Abstract

Additive manufacturing has provided the ability to manufacture complex structures using a wide variety of materials and geometries. Structures such as triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) lattices have been incorporated into products across many fields due to their unique combinations of mechanical, geometric, and physical properties. Yet, the near limitless possibility of combining geometry and material into these lattices leaves much to be discovered. This article provides a dataset of experimentally gathered tensile stress-strain curves and measured porosity values for 389 unique gyroid lattice structures manufactured using vat photopolymerization 3D printing. The lattice samples were printed from one of twenty different photopolymer materials available from either Formlabs, LOCTITE AM, or ETEC that range from strong and brittle to elastic and ductile and were printed on commercially available 3D printers, specifically the Formlabs Form2, Prusa SL1, and ETEC Envision One cDLM Mechanical. The stress-strain curves were recorded with an MTS Criterion C43.504 mechanical testing apparatus and following ASTM standards, and the void fraction or “porosity” of each lattice was measured using a calibrated scale. This data serves as a valuable resource for use in the development of novel printing materials and lattice geometries and provides insight into the influence of photopolymer material properties on the printability, geometric accuracy, and mechanical performance of 3D printed lattice structures. The data described in this article was used to train a machine learning model capable of predicting mechanical properties of 3D printed gyroid lattices based on the base mechanical properties of the printing material and porosity of the lattice in the research article [1].

Keywords: Additive manufacturing, Lattice structures, Machine learning, Mechanics, Porosity, Photopolymer

Specifications Table

| Subject | Materials Science Engineering |

| Specific subject area | Additive Manufacturing; Architected Materials; Vat Photopolymerization; Applied Machine Learning |

| Type of data | .CSV (Force-displacement data for lattice samples) .STL (Lattice sample files) .XLSX (FEA results, Porosity measurements) .PPTX (Material identification table) .M (MATLAB data analysis code) .MAT (MATLAB extracted stress-strain data) |

| How the data were acquired | Gyroid lattice samples were designed with nTopology design software (version 3.17) and were printed using vat photopolymerization 3D printing, specifically the Formlabs Form2 (Preform version 3.22.1), ETEC Envision One cDLM Mechanical (Envision One RP version 1.21.4608), and Prusa SL1 (PrusaSlicer version 2.4.0). Lattice porosity was calculated using mass fraction and a calibrated scale, and samples were tested in tension using an MTS Criterion C43.504 testing machine to gather force-displacement curves. The force-displacement curves were converted to stress-strain curves using sample geometry, and specific mechanical properties were extracted from the curves using a custom MATLAB (version R2022a) script. FEA simulations were performed using Abaqus/Explicit (version 2022) to gather computational stress-strain data. |

| Data format | Raw Analyzed |

| Description of data collection | Samples were fabricated using print and post-processing settings specified by the manufacturer of each material. The lattice portion of each sample was a cylinder with diameter 12 mm and height 17 mm. All tests were performed at room temperature and at a rate of 5 mm/min until a complete fracture of the sample occurred. Force-displacement curves were normalized by sample height and cross-sectional diameter to achieve stress and strain. |

| Data source location |

|

| Data accessibility | Repository name: Mendeley Data Data identification number: 10.17632/wj766p2w9t.1 Direct URL to data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wj766p2w9t |

| Related research article | J. Peloquin, A. Kirillova, C. Rudin, L.C. Brinson, K. Gall, Prediction of tensile performance for 3D printed photopolymer gyroid lattices using structural porosity, base material properties, and machine learning, Mater Des. (2023) 112126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112126. |

Value of the Data

-

•

Experimentally and computationally gathered data in this article provide benchmark datasets for exploring the effects of photopolymer resin material properties and structure porosity on the mechanical performance of 3D printed lattice structures and identifying factors of experimental evaluation that are neglected using computational methods.

-

•

Understanding the relationship between structure, property, and performance of 3D printed lattice structures is invaluable for development of new 3D printing materials, structural lattice design software, and products that incorporate these structures.

