Abstract

Background

Recent studies suggested that MPTP could cause gastrointestinal motility deficits additionally to its nonconclusive and controverted effects on the CNS (behavior and brain oxidative stress) in rats. A possible interaction between MPTP typical impairments and magnesium modulatory potential was previously suggested, as magnesium role was described in neuroprotection, gastrointestinal function, and oxidative stress.

Aim

To investigate the possible modulatory effect of several magnesium intake formulations (via drinking water) in MPTP neurotoxicity and functional gastrointestinal impairment induction.

Materials and Methods

Adult male Wistar rats were subjected to 3-week magnesium intake-controlled diets (magnesium depleted food and magnesium enriched drinking water) previously to acute subcutaneous MPTP treatment (30 mg/ kg body weight). Gastrointestinal motility (one hour stool collection test), and behavioral patterns (Y maze task, elevated plus maze test, open field test, forced swim test) were evaluated. Followingly, brain and bowel samples were collected, and oxidative stress was evaluated (glutathione peroxidase activity, malondial-dehyde concentrations).

Results

MPTP could lead to magnesium intake-dependent constipation-like gastrointestinal motility impairments, anxiety- and depressive-like affective behavior changes, and mild pain tolerance defects. Also, we found similar brain and intestinal patterns in magnesium-dependent oxidative stress.

Conclusion

While the MPTP effects in normal magnesium intake could be regarded as not fully relevant in rat models and limited to the current experimental conditions, the abnormalities observed in the affective behavior, gastrointestinal status, pain tolerance, peripheric and central oxidative status could be indicative of the extent of the systemic effects of MPTP that are not restricted to the CNS level, but also to gastro-intestinal system.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, animal model, MPTP, locomotor impairment, anxious behavior, depressive-like behavior, gastrointestinal

INTRODUCTION

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is one of the most used neurotoxins to induce Parkinson’s disease (PD) in animal models (1). The main molecular mechanism triggered by MPTP that leads to PD-like neurobehavioral effects affects dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra as a result of monoamine oxidase system - dependent MPTP conversion into the toxic 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) (2). Controversial results were obtained in rat models, as some suggested that MPTP could not cross the blood-brain barrier due to the monoamine oxidase B system that effectively breaks down MPTP molecules (3).

Despite this limitation, later studies demonstrated that MPTP effects could extend beyond central nervous system (CNS). Thus, functional gastrointestinal symptoms (i.e., constipation and delayed gastric emptying) associated with ileum inflammation, gut microbiota dysbiosis, local immune disorders (intestine), and motor dysfunctionalities were reported in MPTP rodent models (4-6). Striatal dopamine reduction – modulated systemic and liver inflammation, as well as depressive behavior followed repeated nasal administration of MPTP (7). Also, a decrease in the myenteric dopamine levels was observed in the absence of CNS dopamine depletion, suggesting that the gastrointestinal tract toxic effects might be unrelated to the CNS toxic effects (2, 8). They seem to be due to an altered release of catecholamines (norepinephrine and dopamine) from the intestinal sympathetic nerves or the adrenal gland (9).

Magnesium, one of the essential micronutrients, was extensively described as an important metabolic and neurochemical modulator in both children and adults (10-12). Magnesium deficit may play a distinct role in neurodegenerative and socio-affective pathological mechanisms (10), possible by closely interacting with the monoamine oxidases and dopaminergic systems. Moreover, its capacity to block the calcium channels in the NMDA receptors (10-12) was demonstrated to antagonize the MPTP-induced neurotoxicity mechanism (13, 14).

The modulation of anxiety-and depression-like behaviors (15), as well as of the functional constipation and improved bowel movements (16, 17) were reported in magnesium-treated animal models. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of magnesium were previously well documented in both rodent models and human, also suggesting that gut motility and microflora are closely dependent on magnesium intake and availability (18, 19).

Thus, by taking into consideration the role of magnesium in both the CNS and the gastrointestinal tract physiological mechanisms and given that MPTP exhibits potent toxic effects on both systems, we aimed to investigate the possible modulatory effect of several magnesium intake formulations (via drinking water) in MPTP neurotoxicity and functional gastrointestinal impairment induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and housing

Adult male Wistar rats (4 – 5 months old, 200 g body weight, n = 95) were supplied by acquisition from The Institute of Veterinary Hygiene and Public Health (Iasi, Romania). During the experiment, the animals were housed a room with controlled temperature (22°C) and a 12:12-h light/dark cycle (starting at 08:00 h) in polyethylene cages (5 animals per cage). The animals were treated in accordance with the guidelines of animal bioethics from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (no. USAMV Iasi 385/04.04.2019) and efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and their suffering.

Experimental design

The magnesium intake was controlled for 3 weeks by offering to the animals standard laboratory magnesium-deprived animal food and magnesium-enriched drinking water (in house preparation using distilled water and magnesium chloride, Chemoreactiv, Romania), which were both ad libitum distributed. The magnesium-depleted food was kindly provided by Dr. Kolisek from Freie University (Berlin, Germany).

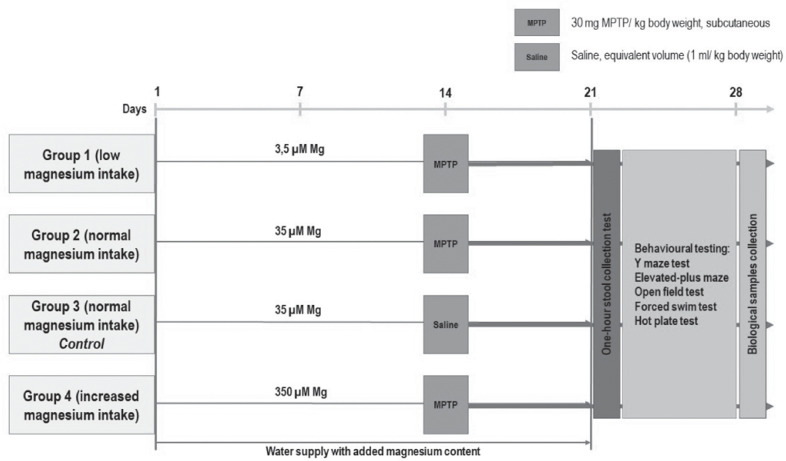

The animals were randomly divided into four groups, each group receiving drinking water containing 3.5 µM Mg (Group 1, n = 25), 35 µM Mg (Group 2, n = 22; Group 3, n = 23), and 350 µM Mg (Group 4, n = 25), respectively. In day 14, a single dose of MPTP (30 mg/kg, in saline solution) was subcutaneously administered to groups 1, 2, and 4, according to Aubin et al., 1998, while group 3 received saline solution solely (thus, being considered the reference group and referred as control throughout the experiment) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental design and procedures.

