Abstract

We report a new computational protein design method for the construction of oligomeric protein assemblies around metal centers with predefined coordination geometries. We apply this method to design two homotrimeric assemblies, Tet4 and TP1, with tetrahedral and trigonal pyramidal tris-histidine metal coordination geometries, respectively, and demonstrate that both assemblies form the targeted metal centers with ≤0.2-Å accuracy. Although Tet4 and TP1 are constructed from the same parent protein building block, they are distinct in terms of their overall architectures, the environment surrounding the metal centers, and their metal-based reactivities, illustrating the versatility of our approach.

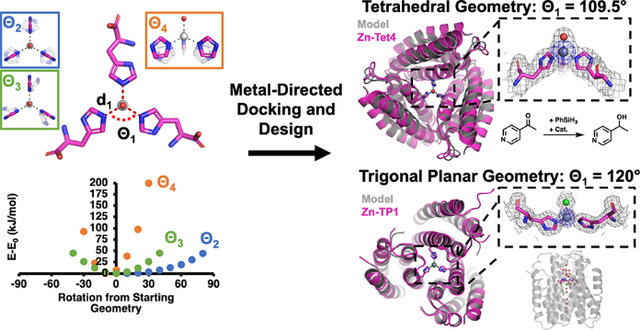

Graphical Abstract

Despite a limited set of bioavailable metal ions and amino acids capable of metal coordination, natural metalloproteins perform diverse functions including signaling,1–2 electron transfer,3–4 small molecule transport,5–6 and catalysis.7–10 Underlying such functional diversity is an intricate interplay between protein structure and metal coordination.11–16 While this interplay takes place at several levels (e.g., overall protein structure/dynamics, secondary coordination sphere surrounding the metal center), the core determinant of a metalloprotein’s function is the metal center itself, the ligand composition, and the geometry of the primary coordination sphere.17 An accurate control of the metal coordination geometry by the protein structure is required not only for the selective binding of a cognate metal ion18–23 but also for tuning its inherent reactivity,24 as exemplified by many biological metal centers that are scaffolded in coordinatively unsaturated and strained geometries.9, 25 Inspired by natural bioinorganic systems, there has been great interest in designing proteins featuring metal centers with tailored geometries and reactivities/properties.13, 26–27 However, despite advances in computational protein design and the development of metal search/placement algorithms,28–31 the sub-Å positional accuracy needed for this purpose has yet to be demonstrated.

To date, most de novo designed metalloproteins have been based on α-helical motifs.13, 32–34 The small sizes and highly parametrizable nature of these systems have facilitated the incorporation of metal ions with desired coordination environments and proved invaluable in exploring the minimal structural requirements in proteins for metal-based functions.26, 33, 35–41 Yet, the same features also restrict the scope of metal active sites and geometries that can be accommodated as well as the incorporation of functionally important structural motifs (e.g., large cavities, flexible loops). Similar challenges also apply to non-α-helical peptide motifs.42–48 Examples of larger, designed metalloproteins have entailed either coordinatively saturated metal centers,49 resulted in unexpected deviations from targeted coordination geometries,50–52 or relied on recreating secondary structure elements adopted from natural metalloproteins.53–54 We developed an alternative design approach (Metal-Templated Interface Redesign) based on the metal-directed self-assembly of protein building blocks into oligomeric architectures.55–57 Using the structures of these assemblies as a template, the protein-protein interfaces bearing the nucleating metal centers are engineered to increase preorganization for metal binding and obtain diverse metal-based functions.22, 58–64 However, the structural outcome of metal-directed protein assembly is not always predictable, and the resulting interfacial metal centers are generally–but not always–coordinatively saturated, limiting access to alternative coordination geometries of interest.11–12, 57

