Abstract

In mammals, interleukin (IL)-17 cytokines are produced by innate and adaptive lymphocytes. However, the IL-17 family has widespread expression throughout evolution, dating as far back as cnidaria, molluscs and worms, which predate lymphocytes. The evolutionary conservation of IL-17 suggests that it is involved in innate defence strategies, but also that this cytokine family has a fundamental role beyond typical host defence. Throughout evolution, IL-17 seems to have a major function in homeostatic maintenance at barrier sites. Most recently, a pivotal role has been identified for IL-17 in regulating cellular metabolism, neuroimmunology and tissue physiology, particularly in adipose tissue. Here we review the emerging role of IL-17 signalling in regulating metabolic processes, which may shine a light on the evolutionary role of IL-17 beyond typical immune responses. We propose that IL-17 helps to coordinate the cross-talk among the nervous, endocrine and immune systems for whole-body energy homeostasis as a key player in neuroimmunometabolism.

Emerging roles of IL-17 signalling

The IL-17 family of cytokines have been clearly demonstrated to play a critical role in barrier defence since their discovery 30 years ago. IL-17 cytokines not only are key players against bacterial and fungal infections but also are established as mediators of autoimmunity. However, outside their classic role in host defence against pathogens, the physiological role of homeostatic IL-17 is becoming increasingly recognized. At the same time, the frequency of aberrant IL-17A expression in pathological conditions is becoming more clear. Indeed, other roles for IL-17A have recently been described beyond its function as a pro-inflammatory molecule in the regulation of energy homeostasis1,2, embryonic development3, short-term memory4 and anxiety behaviour5. Overexpression of IL-17A can contribute to the development of diseases not typically associated with autoimmunity, such as obesity and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)6,7. Canonical IL-17 signalling has a Goldi-locks effect on the host; lack of IL-17 causes susceptibility to severe bacterial and fungal infections, but increased IL-17 is associated with autoimmunity. However, another side of IL-17 has emerged, which also appears to have a Goldilocks effect; increased IL-17 signalling affects the behaviour of mice, whereas lack of IL-17 affects the host’s ability to sense changes in the external environment. These findings highlight the non-canonical roles of IL-17, possibly involving a neuroimmune axis.

Here, we aim to link the classical view of IL-17 in central nervous system (CNS) autoimmunity and defence against bacteria and fungi with clues from its role throughout evolution in organisms lacking immune cells (Fig. 1). In these ancient organisms, IL-17 appears to be predominantly involved in host defence but using defence mechanisms via the nervous, digestive and metabolic systems. Thus, we propose that the function of IL-17 and its ancient orthologues 600 million years ago was primarily as a metabolic messenger, coordinating metabolism in collaboration with the nervous system for host defence.

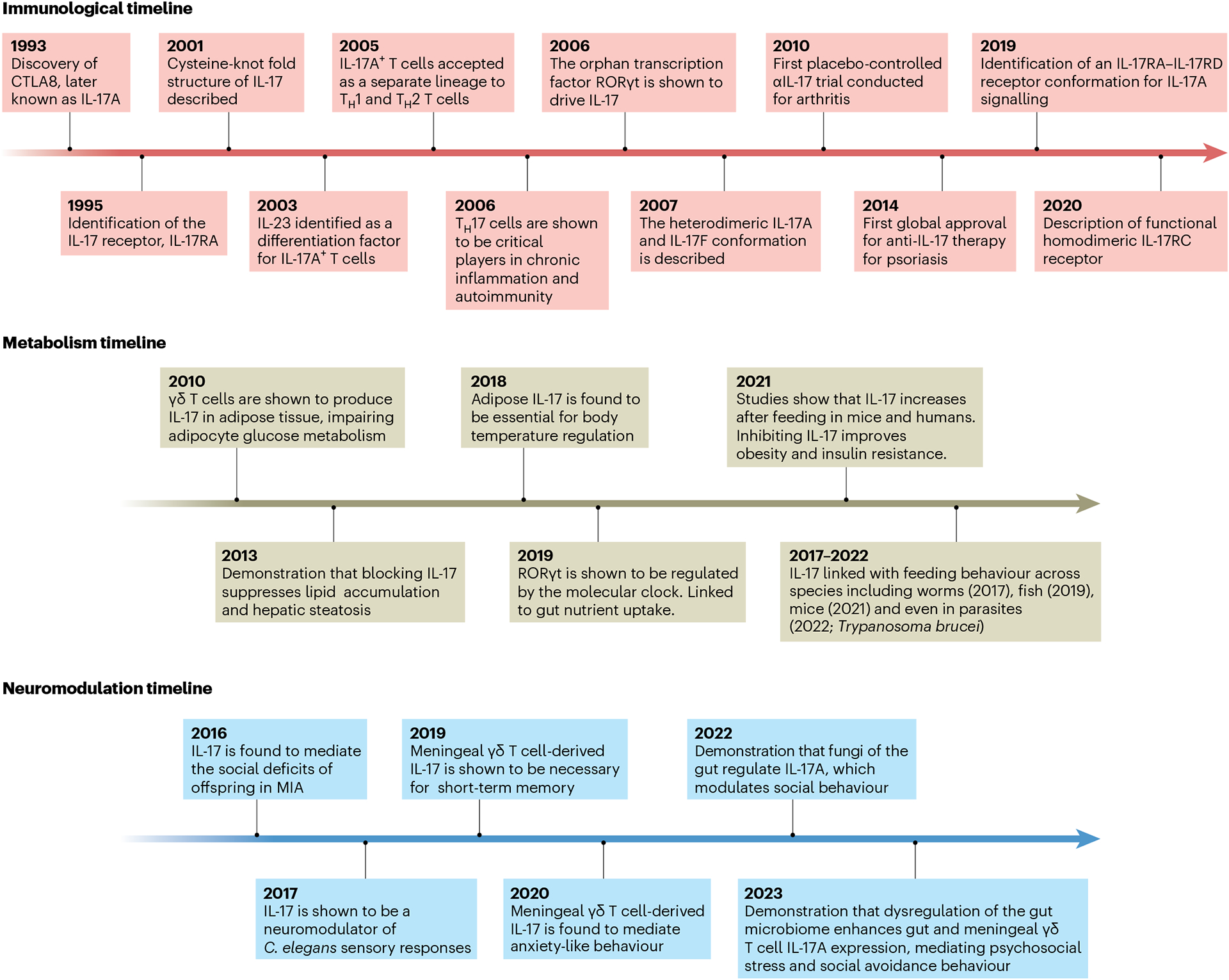

Fig. 1 |. Timeline of major neuroimmunometabolic discoveries involving IL-17.

Since the discovery of IL-17A in 1993, our understanding of the role of this proinflammatory cytokine has slowly become more focused towards metabolism (immunological timeline). The first indication that IL-17 regulates systemic metabolism was observed when mice deficient for IL-17 displayed enhanced glucose handling (2010; metabolism timeline). Subsequent studies have also described a neuromodulatory role for IL-17 in which it regulates behavioural expression in C. elegans and mice (neuromodulation timeline).

The discovery of the IL-17 cytokine family

In 1993, the founding member of the IL-17 family of cytokines, first named cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 8 (CTLA8), and later known as IL-17A, was identified and mapped to the mouse and human genomes8. Subsequent screening for IL-17A homologues revealed five structurally similar proteins, which were designated IL-17B through to IL-17F9 (Fig. 1). The first receptor for IL-17A, IL-17R, was discovered 2 years later when it was observed that IL-17A could elicit IL-6 secretion from fibroblasts10. Multiple receptors for IL-17 were subsequently identified, the first being IL-17RA, followed by four additional receptors named IL-17RB through to IL-17RE11. Interest in the IL-17 cytokine family accelerated almost a decade after their discovery when early papers suggested that IL-17A was produced by a novel subset of helper T cells, which later became known as TH17 cells12 (Fig. 1). These findings challenged the existing paradigm of T cells being either TH1 or TH2 cells, as postulated by Coffman and Mosmann in 1986 (ref. 13). Several seminal discoveries followed; the Gurney laboratory demonstrated that IL-23 promoted the development of a distinct population of CD4+ helper T cells expressing IL-17 (ref. 14). Shortly thereafter, the Cua laboratory discovered that IL-23 signalling promoted the expression of IL-17A from CD4+ TH17 cells, which were pathogenic in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the experimental model of multiple sclerosis15. Subsequently, the Stockinger, Kuchroo and Weaver laboratories found that a combination of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-6 drove differentiation of TH17 cells, whereas IL-23 was important for their maintenance16–18. Furthermore, the cytokine IL-1β plays an indispensable role in the differentiation and activation of TH17 cells, particularly in autoimmune disease development19. In 2006, Littman and Cua discovered that the orphan transcription factor, RORγt, was the driver of the TH17 lineage (Fig. 1)20. Since then, IL-17 has been shown to be a key player in the mouse and human immune systems and to be vital for host defence against extracellular bacterial and fungal infections21,22.

IL-17 signal transduction

Extracellular.