Starting with day 22 (for 7 days), all the groups were subjected to gastrointestinal assessment followed by behavioral testing (Y maze test, elevated-plus maze, open field, forced swim test and hot plate test). Afterwards, the animals were anesthetized (ketamine 100 mg/kg, xylazine 10 mg/kg) and whole brain and colon were collected, processed, and sampled for biochemical analysis.

Stool and gastrointestinal transit assessment

The gastrointestinal function was assessed by evaluating the colon motility in One-hour stool collection test (33). For this test, the animals (preserving the experimental grouping) were placed in clean cages following a 2-hour period of free access to food. After one hour, stools were collected, visually assessed for consistency, and the animals were returned to their home cages. The dry weight and water content of the total stools was measured following drying session (12 hours at 65°C).

Behavioural testing

Y maze

Y maze test was used to assess short-term memory performance by evaluating the exploratory behavior that the animals exhibit in the Y-shaped maze. The maze consisted of three arms (35 cm length, 25 cm width, and 10 cm height, attached at 120 degrees angles) and an equilateral triangular central area. The protocol has been previously described in our works (40). Each rat was placed at the end of one arm and al-lowed to freely explore the maze for 8 minutes. Spontaneous alternation (consecutive entries into all three arms) was calculated as the ratio of spontaneous alternation entries per total entries.

Elevated plus maze

Based on the natural aversion of rodents for open spaces, anxiety-like behaviors were evaluated using the elevated plus maze consisting of four arms (49 cm long and 10 cm wide) suspended at 50 cm from the ground. Two of the four arms were enclosed by 30 cm high walls, while the other two arms were exposed to the room environment (which was lit by a 60W bulb placed 180 cm above the maze). Following the acclimatization period (1 hour), each rat was gently placed in the central area with its nose facing one of the closed arms and allowed to freely explore the maze for 5 min. The following parameters were recorded: the time spent in open/closed arms, the number of entries in open/closed arms, and certain specific behaviors’ duration (as previously described in Bild & Ciobica, 2013 (41).

Forced swim test

Behavioural despair was evaluated using the adapted forced swim test (42). The animals were individually placed, in a single 6-minute session, into a cylindrical recipient (diameter 30 cm, height 59 cm) containing 25 cm of water at 26 ± 1℃. Following the 2-minute apparatus acclimatization, several behavioral parameters representative for depressive state were evaluated: duration of swimming, immobility (floating), and struggling. Afterwards, the animals were removed from the apparatus, dried, returned to their cages, and kept under observation for 24 hours.

Open-field test

Also based on the natural aversion of rodents for open spaces, the open field was used to measure anxiety-related behavior, in the context of unrestricted movement and exploration in an opened square area (90 × 90 cm) bordered by 40 cm high walls. Each animal was placed in the central square of the open field and several parameters were measured for 5 minutes: locomotor activity (numbers of squares crossed with all four paws), exploratory tendencies (time spent in the central area), and specific behaviors’ duration (stretching, rearing, grooming) (43).

Hot-plate test

The hot-plate test was performed as previously described by (44). The animals were placed on a variable temperature plate enclosed by a cylindrical shape. While all the 4 limbs and tail are simultaneously stimulated by temperature, the reaction time of the first evoked response (hind paw/ tail licking or shaking, tendency to jump, or leave the enclosure) was measured. The latency time of pain reaction at a temperature of 52.5 ± 0.1°C was measured at 30 seconds. The animals were immediately removed from the plate when hind paw licking behavior was observed or no further than 50 seconds, when no behavioral reaction was noted.

Biological samples processing and biochemical assessment

After the biological samples collection, the colon was emptied of all content, washed twice with saline solution, and weighted, as well as collected brain tissues. An enzymatic extract needed in biochemical assessment was prepared using tissue extrac-tion buffer (0.328 g TRIS, 1.304 g KCl2 and distilled water to 200 ml volume, pH = 7.4).

Glutathione peroxidase (GPX Cellular Activity Assay Kit CGP-1, Sigma Aldrich, Germany) specific activities were evaluated using commercial kits and enzymes’ spe-cific activities were calculated by reference to total soluble protein content (Bradford method), as previously described (40).

MDA content was assessed using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARs) determination method, as previously described (45). Trichloroacetic acid (50%, 0.9 mL), thiobarbituric acid (0.73%, 1 mL) and tissue extracts (0.05 mL) were vortexed, incubated for 20 minutes at 100°C, and centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 minutes). The supernatants absorbance was read at 532 nm against an MDA standard curve and the results were expressed as nmol MDA/mL tissue extract.

Statistical analysis

The numerical data obtained by behavioral and biochemical evaluation was sta-tistically analyzed using a specialized statistical analysis software (Minitab 19, UK, 2019). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pearson’s correlation, and Tukey’s honest significance test were performed. All results are expressed as mean ± SEM. F values for which p < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

All the animals that were subjected to the current experimental conditions and evaluation did not suffer any events leading to irreversible neurological or motor damages, illness, or death. At the end of the experiment, the animals’ body weights, water intake, and food intake did not vary significantly between the individuals and groups.

The effects of dietary magnesium intake variation and MPTP administration on the gastrointestinal performances

