Abstract

The hepatic leukemia factor (HLF) gene codes for a basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) protein that is disrupted by chromosomal translocations in a subset of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias. HLF undergoes fusions with the E2A gene, resulting in chimeric E2a-Hlf proteins containing the E2a transactivation domains and the Hlf bZIP DNA binding and dimerization motifs. To investigate the in vivo role of this chimeric bZIP protein in oncogenic transformation, its expression was directed to the lymphoid compartments of transgenic mice. Within the thymus, E2a-Hlf induced profound hypoplasia, premature involution, and progressive accumulation of a T-lineage precursor population arrested at an early stage of maturation. In the spleen, mature T cells were present but in reduced numbers, and they lacked expression of the transgene, suggesting further that E2a-Hlf expression was incompatible with T-cell differentiation. In contrast, mature splenic B cells expressed E2a-Hlf but at lower levels and without apparent adverse or beneficial effects on their survival. Approximately 60% of E2A-HLF mice developed lymphoid malignancies with a mean latency of 10 months. Tumors were monoclonal, consistent with a requirement for secondary genetic events, and displayed phenotypes of either mid-thymocytes or, rarely, B-cell progenitors. We conclude that E2a-Hlf disrupts the differentiation of T-lymphoid progenitors in vivo, leading to profound postnatal thymic depletion and rendering B- and T-cell progenitors susceptible to malignant transformation.

Chromosomal translocations constitute important mechanisms for the activation of cellular oncogenes in human cancers (29). Many translocations in hematologic and soft tissue tumors result in the creation of fusion genes that encode chimeric transcriptional proteins (8). The modular nature of transcription factors renders them particularly susceptible to activation by the illicit shuffling of functional domains induced by chromosomal translocations. The resulting chimeric proteins frequently display altered transcriptional properties compared to their wild-type counterparts and in some cases have been shown to contribute to the perturbed expression of critical subordinate genes.

A recurring target for translocations in a subset of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALL) is the E2A gene (16), which codes for differentially spliced members (E12, E47, ITF1) of the basic helix-loop-helix family of E-box DNA binding proteins (4). As a result of t(1;19) or t(17;19) translocations, E2A is juxtaposed with heterologous genes, resulting in the production of either E2A-PBX1 or E2A-HLF fusion genes, respectively (13). E2A-HLF fusion products were originally isolated from two t(17;19)-carrying ALL cell lines (12, 19) with features of early B-lineage precursors. Two types of DNA rearrangement (15) result in the production of E2a-Hlf chimeric proteins containing the transactivation domains of E2a (2, 38) and the DNA binding and dimerization domains (basic region and leucine zipper) of Hlf (12, 19). The resulting E2a-Hlf proteins bind to a consensus palindromic DNA site as homodimers in vitro and are capable of activating the transcription of synthetic reporter genes through this site in transient transcriptional assays (14, 20). These properties of E2a-Hlf are essential for its ability to transform NIH 3T3 cells (22, 45), indicating that in this context E2a-Hlf acts through a gain-of-function mechanism as a homodimeric transcriptional activator.

E2a-Hlf is capable of modulating cell survival, a property with potential implications for its mechanisms of oncogenic action. Conditionally expressed E2a-Hlf prevents apoptosis associated with cytokine withdrawal from interleukin-3 (IL-3)-dependent Baf3 cells (21). The survival mechanism may involve E2a-Hlf cross-regulation of transcriptional regulatory elements normally mediated by NFIL-3, since both bind the same enhancer sequences and upon forced expression bypass the IL-3 requirement for survival of pro-B cells (18). Furthermore, dominant-negative disruption of E2a-Hlf in t(17;19)-bearing cells results in their apoptosis (21). The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain of Hlf displays similarity with that of Ces-2, a regulator of apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans (33); however, the potential role of wild-type Hlf in cell death pathways remains undefined. Hlf, but not Ces-2, is a member of the PAR subfamily of bZIP proteins that is distinguished by a proline- and acidic amino acid-rich (PAR) domain that flanks the basic region and contributes to DNA binding specificity (14). As a homodimer or heterodimer with other PAR family members, Hlf functions as a transcriptional activator, albeit with DNA binding and effector properties that differ modestly from those of E2a-Hlf which lacks the PAR domain (12, 14, 17, 20, 36). Since Hlf normally displays a highly restricted expression profile that excludes lymphoid cells, a potential model for its role in oncogenesis invokes ectopic expression as a fusion protein under the control of the constitutive E2A promoter, resulting in the corruption of transcriptional pathways that regulate survival in B-cell progenitors.

We report here the effects of E2a-Hlf on primary lymphoid progenitors in transgenic mice. Within the thymus, high-level E2a-Hlf expression disrupted normal differentiation, resulting in profound hypoplasia, premature involution, and progressive accumulation of a T-precursor population arrested at an early stage of maturation. In contrast to T cells, mature B cells expressed E2a-Hlf but at reduced levels and without apparent effects on their survival. A majority of E2A-HLF transgenic mice succumbed to T- or occasionally B-lineage lymphoblastic malignancies with a mean latency of 10 months. We conclude that high-level E2a-Hlf expression impedes the differentiation of T-lineage lymphoid progenitors in vivo and renders them highly susceptible to malignant transformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.

An E2A-HLF cDNA encoding the mRNA (12) expressed in t(17;19)-bearing cell line HAL-01 (37) was cloned downstream of the Eμ enhancer/simian virus (SV40) promoter in the vector EμSV (26). The entire insert was released from the vector backbone by NotI digestion and purified from agarose gels. Transgenic animals were generated by standard methods (11) for pronuclear injection of FVB/N fertilized eggs, using linear insert DNA (5 μg/ml in 10 mM Tris–0.2 mM EDTA). Surviving eggs were transferred 2 to 4 h after injection into oviducts of pseudopregnant CD-1 host females. Transgenic progeny were identified by Southern blotting, and transgene-positive lines were propagated by mating to FVB/N inbred mice. Two lines (10 and 11) were used for all of the studies described in this report and were indistinguishable in their characteristics.