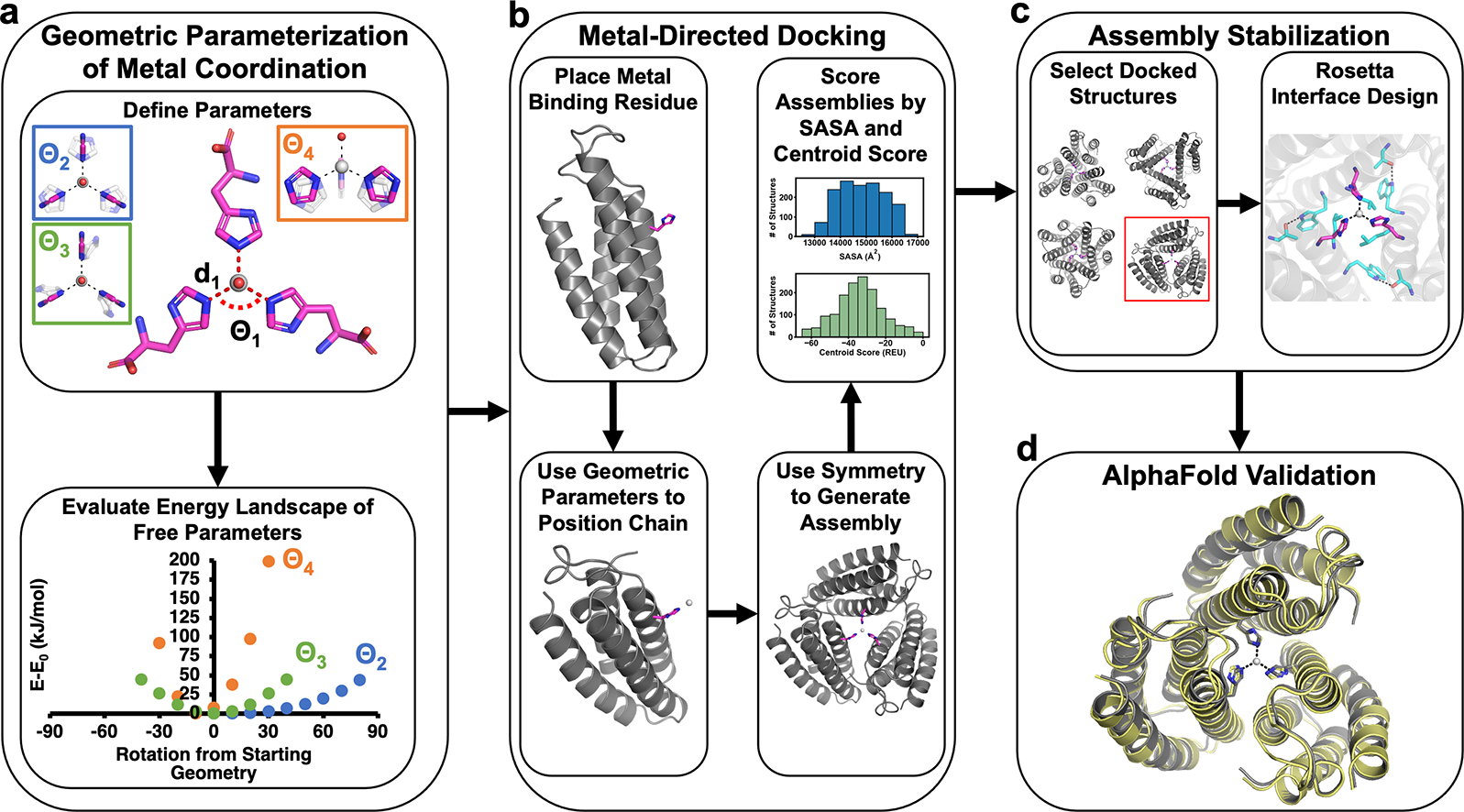

To overcome these limitations, we have developed a new computational design strategy, in which oligomeric protein assemblies are built around metal centers with predefined coordination geometries. As our initial target, we chose a coordinatively unsaturated, tris-histidine-coordinated ZnIl center with an exchangeable ligand (Zn-His3X) in a tetrahedral geometry, found in the active sites of enzymes such as carbonic anhydrases and matrix metalloproteinases.65–69 As our model building block, we used an engineered, heme-free variant of cytochrome cb562, ApoCyt, a four-helix bundle protein that is stable, tolerant to mutations, and crystallizes readily.70 The first step in our workflow involved defining the geometric parameters for the targeted metal coordination geometry (Figure 1a). An ideal tetrahedral Zn-His3X center is C3 symmetric and can be described with five parameters: d1 and Θ1 for the Zn-His bond distance and His-Zn-His bond angles, respectively, and Θ2, Θ3, and Θ4 for the rotation of the imidazole ring (Figure 1a). For a tetrahedron, Θ1 = 109.5°, and d1 was set at 2.0 Å.71 Using simple ZnII(imidazole)3(OH) models, we performed a series of density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which revealed that varying Θ2 had the least effect on the energy of the system, whereas deviations of Θ4 from 0° resulted in largest increases in energy. Based on these results, we used the following ranges in subsequent design stages: −40°≤ Θ2 ≤+40°, −15°≤ Θ3 ≤+15, and −15°≤ Θ4 ≤0°.

Figure 1.

Workflow for the design of protein assemblies with predefined metal coordination geometries.

Next, we implemented a protein docking procedure (termed Metal-Directed Protein Docking, Figure 1b) to place three C3-symmetry-related ApoCyt monomers to form the desired Zn-His3X center (within the allowable Θ2, Θ3, Θ4 ranges), while yielding sufficiently large intermonomer interfaces that can be redesigned to stabilize the resulting assembly. Briefly, this procedure involved: (1) placement of a His residue at a manually chosen position (38 or 66) on each monomer; (2) calculation of sidechain coordinates based on a given set of geometric parameters (d, Θ’s) and the symmetry of the metal center; (3) energetic evaluation of the resulting assemblies based on solvent accessible surface areas (SASA) of the monomers and a Rosetta72 centroid score function to identify backbone clashes; (4) repetition of steps 1–3 to sample combinations of His positions, geometric parameters, and torsion angles to yield a library of trimeric ApoCyt structures with a Zn-His3X center. From this library, we selected several structures for multiple iterations of interface redesign by Rosetta (Figure 1c),72 ultimately yielding seven designs encompassing five distinct docking geometries (Figure S1) that were then evaluated using AlphaFold273 for structure prediction (Figure 1d). Of these seven designs, five had significant disagreement (αC-RMSD >10 Å) between the computed model and the AlphaFold2 prediction, whereas two had good agreement (αC-RMSD <2.5 Å, Figure S2). Upon bacterial expression and purification of the two promising designs, one was found to be predominantly monomeric in solution, whereas the second, Tet4, formed a metal-independent trimer as desired, with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 2.7 nM for ZnII (Figures 2a, S3). In contrast, four of the five designs that showed large deviations from AlphaFold2 predictions either failed to express in bacterial cultures or did not assemble into a trimer (Table S1, Figure S4), validating the in silico screening step. The remaining design formed a trimer but did not crystallize and possessed >10-fold weaker affinity for ZnII than Tet4 (Figure S3).