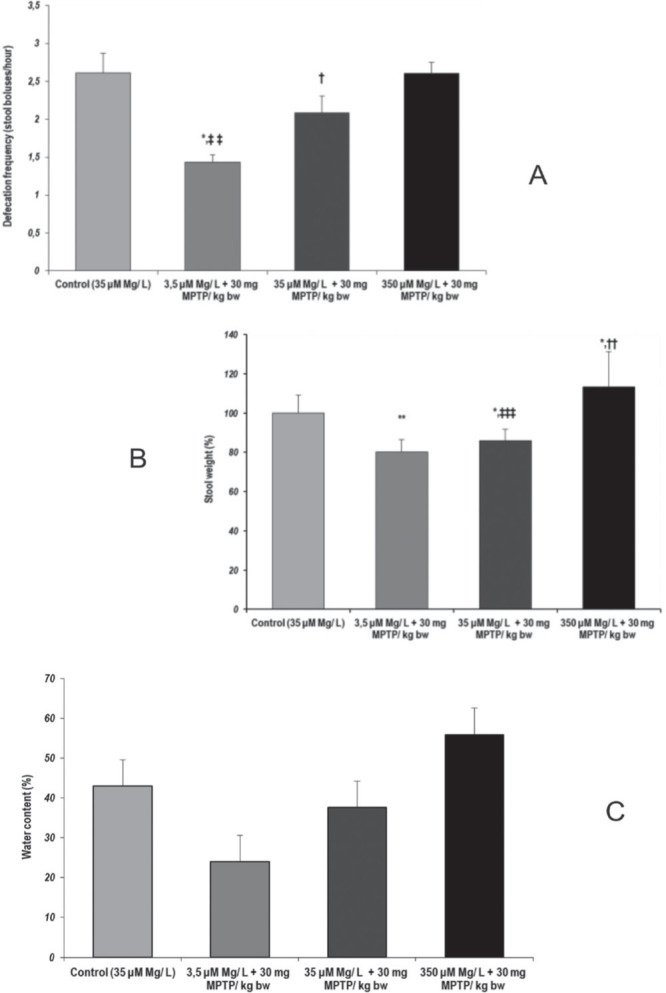

At 8 days following the acute MPTP subcutaneous administration and the 3 weeks of magnesium intake control, in the One-hour Stool Frequency Test we observed that the colon motility was significantly decreased when 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg body weight (bw) were administered (p = 0.012, as compared to control group). Similarly, the stool frequency was also significantly decreased, as compared to the highest magnesium-treated group (p = 0.002, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw) (Fig. 2.a). Furthermore, we observed that low magnesium intake as well as MPTP aggression leads to significantly decreased gastrointestinal performances (Fig. 2.a,b,c).

Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal transit performances, as evaluated by One-hour Stool Collection Test. Parameters: (a) Defecation frequency (fecal boluses/hour); (b) Stool weight (%) (c) Stool water content (%). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3,5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0,05, as compared to control group, **p < 0.01, as compared to control group, †p < 0.05, as compared to 3,5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, ††p < 0.01, as compared to 3,5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, ‡‡p < 0,01, as compared to 350 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, ‡‡‡p < 0.0001, as compared to 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw).

Decreased colon motility and significantly decreased stool weight (p < 0.05, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control) suggested that MPTP could lead to constipation-like functional impairments when normal magnesium intake was provided to the animals (35 µM Mg water). Our data suggested that MPTP could lead to decreased colon motility and significantly decreased stool weight (p = 0.012, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control) (Fig. 2.b).

Similarly, our data on the water content of the stool suggested that magnesium intake could modulate water intestinal reabsorption, but not in a significant manner. Consequently, the visual inspection of the stool boluses revealed normal aspect and few semi-solid stools in increased magnesium intake MPTP-treated group (350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw). However, in the first part of the 3-week increased magnesium intake we observed semisolid and watery stools for up to the first 3 days, suggesting a transient change as a result to diet change.

The effects of dietary magnesium intake variation and MPTP administration on the be-havioral parameters

Short-term memory performances

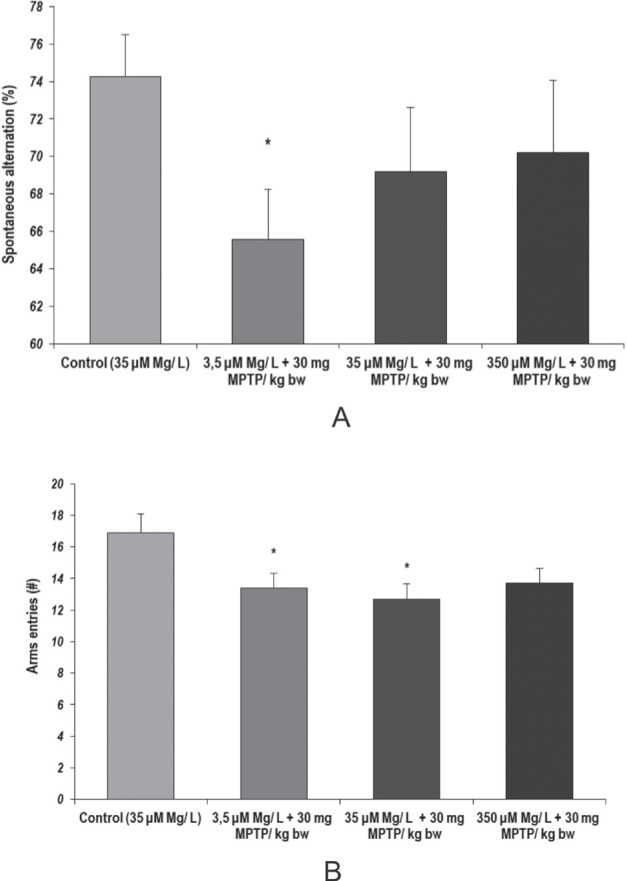

Regarding the immediate working memory evaluated by Y maze task, our results suggested that low magnesium intake and MPTP acute treatment could lead to significantly decreased spontaneous alternation (%), as compared to the normal magnesium intake (p = 0.018, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, versus control) (Fig. 3.a). Also, we observed that MPTP acute treatment could lead to short-term memory impairment, but not in a significant manner (p = 0.016, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control). Overall locomotor activity was significantly decreased following MPTP treatment in low and normal magnesium intake, as compared to the control group (3.5 µM Mg + 30 mg MPTP, p = 0.018; 35 µM Mg + 30 mg MPTP, p= 0.01) (Fig. 3.b).

Figure 3.

Short-term memory performances, as evaluated by Y maze test. Behavioural parameters: (a) Spontaneous alternation; (b) Locomotor activity. Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0.05, as compared to control group).

