Abstract

Childhood concussion may interfere with neurodevelopment and influence cognition. Females are more likely to experience persistent symptoms after concussion, yet the sex-specific impact of concussion on brain microstructure in children is understudied. This study examined white matter and cortical microstructure, based on neurite density (ND) from diffusion-weighted MRI, in 9-to-10-year-old children in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study with (n = 336) and without (n = 7368) a history of concussion, and its relationship with cognitive performance. Multivariate regression was used to investigate relationships between ND and group, sex, and age in deep and superficial white matter, subcortical structures, and cortex. Partial least square correlation was performed to identify associations between ND and performance on NIH Toolbox tasks in children with concussion. All tissue types demonstrated higher ND with age, reflecting brain maturation. Group comparisons revealed higher ND in deep and superficial white matter in females with concussion. In female but not male children with concussion, there were significant associations between ND and performance on cognitive tests. These results demonstrate a greater long-term impact of childhood concussion on white matter microstructure in females compared to males that is associated with cognitive function. The increase in ND in females may reflect premature white matter maturation.

Keywords: Pediatric, Concussion, Restriction spectrum imaging, Females, Cognition

Highlights

-

•

Female children with concussion have microstructural differences in white matter.

-

•

Brain microstructure is not notably different in male children with concussion.

-

•

White matter microstructure is related to cognition in females with concussion.

-

•

Concussion may lead to premature white matter maturation in female children.

1. Introduction

Two-thirds of all concussions occur in children, with 20–40% reporting at least one concussion before adolescence (Phil et al., 2017, Boak et al., 2020). Concussion symptoms include cognitive impairment, emotional and physical problems, and sleep dysregulation (Lambregts et al., 2018). These can influence academic performance and overall quality of life (Novak et al., 2016). Most children that experience a concussion recover within 2 weeks of injury, however, 10–30% of children experience symptoms for more than 3 months (Barlow, 2016), with females at greater risk of persistent symptoms (Ledoux et al., 2019). Little is known about the association between sex-specific effects of concussion on the developing brain and emerging cognitive abilities.

Brain microstructure matures throughout childhood. In white and gray matter, axons increase in diameter and continue to myelinate, and in white matter, axons become tightly packed together (Stiles and Jernigan, 2010). This maturation is crucial for efficient and coordinated communication in the brain that enables higher order cognitive function (Fields, 2008). In recent decades, neuronal changes during brain development have been described in vivo with diffusion MRI methods that infer microstructural properties of brain tissues through movement of water molecules (Alexander et al., 2019). These studies have observed earlier maturation of white matter microstructure in females (Lebel et al., 2019). The majority of these studies have examined fractional anisotropy (FA) from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), however, recent studies suggest measures of neurite density (ND) from advanced multi-compartment models of diffusion are more sensitive to maturation of brain microstructure (Sila et al., 2017, Zhao et al., 2021). ND derived from cylindrically restricted intracellular diffusion may reflect packing, diameter and/or myelination of axons in white and gray matter (White et al., 2013).

Mechanical forces generated by rapid acceleration and deceleration of the brain during a concussion have a diffuse impact on brain tissues. In particular, stretching and shearing of axons is followed by progressive processes that result in chronic inflammation and conduction deficits (Marion et al., 2018), with enhanced susceptibility at the gray-white matter interface (Farid et al., 2020). Unmyelinated axons in the developing brain may be especially vulnerable to disruption due to a lack of physical protection from myelin and exposure to a post-traumatic neuroinflammatory extracellular environment (Reeves et al., 2012). Diffusion MRI measures that are sensitive to maturation of brain microstructure have also been used to detect changes post-concussion (Dennis et al., 2017). Studies of pediatric concussion in the acute to post-acute phase (up to 1-month post-injury) demonstrate increased restricted diffusion (i.e. increased FA) suggesting increased axonal swelling post-injury (Wilde et al., 2008, Babcock et al., 2015, Goodrich-Hunsaker et al., 2018, Mayer et al., 2018, Ware et al., 2019, Rausa et al., 2020). Whereas, studies of pediatric concussion in the chronic phase (3–12 months) post-injury have demonstrated reductions in restricted diffusion (i.e. decreased FA), suggestive of axon injury (Mayer et al., 2012, Ewing-Cobbs et al., 2016), or no significant differences post-injury (Lancaster et al., 2018, Ware et al., 2019). The sex-specific differences in the relationship between brain microstructure and persistent symptoms post-concussion has been documented in one prior pediatric study in the acute phase post-injury (7.1 days +/- 2.1 SD). In a sample of 55 children with concussion (ages 12.5–17.9 years), this study used the ND index from neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) and found that female adolescents with concussion had lower ND in the frontal region of the cingulum bundle, a white matter region associated with emotional regulation, which was associated with higher levels of anxiety (Lima et al., 2022). Another study with a well-powered sample of children and youth with concussion (n = 132, ages 8–17 years) used DTI to investigate brain changes in the post-acute (2 weeks) to chronic (3 and 6 months) phase post-injury and found no sex-specific differences between children with and without a history of concussion. However, they did observe sex differences in white matter diffusion across the whole sample reflecting expected sex differences in age-related maturation (Ware et al., 2019). It is possible that sex differences in the relationship between white matter microstructure and persistent symptoms at a more chronic phase post-injury may reflect an interaction between injury processes and age-related maturation and have not to our knowledge been investigated.

We used advanced diffusion MRI to assess brain wide microstructure in children with a history of concussion. ND from the restriction spectrum imaging (RSI) model of diffusion MRI was assessed due to its sensitivity to the development of brain microstructure. ND derived from RSI is more favourable than DTI and NODDI as it is a specific measure of cylindrically restricted intracellular diffusion, theoretically providing more sensitivity to changes in anisotropic diffusion related myelination or axonal integrity (Palmer et al., 2022, White et al., 2013). We first investigated injury related effects in white and gray matter microstructure in 9-to-10-year-old children with (n = 336) and without (n = 7368) a history of concussion and asked if they were sex- and age-specific. We hypothesized that children with concussion would show differences in ND compared to children without concussion with potentially larger effects in females due to their enhanced vulnerability to persistent impairment after concussion. We then assessed the association between microstructure in tissue types with significant group differences and characteristics of the injury in children with concussion. Next, we assessed the association between altered tissue microstructure and performance on cognitive tests in children with concussion. We hypothesized that ND in tissue types where group differences were detected would be associated with worse performance on cognitive tests.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and demographic data

Participants were part of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study designed to investigate brain development and health. Signed informed consent was provided by all parents/or guardians and assent was obtained from children before participation in the study. The Research Ethics Board of The Hospital for Sick Children approved use of ABCD data for this study. The ABCD Study collected data on physiological, psychological, and social measures, along with neuroimaging data from 11,875 participants aged 9- to 10-years-old. Participants were recruited from 21 different sites across the United States of America (USA), and closely match the demographic characteristics of the USA population (https://abcdstudy.org/; https://abcdstudy.org/families/procedures/). All sampling, recruitment, and assessment procedures for the ABCD Study are outlined in Garavan et al. (2018). Demographic data including age, sex (defined as sex assigned at birth), and pubertal status (based on a summary score of physical development) were collected from the Physical Health measure completed by parents, and total combined family income, highest parental education, and race and ethnicity were collected from the Parent Demographics Survey. History of medication taken in the two weeks before screening was collected from the Parent Medications Survey Inventory Modified from PhenX. Any missing demographic data were imputed using the R Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (mice) package to avoid deletion of participants (Buuren et al., 2011, R Development Core Team, 2019). Siblings were randomly excluded from the sample to only include one sibling to remove any risk of Type 1 errors due to within family nesting effects (Saragosa-Harris et al., 2022). Children with a history of concussion were compared to children with no history of brain injury.

