Abstract

Purpose

Although a variety of analytical methods have been developed to detect mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) heteroplasmy, there are special requirements of mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification for women carrying mtDNA mutations receiving the preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and prenatal diagnosis (PD) in clinic. These special requirements include various sample types, large sample number, long-term follow-up, and the need for detection of single-cell from biopsied embryos. Therefore, developing an economical, accurate, high-sensitive, and single-cell analytical method for mtDNA heteroplasmy is necessary.

Methods

In this study, we developed the Sanger sequencing combined droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) method for mtDNA quantification and compared the results to next-generation sequencing (NGS). A total of seventeen families with twelve mtDNA mutations were recruited in this study.

Results

The results showed that both Sanger sequencing and ddPCR could be used to analyze the mtDNA heteroplasmy in single-cell samples. There was no statistically significant difference in heteroplasmy levels in common samples with high heteroplasmy (≥ 5%), low heteroplasmy (< 5%), and single-cell samples, either between Sanger sequencing and NGS methods, or between ddPCR and NGS methods (P > 0.05). However, Sanger sequencing was unable to detect extremely low heteroplasmy accurately. But even in samples with extremely low heteroplasmy (0.40% and 0.92%), ddPCR was always able to quantify them. Compared to NGS, Sanger sequencing combined ddPCR analytical methods greatly reduced the cost of sequencing.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study successfully established an economical, accurate, sensitive, single-cell analytical method based on the Sanger sequencing combined ddPCR methods for mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification in a clinical setting.

Keywords: Analytical methods, Mitochondrial DNA, Heteroplasmy, Preimplantation genetic diagnosis, Prenatal diagnosis

Introduction

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation may induce impaired mitochondrial function and cellular metabolic disturbance, which will bring about functional dysfunction of tissues and organs, generally defined as mitochondrial disease [1]. Multiple mitochondria are present in one cell, and several copies of mtDNA (ranging from dozens to thousands in different types of cells) are present in a single mitochondrion [2, 3]. Thus, a mix of mutant and wildtype mtDNA is usually observed in the clinic, termed mtDNA heteroplasmy. Due to the genetic segregation and bottleneck effects of mtDNA in germ cells, mothers carrying mtDNA mutations will transmit different levels of mutant mtDNA to offspring, which may lead to the onset of mitochondrial disease in offspring with high heteroplasmy levels. Mitochondrial replacement technology (MRT) is expected to completely block mtDNA transmission from mother to offspring [4, 5]. However, due to the ethical controversy and safety concerns of MRT, such as the “genetic drift” phenomenon existing in typical MRT, the application of MRT in clinical is still prohibited in the vast majority of the counties in the world [6–8]. Therefore, prenatal diagnosis (PD) and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are the only hope that women with mtDNA mutations are expected to obtain healthy offspring with biological relationships in the clinical application [9, 10].

Accurate quantification of mtDNA heteroplasmy by an appropriate analytical method in peripheral blood, tissues, and embryos is crucial during PD and PGD. In particular, we also need to analyze the mutation load in single-cell biopsied from embryos during PGD. And we have not only to determine the onset risk of mitochondrial disease, continuing pregnancy or not, or select the embryos with low mutant load for implantation based on heteroplasmy level of peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, tissues, and single-cell, but also to monitor long-term heteroplasmy variation after children birth. Therefore, establishing the analytical method for mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification is the cornerstone of PD and PGD in women with mtDNA mutations. Currently, the primary analytical method for heteroplasmy quantification is next-generation sequencing (NGS) [11, 12].

In this study, we developed the Sanger sequencing combined with droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) analytical methods to analyze the mtDNA heteroplasmy in seventeen families with mitochondrial disease with twelve mtDNA mutations. And then, we compared the results with traditional NGS results in common samples (≥ 5% heteroplasmy), low heteroplasmy samples (< 5% heteroplasmy), and single-cell samples (single-cell biopsied from embryos). As a result, Sanger sequencing combined ddPCR method could accurately quantify mtDNA heteroplasmy, and the obtained results generally agreed with the NGS results. We have established an economical, highly sensitive, accurate, and single-cell analytical method for mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification, laying the foundation for PD and PGD of these mitochondrial disease families.

Materials and methods

Blood, amniotic fluid, and tissues were obtained from patients in the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) were built in our lab. Single cell was biopsied from the embryo in our lab. All patients have signed the informed consent.

Genomic DNA extraction from blood, amniotic fluid, and tissues

Tissues were ground firstly, and then added with PBS to form the cell suspension. Six hundred microliters of cell lysates and 10 µL protease K were added to 200 µL blood, amniotic fluid, or cell suspension. The above-mixed suspension was incubated in 65 ℃ for 2 h. After incubation, 600 µL chloroform was added, then thoroughly mixed, and centrifuged for 10 min (12,000 r/min). The supernatant was aspirated and put into a new tube. Eighty percent volume of isopropanol was added into the new tube and sat quietly for 30 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 to 10 min (12,000 r/min). The supernatant was abandoned and the precipitate was left. Seven hundred microliters of 75% ethanol was added and centrifuged for 2 to 3 min (12,000 r/min). Then the ethanol was aspirated and the precipitate was leave to rest for 5 to 10 min. Finally, 30–40 µL buffer AE was added to dissolve the DNA precipitate.

Whole-genome amplification for biopsied cell samples from discarded embryos

Whole-genome DNA was amplificated using the REPLI-g single cell WGA kit (QIAGEN, Germany). First step: cell lysis and DNA denaturation of the samples. In general, biopsied cells were placed in 4 µL PBS and collected into microcentrifuge tubes, and if the total volume was less than 4 µL, PBS was added to reach 4 µL volume. At the same time, 1 µL 10 pg/µL human genomic DNA with 3 µL PBS was placed into a microcentrifuge tube and set as positive control. And 4 µL PBS without any DNA template was placed into a microcentrifuge tube and set as negative control. Then 36 µL buffer D2 (the total volume of buffer D2 was sufficient for 12 reactions, and buffer D2 should not be stored for more than 3 months) was made up by 3 μL 1 M DTT and 33 μL buffer DLB (reconstituted with nuclease-free water). Three microliters of buffer D2 was added into 4 µL of each sample, and then the mixture was incubated at 65 ℃ for 10 min. Finally, 3 µL stop solution was added to stop the denaturation step; second step: whole-genome amplification. Nine microliters H2O, 29 μL REPLI-g sc reaction buffer, and 2 µL REPLI-g sc DNA polymerase were mixed together to form 40 μL master mix. Then 40 µL master mix was added to each sample and incubated at 30 ℃ for 10 h (the lid temperature should be set at 70 ℃), and then incubated at 65 ℃ for 3 min to inactivate the REPLI-g sc DNA polymerase. The amplified DNA was stored at 4 ℃ for short-time preservation or − 20 ℃ for long-time preservation.

NGS

mtDNA amplification

The whole mitochondrial genome was amplified using TAKARA Long Range Kit (Takara, Japan). The forward primers were 2662F (5′-ACTTTTAACCAGTGAAATTGACCTGCC-3′) or 2120F (5′-GGACACTAGGAAAAAACCTTGTAGAGAGAG-3′). The reverse primers were 2661R (5′-AAGAGACAGCTGAACCCTCGTGG-3′) or 2119R (5′-AAAGAGCTGTTCCTCTTTGGACTAACA-3′). The PCR (50 μL) reaction: 10 µM forward primer 2 μL, 10 µM reverse primer 2 μL, 2.5 mM dNTP Mix 8 μL, 5 U/µL Takara LA Taq 0.5 μL, 10 × LA PCR buffer 5 μL, nuclease-free water 30.5 μL, and DNA template 2 μL. The PCR program: step 1: 95 ℃ for 2 min; step 2: 95 ℃ for 20 s, then 68 ℃ for 16 min, running 35 cycles for step 2; step 3: 68 ℃ for 20 min; step 4: 4 ℃ hold. One percent TBE agarose gel electrophoresis was running to verify the amplification of PCR products.

Library preparation

Whole mtDNA was broken into about 200-bp fragments first. The fragmented DNA was subjected to repair DNA end by a DNA end repairing agent. The previous repaired product was added into an adenine at the 3′ end under polymerase. The A-tailing end was connected to an adapter by T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher, USA). The ligated products were amplified by four to six rounds of ligation-mediated PCR. The PCR products were purified by the magnetic beads. The PCR products were sent for NGS (Chigene, China).

Library sequencing

The Novaseq6000 sequencing system (Illumina, USA) was used to perform paired-ended 150-bp sequencing. The clean data was obtained by quality control and removing poor quality data.

Data analysis

The sequencing data was aligned to the reference sequence NC_012920 (human complete mitochondrial genome 16,569-bp circular DNA). The mutation was obtained by matching in the MITOMAP database.

Sanger sequencing

PCR amplification

The target mtDNA fragments were amplified using GoTaq Colorless Master Mix (Promega, USA). The primers used for PCR amplification of different mtDNA mutations are listed in Table 1. The PCR reaction: 2 × GoTaq Colorless Master Mix 10 μL, 10 µM forward primer 1 μL, 10 µM reverse primer 1 μL, DNA template 2 μL, nuclease-free water 6 μL. The PCR program: step 1: 98 ℃ for 5 min; step 2: 98 ℃ for 10 s, then different annealing temperature according to a different set of primers for 15 s, and 72 ℃ for 30 s, running 34 cycles for step 2; step 3: 72 ℃ for 5 min; step 4: 4 ℃ hold.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of PCR amplification in Sanger sequencing method

| Mutations | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| m.1555 A > G | ATGAGGTGGCAAGAAATGGG | GGTGGAGTGGGTTTGGGGCT |

| m.3243 A > G | AGTAATCCAGGTCGGTTTCTATC | GCGTCAGCGAAGGGTTGT |

| m.3472 T > C | TCCTAATGCTTACCGAACGAA | ATGTAGAGGGTGATGGTAGATGTG |

| m.3635 G > A | GCCTCCTATTTATTCTAG | CACTTATTAGTAATGTTGAT |

| m.3697 G > A | TGCTTACCGAACGAAAAA | AGGTTAAAGGAGCCACTT |

| m.8344 A > G | AATGCTCTGAAATCTGTG | GGTGGTAGTTTGTGTTTA |

| m.8993 T > G | CCTGCCTCACTCATTTACACCA | GCGACAGCGATTTCTAGGATAG |

| m.9185 T > C | GCTGTCGCCTTAATCCAA | TAGGCCGGAGGTCATTAG |

| m.10158 T > C | TTTGTAGATGTGGTTTGA | TAGTTGTTTGTAGGGCTC |

| m.13513 G > A | AATAGTTACAATCGGCATC | TGTGAGTTTTAGGTAGAGG |

| m.14709 T > C | GAGAAGGCTTAGAAGAAAAC | AAGAGGCAGATAAAGAATAT |

PCR product purification

PCR products were then purified by the column method. In brief, 100 μL isopropanol and 10 μL NaA were added to the 20-μL PCR products. After fully shaking and mixing, the mixture was stood quietly for 1 min and then transferred into the column and stood quietly for another 5 min. The column was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 s and the waste liquid was discarded. The column was added with 600 μL ethanol, stood for 2 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 s. The wash step was repeated once again. Then, the column was put into a new tube, and added with 50 μL TE buffer solution, centrifuged for 2 min. The products were used as DNA template for sequencing.

Sequencing and data analysis

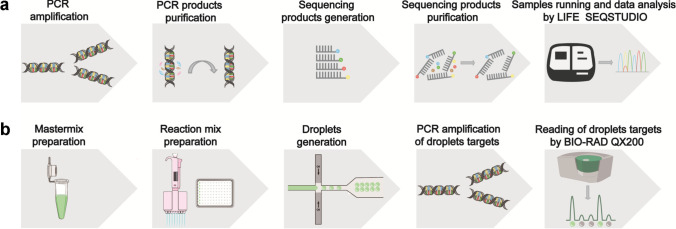

The sequencing PCR reaction: NovaDye Mix 0.3 μL, buffer 1.7 μL, forward primer or reverse primer 1 μL, DNA template 2 μL, nuclease-free water 5 μL. After sequencing product generation, the alcohol-EDTA-sodium acetate precipitation method was used to remove the remaining ddNTPs, dNTPs, ions, and sequencing enzymes. Then the purified sequencing products were loaded into the SeqStudio Cartridge. Soon afterward, the cartridge was plugged into LIFE SEQSTUDIO (Thermo Fisher, USA) to ran the samples. Minor Variant Finder software (Thermo Fisher, USA) was used to analyze the data by the end (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of Sanger sequencing and ddPCR analytical methods. a Illustration of the operation procedure of Sanger sequencing method by LIFE SEQSTUDIO. b Illustration of the operation procedure of ddPCR method by BIO-RAD QX200

ddPCR

Droplet preparation

The target mtDNA fragments were amplified using ddPCR Supermix for probes (BIO-RAD, USA). The primers and probes used for ddPCR amplification are listed in Table 2. The ddPCR amplification reaction: 2 × ddPCR Supermix 12.5 μL, 10 µM forward primer 1 μL, 10 µM reverse primer 1 μL, nuclease-free water 8.5 μL, DNA template 1 μL, probes 0.5 μL*2. The reaction mix was prepared and added into the microdroplet generation card. The microdroplet generation card was then put into the microdroplet generator. The microdroplet generator could divide each 20-μL reaction mix into 20,000 microdroplets in 2.5 min.

Table 2.

Primer sequences of PCR amplification and fluorescent probes in ddPCR method

| Mutations | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe (FAM) | Probe (VIC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m.3243 A > G | CCACACCCACCCAAGAACAG | GGGTATGTTGTTAAGAAGAGGAATTGA | TTTGTTAAGATGGCAGAGC | TTGTTAAGATGGCAGGGC |

| m.8993 T > G | GTTATTATCGAAACCATCAGCCT | AGTAGGTGGCCTGCAGTAATGT | CAATAGCCCTGGCC | CAATAGCCCGGGCC |

| m.9185 T > C | GCAATATCAACCATTAAC | TTAGTGTGTTGGTTAGTA | TAGTAAGCCTCTACCTGCA | TAGTAAGCCCCTACCTGCA |

| m.10191 T > C | CATAGAAAAATCCACCCCTTACGA | AGGAGGGCAATTTCTAGATCAAATAA | ACCCTATACCCCCCGCC | ACCCTATATCCCCCGC |

PCR amplification

The generated droplets were then transferred to a 96-well PCR plate (the operation action needs to be slow and gentle to avoid the destruction of the microdroplets) for amplification on the PCR instrument. The PCR program: step 1: 95 ℃ for 5 min; step 2: 95 ℃ for 30 s, then different annealing temperature according to different set of primers for 10 min, running 45 cycles for step 2; step 3: 98 ℃ for 10 min; step 4: 4 ℃ hold.

Sequencing and data analysis

The 96-well plate was put into the microdroplet analyzer (BIO-RAD QX200) (BIO-RAD, USA) after PCR amplification. The microdroplets of each sample were began to pass through the two-color detector one by one in the microdroplet analyzer. Microdroplets with a fluorescent signal were judged to be positive, while microdroplets without fluorescent signal were negative. The number of positive microdroplets in each sample was recorded by the QuantaSoft software (BIO-RAD, USA). Finally, the data was analyzed and displayed in the QuantaSoft software (Fig. 1b).

Statistical analysis

A T-test of two independent samples was used to analyze the data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Twelve mtDNA mutations in seventeen families with the mitochondrial disease were detected by Sanger sequencing or ddPCR analytical methods

