Abstract

Diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) is a putative second messenger molecule that is conserved from bacteria to man. Nevertheless, its physiological role, and the underlying molecular mechanisms, are poorly characterized. We investigated the molecular mechanism by which Ap4A regulates inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH, a key branching point enzyme for the biosynthesis of adenosine or guanosine nucleotides) in Bacillus subtilis. We solved the crystal structure of BsIMPDH bound to Ap4A at a resolution of 2.45 Å to show that Ap4A binds to the interface between two IMPDH subunits, acting as the glue that switches active IMPDH tetramers into less active octamers. Guided by these insights, we engineered mutant strains of B. subtilis that bypass Ap4A-dependent IMPDH regulation without perturbing intracellular Ap4A pools themselves. We used metabolomics suggesting that these mutants have a dysregulated purine, and in particular GTP, metabolome and phenotypic analysis showing increased sensitivity of B. subtilis IMPDH mutant strains to heat compared with wildtype. Our study identifies a central role for IMPDH in remodelling metabolism and heat resistance, and provides evidence that Ap4A can function as an alarmone.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleotide-based second messengers, e.g., (p)ppGpp1,2, c-di-GMP,3,4 or c-di-AMP5, are essential for bacterial responses to changing environmental and stress conditions. Diadenosine polyphosphate molecules such as diadenosine 5’,5’’’-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (Ap4A) have been known since the 1960’s6 and are found in all domains of life7. Ongoing debate is whether they are damage metabolites8 or bona fide second messengers7.

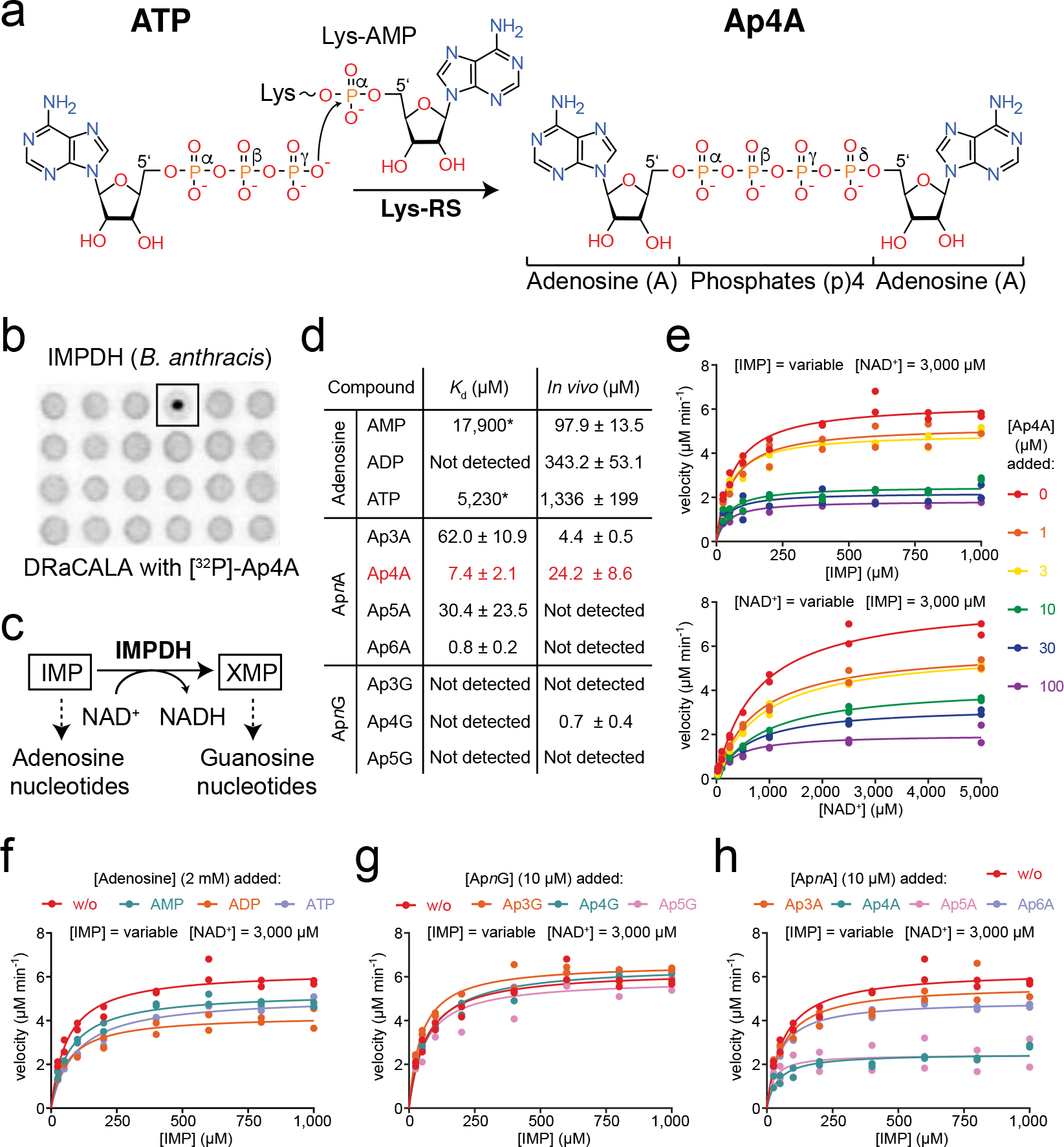

Ap4A is comprised of two adenosines bridged at their 5’ ends by four phosphates (Fig. 1a). It is primarily produced by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, with lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) being a prominent example, under heat shock and oxidative stress conditions through the transfer of the aminoacylated AMP onto the 5’ γ-phosphate of ATP 6,9–11. The promiscuous utilization of other aminoacyl-AMP acceptors by LysRS, such as ADP, GDP or GTP leading to the synthesis of the even more enigmatic Ap3A, Ap3G and Ap4G, respectively, broadens the spectrum of dinucleoside polyphosphate molecules10.

Fig. 1. Ap4A inhibits IMPDH in a non-competitive manner.

a. Scheme of Ap4A formation by lysyl-tRNA synthetase (Lys-RS) from ATP and lysyl-AMP (Lys-AMP). b. DRaCALA assay with 32P-labelled Ap4A employing a B. anthracis library suggests IMPDH as a target of Ap4A. c. Scheme of the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by IMPDH, the NAD+-dependent conversion of IMP into XMP, which represent the starting points in the de novo biosynthesis of adenosine and guanosine nucleotides, respectively. d. Binding of adenosine nucleotides, and ApnA and ApnG dinucleotides (n = variable number of phosphates) to BsIMPDH determined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and their intracellular concentrations determined by LC-MS. Asterisks denote bad binding curve fitting. LC-MS data represent the mean ± SD of n=3 biological replicates. The error of the Kd derived from ITC data represents unambiguity in the curve fitting. e-h. Enzyme-kinetic behavior of BsIMPDH for its conversion of the IMP substrate into XMP in dependence of e. Ap4A, f. adenosine nucleotides, g. ApnG dinucleotides, and h. ApnA dinucleotides. Individual data points of n=2 technical replicates are shown, and parameters of the fits are given in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Several studies have reported pleiotropic roles for Ap4A in bacteria. In Escherichia coli Ap4A has been implicated in cell division12, motility13 and responses to heat/oxidative stress14 and aminoglycoside antibiotics15. Ap4A has been associated with sporulation in Myxococcus xanthus16, heat shock, ethanol stress, and cell oxidation in Salmonella typhimurium10, biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa17, and survival of Helicobacter pylori in response to oxidative stress18.

Our knowledge about Ap4A-binding partners in bacteria and a mere understanding of the mechanisms by which Ap4A regulates these is currently limited to E. coli8,14,19,20. Proposed targets include the chaperones DnaK, ClpB and GroEL14,21 and the de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis enzyme inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH)8,19. These screens employed biotin and/or aziridine-modified Ap4A to enrich Ap4A-binding proteins, which potentially may have biased the target spectrum due to the size of the modifier groups.

RESULTS

Identification of Ap4A targets in Bacillus anthracis.

To identify further Ap4A targets in unbiased manner, we used a radioactively-labelled but otherwise chemically unmodified Ap4A as bait in a differential radial capillary action of ligand assay (DRaCALA) assay22. Simultaneously, we aimed to expand knowledge on Ap4A regulation to the Firmicutes phylum. Having a library for all Bacillus anthracis proteins available, we screened for Ap4A-binding targets in this organism and then continued our mechanistic and physiological analyses in Bacillus subtilis. We employed two B. anthracis overexpression libraries, each including 5,341 open reading frames (ORFs) N-terminally fused to either hexa-histidine (His) or His-maltose binding protein (His-MBP)23. Both libraries were overexpressed in E. coli, and the binding of radio-labelled [32P]-Ap4A to the lysates assayed by DRaCALA22. This screen identified inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH, gene: guaB) as putative Ap4A-binding partner (Fig. 1b).

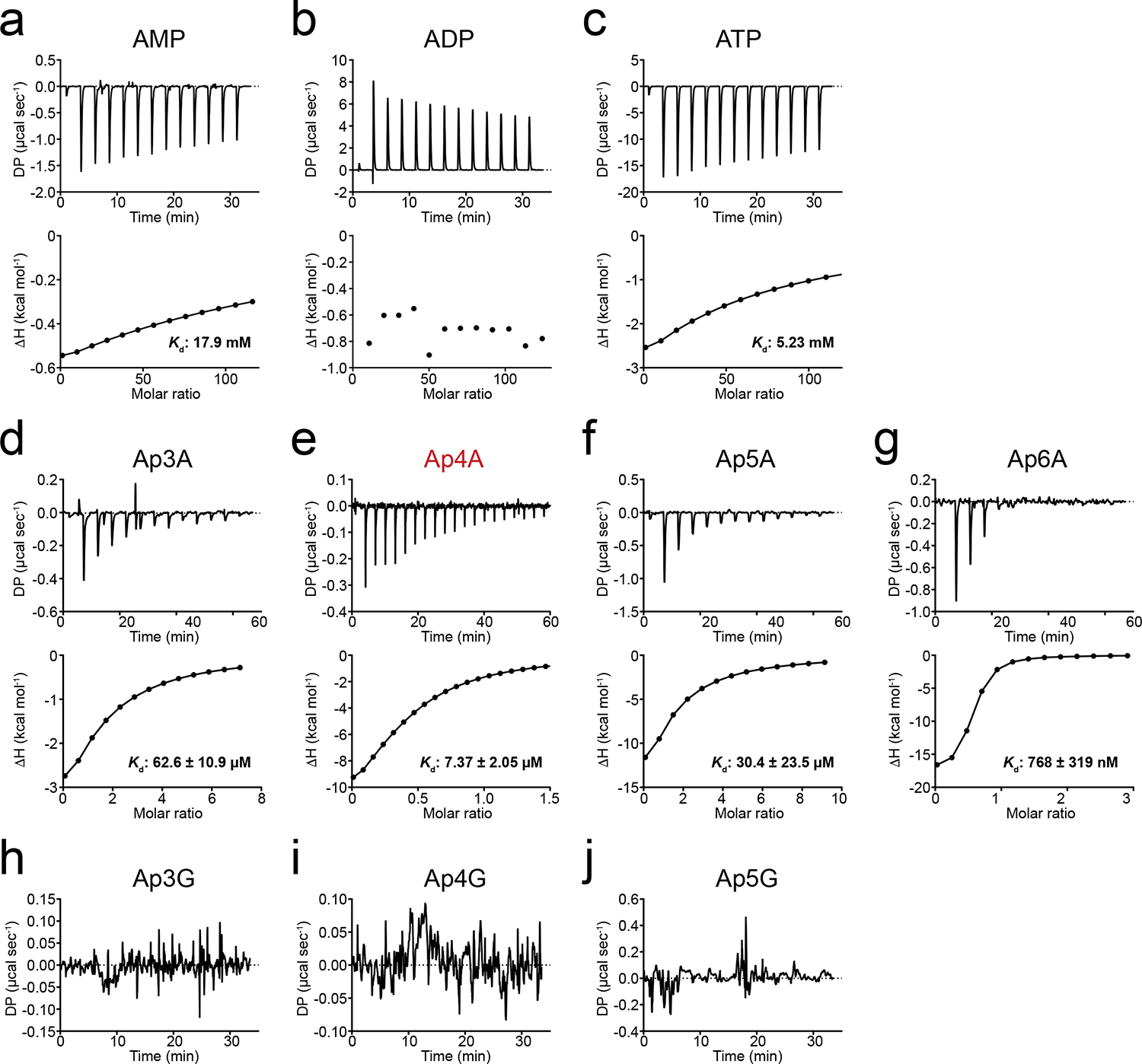

IMPDH catalyzes the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent conversion of inosine-5’-monophosphate (IMP) into xanthosine-5’-monophosphate (XMP)24. XMP represents the start for the generation of GMP, GDP, and GTP. Moreover, IMPDH represents the branching point in the biosynthesis of adenosine and guanosine nucleotides (Fig. 1c). To further probe the Ap4A-IMPDH interaction, we investigated IMPDH from B. subtilis (Bs), because this bacterium is broadly studied and a close relative of B. anthracis. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) revealed a dissociation constant (Kd) of 7.4 ± 2.1 μM for the Ap4A-BsIMPDH interaction (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1e). This Kd is within the range of Ap4A concentration determined by LC-MS for exponentially growing B. subtilis (Fig. 1d). We also tested the binding of the adenosine nucleotides AMP, ADP, and ATP to BsIMPDH due to their structural similarity to Ap4A and because an ATP-dependent stimulation of IMPDH activity in P. aeruginosa (Pa) was reported25. Binding of AMP and ATP to BsIMPDH proceeds with low affinity evidenced by Kd values of approximately 18 and 5 mM, respectively. No interaction was found for ADP (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Figs. 1a–c). Furthermore, we tested the specificity of BsIMPDH for the nucleobases linked by the phosphates in the dinucleotides and the length of this phosphate linker by probing the binding of ApnA and ApnG compounds. ApnA dinucleotides Ap3A, Ap5A, and Ap6A bound to BsIMPDH with Kd’s of 62.0 ± 10.9 μM, 30.4 ± 23.5 μM and 0.8 ± 0.2 μM, respectively (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Figs. 1d, f, g). No binding was found for the ApnG dinucleotides Ap3G, Ap4G, and Ap5G (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Figs. 1h–j). Collectively, BsIMPDH had a strong preference (≥100-fold higher affinity) for ApnA dinucleotides with varying phosphor-linker lengths over the related adenosine mononucleotides.