2.2. Concussion

Children with concussion were selected according to the Summary Scores of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) provided by the ABCD Study. These scores are based on information about concussion history and past head injuries collected from the Modified Ohio State University Traumatic Brain Injury Screen – Short Version (Corrigan and Bogner, 2007). This is a parent-report of children’s lifetime history of head injuries with follow-up questions about the mechanism of injury, the age at injury, and whether the child experienced any loss of consciousness or a gap in their memory. For children with multiple head injuries, information was recorded for all injuries. Children with concussion, defined as those that received a severity grading of possible mild TBI on the ABCD Summary Scores of TBI (TBI without loss of consciousness but memory loss) or mild TBI (TBI with loss of consciousness less than 30 min), were included in this study. This definition is consistent with a recently published study on the ABCD cohort that describes rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in these children (Cook et al., 2021). Time since injury is defined as the time since the first injury when the participant experienced more than one concussion.

2.3. Imaging measures

MRI, including T1-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging, was collected for all participants across 21 sites, and on 28 different scanners, including Siemens Prisma, Philips, and GE 3 T (Supplementary Table 1). MRI acquisitions, processing pipelines and quality control procedures are described in detail elsewhere (Hagler et al., 2019), and relevant details are summarized here. All participants underwent ABCD quality control, including both automated checks for the completeness of the imaging series and to confirm that the number of files matched the expected number for each series on each scanner, and manual checks to identify poor image qualities or errors from motion correction. Participants were excluded if they had missing or failed quality control (concussion: n = 13, comparison group: n = 375) as rated by the ABCD Study team, missing imaging data (concussion: n = 61, comparison group: n = 2199). Participants were also excluded if they had a diagnosis of epilepsy (concussion: n = 14, comparison group: n = 209), lead poisoning (concussion: n = 1, comparison group: n = 39), multiple sclerosis (n = 0), or cerebral palsy (concussion: n = 0, comparison group: n = 4), since the presence of these brain disorders may influence brain imaging. Of these participants, 36 children with concussion and 1123 children in the comparison group had missing or incomplete RSI data and were removed from the sample. The final sample contained 336 children with and 7368 without a history of concussion.

2.4. Restriction spectrum imaging

Multi-shell diffusion-weighted images were acquired using 1.7 isotropic resolution, multiband EPI, slice acceleration factor 3, seven b=0 frames, and four b-values at 96 diffusion directions (six directions at b=500 s/mm2, 15 directions at b=1000 s/mm2, 15 directions at b=2000 s/mm2, and 60 directions at b=3000 s/mm2). ABCD provided pre-processed region-based measures compiled across subjects and summarized in a tabulated form. The RSI model was fit using a linear estimation approach as described in Hagler et al. (2019). Diffusion MRI images were corrected for eddy current distortion, head motion, spatial, and intensity distortion, and registered to T1weighted structural images using mutual information after coarse pre-alignment via within-modality registration to atlas brains (Hagler et al., 2019, Wells et al., 1996). Cortical and subcortical gray matter segmentation was performed using FreeSurfer v5.3. Subcortical gray matter regions were labeled using an automated, atlas-based, volumetric segmentation procedure. Cortical gray matter and sub-adjacent white matter regions were labeled using surface-based nonlinear registration to the atlas based on cortical folding patterns. Major white matter tract segmentation and labeling was performed using AtlasTrack, a probabilistic atlas-based method (Hagler et al., 2019). We used mean ND values calculated for four categories of tissue: i) deep white matter, from 37 long range major white matter tracts labeled using AtlasTrack (Hagler et al., 2009), ii) superficial white matter, sub-adjacent to 68 regions of the cortex labeled using anatomical parcellation from the Desikan-Killiany atlas (Desikan et al., 2006), iii) 28 subcortical gray matter structures labeled using anatomic whole-brain segmentation (Fischl et al., 2002), and iv) cortical gray matter in 68 regions of the cortex labeled with the Desikan-Killiany atlas (Desikan et al., 2006).

2.5. Cognitive measures

We examined brain measures in relation to seven measures of cognition from the National Institute of Health (NIH) Toolbox. The Picture Vocabulary Test is a general vocabulary knowledge task that tests a child’s ability to match a picture that most closely matches the word they have been presented with. The Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test is an inhibition and conflict monitoring task that measures the ability to accurately respond to congruent versus incongruent contexts. The List Sorting Working Memory Test evaluates immediate recall and sequencing of both orally and visually presented stimuli. The Dimensional Change Card Sort Test is a measure of cognitive flexibility as children are asked to match a series of pictures to a target picture. Information processing speed was evaluated based on performance on the Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test, a measure of rapid visual processing. The Picture Sequence Memory Test assessed episodic memory. Reading decoding skills were evaluated using the Oral Reading Recognition Test. The analysis presented in this study used age-corrected standard scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 (Luciana et al., 2018).

3. Experimental design and statistical analyses

3.1. Comparisons of neurite density in children with and without concussion

Statistical analyses were performed using R (R Development Core Team, 2019). Linear mixed effects models were computed using the R lmerTest package, as demonstrated by the model formula below. Models were generated for mean ND values of each of the four tissue categories. We investigated the relationship between group, sex, age, and their interactions. Fixed effects covariates were puberty, total combined family income, and race and ethnicity, and scanner was included as a random effect. We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to confirm the best fitting model from all possible models (three-way interaction between group, sex, and age; two-way interactions between group and age with sex as a fixed effect covariate; two-way interaction between group and sex with age as a fixed covariate; and main effects only). The model with the lowest AIC value was chosen. If a model with an interaction term was selected and the interaction effect was significant, it was assessed using the emmeans package in R (R Development Core Team, 2019).

| (1) |

False discovery rate (FDR) correction was used to correct for Type 1 errors across the four tissue categories (four comparisons: deep white matter, superficial white matter, subcortical structures, and cortex).

3.2. Sensitivity analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted in subsets of the full sample to assess the robustness of the group comparisons of ND. First, children with concussion were compared to an equally sized, closely matched comparison group. The comparison group was matched on age, sex, pubertal status, total combined family income, highest parental education, race and ethnicity, and medications taken in the last two weeks before screening including antipsychotics, antidepressants, and stimulants (based on a dichotomous response scale of yes/or no). This matched sample was created using the R matchIt package (Ho et al., 2011, R Development Core Team, 2019). Second, the subset of children scanned on Siemens Prisma scanners, the most common scanner model, were examined. Linear mixed effect models as described above were generated to compare mean ND values in the concussion and comparison groups for each tissue category where differences were detected in the primary analyses.

3.3. Association between neurite density and injury variables in children with concussion

We investigated the relationship between injury characteristics and mean ND using linear mixed effects models, for tissue categories where significant differences were detected between children with and without concussion in the primary group comparison. Sex stratified analyses were also conducted to investigate any differences in female and male children with concussion. Injury characteristics included injury mechanism, number of injuries, number of injuries with loss of consciousness, number of injuries with post-traumatic amnesia, age at injury, and time since first injury. FDR correction was used to correct for Type 1 errors from multiple comparisons across analyses of each tissue category (two comparisons: deep white matter and superficial white matter).

