Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori is a gastrointestinal pathogen that infects around half of the world's population. H. pylori infection is the most severe known risk factor for gastric cancer (GC), which is the second highest cause of cancer-related deaths globally. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the global prevalence of GC in H. pylori-infected individuals.

Methods

We performed a systematic search of the PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases for studies of the prevalence of GC in H. pylori-infected individuals published from 1 January 2011 to 20 April 2021. Metaprop package were used to calculate the pooled prevalence with 95% confidence interval. Random-effects model was applied to estimate the pooled prevalence. We also quantified it with the I2 index. Based on the Higgins classification approach, I2 values above 0.7 were determined as high heterogeneity.

Results

Among 17,438 reports screened, we assessed 1053 full-text articles for eligibility; 149 were included in the final analysis, comprising data from 32 countries. The highest and lowest prevalence was observed in America (pooled prevalence: 18.06%; 95% CI: 16.48 − 19.63; I2: 98.84%) and Africa (pooled prevalence: 9.52%; 95% CI: 5.92 − 13.12; I2: 88.39%). Among individual countries, Japan had the highest pooled prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients (Prevalence: 90.90%:95% CI: 83.61–95.14), whereas Sweden had the lowest prevalence (Prevalence: 0.07%; 95% CI: 0.06–0.09). The highest and lowest prevalence was observed in prospective case series (pooled prevalence: 23.13%; 95% CI: 20.41 − 25.85; I2: 97.70%) and retrospective cohort (pooled prevalence: 1.17%; 95% CI: 0.55 − 1.78; I 2: 0.10%).

Conclusions

H. pylori infection in GC patients varied between regions in this systematic review and meta-analysis. We observed that large amounts of GCs in developed countries are associated with H. pylori. Using these data, regional initiatives can be taken to prevent and eradicate H. pylori worldwide, thus reducing its complications.

Keywords: Infection, Prevalence, Gastric cancer, Helicobacter pylori, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a bacterial pathogen associated with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of over 50% of the world’s population [1]. H. pylori, is a Gram-negative spiral-shaped bacterium that colonizes the stomach, was graded as a Group I carcinogen in 1994 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [2]. With its flagella, H. pylori is capable of moving and can survive on stomach acids, leading to colonization of GI tract cells and irritation and inflammation [3]. Epidemiologic and clinical data have demonstrated the role of H. pylori in up to 75% of non-cardia gastric malignancies and up to 98% of gastric cardia malignancies [4]. There is a strong correlation between gastric cancer (GC) and H. pylori infection [5].

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer in the world and has the third highest mortality rates, for both sexes [6]. In 2020, actually 1.09 million new GC cases and 0.77 million deaths from GC was estimated all over the world [7]. The overall yearly incidence rates globally are 15.6 to 18.1 and 6.7 to 7.8 per 100,000 individuals in men and women, respectively [8]. According to anatomical subsites, GC can be classified into two categories: cardia GC and non-cardia GC [9]. Cardia and non-cardia GC are treated as two different diseases due to different epidemiological characteristics and distinct pathogeneses. Non-cardia GC is more common than cardia GC. Non-cardia GC accounted for up to 82% of all GC cases around the world in 2018 [10].

The high incidence of H. pylori infection is not always associated with high prevalence of GC. This enigma of H. pylori infection and GC, defined by a very high incidence of infection but a low rate of GC, was first described by Holcombe in 1992 as the "African Enigma" [11]. Hence, the African enigma represents a modification of the inflammatory response triggered by the infection, leading to the absence of any neoplastic manifestations [11]. Other countries including China, Colombia, India, Costa Rica, and Malaysia have described similar enigmas [11]. Several previous studies have suggested that an increased risk of GC is associated with lifestyle behaviors, such as cigarette smoking, intensive alcohol consumption, high salt intake, consumption of processed meat, and low intake of fruits [12]. In addition, host’s genetics has been associated with GC. Mutation in CDH1 gene that encodes E-cadherin protein for cell–cell adhesion has been associated with more than 80% increased risk of GC, and patients with reduced expression of the E-cadherin protein have a poor prognosis [13].

The majority of infections are asymptomatic, therefore a screening and treatment program cannot be justified except for high-risk patients [14]. However, the inflammatory response to an infection in a host and the virulence of the infection vary between individuals. Additionally, environmental exposures may also contribute to the increase in the risk of GCs [15]. Infection prevalence shows large geographical variations. In general, the prevalence of infection is higher in developing countries than developed countries such as Europe and North America [16]. Despite the global prevalence of GC in people with H. pylori infection was reported by Pormohammad et al. [1], a complete up-to-date research on the prevalence of GC in people with H. pylori infection has not been done yet. In the previous study, only studies conducted until 2016 were evaluated. However, in this review, statistics until 2021 were considered. Also, there were several differences between 2 studies in terms of the data bases, time period of search, eligibility criteria, and keywords. Hence, this study aimed to update the GC estimate in H. pylori positive patients after reviewing existing evidence and reassessing the global burden of GC caused by H. pylori in different regions.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase were searched from1 January 2011 to 20 April 2021 to retrieve all relevant studies in the world. MeSH keywords and search strategy were as below: 'Stomach Neoplasm' [tiab], OR 'Cancer of Stomach' [tiab], OR 'Gastric Cancer' [tiab], OR 'Cancer of Gastric' [tiab], OR '' Stomach Cancer '[tiab], OR 'Neoplasm of Stomach' [tiab] AND 'Helicobacter pylori' [tiab], OR 'Campylobacter pylori' [tiab], OR 'Campylobacter pylori subsp. pylori' [tiab] OR, 'Campylobacter pyloridis' [tiab], OR 'Helicobacter nemestrinae' [tiab] AND 'Prevalence' [tiab], OR 'Frequency' [tiab].

Eligibility criteria

We set our inclusion and exclusion criteria based on PECOTS criteria (population, exposure, comparison, outcome, time and study design) (Table 1). For that, all cross-sectional, prospective and retrospective case-series studies which reported the prevalence of GC in H. pylori patients were included. However, case reports and case series with less than five patients (as study population) and also clinical trial studies were excluded. Also, studies without reported prevalence data, definite sample sizes, and clear correct estimates of the prevalence, as well as case–control studies and abstracts presented in scientific meetings with no sufficient data were excluded from this study.

Table 1.

PECOTS criteria of the study

| Selection criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients that have gastric cancer that diagnosed using invasive or non-invasive criteria, including endoscopy, pathology, histology, fiberscopy. PET/CT imaging, immunohistochemistry staining, biopsy and other methods | - |

| Exposure | Patients that have H.pylori that diagnosed using UT, PCR, ELISA, salt tolerance, Gram's stain, cagA gene pcr and other methods | - |

| Comparison | ---- | --- |

| Outcome | Prevalence of cancer in positive H.pylori patients | --- |

| Time | Published form 2011 to 20 April 2021 | --- |

| Study design | Observational studies including prospective or retrospective case series, cohort and cross sectional studies | Case control, ecological studies, in vivo studies, experimental of interventional studies, case report, lack of access to full text articles, review articles, letter to editor |

Study selection

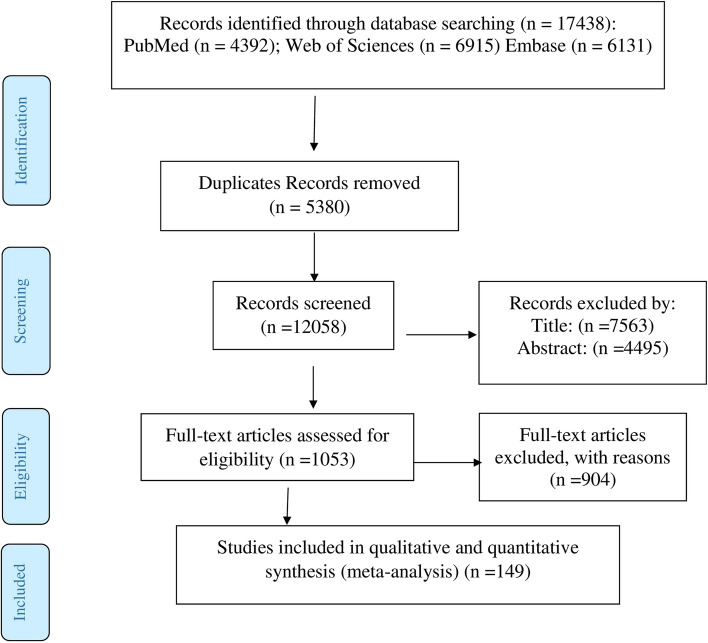

There were 17,438 results from the initial search. Two authors (SK and RP) separately assessed these papers' eligibility, and any discrepancies were settled by consensus. The following step involved excluding 5380 duplicate articles. Also, after reviewing the titles and abstracts of the remaining publications, 11,058 papers were omitted. Of the remaining 1053 articles, 904 ineligible articles were omitted during the review of the entire texts. Eventually, 149 articles that qualified for inclusion were examined.

Quality assessment

Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to measure the quality of studies (Table 2). This scale is used to measure the quality of observational studies including cohort, cross-sectional and case series studies. The validity and reliability of this tool have been proven in various studies [17, 18].

Table 2.