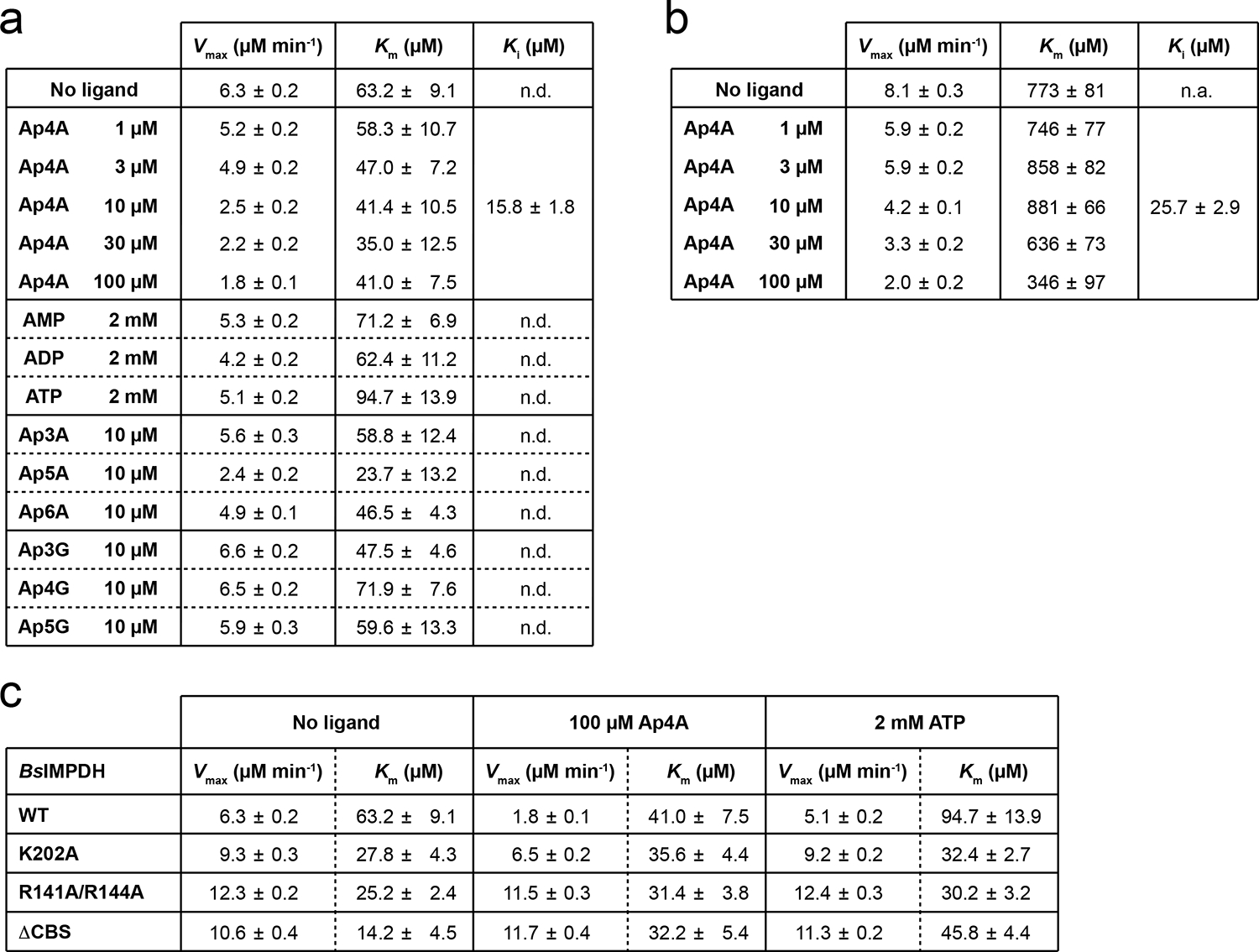

Ap4A is a non-competitive inhibitor of IMPDH.

Next, we probed whether Ap4A and ApnA would affect IMPDH activity by an assay based on the reduction of the NAD+ cofactor to NADH detectable at a wavelength of 340 nm. At constant saturating NAD+ and variable IMP concentrations without Ap4A supplemented, BsIMPDH showed a Michaelis-Menten-like kinetic behavior, with maximal velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) values of 6.3 μM min−1 and 63 μM, respectively (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 2a). With increasing Ap4A concentration, Vmax decreased while Km remained unaltered, suggesting an allosteric mode of inhibition. BsIMPDH inhibition by Ap4A proceeded with an inhibitory constant (Ki) of 15.8 μM roughly reflecting the Kd between Ap4A and BsIMPDH (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 2a). At constant saturating IMP and variable NAD+ concentrations BsIMPDH activity showed a similar decline of Vmax dependent on increasing Ap4A concentrations (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 2b). In contrast to Ap4A, which potently reduced BsIMPDH activity, adenosine mononucleotides only moderately inhibited BsIMPDH (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2a). ApnG dinucleotides did not alleviate BsIMPDH activity and out of the ApnA dinucleotides tested by us, only Ap5A and Ap6A resulted in BsIMPDH inhibition (Figs. 1g, h, Extended Data Fig. 2a). Despite Ap5A and Ap6A being the most potent inhibitors of BsIMPDH, we focused our further studies on Ap4A because it was more abundant than other dinucleotides in B. subtilis in vivo (Fig. 1d). Likewise, Ap4A was approximately 3-fold more abundant than Ap5A under various stress conditions and throughout growth in M. xanthus16. Collectively, our data show that Ap4A inhibits IMPDH in vitro at concentrations that roughly match those present in vivo.

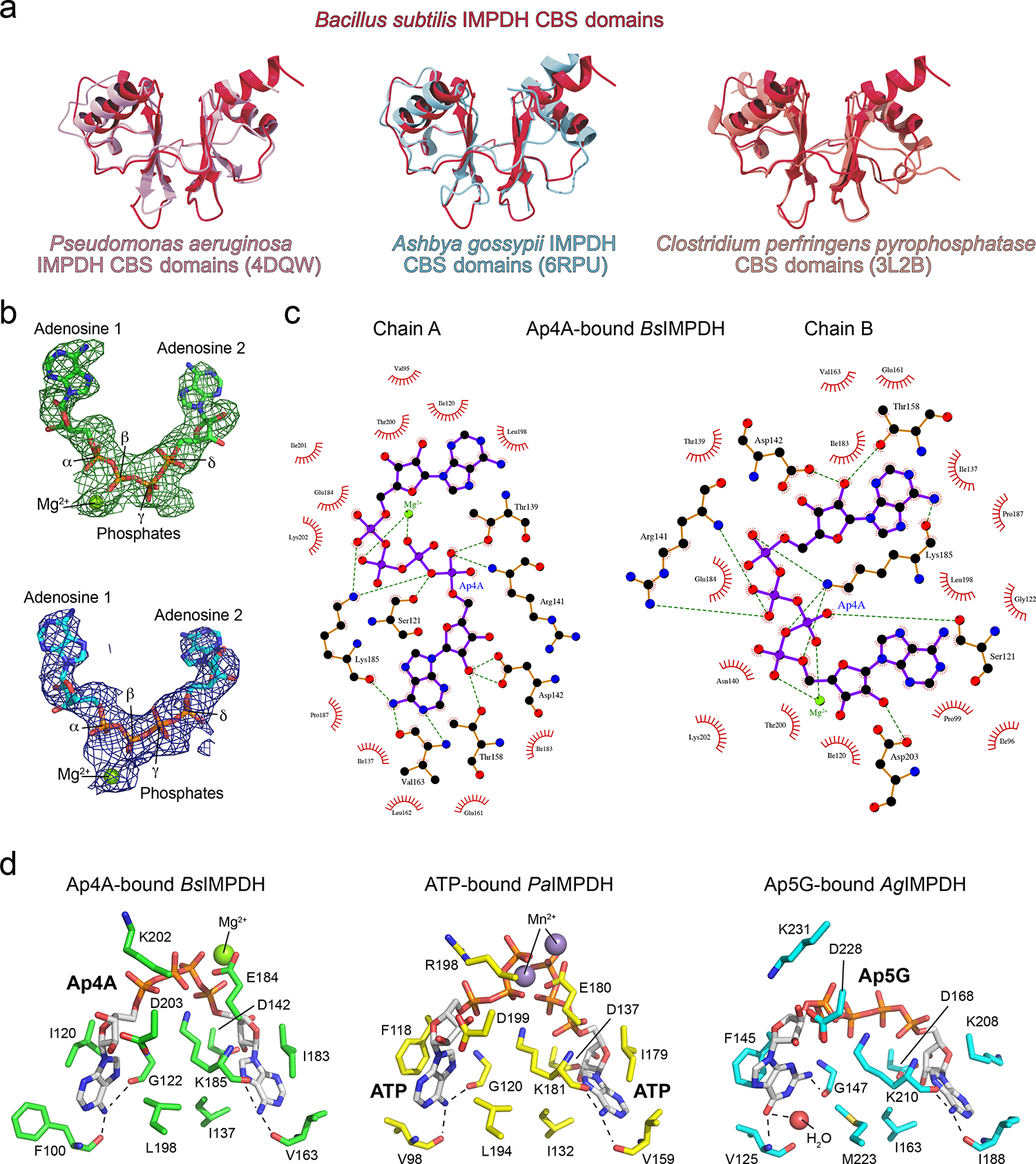

Ap4A binds to the CBS domains of IMPDH.

Next, we determined the structure of Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH (Table 1). BsIMPDH consists of the catalytic triose isomerase (TIM)-barrel with two cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) domains forming the disc-like Bateman module inserted into the TIM-barrel (Figs. 2a, b, c, Extended Data Fig. 3a). Four IMPDH molecules form a tetramer through their catalytic domains with each CBS domain pointing outward from the center of the tetramer (Fig. 2b). Electron density, which could be unambiguously attributed to Ap4A, was present in between the two CBS domains of each IMPDH monomer (Extended Data Fig. 3b). It binds into a cleft formed by the two CBS domains constituting the Bateman module (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 3c). Binding of Ap4A to BsIMPDH closely resembles that of Ap5G bound to A. gossypii IMPDH26 as well as that of the adenosine nucleoside moieties of two ATP molecules bound to P. aeruginosa IMPDH25 (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

Table 1.

| Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH |

BsIMPDH-ΔCBS | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | I4 | I422 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 133.75 133.75 149.68 |

110.91 110.91 156.85 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90 | 90 |

| 90 90 |

90 90 |

|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.978561 | 0.918400 |

| Resolution (Å) | 66.88 – 2.442 (2.53 – 2.442) |

45.28 – 1.76 (1.823–1.76) |

| Rmerge | 0.067 (0.2841) | 0.03072 (0.2892) |

| I / σI | 6.55 (2.58) | 13.79 (2.43) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.58 (99.82) | 99.95 (100.00) |

| Redundancy | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| CC1/2 | 0.992 (0.641) | 0.999 (0.708) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 66.88 – 2.442 | 45.28 – 1.76 |

| No. reflections | 48533 (4865) | 48580 (4794) |

| Rwork / Rfree | 0.27/0.29 | 0.17/0.19 |

| No. atoms | 6255 | 2868 |

| Protein | 6112 | 2868 |

| Ligand/ion | 108 | 17 |

| Water | 35 | 200 |

| B-factors | 71.44 | 29.89 |

| Protein | 70.65 | 29.45 |

| Ligand/ion | 120.22 | 36.30 |

| Water | 58.99 | 35.20 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.02 | 1.78 |

| Ramachandran | ||

| Favored (%) | 95.01 | 97.98 |

| Allowed (%) | 4.37 | 2.02 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.62 | 0.00 |

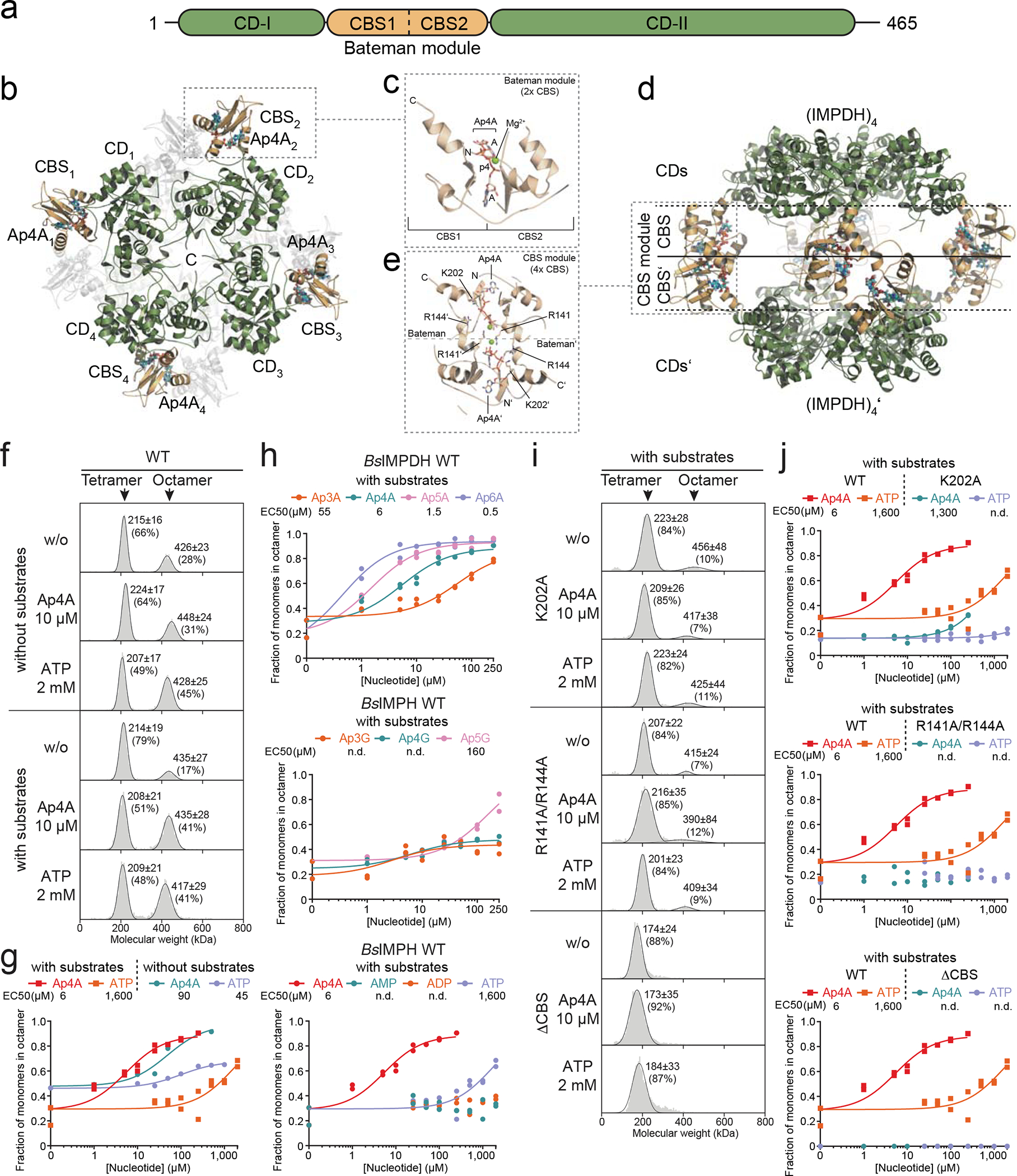

Fig. 2. Mechanism of the Ap4A-dependent inhibition of IMPDH.