3.4. Association between neurite density and cognitive outcome in children with concussion

Cognitive development in children is supported by the maturation of networks of white matter that may be disrupted by concussions resulting in cognitive impairment (Stojanovski et al., 2019, Darki and Klingberg, 2015, Bai et al., 2020). To identify white matter regions correlated with cognitive function in the concussion group, a partial least squares correlation (PLS-C) analysis was performed in MATLAB (Version 2017b) using McIntosh Lab’s PLS package (2017; https://github.com/McIntosh-Lab/PLS), separately for males and females and for each tissue category where differences were detected in the primary analyses (deep white matter and superficial white matter). A cross-product matrix was created between two matrices, a cognitive data matrix and a matrix with age-adjusted residuals of neurite density data in each region. The cross-product matrix was decomposed using singular value decomposition (SVD) into two matrices of mutually orthogonal singular vectors that account for maximum covariance. The relationship between these singular vectors makes up the latent variables that express the largest amount of information common to both matrices. In this analysis, the latent variables refer to the pattern of covariance between cognitive measures and neurite density of white matter regions. To determine the significance of the latent variables, permutation testing was performed with 1000 permutations, and a p value of 0.05 was used as the threshold for significance. The loadings within each latent variable give the degree to which that individual variable (i.e., cognitive measure, or brain region) contributes to the latent variable. To identify the most important variables, bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations was performed to determine the reliability of loadings, or which loadings most strongly contributed to significant latent variables (McIntosh and Nancy, 2004). In these analyses scores from the seven cognitive tests were assessed in relation to 31 deep white matter regions and 68 superficial white matter regions.

3.5. Data availability

All data used in this study is from the ABCD Study’s Curated Annual Release 2.0 (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd).

3.6. Code accessibility

Requests to access the derived data and code supporting the findings in this study should be directed to Anne Wheeler, anne.wheeler@sickkids.ca.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

This study examined children with concussion (n = 336) and children with no history of brain injury (n = 7368) who had structural and diffusion images that passed quality control. The demographic characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1 and the injury characteristics for the concussion group are presented in Table 2. For participants with more than one concussion, injury characteristics for all injuries are recorded. Age in months for the concussion group was statistically higher than the comparison group (p = .002), the concussion group had a greater number of male participants (p = .003), a greater number of participants from higher income households (p = .003), and a greater number of participants that were non-Hispanic white and fewer participants that were non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, or other/multi-racial than the comparison group (p < .001) (Table 1). The demographic differences in the of the Siemens Prisma subsample were similar (Supplementary Table 2), whereas the characteristics of the matched comparison group did not differ from the concussion group as expected (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic and characteristics.

| Concussion (n = 336) |

Comparison Group (n = 7368) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | M | F | ||

| n | 203 (60.4%) | 133 (39.6%) | 3843 (52.2%) | 3524 (47.8%) | .003 |

| Age in Months | 120 (7.50) | 121 (7.42) | 119 (7.46) | 119 (7.34) | .002 |

| Pubertal Status: | |||||

| Prepubescencea | 150 (73.9%) | 34 (25.6%) | 2691 (70.0%) | 1068 (30.3%) | .179 |

| Pubescenceb | 53 (26.1%) | 99 (74.4%) | 1153 (30.0%) | 2456 (69.7%) | |

| Family Incomec: | |||||

| < 50 K | 47 (23.2%) | 30 (22.6%) | 1179 (30.7%) | 1116 (31.7%) | .003 |

| 50–99 K | 65 (32.0%) | 33 (24.8%) | 1044 (27.2%) | 1022 (29.0%) | |

| > 100 K | 91 (44.8%) | 70 (52.6%) | 1621 (42.2%) | 1386 (39.3%) | |

| Race: | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 124 (61.1%) | 97 (72.9%) | 2098 (54.6%) | 1817 (51.6%) | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17 (8.4%) | 10 (7.5%) | 491 (12.8%) | 479 (13.6) | |

| Hispanic | 35 (17.2%) | 16 (12.0%) | 806 (21.0%) | 770 (21.9%) | |

| Asiand | 4 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 85 (2.2%) | 92 (2.6%) | |

| Other/Multi-Racial | 23 (11.3%) | 10 (7.5%) | 364 (9.5%) | 366 (10.4%) | |

M, males; F, females.

P values were calculated using the independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables (p < .05 is bolded).

Prepubescence includes children at pubertal stages 1 and 2, as defined by the Physical Health Measure completed by Parents.

Pubescence includes children at pubertal stages 3–5, as defined by the Physical Health Measure completed by Parents.

Family Income refers to total combined family income.

Asian race refers to Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, other Asian.

Table 2.

Injury characteristics of concussion group.

| Concussion (n = 336) |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||

| n | 203 (60.4%) | 133 (39.6%) | < .001 |

| Age at First Injury in Months | 77.5 (31.5) | 69.5 (35.2) | .243 |

| Time Since First Injury in Months | 43.6 (31.1) | 54 (34.5) | .226 |

| Injury Mechanism | |||

| Play/Sports | 124 (61.1%) | 82 (61.7%) | .998 |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | 9 (4.4%) | 6 (4.5%) | |

| Fight/Shot/Shaken | 5 (2.5%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

| ED Visit/Unknown Mechanisma | 55 (27.1%) | 35 (26.3%) | |

| Otherb | 10 (4.9%) | 6 (4.5%) | |

| Concussion Characteristics (injuries) | |||

| With Loss of Consciousness < 30 min | 43 (21.2%) | 36 (27.1%) | .486 |

| With Post-Traumatic Amnesia < 24 h | 177 (87.2%) | 118 (88.7%) | .324 |

| Number of Concussions | |||

| 1 | 174 (85.7%) | 117 (88.0%) | |

| 2 | 27 (13.3%) | 12 (9.0%) | |

| 3 | 2 (1.0%) | 4 (3.0%) | |

P values were calculated using chi-square test for categorical variables (p < .05 is bolded).

ED, emergency department; M, males; F, females.

Unknown mechanism of head injury that resulted in visit to the emergency department.

Any other head injuries that lead to loss of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia.