Quality assessment of studies by Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist

| Author | Study design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the sample | Sample size | Non-respondents | Ascertainment of the exposure (risk factor) | Assessment of outcome | Statistical test | |||

| Dabiri et al. [19] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Taghvaei et al. [20] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Wang et al. [21] | CS | * | * | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Yakoob et al. [22] | CS | * | * | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Yang et al. [23] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Gucin et al. [24] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Shrestha et al. [25] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Ouyang et al. [26] | CS | * | * | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Kim et al. [27] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Shukla et al. [28] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Cherati et al. [29] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Raei et al. [30] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Abdi et al. [31] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Goudarzi et al. [32] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Al-Sabary et al. [33] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Ranjbar et al. [34] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Yadegar et al. [35] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Kupcinskas et al. [36] | CS | * | * | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Oh et al. [37] | CS | - | - | * | * | NA | * | * |

| Wang et al. [38] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Sakitani et al. [39] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Pakbaz et al. [40] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Sedarat et al. [41] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Shadman et al. [42] | CS | * | * | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Shin et al. [43] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Archampong et al. [44] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Xie et al. [45] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Deng et al. [46] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Shi et al. [47] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Yu et al. [48] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Szkaradkiewicz et al. [49] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Taghizadeh et al. [50] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Vilar e Silva et al. [51] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Gantuya et al. [52] | CS | * | * | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Shukla et al. [53] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Hu et al. [54] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Tahara et al. [55] | CS | - | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Ono et al. [56] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | * | * |

| Pandey et al. [57] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Huang et al. [58] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Xie et al. [59] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Nam et al. [60] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Saber et al. [61] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Matsunari et al. [62] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Khatoon et al. [63] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Amiri et al. [64] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Farajzadeh Sheikh et al. [65] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| El Khadir et al. [66] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Park et al. [67] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Yoon et al. [68] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | * | * |

| Guo et al. [69] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Haddadi et al. [70] | CS | * | - | * | * | NA | ** | * |

| Khan et al. [71] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Santos et al. [72] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| GholizadeTobnagh et al. [73] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Toyoda et al. [74] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Thirunavukkarasu et al. [75] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Bakhti et al. [76] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Vannarath et al. [77] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Wei et al. [78] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Abu-Taleb et al. [79] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Chomvarin et al. [80] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Bilgiç et al. [81] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Abadi et al. [82] | CS | - | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Abadi et al. [83] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Ohkusa et al. [84] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Herrera et al. [85] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | * | * |

| Tanaka et al. [86] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Choi et al. [87] | CS | * | - | * | ** | NA | ** | * |

| Masoumi Asl et al. [88] | HBS | |||||||

| Vinagre et al. [89] | HBS | |||||||

| Khatoon et al. [90] | HBS | |||||||

NA Not applicable, CS cross sectional

As mentioned in the methods section, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) consists of three domains. The first domain is Selection, which includes four items: Representativeness of the sample, Sample size, Non-respondents, Ascertainment of the exposure. If the first three items are established, one star is assigned. If the fourth item is also established, one or two stars are assigned. If none of the items are established, no star is assigned. The second domain is Comparability, which has one item: Comparability of the groups. If this item is established, one star is assigned. If it is not established, no star is assigned. The third domain is Outcome, which includes two items: Assessment of the outcome, Statistical test. If the first item is established, one or two stars are assigned. If the second item is also established, one star is assigned

Data extraction

Two authors independently performed the study selection and validity assessment and resolved any disagreements by consulting a third researcher. First author, country, enrollment time, published time, type of study, number of Hp+ patients, mean age in Hp+ patients, detection method of Hp, number of patients with cancer, sort (name) of cancer, diagnosis method of GC, and prevalence (95% CI) were extracted from articles.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests in this study were performed with Stata 14.0. As previous researches [91, 92] the sample size, the number of patients with H. pylori, number of cancer cases in patient with H. pylori, and prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients were extracted. We applied Cochran's Q test to determine the heterogeneity. We also quantified it with the I2 index. Based on the Higgins classification approach, I2 values above 0.7 were determined as high heterogeneity. We used random effects model to estimate pooled values where that heterogeneity was high. Also we used the subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis to find out the heterogeneity sources. Metaprop package were used to calculate the pooled prevalence with 95% confidence interval. Random-effects model was applied to estimate the pooled prevalence. This package applies double arcsine transformations to stabilize the variance in the meta-analyses. The effects of publication time, continents, age mean, sample size and study design on the studies heterogeneity were analyzed by univariate and multiple meta-regression analysis. Publication bias evaluated by “metabias” command. In case of any publication bias, we adjusted the prevalence rate with “metatrim” command applying trim-and-fill approach. Statistical significance was considered 0.05.

Result

A total of 149 studies with 352,872 total sample size were included in our study. Selection process flow chart is available in Fig. 1, and Table 3 shows the studies’ characteristics such as first author, country, published time and type of study. Several primary studies reported overall number of gastric cancer and do not present more detail about cancer. But some primary studies presented more detail about cancer such as anatomical location of it. Many studies mentioned they used histopathology method to detection of cancer. The highest studies number belonged to Asia continent (114 studies) area and Africa continent (6 studies) was the lowest one. All the included studies were published during 1 January 2011 to 20 April 2021. The minimum and maximum age range of the subjects was for Haddadi et al. [93] article with the age ranges (mean age = 26 years old) and Shibukawa et al. [94] study with the mean age = 73 years old, respectively. Sixty-nine (46.31%) of studies were cross sectional, sixty-four (42.95%) of studies were case series and sixteen (10.73%) of studies were cohort.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| First author | Country | Enrollment time | Published time | Type of study | Number of Hp + patients | Mean age in Hp + patients | Detection method of Hp | Number of patients with cancer | Sort (name) of cancer | Diagnosis method of GC | Prevalence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masoumi Asl et al. [95] | Iran | March- September 2019 | 2020 | HBS | 74 | 53.45 | UT, Histology, PCR | 24 | GC | Endoscopy, Histopathology | 32.43 (22 to 44.32) |

| Khan et al. [96] | Pakistan | 2005–2008 | 2013 | CS | 201 | 38 | PCR | 5 | GC | Clinical diagnosis, endoscopic, histology | 2.49 (0.81 to 5.71) |

| Santos et al. [97] | Brazil | - | 2012 | CS | 176 | 59.2 | RUT, histology, PCR | 64 | GC | Histopathological | 36.36 (29.26 to 43.94) |

| GholizadeTobnagh et al. [98] | Iran | 2007–2014 | 2017 | CS | 211 | 26.56 | Culture, PCR, UT | 38 | Cardia cancer:14/38, non cardia cancer 23/38, cardia and non cardia GC:1/38; and intestinal type: 20/38 and diffuse type: 18/38 | Histopathological | 18.01 (13.07 to 23.87) |

| Toyoda et al. [88] | Japan | 2004–2007 | 2012 | CS | 923 | 59.7 | ELISA | 8 | Adenocarcinoma | Histopathological | 0.87 (0.37 to 1.7) |

| Thirunavukkarasu et al. [71] | India | 2011 | 2017 | CS | 62 | 39.68 | Culture, UT, salt tolerance | 19 | GC | - | 30.65 (19.56 to 43.65) |

| Cremniter et al. [72] | France | 2011–2014 | 2018 | Prospective cohort | 183 | 56 | Culture, real-time PCR | 2 | 47:precancerous, 23:cancerous lesions, 3:atrophies, 19: metaplasias, 3:dysplasias, 2: gastric adenocarcinomas | Histopathological | 1.09 (0.13 to 3.89) |

| Eun Bae et al. [73] | Korea | 2005–2016 | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 19,754 | 48 | Serologic test | 106 | GC | Endoscopy | 0.54 (0.44 to 0.65) |

| Bakhti et al. [74] | Iran | 2019–2020 | 2020 | CS | 290 | 46.52 | UT, Gram's stain, positive catalase, urease and oxidase tests, culture, histology, PCR | 89 | 89: GC, 38cardia GC, 47:non-cardia GC, 4: both the types of cardia GC and non-cardia GC. 57: intestinal- type adenocarcinoma, 25: diffuse-type adenocarcinomas, 7: other pathologic types of cancer | Endoscopic and histopathologic tests | 30.69 (25.43 to 36.35) |

| Vannarath et al. [75] | Laos | 2010–2012 | 2014 | CS | 119 | 46 | RUT, PCR | 3 | GC | Histological | 2.52 (0.52 to 7.19) |

| Wei et al. [99] | China | 2007–2008 | 2012 | CS | 197 | 49.67 | Histology, PCR | 53 | GC | Pathological | 26.9 (20.85 to 33.67) |

| Dabiri et al. [100] | Iran | February—June 2014 | 2017 | CS | 160 | 45.5 | Culture, PCR | 15 | GC | - | 9.38 (5.34 to 14.99) |

| Taghvaei et al. [76] | Iran | 2007–2010 | 2011 | CS | 140 | 41.5 | PCR, RUT | 32 | GC | Endoscopic and pathologic | 22.86 (16.19 to 30.71) |

| Raza et al. [77] | Pakistan | 2020 | PCS | 147 | - | PCR | 34 | GC | HE, modified Giemsa stain | 23.13 (16.58 to 30.79) | |

| Wang et al. [78] | China | May- September 2010 | 2014 | CS | 80 | - | RUT, Geimsa staining | 10 | GC | IHC | 12.5 (6.16 to 21.79) |

| Dadashzadeh et al. [19] | Iran | 2016 | 2017 | PCS | 109 | 39 | Culture, PCR | 9 | GC | - | 8.26 (3.85 to 15.1) |

| Yakoob et al. [20] | Pakistan | 2013–2014 | 2016 | CS | 309 | 45 | RUT, histology, PCR Culture | 54 | GC | Histopathology | 17.48 (13.41 to 22.18) |

| Sonnenberg et al. [101] | USA | 2008–2011 | 2013 | PCS | 16,759 | 59.2 | IHC | 172 | Adenocarcinoma | Colonoscopy and EGD histopathological analysis: | 1.03 (0.88 to 1.19) |

| Yang et al. [21] | China | 2015–2017 | 2018 | CS | 59 | 58.9 | UBT, IHC | 9 | GC | Biopsy | 15.25 (7.22 to 26.99) |

| Vinagre et al. [102] | Brazil | 2013–2014 | 2015 | HBS | 506 | PCR | 145 | GC |