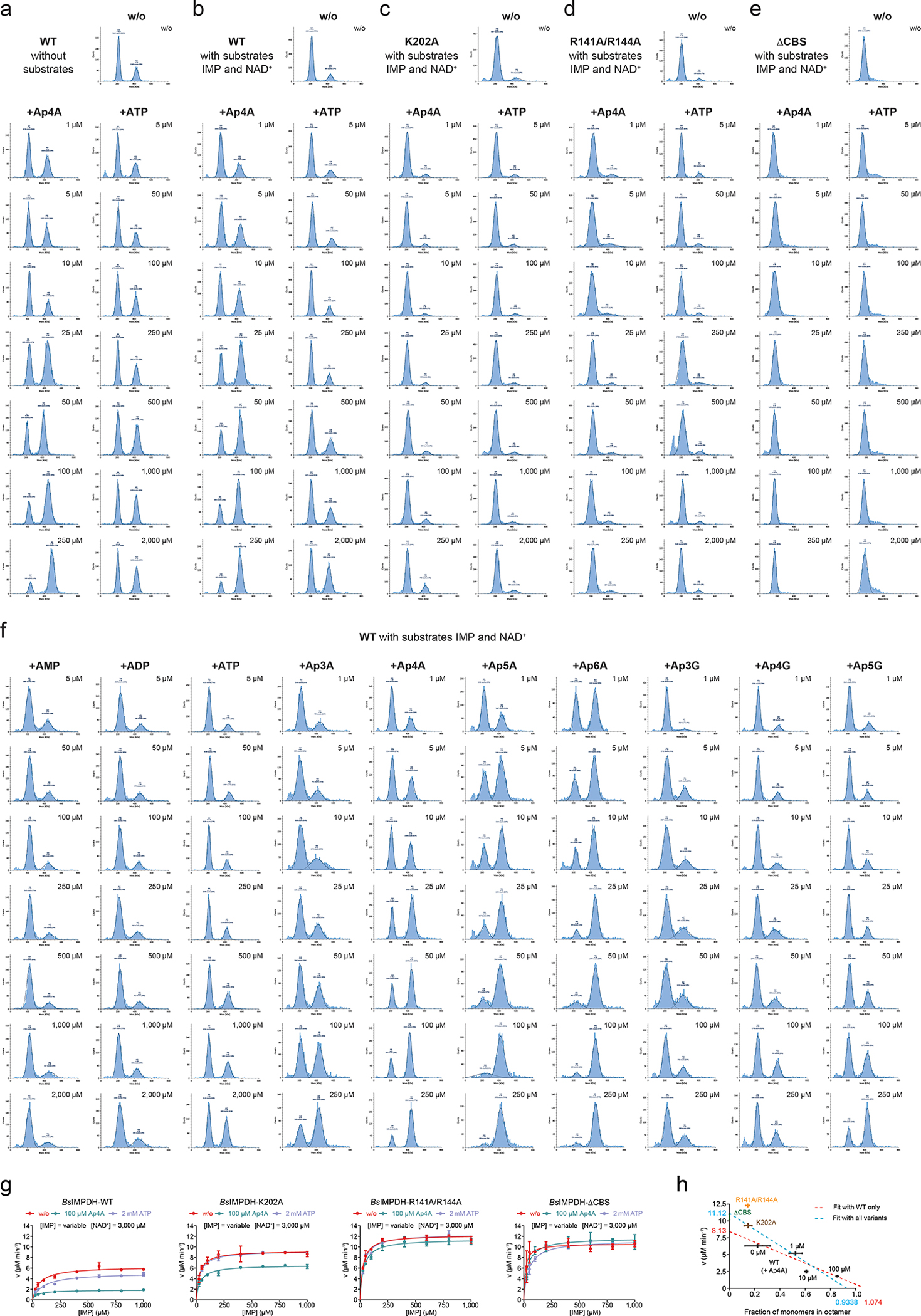

a. Domain organization of IMPDH enzymes. The CBS domains forming a Bateman module (orange) are inserted into the catalytic domain (CD, green). b. Top view on the IMPDH structure bound to Ap4A, which binds into the CBS domains of the IMPDH oligomer. c. Close-up showing that Ap4A binds in a horseshoe-like manner into a cavity formed by the two CBS domains (Bateman module) of an IMPDH monomer. d. Side view on the Ap4A-dependent IMPDH octamer showing that two tetramers of IMPDH form an octamer via their CBS domains. e. Close-up view onto a CBS module established by two IMPDH monomers belonging to different tetrameric rings. The interaction of the Bateman modules is mainly enforced by interactions between R141 and R144 residues of one monomer with the Ap4A bound in the Bateman module of the opposing monomer. f-i. Influence of substrates and ligands on the oligomeric state of BsIMPDH (tetramer or octamer) analyzed by mass photometry. f, i. Representative distributions of tetrameric and octameric BsIMPDH species for f. BsIMPDH-WT, or i. BsIMPDH CBS domain variants (K202A, R141A/R144A, ΔCBS), in dependence of substrates and/or ligands to the sample. Numbers in the diagrams reflect the molecular weight of the observed oligomeric species (mean ± SD) and their percentage of all observed molecules in the sample. g, h, j. The fraction of BsIMPDH monomers in the octameric state in absence or presence of substrates displayed as a function of nucleotide or dinucleotide concentration. Individual data points of n=2 technical replicates are displayed, and their means used for curve-fitting. Where possible, EC50 values (in μM) were derived from the dose-response curves.

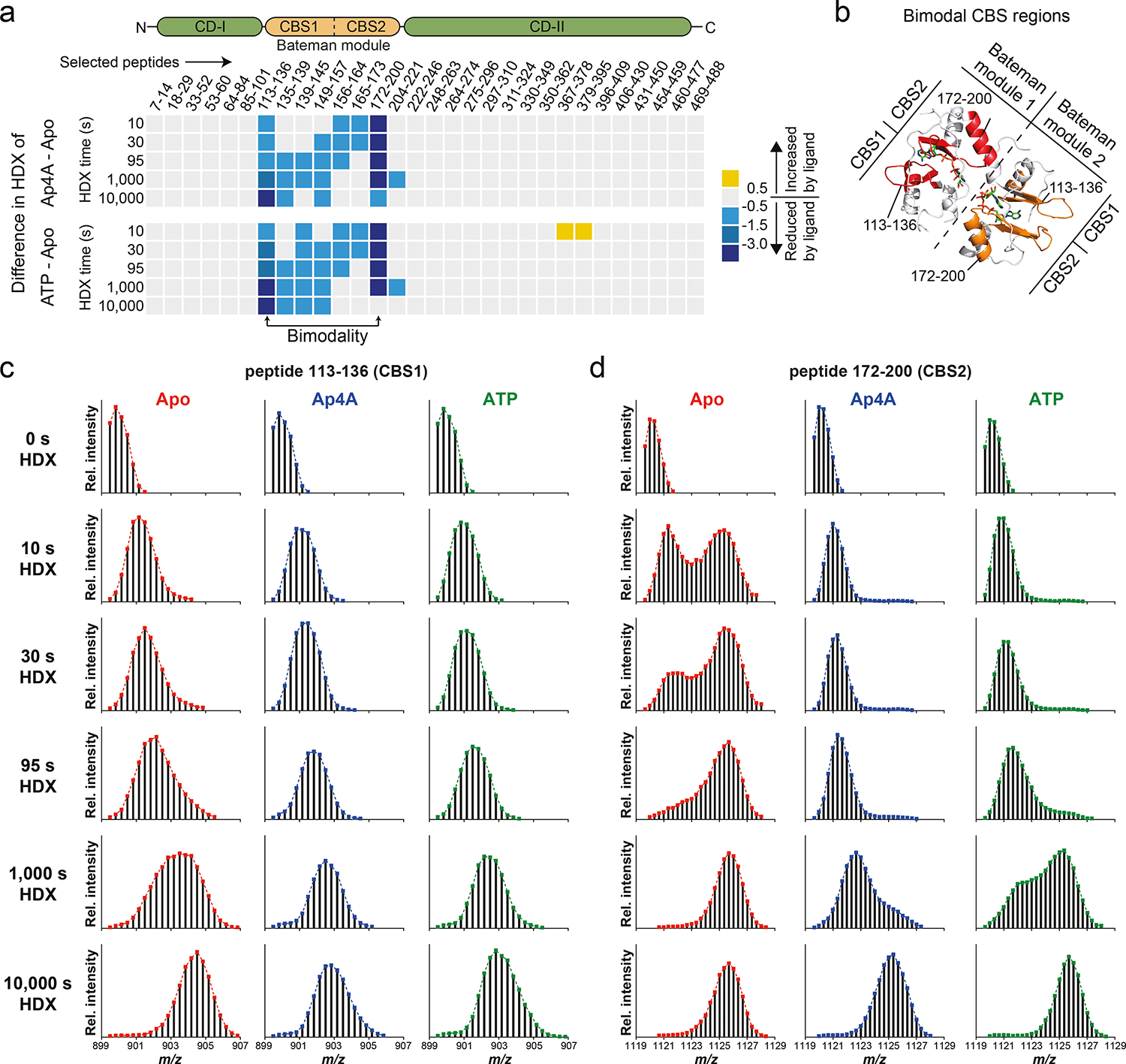

The crystal structures of the IMPDH Apo states from B. anthracis, P. aeruginosa, and A. gossypii show a high degree of disorder in their CBS domains, which diminishes in the presence of a ligand (Extended Data Fig. 4). Thus, we probed the impact of Ap4A and ATP (as control) on the conformational flexibility of BsIMPDH by hydrogen/deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (HDX-MS). Decrease in HDX with either ligand was exclusively present in the CBS domains substantiating binding to this entity (Extended Data Fig. 5a). The progression of HDX in peptides from the CBS1 (residues 113–136) and CBS2 (residues 172–200) domains of the Bateman module evidenced bimodal distributions of deuterated peptide ions (Extended Data Figs. 5b–d), which are thought to arise from partial unfolding or conformational flexibility27,28. Bimodal behavior is less pronounced in the presence of Ap4A and ATP suggesting ligand-induced rigidification of the CBS domains. Thus, Ap4A and ATP restrict the conformational flexibility of the CBS domains of IMPDH.

Ap4A induces formation of a less active IMPDH octamer.

Bacterial IMPDH enzymes are grouped into classes I and II depending on their oligomeric states and catalytic properties29. Class I enzymes (e.g. PaIMPDH) are octameric irrespective of their bound ligand, exhibit comparably low but positive cooperative enzymatic activity, and increased catalytic efficiency accompanied by loss of cooperativity when ATP is present25. Class II enzymes (e.g., BsIMPDH) can be tetrameric (apo or IMP-bound) or octameric (NAD+ or ATP-bound). Both states show Michaelis-Menten-like kinetic properties29. Our biochemical experiments revealed that Ap4A and ATP, albeit binding with approximately 700-fold different affinity, share their interaction site in the CBS domains and similarly restrict its conformational flexibility. Thus, both ligands may affect the tetramer/octamer equilibrium of BsIMPDH. If true, this also raises the question as to why Ap4A strongly restricts the enzymatic activity of BsIMPDH while ATP does so only moderately, if at all (Fig. 1f).

Analysis of the crystal structure of Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH suggests that two IMPDH tetramers engage into an octamer through their Ap4A-bound CBS domains (Fig. 2d). This BsIMPDH octamer is stabilized by the arginines 141 and 144 of the CBS domains of one tetramer, which interact with the phosphates of the Ap4A molecules of the other tetramer, and vice versa (Fig. 2e). Thus, our structure suggests that Ap4A promotes the joining of two BsIMPDH tetramers via their CBS domains into an octamer.

Next, we employed mass photometry, which enables direct mass determination of single molecules in solution by interferometric scattering microscopy30. In the absence of substrates, BsIMPDH predominantly appeared as tetramer, the portion of which is further enlarged in the presence of NAD+ and IMP (Figs. 2f, 2g). Ap4A promoted formation of BsIMPDH octamers in a dose-dependent manner with EC50 values of 90 μM and 6 μM in absence and presence of substrates, respectively (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Figs. 6a, 6b). The addition of ATP enforced octamer formation with comparable EC50 in the absence (i.e., 45 μM ATP) but with a roughly 250-fold higher EC50 than that exhibited by Ap4A in the presence of substrates (Fig. 2g), in agreement with the higher inhibitory potence of Ap4A for BsIMPDH activity (Figs. 1f, h). We presume that the discrepancies in EC50 related to the presence of substrate are a consequence of their impact on the oligomerization state of the enzyme29. The observed fraction of BsIMPDH octamers induced by other ApnA and ApnG dinucleotides and adenosine mononucleotides (Fig. 2h, Extended Data Fig. 6f) correlated well with their impact on enzymatic activity (Figs. 1f–h).

Guided by the structure (Fig. 2e), we conceived several variants that should not bind Ap4A anymore, i.e., K202A, R141A/R144A, and ΔCBS, in which the CBS domains from residues Val95 to Ile 208 were replaced by a Ser-Gly-Ser linker. The K202A variant was still able to octamerize in dependence on Ap4A albeit higher concentrations were required (Fig. 2i, Extended Data Fig. 6c), and showed a modest Ap4A-dependent reduction in activity (Extended Data Figs. 2c, 6g). The R141A/R144A and ΔCBS variants were insensitive to Ap4A-dependent regulation in enzymatic activity (Extended Data Figs. 2c, 6a) and tetramer-to-octamer equilibrium (Fig. 2i, Extended Data Figs. 6d, 6e). The ΔCBS variants exhibited a higher Vmax of enzymatic activity than the wildtype (Extended Data Figs. 2c, 6g). Plotting the fraction of active sites residing in the octameric form versus the Vmax yielded a reasonable correlation, implying that the BsIMPDH tetramer would exhibit a roughly 10-fold higher activity than the octamer (Extended Data Fig. 6h). Collectively, these data indicate that the promotion of BsIMPDH octamers, which are enzymatically less active than the tetrameric form, represents the underlying mechanistic principle of Ap4A-dependent inhibition of BsIMPDH activity. Of note, all assays were conducted at 25 °C for technical reasons instead of, e.g., 51 °C (B. subtilis heat shock temperature, see below). Nevertheless, we expect that these in vitro characteristics of IMPDH would also apply to the enzyme in vivo.