IL-17A and IL-17F are the best-characterized members of the IL-17 cytokine family, sharing the closest structural homology. IL-17A and IL-17F function as homodimers or form IL-17A–IL-17F heterodimers23. The different IL-17A–IL-17F dimeric conformations signal through the same receptor complex, which is an IL-17RA and IL-17RC heterodimer24. However, it has been suggested that IL-17A homodimers have a higher affinity for the IL-17RA subunit, while IL-17F homodimers have a higher affinity for IL-17RC. There is also evidence for IL-17RC homodimeric receptor complexes. The downstream signalling from IL-17RC homodimers, independent of IL-17RA, has not been elucidated, although this complex may induce IL-33 (Fig. 2)25. Additionally, IL-17A homodimers may signal through an alternate receptor complex consisting of IL-17RA and IL-17RD subunits26. Recent evidence indicates functional sharing of the IL-17RA receptor, as IL-17E (also known as IL-25) signals through a receptor conformation consisting of IL-17RB and IL-17RA27.

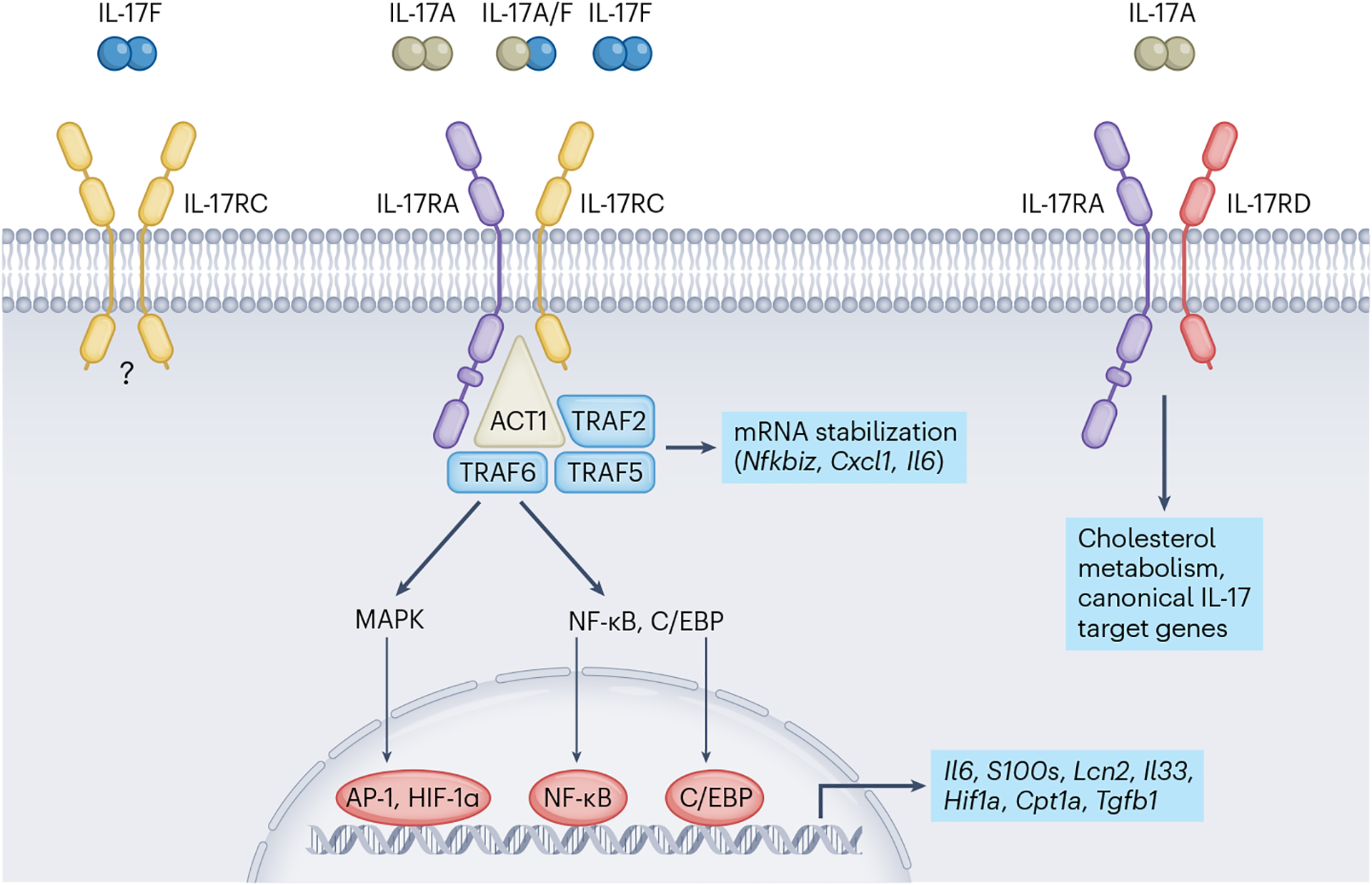

Fig. 2 |. IL-17-mediated signalling in target cells.

IL-17A and IL-17F initiate downstream signalling events by ligating receptor complexes composed of IL-17RA and IL-17RC. Following ligation, IL-17RA–IL-17RC recruits the adaptor protein ACT1, an essential member of the cytosolic IL-17 cascade. ACT1 in turn associates with members of the TRAF family of adaptor proteins, activating multiple transcription factors that direct inflammation, cellular metabolism and tissue repair. Additionally, IL-17 signals through TRAF2 and TRAF5 to stabilize specific mRNA targets.

Intracellular.

The IL-17 receptors are structurally and functionally distinct from other cytokine receptors. IL-17Rs are categorized by a conserved cytoplasmic motif known as the ‘similar expression of fibroblast growth factor and IL-17 receptor’ or SEFIR domain, which is similar in structure to the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain found in Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and IL-1 receptors28. Furthermore, IL-17 cytokines do not signal through the JAK–STAT pathway like signature TH1 or TH2 cytokines in the adaptive immune system. The primary step in IL-17R signal transduction is the recruitment of NF-κB activator 1 (ACT1), which displays E3 ubiquitin ligase activity29. ACT1 is an essential component of IL-17 receptor signal transduction, as loss of ACT1 in mice mimics the phenotype of mice lacking IL-17RA30. Following IL-17A binding, ACT1 recruits and ubiquitinates tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which triggers IκB kinase (IKK) activation and degrades IκBα, ultimately activating the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)31. In addition to increased NF-κB activity, TRAF6 promotes the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) intracellular pathway, which upregulates expression of the pro-inflammatory transcription factors activator protein 1 (AP-1), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein delta32 (C/EBPδ; Fig. 2). Together, NF-κB, AP-1, C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ enhance the expression of IL-17A and IL-17F target genes. IL-17A-mediated activation of NF-κB also induces negative feedback loops that regulate NF-κB activity, which includes deubiquitinating enzymes, to end the intracellular signalling cascade33. One such negative feedback loop consists of IL-17R-dependent upregulation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IKKε, which phosphorylate ACT1, resulting in TRAF6 release, which inhibits IL-17 signal transduction34.

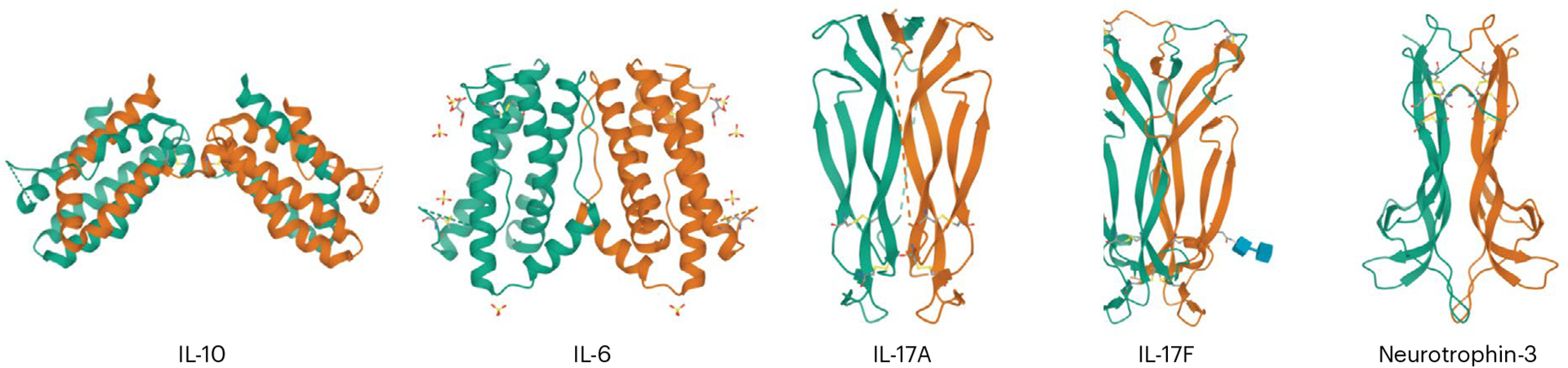

In addition to the structure of IL-17R, IL-17 cytokines themselves have unusual features. When IL-17A was initially discovered, it wasn’t considered a cytokine owing to its unusual amino acid sequence. The molecular structure of IL-17F displays a cysteine-knot fold that is similar to the structures of nerve growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor, unlike other cytokines35 (Fig. 3). The unusual structure and innate signalling pathways associated with IL-17 may be better understood outside adaptive immunity. In addition to adaptive TH17 cells, IL-17 is also expressed by subsets of innate lymphocytes including type-3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s), invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT cells), mucosal-associated invariant T cells (MAITs) and γδ T cells. Innate lymphocytes are mainly tissue-resident cells9,36 and rapidly respond to stimuli in minutes rather than days, like adaptive T cells. Furthermore, innate T cells do not recognize peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex molecules; rather, iNKT cells recognize lipids presented by CD1d, and MAIT cells recognize metabolites presented by MR1. Cognate antigens recognized by the γδTCR have remained elusive, but recent work suggests that γδ T cells sense stress molecules during homeostasis and in response to damage or injury. Each innate T cell subset contains an IL-17-producing population (NKT-17, MAIT-17 and γδ17). Understanding the role of IL-17 in the context of innate T cells and ILCs might aid our discovery of other non-canonical cytokine actions of IL-17.

Fig. 3 |. Structural relationships between IL-17A, IL-17F and an archetypal neurotrophic factor.

At the level of their 3D protein structures, IL-17A and IL-17F resemble neuronal growth factors, each adopting a similar β-sheet framework and the characteristic cystine knot motif of neurotrophins. Conversely, IL-17 cytokines are structurally distinct from prototypical interleukins, including IL-10 and IL-6.

Canonical IL-17 signalling

IL-17 is produced by innate and adaptive sources during homeostasis, injury, hypoxia and infection. IL-17 largely acts synergistically with other cytokines, including TNF and interferon-γ, which may fine-tune the intracellular signalling of IL-17A on target cells to context-specific cues36–38. T cells can be induced to make IL-17 via stimulation of the T cell antigen receptor, especially in conjunction with other cytokines such as IL-1β or IL-23 (ref. 39), or regulated by commensal bacteria of the gut microbiota to express transient IL-17A. Therefore, the activation state of an IL-17A-producing cell and the tissue microenvironment may also contextualize the role of IL-17A in homeostasis and defence against pathogens.

Bacterial immunity.

IL-17 signalling plays a fundamental role in host defence, particularly against bacterial infection. Naive helper T cells can be differentiated into effector TH17 cells in response to bacterial infection40. Microbial peptides from pathogens such as Bordetella pertussis and Salmonella typhimurium stimulate pattern recognition receptors on antigen-presenting cells, which induces IL-23 production and enhances TH17 differentiation40. Mice lacking IL-17A or IL-17RA expression show increased susceptibility to S. typhimurium and Klebsiella pneumonia infections41,42. IL-17C expression by non-immune cells such as colonic epithelial cells induces antimicrobial peptide production, conferring protection against Citrobacter rodentium infection in the gastrointestinal tract43. In humans, IL-17 is increased during infection of the stomach lining and is crucial for neutrophil recruitment during Helicobactor pylori infection44. Thus, IL-17 plays a well-established role in host defence against bacteria.

Fungal immunity.

IL-17 also plays a well-defined role in protection against pathogenic fungi. Patients undergoing monoclonal antibody treatment against IL-17 for autoimmune diseases commonly present with fungal and upper respiratory tract infections45. Treatment with bimekizumab, which neutralizes IL-17A and IL-17F, results in higher rates of oral candidiasis46. Furthermore, inherited deficiencies in human IL-17RA expression or genetic mutations in ACT1 lead to increased susceptibility to candidiasis infections in the oral mucosa and skin47–49. These findings emphasize the importance of IL-17 in fungal host defence and homeostatic maintenance, as Candida albicans is normally a non-pathogenic commensal microorganism.

Viral and parasite immunity.

Although host defence against viral or parasitic infection is typically more associated with a TH1 or TH2 immune response, respectively, evidence also shows a necessity for IL-17 against these pathogens. For example, IL-17A signalling from TH17 cells in the gut is enhanced in response to viral antigens such as Poly(I:C)3. In particular, viral infection with influenza virus in mice induces a population of IL-17-expressing CD8+ T cells in the lung50. Patients infected with influenza virus show a negative correlation between γδ17 T cell number in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and severity of influenza virus-associated pneumonia, demonstrating an important role for IL-17 against viral infection51. However, the role of IL-17 against parasitic infection is less clear. IL-17 signalling plays a protective role against single-celled parasitic infections such as the protozoan Trypanosma cruzi, but does not appear to play a crucial role against multicellular parasites45,52.

Commensal microorganisms.

In contrast to its role in host defence against pathogens, IL-17 expression is regulated by commensal microorganisms in the gut, skin and airways. Commensal microbeota, particularly segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), contribute to the differentiation and regulation of gut IL-17A-producing cells53. Germ-free mice lack TH17 cells in the gastrointestinal tract, but these can be repopulated following colonization with conventional microbiota54. IL-17 signalling also maintains commensal microorganisms in an organ-specific manner, as loss of IL-17 signalling leads to a loss of diversity and richness of the nasopharyngeal microbiota55. Furthermore, C57BL/6 mice purchased from different commercial vendors show differences in gut TH17 cell numbers54. Accumulation of TH17 cells by the gut microbiota has been implicated in the development of EAE, with antibiotic treatment ameliorating EAE disease onset56,57. Dysregulation of the lung microbiota is sufficient to expand the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes, which promotes IL-17B expression driving lung fibrosis58.

Together, these studies demonstrate the crucial role of IL-17 signalling in host defence against bacterial, fungal and viral infection, while highlighting the homeostatic interplay between the microbiota and IL-17 in tissue homeostasis and immunity. However, new findings suggest that a more complex interplay exists between the microbiome and IL-17 signalling, which causes changes to the behavioural expression of an organism with or without infection through a gut–brain axis59.

IL-17 in neuroimmunology

Research into the gut–brain axis has revealed that the gut microbeome influences complex behaviours such as sociability60, anxiety5 and depression61. Additionally, emerging studies indicate a neuroimmune role for IL-17 in the gut–brain axis. The Iliev laboratory has demonstrated that mucosa-associated fungi elicit IL-22 and IL-17A expression from gut TH17 cells, promoting social behaviour via IL-17A signalling60. This finding supported an earlier study showing that enhanced IL-17A production could rescue social deficits62. Moreover, reduction of Lactobacillus in the gut mediates psychosocial stress in mice, which causes social-avoidance behaviour. The reduction in gut Lactobacillus increased proportions of gut and meningeal γδ T cells, which mediated social-avoidance behaviour through production of IL-17A61. Further links with IL-17 and the brain came from the Kipnis laboratory, which showed that meningeal γδ T cells produce IL-17, which acts on cortical glutamatergic neurons and thereby regulates anxiety-like behaviour5. These findings highlight a gut–brain IL-17 axis that influences complex behaviours, although the exact underlying mechanism is still unclear.

The immune–nervous system interaction is bidirectional, with neurons influencing cytokine expression, and cytokines acting as neuromodulators for neuronal excitability. In the skin, IL-17A expression is modulated by nociceptive (TRPV1+Nav1.8+) neurons indirectly via IL-23 production by dendritic cells, or directly by CGRP release63,64. Additionally, IL-17A signalling by skin commensal-specific TH17 cells promotes peripheral sensory neuron regeneration after injury65. Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans demonstrated that IL-17 acts directly on neurons, influencing oxygen sensing to promote worm aggregation and escape from high oxygen levels66. Since then, many studies have confirmed a neuromodulatory role for IL-17, enhancing neuronal excitability and regulating synaptic transmission4,5,67. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that IL-17 acts as a neuromodulator that can alter behaviour. Perhaps IL-17 coordinates behavioural changes in collaboration with the metabolic system, particularly for energetically expensive behaviours such as anxiety, which activates the fight or flight system in preparation for danger. However, the connection between the roles of IL-17 in metabolism and neuromodulation remains to be fully explored.

Neuroimmunometabolic regulation by IL-17

There is evidence that metabolism plays a central role in the emerging connection between IL-17 signalling and gastrointestinal–nervous system cross-talk. The metabolic targets of IL-17 will be discussed later. Here, we explore the evidence linking IL-17 to metabolism and the CNS, which may be relevant to various neuroimmune pathways.

Maternal immune activation.

Recent evidence demonstrates the pivotal role of IL-17 signalling in the development of autism-like behaviour. Although classically considered a neurological disorder, recent evidence suggests a complex interplay between immune activation, metabolic disruption and neurological development in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Viral infection during pregnancy has been linked to increased frequency of ASD in offspring68. In mouse models of maternal immune activation (MIA), viral infection during pregnancy leads to social deficits and repetitive behaviours similar to ASD in the offspring, caused by elevated maternal IL-17A expression3. Subsequent studies demonstrated that poly(I:C)-induced maternal IL-17A was driven by SFB in the gut, which promote TH17 cell differentiation and enhance IL-17A production69. Elevated maternal IL-17A alters the epigenetic landscape of gut TH17 cells in MIA offspring, enhancing susceptibility to intestinal inflammation70. MIA is used as a model to investigate ASDs; however, MIA is characteristically different from ASD. Behavioural testing for MIA includes sociability assays, and marble burying tests for repetitive behaviour. Characteristics of ASD include delayed linguistic skills, hyperactive and impulsive behaviour, and unusual emotional reactions, which cannot be modelled in a mouse. Therefore, additional research is necessary to make a complete link between IL-17 and ASDs.

IL-17 may also play a role in the gut–brain axis in MIA and ASD-like behaviour in mice. Balance between the gut microbiota and TH17 cells is essential for epithelial lipid metabolism and protection against obesity and metabolic disease71. Maternal high-fat diet (HFD) feeding induces an ASD phenotype in offspring via microbiota dysbiosis, caused by promoted growth of the Clostridiaceae bacterial family72. Expansion of Clostridiaceae SFB enhances TH17 IL-17A levels73,74. Although loss of IL-17A prevents ASD development, it remains to be demonstrated that IL-17A crosses the placental barrier during pregnancy. A possible explanation is that elevated IL-17 during pregnancy (as seen in MIA) has metabolic targets that impact fetal development. IL-17 has been shown to mediate oxidative stress and induce hypertension in pregnant women, in addition to altering the metabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan75. Tryptophan is a precursor for several highly neuro-active compounds including kynurenine76. Administration of IL-17A to pregnant dams elevated maternal and fetal serum levels of kynurenine, causing social behavioural defects, while kynurenine administration alone was sufficient to induce an ASD phenotype in offspring76. This emerging research avenue demonstrates that ASD development is a complex interplay of immune activation, metabolic dysregulation and neurological dysfunction, with IL-17 playing a central role.

Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous work by the Silvo-Santos laboratory has shown that meningeal-resident γδ17 T cells play a role in short-term memory, as complete loss of γδ T cells or IL-17A is sufficient to induce short-term memory loss4. More recent work by this group has demonstrated that meningeal γδ T cell-derived IL-17 contributes to AD development in the 3xTg mouse model of AD, where the infusion of anti-IL-17 antibodies delayed memory impairment7. The pathology of AD is well characterized by memory loss, and posthumously by the deposition of plaques in the brain parenchyma consisting of abnormal aggregation of amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau77. Although much credence has been given to the contribution of amyloid-β to AD development, recent studies have linked AD with metabolic disorder, with AD patients frequently presenting with dysregulated systemic glucose metabolism and dyslipidaemia78,79. In mice, acute administration of amyloid-β oligomers into the ventricles was sufficient to decrease systemic glucose handling and insulin signalling as early as 1 week after injection80. Many studies have implicated a pathological role of IL-17 in the progression of AD, with IL-17 being suggested as a prognostic marker of disease81. At the same time, overexpression of IL-17A improved glucose metabolism, improved spatial memory and increased amyloid-β clearance in mice predisposed to AD (TgAPPswe/PS1De9 mice)82. Although the role of IL-17 in AD is controversial, these new links between IL-17 signalling, systemic glucose metabolism and AD development may provide important insight into the development of AD.

Epilepsy.

IL-17 has also been linked with epileptic seizures, which are induced by dysregulated neuronal electrical activity, causing unconscious muscle convulsions. Anticonvulsant drugs used to treat epilepsy also have anti-inflammatory properties, suggesting a link between inflammation and epileptogenesis83. Studies have correlated serum IL-17A concentration and epileptic seizure severity in humans, with an expansion of TH17 cells in the blood of patients with epilepsy84,85. γδ17 T cells infiltrate the brain parenchyma of patients with epilepsy, predominantly in epileptogenic lesions, with γδ17 T cell numbers positively correlating with seizure severity86. Deficiency of γδ T cells and IL-17RA in mice reduced seizure activity in a kainic acid-induced seizure model86.

The brain consumes 20% of dietary glucose to operate efficiently, making brain activity susceptible to changes in available metabolites. The ketogenic diet, initially used in 1921 to treat drug-resistant epilepsy, greatly reduces whole-body glucose levels and has shown to be effective in treating drug-resistant epilepsy87. Additionally, a ketogenic diet alters the ratio of TH17 cells to regulatory T cells, decreasing TH17 cell numbers by downregulating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and HIF1α expression, which attenuated epileptic activity88. The ketogenic diet also reshapes the gut microbiome, increasing bifidobacteria levels associated with an anti-seizure response and potentially impacting IL-17 levels89,90. Combined, the implications of IL-17 in autism-like behaviour, AD and epilepsy highlight a role for IL-17 beyond typical host defence, and suggest that IL-17 may coordinate the metabolic, immune and nervous systems.

IL-17 connecting systemic and cellular metabolism

Coordination between the immune and metabolic systems throughout evolution is a logical step for survival. Survival depends on immunometabolic communication to rapidly generate energy to mount an immune response, in addition to knowing what energy stores are available. At steady state, mammals maintain a high body temperature with little fluctuation beyond a physiological set point, which is energy demanding and requires coordinated cross-talk among the metabolic, immune and nervous systems for tight energy management91. In the context of whole-body metabolism, IL-17A signalling is involved in metabolic responses to environmental cues1, including feeding, diet and temperature. In turn, metabolic processes and diet regulate IL-17 production by immune cells. Thus, IL-17 is regulated by systemic metabolism, via providing fuel for the cellular metabolism required for IL-17 production in immune cells, and in turn, IL-17 feeds back to regulate systemic metabolism.

Cellular metabolism regulates IL-17 expression

T cells engage specific metabolic pathways to support their effector programming, and fuel preference differs between immune cell subsets92. A feature of innate IL-17-producing cells is enhanced mitochondrial metabolism and lipid uptake92,93. Furthermore, γδ17 T cells show preferential uptake of palmitate and cholesterol esters in culture92. Adipose tissue is a site rich in lipids, and is also enriched for resident γδ17 T cells1. As γδ17 T cells preferentially take up lipids, the lipid-rich environment of adipose tissue may contribute to their enrichment and IL-17 expression92. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that a HFD increases the expression of IL-17A by γδ T cells in the lymph nodes92, liver94, blood6 and fat6 of mice. Furthermore, HFD and cholesterol supplementation can enhance the proliferation of γδ17 T cells, particularly in the tumour microenvironment92. It has also been shown that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) modulate TH17 and γδ T cell IL-17A expression, inhibiting IL-17A production to limit inflammation in the skin, gut and synovial joints preventing development of psoriasis, DSS-induced colitis and arthritis, respectively95–97. Production of ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate during a ketogenic diet expands γδ17 T cells in adipose and lung tissue98,99. Therefore, lipid species generated in specific environmental or metabolic contexts regulate IL-17 expression. This may provide clues to metabolic situations that require IL-17, creating a systemic-to-cellular immunometabolism loop.

IL-17 regulates the metabolism of target cells

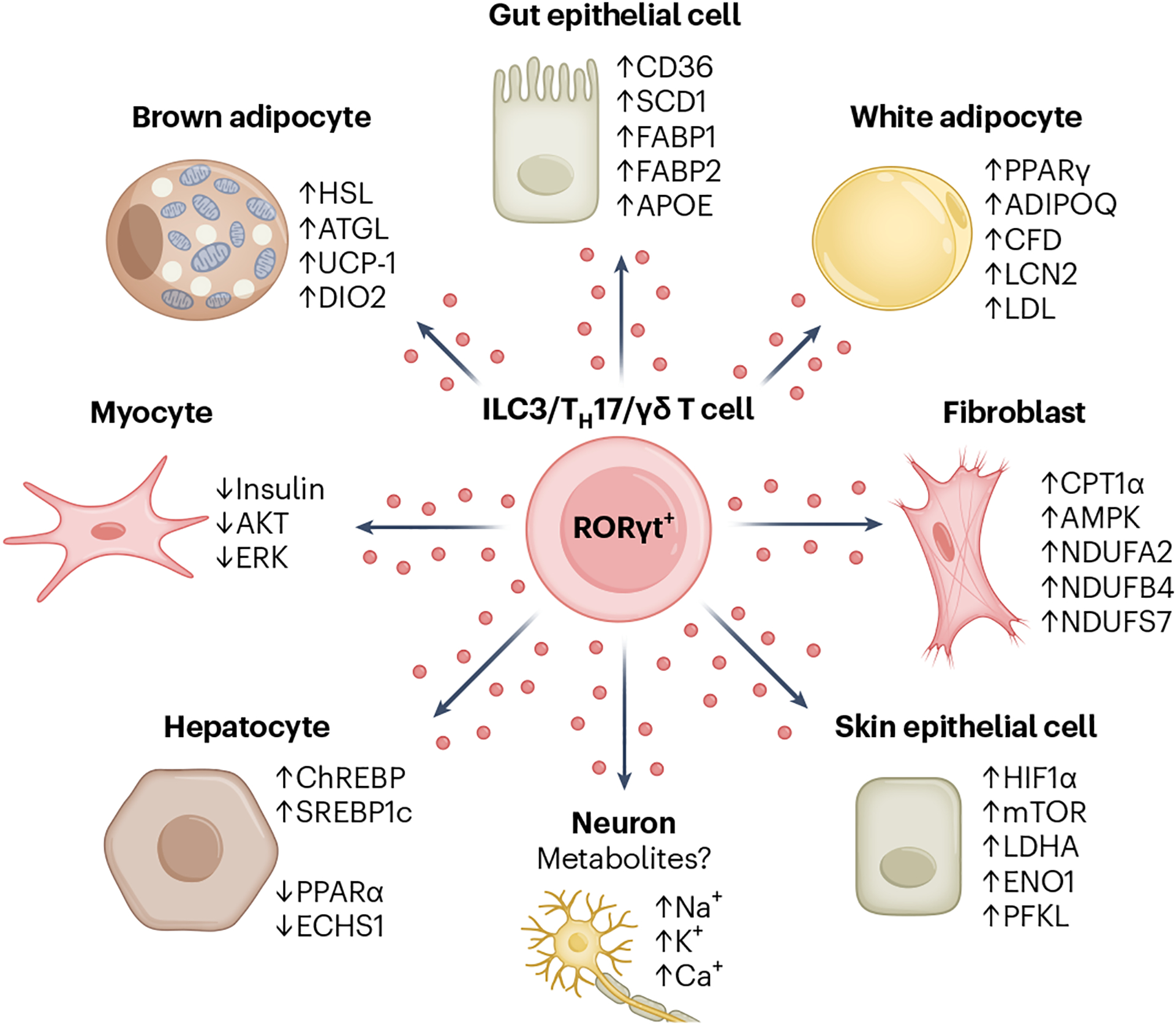

A growing number of cell types have been described to respond to IL-17A by upregulating energy-intensive pathways that support cellular survival, cytokine production and metabolite biosynthesis36. Fibroblasts, keratinocytes and epithelial cells are canonical IL-17A target cells, and this is largely attributed to their abundant expression of IL-17RC, which, as a heterodimer with IL-17RA, is the receptor for IL-17A and IL-17F signalling. In skin epithelial cells, IL-17RC signalling induces mTOR via AKT signalling, driving HIF1a-mediated glucose uptake and glycolysis for cell proliferation and thereby aiding wound healing (Fig. 4)100. Additionally, IL-17A acts on hepatocytes, immune cells (for example, Kupffer cells and dendritic cells), adipocytes and neurons. Genetic and pharmacological interventions have shown that IL-17 directs cholesterol metabolism in the periphery, neuronal activity within the CNS and nutrient absorption in the small intestine101–103.

Fig. 4 |. IL-17 signalling modulates cellular metabolism in a host of non-immune target cells.

IL-17 is expressed by cells of the immune system such as γδ T cells, TH17 cells, and ILC3s, while IL-17 receptor expression is predominantly limited to non-immune cells such as adipocytes, fibroblasts and epithelial cells. IL-17 signalling regulates the expression of genes involved in a variety of metabolic pathways, including lipolysis (adipocytes), lipogenesis (gut epithelial cells), oxidative phosphorylation (fibroblasts) and glycolysis (skin epithelial cells). The outcome of metabolic rewiring by IL-17 signalling is cell-type specific and affects higher-order functions including thermogenesis, weight fluctuation and wound healing.

A major action of IL-17 cytokine signalling is to stabilize specific mRNA sequences104. Pro-inflammatory transcripts commonly exhibit short half-lives, an intrinsic property that curbs inappropriate immune responses105. By modulating the activity of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), IL-17 limits decay of select mRNA target sequences105. In this way, IL-17 cooperates with powerful transcriptional activators such as TNF and IL-6 to enhance the longevity of multiple short-lived transcripts36,105. Cooperation between RBPs and IL-17 stabilizes transcripts that encode IκBζ, a nuclear regulator of NF-κB that is essential for IL-17A-mediated induction of fatty acid oxidation (via upregulation of the rate-limiting enzyme encoded by Cpt1a) and cellular survival in fibroblastic reticular cells105,106 (Fig. 4). Moreover, IL-17 supports glucose uptake in these cells, an effect that requires both IκBζ and IL-17RA105. In a similar fashion, IL-17A and IκBζ promote oxidative metabolism in epithelial cells and synovial fibroblasts36,106. The cooperative actions of IL-17 and RBPs also elevate C/EBPb abundance. C/EBPb is a major transcriptional target of IL-17, which induces genes required for choline metabolism, fatty acid transport and glucose uptake and also functions as a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation107,108. Thus, IL-17 has strong actions on metabolism. In adipose tissue, for example, where IL-17 is enriched, it is likely to regulate adipocytes and therefore energy homeostasis. IL-17 expression in lymphocytes is regulated by lipids and distinct mitochondrial metabolism, and IL-17 in turn regulates metabolic pathways in target cells. Indeed, the control of IL-17 over metabolism is evident across diverse members of the animal kingdom, including fish and mammals36,109.

Examples of systemic metabolic regulation by IL-17

Regulation of feeding behaviour.

One of the first indications that IL-17 signalling plays a role in feeding came from C. elegans. Worms can have one of two behaviours—aggregated or individual feeding. Worms with a null mutation in the neuropeptide receptor 1 (npr-1) gene aggregate110. Using npr-1-null worms for a forward genetic screen for loss of aggregation, researchers found mutations in the IL-17 receptor orthologue (ilcr-1 in C. elegans)66. The IL-17 orthologue in worms, termed ilc-17.1 (IL-17-cytokine-related gene 1), played a similar role in feeding behaviour (Fig. 5). However, C. elegans does not have T cells; rather, ilc-17.1 was produced by neurons, a further link between IL-17 and neuromodulation. A recent study also demonstrated a role for the IL-17 orthologue in C. elegans feeding111, although it did not show a role for IL-17 in feeding behaviour, but rather showed that IL-17 is required for nutrient processing with feeding. This elegant study highlighted IL-17 as a surrogate signal for food or nutrient availability. It showed that ILC-17.1 is expressed on amphid neurons, which have epithelial-like functions in sensing environmental cues (Fig. 5). ILC-17.1 production by amphid neurons was increased in the presence of food. Importantly, IL-17 didn’t impact glucose uptake in C. elegans but was required for glucose utilization. Worms arrest in the larva stage in the absence of nutrients, and progress to adulthood only when favourable temperature and nutrients are present111. Loss of ILC-17.1 limited glucose metabolism, which prevented nematode development to adulthood as a result of ILC-17.1 acting on p53 and thereby halting the cell cycle111. In C. elegans, bacteria provide a food source; however, in humans and mice, IL-17 expression is also elevated during feeding, a period characterized by the potential entry of bacterial pathogens and intense nutrient processing. This raises evolutionary questions about IL-17’s dual role in metabolism and host defence during feeding and how the role of IL-17 in metabolism connected to host defence during evolution.

Fig. 5 |. Evidence for evolutionarily conserved roles for IL-17 signalling beyond immunity.

Studies across species, including worms, fish, molluscs, mice and humans, indicate that IL-17 may play a conserved role in several processes. IL-17 plays an apparent role in feeding behaviour, as circulating IL-17 levels increase shortly after feeding, which regulates glucose metabolism and food consumption. The role of IL-17 in feeding behaviour may in part be linked to nervous system modulation, as IL-17 signalling regulates the sensory response to feeding in the nematode, while ensuring appropriate innervation of metabolic organs such as adipose tissue. Finally, underexpression or overexpression of IL-17 consistently detrimentally impacts tissue development. Loss of IL-17 signalling impairs adipose tissue neurogenesis and limits gastrointestinal development, whereas overexpression of IL-17 has been linked to the development of autism-like behaviour via abnormal cortex development. BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CTX, cortex; HPC, hippocampus; HY, hypothalamus; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

In mammals, feeding behaviour is regulated by neurons of the hypothalamus that express pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) or agouti-related protein (AgRP). POMC neurons reduce food intake, whereas AgRP neurons enhance food intake112. Whether IL-17 signalling occurs in the hypothalamus, or regulates feeding behaviour, has not been fully elucidated. However, hypothalamic cells such as neurons113, astrocytes and microglia express IL-17RA. Systemic administration of IL-17A induces a temporal increase in both POMC and AgRP expression, with an early increase in POMC expression (1 h after injection), and a late increase in AgRP (4 h after injection) similar to what is observed after feeding. IL-17 also decreases food consumption, similarly to leptin administration114 (Fig. 5). To evaluate the translation of this finding, human participants fasted overnight and were fed 2 h before blood donation. An increase in circulating IL-17A levels was observed 2 h after feeding114. Together, these studies in worms, mice and humans suggest a major role for IL-17 in regulating feeding.

Regulation of nutrient utilization.

In addition to feeding behaviour, there is mounting evidence that IL-17 regulates nutrient absorption in the gut. In Japanese medaka fish (Oryzias latipes), IL-17 receptor A1 knock-out (IL-17RA1−/−) fish have lower body mass than their wild-type controls115. Furthermore, the intestinal tract was shorter in IL-17RA1−/− fish than in wild-type fish, with decreased expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism, lipid biosynthesis and steroid metabolism in the intestine115 (Fig. 5). The decrease in lipid metabolism may in part be due to differences in the microbiome of IL-17A/F1−/− fish109. Similarly, IL-17A plays a role in lipid metabolism in the gut epithelium of mice. In the intestine, ILC3s, γδ T cells and CD4+ T cells produce IL-17 in a circadian rhythm116, which regulates lipid uptake and metabolism genes117 (Fig. 5). The intestine is enriched in γδ T cells, with different populations located in the epithelial layer and lamina propria. γδ T cells of the lamina propria are key players in regulating the transcriptional programming of gut epithelial cells in response to diet118. Intestinal γδ T cells regulate IL-22 production by ILC3s to transcriptionally reprogramme epithelial cells in response to a carbohydrate-rich diet118. Collectively, these studies show that IL-17 fluctuates daily, which we suggest is related by diurnal food intake, and is important for nutrient uptake in gut epithelial cells. Throughout evolution, there is evidence that IL-17 acts on digestive cells, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role of IL-17A in regulating metabolism, particularly lipid metabolism in target cells.

Regulation of energy expenditure.

Adipose tissue needs to respond rapidly and dynamically to energy demands, including fasting, feeding, exercise and cold, as well as excess energy intake. Noradrenergic signalling in adipose tissue in response to cold stimuli induces the expression of UCP-1, which generates heat production through the catabolism of lipids, known as thermogenesis119 (Fig. 5). Adipose tissue has a unique immune environment, including a subset of tissue-resident clonal Vγ6+ γδ T cells which produce both IL-17A and IL-17F1,108. In mice, a loss of γδ T cells or IL-17A caused a decrease in the adipose thermogenic programme, including Ucp1, Dio2 and Ppargc1a genes. This resulted in the inability of Tcrd−/− and Il17a−/− mice to efficiently increase their body temperature during a cold challenge1. Synergistic signalling of IL-17A with TNF from γδ T cells induced IL-33 expression in adipose stromal cells, which has been shown to play a major role in thermogenesis120. At the same time, IL-17 signalling supports thermogenesis through neuronal innervation in adipose tissue2. IL-17F produced by adipose Vγ6+ γδ T cells acts on IL-17RC on adipocytes inducing expression of TGF-β, which enhances neurogenesis in adipose tissue2. Loss of IL-17F or IL-17RC leaves mice susceptible to cold challenge owing to a loss of neuronal signalling in brown adipose tissue2 (Table 1), as neuronal activity in adipose tissue is important for adipocytes to respond to adrenergic signals during energy demand. There is complexity in delineating IL-17 signalling, as both IL-17A and IL-17F can signal through IL-17RA and IL-17RC heterodimers9. However, IL-17A and IL-17F, which are produced by the same adipose γδ T cells, may also act in synergy for a sufficient thermogenic response. These studies yet again provide support for IL-17 as a critical player connecting the immune system, nervous system and metabolism for an efficient response to environmental changes.