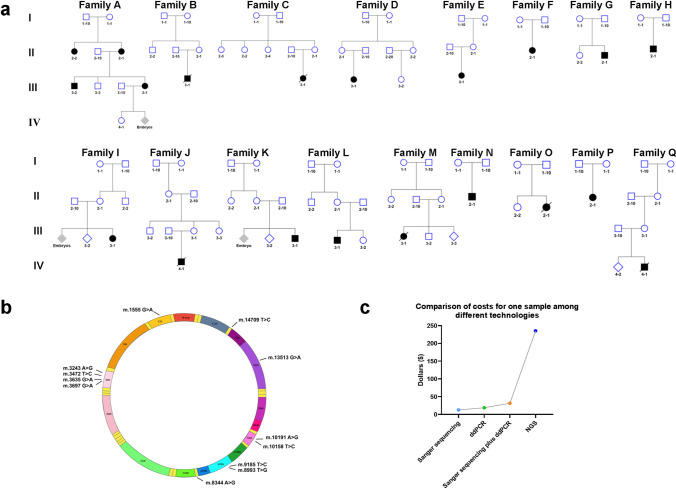

A total of seventeen families, one or several family members were diagnosed with mitochondrial disease, were recruited in this study (Fig. 2a). The proband in family A was diagnosed with hereditary hearing loss. The probands in families B, C, D, E, and F were diagnosed with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS). The probands in families G and H were diagnosed with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON). The proband in family J was diagnosed with myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF). The probands in families I, K, L, M, N, O, P, and Q were diagnosed with Leigh syndrome. A total of twelve previously reported pathogenic mutations were involved in these families. Among them, m.1555 A > G was identified in family A; m.3243 A > G in families B, C, D, E, and F; m.3472 T > C in family G; m.3635 G > A in family H; m.3697 G > A in family I; m.8344 A > G in family J; m.8993 T > G in families K and L; m.9185 T > C in family M; m.10158 T > C in family N; m.10191 T > C in family O; m.13513 G > A in family P; and m.14709 T > C in family Q (Fig. 2a and b). Sanger sequencing was used to identify 11 mutant sites and analyze the heteroplasmy levels in 13 families. The detailed procedure of Sanger sequencing by LIFE SEQSTUDIO was exhibited in Fig. 1a. ddPCR was used to identify four mutant sites and analyze the heteroplasmy levels in 6 families. The detailed procedure of ddPCR by BIO-RAD QX200 is exhibited in Fig. 1b. All mutations and heteroplasmy levels were re-analyzed by NGS. The detection costs for a single sample using four analytical methods (Sanger sequencing, ddPCR, Sanger sequencing combined with ddPCR, and NGS) were $12.55, $18.83, $31.38, and $235.35, respectively (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Recruited seventeen families with twelve mtDNA mutations and the costs of different analytical methods. a Pedigree of seventeen families with the mtDNA-related mitochondrial disease were recruited. b Twelve previously reported pathogenic mutations were involved in these families. c Comparison of the costs for a single sample by four analytical methods (Sanger sequencing, ddPCR, Sanger sequencing combined ddPCR, and NGS)

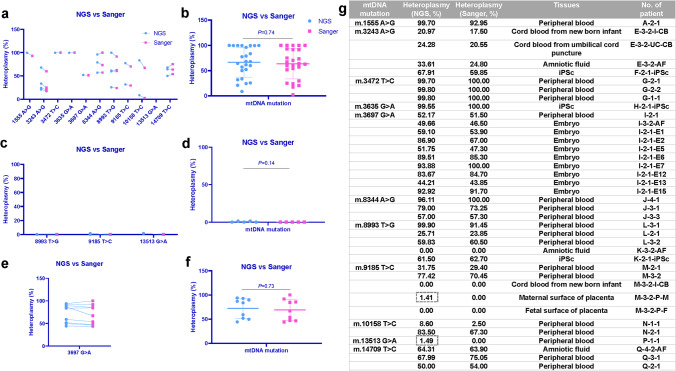

No difference of heteroplasmy levels in thirty-eight samples with eleven mutations between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods, either in common samples with more than 5% heteroplasmy or less than 5% heteroplasmy, or in single-cell samples

To determine the accuracy and reliability of Sanger sequencing method, not only in common sample with high heteroplasmy, but also in low heteroplasmy and single-cell samples, we performed Sanger sequencing in common samples with high heteroplasmy (≥ 5%), low heteroplasmy (< 5%), and single-cell samples, and compared the results with NGS. We firstly performed a one-to-one correspondence comparison of the Sanger and NGS results for common, low heteroplasmy, and single-cell samples, and found very slight differences between these two results.

In common samples, the minimum difference between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods is 0.20% in m.3472 T > C, while the maximum difference is 16.20% in m.10158 T > C (Fig. 3a). Then we compared the overall heteroplasmy levels of all mutations, and the result showed that there is no statistically significant difference between Sanger and NGS analytical methods (Sanger: 63.62 ± 30.00%, NGS: 66.39 ± 29.57%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3b). In low heteroplasmy samples, the minimum difference between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods is 0.00% in m.8993 T > G and m.9185 T > C, while the maximum difference is 1.49% in m.13513 G > A (Fig. 3c). The overall heteroplasmy comparison also showed no statistically significant difference between Sanger and NGS analytical methods (Sanger: 0.00 ± 0.00%, NGS: 1.49 ± 0.58%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3d). In single-cell samples, the minimum difference between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods is 0.36% in m.3697 G > A, while the maximum difference is 19.90% in m.3697 G > A (Fig. 3e). And even in single-cell samples, there was still no statistically significant difference between Sanger and NGS analytical methods in the overall heteroplasmy comparison (Sanger: 68.92 ± 21.88%, NGS: 72.40 ± 20.70%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3f). There were two special samples, the NGS showed 1.41% (M-3–2-P-M) and 1.49% (P-1–1) heteroplasmy levels, while the Sanger sequencing method could not detect the mutation loads (Fig. 3g). The Sanger sequencing method yielded both forward and reverse peak maps for the different heteroplasmy levels. Different levels of mtDNA heteroplasmy levels (0%, 23.85%, 59.85%, 70.45%) in peak maps yielded by peak maps are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods in detecting heteroplasmy level of eleven mtDNA mutations. a One-to-one correspondence comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS results in common samples with high heteroplasmy level (≥ 5%). b Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutations between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods in common samples with high heteroplasmy level (≥ 5%). c One-to-one correspondence comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS results in common samples with low heteroplasmy level (< 5%). d Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutations between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods in common samples with low heteroplasmy level (< 5%). e One-to-one correspondence comparison of Sanger sequencing and NGS results in single-cell samples. f Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutation between Sanger sequencing and NGS analytical methods in single-cell samples. g Numerical value of mutation load, sample type, and the identifier for each sample

Fig. 4.

Peak maps of Sanger sequencing methods. Both forward and reverse peak maps for the different heteroplasmy levels yielded by the Sanger sequencing method. The heteroplasmy levels are 0% (a), 23.85% (b), 59.85% (c), 70.45% (d), and 100% (e)

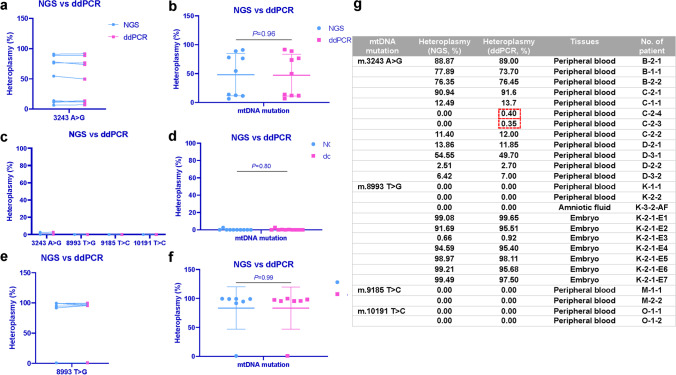

No difference of heteroplasmy levels in twenty-six samples with four mutations between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods, either in common samples with more than 5% heteroplasmy or less than 5% heteroplasmy, or in single-cell samples

To determine the accuracy and reliability of the ddPCR method, not only in common samples with high heteroplasmy, but also in low heteroplasmy and single-cell samples, we performed ddPCR in common samples with high heteroplasmy (≥ 5%), low heteroplasmy (< 5%), and single-cell samples, and compared the results with NGS. We also firstly performed a one-to-one correspondence comparison of the ddPCR and NGS results for common, low heteroplasmy, and single-cell samples, and found very slight differences between these two analytical methods.

In common samples, the minimum difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods is 0.10% in m.3243A > G, while the maximum difference is 4.85% in m.3243A > G (Fig. 5a). Then we compared the overall heteroplasmy levels of the mutation, and the result showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods (ddPCR: 47.22 ± 36.25%, NGS: 48.09 ± 36.66%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5b). And in low heteroplasmy samples, the minimum difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods is 0.00% in m.8993 T > G, m.9185 T > C, and m.10191 T > C, while the maximum difference is 0.40% in m.3243A > G (Fig. 5c). The overall heteroplasmy comparison also showed no statistically significant difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods (ddPCR: 0.35 ± 0.84%, NGS: 0.25 ± 0.79%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5d). Then in single-cell samples, the minimum difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods is 0.26% in m.8993 T > G, while the maximum difference is 3.82% in m.8993 T > G (Fig. 5e). There was still no statistically significant difference between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods in the overall heteroplasmy comparison (ddPCR: 83.25 ± 36.34%, NGS: 83.38 ± 36.60%) (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5f). Even in samples with extremely low heteroplasmy (0.40% and 0.35%), the ddPCR method still could detect the mutation loads (Fig. 5g). Clear fluorescence signals of the wildtype and mutant alleles (blue and green) were observed in the droplets (Fig. 6a and b). And the heteroplasmy levels of several samples by the ddPCR method are exhibited (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of ddPCR and NGS analytical methods in detecting heteroplasmy level of four mtDNA mutations. a One-to-one correspondence comparison of ddPCR and NGS results in common samples with high heteroplasmy level (≥ 5%). b Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutation between ddPCR sequencing and NGS analytical methods in common samples with high heteroplasmy level (≥ 5%). c One-to-one correspondence comparison of ddPCR and NGS results in common samples with low heteroplasmy level (< 5%). d Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutations between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods in common samples with low heteroplasmy level (< 5%). e One-to-one correspondence comparison of ddPCR and NGS results in single-cell samples. f Comparison of the overall heteroplasmy of mutation between ddPCR and NGS analytical methods in single-cell samples. g Numerical value of mutation load, sample type, and the identifier for each sample

Fig. 6.

Maps of droplet numbers and heteroplasmy levels of the ddPCR method. a Scatter plot of the droplet numbers of wildtype and mutant alleles (blue and green) of all wells. b Peak plot of the droplet mumbers of wildtype and mutant alleles (blue and green) of all wells. The droplet with a higher than 3200 fluorescence amplitude value was considered the positive droplet. c The heteroplasmy levels detected by the ddPCR method were computed by the QuantaSoft software

Discussion

For women with mtDNA mutations or with mtDNA-related mitochondrial diseases, reproductive options for obtaining healthy offspring include PD, PGD, MRT, and oocyte donation [1]. Oocyte donation is the safest reproductive option, but the offspring are not biologically related to the mother, which is unacceptable for most families. MRT is expected to get embryos with very low or zero mutation load [13–16]. However, the clinical application of MRT was only approved by a few countries, such as the UK [17]. The vast majority of countries (including China) still explicitly prohibit the genetic editing of germ cells in humans, including MRT [2]. Therefore, PD and PGD are currently the only options for these women to obtain biologically related offspring.

The clinical applications of PD and PGD in women with mtDNA mutations are confronted with challenges. As mtDNA follows maternal inheritance, the proportion of mutant mtDNA in progeny correlates with the mother. However, due to the genetic bottleneck effect of mtDNA during oocyte development, it is still possible to have extreme changes in oocytes that are entirely different from the heteroplasmy of the mother. The bottleneck effect will lead to a certain degree of unpredictability of heteroplasmy in progeny. Currently, it is considered that the idle mtDNA mutation sites for PD should have the following characteristics: mutation load is closely related to the severity of the disease; mutation load remains stable over time; mutant mtDNA is uniformly distributed in all tissues [18]. However, few mutation sites can meet these conditions. In fact, the correlation between mutation load and the onset threshold of disease is undiscovered for most of the mutation sites. For the twelve mtDNA mutations we described in this paper, the threshold effect of most mutations is not clear, because there are very few studies on the precise threshold effect. Through systematic review of literature and analysis of the level of muscle mutation levels between lineages, some studies found that for most mtDNA mutations, setting the threshold of muscle mutation as 18% can greatly reduce the incidence of mtDNA-related mitochondrial disease, and the predicted probability of being affected is only 0.0074. Except, of course, for certain mutations, such as m.3243 A > G [9]. There are more studies on common mutation sites, such as m.3243 A > G, m.8344 A > G, and m.8993 T > G. For example, in the study of trans-mitochondrial cybrids for m.3243 A > G and m.8344 A > G, it was found that when the proportion of wild-type mtDNA was less than about 10%, the respiration capacity of mitochondria showed a cliff decline; that means, 10% of wild-type mtDNA was enough to provide the energy required by the cell. Therefore, the study believed that the threshold effect of mtDNA was high for these two mutations, it is about 90% [19, 20]. However, other studies have found that for m.3243 A > G, even a low percentage of mutation load (28%) can lead to disease occurrence [21]. Accordingly, with regard to m.3243 A > G, the threshold is difficult to determine, and the current threshold for embryo selection in PGD applications ranges from 15 to 30%. For m.8993 T > G, the median heteroplasmy level in symptomatic patients is thought to be 90% (78–95%) [22]. Through the analysis of genotype–phenotype correlation, some studies suggest that heteroplasmy level causing severe clinical phenotype is 60–70% [23]. For m.3635 G > A and m.3697 G > A, the threshold effect may be higher, but the same mutation load shows that male and female patients have different phenotypes or diseases; that is, there is a difference in penetrance [24, 25]. Therefore, it seems that only threshold effects cannot be used to predict morbidity [26]. For m.9185 T > C, the median heteroplasmy level in symptomatic patients was considered to be 100% (99–100%) [22]. And for m.1555 A > G, m.10158 T > C, m.3472 T > C, m.13513 G > A, m.14709 T > C, and m.10191 T > CC, these rare mutation sites, studies have mostly focused on case reports, and no relevant studies on threshold effects have been conducted. The dilemma of PGD is basically the same as those of PD. The advantage of PGD compared with PD is that embryos with low mutation load can be selected for transplantation at an early stage, which dramatically reduces the probability of pregnancy termination. The disadvantage is that the onset threshold of disease is uncertain for most mutation sites. So it is very tough to determine the threshold of embryo selection, especially for the intermediate heteroplasmy level.

Whether PD or PGD, the development of reliable mtDNA heteroplasmy analytical methods is the most fundamental guarantee for implementing these technologies. The heteroplasmy levels in multiple samples should be quantified before and after the implementation of PD or PGD, including blood, hair, and urine samples from the proband, mother, and the other family members before PD or PGD; biopsied single-cell from embryos, blood, amniotic fluid, and umbilical cord blood samples during pregnancy; and postpartum umbilical cord blood, placenta, baby’s blood, hair, nails, urine, and other samples after birth. Long-term follow-up should also be conducted for children. Detection of multiple samples for an individual patient dictates that the analytical methods need to be cost-effective to minimize the financial burden on these families. Therefore, our principle is to develop accurate, reliable, and economical mtDNA heteroplasmy analytical methods that can quantify even an extremely low percentage of mutation load, and the methods can also be used for single-cell heteroplasmy quantification.

At present, there are multiple analytical methods available for the detection of mtDNA heteroplasmy, including enzyme-related methods [27], NGS [28, 29], Sanger sequencing [30], high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [31], SNaPshot [32], pyrosequencing [33], and other PCR-related techniques [27]. Each of these analytical methods has its scope and short slab. For example, mtDNA heteroplasmy can be detected by enzyme-related methods and HPLC, but the mutation load cannot be quantified [27, 34]. The SNaPshot cannot quantify heteroplasmy of < 5% [34]. Pyrosequencing and NGS, especially NGS, are widely used to quantify the mtDNA heteroplasmy level, especially the samples with very low mutation load. The results are accurate and sensitive, but the cost is too high to detect a large number of samples [27, 30, 33]. Sanger sequencing has been proved to be a simple, stable, and reliable analytical method to quantify mtDNA heteroplasmy. The defect of Sanger sequencing is low sensitivity for low mutation load (< 5%) [30]. However, due to the low cost, simple primer design, and convenient operation, Sanger sequencing is very appropriate for high heteroplasmy quantification or primary detection. Other PCR-related analytical methods, such as real-time PCR and qPCR, are also frequently used to quantify the mtDNA heteroplasmy. Still, some methods are cumbersome, or the sensitivity is limited that the extremely low heteroplasmy cannot be detected, or some probes and primers have higher prices [27]. Among them, digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) has been proved to be used for quantitative heteroplasmy with high sensitivity but tedious operation and slightly higher price [35]. The ddPCR system performs microdroplet processing on the sample before the traditional PCR amplification and precisely quantifies as low as 1 to 10 copies [36]. However, the complexity of probe design is the weakness. According to the research objectives, laboratory conditions, and cost, clinicians must choose appropriate analytical methods to quantify mtDNA heteroplasmy.

The patients who come to our center are mtDNA mutation carriers or mtDNA-related mitochondrial disease women with fertility requirements whose mtDNA mutations have been found and confirmed in neurology or pediatrics. Our major work is performing PD or PGD for these patients. For the recognized pathogenic site, multiple samples are the characteristics of the patients we faced. So the sophisticated analytical methods are not required. Methods with convenience, high sensitivity, and money-saving are the major requirements. Furthermore, another point is to quantify mtDNA heteroplasmy in single-cell biopsied from an embryo. Considering the time, cost, strengths, and weaknesses of different analytical methods and the instrument conditions available in our laboratory, we selected economical and uncomplicated Sanger sequencing combined with highly sensitive ddPCR analytical method to detect the mtDNA heteroplasmy. For samples with high heteroplasmy (≥ 5%), we found that the mutation loads measured by Sanger sequencing and ddPCR analytical methods were in basic agreement with NGS, and there was no statistically significant difference. For samples with low heteroplasmy (< 5%), there is no difference between Sanger sequencing and NGS. However, Sanger sequencing could not detect two extremely low heteroplasmy (1.41% and 1.49%), whereas NGS could find them. We know that the calculated heteroplasmy level of the Sanger sequencing method is based on the peak map, and for extremely low heteroplasmy, sometimes the second peak may not be detected by the software or maybe identified as miscellaneous peaks, leading to failure of heteroplasmy identification. In ddPCR, the reaction system was divided into thousands of microdroplets. Each microdroplet contains one or several nucleic acids to be tested. ddPCR can achieve absolute quantification of DNA copy number, with a lower limit of quantification up to 0.01% [37]. Therefore, ddPCR was extremely sensitive to detect low heteroplasmy less than 1%. For single-cell samples, after whole-genome amplification, both Sanger sequencing and ddPCR analytical methods quantified mtDNA heteroplasmy precisely. We propose that Sanger sequencing is the first choice for heteroplasmy quantification based on the above results. Suppose the heteroplasmy level is greater than 5%, in that case, Sanger sequencing can fully indicate the actual mtDNA heteroplasmy. And if the heteroplasmy level is less than 5%, to further confirm if there is any undiscovered heteroplasmy, the samples should be sequenced again by ddPCR.

Conclusions

Our study has successfully established an economical, high-sensitive, accurate, and single-cell analytical method for mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification. We prefer the Sanger sequencing method for primary mtDNA heteroplasmy quantification. If the heteroplasmy level is above 5%, then the consequential result of Sanger sequencing method is the final result. If the heteroplasmy level is below 5%, we have to do the ddPCR method besides, and the ddPCR result is the final result. We expect to bring the hope of healthy babies to more women with mtDNA-related mitochondrial diseases in the future.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Author contribution

DJ and YC contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by KZ, ZZ, and WZ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by WZ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Number [2021YFC2700901]), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers [82001635], [81971455], and [U20A20350]), the Clinical Medical research transformation Project of Anhui Province (Grant Number [202204295107020012]), the Foundation for Selected Scientists Studying Abroad of Anhui Province (Grant Number [2022LCX015]), and the Program for Outstanding Young Talents in University of Anhui (Grant Number [gxyqZD2022027]).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the [JianGuoYun] [https://www.jianguoyun.com/#/sandbox/153e00c/7d665ba27fc57467/%2FRaw%20data%2020220526].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University (March 1, 2018 / No. 20180243).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Weiwei Zou, Kai Zong, and Zhikang Zhang contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Yunxia Cao, Email: caoyunxia5972@ahmu.edu.cn.

Dongmei Ji, Email: jidongmei@ahmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Silva-Pinheiro P, Minczuk M. The potential of mitochondrial genome engineering. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23(4):199–214. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis RL, Wong SL, Carling PJ, Payne T, Sue CM, Bandmann O. Serum FGF-21, GDF-15, and blood mtDNA copy number are not biomarkers of Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020;10(1):40–46. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbst A, Prior SJ, Lee CC, Aiken JM, McKenzie D, Hoang A, Liu N, Chen X, Xun P, Allison DB, Wanagat J. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA copy number and mitochondrial DNA deletion mutation frequency as predictors of physical performance in older men and women. GeroScience. 2021;43(3):1253–1264. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou W, Slone J, Cao Y, Huang T. Mitochondria and their role in human reproduction. DNA Cell Biol. 2020;39(8):1370–8. doi: 10.1089/dna.2019.4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbert M, Turnbull D. Progress in mitochondrial replacement therapies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(2):71–72. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2018.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang E, Wu J, Gutierrez NM, Koski A, Tippner-Hedges R, Agaronyan K, Platero-Luengo A, Martinez-Redondo P, Ma H, Lee Y, Hayama T, Van Dyken C, Wang X, Luo S, Ahmed R, Li Y, Ji D, Kayali R, Cinnioglu C, Olson S, Jensen J, Battaglia D, Lee D, Wu D, Huang T, Wolf DP, Temiakov D, Belmonte JC, Amato P, Mitalipov S. Mitochondrial replacement in human oocytes carrying pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations. Nature. 2016;540(7632):270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada M, Emmanuele V, Sanchez-Quintero MJ, Sun B, Lallos G, Paull D, Zimmer M, Pagett S, Prosser RW, Sauer MV, Hirano M, Egli D. Genetic drift can compromise mitochondrial replacement by nuclear transfer in human oocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(6):749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bredenoord AL, Appleby JB. Mitochondrial replacement techniques: remaining ethical challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(3):301–304. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellebrekers DM, Wolfe R, Hendrickx AT, de Coo IF, de Die CE, Geraedts JP, Chinnery PF, Smeets HJ. PGD and heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA point mutations: a systematic review estimating the chance of healthy offspring. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(4):341–349. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smeets HJ, Sallevelt SC, Dreesen JC, de Die-Smulders CE, de Coo IF. Preventing the transmission of mitochondrial DNA disorders using prenatal or preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1350:29–36. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin C, Li DY, Guo X, Cao HY, Chen YB, Zhou F, Ge NJ, Liu Y, Guo SS, Zhao Z, Yang HS, Xing JL. NGS-based profiling reveals a critical contributing role of somatic D-loop mtDNA mutations in HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(6):953–962. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perales-Clemente E, Cook AN, Evans JM, Roellinger S, Secreto F, Emmanuele V, Oglesbee D, Mootha VK, Hirano M, Schon EA, Terzic A, Nelson TJ. Natural underlying mtDNA heteroplasmy as a potential source of intra-person hiPSC variability. EMBO J. 2016;35(18):1979–1990. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, Sha H, Ji D, Zhang HL, Chen D, Cao Y, Zhu J. Polar body genome transfer for preventing the transmission of inherited mitochondrial diseases. Cell. 2014;157(7):1591–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Liu H, Luo S, Lu Z, Chavez-Badiola A, Liu Z, Yang M, Merhi Z, Silber SJ, Munne S, Konstantinidis M, Wells D, Tang JJ, Huang T. Live birth derived from oocyte spindle transfer to prevent mitochondrial disease. Reprod Biomed Online. 2017;34(4):361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craven L, Tuppen HA, Greggains GD, Harbottle SJ, Murphy JL, Cree LM, Murdoch AP, Chinnery PF, Taylor RW, Lightowlers RN, Herbert M, Turnbull DM. Pronuclear transfer in human embryos to prevent transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease. Nature. 2010;465(7294):82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature08958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tachibana M, Sparman M, Sritanaudomchai H, Ma H, Clepper L, Woodward J, Li Y, Ramsey C, Kolotushkina O, Mitalipov S. Mitochondrial gene replacement in primate offspring and embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;461(7262):367–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adashi EY, Cohen IG. Going germline: mitochondrial replacement as a guide to genome editing. Cell. 2016;164(5):832–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorburn DR, Dahl HH. Mitochondrial disorders: genetics, counseling, prenatal diagnosis and reproductive options. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106(1):102–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attardi G, Yoneda M, Chomyn A. Complementation and segregation behavior of disease-causing mitochondrial DNA mutations in cellular model systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1271(1):241–248. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson NG, Tulinius MH, Holme E, Oldfors A, Andersen O, Wahlström J, Aasly J. Segregation and manifestations of the mtDNA tRNA(Lys) A–>G(8344) mutation of myoclonus epilepsy and ragged-red fibers (MERRF) syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51(6):1201–1212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spath K, Babariya D, Konstantinidis M, Lowndes J, Child T, Grifo JA, Poulton J, Wells D. Clinical application of sequencing-based methods for parallel preimplantation genetic testing for mitochondrial DNA disease and aneuploidy. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(6):1521–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganetzky RD, Stendel C, McCormick EM, Zolkipli-Cunningham Z, Goldstein AC, Klopstock T, Falk MJ. MT-ATP6 mitochondrial disease variants: phenotypic and biochemical features analysis in 218 published cases and cohort of 14 new cases. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(5):499–515. doi: 10.1002/humu.23723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chinnery PF, Howell N, Lightowlers RN, Turnbull DM. Molecular pathology of MELAS and MERRF. The relationship between mutation load and clinical phenotypes. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 10):1713–1721. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.10.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong S, Wen S, Qiu Y, Yu Y, Xin L, He Y, Gao X, Fang H, Hong D, Zhang J. Bilateral striatal necrosis due to homoplasmic mitochondrial 3697G>A mutation presents with incomplete penetrance and sex bias. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(3):e541. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spangenberg L, Graña M, Greif G, Suarez-Rivero JM, Krysztal K, Tapié A, Boidi M, Fraga V, Lemes A, Gueçaimburú R, Cerisola A, Sánchez-Alcázar JA, Robello C, Raggio V, Naya H. 3697G>A in MT-ND1 is a causative mutation in mitochondrial disease. Mitochondrion. 2016;28:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun D, Li B, Qiu R, Fang H, Lyu J. Cell type-specific modulation of respiratory chain supercomplex organization. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):926. doi: 10.3390/ijms17060926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobenin IA, Mitrofanov KY, Zhelankin AV, Sazonova MA, Postnov AY, Revin VV, Bobryshev YV, Orekhov AN. Quantitative assessment of heteroplasmy of mitochondrial genome: perspectives in diagnostics and methodological pitfalls. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:292017. doi: 10.1155/2014/292017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasta V, Ng SB, Turner EH, Shendure J, Hahn SH. Next generation sequence analysis for mitochondrial disorders. Genome Med. 2009;1(10):100. doi: 10.1186/gm100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Németh K, Darvasi O, Likó I, Szücs N, Czirják S, Reiniger L, Szabó B, Kurucz PA, Krokker L, Igaz P, Patócs A, Butz H. Next-generation sequencing identifies novel mitochondrial variants in pituitary adenomas. J Endocrinol Investig. 2019;42(8):931–940. doi: 10.1007/s40618-019-1005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaag KJV, Desmyter S, Smit S, Prieto L, Sijen T. Reducing the number of mismatches between hairs and buccal references when analysing mtDNA heteroplasmic variation by massively parallel sequencing. Genes. 2020;11(11):1355. doi: 10.3390/genes11111355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Den Bosch BJ, de Coo RF, Scholte HR, Nijland JG, van Den Bogaard R, de Visser M, de Die-Smulders CE, Smeets HJ. Mutation analysis of the entire mitochondrial genome using denaturing high performance liquid chromatography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(20):E89. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cassandrini D, Calevo MG, Tessa A, Manfredi G, Fattori F, Meschini MC, Carrozzo R, Tonoli E, Pedemonte M, Minetti C, Zara F, Santorelli FM, Bruno C. A new method for analysis of mitochondrial DNA point mutations and assess levels of heteroplasmy. Biochem Biophys Res commun. 2006;342(2):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan JB, Zhang R, Xiong C, Hu C, Lv Y, Wang CR, Jia WP, Zeng F. Pyrosequencing is an accurate and reliable method for the analysis of heteroplasmy of the A3243G mutation in patients with mitochondrial diabetes. J Mol Diagn : JMD. 2014;16(4):431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abicht A, Scharf F, Kleinle S, Schön U, Holinski-Feder E, Horvath R, Benet-Pagès A, Diebold I. Mitochondrial and nuclear disease panel (Mito-aND-Panel): combined sequencing of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA by a cost-effective and sensitive NGS-based method. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2018;6(6):1188–1198. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tytgat O, Tang MX, van Snippenberg W, Boel A, Guggilla RR, Gansemans Y, Van Herp M, Symoens S, Trypsteen W, Deforce D, Heindryckx B, Coucke P, De Spiegelaere W, Van Nieuwerburgh F. Digital polymerase chain reaction for assessment of mutant mitochondrial carry-over after nuclear transfer for in vitro fertilization. Clin Chem. 2021;67(7):968–976. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mu D, Yan L, Tang H, Liao Y. A sensitive and accurate quantification method for the detection of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA by the application of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction amplification system. Biotechnol Lett. 2015;37(10):2063–2073. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Floren C, Wiedemann I, Brenig B, Schütz E, Beck J. Species identification and quantification in meat and meat products using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) Food Chem. 2015;173:1054–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the [JianGuoYun] [https://www.jianguoyun.com/#/sandbox/153e00c/7d665ba27fc57467/%2FRaw%20data%2020220526].