Abstract

In the past 50 years, our understanding of the biochemical and molecular causes of mitochondrial diseases, defined restrictively as disorders due to defects of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC), has made great strides. Mitochondrial diseases can be due to mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) or in nuclear DNA (nDNA) and each group can be subdivided into more specific classes. Thus, mtDNA-related disorders can result from mutations in genes affecting protein synthesis in toto or mutations in protein-coding genes. Mendelian mitochondrial disorders can be attributed to mutations in genes that (i) encode subunits of the RC (“direct hits”); (ii) encode assembly proteins or RC complexes (“indirect hits”); (iii) encode factors needed for mtDNA maintenance, replication, or translation (intergenomic signaling); (iv) encode components of the mitochondrial protein import machinery; (v) control the synthesis and composition of mitochondrial membrane phospholipids; and (vi) encode proteins involved in mitochondrial dynamics.

In contrast to this wealth of knowledge about etiology, our understanding of pathogenic mechanism is very limited. We discuss pathogenic factors that can influence clinical expression, especially ATP shortage and reactive oxygen radicals (ROS) excess.

Therapeutic options are limited and fall into three modalities: (i) symptomatic interventions, which are palliative but crucial for day-to-day management; (ii) radical approaches aimed at correcting the biochemical or molecular error, which are interesting but still largely experimental; and (iii) pharmacological means of interfering with the pathogenic cascade of events (e.g. boosting ATP production or scavenging ROS), which are inconsistently and incompletely effective, but can be safe and helpful.

Keywords: Mitochondrial diseases, Respiratory chain defects, Energy failure, Oxidative stress, Symptomatic therapy, Pharmacological therapy, Gene therapy

In the 46 years since the description of the first mitochondrial disease, Luft syndrome [1] and in the 20 years since the discovery of the first pathogenic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations [2, 3] the field of mitochondrial disorders has expanded (and continues expanding) at an unprecedented pace. In fact, the term “mitochondrial medicine” introduced in 2004 by Rolf Luft [4], is widely accepted and two books with this title have already appeared [5, 6]. Despite this extraordinary progress, our task is arduous because the two subjects of this review, pathogenesis and therapy, are the least developed, especially when it comes to mtDNA-related disorders. After a “taxonomic” introduction to the mitochondrial diseases, we will attempt to merge for each group of diseases, what little we understand about pathogenesis with what little we can do about treatment.

10.1. Classification of the Mitochondrial Diseases

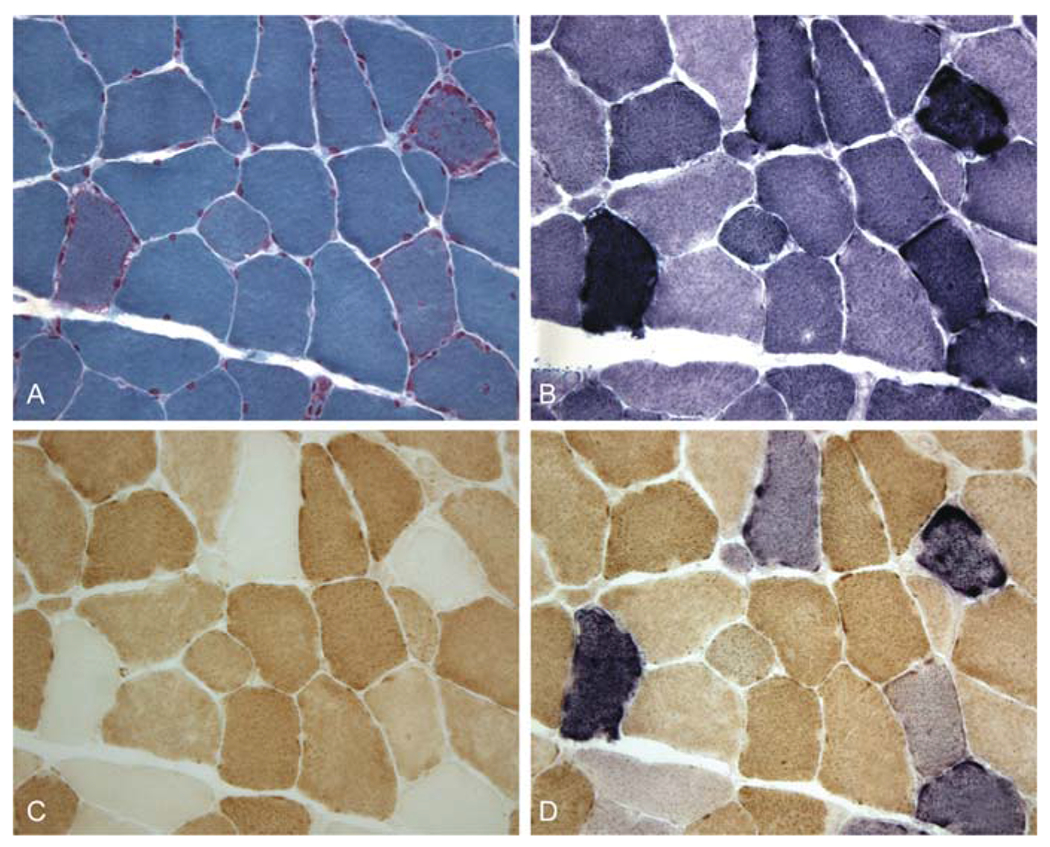

Mitochondrial myopathies were described in the early 1960s, when systematic ultra-structural and histochemical studies revealed excessive proliferation of normal- or abnormal-looking mitochondria in muscle of patients with weakness or exercise intolerance [7, 8]. Because, with the modified Gomori trichrome stain, the areas of mitochondrial accumulation appeared crimson (Fig. 10.1), the abnormal fibers were dubbed “ragged-red fibers” (RRF) [9] and came to be considered the pathological hallmark of mitochondrial disease. However, it soon became apparent that in many patients with RRF, the myopathy is associated with symptoms and signs of brain involvement, and the term mitochondrial encephalomyopathies was introduced [10]. It also became clear that lack of RRF in the biopsy does not exclude a mitochondrial etiology, as exemplified by Leigh syndrome (LS), an encephalopathy of infancy or childhood invariably due to mitochondrial dysfunction but rarely accompanied by RRF.

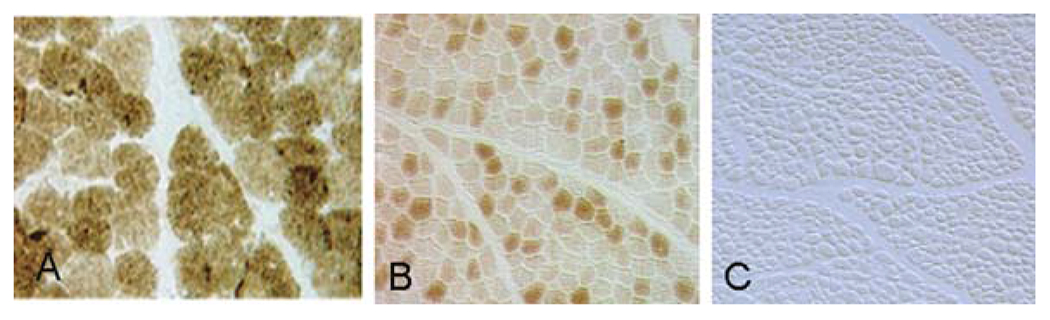

Fig. 10.1.

Serial cross-sections of the muscle biopsy from a patient with KSS and a large-scale mtDNA deletion. A. With the modified Gomori trichrome, ragged-red fibers (RRF) show irregular crimsom staining; B. With the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) stain, the same fibers appear dark blue (“ragged-blue” fibers); C. With the cytochrome c oxidase (COX) stain, most RRF lack COX activity either completely or partially; D. By superimposing the SDH and COX stains, normal fibers appear brown, while COX-deficient fibers stand out as blue (Courtesy of Drs. Eduardo Bonilla and Kurenai Tanji, Columbia University Medical Center)