4.2. Comparisons of neurite density in children with and without concussion

4.2.1. Deep white matter

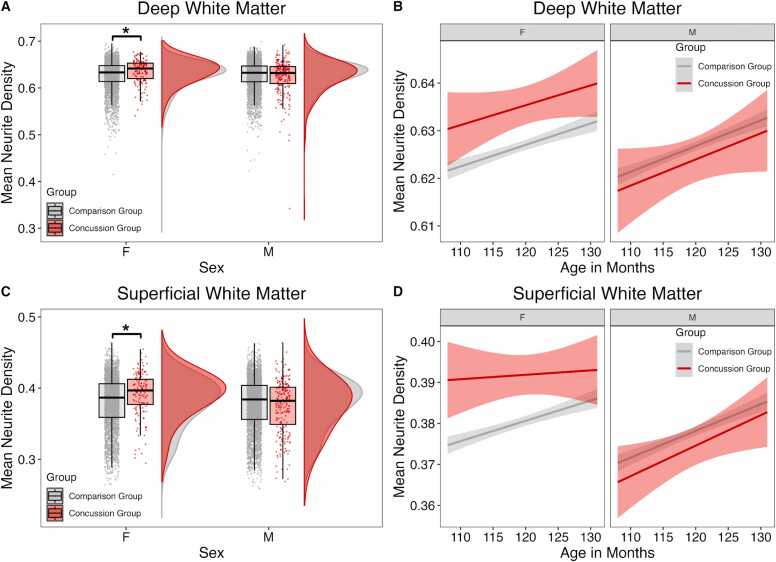

When examining mean ND in deep white matter, the best-fit model carried 83% of the cumulative model weight and included a group by sex interaction with age as a fixed effect. Group by sex interaction showed higher mean ND in deep white matter (interaction effect: β = −0.006, p = .013) in female children with concussion compared to females without concussion (sex effect: β = 0.004, p = .027) (Fig. 1A, Table 3). There were no differences between males with and without concussion (deep white matter: β = −0.002, p = .118). A significant effect of age showed with increasing age, there was higher mean ND of deep (β = 0.0004, p = <.001) white matter (Fig. 1B, Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Group differences in mean neurite density (ND) between concussion and comparison groups stratified by sex. (A & C) Mean ND in children with concussion and comparison group. Females with concussion had higher mean ND in (A) deep white matter and (C) superficial white matter. There were no group differences in males. (B & D) Regression lines showing relationships between age and mean white matter ND in children with concussion and the comparison group. (B) In the deep white matter and (D) superficial white matter, females with concussion had higher mean ND than the comparison group, and females and males in the concussion and comparison groups had similar trajectories of increasing ND with age. Asterisks indicate significant group differences (P < .05).

Table 3.

Group comparisons of mean neurite density between children with concussion and comparison group.

| Interaction |

Main Effect |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group by Sex | Female Sex | Male Sex | Group | Sex | Age | ||||||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | R2 | |

| Deep White Matter | -0.006 | .013 | 0.004 | .027 | -0.002 | .118 | - | - | -0.001 | .178 | 0.0004 | < .001 | 0.455 |

| Superficial White Matter | -0.009 | .004 | 0.007 | .001 | -0.002 | .200 | - | - | -0.003 | < .001 | 0.0005 | < .001 | 0.488 |

| Subcortical Gray Matter | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.0006 | .492 | -0.0003 | .653 | 0.0002 | < .001 | 0.666 |

| Cortical Gray Matter | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.0002 | .817 | 0.0001 | .849 | 0.0002 | < .001 | 0.500 |

Corrected p values based on FDR correction performed within analyses are reported and specified as significant (p < .05 is bolded), with comparison group as the reference group.

Main effects of sex and age are reported for all models.

Main effects for group are reported for models where no interaction terms were retained.

R2 represents conditional R2 which takes both the fixed and random effects into account.

4.2.2. Superficial white matter

When examining mean ND in superficial white matter, the best-fit model carried 61% of the cumulative model weight and included a group by sex interaction with age as a fixed effect. Group by sex interaction showed higher mean ND in superficial white matter (interaction effect: β = −0.009, p = .004) in female children with concussion compared to the females without concussion (sex effect: β = 0.007, p = .001) (Fig. 1C, Table 3). There were no differences between males with and without concussion (β = −0.002, p = .200). A significant effect of age showed with increasing age, there was higher mean ND of superficial white matter (β = 0.0005, p = <.001) (Fig. 1D, Table 3).

4.2.3. Subcortical gray matter

When examining mean ND in subcortical gray matter regions, the best-fit model carried 51% of the cumulative model weight and did not include any interaction effects. There were no significant differences in mean ND between children with and without concussion in subcortical gray matter and no significant effects of sex (Table 3). With increasing age, there was higher mean ND (Table 3).

4.2.4. Cortical gray matter

When examining mean ND in cortical gray matter regions, the best-fit model carried 43% of the cumulative model weight and did not include any interaction effects. There were no significant differences in mean ND between children with and without concussion in cortical gray matter and no significant effects of sex (Table 3). With increasing age, there was higher mean ND (Table 3).

4.2.5. Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses of group comparisons of mean ND showed a similar pattern of results. Females with concussion showed higher mean ND in superficial white matter when compared to a closely matched comparison group (Supplementary Figure 1; β = 0.007, p = .089), as well as when only the subset of children scanned on the Siemens Prisma scanners were examined (Supplementary Figure 2; β = 0.006, p = .026). Comparisons of mean ND in deep white matter similarly revealed higher ND in females with concussion, however these comparisons did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Table 4).

4.3. Association between neurite density and injury characteristics in children with concussion

4.3.1. Deep white matter

Children with a concussion from a motor vehicle crash had lower ND in deep white matter (β = −0.018, p = .039). All other injury variables were not significantly associated with ND in deep white matter (Supplementary Table 5).

4.3.2. Superficial white matter

Sex-stratified analyses demonstrated that injury from play or sports was associated with higher ND of superficial white matter in males (β = 0.010, p = .049), but not in females. All other injury variables were not significantly associated with ND in superficial white matter (Supplementary Table 5).

4.4. Association between neurite density and cognitive outcome in children with concussion

4.4.1. Deep white matter

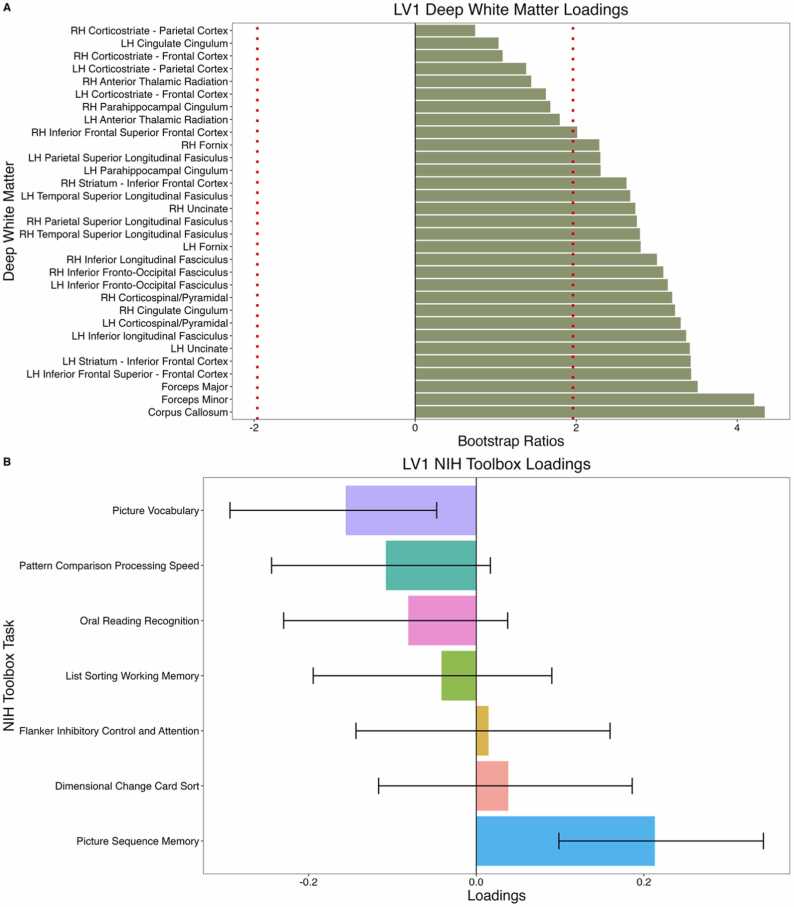

PLS-C did not reveal any significant latent variables in males. In females, PLS-C revealed one significant latent variable (LV1; p = .001, singular value = 1.18). Higher ND in the corpus collosum, forceps major, and forceps minor was significantly associated with better performance on the Picture Sequence Memory Test and worse performance on the Picture Vocabulary Test (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between deep white matter neurite density and scores on cognitive measures of the NIH Toolbox. (A) Deep white matter loadings that contribute to LV1. Dotted red line indicates loadings with bootstrap ratios greater than |1.96| (equivalent to a p value of .05). Deep white matter tracts with the highest loadings include the corpus collosum, forceps major, and forceps minor. (B) Loadings of cognitive measures that contribute to LV1. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals and significant loadings have error bars that do not cross 0. Significant cognitive measures include the Picture Sequence Memory (positive association with ND) Test and Picture Vocabulary Test (negative association with ND). LH: Left hemisphere; RH: Right hemisphere.