Anxiety and exploratory behavior

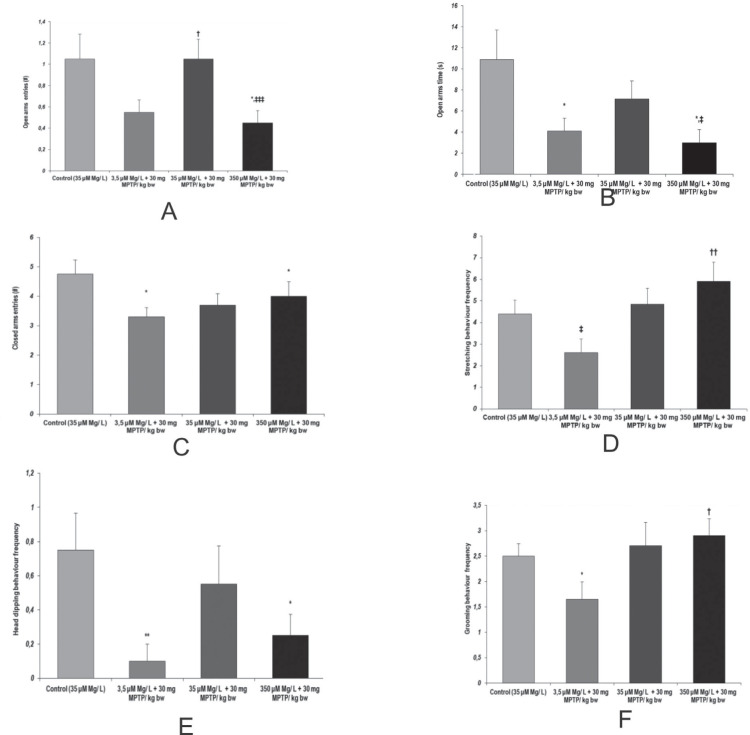

In the elevated plus maze task, several behavioral patterns suggested that magnesium intake could set the faith of MPTP effect on anxiety-like behavior manifestation. In this way, increased anxiety-like behaviors and decreased exploratory tendencies were observed following MPTP acute treatment when low and high magnesium intake was provided to the animals, as compared to normal magnesium intake groups, as seen in the evaluation of most of the anxiety-like relevant parameters: open arms time, stretching behavior frequency, and head dipping behavior frequency (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Anxiety-like behavior assessment, as observed in Elevated plus maze. Behavioral parameters: (a) Open arms entries (no.); (b) Open arms time (s); (c) Closed arms entries (no.); (d) Stretching behavior frequency; (e) Head dipping behavior frequency; (f) Grooming behavior frequency. Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3,5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0.05, as compared to control; **p < 0.01, as compared to control; †p < 0,05, as compared to 3,5 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ††p < 0,01, as compared to 3,5 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ‡p < 0.05, as compared to 35 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ‡‡‡p < 0.001, as compared to 35 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw).

The main anxiolytic behavior exhibited naturally by rodents, grooming, was significantly decreased following MPTP aggression in low magnesium intake animals (p = 0.05, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control group) as well as by compared to increased magnesium intake for which the MPTP anxiogenic effect was thwarted by the biometal increased bioavailability (p = 0.05, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw) (Fig. 4.e).

The relevant parameters (opened and closed arms entries) revealed that magnesium intake could modulate MPTP aggression effects on locomotor activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4.a,c).

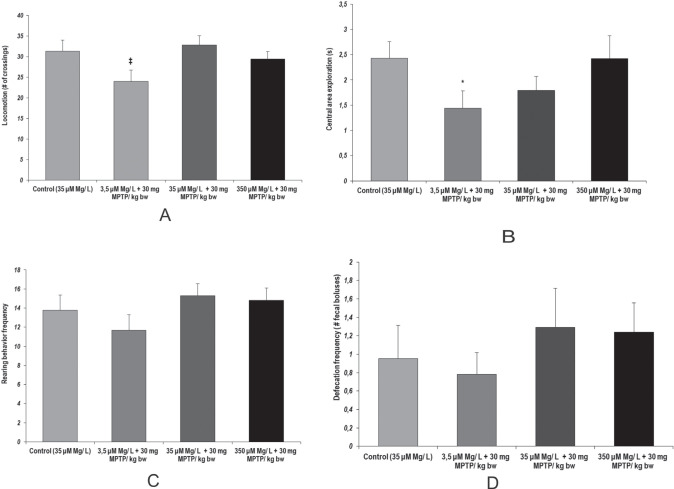

We observed similar patterns of locomotor activity in the open-field task, by relation to low intake magnesium following MPTP acute treatment (p = 0.018, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw) (Fig. 5.a). When considering the time spent in the center of the apparatus as a marker suggestive for behavioral anxiety, we observed that MPTP aggression lead to significant anxiety-like behavior when low magnesium intake was provided to the animals (p = 0.04 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control) (Fig. 5.b). Despite that, no significant changes were observed for the other behaviors observed in open field task and relevant for anxiety status evaluation (stretching behavior, grooming behavior) (Fig. 5.c).

Figure 5.

Locomotor activity and anxiety-like behavior in spatial exploration, as observed in Open field test. Behavioral parameters: (a) Locomotor activity (no. of crossings); (b) Central area exploration (s); (c) Rearing behavior frequency; (d) Defecation frequency (no. of fecal boluses). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3,5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0,05, as compared to control group; ‡p < 0.05, as compared to 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw).

Yet it is worth mentioning one important aspect regarding the defecation frequency in open arms task relevant to affective behavior, as well as gastrointestinal status. Despite that no statistically significant differences were noted, we observed that MPTP acute treatment tended to provoke more defecation episodes in normal and high magnesium intake groups (as seen in Fig. 5.d).

Depressive manifestations

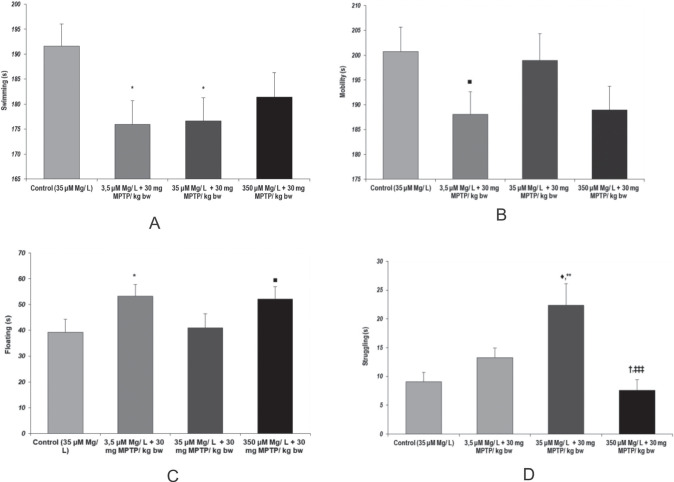

During behavioral analysis using Forced Swimming Task, we found significant differences, suggesting that both MPTP aggression and magnesium intake could modulate depressive-like behavior manifestations. Immobility or floating time as behavioral markers of behavioral despair were significantly increased when MPTP was administered in low magnesium intake conditions, as compared to control group (p = 0.043, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control) (Fig. 6.c). Similar behavioral tendencies were observed when the neuroaggresant was administered to the animals in high magnesium intake conditions (p = 0.06, 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control).

Figure 6.

Behavioral dispair, as observed in Forced swimming test. Brahvioral parameters: (a) Swimming time (s); (b) Mobility time (s); (c) Floating time (s); (d) Struggling time (s). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0,05, as compared to control; †p < 0.05, as compared to 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ‡‡p < 0.001, as compared to 35 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ‡‡‡p = 0.06, as compared to 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; ■p = 0.06, as compared to control).

Our observation suggesting that MPTP could cause anxiety-like behavior was once again backed out by the struggling behavior patterns. In consequence, we found that 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw group showed significantly increased struggling behavior times, as compared to control group (p = 0.001). Also, we observed that magnesium intake could potentiate MPTP effect as both low and high magnesium intake were found to significantly decrease struggling behavior induced by MPTP ad-ministration ( p = 0.018, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw; p = 0.0009, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw) (Fig. 6.d).

