Abstract

Background

The incorporation of exogenous fatty acids into the cell membrane yields structural modifications that directly influence membrane phospholipid composition and indirectly contribute to virulence. FadL and FadD are responsible for importing and activating exogenous fatty acids, while acyltransferases (PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, PlsY) incorporate fatty acids into the cell membrane. Many Gammaproteobacteria species possess multiple homologs of these proteins involved in exogenous fatty acid metabolism, suggesting the evolutionary acquisition and maintenance of this transport pathway.

Methods

This study developed phylogenetic trees based on amino acid and nucleotide sequences of homologs of FadL, FadD, PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY via Mr. Bayes and RAxML algorithms. We also explored the operon arrangement of genes encoding for FadL. Additionally, FadL homologs were modeled via SWISS-MODEL, validated and refined by SAVES, Galaxy Refine, and GROMACS, and docked with fatty acids via AutoDock Vina. Resulting affinities were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA test and Tukey's post-hoc test.

Results

Our phylogenetic trees revealed grouping based on operon structure, original homolog blasted from, and order of the homolog, suggesting a more ancestral origin of the multiple homolog phenomena. Our molecular docking simulations indicated a similar binding pattern for the fatty acids between the different FadL homologs.

General significance

Our study is the first to illustrate the phylogeny of these proteins and to investigate the binding of various FadL homologs across orders with fatty acids. This study helps unravel the mystery surrounding these proteins and presents topics for future research.

Keywords: Exogenous fatty acids, Fatty acid metabolism, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacterial phylogeny, Molecular docking, FadL

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Homologs cluster based on base sequence used to blast, operon structure, and order.

-

•

Phylograms suggest more ancestral origin of multiple homolog phenomena.

-

•

FadL homologs had differential profile of binding affinities with fatty acids.

-

•

Molecular docking results suggest the role of FadL is critical, necessitating multiple homologs to ensure function.

1. Introduction

1.1. Gammaproteobacteria and exogenous fatty acids

Fatty acids are often part of the major molecular group of lipids. Fatty acids on their own have many cellular functions, including serving as structural elements, constituting energy reserves, and acting as signaling molecules. Among these roles is the composition of the phospholipids in the cell membrane. Fatty acids can be obtained either by native synthesis (de novo) or uptake of exogenous fatty acids [1]. Many proteins are involved in both of these processes. In particular, this study aims to investigate proteins involved in the latter process, the uptake of exogenous fatty acids, specifically in Gammaproteobacteria, a class of the gram-negative phylum Pseudomonadota (also known as Proteobacteria).

Many gram-negative bacteria are found within the phylum Proteobacteria. This phylum consists of multiple classes including Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria [2]. The class Gammaproteobacteria is defined by a relationship in the 16S rRNA gene sequences [3]. Gammaproteobacteria contains many pathogens, such as several Vibrio species (cholerae, parahaemolyticus, vulnificus, and alginolyticus), Allivibrio ficheri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the model bacterial organism Escherichia coli [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]. Many members of this class, including all the aforementioned species, are able to incorporate exogenous fatty acids, including polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), into the phospholipids of their membranes [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Such assimilation results in phospholipid structural modifications, causing increased membrane permeability to hydrophobic compounds and altered resistance to certain antibiotics. The PUFAs also act like signaling molecules affecting bacterial behavior, including biofilm formation and swimming motility. These responses are particularly interesting due to the link between some of these phenotypes and virulence [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8]].

1.2. Pathway for exogenous fatty acid incorporation into membrane phospholipids

All gram-negative bacteria possess an asymmetrical outer membrane composed of lipopolysaccharide-containing outer leaflet and a phospholipid-containing inner leaflet and a symmetrical inner membrane phospholipid bilayer [13]. The pathway for fatty acid incorporation into the membrane is summarized in Fig. 1. Exogenous long chain fatty acids first enter the cell by crossing the outer membrane via FadL, the long-chain fatty acid transporter [6]. FadL is an outer membrane transporter, which recognizes and transports exogenous fatty acids across the outer membrane [5,14]. Fatty acids travel through the periplasm and into the inner membrane where they are activated by FadD, an acyl-CoA synthetase, with the addition of a coenzyme A group, designating them for i) degradation to provide energy and carbon for bacterial growth via beta oxidation or ii) incorporation into phospholipids via acyltransferases, PlsB and PlsC. PlsB and PlsC, which are both integral membrane proteins, facilitate the transesterification of fatty acids to the 1- and 2-positions of glycerol-3-phosphate, respectively, resulting in phosphatidic acid [15,16]. Phosphatidic acid is an intermediate in the production of glycerophospholipids which compose the membrane, i.e. exogenous fatty acids comprising phosphatidic acid are eventually incorporated into the membrane. The PlsB/PlsC pathway can also be utilized to incorporate de novo fatty acids, in the acyl-ACP form, into the membrane [15].

Fig. 1.

Fatty Acid Metabolism. The red arrows represent the pathway for exogenous fatty acids. The blue arrows represent the pathway for de novo synthesized fatty acids. The black arrow represents the part of the pathway shared by both exogenous fatty acids and de novo synthesized fatty acids. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

This PlsB/PlsC pathway was initially studied in E. coli and thought to be present in all bacteria. However, later research revealed that PlsB is not found in many bacteria [15,16]. An alternate pathway involves PlsX and PlsY, along with PlsC. Like PlsB, PlsY is also an acyltransferase and an integral membrane protein [16]. However, unlike PlsB which uses both acyl-ACP (for de novo fatty acids) and acyl-CoA (for exogenous fatty acids), PlsY is unable to use either and instead uses acyl-PO4. PlsX enables the function of PlsY by conversion of acyl-ACP (not acyl-CoA) into acyl-PO4. PlsY and later PlsC perform transesterification to add the fatty acids to glycerol-3-phosphate, resulting in phosphatidic acid which is eventually incorporated into the membrane. While in theory this pathway serves the same function as the PlsB/PlsC pathway, many species have both the PlsB/PlsC pathway and the PlsX/PlsY/PlsC pathway, including Gammaproteobacteria orders Vibrionales, Enterobacterales, Alteromonadales, Pasteurellales, and Pseudomonades [15,16]. Studies on E. coli showed that a mutant with double knockout of both PlsX and PlsY was not viable, although mutants with single knockout of PlsX and PlsY were successful and showed no negative effect in terms of growth [17]. Thus, the reason behind the retainment of both these pathways in some species remains unclear.

1.3. Study aims

This study focuses specifically on the class Gammaproteobacteria, which i) is one of the broadest taxa containing more genera than most bacterial phyla [3] and ii) is one of the main classes containing many species retaining both PlsB/PlsC and PlsX/PlsY/PlsC pathways [16]. While phylogenetic studies of Gammaproteobacteria exist, the literature lacks specific phylogenetic analyses of these crucial proteins. This study hopes to bridge this gap with a phylogenetic investigation of FadL, FadD, PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY across different species and orders in the Gammaproteobacteria class. In addition to investigating proteins directly involved in the exogenous fatty acid uptake and membrane incorporation (FadL, FadD, PlsB, and PlsC), this study expands its purview to include PlsX and PlsY as well since the PlsX/PlsY/PlsC pathway serves a similar function to the PlsB/PlsC pathway and due to the mystery surrounding the retainment of both pathways in some species. Thus, the primary aim of this study is to generate a phylogenetic tree for each of these six proteins to understand relationships between their homologs found in various species.

FadL and FadD are especially interesting for this study due to identification of multiple homologs encoded by numerous species. For example, one of the base species for this study, V. cholerae, possesses three homologs of both of these proteins. The reason behind the retention of three distinct homologs remains unclear. Through a phylogenetic investigation of FadL and FadD accompanied by operon and docking investigations, this study aims to address the dynamics of structure-function, genomic context, and ecology/evolutionary perspective. We hypothesize that the FadL homologs have evolved, from a primarily aquatic origin, to display fatty acid preferences, thereby expanding substrate recognition and utilization that best serves their biphasic lifestyle. This study employs bioinformatics to obtain phylogenetic, gene/protein comparisons, and protein/ligand modeling to investigate the exogenous fatty acid handling machinery in gram-negative bacteria. The secondary aim is to expand the phylogenetic investigations and to better understand the existence of multiple homologs of FadL and FadD by investigating the environmental origin and potential FadL operon arrangements of the surveyed species, a consensus sequence analysis, and docking select fatty acids with representative FadL homologs.