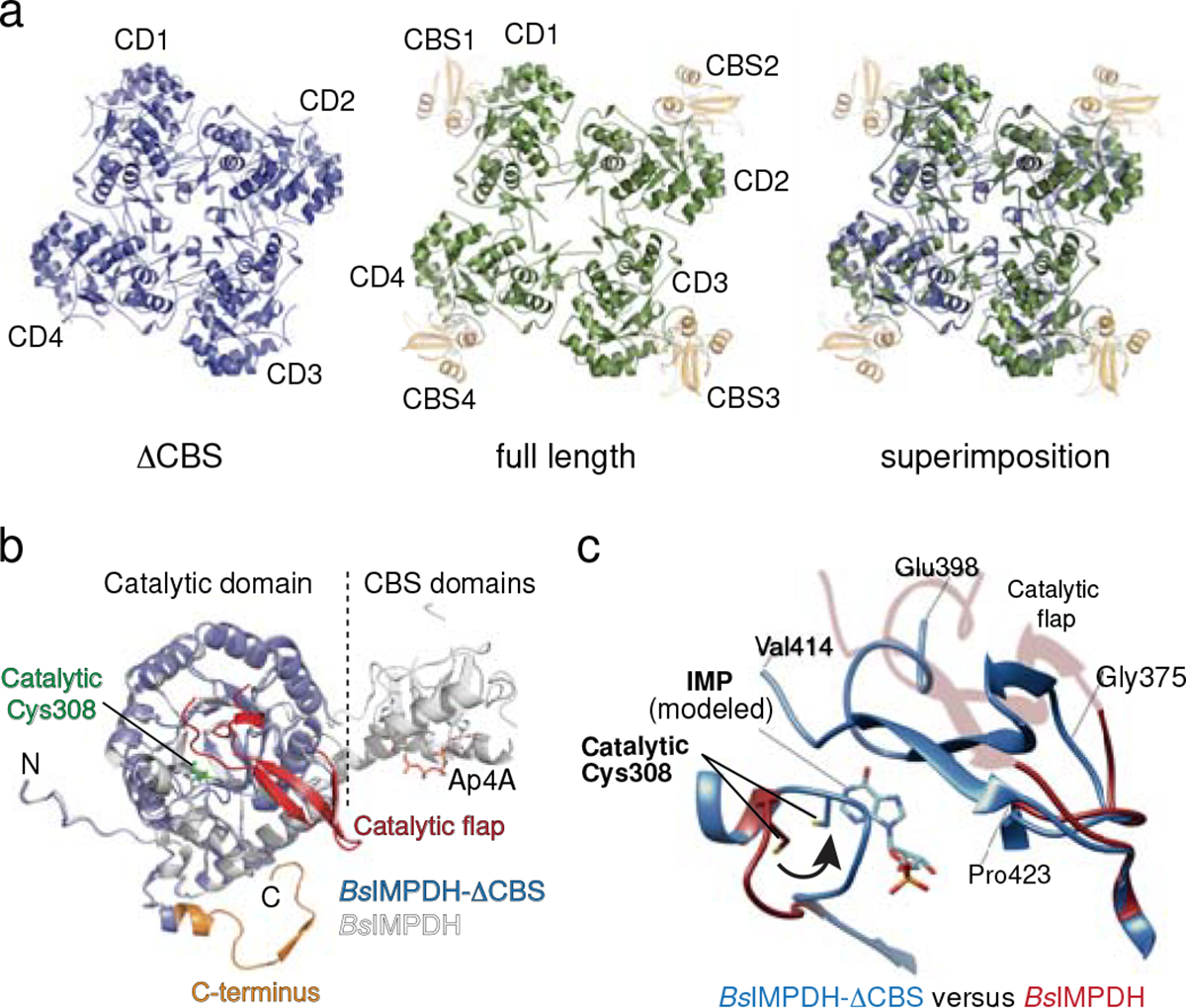

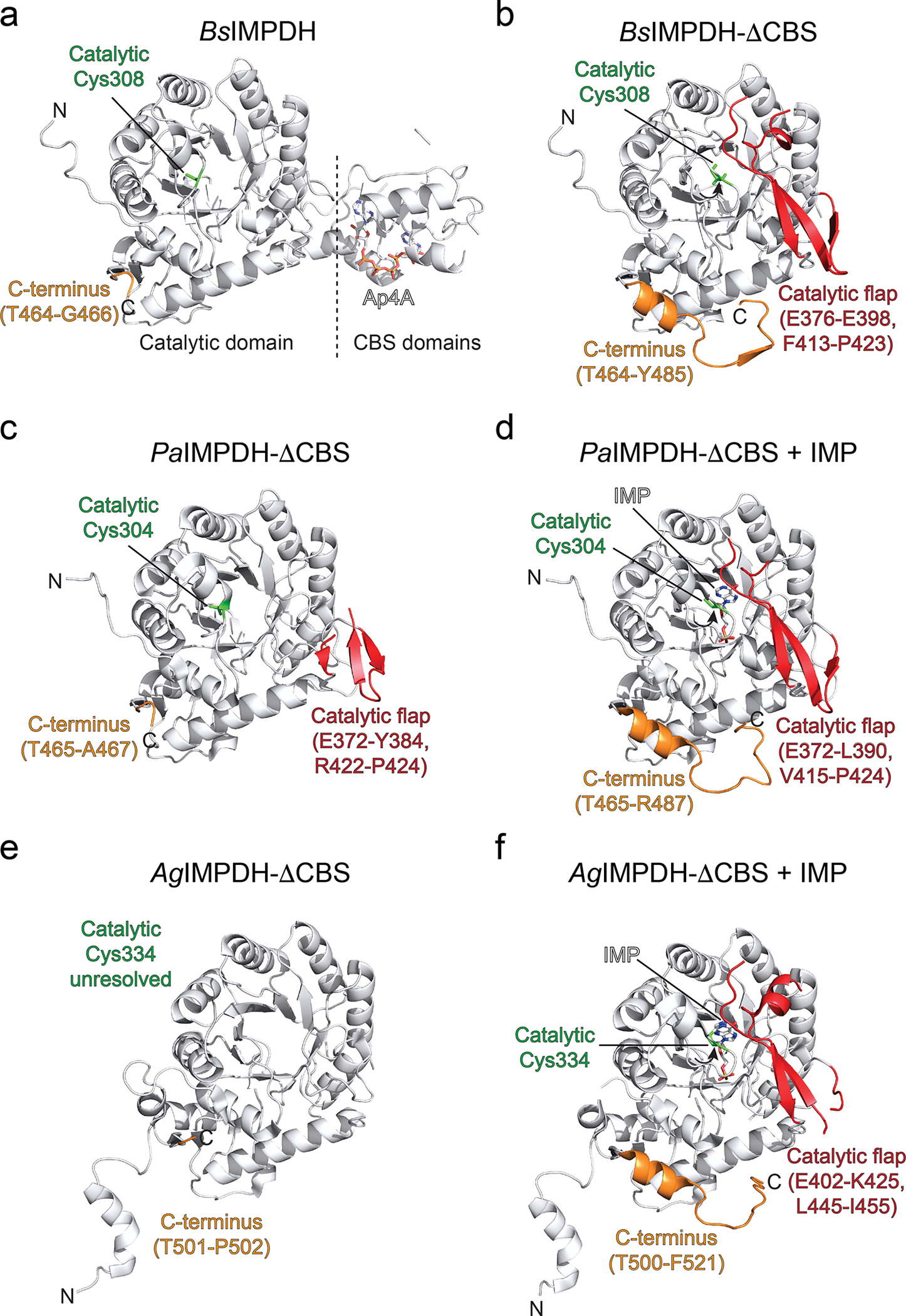

Octamerization by Ap4A alters catalytic elements in IMPDH.

Next, we wanted to understand why the Ap4A-induced octamer was catalytically less active than the tetramer. In solution employing HDX-MS we could not detect Ap4A-dependent changes in IMPDH’s active site, marked by the catalytically essential cysteine residue 30824, likely because of the high HDX rate of this region (peptides 297–308 and 297–310, see SourceData) or due to the enzyme fraction being octameric even in the absence of Ap4A (Fig. 2f). We thus made use of the exclusively tetrameric ΔCBS variant (Fig. 3a) and determined its crystal structure (Table 1). The structure of ΔCBS shows an identical tetrameric arrangement of the catalytic domains as the wildtype (Fig. 3a). In-depth comparison between the individual monomers of ΔCBS and Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH revealed that the catalytic flap (i.e., Glu376-Glu398 and Phe413-Pro423) and the C-terminal residues (i.e., Gly467-Tyr485) were resolved in the ΔCBS structure, however not in that of the Ap4A-bound wildtype (Fig. 3b). Moreover, we spotted differences in the conformation of the active site loop containing the catalytic cysteine 308 (Fig. 3c). In the Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH structure, this Cys308-containg loop points away from the catalytic site but orients towards the active center in the ΔCBS suited to execute its catalytic duty (Fig. 3c). Similar changes were also observed in the crystal structures of P. aeruginosa and A. gossypii IMPDH ΔCBS variants in the presence of the substrate IMP (Extended Data Fig. 7), and the additional function of these in establishing IMPDH tetramer-to-tetramer interfaces (forming IMPDH octamers) implied that octamerization may influence IMPDH activity allosterically31,32. Collectively, our data suggest that the Ap4A-induced octamerization has direct consequences on the conformational geometry of the active site elements, and thus IMPDH activity.

Fig. 3. Crystal structure and conformational changes in BsIMPDH ΔCBS.

a. Cartoon representation of the crystal structures of BsIMPDH-ΔCBS (blue, left), full-length BsIMPDH (green and orange for the catalytic (CD) and CBS domains, respectively, middle), and the superimposition of both structures (right). BsIMPDH-ΔCBS constitutes only one tetrameric ring through its catalytic domains opposed to CBS-dependent octamerization in full-length BsIMPDH. b. The catalytic flap (red) and C-termini (orange) could be located in BsIMPDH-ΔCBS (blue) but not full-length BsIMPDH bound to Ap4A (white) evidencing a different conformation. c. Close-up view onto the Cys308-containing catalytic loop and catalytic flap regions of BsIMPDH-ΔCBS (blue) and full-length BsIMPDH in complex with Ap4A (red). The position of the IMP substrate was approximated based on an overlay with IMP-bound P. aeruginosa IMPDH-ΔCBS (PDB-ID: 5AHM31). Cys308 is dislocated in the Ap4A bound state but oriented towards the IMP substrate-binding site of BsIMPDH-ΔCBS, thus likely representing the active conformation of IMPDH.

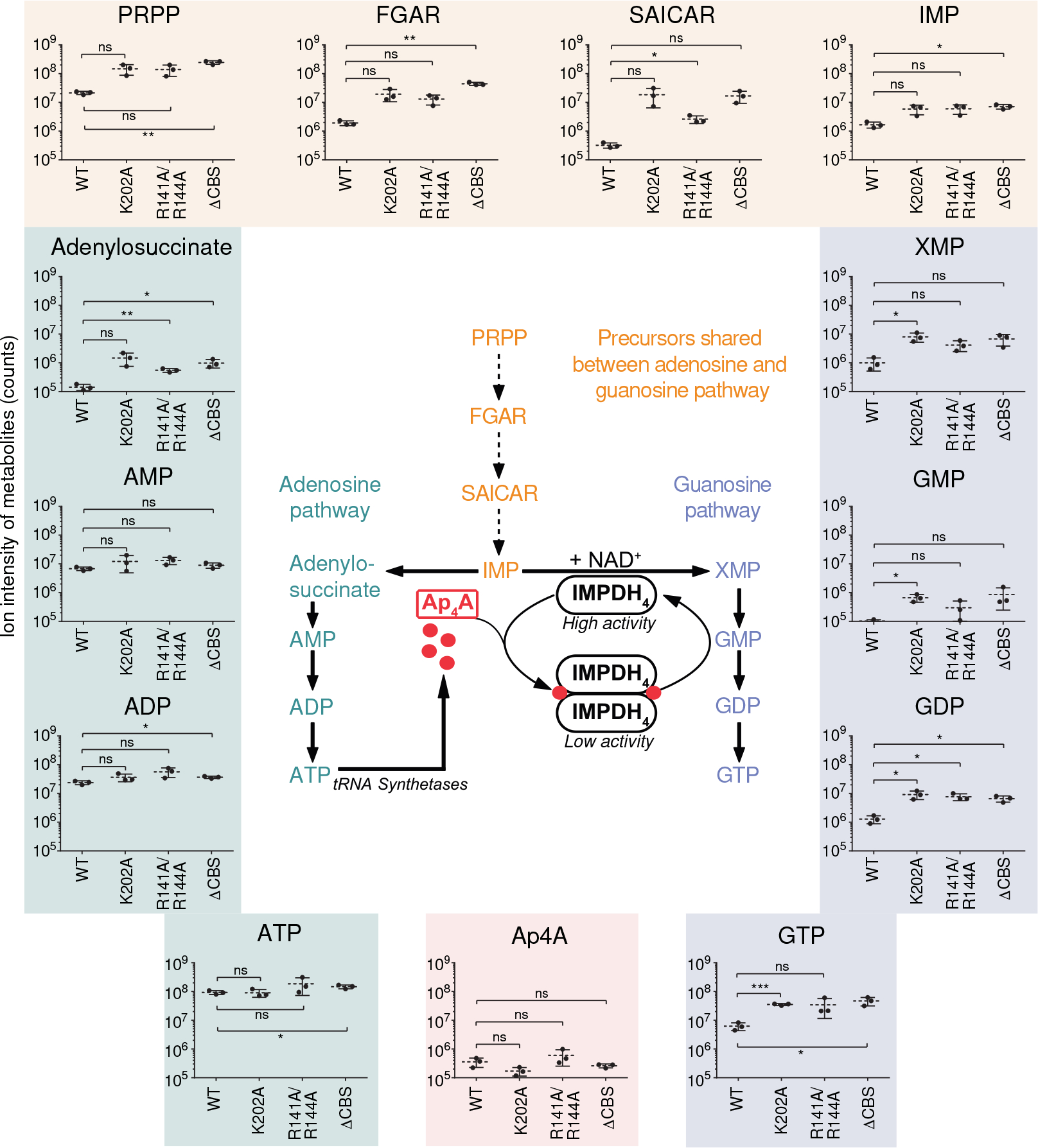

IMPDH and nucleotide metabolism in B. subtilis.