As a measure of locomotor activity, the total swimming time was found significantly reduced in the 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, as compared to control group suggesting that MPTP acute treatment could impair locomotion (p = 0.023 vs. control). Also, this tendency was even more visible when low magnesium intake was provided to the MPTP-treated animals (p = 0.019, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control) (Fig. 6.a). Although not statistically significant, the MPTP – magnesium interaction in terms of locomotor activity modulation could be seen in mobility time tendencies (Figure 6.b).

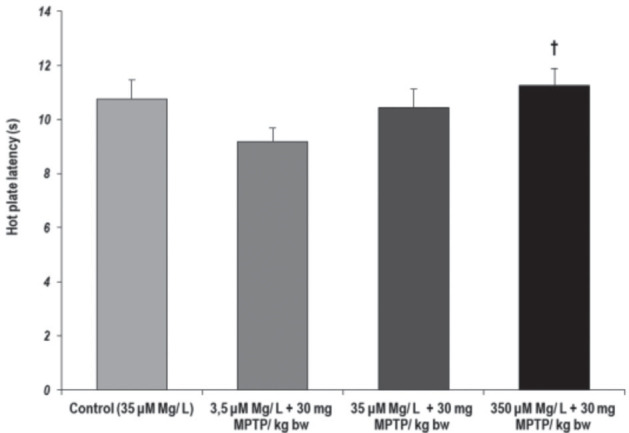

Pain tolerance

Regarding the animals response to pain by relation to MPTP administration and magnesium intake modulation, as evaluated by the hot-plate test, we observed that the latency time reflecting the onset of heat sensitivity was significantly decreased when MPTP was administered to animals with low magnesium intake conditions, as compared to high magnesium intake conditions (p = 0.015, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw) (Fig. 7). Statistical analyses of the data revealed that latency time and stretching and grooming behaviors were correlated (p < 0.05, Pearson’s correlation).

Figure 7.

Tolerance to pain, as observed in Hot-plate test. Behavioral parameter: latency time (s). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, n = 25; †p < 0.05, as compared to 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw).

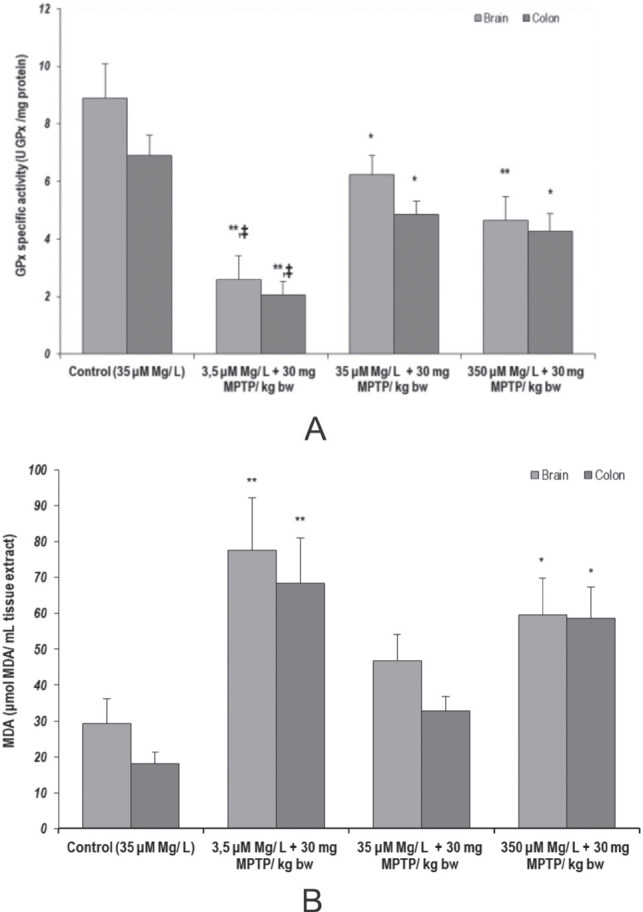

The effects of dietary magnesium intake variation and MPTP administration on some brain and colon oxidative stress biomarkers

Significant tendencies, suggestive for oxidative stress manifestations in both brain and colon samples were found when GPx antioxidant enzymatic activity and total MDA content were evaluated. Therefore, we observed that GPx antioxidant enzyme activity was significantly decreased following MPTP aggression, in normal magnesium intake conditions (p < 0.05, 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control, in both tissues). However, high magnesium intake was not able to reverse this effect (p < 0.01, 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control, in brain samples, and p < 0.05, 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control, in colon samples). Moreover, we observed that low magnesium intake could potentiate MPTP effects on GPx antioxidant activity (p < 0.05, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus 35 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw, in both tissues) (Fig. 8.a).

Figure 8.

Effects of MPTP and dietary Mg intervention on oxidative stress parameters: (a) GPx enzyme activity in rat brain and colon tissue (U GPx/ mg protein); (b) MDA content in rat brain and colon tissue (µmol MDA/ mL tissue extract). Results are expressed as means ± SEM (Control, n = 23; 3.5 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw; n = 25; 35 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 22; 350 μM Mg/ L water + 30 mg MPTP/kg bw, n = 25; *p < 0,05, as compared to control, same tissue; **p < 0.01, as compared to control, same tissue; ‡p < 0.05, as compared to 35 μM Mg/ L + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw).

Also, we found significantly increased MDA content in both brain and colon samples of the animals treated with MPTP provided with low and high magnesium enriched water (p < 0.01, 3.5 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control; p < 0.05, 350 µM Mg water + 30 mg MPTP/ kg bw versus control, in both tissues) (Fig. 8.b) suggesting that magnesium could modulate lipid peroxidation when MPTP pro-oxidant agent is administered to the animals.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we aimed to bring additional evidence concerning the potential of magnesium to modulate MPTP neurotoxicity and gastrointestinal toxicity in a rat model. The implication of magnesium in the metabolic pathways and neuroprotection was thoroughly described and many key cellular processes were found to directly or indirectly depend on the magnesium bioavailability (10-12). Moreover, many reports described magnesium deficit as a potent promoter of many neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions including Alzheimer’s disease, PD, depression, and anxiety (10). For instance, the main mechanism in which magnesium could modulate depressive-like behavior is closely tied to the monoaminergic system unbalance (13). Thus, also our data can endorse this potential mechanism as we showed that the cognitive defects caused by the MPTP aggression mainly refer to the occurrence of anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, in a magnesium dose-dependent manner.