1.4. Previous work

No previous work that we could find has been done for creating phylogenetic trees for any of the proteins we investigate. There have been previous efforts to characterize the phylogeny of Gammaproteobacteria. Most notable is the work by Williams et al. [3] and Brandis [18]. These studies built phylogenetic trees based on the full genome. While the studies investigated different species of Gammaproteobacteria, both studies found the same phylogenetic order for five important orders: Vibrionales, Entereobacteriales, Alteromonadales, Aeromonadales, and Pasteurallales. Enterobacteriales and Pasteuralles were found in the innermost branch. Next, Vibrionales was on a sister branch to those two orders. Aeromonodales and Alteromonadales were on progressive sister branches. In our study, we investigate phylogenetic relationships within these same five orders. These previous phylogenetic studies also use prominent algorithms worth commenting on. Williams et al. [3] uses Mr. Bayes and RAxML algorithms, while Brandis [18] uses CLC maximum likelihood phylogeny algorithm. As RAxML is also a maximum likelihood algorithm [19], both papers used maximum likelihood algorithms.

Previous studies have also worked to further analyze the FadL protein. Investigations on a neighboring protein (genomically speaking) to FadL, lipoprotein VolA, discovered an operon structure consisting of FadL Homolog VCA0862 followed by lipoprotein VolA in V. cholerae [20]. Studies have also done docking analysis for FadL homologs. Turgeston et al. [14] identified four nodes of binding in FadL homologs: the low affinity spot (node 1), the high affinity spot (node 2), S3 kink/node 3, and node 4.

While this study only investigated docking of fatty acids to V. cholerae and E. coli FadL homologs, our investigations include FadL homologs from other Gammaproteobacteria species as well. Of the species investigated, only the E. coli FadL has been crystalized; as such, protein models needed to be predicted. Many software exist for these purposes. Chapter 23 of the Advances in Protein Molecular and Structural Biology Methods [21] details sample methodologies for the prediction, validation, refinement, and energy minimization for protein models. The key steps here are the prediction and energy minimization of the models. The first step is to predict the tertiary structure of the FadL homologs from the secondary structure. The prediction can be done by a variety of tools, including SWISS-MODEL [[22], [23], [24], [25]], AlphaFold [26], I-Tasser [[27], [28], [29]], and MODELER [[30], [31], [32], [33]]. For example, Turgeston et al. utilizes I-Tasser for this purpose. Energy minimization aims to reduce the potential energy of the model and is performed by molecular dynamics software such as GROMACS [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. This software has been used in many recent studies [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]]. The final step for the docking investigations is the actual docking. This can be conducted by programs like AutoDock Vina [48,49] and AlphaFold [26].

2. Methods

2.1. Sourcing sequences

Separate phylogenetic trees were constructed for six proteins associated in exogenous long-chain fatty acid acquisition and assimilation: FadL, FadD, PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY. For each of these proteins, amino acid base sequences from Gammaproteobacteria species Vibrio cholerae (strain - Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. N16961) and Escherichia coli were obtained from NCBI database [50] as complete FASTA sequences stored as txt files, using locus tags identified in a previous study [5]. As multiple homologs of FadL and FadD are seen in some species, three homologs from V. cholerae for both of these proteins were used. For the remaining proteins, only one base sequence from V. cholerae was used. For all of the surveyed proteins, only one base sequence from E. coli was used. The locus tags of these chosen base sequences can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Locus tags of amino acid base sequences used to construct phylograms.

| Protein | Amino Acid Base Sequences from V. cholerae | Amino Acid Base Sequences from E. coli |

|---|---|---|

| FadL | VCA0862 (1), VC1042 (2), VC1043 (3) | b2344 (4) |

| FadD | VC1985 (1), VC2341 (2), VC2484 (3) | b1805 (4) |

| PlsB | VC0093 (1) | b4041 (2) |

| PlsC | VC2513 (1) | b3018 (2) |

| PlsX | VC2024 (1) | b1090 (2) |

| PlsY | VC0053 (1) | b3059 (2) |

Protein homologs were searched using NCBI protein-protein Blast (blastp) [50] for each of five chosen gamma-proteobacteria orders: Vibrionales, Entereobacteriales, Alteromonadales, Aeromonadales, and Pasteurallales. Each base sequence was deposited in blastp with the organism field specified to each specific order. V. cholerae and E. coli were excluded for queries for orders Vibrionales and Enterobacterales, respectively, as otherwise these species would dominate the results preventing other species from being sampled. Each base sequence was input in the order signified by the number within square brackets as seen in Table 1. The algorithm parameters were left to default, with 100 max target sequences and an expect threshold of 0.05.

Hits (a matched sequence) from unnamed or unclassified species were excluded. If more than one hit was obtained for a particular species, a representative strain (i.e., the sequence with the highest score and, if applicable, with details about which strain the sequence is from) was included. For PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY, if the second base sequence yielded hits from the same species as the first base sequence, those hits were excluded. For FadL and FadD, due to the potential existence of multiple homologs within the same species, hits from the same species yielded from different base sequences of V. cholerae were retained. However, if hits from the same species were yielded from the base sequence from E. coli, those (previously identified) hits were excluded. Additionally, for order Vibrionales, as species of this order are expected to possess three homologs of FadL and FadD, if hits from a species were identified from one V. cholerae base sequence(s) but not the other(s), blastp was executed with input of the other base sequence(s) targeting the species in question in order to find all the homologs found within the species. For each resulting hit, the complete FASTA amino acid sequence was downloaded as a txt file from NCBI [50]. The corresponding FASTA nucleotide sequence of each FASTA amino acid sequence sourced was also downloaded from NCBI [50].

The title of each FASTA file (both amino acid and nucleotide sequences) was standardized to enable more effective visualization in the final tree. The title encodes the species, source, and NCBI GenBankID. The first part is the genus, species, and strain/subspecies (if applicable) separated by a period (‘.’). This is followed by a number in parentheses signifying the base sequence (as detailed in Table 1) input in BLAST to find the sequence and finally the GenBankID. This title is the same as the species tag seen in the final phylogenetic trees.

2.2. Identifying suitable outgroups

As the target group is Gammaproteobacteria, outgroups from Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria were considered as these classes are the closest relatives to the Gammaproteobacteria class. Three potential outgroups were chosen based on the results of previous phylogenetic study of Gammaproteobacteria [3], namely Rhodospirillum rubrum (Alphaproteobacteria), Sriorhizobium meliloti (Alphaproteobacteria), and Chromobacterium violaceum (Betaproteobacteria). Another Betaproteobacteria species, Candidatus Accumulibacter phosphatis, was also considered as an outgroup as it was identified as an outgroup in our previous unpublished study. Homologs for each protein were acquired for each of these species via BLAST. The first base sequence for each protein was first used as input. If a homolog was not matched for a species, consecutive base sequences were used until a homolog was found. If none of the consecutive base sequences yielded a homolog hit for a species, the species was excluded from further steps. Complete FASTA amino acid and nucleotide sequences were downloaded for the species with matched homologous sequences, and their titles were standardized in the manner described in section 2.1.

Test phylogenetic trees were built using Geneious Prime 2021.2 (https://www.geneious.com/). All the amino acid sequences for each protein were input and aligned with the Clustal Omega algorithm. A test phylogenetic tree was built using the native Geneious Tree Builder with Jukes-Cantor gene-distance model and Neighbor-Joining tree building method. The most distantly related outgroup species for each protein was identified as the suitable outgroup.

2.3. Tree building

The final phylogenetic trees were also built using Geneious Prime 2021.2 (https://www.geneious.com/). FASTA files of amino acid sequences were input into Geneious Prime and separated by protein surveyed. Sequences for each protein were aligned using the Clustal Omega algorithm. Phylogenetic trees were then built by two different methods. The first method used Mr. Bayes 3.2.6 [51] with two parallel runs, four independent Markov chains per run of one million generations, rate matrix poisson, and rate variation model gamma. The subsampling frequency was set to 40 and heated chain temperature to 0.2. The first 10% of the trees were discarded for the formation of the final tree. The second method used RAxML version 8 [19], which uses Maximum Likelihood. Protein model GAMMA BLOSUM62 and algorithm Rapid Bootstrapping using rapid hill-climbing was used. Finally, for both the trees, the identified outgroup was rooted if necessary, sister taxa were swapped as appropriate, and trees were colored and labeled to visually represent different orders. Condensed phylogenetic trees of the full phylogenetic tree made using Mr. Bayes was also constructed by collapsing all branches containing more than 4 homologs where at least 80% of the homologs were from the same order and 3 or less homologs were not from the same order.

Phylogenetic trees for the nucleotide sequences were also developed to serve as comparison for the amino acid sequence phylograms. Similar methods were used to create these phylograms. The first method used Mr. Bayes 3.2.6 [51] with two parallel runs, four independent Markov chains per run of one million generations, and rate variation model gamma. Substitution model HKY85, the Hasegawa, Kishino and Yano 1985 model, was used. The subsampling frequency was set to 40 and heated chain temperature to 0.2. The first 10% of the trees were discarded. Again, the outgroups were set to the previously identified suitable outgroup. In order to yield one tree, the sorted topologies were sorted again using the native Consensus Tree Builder with the first 95% of original sorted topologies discarded. The second method used RAxML version 8 [19], which uses Maximum Likelihood. Nucleotide model GTR GAMMA and algorithm Rapid Bootstrapping using rapid hill-climbing was used. Finally, for both trees, the identified outgroup was rooted, if necessary, sister taxa were swapped as appropriate, and trees were colored and labeled to visually represent different orders.

