Abstract

Direct Ink Writing (DIW) opens new possibilities in three-dimensional (3D) printing of carbon-based polymeric ink. This is due to its ability in design flexibility, structural complexity, and environmental sustainability. This area requires exhaustive study because of its wide application in different manufacturing sectors. The present article is related to the variant emerging 3D printing techniques and DIW of carbonaceous materials. Carbon-based materials, extensively used for various applications in 3D printing, possess impressive chemical stability, strength, and flexible nanostructure. Fine printable inks consist predominantly of uniform solutions of carbon materials, such as graphene, graphene oxide (GO), carbon fibers (CFs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and solvents. It also contains compatible polymers and suitable additives. This review article elaborately discusses the fundamental requirements of DIW in structuring carbon-doped polymeric inks viz. ink formulation, required ink rheology, extrusion parameters, print fidelity prediction, layer bonding examination, substrate selection, and curing method to achieve fine functional composites. A detailed description of its application in the fields of electronics, medical, and mechanical segments have also been focused in this study.

Keywords: direct ink writing, additive manufacturing, polymer, carbon, composite, 3D printing

Introduction

Additive Manufacturing (AM), or quick prototyping, is defined as a rapid layering process of joining materials to form three-dimensional (3D) functional objects.1 Its advantage over conventional manufacturing techniques lies to the final shape that it creates by adding required materials. Furthermore, unlike subtraction-based techniques, AM also encourages environment-friendly product designs.2 In recent times, the layering of polymer-based inks is gaining traction in research fields and knowledge domain. It offers multiple possibilities for the integration of functional materials to adjust variety of features in ink. Today, several methods for precise printing of inks to form 3D structures have emerged. Among them, Direct Ink Writing (DIW) is essentially one that easily utilizes economical materials with versatility, and constructs 3D complex structures.

This makes the technique unique in its own way and very demanding for interdisciplinary research.3 Also known as Robocasting, this technique was first developed in 1996 at Sandia National Laboratories, USA, to create geometrically complex structures using inorganic ceramic ink.4

It is noted that the advent of 3D printing periodic structures causes technological advancement in micro and nanoscale fabrication. The broad options for material selection in DIW offer great opportunities by structuring 3D parts with various polymers and reinforcing agents. DIW imposes flexibility in length scales and patterning approaches. High-stiffness sandwich panels,5 electrodes,6 sensors,7 microfluidic networks,8 energy absorbers,9 drug delivery devices,10 and tissue-engineering scaffolds11 are few such structures where DIW is most desirable.

The DIW methodology describes manufacturing techniques that use a software-controlled translation stage equipped with an ink-deposition syringe nozzle setup to print materials having controlled structure and composition.12 Interestingly, all kinds of materials can be used in the DIW technique, viz. colloidal gels, polymers, hydrogels, biomedicals, ceramics, and emulsions. Printed inks are solidified by inducing high temperature, evaporating the solvents,12 upon exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays13 and xenon radiations.14

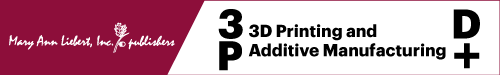

As Figure 1a indicates, 3D structures consisting of continuous solids, parallel walls (a high aspect ratio), spanning features, and cantilevers, can be constructed by careful regulation of ink composition, printing parameters, and rheological behavior.3

FIG. 1.

(a) Structures generally available in DIW,3 (b) available forms of CNTs36 [adapted with permission], (c) orientation of graphitic planes in CF, and (d) properties of different carbonaceous materials.30,37–41,49,50,59–62 CF, carbon fiber; CNT, carbon nanotube; DIW, Direct Ink Writing.

Extrudable inks are an essential part of DIW related to printing materials and structural design.15 Researchers have examined that the behavior of shear thinning and apparent viscosity are vital for inks. Shear thinning is the non-Newtonian behavior of inks whose viscosity decreases under shear strain. In contrast, apparent viscosity of these fluids depends upon the ratio of the shear stress applied to the fluids and shear rate.16,17 Hence, viscosity control is the prime factor in the formulation of printable ink. Compared with other additive techniques like ink-jet printing (IJP) and material jetting, DIW offers a broad range of viscosity. This in turn allows for the mixing of high-percentage doping materials, which help in achieving high functionality.

Liquid polymers with low melting points are commonly used in 3D printing industries due to their low weight and cost, and versatile processing. However, most of the 3D printed parts remain as prototypes instead of practical functional components. This is because pure polymers printed through 3D printing setups are not completely functional and load bearable, they lack strength and functionality. Researchers working in this domain have resolved this issue by doping different percentages of various metal and nonmetal particles, sized from micro to nano scales, to achieve higher performance and strength.18 Mixing of these materials in liquid polymers is termed as “compositing the ink.” Therefore, the productions of composites compatible with DIW printers have grabbed great attraction in recent years.

Carbon-based materials have gained popularity among these dopings because of their fine chemical stability, high surface area, and flexible nanostructures.19 Carbon-doped composite inks are commonly used in printing parts through DIW mainly consisting of the solutions of carbon nanotubes (CNTs),20 graphene,21 graphene oxide (GO),22 carbon fibers (CFs),23 and solvents, as well as polymers and other additives.14

By incorporating carbon-based materials into a 3D printable category, it is possible to manufacture 3D products with optimized structural and functional properties, such as exceptional mechanical property,21 good electrical conductivity,24,25 high thermal conductance,26 and biocompatibility.27

The polymer matrix protects reinforcements from atmospheric situations, imparts textures, and provides load transfer capability. The development of these composites in 3D printed patterns depends on the characteristics of fillers as reinforcing, such as interactions between reinforcement particles and the matrix, alignment, and dispersion of the fillers.28 As a result of the easy processing of the polymer matrix, carbon-reinforced polymers are of significant interest in comparison to ceramics and metals.15

Due to the specific characteristics, such as high aspect ratio, high conductivity, high tensile strength, CNTs are considered as excellent fillers.29 Graphene also shows high thermal and electrical conductivity, which can significantly influence 3D printed polymer composite.21,27 Its two-dimensional (2D) shape provides a lead in imparting unique mechanical features.30 CF helps in providing high strength and thermal stability.23

Although DIW has been very appealing over the past two decades, most published research articles have devoted their attention to the implementation of processing techniques for printing doped polymeric materials. Carbon-based composite is gaining wider traction because of its inexpensiveness and biodegradable nature.31 Hence condensed information about printing carbon-based ink through DIW has been well documented in this review.

The present article will consist of all basic requirements for the technique, that is, ink formulation, required ink properties, printing parameter optimization for checking print fidelity, layer bonding examination, and substrate selection. Direct written carbon-based composite with their field of application has been discussed thoroughly. This article will also provide an overview of carbonaceous materials and recently active 3D printing technologies with their origin.

Carbon Materials

Carbon nanotubes

In 1991, Iijima's discovery of CNTs initiated revolutionary improvements in the field of polymer nanocomposites.32 After the discovery, the first CNT-reinforced polymer nanocomposite was fabricated in the year 1994.33 CNTs are essentially rolled-up graphene sheets in the form of cylinders. The magnitude and direction of the chiral vector in graphene sheets determine the morphology of CNT.34 The sheets have hexagonal structures, and the cylindrical CNTs are usually chopped with fullerene. There are two types of CNTs; (1) single-walled CNTs (SWNTs) and (2) multiwalled CNTs (MWCNTs).35

SWNTs are rolled single graphene sheets, whereas MWCNTs are the stacking of concentric cylindrical layers of various graphene sheets with interspacing of 0.34 nm. Armchair, zigzag, and chiral shapes are the three available forms of CNTs according to the arrangements of atoms (Fig. 1b).36 Their properties are strongly dependent on morphology and diameter. Due to their unique size and shape, CNTs possess mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity.

The elastic moduli in SWNT ranges from 2.8 to 3.6 TPa, whereas of MWCNT between 1.7 and 2.4 TPa. The device used for the measurement is Micro-Raman Spectroscopy.37 The measured value of tensile strength of MWCNT is in the range of 11–63 GPa. Only the outer layer of MWCNT could withstand higher loads.