-

•

Identification of discrepancies between experimentally and computationally gathered data helps guide modification of existing computational methods to capture printing defects that occur when 3D printing and increase accuracy of computational results.

-

•

The combination of experimental and computational FEA data in this article can help improve accuracy of current FEA methods by identifying how experimental results deviate from the idealized computational results. Furthermore, the dataset can be used for developing machine learning models to optimize lattice structure performance by tuning input material properties and structure geometry.

1. Objective

The objective of this work is to generate experimental and computational datasets to analyze the effects of structure porosity and material properties on the mechanical performance of 3D printed gyroid lattices. Gyroid lattices have been widely incorporated into products and devices across many fields due to their unique geometric, mechanical, and osseointegration properties [2], [3], [4]. By gathering porosity measurements and stress-strain response curves for over 350 unique combinations of material and lattice porosity, the interactions between structure, material, and performance can be investigated for these photopolymer lattices and used to guide future material development or optimize performance. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Peloquin et al. [1], the dataset is sufficiently large to begin training machine learning models for predicting performance of 3D printed lattices based on the material properties of the photopolymers used and the porosities of the gyroid lattices.

2. Data Description

There are seven categories of data within this dataset, namely: (1) three-dimensional mesh geometries of the designed lattice structures (.stl), (2) information on all 20 materials used to print the lattice structures including manufacturers, specific printers used, and the three-letter identifier for each material used to tag the data (.pptx), (3) porosity measurements of all printed samples (.xlsx), (4) raw data files with force & displacement measurements exported from the mechanical testing apparatus (.csv), (5) input parameters and results from finite element analysis for a subset of samples in the dataset (.xlsx), (6) a MATLAB script used to organize the raw mechanical data files, convert to stress and strain, and extract relevant mechanical properties from the stress-strain curves (.m), and (7) the extracted mechanical properties from each sample's stress-strain curve (.mat). Details regarding each of these categories are provided below. For a visual representation of the data workflow in this article, see Fig. 1.

-

(1)

Mesh files for gyroid lattice designs

Fig. 1.

Diagram of data workflow. (A) Samples are designed with Onshape and nTopology computer-aided design software and used to (B) print samples using vat photopolymerization and (D) perform computational finite element analysis simulations. (C) Physical, printed samples are tested in tension using a mechanical testing apparatus, and finally (E) a custom MATLAB script is used to extract mechanical properties from the experimentally and computationally gathered force and displacement data. Adapted from [1].

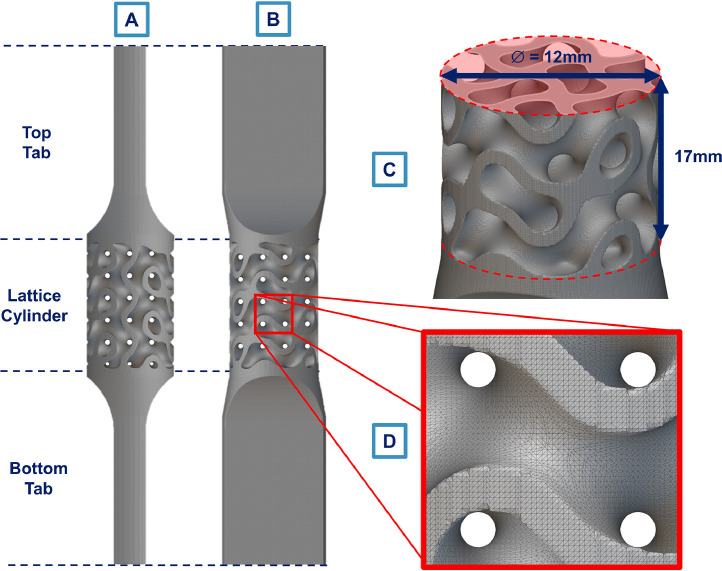

The mesh files used to print the gyroid lattice samples are available in the data repository [5], specifically within the “Lattice Mesh Files” folder. Each file is greater than 70MB in size and provides a high-resolution mesh (Fig. 2D) for accurate 3D printing. Each mesh file contains a lattice with one of seven different porosities (55%, 60%, 65%, 70%, 75%, 80%, or 85%) and is labeled with the respective porosity. The samples consist of a cylindrical gyroid lattice region of diameter 12mm and height 17mm (Fig. 2C), and solid tabs added to the top and bottom of the cylinder for interfacing with the mechanical testing apparatus (Figs. 2A, B).