Table 1 |.

IL-17 is involved in a neuroimmunometabolic signalling axis

| Organism | Feeding regulation | Nervous regulation | Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nematode | Feeding increases IL-17A expression, regulating glucose metabolism | IL-17 is a neuromodulator of nematode sensory responses | Loss of IL-17 (ILC-17.1−/−) prevents progression into adulthood |

| Fish | IL-17A regulates lipid metabolism genes in the gut | Currently unknown | Loss of IL-17 signalling (IL-17RA1−/−) limits full body growth and gastrointestinal development |

| Mouse | Feeding increases IL-17A expression, regulating food consumption | IL-17 regulates appropriate innervation of adipose tissue; inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis | Overexpression of IL-17A during embryonic development presents an autism-like phenotype |

| Human | Feeding increases circulating IL-17A levels | IL-17 induces neuronal differentiation from induced pluripotent stem cell progenitors | Currently unknown |

White adipose tissue IL-17 signalling maintains an immunosuppressive environment by supporting expansion of a homeostatic tissue-resident population of IL-10-expressing regulatory T cells. In addition, IL-17 signalling modulates HFD-induced weight gain induced by inhibiting UCP-1 expression via PPARγ activity. Conversely, in brown adipose tissue, IL-17A supports lipolysis and UCP-1 expression, while IL-17F is essential for appropriate innervation of brown adipose tissue, together ensuring appropriate body temperature regulation. In the gut, circadian expression of IL-17 regulates circadian expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism to maintain gastrointestinal physiological homeostasis. More recently, roles for IL-17 signalling in behaviour have emerged, whereby IL-17 signalling derived from meningeal tissue-resident γδ T cells enhances excitatory glutamatergic signalling inducing anxious behaviour, in addition to supporting brain-derived neurotrophic factor production from glial cells for short-term memory. A gut–brain IL-17 signalling axis has recently shown a role for IL-17 in satiety. Together, these signalling pathways highlight a new neuroimmunometabolic role for IL-17.

Modulation of metabolism by IL-17 in metabolic disease

Diabetes mellitus.

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease in which whole-body glucose handling is disrupted owing to impaired insulin signalling. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) primarily develops through insulin gene mutations or an autoimmune response against pancreatic beta cells, which produce insulin in response to glucose levels121. Obesity plays a major role in the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D)122. T1D is an autoimmune disease with an IL-17 component, involving an increased frequency of circulating TH17 cells, with heightened IL-17A and RORγt expression123. Loss of IL-17A expression in a mouse model of T1D was sufficient to reduce the concentration of blood glucose and raise serum insulin levels124. Although T2D is not an autoimmune disease, serum levels of IL-17A are also increased, suggesting that elevated levels of IL-17A may play a role in the aetiology of the disease125. Furthermore, childhood obesity predisposes children to T2D development, and children living with obesity have increased circulating proportions of IL-17A-producing cells including MAIT-17 cells126. Co-culture of IL-17A-producing MAIT cells with human skeletal muscle cells in vitro inhibited insulin signalling, which could be recovered in the presence of anti-IL-17A antibodies126. Although these studies suggest a negative role for IL-17A signalling in glucose sensitivity, it has also been reported that low-dose IL-17A or IL-17F therapy can recover metabolic defects associated with a streptozotocin-induced diabetes mouse model127. Together, these studies point to IL-17 signalling in whole-body glucose homeostasis, although this remains complex between different pathologies.

Obesity.

IL-17A is emerging as a major systemic metabolic messenger, which can modulate feeding behaviour66,114, lipid metabolism94 and homeothermy1,2. Therefore, it is not surprising that IL-17A signalling would also play a role in obesity and metabolic disease. IL-17A signalling has been demonstrated to inhibit adipogenesis and decrease leptin signalling, resulting in a pro-inflammatory environment and decreasing satiety, respectively128,129. Mice fed a HFD have increased IL-17A in the lymph nodes92, liver94, blood6 and fat6. IL-17A signalling increases fatty acid accumulation in the livers of mice94. Lipid accumulation also increases in human hepatocytes treated with IL-17A, via induction of the fatty acid synthesis genes MLXIPL and SREBF1 (also known as CHREBP and SREBP1c, respectively)94. In agreement with this, HFD-fed mice lacking IL-17A had fewer hepatocyte lipid droplets compared to their wild-type controls130. Moreover, mice lacking IL-17A were slower to gain weight on a HFD130. Deletion of adipocyte IL-17RA prevented HFD-induced obesity6. As the global levels of obesity continue to increase, it is becoming urgent to find novel therapeutic interventions. These studies solidify a role for IL-17 signalling in lipid metabolism and obesity-associated metabolic disease, and IL-17 signalling may be a new therapeutic target in the treatment of metabolic disease.

Cardiovascular disease.

Increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a common trait among patients presenting with low-grade inflammatory disease, such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, who commonly display metabolic complications such as insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia131,132. Serum IL-17 concentration may act as a potential biomarker for CVD, particularly in patients living with obesity, in addition to IL-17A polymorphisms potentially contributing to disease development, but the contribution of IL-17 signalling to CVD is incompletely understood133,134. The development of atherosclerotic plaques is a major factor for CVD and myocardial infarction. Some studies suggest that IL-17 signalling plays both a direct and indirect pro-atherogenic role in CVD, by modulating cholesterol, LDL and HDL metabolism and contributing to atherosclerotic plaque formation135–138. However, further work is necessary to clearly define the role of IL-17 in CVD.

Cachexia.

Cancer-associated cachexia (CAC) is a complex metabolic disorder of muscle and adipose tissue wasting during cancer and is a leading cause of mortality in certain types of cancer139,140. Patients with CAC display an overactive whole-body metabolism, primarily due to increased β-oxidation, which cannot be overcome by increased feeding141. The concentration of serum IL-17A is increased in many cancer types, including ovarian cancer142, lung adenocarcinoma143 and multiple cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, where it has been shown to mediate CAC144,145. However, the mechanisms reported by which IL-17A mediates CAC differ depending on the cancer type. In ovarian and gastrointestinal tract cancers, a strong correlation exists between high serum levels of IL-17A and decreased serum concentrations of proteins associated with nutritional status, such as prealbumin, transferrin and retinol binding protein144,146. As IL-17 expression has been demonstrated to regulate glucose metabolism in C. elegans and food consumption in mice, overexpression of IL-17 in CAC may contribute to disease progression through overuse of glucose or enhanced satiety, ultimately leading to malnutrition. In a Lewis lung carcinoma-induced CAC model, there was decreased myogenin and increased atrogen-1 and MuRF1, associated with muscle atrophy143. Overexpression of IL-17A was sufficient to induce lipolytic adipose tissue wasting and muscle loss mediated by increased MuRF1 (ref. 147). Thus, antibodies against IL-17A may offer therapeutic value against CAC, to prevent malnutrition and wasting.

Metabolic changes during therapeutic IL-17 blockade

As the metabolism-modulating activity of IL-17 is only recently emerging, studies involving the effect of anti-IL-17 therapeutics on metabolism have not been fully conducted. Currently, several anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibodies are prescribed to patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, such as secukinumab and ixekizumab, which neutralize IL-17A; bimekizumab, which neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F; or brodalumab, which blocks signalling through IL-17RA45. However, clinical data on the effects of monoclonal antibodies against IL-17 signalling on metabolism is limited. Secukinumab is the most extensively studied anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody with some information on metabolism, although there are conflicting findings on its effects on lipid metabolism. In mice, treatment with secukinumab decreased HDL and cholesterol levels, while having no effect on triglyceride concentration. Retrospective studies in humans found no effect of secukinumab on lipid-associated parameters148–150. However, a later study indicated that treatment with secukinumab increased the prevalence of hypertriglyceridaemia with increased time of treatment, suggesting that secukinumab may further disrupt the lipid profile of patients with psoriasis138. However, metabolic profiling of psoriatic patients found there were higher levels of lysophosphatidylcholines, lysophosphatidylinositols, lysophosphatidic acids and free fatty acids, but lower levels of acylcarnitines and dicarboxylic acids, and that these changes were ameliorated after ixekizumab treatment139. This warrants further investigation of the metabolic modulatory role of anti-IL-17 treatment, and careful characterization of the patient profile in terms of lipid parameters and obesity may be required, as IL-17 could have differential effects depending on the metabolic status of the patient.