Histopathological analysis: HE staining |

28.66 (24.75 to 32.81) | |

| Li et al. [22] | China | - | 2020 | PCS | 160 | 53.2 | RUT, IHC | 75 | Adenocarcinoma | Histopathological | 46.88 (38.95 to 54.92) |

| Gucin et al. [103] | Turkey | 2007–2011 | 2013 | CS | 66 | - | RUT, PCR | 35 | GC | IHC analysis, apoptosis assays, TUNEL assay Histopathology | 53.03 (40.34 to 65.44) |

| Pandey et al. [23] | India | - | 2014 | PCS | 543 | RUT, Histology | 10 | GC | - | 1.84 (0.89 to 3.36) | |

| Shrestha et al. [89] | Nepal | 2011- 2013 | 2014 | CS | 155 | 44.7 | HE, Geimsa staining | 3 | GC | Endoscopy | 1.94 (0.4 to 5.55) |

| Sheikhani et al. [104] | Iraq | 2007–2008 | 2010 | PCS | 54 | 43.22 | HE staining, Modified Giemsa stain, ELISA | 6 | GC | Histopathology | 11.11 (4.19 to 22.63) |

| Ouyang et al. [24] | China | 2007–2012 | 2021 | CS | 79 | - | RUT, Giemsa staining | 22 | GC | Pathology findings | 27.85 (18.35 to 39.07) |

| Leylabadlo et al. [105] | Iran | - | 2016 | PCS | 88 | - | Culture, PCR | 26 | GC | Endoscopic and pathology | 29.55 (20.29 to 40.22) |

| Alaoui Boukhris et al. [25] | Morocco | 2009—2013 | 2013 | PCS | 478 | - | PCR | 25 | Signet ring cell carcinoma (20/48), adenocarcinoma (18/48), MALT lymphoma (10/48) | Histopathology | 5.23 (3.41 to 7.62) |

| Khamis et al. [106] | Iraq | - | 2018 | PCS | 194 | 48 | RUT, culture, histology examination, PCR | 77 | GC | Endoscopy | 39.69 (32.75 to 46.95) |

| Gunaletchumy et al. [26] | Malaysia | - | 2014 | PCS | 27 | - | - | 4 | GC | Endoscopic and histological examinations | 14.81 (4.19 to 33.73) |

| Doorakkers et al. [107] | Sweden | 2005 -2012 | 2018 | Cohort | 95,176 | 60.1 | - | 75 |

Gastric adenocarcinoma: 75 Non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma: 69 Cardia adenocarcinoma: 6 |

- | 0.08 (0.06 to 0.1) |

| Horie et al. [108] | Japan | 2005–2018 | 2020 | Retrospective | 1300 | 58.3 | - | 37 | GC | - | 2.85 (2.01 to 3.9) |

| Kim et al. [109] | Korea | February 2006 and July 2015 | 2020 | CS | 137 | 54.9 | Giemsa staining, CLO test, culturing, serology | 69 | GC | - | 50.36 (41.7 to 59.01) |

| Shukla et al. [110] | India | 2007& 2010 | 2012 | CS | 105 | 46.34 | RUT, culture, histopathology, PCR | 24 | GC | Clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological examination | 22.86 (15.23 to 32.07) |

| Cherati et al. [111] | Iran | Mar 2015 and September 2015 | 2017 | CS | 67 | 52.2 | PCR | 28 | GC | Histologically | 41.79 (29.85 to 54.48) |

| El Khadir et al. [112] | Morocco | - | 2018 | 827 | PCR | 81 | GC | Histopathological examination | 9.79 (7.85 to 12.03) | ||

| Raei et al. [27] | Iran | 2007 to 2014 | 2015 | CS | 242 | Culture, PCR | 42 |

Cardia cancer:18/42 Non-cardia cancer:24/42 Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma:24/42 Diffuse-type adenocarcinoma:16/42 Invasive squamous cell-type carcinoma:1/42 Mucin producing-type adenocarcinoma:1/42 |

Histopathological examination | 17.36 (12.8 to 22.73) | |

| Abdi et al. [28] | Iran | 2012–2014 | 2016 | CS | 83 | 48.7 | PCR | 27 | GC | Histopathological | 32.53 (22.65 to 43.7) |

| Ansari et al. [29] | Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal and Bangladesh | 2010–2014 | 2017 | PCS | 374 | 37.9 | PCR, histological | 5 | GC | Endoscopic examination/ histopathological method | 1.34 (0.44 to 3.09) |

| Ortiz et al. [113] | USA | 2013 | 2019 | PCS | 116 | 52 | Culture, PCR | 23 | Adenocarcinoma Diffuse:10Intestinal:12 Mixed:1 | Histopathologic diagnoses | 19.83 (13 to 28.25) |

| Mohammadi et al. [30] | Iran | - | 2019 | PCS | 120 | 52 | PCR | 11 | GC | Endoscopy | 9.17 (4.67 to 15.81) |

| Yeh et al. [31] | Taiwan | - | 2019 | PCS | 164 | 59.2 | H&E, modified Giemsa stains, PCR, ELISA | 30 | GC | Histological | 18.29 (12.7 to 25.07) |

| Sheu et al. [114] | Taiwan | - | 2012 | PCS | 92 | Histology, cultures | 20 | GC | Endoscopy with histological confirmation | 21.74 (13.81 to 31.56) | |

| Yeh et al. [115] | Taiwan | 2009–2010 | 2011 | Prospective | 145 | 49.3 | Histology and cultures | 22 | GC | Endoscopy | 15.17 (9.76 to 22.07) |

| Goudarzi et al. [116] | Iran | 2012- 2013 | 2015 | CS | 98 | 49 | Culture, RUT | 35 | GC | - | 35.71 (26.29 to 46.03) |

| Phan et al. [117] | Vietnam | 2012–2014 | 2017 | PCS | 96 | 44.1 | Culture, PCR | 2 | GC | Histology | 2.08 (0.25 to 7.32) |

| Al-Sabary et al. [118] | Iraq | Feb to Sep 2016 | 2017 | CS | 92 | - | Culture, PCR | 3 | GC | Endoscopy | 3.26 (0.68 to 9.23) |

| Ranjbar et al. [119] | Iran | 2016-2017 | 2018 | CS | 526 | - | Cultured, histology | 4 | Gastric:4 | Endoscopy | 0.76 (0.21 to 1.94) |

| Hernandez et al. [32] | Mexico | - | 2018 | PCS | 307 | - | ELISA | 87 | GC | Histology | 28.34 (23.37 to 33.74) |

| Blanchard et al. [120] | Multi-country * | - | 2013 | PCS | 65 | - | - | 4 | GC | - | 6.15 (1.7 to 15.01) |

| Zeng et al. [33] | China | 1994 and 2002 | 2011 | Cohort | 967 | - | ELISA, Serology | 160 | GC 109: intestinal, 104: diffuse, and 35: mixed type | Histopathologic diagnosis | 16.55 (14.26 to 19.04) |

| Boonyanugomol et al. [34] | Thailand and Korea | - | 2020 | PCS | 170 | - | RUT-Culture -PCR | 40 | GC | Endoscopy | 23.53 (17.37 to 30.63) |

| Ogawa et al. [121] | Japan | - | 2017 | PCS | 43 | - | Culture | 10 | GC | Endoscopy | 23.26 (11.76 to 38.63) |

| Boonyanugomol et al. [122] | Thailand | - | 2019 | PCS | 80 | - | RUT, PCR | 10 | GC | Endoscopy | 12.5 (6.16 to 21.79) |

| Ghoshal et al. [123] | India | - | 2014 | PCS | 68 | 54.3 | RUT, histology, ELISA | 21 | GC | Histology, Endoscopy, Surgery | 30.88 (20.24 to 43.26) |

| Farzi et al. [124] | Iran | - | 2018 | PCS | 68 | 47 | Culture, PCR | 5 | GC | Endoscopic and pathological findings | 7.35 (2.43 to 16.33) |

| Yadegar et al. [125] | Iran | 2011–2012 | 2019 | CS | 61 | 36 | Culture, PCR | 5 | GC | Histopathological examination | 8.2 (2.72 to 18.1) |

| Hashemi et al. [126] | Iran | 2015–2016 | 2019 | 157 | - | PCR, Culture, UT | 22 | GC | endoscopy | 14.01 (8.99 to 20.44) | |

| Kupcinskas et al. [127] | Germany | 2005–2012 | 2014 | CS | 477 | - | Serology | 191 | GC Intestinal:136, Diffuse:89 Mixed:33, Data unavailable:105 |

Histological subtyping of GC: Laurén classification into intestinal and diffuse-types |

40.04 (35.61 to 44.59) |

| Shibukawa et al. [94] | Japan | 2006–2019 | 2021 | Retrospective | 1003 | 74 | Serological testing, RUT, IHC, SAT | 168 | GC | Endoscopic characteristics | 16.75 (14.49 to 19.21) |

| Oh et al. [128] | Korea | 2008–2013 | 2019 | CS | 187 | - | Warthin-Starry silver impregnation method | 35 | GC | - | 18.72 (13.4 to 25.06) |

| Wang et al. [35] | China | 2015–2018 | 2020 | CS | 61 | 55.9 | Giemsa staining method | 32 | Non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma | Histologically | 52.46 (39.27 to 65.4) |

| Boreiri et al. [129] | Iran | 2000–2001 | 2013 | Cohort | 892 | 53.1 | RUT | 32 | GC | Histological | 3.59 (2.47 to 5.03) |

| Sakitani et al. [36] | Japan | January 1996 and March 2013 | 2015 | CS | 965 | 62.9 | RUT, serological testing, UBT, pathological analysis | 21 | GC Intestinal type:16 Diffuse type:5 | Pathology | 2.18 (1.35 to 3.31) |

| Sekikawa et al. [37] | Japan | January 2004 and December 2012 | 2016 | Cohort | 236 | - | - | 14 | GC | Histology, Endoscopy | Sekikawa et al. (201–-5.93 (3.28 to 9.75) |

| Pakbaz et al. [38] | Iran | March to August 2011 | 2013 | CS | 82 | 46 | RUT, PCR | 13 | GC | Endoscopy | 15.85 (8.72 to 25.58) |

| Sedarat et al. [130] | Iran | 2013- 2015 | 2018 | CS | 150 | 43 | RUT, PCR | 4 | GC | Histology, Endoscopy | 2.67 (0.73 to 6.69) |

| Shadman et al. [39] | Iran | 2011 -2012 | 2015 | CS | 133 | 63.2 | Histopathological examination, RUT | 47 |