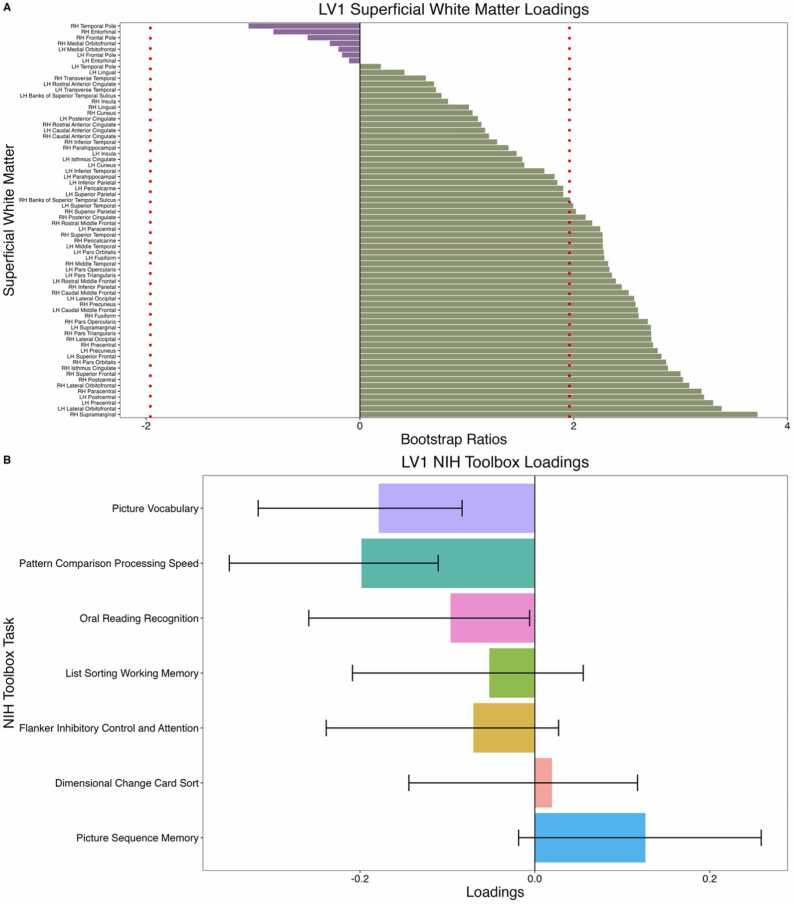

4.4.2. Superficial white matter

PLS-C did not reveal any significant latent variables in males. In females, PLS-C revealed one significant latent variable (LV1; p = .008, singular value = 1.70). Higher ND in superficial white matter adjacent to the right supramarginal, left lateral orbitofrontal, and left precentral gyri were associated with worse performance on the Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test and Picture Vocabulary Test (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between superficial white matter neurite density and scores on cognitive measures of the NIH Toolbox. (A) Superficial white matter loadings that contribute to LV1. Dotted red line indicates loadings with bootstrap ratios greater than |1.96| (equivalent to a p value of.05). Superficial white matter tracts with the highest loadings include the right supramarginal, left lateral orbitofrontal, and left precentral gyri. (B) Loadings of cognitive measures that contribute to LV1. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals and significant loadings have error bars that do not cross 0. Significant cognitive measures include the Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test (negative association with ND) and Picture Vocabulary Test (negative association with ND). LH: Left hemisphere; RH: Right hemisphere.

5. Discussion

This study investigated cortical and white matter microstructure in 9-to-10-year-old children with and without concussion from the ABCD Study, using advanced diffusion MRI. ND derived from RSI showed a robust positive relationship with age across all brain tissue categories, older age was associated with higher ND. Increased ND was detected in superficial and deep white matter regions in females with a history of concussion compared to females without a history of concussion. When examining the relationship between altered microstructure and cognitive performance in children with concussion, higher ND in the corpus collosum, forceps major, forceps minor, and superficial white matter of the right supramarginal, left lateral orbitofrontal, and left precentral gyri was associated with worse performance on vocabulary and processing speed tasks. The apparent state of premature white matter in females with concussion may reflect an altered trajectory of maturation or a recovery response from initial white matter injury which influence performance on cognitive tests.

Expected differences in brain microstructure related to age and sex were detected. Despite the narrow age range of 9-to-10-years-old included in this study, small but robust positive relationships between age and ND were observed in white and gray matter. White matter and gray matter microstructural changes are evident in typical brain development (Norbom et al., 2021). Prior diffusion MRI studies have demonstrated that throughout childhood, there is a steady increase in directionally restricted diffusion in white matter measured as FA from the commonly used simpler DTI model (Lebel, Treit, and Beaulieu, 2019), and ND from another advanced multicompartment model, neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) (Zhao et al., 2021). ND from both the NODDI model and the RSI model used in this study is more specific to brain microstructure than FA as it reflects intracellular directional diffusion which in the developing white matter is likely due to increased axon diameter, more densely packed axons, and/or increasing myelination leading to reduced water exchange (White et al., 2013). Literature investigating age-related changes in cortical gray matter report initial cortical thickening followed by cortical thinning of frontotemporal regions with age (Moura et al., 2017), which may be due to increasing synaptic pruning (Moura et al., 2017), as well as age-related increases in myelin content (Norbom et al., 2021). As pruning and associated reductions in dendritic arborization would be expected to decrease ND, the age-related increases in ND observed in cortical and subcortical gray matter in this study are likely driven by this increased myelin content (White et al., 2013). The current study also detected a main effect of sex in superficial white matter indicating that females have higher ND than males, consistent with reports that female children show earlier diffusion changes compared to males (Lebel, Treit and Beaulieu, 2019).

When comparing brain microstructure in children with and without concussion, differences were detected in superficial and deep white matter regions, but not in cortical or subcortical gray matter. These findings support the vulnerability of white matter to chronic effects of concussion (Shrey et al., 2011), and support current literature that reports differences relative to controls, and changes over time in diffusion measures in white matter after concussion in childhood (Lindsey et al., 2019). Moreover, we observed stronger and more robust differences in superficial white matter than in deep white matter as these remained significant in the sensitivity analysis with the closely matched comparison group as well as the sensitivity analysis in the subset of children scanned on the Siemens Prisma scanners. This may be due to the protracted time course of superficial white matter myelination making it more vulnerable to childhood injury (Oyefiade et al., 2018). Damage to superficial white matter fibers has been reported in post-mortem studies of traumatic brain injury (McKee et al., 2015), and diffusion differences in superficial white matter related to concussion were recently described by our group in another large pediatric population cohort with a wider age range (Stojanovski et al., 2019). The complex patterns of crossing fibers in these short tracts are likely more accurately captured in the current study due to the use of RSI over the simpler DTI model (Kirilina et al., 2020).