DNA and protein analyses.

DNA was isolated from fresh or frozen tissues, digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization using previously reported methods (7). Probes for the mouse T-cell receptor (TCR) Jβ2, IGH-JH4, and IG-Jκ5 have been described previously (9). Protein extracts were prepared by lysing cells or tissues in 1× sample buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and boiling for 10 min. The lysates were sonicated and the optical density at 280 nm was determined. Fifty-microgram aliquots of total cellular protein were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Western blot analysis using an anti-E2a monoclonal antibody (24) as previously described (39). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection method as specified by the manufacturer (Amersham International plc, Amersham, England).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

Freshly isolated cells from bone marrow, thymus, spleen, and peripheral blood were stained for four-color analysis, and the fluorescence was analyzed by using a dual-laser FACS Vantage (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, Calif.) with a four-decade logarithmic amplifier. Dead cells were detected by staining with propidium iodide (1 μg/ml) and gated out electronically. Residual erythrocytes were also gated out electronically. Specific cell populations were sorted by gating on the desired populations, which were collected for analysis and Western blotting. Apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis following staining of thymocytes with annexin V and propidium iodide. All antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen Research Products (San Diego, Calif.). Specificities of antibodies were as follows: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated 145-2C11 (anti-CD3ɛ); phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated RM4-5 (anti-CD4); biotinylated 53-6.7 (anti-CD8α); FITC-conjugated S7 (anti-CD43); allophycocyanin-conjugated RA3-6B2 (anti-B220); PE-conjugated M1/69 (anti-CD24–heat-stable antigen); biotinylated 6C3/BP1 (anti-Ly51); avidin-conjugated Texas red; FITC-conjugated 2B8 (anti-CD117/c-Kit); and biotinylated 7D4 (anti-CD25α/p55).

Histology and immunohistochemical analyses.

Tissues for light microscopy were processed for paraffin embedding following fixation in 10% buffered formalin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard procedures. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed on frozen tissues according to previously published procedures (5), using rat monoclonal antibodies against mouse lymphoid differentiation antigens.

RESULTS

Construction of transgenic mice that express E2a-Hlf in lymphoid compartments.

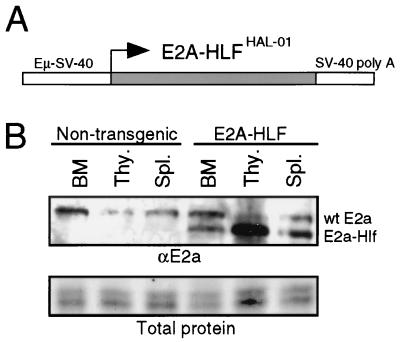

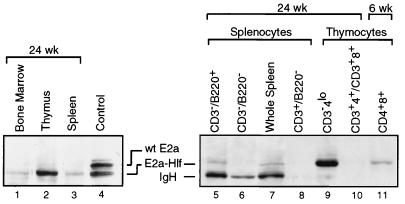

A transgene construct was created by using an E2A-HLF cDNA encoding the t(17;19) fusion mRNA (12) expressed by pro-B ALL cell line HAL-01 (37). It was cloned downstream from the SV40 promoter and IGH enhancer (Eμ) in the EμSV vector (Fig. 1A), which has been shown in previous studies to drive transgene expression in cells of both the B- and T-lymphoid lineages (26). The construct was injected into FVB/N embryos, and five founders were obtained, all of which showed germ line transmission of the transgene. Two independent lines with expression of the transgene in lymphoid compartments were selected for further studies. By Western blot analysis, immunoreactive proteins with migrations corresponding to that of E2a-Hlf were most prominently detected in the thymus and to a lesser extent in the spleen and bone marrow (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Structure and expression of the E2A-HLF transgene. (A) Schematic illustration of the E2A-HLF transgene construct consisting of the E2A-HLFHAL-01 cDNA driven by an Eμ enhancer and SV40 early promoter. (B) Expression of E2a-Hlf protein in bone marrow (BM), thymocytes (Thy.), and spleens (Spl.) of transgenic mice at 16 weeks of age as determined by Western blot analysis using an anti-E2a monoclonal antibody. Nontransgenic control mice displayed no E2a-Hlf expression. Gel loadings were standardized based on total protein content (lower panel). wt, wild type.

Lymphoid hypoplasia and rapid thymic involution in E2A-HLF mice.