In contrast, the load transfer to the inner layers was found to be very weak.38 Also, the reported average breaking strength of SWNT was found to be 30 GPa.39 Apart from mechanical strength, CNTs shows electrical and thermal properties too. Conductivity values vary broadly from one particle to another. Four probe measurements showed the electrical conductivity value of individual MWCNT in the range of 107–108 S/m.40 The value of electrical resistivity was observed in the range of 10−7 to 10−8 Ωm.41 Around 6000 W/mK thermal conductivity was reported for isolated CNTs comparable to diamond.42

Graphene-based materials

Since the discovery of graphene in 2004,43 it has been the center of interest in various fields. This is due to its extraordinary electrical, chemical, optical, and mechanical properties.44 Graphene is a 2D sheet composed of sp2-bonded single-layer carbon atoms with the honeycomb lattice structure and unique structural features.45,46 Each hexagon in the graphene sheet exhibits two pi-electrons, which are delocalized, allowing for efficient conduction of electricity. The holes in the structure also allow photons to pass through unimpeded, giving rise to high thermal conductivity. Only 2.3% absorption of light takes place over a wide range of wavelengths in each graphene sheet.

Graphene also shows a high surface area of around 2630 m2/g.47,48 The measured value of the Young's modulus, which is ∼1 TPa, indicates its excellent mechanical property. Also, the tensile strength value of around 130 GPa, confirms its mechanical excellence.30 A total of 5000 W/m/k thermal conductance has been found for graphene, which confirms its superior thermal characteristics.49,50

Due to its large specific surface area, single-layer graphene is difficult to produce on a large scale, as well as to disperse in solvents.

The availability of graphene-related materials, such as multilayer graphene, graphene nanoplatelets, or GOs are far more frequently studied in comparison to planegraphene.51 GO's oxidized functional group can increase graphene dispersion into a matrix, solvents, and reduce graphene phase separation and agglomeration. However, due to the extensive existence of sp3 C-C bonds as well as the defects, these functional groups exacerbate the electrical conductivity of GO, but enhance mechanical strength.51,52 The chemical or physical reduction of GO, which is a cost-effective technique for preparing graphene sheets with strong electrical properties, obtains reduced graphene oxide (rGO).53

Carbon fibers

CF is a type of carbonized and graphitized microcrystalline graphite material. These are long fine threaded materials with diameters ranging between 5 to 10 μm. The carbon atoms present in these are strongly bonded to form crystal planes, aligned nearly parallel along the axis of the fiber (Fig. 1c). The parallel crystal arrangement gives the fiber incredible strength.54,55 CF was first developed from cellulosic fibers for use in electric lamps by Thomas Edison in1879.56 However, as commercial production, it was first started in 1958 by using rayon as a precursor.57 High strength, lightweight, and magnificent thermal stability are essential features of these fibers.

CF-based polymer composites’ fabrication was started in 1960s, and its high strength to weight ratio has drawn the interest of many researchers over the years. These composites progressively spread their bequests in different applications, such as in the automobile, civil, electronics, and aircraft industries.58 Polyacrylonitrile, rayon, and mesophase pitch are general precursors used to fabricate these carbon-based fibers. Tensile strength of these varies from 1.0 to 7.0 GPa, depending upon the precursor. Similarly, 50–800 GPa modulus has been observed for rayon to polyacrylonitrile precursor-based CFs.59

Origin, Techniques, and Fundamental Process of 3D Printing

The most popular technique in the field of AM is fused deposition modeling (FDM). It is based on the melting and layering mechanism. The story goes that in the late 80s, Scott Crump was looking for a simpler method to make a toy for his daughter. By using a hot glue gun, he melted plastics and poured them into thin layers and termed the mechanism as FDM. Later, he used polymer filaments for melting and automated the mechanism with Numerical control software and patented it.63–65 Whereas, due to its groundbreaking patent for the first AM technique submitted in 1984, Chuck Hull is widely regarded as the father of 3D printing within the AM field.66,67 The word stereolithography (SLA) was first revealed in Hull's patent, but the origin behind the technique can be traced back to the Nagoya Municipal Research Institute experiments performed by Hideo Kodama in 1981.68

So, a wide range of AM instruments are available today for professionals and researchers. Of them, FDM, selective laser sintering (SLS), IJP, SLA closely related to digital light processing (DLP; collectively termed as vat-polymerization), and DIW are well established and most frequently used (Table 1).

Table 1.

Three-Dimensional Printing Technologies’ Description

| 3D printing process | Description | Materials | Technologies | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vat-polymerization | Liquid photopolymer in a vat is cured by light-activated polymerization | Acrylic and epoxy-based UV curable resins | DLP SLA |

Simple, fine resolution, high strength | High cost, toxic materials |

| Material extrusion | Material dispensed through the nozzle or orifice | PLA, ABS, PEEK, PA, PC, ceramics, Thermosetting polymers, foods, living cells, composites | FDM DIW |

Simple, multimaterial, low cost, versatile | Clogging, anisotropy |

| Powder-based fusion | Thermal energy fuses regions of a powder bed | Polycaprolactone, Polyamide, Thermoplastics | SLS | No supports, good strength | High cost, powdery surface |

| Material jetting | Droplets of material are deposited and cured on a build plate | Thermosetting polymers, composites, particles | IJP | No supports, versatile | Conversion of 2D to 3D, less mechanical strength |

2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional; DIW, Direct Ink Writing; DLP, digital light processing; FDM, fused deposition modeling; IJP, ink-jet printing; PLA, poly(lactic-acid); SLA, stereolithography; SLS, selective laser sintering; UV, ultraviolet.

Others, on the contrary, are used by small group of researchers or are still at the developing stage. Each methodology has its own benefits and limitations in printing 3D parts. The choice of printing technique is based on the raw materials, processing speed, resolution requirements, end-product cost, and performance specifications. Almost every technique follows four basic steps, viz. 3D modeling, conversion into STL extension format, slicing, and layering of required materials to form 3D physical part.

The 3D modeling can be done with the help of various CAD softwares, viz. Creo parametric, Solidworks, AutoCAD, Ansys, to name a few. Modeling can also be done by scanning the already existing parts by 3D scanner. One more modeling method is photogrammetry, in which the object is scanned manually by capturing pictures from all angles and clubbing them in a single file.69 Now the next step is to save the CAD file in STL extension format. Standard triangular language, standard tessellation language, and SLA70,71 are some full forms of STL, so there is still a mist in its full form even after three decades.

STL encodes the 3D model information using a basic simple concept termed as “tessellation.” Tessellation is a process of tilling the surface with various shaped facets, so that there are no overlaps or gaps. The unique idea is to tessellate the external surface of models using triangular facets or tiny triangles and store the information about each facet in a file. The file format provides two different techniques for storing information of each tiny triangle; Binary encoding and ASCII encoding.71 In both ways, data are stored in the form of coordinates of the vertices and outward unit normal vector of each facet. The next step is slicing or the conversion of files in G-codes. Models are converted in the number of 2D sheets by slicing, encoded in terms of G and M, where each line of the coding tells the printing machine to perform one discrete action.

There are several open-source software available for slicing, for example, Prusa, slic3r, and the like.72 When this file is sent to the machine, it reads line by line and performs accordingly. Here, the overlapping of 2D layers of required materials take place to form a physical 3D part.

In FDM, a filament composed of a thermoplastic, such as acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene or poly(lactic-acid) (PLA), is heated above its melting point. Next, it flows out of the nozzle in a semiliquid form, and is deposited layer by layer into a heated substrate to provide a 3D structure (Fig. 2a).73 The quality of printed parts can be controlled by altering printing parameters, such as layer thickness, printing orientation, raster width angle, and the gap between adjacent rasters.74

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of mechanisms of (a) FDM 3D printing, (b) DLP 3D printing, (c) SLS 3D printing, (d) IJP 3D printing, (e) DIW 3D printing, and (f) different types of DIW. 3D, three-dimensional; DLP, digital light processing; FDM, fused deposition modeling; IJP, ink-jet printing; SLS, selective laser sintering.

FDM-based printers offer advantages, including low cost, high speed, and simplicity. “Vat-Polymerization” is another technique used for printing 3D parts. By using photopolymerization, it exposes liquid polymers to UV light and transforms them into solids following layer-by-layer format. SLA and DLP fall under this category and use photo curable resins, a combination of monomers, oligomers, and photoinitiators, where the amount of photoinitiators decide the depth of polymerization. The only difference between these two is noted in the nature of radiation sources applied for curing the polymers.

DLP uses UV light from the projector (Fig. 2b), whereas SLA uses a UV laser beam.75 In this printing technique, various process parameters, viz. depth of curing, the intensity of laser power, scanning speed, and exposure duration, affect curing time and resolution of the print.76

In SLS, the particles of a polymer powder are selectively sintered by a laser and fused to form the item layer by layer. This technique widely uses polystyrenes, polyamide, and polycaprolactone powders. The laser of the system scans the layer's contour and selectively fuses the particles. The portion is scanned across the entire cross-section so that the element solidifies entirely with the desired resolution (Fig. 2c).77 The resolution of the printed part is determined by the powder's particulate size, laser strength, spacing of the scan, and scanning speed.78 SLS provides excellent binding strength between layers. This ensures that the parts possess isotropic properties, making SLS ideal for printing functional objects and prototypes.