GC Well, differentiated:3 Moderately differentiated:10 Poorly differentiated:15 Undifferentiated:4 |

Histopathological | 35.34 (27.25 to 44.09) |

| Shin et al. [131] | korea | 2006–2014 | 2016 | CS | 132 | 60.3 | Histology, CLO test, culture | 26 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 19.7 (13.29 to 27.51) |

| Archampong et al. [40] | Ghana | 2010& 2012 | 2016 | CS | 198 | - | RUT-CLO | 19 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 9.6 (5.88 to 14.58) |

| Kobayashi et al. [41] | Japan | April 2005 & November 2015 | 2016 | Retrospective | 37 | - | RUT, SAT | 7 | Early gastric cancer:4 Gastric adenoma:2 MALT lymphoma:1 Other fiberscopic findings: 3 | Fiberscopy. PET/CT imaging | 18.92 (7.96 to 35.16) |

| Xie et al. [42] | China | 2007–2008 | 2014 | CS | 142 | 58.3 | RUT, modified Giemsa staining | 61 | GC Male:39, Female: 22 | Pathological diagnosis | 42.96 (34.69 to 51.53) |

| Deng et al. [43] | China | 2008& 2013 | 2014 | CS | 76 | - | 7 | Among the 176 GC cases, 63: intestinal type, 96:diffuse type, 17: mixed type | Pathological diagnosis | 9.21 (3.78 to 18.06) | |

| Shi et al. [44] | China | 2010—2012 | 2014 | CS | 40 | - | RUT,Warthin-Starry staining. Gram staining. Oxidase and catalase tests | 13 | GC: 2 tissues at an early stage and 11 tissues at an advanced stage; 6 intestinal type tissues, 4 diffuse type tissues, and 3 mixed type tissues | Pathological diagnosis | 32.5 (18.57 to 49.13) |

| Yu et al. [132] | China | 1992 -2007 | 2014 | CS | 217 | 59.15 | IHC -PCR | 116 | intestinal type:97, diffuse type: 95 | Histopathology | 53.46 (46.58 to 60.24) |

| Zabaglia et al. [45] | Brazil | - | 2017 | PCS | 72 | 65,6 | PCR | 19 | GC | Histopathology | 26.39 (16.7 to 38.1) |

| Szkaradkiewicz et al. [46] | Poland | 2013–2014 | 2016 | CS | 42 | 65 | PCR | 15 | GC | Histopathology | 35.71 (21.55 to 51.97) |

| Jorge et al. [47] | Brazil | - | 2013 | PCS | 27 | 63.4 | Multiplex PCR | 11 |

Intestinal: 12 Diffuse type: 8 |

Histopathology | 40.74 (22.39 to 61.2) |

| Taghizadeh et al. [48] | Iran | 2012 -2013 | 2014 | CS | 84 | - | Histopathology, RUT | 21 | GC | Endoscopic, Histopathology | 25 (16.19 to 35.64) |

| Khatoon et al. [133] | India | 2012–2016 | 2018 | HBS | 122 | 47.34 | RIT, culture, histopathology, PCR | 40 |

Intestinal:38 Diffuse: 32 |

clinical, endoscopic and histopathological findings |

32.79 (24.56 to 41.87) |

| Yan et al. [49] | China | 2019–2020 | 2021 | PCS | 294 | 62.4 | UBT, RUT, histopathology | 132 | GC | Endoscopy | 44.9 (39.12 to 50.78) |

| Vilar e Silva et al. [134] | Brazil | 2010- 2011 | 2014 | CS | 384 | 59.9 | PCR | 190 | 61/190: diffuse type 129/190: intestinal type | Histological | 49.48 (44.37 to 54.6) |

| Anwar et al. [50] | Egypt | 2008–2009 | 2012 | PCS | 40 | 46.9 | Serological, ELISA | 20 |

GC Intestinal:10 Diffuse: 7 Mixed: 3 |

History and clinical examination, Endoscopy and histopathology |

50 (33.8 to 66.2) |

| Gantuya et al. [90] | Mongolia | 2014–2016 | 2019 | CS | 606 | 53.8 | RUT, culture, Histology, IHC, serology, updated Sydney system | 27 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 4.46 (2.96 to 6.42) |

| Beheshtirouy et al. [135] | Iran | 2016–2018 | 2020 | RCS | 62 | - | PCR | 35 | GC | - | 56.45 (43.26 to 69.01) |

| Park et al. [51] | Korea | 2015 | 2019 | PCS | 58 | 54.1 | RUT, Serology, EIA, latex agglutination turbidimetric immunoassay, | 32 | GC | Histopathology | 55.17 (41.54 to 68.26) |

| Shukla et al. [136] | India | 2005–2009 | 2011 | CS | 118 | - | RUT, Culture, histopathology, PCR | 31 | GC | Histopathology | 26.27 (18.6 to 35.17) |

| Toyoshima et al. [52] | Japan | 2002–2014 | 2017 | RCS | 1232 | 54.1 | UBT, Serology, SAT | 15 | GC | Histological evaluation: Vienna classification | 1.22 (0.68 to 2) |

| Spulber et al. [137] | Romania | 2012–2013 | 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 1694 | 55 | Fast urease test | 46 | GC | Endoscopy | 2.72 (1.99 to 3.61) |

| Sugimoto et al. [138] | Japan | 2013–2015 | 2017 | RCS | 1200 | 71.3 | Anti-Hp- IgG serological test a PCR, culture UBT | 268 | De novo cancers: 248 metachronous cancers: 20 | Endoscopy | 22.33 (20.01 to 24.8) |

| Kobayashi et al. [53] | Japan | 2013 -2017 | 2019 | RCS | 1271 | 61 | Serum anti-H. pylori antibodies, UBT, SAT, histopathology | 84 | MALT:16 | Histopathology | 6.61 (5.31 to 8.12) |

| Leung et al. [139] | China | 2003–2012 | 2018 | Cohort | 73,237 | 55.2 | Endoscopy | 200 | GC | - | 0.27 (0.24 to 0.31) |

| Watari et al. [140] | Japan | - | 2019 | Cohort | 61 | 70 | UBT, Giemsa staining, IgG antibody test | 37 | GC | Histological analysis | 60.66 (47.31 to 72.93) |

| Nam et al. [141] | Korea | 2003–2011 | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | 5558 | 52.6 | RUT | 46 |

Early GC: 29 AGCs gastric cardia: 2 |

Endoscopic resection | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.1) |

| Sallas et al. [142] | Brazil | - | 2019 | PCS | 72 | 65.6 | PCR | 19 | GC | Histological classification: Sydney system | 26.39 (16.7 to 38.1) |

| Queiroz et al. [143] | Brazil | - | 2011 | PCS | 252 | 61.9 | Histopathological study, PCR | 58 | Non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma | Histopathology | 23.02 (17.97 to 28.71) |

| Sun et al. [144] | China | - | 2018 | PCS | 49 | - | UBT | 25 | GC | Pathology: gastric resection | 51.02 (36.34 to 65.58) |

| Jiang et al. [145] | China | 2003–2012 | 2016 | RCS | 43,080 | - | RUT | 1497 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 3.47 (3.3 to 3.65) |

| Hu et al. [146] | China | 2015–2016 | 2019 | CS | 57 | - | RUT, IHC | 16 | GC | - | 28.07 (16.97 to 41.54) |

| Ferraz et al. [147] | Brazil | - | 2015 | PCS | 94 | 40.3 | PCR | 44 |

Neoplastic:21, adjacent nonneoplastic tissue:23 |

Histopathology | 46.81 (36.44 to 57.39) |

| Tahara et al. [148] | Japan | 2013–2016 | 2019 | CS | 87 | - | Histological analysis and molecular study | 43 |

Metachronous:8 GC:35 |

Histological analysis and molecular study | 49.43 (38.53 to 60.36) |

| Vaziri et al. [149] | Iran | - | 2013 | PCS | 71 | 66 | Culture, PCR | 1 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 1.41 (0.04 to 7.6) |

| Boonyanugomol et al. [54] | Thailand and Korea | - | 2018 | PCS | 95 | - | RUT, PCR | 10 | GC | - | 10.53 (5.16 to 18.51) |

| Ono et al. [150] | Dominican | 2011–2016 | 2020 | CS | 175 | - | Culture, PCR | 1 | GC | Histopathology | 0.57 (0.01 to 3.14) |

| Pandey et al. [55] | India | 2007–2012 | 2018 | CS | 99 | - | PCR, Culture | 34 | Diffuse‐type:44, Intestinal‐type:21 | IHC | 34.34 (25.09 to 44.56) |

| Link et al. [151] | Germany | 2011–2013 | 2015 | PCS | 41 | 68.6 | Culture rapid urease test, serology, histology and microbiology | 8 |