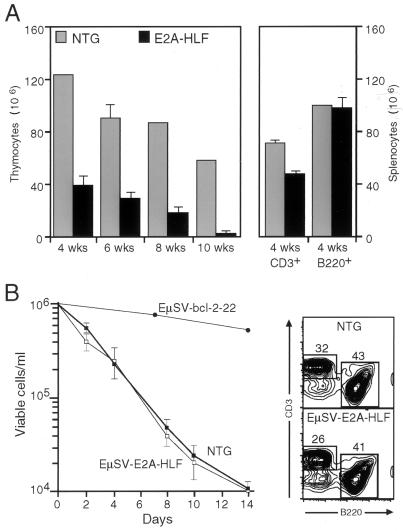

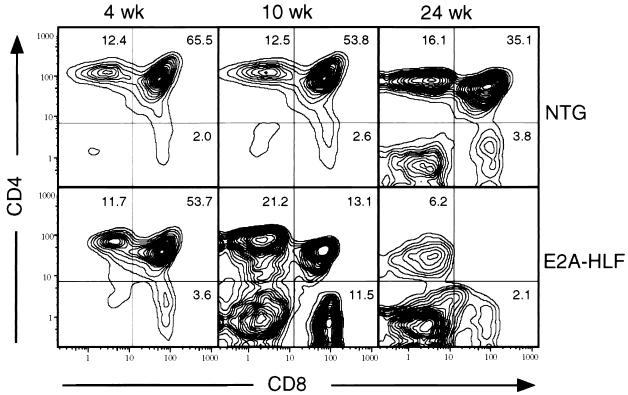

Healthy-appearing transgenic and normal animals were examined between 4 and 24 weeks of age to assess lymphocyte numbers and surface phenotypes by flow cytometry. At all time points, thymuses from transgenic animals were noted to be substantially smaller on gross examination, and this corresponded to lower total numbers of thymocytes than in controls (Fig. 2A). At 4 and 6 weeks, thymuses from E2A-HLF mice contained approximately 30% of the cells as normal littermates; at 8 and 10 weeks, transgenic thymocytes had dropped to 20 and 10%, respectively, of control levels. Total splenic T-cell numbers (CD3+) were also reduced (70% of control levels), suggesting that the hypoplasia involved the entire T-cell lineage (Fig. 2A). Although small in size, transgenic thymuses appeared histologically normal at 4 weeks, with formation of distinct cortical and medullary zones and no detectable increase in apoptosis (data not shown). By FACS analysis, the decrease in thymocyte numbers appeared to affect all thymocyte subpopulations equally since the percentages of phenotypically immature CD4+8+ cells as well as the phenotypically mature CD4+8− and CD4−8+ subsets were not significantly different between normal and transgenic animals (Fig. 3). However, at 10 weeks, the relative proportion of immature CD4+8+ thymocytes was substantially reduced (13% in transgenic mice versus 54% in control mice) compared to mature subsets (Fig. 3), reflecting a preferential loss of the double-positive (DP) population. By 24 weeks, both immature and mature populations were markedly affected. Essentially no CD4+8+ cells were evident, and only 8% of cells in thymuses from E2A-HLF mice expressed one or both of the CD4 and CD8 differentiation antigens, compared to 55% in normal mice. Based on these studies, E2A-HLF mice appeared to form a T-lymphoid compartment, but it was severely hypoplastic and over a period of several months underwent further marked decline, with loss of mature and immature thymocytes exceeding the physiologic involution associated with normal aging.

FIG. 2.

Thymic hypoplasia and rapid involution in E2A-HLF mice. (A) Total cell numbers were determined on viable cell suspensions of thymuses (left) from transgenic and nontransgenic (NTG) littermates at the indicated ages. Numbers of splenocytes (right) expressing B220 or CD3 were determined by FACS at 4 weeks of age. Results represent the average and standard deviations of determinations from four to six transgenic or two to four nontransgenic animals at each time point. (B) Spleen cells (16 weeks of age) were cultured at a density of 106 cells/ml in normal tissue culture medium without addition of cytokines or mitogens. The number of viable cells was determined by microscopy using a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion. Data are means and standard deviations of triplicate determinations from three animals in each cohort (open boxes, E2A-HLF mice; filled boxes, nontransgenic mice). The data for EμSV-bcl-2-22 (filled circles) are from reference 41. FACS analysis of splenocytes prior to explantation showed a modestly skewed B/T ratio in E2A-HLF mice. Numbers indicate percentages of cells in each phenotypic subset.

FIG. 3.

FACS analysis of premalignant thymocytes from E2A-HLF mice and their nontransgenic (NTG) littermates. Two-color contour plots show expression of CD4 and CD8 in thymocytes from mice at different ages (indicated at the top). Progressive loss of CD4+8+ DP and then SP thymocytes is observed in E2A-HLF mice. Numbers indicate percentages of cells in each phenotypic subset.

B-cell development was also assessed by FACS analysis, given that transgene expression was observed in the bone marrow. Total B-cell (B220+) numbers in the spleen (Fig. 2A) did not differ between transgenic and control mice. Analysis of B-cell differentiation antigens (CD43, CD24, and BP1) showed that the percentages of immature and mature B cells in the bone marrow were comparable to those in normal littermates (data not shown), indicating that there was not a block in B-cell differentiation or preferential survival of specific subpopulations. Splenocytes from E2A-HLF mice at 16 weeks showed a modestly increased B/T-cell ratio by FACS analysis (Fig. 2B) but did not display enhanced survival in vitro following their explantation (Fig. 2B).

Progressive expansion of a primitive thymocyte subpopulation in E2A-HLF mice.