In this study, the timing of injury relative to the detected white matter differences, and the age of the participants are critical aspects to consider when placing the results in the context of existing studies of white matter microstructure in children with concussion. The children in the current study were assessed an average of almost four years after concussion, thus the increase in ND is unlikely to reflect acute injury effects and the direction of effect is inconsistent with previous studies that described less restricted diffusion (i.e. decreased FA) at chronic timepoints (Mayer et al., 2012, Ware et al., 2019, Ewing-Cobbs et al., 2016, Lancaster et al., 2018). Unique aspects of the current study may explain the apparent discrepancy. First, the restricted age range of 9- to 10-year-olds is at the lower end of the age ranges included in previous studies which may have increased the sensitivity of the group comparison as it reduced developmental heterogeneity in the sample. Second, the large sample size in this study exceeds previous studies allowing for the detection of small effects. Third, the use of multi-compartment diffusion MRI modeling rather than the more common DTI model may allow for more sensitive and specific estimates of brain microstructure (Kirilina et al., 2020). Considering the existing literature, unique aspects of the current study, and strong association between ND and age, it is intriguing that higher ND observed in female children with past concussion reflects a state of premature maturation. As increased ND may reflect increased axon diameter, more densely packed axons and/or increased myelination, the maturation of one or more of these structural features of white matter may have been accelerated by primary or secondary effects of the injury. Another interpretation that is not mutually exclusive is that the primary or secondary effects of the injury initially damaged white matter and the apparent advanced maturational state of white matter in female children with past concussion is the consequence of the recovery response that involved increased axon diameter, more densely packed axons and/or increased myelination (Armstrong et al., 2016). Of note comparable profiles of atypical development of brain connectivity have been observed following pre- and post-natal adversity in other studies (Gee et al., 2013, Kar et al., 2021).

The current study showed female specific differences in diffusion measures between children with and without concussion. Supportive of the interpretation that it is not an artifact of the sample, this effect remained when comparing females with concussion to a non-concussion group that was closely matched on demographic factors including pubertal status and family income. Previous studies that investigated post-acute diffusion in white matter microstructure following concussion did not detect significant interaction effects between sex and concussion (Goodrich-Hunsaker et al., 2018, Ware et al., 2019), suggesting that sex specific effects of concussion on white matter microstructure may only emerge once the physiological changes induced by concussion have had time to interact with neurodevelopmental processes. Considering the earlier maturation of females, it will be interesting to investigate if differences in white matter microstructure between males with and without concussion emerge at older ages.

When evaluating cognitive performance in children with concussion, significant associations between ND and performance on the processing speed, vocabulary, and episodic memory tasks were detected, but not between ND and performance on the attention, reading, or working memory tasks. Previous studies have identified attention and processing speed (Mayer et al., 2012, Lambregts et al., 2018), as well as executive function (Chadwick et al., 2021), as cognitive domains that are particularly impaired after concussion in children, though impairments after a childhood concussion normalize in 70–90% of children 3–12 months post-injury (Barlow, 2016). Consistent with group differences in brain microstructure that were specific to females, associations between brain microstructure and cognitive performance were detected in females but not males. The current study showed increased ND in the deep white matter was associated with better performance on the episodic memory task in females. This was unexpected as increased ND was associated with concussion and earlier work that examined associations between diffusion measures in white matter and these cognitive domains found that more restricted diffusion (higher FA) was associated with worse episodic memory (Wu et al., 2010). Increased ND in deep white matter was associated with worse performance on the general vocabulary task, and increased ND in superficial white matter was associated with worse processing speed performance and worse performance on the general vocabulary task in female children with concussion. These results are consistent with the interpretation that increased ND is maladaptive and are consistent with an earlier study that showed more restricted diffusion in white matter (higher FA) was negatively correlated with attention and language functions in the acute phase post-injury which persisted until 6 months post-injury (Veeramuthu et al., 2015). Future longitudinal research in prospective samples of children with concussion may be able to determine if the differences and associations detected here provide insight into the neurobiological mechanisms of increased prevalence of persistent symptoms in female children with concussion (Zemek et al., 2016).

Some aspects of the study sample and methodology limit the conclusions that can be made from these analyses. First, the children with concussion were identified based on concussion history from a parent-report measure completed retrospectively. Second, the children with concussion experienced their injury at a wide range of ages, which may have differential effects on brain development. However, an effect of age at injury on white matter microstructure was not detected when assessing the effect of injury variables on brain microstructure. Third, despite the inclusion of possible confounding factors as covariates in the statistical models and sensitivity analysis in a closely matched comparison sample, the cross-sectional design of this study means that we cannot rule out that differences in brain white matter are associated with a factor that predisposed females to brain injury rather than were a consequence of brain injury. Fourth, due to the heterogeneity of brain regions impacted by concussion, we did not hypothesize region-specific effects of injury and instead examined whole brain effects of mean ND across four tissue categories (deep white matter, superficial white matter, subcortical gray matter, and cortical gray matter). This may have obscured any effects specific to vulnerable brain regions and may have contributed to the small effect sizes observed in our analyses. Furthermore, although RSI allows for the distinction between intracellular and extracellular water diffusion and provides more specific information than DTI, the exact microstructural drivers of the observed differences in ND are not known. Lastly, although scanner was included as a random effect, we did not perform site or scanner harmonization of the imaging measure used. Well-validated harmonization techniques may help to reduce any variance from the use of different scanners or acquisition protocols across sites.

6. Conclusion

This study identified increased ND in white matter of female children aged 9–10 years with a history of concussion. These differences may reflect premature maturation of white matter with a possible influence on cognition. This study used multi-compartmental diffusion MRI to investigate the sex-specific effects of childhood concussion on white matter microstructure and lays the foundation for future analyses that track the maturation of white matter in these children.

Data statement

All data used in this study is from the ABCD Study’s Curated Annual Release 2.0 (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd). Requests to access the derived data and code supporting the findings in this study should be directed to Anne Wheeler, anne.wheeler@sickkids.ca.

Funding

This project has been made possible with the financial support of Health Canada, through the Canada Brain Research Fund, an innovative partnership between the Government of Canada (through Health Canada) and Brain Canada, and of the Azrieli Foundation in the form of an Azrieli Future Leader in Canadian Brain Research grant awarded to ALW. EN was supported by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS). SS was supported by a Restracomp Scholarship from the Hospital for Sick Children and the OGS. SHA currently receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH114879), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Academic Scholars Award from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Autism Speaks and the CAMH Foundation. SES currently receives funding from the CIHR, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Mental Health Research Canada, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Azrieli Foundation, and the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Appendix A

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101275.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Data Availability

Requests to access the derived data and code supporting the findings in this study should be directed to Anne Wheeler, anne.wheeler@sickkids.ca. All data used in this study is from the ABCD Study’s Curated Annual Release 2.0 (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd).