Cardia:7,Corpus:6 Antrum:3,Diffuse:5 Intestinal:9,other 2 |

Histopathology | 19.51 (8.82 to 34.87) |

| Casarotto et al. [152] | Italy | - | 2019 | PCS | 91 | - |

Histological Study Gram staining, and urease production |

39 | GC | Histopathology | 42.86 (32.53 to 53.66) |

| Zao et al. [56] | China | - | 2020 | PCS | 177 | - | Culture, PCR | 33 | GC | - | 18.64 (13.19 to 25.17) |

| Abu-Taleb et al. [57] | Egypt | 2016–2017 | 2018 | CS | 90 | - | RUT, PCR | 4 | GC | Endoscopy | 4.44 (1.22 to 10.99) |

| Chomvarin et al. [153] | Thailand | 2012 | CS | 147 | 50 | Gram’s staining, catalase, oxidase and UT, PCR | 18 | GC | - | 12.24 (7.42 to 18.66) | |

| Bilgiç et al. [154] | Turkish | 2014–2015 | 2018 | CS | 95 | 55.71 | RT-PCR | 34 | GC |

Histopathology epigenetic assessments |

35.79 (26.21 to 46.28) |

| Chiu et al. [155] | Taiwan | 2018 | Cohort | 60 | - | Gastric endoscopy | 18 | Adenocarcinoma | Endoscopy | 30 (18.85 to 43.21) | |

| Kumar et al. [79] | USA | 1994–2018 | 2020 | Cohort | 36,695 | 60.4 | Pathology, SAT, UBT | 108 | Oesophageal and proximal GCs | Endoscopy | 0.29 (0.24 to 0.36) |

| Nishikawa et al. [80] | Japan | 2006–2014 | 2018 | Cohort | 674 | UBT, RUT, EIA | 25 | Gastric cancer | Endoscopy | 3.71 (2.41 to 5.43) | |

| Sadjadi et al. [81] | Iran | - | 2014 | Cohort | 928 | 53.1 | Histology, RUT | 36 | GC | Histological | 3.88 (2.73 to 5.33) |

| Abadi et al. [156] | Iran | 2009–2010 | 2011 | CS | 128 | - | Culture, PCR | 28 | Adenocarcinoma | Endoscopy | 21.88 (15.05 to 30.04) |

| Hnatyszyn et al. [157] | Poland | - | 2013 | PCS | 131 | 36 |

RUT, IgG antibodies, histopathological examination |

17 | GC | Endoscopy and histopathology | 12.98 (7.74 to 19.96) |

| Abadi et al. [158] | Iran | 2007–2010 | 2012 | CS | 232 | 44 |

Gram staining, Acid resistance testing, Endoscopy, PCR |

32 | GC | Histopathology | 13.79 (9.63 to 18.91) |

| Ohkusa et al. [159] | Japan | 1994–2000 | 2004 | CS | 172 | 53 | Endoscopy, RUT, UBT, histological examination | 5 | GC gastric adenoma or early cancer | Endoscopy | 2.91 (0.95 to 6.65) |

| Abe et al. [82] | Japan | - | 2010 | PCS | 254 | 56.8 | Culture, IHC | 28 | GC | Endoscopy | 11.02 (7.45 to 15.54) |

| Lahner et al. [160] | Italy | - | 2011 | PCS | 29 | 52.5 | Biopsy, immunoproteome technology | 10 | GC | - | 34.48 (17.94 to 54.33) |

| Herrera et al. [83] | Mexico | 1999–2002 | 2013 | CS | 137 | 55.3 | ELISA | 41 | Gastric adenocarcinoma | Endoscopic and Histopathology | 29.93 (22.41 to 38.34) |

| Tanaka et al. [161] | Japan | 2003–2007 | 2011 | CS | 99 | 59.1 | Biopsy immunoproteome technology | 90 | Gastric carcinoma | IHC | 90.91 (83.44 to 95.76) |

| Batista et al. [84] | Brazil | - | 2011 | Cohort | 436 | 52.7 | 188 | GC | Endoscopy pepsinogen tests | 43.12 (38.42 to 47.92) | |

| Choi et al. [162] | South Korea | 2006–2013 | 2015 | CS | 237 | - | Modified Giemsa staining, culture, RUT, PCR | 71 | GC | Biopsy, serum pepsinogen tests | 29.96 (24.2 to 36.23) |

| Chuang et al. [163] | Taiwan | - | 2011 | PCS | 469 | 48.1 | Modified Giemsa stain, SDS-PAGE | 26 | GC | Gastric biopsy | 5.54 (3.65 to 8.02) |

| Cavalcante et al. [85] | Brazil | 2008 | 2012 | PCS | 134 | 46 | PCR | 30 | Gastric carcinoma | Histopathology | 22.39 (15.64 to 30.39) |

| Borges et al. [164] | Brazil | - | 2019 | PCS | 75 | 40.9 | PCR | 2 | Gastric adenocarcinoma | Histopathology | 2.67 (0.32 to 9.3) |

| Salih et al. [87] | Turkey | - | 2013 | PCS | 66 | - | Giemsa, PCR, RUT | 35 | 34 intestinal type, 1 diffuse type | Histopathology | 53.03 (40.34 to 65.44) |

| Huang et al. [165] | China | 2012–2014 | 2018 | CS | 122 | - | UBT, RUT, histopathology | 65 | GC | Gastroscopy/histopathology | 53.28 (44.03 to 62.36) |

| Xie et al. [166] | China | 2010–2016 | 2018 | CS | 116 | - | ELISA | 72 | 19 early, 53 advanced GC | Gastroscopy/pathological | 62.07 (52.59 to 70.91) |

| Pereira et al. [167] | Brazil | - | 2020 | PCS | 103 | - | PCR | 38 | GC | Histopathological | 36.89 (27.59 to 46.97) |

| Nam et al. [168] | Korea | 2003–2013 | 2018 | CS | 17,751 | - | RUT | 82 | GC | Gastroscopy | 0.46 (0.37 to 0.57) |

| Saber et al. [58] | Saudi Arabia | 2012–2014 | 2015 | CS | 131 | - | PCR, IgG antibody/culture | 43 | GC | Histopathology | 32.82 (24.88 to 41.57) |

| Matsunari et al. [59] | Japan | 1993–2005 | 2012 | CS | 291 | - | Culture, PCR | 23 | GC | Endoscopy/histological | 7.9 (5.08 to 11.62) |

| Khatoon et al. [169] | India | 2012–2016 | 2017 | CS | 122 | - |

RUT/culture/histology PCR |

40 | GC | Endoscopy | 32.79 (24.56 to 41.87) |

| Ghoshal et al. [60] | India | - | 2013 | PCS | 185 | - | RUT/ELISA | 49 | GC | Endoscopy & biopsy | 26.49 (20.28 to 33.46) |

| Amiri et al. [61] | Iran | 2012–2013 | 2016 | CS | 86 | - | RUT/histopathological qRT-PCR | 20 | GC | Histopathological | 23.26 (14.82 to 33.61) |

| Farajzadeh Sheikh et al. [62] | Iran | 2014–2015 | 2018 | CS | 201 | - |

PCR, Gram staining Urease test, culture |

22 | GC | Histopathological | 10.95 (6.99 to 16.1) |

| El Khadir et al. [63] | Morocco | 2009–2019 | 2021 | CS | 823 | 48.2 | PCR | 75 | GC | Endoscopically / histological | 9.11 (7.24 to 11.29) |

| Pandey et al. [170] | India | 2007–2012 | 2014 | PCS | 99 | - | PCR | 34 | 44 diffuse/ 21 intestinal adenocarcinoma | Histological | 34.34 (25.09 to 44.56) |

| Park et al. [64] | Korea | 2008–2013 | 2016 | CS | 10,947 | - | Immunoglobulin, RUT, pathology | 45 | GC | Histological | 0.41 (0.3 to 0.55) |

| Kawamura et al. [65] | Japan | 2007–2010 | 2013 | PCS | 139 | - | RUT | 61 | Differentiated: 46 Undifferentiated GC: 21 | Magnifying endoscopy histological | 43.88 (35.49 to 52.55) |

| Raza et al. [66] | Pakistan | - | 2017 | Prospective | 168 | - | PCR | 55 | GC | Histopathological | 32.74 (25.71 to 40.39) |

| Yoon et al. [171] | Korea | 2006–2014 | 2019 | CS | 303 | - | Giemsa, RUT, culture ELISA | 170 | GC Intestinal: 119, Diffuse: 51 | Endoscopically | 56.11 (50.32 to 61.77) |

| Santos et al. [67] | Brazil | - | 2020 | PCS | 92 | - | PCR | 32 | GC | Histopathological | 34.78 (25.15 to 45.43) |

| Guo et al. [69] | China | 2010–2012 | 2014 | CS | 50 | - | RUT, UBT, Serology | 17 | GC, Intestinal:18, Diffuse: 18 | Histopathological | 34 (21.21 to 48.77) |

| Haddadi et al. [93] | Iran | 2013 | 2015 | CS | 128 | 26 | Culture, PCR | 14 | GC | Histopathological | 10.94 (6.11 to 17.67) |

| Wei et al. [172] | Taiwan | - | 2021 | Cohort | 48 | 69 | - | 43 | GC | - | 89.58 (77.34 to 96.53) |