IJP is a deposition technique used for liquid-phase materials or inks. These inks consist of a solute, dissolved or dispersed into a solvent. The ink is extruded through a number of tiny nozzles within the print head. As the jetting print head scans over the build surface, multiple layers of a complex model are formed through a layer-by-layer process (Fig. 2d).79,80 The prime parameters that usually affect the printing through IJP are fluid properties, jetting velocity, nozzle dimensions, and waveform design.81 Some of the significant advantages of this technique are, high resolution, smooth surface finish, and wide range of material selection.82

In the DIW approach, colloids, pastes, gels, or organic-based inks are used for creating functional structures by means of a deposition on different substrates in layer-by-layer form.83 DIW printing is primarily accomplished by the movement of a piston that pushes the low viscous material to the high viscous material contained in a syringe through a micronozzle (Fig. 2e). The syringe head is generally connected to a three-axis positioning stage, which helps to generate a designed 3D complex object. In this technique, curing can be conducted using mixing nozzles by dispensing two reactive components or by inducing either heat or UV light.84 In certain situations, to complete the curing reaction, print materials can be supplied to a plotting solution. The quality of the final printed parts is associated with the viscosity of material and deposition rate.85

Distinctively, DIW can be divided into three different categories; (1) Piston-based or positive displacement, (2) Pneumatic or time-pressure dispensing, and (3) Archimedes screw or rotating-screw extrusion (Fig. 2f). The extrusion mechanisms differ among these setups. Every 3D printing method follows those basic four steps (Fig. 3a) discussed earlier.

FIG. 3.

(a) Basic 3D printing procedure. Start from 3D modeling to printing.69 [Adapted with permission.] (b) Flow representation of all required sections of DIW.

Positive displacement system uses a motor to force the piston downward, thereby extruding material depending upon the displacement rate of the motor. The time-pressure or pneumatic system provides air pressure into the syringe to extrude the material outward, where the difference between the supplied air pressure and ambient pressure drives the material to flow. Archimedes screw or auger in rotating-screw extrusion is used for extruding the material, where the degree of rotation is a controlling parameter while dispensing.86,87

The speed of motor displacement determines the amount of material dispensed in both positive displacement and rotary screw systems and is different from the time-pressure dispensing system. The high economic benefit, ability to work with inks/pastes in a wide range of viscosities, and creating complex structures without the need for lithographic techniques are some specific advantages of DIW. The deposition of material at room temperature is another added benefit of DIW systems. It has enabled the technique for depositing materials that are sensitive to heat.

In FDM and SLS, materials deposited are heated above their melting point or glass transition temperature (Tg). Due to this, such materials may undergo decomposition or irreversible oxidation upon prolonged oxygen exposure.88,89 Homogeneous dispersion of reinforcements in filaments, a basic need for research through FDM, is quite difficult. Moreover, voids can be formed during the manufacturing of composite filaments. Maintaining the required level of molten viscosity is another significant challenge in FDM. It should be sufficiently high for structural support and low enough to allow extrusion. Complete removal of the support structures is also not possible, as it might hinder the functionality of the printed composite part.90

High molecular diffusion upon exposure to laser has limited the choice of materials used in the SLS process. Porous structures are formed with SLS, which limits its application at a broader level. The major limitations of SLA/DLP are their high setups and material costs.

Photocurable resin can only be processed for the fabrication of 3D parts. SLA setup do not allow to be mixed with high percentage of reinforcements, as it hinders complete curing. The next issue regarding SLA/DLP is the potential cytotoxicity of residual photoinitiators and uncured resin after the print.91

In contrast, conversion of 2D patterns into a genuine 3D structure is a challenge for IJP. Conventionally, layers printed by IJP are cured by simple solvent evaporation rather than by a chemical crosslinking. This creates a dried layer that can be dissolved and fluted when fresh ink of the next layer is deposited. Sometimes, the binders may incorporate contaminations that hinder the printing resolution. On the other hand, in case of DIW, a wide range of materials, from low to high cost, can be used only by maintaining printable apparent viscosity and shear thinning property. Basically, a lower temperature extrusion (typically room temperature) process, it can provide higher stability as higher temperature can cause oxidation or decomposition.92

A wide range of viscosity of the print material in DIW allows the reinforcements to mix up to 60–70%, which is significantly less in IJP. A higher mixing percentage helps in achieving a broad extent of functionality. In DIW, as the work material is generally a paste, gel, or liquid, reinforcements are therefore mixed uniformly using various stirring and deaeration techniques. So, the creation of voids in the composite can easily be eliminated.93

Process Outline of DIW

DIW of carbon-doped polymeric ink is a process of extruding formulated carbon-based ink using adequate size of needles and parameters over a substrate in the form of multiple layers. It is followed by the process of curing to obtain a usable product. Therefore, when it comes to preparing a sequence of steps for accomplishing 3D printing using the DIW technique, a thorough study on the fundamental needs of the process is required. A flow chart has been plotted in the Figure 3b to depict all the requirements of the process, which will create a clear picture of the needs with proper sequence.

Ink

It is worth mentioning that 3D architecture poses the biggest challenge in the development of inks as they include features that are self-supporting.3 Typically, inks are synthesized from polymeric, colloids, and ceramics suspended or dispersed in a liquid/solvent to create a viable, homogeneous ink of desired flow. For achieving functionality, powdered materials of different properties (e.g., conductors, permeable, semiconductors, harder materials) are added into the liquid-suspended inks. These inks are extruded outward through the microtips at the expense of mechanical or pneumatic force to form 3D objects.

In ink design, the essential rheological parameters yield stress, apparent viscosity, and viscoelastic properties (i.e., storage modulus [G′], loss modulus [G″]), which are configured in direct writing for fulfilling the specific purpose.12 Therefore, there are two considerations to prepare printable inks, the most essential key for successful manufacture through DIW.94

First, it is necessary to control fine rheological properties. Emulsions, gels, or pastes with shear-thinning behavior can flow through micronozzles without any ejection obstruction. Second, the strength and mechanical stiffness in inks would ensure the prior characteristics and build without any breakdown.

Thus, the properties of ink play a vital role in systems and components’ reliability, mechanical properties, and stability.95 These properties can be tailored by choice of a polymer matrix, as well as filler particle composition, size, and concentration. Ink characterization is also required for checking essential design rheological parameters. Finally, it is essential to know the techniques involved in the process of mixing or compositing.

Selection of matrix for carbon materials

Carbonaceous materials as fillers can impart extraordinary thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, and mechanical strength. Graphene and GO have features biocompatibility to the composite ink along with electrical and mechanical properties.30,37–40,96 The high dispersion quality of GO confirms it as a better candidate for reinforcing, and the high aspect ratios of these materials help to achieve better functionality in 3D structured composites.47,48,51 Carbon inks have a lower electrical conductivity of up to two orders of magnitude compared with metal-reinforced inks (103 S/m).97 However, they attain this conductivity level by weight at around 32%98 and without any high-temperature processing. Compared with metal particles, carbon-reinforced materials are inexpensive.

It is well known that reinforcements or fillers possess three aspects; filler size, filler shape, and concentration, which adversely affects the properties of ink. When the shape and size of the fillers in the composite are varied, the rheological properties become more complicated.

The mobility of the parent polymer are badly influenced by the friction between the same fillers, the friction between different fillers, and the friction between the filler and the polymer.99 Between the reinforcing agent and the polymer, the greater the specific surface area of the particles, the higher is the friction force.100 Decreased particle size can improve the tensile strength of matrices as well as Young's modulus value of printed composite.101,102 A higher concentration of fillers can impose high thermal and electrical conductivity.103,104

Polymers are broadly of two types, namely, thermosetting and thermoplastic. Thermosetting polymers are very stable and can withstand any severe environmental conditions. Compared with the latter, they are extensively used in various applications as insulators for micro to nanoscale composites. In addition, once the composite ink has dried, it cannot be dissolved, reprocessed, or compressed. On the other hand, most thermoplastics are unable to cover small particles evenly and continuously. Moreover, thermoplastic polymers are more easily damaged at elevated temperatures. Also, they exhibit low stiffness and strength.

