., Merle N.S., West E.E., Singh P., Larochelle A., Chinian F., Mukherjee S., et al. Systematic single-cell pathway analysis to characterize early T cell activation. Cell Rep. 2022;41:111697. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morales-Mantilla D.E., King K.Y. The Role of Interferon-Gamma in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Development, Homeostasis, and Disease. Curr. Stem Cell Rep. 2018;4:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s40778-018-0139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng W., Miyazato A., Chen G., Kajigaya S., Young N.S., Maciejewski J.P. Interferon-gamma-induced gene expression in CD34 cells: identification of pathologic cytokine-specific signature profiles. Blood. 2006;107:167–175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Bruin A.M., Voermans C., Nolte M.A. Impact of interferon-gamma on hematopoiesis. Blood. 2014;124:2479–2486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-568451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huuhtanen J., Bhattacharya D., Lönnberg T., Kankainen M., Kerr C., Theodoropoulos J., Rajala H., Gurnari C., Kasanen T., Braun T., et al. Single-cell characterization of leukemic and non-leukemic immune repertoires in CD8(+) T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1981. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29173-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheih A., Voillet V., Hanafi L.A., DeBerg H.A., Yajima M., Hawkins R., Gersuk V., Riddell S.R., Maloney D.G., Wohlfahrt M.E., et al. Clonal kinetics and single-cell transcriptional profiling of CAR-T cells in patients undergoing CD19 CAR-T immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:219. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13880-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson T.L., Kim H., Chou C.H., Langfitt D., Mettelman R.C., Minervina A.A., Allen E.K., Métais J.Y., Pogorelyy M.V., Riberdy J.M., et al. Common Trajectories of Highly Effective CD19-Specific CAR T Cells Identified by Endogenous T-cell Receptor Lineages. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:2098–2119. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerlach C., Moseman E.A., Loughhead S.M., Alvarez D., Zwijnenburg A.J., Waanders L., Garg R., de la Torre J.C., von Andrian U.H. The Chemokine Receptor CX3CR1 Defines Three Antigen-Experienced CD8 T Cell Subsets with Distinct Roles in Immune Surveillance and Homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;45:1270–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamauchi T., Hoki T., Oba T., Jain V., Chen H., Attwood K., Battaglia S., George S., Chatta G., Puzanov I., et al. T-cell CX3CR1 expression as a dynamic blood-based biomarker of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1402. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Y., Cao S., Liu X., Harrington S.M., Bindeman W.E., Adjei A.A., Jang J.S., Jen J., Li Y., Chanana P., et al. CX3CR1 identifies PD-1 therapy-responsive CD8+ T cells that withstand chemotherapy during cancer chemoimmunotherapy. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e97828. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamauchi T., Hoki T., Oba T., Saito H., Attwood K., Sabel M.S., Chang A.E., Odunsi K., Ito F. CX3CR1-CD8+ T cells are critical in antitumor efficacy but functionally suppressed in the tumor microenvironment. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e133920. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsson B., Ridell B., Carlsson L., Jacobsson S., Wadenvik H. Recruitment of T cells into bone marrow of ITP patients possibly due to elevated expression of VLA-4 and CX3CR1. Blood. 2008;112:1078–1084. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jordan M.B., Hildeman D., Kappler J., Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Blood. 2004;104:735–743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Matteis A., Colucci M., Rossi M.N., Caiello I., Merli P., Tumino N., Bertaina V., Pardeo M., Bracaglia C., Locatelli F., et al. Expansion of CD4dimCD8+ T cells characterizes macrophage activation syndrome and other secondary HLH. Blood. 2022;140:262–273. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldridge M.T., King K.Y., Goodell M.A. Inflammatory signals regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin F.C., Karwan M., Saleh B., Hodge D.L., Chan T., Boelte K.C., Keller J.R., Young H.A. IFN-gamma causes aplastic anemia by altering hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell composition and disrupting lineage differentiation. Blood. 2014;124:3699–3708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-549527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merli P., Caruana I., De Vito R., Strocchio L., Weber G., Bufalo F.D., Buatois V., Montanari P., Cefalo M.G., Pitisci A., et al. Role of interferon-gamma in immune-mediated graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2019;104:2314–2323. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarado L.J., Huntsman H.D., Cheng H., Townsley D.M., Winkler T., Feng X., Dunbar C.E., Young N.S., Larochelle A. Eltrombopag maintains human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells under inflammatory conditions mediated by IFN-gamma. Blood. 2019;133:2043–2055. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-884486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Locatelli F., Jordan M.B., Allen C., Cesaro S., Rizzari C., Rao A., Degar B., Garrington T.P., Sevilla J., Putti M.C., et al. Emapalumab in Children with Primary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1811–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey S.R., Vatsa S., Larson R.C., Bouffard A.A., Scarfò I., Kann M.C., Berger T.R., Leick M.B., Wehrli M., Schmidts A., et al. Blockade or Deletion of IFNgamma Reduces Macrophage Activation without Compromising CAR T-cell Function in Hematologic Malignancies. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3:136–153. doi: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson R.C., Kann M.C., Bailey S.R., Haradhvala N.J., Llopis P.M., Bouffard A.A., Scarfó I., Leick M.B., Grauwet K., Berger T.R., et al. CAR T cell killing requires the IFNgammaR pathway in solid but not liquid tumours. Nature. 2022;604:563–570. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGinnis C.S., Murrow L.M., Gartner Z.J. DoubletFinder: Doublet Detection in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Using Artificial Nearest Neighbors. Cell Syst. 2019;8:329–337.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang H., Wang C., Rubelt F., Scriba T.J., Davis M.M. Analyzing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis immune response by T-cell receptor clustering with GLIPH2 and genome-wide antigen screening. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:1194–1202. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee D.W., Santomasso B.D., Locke F.L., Ghobadi A., Turtle C.J., Brudno J.N., Maus M.V., Park J.H., Mead E., Pavletic S., et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oken M.M., Creech R.H., Tormey D.C., Horton J., Davis T.E., McFadden E.T., Carbone P.P. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sehn L.H., Berry B., Chhanabhai M., Fitzgerald C., Gill K., Hoskins P., Klasa R., Savage K.J., Shenkier T., Sutherland J., et al. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109:1857–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheson B.D., Fisher R.I., Barrington S.F., Cavalli F., Schwartz L.H., Zucca E., Lister T.A., et al. Alliance Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group, European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium. Lymphoma, G., Eastern Cooperative Oncology, G., et Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McInnes L., Healy J., Melville J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arxiv. 2020:0346v3. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1802.03426. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alquicira-Hernandez J., Powell J.E. Nebulosa recovers single cell gene expression signals by kernel density estimation. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:2485–2487. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petti A.A., Williams S.R., Miller C.A., Fiddes I.T., Srivatsan S.N., Chen D.Y., Fronick C.C., Fulton R.S., Church D.M., Ley T.J. A general approach for detecting expressed mutations in AML cells using single cell RNA-sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3660. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11591-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Gene expression matrices have been deposited at GEO and CellXGene, and raw FASTQ files have been deposited in EGA. All data are publicly available as of the date of publication and accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.