References

- Alexander Daniel C., Tim B.Dyrby, Nilsson Markus, Zhang Hui. Imaging brain microstructure with diffusion MRI: practicality and applications. NMR Biomed. 2019;32(4) doi: 10.1002/nbm.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong Regina C., Amanda J.Mierzwa, Marion Christina M., Genevieve M.Sullivan. White matter involvement after TBI: clues to axon and myelin repair capacity. Exp. Neurol. Trauma. Brain Inj. 2016;275(January):328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock Lynn, Yuan Weihong, Leach James, Nash Tiffany, Wade Shari. White matter alterations in youth with acute mild traumatic brain injury. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. 2015;8(4):285–296. doi: 10.3233/PRM-150347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Lijun, Guanghui Bai Shan Wang, Xuefei Yang Shuoqiu Gan, Xiaoyan Jia Bo. Yin, Yan Zhihan. Strategic white matter injury associated with long‐term information processing speed deficits in mild traumatic brain injury. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020;41(15):4431–4441. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow Karen M. Postconcussion syndrome: a review. J. Child Neurol. 2016;31(1):57–67. doi: 10.1177/0883073814543305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boak, Angela, Tara Elton-Marshall, Robert E.Mann, Joanna L. Henderson, and Hayley A. Hamilton. 2020. “The Mental Health and Well-Being of Ontario Students, 1991–2019: Detailed Findings from the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS).” 2020. 〈https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf---osduhs/osduhs-mh-report2019-pdf.pdf?la=en&hash=B09A32093B5D6ABD401F796CE0A59A430D261C32〉.

- Buuren, van Stef, Groothuis-Oudshoorn Karin. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011;45(1):1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick Leah, Roth Elizabeth, Minich Nori M., Taylor H.Gerry, Bigler Erin D., Cohen Daniel M., Bacevice Ann, et al. Cognitive outcomes in children with mild traumatic brain injury: an examination using the national institutes of health toolbox cognition battery. J. Neurotrauma. 2021;38(18):2590–2599. doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook Nathan, Elliott Karr Justin, Iverson Grant. Children with ADHD have a greater lifetime history of concussion: results from the ABCD study. J. Neurotrauma. 2021 doi: 10.1089/neu.2021.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan John D., Bogner Jennifer. Initial reliability and validity of the Ohio State university TBI identification method. J. Head. Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(6):318–329. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300227.67748.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darki Fahimeh, Klingberg Torkel. The role of fronto-parietal and fronto-striatal networks in the development of working memory: a longitudinal study. Cereb. Cortex. 2015;25(6):1587–1595. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis Emily L., Babikian Talin, Giza Christopher C., Thompson Paul M., Asarnow Robert F. Diffusion MRI in pediatric brain injury. Child’s Nerv. Syst.: ChNS: Off. J. Int. Soc. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2017;33(10):1683–1692. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3522-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan Rahul S., Ségonne Florent, Fischl Bruce, Quinn Brian T., Dickerson Bradford C., Blacker Deborah, Buckner Randy L., et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on mri scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage. 2006;31(3):968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing-Cobbs Linda, Johnson Chad Parker, Juranek Jenifer, DeMaster Dana, Prasad Mary, Duque Gerardo, Kramer Larry, Cox Charles S., Paul R.Swank. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging after pediatric traumatic brain injury: impact of age at injury and time since injury on pathway integrity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016;37(11):3929–3945. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid Alisafaei, Gong Ze, Johnson Victoria E., Dollé Jean-Pierre, Smith Douglas H., Shenoy Vivek B. Mechanisms of local stress amplification in axons near the gray-white matter interface. Biophys. J. 2020;119(7):1290–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields R.Douglas. White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(7):361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl Bruce, David H.Salat, Busa Evelina, Albert Marilyn, Dieterich Megan, Haselgrove Christian, van der Kouwe Andre, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H., Bartsch H., Conway K., Decastro A., Goldstein R.Z., Heeringa S., Jernigan T., Potter A., Thompson W., Zahs D. Recruiting the ABCD sample: design considerations and procedures. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci., Adolesc. Brain Cogn. Dev. (ABCD) Consort.: Ration., Aims, Assess. Strategy. 2018;32(August):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee Dylan G., Gabard-Durnam Laurel J., Flannery Jessica, Goff Bonnie, Humphreys Kathryn L., Telzer Eva H., Hare Todd A., Bookheimer Susan Y., Tottenham Nim. Early developmental emergence of human amygdala-prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110(39):15638–15643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307893110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker Naomi J., Tracy J.Abildskov, Black Garrett, Bigler Erin D., Cohen Daniel M., Mihalov Leslie K., Bangert Barbara A., Taylor H.Gerry, Yeates Keith O. Age- and sex-related effects in children with mild traumatic brain injury on diffusion magnetic resonance imaging properties: a comparison of voxelwise and tractography methods. J. Neurosci. Res. 2018;96(4):626–641. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler Donald J., Ahmadi Mazyar E., Kuperman Joshua, Holland Dominic, McDonald Carrie R., Halgren Eric, Dale Anders M. Automated white-matter tractography using a probabilistic diffusion tensor atlas: application to temporal lobe epilepsy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30(5):1535–1547. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler Donald J., Sean N.Hatton, Cornejo M.Daniela, Makowski Carolina, Fair Damien A., Anthony Steven Dick, Sutherland Matthew T., et al. Image processing and analysis methods for the adolescent brain cognitive development study. NeuroImage. 2019;202 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116091. November. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Daniel, Kosuke Imai Gary King, Elizabeth A.Stuart. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 2011;42(1):1–28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v042.i08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar Preeti, Jess E.Reynolds, Melody N., Grohs W.Ben, Gibbard Carly, McMorris Christina, Tortorelli, Lebel Catherine. White matter alterations in young children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev. Neurobiol. 2021;81(4):400–410. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilina Evgeniya, Saskia Helbling Markus Morawski, Kerrin Pine Katja Reimann, Steffen Jankuhn Juliane Dinse, et al. Superficial white matter imaging: contrast mechanisms and whole-brain in vivo mapping. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(41) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambregts S.A.M., Smetsers J.E.M., Verhoeven I.M.A.J., de Kloet A.J., van de Port I.G.L., Ribbers G.M., Catsman-Berrevoets C.E. Cognitive function and participation in children and youth with mild traumatic brain injury two years after injury. Brain Inj. 2018;32(2):230–241. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1406990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster Melissa A., Timothy B.Meier, Olson Daniel V., McCrea Michael A., Nelson Lindsay D., Tugan Muftuler L. Chronic differences in white matter integrity following sport‐related concussion as measured by diffusion MRI: 6–month follow‐up. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39(11):4276–4289. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel Catherine, Treit Sarah, Beaulieu Christian. A review of diffusion MRI of typical white matter development from early childhood to young adulthood. NMR Biomed. 2019;32(4) doi: 10.1002/nbm.3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux Andrée-Anne, Tang Ken, Yeates Keith O., Pusic Martin V., Boutis Kathy, Craig William R., Gravel Jocelyn, et al. Natural Progression of symptom change and recovery from concussion in a pediatric population. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(1) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, João Paulo, Kontos Anthony P., Holland Cynthia L., Suss Stephen J., Stiffler Richelle S., Bitzer Hannah B., Colorito Adam T., et al. The role of puberty and sex on brain structure in adolescents with anxiety following concussion. Biol. Psychiatry.: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2022.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, Hannah M., Elisabeth A.Wilde, Caeyenberghs Karen, Dennis Emily L. Longitudinal neuroimaging in pediatric traumatic brain injury: current state and consideration of factors that influence recovery. Front. Neurol. 2019:10. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M., Bjork J.M., Nagel B.J., Barch D.M., Gonzalez R., Nixon S.J., Banich M.T. Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;32(February):67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion Christina M., Radomski Kryslaine L., Cramer Nathan P., Galdzicki Zygmunt, Armstrong Regina C. Experimental traumatic brain injury identifies distinct early and late phase axonal conduction deficits of white matter pathophysiology, and reveals intervening recovery. J. Neurosci. 2018;38(41):8723–8736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0819-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer Andrew R., Josef M.Ling, Yang Zhen, Pena Amanda, Yeo Ronald A., Klimaj Stefan. Diffusion abnormalities in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2012;32(50):17961–17969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3379-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer Andrew R., Kaushal Mayank, Dodd Andrew B., Hanlon Faith M., Shaff Nicholas A., Mannix Rebekah, Master Christina L., et al. Advanced biomarkers of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury: progress and perils. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018;94(November):149–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh Anthony Randal, Nancy J.Lobaugh. Partial least squares analysis of neuroimaging data: applications and advances. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S250–S263. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee Ann C., Stein Thor D., Kiernan Patrick T., Alvarez Victor E. The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Pathol. (Zur., Switz. ) 2015;25(3):350–364. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura L.M., Crossley N.A., Zugman A., Pan P.M., Gadelha A., Del Aquilla M. a G., Picon F.A., et al. Coordinated brain development: exploring the synchrony between changes in grey and white matter during childhood maturation. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(3):808–817. doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbom Linn B., Ferschmann Lia, Parker Nadine, Agartz Ingrid, Andreassen Ole A., Paus Tomáš., Westlye Lars T., Tamnes Christian K. New insights into the dynamic development of the cerebral cortex in childhood and adolescence: integrating macro- and microstructural MRI findings. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak Zuzana, Aglipay Mary, Barrowman Nick, Yeates Keith O., Beauchamp Miriam H., Gravel Jocelyn, Freedman Stephen B., et al. Association of persistent postconcussion symptoms with pediatric quality of life. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12) doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyefiade Adeoye A., Stephanie Ameis, Lerch Jason P., Rockel Conrad, Szulc Kamila U., Scantlebury Nadia, Decker Alexandra, Jefferson Jaleel, Spichak Simon, Mabbott Donald J. Development of short-range white matter in healthy children and adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39(1):204–217. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Diliana Pecheva Clare E., Iversen John R., Hagler Donald J., Sugrue Leo, Nedelec Pierre, Chieh Fan Chun, Thompson Wesley K., Jernigan Terry L., Dale Anders M. Microstructural development from 9 to 14 years: evidence from the ABCD study. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022;53(February) doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2021.101044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phil Veliz, McCabe Sean E., Eckner James T., Schulenberg John E. Prevalence of concussion among US adolescents and correlated factors. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1180–1182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2019. “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.” Vienna, Austria. 〈http://www.R-project.org〉.