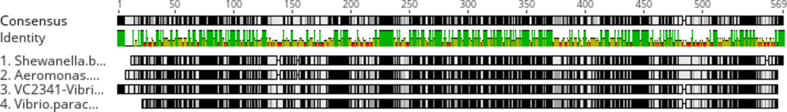

2.4. Additional analyses for the phylogenetic trees

The natural environment for selecting species in major genuses present within each tree was recorded. Potential operon arrangements of the genes encoding for each FadL homolog were investigated via NCBI's graphical GenBank [50]. Finally, consensus sequences were created for each branch clustering around a base sequence. Three to four other sequences were chosen, representing the genus and order diversity found within the branch. This was done for each of the six proteins investigated using the Mr. Bayes phylogenetic trees based on amino acid sequences to inform selection. These sequences along with the base sequence were aligned using the Clustal Omega algorithm in Geneious Prime. The consensus sequence of each alignment was extracted. These consensus sequences were then aligned against other consensus sequences of the same protein, yielding another consensus identity.

2.5. Molecular binding simulations

The preferences of seventeen FadL protein homologs representative of the whole phylogram for five fatty acids (linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO), and oleic acid) were investigated. 3D structural models of the homologs were predicted using SWISS-MODEL [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Two different models were predicted for each homolog to ensure a better protein structure. One set was modeled on a previously crystalized E. coli FadL (Crystal structure of the long-chain fatty acid transporter FadL, PDB ID: 1T1L) [52] and another was modeled on a previously crystalized P. aeruginosa FadL (Crystal structure of a P. aeruginosa FadL homolog, PDB ID: 3DWO) [53]. The GMQE, QMEANDisCo Global, and Sequence Similarity statistics produced by SWISS MODEL during the modeling of these proteins is reported in Appendix H Table 1. For each homolog, the protein structure with the highest QMEANDisCo Global of the two models produced was chosen to continue for the following validation and eventual docking.

The chosen protein models were then validated, refined, and energy minimized using a methodology adapted from Ref. [21]. The protein models were validated using SAVES version 6.0 (a tool by the Doe Lab at UCLA) and ERRAT, VERIFY, and PROCHECK were run. ERRAT compares non-bonded interactions to highly refined structures [[54], [55], [56], [57], [58]]. The ERRAT score gives the overall quality factor [54]. VERIFY calculates the compatibility of the 3D protein model with the protein's amino acid sequence [55,56]. The VERIFY score is a percentage of the amino acids that have averaged 3D to 1D scores of greater than or equal to 0.1. PROCHECK assesses the stereochemical quality of the protein model, returning the core, allowed, and disallowed Ramachandran plot percentages [57,58]. The ERRAT overall quality factor, VERIFY percentage, and the Ramachandran plot percentages are listed for each of the models in Appendix H Table 1.

The protein models were then refined using GalaxyRefine [[59], [60], [61]]. GalaxyRefine produces five refined models for each input model. For each modeled homolog, the five refined models were compared using SWISS-MODEL structure assessment [22,25], and the modelwith the highest QMEANDisCo Global score was chosen for continuing on in the future steps. The best model was analyzed by SAVES [[54], [55], [56], [57], [58]] in the same manner as the original predicted protein was. The QMEANDisCo Global and MolProbity scores for each of the refined models and SAVES statistics for the best model are listed in Appendix H Table 1. Finally, the protein models were energy minimized using GROMACS [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. The models were first prepared. Topology was generated using pdb2gmx command and the AMBER94 forcefield. The models were then solvated in an 1 nm cube using the editconf function. The models were then neutralized by adding the appropriate amount of sodium ions, concluding the preparation of the models for the energy minimization.

The now validated, refined, and energy minimized models were prepared for docking analysis with AutoDock Vina. During energy minimization in GROMACS, the protein is solvated in a solvation grid. The protein model is isolated from the solvation grid using UCSF Chimera [62]. Finally, polar hydrogens and Kollman charges are added to the resulting protein models (in pdb file format), and the pdb files are saved as pdbqt files using AutoDock Tools [63]. Meanwhile, ligands are also prepared. Fatty acid files for linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, DHA, LDAO, and oleic acid were obtained from PubChem [64] in sdf format and converted into pdb format using NIH's Online SMILES Translator & Structure File Generator [65]. The ligand files were also prepared using AutoDock Tools by appropriate processes.

Both ligand file and protein file were input into AutoDock Tools [63] to calculate the grid box. The grid box size remained constant as a cube of side length 40. The centers of the grid boxes varied with different protein models, but the center coordinates remained constant for each protein model regardless of the ligand and are listed in Appendix H Table 2. Both files and grid box information were input into our python script (deposited in Appendix H) to generate configuration settings for AutoDock Vina [48,49] and to write command prompts. Our python script exported the required configuration files for AutoDock Vina. Specifically, for all of the docking, exhaustiveness (the flexibility of atoms with higher value correlating with better binding sites) was set to 100, energy range at 4, and number of modes above the maximum allowed by AutoDock Vina, 20. Our script also exported the command prompts to run AutoDock Vina docking as windows batch files, which when executed directly runs the AutoDock Vina docking analysis. AutoDock Vina [48,49] calculated binding affinities for potential binding pockets and exported the top twenty binding sites and ligand configurations. Four different significant binding sites have been previously identified by Turgeson et al. [14] in E. coli and V. cholerae FadL homologs: the low affinity spot (node 1), the high affinity spot (node 2), S3 kink/node 3, and node 4. The first two of these spots correspond to the predicted binding spots for fatty acids to the E. coli FadL [52]. The S3 kink was also named by the same study [14] and is the inward pointing portion of the S3 strand of FadL which disrupts the β-sheet secondary structure. If a node is present within the twenty binding sites for the FadL homologs, the binding site with the highest binding affinity was recorded for the node (as seen in Appendix H Table 3). Node 4 was not present in all homologs Turgeson et al. [14] and exhibited no binding with our FadL homologs. As such, node 4 is not included in Appendix H Table 3.

Statistical analysis of the molecular docking data was performed via R studio [66] and Microsoft Excel [67]. Since the aim of this investigation was to understand potential differential preferences of fatty acids for the different FadL homologs, the results for the proteins clustering around each base homolog and the homolog itself was pooled, creating four categories, one for each base homolog. Only the S3 kink/node 3 displayed consistent binding to the fatty acids for all the FadL homologs. As such, only the results for binding at the S3 kink/node 3 were considered for statistical analysis. A Type II 2-way Anova, followed by a Tukey's post-hoc test, was performed via R studio with the significance value threshold of p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics and graphs were then compiled via Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

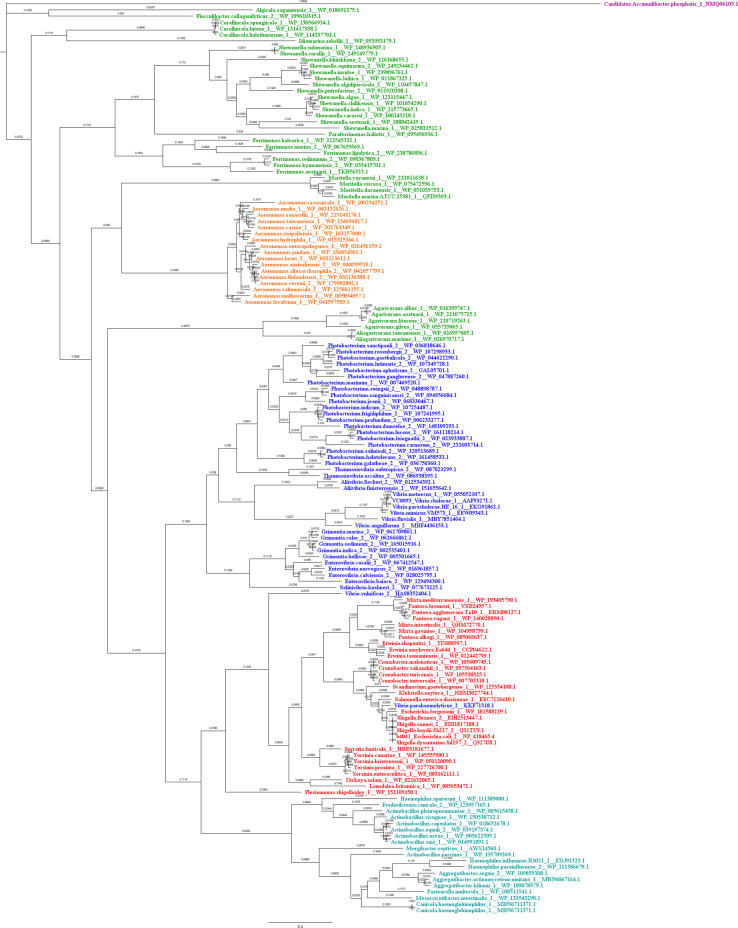

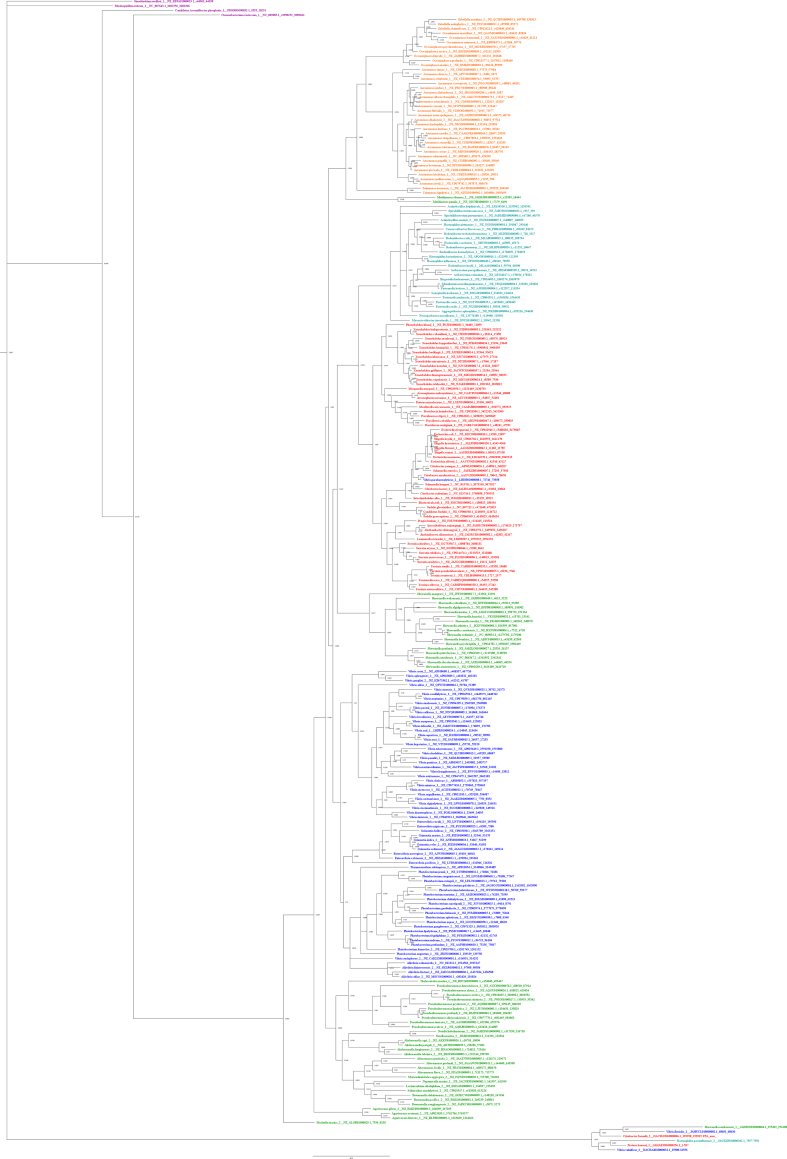

3.1. Phylogenetic trees

After outgroup analysis, Sinorhizobium meliloti was identified as the most suitable outgroup for FadL, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY, while Candidatus Accumlibacter phosphatis was identified as the most suitable outgroup for FadD and PlsB. Condensed phylograms made using amino acid sequences with Mr. Bayes can be found in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7. Full finished phylogenetic trees for FadL, FadD, PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY can be found in Appendices B through G, respectively. In general, for FadL and FadD, homologs seem to cluster based on either order or which base sequence they were blasted from. They roughly form three clusters, one for each of the V. cholerae homologs, and sometimes a separate cluster for the E. coli homolog. For the Pls proteins, homologs generally seem to cluster based solely on order. Finally, the consensus sequences built for each protein can also be found in Appendices B through G.

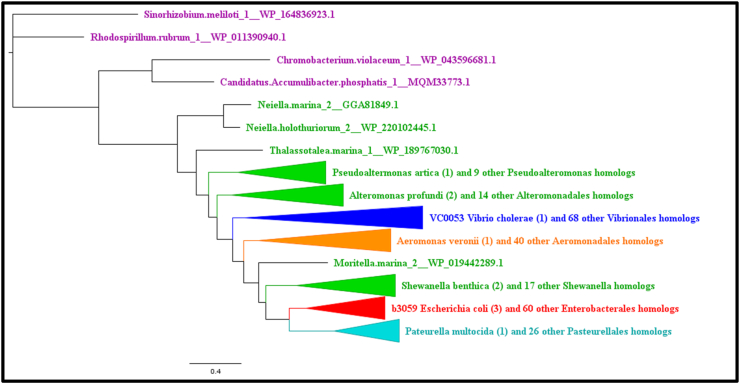

Fig. 2.

FadL Condensed Phylogram. FadL Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

FadD Condensed Phylogram. FadD Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

PlsB Condensed Phylogram. PlsB Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

PlsC Condensed Phylogram. PlsC Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 6.

PlsX Condensed Phylogram. PlsX Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 7.

PlsY Condensed Phylogram. PlsY Phylogram made using amino acid sequences and algorithm Mr. Bayes condensed by collapsing mostly homogenous branches in terms of order. Phylograms are color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2. Operon analysis

Seven main potential operon structures were identified from this analysis. Results of the operon analysis are visualized in Appendix B Fig. 3. The first operon structure consists of an RNA polymerase sigma factor followed by a hypothetical protein, a DUF3379 domain-containing protein, or a chemotaxis protein followed by a FadL and finally followed by another FadL. Homologs with this operon structure with the FadL found in the first position of the FadLs are colored light blue. Homologs with this operon structure with the FadL found in the second position of the FadLs are colored in dark blue. The second operon structure consists of FadL followed by a lipase. This potential operon structure has been verified as an operon in V. cholerae [19]. Homologs with this operon structure are colored red. The third operon structure consists of a FadL followed by an sodium/proton antiporter. Homologs with this potential operon structure are colored purple. The fourth operon structure consists of a FadL followed by a methylated-DNA-cysteine S-methyltransferase. Homologs with this potential operon structure are colored in teal. The fifth operon structure consists of a FadL followed by a nuclear transport factor 2 family protein and finally a glycerol kinase glpK. Homologs with this potential operon structure are colored light green. The sixth operon structure consists of a FadL followed by a MerR family DNA-binding transcriptional regulator. Homologs with this potential operon structure are colored pink. The seventh operon structure consists of a FadL followed by another FadL finally followed by an EAL domain-containing protein. Homologs with this operon structure with the FadL found in the first position of the FadLs are colored light orange. Homologs with this operon structure with the FadL found in the second position of the FadLs are colored in dark orange.

3.3. Molecular binding

We sought to investigate any potential preferences for different fatty acids FadL homologs may have. As multiple homologs of FadL exist within some species, we predicted the base FadL homologs and the FadL homologs which clustered around the base homologs would have distinct preferences in fatty acids from other base homologs and accompanying clustering homologs. We predicted the tertiary structures of the base FadL homologs along with some other select FadL homologs. The statistics from the prediction, validation, and refinement of these homologs can be found in Appendix H table 1. Binding between fatty acid and FadL homolog was simulated, with 20 binding locations predicted for each fatty acid - FadL homolog pair. The parameters for the grid boxes and the binding affinities from the interactions are documented in Appendix H Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The binding was classified into four different binding nodes (low affinity node, high affinity node, S3 kink, and node 4), based on a previous study [14]. Node 4 exhibited no binding with any fatty acid for any FadL homolog. Additionally, the high affinity and low affinity spots exhibited binding with only a few FadL homolog – fatty acid pairs. However, the S3 kink exhibited binding with all the fatty acids for all the FadL homologs. Some of the binding spots predicted by AutoDock Vina were in the surface of the protein or in other non-active sites.

The FadL homologs were clustered into four categories based on what base sequence they cluster with. The binding affinities at the S3 kink from the categories were statistically analyzed. The mean affinities and standard error were calculated for each fatty acid for all the clusters. These are graphed in Fig. 8 and documented in Table 2. The fatty acid with the greatest mean affinity for the VCA0862, VC1042, VC1043, and b2344 clusters was DHA (−6.78 kCal/mol), arachidonic acid (−6.60 kCal/mol), DHA (−6.88 kCal/mol), and DHA (−7.00 kCal/mol), respectively, as seen in Table 2.

Fig. 8.

Mean Affinities at S3 Kink. Mean affinities of binding of each fatty acid to the FadL homologs at S3 kink found in each of the clusters is shown with error bars representing standard error. The brackets above the bars represent significant differences in the mean affinities. If the p-value is less than 0.05, there is one asterisk above. If the p-value is less than 0.01, there are two asterisks above.

Table 2.