To assesses whether our in vitro findings would have physiological relevance, we constructed a series of B. subtilis strains carrying mutations in the IMPDH-encoding gene guaB at its endogenous locus, using CRISPR-mediated gene editing. In the resulting mutant strains (K202A, the R141A/R144A double mutant, and ΔCBS) we examined the levels of adenosine and guanosine nucleotides as well as their precursors by liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS). LC-MS profiling of B. subtilis grown at 30 °C revealed dysregulation of the purine nucleotide metabolism for all IMPDH mutant strains (Fig. 4). Specifically, the levels of IMP and its precursors PRPP, FGAR, and SAICAR were elevated, and similarly increased levels of XMP, GMP, GDP, and GTP, all of which derive from the IMPDH-dependent conversion of IMP to XMP, were apparent. In contrast, LC-MS suggested fewer perturbations in pools of adenylosuccinate and adenosine nucleotides. Collectively, the IMPDH mutants showed ~3- to 7-fold higher GTP:ATP ratios than the wild type, being in good agreement with our in vitro results. Collectively, our data suggest that dysregulation of IMPDH results in increased flux from the common ATP/GTP intermediate IMP towards GTP.

Fig. 4. Mutations interfering with allosteric regulation of IMPDH activity perturb nucleotide metabolism of B. subtilis.

In vivo quantification of purine nucleotide metabolism intermediates in wildtype (WT) B. subtilis 3610 and IMPDH mutant strains. Data represent mean ± SD of n=3 biological replicates. The abbreviations are: PRPP, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate; FGAR, Phosphoribosyl-N-formylglycineamide; SAICAR, phosphoribosylaminoimidazolesuccinocarboxamide; IMP, inosine-5’-monophosphate; XMP, xanthosine-5’-monophosphate; GMP, GDP, GTP, guanosine-5’-mono-, di-, triphosphate; AMP, ADP, ATP, adenosine-5’-mono-, di-, triphosphate. The inset depicts a model of nucleotide metabolism and the regulation of B. subtilis IMPDH activity. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used to compare levels of metabolites for mutant strains versus WT. Asterisks indicate p-values: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant. Exact p-values are, PRPP: 0.0653 (WT vs. K202), 0.0740 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0079 (WT vs. ΔCBS); FGAR: 0.0744 (WT vs. K202), 0.0587 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0054 (WT vs. ΔCBS); SAICAR: 0.1206 (WT vs. K202), 0.0360 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0633 (WT vs. ΔCBS); IMP: 0.0743 (WT vs. K202), 0.0706 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0120 (WT vs. ΔCBS); XMP: 0.0468 (WT vs. K202), 0.0748 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0723 (WT vs. ΔCBS); GMP: 0.0382 (WT vs. K202), 0.2521 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.1656 (WT vs. ΔCBS); GDP: 0.0435 (WT vs. K202), 0.0286 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0238 (WT vs. ΔCBS); GTP: 0.0003 (WT vs. K202), 0.1658 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0420 (WT vs. ΔCBS); Adenylosuccinate: 0.0849 (WT vs. K202), 0.0061 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0449 (WT vs. ΔCBS); AMP: 0.3275 (WT vs. K202), 0.0895 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.1809 (WT vs. ΔCBS); ADP: 0.1715 (WT vs. K202), 0.1095 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0112 (WT vs. ΔCBS); ATP: 0.8957 (WT vs. K202), 0.2897 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0332 (WT vs. ΔCBS); Ap4A: 0.1116 (WT vs. K202), 0.3522 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.3207 (WT vs. ΔCBS).

IMPDH activity and B. subtilis heat tolerance.

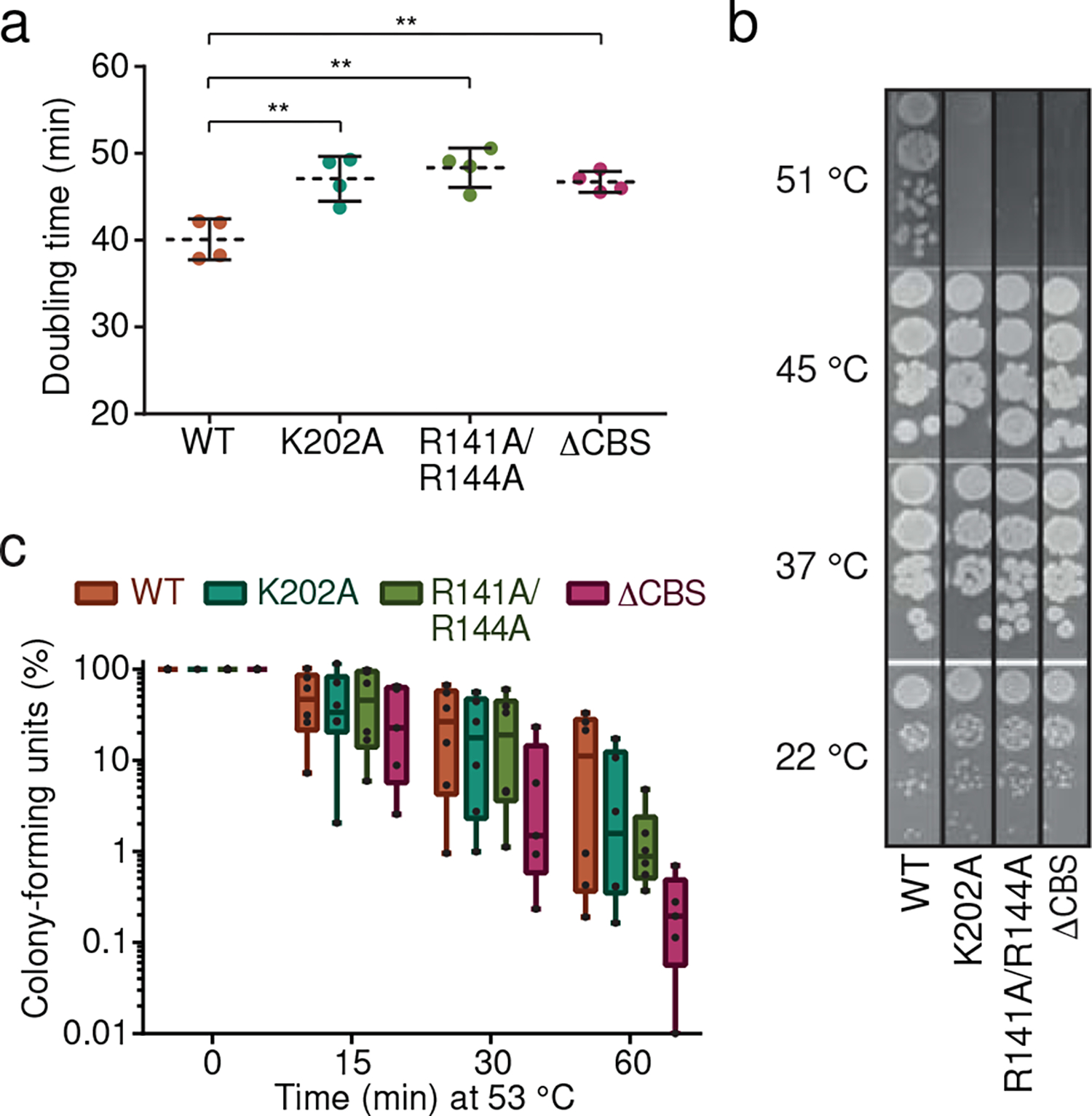

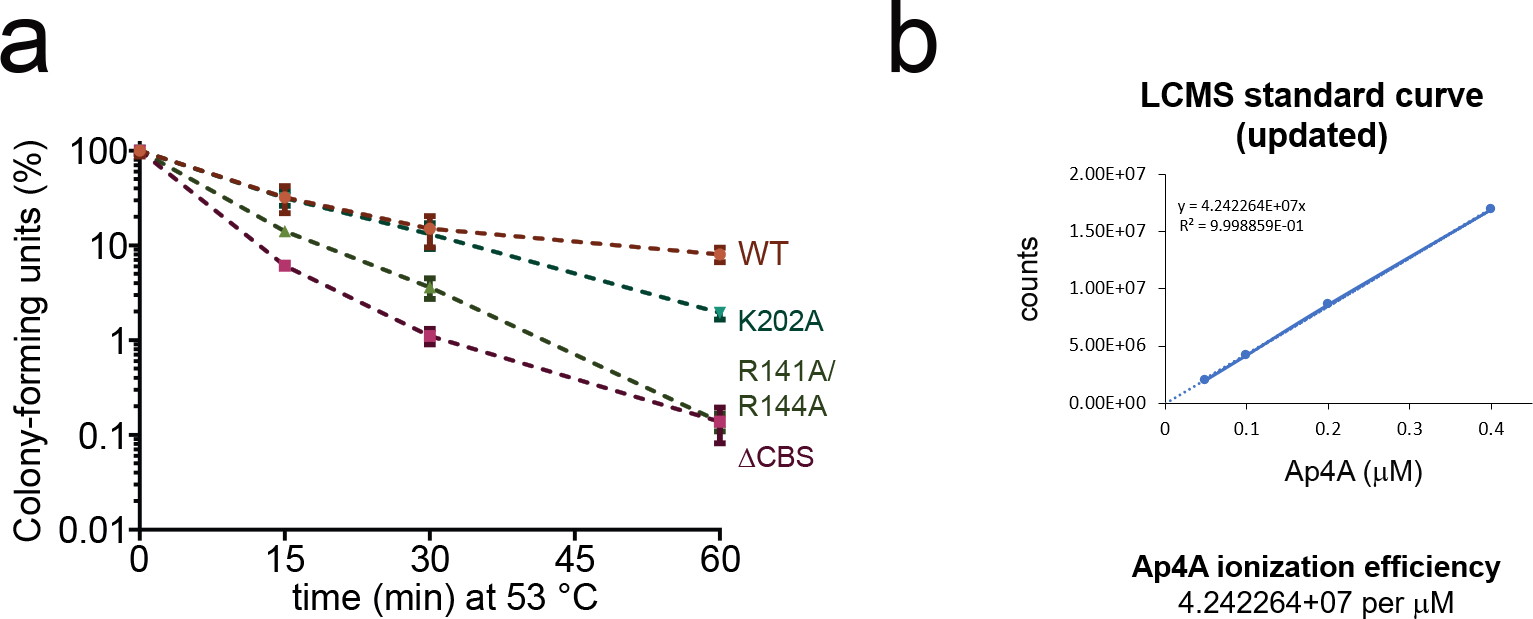

Given the profound effects of our IMPDH mutations on B. subtilis nucleotide metabolism at 30 °C (Fig. 4), we wondered whether these would translate to phenotypic differences at elevated temperatures that should promote Ap4A accumulation. Firstly, we grew wildtype B. subtilis and the mutant strains at 30 °C in liquid minimal medium (S7) whereupon the mutants displayed a higher doubling time of approx. 46 min compared to 40 min for the wildtype during logarithmic growth, which probably results from their disarrayed metabolome (Fig. 5a). Secondly, to probe temperature resistance and tolerance (Figs. 5b, 5c) phenotypes of the IMPDH mutant strains, the cultures grown to mid-log phase in S7 medium at 30 °C were used as inoculum for phenotypic characterization at elevated temperatures. On agar-plates incubated with serial dilutions at various temperatures (i.e., 22, 37, 45, 51 °C), the site-directed mutants and the ΔCBS strain displayed strongly compromised growth at 51 °C whereas at all other temperatures below 51 °C the mutants grew similarly as the wildtype cells. The K202A mutant, in contrast to R141A/R144A and ΔCBS, still afforded very weak growth even at 51 °C. These data indicate that the protective effect conferred by intact CBS domains for temperature resistance of B. subtilis is only required at higher temperatures (Fig. 5b). We furthermore investigated heat shock tolerance of our strains in liquid culture by rapidly shifting cells from 30 °C to 53 °C, a potentially lethal temperature inducing strong heat shock response33. Collectively, all investigated variants showed a mild trend towards lower survival rates than the wildtype strain although there was high variation in between the biological replicates (Fig. 5c). The K202A and R141A/R144A mutants were least affected and displayed a lower median of survival rate versus wildtype only after 60 min at 53 °C. This trend was more pronounced for the ΔCBS mutant strain. The gradation in the survival rates of the mutant strains coincides with the impact of Ap4A on oligomerization and activity of IMPDH variants in vitro (Fig. 2j, Extended Data Fig. 6g). We also quantified the intracellular Ap4A concentrations at 51 °C, showing a significant increase induced by heat shock (Extended data Fig. 8). These results suggest that regulation of IMPDH activity is critical to B. subtilis heat shock response.

Fig. 5. Allosteric regulation of IMPDH activity is critical for tolerance of B. subtilis to heat shock conditions.

a. Doubling times of wildtype B. subtilis and IMPDH mutant strains in liquid S7 minimal medium at 30 °C during logarithmic growth phase. Data represent mean ± SD of n=4 biological replicates. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used to compare doubling times for mutant strains versus WT. Asterisks indicate p-values: ** p ≤ 0.01. Exact p-values are: 0.0073 (WT vs. K202A), 0.0023 (WT vs. R141A/R144A), 0.0054 (WT vs. ΔCBS). b-c. Temperature-dependent growth of B. subtilis WT and IMPDH mutant strains. b. Serial dilutions of cultures from panel a were spotted on agar-containing S7 medium plates and incubated over night at the indicated temperatures. One representative experiment is depicted. c. Cultures grown at 30 °C were diluted in pre-warmed liquid S7 medium to reach 53 °C after mixing. Colony-forming units were enumerated from aliquots withdrawn after indicated incubation times. In the box plots, center lines represent median values, boxes the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers the min and max values. Individual data points from n=6 (n=5 for ΔCBS) biological replicates are displayed as individual points.

DISCUSSION

Ap4A is conserved across the domains of life7. In eukaryotes, Ap4A is involved in activating the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor during allergic-response-IgE34,35 and inhibiting the cGAS-STING pathway36. Diverse dinucleotides can also serve as protective mRNA-caps during disulfide stress37. Even before the discovery of the molecular chaperones, Ap4A has been considered as heat stress signal11, and been proposed to interact with DnaK, ClpB, and GroEL in E. coli14,21. Due to the lack of further targets, Ap4A was also considered as a metabolic waste product38,8.

Here, we show that Ap4A interacts with and inhibits BsIMPDH. IMPDH was previously identified as a target of Ap4A in E. coli8,19 and in murine brain lysates19, but this interaction was considered physiologically irrelevant, because Ap4A bound to E. coli IMPDH with only a five-fold higher affinity than ATP, the cellular concentration of which however is assumed to exceed that of Ap4A 5,000-fold8. Notably, IMPDHs from different organisms interact with different dinucleotides. Strength of these interactions and consequences on oligomerization state and activity vary considerably, e.g., PaIMPDH binds Ap4A or ATP8 and exhibits an octameric topology irrespective of the activity-stimulating ligand ATP25. The CBS of A. gossypii IMPDH possesses three nucleotide-binding sites, opposed to two in most other IMPDHs32,39. It binds ATP, GDP and Ap5G well, however Ap4A only with low affinity26. An open octamer of A. gossypii IMPDH with higher enzymatic activity is induced by ATP while GDP promotes a compacted octamer with diminished activity39,40. Our analysis of BsIMPDH shows that adenosine dinucleotides (ApnA), and to a lesser extent also ATP, but not mixed adenosine/guanosine dinucleotides (ApnG) enforce formation of catalytically inactive octamers. Differences in IMPDH regulation seem compounded by the structural plasticity of their CBS domains41. This plasticity enables specific binding of different ligands, e.g., mononucleotides, dinucleotides, S-adenosyl-methionine, or NAD, in different enzyme (sub-)families42.