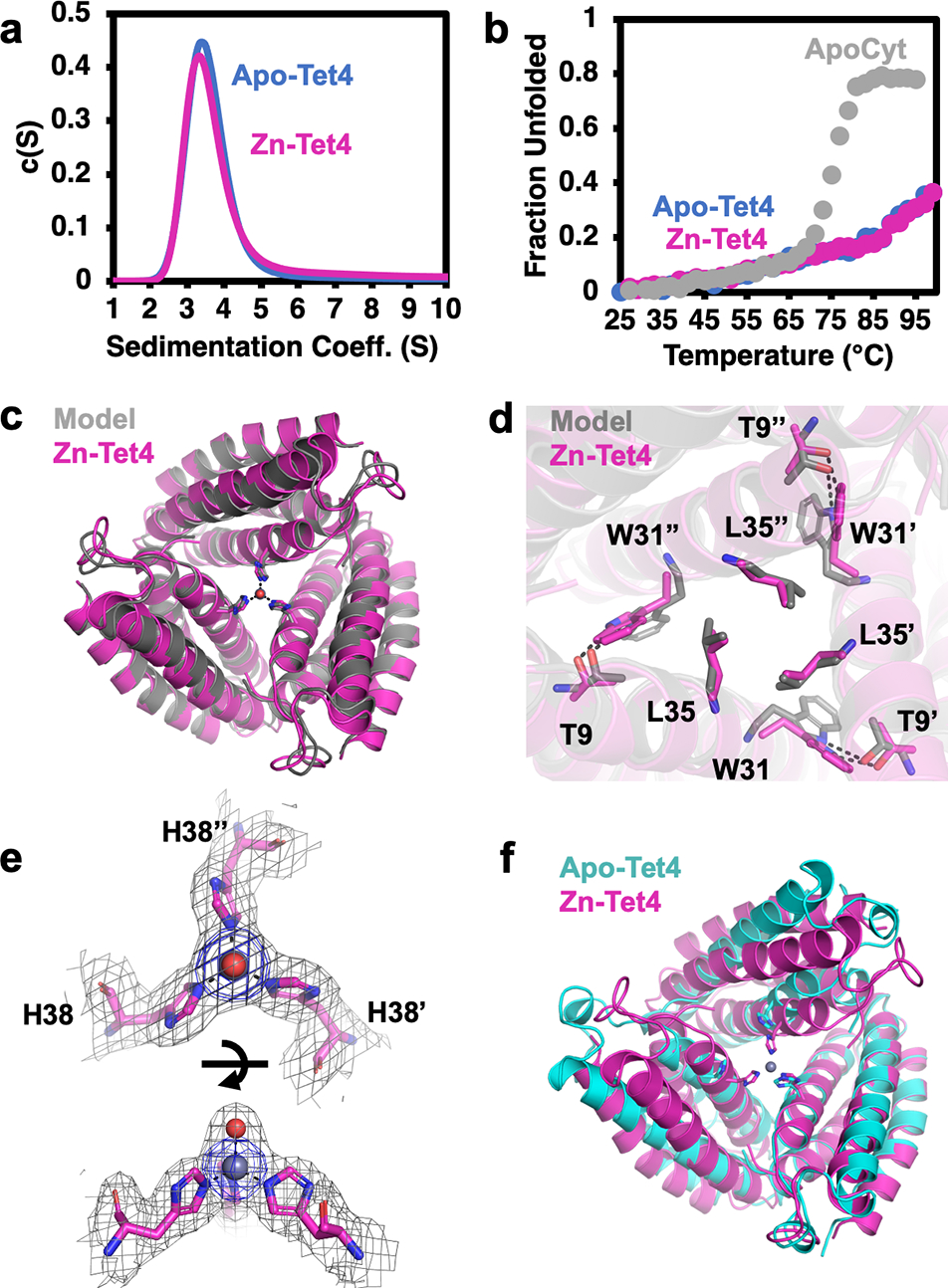

Figure 2.

(a) Analytical ultracentrifugation profiles of apo-Tet4 (blue) and Zn-Tet4 (magenta). (b) Thermal denaturation of apo-Tet4 (blue), Zn-Tet4 (magenta) and ApoCyt (grey). (c) Superposition of experimental (magenta) and designed (grey) structures of Zn-Tet4 (PDB: 8SJG), and (d) close-up views of engineered interfacial residues. (e) Views of the Zn-38His3 center (Zn – grey sphere, water – red sphere), along with 2Fo-Fc (grey mesh, 1.0σ) and Zn-anomalous maps (blue mesh, 5.0σ). (f) Superposition of Zn-Tet4 (magenta) and apo-Tet4 (cyan, PDB: 8SJF) structures.