- Rausa Vanessa C., Shapiro Jesse, Seal Marc L., Davis Gavin A., Anderson Vicki, Babl Franz E., Veal Ryan, Parkin Georgia, Ryan Nicholas P., Takagi Michael. Neuroimaging in paediatric mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020;118(November):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, Thomas M., Smith Terry L., Williamson Judy C., Phillips Linda L. Unmyelinated axons show selective rostrocaudal pathology in the corpus callosum following traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012;71(3):198–210. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182482590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragosa-Harris, Natalie M., Chaku Natasha, MacSweeney Niamh, Victoria Guazzelli Williamson, Scheuplein Maximilian, Feola Brandee, Cardenas-Iniguez Carlos, et al. A practical guide for researchers and reviewers using the ABCD study and other large longitudinal datasets. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022;55(June) doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrey Daniel W., Grace S.Griesbach, Christopher C.Giza. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America 2011 the pathophysiology of concussions in youth. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. North Am. 2011;22(4):577–602. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sila Genc, Malpas Charles B., Holland Scott K., Beare Richard, Silk Timothy J. Neurite density index is sensitive to age related differences in the developing brain. NeuroImage. 2017;148(March):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles Joan, Jernigan Terry L. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010;20(4):327–348. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovski Sonja, Nazeri Arash, Lepage Christian, Ameis Stephanie, Voineskos Aristotle N., Wheeler Anne L. Microstructural abnormalities in deep and superficial white matter in youths with mild traumatic brain injury. NeuroImage: Clin. 2019;24(January) doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramuthu Vigneswaran, Narayanan Vairavan, Li Kuo Tan, Delano-Wood Lisa, Chinna Karuthan, William Bondi Mark, Waran Vicknes, Ganesan Dharmendra, Ramli Norlisah. Diffusion tensor imaging parameters in mild traumatic brain injury and its correlation with early neuropsychological impairment: a longitudinal study. J. Neurotrauma. 2015;32(19):1497–1509. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware Ashley L., Shukla Ayushi, Goodrich-Hunsaker Naomi J., Lebel Catherine, Wilde Elisabeth A., Abildskov Tracy J., Bigler Erin D., et al. Post-acute white matter microstructure predicts post-acute and chronic post-concussive symptom severity following mild traumatic brain injury in children. NeuroImage: Clin. 2019;25(December) doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells W.M., Viola P., Atsumi H., Nakajima S., Kikinis R. Multi-modal volume registration by maximization of mutual information. Med. Image Anal. 1996;1(1):35–51. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Nathan S., Leergaard Trygve B., Helen D′Arceuil Jan G.Bjaalie, Dale Anders M. Probing tissue microstructure with restriction spectrum imaging: histological and theoretical validation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013;34(2):327–346. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde E.A., McCauley S.R., Hunter J.V., Bigler E.D., Chu Z., Wang Z.J., Hanten G.R., et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of acute mild traumatic brain injury in adolescents. Neurology. 2008;70(12):948–955. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000305961.68029.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Trevor C., Elisabeth A.Wilde, Bigler Erin D., Yallampalli Ragini, McCauley Stephen R., Troyanskaya Maya, Chu Zili, et al. Evaluating the relationship between memory functioning and cingulum bundles in acute mild traumatic brain injury using diffusion tensor imaging. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27(2):303–307. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemek Roger, Barrowman Nick, Freedman Stephen B., Gravel Jocelyn, Gagnon Isabelle, McGahern Candice, Aglipay Mary, et al. Clinical risk score for persistent postconcussion symptoms among children with acute concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014–1025. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Xueying, Jingjing Shi, Fei Dai, Lei Wei, Zhang Boyu, Yu Xuchen, Wang Chengyan, Zhu Wenzhen, Wang He. Vol. 15. 2021. Brain Development From Newborn To Adolescence: Evaluation By Neurite Orientation Dispersion And Density Imaging. (Frontiers in Human Neuroscience). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study is from the ABCD Study’s Curated Annual Release 2.0 (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd).

Requests to access the derived data and code supporting the findings in this study should be directed to Anne Wheeler, anne.wheeler@sickkids.ca. All data used in this study is from the ABCD Study’s Curated Annual Release 2.0 (https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd).