Abstract

A carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli strain C-SRM-3 was isolated from hospital wastewater effluent in Hangzhou city, China in March 2022. Analysis of the whole genome sequence showed that this blaNDM-13-positive strain belonged to an internationally recognized high-risk clone ST410 responsible for the dissemination of carbapenem resistance in E. coli. This isolate displayed a multidrug-resistant phenotype and carried a cassette of antibiotic-resistant genes. blaNDM-13 gene was successfully transferred to the recipient E. coli C600 via conjugation. WGS results revealed that blaNDM-13 gene was located on an IncI1 type plasmid replicon. The phylogenetic reconstruction showed that wastewater-sourced C-SRM-3 strain was located in a single branch, far removed from human-derived and animal-sourced isolates. The detection of blaNDM-13 in hospital wastewater suggests that continuous monitoring of antibiotic-resistant genes in the environment is critical for the prevention of carbapenem-resistant bacteria spreading.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11356-023-28193-6.

Keywords: blaNDM-13, Hospital wastewater, ST410 E. coli, Antibiotic resistance

Carbapenemase producing organisms (CPO) is a major threat to the global public health because these bacteria were resistant to almost all clinically available β-lactam antibiotics and therefore greatly limit the therapeutic options (Bonomo et al. 2018). New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) is one of the most common carbapenemases worldwide and was firstly discovered in 2009 (Yong et al. 2009). Up to now, more than twenty NDM variants have been identified in multiple bacterial species (Wu et al. 2019). NDM-13 contains two amino acid substitutions (D95N and M154L) compared with NDM-1, but the two NDM variants have similar enzymatic activity profiles towards β-lactams (Shrestha et al. 2015).

To our knowledge, blaNDM-13 has been reported from clinical samples in only three countries, including E. coli from urine in Nepal (Shrestha et al. 2015), E. coli from rectal swab sample in Korea (Kim et al. 2019), and E. coli and Salmonella Rissen isolated from urine and fecal sample in China (Huang et al. 2022; Lv et al. 2016). No report on the emergence of blaNDM-13 gene strains isolated from the environment has been published. Hospital wastewater is regarded as an emerging pollutant. Multidrug-resistant pathogens and residual antibiotics in hospital wastewater can enter into the water system in the broader environment and thus increase the potential risk of spreading resistance in aquatic environment (Hocquet et al. 2016). In this study, we described the molecular characterization of an NDM-13-producing E. coli obtained from hospital sewage in China.

The strain C-SRM-3 was isolated from the wastewater effluent of a tertiary comprehensive hospital in Hangzhou city, China in March 2022. Both NG-test CARBA5 and GeneXpert system confirmed the presence of NDM. Conjugation experiments were carried out using filter mating method, with rifamycin-resistant E. coli C600 strain as the recipient. The conjugants were randomly selected on Mueller–Hinton agar plates containing 600 µg/mL rifampicin and 2 µg/mL meropenem and then inoculated on the selective media Chinablue plates at 37 °C for 18 h. Based on the morphological distinction, the donor C-SRM-3 showed a blue phenotype on the Chinablue plate, while the recipient EC600 was red. Red clones were picked for further PCR assays and whole genome sequencing to verify the success of the horizontal transfer of blaNDM-13 gene. In our experiment, blaNDM-13 gene was successfully transferred to the recipient strain EC600.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of strain C-SRM-3 and its conjugant C-SRM-3JH were determined by the microbroth dilution method. The MICs of most antibiotics were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, and the results of tigecycline were interpreted based on EUCAST standards (Version 12.0, 2022). Isolate C-SRM-3 displayed phenotypic resistance to imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, cefmetazole, ceftazidime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime/avibactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam, but was susceptible to polymyxin B, tigecycline and amikacin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of strain C-SRM-3, conjugant C-SRM-3-JH and recipient EC600

| Antibiotics | Breakpoint for resistance (μg/ml) | C-SRM-3 | C-SRM-3-JH | EC600 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imipenem | ≥ 4 | 4 | 8 | ≤ 1 |

| Meropenem | ≥ 4 | 4 | 4 | ≤ 1 |

| Ertapenem | ≥ 2 | 8 | 8 | ≤ 2 |

| Cefmetazole | ≥ 64 | 64 | 16 | ≤ 2 |

| Ceftazidime | ≥ 16 | > 128 | > 128 | ≤ 2 |

| Cefotaxime | ≥ 4 | > 128 | 128 | ≤ 4 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | ≥ 128/4 | 256/128 | 128/4 | ≤ 8/4 |

| Cefoperazone/Sulbactam | ≥ 64/32 | > 256/128 | > 256/128 | ≤ 8/4 |

| Ceftazidime/Avibactam | ≥ 16/4 | > 64/4 | > 64/4 | ≤ 0.5/4 |

| Cefepime | ≥ 16 | 64 | 32 | ≤ 4 |

| Polymyxin B | ≥ 4 | 1 | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 0.5 |

| Tigecycline | ≥ 0.5 | ≤ 0.25 | ≤ 0.25 | ≤ 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≥ 1 | > 32 | ≤ 1 | ≤ 1 |

| Amikacin | ≥ 64 | ≤ 4 | ≤ 4 | ≤ 4 |

| Aztreonam | ≥ 16 | 128 | ≤ 4 | ≤ 4 |

Resistant phenotypes are bolded

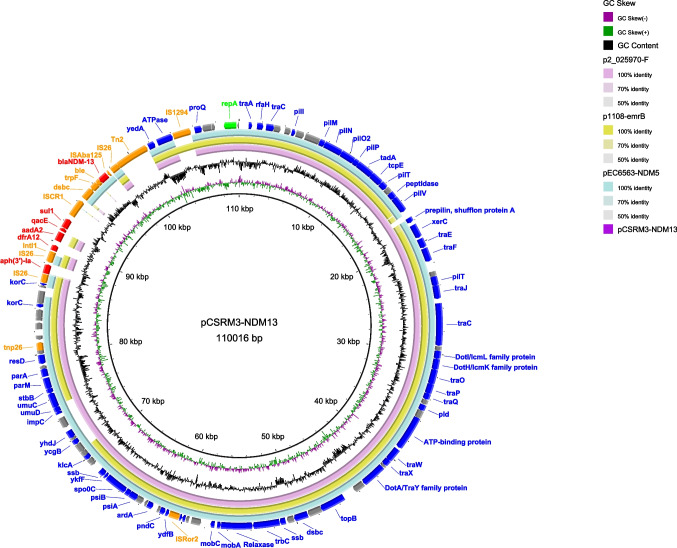

To characterize the molecular features of E. coli C-SRM-3, whole genome sequencing (WGS) was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 and Nanopore MinION (Oxford, UK) sequencing platforms. The short-read sequences were assembled using SPAdes v3.15.1. Hybrid assembly of both sequencing reads was constructed using Unicycler v.0.4.4. C-SRM-3 strain is 5.1 Mb in size. It consists of six circular DNA sequences, including a chromosome of 4,799,348 bp with 50.66% GC content, and five plasmids. The complete plasmid sequence was annotated via RAST Server (https://rast.nmpdr.org/) and edited manually. Circular maps of plasmids were plotted using the BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) tool (Alikhan et al. 2011). Further bioinformatics analysis was performed at the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (www.genomicepidemiology.org) with the bacteria pipeline (ResFinder version 4.1, PlasmidFinder version 2.1 and VirulenceFinder version 2.0). Insertion sequences (ISs) were identified by ISfinder (Siguier et al. 2006). In C-SRM-3, only three plasmids carried antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). blaNDM-13 gene, together with the aminoglycosides [aph(3’)-Ia, aadA2], sulphonamides (sul1), trimethoprim (dfrA12) and disinfectant resistance gene (qacE), was located on a 110 kb IncI1-I(Alpha) type plasmid, designated by pCSRM3-NDM13 (Fig. 1). This plasmid has been identified to be a mobile plasmid, and could be transferred into the recipient EC600 strain through conjugation, conferring resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents (Table 1). By BLASTN analysis, three plasmids showed > 80% coverage and > 99% identity with pCSRM3-NDM13, namely p2_025970-F (CP036181.1), pEC6563-NDM5 (CP095858.1) and p1108-emrB (MG825377.1). A circular comparison showed that these plasmids shared the same backbone region, but slight differences among surrounding regions of blaNDM-13 gene.

Fig. 1.

Comparative analysis of pSRM3-NDM13 (this study) with p2_025970-F (CP036181.1), pEC6563-NDM5 (CP095858.1) and p1108-emrB (MG825377.1) plasmids. The outermost circle in the figure represents the pSRM3-NDM13 sequence with gene annotations. In the outermost circle, the red arrows, orange arrows, green arrows, blue arrows and grey arrows indicate ARGs, mobile genetic elements, repA, other genes and hypothetical proteins, respectively

Then, the sequences of bacterial genome carrying blaNDM-13 were compared and visualized by EasyFig v.2.2.5. ΔISAba125-blaNDM-13-bleMBL-trpF was found in all sequences (Fig. S1). Various insertion sequences (IS) such as Tn2, IS26, ISCR1, IS1294, IS5, IS3000 were distributed at the upstream or downstream of that region, and probably related to the mobilization mechanism of blaNDM gene according to previous studies (Wu et al. 2019).

In addition, plasmid analysis revealed that there were also two plasmid harboring ARGs in C-SRM-3 strain, a 68 kb IncFIB/IncFIC(FII) type plasmid and a 113 kb IncFII/IncX1 type plasmid. The other two plasmids did not carry resistance genes. Based on the VirulenceFinder 2.0 database, virulence factors encoding adhesion and fimbrial attachment proteins (fimH, fdec), outer membrane protein (traT, iss, iucC), aerobactin system (iutA, iron, sitA) and colicin V (cvaC) were detected in this isolate.

Through the online comparison in PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org), we found that E. coli C-SRM-3 belonged to the sequence type 410 (ST410). Due to its multidrug resistance and high transmissibility, ST410 E. coli has been described as an emerging international high-risk clone in numerous studies (Nadimpalli et al. 2019; Roer et al. 2018; Schaufler et al. 2016). A global epidemiological survey revealed that ST410 was the most common clone among the carbapenemase-producing E. coli population (Peirano et al. 2022). Likewise, another nationwide surveillance of CRE strains in China showed that NDM enzymes were the most frequently reported carbapenemase types among carbapenem-resistant E. coli, and that ST410 was the second most common type of NDM-positive E. coli strains, after ST167 (Zhang et al. 2017).

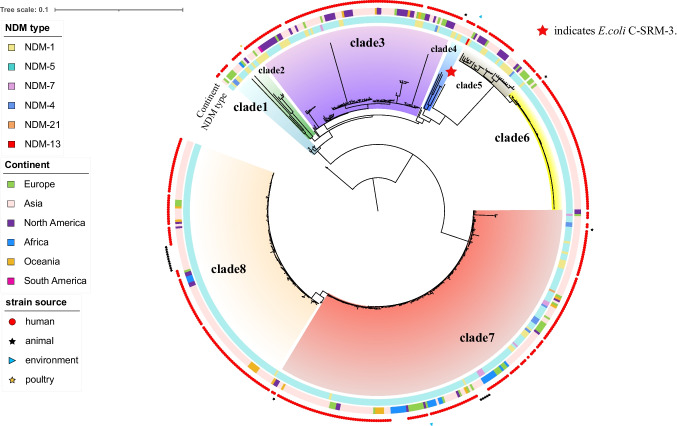

To place our sequenced E. coli C-SRM-3 isolate into a global context, a collection of isolates with the same species were selected from NCBI Pathogen Detection Database(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/isolates/#taxgroup_name:%22E.coli%20and%20Shigella%22, accessed on 27 March 2023) and a total of 1773 ST410-E. coli genomes were identified using the Achtman seven gene MLST scheme as a query. We picked 538 ST410-E. coli genomes carrying blaNDM genes and performed phylogenetic analysis of the ST410 lineage based on core-genome alignment using Parsnp v1.2 (Treangen et al. 2014) (Table S1). Notably, the global collection of blaNDM-positive ST410 lineages was predominantly portrayed by human-derived isolates, and to a lesser extent, by animal-sourced isolates and environmental isolates. The phylogenetic reconstruction showed that 538 ST410 isolates can be roughly divided into two clades and eight sub-clades (Fig. 2). Isolate C-SRM-3 was obtained from hospital wastewater. It was located in a single branch, with long distance from human and animal-sourced isolates. According to SNP analysis, the most closely related to C-SRM-3 was the isolate GCA_014117745.2, recovered from human urine-sourced in Thailand in Asia (537 SNPs differences) (Table S2). In terms of geography, blaNDM-ST410 E. coli strains were widely distributed and have been detected in 31 counties across six continents. Additionally, some strains from sub-cluster have a geographical preference, for example isolates prevailing in the American continent were mostly distributed in clade 3 and clade5, while isolates from Africa were mainly distributed in clade 7.

Fig. 2.

Phylogeny of blaNDM-positive ST410 E. coli genomes (n = 538) based on SNP alignment. Red star indicates E. coli C-SRM-3

Among the 235964 E. coli assembled genomes, only 5203 data were identified as blaNDM-positive through AMR genotypes search, with a positive rate of 2.20%. However, 547 strains were screened for blaNDM-positive from 1773 ST410 E. coli strains, and the positive rate was 30.85%, which was significantly higher than the average level. It indicates that ST410 E. coli served as the major host of blaNDM-positive E. coli, and its clone spread may contribute to the prevalence of blaNDM gene among E. coli strains. Moreover, the higher positive rate suggests that infections caused by ST410 E. coli will be more challenging and other potent antibiotics such as polymyxin and tigecycline should be taken into account in clinical treatment. Figure 2 revealed that six NDM variants had been detected in ST410 E. coli, with NDM-5 being the majority and NDM-1, NDM-4, NDM-7, NDM-21 being a small proportion. The presence of blaNDM-13 in the ST410 E. coli further confirmed the spread of high-risk clone ST410 group in environment.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of blaNDM-13-positive bacteria isolated from hospital wastewater. Hospital wastewater served as a persistent reservoir of pathogens as well as ARGs, and played a crucial role in spreading resistance in the aquatic environment (Zhang et al. 2020). More importantly, high concentrations of antibiotics in the water are recognized as a significant contributor to the horizontal transfer of resistant plasmids, which leads to an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistant bacteria (Hocquet et al. 2016). Our study provided an insight into the genomic features of high-risk clone ST410 E. coli isolate with the blaNDM-13 from hospital wastewater and highlighted the need to have continuous monitoring of environmental contamination with ARGs. Meanwhile, our study highlighted that proper disposal of hospital wastewater is critical in the prevention of the spreading of carbapenem-resistant bacteria in the environment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xiaoyang Ju, Yuchen Wu and Gongxiang Chen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xiaoyang Ju and revised by Rong Zhang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82072341, 81871705) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFD1800400).

Data availability

The complete sequences of E. coli C-SRM-3 were deposited in the NCBI database with accession numbers CP123195, CP123196, CP123197, CP123198, CP123199, and CP123200 under the BioSample accession SAMN32472040.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J, Limbago BM, Poirel L, Segre JA, Westblade LF. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Clin Infect Dis: an Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;66:1290–1297. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocquet D, Muller A, Bertrand X. What happens in hospitals does not stay in hospitals: antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospital wastewater systems. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Ma X, Zeng S, Fu L, Xu H, Li X. Emergence of a Salmonella Rissen ST469 clinical isolate carrying bla (NDM-13) in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:936649. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.936649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Jin YH, Park SH, Han S, Kim HS, Park JH, Gong Y, An JH, Jung SW, Kim S, Kim J, Kim DW, Hong CK, Lee JH, Kim IY, Jung K. Emergence of a multidrug-resistant clinical isolate of Escherichia coli ST8499 strain producing NDM-13 carbapenemase in the Republic of Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;94:410–412. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J, Qi X, Zhang D, Zheng Z, Chen Y, Guo Y, Wang S, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Tang YW, Chen Z, Hu L, Wang L, Yu F. First report of complete sequence of a bla(NDM-13)-harboring plasmid from an Escherichia coli ST5138 clinical isolate. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:130. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadimpalli ML, de Lauzanne A, Phe T, Borand L, Jacobs J, Fabre L, Naas T, Le Hello S, Stegger M. Escherichia coli ST410 among humans and the environment in Southeast Asia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;54:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirano G, Chen L, Nobrega D, Finn TJ, Kreiswirth BN, DeVinney R, Pitout JDD. Genomic epidemiology of global carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli, 2015–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:924–931. doi: 10.3201/eid2805.212535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roer L, Overballe-Petersen S, Hansen F, Schønning K, Wang M, Røder BL, Hansen DS, Justesen US, Andersen LP, Fulgsang-Damgaard D, Hopkins KL, Woodford N, Falgenhauer L, Chakraborty T, Samuelsen Ø, Sjöström K, Johannesen TB, Ng K, Nielsen J, Ethelberg S, Stegger M, Hammerum AM, Hasman H (2018) Escherichia coli sequence type 410 is causing new international high-risk clones. MSphere. 3(4):e00337-18. 10.1128/mSphere.00337-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schaufler K, Semmler T, Wieler LH, Wohrmann M, Baddam R, Ahmed N, Muller K, Kola A, Fruth A, Ewers C, Guenther S (2016) Clonal spread and interspecies transmission of clinically relevant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli of ST410--another successful pandemic clone? FEMS Microbiol Ecol 92. 10.1093/femsec/fiv155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shrestha B, Tada T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Shimada K, Ohara H, Kirikae T, Pokhrel BM. Identification of a novel NDM variant, NDM-13, from a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolate in Nepal. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5847–5850. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00332-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Feng Y, Tang G, Qiao F, McNally A, Zong Z (2019) NDM Metallo-beta-Lactamases and their bacterial producers in health care settings. Clin Microbiol Rev 32. 10.1128/cmr.00115-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, Walsh TR. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5046–5054. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Liu L, Zhou H, Chan EW, Li J, Fang Y, Li Y, Liao K, Chen S. Nationwide surveillance of clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in China. EBioMedicine. 2017;19:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Huang J, Zhao Z, Cao Y, Li B. Hospital wastewater as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2020;8:574968. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete sequences of E. coli C-SRM-3 were deposited in the NCBI database with accession numbers CP123195, CP123196, CP123197, CP123198, CP123199, and CP123200 under the BioSample accession SAMN32472040.