In thermosetting polymers, irreversible crosslinking reactions occur, which converts the polymer into an insoluble one upon exposure to heat or any curing source. These polymers possess high stiffness, thermal stability, and strength. The selection of a thermosetting polymer over thermoplastic polymer minimizes the negative impacts of temperature fluctuations on the composites’ electrical and mechanical properties.105 Polyesters, epoxy-resins, acrylic esters, polyurethanes (PUs), and epoxy-polyesters are widely used thermosetting polymers that can serve as matrix material and a load bearer in 3D structured composites.

The inclusion of carbonaceous materials into these polymers may help in increasing their strength, hardness, brittleness, and the like. CF-mixed epoxy inks have shown a remarkable increase in Young's modulus up to 37%.106 CF, GO, rGO, and carbon greases can easily increase mechanical strength when mixed into these thermosetting polymers.94,106–109 It has also been observed that a remarkable loading percentage of carbon can impart conductivity to these insulated polymers.109,110 However, while thermoplastics are used as the matrix material, a group of researchers has used graphene for preparing thermoplastic-based composite ink compatible with DIW.111

Ink preparation

The initial challenging step for 3D periodic structure printing lies in the preparation of printable ink. Preparation of ink essentially follows two important criteria. First, a well-controlled viscoelastic behavior is expected so as to ooze through the micro nozzle and immediately retain the shape of the deposited structure. Second, they should contain a high-volume fraction of fillers and a good percentage of polymers to minimize shrinkage induced after the curing. A high filler percentage imparts the resisting ability generated by compressive stresses. Such stresses are caused by capillary action.3,12,95 The stable dispersion can be achieved by using compatible solvents, surfactants, dispersants, and stabilizers.

Isopropyl alcohol (IPA),94 dichloromethane (DCM),112 deionized (DI) water,113 ethanol,111 and acetone114 are some common solvents for dissolving polymers and for preparing a uniform solution of carbon materials. Researchers use a single solvent for the whole preparation process most of the time, for example, IPA has been used for both CF and poly(methyl-silsesquioxane) (PMSQ).108

For dissolution, ethanol, acetone, and water are used by many groups of investigators as single solvents. However, for polyvinyl butyral (PVB), dibutyl phthalate (DBP) has been used, and for graphene, ethanol was used in a single ink preparation. So, a combination of solvents can also be used for dissolving purposes.111 Similarly, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) was used for polyaniline (PANI), and water was used for GO.115

Solvents are basically an essential constituent in ink preparation. However, various users of DIW apply surfactant too, in an attempt to decrease the surface tension of the fluidic ink and maintain a better flowability. Sodium dodecyl sulfate was used with CNT-based ink for imparting high viscoelastic nature.113 Polysorbate, ethylene glycol butyl ether (EGB), and sodium dodecyl are some typical surfactants used by ink developers.111,113,116 Another constituent used for the preparation is dispersant. This is a different form of surfactant. Dispersant improves the separation of the particles in ink, whereas surfactant lowers the surface tension among two different phases of matter. Zinc protoporphyrin (ZnPP) and BYK 180 are common dispersants used by researchers to prepare carbon-based inks for DIW.94,114

Researchers use various mixing techniques, such as mechanical stirring, sonication, centrifugal mixing, and ball milling, to generate highly concentrated fluid with better extrusion ability, and shear thinning behavior.106,108,111,117 The standard process for ink preparation is, first, the dispersion of polymer and carbon into solvents separately by stirring, then adding these two solutions. Furthermore, ball milling, centrifugal mixing, and ultrasonication are commonly used for maintaining homogeneity to the dispersed materials. Most of the time, hobbyists use the combination of these techniques along with stirring to maintain the required level of dispersion and viscosity. In addition, certain responsive polymers and other additives are commonly used to improve the composition and viscoelastic behavior of the carbon inks.

Branched copolymer surfactant was used as a responsive polymer with 3% (w/v) prepared GO-based ink for printing self-supporting structures with high concentration (Fig. 4a).118 Various researchers have used plasticizers too in their composition for imparting process ability and flexibility while preparing the high viscous thermoplastic matrix-based ink.111 Stabilizers are the other constituents used for providing chemical stability to the formulated ink. Sometimes surfactant and matrix polymers themselves work as stabilizers.116,119 A large group of researchers employ Fumed silica to modify viscosity and termed the constituent as viscosity modifier.94,108,112

FIG. 4.

(a) Printing through 100 μm nozzle of low-concentration ink of GO/BCS and Microscopic view of printed part,118 (b) viscosity versus shear rate plot for showing ideal shear thinning behavior of DIW ink, (c) loss and storage modulus versus frequency plot of GO ink and proposed model present in the phase of formulated GO-based viscoelastic gel,131 (d) phase diagram showing ranges of printability and (e) Influence of three different printing speeds over print filament diameter of Nafion ink,133 (f) phase diagram of pressure as a function of concentration showing the ranges of print fidelity of CNT/PDMS ink,110 (g) print fidelity map, which is a function of flow stress, stiffness, and flow transition index of GO-based inks,134 (h, i) relationship of printed filament width, pressure, and filament diameter of experimental values and calculated values for 24 wt % pluronic hydrogel and 30 wt % pluronic hydrogel,135 (j) relationship of track/filament widths and √pressure of experimental values and calculated values for the ink at different printing speeds,136 (k) CFD simulation of CF/epoxy ink flow at 5 mm/min (top extrusion) and 15 mm/min (bottom extrusion),106 (l) simulated shear rate plots for different grains’ gel form black grains, job's tear seeds, mung bean, brown rice, and buckwheat [Adapted with permission]. BCS, branched copolymer surfactant; CFD, computational fluid dynamics; GO, graphene oxide; PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane.

Ink characterization

To check the compatibility or processing capabilities of prepared inks for DIW, rheological properties must be characterized. The rheological characteristics of ink can be determined by measuring the viscosity as a function of the shear rate, as well as the viscoelastic behavior of the polymeric composite ink. It can be evaluated through a direct reading of rheometer used, which includes viscosity versus shear rate and elastic moduli versus angular frequency plots. Formulated ink must show the behavior of shear thinning (Fig. 4b).

The explanation behind the high loading is that the reinforcement will change the rheological behavior of the host polymer by switching polymer–polymer interactions to reinforcement–polymer interactions and reducing the polymer mobility.120,121 Thus, a polymer with substantial reinforcement can exhibit much greater viscosity than a pure polymer. The addition of carbonaceous particles can eventually increase both the G″ and G′ of the liquid polymer. Sometimes, the G″ rises substantially faster than the G′ and in due course reaches the G′ value.122 Thus, a layer-by-layer curing method is needed to form a dense 3D structure during the printing process.

Ink with a viscosity range from 102 to 106 mPa-s has been found printable for the technique.123,124 Stresses of the inks are governed by Herschel–Bulkley model equation125:

| (1) |

where τ is the shear stress, K is the consistency constant, τy is yield shear stress, γ· is the shear rate, and n is the flow index.

The flow index should be <1 because of shear-thinning behavior. Ink will be fluidized and then extruded outward through the micronozzle, if the applied stress to the plunger is greater than the yield shear stress. By leaving the nozzle, the G′ and τy are retrieved by the ink, and thus it can maintain its shape and dimensions.126,127 However, if the applied stress exceeds the ink's compressive yield stress, pressure filtration occurs, resulting to ejection obstruction. It is also important to note that the ink should contain a high-volume fraction of colloid, to reduce the shrinkage induced by drying after the print.128

Among carbonaceous materials, GO-containing ink has shown remarkable printing abilities and viscoelastic characteristics. Therefore, it is widely used in multidisciplinary research areas.26,109,124,129,130 Dispersion of GO with water is the only solvent prepared for DIW because of its easy preparation, low cost, and environment-friendly nature without hazardous solvent evaporation. Water has less compatibility with other carbon materials as a solvent for formulating ink.26 However, there must be the dispersion of a high GO percentage in the ink for making it extrudable through the micronozzle. In DIW, GO ink with a concentration of up to 13.3 mg/mL can be used, which is far better than the limit (0.25–0.75 mg/mL) of IJP.131

The values of G′ reported for this 13.3 mg/mL ink ranged from 350 to 490 Pa, whereas for SWNT-based ink, the value of G′ has been found to be around 60 Pa for the same concentration. Values of G′ and G″ are higher in the used range of frequency. The ink was viscoelastic by nature, and in this case, displayed a gel-like behavior (Fig. 4c) with a very high G′ and viscosity.

This allows the ink to flow beyond yield point, making it ideal for DIW. However, some authors also reported higher concentration (80 mg/mL) of GO for 3D structuring.26 On the other hand, CF reinforcing can promulgate high G′ with less wt % addition, but random alignment in fibers hinder its functionality. Again, 80–90% CF alignments achieved, reflected a phenomenal increase in composite strength.106

Print fidelity prediction

Successful printing requires ink with adequate rheological properties and the instrument's right settings. DIW has three elements—ink, dispensing system, and three-axis positioning stage, which requires optimization. First, sufficient ink rheological characteristics must be displayed in the printing. Yield stress (σy) and G′ with apparent viscosity (μ) of the ink are crucial parameters that govern printing outcomes through DIW, as already discussed in the earlier section. Second, the dispensing system (i.e., pressure or force source and nozzle size) helps in determining the volume flow rate of dispensed fluid.3,12,95 Thus, the nozzle diameter (D) and applied pressure (ΔP) are the prime factors for determining volume flow rate. Finally, the motion-control three-axis positioning stage, attached to the syringe/nozzle system, controls the movement of the syringe during the extrusion of ink.

The velocity (v) of the dispensing syringe/nozzle system helps in determining the mass of the ink extruded per unit length. The stage also offers control in the perpendicular direction to the layer of printing (i.e., Z-direction).

When the ink is dispensed out through the nozzle, the width of extruded filament (d) totally depends upon the parameters mentioned above (D, ΔP, and μ). Nozzle/substrate distance (h) and nozzle length (l) also play a significant role with all discussed parameters to achieve good print fidelity.132 It may be concluded that adequate studies on extruded filament width, affected by D, ΔP, and μ, are required for predicting print fidelity. Many researchers have performed the prediction through an experimental way, where the printing has been performed numerous times by varying the working parameters in a regular pattern.

The method of keeping few parameters constant and varying others is widely accepted for this print fidelity prediction. SWNT and Nafion-based ink printability was predicted by keeping nozzle diameter (0.29 mm) and printing speed (12 m/s) constant under varying pressure and Nafion concentration (Fig. 4d, e).133 CNT/polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) composite ink stability has been improved by varying CNT loadings, pressure, and gap span in the printed gap-spanning model.

An optimum printing speed has been concluded with various gap spans and the loadings of CNT (Fig. 4f).110 A number of oscillatory sequence tests, Large Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (LAOS)-to-Short Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) recovery tests, and amplitude sweeps were used for GO ink to examine the main parameters (stiffness, flow transition index, and flow stress) that affect printability.

A quantified printing window has been demonstrated with the help of this oscillatory rheology (Fig. 4g).134 Another method used for predicting fine printability is mathematical modeling, where an equation has been derived in terms of pressure, extruded line width, nozzle diameter, and printing speed. The mathematical equation formed by using equations of rheometer and shear rate in the capillary is135:

| (2) |

where d is the extruded line width, D is the diameter of the nozzle, P is a pressure change, μ is viscosity, l is nozzle length, V is the printing or nozzle moving speed, and n is the index in the power law. Line width study has been carried out by matching the theoretically calculated values and experimental values at particular printing speeds, using the proposed equation.135,136

Pluronic hydrogel and PANI-based inks were investigated so far, where a great match was seen in experimental and calculated values of filament width with respect to nozzle diameter and pressure (Fig. 4h–j). Another technique for checking the conformity of the printing is “numerical simulations.” Many researchers have used computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation tools to check the stresses, pressure, and velocity distributions over the extrusion nozzle.

A velocity simulation has been carried out for 8 vol % CF-doped ink using the Carreau fluid model at two simulated print speeds, 15 mm/min (bottom) and 5 mm/min extrusion (top) (Fig. 4k).106 Using the Bird–Carreau model, printability was examined for pastes formed using five food grains, where the width of the filament was measured to know the best printable parameters among simulated results of different grains (Figs. 4l and 5a).137 Similarly, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel print fidelity has been checked to finalize the optimum extrusion nozzle using CFD tool of Ansys.139

FIG. 5.

(a) Values of viscosity taken at eight different locations in Z-direction points for all five grains,137 (b) numerical simulation of CF cored ink,138 (c) rGO/CNT-based ink contact angle measurements; over stretchable sheet and dries rGO/CNT,143 (d) curing temperature examination for optimizing quality of printed surface of single layer,144 (e) schematic representation of the UV-directed DIW technique.112 (f–h) Schematic of MWCNT/PDMS ink formulation and DIW, apparent viscosity versus shear rate plot and G′ and G″ versus frequency plot for CNT/PDMS ink,110 (i) schematic illustration of multilayering of CNT and Nafion-based inks, (j) viscosity versus shear rate plots for varying Nafion concentrations (k) G′ and G″ versus shear stress curves for 60 wt % Nafion-based ink133 [Adapted with permission]. G′, storage modulus; G″, loss modulus; rGO, reduced graphene oxide; UV, ultraviolet.

A different kind of DIW printing was done with CF-based core–shelled ink, where a numerical simulation determined an optimum extrusion angle. This method was used to control d/D (d is the diameter of CF core–shell and D is the syringe or silicone carbide [SiC] ink diameter) ratio of the core–shelled ink for suitable extrusion (Fig. 5b).138

Substrate selection

The contact angle gives evidence of surface energies for both the polymeric ink and the substrate surface and accounts for the wetting ability of the surface by ink. When ink droplet spreads over the surface with a contact angle <90°, surface wetting occurs. The angle becomes 0° if the droplet spreads out completely and absolute wetting happens. Thus, surface wetting can be best measured by contact angle measurement.140,141 The greater the contact angle, the lower the wetting ability of the ink over the substrate.142 Hence higher wetting surface signifies the best substrate as it can sustain the ink over it. For printing rGO and CNT-based ink over stretchable silicone elastomer substrate, the contact angle was found to be 51.1°, which confirmed better wetting ability, and perfect substrate (Fig. 5c).143

Kapton,113 glass,114 soda-lime glass,119 and silicone wafer116 are different substrates that researchers have used for printing carbon material-based inks. Measuring contact angle with respect to print line position is another discovered way for checking the stability and wetting of printed lines over different substrates.144

Second, the work of adhesion analysis can give another clue for selecting a substrate. The Young–Dupré work of adhesion equation is as follows:

| (3) |

where WSL is the work of adhesion, γL is the surface tension of the ink, and θ is the contact angle between surface and ink.141 A higher value of WSL confirms more remarkable sticking ability of ink over substrate surfaces.143,145

Layer bonding

Interfacial bonding strength between layers is another key factor for achieving accurate print. Inks must have residual solvent or wetting agent in the extruded filaments to guarantee the new deposition of material bonds over the previously printed regions. If the bonding energy is inadequate, the areas may adhere, but there will be a clear distinction between fresh and previously deposited ink. This may lead to a fractured surface that allow the layers to separate easily.64 The T-peel test of printed polymeric ink gives the best experimental results for evaluating interfacial layer bonding. Ecoflex 00-30-based silicone polymer-printed T-samples of different cure times have been tested and showed remarkable increase in tensile peel strength.

A Peel Strength Visualizer was created in MATLAB to show how cure time affects peel forces between part layers.146 Layer shear strength checks using three-point or four-point flexural tests may be another better option to predict the interlayer adhesion of DIW printed samples by providing statistical data.147,148 The time-dependent chemical vapor infiltration technique has been used for increasing flexural strength and thus interfacial adhesion.23 Additional UV curing was reported to gain high interfacial strength for UV-assisted DIW printed samples.149 Apart from this, the prediction of thickness-dependent interfacial strength has also been analytically modeled and simulated based on the finite element method.150

Curing

After or during the print, perfect curing or drying is needed to give a robust shape to the 3D structure; thus, curing is undoubtedly an essential part of DIW. Sometimes the G″ rises faster than the G′ and very easily reaches the G′ value. Thus, layer-by-layer curing forms a dense 3D structure during the printing process. In other words, it can be said that lesser delay in the drying process just after the print can provide a robust shape. For accomplishing this, heated platforms113,119 are used and for UV curables, UV lamps are employed at the periphery of the extrusion nozzle (Fig. 5e).112 Curing techniques are classified commonly into four types: (1) Thermal,106,109 (2) Photonic,151 (3) Microwave sintering,152 and (4) UV Curing.112,114

Thermal sintering is one of the oldest curing techniques used for curing inks. The solvent is released by heating composite inks to a specified temperature so that the particles can combine in continuous links. Typical polymeric composite inks sintering temperatures vary from about 100°C to 250°C depending upon the distribution of particle size and shape.106,109,113,133

The organic solvents evaporate during curing, leaving behind carbon particles and potentially some organic promoters of adhesion. Since the process involves direct heating, lower melting point substrates, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) cannot be used at elevated temperatures of curing.153 At lower sintering temperatures, the incomplete removal of solvents can impart uneven solidification.

The uneven solidification can affect the mechanical strength as well as conductivity. Studies have shown that a gradual rise in temperature provides higher conductivity.154,155 The latest advances in adding curing agents within the ink formulation showed that polymeric carbon inks could be cured at room temperature.94,108,111 Apart from it, the cure time is as less as around milliseconds for a large mass of solid printed materials through xenon lamps, which is termed as photonic curing. These two mechanisms make it possible to use paper and other substrate materials sensitive to temperature.151

Traditionally, photonic curing is limited to the poor heat sink type substrates (e.g., paper, plastics). However, graphene/ethyl cellulose (EC) ink curing was made possible with a xenon lamp over silicone, a substrate with high thermal conductivity.156

Conductive 3D structures of silver, CNT, graphene, and copper have shown better results when cured with the microwave. The sintering time can considerably be reduced to 240 s using the microwave cure technique. The limitation of the method is on its penetrating depth of curing, which is around 1.3–1.6 μm. In addition, substrates that react with microwaves cannot be used in this sintering technique.152,157 UV curing is one more technique for curing polymeric ink, a photochemical process that uses particular intensity of UV lights (generally 405 nm). The difference from others is in the polymer formulation only. The formulation contains monomers and oligomers with a small quantity of photoinitiators, making it curable when exposed to UV.158,159

Generally, curing temperature and duration are determined by the hit and trial technique (Fig. 5d).144 However, for evaluating curing temperature and time of sintering, the study of reaction kinetics is another way, which helps in saving resources. The kinetics can be obtained by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) isothermal and nonisothermal tests. Thus, through DSC analysis, Tg of the formulated composite ink is obtained, and usually, the curing temperature is slightly above (10–30°C) the obtained transition temperature.156,160 The curing time can be achieved by DSC, when a fresh composite sample is subjected to heating up to the fixed curing temperature and holding that temperature constant for a particular period.161,162

Notably, polymers with high filler content and smaller particle size show the least activation energy, which results in faster curing at the start and diminishes later, as demonstrated with epoxy resin.163

3D Printing of Composite Inks

In this section, few carbon-based composites’ fabrication will be discussed as examples. The discussions will be based upon information gathered from articles published in different journals worldwide. All previously discussed topics shall be taken into consideration so as to gain a vivid picture on the fundamental processes involved in 3D printing of carbon-doped polymeric composites, using the DIW technique and understand any further necessities thereof. This review shall primarily focus upon topics pertaining to: type of DIW, solvents, and the polymers used; viscosity plots with respect to strain rate; effects of moduli; and the print fidelity tests.

CNT-based composites

MWCNT/PDMS nanocomposite

Pneumatic DIW technique with nozzle having 290 μm in diameter has been employed for printing woodpile and mesh structure of MWCNT/PDMS composite ink.110 The ink formulated for it, with varying percentages (5–9 wt %) of MWCNT and PDMS elastomer, was demonstrated, where IPA served as a solvent. A proper sequence of ink formulation can be observed in Figure 5f. By incorporating 7 wt % MWCNT, the doped ink showed a better retention feature with excellent shear-thinning behavior (Fig. 5g). An increase in G′ and G″ can be seen with the increased percentage of CNT (Fig. 5h).

CNT/Nafion nanocomposites

Multilayerings of CNT ink and Nafion ink have been done for preparing these composites (Fig. 5i).133 IPA and water for Nafion (sulfonated tetrafluoroethylene-based fluoropolymer) and NMP and dimethylacetamide for SWNT were used as the solvents in the formulation of CNT-based inks. Inks with <20 wt % and >70 wt % of Nafion were found nonprintable through screw-based DIW 3D printer (Fig. 4d). Ink with 60 wt % of Nafion exhibited the solid-like yielding nature at considerable stress of 50 Pa. The said finding confirmed that the ink is noncollapsible after extrusion through 290 μm-sized needles. This can be easily observed through modulus versus shear stress plots (Fig. 5j, k). The CNT served as a bond strength intensifier in multilayering with a value of 18 kPa.

Graphene-based composites

Graphene–EC–nitrocellulose nanocomposite

Two solvents, glycerol, and ethyl lactate, were used for the formulation of graphene-based nanocomposite ink.164 Ink with 15 vol % has shown the required shear-thinning behavior (Fig. 6b). The fabrication of a microsupercapacitor has been accomplished using this work through the displacement-based DIW technique with 210 μm needles (Fig. 6a). The presence of nitrocellulose in ink helps in inducing mechanical strength because of its hydrophobic nature. On the other hand, the glycerol used in ink shows a hydrophilic behavior, and its increased percentage helps in generating porosity, thus reducing conductivity. High glycerol content leads to higher thickness of the printed film (Fig. 6c).

FIG. 6.

(a) Microscopic view of DIW employed for graphene–EC–nitrocellulose ink, (b) viscosity versus shear rate plots for varying glycerol contents and (c) thickness versus glycerol content of printed films for graphene-based ink with varying glycerol percentage (before and after annealing),164 (d) macro strain sensor attached over forearm and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) image of the same printed using GO/PDMS ink, (e) schematic representation of GO/PDMS ink formulation and DIW of micro and macro sensors, (f–h) GO/PDMS ink characterization; viscosity versus shear rate, G′ and G″ versus shear stress and G′ and G″ versus shear strain plots, (i) emulsification of PDMS submicrobeads through shear mixing, (j) SEM image of packed PDMS microbeads after curing, (k) size distribution of generated microbeads as a function of frequency,116 (l) viscosity measurements of graphene/PVB ink for varying graphene percentage, graphene solution and base polymer, (m, n) 3D-printed graphene/PVB nanocomposite scaffolds with varying sizes and shapes through DIW.111 (o) Storage modulus measurements of cured CF/epoxy hybrid ink and base epoxy, (p) storage modulus at room temperature of epoxy and hybrid ink, (q) close view of 3D printing of heat sink, (r) printed heat sink,165 (s, t) optical images for DIW of CF/SiC/epoxy hybrid ink107 [Adapted with permission]. EC, ethyl cellulose; PVB, polyvinyl butyral; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; SiC, silicone carbide.

GO/PDMS nanocomposite

Over silicone wafers, strain sensors were printed (Fig. 6e), in which GOs were the ink's prime constituent.116 PDMS was used as the matrix material with GOs as reinforcement in the formulation. DCM and water were used as solvents for PDMS, GO, respectively, and polysorbate as a surfactant for the whole composition. The whole ink preparation process is well represented in Figure 6d. The system employed for the fabrication of these sensors was a pneumatic DIW 3D printer with 50-, 100-, and 200-μm-sized tips.

Higher viscosity has been achieved in this formulation because of the formation of microbeads of PDMS. The formation of the beads was carried out by oil/water phase emulsion technique (Fig. 6i, j). High shear mixing of PDMS/DCM solution and water/PVA solution causing emulsification by forming microbubbles, and seen as microbeads after the curing, have been confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (Fig. 6k). Size distribution in the plot of beads diameter as a function of frequency can be observed in Figure 6i. The formulation showed a higher value for apparent viscosity of around 1242 Pa-s at 0.009 s−1 shear rate (Fig. 6f). G′ values of formulated ink showed high compatibility for DIW (Fig. 6g).

Graphene/PVB nanocomposite

Ink formulation for the graphene-based composite uses a polymer PVB with DBP, which acts as a plasticizer or solvent.111 Another solvent, ethanol, is used for providing uniformity in graphene nanoplatelets. A pneumatically controlled DIW has been employed for printing scaffold cuboids using 300-, 400-, and 500-μm nozzles (Fig. 6m, n). Viscosities at the higher and lower shear rate observed for inks are 20 and 1000 Pa-s, which apparently confirmed the shear-thinning behavior of ink and the compatibility for DIW (Fig. 6l). The surfactant EGB was used in the formulation to improve wettability in solvents by getting attached as hydrogen bond to an oxygen-containing functional group. Consequently, it enables the prepared ink to extrude uniformly, irrespective of its high viscosity.

CF-based composites

CF-SiC core–shelled composite

CF-SiC core–shelled composite was prepared using displacement type DIW in the shape of alphabet S.138 For generating structures through it, two separate inks viz. CF-based and SiC-based, were formulated. A common solution of polyethylene glycol (PEG), tetramethylammonium hydroxide, distilled water (solvent), and guar gum have been used for preparing both inks. CF-based ink was poured first into a cylindrical mold and then frozen to obtain a rod-like structure. SiC-based ink was then poured into the syringe, the CF ink rod was placed in between and then thawed at a particular temperature for yielding a better extrusion through the nozzle of 0.6 mm diameter.

CF-epoxy hybrid composite

Epoxy is used in the matrix for the fabrication of CF and graphene nanoplatelets-based hybrid composite ink.165 A 7.6 wt % of CFs and 9.3 wt % of graphite have been mixed with epoxy in a planetary centrifugal mixer. Apparent viscosity of 2.5 × 104 Pa-s was measured for the ink with an increment observed of around 50% in G′ for fine extrudability (Fig. 6o, p). Formulated hybrid ink was extruded outward through 100–125 μm-sized tips in the form of a heat sink using an air-powered DIW 3D printer (Fig. 6q, r).

Applications

This review aims to focus upon the significance of DIW as a 3D printing technique in polymer/carbon composites. It also highlights on the significant findings available from ongoing researches of today and the basic requirements for DIW 3D printing techniques relating to the development of polymer/carbon composites. A detailed description of recent investigations, discussed earlier, is provided in Table 2. It is evident from the said table that the most common applications of 3D printed carbon composites lie in the fields of electronics, structural, and biomedical engineering.

Table 2.

Three-Dimensional Printed Carbon-Based Composites Through Direct Ink Writing with Details

| S. No. | Reference and author | Doped carbon material | Base polymer | Inks preparation technique | Curing | Diameter of dispensing nozzle (μm) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Aïssa et al.20 | SWNT (0.5–5 wt %) | UV curable epoxy | Stirring, centrifugation, and sonication | UV-curing | — | Patch antenna operating at S-band frequency |

| (2) | Wang et al.21 | Graphene (0.1–0.5 wt %) | Polyvinylidene Fluoride | Sonication | Heating bed (70°C) | — | Sensitive piezoelectric film |

| (3) | García-Tuñón et al.22 | GO (0.6 vol %) | PVA | Planetary centrifugal mixer | 23°C during print and freeze-dried at liquid nitrogen | 510 | — |

| (4) | Lewicki et al.106 | CF (3–15 vol %) | Bisphenol-F epoxy resin | Centrifugal mixer and vacuum desiccators | Thermal (80°C with substrate and 120°C without substrate | 250 | Mechanical analysis (orthotropic), conductivity, global flow CFD modeling |

| (5) | Compton and Lewis107 | CF (10 wt %) | Epoxy (EPSON 826) | Planetary mixer | Thermal (100°C with substrate and 220°C after peeling out the substrate) | 200, 410, 610 | Mechanical analysis |

| (6) | Franchin et al.94 | CF (17 vol % and 23 vol %) | PMSQ | Stirring over a hot plate | Room temperate | 410, 580 | Mechanical strength (bending) |

| (7) | Franchin et al.108 | CF (17 vol %) | PMSQ | Stirring | Room temperature | 410 | Mechanical strength (compressive) |

| (8) | Pierin et al.109 | GO (0.025–0.1 wt %) | Silicone resin preceramic polymer | Stirring and sonication | Printing in a water bath then heated up to 200°C after print | 200 | Mechanical and electrical analysis |

| (9) | Luo et al.110 | MWCNT (5–9 wt %) | PDMS (Sylguard 184) | Stirring and vacuum desiccators | Thermal (80°C) | 290 | Mesh structure for LED illumination, stain sensing, electrothermal actuators |

| (10) | Huang et al.111 | Graphene Nanoplatelets (GNPs) (25 and 50 wt %) | EGB | Sonication | Room temperature | 300, 400, 500 | Anisotropic electrical properties |

| (11) | Lebel et al.112 | SWNT (0.5 wt %) | PU | Stirring over hot plate and three roll mixer mill | UV curing (intensity 50 mW/cm2) | 150, 100 | Helical-shaped flexible electrical connections (conductivity 10−6 S/cm) |

| (12) | Chen et al.113 | SWNT | PVA | Stirring, Sonication, and hot plate stirring | Platform thermal curing (100°C) | 200 | Supercapacitor |

| (13) | Farahani et al.114 | SWNT (1 and 2 wt %) | UV curable epoxy | Stirring over hot plate and three roll mill mixer | UV-curing | 100 | Helical strain sensor |

| (14) | Wang et al.115 | rGO | PANI | Stirring | — | 400–600 | Supercapacitor |

| (15) | Chizari et al.117 | MWCNT (30–40 wt %) | PLA | Ball milling | Room temperature | 200 | EMI shielding |

| (16) | Loh et al.119 | Graphene | EC | Centrifugation | Over hot plate (50–450°C) in ambient condition | 150 | Gas sensing |

| (17) | Shi et al.116 | GO | PDMS (Sylgard 184) | Rotor mixer, planetary centrifugal mixer | Room temperature | 50, 100 and 200 | Tactile sensor |

| (18) | Luo et al.133 | SWNT (5–50 wt % approx) | Nafion | Mixing and heating | Heating under vacuum (120°C) | 290 | Pressure sensor |

| (19) | Xia et al.138 | CF (22.4 wt %) | PEG | Stirring | Printing at 22°C temperature | 600 | Mechanical analysis |

| (20) | Jiang et al.143 | SWNT and rGO (10, 25, and 50 wt %) | Polypropylene (Cellink start) and PDMS (Sylguard 184) | Planetary mixer and sonication | Thermal curing | 960, 460 | Supercapacitors |

| (21) | Guo et al.166 | MWCNT (0.1–5 wt %) | PLA | Micro-compounder and sonication | Thermal curing (50°C) | 150 | Helical liquid sensor |

| (22) | Chizari et al.167 | MWCNT (40 wt %) | PLA | Ball milling | Room temperature | 100–330 | Liquid sensor |

| (23) | Secor et al.164 | Graphene | Nitro cellulose and EC | Sonication | Thermal (over hot plate 70°C and oven 100°C) | 210 | Supercapacitor |

| (24) | Nguyen et al.165 | CF (7.6 wt %) and GNPs (9.3 wt %) | Epoxy resin (EPSON 862) | Planetary mixer | Thermal curing (150°C) | 100, 125 | Heat sink |

| (25) | Martínez-Vázquez et al.168 | Graphite (30–50 wt %) | CMC | Planetary mixer | Room temperature | 250 | Support for brittle ceramic parts |

| (26) | Muth et al.169 | Carbon grease | Platinum silicone liquid rubber (Ecoflex) | Planetary mixer | Curable polymer (room temperature) | 410 | Strain sensing |

| (27) | Postiglione et al.170 | MWCNT (0.5–10 wt %) | PLA | Stirring and Sonication | Ventilated oven | — | Electrical circuit |

| (28) | Rocha et al.171 | Graphene (2.5–6 wt %) | Pluronic F-127 | Planetary centrifugal mixer | Frozen at liquid nitrogen and thermal reduction at 900°C | 100–1000 | Electrochemical energy storage device |

| (29) | Liu et al.172 | GO (50 wt %) | PANI and PEDOT:PSS | Stirring, sonication, and centrifugation | — | 100 | Micro-supercapacitors |

| (30) | Jakus et al.173 | Graphene (20, 40 and 60 vol %) | PLG and DBP | Sonication | Room temperature | 100, 200, 400 and 1000 | Nerve conduit implantation, subcutaneous scaffold implantation, electrical application |

| (31) | Huang et al.174 | Graphene and GO | Pluronic and PU | Sonication | — | 410 | Differentiation of neural stem cells |

| (32) | Ahammed and Praveen175 | MWCNT | PVA | Stirring and sonication | Room temperature | 600, 800 and 1000 | Optimization and conductive part |

| (33) | Wang et al.148 | GO and CNT | EC | Stirring and centrifuge | Vacuum Desiccator and room temperature | — | Supercapacitor |

| (34) | Guo et al.150 | Carbon paste | Epoxy | Centrifuge | Room temperature | 250 | Strain sensor |

| (35) | Shakeel et al.176 | Carbon | PEDOT:PSS | Commercial ink | Thermal (140°C) | 750 | Thermocouple |

| (36) | Guo et al.177 | CF | Epoxy | Planetary mixer | Room temperature | 440 | Mechanical strength and shape memory |

CFD, computaional fluid dynamics; CMC, carboxymethyl cellulose; CNT, carbon nanotube; DBP, dibutyl phthalate; EC, ethyl cellulose; EGB, ethylene glycol butyl ether; EMI, electromagnetic interference; GO, graphene oxide; GNPs graphene nanoplatelets; MWCNT, multiwalled CNT; PANI, polyaniline; PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PLG, polylactic-co-glycolic acid; PMSQ, poly(methyl-silsesquioxane); PU, polyurethane; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol; rGO, reduced graphene oxide; SWNT, single-walled CNT.