Pooled prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients

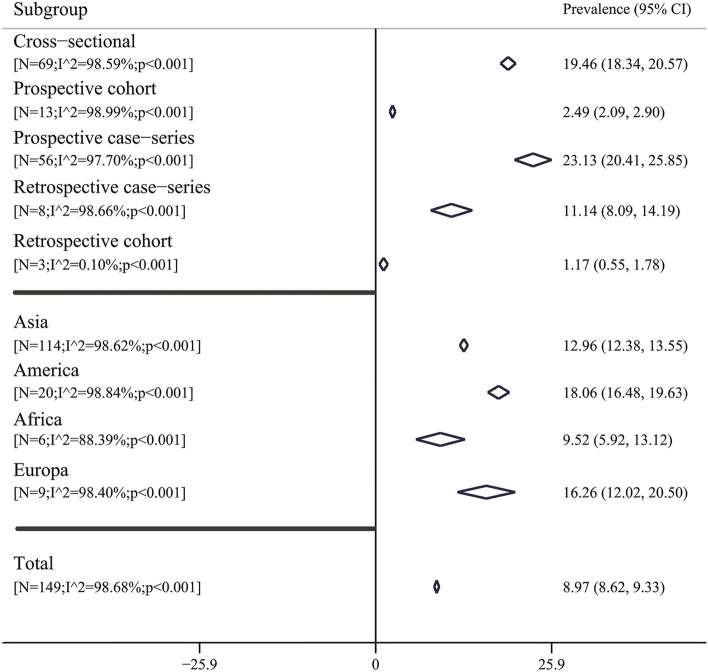

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients. Minimum and maximum prevalence were in Doorakkers et al. [107] study (Prevalence: 0.07%; 95% CI: 0.06–0.09) from the Sweden and Tanaka et al. [161] (Prevalence: 90.90%:95% CI: 83.61–95.14) from Japan, respectively. Due to high heterogeneity and different study design, results don’t merge and presented based on different subgroups

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of prevalence of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori positive patients

Pooled prevalence of gastric cancer in H. pylori positive patients based on different subgroups

Pooled prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients based on study design and continents are listed in Fig. 3 and Table 4. Based on design, the highest and lowest prevalence was observed in prospective case series (pooled prevalence: 23.13%; 95% CI: 20.41 − 25.85; I2: 97.70%) and retrospective cohort (pooled prevalence: 1.17%; 95% CI: 0.55 − 1.78; I 2: 0.10%), respectively. Also based on continents, the highest and lowest prevalence was observed in America (pooled prevalence: 18.06%; 95% CI: 16.48 − 19.63; I2: 98.84%) and Africa (pooled prevalence: 9.52%; 95% CI: 5.92 − 13.12; I2: 88.39%) continents, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Pooled prevalence with 95% confidence interval [CI] and heterogeneity indexes of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori positive patients based on type of the design and continents places. The diamond mark illustrates the pooled prevalence and the length of the diamond indicates the 95% CI

Table 4.

Result of meta-analysis, publication bias and fill-trim method for prevalence estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval of gastric cancer in H.pylori positive patients

| Subgroup | Meta-analysis | Publication bias (Egger’s test) | Fill-trim method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | Heterogeneity index |

Pooled prevalence% (95% CI) |

Coefficient (95% CI) |

p-value |

Adj-pooled prevalence% (95% CI) |

|

| Study design | ||||||

| Cross sectional | 69 | I2 = 98.59%; p < 0.001 | 19.46 (18.34 to 20.57) | 7.09 (5.82 to 8.36) | < 0.001 | 7.89 (6.78 to 9.01) |

| Prospective cohort | 13 | I2 = 98.99%; p < 0.001 | 2.49 (2.09 to 2.90) | 8.59 (4.33 to 12.84) | 0.001 | 1.13 (0.65 to 1.61) |

| Prospective case series | 56 | I2 = 97.70%; p < 0.001 | 23.13 (20.41 to 25.85) | 6.07 (5.15 to 6.98) | < 0.001 | 16.23 (13.76 to 18.69) |

| Retrospective case series | 8 | I2 = 98.66%; p < 0.001 | 11.14 (8.09 to 14.19) | 6.30 (-1.45 to 14.05) | 0.094 | –- |

| Retrospective cohort | 3 | I2 = 0.10%; p < 0.001 | 1.17 (0.55 to 1.78) | 5.79 (-7.04 to 18.62) | 0.110 | –- |

| Continents | ||||||

| Asia | 114 | I2 = 98.62%; p < 0.001 | 12.96 (12.38 to 13.55) | 6.33 (2.03 to 10.63) | 0.010 | 4.37 (0.03 to 8.75) |

| America | 20 | I2 = 98.84%; p < 0.001 | 18.06 (16.48 to19.63) | 6.89 (5.87 to 7.92) | < 0.001 | 6.43 (7.02 to 21.43) |

| Africa | 6 | I2 = 88.39%; p < 0.001 | 9.52 (5.92 to 13.12) | 3.41 (-3.42 to 10.26) | 0.239 | –- |

| Europa | 9 | I2 = 98.40%; p < 0.001 | 16.26 (12.02 to 20.50) | 8.09 (5.54 to 10.64) | < 0.001 | 7.10 (5.58 to 8.63) |

CI Confidence interval, NS Number of studies

Heterogeneity and meta‐regression

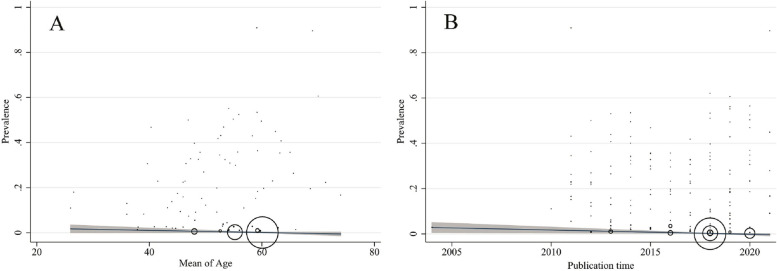

Heterogeneity results are available in Table 4. Cochran's Q test showed the included studies had high heterogeneity (p < 0.001). The I2 index for total prevalence was up to 98%. The result of univariate meta‐regression analysis (Table 5) showed the age (Coefficient: 0.59; p: 0.009), sample size (Coefficient: − 0.1; p: 0.003) and study design (based WHO regional office) (Coefficient: 3.72; p: 0.015) possess significant effect on the studies heterogeneity (Fig. 4A and B) and have eligible to include to multiple model. The result of multiple meta‐regression analysis showed the just age (Coefficient: 0.66; p: 0.003) have a significant effect on the studies heterogeneity. The R2-adj for multiple model was 13.63% and this mean the age, Sample size and study design explained the about 14% of total heterogeneity of prevalence.

Table 5.

The univariate and multiple meta-regression analysis on the determinant heterogeneity in effect of iron therapy on depression

| Variables | Univariate meta-regression | Multiple meta-regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | R2-adj | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | R2-adj | |

| Publication time (yrs.) | 0.43 (-0.53 to 1.39) | 0.382 | 0.1% | Not included | –- | 13.63% |

| Continents (score) | 1.60 (-2.43 to 5.63) | 0.433 | 0.02% | Not included | –- | |

| Age mean (yrs.) | 0.59 (0.15 to 1.03) | 0.009 | 6.96% | 0.66 (0.24 to 1.08) | 0.003 | |

| Sample size (number) | -0.01 (-0.02 to -0.01) | 0.003 | 5.41% | 0.-01 (-0.2 to 0.01) | 0.84 | |

| Study design (score) | 3.72 (0.73 to 6.71) | 0.015 | 3.49% | 3.08 (-0.92 to 7.08) | 0.130 | |

CI Confidence Interval, Coding of study design: 1 = Retrospective cohort; 2 = Prospective cohort; 3 = Retrospective case-series; 4 = Cross sectional; 5 = Prospective case-series

Coding of study continent: 1 = Africa; 2 = America; 3 = Asia; 4 = Europa

*Significant at 0.05

Fig. 4.

Association between Pooled prevalence of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori positive patients with age (A) and publication year (B) by means of meta-regression. The size of circles indicates the precision of each study. There is a positive significant association with respect to the pooled prevalence with age

Publication bias

The results of Egger’s test showed significant publication bias in our meta-analysis which provided in Table 4. For adjustment of pooled prevalence, fill and trim method was used that result was showed in Table 4. Based on this result, publication-bias-adjusted pooled prevalence estimation for cross sectional was 7.89% (95% CI: 6.78—9.01) which was different with pooled prevalence estimation based on meta-analysis 19.46% (95% CI: 18.34 to 20.57). Result of fill and trim method for other subgroups was showed in Table 4.

Discussion

Infection with H. pylori causes chronic inflammation and significantly increases the risk of developing duodenal and gastric ulcer disease and GC. H. pylori primarily infect the epithelial cells in the stomach and can survive in humans for decades by inhibiting the immune system responsiveness, results inducing chronic inflammatory responses. Because of endotoxin elaboration and other inflammatory exudates, the colonization of the gastric mucosa by H. pylori has been observed with gastric atrophy [173]. Researchers have recently reported molecular aspects that highlight the importance of certain apoptotic genes and proteins including C-Myc, P53, Bcl2, and Rb-suppressor systems in H. pylori pathogenesis. H. pylori infection has also been shown to be related to nitric oxide (NOSi genotype) [70]. Induction of apoptosis in gastric mucosa by H. pylori involves upregulation of Bax and Bcl-2 [70].

With H. pylori involvement in the gastric intestinal pH alteration, dysplasia has been observed in patients with H. pylori infection [174]. Previous studies have been shown that individuals who had been infected with H. pylori were six times more likely to develop GC compared with healthy people [175]. In this study, using random-effects model approach, pooled prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients was 8.97% (95% CI: 8.62–9.33) [N = 149; I2 = 98.68%]. Therefore, from every 1000 H. pylori positive patients, 8.62 to 9.33 individuals get GC. The frequency of H. pylori in people less than 50 years old was reported as 41.9%.

