Abstract

Language access barriers for individuals with limited English proficiency are a challenge to advance care planning (ACP). Whether Spanish-language translations of ACP resources are broadly acceptable by US Spanish-language speakers from diverse countries is unclear. This ethnographic qualitative study ascertained challenges and facilitators to ACP with respect to Spanish-language translation of ACP resources. We conducted focus groups with a heterogeneous sample of 29 Spanish-speaking persons who had experience with ACP as a patient, family member and/or medical interpreter. We conducted thematic analysis with axial coding. Themes include: 1. ACP translations are confusing; 2. ACP understanding is affected by country of origin; 3. ACP understanding is affected by local healthcare provider culture and practice; and 4. ACP needs to be normalized into local communities. ACP is both a cultural and clinical practice. Recommendations for increasing ACP uptake extend beyond language translation to acknowledging users’ culture of origin and local healthcare culture.

Keywords: Hispanic Americans, Latinos, language barriers, focus group, advance directives, advance care planning, language translation

INTRODUCTION

Advanced care planning (ACP) supports the delivery of future medical care based on patients’ personal values and life goals (Sudore et al., 2017). While ACP is important to person-centered healthcare, certain segments of the US population are less likely to complete ACPs, including Latinx/Hispanic individuals (Harrison et al., 2016; Portanova et al., 2017; Schickedanz et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2008).

One challenge to ACP is language access (Schickedanz et al., 2009). An estimated 67.7 million persons speak a language other than English at home. Of these, 41.2 million speak Spanish (2021 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Spanish-language speakers in the US include members of Latinx and Hispanic communities from Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish cultures or origin (Office of Management and Budget, 1997).

To improve access to ACP for the estimated 16.3 million US Spanish-language speakers with limited-English proficiency (2021 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, 2021), several ACP resources were translated into Spanish, including PREPARE (Sudore, 2020), Five Wishes (Five Wishes, 2020), the Conversation Project (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2021) and Honoring Choices MA (Honoring Choices Massachusetts Network, 2022). While translation can improve ACP for diverse populations, the Latinx and Hispanic community is not homogeneous, and translations from one community may not be relevant for others based on linguistic differences across countries (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2015; Maldonado et al., 2019). According to the National Institute of Health’s Cultural Framework for Healthcare, treating all members of a particular foreign language group as homogenous can contribute to failure of interventions to achieve desired outcomes, including closing the health equity gap (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2015).

Despite the diversity of US Spanish-language speakers, prior ACP studies in Latinx/Hispanic populations have mainly focused on communities in California, Texas, and the Southwest (i.e. Southern New Mexico) where the Spanish-speaking populations largely draw from Mexico (Pew Research Center, 2014; Smith et al, 2008; Sudore et al, 2018). Whether resources developed in those communities are equally applicable to Latinx/Hispanic persons across the US or from different parts of the Spanish-speaking world is unclear. Therefore, we conducted this study to inform ACP efforts by soliciting the perspectives of Latinx/Hispanic individuals from diverse counties of origin in Central Massachusetts. Massachusetts ranks first in the US for Latinx/Hispanics of non-Mexican origin, with 94% being of outside of Mexico (Pew Research Center, 2014). In this context, we conducted focus groups to discuss challenges and facilitators to ACP for US Spanish-language speakers, including the acceptability of existing ACP tools translated into Spanish.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted an ethnographic qualitative study using focus groups. Ethnography is a qualitative method for collecting data to draw conclusions about culture and how communities and individuals function (Jones & Smith, 2017). Focus groups are a preferred way to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest from a group, particularly when there is anticipated value in the interactions arising from the group discussions (Acocella, 2012; Krueger & Casey, 2009).

Study Participants, Recruitment & Eligibility

For recruitment, we partnered with a local community-based, health equity organization in Central Massachusetts with strong ties to public health and community service organizations. We purposively recruited individuals who were native Spanish speaking and had either personal and/or professional experience with ACP, including medical interpreters because they have front-line experience with healthcare-related conversations. Our community partner, the Center for Health Impact, used a snowball sampling approach to recruit participants by telephone from Worcester County, the largest county in central Massachusetts where approximately 12% of the population identifies as Latinx/Hispanic (QuickFacts: Worcester County Massachusetts, U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). The target sample size was 8–10 individuals per focus group, because larger groups can limit the detail of some respondents who may feel pressure to share airtime with others (Krueger & Casey, 2009). Inclusion criteria included being 18 years or older, self-identifying as a native Spanish speaker, ability to provide informed consent, and direct experience with ACP as a patient, family member, and/or medical interpreter. Exclusion criteria included being non-Spanish speaking. This study was approved by the UMass Chan Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Based on literature review and working with experts in medical interpretation, language translation and ACP, we created a semi-structured interview guide with supplemental probes (eFigures 1 and 2). The interview guide included open-ended questions about general experiences with, understanding of and familiarity with ACP, reactions to ACP-related documents, and ideas for improving ACP in Spanish-speaking communities. The interview guide was designed to be inclusive of participants' diverse backgrounds and perspectives as patients, family members, and medical interpreters. The guide was reviewed for understanding by two medical interpreter trainers and refined for clarity prior to the focus groups.