IMPDH functions at a step where the synthetic routes for adenosine and guanosine nucleotides branch at the conversion of IMP to XMP, which subsequently serves as substrate for guanosine nucleotides (Fig. 4). Disrupting CBS-dependent inhibition of IMPDH activity in B. subtilis led to elevated GMP, GDP and GTP. GTP concentration can have a significant role in B. subtilis stress resistance43, and GTP depletion downregulates transcription of ribosomal RNA44. Thus, regulation of IMPDH activity might indirectly affect translation via GTP biosynthesis. Heat can induce protein unfolding/aggregation requiring chaperones to facilitate protein refolding or removal. Therefore, slowing translation could prevent cells from overwhelming the molecular chaperones with both the heat-induced protein aggregation and the demand of nascent protein folding, thereby promoting cellular survival. On the other side, downregulation of the guanosine nucleotides’ de novo biosynthesis through CBS domain-dependent repression of IMPDH might favor the conversion of IMP to ATP, required for ATP-dependent chaperone and protein degradation systems.

Our data suggest that IMPDH regulation affects nucleotide metabolite homeostasis. Given the shared binding sites of ATP and Ap4A at the IMPDH CBS domains, we cannot rule out the possibility that ATP, either by itself or through competition with Ap4A, also interacts with IMPDH and that our mutations impeded this potential ATP-dependent regulation. However, the Kd’s of Ap4A and ATP for BsIMPDH differ by 700-fold, and an intracellular Ap4A concentration of ~24 μM would be sufficient to restrict BsIMPDH activity in vivo in light of literature reports on cellular Ap4A levels and stress-dependent induction in some bacterial species: E. coli 0.2 μM (basal)8 or 2.4 μM (basal)45 to 270 μM (104 μg/ml cadmium sulfate after 160 min)46 and 750 μM (shift from 37–50 °C after 120 min)46, S. typhimurium <0.3 μM (basal) to 168 μM (180 μg/ml diamide after 50 min) and 365 μM (110 μg/ml cadmium chloride after 30 min)10, S. typhimurium 1 μM (basal) to 30 μM (shift from 28–50 °C after 50 min)11. Notably, overexpression of a (p)ppGpp synthetase in B. subtilis increased Ap4A 4-fold, hinting at crosstalk between Ap4A and (p)ppGpp47.

Based on our data, we hypothesize that the reduced fitness of B. subtilis strains with de-regulated IMPDH during heat shock (Figs. 5b,c), which is accompanied by an Ap4A increase, should be primarily linked to the dinucleotide and only to a lesser extent to ATP. While further research on the conserved nature of the Ap4A-dependent regulation of IMPDH is needed, we propose Ap4A as central and conserved regulator in nucleotide metabolism.

ONLINE METHODS

Cloning of native and varied BsIMPDH.

The genes encoding full-length Bacillus subtilis (Bs) IMPDH (guaB) or BsIMPDH-ΔCBS were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using chromosomal DNA of the B. subtilis NCIB3610 ΔcomI strain48 as template. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. PCR products for mutated BsIMPDH were generated by overlapping PCR. PCR products were cloned into pET-24d(+) plasmid (Novagen) using standard cloning techniques. B. subtilis lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) was amplified by PCR from the same template and introduced into pET-24d(+) plasmid (Novagen) encoding for an N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged protein.

Synthesis of 32P-labelled Ap4A.

Radiolabelled Ap4A was synthesized with LysRS from B. subtilis. The protein was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells in lysogeny broth (LB) medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 0.5 mM IPTG (added at OD600 of approximately 0.5) at 20 °C for 16 hours. The pelleted cells (3,500 × g, 20 min, 4 °C) were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES-Na pH 8.0, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) supplemented with protease inhibitors and DNaseI, and lysed by French Press. The lysate was run through a 1 ml HisTrap FF column (Cytiva) and eluted with a gradient of imidazole up to 500 mM. Fractions containing LysRS were dialyzed into fresh lysis buffer supplemented with TEV protease (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl) and applied to a 1 ml HisTrap FF column (Cytiva) to obtain the cleaved protein, which was dialyzed against SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES-Na pH 8.0, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 200 mM NaCl) overnight. LysRS was applied to a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column (Cytiva) in SEC buffer to remove TEV. The protein was concentrated and stored in SEC buffer supplemented with 10% (v/v) glycerol.

To synthesize radiolabelled Ap4A, purified B. subtilis LysRS was incubated at final concentration of 10 μM in 20 mM HEPES-Na pH 8.0, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 200 nM ZnCl2, 1.7 U/ml E. coli inorganic pyrophosphatase, 8 μCi 32P-γ-ATP and 2 mM non-radiolabelled ATP. Lastly, 1 mM lysine was added to initiate the reaction. The reaction was incubated at 37 °C and after 5 h quenched by addition of formic acid (0.33 M final). These conditions typically resulted in >70% conversion to Ap4A being a mix of labeled and unlabeled Ap4A. Ap4A was purified using a method adapted from Johnstone & Farr14 with AEX buffer A (50 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8.6) and AEX buffer B (700 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8.6). A 1 ml HiTrap QFF anion exchange chromatography column (Cytiva) was equilibrated with 10 column volumes (CV) of AEX Buffer A and the Ap4A reaction, diluted 1:10 in AEX buffer A, loaded onto the column. The column was washed with 10 CV AEX buffer A followed by a ramp of 0–20% B over 10 CV, 20–40% B over 15 CV, 40–55% B over 10 CV and 55–100% B over another 10 CV, all at 1 ml/min flow rate. Elution fractions (1 ml) were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography as described19 on PEI cellulose plates (Millipore) with 3 M (NH4)2SO4 + 2% (w/v) EDTA as mobile phase. Plates were exposed to a phosphor screen and scanned on a Typhoon scanner. Pyrophosphate eluted upon wash with AEX buffer A, ATP eluted at the 20–40% B step, and Ap4A eluted at the 40–55% B step. Fractions that contained at least 98% pure Ap4A were pooled and used for the DRaCALA screen. The final Ap4A probe solution had an estimated concentration of 0.66 mM.

DRaCALA.

The Bacillus anthracis Gateway Clone set overexpression libraries with carbenicillin and gentamicin resistance cassettes were constructed and lysates with overexpressed proteins were obtained as described previously23. Screening for binding targets of Ap4A was conducted by differential radial capillary action of ligand assay (DRaCALA)22. 32P-labelled Ap4A was diluted to 15 μM total concentration in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2), added to lysates at an equal volume, incubated for 10 min with shaking, and then spotted onto nitrocellulose paper. The spotted DRaCALA reactions were exposed to a phosphoscreen and imaged with Typhoon scanner.

Expression and purification of BsIMPDH.

BsIMPDH proteins were produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) in LB medium supplemented with 12.5 g/l D(+)-lactose-monohydrate, 50 μg/ml kanamycin for 14 h at 30 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (3,500 × g, 20 min, 4 °C), suspended in buffer A (20 mM HEPES-Na pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 40 mM imidazole) and lysed through an LM10 microfluidizer (Microfluidics) at 12,000 psi. Lysate was treated for 1 h at room temperature with TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then centrifuged (47,850 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). Supernatant was loaded onto a HisTrap HP 5 ml column (Cytiva) equilibrated with buffer A. After washing with 10 column volumes (CV) buffer A, BsIMPDH was eluted with 4 CV buffer B (20 mM HEPES-Na pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 250 mM imidazole). BsIMPDH was concentrated (Amicon Ultracel-30K (Millipore)) to 1 ml and applied to SEC (HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 200 pg, Cytiva) equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES-Na pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl and 20 mM MgCl2. BsIMPDH-containing fractions were concentrated (Amicon Ultracel-30K (Millipore)) and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. BsIMPDH concentration was quantified photometrically (NanoDrop Lite, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with extinction coefficients at 280 nm of BsIMPDH variants and BsIMPDH-ΔCBS of 21,890 and 18,910 M−1 * cm−1, respectively.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC).

ITC experiments were performed at 25 °C with a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC instrument (Malvern Panalytical). The cell was filled with 25 μM of purified BsIMPDH and titrated with different concentrations of nucleotides to reach ligand saturation. Nucleotides were purchased from Jena Bioscience (purity of ≥95%). BsIMPDH and ligands were diluted in the same buffer: 20 mM HEPES-Na pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, and 20 mM MgCl2. The titrations were performed with a first injection of 0.3 μl or 0.4 μl, which aims to remove potential air bubbles in the syringe and is being discarded from later analysis, followed by 18 injections of 2 μl each for the Ap4A titration or 12 injections of 3 μl each for all the other tested nucleotides. Data were processed with the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis Software (Malvern Panalytical) and fitted with the ‘Single set of identical sites’ model.

Assays for BsIMPDH activity.

All measurements were conducted with 100 nM BsIMPDH in 100 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl and 2 mM DTT at 25 °C. All except one assay were conducted with NAD+ (Sigma Aldrich, ≥95% by HPLC) concentration kept constant at 3 mM and IMP (Sigma Aldrich, ≥99% by HPLC) employed in variable concentrations (25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1,000 μM). In one assay (Fig. 1e), IMPDH activity was quantified at constant IMP concentration (3 mM), and NAD+ employed in variable concentrations (25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1,000, 2,500, 5,000 μM). Where denoted, nucleotides were supplemented with final concentrations of 1 μM, 3 μM 10 μM, 30 μM, and 100 μM (Ap4A), 10 μM (Ap3A, Ap5A, Ap6A, Ap3G, Ap4G, Ap5G), or 2 mM (AMP, ADP, ATP) as indicated in the figures. Enzymatic reactions were started by the addition of BsIMPDH, and the velocity of product formation was quantified by increase in absorbance at 340 nm originating from the NADH product in a microplate reader (EPOCH2, BioTek). Analysis of BsIMPDH enzyme kinetic parameters was performed with the software GraphPad Prism version 6.0.1.

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS).

Prior HDX-MS, BsIMPDH was mixed with Ap4A or ATP to reach final concentrations of 50 μM and 5 mM, respectively. HDX-MS experiments were conducted and analyzed as described previously aided by a two-arm robotic autosampler (LEAP Technologies)49. In brief, 7.5 μl of BsIMPDH solution were mixed with 67.5 μl of D2O-containing SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES-Na pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 200 mM NaCl) to start the exchange reaction. After 10, 30, 95, 1,000 or 10,000 s of incubation at 25 °C, samples of 55 μl were taken from the reaction and mixed with an equal volume of quench buffer (400 mM KH2PO4/H3PO4, 2 M guanidine-HCl, pH 2.2) kept cold at 1 °C. 95 μl of the resulting mixture were injected into an ACQUITY UPLC M-Class System with HDX Technology (Waters)50. Undeuterated samples were prepared similarly by 10-fold dilution in H2O-containing SEC buffer. BsIMPDH was digested online with immobilized porcine pepsin at 12 °C under a constant flow (100 μl/min) of water + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and the resulting peptic peptides collected on a trap column (2 mm × 2 cm) kept at 0.5 °C that was filled with POROS 20 R2 material (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 3 min, the trap column was placed in line with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 1.7 μm 1.0 × 100 mm column (Waters), and the peptides eluted at 0.5 °C using a gradient of water + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (A) and acetonitrile + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (B) at 30 μl/min flow rate as follows: 0–7 min/95–65% A, 7–8 min/65–15% A, 8–10 min/15% A. Peptides were ionized by electrospray ionization (capillary temperature 250 °C, spray voltage 3.0 kV) and mass spectra acquired from 50–2,000 m/z on a G2-Si HDMS mass spectrometer with ion mobility separation (Waters) in enhanced high definition MS (HDMSE) or high definition MS (HDMS) mode for undeuterated and deuterated samples, respectively51,52. [Glu1]-Fibrinopeptide B standard (Waters) was employed for lock mass correction. During each run, the pepsin column was washed three times with 80 μl of 4% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.5 M guanidine hydrochloride and blanks were performed between each sample. Three technical replicates (independent HDX reactions) were measured per incubation time.

Peptides were identified with ProteinLynx Global SERVER 3.0.1 (PLGS, Waters) from the non-deuterated samples acquired with HDMSE by employing low energy, elevated energy, and intensity thresholds of 300, 100 and 1,000 counts, respectively. Ions were matched to peptides with a database containing the amino acid sequences of BsIMPDH, porcine pepsin and their reversed sequences with the following search parameters: peptide tolerance = automatic; fragment tolerance = automatic; min fragment ion matches per peptide = 1; min fragment ion matches per protein = 7; min peptide matches per protein = 3; maximum hits to return = 20; maximum protein mass = 250,000; primary digest reagent = non-specific; missed cleavages = 0; false discovery rate = 100. Deuterium incorporation into peptides was quantified with DynamX 3.0 software (Waters). Only peptides that were identified in all undeuterated samples and with a minimum intensity of 25,000 counts, a maximum length of 25 amino acids, a minimum number of two products with at least 0.1 product per amino acid, a maximum mass error of 25 ppm and retention time tolerance of 0.5 minutes were considered for analysis. All spectra were manually inspected and, if necessary, peptides omitted (e.g., in case of low signal-to-noise ratio or presence of overlapping peptides). Parameters of the HDXMS experiments are in Supplementary Table 1. Raw data are in Source Data (provided as Excel file).

Protein crystallization, X-ray diffraction and structure determination.

BsIMPDH was crystallized at 20 °C by sitting drop vapor diffusion. For Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH, 250 μM of BsIMPDH was incubated with 2 mM Ap4A for 10 min at 20 °C. For BsIMPDH-ΔCBS, 250 μM protein solution was employed. Crystallization screens was performed in SWISSCI MRC 2-well plates (Jena Bioscience) with a reservoir volume of 30 μl by mixing 0.25 μl of protein with an equal volume of precipitant solution. Crystals were obtained after 2 days. Optimization-screens were carried out as hanging drop with a reservoir of 1 ml by adding 1 μl precipitant solution to 1μl of protein solution. Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH crystallized in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) and 20% (v/v) 1,2-propanediol; BsIMPDH-ΔCBS in 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.6, 0.2 M potassium/sodium tartrate and 2.0 M ammonium sulfate. Prior data collection, crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen after addition of 20% (v/v) glycerol. Data were collected under cryogenic conditions at ID23–1 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) and at P14.2 beamline of BESSY II53. Data were processed, reduced and merged with Mosflm54 and AIMLESS55. Structures of Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH and BsIMPDH-ΔCBS were solved by molecular replacement with PHASER56 and the PaIMPDH (PDB-ID: 4DQW25) as search model. Structures were built in Coot57, and refined with REFMAC558 and PHENIX refinement59. Figures were generated with PYMOL60 and ChimeraX61.