Mean Binding Affinities for the FadL Homolog clusters.

| FadL Proteins | Mean Affinities (in kCal/mol) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linoleic Acid | Arachidonic Acid | DHA | LDAO | Oleic Acid | |

| VCA0862 Cluster | −5.94 | −6.5 | −6.78 | −5.16 | −5.82 |

| VC1042 Cluster | −6.175 | −6.6 | −6.45 | −5.575 | −6.175 |

| VC1043 Cluster | −5.85 | −6.45 | −6.875 | −5.225 | −5.8 |

| b2344 Cluster | −6.125 | −6.4 | −7 | −5.45 | −5.95 |

A type II 2-way Anova was also conducted. The 2-way Anova revealed that fatty acid type significantly affected affinity energy (p = 6.801e-10, as seen in Table 3), but the FadL homolog category and the interaction between the two was insignificant (p = 0.6531 and p = 0.9569, respectively, as seen in Table 3). There was no significant difference between FadL homologs clustering, as seen in Table 4. When looking at each FadL base homolog clusters individually, there is a significant difference between the mean affinities for DHA vs. LDAO for the VCA0862, VC1043, and b2344 clusters (p = 0.0018309, p = 0.0075762, p = 0.0173049, respectively) and also between arachidonic acid and LDAO for the VCA0862 cluster (p = 0.0260399).

Table 3.

2-way Anova for Affinities at the S3 Kink for E. coli modeled FadL Homologs.

| Sum Sq | DF | F value | Pr(>F) (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid | 20.7311 | 4 | 17.7539 | 6.801e-10 |

| FadL Homolog Clusters | 0.4775 | 3 | 0.5452 | 0.6531 |

| Interaction | 1.4169 | 12 | 0.4045 | 0.9569 |

| Residuals | 18.9750 | 65 |

Table 4.

Tukey Post-Hoc Test for Significance between Affinities of different E. coli modeled FadL Homolog Clusters at S3 Kink.

| p adj | |

|---|---|

| VCA0862-VC1042 | 0.774'5424 |

| VCA0862-VC1043 | 1.0000000 |

| VCA0862-b2344 | 0.8076763 |

| VC1042-VC1043 | 0.8010636 |

| VC1042-b2344 | 0.9999273 |

| VC1043-b2344 | 0.8309418 |

4. Discussion

4.1. FadL phylograms

Our FadL phylograms (Appendix B1-5) illustrate similar phylogenetic relations as captured by previous studies [3,18]. The finding Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales are most related among these orders is substantiated by our phylograms as well. Additionally, Williams et al. [3] and Brandis [18] found that Vibrionales is the next closely related order being present on a sister branch to Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales. Interestingly, while the RaxML-generated phylogenetic tree using nucleotide sequences mirrors this pattern, our FadL phylogram made using Mr. Bayes and amino-acid sequences suggests that Vibrionales homologs are instead most closely related to Alteromonadales and Aeromonadales homologs and these three orders are found in a sister group to Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales. The FadL Mr. Bayes phylogram based on nucleotide sequences also more closely resembles the RaxML nucleotide phylogram, although it suggests that Vibrionales are the most external order. Conversely, the RaxML amino acid phylogram most nearly matches the Mr. Bayes amino acid phylogram. As such, it seems the nucleotide based phylograms present an evolutionary pathway more similar to previous studies. The nucleotide based phylograms looked at the full genetic code of the proteins, rather than just the amino acid sequence, allowing the nucleotide based phylograms to recognize silent mutations in the genetic code that would not affect the amino acid sequence. Hence, perhaps the true evolutionary pathway of the FadL protein resembles what is seen in the nucleotide-based phylograms, which in turn are closer to the overall evolutionary history of these orders [3,18]. Findings from the amino acid phylograms are also interesting, however, as they indicate greater divergence in the FadL homolog amino acid sequences between order Enterobacterales & Pasteurellales and Vibrionales, Alteromonadales, and Aeromonadales.

Williams et al. [3] also found that the order Alteromonadales is not monophyletic. Their final phylogenetic tree suggests that Alteromonadales is instead a polyphyletic order. Most of the genera surveyed in their study, including all the genera surveyed by both theirs and our study, are found within one regional sub-tree. In this subtree, the Alteromonadales order seems paraphyletic. Within each cluster of our FadL phylograms, the homologs of Alteromonadales also seem paraphyletic. Furthermore, FadL homologs of some species cluster with other orders, matching the intertwining present in the phylogram by Williams et al. [3].

As noted earlier, the FadL homologs tend to cluster in separate nodes. Specifically, they cluster mainly based on which base homolog their sequence was blasted from, corresponding to the presence of three FadL homologs in V. cholerae. This is seen for the Vibrionales and Alteromonadales orders, and partially for the Aeromonadales order. The tendency for these homologs to cluster with other homologs blasted from the same base sequence rather than solely order suggests a more ancestral origin of the multiple homolog phenomena. The genes for each of the homologs may have originated in an early ancestor of Gammaproteobacteria. Indeed, like V. cholerae, most other Vibrionales species also presented three homologs of FadL. Even some species not in the order Vibrionales presented multiple homologs of FadL. Likewise, many other species may have undocumented FadL homologs.

On the other hand, almost all of the homologs found in orders Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales cluster in one node seemingly based on order alone. These homologs are also most related to base sequence 1 (VCA0862). These orders may have simply diverged prior to the potential common ancestor with multiple homologs. Alternatively, these orders may have either lost genes coding for the other homologs or have undocumented or more divergent sequences for the other homologs preventing detection with this study's search. Based on previous studies indicating Enterobacterales and Pasteuellales are found in the same branch as Vibrionales, Aeromonadales, and Alteromonadales [3,18], the latter hypothesis is more likely.

One major exception to the general trend seems to be homologs blasted from base sequences 1 (VCA0862) and 4 (b2344) as these homologs cluster together more often rather than separately. True to this, almost all Vibrionales homologs cluster along the base sequence they were blasted from with homologs blasted from base sequence 4 clustering with base sequence 1. It is important to note that the RAxML phylogenetic tree (Appendix B2) still shows that base sequence 4 is most related to base sequence 3. However, given Mr. Bayes is likely to be more accurate, this phylogram may be misleading in this detail.

Out of the three major clusters, the cluster revolving around base sequences VCA0862 and b2344 are the most nested and have the greatest evolutionary distance. This may relate to the position of VCA0862 on the second chromosome of V. cholerae [20]. Genes on the second chromosome tend to evolve faster [68]. Hence, this greater evolutionary distance for the VCA0862/b2344 cluster makes sense. Interestingly, this is the homolog that works in concert with a lysophospholipase to liberate 18:2 for uptake, presumably conferring an advantage for survival of Vibrio in the human intestine [20]. Perhaps VCA0862 was acquired later, as suggested by the phylograms, as an evolutionary means for colonizing the intestine similar to several other enterobacteria (Shigella, Yersinia, Escherichia) that possess a closer relative of FadL.

Another important exception to this trend is the V. fluvialis homolog blasted from base sequence 1. Despite being blasted from base sequence 1, this homolog clusters with base sequence 3 (VC1043). This perhaps can better be explained by the potential operon structures of these homologs (as shown in Appendix B3). Three different operon structural arrangements/positions matched the branching pattern of Vibrionales homologs perfectly with only one operon structural arrangement/position seen for each of the three Vibrionales branches. This is also true for the Vibrio fluvialis homolog blasted from base sequence 1. Like other Vibrionales homologs from its branch (those which are blasted from base sequence 3), this Vibrio fluvialis homolog is preceded by a RNA polymerase sigma factor and another protein and succeeded by another FadL sequence. As such, it seems this Vibrio fluvialis homolog is truly more related to base sequence 3 rather than base sequence 1. Due to the significant similarities and conservation between base sequence 1 and 3 (as seen in Appendix B7), the blast search with input of base sequence 1 may have picked up this homolog despite it being more related to base sequence 3. There is only one Vibrionales homolog within the condensed sample which does not present any of the operon structures seen for the rest of the homologs, the Enterovibrio norvegicus homolog blasted from base sequence 4. Fittingly, while this Enterovibrio norvegicus homolog is found in the same main branch as base sequence 1, it is found on the sister taxon to the remainder of the Vibrionales species in the branch clustering instead with Alteromonadales homolog(s). Thus, this homolog is shown to be the least related to the remainder of the Vibrionales species clustering with base sequence 1.

The first operon structure encompassed most vibrionales homologs clustering with VC1042 and VC1043. There were two FadL gene positions in this potential operon, with homologs clustering with VC1043 occupying the first position and the ones clustering with VC1042 occupying the second position. Given the genes for VC1042 and VC1043 are present on the same potential operon structure and are right next to each other, these two homologs may have arisen from a gene duplication. As only Vibrionales species contain this potential operon structure, this duplication may have happened in the common ancestor of Vibrionales species. However, a few non-Vibrionales species have homologs clustering with both the VC1042 and VC1043, including Shewanella atlantica. This may refute the prior hypothesis or be explained by multiple duplication events. Regardless, an aquatic origin for the evolution of these homologs is plausible, and it is tempting to speculate that these proteins may have evolved to recognize fatty acids (eg, PUFAs) associated with marine organisms [[69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80]].