Regarding the hallmark of the PD animal models, we observed that the subcutaneous acute MPTP administration (30 mg/kg bw) could lead to motor impairments, such as decreased locomotor activity, typically seen in PD models. As it can be observed in the behavioral evaluation results (Figures 2a, 3b, 5a), our MPTP rat model exhibits impaired locomotor activity, suggested by decreased exploratory behavior in Y task and elevated plus maze task and decreased active swimming behavior in forced swim task. These results are reproducing the intraperitoneal-administered MPTP effects in mice (as reviewed by (20)) and also Perry et al. (21) that tested behavioral effects of phosphatidylserine following intranigral infusion of MPTP in rats. Meredith et al. (20) suggested that repeated intraperitoneal and subcutaneous MPTP injections could successfully mimic PD in rodent models, but with much lesser extent in rats for which direct administration is preferred (cerebral perfusion). This limitation was later overcome by nasal (6) or direct (stereotaxic injection) administration (22-25) and MPTP was reported to cause dopaminergic neurodegeneration, mild motor effects, and spatial working memory impairment reminiscent of PD pathology (3, 22, 26).

Reasonable evidence showed that MPP+ could cause dopaminergic neurodegeneration in primates or mice (27). However, more recent studies suggested the incomplete MPTP vascular breakdown since both intravenous and intraperitoneal injections of MPTP were used to successfully model PD in Sprague–Dawley rats (28, 29). In this way, Kim et al. (28) used subchronic intraperitoneal 20 mg MPTP/ kg bw treatment to obtain significantly decreased mitochondrial complex I activity in the substantia nigra and decreased catecholamine-responsive neurons. Similarly, Siow et al. (29) reported that a single intravenous MPTP (15 mg/kg) could be sufficient to induce oxidative stress-mediated progressive cerebral blood flow in the cortex and striatum of rats.

By relation to MPTP, magnesium modulatory potential could refer to neuroprotection against MPTP aggression (14, 15, 30). For instance, Tariq et al. (14) demonstrated that either lower or higher doses of magnesium produced opposite effects in terms of motor activity and nociception in MPTP-injected animals. At the same time, a magnesium-deficient diet has been reported to increase susceptibility to MPTP neurotoxicity in mice even at low doses of 10 mg/ kg that would otherwise be safe (15). Thus, magnesium-deficient mice showed decrease of striatal dopamine level by MPTP, and also increased anxiety- and depression-like behaviors (15). In our experimental design, the most pronounced anxiety and depressive-like manifestations were observed when ad-ministering MPTP following low magnesium intake. Decreased exploratory behaviors in the elevated and open field tests and increased floating duration in the forced swim test, as compared to MPTP treatment in normal magnesium diet, suggested that magnesium could possess neuroprotective properties. As it was previously described that magnesium is directly implicated in the monoamine oxidase system, it could be possible that the low bioavailability of magnesium prevented the monoamine oxidase B activity. Moreover, the stretching and grooming behaviors correlation could reduce no-ciceptive hypersensitivity coupled with the decreased exploratory and self-reassuring behaviors in the magnesium deficient rats. Also, the fact that normal magnesium in-take prevented a fulminant affective behavior impairment following MPTP aggression could suggest the direct implication of chronic magnesium deficit in altered affective behavior, as described by Kirkland et al. (10) and Botturi et al. (31) in a recent meta-analysis regarding magnesium deficit in affective disorders.

On the other hand, when MPTP aggression occurred following high magnesium intake, the MPTP effects on the rats behavior were quite similar to the low magnesium intake experimental conditions. In this way, the effects were represented by frequent anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors manifestations and no significant improvement of short-term memory performance, when compared to the control group – as reported by Tariq et al. (14). The same group (14) also noted that a paradoxical dual interaction between magnesium and MPTP - low magnesium background leading to increased motor activity, whereas normal and high magnesium intakes provided good backgrounds for MPTP specific effects (locomotor deficits and affective impairment).

Despite that previous reports suggesting that PD-like neurobehavioral effects of MPTP in rats are efficiently prevented by the peculiar activity of brain microvessels monoamine oxidase B system which breaks MPTP molecules before passing through blood-brain barrier (3), we found that the MPTP neurotoxicity is not fully inhibited in rats, but also extended to other systems, such as the gastrointestinal tract (32-35). Previous reports showed that most of the gastrointestinal effects were not linked to MPTP conversion to MPP+. In this way, intraperitoneal MPTP administration in mice was reported to cause chronic delayed transit and constipation, suggesting peripheral toxicity, catecholaminergic damage (9, 33, 35), and lesions in the myenteric and submuco-sal plexus dopaminergic neurons and presynaptic glutamate receptors (33). Striatal dopamine reduction-modulated systemic and liver inflammation, as well as depressive behavior, were reported in rats following MPTP repeated nasal administration (7). Several reports of MPTP mice models also described altered peripheral pain response conducive to central mediated effects as well as to defects along the spinal cord (36, 37).

In this context, our results showed that MPTP aggression could lead to constipation-like gastrointestinal effects, as shown in the One-hour Stool Collection Test by the decreased defecation frequency, stool weight, and stool water content (Fig. 1). These results could suggest several differences between the gastrointestinal status by relation to MPTP and also with magnesium bioavailability. Also, if the tendencies observed in the defecation frequency evaluated in the open field task would be corroborated with the data obtained within the One-hour Stool Frequency Test, it could suggest that mild functional constipation-like gastrointestinal transit tendencies could be observed for MPTP treatment in low magnesium intake conditions and mild diarrhea-like tendencies when MPTP is administered in normal or high magnesium intake conditions. Thus, it could suggest that MPTP gastrointestinal effects could be correlated with magnesium availability though dietary intake. Moreover, we observed that MPTP-treated animals manifested low pain tolerance, another key feature of PD. Many types of pain manifestations were previously described in PD patients, including visceral hypersensitivity (38, 39). This could suggest that MPTP gastrointestinal effects could also target pain perception and response.

On the other hand, there is extensive data describing magnesium role as an osmotic laxative in treating functional constipation and increasing frequency of bowel movements (16, 17, 25), while hypomagnesemia induced by low dietary magnesium in mice was found to be associated with high production of organic acids, such as formic acid, subsequent proinflammatory environment, and disturbed gut internal microflora (18,19), all impacting gut motility. In our experimental conditions, we also could describe the modulatory potential of magnesium in MPTP-induced constipation. Hence, we showed that low magnesium intake could potentiate MPTP gastrointestinal effects as well as pain intolerance.

Previous studies reported that MPTP toxicity could also be seen in the brain tissues as increased oxidative stress (4, 40). Additional evidence supporting this observation could be brought by our results regarding the oxidative status of the evaluated animals’ brains.

Regarding the limitations of our study we can mention that there is no measurement on the amount of drinking water for rats or any measure for the content of magnesium in blood, due to technical limitations. Still, our results do suggest that the patterns seen in brain oxidative stress could also be seen in the intestinal tissues. However, in normal magnesium intake conditions, we were able to detect significant oxidative stress damage (as suggested by lipid peroxidation levels) in the intestinal tissues samples, but not in the brain samples (Fig. 7).