-

(2)

Photopolymer material information

Fig. 2.

Visual representation of a gyroid lattice sample viewed from the (A) front and (B) side. The sample is separated into three sections: a top tab, a bottom tab, and a cylinder where the lattice is applied. (C) The cylindrical section has a diameter of 12mm and height of 17mm. (D) The files used for 3D printing and FEA simulations are exported with a high degree of resolution, specified by a “Tolerance” of 0.2mm in the nTopology design software.

The names, viscosities, and manufacturers for each of the 20 photopolymer resins used are available in a table within [5] titled “Mateirals_table.pptx”. The table also identifies which printer was used to print each material and the three-letter identifier for each material. This identifier is used to shorten the length of filenames and data variables and is used as the first three letters of each raw data file. Finally, the “M” values used to identify materials during the machine learning process in [1] are also included.

-

(3)

Lattice porosity measurements

Porosity measurements are contained in “Porosity_data.xlsx” within the data repository [5]. The designed porosity (i.e., the porosity of the mesh file) and the measured porosity for each sample are listed. All porosity values listed are in units of percent void, where 100% porosity would correspond to zero mass and 0% porosity would correspond to a solid cylinder.

-

(4)

Raw mechanical data files

The raw data file for each tested sample is contained within the “Raw Mechanical Data” folder in the data repository [5]. The raw data files contain the name of the sample, the date that the sample was tested, and the crosshead position, load cell reading, and time recordings during the testing period. The crosshead position, load, and time all begin at “0” without an initial offset. The crosshead position has units of millimeters and the load cell records force in units of Newtons, so converting to stress and strain requires dividing the position by the height of the lattice cylinder and dividing the force by the cross-sectional area of the lattice cylinder, respectively.

-

(5)

Finite element analysis data

Finite element analysis (FEA) simulations were performed on a subset of the dataset to determine the mechanical response of the samples computationally and are available in the “FEA_data.xlsx” file within the dataset [5]. The FEA simulation results were compared to machine learning predictions in [1] to determine the differences in accuracy and computational time between the two. For this comparison, only a subset of the entire experimental dataset was used (see [1] for selection and justification of samples). The file contains data from the convergence study that was performed to determine an appropriate finite element mesh resolution, the mesh and simulation times for each sample, the material properties used as input for each sample, the tabulated force-displacement results for each sample, and visual plots of all simulation results.

-

(6)

MATLAB script

A custom MATLAB script, available in the “MATLAB” folder within [5] and labeled “Matlab_data_organizer.m”, was used to convert experimentally gathered force-displacement data into stress-strain data and extract relevant mechanical properties from the stress-strain curves. The script contains several cells that go step-by-step through the data extraction process. First, force and displacement data are extracted from the individual raw data files and compiled into a single .csv document containing the names and porosity measurements for each sample. The document is then imported into MATLAB, and the force-displacement curves are displayed one at a time as MATLAB figures. When a force-displacement curve shows up, the user clicks on the starting point, yield point, and fracture point of the curve. Using sample geometry data from the document, force and displacement are converted to stress and strain, respectively, and various mechanical properties including Young's modulus, yield strength, and fracture strain are automatically calculated and stored in a data structure. Once the user presses the “Enter” button, the next sample force-displacement curve is automatically plotted in the figure.

-

(7)

MATLAB stress and strain data

The stress-strain curves and mechanical property values extracted from the samples using the custom MATLAB script are stored in MATLAB data structures available in the “MATLAB” folder within [5] and labeled “Matlab_data.mat”. Each sample is given a field within the data structure, and the elements of the field contain all raw and extracted data for each sample. Thus, the structure contains 389 fields, each containing data for one of the experimentally tested gyroid lattice samples.

3. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

-

(1)

Design of samples

The samples were designed using the Onshape and nTopology design software packages. The samples were modeled as solid cylinders with solid tabs on the top and bottom in Onshape, exported at .STEP files, and then imported into nTopology to apply the gyroid lattice. The gyroid lattice was created using the “Rectangular Volume Lattice” block in nTopology. The “gyroid” TPMS unit cell was selected and a unit cell size of 6 × 6 × 6mm was specified. To achieve the desired range of lattice porosities, the wall thickness of the lattice structure was modified to change the porosity of the sample. For porosities of 55, 60, 65, 70, 75, 80, and 85% the wall thicknesses used were 1.390, 1.240, 1.090, 0.936, 0.782, 0.628, and 0.471, respectively (Fig. 1A). A “Boolean Union” was used to combine the now lattice-filled cylinder with the top and bottom solid tabs, and the combined part was exported as a .STL file using the “Mesh from Implicit Body” block and a tolerance of 0.2mm.

-

(2)

Printing samples

All samples were printed using vat photopolymerization 3D printing technology (Fig. 1B). Specifically, all samples using Formlabs materials were printed with a Formlabs Form2, samples printed using ETEC materials were printed with an ETEC Envision One cDLM Mechanical, and samples printed using LOCTITE AM materials were printed with a Prusa SL1 (see “Materials_table.pptx” in [5] for detailed material information). Samples were printed using the Preform, Envision One RP, and PrusaSlicer 3D printing software packages, and print settings were assigned as per manufacturer presets (Formlabs and ETEC) or recommended settings (LOCTITE AM) for the given printing material. The lattice dogbone samples were printed with their longest dimension oriented orthogonal to the build platform and with the bottom tab directly on the build plate. No support was used for printing any of the samples. All samples were post-processed, including isopropanol wash and UV cure, as per the material manufacturer's recommended settings for the specific material. Once printed and post-processed, samples were allowed to dry fully, placed in plastic sample bags, and stored in a dark, enclosed drawer. Porosity measurements and mechanical testing occurred within one week of printing for all samples.

-

(3)

Porosity measurements

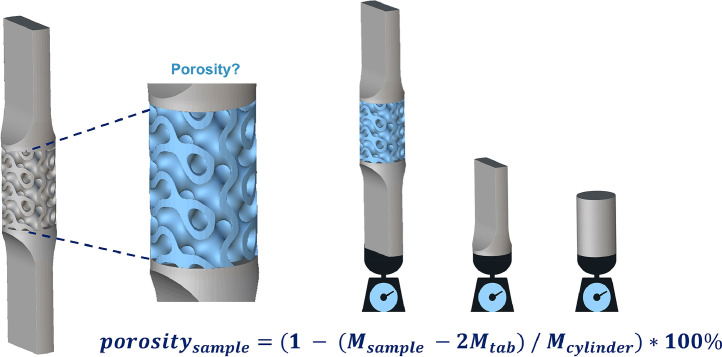

During the printing process, additional parts were printed to assist in calculating the porosity of printed samples. Three duplicate solid cylinders and solid tabs for each material were printed on the same build plate as the lattice samples (Fig. 3). After printing and post-processing, the mass of each printed lattice sample, cylinder, and tab was recorded using a calibrated electronic weighing machine (VWR1233). The average masses for the duplicate cylinders and tabs were calculated and using these values together with the mass of each lattice sample, the equation in Fig. 3 was used to calculate the porosity of each lattice as a percentage out of 100%.

-

(4)

Mechanical tensile testing

Fig. 3.

Process for calculating the porosity of physically printed samples. The entire lattice sample, including the top and bottoms tabs, is printed and then weighed using an electronic scale. Additionally, isolated tabs and solid cylinders are printed and weighed. Using these measured mass values, the porosity of the lattice portion is calculated by subtracting the mass of the tabs from the entire sample to achieve the mass of the lattice portion only. Then, the mass of the lattice portion is divided by the mass of the solid cylinder, subtracted from 1, and multiplied by 100% to produce the porosity.

All samples were tested in tension using an MTS Criterion C43.504 electronic testing apparatus (Fig. 1C). The samples were placed in the testing apparatus such that each flat face on the top and bottom samples tabs was in total contact with the grips. Testing was performed following the ASTM D638 standard at a displacement rate of 5mm/min until total fracture of the sample occurred and the load cell measured a force of 0 Newtons.

-

(5)

Finite element analysis simulations

FEA simulations were performed using the Abaqus software suite from Dassault Systèmes (Fig. 1D). The Abaqus/Standard solver was selected over Abaqus/Explicit due to the relatively slow test rate used and resulting lack of high-speed dynamic events. All simulations were run to a total displacement of 2mm or approximately 8% strain to capture the entire linear regime of the stress-strain curve. A convergence study was performed to determine the necessary number of elements for the finite element mesh to achieve repeatable simulation results. The subset of sample data used to gather FEA results included four materials (GPR, HEC, HIC, HTB) and three porosity values (55, 70, 85%), resulting in a total of 12 simulations (To match material identifiers to the photopolymer material used, see “Materials_table.pptx” in [5]).

-

(6)

Data extraction

A custom MATLAB script was used to convert force-displacement data from the experimental testing and computational simulations into stress-strain values and extract mechanical properties of interest. The script first imports force and displacement data from raw data files and compiles the displacement and force vector for each sample into a matrix. This matrix is then exported to a Microsoft Excel workbook that contains the names, dimensions, designed porosities, and measured porosities for all samples (for computational results, no measured porosity values are used). This workbook is then imported into MATLAB, and a figure is populated with the force-displacement curve of the first sample in the dataset. Next, the user selects three points on the curve by clicking with the mouse button: 1) Starting position, 2) yield point, and 3) fracture point. Then, using the sample geometry and selected points on the curve, the script automatically converts the force-displacement curve to a stress-strain curve and calculates mechanical properties such as Young's modulus, yield strength, and fracture strain (Fig. 1E). The stress-strain curve data and mechanical properties are stored to a MATLAB structure with each field corresponding to one of the samples.

Ethics Statements

The authors adhered to the ELSEVIER ‘Ethics in publishing’ policy and no ethical issues are associated with this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jacob Peloquin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Validation. Alina Kirillova: Methodology, Data curation. Elizabeth Mathey: Data curation, Methodology, Software. Cynthia Rudin: Conceptualization, Supervision. L. Catherine Brinson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. Ken Gall: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

• Jacob Peloquin reports financial support was provided by National Science Foundation.

• L. Catherine Brinson reports financial support was provided by National Science Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation [DGE-2022040] and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. The authors also acknowledge support from the NSF aiM-NRT Research Traineeship program.

Data Availability

References

- 1.Peloquin J., Kirillova A., Rudin C., Brinson L.C., Gall K. Prediction of tensile performance for 3D printed photopolymer gyroid lattices using structural porosity, base material properties, and machine learning. Mater. Des. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly C.N., Lin A.S., Leguineche K.E., Shekhar S., Walsh W.R., Guldberg R.E., Gall K. Functional repair of critically sized femoral defects treated with bioinspired titanium gyroid-sheet scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo J.W., Chen L., Min T., Shan F., Kang Q., Tao W.Q. Macroscopic transport properties of Gyroid structures based on pore-scale studies: permeability, diffusivity and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020;146 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.118837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali D., Sen S. Finite element analysis of mechanical behavior, permeability and fluid induced wall shear stress of high porosity scaffolds with gyroid and lattice-based architectures. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017;75:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peloquin J. Tensile performance data of 3D printed photopolymer gyroid lattices created using a range of base materials and lattice porosities. Mendeley Data. 2023;v1 doi: 10.17632/wj766p2w9t.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.