Study Procedures

Focus groups were conducted over a four-week period in January 2019 at the office of our community partner organization. Each focus group was audio-recorded and conducted by Master’s-level trained study staff facilitators who are native Spanish speakers and credentialed interpreters (GC;LR). A research assistant fluent in Spanish (GP) took field notes and helped promote discussion as needed. Written informed consent was obtained and participants received a $20 gift card upon completion.

A facilitator who had no prior relationship with the focus group participants led the discussion using the interview guide. During the focus group, all participants were given the Cinco Deseos (Spanish translation of the Five Wishes) booklet, a legal advance directive in Spanish, and a Spanish Health Care Proxy Form from the Honoring Choices Massachusetts website. One group was additionally presented with the online version of The Conversation Project in Spanish, a resource for end-of-life conversations. Participants were presented the ACP material only in Spanish so as not to bias their interpretation and responses about the quality of translation and comprehensibility, a main aim of the study. Each session lasted approximately 90 minutes and all participants stayed for the entire session. After review and analysis of transcripts, no new information or themes were observed in the data. Identified themes were minimally expanded after analyzing data from the second focus group, which allowed the team to confirm meaning saturation. At that time, the decision was made to cease data collection (Hennink et al., 2019).

Data Analysis

Focus groups were professionally transcribed verbatim in Spanish. Final transcripts were de-identified and reviewed in the original Spanish for accuracy by two team members (GP;GC). NVivo 12.0 Pro (QSR International, Australia) was used to manage coding. We used content and thematic analysis to analyze transcripts (Miles et al., 2013). GP and GC created a preliminary codebook based on the interview guide and on emergent themes based on line by line coding of initial transcripts. We implemented recurring team debriefing meetings and member checks to ensure trustworthiness, the qualitative equivalent of reliability and validity (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Team members met weekly during data collection to review transcripts and discuss coding. Member checks provided the opportunity for team members to validate themes emerging from the data. Codes were organized into categories through a consensus process to reflect a range of subthemes, and to characterize both confirmatory and contradictory narratives (Allen, 2017). The final coding schema and subsequent themes were reviewed and discussed by the entire research team to reach consensus. External validation of the final results were provided by a focus group participant. This study follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (Tong et al., 2007).

RESULTS

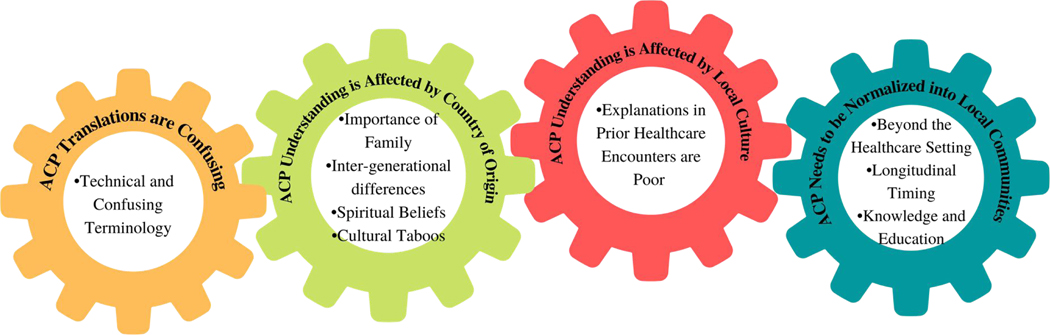

The final sample included 29 participants. Each focus group included 7 to 13 participants, a mix of women and men, professional medical interpreters and non-interpreters, and persons from different countries within the Caribbean, Central and South America (Table 1). Four themes emerged: 1. ACP translations are confusing; 2. ACP understanding is affected by country of origin; 3. ACP understanding is affected by local healthcare provider culture and practice; and 4. ACP needs to be normalized into local communities (Figure 1). Full text of exemplar quotes in Spanish and English are provided in eFigure 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 29 Participants