Conclusions and future directions

IL-17 has been involved across evolution in host defence and barrier integrity, particularly in the digestive tract. IL-17 is expressed at steady state, displays circadian rhythmicity, and is responsive to bacteria across species. The homeostatic functions of IL-17 are now inclusive of nutrient handling, and IL-17 coordinates food intake and absorption across worms, mice and humans (Fig. 5). Its involvement in food intake may explain its relevance to adipose tissue, which adapts energy demands during fasting, feeding and thermoregulation. Adipose IL-17 appears to play a dual role, acting directly on adipocytes and neurons. IL-17 plays an evolutionary role in coordinating metabolic homeostasis in response to feeding, with environment cues. Understanding the regulation of metabolism by IL-17 could lead to new therapeutic targets for obesity, metabolic disorders and excess fat deposition. Furthermore, the effects of IL-17 on peripheral neurons and CNS warrant further investigation to better understand the role of the immune system in neuropathological conditions, which might involve metabolism. IL-17 represents a promising candidate in the emerging field of neuroimmunometabolism.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by the NIH (5R01AI134861), Science Foundation Ireland (16/FRL/3865) and an Irish Research Council (IRC) Fellowship (A.D.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kohlgruber AC et al. γδ T cells producing interleukin-17A regulate adipose regulatory T cell homeostasis and thermogenesis. Nat. Immunol 19, 464–474 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu B et al. γδ T cells and adipocyte IL-17RC control fat innervation and thermogenesis. Nature 578, 610–614 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi GB et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 351, 933–939 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro M et al. Meningeal γδ T cell–derived IL-17 controls synaptic plasticity and short-term memory. Sci. Immunol 4, eaay5199 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alves de Lima K et al. Meningeal γδ T cells regulate anxiety-like behavior via IL-17a signaling in neurons. Nat. Immunol 21, 1421–1429 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teijeiro A, Garrido A, Ferre A, Perna C & Djouder N Inhibition of the IL-17A axis in adipocytes suppresses diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders in mice. Nat. Metab 3, 496–512 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brigas HC et al. IL-17 triggers the onset of cognitive and synaptic deficits in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. 36, 109574 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouvier E, Luciani MF, Mattéi MG, Denizot F & Golstein P CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a herpesvirus saimiri gene. J. Immunol 150, 5445–5456 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identified IL-17A (CTLA-8) and highlighted the cytokine’s homology with the herpesvirus Saimiri gene ORF13.

- 9.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ & Gaffen SL The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity 50, 892–906 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Z et al. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity 3, 811–821 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study identified an IL-17A-binding receptor, termed IL-17R (and now known as IL-17RA).

- 11.Gaffen SL Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol 9, 556–567 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Infante-Duarte C, Horton HF, Byrne MC & Kamradt T Microbial lipopeptides induce the production of IL-17 in Th cells. J. Immunol 165, 6107–6115 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA & Coffman RL Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol 136, 2348–2357 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, De Sauvage FJ & Gurney AL Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J. Biol. Chem 278, 1910–1914 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langrish CL et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med 201, 233–240 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study characterized TH17 cells: a class of CD4+ T cells that produce IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-6 and TNF, require IL-23, and frequently drive autoimmunity.

- 16.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM & Stockinger B TGFβ in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24, 179–189 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettelli E et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mangan PR et al. Transforming growth factor-β induces development of the TH17 lineage. Nature 441, 231–234 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KHG & Lavelle EC A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17–producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med 203, 1685–1691 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanov II et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conti HR et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med 206, 299–311 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connor W, Zenewicz LA & Flavell RA The dual nature of TH17 cells: shifting the focus to function. Nat. Immunol 11, 471–476 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright JF et al. Identification of an interleukin 17F/17A heterodimer in activated human CD4+ T cells. J. Biol. Chem 282, 13447–13455 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright JF et al. The human IL-17F/IL-17A heterodimeric cytokine signals through the IL-17RA/IL-17RC receptor complex. J. Immunol 181, 2799–2805 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goepfert A, Lehmann S, Blank J, Kolbinger F & Rondeau JM Structural analysis reveals that the cytokine IL-17F forms a homodimeric complex with receptor IL-17RC to drive IL-17RA-independent signaling. Immunity 52, 499–512 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provided structural evidence for IL-17RA-independent IL-17 signalling events, supporting previous reports of IL-17-induced gene expression in Il17ra−/− cells, and identified 2:1 complexes of IL-17RC–IL-17F.

- 26.Su Y et al. Interleukin-17 receptor D constitutes an alternative receptor for interleukin-17A important in psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Sci. Immunol 4, eaau9657 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson SC et al. Organizing structural principles of the IL-17 ligand–receptor axis. Nature 609, 622–629 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novatchkova M, Leibbrandt A, Werzowa J, Neubüser A & Eisenhaber F The STIR-domain superfamily in signal transduction, development and immunity. Trends Biochem. Sci 28, 226–229 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C et al. Act1, a U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase for IL-17 signaling. Sci. Signal 2, ra63 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seon HC, Park H & Dong C Act1 adaptor protein is an immediate and essential signaling component of interleukin-17 receptor. J. Biol. Chem 281, 35603–35607 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K & Cao Z Requirement of tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated factor (Traf)6 in interleukin 17 signal transduction. J. Exp. Med 191, 1233–1240 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maitra A et al. Distinct functional motifs within the IL-17 receptor regulate signal transduction and target gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7506–7511 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong B et al. Negative regulation of IL-17-mediated signaling and inflammation by the ubiquitin-specific protease USP25. Nat. Immunol 13, 1110–1117 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Draberova H et al. Systematic analysis of the IL-17 receptor signalosome reveals a robust regulatory feedback loop. EMBO J. 39, e104202 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hymowitz SG et al. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 20, 5332–5341 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bechara R, McGeachy MJ & Gaffen SL The metabolism-modulating activity of IL-17 signaling in health and disease. J. Exp. Med 218, e20202191 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruddy MJ et al. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members. J. Biol. Chem 279, 2559–2567 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teunissen MBM, Koomen CW, De Waal Malefyt R, Wierenga EA & Bos JD Interleukin-17 and interferon-γ synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol 111, 645–649 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by flagellins from segmented filamentous bacteria. Front. Immunol 10, 2750 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwakura Y, Nakae S, Saijo S & Ishigame H The roles of IL-17A in inflammatory immune responses and host defense against pathogens. Immunol. Rev 226, 57–79 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raffatellu M et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus–induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Med 14, 421–428 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye P et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung Cxc chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J. Exp. Med 194, 519–528 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song X et al. IL-17RE is the functional receptor for IL-17C and mediates mucosal immunity to infection with intestinal pathogens. Nat. Immunol 12, 1151–1158 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luzza F et al. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J. Immunol 165, 5332–5337 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mills KHG IL-17 and IL-17-producing cells in protection versus pathology. Nat. Rev. Immunol 10.1038/s41577-022-00746-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reich K et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med 385, 142–152 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparber F & Leibundgut-Landmann S Interleukin-17 in antifungal immunity. Pathogens 8, 54 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lévy R et al. Genetic, immunological, and clinical features of patients with bacterial and fungal infections due to inherited IL-17RA deficiency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E8277–E8285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boisson B et al. An ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity 39, 676–686 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamada H et al. Tc17, a unique subset of CD8 T cells that can protect against lethal influenza challenge. J. Immunol 182, 3469–3481 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X et al. Host-derived lipids orchestrate pulmonary γδ T cell response to provide early protection against influenza virus infection. Nat. Commun 12, 1914 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boari JT et al. IL-17RA signaling reduces inflammation and mortality during Trypanosoma cruzi infection by recruiting suppressive IL-10-producing neutrophils. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002658 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivanov II et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139, 485–498 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study described the striking association between SFB and IL-17, as intestinal SFB colonization was observed to determine the abundance of TH17 cells and IL-17 itself.