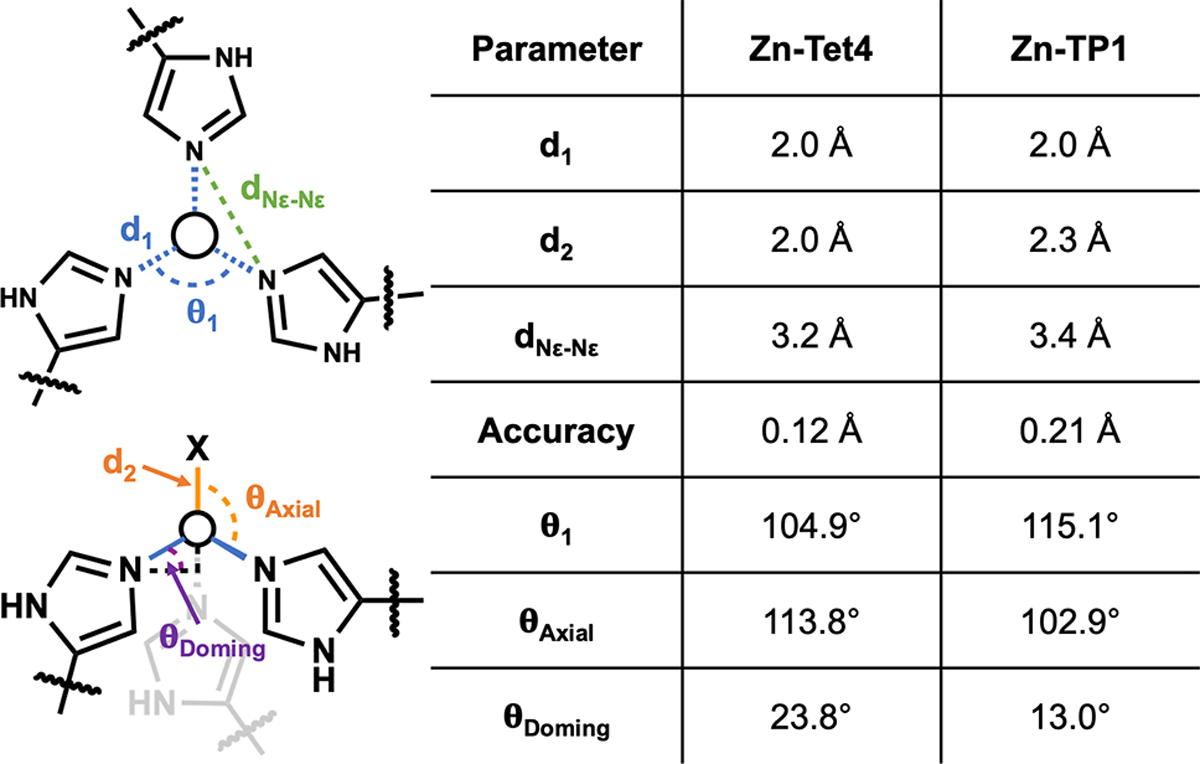

Tet4 displayed considerably improved thermal stability over ApoCyt, retaining nearly ~60% of its native α-helical structure at 100 °C (Figure 2b). We determined the crystal structures of Tet4 in the ZnII-bound and apo states at resolutions of 2.4 Å and 2.3 Å, respectively. The Zn-Tet4 structure was in excellent agreement with the designed model (αC-RMSD = 1.2 Å) (Figure 2c–d). Importantly, the Zn-38His3 center, which also included an axial aqua ligand, possessed a nearly ideal tetrahedral symmetry, with d1,avg = 2.0 Å and Θ1,avg = 104.9° (Figure 2e, Figure 3). Overall, the design accuracy of Zn-38His3 center (based on the deviation of His Nε atoms and Zn from target positions) was 0.12 Å. Apo-Tet4 adopted a more open trimeric arrangement compared to Zn-Tet4, whereby the αC distances between the 38His residues increased from 10.3 Å to 13.4 Å (Figure 2f). This metal-dependent shift was accommodated by the malleable hydrophobic interfaces between the monomers and indicated that the desired Zn-38His3 tetrahedral geometry was obtained despite the lack of rigid preorganization of the assembly (Figure S5).

Figure 3.

Geometric parameters for Zn-Tet4 and Zn-TP1 metal centers.

To further demonstrate the utility of our method, we next targeted a trigonal planar Zn-His3 center. In contrast to tetrahedral geometries, trigonal planar ZnII centers are rarely observed in proteins (Figure S6). In fact, in our search of the RCSB database,74 we could not find a metalloprotein with a trigonal planar His3-Zn motif, suggesting that this geometry may be thermodynamically less favorable. We therefore reasoned that a stringent test of our approach would be to design a preorganized ApoCyt assembly that would enforce a trigonal planar Zn-His3 coordination geometry, which would require an accuracy of ≤0.2 Å in the positions of His Nε atoms to discriminate between the two geometries (assuming d1 = 2.0 Å). Again using ApoCyt as our building block, we sampled the same set of geometric parameters as previously, except that Θ1 was set at 120°. This search resulted in a new set of docked trimer structures, from which we chose one for interface redesign. Of the five promising design candidates with low Rosetta scores, only one candidate, TP-1, had an αC-RMSD of <2.5 Å compared to the AlphaFold2 prediction (Figure S7) and was therefore chosen for experimental characterization.

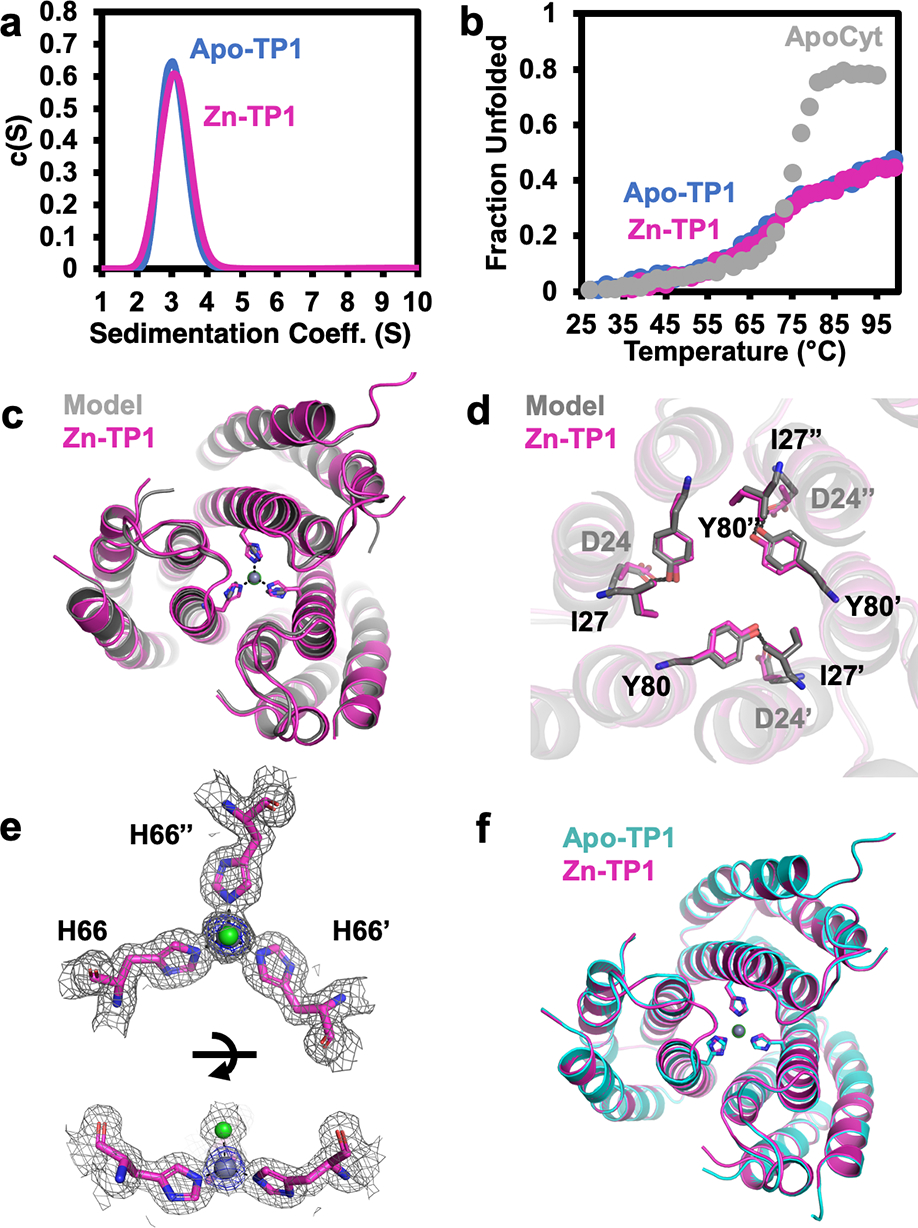

Like Tet4, TP1 formed a metal-independent trimer with high thermal stability (Figures 4a,b). TP1 also bound ZnII with high affinity (Kd = 62 nM), albeit >20-fold more weakly than Tet4 (Figure S8), affirming that the trigonal planar geometry was energetically less favorable. The 1.6-Å resolution crystal structure of Zn-bound TP1 aligned nearly perfectly with the design model (αC-RMSD = 0.9 Å) as well as with the 1.5-Å resolution crystal structure of apo-TP1 (αC-RMSD = 0.3 Å), with a design accuracy of 0.21 Å for the Zn-66His3 center (Figures 4c,d,f). The particularly close agreement between the apo- and Zn-bound TP1 structures pointed to a high level of preorganization, which indeed enforced a considerably more planar arrangement of the 66His3-Zn center in TP1 compared to the 38His3-Zn center in Tet4 as evidenced by: (1) an increase in Nε-Nε distances by 0.2 Å (while maintaining d1=2.0 Å), (2) a decrease in the “doming” angle (Θdoming) from 23.8° to 13.0°, and (3) an increase in Θ1 from 104.9° to 115.1° (Figures 3, 4e). The slight doming in 66His3-Zn was likely caused by an axial chloride ligand, yielding a distorted trigonal pyramidal geometry.

Figure 4.

(a) Analytical ultracentrifugation profiles of apo-TP1 (blue) and Zn-TP1 (magenta). (b) Thermal denaturation of apo-TP1 (blue), Zn-TP1 (magenta) and ApoCyt (grey). (c) Superposition of experimental (magenta) and designed (grey) structures of Zn-TP1 (PDB: 8SJH), and (d) close-up views of engineered interfacial residues. (e) Views of the Zn-66His3 center (Zn – grey sphere, chloride – green sphere), along with 2Fo-Fc (grey mesh, 1.0σ) and Zn-anomalous maps (blue mesh, 5.0σ). (f) Superposition of Zn-TP1 (magenta) and apo-TP1 (cyan, PDB: 8SJI) structures.