There are multiple other operon structures that were found by our operon arrangement investigation. One of these operon structures marks only Vibrionales homologs. Specifically, this potential operon structure (color-coded as purple in Appendix B3) contains Vibrionales homologs from genuses other than Vibrio that cluster alongside VCA086. Other operon structures are for different orders. Every potential structure only has homologs from one specific order. Additionally, with the exception of the seventh potential operon structure, all homologs within a potential operon structure tend to cluster near each other.

4.2. FadD phylograms

The FadD phylograms (Appendix C1-4) present the same overall trends as the FadL phylograms. Like in FadL, homologs tended to first cluster out based on what base sequence they were blasted from and then based on their order. Our FadD phylograms continue to show the trend that sequences blasted from base sequences 1 (VC1985) and 4 (b1805). Instead of four main clusters centered around each of the four base sequences, similar to what was seen in FadL phylograms, there were three main clusters centered around the V. cholerae base sequences with the E. coli base sequence clustering with VC1985. This indicates that the E. coli homolog is most related to VC1985 compared to the other V. cholerae homologs. Unlike in FadL, even homologs from orders Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales tend to cluster more in this manner. In FadL, these two orders were only presented in one cluster; however, in FadD, these two orders are present in two clusters, one with VC1985/b1805 and another with VC2484. This suggests the multiple homolog phenomena for FadD is more ancestral and/or more conserved across the Gammaproteobacteria orders. However, it is important to investigate the exceptions to this tendency, namely the lack of Pasteurellales homologs clustering with base sequence VC2341. While homologs of Pasteurellales most related to VC2341 may simply not have been documented yet or not surveyed by this study, this could indicate that Pasteurellales species lost or divergent genes for such homologs given the observed inner branch location of Pasteurellales compared to the other orders surveyed [3,18]. Such a case may also be tied to the differential natural environment of Pasteurellales. While most species in our condensed sample naturally live in aquatic environments or in the gastrointestinal tract of hosts, many Pasteurellales species live in the oral cavity and respiratory tracts of humans and other hosts [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74]]. A differential environment may have selected for a greatly divergent homologs preventing their identification with our methods or have rendered the homolog redundant leading to the gene's loss. The latter may especially be the case if homologs like VC2341 are specialized for specific fatty acids which are not found in the Pasteurellales environment. It is tempting to speculate that the VC2341 homolog evolved from an aquatic lifestyle since almost all bacteria in its cluster inhabit marine environments [[69], [70], [71], [72],[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90]].

There are also some differences in the phylogenetic relations between orders within clusters between our FadD phylograms and previous studies [3,18]. The main discrepancy between our FadD phylograms and these previous studies involves the three most internal orders from these previous studies, Vibrionales, Enterobacterales, and Pasteurellales. Previous studies indicate that Enterobacterales and Pasteurellales are sister taxa on the most internal branch, followed by Vibrionales, Aeromonadales, and Alteromonadales on successively external branches. For the Mr. Bayes phylogram based on amino acid sequences, in the VC1985/b1805 base sequence centered cluster, Enterobacterales and Vibrionales present as sister taxa in the most internal branch with Pasteurellales in a sister branch to the two orders. Aeromonadales and Alteromonadales were the most and second most external branch for this phylogram. This may indicate that the amino-acid sequences of Pasteurellales and Aeromonadales diverged more greatly than the other orders. Interestingly, the RAxML amino acid based phylogram (Appendix C2) matched the order seen in previous studies much more closely, suggesting the divergences seen in the Mr. Bayes phylogram (Appendix C1) likely represent comparatively subtle amino acid sequence differences that could not be detected by the RAxML algorithm. Meanwhile, the nucleotide based phylograms yielded paraphyletic VC1985/b1805 clusters. This suggests that the VC1985/b1805 homologs are either the oldest/least divergent from an ancestral gene compared to the other two homologs. Interestingly, in this cluster, two Vibrionales homologs from the species V. vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus cluster with the Enterobacterales homologs in all of the phylograms.

For the VC2341 base sequence centered cluster, the order shown in all the phylograms match between each other. Since Pasteurellales species are not present and very few Enterobacterales species are present, it is hard to comment on the relations with both of these orders. The remaining orders reflect the arrangement seen by previous studies. In the VC2484 base sequence centered cluster, Alteromonadales is conserved as the most external order in all of the phylograms. Between Vibrionales, Enterobacterales, and Pasteurellales, all phylograms show Enterobacterales in a sister branch to the branch with Vibrionales and Pasteurellales as sister taxa. The position of the Aeromonadales order homologs varies between the amino-acid based (Appendix C1-2) and nucleotide based phylograms (Appendix C3-4). While the amino-acid based phylograms indicate that Aeromonadales are sister taxa to Enterobacterales, the nucleotide based phylograms indicate that Aeromonadales are external to the Vibrionales, Enterobacterales, and Pasteurellales. This discrepancy suggests that the Aeromonadales homologs have the amount of nucleotide substitutions expected evolutionarily based on phylogenetic arrangement from previous studies.

4.3. PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY phylograms

Unlike FadL and FadD phylograms, PlsB, PlsC, PlsX, and PlsY phylograms (Appendix D-G 1-4) are dominated by the tendency to cluster based on order alone. This makes sense as these proteins only have one homolog in each species. The main exception in this tendency is the clustering of homologs from V. vulnificus and V. parahaemolyticus with Enterobacterales rather than Vibrionales. This is the same scenario seen with FadD and may be due to greater divergence in these species for the Pls protein genes. While most phylogenetic trees for the Pls proteins coincide with each other fairly well, the RAxML phylogram based on nucleotides showcases significant differences. As this phylogram is most likely prone to errors, we will ignore this phylogram for this discussion.

For PlsB (Appendix D 1-4), the general relationship between orders matches previous studies [3,18]. Likewise, the general relationship seen in PlsX phylograms (Appendix F 1-4) also matches previous studies, with the exception of the aeromonadales order which is often found to be the most external order. This indicates that these proteins evolved at the same rate and manner as the species did, suggesting greater divergence. Interestingly, these two proteins are also the first protein in their respective fatty acid membrane incorporation pathways.

For PlsC (Appendix E 1-4), the Mr. Bayes phylogram based on amino acid sequences (Appendix E1) presents Enterobacterales and Vibrionales as the innermost branch with Pasteurellales as more external. This may indicate the greater divergence of Pasteurellales sequences of PlsC compared to Enterobacterales and Vibrionales, which could reflect the differing environments inhabited by species of this order [[69], [70], [71], [72],[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90]]. Interestingly, the RAxML amino acid and Mr. Bayes nucleotide phylogenetic trees (Appendix E2 and E3, respectively) more closely match the arrangement between orders as seen by previous studies [3,18], although Enterobacterales is paraphyletic instead of monophyletic in the internal branch in the RAxML amino acid based phylogram (Appendix E2). All the trees also present Aeromonadales as the most external branch. This suggests the greater divergence of PlsC sequences from the whole order of Aeromonadales.

For PlsY (Appendix G 1-4), the arrangement of orders matches previous studies with the major exception of the Aeromonadales order and Shewanella genus of Alteromonadales. The Aeromonadales order clustered at different locations between the phylograms. Aeromonadales most commonly experience greater divergence for all the target proteins. This may be indicative of a greater evolution in Aeromonadales for fatty acid metabolizing proteins. It may be beneficial to study phylogeny of other proteins with similar roles to investigate this tendency of Aeromonadales further. The second deviance seen for PlsY was the Shewanella species. These species clustered separately from the other Alteromonadales species, instead clustering next to the Aeromonadales in the amino acid based phylograms and the Enterobacterales & Pasteurellales in the nucleotide based phylograms.

4.4. Molecular docking

Our docking analysis found that fatty acids mainly docked at the S3 kink, along with some binding at the high and low affinity spots. This location of these spots coincides with previous docking analysis [14] and predictions by the study initially crystalizing the E. coli FadL [52]. However, the frequency of binding at the S3 kink does not match these previous studies. van den Berg et al. [52] suggested that the E. coli FadL first bound fatty acids at the low affinity spot then moved them to the high affinity spot and then through the channel with the help of conformational changes. This study only named the low and high affinity spots as potential binding spots for the E. coli FadL. This suggests that binding of fatty acids should only occur at the high and low affinity spots, with greater frequency at the high affinity spot given the higher binding affinity associated with this spot. Likewise, Turgeston et al. [14] found the greatest binding frequency at the high affinity spot. However, Turgeston et al. [14] also noted that their equilibrated E. coli FadL homolog exhibited the fewest dockings at the high affinity spot due to impeding amino acids. Perhaps our FadL homologs also possess similar impeding amino acids, preventing binding at the high affinity spot. This may either reveal the absence of a true high affinity binding spot in many FadL homologs or be reflective of a difference between the predicted and natural tertiary structures. Turgeston et al. [14] did find that the S3 kink exhibited more binding than the low affinity spot due to greater surface area at the S3 binding site, corroborating our findings of the same.