The study by Vohlonen et al. showed risk ratio (RR) of stomach cancer in people with H. pylori infection was 5.8 (95%CI: 2.7–15.3) compared to people with healthy stomachs, and 9.1 (95%, CI: 2.9–30.0) in men with atrophic gastritis [86]. The present observation also demonstrated that an H. pylori infection alone (non-atrophic H. pylori gastritis) is by itself a clear risk condition for GC as was suggested by the IARC/WHO statement in 1994 [176]. In study conducted before 1998, by approximately 800 GC cases, the analysis yielded a risk ratios of 2.5 (95% CI: 1.9–3.4) for GC in H. pylori-seropositive people [177]. Another study including 233 GCs and 910 controls, yielded a risk ratios of 6.5 (95%CI: 3.3–12.6) for non-cardia GC in subjects infected with a cytotoxic (CagA) H. pylori strain [178]. In another study, the risk ratios of GC was 3.1 (95%CI: 1.97–4.95) between H. pylori infected and non-infected persons [179]. The risk ratios, based on case–control study designs, varied between 1.6 and 7.9 in three published papers from two extensive prospective nutritional intervention trials of over 29,000 males at age of 50–69 years in Linxian, China and Finland [180–182].

Our estimate of the prevalence of GC due to H. pylori infection in cross sectional studies was 19.46% (95% CI: 18.34—20.57) [N = 69; I2 = 98.59%], Therefore, from every 1000 H. pylori positive patients, 183 to 206 individuals get GC.

The simple infection markedly increases the cancer risk when compared to a healthy stomach. The risk varies between the populations with the highest and lowest by 15 to 20 times. East Asia (China and Japan), South America, Eastern Europe, and Central America are the high-risk regions. North and East Africa, North America, Southern Asia, New Zealand, and Australia are the low-risk regions [183].

Our study noted the lowest prevalence of GC in H. pylori positive patients from the Sweden (Prevalence: 0.07%; 95% CI: 0.06–0.09) [107] and the highest from the Japan (Prevalence: 90.90%:95% CI: 83.61–95.14) [161].

This difference may be due to the following reasons: dietary habits, socio-economic status and racial disparities. Suerbaum et al. [184] have mentioned that populations with lower socioeconomic status were more likely to be infected with H. pylori. Data based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys of the United States have also shown that racial disparities played a certain role in the prevalence of H. pylori. The prevalence of H. pylori in African Americans was higher than whites [185]. The findings of the studies showed that Blacks and Hispanics consistently have higher H. pylori prevalence, serologic markers, and histologic signs than whites. Generally, the prevalence of CagA in adult people with H. pylori positivity ranged from 71%-90% in blacks, 64%-74% in Hispanics, and 36% to 77% in whites. Studies that amplified the VacA m allelic region for genomic characterization discovered that Blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites to carry the virulent VacA-m1 genotype [186]. It has been hypothesized that racial discrepancies associated with H. pylori are contributed to GC incidence and mortality.

The evidence that is currently available implies that practitioners should be aware that the prevalence of H. pylori varies depending on race [187]. Perhaps it would be better if we personalized GC prevention and improved clinical management for all patients.

The results of subgroup analysis, based on our design, the highest and lowest prevalence was observed in prospective case series (pooled prevalence: 23.13%; 95% CI: 20.41 − 25.85; I2: 97.70%) and retrospective cohort (pooled prevalence: 1.17%; 95% CI: 0.55 − 1.78; I 2: 0.10%). The highest and lowest prevalence of GC in H. pylori patients was observed in America (pooled prevalence: 18.06%; 95% CI: 16.48 − 19.63; I2: 98.84%) and Africa (pooled prevalence: 9.52%; 95% CI: 5.92 − 13.12; I2: 88.39%) continents, respectively.

Steady declines in GC incidence rates have been observed worldwide in the last few decades [183]. The general declining incidence of GC may be explained by higher standards of hygiene, improved food conservation, a high intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, and by H. pylori eradication [188]. Current treatment for H. pylori infection includes antisecretory agents or bismuth citrate plus two or more antimicrobials. Clarithromycin and metronidazole are the most commonly used antibiotics to treat H. pylori infection. Increasing resistance of H. pylori to metronidazole and clarithromycin has made current therapies with these antibiotics less successful [68]. Bismuth triple therapy is not very effective in the presence of a high prevalence of metronidazole resistance, unless higher doses of metronidazole are prescribed to increase the cure rate of therapy. Resistance to the major anti-H pylori antibiotics, the final duration of therapy, and the prescribed antibiotic dose are all factors that affect the efficacy of therapy. Host genetic polymorphisms may also influence the efficacy of therapy [189].

The results of our study indicated a significant heterogeneity (p < 0.001) in the prevalence of H. pylori in GC across different geographical regions. The result of univariate meta‐regression analysis showed the age, sample size and study design possess significant effect on the studies heterogeneity and have eligible to include to multiple model. The results of multiple meta‐regression analysis showed the just age have a significant effect on the studies heterogeneity. The R2-adj for multiple model was 13.63% and this mean the age, sample size and study design explained the about 14% of total heterogeneity of prevalence. This was in accordance with a recent study that assessed the prevalence of H. pylori in gastrointestinal disease cases [97]. Study performed by Spineli et al. [98] revealed that subgroup analysis may not be powerful enough to test for relationships between variables when fewer studies are involved. However, type of sample was significantly associated with H. pylori prevalence [184]. Although subgroup analysis and meta-regression were performed to minimize the heterogeneity across the included studies, significant heterogeneity still could be observed in subgroup analysis. Moreover, some important factors like drinking and dietary habit could not be extracted from the included studies, which might have potential influence on the heterogeneity.

Therefore, these results should be considered with caution and more studies are needed to further confirm these results in the future.

In general, limitations of meta-analyses are that the validity is dependent on the quality of the included studies, on heterogeneity between studies, and on possible publication bias; but we tried to deal of them by statistical manner. Indeed we dealt to heterogeneity by using random effects model, subgroup and meta-regression analysis. Also we tried to deal publication bias by use the fill and trim method to estimate the publication-bias-adjusted-pooled.

Conclusions

In our study by evaluate the 149 studies and 352,872 sample size illustrated that prevalence of GC in patient with H. pylori was considerable. But the rate was varied based on different subgroups so that the rate was highest among in America continent but was lowest in Africa continent. Also, using meta-regression and assessment the effect of several variables, indicated that age, sample size and study design explained the about 14% of total heterogeneity. It is advised to launch appropriate control guidelines for high-risk region. The risk of different factors should also be taken into account when developing GC decrease strategies, even though H. pylori eradication may be a promising method for preventing the disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- GC

Gastric cancer

- NOS

Newcastle Ottawa scale

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR

Risk ratio

Authors’ contributions

SK, RP, and MHH conceived and designed the study; MHH, SA, AA, HK, MM, and VHK collected and aggregated data; SA, HK, AR, MSha, MShir, and RT analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; MSha, HK, RT, MSak and MH reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included here and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Maryam Shirani and Reza Pakzad contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Mohsen Heidary, Email: mohsenheidary40@gmail.com.