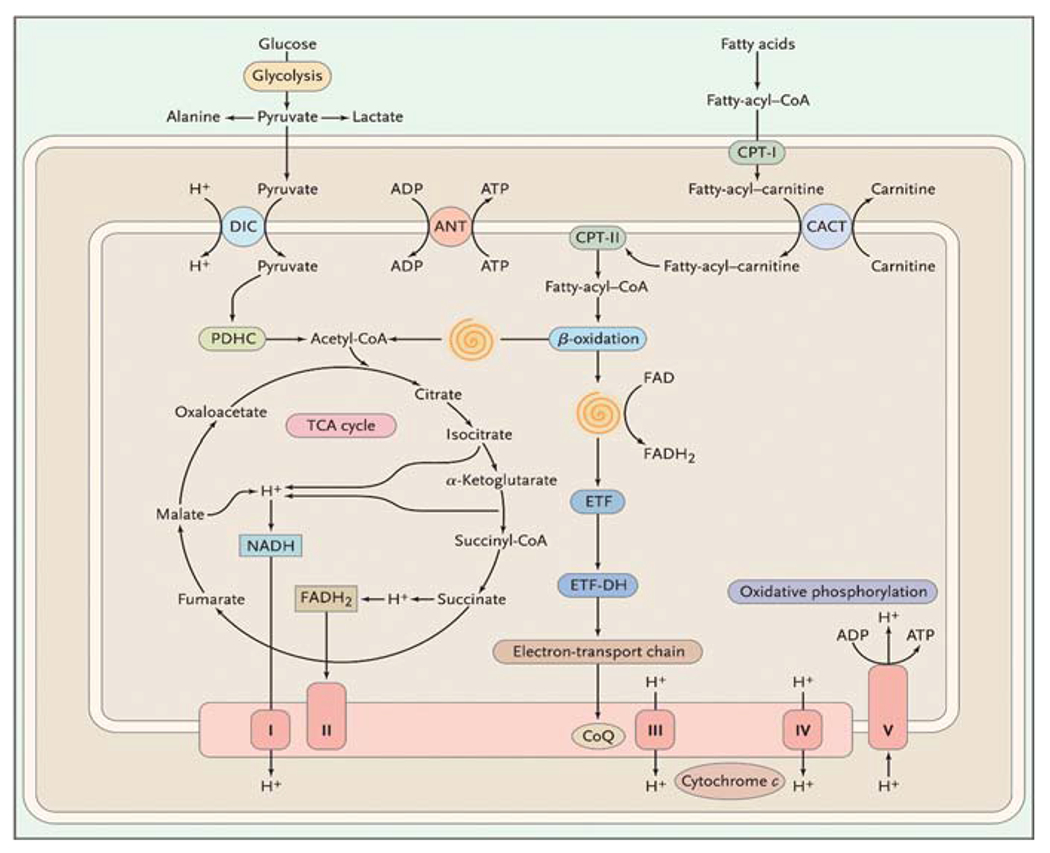

According to the widely accepted “endosymbiotic hypothesis”, mitochondria are the relics of protobacteria that populated anaerobic nucleated cells and endowed them with the precious gift of oxidative metabolism. Thus, mitochondria are the main source of energy for all human tissues and contain many metabolic pathways, only some of which (e.g. pyruvate dehydrogenase complex [PDHC], the carnitine cycle, the ß-oxidation “spirals”, and the Krebs cycle [also known as tricarboxylic acid cycle, TCA] are shown in Fig. 10.2.

Fig. 10.2.

Scheme of the mitochondrion showing selected metabolic pathways. The spirals depict the reactions of the β-oxidation pathway, resulting in the liberation of acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and the reduction of flavoprotein. See the list of abbreviations at the end of the text

Although defects in all of these pathways are by definition mitochondrial diseases, the term “mitochondrial encephalomyopathy” has come to indicate disorders due to defects in the respiratory chain (RC). This is the “business end” of oxidative metabolism, where ATP is generated. Reducing equivalents produced in the Krebs cycle and in the ß-oxidation spirals are passed along a series of protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane (the electron transport chain). The electron transport chain consists of four multimeric complexes (I to IV) plus two small electron carriers, coenzyme Q (or ubiquinone) and cytochrome c. The energy generated by these reactions is used to pump protons from the mitochondrial matrix into the space between the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes. This creates an electrochemical proton gradient, which is utilized by complex V (or ATP synthase) to produce ATP in a process known as oxidation/phosphorylation coupling.

A unique feature of the RC is its dual genetic control: mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes 13 of the approximately 80 proteins that compose the RC and nuclear DNA (nDNA) encodes all the others. As indicated by the different shadings in Fig. 10.2, complex II, coenzyme Q, and cytochrome c are exclusively encoded by nDNA. In contrast, complexes I, III, IV, and V contain some subunits encoded by mtDNA: seven for complex I (ND1, ND2, ND3, ND4, ND4L, ND5, and ND6), one for complex III (cytochrome b), three for complex IV (COX I, COX II, and COX III), and two for complex V (ATPase 6 and ATPase 8).

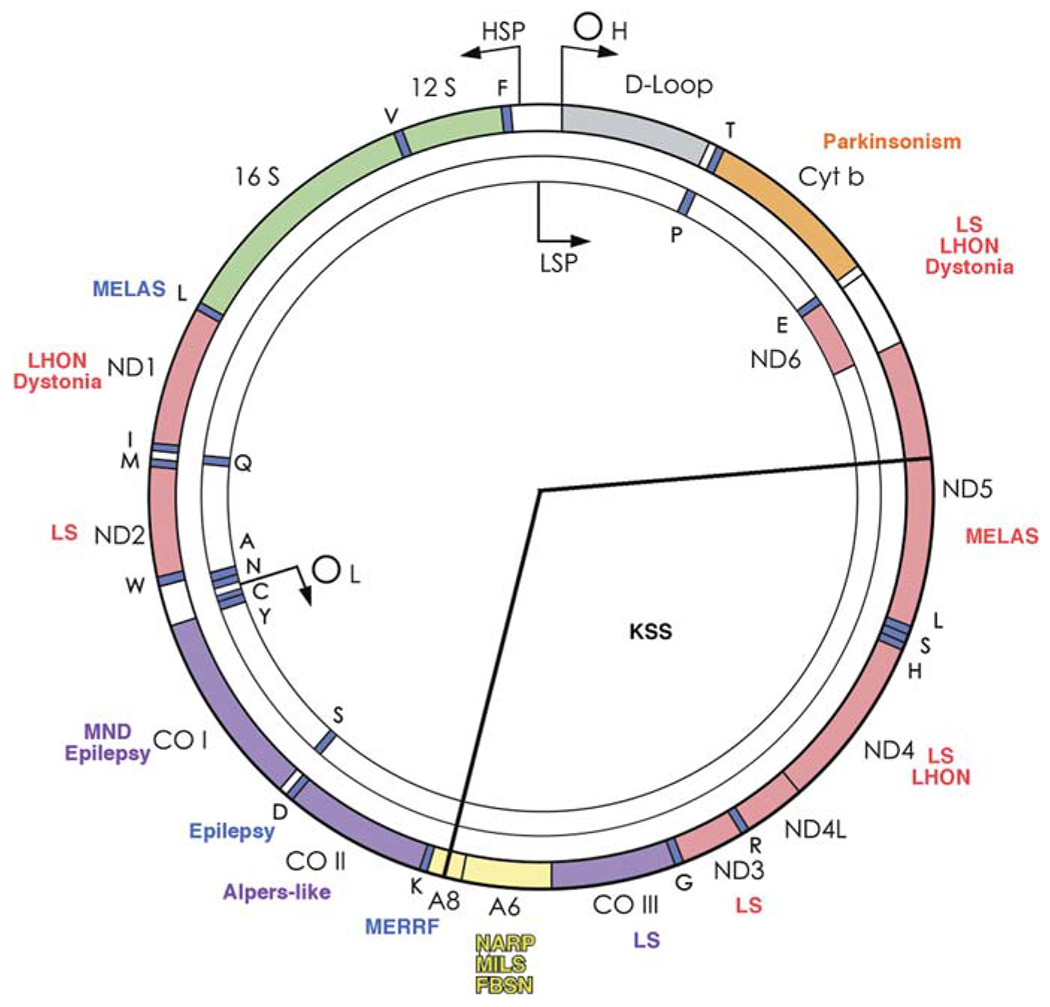

Human mtDNA (Fig. 10.3) is a 16,569-kb circular, double-stranded molecule, which contains 37 genes: 2 rRNA genes, 22 tRNA genes, and 13 structural genes encoding the respiratory chain subunits listed above. In the course of evolution, mtDNA has lost much of its original autonomy and now depends heavily on the nuclear genome for the production of factors needed for mtDNA transcription, translation, and replication. Since 1988, the circle of mtDNA has become crowded with pathogenic mutations, and the principles of mitochondrial genetics should, therefore, be familiar to the practicing physician.

-

(i)

Heteroplasmy and threshold effect. Each cell contains hundreds or thousands of mtDNA copies, which, at cell division, distribute randomly among daughter cells. In normal tissues, all mtDNA molecules are identical (homoplasmy). Deleterious mutations of mtDNA usually (but not always) affect some but not all mtDNAs and the clinical expression of a pathogenic mtDNA mutation is largely determined by the relative proportion of normal and mutant genomes in different tissues. A minimum critical number of mutant mtDNAs is required to cause mitochondrial dysfunction in a particular organ or tissue and mitochondrial disease in an individual (threshold effect).

-

(ii)

Mitotic segregation. At cell division, the proportion of mutant mtDNAs in daughter cells may shift and the phenotype may change accordingly. This phenomenon, called mitotic segregation, explains how the clinical phenotype may change in certain patients with mtDNA-related disorders as they grow older.

-

(iii)

Maternal inheritance. At fertilization, all mtDNA derives from the oöcyte. Therefore, the mode of transmission of mtDNA and of mtDNA point mutations (single deletions of mtDNA are usually sporadic events) differs from Mendelian inheritance. A mother carrying a mtDNA point mutation will pass it on to all her children (boys and girls), but only her daughters will transmit it to their progeny. The best way for a clinician to chart his course toward a diagnosis in the morass of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies is to use a classification that combines clinical features, muscle histochemistry and biochemistry, and genetics. From the genetic point of view, there are two major categories, disorders due to defects of mtDNA and disorders due to defects of nDNA (Table 10.1).

Fig. 10.3.

Schematic view of human mtDNA, showing the gene products for the 12S and 16S ribosomal RNAs, the subunits of NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase (ND), cytochrome c oxidase (COX), cytochrome b (cyt b), and ATP synthase (A), and 22 tRNAs (1-letter amino acid nomenclature), the origins of heavy- and light-strand replication (OH and OL) and the promoters of heavy- and Light-strand transcription (HSP and LSP). Some pathogenic mutations are indicated. The arc removed by the “common deletion” is subtended by the two radii. For abbreviations and acronyms, see the list at the end of the text. (Reproduced from the Annual Review of Neuroscience [39] with permission)

Table 10.1.

Genetic classification of the mitochondrial diseases (RC defects)

| Mutations in mtDNA | Mutations in nDNA |

|---|---|

| Defects of mitochondrial protein synthesis | Mutations in RC subunits |

| mtDNA large-scale deletions | Mutations in RC assembly proteins |

| mutations in tRNA or rRNA genes | Defects of mtDNA maintenance, replication, translation |

| Mutations in protein-coding genes | Defects in protein importation Defects of membrane lipid composition Defects of mitochondrial dynamics |

1. Disorders due to defects of mtDNA.

These include rearrangements (single deletions or duplications) and point mutations.

-

A.

mtDNA rearrangements. Single deletions of mtDNA have been associated with three sporadic conditions: (i) Pearson syndrome, a usually fatal disorder of infancy characterized by sideroblastic anemia and exocrine pancreas dysfunction. (ii) Kearns-Sayre syndrome (KSS), a multisystem disorder with onset before age 20 of impaired eye movements (progressive external ophthalmoplegia, PEO), pigmentary retinopathy, and heart block. Frequent additional signs include ataxia, dementia, and endocrinopathies (diabetes mellitus, short stature, hypoparathyroidism). Lactic acidosis, elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein (over 100 mg/dl), and scattered COX-negative RRF in the muscle biopsy are typical laboratory abnormalities. (iii) PEO with or without proximal limb weakness, often compatible with a normal lifespan. Deletions vary in size and location, but a “common” deletion of 5 kb is frequently seen in patients and in aged individuals (Fig. 10.3).

-

B.

Point mutations. Over 200 pathogenic point mutations have been identified in mtDNA from patients with a variety of disorders [11], most of which are maternally inherited and multisystemic, but some are sporadic and tissue-specific (Fig. 10.3). Among the maternally inherited encephalomyopathies, four syndromes are more common. The first is MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes), which typically presents in children or young adults after normal early development. Symptoms include recurrent vomiting, migraine-like headache, and stroke-like episodes causing cortical blindness, hemiparesis, or hemianopia. MRI of the brain shows “infarcts” that do not correspond to the distribution of major vessels, raising the question of whether the strokes are vascular or metabolic in nature [12]. The most common mtDNA mutation is A3243G in the tRNALeu(UUR) gene, but about a dozen other mutations have been associated with MELAS, most notably a mutation (G13513A) in the ND5 gene, which encodes subunit 5 of complex I [13]. It is important to note that most maternal relatives of a typical MELAS patient carry the mutation in low abundance and are either mildly affected or unaffected. In agreement with this observation, two epidemiological studies have reported comparably high prevalence (about 1:750) of the A3243G mutation in the normal population [14, 15], and one of them has found that the prevalence of pathogenic mtDNA mutations is 1:200 individuals in Northern England [15].

The second syndrome is MERRF (myoclonus epilepsy with ragged red fibers), characterized by myoclonus, seizures, mitochondrial myopathy, and cerebellar ataxia. Less common signs include dementia, hearing loss, peripheral neuropathy, and multiple lipomas. Three mtDNA mutations have been associated with MERRF and all are in the tRNALys gene (A8344G; T8356C; G8363A).

The third syndrome comes in two flavors: (i) NARP (neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa) usually affects young adults and causes retinitis pigmentosa, dementia, seizures, ataxia, proximal weakness, and sensory neuropathy; (ii) maternally inherited Leigh syndrome (MILS) is a severe infantile encephalopathy with characteristic symmetrical lesions in the basal ganglia and the brainstem [16, 17].

The fourth syndrome, LHON (Leber hereditary optic neuropathy) is characterized by acute or subacute loss of vision in young adults, more frequently males, due to bilateral optic atrophy. Three mtDNA point mutations in ND genes account for more than 90% of LHON cases. These are G11778A in ND4, G3460A in ND1, and T14484C in ND6 [18].

Not surprisingly, syndromes associated with mtDNA mutations can affect every system in the body, including the eye (optic atrophy; retinitis pigmentosa; cataracts); hearing (sensorineural deafness); endocrine system (short stature; diabetes mellitus; hypoparathyroidism); heart (familial cardiomyopathies; conduction blocks); gastrointestinal tract (exocrine pancreas dysfunction; intestinal pseudo-obstruction; gastroesophageal reflux); and kidney (renal tubular acidosis) [6]. Any combination of the symptoms and signs listed above should raise the suspicion of a mitochondrial disorder, especially if there is evidence of maternal transmission.

On the other hand, point mutations in mtDNA protein-coding genes often escape the rules of mitochondrial genetics in that they affect single individuals and single tissues, most commonly skeletal muscle. Thus, patients with exercise intolerance, myalgia and, sometimes recurrent myoglobinuria, may have isolated defects of complex I, complex III, or complex IV, due to pathogenic mutations in genes encoding ND subunits, cytochrome b, or COX subunits [19]. The lack of maternal inheritance and the involvement of muscle alone suggest that mutations arose de novo in myogenic stem cells after germ-layer differentiation (“somatic mutations”).

2. Disorders due to defects of nDNA.

These are all transmitted by Mendelian inheritance and include three major subgroups.

-

A.

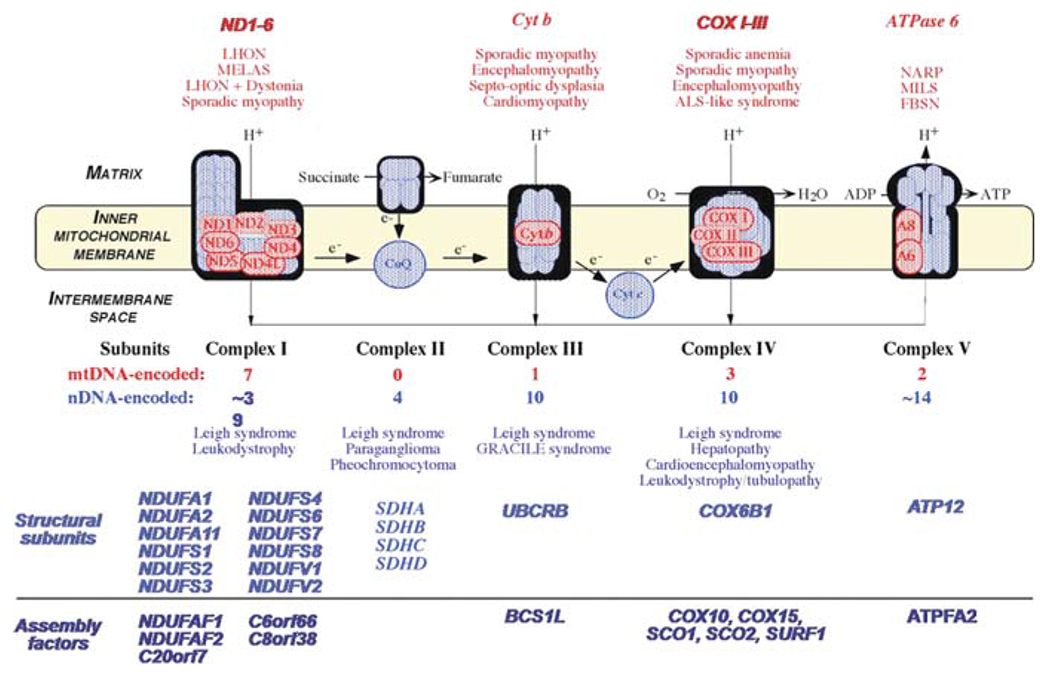

Mutations in genes encoding subunits or ancillary proteins of the respiratory chain. As noted above, mtDNA encodes only 13 subunits of the respiratory chain, while nDNA encodes all subunits of complex II, most subunits of the other four complexes, as well as CoQ10 and cytochrome c. Nuclear DNA mutations can affect respiratory chain complexes directly or indirectly (Fig. 10.4).

Direct “hits”, that is, mutations in gene encoding respiratory chain subunits, were known until recently only for complex I and complex II, but the first mutation in a subunit of complex IV, COX VIB1, has now been reported [20]. These have been associated with autosomal recessive forms of LS. Primary or secondary coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency can cause five major syndromes: (i) a predominantly myopathic disorder with recurrent myoglobinuria but also CNS involvement (seizures, ataxia, mental retardation) [21, 22, 23]; (ii) a predominantly encephalopathic disorder with ataxia and cerebellar atrophy [24, 25, 26]; (iii) an isolated myopathy, with RRF and lipid storage [27]; (iv) a generalized mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, usually with onset in infancy [28, 29, 30]; and (v) nephropathy alone or associated with encephalopathy [31]. Examples of secondary CoQ10 deficiency include ataxia oculomotor apraxia (AOA1) associated with mutations in the aprataxin (APTX) gene [32], and the myopathic presentation of glutaric aciduria type II (GA II) due to mutations in the electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase (EFTDH) gene [33]. Examples of primary CoQ10 deficiency include mutations in the biosynthetic genes, COQ1 (PDSS1 and PDSS2) [34, 35], COQ2 [36], and CABC1/ADCK3 [37, 38]. Irrespective of etiology, diagnosis is important because most patients with CoQ10 deficiency respond to high-dose CoQ10 supplementation.

Indirect “hits” are mutations in genes encoding proteins that are not components of the respiratory chain, but are needed for the proper assembly and function of respiratory chain complexes (Fig. 10.4). This “murder by proxy” mechanism has been identified in disorders due to defects in complexes I, III, IV, and V (for review, see [39], and is best illustrated by Mendelian defects of complex IV (COX). Mutations in genes encoding six ancillary proteins (SURF1, SCO2, SCO1, COX10, COX15, and LRPPRC) have been associated with COX-deficient LS or other multisystemic fatal infantile disorders in which encephalopathy is accompanied by cardiomyopathy (SCO2; COX15), nephropathy (COX10), or hepatopathy (SCO1).

This is a burgeoning field of research with important theoretical and practical implications. From an investigative point of view, these disorders are teaching us a lot about the structural and functional complexity of the respiratory chain. At a more practical level, identification of mutations in these genes allows prenatal diagnosis and suggests approaches to therapy.

-

B.

Defects of intergenomic signaling. As noted above, the mtDNA is highly dependent for its proper function and replication on numerous factors encoded by nuclear genes. Mutations in these genes cause Mendelian disorders characterized by qualitative or quantitative alterations of mtDNA. Examples of qualitative alterations include autosomal dominant or recessive multiple deletions of mtDNA, usually accompanied clinically by progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) plus a variety of other symptoms and signs. Four of these conditions have been characterized at the molecular level. Mutations in the gene (TYMP) for thymidine phosphorylase (TP) are responsible for an autosomal recessive multisystemic syndrome called MNGIE (mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy) [40, 41]. Mutations in the gene for one isoform of the adenine nucletide translocator (ANT1) have been identified in patients with autosomal dominant PEO [42]. Mutations in the PEO1 gene, encoding Twinkle, a helicase, are also associated with autosomal dominant PEO [43], whereas mutations in the gene encoding polymerase [isp]γ (POLG) may cause either autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive PEO [44] as well as a variety of symptoms and signs, including ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, parkinsonism, and MNGIE or MERRF-like syndromes [45]. Mutations in the gene (POLG2) encoding the accessory subunit of POLG, can also cause autosomal dominant PEO and multiple deletions [46]. Finally, mutations in OPA1, which encodes a protein involved in mitochondrial dynamics (see below), besides causing dominant optic atrophy (DOA) can also result in a syndrome that includes optic neuropathy, PEO, deafness, ataxia, and axonal neuropathy associated with multiple mtDNA deletions in the muscle biopsy [47, 48, 49, 50].

Examples of quantitative alterations of mtDNA include severe or partial mtDNA depletion, usually characterized clinically by congenital or childhood forms of autosomal recessively inherited myopathy or hepatopathy [51]. Mutations in eight genes, seven of them involved in mitochondrial nucleotide homeostasis, have been associated with mtDNA depletion syndromes, although they still do not explain all cases. Mutations in the gene encoding thymidine kinase 2 (TK2) are typically seen in patients with myopathic mtDNA depletion syndromes [52], whereas mutations in the genes encoding the β subunit (SUCLA2) or the α subunit (SUCLG1) of the mitochondrial matrix enzyme succinyl-CoA synthetase, (SCS-A) cause both myopathy and encephalopathy [53, 54]. Mutations in DGUOK, encoding deoxyguanosine kinase, predominate in patients with hepatic or hepatocerebral mtDNA depletion syndromes [55, 56], but mutations in POLG are the major causes of Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome, a severe hepatocerebral syndrome with vulnerability to valproic acid [45, 57]. Mutations in a gene (MPV17) not involved in nucleotide pool homeostasis, have been associated with hepatocerebral syndrome [58] and with the Navajo neurohepatopathy (NNH) syndrome, prevalent in the Navajo population of Southwestern Unites States [59]. An iatrogenic form of mtDNA depletion may follow treatment with nucleoside analogs, such as zidovudine (AZT).

A group of defects of intergenomic communication is due to mutations in genes encoding factors necessary for the faithful translation of mtDNA-encoded proteins [60], including EFG1 (encoding elongation factor 1) [61], MRPS16 (encoding small subunit protein) [62], EFTu (encoding elongation factor Tu), TSFM (controlling the expression of both EFTs and EFTu) [63], PUS1 (encoding pseudouridine synthase 1) [64, 65]. The resulting disorders usually affect infants and cause severe encephalomyopathy, cardiomyopathy, or sideroblastic anemia. Typically, both quality and quantity of mtDNA are normal in these patients, but there are – not surprisingly – multiple respiratory chain defects involving all complexes containing mtDNA-encoded subunits. Mutations in DARS2 (encoding mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase) causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation (LBSL) [66]: surprisingly, no defects of respiratory chain enzymes were found in patients with LBSL, at least in fibroblasts and lymphoblasts.

-

C.

Defects of mitochondrial motility, fusion, and fission. Defects of mitochondrial dynamics are taking center stage as causes of neurodegenerative disorders [39, 67] and do belong to the mitochondrial diseases “sensu stricto” because impairment of oxidative phosphorylation has been documented in at least one form [47]. Mitochondria travel on microtubular rails, propelled by motor proteins, usually GTPases, called kinesins or dyneins. The first defect of mitochondrial motility was identified in a family with autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia and mutations in a gene (KIF5A) encoding one of the kinesins [68]. Interestingly, the mutation affects a region of the protein involved in microtubule binding.

Mutations in OPA1 cause autosomal dominant optic atrophy, the Mendelian counterpart of LHON [69, 70]. Mutations in MFN2, encoding mitofusin 2, cause an autosomal dominant axonal variant of Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease [71, 72]. Also, mutations in GDAP1, the gene encoding ganglioside-induced differentiation protein 1, which is located in the mitochondrial outer membrane and regulates the mitochondrial network, cause CMT type 4A, an autosomal recessive, severe, early-onset form of either demyelinating or axonal neuropathy [73, 74].

-

D.

Indirect causes of respiratory chain dysfunction. We include here mutations in nuclear genes that affect neither respiratory chain subunits or ancillary proteins, nor mtDNA structure or copy number. For example, the function of the respiratory chain can be impaired by alterations in the lipid composition of the inner mitochondrial membrane or by defective importation of one or more subunits. The first situation is exemplified by Barth syndrome, an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by mitochondrial myopathy, cardiopathy, and leukopenia [75]. The gene responsible for this disorder (TAZ) [76] encodes a family of proteins (“tafazzins”) involved in the synthesis of phospholipids, and biochemical analysis has shown altered amounts and composition of cardiolipin, the main phospholipid component of the inner mitochondrial membrane [77].

An example of defective protein importation is the X-linked deafness-dystonia syndrome (Mohr-Tranebjaerg syndrome), characterized by progressive sensorineural deafness, dystonia, cortical blindness, and psychiatric symptoms. This disorder is due to mutations in TIMM8A, which encodes the deafness-dystonia protein (DDP1) [78], a component of the mitochondrial protein import machinery located in the intermembrane space.

Fig. 10.4.

The mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC), showing nDNA-encoded subunits in blue and mtDNA-encoded subunits in red. Coenzyme Q and cytochrome c are electron (e−) carriers. Diseases are listed according to the affected RC complex and divided in defects of RC subunits and defects of assembly proteins

10.2. Pathogenic Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Diseases

From the standard textbook gloss that mitochondria are the “powerhouses” of the cell, most people would reasonably deduce that mitochondrial diseases are energy failures, blackouts or brownouts affecting various tissues. Although defective ATP production undoubtedly has an important pathogenic role, mitochondria perform multiple additional functions that are important for cell life and death, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the control of calcium homeostasis, and the regulation of programmed cell death (apoptosis). It is likely that the pathogenesis of any mitochondrial disease will involve, at least to some extent, all these functions. An elegant verification of this concept was offered by studying the consequences of mutations in OPA1, which – as we have seen above – encodes a dynamin-related GTPase important for mitochondrial fusion. Besides exhibiting the predictable alteration of the mitochondrial network, mutant skin fibroblasts grown in galactose medium and forced to use oxidative metabolism also showed impaired ATP synthesis at the level of complex I and activation of apoptosis [47]. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments documented a direct interaction of OPA1 with subunits of the respiratory chain and with the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF). Direct evidence that alteration of mitochondrial dynamics can cause loss of mtDNA, impaired RC function, and increased ROS production was provided by experiments in which HeLa cells were depleted of DrP1, another dynamin-related GTPase like OPA1 [79]. Similar multiple interactions of pathogenic mechanisms have been shown in neurodegenerative disorders due to mutant mitochondrial proteins, such as Friedreich ataxia (FA), Parkinson disease (PD), Alzheimer disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) [39].

If we now focus on the “primary” mitochondrial diseases outlined above, i.e. defects of the RC, two pathogenic mechanisms are most commonly considered, impaired ATP synthesis and excessive ROS production. Due to the lack of animal models for mtDNA-related disorders, the biochemical and functional consequences of mtDNA mutations have been gleaned from studies of cybrid cell lines, that is, immortalized human cells that have been “emptied” of their mtDNA and repopulated with mutant mtDNA from patients [80]. In particular, cybrid cell lines harboring varying mutant loads have been used to identify the threshold of pathogenicity for various mtDNA mutations. For all major mutations, the thresholds assessed in vitro appeared to be both high and steep: for the A3243G MELAS mutation, as one example, the threshold was around 90% [81]. However, these data cannot be extrapolated to the in vivo situation, as shown by oligosymptomatic carriers of the A3243G mutation, who had abnormal 31P-MRS studies of muscle [82] and abnormal lactate peaks in both cerebrospinal fluid and brain parenchyma by 1H-MRS [83].

Let us consider separately each of the several factors that may contribute to the clinical expression of mutations (of mtDNA or nDNA) affecting the respiratory chain.

-

(i)

Heteroplasmy and mutation load. Obviously, this applies only to mtDNA-related diseases. It is intuitive that the severity of clinical manifestations should show some correlation to the mutation load, a concept that has been adopted as one of the canonical criteria of pathogenicity for novel mtDNA mutations. This is best exemplified by the T8993G mutation, as noted by Tatuch et al. back in 1992 [84]: when the mutation load is high (about 90%), the disease manifests in infants or children as LS (maternally inherited LS, MILS); when the mutation load is lesser (about 70%), it causes a later-onset and milder encephalomyopathy (NARP). Accordingly, ATP synthesis was inversely correlated to the mutation load in platelet-derived submitochondrial particles [85] and in lymphocytes [86] harboring the T8993G mutation.

Different loads of the same mutation in different tissues may also explain, to a certain extent, differential tissue involvement. This may be especially true for a heterogeneous and highly specialized tissue like the brain. In an attempt to explain the distinctive neurological symptoms of patients with KSS, MERRF, and MELAS, the mutation typical of each disease has been “mapped” indirectly through immunohistochemical techniques. Consistent with clinical symptomatology and laboratory data, immunocytochemical evidence suggested that the single mtDNA deletions of KSS abound in the choroids plexus [87], the A3243G-MELAS mutation is abundant in the walls of cerebral arterioles [88], and the 8344G-MERRF mutation is abundant in the olivary nuclei of the cerebellum [89]. However, these data fail to explain what directs each mutation to a particular area of the brain.

Even if the high pathogenic threshold established by studies of cybrid cell lines does not correlate strictly with the in vivo threshold, it is nonetheless true that most mtDNA mutations have high and steep thresholds. The recent finding that the prevalence of pathogenic mtDNA mutations (at relatively low mutation loads) in the normal population is as high as 1:200 [15] bolsters this concept.

There is, thus far, one notable exception, a de novo mutation in tRNATrp (C5545T), which caused a childhood mitochondrial encephalomyopathy at unusually low heteroplasmic levels (<25%) in affected tissues and whose pathogenic threshold in cybrids was as low as 4–8% [90]. This new concept of dominance in mitochondrial genetics, together with the unexpectedly high prevalence of mtDNA mutations in the general population, pose new diagnostic challenges, because low-level mutations may escape detection.

-

(ii)

Type of mutation. Obviously, some mutations in the same gene can be more severely pathogenic than others and this applies to both mtDNA and nDNA changes. The best example of this concept is offered by two pairs of mutations in the ATPase 6 gene of mtDNA, which are not only in the same gene but also each at the very same site, T8993G/T8993C and T9176G/T9176C and each resulting in the same amino acid change, either Leu>Arg or Leu>Pro [91]. While T8993G and T7917G cause NARP/MILS at different mutant loads [16, 92, 93], T8993C and T7917C cause a generally (but not invariably) milder clinical syndrome [94]. Accordingly, ATP synthesis is much more severely impaired by the T8993G than by the T8993C mutation in primary fibroblasts [95], lymphocytes [96, 97], and cybrid cell lines [98]. Why should the Leu>Arg mutation interfere with the rotary engine’s function of ATP synthase more severely than the Arg>Pro mutation is not completely clear, but assembly seems to be normal with both mutations [99, 100, 101] and it was postulated that the problem was either reduced proton travel through the A6 channel or reduced efficiency of the rotary coupling between subunit A6 (part of the stator) and subunit c (part of the rotor), or both [91]. Recent work suggests that the coupling of proton flux and ATP synthesis is slowed by the T-to-C mutations and virtually abolished by the T-to-G mutations [96].

The tRNALeu(UUR) is a very hot spot, with over 20 mutations listed as pathogenic. It has been suggested that the site of the mutation in the cloverleaf structure of the gene may influence the phenotype, in that mutations causing the typical MELAS syndrome lack the normal taurine-containing modification (5-taurinomethyluridine) at the anticodon wobble position whereas mutations associated with other syndromes have normal 5-taurinomethyluridine modifications [102].

-

(iii)

Why tissue specificity? It has been observed that some tRNA genes of mtDNA tend to affect certain tissues more than others: for example, mutations in tRNAIle are often associated with cardiomyopathy and mutations in tRNALys are selectively, though not invariably, associated with multiple lipomas. More in general, it has been proposed that mutations in certain sites of the tRNA cloverleaf structure may play a role in determining the tissue specificity of the phenotype [103]. Interesting as they are, as of now these are mere associations in search of explanations.

In mtDNA-related disorders, real or apparent tissue-specificity can occur in two situations, best exemplified by mitochondrial myopathies. There are numerous examples of mutations in tRNA or protein-coding genes arising de novo and affecting selectively the progenitor cells of skeletal muscle [19]: these often create diagnostic conundrums because they contradict at least two “rules” of mitochondrial genetics, maternal inheritance and multisystem distribution. An example of what could be called “pseudo tissue specificity” is extreme skewed heteroplasmy of a generalized mutation: as the pathogenic threshold is surpassed only in skeletal muscle, the resulting phenotype will be a pure myopathy [104].

A more puzzling example of tissue specificity is offered by homoplasmic mtDNA mutations, such as most LHON-associated mutations in ND genes [18]: obviously, there is a special vulnerability of the retinal ganglion cells to the consequences of these mutations (be it ATP deprivation, ROS excess, or both – see below), probably exacerbated by the extraordinary dependence of these cells on oxidative metabolism, but – again – we are making associations rather than offering explanations. Similarly, a homoplasmic mutation in tRNAIle [105] causes a selective cardiomyopathy whereas a homoplasmic mutation in tRNAGlu causes a selective myopathy [106], which can only be explained by the coexistence of modifier nuclear genes. Clearly, the cross-talk between the two genomes goes beyond the classical defects of intergenomic signaling and remains to be fully elucidated. It also goes beyond tissue specificity to affect, for example, gender vulnerability: the predominance of affected males in LHON has been attributed to two loci in the X-chromosome [107, 108].

Among the nDNA-related diseases, the most reasonable explanation for tissue specificity would be mutations in tissue-specific isoforms of RC subunits or assembly factors. While no clinical entity is referable to such mechanism as yet, selective tissue vulnerability is seen in many Mendelian mitochondrial diseases. This is best exemplified by the several mutations in COX-assembly proteins: while all affect the brain, usually resulting in LS-like symmetrical lesions, they affect other tissues differently. Thus, mutations in SCO2 and COX15 cause cardiomyopathy [109] whereas mutations in SCO1 cause liver disease [110]. This is probably due to different levels of residual COX activity, as illustrated by COX histochemistry in skeletal muscle from children with SCO2 or SURF1 mutations (Fig. 10.5). Yet another example is offered by a Mendelian defect of intergenomic communication. Although the expression of mutations in the mitochondrial translation factor EFG1 is ubiquitous, the clinical presentation is a devastating hepatopathy. Accordingly, liver had the lowest residual assembly of various RC complexes whereas cardiac tissue had the highest, with other tissues falling in between [61]. The varying residual activities of RC complexes in different tissues – an the severity of their clinical involvement – was apparently dictated by the ratio of EFTu:EFTs translation elongation factors [61].

-

IV.

Pathogenic importance of mtDNA haplotypes. In their migration out of Africa, human beings have accumulated distinctive variations from the mtDNA of our ancestral “mitochondrial Eve”, resulting in several haplotypes characteristic of different ethnic groups [111]. It has been suggested that different mtDNA haplogroups or subhaplogroups may modulate oxidative phosphorylation, thus influencing the overall physiology of individuals and predisposing them to – or protecting them from – certain diseases [111].

The best example of the pathogenic importance of the mitochondrial genetic background comes from studies of LHON, a monogenic mtDNA disorder notorious for its incomplete penetrance. Careful mtDNA haplogroup subtyping of 159 LHON families has established that the risk of visual loss is greater when patients harboring the A11778G mutation belong to haplogroup J2, patients harboring the T14484C belong to haplogroup J1, or patients with the G3460G mutation belong to haplogroup K [112]. Substitutions in the cyt b gene characteristic of these haplogroups may explain the increased penetrance through their influence on the supercomplex formation between complexes I and complex III.

-

V.

Defective ATP synthesis and excessive ROS production. In mtDNA-related disorders, impaired ATP synthesis has been documented in vivo by 32P NMR spectroscopy of skeletal muscle or brain in patients with LHON [113, 114], encephalomyopathy [115, 116] or myopathy [117].

Defective ATP synthesis has also been documented in easily accessible tissues, such as primary fibroblasts [95, 118], lymphocytes [86, 96, 97], platelets [85, 119, 120], or cybrid cell lines [98, 119]. The relative role of impaired ATP synthesis and excessive ROS production has been well documented in cybrid cell lines harboring the three mtDNA mutations associated with LHON. In a series of elegant studies, Carelli and collaborators have clearly shown that complex I is defective and ATP production is impaired, although these effects may require exposure to a medium containing galactose instead of glucose, thus “forcing” the cells to use oxidative metabolism [119, 121, 122]. They have shown that LHON mutations affect the ubiquinone (CoQ) binding site of complex I, leading to overproduction of unstable ubisequinones and attending ROS damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids [123]. The crucial role of the balance between ATP shortage and ROS excess was also documented by the same group in a study of lymphocytes from patients with NARP/MILS: interestingly, they showed that ATP shortage prevailed in the “severe” T8993G mutation whereas the “mild” T8993C mutation favored ROS overproduction [97]. Excessive ROS production was also the only biochemical alteration encountered in cybrid cell lines harboring a mutation (T9957C) in the mtDNA gene encoding COX III [119].

The relative contribution of ATP shortage and ROS excess to pathogenesis and clinical expression is also evident in Mendelian mitochondrial diseases. This is borne out by studies of complex I deficiency and primary CoQ10 deficiency. In agreement with the concept that complex I and complex III are the major producers of ROS [124], complex I deficiency causes severe oxidative stress. This was discussed above for the ND mutations of LHON, but is even more evident in children with mutations in nDNA-coded subunits or assembly factors of complex I [125]. Not too surprisingly, there was an inverse relationship between amount and residual activity of complex I and ROS overproduction, although, contrary to a similar report published before the molecular era [126], there was no apparent relationship between severity of ROS production and clinical phenotype. In contrast, a correlation between biochemical data and severity of clinical presentation was observed in studies of fibroblasts from two patients with different primary CoQ10 deficiency, one due to mutations in COQ2 and causing a severe but treatable infantile encephalomyopathy [28, 36], the other due to mutations in PDSS2 and causing fatal infantile LS [34]. PDSS2 mutant cells showed severely reduced ATP synthesis but no ROS overproduction or compensatory increase of antioxidant defense markers, whereas COQ2 mutant cells showed only a partial defect of ATP synthesis but marked increased of ROS with attending oxidation of lipids and proteins.

Although it may be too soon for generalizations, which are risky anyway, data from both mtDNA and nDNA mutants suggest that severe blocks of the RC result in energy blackouts and mild oxidative stress, while partial blocks result in energy brownouts but severe oxidative stress.

-

VI.

Altered Ca2+ handling. Mitochondria have a central role in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and are, in turn, very sensitive to Ca2+ signals, which may trigger necrosis or apoptosis [127]. Different alterations of Ca2+ signaling have been reported in different mtDNA-related disorders. In cybrid cells harboring the T8356C MERRF mutation, the transient mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and ATP production in response to physiological agonists were decreased, whereas both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial Ca2+ handling were normal in cells harboring the T8993G NARP/MILS mutation [128]. In contrast, fibroblasts harboring the A3243G MELAS mutation were unable to effectively buffer intracellular Ca2+, which resulted in a cytotoxic Ca2+ effect [129]. Although the alterations of Ca2+ homeostasis appear to differ in different disorders and remain to be better defined, they certainly play crucial pathogenic roles, considering the importance of Ca2+ in the control of ATP synthesis, mitochondrial dynamics, and apoptosis [130, 131].

Fig. 10.5.

Cross-sections of human muscle stained for COX. A, normal; B. patient with LS due to mutations in SURF1; C. patient with encephalocardiomyopathy due to mutations in SCO2

10.3. Therapeutic Strategies

There are three strategies to be considered in treating mitochondrial diseases or, for that matter, any other group of diseases. The first strategy aims at modifying the consequences, i.e. the symptoms, of these disorders: this is palliative or “band-aid” (loosely translated from the Latin “pallium”, cloak) therapy. The second strategy is both more ambitious and more difficult because it aims at attacking the causes of these disorders and is therefore based either on gene therapy or on enzyme replacement therapy. The third therapeutic approach falls between the other two and it aims at interrupting or modifying the pathogenic mechanisms, thus interrupting or, more likely, slowing the course of diseases.

-

I.

Symptomatic therapy. The fact that mtDNA-related disorders can affect every tissue in the body requires the application of symptomatic therapy already used in different subspecialties of medicine[6, 132].

Neurology.

Seizures are treated with conventional anticonvulsants, except that valproic acid should be avoided in children with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome and POLG mutations because it often triggers acute hepatic failure. Corticosteroids are helpful in the acute phase of strokes due to MELAS mutations and physical, occupational, respiratory, and speech therapy accelerates recovery from strokes and aids patients with other CNS problems [133]. Psychotropic drugs may be needed in patients with predominant or exclusive psychiatric symptoms [134]. Exercise intolerance is a most common complaint, which may lead to inactivity, deconditioning, and further deterioration of muscle function. Aerobic exercise under proper supervision has proven helpful in staving off this downhill course [135]. Patients with recurrent rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria should be hydrated and undergo renal dialysis in cases of renal failure. If the recurrent myoglobinuria is associated with muscle CoQ10 deficiency, most patients will benefit from oral CoQ10 supplementation.

Ophthalmology.

Ptosis, often with PEO, is very common and debilitating both functionally and psychologically. Frontalis suspension is the preferred form of surgery because it protects from corneal exposure [136]. LHON is resistant to therapy, but a few patients appear to have responded to treatment with idebenone [18].

ENT.

Neurosensory hearing loss is a common consequence of mtDNA-related disorders and, when severe, can be effectively treated in most patients with cochlear implants [137]. Chronic respiratory failure can initially be treated with noninvasive continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive air pressure (Bi-PAP) but may eventually require tracheotomy [136].

Endocrinology.

Diabetes mellitus should be treated by conventional means, including diet, sulfonylureas, and insulin, but metformin ought to be avoided because it has been associated with lactic acidosis. Patients with hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, or hypoparathyroidism should receive specific hormone replacement. Treatment of short stature with growth hormone is controversial, unless there is clear evidence of growth hormone deficiency.

Cardiology.

In KSS, conduction blocks dominate the cardiological picture and timely placement of a pacemaker can be lifesaving. In mitochondrial disorders dominated by cardiomyopathy, cardiac transplantation is an option that should not be discarded a priori [138].

Gastroenterology.

Feeding difficulties in infants and children can be alleviated by drugs or by surgical intervention, including percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or fundoplication. Severe gastrointestinal dysmotility may necessitate parenteral nutrition in patients with MNGIE. Children with predominant or isolated liver failure, usually due to a mtDNA depletion syndrome, may benefit from liver transplantation, although this is still controversial [139].

Hematology.

Infants with Pearson syndrome – dominated by sideroblastic anemia and due to single mtDNA deletions – may respond to repeated blood transfusion, although survivors often develop KSS later in life.

Nephrology.

Renal tubular acidosis and Fanconi syndrome require readjustment of the electrolytic balance [140]. Primary CoQ10 deficiency is often associated with – or dominated by – nephropathy [31] and early CoQ10 supplementation may improve glomerular function and prevent neurological complications.

-

II.

Radical therapy. The term implies tackling the root of the disease, i.e. its etiology. Ultimately, this implies replacing the mutant DNA with wild-type DNA. Gene therapy for mitochondrial diseases due to mutations in nDNA faces the same hurdles of gene therapy for other Mendelian disorders, including choice of optimal viral or non-viral vectors, effective delivery to the affected tissues, and avoidance of immunological rejection. For mtDNA-related diseases the formidable – and still unsolved – problem is that no investigator has been able to transfect DNA into mitochondria in a heritable manner.

A radical way of, if not correcting, at least avoiding the cause of a disease includes genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis. As detailed in the first section of this review, the rapid progress in our knowledge of the molecular defects underlying Mendelian mitochondrial disorders has offered families, especially young families with fatal infantile conditions, the option of prenatal diagnosis. Unfortunately, prenatal diagnosis of most mtDNA-related diseases is impeded by two factors: (i) the mutation load in amniocytes of chorionic villi does not necessarily reflect that of other fetal tissues; and (ii) mutation loads measured in prenatal samples may shift due to mitotic segregation. Fortunately, there is good evidence that mutations in ATPase 6 associated with NARP/MILS do not undergo tissue- or age-related variations [141], a situation confirmed by the first pre-implantation diagnosis for a human mitochondrial disease [142].

Another promising way of preventing mtDNA-related disorders is currently ostracized by ethical concerns about the manipulation of germline cells. A woman carrying an mtDNA mutation, such as the common and potentially devastating A3243G MELAS change, could have her fertilized oöcytes cleansed in vitro of the cytoplasm and most mitochondria. The naked pronucleus would then be transferred to a normal enucleated host oöcyte and implanted in the woman’s uterus: the result of this procedure would be a mitochondrially normal child carrying the nuclear traits of both parents. This technology has been successful in transmitochondrial “mitomice” [143] and has been approved for experimentation in the UK.

Another way of going to the root of the problem is stem cell therapy, which, for Mendelian disorders, offers real promise. For example, allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) in a woman with MNGIE has improved her clinical condition and her nerve cell conduction velocities [144]. Biochemically, TP activity reached mutation carrier levels in her blood, where the concentrations of toxic compounds, thymidine and deoxyuridine, returned to normal.

Yet another way of circumventing the genetic defect in Mendelian RC disorders tries to imitate mother nature by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis (and the residual activity of a defective enzyme). Mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated by PPARγ coactivator α (PGC-1α), which, in turn, is activated by bezafibrate, a drug already used in medicine. Interestingly, bezafibrate increased the activities of RC complexes both in normal cultured cells and in cells with RC enzyme defects [145]. Even more interestingly, in a mouse with COX deficiency myopathy due to an engineered mutation in the assembly gene COX10, treatment with bezafibrate increased residual COX activity and ATP production in muscle and delayed both the onset of myopathy and the time of death [146]. Because bezafibrate is already part of our pharmacological armamentarium, it could be tested relatively rapidly in patients with mitochondrial diseases.

Gene therapy for mtDNA-related diseases poses special problems because of polyplasmy and heteroplasmy and because we are still unable to transfect DNA into mitochondria. Of the many indirect strategies proposed, probably the most viable is heteroplasmic shifting, aimed at lowering the mutant mtDNA below the pathogenic threshold. Many different approaches have been tried, although their applicability to humans appears remote. These include: (i) inhibiting the replication of mutant mtDNA by selective hybridization with nucleic acid derivatives (such as peptide nucleic acids, PNAs) [147, 148]; (ii) importation of yeast tRNA to replace mutated human tRNA [149]; (iii) importation of wild-type polypeptides (either allotopically or xenotopically expressed) into mitochondria to replace mutated ones [150, 151, 152, 153] or to complement faulty function [154, 155]; (iv) importing specific restriction endonucleases or custom-designed zinc-finger nucleases that cut mutated but not wild-type mtDNA and act as “silver bullets” [156, 157, 158].

-

III.

Acting on pathogenesis. The most logical intervention in any inborn error of metabolism appears to be removing noxious compounds. In most mitochondrial encephalomyopathies, the obvious culprit is lactic acid [83]. Bicarbonate therapy is common and almost “automatic”, but should be used prudently [159]. Dichloroacetate (DCA) inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinase, keeps PDH in the dephosphorylated, active form, thus favoring pyruvate metabolism and lactate oxidation [160]. Although oral DCA was well tolerated in randomized studies of children with congenital lactic acidosis and heterogeneous mitochondrial diseases (including PDH deficiency and mtDNA- or nDNA-related defects of the RC), it did not improve neurological outcome and was associated with evidence of peripheral neuropathy [161, 162]. On the basis of tissue culture studies, the peripheral neuropathy was attributed to a reversible inhibition of myelin-related proteins by DCA [163]. Despite these non-alarming data in children, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over trial of oral DCA in a large and homogeneous cohort of patients carrying the A3243G MELAS mutation had to be terminated because of peripheral nerve toxicity [164], which at the very least exacerbates the lurking peripheral neuropathy due to the mtDNA mutation [165].

In MNGIE, the toxic metabolites that accumulate in blood as a direct consequence of the TP defect are thymidine and deoxyuridine [166]: hemodialysis was only transiently effective in lowering blood levels, whereas the effect of allo-SCT was more substantial and permanent, as discussed above [144].

Administration of electron acceptors is most effective in disorders due to primary defects of such acceptors, best exemplified by primary CoQ10 deficiencies. However, at least one child with LS and CoQ10 deficiency due to mutations in the PDSS2 gene did not respond to CoQ10 administration [34], possibly because therapy was started too late, because the dose was inadequate, or because the energy defect was too drastic [167]. In patients with secondary CoQ10 deficiency, the response to supplementation is generally good but unpredictable and often variable. For example, patients with the myopathic form of glutaric aciduria type II (GA II) due to electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH) deficiency may need both CoQ10 and riboflavin for optimal response [33].

“Cocktails” of vitamins and cofactors are the most widely used therapy in clinical practice. Their popularity is based on two principles: (i) their safety makes the doctor feel “Hippocratically correct” (“primum non nocere”) even when he/she doubts their efficacy; and (ii) their use is predicated by the two most widely accepted pathogenic mechanisms, energy shortage and oxidative stress.

In the hope of facilitating ATP production by a sluggish RC, electron flux is “boosted” by addition of electron acceptors (CoQ10, vitamin C, vitamin K, succinate). Alternatively, we try to boost the synthesis of a naturally occurring high-phosphate compound, phosphocreatine (PC) by administering creatine. L-carnitine is prescribed because plasma free carnitine tends to be lower and esterified carnitine higher than normal, probably reflecting a partial impairment of β-oxidation. Some encouragement for the use of vitamins and cofactors was provided by a study of ATP synthesis in lymphocytes from 12 patients with diverse RC disorders before and after 12 months of therapy with a “cocktail” that included CoQ10, L-carnitine, vitamin B complex, vitamin C, and vitamin K1 [168]. Although ATP synthesis increased significantly with treatment, none of the patients improved clinically, and in vitro exposure of control lymphocytes to the various components showed that only CoQ10 increased ATP synthesis in a dose-dependent manner.

Folic acid deserves special mention because early observations had shown that it was decreased in the CSF of patients with KSS [169, 170] and a recent study documented both clinical and neuroradiological improvement in a child after 1 year of monotherapy with 2.2 mg folinic acid/kg daily [171], suggesting that early and aggressive administration of this compound should be tried in this devastating condition.

To improve ATP synthesis, creatine monohydrate supplementation has been used, but the only two randomized studies came to different conclusions: a smaller cohort of severely affected patients improved [172], whereas a larger cohort of less severely affected patients did not [173], possibly due to the difference in muscle phosphocreatine concentration between the two groups [174, 175].

Scavenging excessive ROS is probably the most common approach not just to mitochondrial diseases due to RC defects but also to late-onset neurodegenerative disorders (including ALS, PD, and AD), in which there is direct or indirect evidence of oxidative stress [39]. Antioxidants used in clinical practice include vitamin E, CoQ10, idebenone, glutathione, and dihydrolipoate.

As mentioned above, CoQ10 is useful in primary CoQ10 deficiencies, but is also widely prescribed to patients with RC disorders. Although anecdotal reports (too numerous to be cited here) are generally positive, we still lack a rigorous double blind trial. However, clinical experience teaches that CoQ10 needs to be administered at high doses (no less than 300 mg daily in adults), which fortunately have shown to be well tolerated in numerous studies of large cohorts.

Importantly, initial studies of idebenone had suggested a beneficial effect only on the cardiopathic component of FA, but a recent standardized study showed a dose-related beneficial effect also on the neurological component of the disease [176].

The management of strokes in MELAS is difficult because we still have an incomplete understanding of pathogenesis. Increasing evidence, however, suggests an underlying mitochondrial angiopathy with altered vascular contractility. As citrulline [177] and arginine [178], both precursors of nitric oxide (NO), were decreased in MELAS patients, and NO homeostasis can affect vascular function, L-arginine administration has been studied rather extensively by Koga and collaborators: they found that intravenous administration of L-arginine (0.5 g/kg) during the acute phase improved all stroke-like symptoms, whereas interictal oral administration (0.15–0.30 g/kg) diminished both frequency and severity of strokes [178, 179, 180, 181]. Although these results remain to be confirmed by rigorously controlled studies, they do offer some hope for counteracting at least the most devastating manifestation of this disease.

The past 50 years have seen mitochondrial medicine develop beyond anyone’s wildest expectation and the plot is still thickening. However, our understanding of pathogenesis leaves much to be desired and progress in this area is indispensable for the development of rational therapeutic strategies. The fervor of research in laboratories around the world and the rise of national and international collaborative groups bodes well for the future.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by NIH grant HD32062 and by the Marriott Mitochondrial Disorder Clinical Research Fund (MMDCRF).

List of abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- Allo-SCT

allogeneic stem cell transplantation

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ANT1

adenine nucleotide transporter 1

- AOA1

Ataxia oculomotor apraxia type 1

- APTX

aprataxin

- AIF

apoptosis inducing factor

- AZT

azidothymidine

- BCS1L

cytochrome b-c complex assembly protein (complex III)

- Bi-PAP

bilevel positive air pressure

- CACT

carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase

- CMT

Charcot-Marie-Tooth

- CoQ

coenzyme Q (ubiquinone)

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- CPAP

continuous positive air pressure

- CPT

carnitine palmitoyltransferase

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DARS2

gene encoding mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase

- DCA

dichloroacetate

- DIC

dicarboxylate carrier

- DDP1

deafness dystonia protein 1

- DGUOK

deoxyguanosine kinase

- DOA

dominant optic atrophy

- EFG1

gene encoding elongation factor 1

- ETF

electron transfer flavoprotein

- EFTDH

electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase

- EFTu

elongation factor Tu

- ENT

ear-nose-throat

- FA

Friedreich ataxia

- FBSN

familial bilateral striatal necrosis

- GA

glutaric aciduria

- GDAP1

ganglioside-induced differentiation protein 1

- HSP

hereditary spastic paraplegia

- KSS

Kearns-Sayre syndrome

- LBSL

leukoencephalopathy. brain stem, spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation

- LHON

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy

- LPRRC

leucine-rich pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein

- LS

Leigh syndrome

- MELAS

mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes

- MERRF

myoclonus epilepsy and ragged-red fibers

- MFN

mitofusin

- MILS

maternally inherited Leigh syndrome

- MND

motor neuron disease

- MNGIE

mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy

- MPV17

MPV17 mitochondrial inner membrane protein (SYM1)

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- NARP

neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa

- ND

NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase

- nDNA

nuclear DNA

- NNH

Navajo neurohepatopathy

- NO

nitric oxide

- OPA1

dynamin-related GTPase mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PDHC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- PDSS2

decaprenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2

- PEO

progressive external ophthalmoplegia

- PNAS

peptide nucleic acids

- POLG

polymerase γ

- PUS1

pseudouridine synthase 1

- RC

respiratory chain

- RRF

ragged-red fibers

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCO

synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase

- SCS-A

succinyl-CoA synthetase

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- SUCLA2

gene encoding the β subunit of succinyl-CoA synthetase

- SUCLG1

gene encoding the α subunit of succinyl-CoA synthetase

- SURF1

surfeit gene 1

- TAZ

tafazzin

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid cycle (Krebs cycle)

- TIM

translocase of the inner membrane

- TK2

thymidine kinase 2

- TP

thymidine phosphorylase

- TYMP

the gene encoding thymidine phosphoylase

References

- 1.Luft R, Ikkos D, Palmieri G, et al. A case of severe hypermetabolism of nonthyroid origin with a defect in the maintenance of mitochondrial respiratory control: A correlated clinical, biochemical, and morphological study. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:1776–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Science 1988;242:1427–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt IJ, Harding AE, Morgan Hughes JA. Deletions of muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients with mitochondrial myopathies. Nature 1988;331:717–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luft R The development of mitochondrial medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994;91:8731–8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gvozdjáková A, ed. Mitochondrial Medicine: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMauro S, Hirano M, Schon EA, eds. Mitochondrial Medicine. Abingdon, UK: Informa Healthcare, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shy GM, Gonatas NK. Two childhood myopathies with abnormal mitochondria: I. Megaconial myopathy; II. Pleoconial myopathy. Brain 1966;89:133–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shy GM, Gonatas NK. Human myopathy with giant abnormal mitochondria. Science 1964;145:493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel WK, Cunningham CG. Rapid examination of muscle tissue: An improved trichrome stain method for fresh-frozen biopsy sections. Neurology 1963;13:919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapira Y, Harel S, Russell A. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies: a group of neuromuscular disorders with defects in oxidative metabolism. Isr. J. Med. Sci 1977;13:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitomap. MITOMAP: A human mitochondrial genome database. http://www.mitomap.org. 2003.

- 12.Sproule D, Kaufmann P. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and strokelike episodes (MELAS): A review of basic concepts, the clinical phenotype, and therapeutic management. Ann. NY Acad. Sci 2008;1142:133–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanske S, Coku J, Lu J, et al. The G13513A mutation in the ND5 gene of mitochondrial DNA as a common cause of MELAS or Leigh syndrome. Arch. Neurol 2008;65:368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manwaring N, Jones MM, Wang JJ, et al. Population prevalence of the MELAS A3243G mutation. Mitochondrion 2007;7:230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott HR, Samuels DC, Eden JA, et al. Pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations are common in the general population. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2008;83:254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santorelli FM, Shanske S, Macaya A, et al. The mutation at nt 8993 of mitochondrial DNA is a common cause of Leigh syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt IJ, Harding AE, Petty RK, Morgan Hughes JA. A new mitochondrial disease associated with mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:428–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carelli V, Barboni P, Sadun AA. Mitochondrial ophthalmology. In: DiMauro S, Hirano M, Schon EA, eds. Mitochondrial Medicine. London: Informa Healthcare, 2006:105–142. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreu AL, Hanna MG, Reichmann H, et al. Exercise intolerance due to mutations in the cytochrome b gene of mitochondrial DNA. New Engl. J. Med 1999;341:1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massa V, Fernandez-Vizarra E, Alshahwan S, et al. Severe infantile encephalomyopathy caused by a mutation in COX6B1, a nucleus-encoded subunit of cytochrome c oxidase. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2008;doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Giovanni S, Mirabella M, Spinazzola A, et al. Coenzyme Q10 reverses pathological phenotype and reduces apoptosis in familial CoQ10 deficiency. Neurology 2001;57:515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobreira C, Hirano M, Shanske S, et al. Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 1997;48:1238–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogasahara S, Engel AG, Frens D, Mack D. Muscle coenzyme Q deficiency in familial mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1989;86:2379–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gironi M, Lamperti C, Nemni R, et al. Late-onset cerebellar ataxia with hypogonadism and muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 2004;62:818–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamperti C, Naini A, Hirano M, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 2003;60:1206–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musumeci O, Naini A, Slonim AE, et al. Familial cerebellar ataxia with muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 2001;56:849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lalani S, Vladutiu GD, Plunkett K, et al. Isolated mitochondrial myopathy associated with muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Arch Neurol 2005;62:317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salviati L, Sacconi S, Murer L, et al. Infantile encephalomyopathy and nephropathy with CoQ10 deficiency: a CoQ10-responsive condition. Neurology 2005;65:606–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotig A, Appelkvist E-L, Geromel V, et al. Quinone-responsive multiple respiratory-chain dysfunction due to widespread coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Lancet 2000;356:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Maldergem L, Trijbels F, DiMauro S, et al. Coenzyme Q-responsive Leigh’s encephalopathy in two sisters. Ann Neurol 2002;52:750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diomedi-Camassei F, Di Giandomenico S, Santorelli F, et al. COQ2 nephropathy: A newly described inherited mitochondriopathy with primary renal involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2773–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinzii C, Kattah AG, Naini A, et al. Coenzyme Q deficiency and cerebellar ataxia associated with an aprataxin mutation. Neurology 2005;64:539–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gempel K, Topaloglu H, Talim B, et al. The myopathic form of coenzyme Q10 deficiency is caused by mutations in the electron-transferring-flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH) gene. Brain 2007;130:2037–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez LC, Quinzii C, Schuelke M, et al. Leigh syndrome with nephropathy and CoQ10 deficiency due to decaproneyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 (PDSS2) mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2006;79:1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mollet J, Giurgea I, Schlemmer D, et al. Prenyldiphosphate synthase (PDSS1) and OH-benzoate prenyltransferase (COQ2) mutations in ubiquinone deficiency and oxidative phosphorylation disorders. J. Clin. Invest 2007;117:765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinzii C, Naini A, Salviati L, et al. A mutation in para-Hydoxybenzoate-polyprenyl transferase (COQ2) causes primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2006;78:345–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagier-Tourenne C, Tazir M, Lopez LC, et al. ADSK3, an ancestral kinase, is mutated in a form of recessive ataxia associated with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2008;82:661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mollet J, Delahodde A, Serre V, et al. CABC1 gene mutations cause ubiquinone deficiency with cerebellar ataxia and seizures. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2008;82:623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial disorders in the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 2008;31:91–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishino I, Spinazzola A, Hirano M. Thymidine phosphorylase gene mutations in MNGIE, a human mitochondrial disorder. Science 1999;283:689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirano M, Silvestri G, Blake D, et al. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE): Clinical, biochemical and genetic features of an autosomal recessive mitochondrial disorder. Neurology 1994;44:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaukonen J, Juselius JK, Tiranti V, et al. Role of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 in mtDNA maintenance. Science 2000;289:782–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spelbrink JN, Li FY, Tiranti V, et al. Human mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with mutations in the gene encoding Twinkle, a phage T7 gene 4-like protein localized in mitochondria. Nature Genet. 2001;28:200–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Goethem G, Dermaut B, Lofgren A, et al. Mutation of POLG is associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia characterized by mtDNA deletions. Nature Genet. 2001;28:211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graziewicz MA, Longley MJ, Copeland WC. DNA polymerade gamma in mitochondrial DNA replication and repair. Chem. Rev 2006;106:385–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Longley MJ, Clark S, Man CYW, et al. Mutant POLG2 disrupts DNA polymerase gamma subunits and causes progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2006;78:1026–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zanna C, Ghelli A, Porcelli AM, et al. OPA1 mutations associated with dominant optic atrophy impair oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial fusion. Brain 2008;131:352–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferraris S, Clark S, Garelli E, et al. Perogressive external ophthalmoplegia and vision and hearing loss in a patient with mutations in POLG2 and OPA1. Arch. Neurol 2008;65:125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hudson G, Amati-Bonneau P, Blakeley E, et al. Mutation of OPA1 causes dominant optic atrophy with external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, deafness and multiple mitochondrial DNA deletions: a novel disorder of mtDNA maintenance. Brain 2007;131:329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amati-Bonneau P, Guichet A, Olichon A, et al. OPA1 R445H mutation in optic atrophy associated with sensorinaural deafness. Ann. Neurol 2005;58:958–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spinazzola A, Zeviani M. Disorders of nuclear-mitochondrial intergenomic signaling. Gene 2005;354:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oskoui M, Davidzon G, Pascual J, et al. Clinical spectrum of mitochondrial DNA depletion due to mutations in the thymidine kinase 2 gene. Arch. Neurol 2006;63:1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ostergaard E, Christensen E, Kristensen E, et al. Deficiency of the alpha subunit of succinate-coenzyme A ligase causes fatal infantile lactic acidosis with mitochondrial DNA depletion. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2007;81:383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elpeleg O, Miller C, Hershkovitz E, et al. Deficiency of the ADP-forming succinyl-CoA synthase activity is associated with encephalomyopathy and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2005;76:1081–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freisinger P, Futterer N, Lankes E, et al. Hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome caused by deoxyguanosine kinase (DGUOK) mutations. Arch. Neurol 2006;63:1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mandel H, Szargel R, Labay V, et al. The deoxyguanosine kinase gene is mutated in individuals with depleted hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA. Nature Genet. 2001;29:337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naviaux RK, Nguyen KV. POLG mutations associated with Alpers’ syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spinazzola A, Viscomi C, Fernandez-Vizarra E, et al. MPV17 encodes an inner mitochondrial membrane protein and is mutated in infantile hepatic mitochondrial DNA depletion. . Nature Genet. 2006;38:570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karadimas CL, Vu TH, Holve SA, et al. Navajo neurohepatopathy is caused by a mutation in the MPV17 gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2006;79:544–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacobs HT, Turnbull DM. Nuclear genes and mitochondrial translation: a new class of genetic disease. Trends Genet. 2005;21:312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antonicka H, Sasarman F, Kennaway NG, Shoubridge EA. The molecular basis for tissue specificity of the oxidative phosphorylation deficiencies in patients with mutations in the mitochondrial translation factor EFG1. Hum. Mol. Genet 2006;15:1835–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller C, Saada A, Shaul N, et al. Defective mitochondrial translation caused by a ribosomal protein (MRPS16) mutation. Ann. Neurol 2004;56:734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smeitink JAM, Elpeleg O, Antonicka H, et al. Distinct clinical phenotypes associated with a mutation in the mitochondrial translation elongation factor EFTs. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2006;79:869–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandez-Vizarra E, Berardinelli A, Valente L, et al. Nonsense mutation in pseudouridylate synthase 1 (PUS1) in two brothers affected by myopathy, lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA). J. Med. Genet 2007;44:173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bykhovskaya Y, Casas KA, Mengesha E, et al. Missense mutation in pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) causes mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA). Am. J. Hum. Genet 2004;74:1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ. et al. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nature Genet. 2007;39:534–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics in disease. New Engl. J. Med 2007;356:1707–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fichera M, Lo Giudice M, Falco M, et al. Evidence of kinesin heavy chain (KIF5A) involvement in pure hereditary spastic paraplegia. Neurology 2004;63:1108–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin J-M, et al. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nature Genet. 2000;26:207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UEA, et al. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nature Genet. 2000;26:211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawson VH, Graham BV, Flanigan KM. Clinical and electrophysiologic features of CMT2A with mutations in the mitofusin 2 gene. Neurology 2005;65:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zuchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nature Genet. 2004;36:449–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pedrola L, Espert A, Wu X, et al. GDAP1, the protein causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4A, is expressed in neurons and is associated with mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet 2005;14:1087–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Niemann A, Ruegg M, La Padula V, et al. Ganglioside-induced differentiation associated protein 1 is a regulator of the mitochondrial network: new implications for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J. Cell Biol 2005;170:1067–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barth PG, Wanders RJA, Vreken P, et al. X-linked cardioskeletal myopathy and neutropenia (Barth syndrome) (MIM 30260). J. Inher. Metab. Dis 1999;22:555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bione S, D’Adamo P, Maestrini E, et al. A novel X-linked gene, G4.5, is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nature Genet. 1996;12:385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schlame M, Ren M. Barth syndrome, a human disorder of cardiolipin metabolism. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5450–5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]