| Total (n=29) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–40 | 12 | 41.4% |

| 41–65 | 13 | 44.8% |

| >65 | 2 | 6.9% |

| Missing | 2 | 6.9% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8 | 27.6% |

| Female | 21 | 72.4% |

| Country of Origin | ||

| United States | 2 | 6.9% |

| Central America | ||

| Mexico | 2 | 6.9% |

| South America | ||

| Venezuela | 3 | 10.3% |

| Bolivia | 2 | 6.9% |

| Caribbean | ||

| Dominican Republic | 12 | 41.4% |

| Puerto Rico | 8 | 27.5% |

| Role * | ||

| Medical interpreter | 10 | 34.5% |

| Other Medical Professional | 5 | 17.2% |

| Patient | 15 | 51.7% |

| Family Member | 18 | 62.1% |

Total exceeds 100% because of overlap.

Figure 1.

Themes and Subthemes Reflecting Barriers to Advance Care Planning for Diverse US Spanish-language Speakers: Patient, Family and Medical Interpreter Perspectives

ACP Translations are Confusing

In reaction to existing documents (e.g. Cinco Deseos booklet and a Spanish Health Care Proxy Form from the Honoring Choices Massachusetts website), participants reported that ACP terminology is technical and confusing. ACP terms are difficult to understand and unfamiliar, regardless of language. A social worker from one of the groups shared:

… Use language that the person who is filling out the documents can understand…many people are confused, they do not know how to fill it out, do not know what it means and prefer not to ask. Then by not asking, they decide not to do it at all. But if the terms were less technical, if they were more basic language, everyone would have felt a little bit more…ability to do those things… (ID:1–7)

Translations themselves were also challenging. Participants noted that the way ACP is translated in Spanish “does not make sense” and “makes little to no relation to what it is about.” For example, the term “La Planificación de Voluntad Anticipada,” translated as “The Planification of Anticipated Wishes,” was problematic. Participants explained that persons with some knowledge of English may do a decontextualized translation of Advanced Care Planning to Spanish, whereas someone who does not know English or recent immigrants may not know the meaning of ACP, particularly if ACP was not a concept in their country of origin. A case manager explained:

…for a person who has been living in this country, it might make sense because it is an exact translation of the English version, but for a person who has just come from Bolivia they would not understand... (ID:3–3)

Participants suggested alternative titles, such as “tipo de asistencia médica que deseo en caso que esté en riesgo de morir,” (type of medical assistance that I wish for in case I am at risk of dying). They suggested that there should be some “elegant words” rather than just using lay language, to explicitly explain that the document is about medical treatments related to the possibility of dying. As one participant suggested “planificar en salud” (planning in health). The group shared that in Puerto Rico it is called “declaración previa de voluntades” (prior declaration of wills). Another participant said that in some places they call it “directrices avanzadas” (advanced directives). Other suggestions included “Decreto de voluntad antes de morir” (voluntary decree before death) and “Deseos de al final de la vida” (end of life desires).

ACP Understanding is Affected by Country of Origin

Participants agreed that an individual’s background and country of origin influence their knowledge of, exposure to, and interpretation of ACP. Further, separate from the cultural aspects of their country of origin, the practice of ACP in their country could affect their prior exposure to ACP. A family member/doctor from the Dominican Republic explained:

So my country, for example, incredibly that is [ACP document] not used…. So, incredibly, amazingly, being in the field of medicine, I learned about those documents here because there it was known that there are some but that are not talked about. (ID:3–2)

Participants also highlighted various cultural factors to consider including the role of family, intergenerational differences, and spirituality. Cultural taboos and the individual’s country of origin can make speaking about death difficult.

Importance of Family.

Participants discussed the importance of having ACP discussions with their family members. Family is important because they make decisions and sometimes they do not align with the patient’s desires. One family member participant captured this idea:

…you have to take into account how important family is to us because you can choose someone who respects your wishes, but that creates chaos if the rest disagree. What can happen to any culture, but we are a culture that family is super important. So, I think that has to be considered when planning materials. (ID:3–1)

For example, a participant with experience as a patient shared that in her country, medical decisions are made by the immediate family not an assigned proxy. Further, the focus is not on what the individual person desires:

…in other countries, medical decisions belong to the family nucleus. I mean, in Bolivia, …if I was sick and had a husband, they would ask him how he wants us to treat his wife…So that's an awareness and an education that needs to be given to people…how these things are done because where we come from they are not regular practices. (ID:3–3)

Participants had some understanding that ACP involved capturing patient wishes. This was discussed as an essential part of ACP because some family members’ wishes may differ from the individual’s desires for themselves. The following quote contextualizes this idea:

It would be the oldest, but talking to her and I tell her, “Look, you know I don't want to be intubated, I don't want anything artificial or anything invasive.” She says…“No, I'm not going to allow that. You have to do this and this and this and this.” I kept quiet but I've been thinking and then I have to change the [healthcare proxy]. (ID:1–2)

Inter-generational Issues.

Generational differences play an important role in ACP. Participants felt if ACP is discussed with people when they are young, they may be more receptive to having those conversations, while older adults may find it more difficult. Some participants also talked about the older adults in their family being more religious, leaving things up to God, and fearing conversations that have to do with death. A family member participant explained:

…not much now with my generation, but my parents and grandparents leave everything to God. So whatever God wants, that's what's going to happen. “I don't care where you put me because I'm not going to be alive...” (ID:1–7)

Spiritual Beliefs.

Participants shared examples of their loved ones relying on God when they are unable to decide for themselves. They shared that at times some of their family members felt that what happens will happen and that it was meant to be based on their spiritual beliefs. In addition, some felt that they did not want to talk about ACP with their loved ones because of the faith they had in God to improve their health. For example,

… I grew up in the church and the people in the hospital say, “Call the pastor… He's going to pray for me and I'm going to heal.” And they don't want to have that conversation anymore. (ID:1–7)

Cultural Taboos.

Participants also mentioned certain medical beliefs in different cultures and religions that are important for healthcare providers to know. In some Latinx/Hispanic cultures, it is taboo to talk about death and plan for circumstances such as an emergency. The fear is that talking about death can “bring death closer”. Participants highlighted the importance of ACP not being about death, but rather focusing on when the person is no longer able to make decisions for themselves; this was felt to help alleviate the stigma and negative feelings on the subject. But participants noted that, within the Latinx/Hispanic culture, the topic has not been normalized and is not a typical topic of conversation among families. One participant with experience as a patient and family member explained:

I mean, it's a cultural change because at least I grew up that we don't talk about death because you're anticipating it, but a lot has changed. (ID:3–1)

ACP Understanding is Affected by Culture and Practices at Local Healthcare Providers

Participants articulated several key ways in which their understanding and perception of ACP were formed by the context of their experiences in the local healthcare systems, separate and apart from the cultural aspects related to their country of origin.

Explanations in Prior Healthcare Encounters are Poor.

Some participants noted that the term ‘advance care planning’ begins to make sense when presented in context, but that it was not appropriately contextualized in their experience. Participants felt that ACP documents and the purpose of ACP had not been clearly explained to them in their healthcare encounters. An interpreter participant shared an experience she had as a patient:

In the emergency department they asked me,…,“Do you have a proxy?” But they never explained it….I for one am in the position of being an interpreter and we know…but no one has explained it to me. (ID:2–6)

There was little appreciation that sharing values and wishes for medical decision-making was important in the selection of and discussions with the healthcare proxy. A participant commented:

…what I don't like about this document is that if you start reading it, it is…not clear that these are your wishes. The person I want to appoint to make decisions. Change the “make.” So they can ”follow” my decisions on my behalf when I can't make them anymore… it is still very, very confusing what is a proxy.…They are going to make the decisions you wanted when you were able to…the explanations, the documents are not good... (ID:2–5)

Apart from the documents themselves, participants expressed a range of understanding of content and when ACP discussions were relevant. Some participants related ACP documents with end-of-life only decisions; the idea of upstreaming ACP before end-of-life decisions was seen as novel. Participants felt that these conversations should be generalized and addressed outside of the context of medical visits and hospitalizations.

ACP Needs to be Normalized into Local Communities

A theme that emerged is that ACP needs to be normalized in communities so that families and patients of all ages can be better prepared for these conversations. Despite several of the participants describing the difficulty of talking about death from a cultural point of view, by the end of the focus group discussions, the perceptions of many of the participants had evolved. Participants discussed new realizations about the value of ACP and emphasized the importance of the influence of cultural context as a bridge to normalizing ACP into the current culture of healthcare.

But the cultural factor must be taken into account. I really think that because I'm very close to a doctor, that is, my Venezuelan Latino doctor friends. They explain it to their patient in a certain way and the patient is less scared and understands it more in the same language because when you ask a Latino person about the proxy or their desires, “Doctor, am I dying?” like she says, even if they are healthy and even if they ask during their consultation. So I believe it must also be approached from a cultural point of view. (ID:2–5)

While participants suggested that the presentation of ACP documents should consider length, appearance, and literacy about healthcare, normalization is meant to take into consideration the local and prior experiences with ACP. Specific recommendations for normalizing ACP are summarized in Table 2, and major recommendations are highlighted below in terms of expanding the setting for ACP, and increasing timeliness, knowledge and education.

Table 2.

Recommendations for How to Normalize Advance Care Planning among Spanish-language Speakers in the U.S., by Site

| Outside of the Healthcare Delivery Systemo |

| Who |

| • Community-based organizations for healthy aging |

| • Target friends and family |

| Where: Community Workshops & Spiritual Communities |

| • Potential Locations |

| ∘ Spanish-speaking churches |

| ∘ Religious gathering places |

| ∘ Spanish Community Centers |

| ∘ Kiosk at a town/city fair with ACP material |

| Communication Media: Radio & Social Media |

| • Television and radio commercials |

| • Personal social media accounts (e.g. planning ahead for who manages your Facebook account after you die) |

| • Social media advertisements |

| Inside the Healthcare Delivery System |

| Who |

| • Primary care provider who spends the most time with the patient |

| • A Spanish-speaking person at the medical center who can have specific days that they approach patients about ACP and give them resources |

| • A social worker |

| Where and How |

| • Clinic workshops for providers and patients |

| • Commercial/presentation about ACP in waiting rooms at the clinic |

| • ACP workshops in nursing homes |

Beyond the Healthcare Setting.

The community was felt to be the appropriate setting to have conversations with family members and to incorporate important aspects of culture and religion. One participant commented:

…Here there are many communities that have like a local center or a communal center. They should do a – come with your family members, we are going to talk about an important topic even if it is one time per year. (ID:2–9)

Community settings can allow more time to consider how to prepare, can include the family in decision-making, and can incorporate community leaders such as clergy. One participant shared the idea of having the topic of ACP featured in discussions at her church:

I belong to a religious institution and I am part of the medical team of that church. …sometimes they put me to give talks...I believe it can be a way to drive it…. (ID:3–2)

Longitudinal Timing.

To normalize ACP, participants recommended longitudinal conversations between clinicians and patients and amongst families. Participants felt it is important for healthcare providers to continue to have ACP conversations with their patients given the importance of the topic and changing circumstances, and should be tailored to patients’ age and health. A medical interpreter explained:

…I think that focusing on the fact that this is an anticipated thing is most important. This should be with primary care doctors at your annual check-up that you have 30 years to do it 30 times... (ID:2–5)

From the perspective of a patient, participants stressed the importance of being prepared for health events. A participant comments on a personal experience with their family:

…But now being a widow it is very important for me to prepare my future and which of my children to choose in that regard. So that's why I tell you it's not age, it's not when you're sick, it’s about being more prepared and also preparing your family more, that you're not giving them the burden of them deciding for you, it’s what you want and so it's a peace of mind, a peace of heart that even if they don't agree, that's what my mom wanted. (ID:2–5)

Knowledge and Education.

Participants felt increasing improving education about ACP is key. For patients and families, this included clarifying the meaning and goals of ACP. For example, more information and clarity for HCPs about their role was recommended, so that HCPs could understand their responsibilities and learn about the patient’s preferences. Two participants discussed this idea with each other:

ID:2–9 …include in the same brochure something that is to give it to the person you authorize. For example, look these are my Five Wishes but this part is for you as my proxy to read and explain to the person you don't make the decision. To clearly explain to the person you are going to give them… Look, this is for the proxy. These are the things you have to do, these are your rights but also explain [ph] what the desire is.

ID:2–5 Responsibility.

ID:2–9 Yeah, explaining it because here it says my things, mine and one fills it out and for the person. So, OK, what do I have to do? Here, doctor. I have it here, what do I have to do? Then it would be nice if you say as a proxy that you are doing this, even if it's a small note or something or a separate pamphlet that now you're the proxy. So, this is it— And that would be nice for the person who doesn't understand it.

Participants agreed that the importance of ACP should be conveyed to patients and families to prepare for health events. One recommendation was to have available information about local ACP resources in the community that answers ACP-related questions and provide additional information.

Once normalization of ACP is addressed within local Latinx/Hispanic communities, translated ACP material needs to be culturally responsive. Specific recommendations for culturally responsive material are summarized in Table 2. Taken together, the themes illustrate how ACP tools exist in relation to the larger goal of conducting ACP in Spanish-speaking populations, and how conducting ACP, in general, is informed by prior experiences with ACP and broader sociocultural factors.

DISCUSSION

This study examined whether existing Spanish-language translations for ACP were acceptable across heterogenous persons from different Spanish-speaking countries. Results show that Spanish-language translations of ACP materials were challenging both linguistically and conceptually. Participants emphasized the importance of a person’s country of origin in terms of culture, specifically with respect to socio-cultural-spiritual factors that affect reactions to ACP. Results confirm that core elements of language and culture vary regionally and interact with local experiences of ACP across different healthcare systems. Taken together, our findings suggest that efforts to increase ACP would benefit from normalizing ACP into local communities in ways that take both country of origin and local healthcare delivery practices of ACP into account. Our findings are important in light of recent U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommendations to improve access to services for people with limited proficiency in English (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022).

Our findings are consistent with the NIH Cultural Framework of Health report’s contention that the “explanatory power of culture“ is underappreciated and that healthcare interventions to address disparity gaps need to acknowledge the influence of contextual factors, such as culture, that can affect intervention effectiveness (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2015). Our study is also consistent with the NIH’s contention that “…to propose a target population as simply French, Portuguese, or Spanish-speaking can treat the group as homogeneous in a target population’s beliefs and behaviors when a language group may consist of multiple subgroups...” (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2015).

Our study supports the need to consider the cultural context of patients and families when discussing ACP. This is consistent with an experimental ACP program in Los Angeles, (Nedjat-Haiem et al., 2017) and programs that weave cultural preferences into completing advanced directives (Portanova et al., 2017), support family group decision-making at home (Cervantes et al., 2017). Such programs can complement recommendations to provide ACP in a patient’s primary language (Maldonado et al., 2019) and to provide easy-to-read material is “even if patients have previous experience with the ACP process.”(Nouri et al., 2019).

A conceptual challenge is that ACP is not necessarily a formal practice in healthcare practice areas across Latin America (Soto-Perez-de-Celis et al., 2017). The closest official exercise to ACP would be wills and testaments, and even these activities may be reserved for reduced, wealthier groups (Kelly et al., 2013). Bridging these concepts with ACP through a person- and family-centered approaches that are connected to culturally sensitive religious and spiritual practices at the end of life (Smith et al., 2008; Thienprayoon et al., 2016) may help to avoid the pitfalls of ineffective end-of-life care communication that can have detrimental consequences (Shen et al., 2016).

Medical interpreters may be a valuable resource for health care organizations trying to build strategies for addressing ACP. Medical interpreters may be able to lend insight into nuances of culture and religion and country of origin. Interventions could feature medical interpreters as facilitators of ACP conversations and document completion, provided they are given additional training to enhance their understanding and knowledge of ACP. For those who do not usually need a medical interpreter, community health workers versed in local cultural nuances and ACP could assist with bridging the cultural gap (Calista & Tjia, 2017).

More broadly, a community-based approach that extends ACP outside of the healthcare system walls was recommended by our participants, particularly one that targets families. Cruz-Oliver et al. suggest that solutions for Spanish families can include the use of community religious leaders and media (Cruz-Oliver & Sanchez-Reilly, 2016; Cruz-Oliver et al., 2021). This is also supported by Sudore et al. (2018) who suggest that conversations among family/friends “maybe one of the most important targets for ACP interventions”. When those conversations are normalized, it allows ACP to be a common topic in households.

Another ACP strategy is working with faith-based communities, an approach well studied in Black communities (Anderson, 2021; Catlett & Campbell, 2021; McDonnell & Idler, 2020). As spiritual beliefs and religion are important for many Latinx/Hispanic persons, another strategy is to provide ACP education within churches (Bullock, 2006). Community-based gatherings such as World Cafés are also a site for ongoing education (Biondo et al., 2019). Such efforts may address the disparities in hospice care in Spanish-speaking communities (Kelley, 2010).

A study limitation is that it was conducted in a single Central Massachusetts community. Mitigating this is the diversity of the participants’ countries of origin, because most prior studies have been conducted in Western and Southwestern US., where the Latinx/Hispanic population is predominantly from Mexico. Our study adds richness to the perspectives of studies examining ACP in Latinx/Hispanic patients in the US. Strengths of our study include diverse participant representation from the Caribbean, Central and South American counties, as well as the unique multi-perspective engagement of professional medical interpreters, patients, and family members.

In summary, language access barriers to ACP are nested within greater challenges of cultural interpretation based on both individuals’ countries of origin and local healthcare experiences. High-quality translation of ACP resources alone are insufficient to bridge cultural gaps. Efforts to improve ACP uptake need to address both language translation and cultural nuances to increase patient and family understanding.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Addresses the importance of considering the heterogeneity of the Latinx/Hispanic population when using ACP resources with patients and families.

Characterizes ACP perspectives of patients, family members, and medical interpreters from different Latin American countries.

Describes how current translations of ACP documents are interpreted by diverse Spanish-speaking persons and provides their suggestions for improvements.

Applications of study findings

Cultural adaptation can enhance language translation of ACP resources.

Medical interpreters can add cultural insights and support ACP conversations.

Community interventions can help normalize ACP.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to extend deep thanks to the focus group participants and the Center for Health Impact, without whom this work would not be possible, and would also like to acknowledge Lynley Rappaport MEd, MPH, MA for conducting one of the focus groups.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from the Cambia Health Foundation [Sojourns Scholar Leadership to JT], and the National Institutes of Health [K24 AG068300 to JT]

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS:

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD:

University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School

IRB PROTOCOL APPROVAL NUMBER: H00015417

Contributor Information

Geraldine Puerto, UMass Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Germán Chiriboga, UMass Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Susan DeSanto-Madeya, University of Rhode Island, College of Nursing, Providence, RI.

Vennesa Duodu, UMass Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Dulce M. Cruz-Oliver, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Jennifer Tjia, UMass Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA.

LITERATURE CITED

- Acocella I. (2012). The focus groups in social research: advantages and disadvantages. Quality and Quantity, 46(4), 12. 10.1007/s11135-011-9600-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aging with Dignity. (2020). Five Wishes. Retrieved August 17, 2021 from https://fivewishes.org [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. Axial Coding. In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GT (2021, Oct-Dec). Let’s Talk About ACP Pilot Study: A Culturally-Responsive Approach to Advance Care Planning Education in African-American Communities. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care, 17(4), 267–277. 10.1080/15524256.2021.1976354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondo PD, King S, Minhas B, Fassbender K, & Simon JE (2019, Jun 3). How to increase public participation in advance care planning: findings from a World Café to elicit community group perspectives. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 679. 10.1186/s12889-019-7034-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock K. (2006, Feb). Promoting advance directives among African Americans: a faith-based model. J Palliat Med, 9(1), 183–195. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calista J, & Tjia J. (2017, Apr). Moving the Advance Care Planning Needle With Community Health Workers. Med Care, 55(4), 315–318. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlett L, & Campbell C. (2021, Jun). Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care Literacy Initiatives in African American Faith Communities: A Systematic Integrative Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 38(6), 719–730. 10.1177/1049909120979164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, & Fischer S. (2017, May 8). Qualitative Interviews Exploring Palliative Care Perspectives of Latinos on Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 12(5), 788–798. 10.2215/cjn.10260916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Oliver D, & Sanchez-Reilly S. (2016). Barriers to Quality End-of-Life Care for Latinos: Hospice Health Care Professionals’ Perspective. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 18(6), 505–511. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Oliver DM, Abshire M, Budhathoki C, Oliver DP, Volandes A, & Smith TJ (2021, Feb). Reflections of Hospice Staff Members About Educating Hospice Family Caregivers Through Telenovela. Am J Hosp Palliat Care, 38(2), 161–168. 10.1177/1049909120936169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, & Smith AK (2016, Dec 1). Low Completion and Disparities in Advance Care Planning Activities Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med, 176(12), 1872–1875. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, & Weber MB (2019, Aug). What Influences Saturation? Estimating Sample Sizes in Focus Group Research. Qual Health Res, 29(10), 1483–1496. 10.1177/1049732318821692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoring Choices Massachusetts Network. (2021). Honoring Choices Massachusetts. Retrieved August 17, 2021 from https://www.honoringchoicesmass.com [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2021). The Conversation Project. Retrieved August 17, 2021 from https://theconversationproject.org [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, & Smith J. (2017). Ethnography: challenges and opportunities. Evidence-Based Nursing 20(4), 98–100. 10.1136/eb-2017-102786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler WW, George SM, & Elwood WN (2015). The cultural framework for health: An integrative approach for research and program design and evaluation. N. I. o. H. O. o. B. a. S. S. Research. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/Culturalframeworkforhealth.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AS, Wenger NS, & Sarkisian CA (2010, Jun). Opiniones: end-of-life care preferences and planning of older Latinos. J Am Geriatr Soc, 58(6), 1109–1116. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02853.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CM, Masters JL, & DeViney S. (2013, Jul). End-of-life planning activities: an integrated process. Death Stud, 37(6), 529–551. 10.1080/07481187.2011.653081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, & Casey MA (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado LY, Goodson RB, Mulroy MC, Johnson EM, Reilly JM, & Homeier DC (2019, May-Jun). Wellness in Sickness and Health (The W.I.S.H. Project): Advance Care Planning Preferences and Experiences Among Elderly Latino Patients. Clin Gerontol, 42(3), 259–266. 10.1080/07317115.2017.1389793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell J, & Idler E. (2020). Promoting advance care planning in African American faith communities: literature review and assessment of church-based programs. Palliat Care Soc Pract, 14, 2632352420975780. 10.1177/2632352420975780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldaña J. (2013). Qualitative Data Analysis: A methods sourcebook (3 ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Gonzalez K, Quintana A, Ell K, O’Connell M, Thompson B, & Mishra SI (2017, Sep). Implementing an Advance Care Planning Intervention in Community Settings with Older Latinos: A Feasibility Study. J Palliat Med, 20(9), 984–993. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri SS, Barnes DE, Volow AM, McMahan RD, Kushel M, Jin C, Boscardin J, & Sudore RL (2019, Oct). Health Literacy Matters More Than Experience for Advance Care Planning Knowledge Among Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 67(10), 2151–2156. 10.1111/jgs.16129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (1997). Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. United States Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1997-10-30/pdf/97-28653.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2014). Demographic and Economic Profiles of Hispanics by State and County, 2014: Massachusetts. Retrieved August 17, 2021 from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/ma [Google Scholar]