Morteza Saki, Email: mortezasaki1981@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pormohammad A, Mohtavinejad N, Gholizadeh P, Dabiri H, Salimi Chirani A, Hashemi A, et al. Global estimate of gastric cancer in Helicobacter pylori–infected population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(2):1208–1218. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia Z, Zheng M, Jiang J, Cao D, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Positive H. pylori status predicts better prognosis of non-cardiac gastric cancer patients: results from cohort study and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09222-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haley KP, Gaddy JA. Helicobacter pylori: genomic insight into the host-pathogen interaction. Int J Genomics. 2015;2015:386905. doi: 10.1155/2015/386905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polk DB, Peek RM. Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):403–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díaz P, Valenzuela Valderrama M, Bravo J, Quest AF. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: adaptive cellular mechanisms involved in disease progression. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:5. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(5):1133–1145. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y, Xiao F, Wang Y, Wang Z, Liu D, Hong F. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori in non-cardia gastric cancer in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:850389. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.850389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold M, Ferlay J, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of oesophageal and gastric cancer by histology and subsite in 2018. Gut. 2020;69(9):1564–1571. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(2):e180–e190. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghoshal UC, Chaturvedi R, Correa P. The enigma of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:95–100. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International WCRF . Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective: a summary of the Third Expert Report: World Cancer Research Fund International. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Chu KM. E-cadherin and gastric cancer: cause, consequence, and applications. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ishaq S, Nunn L. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a state of the art review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8(Suppl1):S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balakrishnan M, George R, Sharma A, Graham DY. Changing trends in stomach cancer throughout the world. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(8):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pounder R, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, Bankole A, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. The Lancet. 2016;388(10041):258–267. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30380-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dadashzadeh K, Peppelenbosch MP, Adamu AI. Helicobacter pylori pathogenicity factors related to gastric cancer. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:7942489. doi: 10.1155/2017/7942489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yakoob J, Abbas Z, Jafri W, Khan R, Salim SA, Awan S, et al. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane protein and virulence marker differences in expatriate patients. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(10):2200–8. doi: 10.1017/S095026881600025X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang TT, Cao N, Zhang HH, Wei JB, Song XX, Yi DM, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection-induced H3Ser10 phosphorylation in stepwise gastric carcinogenesis and its clinical implications. Helicobacter. 2018;23(3):e12486. doi: 10.1111/hel.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li HJ, Fang EH, Wang JQ, Zheng LD, Tong QS. Helicobacter pylori infection facilitates the expression of resistin-like molecule beta in gastric carcinoma and precursor lesions. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40(1):95–103. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2151-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey R, Misra V, Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra A. Helicobacter pylori infection and a P53 codon 72 single nucleotide polymorphism: a reason for an unexplained Asian enigma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(21):9171–9176. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.21.9171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouyang Y, Liu G, Xu W, Yang Z, Li N, Xie C, et al. Helicobacter pylori induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric carcinogenesis via the AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(2):1. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alaoui Boukhris S, Amarti A, El Rhazi K, El Khadir M, Benajah D-A, Ibrahimi SA, et al. Helicobacter pylori genotypes associated with gastric histo-pathological damages in a Moroccan population. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunaletchumy SP, Seevasant I, Tan MH, Croft LJ, Mitchell HM, Goh KL, et al. Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity and gastro-duodenal diseases in Malaysia. Sci Rep. 2014;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep07431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raei N, Latifi-Navid S, Zahri S. Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island cagL and orf17 genotypes predict risk of peptic ulcerations but not gastric cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6645–6650. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.15.6645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdi E, Latifi-Navid S, Yazdanbod A, Zahri S. Helicobacter pylori babA2 positivity predicts risk of gastric cancer in Ardabil, a very high-risk area in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(2):733–738. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.2.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ansari S, Kabamba ET, Shrestha PK, Aftab H, Myint T, Tshering L, et al. Helicobacter pylori bab characterization in clinical isolates from Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal and Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohammadi M, Abadi ATB, Rahimi F, Forootan M. Helicobacter heilmannii colonization is associated with high risk for gastritis. Arch Med Res. 2019;50(7):423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh YC, Kuo HY, Chang WL, Yang HB, Lu CC, Cheng H-C, et al. H. pylori isolates with amino acid sequence polymorphisms as presence of both HtrA-L171 & CagL-Y58/E59 increase the risk of gastric cancer. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez EG, Partida-Rodriguez O, Camorlinga-Ponce M, Nieves-Ramirez M, Ramos-Vega I, Torres J, et al. Genotype B of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor is related with gastric cancer lesions. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24464-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng HM, Pan KF, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma JL, Zhou T, et al. Genetic Variants of Toll-Like Receptor 2 and 5, Helicobacter Pylori Infection, and Risk of Gastric Cancer and Its Precursors in a Chinese PopulationPolymorphisms of Toll-Like Receptors and Gastric Cancer and Its Precursors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(12):2594–2602. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boonyanugomol W, Kongkasame W, Palittapongarnpim P, Baik SC, Jung MH, Shin MK, et al. Genetic variation in the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori strains detected from gastroduodenal patients in Thailand. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51(3):1093–101. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00292-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Xin Y, Zhou J, Tian Z, Liu C, Yu X, et al. Gastric mucosa-associated microbial signatures of early gastric cancer. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1548. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakitani K, Hirata Y, Suzuki N, Shichijo S, Yanai A, Serizawa T, et al. Gastric cancer diagnosed after Helicobacter pylori eradication in diabetes mellitus patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekikawa A, Fukui H, Sada R, Fukuhara M, Marui S, Tanke G, et al. Gastric atrophy and xanthelasma are markers for predicting the development of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pakbaz Z, Shirazi MH, Ranjbar R, Gholi MK, Aliramezani A, Malekshahi ZV. Frequency *scent Medical Journal. 2013;15(9):767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Shadman M, Rajabian Z, Ajami A, Hussein-Nattaj H, Rafiei A, Hosseini V, et al. Frequency of γδ T cells and invariant natural killer T cells in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;14:493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Archampong TN, Asmah RH, Wiredu EK, Gyasi RK, Nkrumah KN. Factors associated with gastro-duodenal disease in patients undergoing upper GI endoscopy at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16(2):611–619. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi S, Ogura M, Suzawa N, Horiki N, Katsurahara M, Ogura T, et al. 18F-FDG uptake in the stomach on screening PET/CT: Value for predicting Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic atrophic gastritis. BMC Med Imaging. 2016;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12880-016-0161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie C, Xu LY, Yang Z, Cao XM, Li W, Lu NH. Expression of γH2AX in various gastric pathologies and its association with Helicobacter pylori infection. Oncol Lett. 2014;7(1):159–163. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng N, Liu JW, Sun LP, Xu Q, Duan ZP, Dong NN, et al. Expression of XPG protein in the development, progression and prognosis of gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi YY, Chen M, Zhang YX, Zhang J, Ding SG. Expression of three essential antioxidants of Helicobacter pylori in clinical isolates. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2014;15(5):500–6. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1300171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zabaglia LM, Sallas ML, Santos MPd, Orcini WA, Peruquetti RL, Constantino DH, et al. Expression of miRNA-146a, miRNA-155, IL-2, and TNF-α in inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection associated with cancer progression. Ann Hum Genet. 2018;82(3):135–42. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szkaradkiewicz A, Karpiński TM, Linke K, Majewski P, Rożkiewicz D, Goślińska-Kuźniarek O. Expression of cagA, virB/D complex and/or vacA genes in Helicobacter pylori strains originating from patients with gastric diseases. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorge YC, Mataruco MM, Araújo LP, Rossi AFT, De Oliveira JG, Valsechi MC, et al. Expression of annexin-A1 and galectin-1 anti-inflammatory proteins and mRNA in chronic gastritis and gastric cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:152860. doi: 10.1155/2013/152860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taghizadeh S, Sankian M, Ajami A, Tehrani M, Hafezi N, Mohammadian R, et al. Expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factors a and C in patients with peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14(3):196–203. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2014.14.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan X, Hu X, Duan B, Zhang X, Pan J, Fu J, et al. Exploration of endoscopic findings and risk factors of early gastric cancer after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021;56(3):356–362. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1868567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anwar M, Youssef A, Sheta M, Zaki A, Bernaba N, El Toukhi M. Evaluation of specific biochemical indicators of Helicobactepylori-associated gastric cancer in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(5):501–507. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park CH, Lee AR, Lee YR, Eun CS, Lee SK, Han DS. Evaluation of gastric microbiome and metagenomic function in patients with intestinal metaplasia using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Helicobacter. 2019;24(1):e12547. doi: 10.1111/hel.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toyoshima O, Yamaji Y, Yoshida S, Matsumoto S, Yamashita H, Kanazawa T, et al. Endoscopic gastric atrophy is strongly associated with gastric cancer development after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(5):2140–2148. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi S, Joshita S, Yamamoto C, Yanagisawa T, Miyazawa T, Miyazawa M, et al. Efficacy and safety of eradication therapy for elderly patients with helicobacter pylori infection. Medicine. 2019;98(30):e16619. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boonyanugomol W, Kongkasame W, Palittapongarnpim P, Jung M, Shin M-K, Kang H-L, et al. Distinct Genetic Variation of Helicobacter pylori cagA, vacA, oipA, and sabA Genes in Thai and Korean Dyspeptic Patients. Microbiol Biotechnol Lett. 2018;46(3):261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandey A, Tripathi SC, Shukla S, Mahata S, Vishnoi K, Misra SP, et al. Differentially localized survivin and STAT3 as markers of gastric cancer progression: Association with Helicobacter pylori. Cancer Rep. 2018;1(1):e1004. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Q, Song C, Wang K, Li D, Yang Y, Liu D, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori babA, oipA, sabA, and homB genes in isolates from Chinese patients with different gastroduodenal diseases. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2020;209(5):565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00430-020-00666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abu-Taleb AM, Abdelattef RS, Abdel-Hady AA, Omran FH, El-Korashi LA, El-hady AA, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori cagA and iceA genes and their association with gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Microbiol. 2018;2018:4809093. doi: 10.1155/2018/4809093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saber T, Ghonaim MM, Yousef AR, Khalifa A, Qurashi HA, Shaqhan M, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori cagA gene with gastric cancer and peptic ulcer in saudi patients. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;25(7):1146–1153. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1501.01099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsunari O, Shiota S, Suzuki R, Watada M, Kinjo N, Murakami K, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori virulence factors and gastroduodenal diseases in Okinawa, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(3):876–883. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05562-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghoshal U, Kumar S, Jaiswal V, Tripathi S, Mittal B, Ghoshal UC. Association of microsomal epoxide hydrolase exon 3 Tyr113His and exon 4 His139Arg polymorphisms with gastric cancer in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32(4):246–252. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amiri RM, Tehrani M, Taghizadeh S, Shokri-Shirvani J, Fakheri H, Ajami A. Association of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptors with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;15:355–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheikh AF, Yadyad MJ, Goodarzi H, Hashemi SJ, Aslani S, Assarzadegan M-A, et al. CagA and vacA allelic combination of Helicobacter pylori in gastroduodenal disorders. Microb Pathog. 2018;122:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El Khadir M, Boukhris SA, Zahir SO, Benajah D-A, Ibrahimi SA, Chbani L, et al. CagE, cagA and cagA 3′ region polymorphism of Helicobacter pylori and their association with the intra-gastric diseases in Moroccan population. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;100(3):115372. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park YM, Kim J-H, Baik SJ, Park JJ, Youn YH, Park H. Clinical risk assessment for gastric cancer in asymptomatic population after a health check-up: an individualized consideration of the risk factors. Medicine. 2016;95(44):e5351. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawamura M, Sekine H, Abe S, Shibuya D, Kato K, Masuda T. Clinical significance of white gastric crypt openings observed via magnifying endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(48):9392. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raza Y, Khan A, Khan AI, Khan S, Akhter S, Mubarak M, et al. Combination of interleukin 1 polymorphism and Helicobacter pylori infection: an increased risk of gastric cancer in Pakistani population. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23(4):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s12253-017-0191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dos Santos MP, Pereira JN, De Labio RW, Carneiro LC, Pontes JC, Barbosa MS, et al. Decrease of miR-125a-5p in gastritis and gastric cancer and its possible association with H. pylori. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2021;52(2):569–74. doi: 10.1007/s12029-020-00432-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomatari FH, Mobarez AM, Amini M, Hosseini D, Abadi ATB. Helicobacter pylori Resistance to Metronidazole and Clarithromycin in Dyspeptic Patients in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2010;12(4):409. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo XY, Dong L, Qin B, Jiang J, Shi AM. Decreased expression of gastrokine 1 in gastric mucosa of gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16702. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]