Mass Photometry.

Oligomerization of BsIMPDH was determined by mass photometry30 using the One MP mass photometer (Refeyn). Buffer composition in all measurements was: 100 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl and 2 mM DTT. To calibrate the instrument, native protein standards (Biorad) were diluted 50-fold in sample buffer at room temperature. 2 μl of diluted calibration mixture was mixed with 18 μl of sample buffer in silicone wells on a cleaned microscope slide (170 ± 5 μm thickness, Marienfeld). We used the 66, 146, 480 and 1,048 kDa peaks of the standard proteins for a four-point calibration curve. For the measurements, 18 μl buffer was pre-loaded into a silicone well, then 2 μl of a 1,000 nM concentrated protein solution was mixed in prior to acquisition (100 nM BsIMPDH final). NAD+ and IMP were used at 3 mM final concentrations. We collected 6,000 frames for each sample using default instrument parameters. Data were analyzed with the DiscoverMP software provided by Refeyn, using default parameters with reflection and movement corrections for event extraction and fitting. Frames affected by strong vibration or aggregates moving across the image were manually excluded.

Bacterial growth conditions and strain construction.

In vivo analyses were conducted using the non-domesticated B. subtilis NCBI3610 carrying the mutant comI Q12L48 (3610, wildytpe). B. subtilis cultures were grown in S7 medium47 at 30 °C. Mutant strains were constructed by the CRISPR/Cas9 method62 (Supplementary Table 2). Briefly, 5’- and 3’-ends of each repair template were amplified by PCR with one site-directed mutagenesis primer and one primer containing a unique BsaI cleavage site for Golden Gate assembly. 5’- and 3’-ends were amplified by overlap-extension PCR generating a mutant repair template flanked by two BsaI cleavage sites. Protospacers were designed and assembled as described62, and each was designed with two unique BsaI cleavage sites for Golden Gate assembly. E. coli TOP10 chemically-competent cells were transformed with the Golden Gate reactions, the plasmids isolated and subsequently used for transformation of E. coli MC1061. Isolated plasmids from the latter were used for B. subtilis 3610 transformation62. Site-specific DNA sequencing confirmed mutants (Supplementary Table 3).

LCMS quantification of metabolites.

B. subtilis strains were grown in S7 medium supplemented with 20 amino acids (20 μg/ml WY, 40 μg/ml C, 50 μg/ml ARNGQHILKMPSTVF, 500 μg/ml DE) at 30 °C until an OD600 of 0.6. For metabolite extraction, 5 ml culture were filtered through a PTFE membrane (Sartorius). The membrane was submerged in 3 ml extraction solvent mix (50:50 (v/v) chloroform/water) kept on ice and mixed vigorously for 15 seconds. Extracts were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C, the aqueous phase removed and further centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Samples were stored at −80 °C. Samples were run on an LC-MS/MS system (Q-exactive hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm, Waters) in full-scan selected ion monitoring (MS-SIM) mode. MS parameters were: 70,000 resolution; automatic gain control of 106; maximum injection time of 40 ms; scan range of 90–1,000 m/z. Analytes were eluted with a gradient of 97:3 (v/v) water/methanol, 10 mM tributylamine pH 8 (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) at 0.2 ml/min flow rate: 0–19 min/95–0% A, 19–24 min/0–95% A. Raw data were converted to mzXML format and quantification of metabolites was conducted using Metabolomics Analysis and Visualization Engine (MAVEN).

Normalized ion intensities of Ap4A were converted to intracellular concentrations as described47 with CAp4A = (Vextract * ICAp4A / ELCMS) / (Vculture * OD * Fcell), where Vextract is the volume of the aqueous phase of the extract (1.5 ml); ICAp4A is the ion intensity of Ap4A in the sample; ELCMS is the determined LC-MS detection efficiency of Ap4A (4.24 × 107 counts per μM); Vculture is the volume of the harvested culture; OD is the OD600 of the harvested culture; and Fcell is the approximate fraction of cell volume in a normalized culture (0.00052 ml per 1 ml culture per OD600). Fcell was approximated based on B. subtilis density of 2.2 × 108 CFU per ml per OD600 unit and an intracellular volume of 2.38 fl (cell length of 4 μm and radius of 0.435 μm). Intracellular concentrations of Ap3A and Ap4G were determined by same procedure. Intracellular concentrations of AMP, ADP and ATP were determined similarly but employed the LC-MS detection efficiency of ATP (2 × 108 counts per μM).

Heat shock experiments.

B. subtilis strains were inoculated into S7 medium supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) casamino acids and grown at 30 °C until an OD600 of 0.3–0.4. These cultures were inoculated into fresh media in a 96-well plate and grown in a plate reader (BioTek) at 30 °C with shaking for 16 hours. For measurement of heat resistance, aliquots were withdrawn from cultures of each strain, and serial dilutions thereof employed to spot agar-containing S7 plates for incubation overnight at 22, 37, 45, or 51 °C. Plates were photographed to examine the growth at each temperature. For measurement of heat tolerance, 50 μl of the cultures were used to inoculate a tube containing 2 ml S7 medium supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) casamino acids pre-warmed to 53 °C. Samples for enumeration of colony-forming units were withdrawn before heat shock (0 min) or after 15, 30, or 60 min of incubation under vigorous agitation and incubated on LB agar plates at 30 °C until countable colonies were obtained.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Binding of nucleotides and dinucleotides to BsIMPDH determined by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC).

a-j. A 25 μM concentrated solution of purified BsIMPDH was titrated with a. AMP, b. ADP, c. ATP, d. Ap3A, e. Ap4A, f. Ap5A, g. Ap6A, h. Ap3G, i. Ap4G, or j. Ap5G. The differential power (DP, upper plot) for each injection of ligand was recorded and used to determine the dissociation constant Kd from a fitting of the calculated binding enthalpies (ΔH, lower plot).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Enzyme kinetic parameters obtained for BsIMPDH.

a-c. The maximal velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) of BsIMPDH activity were determined in the presence of various ligands. For Ap4A, the inhibitory constant (Ki) was fitted from the change in Vmax in the presence of different Ap4A concentrations. The mean ± SD of enzymological parameters was obtained with Graph Pad Prism from n=2 replicates. For assay results displayed in a (related to Figs. 1e–h) and c (related to Extended Data Fig. 6a), the concentration of NAD+ was kept constant at 5 mM and the concentration of IMP variable between 25 and 1,000 μM. For the assay results displayed in b (related to Fig. 1e), the concentration of IMP was kept constant at 3 mM and the concentration of NAD+ variable between 25 and 5,000 μM. n.d., not determined.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Coordination of Ap4A by the BsIMPDH CBS domains.

a. The CBS domains of the B. subtilis IMPDH (red, this study) were aligned with the CBS domains of P. aeruginosa IMPDH (left; pink, PDB-ID: 4DQW25), A. gossypii IMPDH (middle; light blue, PDB-ID: 6RPU26), and C. perfringens pyrophosphatase (right; salmon, PDBID: 3L2B63, revealing on overall similar topology. b. The unbiased Fobs-Fcalc difference electron density map (top) is colored in green and red for positive and negative electron density, respectively, and contoured at 3.0 σ. The Ap4A ligand was not present during the refinement. The 2Fobs−Fcalc electron density map after final refinement (bottom), including the Ap4A ligand, is colored in blue and contoured at 1.5 σ. c. Coordination of Ap4A in chains A and B of the crystal structure of Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH. Atoms are displayed as spheres and colored as follows: carbon, black; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; phosphor, purple. Purple and orange solid lines illustrate ligand or non-ligand covalent bonds, and green dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. Red semicircles denote hydrophobic interactions. The image was generated with LigPlot+64. d. Coordination of ligands by the CBS domains of B. subtilis IMPDH with Ap4A (left), P. aeruginosa IMPDH with 2 ATP (middle, PDB-ID: 4DQW25), and A. gossypii IMPDH with Ap5G (right, PDB-ID: 6RPU26). Ligands and amino acid residues lining the ligand-binding sites are shown as sticks and colored by element (carbon, green/yellow/cyan; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; phosphor, orange). Green and purple spheres represent magnesium and manganese ions, respectively. Dashed lines denote hydrogen bonding interactions between the main chain carbonyl/amide groups and the adenine and guanine nucleobases. A. gossypii IMPDH does not require a divalent metal ion to coordinate the GDP ligand, whereas metal ion coordination in the prokaryotic B. subtilis and P. aeruginosa IMPDHs is achieved by E184 and E180 residues, respectively40.

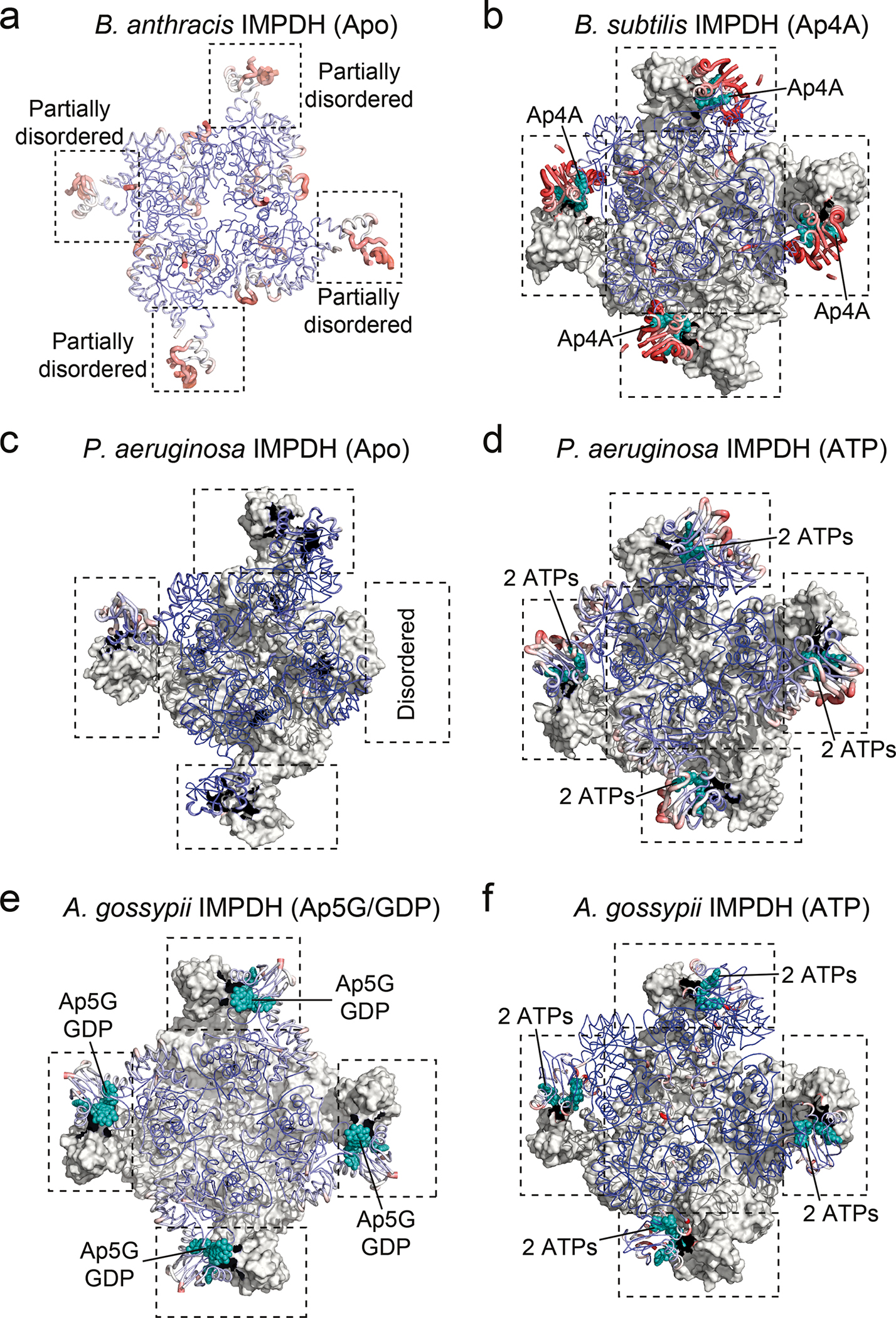

Extended Data Fig. 4. Conformational flexibility of CBS domains in crystal structures of selected IMPDH proteins.

a-f. The crystal structures of IMPDH proteins from a. B. anthracis in apo-state (PDB-ID: 3TSB65), b. B. subtilis bound to Ap4A (this study), c. P. aeruginosa in apo-state (PDB-ID: 6GJV66), d. P. aeruginosa bound to ATP (PDB-ID: 4DQW25), e. A. gossypii bound to Ap5G and GDP (PDB-ID: 6RPU26), and f. A. gossypii bound to ATP (PDB-ID: 5MCP39) are shown as ribbon and colored to their B factors from 20 (blue) to 150 Å2 (red). For octameric biological assemblies, the bottom tetrameric ring is shown in grey surface. CBS domains are indicated by black dashed rectangles, and teal spheres denote the nucleotide ligands coordinates within the CBS domains.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Influence of Ap4A and ATP on conformational flexibility of BsIMPDH CBS domains by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry.

a. Difference in hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) of representative peptides in the presence of Ap4A (top) or ATP (bottom), expressed as the difference in HDX of ligand-bound BsIMPDH versus its apo-state. b. Location of selected peptides exhibiting bimodality in HDX (EX1 kinetics) displayed on the adjacent CBS domains of two monomers of Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH. c-d. Mass spectra of two selected BsIMPDH peptides exhibiting EX1 kinetics for hydrogen/deuterium exchange, i.e., c. the peptides containing residues 113–136, and d. residues 172–200 of BsIMPDH. The occurrence of a fastexchanging population in the apo-state (red) is indicative for unfolding of secondary structures, which is restricted in samples of Ap4A-bound (blue) and ATP-bound (green) BsIMPDH.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Enzymatic activity and oligomeric state of BsIMPDH-WT and CBS domain variants.

a. Representative distributions of tetrameric and octameric BsIMPDH species for BsIMPDH-WT in the absence of IMP and NAD+ substrates and in dependence of Ap4A or ATP concentration. b-e. Representative distributions of tetrameric and octameric BsIMPDH species of b. BsIMPDH-WT, c. BsIMPDH-K202A, d. BsIMPDH-R141A/R144A, and e. BsIMPDH-ΔCBS, all in the presence of IMP and NAD+ substrates and in dependence of Ap4A or ATP concentration. f. Representative distributions of tetrameric and octameric BsIMPDH species for BsIMPDH-WT in the presence of IMP and NAD+ substrates and in dependence of the indicated adenosine nucleotides or ApnA and ApnG dinucleotides added. In a-f, the numbers in the diagrams reflect the molecular weight of the observed oligomeric species (mean and SD), the number of observed molecules for either species and their percentage of all observed molecules in the sample. g. Effect of 10 μM Ap4A or 2 mM ATP on the enzyme-kinetic behavior of BsIMPDH-WT and CBS domain variants K202A, R141A/R144A and ΔCBS for conversion of the IMP substrate into XMP. Individual data points of n=2 replicates are shown, and parameters of the fits are given in Extended Data Fig. 2c. h. Correlation between observed fraction of IMPDH monomers in oligomeric state and the apparent Vmax of IMPDH activity. Linear regression was performed either with values for BsIMPDH WT only (red trace) or all depicted values including WT and variants (blue trace). Red and blue numbers denote values for the fraction and Vmax at the intersects with the x-axis and y-axis, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Different conformations of catalytic flap and Ctermini regions in crystal structures of IMPDH enzymes.

a-f. Cartoon representations of the crystal structures of a. Ap4A-bound full-length B. subtilis (Bs) IMPDH, b. B. subtilis (Bs) IMPDH-ΔCBS, c. P. aeruginosa (Pa) IMPDH-ΔCBS (PDB-ID: 5AHL31), d. P. aeruginosa (Pa) IMPDH-ΔCBS with substrate IMP in the active site (PDB-ID: 5AHM31), e. A. gossypii (Ag) IMPDH-ΔCBS (PDB-ID: 4XWU32), and f. A. gossypii (Ag) IMPDH-ΔCBS with substrate IMP in the active site (PDB-ID: 4XTI32). The catalytic cysteine (green), catalytic flap (red) and C-termini (orange) where colored and denoted where possible.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Quantification of rising intracellular Ap4A concentrations in B. subtilis after nonlethal heat shock.