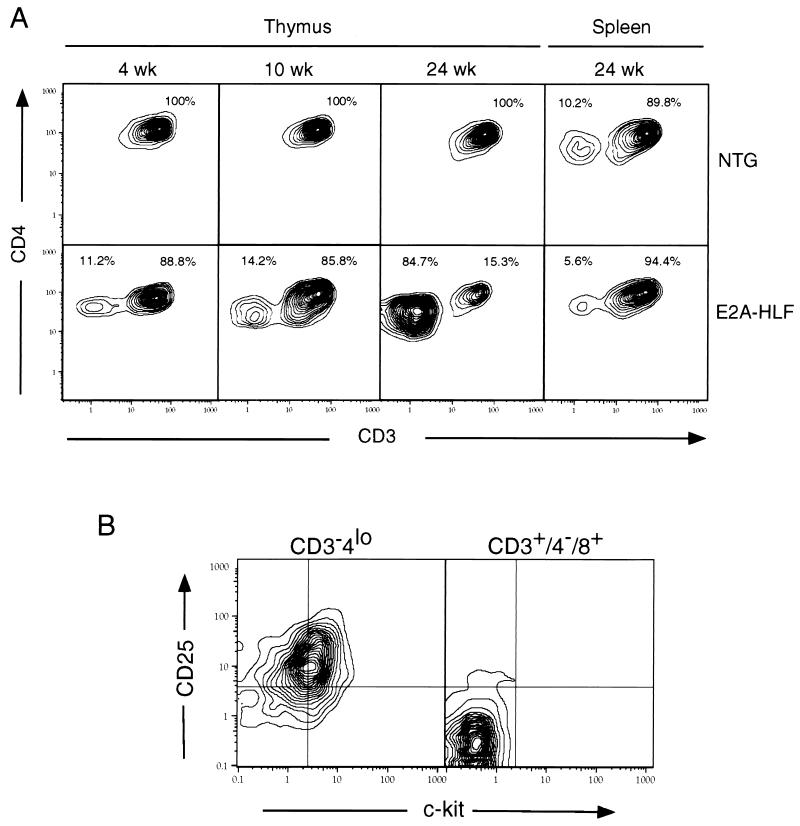

In addition to the rapid thymic involution observed in E2A-HLF mice, a proportion of cells remaining in the thymus at 24 weeks displayed an atypical phenotype. In E2A-HLF mice, most of the CD4+ thymocytes expressed a lower level of surface CD4 compared to the high levels present on single-positive CD4+8− thymocytes in nontransgenic littermates (Fig. 3). Single-positive (SP; CD4+8− and CD4−8+) thymocytes typically represent late-stage thymocytes that also coexpress high levels of the TCR-associated protein CD3 and upon final maturation exit the thymus to enter immunologically reactive sites such as lymph nodes and the spleen. In E2A-HLF mice, however, FACS analysis showed that the majority of CD4+ thymocytes at 24 weeks lacked coexpression of CD3 (Fig. 4A). Nearly 85% of cells in the CD4+ compartment consisted of this phenotypically atypical subpopulation characterized as CD3−4lo8−. These cells also expressed low levels of the progenitor cell antigens c-Kit and CD25 (Fig. 4B) and lacked detectable TCR β-chain expression (not shown). This phenotype is similar to that of an early progenitor that constitutes a very minor subpopulation in the normal thymus, consistent with our inability to detect a comparable population in nontransgenic controls (Fig. 4A). In E2A-HLF mice, however, CD3−4lo8− cells were detected at all time points including 4 weeks, when they constituted about 11% of the CD4+ subset. Animals between 10 and 24 weeks showed varying proportions of these phenotypically distinctive cells, suggesting that they were progressively and preferentially accumulating with increasing age (Fig. 4A). As determined by their forward light scatter characteristics, CD3−4lo8− cells were the size of small thymocytes (data not shown), suggesting a low proliferation index consistent with their slow accumulation. They also appeared to be confined to the thymus, since CD3−4lo8− cells could not be detected in comparable analyses of the spleen (Fig. 4A). FACS analysis showed that splenic T-cell populations were relatively similar in their subset distributions for transgenic and control littermates at all time points (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Expansion of a primitive thymocyte population in E2A-HLF transgenic mice. (A) Two-color contour plots of CD4 and CD3 expression in CD4+ gated thymocytes or splenocytes from mice at different ages show accumulation of a CD3−4lo population in thymuses of transgenic but not normal mice. A similar population is not detected in the spleen at 24 weeks. (B) Two-color contour plots demonstrating that CD3−4lo gated thymocytes express low levels of c-Kit and CD25. CD3+8+ thymocytes from same transgenic animal served as a negative control.

E2a-Hlf arrests thymocyte differentiation.

The presence and progressive accumulation of a primitive thymocyte population in E2A-HLF mice but not in normal littermates strongly suggested a direct effect of transgene expression on early progenitors. The identity of cells expressing E2a-Hlf was more directly addressed by purification of specific subsets by using cell sorting followed by Western blot analysis. The CD3−4lo8− progenitor population purified from thymuses at 24 weeks expressed high levels of E2a-Hlf (Fig. 5, lane 9). In contrast, mature SP thymocytes coexpressing CD3 from the same thymus lacked detectable expression of E2a-Hlf (Fig. 5, lane 10). Furthermore, purified CD3+ splenocytes from 24-week E2A-HLF mice also lacked E2a-Hlf detectable by sensitive Western blot analysis (lane 8), indicating that mature T cells that had exited the thymus did not express the transgene. Transgene expression could not be examined in thymocytes at an intermediate stage of differentiation (CD3+4+8+) from 24-week-old animals since there were insufficient numbers of cells. However, the CD3+4+8+ population was purified at 6 weeks of age, prior to their complete loss, and shown to express E2a-Hlf but at substantially lower levels compared to CD3−4lo8− cells (Fig. 5, lane 11). Therefore, the expanding progenitor population expressed high-level E2a-Hlf, but T-lineage cells that had progressed beyond this point showed either low or no E2a-Hlf expression. Taken together, these data suggested that high-level E2a-Hlf expression was incompatible with normal T-cell differentiation, leading instead to maturation arrest at the progenitor stage.

FIG. 5.

Expression of E2a-Hlf within various lymphoid populations purified by flow sorting from E2A-HLF mice at 6 and 24 weeks of age. Identities and sources of the cell populations are indicated above the gel lanes. Western blot analysis was performed with an anti-E2a monoclonal antibody (24). Extracts from equal numbers of cells were loaded per gel lane. The control lane contains extract from transiently transfected cells expressing wild-type (wt) and chimeric E2a proteins of human origin. Wild-type E2a proteins were not detected in most lanes due to minimal cross-reactivity of the YAE antibody with mouse E2a proteins (24) at the low amounts of protein available for analysis.

Although the foregoing analyses demonstrated that T cells resident in the spleen lacked expression of E2a-Hlf, Western blot analysis detected E2a-Hlf protein in unfractionated splenocytes isolated from 4- and 24-week-old animals (Fig. 1 and 5, lanes 3 and 7). The source of this protein was investigated by additional flow sorting of splenocytes. Most of the E2a-Hlf protein was found in the fraction of cells that expressed the B-lineage antigen B220 (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 8). Therefore, in contrast to T cells, B-lineage cells in the spleen expressed the transgene although at levels lower than that observed in the CD3−4lo8− thymic progenitor population.

E2A-HLF transgenic mice develop lymphoid malignancies of diverse phenotypes.

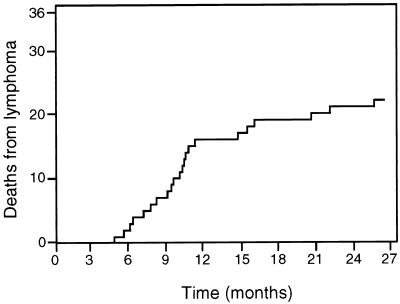

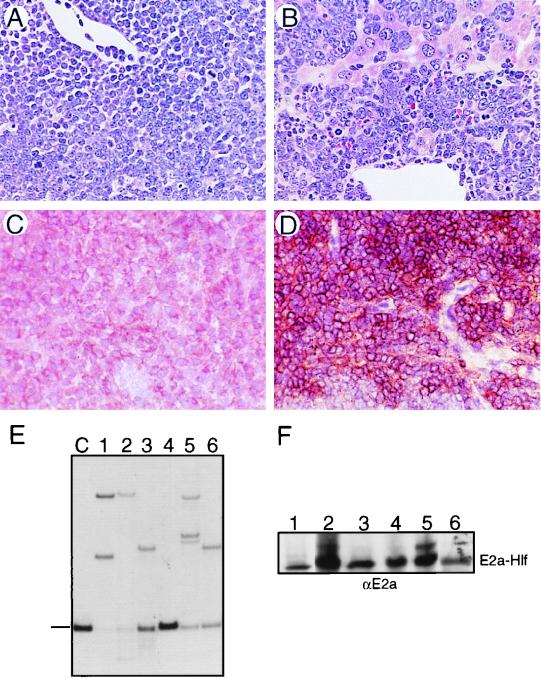

E2A-HLF transgenic mice displayed increased mortality starting at about 6 months of age due to development of lymphoid tumors. In a cohort of 36 transgenic animals maintained over a period of 2 years, 60% (22 animals) succumbed to tumors with a mean latency of 10 months (Fig. 6). An additional eight animals in this cohort died of unknown causes with no evidence of tumor. No deaths from tumors were observed in a comparable cohort of nontransgenic littermates. Tumor-bearing animals frequently presented with tachypnea reflective of thymic enlargement and associated mediastinal compression. Histologically, all tumors displayed the features of diffuse lymphomas comprised of medium to large cells with round, eccentric nuclei containing prominent nucleoli (Fig. 7A). Generalized lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly were commonly present due to tumor infiltration that was apparent on microscopic examination of these and other organs (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 6.

Tumor development in E2A-HLF mice. The mortality for a cohort (n = 28 animals) of E2A-HLF mice is shown over the 27-month observation period. Deaths were the result of malignant lymphoma confirmed by histologic examination. No deaths from lymphoma were observed in a comparable cohort of normal littermates.

FIG. 7.

Histologic and molecular features of tumors arising in E2A-HLF transgenic mice. (A and B) Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for thymic tumor and liver infiltrated by lymphoma, respectively (magnification, ×36). (C and D) Immunohistochemical analyses showing CD3 and B220 expression in two different thymic and nodal tumors, respectively. (E) Southern blot analysis of TCR gene rearrangements in lymphomas. Dash indicates migration of the germ line band. Lanes: C, germ line control; 1 to 3, 5, and 6, T-lineage tumors; 4, B-lineage tumor. (F) Western blot analysis showing expression of E2a-Hlf in lymphomas (lanes 1 to 5, T lineage; lane 6, B lineage).

Tumors were phenotyped by FACS or immunohistochemistry to assess cellular origin and extent of differentiation (Fig. 7C and D; Table 1). Most tumors consisted of T-lineage cells since they expressed CD3, although the mean fluorescence intensity varied from low to intermediate levels that were less than the high levels typically found on normal SP CD4+8− or CD4−8+ thymocytes. Tumors expressing CD3 also invariably coexpressed CD4 and CD8, although they were occasionally heterogeneous with respect to the intensity of CD4 or CD8 expression. The phenotypes were consistent with a mid-thymocyte stage of differentiation and in some cases were similar to that of transitional intermediates (CD3med4+8+). No tumors displayed a phenotype comparable to that of the primitive CD3−4lo8− population. Gene rearrangement analyses demonstrated that the T-lineage lymphomas were mono- or oligoclonal based on the presence of one or several non-germ line bands detected with TCR Jβ2 probes in each tumor (Fig. 7E). Monoclonality was further evidenced by analysis of tissues from two different sites in single animals which revealed the same configurations of rearranged bands (not shown). Western blot analyses of tumor tissues demonstrated high-level expression of E2a-Hlf (Fig. 7F). Approximately 10% of tumors expressed the pan-B-cell antigen B220 in the absence of CD3, CD4, or CD8, indicative of an origin in the B-cell lineage (Fig. 7D; Table 1). B220+ tumors generally displayed germ line configurations of IGH and TCR genes, suggesting that they arose from very early in the B-cell lineage. Taken together, these data demonstrated that E2A-HLF mice were highly predisposed to development of tumors originating from early within the T- or occasionally the B-lymphoid lineage.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of tumors arising in E2A-HLF transgenic mice

| Animal | Sexa | Age (days) | Configurationb

|

Phenotypec | Lineage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jβ2 | IGH | |||||

| 10A2 | M | 445 | G | G | B220+ CD3−4−8− | B progenitor |

| 10G2-C2 | M | 247 | 1R | G | B220− CD3+4+8+/− | Mid-thymocyte |

| 10G2-F2 | M | 275 | 1R | G | B220− CD3m4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 10F-M2 | M | 302 | 2R | G | B220− CD3m4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 10a-I3 | F | 430 | 1R | G | B220− CD3lo4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 10b-E3 | F | 373 | 3R | G | B220− CD3lo4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 10c-A3 | F | 398 | G | G | B220+ CD3−4−8− | B progenitor |

| 11E1-K1 | M | 292 | 2R | G | B220−d CD3+4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 11E1-A2 | F | 347 | 2R | G | B220−d CD3+4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 11E1-H3 | F | 292 | 2R | G | B220−d CD3+4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 11G-F1 | F | 218 | 2R | G | B220− CD3lo4+8+ | Mid-thymocyte |

| 11-7.1 | M | 264 | G | 1D | B220+e | B progenitor |

M, male; F, female.

G, germ line configuration; R, rearranged band; D, deleted allele.

−, negative staining; +, positive staining; m, intermediate-level staining; lo, low-level staining.

Phenotype determined by immunohistochemistry on frozen tissue sections.

Expression determined by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

These studies identify a novel property of E2a-Hlf that is likely to have important implications for its role in the pathogenesis of human leukemias. When directed to the lymphoid compartments of transgenic mice, E2a-Hlf displayed a potent capacity to antagonize the differentiation of T-lymphoid progenitors in vivo and render them highly susceptible to malignant transformation. High-level E2a-Hlf expression was clearly incompatible with normal thymocyte maturation, but we cannot rule out the possibility that it might have also contributed to enhanced survival of a subset of primitive thymocytes that progressively accumulated in E2A-HLF mice. Conversely, lower levels of E2a-Hlf expression appeared to be tolerated by B cells without adverse effects on their differentiation. Notably, at these levels of expression, E2a-Hlf did not appear to measurably enhance the survival of mature or immature B-lymphoid lineage cells. Following latencies of at least 6 months, T- and to a lesser extent B-lineage progenitors were prone to development of malignancies that expressed high levels of the transgene.

Initial examination of E2A-HLF mice showed severe decreases in thymocyte numbers compared to control littermates. This was evident as a rapidly evolving hypoplasia with over 90% involution of transgenic thymuses by 24 weeks of age. The most affected cells were the immature DP thymocytes. Normally, this population undergoes a vigorous selection process based on TCR affinity toward recognized self antigens in which unselected cells undergo apoptotic death and survivors mature to ultimately exit the thymus and establish the peripheral T-cell pool. E2a-Hlf did not enhance the survival of DP thymocytes but, rather, induced their preferential loss. With the loss of this maturing population, there was a subsequent decrease in the mature SP CD4+8− and CD4−8+ cells in transgenic thymuses at later time points. Immature DP but not SP cells expressed E2a-Hlf, indicating that E2a-Hlf expression and thymocyte maturation were incompatible. Consistent with this conclusion, mature T cells isolated from the spleen also did not express E2a-Hlf, indicating that the peripheral T-cell compartment was composed of lymphocytes (in reduced numbers) that had silenced the transgene by unknown mechanisms.

The thymic abnormalities in E2A-HLF mice are similar to those observed in mice harboring deficiencies of apoptosis regulatory proteins that play important roles in negative selection of thymocytes. Premature loss of the DP thymocyte population occurs in mice nullizygous for the death-repressing proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL (25, 31, 35, 42). These mice also display a concomitant loss of the majority of peripheral mature SP T cells. Decreased numbers of SP T cells are also seen in transgenic mice ectopically expressing the death-promoting molecule Bax, while DP thymocytes are increased in number (6). A possible mechanism, therefore, for loss of DP thymocytes in E2A-HLF mice could be mediated through effects on these apoptosis regulatory genes. However, we detected no differences in their expression in E2A-HLF transgenic thymuses compared with control littermates (40). Disruption of T-cell homeostasis and malignant transformation also occurs in the thymus following inactivating mutations of the E2A gene. Previous studies have demonstrated partial loss of the DP population and thymic tumors in E2A nullizygous mice (3, 44). These studies suggest that perturbation of E2a-regulated transcriptional pathways in the thymus has developmental and oncogenic consequences and that thymocyte transformation can occur through loss of function. It is unclear how much, if any, of the thymic phenotype induced by E2a-Hlf can be attributed to disruption of E2a as opposed to Hlf pathways. Further resolution of this issue will require an analysis of mice expressing mutated forms of E2a-Hlf and/or dominant-negative forms of E2a.

E2a-Hlf expression, per se, did not appear to be incompatible with B-cell maturation. Nearly all of the E2a-Hlf expression within the spleen was accounted for by the B220+ mature B-lymphocyte population. However, the levels of expression were substantially below those observed in T-cell progenitors of the thymus. This is not easily explained by possible expression bias of the transgene construct, since the SV40 promoter/Eμ enhancer element is generally capable of expressing at high levels in both the B- and T-cell compartments. We cannot rule out the possibility that B-cell progenitors with high-level E2a-Hlf expression were lost at early stages of differentiation, comparable to the fate of E2a-Hlf-expressing DP thymocytes. E2A-HLF mice did not develop hyperplastic B-cell proliferations in the absence of tumors, and splenic B lymphocytes did not display alterations in their survival properties. Although the absence of perturbations in survival may reflect low-level transgene expression in mature B cells, progenitor B-lineage tumors that developed in E2A-HLF mice also did not display enhanced in vitro survival in spite of high-level transgene expression. Therefore, we observed no in vivo correlate of the previously reported ability of E2a-Hlf to protect IL-3-dependent Baf3 cells from cell death induced by cytokine withdrawal in vitro (21). The mechanistic basis for the latter may involve transcriptional deregulation of subordinate target genes by E2a-Hlf that are shared with cytokine transcriptional regulators like NFIL-3 (18). However, recent studies show that survival elicited by E2a-Hlf does not require the DNA binding and dimerization motifs of Hlf (23). Alterations in survival, therefore, may reflect dominant-negative perturbations in transcriptional programs that are dependent on E2a and not primarily subordinate to Hlf.