- Portanova J, Ailshire J, Perez C, Rahman A, & Enguidanos S. (2017, Jun). Ethnic Differences in Advance Directive Completion and Care Preferences: What Has Changed in a Decade? J Am Geriatr Soc, 65(6), 1352–1357. 10.1111/jgs.14800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, Knight SJ, Williams BA, & Sudore RL (2009, Jan). A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc, 57(1), 31–39. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MJ, Prigerson HG, Paulk E, Trevino KM, Penedo FJ, Tergas AI, Epstein AS, Neugut AI, & Maciejewski PK (2016, Jun 1). Impact of end-of-life discussions on the reduction of Latino/non-Latino disparities in do-not-resuscitate order completion. Cancer, 122(11), 1749–1756. 10.1002/cncr.29973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, Balboni TA, Maciejewski PK, Block SD, & Prigerson HG (2008, Sep 1). Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol, 26(25), 4131–4137. 10.1200/jco.2007.14.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Pastrana T, Ruiz-Mendoza R, Bukowski A, & Goss PE (2017, Jun). End-of-Life Care in Latin America. J Glob Oncol, 3(3), 261–270. 10.1200/jgo.2016.005579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore R. (2020). PREPARE for your care. Retrieved August 17, 2021 from https://prepareforyourcare.org/welcome [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, Matlock DD, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ, Ritchie CS, Kutner JS, Teno JM, Thomas J, McMahan RD, & Heyland DK (2017, May). Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage, 53(5), 821–832.e821. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, Shi Y, Boscardin WJ, Osua S, & Barnes DE (2018, Dec 1). Engaging Diverse English- and Spanish-Speaking Older Adults in Advance Care Planning: The PREPARE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med, 178(12), 1616–1625. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thienprayoon R, Marks E, Funes M, Martinez-Puente LM, Winick N, & Lee SC (2016, Jan). Perceptions of the Pediatric Hospice Experience among English- and Spanish-Speaking Families. J Palliat Med, 19(1), 30–41. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J. (2007, Dec). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2021). DP02 Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. (2021). Retrieved November 3, 2022 from https://data.census.gov/table?tid=ACSDP1Y2021.DP02 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2021). QuickFacts: Worcester County, Massachusetts. Retrieved August 15, 2021 from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/worcestercountymassachusetts [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2022). HHS Takes Action to Break Language Barriers. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/10/06/hhs-takes-action-break-language-barriers.html [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.