In vivo quantification of Ap4A in wildtype (WT) B. subtilis 3610 and IMPDH mutant strains. Data represent mean ± SD of n=3 biological replicates. Unpaired twotailed t-tests were used to compare Ap4A levels for WT and IMPDH mutant strains of heat-shocked conditions (15 min, 30 min) versus the untreated control (0 min). Asterisks indicate p-values: * p ≤ 0.05; ns, not significant. Exact p-values are, WT: 0.1382 (15 vs. 0 min), 0.0943 (30 vs. 15 min), 0.0235 (30 vs. 0 min); K202A: 0.0191 (15 vs. 0 min), 0.5491 (30 vs. 15 min), 0.0223 (30 vs. 0 min); R141A/R144A: 0.4789 (15 vs. 0 min), 0.8778 (30 vs. 15 min), 0.3756 (30 vs. 0 min); ΔCBS: 0.0753 (15 vs. 0 min), 0.1146 (30 vs. 15 min), 0.0390 (30 vs. 0 min).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the priority program of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) SPP1879 – “Nucleotide second messenger signaling in bacteria” (to GB), the USA National Institute of Health R35 GM127088 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Faculty Scholars Award (to JDW), and the National Science Foundation (NSF) grant award no. 1715710 (to DAN). We thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) and the Electron Storage Ring BESSY II (Berlin, Germany) for the excellent beamline support. We acknowledge support from the “DFG-core facility for interactions, dynamics and macromolecular assembly structure” at the Philipps-University Marburg (to GB). GH acknowledges support from the Free-floater program of the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Structure factors and coordinates of X-ray crystallographic datasets have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) under the accession codes 7OJ1 and 7OJ2 for the Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH and BsIMPDH-ΔCBS, respectively. All other structural data employed in this manuscript (accession codes 3L2B, 3TSB, 4DQW, 4XTI, 4XWU, 5AHL, 5AHM, 5MCP, 6GJV, 6RPU) are publicly available in the Protein Data Bank. Source data are provided with this paper for figures 1, 2, 4, and 5, and for Extended data figures 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8.

References

- 1.Steinchen W & Bange G The magic dance of the alarmones (p)ppGpp. Molecular Microbiology 101, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauryliuk V, Atkinson GC, Murakami KS, Tenson T & Gerdes K Recent functional insights into the role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial physiology. Nature Reviews Microbiology 13, 298–309 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hengge R High-Specificity Local and Global c-di-GMP Signaling. Trends in Microbiology (2021) doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenal U, Reinders A & Lori C Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nature reviews. Microbiology 15, 271–284 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stülke J & Krüger L Cyclic di-AMP Signaling in Bacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology vol. 74 159–179 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamecnik PG, Stephenson ML, Janeway CM & Randerath K Enzymatic synthesis of diadenosine tetraphosphate and diadenosine triphosphate with a purified lysyl-sRNA synthetase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 24, 91–97 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson F, McLennan AG, Urbaniak MD, Jones NJ & Copeland NA Re-evaluation of Diadenosine Tetraphosphate (Ap4A) From a Stress Metabolite to Bona Fide Secondary Messenger. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 7, 332 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Despotović D et al. Diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) – an E. coli alarmone or a damage metabolite? FEBS Journal 284, 2194–2215 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlier J & Sanchez R Lysyl-tRNA synthetase from Escherichia coli K12. Chromatographic heterogeneity and the lysU-gene product. The Biochemical journal 248, 43–51 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bochner BR, Lee PC, Wilson SW, Cutler CW & Ames BN AppppA and related adenylylated nucleotides are synthesized as a consequence of oxidation stress. Cell 37, 225–232 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PC, Bochner BR & Ames BN AppppA, heat-shock stress, and cell oxidation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 80, 7496 LP – 7500 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura A et al. Diadenosine 5’,5’’’-P1,P4-tetraphosphate (Ap4A) controls the timing of cell division in Escherichia coli. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms 2, 401–413 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farr SB, Arnosti DN, Chamberlin MJ & Ames BN An apaH mutation causes AppppA to accumulate and affects motility and catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 86, 5010–5014 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone DB & Farr SB AppppA binds to several proteins in Escherichia coli, including the heat shock and oxidative stress proteins DnaK, GroEL, E89, C45 and C40. The EMBO journal 10, 3897–3904 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji X et al. Alarmone Ap4A is elevated by aminoglycoside antibiotics and enhances their bactericidal activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 9578–9585 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura Y, Tanaka C, Sasaki K & Sasaki M High concentrations of intracellular Ap4A and/or Ap5A in developing Myxococcus xanthus cells inhibit sporulation. Microbiology (Reading, England) 163, 86–93 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monds RD et al. Di-adenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) metabolism impacts biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens via modulation of c-di-GMP-dependent pathways. Journal of Bacteriology 192, 3011–3023 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundin A et al. The NudA protein in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is an ubiquitous and constitutively expressed dinucleoside polyphosphate hydrolase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278, 12574–12578 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo W et al. Isolation and identification of diadenosine 5′,5‴-P 1,P 4-tetraphosphate binding proteins using magnetic bio-panning. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters 21, 7175–7179 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azhar MA, Wright M, Kamal A, Nagy J & Miller AD Biotin-c10-AppCH2ppA is an effective new chemical proteomics probe for diadenosine polyphosphate binding proteins. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 24, 2928–2933 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuge EK & Farr SB AppppA-binding protein E89 is the Escherichia coli heat shock protein ClpB. Journal of bacteriology 175, 2321–2326 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roelofs KG, Wang J, Sintim HO & Lee VT Differential radial capillary action of ligand assay for high-throughput detection of protein-metabolite interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 15528–15533 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J et al. The nucleotide pGpp acts as a third alarmone in Bacillus, with functions distinct from those of (p) ppGpp. Nature communications 11, 5388 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedstrom L IMP dehydrogenase: structure, mechanism, and inhibition. Chemical reviews 109, 2903–2928 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labesse G et al. MgATP regulates allostery and fiber formation in IMPDHs. Structure 21, 975–985 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Justel D, Peláez R, Revuelta JL & Buey RM The Bateman domain of IMP dehydrogenase is a binding target for dinucleoside polyphosphates. Journal of Biological Chemistry 294, 14768–14775 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weis DD, Wales TE, Engen JR, Hotchko M & Ten Eyck LF Identification and Characterization of EX1 Kinetics in H/D Exchange Mass Spectrometry by Peak Width Analysis. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 17, 1498–1509 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z & Smith DL Determination of amide hydrogen exchange by mass spectrometry: a new tool for protein structure elucidation. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 2, 522–531 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexandre T, Rayna B & Munier-Lehmann H Two Classes of Bacterial IMPDHs according to Their Quaternary Structures and Catalytic Properties. PLOS ONE 10, e0116578 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young G et al. Quantitative mass imaging of single biological macromolecules. Science 360, 423 LP – 427 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labesse G, Alexandre T, Gelin M, Haouz A & Munier-Lehmann H Crystallographic studies of two variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa IMPDH with impaired allosteric regulation. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 71, 1890–1899 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buey RM, Ledesma-Amaro R, Balsera M, de Pereda JM & Revuelta JL Increased riboflavin production by manipulation of inosine 5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase in Ashbya gossypii. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 99, 9577–9589 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schäfer H et al. The alarmones (p)ppGpp are part of the heat shock response of Bacillus subtilis. PLOS Genetics 16, e1008275 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y-N, Nechushtan H, Figov N & Razin E The Function of Lysyl-tRNA Synthetase and Ap4A as Signaling Regulators of MITF Activity in Fc_RI-Activated Mast Cells. Immunity 20, 145–151 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yannay-Cohen N et al. LysRS Serves as a Key Signaling Molecule in the Immune Response by Regulating Gene Expression. Molecular Cell 34, 603–611 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerra J et al. Lysyl-tRNA synthetase produces diadenosine tetraphosphate to curb STING-dependent inflammation. Science Advances 6, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luciano DJ, Levenson-Palmer R & Belasco JG Stresses that Raise Np4A Levels Induce Protective Nucleoside Tetraphosphate Capping of Bacterial RNA. Molecular cell 75, 957–966.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baltzinger M, Ebel JP & Remy P Accumulation of dinucleoside polyphosphates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under stress conditions. High levels are associated with cell death. Biochimie 68, 1231–1236 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buey RM et al. A nucleotide-controlled conformational switch modulates the activity of eukaryotic IMP dehydrogenases. Scientific Reports 7, 2648 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buey RM et al. Guanine nucleotide binding to the Bateman domain mediates the allosteric inhibition of eukaryotic IMP dehydrogenases. Nature Communications 6, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ereño-Orbea J, Oyenarte I & Martínez-Cruz LA CBS domains: Ligand binding sites and conformational variability. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 540, 70–81 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anashkin VA, Baykov AA & Lahti R Enzymes Regulated via Cystathionine β-Synthase Domains. Biochemistry. Biokhimiia 82, 1079–1087 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kriel A et al. Direct regulation of GTP homeostasis by (p)ppGpp: a critical component of viability and stress resistance. Molecular cell 48, 231–241 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krásný L & Gourse RL An alternative strategy for bacterial ribosome synthesis: Bacillus subtilis rRNA transcription regulation. The EMBO journal 23, 4473–4483 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plateau P, Fromant M, Kepes F & Blanquet S Intracellular 5’,5’-dinucleoside polyphosphate levels remain constant during the Escherichia coli cell cycle. Journal of bacteriology 169, 419–422 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coste H, Brevet A, Plateau P & Blanquet S Non-adenylylated bis(5’-nucleosidyl) tetraphosphates occur in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in Escherichia coli and accumulate upon temperature shift or exposure to cadmium. The Journal of biological chemistry 262, 12096–12103 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fung DK, Yang J, Stevenson DM, Amador-Noguez D & Wang JD Small Alarmone Synthetase SasA Expression Leads to Concomitant Accumulation of pGpp, ppApp, and AppppA in Bacillus subtilis. Frontiers in microbiology 11, 2083 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konkol MA, Blair KM & Kearns DB Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. Journal of bacteriology 195, 4085–4093 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osorio-Valeriano M et al. ParB-type DNA Segregation Proteins Are CTP-Dependent Molecular Switches. Cell 179, 1512–1524.e15 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wales TE, Fadgen KE, Gerhardt GC & Engen JR High-speed and high-resolution UPLC separation at zero degrees Celsius. Analytical chemistry 80, 6815–6820 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geromanos SJ et al. The detection, correlation, and comparison of peptide precursor and product ions from data independent LC-MS with data dependant LC-MS/MS. PROTEOMICS 9, 1683–1695 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li G-Z et al. Database searching and accounting of multiplexed precursor and product ion spectra from the data independent analysis of simple and complex peptide mixtures. PROTEOMICS 9, 1696–1719 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mueller U et al. The macromolecular crystallography beamlines at BESSY II of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin: Current status and perspectives. The European Physical Journal Plus 130, 141 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powell HR, Battye TGG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O & Leslie AGW Integrating macromolecular X-ray diffraction data with the graphical user interface iMosflm. Nature protocols 12, 1310–1325 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evans PR & Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 69, 1204–1214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCoy AJ Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 63, 32–41 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murshudov GN et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallographica Section D 67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afonine PV et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallographica Section D 68, 352–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schrödinger L The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pettersen EF et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 30, 70–82 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burby PE & Simmons LA CRISPR/Cas9 Editing of the Bacillus subtilis Genome. Bio-protocol 7, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tuominen H et al. Crystal structures of the CBS and DRTGG domains of the regulatory reagion of clostridium perfringens pyrophosphatase complexed with the inhibitor, AMP, and activator, diadenosine tetraphosphate. Journal of Molecular Biology 398, 400–413 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laskowski RA & Swindells MB LigPlot+: Multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 51, 2778–2786 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Makowska-Grzyska M et al. Bacillus anthracis inosine 5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase in action: the first bacterial series of structures of phosphate ion-, substrate-, and product-bound complexes. Biochemistry 51, 6148–6163 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexandre T et al. First-in-class allosteric inhibitors of bacterial IMPDHs. European journal of medicinal chemistry 167, 124–132 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Structure factors and coordinates of X-ray crystallographic datasets have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) under the accession codes 7OJ1 and 7OJ2 for the Ap4A-bound BsIMPDH and BsIMPDH-ΔCBS, respectively. All other structural data employed in this manuscript (accession codes 3L2B, 3TSB, 4DQW, 4XTI, 4XWU, 5AHL, 5AHM, 5MCP, 6GJV, 6RPU) are publicly available in the Protein Data Bank. Source data are provided with this paper for figures 1, 2, 4, and 5, and for Extended data figures 1, 2, 5, 6, and 8.