We hypothesized that the different FadL homologs were optimized for particular niches and bound to different fatty acids preferentially. Our molecular docking revealed a significant difference for affinities between fatty acids (p = 6.801e-10), but not FadL homolog clusters (p = 0.9569). This refutes our hypothesis and suggests that the FadL homologs co-occupy the same niche. Perhaps the importing role of the FadLs is significant enough to necessitate three separate FadL homologs fulfilling the same role, in case one or two of the homologs is mutated. Without FadLs, fatty acid synthesis is limited to the energy exhaustive de novo route, explaining this potential necessity. Alternatively, differential fatty acid binding patterns may exist for other fatty acids not surveyed here, although we surveyed the most crucial amino acids, or a survey of more FadL homologs may reveal differential fatty acid binding patterns. Future work is necessary to find a definitive answer.

4.5. Limitations

This study is not comprehensive for all homologs and species in the chosen order of Gammaproteobacteria. This may prevent completely accurate relations from being discovered. However, given the vastness of the species surveyed, the phylograms presented herein are considered representative. However, for the operon structure analysis, only one of the potential operon structures has been verified as a true operon, consisting of a FadL followed by a lipase [20]. The other potential operon structures may not even be an operon and rather simply genes tending to occur near each other.

For the molecular docking analysis, our study used predicted models from the species we surveyed as only the FadL for E. coli has been crystalized [52]. Thus, the true 3D models of these proteins may not match our predicted models. Additionally, our predicted models were not stabilized via membrane simulation, decreasing the accuracy of our models. The sample size for the statistical analysis was also relatively small, increasing the likelihood of error.

4.6. Future work

A more in-depth investigation of the operon structure involving FadL in Vibrionales species would be beneficial. Currently, one of the potential operon structures identified by this study has not been verified. Future work could verify or refute this potential operon, perhaps using the methodology described by Pride et al. [20]. For the other operon, Pride et al. [20] identified the critical role of the second protein found in the operon for the base sequence VCA0862, lipoprotein VolA. A future phylogenetic investigation of homologs of this protein seen in other Vibrionales species sharing the same operon structure may improve our understanding of both relations between species and the function of VolA in respect to FadL. Furthermore, an investigation of promoter sequences upstream of the operons would enhance our understanding of the regulation of FadL and potential difference between the multiple homologs.

Our fatty acid preferences research can be enriched by the crystallization of FadL's of more surveyed species. 3D models based on crystallization efforts will be more accurate than our predicted models. Future availability of such models will enable more in detail investigation and understanding of the potentially differing fatty acid preferences for the different homologs. Additionally, future studies can explore a wider array of fatty acids for docking. Furthermore, our methodology could be extended to FadD to investigate the structural deviations and ligand preferences for its different homologs. Again, crystallization of more homologs will aid this investigation of FadD.

5. Conclusion

Phylogenetic relations of the homologs of the surveyed proteins often matched phylogenetic relations observed for Gammaproteobacteria by prior studies. For FadL and FadD, many homologs tended to cluster with the base sequences they were blasted from rather than order, suggesting a more ancestral origin of FadL and FadD in Vibrionales, Aeromonales, and Alteromonadales prior to evolution of the canonical FadL and FadD possessed by Enterobacterales. Meanwhile for the Pls proteins, homologs clustered mainly with order. The potential operon structure analysis enriched understanding of phylogenetic relations between Vibrionales for FadL as homologs clustered based on operon structure more than other factors. Our molecular docking results revealed similar binding patterns between the different FadL homologs, suggesting the role of FadL is critical, necessitating multiple homologs to ensure function.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Award 1852042, 2149956).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fernando Alda (Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga) and Bradley Harris (Associate Professor, Civil and Chemical Engineering Department, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga) for reviewing our work and providing expert feedback. We also thank the internal support from Hong Qin (Professor, College of Engineering and Computer Science, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga), the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, and the Office of the Vice Chancellor of Research at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Footnotes

Appendix A

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101504.

Contributor Information

Saksham Saksena, Email: saksham.r.saksena@vanderbilt.edu.

Kwame Forbes, Email: kwamek@email.unc.edu.

Nipun Rajan, Email: nipunrajan3@gmail.com.

David Giles, Email: David-Giles@utc.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Appendix A: Amino Acid and Nucleotide Sequences Used in Study.

Amino Acid Sequences Record.

Nucleotide Sequences Record.

Appendix H: FadL Homolog Statistics, Docking Parameters, and Binding Affinities

FadL Homolog Statistics. The table is split into four sections. The first section is the SWISS-MODEL statistics of the originally modeled proteins. The best model (the one with the highest QMEANDisCo Global score) of the two modeled ones has the statistics highlighted in green. The second section is the SAVES statistics of this best model. The third section is the statistics from the SWISS-MODEL structure assessment of the five models from Galaxy Refine. Again, the best model (the one with the highest QMEANDisCo Global score) of the two modeled ones has the statistics highlighted in green. The fourth and final section is the SAVES statistics of this best model.

FadL Grid Box Center Coordinates. The size of all the grid boxes are cubes of side length 40. The centers of the grid boxes varied with different protein models, but the center coordinates remained constant for each protein model regardless of the ligand. The center coordinates for the grid boxes are listed here.

FadL Homolog Binding Affinities. The binding affinities (in kcal/mol) of all the FadL homologs with the ligands (linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, DHA, LDAO, and oleic acid) at the nodes (high affinity spot, low affinity spot, and S3 kink / node 3) is listed. If the fatty acid did not dock with the FadL homolog at a node, that cell is highlighted with red. The fatty acid bonding with the highest binding affinity for each FadL homolog at the high affinity spot, low affinity spot, and the S3 kink / node 3 are highlighted with yellow, pink, and green, respectively.

Automated Vina Settings Compiling Function. This function, as coded by this python script, builds configuration files.

Appendix B: Phylogenetic Results for FadL

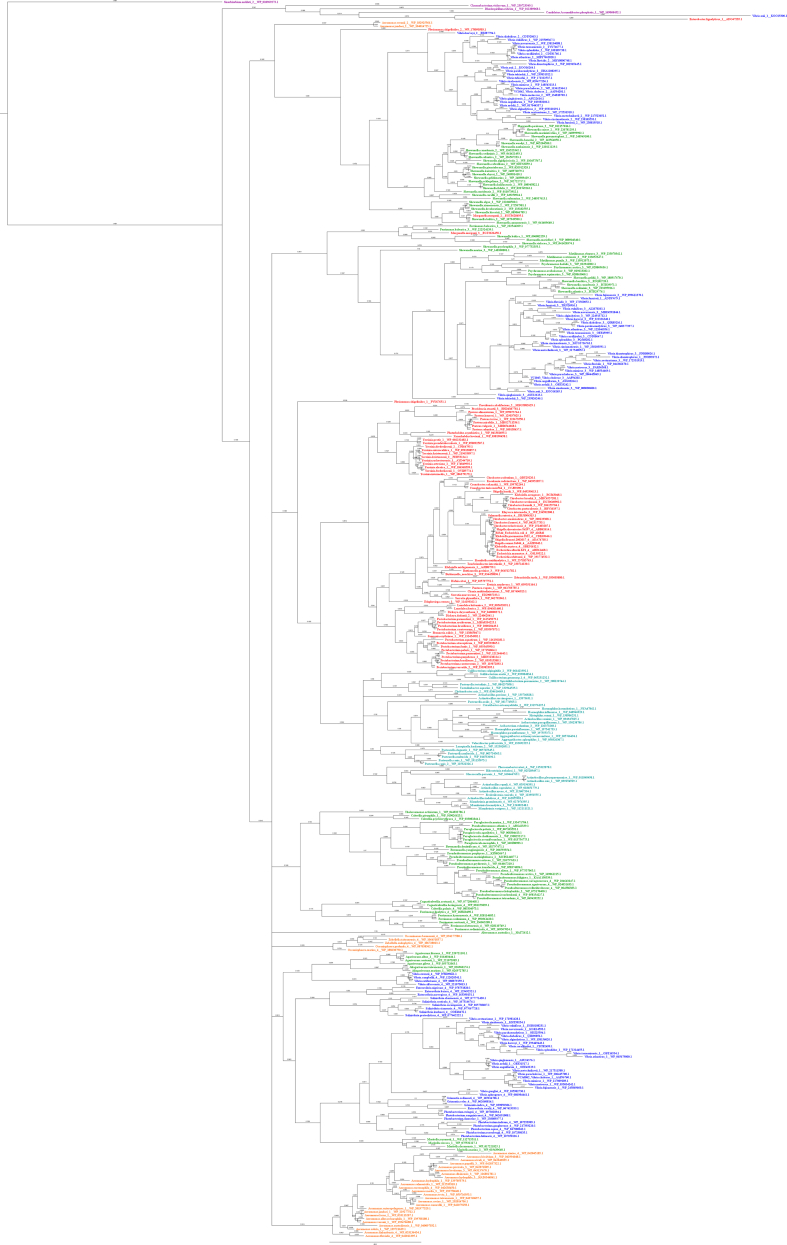

Fig. B.1.