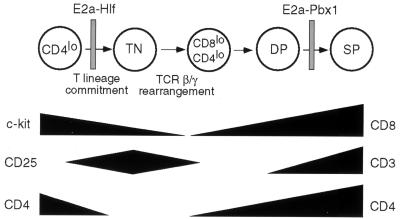

In addition to the rapid thymic involution observed in E2A-HLF mice, there was concomitant emergence of an immature T-cell population. This CD4lo8−3− (CD4lo) population, which increased from 11 to 85% of total CD4+ thymocytes by 6 months of age, was phenotypically similar to progenitor cells that have been identified in the normal developing murine thymus (43). These native progenitors are multipotent in their abilities to reconstitute cells of T and B lineages as well as dendritic cells in vivo (1, 34). Because of their limited numbers, we could not further address the potential relationship of CD4lo cells in E2A-HLF mice with native progenitors. Our studies, however, are consistent with an E2a-Hlf-imposed developmental block at the CD4lo stage (Fig. 8) due to high-level expression of the E2a-Hlf protein. Recent studies suggest a role for Hlf in the developing mammalian nervous system (10a). Thus, its ectopic expression following fusion with E2a may perturb developmental programs that are normally quiescent in the lymphoid compartment leading to thymocyte developmental arrest. While our findings reveal a previously unrecognized role for E2a-Hlf, they are consistent with the abilities of other lymphoid oncogenes to disrupt thymocyte differentiation. For example, thymocytes from E2A-PBX1 mice are arrested at a transitional intermediate stage of thymocyte differentiation (CD4+8+3med) and rapidly progress to overt lymphomas (9). Furthermore, transgenic mice ectopically expressing the oncogenes LMO1/RBTN1/TTG1 (32), LMO2/RBTN2 (27), TAL-1 (28), or HOX11 (10) manifest perturbations in thymocyte differentiation and succumb to T-cell tumors.

FIG. 8.

Schematic illustration of thymocyte maturational arrest induced by E2A transgenes. The profile of thymocyte differentiation is based on the data of Moore and Zlotnik (34). Vertical bars denote stages of maturational arrest in E2A-HLF and E2A-PBX1 mice, respectively. Temporal expression profiles for selected surface antigens are shown below. TN, triple negative.

Over 60% of E2A-HLF transgenic mice developed lymphoid malignancies with a mean latency of 10 months, demonstrating the in vivo oncogenic capacity of E2a-Hlf. Occasional tumors displayed characteristics of B-lineage progenitors, the cell type targeted by E2a-Hlf in pediatric ALL. However, similar to the E2A-PBX1 chimeric oncogene, E2A-HLF clearly favored development of T-lineage tumors in transgenic mice, in spite of their consistent associations with B-lineage progenitor leukemias in humans. The basis for targeted transformation of developing thymocytes is unknown but is consistent with a generally lower oncogenic threshold of murine thymocytes, a predisposition potentially rendered by the complexity of genetic changes that normally occur during TCR gene recombinations in developing a functional repertoire. Within the T-lineage compartment, however, the two E2A chimeric genes display measurable differences in their propensities to target specific subpopulations. In premalignant mice, E2a-Hlf resulted in the outgrowth of very early (CD4lo) progenitors whereas E2a-Pbx1 targeted more differentiated transitional intermediates (Fig. 8). Although we cannot rule out variability attributable to regulatory elements of the transgenes or their sites of integration, the differences mirror the association of E2a-Hlf and E2a-Pbx1 with B-lineage precursors that are characterized as pro-B (early)- and pre-B (later)-cell leukemias, respectively, in pediatric ALL. These similarities suggest potential stage-specific sensitivities of differentiating lymphocytes to perturbations in Pbx and Hlf transcriptional programs. Therefore, E2A-HLF transgenic mice should provide a useful model system for studying the maturational arrest induced by this oncogene in pediatric ALL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Carmencita Nicolas and Roxane Brown for expert technical support, Stephen Hunger for helpful discussions, and Mary Stevens for microinjections. We thank Phil Verzola and Beth Houle for photographic support.