In summary, our results suggested that peripheral administration of MPTP in rats could lead to some toxic neuroendocrine effects, as well as possible gastrointestinal impairments, and central and peripheral oxidative stress. Despite the limitations of our study, it is important to note that our results suggest that magnesium could be implicated in the modulation of MPTP effects in rats. This aspect was previously showed in a MPTP mice model (15). Also, Wei et al. (46) and Pan et al. (47) recently showed that both magnesium and MPTP could lead to oxidative stress and gastrointestinal impairments. Thus, due to the interaction that it was seen between MPTP and magnesium in magnesium deficient animal models, this metal ion could be a part of both etiologic and therapeutic arguments of Parkinson’s disease (15).

If MPTP, a neurotoxin that mimics Parkinson’s disease symptoms (48), worsens the effects of low magnesium intake, which also has been associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (49), this may suggest that individuals with both factors may be at an even higher risk of developing the disease. This may be of particular significance for clinicians to consider magnesium status for treatment plan for individuals with Parkinson’s disease.

Our data suggest that MPTP exposure can be associated, besides the well-known central neurotoxic effects, with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as constipation and altered gut motility. These disturbances may be related to a potential alteration of dopaminergic neurons in the enteric nervous system, which play a role in regulating gut function (50). If that is the case, MPTP effects in the periphery could be very important to the overall pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. While the interactions between magnesium and peripheral dopamine are not fully understood, magnesium is a cofactor along dopamine synthesis pathway (51), which could indicate that low magnesium levels can also potentially impact dopamine production.

In conclusion, despite that one of the main effects of MPTP refers to neuronal toxicity, it was showed that it could also determine gastrointestinal motility changes. In both cases, magnesium is a key modulator that could influence the response to MPTP aggression. The current study brought additional evidence on the neuronal and extraneuronal effects of MPTP, as well as on this implication of magnesium in MPTP effects modulation. While the MPTP effects in normal magnesium intake could be regarded as not fully relevant in rat models and limited to the current experimental conditions, the abnormalities observed in the affective behavior, gastrointestinal status, pain tolerance, peripheric and central oxidative status could be indicative of the extent of the systemic effects of MPTP that are not restricted to the CNS level, but also to gastrointestinal system.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Dr. Kolisek from Freie University in Berlin, for providing the magnesium-depleted food and for the valuable scientific advice regarding the experimental design.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

The animals were treated in accordance with the guidelines of animal bioethics from Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (no. USAMV Iasi 385/04.04.2019) and efforts were made to minimize the effectives’ sizes and animals suffering.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon request.