FadL Amino Acid Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. B.2.

FadL Amino Acid Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. B.3.

Operon Analysis Results. Figure is a visual representation of the operon arrangements overlaid on the Mr. Bayes amino-acid sequence based FadL phylogram. Seven main potential operon structures exist. Homologs within the first main potential operon structure (RNA Polymerase Sigma Factor → hypothetical protein, DUF3379 domain-containing protein, or Chemotaxis protein → FadL (light blue) → FadL (dark blue)) are colored blue with the shade depending on the position of the FadL within the operon. Homologs within the second main potential operon structure (FadL → lipase) are colored red. Homologs within the third main potential operon structure (FadL → sodium/proton antiporter) are colored purple. Homologs within the fourth main potential operon structure (FadL → methylated-DNA-cysteine S-methyltransferase) are colored teal. Homologs within the fifth main potential operon structure (FadL → nuclear transport factor 2 family protein → glycerol kinase glpK) are colored light green. Homologs within the sixth main potential operon structure (FadL → MerR family DNA-binding transcriptional regulator) are colored pink. Homologs within the seventh main potential operon structure (FadL (light orange) → FadL (dark orange) → EAL domain-containing protein) are colored orange with the shade depending on the position of the FadL within the operon.

Fig. B.4.

FadL Nucleotide Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. B.5.

FadL Nucleotide Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. B.6.

Overall Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the consensus identities of each branch's consensus sequence (as seen in Figures B8-B11).

Fig. B.7.

Base Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the base sequences.

Fig. B.8.

VCA0862 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VCA0862 base sequence and 4 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. B.9.

VC1042 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC1042 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. B.10.

VC1043 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC1043 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. B.11.

b2344 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC1042 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Appendix C: Phylogenetic Results for FadD

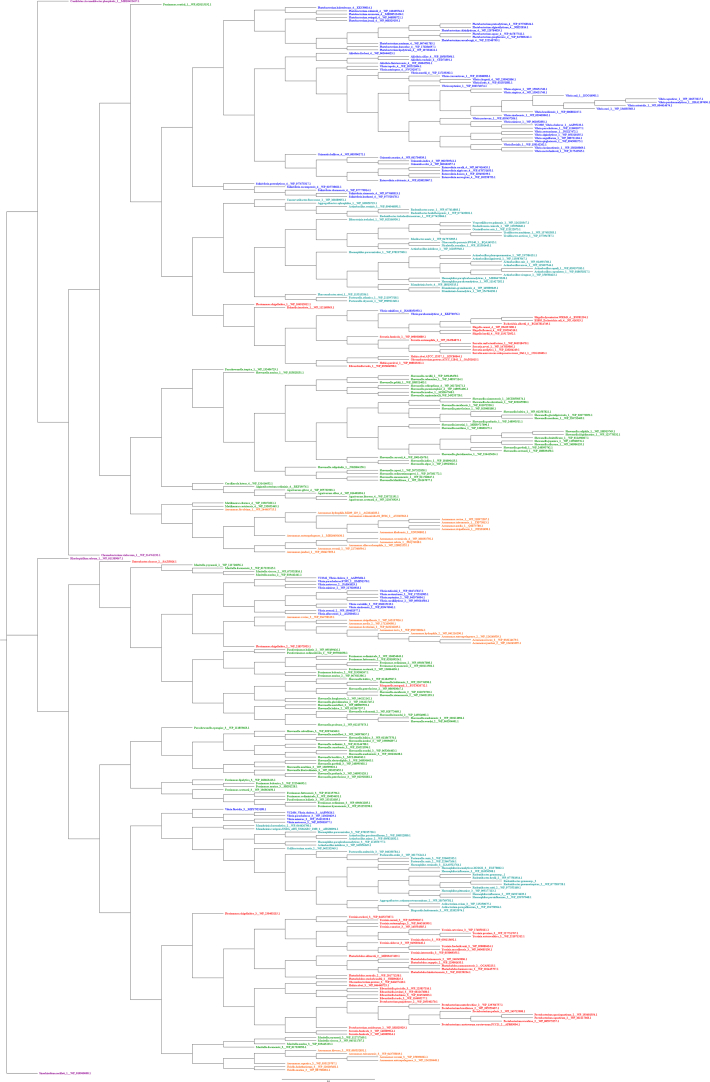

Fig. C.1.

FadD Amino Acid Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. C.2.

FadD Amino Acid Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. C.3.

FadD Nucleotide Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. C.4.

FadD Nucleotide Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. C.5.

Overall Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the consensus identities of each branch's consensus sequence (as seen in Figures C7-C10).

Fig. C.6.

Base Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the base sequences.

Fig. C.7.

VC1985 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC1985 base sequence and 4 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. C.8.

VC2341 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC2341 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. C.9.

VC2484 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC2484 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. C.10.

b1805 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of b1805 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

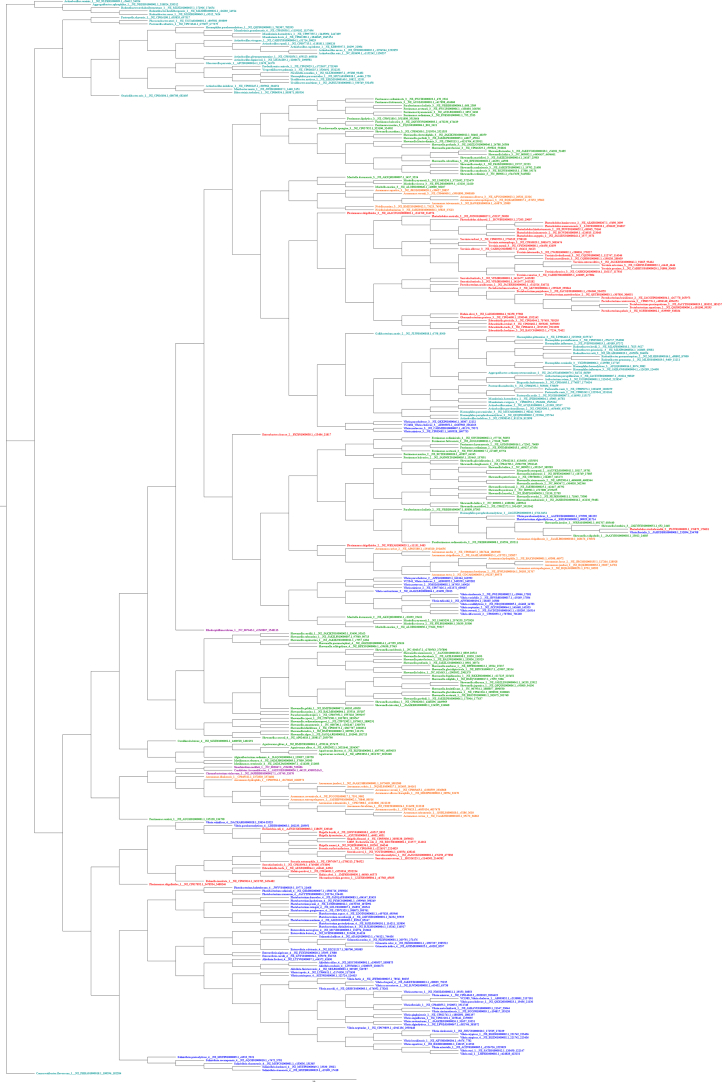

Appendix D: Phylogenetic Results for PlsB

Fig. D.1.

PlsB Amino Acid Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. D.2.

PlsB Amino Acid Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. D.3.

PlsB Nucleotide Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. D.4.

PlsB Nucleotide Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. D.5.

Overall Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the consensus identities of each branch's consensus sequence (as seen in Figures D7 and D8).

Fig. D.6.

Base Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the base sequences.

Fig. D.7.

VC0093 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of VC0093 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Fig. D.8.

b4041 Branch Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of b4041 base sequence and 3 other species found on the same branch as the base sequence.

Appendix E: Phylogenetic Results for PlsC

Fig. E.1.

PlsC Amino Acid Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. E.2.

PlsC Amino Acid Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. E.3.

PlsC Nucleotide Based Mr. Bayes Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. E.4.

PlsC Nucleotide Based RAxML Phylogram. The phylogram is color-coded by order. Vibrionales species are colored blue, Enterobacterales species are colored red, Alteromonadales species are colored green, Pasteurellales species are colored teal, Aeromonadales species are colored orange, and non-Gammaproteobacteria species (outgroup species from Alphaproteobacteria or Betaproteobacteria classes) are colored purple.

Fig. E.5.

Overall Consensus Sequence. The consensus sequence of the consensus identities of each branch's consensus sequence (as seen in Fig. 7, Fig. 8).

Fig. E.6.