Electronics

Three-dimensional printing creates geometrically suitable electronic models in lesser time. When polymers are mixed with carbon materials, 3D printed polymer composites act as smart electronic devices and used in various ways. One of them is sensors, including strain, gas, solvent, and pressure sensing.114,119,133,167 A sensor is an object that detects events or environmental changes and transfers the subsequent real-world data to the system. Sensors have been widely applied in manufacturing and appliances, aerospace and aircraft, medicine and medicinal equipment, and robotics with micromachinery growth and developments in microcontroller technologies.

The present research has been focusing on the use of DIW 3D printing technology for sensors production. Strain sensors are used to track electrical changes due to mechanical deformations.150 Similarly, gas sensors and solvent sensors detect the resistance change when immersed in the gaseous and solvent environment, respectively.119,167 Sandwich pressure sensor printing was done by using SWNT-based ink.

Here, the first five layers were SWNT-based ink, the next ten layers were of Nafion ink, and again the next five layers were of SWNT ink. A remarkable interfacial resistance has been observed for this sensor of about 45.52 ohms with a perfect capacitance level (0.168 mF/cm2). The estimated high sensitivity of this pressure sensor was recorded as 5.95 mV/N (Fig. 7d, e).133

FIG. 7.

(a–c) Images of assembled DIW 3D-printed alumina sphere using graphite/carboxymethyl cellulose as support; Printed and Sintered, G′ versus oscillation stress plot of graphite/carboxymethyl cellulose ink,168 (d, e) sensing performance tests for SWNT-Nafion composite; test points over printed part and sensitivity plot measured at first point,133 (f–i) top view printed soft sensors at different speeds and electrical resistance versus strain plot, and resistive change measured for different finger movements of DIW 3D-printed sample using carbon grease/platinum silicone liquid rubber composite ink,169 (j–l) optical image of printed supercapacitor (flat and bended), specific capacitance measurements at various current densities, and cyclic performance of supercapacitor,113 (m, n) galvanostatic charge/discharge and specific capacitance versus current density plots of printed electrodes using CNT-doped polymeric ink,143 (o, p) circuit composed of an LED and conductive woodpile structure showing the response of LED upon applying pressure over the surface.110 (q) 3D model for the DIW process, as printed sample, after freeze drying and sintered electrode sample of DIW 3D-printed graphene-based ink,171 (r, s) thermal diffusivity at different temperatures, and evaluated thermal conductivity of printed samples using hybrid ink at varying temperatures, modeling evaluations of heat sink: cured heat sink, resulted heat flux of printed sample, infrared thermal imaging of printed samples, and comparison with simulation results.165 [Adapted with permission.] SWNT, single-walled CNT.

Helical strain sensors printed through DIW with MWCNT-based ink showed a remarkable sensitivity of gauge factor 22.114 PDMS ink doped with MWCNT was used for printing mesh structures that showed a remarkable strain sensing with high conductivity.110 Carbon grease-doped platinum silicone liquid rubber ink has also been used for preparing strain sensing (Fig. 7f, i).169 Varying resistance has been observed for different sensors printed at varying speeds (Fig. 7g, h). Another kind of sensor that is fabricated through the technique is the gas sensor. Resistivity change at two points of printed sample is generally observed in a particular gas environment to check responsiveness.

Graphene-based composite ink has been used for structuring gas sensors, which is demonstrated for hydrogen and methane. Responsiveness observed was seven times more for hydrogen when compared with methane.119 Helical liquid sensors have also been structured with MWCNT-based ink and demonstrated for four solvents. Its unique structure with carbon materials greatly influences sensing liquids by providing a high surface area when immersed in the liquid. These sensors’ swelling causes a resistive change due to immersion in solvents.166 One more CNT/PLA-based composite was printed for sensing liquids. A decrease in relative resistance change due to such parameters as interspacing of filaments, thickness, and diameter of filaments were observed. A decrease in RCC showed a higher sensitivity for this helical DIW 3D printed solvent sensors.167

Apart from sensing, carbon-based inks were printed for various other applications too, as for example, flexible conductive electrical connections,112 electrical circuits,170 supercapacitors,113,115 storage device,172 electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding,117 patch antenna,20 and heat sinks.165

SWNT-based inks were used for printing super capacitors, which showed a remarkable level of capacitance (15.34 F/cm3) (Fig. 7j). Only a 34.9% decrease in capacitance was observed with increasing current density (Fig. 7k). A 97.7% capacity retention has also been observed for the capacitor (Fig. 7l).113 A combination of rGO and SWNT in ink also showed a high-level capacitance after printing through DIW. An automatic adjustment of around 8 F/gm has been observed in specific capacitance, which resulted to 40% reduction in heat.

Charge/discharge profile shows that around 25% CNT-based capacitor has superior capability of handling power (Fig. 7m, n).143 Most investigative studies reported that supercapacitor fabrication is quite a common application through DIW, where graphene, GO, and rGO, apart from CNT, have been used as the doping agent.115,164,172

Flexible helical-shaped high conductive (10−6 S/cm) connections were printed by using SWNT-doped ink with a very small quantity of CNT (0.5 wt %).112 MWCNT-doped PLA ink had shown a remarkable conductivity of around 23 S/m for illuminating LED bulbs.166 MWCNT/PDMS-based composite ink extruded through the technique was also demonstrated for LED illumination (Fig. 7o, p).110

Graphene-doped ink has been used for structuring electrochemical energy storage devices (Fig. 7q).171 Graphene/epoxy ink with around 9.6 wt % loadings was printed for the application of heat sink. Printed samples have shown two times more diffusivity than base epoxy, with ten times conductivity (Fig. 7r, s). A temperature gradient of 40°C has been demonstrated, with a high range of heat flux (3.3 × 10−4 to 1.3 × 10−2 W/mm2) (Fig. 8a).165

FIG. 8.

(a) Epoxy heat sink thermal imaging and simulation results,165 (b, c) tensile stress versus strain curves for CF/SiC/epoxy and epoxy 3D-printed part and compressive stress versus strain curves for DIW-printed honeycomb structures,107 (d, e) DIW of carbon fiber reinforced hybrid ink and top view of printed scaffold,108 (f, g) stress versus strain curve and tensile test results for CF/silica/epoxy-printed sample for mechanical properties evaluation,106 (h, i) stress–strain and load–displacement curves for evaluation of mechanical properties for CNT/PDMS printed sample,110 (j) stress–strain curves of graphene/PVB DIW-printed sample and pattern of printing,111 (k) optical images of DIW-printed sample of silicone resin preceramic polymer without GO and with GO reinforcement,109 (l, m) schematic representation of graphene/PLG ink preparation, printing, and possible applications and elastic moduli obtained from tensile results; (n) scanning laser confocal three-dimensional reconstructed projections of live stained (green) and dead stained (red) on various printed scaffolds of 1 and 14 days after seeding.173 [Adapted with permission.] PLG, polylactic-co-glycolic acid.

Structural

In structural applications, materials should have high mechanical properties. By employing DIW technique, high-strength materials have been printed in different complex 3D structures for various fields, for example, aerospace and energy transmissions. Again, carbon-doped composites withstand high loads when processed through DIW. Carbon-based 3D structured composites exhibit a high strength-to-weight ratio with incredible stiffness as carbonaceous materials have high surface area.47 GO, CFs, and CNTs are the prime carbon-based materials, which helps in imparting high mechanical properties.94,109,110

CF-based 3D printed composite structure has shown the least porosity level (30.9% ± 1.2%) with PEG and guar gum as matrix and high mechanical properties. Fracture toughness of 2.71 ± 0.25 MPa and high bending strength of 123 ± 15 MPa have been observed in this patterned composite.138 With 10 wt % of CF along with SiC, outstanding tensile strength and compressive strength of 3.8 ± 1.23 MPa were observed (Fig. 8b, c).107 CF with SiC has also shown a high compressive strength when reinforced in PMSQ; however, a 75% ± 2% of porosity level was observed (Fig. 8d, e).108

Around 37% increment in Young's modulus with high tensile strength was demonstrated by aligning 80–90% CF in the extruded composite ink (Fig. 8f, g).106 Graphite-doped ink printed through DIW has shown a high strength as secondary support structures (Fig. 7a, b).168