References

- 1.Kin K, Yasuhara T, Kameda M, Date I. Animal Models for Parkinson’s Disease Research: Trends in the 2000s. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5402. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaker EY, Bixler GB, Dunn AJ, Moreshead WV, Mathias JR. Chronic alterations in jejunal myoelectric activity in rats due to MPTP. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(6 Pt 1):G809–815. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.253.6.G809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riachi NJ, Dietrich WD, Harik SI. Effects of internal carotid administration of MPTP on rat brain and blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 1990;533(1):6–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91788-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres ERS, Akinyeke T, Stagaman K, Duvoisin RM, Meshul CK, Sharpton TJ, Raber J. Effects of Sub-Chronic MPTP Exposure on Behavioral and Cognitive Performance and the Microbiome of Wild-Type and mGlu8 Knockout Female and Male Mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:140. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai F, Jiang R, Xie W, Liu X, Tang Y, Xiao H, Gao J, Jia Y, Bai Q. Intestinal Pathology and Gut Microbiota Alterations in a Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem Res. 2018;43(10):1986–1999. doi: 10.1007/s11064-018-2620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie W, Gao J, Jiang R, Liu X, Lai F, Tang Y, Xiao H, Jia Y, Bai Q. Twice subacute MPTP administrations induced time-dependent dopaminergic neurodegeneration and inflammation in midbrain and ileum, as well as gut microbiota disorders in PD mice. Neurotoxicology. 2020;76:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta I, Mekha SR, Kaushal A, Ganapathy K, Razdan R. Influence of intranasal exposure of MPTP in multiple doses on liver functions and transition from non-motor to motor symptoms in a rat PD model. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2020;393(2):147–165. doi: 10.1007/s00210-019-01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangla JC, Pihan G, Brown HA, Rattan S, Szabo S. Effect of duodenal ulcerogens cysteamine, mepirizole, and MPTP on duodenal myoelectric activity in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34(4):537–542. doi: 10.1007/BF01536329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haskel Y, Hanani M. Inhibition of gastrointestinal motility by MPTP via adrenergic and dopaminergic mechanisms. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(11):2364–2367. doi: 10.1007/BF02087652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolisek M, Touyz RM, Romani A, Barbagallo M. Magnesium and Other Biometals in Oxidative Medicine and Redox Biology. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:7428796. doi: 10.1155/2017/7428796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolisek M, Schweyen R.J, Schweigel M. (2007). Cellular Mg2+ Transport and Homeostasis: An Overview. In: Nishizawa Y, Morii H, Durlach J, editors. New Perspectives in Magnesium Research. London: Springer; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso CC, Lobato KR, Binfaré RW, Ferreira PK, Rosa AO, Santos AR, Rodrigues AL. Evidence for the involvement of the monoaminergic system in the antidepressant-like effect of magnesium. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tariq M, Khan HA, Moutaery KA, Deeb SMA. Effect of Chronic Administration of Magnesium Sulfate on 1–Methyl–4–phenyl–1,2,3,6–tetrahydropyridine–Induced Neurotoxicity in Mice. Pharmacol & Toxicol. 1998;82:218–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muroyama A, Inaka M, Matsushima H, Sugino H, Marunaka Y, Mitsumoto Y. Enhanced susceptibility to MPTP neurotoxicity in magnesium-deficient C57BL/6N mice. Neurosci Res. 2009;63(1):72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saneian H, Mostofizadeh N. Comparing the efficacy of polyethylene glycol (PEG), magnesium hydroxide and lactulose in treatment of functional constipation in children. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:S145–S149. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morishita D, Tomita T, Mori S, Kimura T, Oshima T, Fukui H, Miwa H. Senna Versus Magnesium Oxide for the Treatment of Chronic Constipation: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):152–161. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gommers LMM, Ederveen THA, van der Wijst J, Overmars-Bos C, Kortman GAM, Boekhorst J, Bindels RJM, de Baaij JHF, Hoenderop JGJ. Low gut microbiota diversity and dietary magnesium intake are associated with the development of PPI-induced hypomagnesemia. FASEB J. 2019;33(10):11235–11246. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900839R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scanlan BJ, Tuft B, Elfrey JE, Smith A, Zhao A, Morimoto M, Chmielinska JJ, Tejero-Taldo MI, Mak IuT, Weglicki WB, Shea-Donohue T. Intestinal inflammation caused by magnesium deficiency alters basal and oxidative stress-induced intestinal function. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;306(1-2):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9554-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meredith GE, Rademacher DJ. MPTP mouse models of Parkinson’s disease: an update. J Parkinsons Dis. 2011;1(1):19–33. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry JC, Da Cunha C, Anselmo-Franci J, Andreatini R, Miyoshi E, Tufik S, Vital MA. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of phosphatidylserine in MPTP lesion of the substantia nigra of rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;484(2-3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferro MM, Bellissimo MI, Anselmo-Franci JA, Angellucci ME, Canteras NS, Da Cunha C. Comparison of bilaterally 6-OHDA-and MPTP-lesioned rats as models of the early phase of Parkinson’s disease: histological, neurochemical, motor and memory alterations. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;148(1):78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gevaerd MS, Takahashi RN, Silveira R, Da Cunha C. Caffeine reverses the memory disruption induced by intra-nigral MPTP-injection in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55(1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho SC, Hsu CC, Pawlak CR, Tikhonova MA, Lai TJ, Amstislavskaya TG, Ho YJ. Effects of ceftriaxone on the behavioral and neuronal changes in an MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease rat model. Behav Brain Res. 2014;268:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu CL, Qu R, Zhang J, Li LF, Ma SP. Neuroprotective effects of madecassoside in early stage of Parkinson’s disease induced by MPTP in rats. Fitoterapia. 2013;90:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schober A. Classic toxin-induced animal models of Parkinson’s disease: 6-OHDA and MPTP. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eaker EY, Bixler GB, Dunn AJ, Moreshead WV, Mathias JR. Chronic alterations in jejunal myoelectric activity in rats due to MPTP. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(6 Pt 1):G809–815. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.253.6.G809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DH, Choi JJ, Park BJ. Herbal medicine (Hepad) prevents dopaminergic neuronal death in the rat MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Integr Med Res. 2019;8(3):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siow TY, Chen CC, Wan N, Chow KP, Chang C. In vivo evidence of increased nNOS activity in acute MPTP neurotoxicity: a functional pharmacological MRI study. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:964034. doi: 10.1155/2013/964034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto T, Nishi K, Nagasao J, Tsuji S, Oyanagi K. Magnesium exerts both preventive and ameliorating effects in an in vitro rat Parkinson disease model involving 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) toxicity in dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res. 2008;1197:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botturi A, Ciappolino V, Delvecchio G, Boscutti A, Viscardi B, Brambilla P. The Role and the Effect of Magnesium in Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1661. doi: 10.3390/nu12061661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangla JC, Pihan G, Brown HA, Rattan S, Szabo S. Effect of duodenal ulcerogens cysteamine, mepirizole, and MPTP on duodenal myoelectric activity in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34(4):537–542. doi: 10.1007/BF01536329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natale G, Kastsiushenka O, Fulceri F, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, Fornai F. MPTP-induced parkinsonism extends to a subclass of TH-positive neurons in the gut. Brain Res. 2010;1355:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pileblad E, Carlsson A. Studies on the acute and long-term changes in dopamine and noradrenaline metabolism in mouse brain following administration of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Pharmacol Toxicol. 1988;62(4):213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1988.tb01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biagioni F, Vivacqua G, Lazzeri G, Ferese R, Iannacone S, Onori P, Morini S, D’Este L, Fornai F. Chronic MPTP in Mice Damage-specific Neuronal Phenotypes within Dorsal Laminae of the Spinal Cord. Neurotox Res. 2021;39(2):156–169. doi: 10.1007/s12640-020-00313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J, Lim CS, Seo H, Park CA, Zhuo M, Kaang BK, Lee K. Pain perception in acute model mice of Parkinson’s disease induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Mol Pain. 2015;11:28. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0026-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skjærbæk C, Knudsen K, Horsager J, Borghammer P. Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):493. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roversi K, Callai-Silva N, Roversi K, Griffith M, Boutopoulos C, Prediger RD, Talbot S. Neuro-Immunity and Gut Dysbiosis Drive Parkinson’s Disease-Induced Pain. Front Immunol. 2021;12:759679. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.759679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori H, Tack J, Suzuki H. Magnesium Oxide in Constipation. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):421. doi: 10.3390/nu13020421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cojocariu RO, Balmus IM, Lefter R, Ababei DC, Ciobica A, Hritcu L, Kamal F, Doroftei B. Behavioral and Oxidative Stress Changes in Mice Subjected to Combinations of Multiple Stressors Relevant to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):865. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10110865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bild W, Ciobica A. Angiotensin-(1-7) central administration induces anxiolytic-like effects in elevated plus maze and decreased oxidative stress in the amygdala. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campos MM, Fernandes ES, Ferreira J, Santos ARS, Calixto JB. Antidepressant-like effects of Trichilia catigua (Catuaba) extract: evidence for dopaminergic-mediated mechanisms. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;182:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanford SC. The Open Field Test: Reinventing the Wheel. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;21(2):134–134. doi: 10.1177/0269881107073199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunn A, Bobeck EN, Weber C, Morgan MM. The influence of non-nociceptive factors on hot-plate latency in rats. J Pain. 2011;12(2):222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciobica A, Olteanu Z, Padurariu M, Hritcu L. The effects of pergolide on memory and oxidative stress in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Physiol Biochem. 2012;68(1):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei SP, Jiang WD, Wu P, Liu Y, Zeng YY, Jiang J, Kuang SY, Tang L, Zhang YA, Zhou XQ, Feng L. Dietary magnesium deficiency impaired intestinal structural integrity in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12705. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei SP, Jiang WD, Wu P, Liu Y, Zeng YY, Jiang J, Kuang SY, Tang L, Zhang YA, Zhou XQ, Feng L. Dietary magnesium deficiency impaired intestinal structural integrity in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12705. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sian J, Youdim MBH, Riederer P, Gerlach M. MPTP-Induced Parkinsonian Syndrome. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oyanagi K, Hashimoto T. Magnesium in Parkinson’s disease: an update in clinical and basic aspects. In: Vink R, Nechifor M, editors. Magnesium in the Central Nervous System. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li ZS, Schmauss C, Cuenca A, Ratcliffe E, Gershon MD. Physiological modulation of intestinal motility by enteric dopaminergic neurons and the D2 receptor: analysis of dopamine receptor expression, location, development, and function in wild-type and knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26(10):2798–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4720-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winther G, Pyndt Jørgensen BM, Elfving B, Nielsen DS, Kihl P, Lund S, Sørensen DB, Wegener G. Dietary magnesium deficiency alters gut microbiota and leads to depressive-like behaviour. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015;27(3):168–176. doi: 10.1017/neu.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon request.