This study was supported by funds from the NIH (CA42971 and CA34233), NIH training grants (CA09302 and AI-07290), a National Research Service Award (CA66284) to K.S.S., and fellowship funds from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to L.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardavin C, Wu L, Li C L, Shortman K. Thymic dendritic cells and T cells develop simultaneously in the thymus from a common precursor population. Nature. 1993;362:761–763. doi: 10.1038/362761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronheim A, Shiran R, Rosen A, Walker M D. The E2A gene product contains two separable and functionally distinct transcription activation domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8063–8067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain G, Engel I, Robanus Maandag E C, te Riele H P J, Voland J R, Sharp L L, Chun J, Huey B, Pinkel D, Murre C. E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in αβ T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4782–4791. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bain G, Murre C. The role of E-proteins in B- and T-lymphocyte development. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:143–153. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bindl J M, Warnke R A. Advantages of detecting monoclonal antibody binding to tissue sections with biotin and avidin reagents in coplin jars. Am J Pathol. 1986;85:490–493. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/85.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady H J, Gil-Gomez G, Kirberg J, Berns A J. Bax alpha perturbs T cell development and affects cell cycle entry of T cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:6991–7001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleary M L, Smith S D, Sklar J. Cloning and structural analysis of cDNAs for bcl-2 and a hybrid bcl-2/immunoglobulin transcript resulting from the t(14;18) translocation. Cell. 1986;47:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleary M L. Oncogenic conversion of transcription factors by chromosomal translocations. Cell. 1991;66:619–622. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dedera D A, Waller E K, LeBrun D P, Sen-Majumbar A, Stevens M E, Barsh G S, Cleary M L. Chimeric homeobox gene E2A-PBX1 induces proliferation, apoptosis, and malignant lymphomas in transgenic mice. Cell. 1993;74:833–843. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90463-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatano M, Roberts C W M, Kawabe T, Shutter J, Korsmeyer S J. Cell cycle progression, and cell death and T cell lymphoma in hox11 transgenic mice. Blood. 1992;80(Suppl. 1):335A. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Hitzler J K, Soares H D, Drolet D W, Inaba T, O’Connel S, Rosenfeld M G, Morgan J I, Look A T. Expression patterns of the hepatic leukemia factor gene in the nervous system of developing and adult mice. Brain Res. 1999;820:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan B, Constantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunger S P, Ohyashiki K, Toyama K, Cleary M L. Hlf, a novel hepatic bZIP protein, shows altered DNA-binding properties following fusion to E2A in t(17;19) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1608–1620. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunger S P, Cleary M L. Chimaeric oncoproteins resulting from chromosomal translocations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993;4:387–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunger S P, Brown R, Cleary M L. DNA-binding and transcriptional regulatory properties of hepatic leukemia factor (HLF) and the t(17;19) acute lymphoblastic leukemia chimera E2A-HLF. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5986–5996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunger S P, Devaraj P E, Foroni L, Secker-Walker L M, Cleary M L. Two type of genomic rearrangements create alternative E2A-HLF fusion proteins in t(17;19)-ALL. Blood. 1994;83:2970–2977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunger S P. Chromosomal translocations involving the E2A gene in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: clinical features and molecular pathogenesis. Blood. 1996;87:1211–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunger S P, Li S, Fall M Z, Naumovski L, Cleary M L. The proto-oncogene HLF and the related basic leucine zipper protein TEF display highly similar DNA-binding and transcriptional regulatory properties. Blood. 1996;87:4607–4617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikushima S, Inukai T, Inaba T, Nimer S D, Cleveland J L, Look A T. Pivotal role for the NFIL3/E4BP4 transcription factor in interleukin 3-mediated survival of pro-B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2609–2614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inaba T, Roberts W M, Shapiro L H, Jolly K W, Raimondi S C, Smith S D, Look A T. Fusion of the leucine zipper gene HLF to the E2A gene in human acute B-lineage leukemia. Science. 1992;257:531–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1386162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inaba T, Shapiro L H, Funabiki T, Sinclair A E, Jones B G, Ashmun R A, Look A T. DNA-binding specificity and trans-activating potential of the leukemia-associated E2A-hepatic leukemia factor fusion protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3403–3413. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inaba T, Inukai T, Yoshihara T, Seyschab H, Ashmun R A, Canman C E, Laken S J, Kastan M B, Look A T. Reversal of apoptosis by the leukaemia-associated E2A-HLF chimaeric transcription factor. Nature. 1996;382:541–544. doi: 10.1038/382541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inukai T, Inaba T, Yoshihara T, Look A T. Cell transformation mediated by homodimeric E2A-HLF transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1417–1424. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inukai T, Inaba T, Ikushima S, Look A T. The AD1 and AD2 transactivation domains of E2A are essential for the antiapoptotic activity of the chimeric oncoprotein E2A-HLF. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6035–6043. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs Y, Vierra C, Nelson C. E2A expression, nuclear localization, and in vivo formation of DNA- and non-DNA-binding species during B-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7321–7333. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudson C M, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2 and Bax function independently to regulate cell death. Nat Genet. 1997;16:358–363. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langdon W Y, Harris A W, Cory S, Adams J M. The c-myc oncogene perturbs B lymphocyte development in E-mu-myc transgenic mice. Cell. 1986;47:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson R C, Fisch P, Larson T A, Lavenir I, Langford T, King G, Rabbitts T H. T cell tumours of disparate phenotype in mice transgenic for Rbtn-2. Oncogene. 1994;9:3675–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson R C, Lavenir I, Larson T A, Baer R, Warren A J, Wadman I, Nottage K, Rabbitts T H. Protein dimerization between Lmo2 (Rbtn2) and Tal1 alters thymocyte development and potentiates T cell tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1996;15:1021–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Look A T. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science. 1997;278:1059–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Look A T. E2A-HLF chimeric transcription factors in pro-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;220:45–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60479-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma A, Pena J C, Chang B, Margosian E, Davidson L, Alt F W, Thompson C B. Bclx regulates the survival of double-positive thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4763–4767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGuire E A, Rintoul C E, Sclar G M, Korsmeyer S J. Thymic overexpression of Ttg-1 in transgenic mice results in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4186–4196. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metzstein M M, Hengartner M O, Tsung N, Ellis R E, Horvitz H R. Transcriptional regulator of programmed cell death encoded by Caenorhabditis elegans gene ces-2. Nature. 1996;382:545–547. doi: 10.1038/382545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore T A, Zlotnik A. T-cell lineage commitment and cytokine responses of thymic progenitors. Blood. 1995;86:1850–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motoyama N, Wang F, Roth K A, Sawa H, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Negishi I, Senju S, Zhang Q, Fujii S, Loh D Y. Massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 1995;267:1506–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.7878471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newcombe K, Glassco T, Mueller C. Regulation of the DBP promoter by PAR proteins and in leukemic cells bearing an E2A-HLF translocation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;17:633–639. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohyashiki K, Fujieda H, Miyauchi J, Ohyashiki J H, Tauchi T, Saito M, Nakazawa S, Abe K, Yamamoto K, Clark S C, Toyama K. Establishment of a novel heterotransplantable acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line with a t(17;19) chromosomal translocation the growth of which is inhibited by interleukin-1. Leukemia. 1991;5:322–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quong M W, Massari M E, Zwart R, Murre C. A new transcriptional-activation motif restricted to a class of helix-loop-helix proteins is functionally conserved in both yeast and mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:792–800. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith K S, Jacobs Y, Chang C-P, Cleary M L. Chimeric oncoprotein E2a-Pbx1 induces apoptosis of hematopoietic cells by a p53-independent mechanism that is suppressed by Bcl-2. Oncogene. 1997;14:2917–2926. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, K. S., J. W. Rhee, and M. L. Cleary. Unpublished observations.

- 41.Strasser A, Harris A W, Vaux D L, Webb E, Bath M L, Adams J M, Cory S. Abnormalities of the immune system induced by dysregulated bcl-2 expression in transgenic mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;166:175–181. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75889-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veis D J, Sorenson C M, Shutter J R, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, Scollay R, Egerton M, Pearse M, Spangrude G J, Shortman K. CD4 expressed on earliest T-lineage precursor cells in the adult murine thymus. Nature. 1991;349:71–74. doi: 10.1038/349071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan W, Young A Z, Soares V C, Kelley R, Benezra R, Zhuang Y. High incidence of T-cell tumors in E2A-null mice and E2A/Id1 double-knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7317–7327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshihara T, Inaba T, Shapiro L H, Kato J Y, Look A T. E2A-HLF-mediated cell transformation requires both the trans-activation domains of E2A and the leucine zipper dimerization domain of HLF. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3247–3255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]