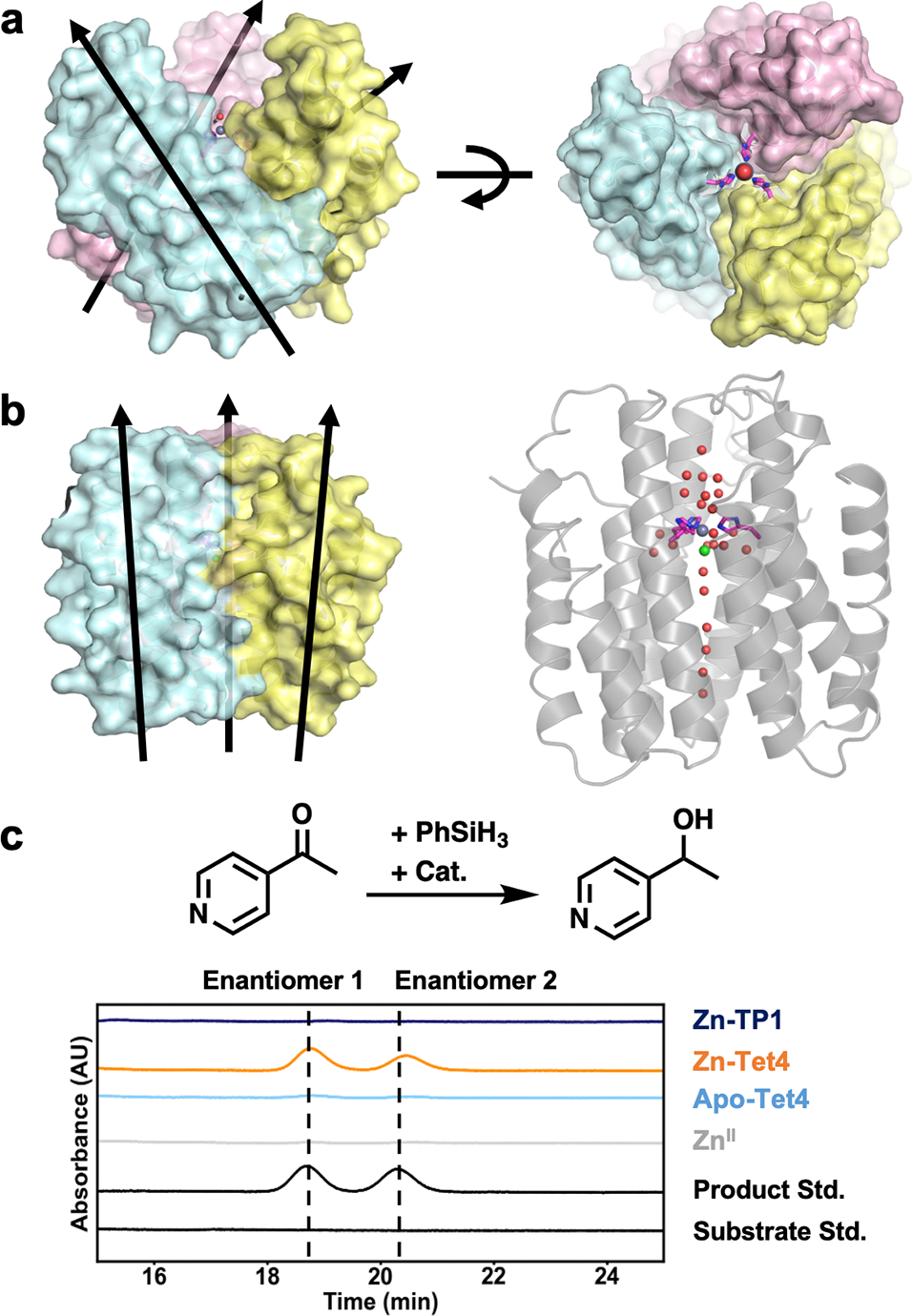

Although Tet4 and TP1 are both constructed from ApoCyt monomers, they use His residues which lie on different helices of ApoCyt for metal coordination, ultimately leading to different trimer arrangements. In Tet4, the monomers are tilted by ~31° from the C3 axis to give a conical shape, whereas in TP1 this value is ~11° to give a parallel arrangement (Figures 5a,b). Consequently, TP1 possesses larger intermonomer interfaces than Tet4 (1420 Å2 vs. 1230 Å2 per monomer), likely accounting for its greater structural pre-organization for ZnII binding, although differences in crystal packing interactions cannot be discounted. This arrangement of TP1 also results in a deeply buried Zn center, which is connected to the surface through a single file of water molecules within a hydrophobic tunnel formed along the C3 axis. This observation suggests that metal-templated design of helical structures may complement existing approaches for the design of selective ion/water channels.75–77 The conical arrangement of Tet1, in contrast, places the 38His3-Zn center in a surface-accessible position (Figure 5a, right), which we surmised could be used for a catalytic function. Inspired by recent work on carbonic anhydrase,78 we examined if Zn-Tet4 could catalyze the abiological reduction of ketones via a putative Zn-hydride species. Indeed, in the presence of a phenylsilane hydride donor, Zn-Tet4 reduced 4-acetylpyridine with turnover number (TON) of 97±1 and an enantiomeric excess (ee) of 18% (Figure 5c, Table S5) in 6 h. The latter finding indicates that the protein environment surrounding the 38His3-Zn center imposes some stereoselectivity despite its surface-exposed nature. As anticipated, Zn-TP1 was inactive for the same reaction due to the inaccessibility of its active site.

Figure 5.

(a) Orientation of ApoCyt monomers in ZnII-Tet4. (b) Orientation of ApoCyt monomers (left) and the central water channel in Zn-TP1. (c) The investigated hydride transfer reaction (top) and corresponding chiral-HPLC traces of relevant species. Reaction conditions were: 10 μmol substrate, 30 μmol phenylsilane, 0.01 μmol protein trimer and/or ZnCl2, incubated for 6 h at 20 °C.

In conclusion, we have reported here a new method to design proteins with predefined metal coordination geometries with atomic accuracy, bringing us closer to controlling protein-based metal reactivities with the facility demonstrated in synthetic inorganic and organometallic chemistry. This method is straightforward to implement, and its versatility is demonstrated by the facile access to two considerably different protein structures and metal environments from the same building block. Although these proof-of-principle studies focused on symmetric metal centers, we envision that our method can be readily adapted for designing asymmetric metal active sites constructed between disparate protein structural motifs, particularly if complemented by rapidly evolving machine-learning-based tools for protein design.53, 79–80