- 54.Ivanov II et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe 4, 337–349 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritchie ND, Ijaz UZ & Evans TJ IL-17 signalling restructures the nasal microbiome and drives dynamic changes following Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization. BMC Genomics 18, 807 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Regen T et al. IL-17 controls central nervous system autoimmunity through the intestinal microbiome. Sci. Immunol 6, eaaz6563 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seifert HA et al. Antibiotics protect against EAE by increasing regulatory and anti-inflammatory cells. Metab. Brain Dis 33, 1599–1607 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang D et al. Dysregulated lung commensal bacteria drive interleukin-17B production to promote pulmonary fibrosis through their outer membrane vesicles. Immunity 50, 692–706 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morais LH, Schreiber HL & Mazmanian SK The gut microbiota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 19, 241–255 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonardi I et al. Mucosal fungi promote gut barrier function and social behavior via type 17 immunity. Cell 185, 831–846 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu X et al. Dectin-1 signaling on colonic γδ T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nat. Immunol 10.1038/s41590-023-01447-8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reed MD et al. IL-17a promotes sociability in mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature 577, 249–253 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riol-Blanco L et al. Nociceptive sensory neurons drive interleukin-23-mediated psoriasiform skin inflammation. Nature 510, 157–161 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen JA et al. Cutaneous TRPV1+ neurons trigger protective innate type 17 anticipatory immunity. Cell 178, 919–932 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enamorado M et al. Immunity to the microbiota promotes sensory neuron regeneration. Cell 186, 607–620 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen C et al. IL-17 is a neuromodulator of Caenorhabditis elegans sensory responses. Nature 542, 43–48 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luo H et al. Interleukin-17 regulates neuron-glial communications, synaptic transmission, and neuropathic pain after chemotherapy. Cell Rep. 29, 2384–2397 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Atladóttir HÓ et al. Maternal infection requiring hospitalization during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord 40, 1423–1430 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim S et al. Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature 549, 528–532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim E et al. Maternal gut bacteria drive intestinal inflammation in offspring with neurodevelopmental disorders by altering the chromatin landscape of CD4+ T cells. Immunity 55, 145–158 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kawano Y et al. Microbiota imbalance induced by dietary sugar disrupts immune-mediated protection from metabolic syndrome. Cell 185, 3501–3519 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernandes DJ et al. Exposure to maternal high-fat diet induces extensive changes in the brain of adult offspring. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 149 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Buffington SA et al. Microbial reconstitution reverses maternal diet-induced social and synaptic deficits in offspring. Cell 165, 1762–1775 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mirpuri J, Raetz M, Wilhelm C, Sturge C & Yarovinsky F Maternal high-fat diet alters TH17 responses and bacterial colonization in newborn mice. J. Immunol 190, 1–9 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dhillion P et al. IL-17-mediated oxidative stress is an important stimulator of AT1-AA and hypertension during pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol 303, 353–358 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murakami Y et al. The effects of maternal interleukin-17A on social behavior, cognitive function and depression-like behavior in mice with altered kynurenine metabolites. Int. J. Tryptophan Res 10.1177/11786469211026639 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fu J et al. The role of Th17 cells/IL-17A in AD, PD, ALS and the strategic therapy targeting on IL-17A. J. Neuroinflammation 19, 98 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.González A, Calfío C, Churruca M & Maccioni RB Glucose metabolism and AD: evidence for a potential diabetes type 3. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther 14, 56 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Craft S The role of metabolic disorders in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: two roads converged. Arch. Neurol 66, 300–305 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clarke JR et al. Alzheimer-associated Aβ oligomers impact the central nervous system to induce peripheral metabolic deregulation. EMBO Mol. Med 7, 190–210 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohammadi Shahrokhi V et al. IL-17A and IL-23: plausible risk factors to induce age-associated inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Immunol. Invest 47, 812–822 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang J, Kou J, Lalonde R & Fukuchi K ichiro. Intracranial IL-17A overexpression decreases cerebral amyloid angiopathy by upregulation of ABCA1 in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun 65, 262–273 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu D, Miller SD & Koh S Immune mechanisms in epileptogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci 7, 195 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mao LY et al. Interictal interleukin-17A levels are elevated and correlate with seizure severity of epilepsy patients. Epilepsia 54, e142–e145 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kumar P et al. Proinflammatory IL-17 pathways dominate the architecture of the immunome in pediatric refractory epilepsy. JCI Insight 5, e126337 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu D et al. Peripherally derived T regulatory and γδ T cells have opposing roles in the pathogenesis of intractable pediatric epilepsy. J. Exp. Med 215, 1169–1186 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li B, Tong L, Jia G & Sun R Effects of ketogenic diet on the clinical and electroencephalographic features of children with drug therapy-resistant epilepsy. Exp. Ther. Med 5, 611–615 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ni F-F et al. The effects of ketogenic diet on the TH17/Treg cells imbalance in patients with intractable childhood epilepsy. Seizure 38, 17–22 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xie G et al. Ketogenic diet poses a significant effect on imbalanced gut microbiota in infants with refractory epilepsy. World J. Gastroenterol 23, 6164–6171 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dahlin M et al. Higher levels of Bifidobacteria and tumor necrosis factor in children with drug-resistant epilepsy are associated with anti-seizure response to the ketogenic diet. eBioMedicine 80, 104061 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ganeshan K et al. Energetic trade-offs and hypometabolic states promote disease tolerance. Cell 177, 399–413 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lopes N et al. Distinct metabolic programs established in the thymus control effector functions of γδ T cell subsets in tumor microenvironments. Nat. Immunol 22, 179–192 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chandra S et al. Transcriptomes and metabolism define mouse and human MAIT cell heterogeneity. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.20.473182 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shi W et al. Anti-IL-17 antibody improves hepatic steatosis by suppressing interleukin-17-related fatty acid synthesis and metabolism. Clin. Dev. Immunol 2013, 253046 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saito-Sasaki N et al. Maresin-1 suppresses imiquimod-induced skin inflammation by regulating IL-23 receptor expression. Sci. Rep 8, 5522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pai MH, Liu JJ, Hou YC & Yeh CL Soybean and fish oil mixture with different ω-6/ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios modulates dextran sulfate sodium-induced changes in small intestinal intraepithelial γδT-lymphocyte expression in mice. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr 40, 383–391 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim JY et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids restore TH17 and Treg balance in collagen antibody-induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 13, e0194331 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goldberg EL et al. Ketogenic diet activates protective γδ T cell responses against influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol 4, eaav2026 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldberg EL et al. Ketogenesis activates metabolically protective γδ T cells in visceral adipose tissue. Nat. Metab 2, 50–61 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Konieczny P et al. Interleukin-17 governs hypoxic adaptation of injured epithelium. Science 377, eabg9302 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buckley KM et al. IL17 factors are early regulators in the gut epithelium during inflammatory response to Vibrio in the sea urchin larva. eLife 6, e23481 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ray S, De Salvo C & Pizarro TT Central role of IL-17/Th17 immune responses and the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of intestinal fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol 30, 531–538 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Segond von Banchet G et al. Neuronal IL-17 receptor upregulates TRPV4 but not TRPV1 receptors in DRG neurons and mediates mechanical but not thermal hyperalgesia. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 52, 152–160 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Conti HR et al. IL-17 receptor signaling in oral epithelial cells is critical for protection against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Cell Host Microbe 20, 606–617 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Amatya N et al. IL-17 integrates multiple self-reinforcing, feed-forward mechanisms through the RNA binding protein Arid5a. Sci. Signal 11, eaat4617 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Majumder S et al. IL-17 metabolically reprograms activated fibroblastic reticular cells for proliferation and survival. Nat. Immunol 20, 534–545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study investigated the metabolic impact of cytokine signalling in stromal populations and identified the nuclear protein IκBζ as a critical factor for IL-17-mediated induction of cell survival, fatty acid oxidation and glucose consumption in fibroblastic reticular cells.

- 107.Ahmed M & Gaffen SL IL-17 in obesity and adipogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21, 449–453 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zúñiga LA et al. IL-17 regulates adipogenesis, glucose homeostasis and obesity. J. Immunol 185, 6947–6959 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study highlighted the role that IL-17A plays in shaping whole-body metabolic health and adipogenesis, as adipose-resident γδ T cells were shown to regulate diet-induced obesity in an IL-17A- and age-dependent fashion.

- 109.Okamura Y et al. Interleukin-17A/F1 deficiency reduces antimicrobial gene expression and contributes to microbiome alterations in intestines of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Front. Immunol 11, 425 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Laurent P et al. Decoding a neural circuit controlling global animal state in C. elegans. eLife 2015, 1–39 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Godthi A et al. Neuronal IL-17 controls C. elegans developmental diapause through p53/CEP-1. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.11.22.517560 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Biglari N et al. Functionally distinct POMC-expressing neuron subpopulations in hypothalamus revealed by intersectional targeting. Nat. Neurosci 24, 913–929 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yu Y, Cao Y, Felder RB & Wei S-G Knockdown of interleukin 17 receptor A (IL-17RA) in paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus attenuates IL-17-induced pressor responses and sympathetic excitation. FASEB J. 34, 1 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nogueira G et al. Interleukin-17 acts in the hypothalamus reducing food intake. Brain Behav. Immun 87, 272–285 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Okamura Y et al. A defective interleukin-17 receptor A1 causes weight loss and intestinal metabolism-related gene downregulation in Japanese medaka, Oryzias latipes. Sci. Rep 11, 12099 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Teng F et al. A circadian clock is essential for homeostasis of group 3 innate lymphoid cells in the gut. Sci. Immunol 4, eaax1215 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Godinho-Silva C et al. Light-entrained and brain-tuned circadian circuits regulate ILC3s and gut homeostasis. Nature 10.1038/s41586-019-1579-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sullivan ZA et al. γδ T cells regulate the intestinal response to nutrient sensing. Science 10.1126/science.aba8310 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chouchani ET, Kazak L & Spiegelman BM New advances in adaptive thermogenesis: UCP1 and beyond. Cell Metab. 29, 27–37 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Odegaard JI et al. Perinatal licensing of thermogenesis by IL-33 and ST2. Cell 166, 841–854 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bluestone JA, Herold K & Eisenbarth G Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature 464, 1293–1300 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Al-Goblan AS, Al-Alfi MA & Khan MZ Mechanism linking diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes 7, 587–591 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Honkanen J et al. IL-17 immunity in human type 1 diabetes. J. Immunol 185, 1959–1967 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Qiu AW, Cao X, Zhang WW & Liu QH IL-17A is involved in diabetic inflammatory pathogenesis by its receptor IL-17RA. Exp. Biol. Med 246, 57–65 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Arababadi MK et al. Nephropathic complication of type-2 diabetes is following pattern of autoimmune diseases? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.09.027 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bergin R et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T cells are associated with insulin resistance in childhood obesity, and disrupt insulin signalling via IL-17. Diabetologia 65, 1012–1017 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mohamed R et al. Low-dose IL-17 therapy prevents and reverses diabetic nephropathy, metabolic syndrome, and associated organ fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 27, 745–765 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shin JH, Shin DW & Noh M Interleukin-17A inhibits adipocyte differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells and regulates pro-inflammatory responses in adipocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol 77, 1835–1844 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]