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM138884 (GRANT12948080). A.M.H was supported by the Molecular Biophysics Training Grant, NIH Grant T32-GM008326. Crystallographic data were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (supported by the DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences contract DE-AC02-76SF00515 and NIH P30-GM133894) and the Advanced Light Source (supported by the DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 and NIH P30-GM124169-01).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Supporting Methods; experimental characterization of tetrahedral metal center designs (Table S1); amino acid sequences of ApoCyt, Tet4, and TP1 (Table S2); crystallization conditions (Table S3); X-ray data collection and refinement statistics (Table S4); TON’s, ee’s, and time dependence for hydride-transfer catalysis (Table S5–S6); models of the six docking geometries obtained for the Zn-His3X metal center (Figure S1); Rosetta models and AlphaFold2 model alignments of Tet1-Tet7 (Figure S2); Zn-binding isotherms for Tet4 and Tet5 (Figure S3); AUC profiles of Tet2-Tet7 (Figure S4); Rosetta score evaluations of the crystal structures of apo and Zn-bound Tet4 and TP1 (Figure S5); the number of tetrahedral and trigonal planar coordination geometries per metal in the pdb (Figure S6); Rosetta model and AlphaFold2 model alignment of TP1 (Figure S7); Zn-binding isotherm for TP1 (Figure S8); HPLC standard curves of the hydride transfer substrate, 4-acetylpyridine, and product, 4-(1-hydroxyethyl)pyridine (Figure S9); Python3 scripts used to generate starting geometries for DFT calculations (Supporting Data 1), perform metal-directed protein docking (Supporting Data 2), and perform Rosetta interface design calculations (Supporting Data 3); and supporting references (PDF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Waldron KJ; Rutherford JC; Ford D; Robinson NJ, Metalloproteins and metal sensing. Nature 2009, 460, 823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang CJ, Searching for harmony in transition-metal signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkler JR; Gray HB, Electron Flow through Metalloproteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3369–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray HB; Winkler JR, Electron transfer in proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 537–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonini E; Brunori M, Hemoglobin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1970, 39, 977–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon EI; Heppner DE; Johnston EM; Ginsbach JW; Cirera J; Qayyum M; Kieber-Emmons MT; Kjaergaard CH; Hadt RG; Tian L, Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3659–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleifeld O; Frenkel A; Martin JM; Sagi I, Active site electronic structure and dynamics during metalloenzyme catalysis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreini C; Bertini I; Cavallaro G; Holliday GL; Thornton JM, Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 13, 1205–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon EI; Decker A; Lehnert N, Non-heme iron enzymes: contrasts to heme catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 3589–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon EI; Chen P; Metz M; Lee SK; Palmer AE, Oxygen binding, activation, and reduction to water by copper proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 4570–4590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchfield LA; George A; Tezcan FA, Repurposing proteins for new bioinorganic functions. Essays Biochem. 2017, 61, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchfield LA; Tezcan FA, Design and Construction of Functional Supramolecular Metalloprotein Assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalkley MJ; Mann SI; DeGrado WF, De novo metalloprotein design. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 31–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwizer F; Okamoto Y; Heinisch T; Gu YF; Pellizzoni MM; Lebrun V; Reuter R; Kohler V; Lewis JC; Ward TR, Artificial Metalloenzymes: Reaction Scope and Optimization Strategies. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 142–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis HJ; Ward TR, Artificial Metalloenzymes: Challenges and Opportunities. Acs Central Sci 2019, 5 (7), 1120–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook SA; Hill EA; Borovik AS, Lessons from Nature: A Bio-Inspired Approach to Molecular Design. Biochemistry-Us 2015, 54 (27), 4167–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm RH; Kennepohl P; Solomon EI, Structural and functional aspects of metal sites in biology. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2239–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudev T; Lim C, Metal binding affinity and selectivity in metalloproteins: insights from computational studies. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 97–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudev T; Lim C, Competition among Metal Ions for Protein Binding Sites: Determinants of Metal Ion Selectivity in Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 538–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kisgeropoulos EC; Griese JJ; Smith ZR; Branca RMM; Schneider CR; Hogbom M; Shafaat HS, Key Structural Motifs Balance Metal Binding and Oxidative Reactivity in a Heterobimetallic Mn/Fe Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5338–5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldron KJ; Robinson NJ, How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi TS; Tezcan FA, Overcoming universal restrictions on metal selectivity by protein design. Nature 2022, 603, 522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi TS; Tezcan FA, Design of a Flexible, Zn-Selective Protein Scaffold that Displays Anti-Irving-Williams Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 18090–18100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallee BL; Williams RJ, Metalloenzymes: the entatic nature of their active sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1968, 59, 498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross EL, Plastocyanin: Structure and function. Photosynth. Res. 1993, 37, 103–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu F; Cangelosi VM; Zastrow ML; Tegoni M; Plegaria JS; Tebo AG; Mocny CS; Ruckthong L; Qayyum H; Pecoraro VL, Protein design: toward functional metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3495–3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y; Yeung N; Sieracki N; Marshall NM, Design of functional metalloproteins. Nature 2009, 460, 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellinga HW; Richards FM, Construction of New Ligand-Binding Sites in Proteins of Known Structure: 1. Computer-Aided Modeling of Sites with Predefined Geometry. J Mol Biol 1991, 222, 763–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke ND; Yuan SM, Metal Search: A Computer Program That Helps Design Tetrahedral Metal-Binding Sites. Proteins 1995, 23, 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanghellini A; Jiang L; Wollacott AM; Cheng G; Meiler J; Althoff EA; Rothlisberger D; Baker D, New algorithms and an in silico benchmark for computational enzyme design. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 2785–2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen WA; Khare SD, Benchmarking a computational design method for the incorporation of metal ion-binding sites at symmetric protein interfaces. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1584–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardi A; Summa CM; Geremia S; Randaccio L; Pavone V; DeGrado WF, Retrostructural analysis of metalloproteins: Application to the design of a minimal model for diiron proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 6298–6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zastrow ML; Peacock AF; Stuckey JA; Pecoraro VL, Hydrolytic catalysis and structural stabilization in a designed metalloprotein. Nat. Chem. 2011, 4, 118–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibney BR; Mulholland SE; Rabanal F; Dutton PL, Ferredoxin and ferredoxin-heme maquettes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 15041–15046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan J; DeGrado WF, De novo design of catalytic proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 11566–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tegoni M; Yu FT; Bersellini M; Penner-Hahn JE; Pecoraro VL, Designing a functional type 2 copper center that has nitrite reductase activity within alpha-helical coiled coils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 21234–21239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh D; Lee KH; Demeler B; Pecoraro VL, Linear free-energy analysis of mercury(II) and cadmium(II) binding to three-stranded coiled coils. Biochemistry-Us 2005, 44, 10732–10740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faiella M; Andreozzi C; de Rosales RT; Pavone V; Maglio O; Nastri F; DeGrado WF; Lombardi A, An artificial di-iron oxo-protein with phenol oxidase activity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 882–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reig AJ; Pires MM; Snyder RA; Wu YB; Jo H; Kulp DW; Butch SE; Calhoun JR; Szyperski TA; Solomon EI; DeGrado WF, Alteration of the oxygen-dependent reactivity of de novo Due Ferri proteins. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4 (11), 900–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu F; Penner-Hahn JE; Pecoraro VL, De novo-designed metallopeptides with type 2 copper centers: modulation of reduction potentials and nitrite reductase activities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18096–18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watkins DW; Jenkins JMX; Grayson KJ; Wood N; Steventon JW; Le Vay KK; Goodwin MI; Mullen AS; Bailey HJ; Crump MP; MacMillan F; Mulholland AJ; Cameron G; Sessions RB; Mann S; Anderson JLR, Construction and in vivo assembly of a catalytically proficient and hyperthermostable de novo enzyme. Nat. Comm. 2017, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lombardi A; Marasco D; Maglio O; Di Costanzo L; Nastri F; Pavone V, Miniaturized metalloproteins: application to iron-sulfur proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2000, 97, 11922–11927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy ML; Gibney BR, Proton coupling to [4Fe-4S](2+/+) and [4Fe-4Se](2+/+) oxidation and reduction in a designed protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6826–6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nanda V; Rosenblatt MM; Osyczka A; Kono H; Getahun Z; Dutton PL; Saven JG; Degrado WF, De novo design of a redox-active minimal rubredoxin mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5804–5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JD; Pike DH; Tyryshkin AM; Swapna GVT; Raanan H; Montelione GT; Nanda V; Falkowski PG, Minimal Heterochiral de Novo Designed 4Fe-4S Binding Peptide Capable of Robust Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11210–11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahajan M; Bhattacharjya S, beta-Hairpin peptides: heme binding, catalysis, and structure in detergent micelles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6430–6434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee M; Wang T; Makhlynets OV; Wu Y; Polizzi NF; Wu H; Gosavi PM; Stohr J; Korendovych IV; DeGrado WF; Hong M, Zinc-binding structure of a catalytic amyloid from solid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 6191–6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Souza A; Bhattacharjya S, De Novo-Designed beta-Sheet Heme Proteins. Biochemistry-Us 2021, 60, 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mills JH; Sheffler W; Ener ME; Almhjell PJ; Oberdorfer G; Pereira JH; Parmeggiani F; Sankaran B; Zwart PH; Baker D, Computational design of a homotrimeric metalloprotein with a trisbipyridyl core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 15012–15017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Der BS; Machius M; Miley MJ; Mills JL; Szyperski T; Kuhlman B, Metal-Mediated Affinity and Orientation Specificity in a Computationally Designed Protein Homodimer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 375–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mills JH; Khare SD; Bolduc JM; Forouhar F; Mulligan VK; Lew S; Seetharaman J; Tong L; Stoddard BL; Baker D, Computational design of an unnatural amino acid dependent metalloprotein with atomic level accuracy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13393–13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou L; Bosscher M; Zhang C; Ozcubukcu S; Zhang L; Zhang W; Li CJ; Liu J; Jensen MP; Lai L; He C, A protein engineered to bind uranyl selectively and with femtomolar affinity. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J; Lisanza S; Juergens D; Tischer D; Watson JL; Castro KM; Ragotte R; Saragovi A; Milles LF; Baek M; Anishchenko I; Yang W; Hicks DR; Exposit M; Schlichthaerle T; Chun JH; Dauparas J; Bennett N; Wicky BIM; Muenks A; DiMaio F; Correia B; Ovchinnikov S; Baker D, Scaffolding protein functional sites using deep learning. Science 2022, 377, 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caldwell SJ; Haydon IC; Piperidou N; Huang PS; Bick MJ; Sjostrom HS; Hilvert D; Baker D; Zeymer C, Tight and specific lanthanide binding in a de novo TIM barrel with a large internal cavity designed by symmetric domain fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 30362–30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salgado EN; Faraone-Mennella J; Tezcan FA, Controlling protein-protein interactions through metal coordination: Assembly of a 16-helix bundle protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 13374–13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salgado EN; Lewis RA; Mossin S; Rheingold AL; Tezcan FA, Control of Protein Oligomerization Symmetry by Metal Coordination: C-2 and C-3 Symmetrical Assemblies through Cu-II and Ni-II Coordination. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 2726–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salgado EN; Radford RJ; Tezcan FA, Metal-Directed Protein Self-Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medina-Morales A; Perez A; Brodin JD; Tezcan FA, In Vitro and Cellular Self-Assembly of a Zn-Binding Protein Cryptand via Templated Disulfide Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12013–12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song WJ; Tezcan FA, A designed supramolecular protein assembly with in vivo enzymatic activity. Science 2014, 346, 1525–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Churchfield LA; Medina-Morales A; Brodin JD; Perez A; Tezcan FA, De Novo Design of an Allosteric Metalloprotein Assembly with Strained Disulfide Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13163–13166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rittle J; Field MJ; Green MT; Tezcan FA, An efficient, step-economical strategy for the design of functional metalloproteins. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kakkis A; Gagnon D; Esselborn J; Britt RD; Tezcan FA, Metal-Templated Design of Chemically Switchable Protein Assemblies with High-Affinity Coordination Sites. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21940–21944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brodin JD; Medina-Morales A; Ni T; Salgado EN; Ambroggio XI; Tezcan FA, Evolution of metal selectivity in templated protein interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8610–8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kakkis A; Golub E; Choi TS; Tezcan FA, Redox- and metal-directed structural diversification in designed metalloprotein assemblies. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 6958–6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eriksson AE; Jones TA; Liljas A, Refined Structure of Human Carbonic Anhydrase-II at 2.0-Å Resolution. Proteins 1988, 4, 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tripp BC; Smith K; Ferry JG, Carbonic anhydrase: new insights for an ancient enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 48615–48618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morgunova E; Tuuttila A; Bergmann U; Isupov M; Lindqvist Y; Schneider G; Tryggvason K, Structure of human pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2: activation mechanism revealed. Science 1999, 284, 1667–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lovejoy B; Cleasby A; Hassell AM; Longley K; Luther MA; Weigl D; McGeehan G; McElroy AB; Drewry D; Lambert MH; et al. , Structure of the catalytic domain of fibroblast collagenase complexed with an inhibitor. Science 1994, 263, 375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brinckerhoff CE; Matrisian LM, Timeline - Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffnagle AM; Eng VH; Markel U; Tezcan FA, Computationally Guided Redesign of a Heme-free Cytochrome with Native-like Structure and Stability. Biochemistry-Us 2022, 61, 2063–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Karlin S; Zhu ZY, Classification of mononuclear zinc metal sites in protein structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 14231–14236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leaver-Fay A; Tyka M; Lewis SM; Lange OF; Thompson J; Jacak R; Kaufman K; Renfrew PD; Smith CA; Sheffler W; Davis IW; Cooper S; Treuille A; Mandell DJ; Richter F; Ban YEA; Fleishman SJ; Corn JE; Kim DE; Lyskov S; Berrondo M; Mentzer S; Popovic Z; Havranek JJ; Karanicolas J; Das R; Meiler J; Kortemme T; Gray JJ; Kuhlman B; Baker D; Bradley P, Rosetta3: An Object-Oriented Software Suite for the Simulation and Design of Macromolecules. Meth. Enzymol. 2011, 487, 545–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Ronneberger O; Tunyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Zidek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl SAA; Ballard AJ; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior AW; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D, Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Putignano V; Rosato A; Banci L; Andreini C, MetalPDB in 2018: a database of metal sites in biological macromolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D459–D464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lear JD; Wasserman ZR; DeGrado WF, Synthetic amphiphilic peptide models for protein ion channels. Science 1988, 240, 1177–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mahendran KR; Niitsu A; Kong L; Thomson AR; Sessions RB; Woolfson DN; Bayley H, A monodisperse transmembrane alpha-helical peptide barrel. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scott AJ; Niitsu A; Kratochvil HT; Lang EJM; Sengel JT; Dawson WM; Mahendran KR; Mravic M; Thomson AR; Brady RL; Liu L; Mulholland AJ; Bayley H; DeGrado WF; Wallace MI; Woolfson DN, Constructing ion channels from water-soluble alpha-helical barrels. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 643–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ji PF; Park J; Gu Y; Clark DS; Hartwig JF, Abiotic reduction of ketones with silanes catalysed by carbonic anhydrase through an enzymatic zinc hydride. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dauparas J; Anishchenko I; Bennett N; Bai H; Ragotte RJ; Milles LF; Wicky BIM; Courbet A; de Haas RJ; Bethel N; Leung PJY; Huddy TF; Pellock S; Tischer D; Chan F; Koepnick B; Nguyen H; Kang A; Sankaran B; Bera AK; King NP; Baker D, Robust deep learning-based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watson JL; Juergens D; Bennett NR; Trippe BL; Yim J; Eisenach HE; Ahern W; Borst AJ; Ragotte RJ; Milles LF; Wicky BIM; Hanikel N; Pellock SJ; Courbet A; Sheffler W; Wang J; Venkatesh P; Sappington I; Torres SV; Lauko A; Bortoli VD; Mathieu E; Barzilay R; Jaakkola TS; DiMaio F; Baek M; Baker D, Broadly applicable and accurate protein design by integrating structure prediction networks and diffusion generative models. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.12.09.519842. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.